the doctor

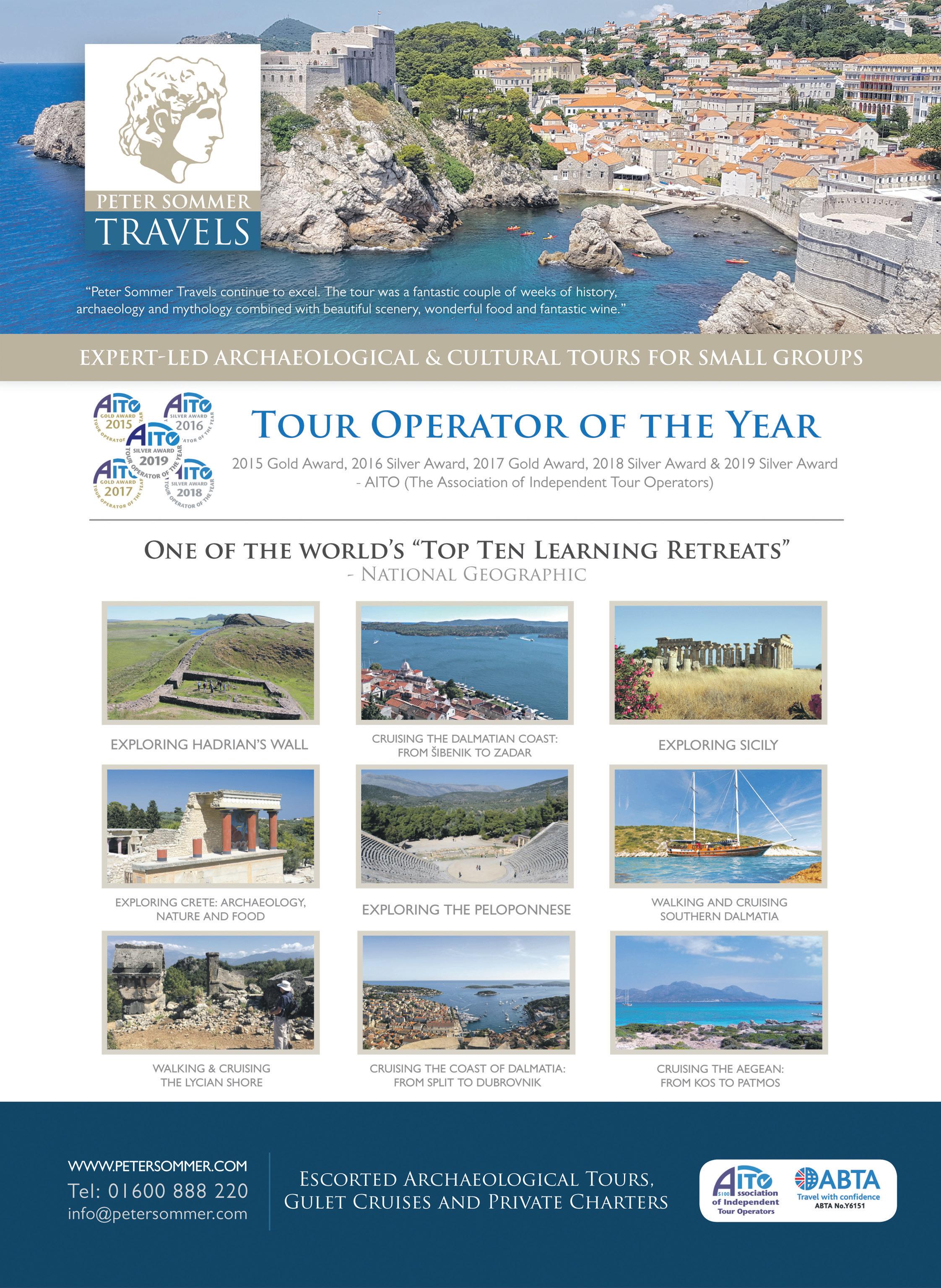

The magazine for BMA members

Out of hours Proper investment could transform struggling services

Out of hours Proper investment could transform struggling services

Computer says no High hopes or a daily drag with NHS IT?

Heating or eating Austerity’s grim legacy for patients’ health

At a glance Doctors are working in ‘unsafe and undignifi ed’ conditions

4-9

Austerity’s legacy Drug misuse, and a stark choice between heating and eating, in the second part of our investigation

10-13

A digital dawn? Technology’s potential is vast, but the dayto-day reality remains very different 14-17

Breaking the chain Tackling the long shadow of domestic abuse 18-21

At the end of the line Out-of-hours GPs often face unsustainable pressures – but proper investment could transform the service 23

Your BMA Making Freedom to Speak Up guardians work for you

I was born into this NHS and, like many of you, have lived and breathed it for more than 40 years in service to patients at both extremes of age.

As professionals with expertise, we have repeatedly flagged the predictability and service needs during terrible winters, that are now all year round. This winter is a whole magnitude worse.

In this issue of The Doctor, we report on the desperate situation doctors face around the UK, with patients left in appalling and unsafe conditions in a health service under intolerable pressure, lacking the resources needed to provide even basic care. As junior doctors in England ballot for industrial action, we recognise that their fight for pay restoration is a barometer of the real value of all of us at a time when government policy is actively driving doctors to cut back or work abroad and an increase in moral injury leads to many saying enough is enough and packing up altogether.

While emergency departments cause shocking media headlines, the entire system is at breaking point. We look at the pressures faced by GP OOH (out-of-hours) services, such as in Gateshead where Paul Evans, having dealt with one complex case after another, says: ‘This could be the winter that finishes a lot of us in the NHS – that’s a terrifying prospect.’

In a country that has decimated its public health structures and starved general practice of investment, it is the OOH services, such as emergency departments, that have become the first rather than the last resort to some patients. Paul describes the effects of austerity as ‘massively significant’ and in the second part of our feature looking at its effect on Nottingham, the link between the cost-of-living crisis and poor health outcomes is made very clear. One doctor expects a spike in mental ill-health as those on ‘that teetering edge of being able to cope’ suddenly manage no more.

As BMA president Martin McKee puts it, doctors are ‘tired of picking up the pieces after government ministers, whose politics are harming health and placing our NHS under intolerable pressure’.

Following a recent BMA report showing that 13.5 million hours are being lost each year from inadequate IT systems and software, the equivalent of almost 8,000 fulltime doctors, we look at the gaping disparity between many everyday IT experiences and successful projects – there are some – where technology is saving time and improving care.

Finally, an interview with inspiring Merseyside GP Mairi Reid who knows at first hand that adverse childhood experiences can cast a long shadow throughout life and down generations as she helps patients break a cycle of abuse.

Keep in touch with the BMA online at instagram.com/thebma twitter.com/TheBMA

Hospital doctors have laid bare the perilous state of ‘broken’ emergency departments this winter, describing ‘unsafe and undignified’ conditions for patients.

Twelve hospitals declared critical incidents and some discharged patients to hotels as surges in COVID and flu exacerbated already creaking services working beyond capacity while GPs continued to face record demand.

There were 1,593 excess deaths in England and Wales in the week to 30 December. Deaths in hospitals were 14.8 per cent above the fiveyear average.

South Wales consultant gastroenterologist Peter Neville has seen patients in chairs, corridors and the back of ambulances queued outside emergency departments. ‘It’s always rammed,’ he told The Doctor. ‘The environment is increasingly intolerable to practise as a professional – and we’ve had this throughout the year. We’re assessing patients in environments simply not fit for purpose. It’s humiliating and degrading to ask somebody to take their shirt off in an open corridor.’

Noting ‘a lot more’ sick leave and burnout, he said: ‘I’ve never known it anywhere near as bad as now. Staff have had enough. If conditions don’t improve, the NHS will fall.’

Simon Walsh, deputy chair of the BMA consultants committee, said: ‘Staff are papering over the cracks. The reality is we’re delivering care in corridors, in spaces that weren’t designed for patients. The urgent and emergency care system is broken.’

NHS England’s December data shows 54,532 patients waited more than 12 hours in emergency

departments. There were 347,707 12-hour waits last year, four times that of the last 10 years combined.

Adrian Boyle, president of the Royal College of Emergency Medicine, said 300 to 500 people a week were dying owing to delays and problems with urgent and emergency care.

‘We need to increase capacity in hospitals,’ he said. ‘We cannot continue like this – it is unsafe and undignified.’

Rob Galloway, an emergency medicine consultant in the south of England, said: ‘If there were two plane crashes a week there would be COBRA meetings and we would have the Army in. A&Es are not just busy; they are dangerous and people are dying.

‘It’s the busiest I’ve seen in 22 years. COVID and flu were the straws that broke the camel’s back; it’s scary.’

The Government

announced an extra £250m ‘to speed up hospital discharge’ on 9 January but Dr Galloway said it was too late.

He suggested opening Nightingale Hospitals as care hubs and believes the only reason the Government hadn’t was because it would be ‘admitting failure’.

The crisis intensified as the BMA opened its industrial action ballot for junior doctors in England, calling for restoration of pay to 2008/09 levels; since then it has eroded by 26.1 per cent.

If junior doctors vote to strike, they will walk out for 72 hours in March. The ballot closes on 20 February.

In an area where drug misuse is common, and the stark choice between heating and eating even more so, an exhausted medical workforce does all it can, despite years of service cuts. In the concluding part of our investigation into the impact of austerity in one city, doctors tell Peter Blackburn why this is the hardest winter

‘The only time I will get help is when something really bad happens’

‘Some of these people I have been seeing for 10 years now,’ says Stephen Willott in his consultation room at The Windmill GP practice in Sneinton, just east of Nottingham City Centre.

The practice runs what is likely the biggest sharedcare drug clinic in the East Midlands.

For Dr Willott it is an opportunity to have an immediate effect on the lives of the most vulnerable patients in this city – but the complexity and tragedy of some patients’ lives and the

societal breakdown around them means sometimes harm reduction is as much as can be managed.

One patient is urged not to purchase the highly addictive and destructive crack cocaine alongside his daily heroin. This two-in-one phenomenon is a growing problem in Nottingham, Dr Willott says. ‘It is maybe the most prevalent now. And it is very dangerous.’

Another patient presents for his ‘pretty significant’ methadone prescription – an insurance policy that should ‘take the chaos’ and the ‘illicit means of getting drugs’ away from his life.

Next, we see a patient whose leg is so swollen the doctor’s fingers leave deep impressions in the flesh when making an assessment. He appears to be in a slight daze and says he has just had some mamba. Asked how he is finding life, he says: ‘It is just getting harder.’

For some people in this city using mamba is the easiest method of escapism. Mamba, in comparison to many drugs,

is relatively cheap and it will remove users from full consciousness for a period of time, but Dr Willott says it is largely a ‘pleasureless’ drug where users are just ‘out of it’ rather than having a ‘nice high’. This, many health professionals have said to The Doctor, is among the most depressing indictments on the state of society –that escapism without any pleasure is desired.

After working through patients unable to come to the surgery in person and others seeking prescriptions The Doctor meets a homeless patient who is at his wits’ end, having been unable to satisfy any landlords that he could pay their rents with the benefits available to him. He says: ‘I’ve given up. It’s a waste of time. The only time I will get help is when something really bad happens. Everywhere I go nobody is interested. Maybe they will be when I’m dead.’

Several more patients file in and out. The personal circumstances seem to get bleaker with each visit. One

of Dr Willott’s patients – a working-age heroin addict – died two days ago. And another supplied a urine test which glowed scarlet red in the bottle owing to being almost entirely made up of blood. The everyday horrors of many patients’ lives are beyond a nightmare for most in society.

A final patient for the day arrives. He is happy to talk but is not well. He can’t lift his arm, he has a ‘massive abscess’ on one of his legs and half of his jaw has rotted away. He has just two teeth left. The patient’s brother died recently after taking mamba. After three years on the streets he now has a flat and found services were more supportive following the death of his brother. Asked about the future, he says: ‘Life is very tough. Cost of living? It’s the cost of just surviving, more like.’

Reflecting on another day in the clinic, Dr Willott, who is chair of the local drug deaths group, describes the reality of operating in a post-austerity health system with these patients as ‘increasingly brutal with each successive year’.

The patients here are cared for with great compassion and dedication but when housing is so difficult to access, other drug and alcohol services have disappeared and society seems to have forgotten them, it is difficult to do much more than manage and cope. And, sadly, with Dr Willott and his colleagues running these dedicated clinics in Nottingham, these patients are catered for in a way that many around the country are not. Dr Willott says 50 per cent of the drug deaths each year are of patients who are not in any treatment whatsoever, and that there is a crisis in people not being engaged with services.

That sense of a postcode lottery is familiar across the city at The Level, in Radford, which sits among the relics of what was once the industrial heartbeat of this city – among the former factories that made millions of Raleigh bikes and the famous Player’s tobacco empire. The Level is run by local housing charity Framework and works in partnership with Nottinghamshire Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust and a number of other charities and local organisations. It was set up in 2018 after the NHS’s substance misuse service, The Woodlands, at the Highbury Hospital in the north of the city, closed down to make financial savings. These sorts of services are now few and far between – patients at The Level come, literally, from right across the country but there are only a small number of beds to go around. GP Marcus Bicknell, who works there, says the 2012 Health and Social Care Act left services

vulnerable to budget cuts and describes the effects as a ‘massive harm’. There are now only a handful – a count of five in 2020 – of inpatient units in the country and the health service’s addiction psychiatrist workforce has been decimated.

The traumas stored in people’s lives across this city are immeasurable. Much of that trauma is created in early life, growing up in communities where poverty is normal and support unheard of. Doctors working at places such as The Windmill, Dr Willott’s practice, and The Level already fear for their populations and now the worry of what is to come echoes loudly around the estates in Nottingham.

Those fears appear to be justified. High inflation, currently around 10 per cent, is making the cost of living increasingly unaffordable. Lower income households, who are already at a greater risk of ill-health, are bearing the brunt of this as cost increases represent a greater share of their income and Citizens Advice has reported a tripling of people seeking help because they couldn’t afford both food and energy. In a grim summary of the situation one homeless person The Doctor meets jokes the energy crisis is perhaps not the worst time to have no home to heat.

Last year, 4.5 million UK households were fuel poor, and this had significant health implications, with England recording an estimated 63,000 excess winter deaths in 2020-21. Estimates suggest that 10 per cent of excess winter deaths are directly attributable to fuel

‘Cost of living? It’s the cost of just surviving, more like’

‘Increasingly brutal [conditions] with each successive year’’

poverty and 21.5 per cent are attributable to cold homes. Even with the Government’s cap on energy costs, National Energy Action is warning fuelpoverty numbers will rise to 6.7 million this winter.

Households with children have the highest prevalence of fuel poverty and cold homes are associated with reduced resistance to respiratory infections, including bronchiolitis, in children. Respiratory illnesses are more than twice as high in children who had lived in cold, damp homes.

In September, 18 per cent – 9.7 million adults – of all households were food insecure, meaning they ate less or went a day without eating because they couldn’t access or afford it. This has more than doubled since last January. And one in four households with children have experienced food insecurity in the past month, affecting an estimated four million children. This food insecurity is known to lead to adverse health outcomes – causing malnutrition and obesity, one of the leading drivers of preventable illness and death, because healthy food, pound for pound, is much more expensive. The problems with food insecurity are mental as well as physical as the risk of mental ill-health from food insecurity is three times that of losing a job.

During the last financial year, the Trussell Trust supplied 2.2 million three-day emergency parcels – a yearon-year increase of 14 per cent.

At The Chase, a neighbourhood centre which

includes a food bank, adviser and community engagement worker Rachel Graham says the need is so severe now that the centre is overwhelmed, and staff often have to direct people to Citizens Advice instead.

‘We’ve seen people with good jobs lose their jobs and their homes,’ she says. ‘For these people to come to a place like this is terrifying. It is also impacting on people who are working. We anticipate this winter being a scary time –that question, heat or eat, will become an increasing issue. We are seeing this.’

Nottingham GP Jane Turrill says: ‘I think it [the cost-ofliving crisis] will push more people into that position [mental health crisis].

‘Ultimately, we will have people who are on that teetering edge of being able to cope and, suddenly, they’re not going to be able to cope

any more… You look at the price of food and heating and all that sort of stuff. And we know people’s rents have gone up… that puts people under a massive, massive pressure. I do think it will bring many more people into that arena of being more complex… I think that in terms of sheer numbers it is going to have a big impact.’

Dr Bicknell adds: ‘I am very worried about this bit of

TURRILL: Costof-living crisis will push people over the edge

‘That question, heat or eat, will become an increasing issue’

HOUSING

NHS spends at least £2.5bn a year treating illnesses linked to damp and poor housing

related diseases cost £6.5bn each year

MALNUTRITION

costs the NHS in England £19.6bn

austerity now… the worst is still to come even after everything we have seen. The fact that we’ve had these 12 or 14 years but the worst is still ahead of us is pretty terrifying really. It’s starve or freeze for many.’

Demand for services Austerity, and the inequalities it has driven, have a huge effect on the NHS. There is a record of more than seven million people waiting for treatment, including 2.75 million patients waiting more than 18 weeks. Last year, waiting lists increased by more than half, 55 per cent, in the most deprived areas, compared with a third in the least. Those in the most deprived areas were almost twice as likely to wait more than a year for treatment compared with those living in the least-deprived areas.

The treatment and care of people living with often preventable, long-term conditions are responsible for around 50 per cent of GP appointments and 70 per cent of hospital days. GPs and other healthcare professionals also report they spend around 20 per cent of their time dealing with issues which are nonmedical but related to social or

economic pressures.

It is likely higher levels of fuel poverty will make things worse – the NHS will likely incur higher demand and higher costs from its effects. In 2019, it was estimated the NHS spends at least £2.5bn per year on treating illnesses directly linked to cold, damp, and dangerous homes. And greater food insecurity will also add to pressures. Malnutrition is already estimated to cost the NHS in England £19.6bn. Obesity-related diseases are estimated to cost £6.5bn each year. There were already more than one million hospital admissions owing to obesity in 2019/20. International evidence shows those experiencing severe food insecurity have healthcare costs which are 121 per cent higher.

The cost-of-living crisis is also likely to lead to a rise in demand for emergency and mental health care during the coming winter, including an above 10 per cent increase in inpatient mental health admissions and above 5 per cent increases in outpatient mental health contacts, 111 and 999 calls. Above 5 per cent additional funding would be required for mental health and emergency department services to cope.

It is not just the most obvious links between austerity and health which are causing great strain, however. Bob Winter worked as medical director for the East Midlands ambulance service, national clinical director for critical care and emergency and clinical lead in the emergency department at Nottingham’s Queen’s Medical Centre during

the past decade, retiring last year.

He says: ‘In hospital we saw an increase in knife crime and an increase in substance misuse. There’s not the safety net and there’s a disengagement of society that didn’t exist before. We are seeing younger and younger people involved in violent crime. If you had told me 10 years ago that we would be teaching nightclub doormen and McDonald’s staff how to manage a life-threatening haemorrhage, I wouldn’t have believed you… I would have laughed in your face. But that is where we are.’

On top of that, the NHS workforce is depleted and exhausted by more than a decade of working in underresourced environments, with punitive pension taxes hanging over them and the ever-increasing risks of corridor medicine with patients locked in hospital owing to a spiralling crisis in social care.

The week The Doctor met Dr Winter, Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust, which runs the city’s QMC and City Hospital, declared a critical incident –an occurrence which was once highly unusual but now seems to be almost normalised. According to an email seen by The Doctor staff were offered 30 per cent incentives to go and do extra shifts, such was the desperation of hospital managers.

Dr Winter – who jokes that he realised he needed to retire last year when he answered a bleep for a red trauma call in the middle of the night only

‘We saw an increase in knife crime and substance misuse’MCKEE: We face the return of failed austerity policies

to realise when he arrived at the hospital that he wasn’t even on call – says: ‘High-level alerts are so normal now that you just read the email and shrug. There’s an element of “what do you expect me to do about it?” You get compassion fatigue. My big concern is we are normalising all of this.’

For Dr Winter, investment in the care sector and solving the pensions crisis, which is seeing clinicians give up work to avoid charges of thousands of pounds, are the easiest first steps to turning around some of these problems. He says: ‘I remember not that long ago a four-hour breach had managers jumping up and down. That’s not the case now. We have patients across the board waiting more than 24 hours to be offloaded from an ambulance. There’s nowhere to put the patients.’

Left behind Professor Martin McKee, the president of the BMA, says: ‘Doctors are tired. But it’s not just the long hours and heavy workloads. They are tired of picking up the pieces after Government ministers whose policies are harming health and placing our NHS under unsustainable pressure. And now, as ministers seek to balance the books, we face the return to the failed policies of austerity that created many of the problems we face today.’

The BMA is calling on the Government to take ‘urgent action’ to halt the decline in the country’s health. Its proposals include upholding commitments to uprating benefits in line with inflation, exploring reforms to social security and wages to ensure both guarantee everyone

access to the income they need to stay healthy and well and a commitment to uprating budgets so public services can cope with inflation.

In the longer term, the association is also urging ministers to plan to reverse the damage done by cuts over the last decade, to commit to keeping in place successful policy pledges on the drivers of ill health such as the softdrinks levy and to publish and act on a health inequalities strategy that makes health a cross-government policy.

Professor McKee adds: ‘Britain can’t afford to get sicker. When it came to power in 2010 the coalition Government chose to implement severe austerity. The first signs of economic recovery following the financial crisis were snuffed out. Government policies left entire communities behind.’

There is a huge amount of work going on across the city in a bid to hold together the remaining fragments of the social safety net and to work with the most deprived and vulnerable communities to improve their health and wellbeing.

Last year, The Doctor was invited to a meeting of Nottingham’s SMD (severe multiple disadvantage) Partnership – a group of 40 to 50 staff and service users from health and social care, charities and other groups meeting every two weeks – which aims to support people facing a combination of homelessness, substance misuse, domestic abuse, offending and mental ill-health.

It was a group in which the hope for the future belied the

difficult context cities such as Nottingham are operating in. The group has convinced the city council to have SMD as a priority for the local health and wellbeing plan and political and professional support seems aligned.

Professionals in the city are rolling out a programme which aims to see GP surgeries across the area provide enhanced services for the most disadvantaged among their populations and a vast new project, Changing Futures, is aiming to drive system change with these communities in mind.

Jane Bethea, a public health specialty registrar with Nottinghamshire Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust, chairs the meeting. She says: ‘I think I’m the most optimistic I’ve ever been… and I’m quite a cynic.’

Dr Bethea cites the work of the volunteer and community organisations in the city and the willingness of health and care professionals to work together. The optimism is much-needed in a city where so much has been lost – and there is so much work to do to protect and improve people’s health, yet so little resource to do it with.

WINTER: ‘My big concern is we are normalising all of this’

‘Government policies left entire communities behind’

Technology has the potential for transformative change but the day-to-day reality can be deeply frustrating. Ben Ireland asks what it will take to produce a successfully digitised NHS at last

Utopian visions of seamless futuristic healthcare imagine slick systems which allow doctors to spend more time with patients and offer increasingly holistic care.

It’s a fine theory. But talk to today’s healthcare professionals and their reality is infuriatingly slow computers, when they don’t crash, often providing incomplete patient data. Doctors can be left sifting through paper-based records to fill gaps. Some question whether technology really helps.

The BMA report Getting IT Right found more than 13.5 million working hours are being lost each year from inadequate IT systems and hardware in England alone, the equivalent of almost 8,000 full-time doctors. In monetary terms, that’s nearly £1bn – or roughly the cost of restoring junior doctors’ pay to 2008 levels.

Previous attempts to digitise the NHS – the world’s largest single set of such personal data – stretch back to New Labour. Various reviews suggesting overhauls have come and gone.

Yet with COVID lockdowns accelerating the uptake of digital technologies in everyday life for doctors and patients, plus the vaccination rollout leading to 30 million people now using the NHS App, could technology’s day in the NHS have finally arrived?

more efficient but ‘needed a clear central vision’ for all clinical, reporting and analytical staff. ‘Everybody needed to be part of the transition,’ he says.

Convincing them was the hardest step, he recalls. ‘There are hundreds of reasons for not doing something on this scale. The only way was to build a strong coalition that believes this is the right thing to do.’

One example is Dr Chaudhry’s weekly clinic for 80 patients, which offers test results online. ‘Before, about half of patients would phone the next day. Now, they don’t have to.’

There are also cost and environmental savings. Cambridge sends one million fewer letters and documents per year, saving £165,000 in printing and posting and £288,000 in staff phone call time.

In a 21-month period 296,183 PCR COVID test results went out, more than 19,700 vaccination appointments were booked across the Cambridgeshire & Peterborough ICS (Integrated Care System), estimated to have saved £53,500.

‘The NHS hasn’t invested in technology as it has been seen as risky ’

Phil Koczan, London GP and digital clinical champion for primary care digital transformation at NHS England, says changes must come one step at a time. But he believes a giant leap was made during COVID.

Doctors think so. More than 94 per cent of respondents to the BMA’s report agreed IT and digital can help tackle the now 7.1 million record backlog. More than half (57 per cent) believe the effects could be ‘significant’.

The Government agrees and – with a severe shortage of doctors and nurses, who take years to train – had set aside £2.1bn from the now-scrapped health and social care levy for digital transformation. Prime minister Rishi Sunak (who introduced the levy as chancellor) and current chancellor Jeremy Hunt (the former health secretary) have assured MPs the levy’s repeal will not reduce NHS funding; however, high inflation means budgets will be squeezed in real terms.

Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust was an early adopter of digital advancements and is graded level 7 (the highest) by HIMSS (Healthcare Information and Management Systems Society).

Chief clinical information officer Afzal Chaudhry, a consultant nephrologist, says the problem was identified 12 years ago. Systems were ‘barely adequate for what we were doing in 2010’ so ‘weren’t going to be adequate for 2015 or 2020’, he says.

For Dr Chaudhry, ‘glossy tech’ isn’t the point. Cambridge focused on making day-to-day workflows

‘If you go back four to five years, there was a lot of concern between GPs about sharing data. A lot of those concerns about whether sharing data or not is the right thing to do have gone. Now, it’s not about whether or not we share data but how we do it safely,’ he says.

‘Technology can do a lot more than we use it for. In the past the NHS hasn’t invested in technology as it has been seen as risky, and quite rightly we haven’t pushed the boundaries. What COVID has taught us is we need to maximise clinicians’ time – and make technology as easy as possible to use.’

A major issue the BMA’s report identifies is ‘interoperability’ – how different systems used across primary and secondary care (such as TPP’s SystmOne and EMIS) ‘talk’ to each other.

Doctors say they don’t. Asked for one change they want to see in the next five to 10 years, responses included ‘one IT system for all functions’ and ‘a nationalised NHS IT service accessible by primary and secondary care’.

The Government’s June Data Saves Lives policy paper promises this. It says: ‘We want a world where every person and the health and care professionals involved in their care can draw information from, or put information into, the same shared care record in a safe and straightforward way.’

But records come in different shapes and sizes. SCRs (summary care records), basic patient information created from GP records and readable by authorised staff

working

from NHS 111 to hospital doctors and nurses, are now available nationally.

Their scope was broadened in April 2020 in response to COVID to include more information such as resuscitation preferences and next of kin details. They also changed from opt-in to opt-out, which increased the number of records being accessed from three to four million to about 55 million.

GP Connect allows primary care practices to share SCRs with each other and book appointments for patients. Local agreements for using records for direct care were in place pre-COVID but have been extended nationwide. COVIDenforced changes remain in place until a permanent policy is confirmed. Primary care networks can also make their own data sharing agreements.

ShCRs (shared care records) introduced in April 2021 go further. An evolution of local health and care records, these allow all doctors within an ICS to not just view but add to records. This could be a GP uploading the outcome of a patient’s latest consultation or a hospital doctor sharing blood test or X-ray results.

All ICSs now have a ‘basic shared care record’ in place and the Government has promised all organisations within ICSs will have a ShCR that ‘meets the requirements’ by December 2024. This could involve social care too.

However, ShCRs are not national. So, a clinician treating a patient from Manchester in hospital in Cornwall while on holiday can only access the more basic SCR.

The BMA found 98 per cent of secondary care doctors and 81 per cent of primary care doctors encounter delays accessing data from the other. Only 30 per cent of doctors expect to be able to seamlessly and instantly access patient data in 10 years’ time. Improving interoperability is a ‘high priority’ for 74 per cent of respondents.

GP Diana Hunter, chair of Cambridgeshire local medical committee, has experienced long delays in receiving records from busy hospitals, citing waits of six to 12 weeks for MRI scans.

She gives the example of a discharge summary she received late one evening when she was new to her surgery: ‘The note said the patient was admitted because her husband was unwell. I knew she hadn’t been on one of the medications for some time, so asked a colleague who told me her husband died two

years ago. It was more than two years late.’

Dr Hunter is ‘broadly in favour’ of ShCRs but warns ‘information overload’ may cause delays and risks to patient safety. Systems are ‘only as good as the person putting the information in’, she says, pointing out GPs are the sole data controller in SCRs. ‘I can see the advantages to more people being able to add to the record, but it becomes massive. You risk missing key information within that. Missing things is the main thing we worry about in general practice. When you need information urgently it can make things more challenging.’

Claire Lambie, chief nurse information officer at NHS Gloucestershire CCG (clinical commissioning group), says COVID was ‘an opportunity to challenge the status quo’ on digital technology and wants ‘common sense’ changes to remain in place. But she accepts ‘we have gone from not enough information to too much’.

‘We need to work on data quality and appropriate data quantity. We need to ask ourselves why we are recording it. Is it to help the next clinician, or to prove we have done something? Clinicians on occasions may feel they have to wade through multiple pages to find the specific information they need, which may not even be there.’

Ms Lambie wants to see ReSPECT (recommended summary plan for emergency care and treatment), a record of how a patient would like to be treated in an emergency when they do not have the capacity to express choices, to be digitised and accessible nationwide. Most trusts have adopted this process, but in paper form or held digitally on local systems, she says.

‘The number of times these are not available when needed is too high,’ she says. ‘As a patient, I would expect that to be known wherever I present in the NHS.’

Chasing easy wins is the way to make tangible progress, says Ms Lambie. ‘Digital transformation has to solve a problem,’ she says. ‘If it’s not broken or can’t be improved, don’t muck about with it – there are plenty of other things that need transformation.’

Dr Koczan believes ‘low-hanging fruit’ comes at a local level. ‘A lot of record sharing is based on trust,’ he says. ‘And 80 to 90 per cent of care exists within the local health economy. Building something national would be nigh-on impossible and take years – but in London we have built a relatively comprehensive system quite quickly because we talk to each other.’

He believes ShCRs’ ‘richer record’ also helps by

‘We have gone from not enough information to too much’

13.5 million

hours are being lost each year from inadequate IT systems

4% of doctors believe the software provided is completely fit for purpose

involving a wider range of clinicians, in areas such as mental health and social care – but accepts the information overload argument. ‘We need to build a bit of intelligence into the system,’ he adds.

Dr Koczan envisions a system whereby doctors can check a basic record, but ‘drill down’ into specific data based on what the patient presents with.

‘Say I have a patient with diabetes; what is their blood pressure over time, their blood sugar readings, what medication led to that change? At the moment we only have some of the jigsaw.’

He wants to build on structured records, which are available through GP Connect. The latest data shows that while 107 million read-only records have been viewed, only 2.4 million structured records have. Those are from 70 per cent of GP practices, compared with 99 per cent sharing read-only records.

‘That sort of data is only just coming on board,’ says Dr Koczan. ‘We need to populate these systems. That’s why it’s so important to have standards in place early.’

ransom. You can’t fail to grow and mature the needs of a department because one group doesn’t want to move forward.’

On the other hand, he accepts: ‘You can have the best technology in the world but if your staff don’t want to use it, or it doesn’t fit with what you want to do, you won’t reap the benefits.’

‘If it’s not broken or can’t be improved don’t muck about with it’

This feeds back into the interoperability argument for a central IT ‘language’ – or common intermediary – that all systems can ‘talk’ in, allowing different programs to be designed to create specialised patient profiles.

Getting staff involved

One of the BMA report’s recommendations backs up Dr Koczan’s point. It wants the NHS to set standards for suppliers insisting their technology can operate in tandem with other providers’ systems.

Another of the report’s 31 recommendations is improving hardware for doctors, including upgrading inadequate equipment that risks patient safety and not sharing laptops and tablets between too many colleagues. Clinical leadership and involvement in digital transformation must also be encouraged and ensured, it adds. Only 11 per cent of doctors responding to the BMA report say they always have the necessary equipment for their role – and just 4 per cent believe software is completely fit for purpose.

Dr Chaudhry feels staff need to be encouraged when trusts take the digital plunge. ‘For some, change might seem insurmountable,’ he admits. ‘Some might even leave because they don’t want to face it. We don’t want to leave anybody behind but, equally, nobody gets to hold us to

Dr Chaudhry recalls Cambridge’s ‘difficult first year’ of transition in 2014. ‘It was turbulent because we were changing so much,’ he says. ‘There were [negative] articles in the press.’ But he is adamant: ‘If you work on it you can come out of that and end up much stronger.’

In terms of system breakdowns, there has been ‘one major episode’ in the last eight years at Cambridge, he says. To avoid such instances, he suggests: ‘Don’t build your house on sand. If the infrastructure is flawed, you’re going to have problems.’

Over time, Cambridge has become ‘more and more digitally mature’, Dr Chaudhry says. But he caveats there is ‘no end point’ for digital transformation, but ‘a continuous upward spiral of incredibly high-quality care underpinned by digital’.

He believes there has been ‘a lot more learning across the entire NHS’ than when Cambridge took the digital leap, which means trusts can see what comparable organisations have done to ‘determine their opportunities’.

Dr Chaudhry compares technology’s continuous evolution with medical progress: ‘Treatments change, things we used to do as major open operations are now in-clinic procedures.’

So for technology, such as medicine: ‘The journey stretches out into the future. In a way, that’s what hospitals always have been.’

As Dr Koczan puts it, digital transformation is a ‘neverending journey’.

OnlyEMMA BROWN KOCZAN: Digital transformation is a neverending journey

Mairi Reid was from a good family; her mother and stepfather were doctors.

At the age of 14, she became involved in an abusive relationship. The violence started within months and continued for 17 years. She told no one.

She left school at 16 and had two children by 20. She walked out many times, but always returned. ‘I always thought that if I changed something or did something better, I could make it stop,’ she says.

Years later, she summoned the courage to apply for an access course to medicine and won a place at medical school. Even then, she dropped out for 12 months and had to re-sit her first year because things were so difficult at home.

It was only when she graduated and got her first job that she felt strong enough to end the relationship for good – and start talking about what had happened.

‘The reason I felt I couldn’t tell anyone was not only fear about what would happen if I did, but also I was embarrassed. I felt I wasn’t the type of person that this should happen to. But it doesn’t just happen in the families we might expect it to.’

Dr Reid wants to start a deeper conversation within her profession about domestic abuse.

Stereotypes around who it affects are preventing some people from accessing help – and condemning others to be written off as lost causes.

Domestic violence and abuse is startlingly pervasive: 1.6 million women and 757,000 men experienced domestic abuse in the year leading up to COVID lockdowns, according to the Crime Survey for England and Wales 2020. Children under 16 are not included in these figures.

Then in the 12 months that followed, calls and contacts logged on Refuge’s National Domestic Abuse Helpline rose by 61 per cent, as lockdowns turned already tense households into pressure cookers.

Long-term consequences Research shows that ACEs (adverse childhood experiences), which include suffering or witnessing domestic violence, can lead to poor outcomes of every conceivable type: from heart disease to relationship difficulties, from diabetes to depression.

Abuse can cast a long shadow, throughout people’s lives and down the generations.

Dr Reid and her older children ‘have not escaped unscathed’. She still suffers flashbacks, anxiety, low self-esteem.

But she’s now a GP on Merseyside and happily remarried.

Dr Reid believes she survived because of her mum – ‘a very key reason why I am where I am today’ – and the support of her then GP. Though she said little about her situation, both women sensed her need.

‘I would never tell the full story but my GP knew some of it. She made time for me, recommended books, made me realise I

Domestic abuse can cast a long shadow, damaging the lifelong health of sufferers and their children. But the insidious cycle can be broken, as a GP who survived an abusive relationship tells Seren Boyd

‘I felt I wasn’t the type of person that this should happen to’REID: Felt forced to keep silent about an abusive relationship

could get somewhere with my life and get out. She always was my GP, but there was something beyond professional support that wasn’t judging.’ What made all the difference for Dr Reid – and a common denominator linking people who manage to overcome ACEs, according to research – were these positive, supportive relationships, ‘someone who’s always there for you’, as she puts it.

She’s proof that ACEs need not be a life sentence. Indeed, she insists that cycles can be broken, with the right support, at the right time.

Dr Reid is a fierce advocate of a pioneering service taking root in a number of boroughs across Merseyside, a partnership between Mersey Care NHS Foundation Trust and the local authorities.

The basic aim of BABS, the Building Attachment and Bonds Service, is to help parents with often high numbers of ACEs bond with their babies, by separating past from present struggles.

The wider goal is to break destructive cycles by building positive relationships –both between parent and child, and between vulnerable parents and health and social care services, and the wider system.

Seventy-five per cent of BABS families are also supported by children’s social care services. Statistically and stereotypically, many of these families are at higher risk of losing their babies into care. The number of newborn babies being taken into care has more than doubled over the past 10 years.

STRONG BONDS: BABS ‘safeguards’ parent-child relationships

But BABS founder, consultant clinical psychologist Lisa Marsland Hall, is adamant that parents should not be ‘judged on past cycles’. She believes the first ‘1,001 critical days’ of a child’s life (including pregnancy) offer parents a unique ‘window of opportunity’ to make changes and rewrite the past.

‘You’ll never be more vulnerable than when you have a baby: all the stuff you’ve buried for years resurfaces,’ says Dr Marsland Hall. ‘But a baby also brings new possibilities, hope, feelings of new beginnings. Most new parents, even vulnerable parents, are motivated to change.’

Key to BABS’ success is its multidisciplinary team, from psychologists and therapists to specialist health visitors and peer-support workers. The service is based in family hubs and children’s centres, not mental health departments. BABS’ focus is on relationships, encouragement and praise to help parents banish their ‘ghosts in the nursery’.

And the early signs are that change is happening. A blind study by the University of Liverpool found that in 75 per cent of BABS families, the infants of parents with very high ACEs were meeting their developmental milestones two years on. Another BABS study, published last year by Edge Hill University, found strong parent-infant bonds were linked to improved parental mental health, secure attachments and a reduction in vulnerability and risk factors.

need to understand that helping vulnerable families break ACEs involves

‘We

‘The focus is on [helping] parents to banish their “ghosts in the nursery”’

engaging with these families, going above and beyond in our work, removing the stigma, blame and shame which society puts on them,’ says Dr Marsland Hall.

‘We can’t support families to build good bonds with their babies if we don’t build good bonds with the parents. We as professionals are so focused on safeguarding risk that at times we lose sight of safeguarding the most important relationships. Parents who’ve had the worst start in life can still make great parents, with the right support being offered at the right time.’

Dr Marsland Hall and Dr Reid recognise doctors can play a role as advocates for more services such as BABS, which sadly are still relatively rare. A motion passed at the BMA’s 2022 annual representative meeting, backed by Dr Reid, called for more multi-agency collaborations such as BABS to support children and adults with ACEs.

Doctors are also important gatekeepers who can refer patients to services such as BABS, as Dr Reid herself has done. And, with specialist parent-infant mental health training such as that Dr Marsland Hall offers, clinicians can support vulnerable families directly to build bonds and break cycles.

But first, crucially, doctors need to be able to recognise and respond to the signs of domestic abuse. They need not only training but an awareness of their own unconscious bias, says Dr Reid.

She believes all specialties should have annual

safeguarding training so they ask the right questions, and ask those questions of everyone. They also need to learn to read between the hints and ‘the stories that don’t add up’.

‘What’s really damaging to a patient is if they share something – and even just alluding to abuse is huge for them – and you don’t pick up on that cue,’ says Dr Reid.

Most importantly, doctors need to be nonjudgemental, whatever people’s background or choices – just as Dr Reid’s own GP was. Twentyfive per cent of BABS’ parents ‘can be anyone and everyone, including millionaires’.

‘I think people look at relationships like mine and think, “Why don’t you just leave?”’ says Dr Reid. ‘But it’s complex. I was very young, I had young children, and I didn’t know how I’d cope on my own.

‘It’s very hard to break free. You may feel it’s your fault, or you can change the situation, or you don’t want to abandon that person. Or you may fear they’ll harm themselves, or kill you, or keep the children. There’s always a reason to stay.

‘It is difficult as a GP when you’ve only got 10 minutes per patient, but I always try to fit these patients in and take their calls. I don’t talk about my background; I don’t feel that’s appropriate. But I do everything I can to give them support and be their cheerleader.

‘Everybody has vulnerable complex patients and it’s easy to get to a point where you don’t feel you can help them any more. But we have to keep trying to believe in them, so they believe in themselves.’

‘It is difficult as a GP when you’ve only got 10 minutes per patient, but I always try to fit these patients in and take their calls’

‘You’ll never be more vulnerable than when you have a baby’MARSLAND HALL: ‘We can’t support families to build good bonds with their babies if we don’t build good bonds with the parents’

NEIL HODGE

NEIL HODGE

EVANS: ‘ We will see so many excess deaths’

is not

unsustainable

Between sips of inky-black canteen coffee in Gateshead’s QEH (Queen Elizabeth Hospital), GP Paul Evans sums up the polarising feelings which arise just minutes before logging on at midday on a Saturday for yet another OOH (out-of-hours) shift.

‘There’s always a sense of trepidation because you don’t know what the shift is going to bring,’ Dr Evans says. ‘But there’s often something very satisfying about interactions where you can make a quick and obvious difference to a patient right there and then.’

Dr Evans works for the Gatdoc urgent primary care service in Gateshead, which operates from a few consulting rooms at the outpatient department at the QEH. The service has been running since 1994 and relies on local GPs stepping up to take on shifts and support communities when they aren’t able to access mainstream primary care.

deals with each at what seems a remarkable tempo – each question quickly triaging and assessing while fiercely pinpointing where the patient might need to be seen and what steps to take next.

‘This could be the winter that finishes a lot of us in the NHS’

In the space of just eight minutes the first patient – a 52-year-old with incredibly complex medical history, including taking upwards of 40 tablets and drinking a bottle of wine every day, and now presenting with chest pain, lack of feeling in her legs, swelling and breathlessness – has an ambulance arranged and clearly feels understood and reassured. Dr Evans is ‘greatly concerned’ but has done everything he can –and with real urgency.

The way Dr Evans talks about working in OOH care seems to betray his background of having qualified as a GP in the military. He worked in the military for 11 years, before taking a salaried post at a practice which was largely responsible for the students at Durham University in the heart of the cathedral city, locuming for a while and then settling at a small practice in deprived central Gateshead, and gives off a sense of being more comfortable in chaos than most – ready to embrace whatever comes next, armed with the expertise and experience to impose himself on stressful situations.

Within seconds of having signed into the system, the patients begin to come thick and fast and Dr Evans

This area of medicine is marked by sheer variety, but it appears few calls are totally misplaced and most patients need face-to-face follow-ups. All are given times in the coming hours, depending on the level of urgency. One sounds like a gall-bladder issue and arrives in pain, another is carrying a football injury which needs scans, another requires help dressing a wound. While the nature of the patients’ needs are variable, there is one definitive thread running throughout: there is always someone waiting.

Much of Dr Evans’s work in this North East consulting room is reactive – urgent responses to problems that need immediate attention. Yet, as the patients come and go, it is also hard to avoid a growing sense that many patients might not be here, presenting to a strained OOH service, if things were

The intense and

pressure often faced by GPs working out of hours

inevitable. Peter Blackburn visited OOH services around the country and heard how proper investment could transform the experience for doctors and patients and alike

different in their communities. Many of Dr Evans’s patients feel like the tragic case studies of a society which has decimated its public health structures, failed to invest in routine general practice and where last-gasp parachutes such as food banks and OOH care are becoming all too routine.

‘The impact of austerity is massively significant,’ Dr Evans, who is also a BMA council member, says.

And this winter, with the NHS breaking at the seams, Dr Evans is deeply concerned for his patients and communities. ‘We will see so many excess deaths.’

One North East doctor who was asked to reflect on the situation in his area during the winter told The Doctor : ‘Patients are being treated in virtual wards for which the staff do not exist and they are supposed to get better in their own cold, grotty homes. This winter will be spectacularly bleak.’

In OOH care there is a tangible sense of the fate of doctors and services being at the whims of whatever is going on in the NHS and society. With freezing temperatures, soaring respiratory viruses and an NHS struggling to cope Dr Evans fears the effects of this winter could be catastrophic for the future. He says: ‘This could be the winter that finishes a lot of us in the NHS – that’s a terrifying prospect. We are working through this winter with none of the “all in it together” spirit that we have had before. People are spent.’

It is no exaggeration. On 18 December, BMA Northern Ireland GPs committee chair Alan Stout tweeted there were nearly 400 calls in Belfast alone

to be returned, with just two GPs working OOH. ‘Huge and unsafe pressure,’ he said. Similar warnings can be heard across the UK.

The questions of the sustainability of this situation are pertinent. Dr Evans, to at least some extent, thrives in the pressure and adversity but for most doctors this sort of workload and intensity would be too demanding to be realistic in the long term. Even Dr Evans, who admits he has an abnormal tolerance for pressure, sometimes goes home after a shift and needs time to reflect and recover, describing himself as ‘absolutely shattered’.

The Doctor received a text in the second week of December that reaffirms the sense of the successes and failures of OOH care being so contingent on the demands elsewhere on the NHS. It says: ‘Never known OOH to be so busy. Thirty-five patients when I came in… A&E standing room only.’

The sender, East London GP Selvaseelan Selvarajah, is one of the clinical leads for the OOH service which runs at Homerton hospital. The most shocking aspect is that Dr Selvarajah’s service is usually able to manage demand well. When The Doctor visited in November patients were supported quickly and efficiently. There was no sense of this being an NHS in which patients having heart attacks at home were waiting hours for ambulances.

The driving force behind this demand was an outbreak of Streptococcus A, heavily covered by the media and frightening parents and families across the country.

‘This winter could be spectacularly bleak’

Doctors around England reported huge increases in demand from those who genuinely needed support and a significant influx of people who did not seem equipped to self care with relatively minor viruses.

Dr Selvarajah’s assessment is that this is a health service which has ‘missed the lessons’ of the COVID-19 pandemic. Those failings, he says, are a lack of investment in public health and primary care, national campaigns for parents and better support for schools. He adds: ‘Instead it’s fallen on the NHS to tackle this. So, at a time when we are so busy, this has added to additional pressures.’

In normal times it is a much more calm affair in OOH at Homerton University Hospital. Dr Selvarajah, who is also a BMA council member, describes a local structure and system which is able to function effectively because of mature, long-standing relationships between staff and provider organisations and a strong sense of what local people need running through services.

Dr Selvarajah is, however, acutely aware that around the country conditions in OOH care can be much more difficult, it can be incredibly hard to find the doctors to work the necessary shifts and demand from patients in some areas is astronomical.

For Dr Selvarajah a potential answer to the struggles doctors face in OOH care across the country might lie in widescale reform of the system. He would like to see NHS 111 overhauled, with clinical pathways for call handlers removed and 111 integrated into GP OOH hubs, urgent treatment centres, admission avoidance services or others with clinicians supported by call handlers to triage in the first instance, rather than the duplication of triage and assessment that often exists in the system. He describes the way of doing things as ‘splintered’.

An industrial estate just a few hundred yards from Aston train station in the north-east of central Birmingham might seem a much less likely location for an OOH GP service than the local hospital trust – but among the builders’ merchants and car garages off Lichfield Road that is exactly what can be found. The facilities here are remarkable – a vast site containing call handlers, doctors and even a drive-through GP surgery with cars parking up outside consultation rooms transformed in a warehouse which seems like a medical McDonald’s.

Here, there is a sense that the system, as it is, is working relatively well in the face of great demand and dwindling resource. But for Fay Wilson, Birmingham

GP and medical director of the Badger organisation which runs the centre, there is a sense of frustration and eagerness to do more. The data shows demand is increasing but Dr Wilson and her colleagues are only funded to provide the level of service they used to in 2016 so can’t hire more staff and widen access.

‘We’ve never used anything like its capacity,’ Dr Wilson says, speaking about the drive-through GP surgery. ‘You could easily see 500 patients a day.’ There are 23 bookings commissioned each day. Dr Wilson confirms that there is the demand in the system to benefit from higher usage but that effectively all of that shortfall is ‘just waiting’ as things stand.

One of Dr Wilson’s visions is that the centre could effectively alleviate a significant amount of pressure on mainstream general practice by being able to see patients who request on-the-day access to primary care 24 hours a day, once built up. As is so often the case, the stumbling block to a potentially transformational project is resource.

Regardless of where you go in the country it seems the uniformity of rocketing demand and pressure on NHS services is matched by the ideas and the appetite among doctors to meet that need and drive change and improvement.

In a recent Daily Mail column denouncing health professionals taking strike action, health secretary Steve Barclay said his priority was patient safety and outlined his appetite to ‘get our NHS back on track’. Perhaps it is time ministers listened to those who know best to do just that.

‘We’ve never used anything like its capacity… you could easily see 500 patients a day’

Neat, discreet, affordable and elegant

A Stiltz Homelift can be installed into almost any room in your home.

A Stiltz is uniquely compact with the smallest model taking up just over half a square metre. At the touch of a button a Stiltz Homelift turns your now home into your forever home.

A Stiltz Homelifts Consultant can visit your property to help you plan the best location for your homelift. They can also answer any questions you might have, as can any of the friendly, UK-based phone team.

For a FREE brochure or no obligation survey give Stiltz Homelifts a call today!

I recently had the privilege of chairing a forum on duty of candour, an experience which allowed me to interact with many people with an interest in patient safety.

One of the lasting impressions the event left on me, however, was the realisation that, while one of the most critical factors to transparency in medicine is that of psychological safety, it remains an issue that is not talked about enough.

Whether it is in our workplaces or in the BMA, the ability to feel safe and secure enough to express our views and concerns is fundamentally critical to our own wellbeing and ultimately to that of our patients.

As the association’s representative body chair, it is my responsibility to ensure that the voices and views of the BMA’s more than 170,000 members are heard and adequately reflected, particularly at formal policymaking events such as the annual representative meeting.

It is only natural that differences of opinion will arise and while points of view that are discriminatory will never be tolerated, it should also never be the case that those holding a minority view feel unsafe and afraid to speak out. As RB chair, I am always eager to hear from you about ideas and suggestions that would allow the ARM to become a more inclusive event that encourages debate and openness by increasing everyone’s sense of psychological safety.

I believe that doing this will not only make our ARM fairer, but actually help to produce policy that is more representative and beneficial.

The ability to feel safe and secure in the workplace is clearly one of huge importance, particularly when personal or patient wellbeing is concerned.

Important strides have been made in recent years across the NHS, most notably in the form of the

The Doctor BMA House, Tavistock Square, London, WC1H 9JP. Tel: (020) 7387 4499

Email thedoctor@bma.org.uk Call a BMA adviser 0300 123 1233

@TheDrMagazine

@theBMA

introduction of Freedom to Speak Up guardians across trusts in England.

Despite such welcome changes, there is considerable evidence to suggest many doctors, from those in the early stages of their careers to even senior consultants, do not feel confident in making their feelings and concerns about important issues known.

To my mind, this speaks volumes about the extent to which many of us do not feel psychologically safe in our places of work. The obvious question therefore is what are trusts neglecting to do that might enhance their staff ’s sense of security?

The presence of speaking up guardians is clearly an advance, but these individuals are not a silver bullet, and their efficacy can depend on a number of factors, including whether they were appointed solely by management or in conjunction with staff.

Other considerations include whether staff in these roles are visible and known within their workplaces? Have they made the effort to introduce themselves, walk around the wards and get to know those they advocate for on first name terms?

To doctors – ask about your speak up guardian; they’re there for you. To those in leadership positions – get to know your frontline staff, listen to them, they’re the experts. If you would like to get in touch to share your ideas or views please write to me at RBChair@bma.org.uk

Dr Latifa Patel is chair of the BMA representative body

Editor: Neil Hallows (020) 7383 6321

Chief sub-editor: Chris Patterson

Senior staff writer: Peter Blackburn (020) 7874 7398

Staff writers: Tim Tonkin (020) 7383 6753 and Ben Ireland (020) 7383 6066

Scotland correspondent: Jennifer Trueland

The Doctor is published by the British Medical Association. The views expressed in it are not necessarily those of the BMA. It is available on subscription at £170 (UK) or £235 (non-UK) a year from the subscriptions department. All rights reserved. Except as permitted under current legislation, no part of this work may be photocopied, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the editor. Printed by William Gibbons. A copy may be obtained from the publishers on written request.

The Doctor is a supplement of The BMJ. Vol: 380 issue no: 8367 ISSN 2631-6412

Feature writer: Seren Boyd

Senior production editor: Lisa Bott-Hansson

Design: BMA creative services

Cover photograph: Getty Images

Read more from The Doctor online at bma.org.uk/thedoctor

Staff safety is paramount – they need the support of Freedom to Speak Up guardians