the doctor

Fresh impetus

Newly qualified doctors join industrial action

Mental health

Explaining the increase in detentions

Rebuilding society

Michael Marmot points the way to greater fairness

More than just a slogan

Better outcomes, safer care – the case for kindness at work

The magazine for BMA members Issue 58 | August 2023

3

At a glance

Junior doctors in England maintain the momentum of industrial action

4-7

Why be kind?

The ‘business case’ for being kind to colleagues and patients

8-11

Symptoms of a crisis

What lies behind the increase in Mental Health Act detentions?

12-13

A cure for a broken land

The raft of measures needed to tackle health inequalities

14-15

Lessons from a fragile life

A student with several medical conditions reflects on what she has learned and how it affects her treatment of others

16-17

Fairness for all

Why the profession should not allow itself to become divided

18-19

Not done yet

An American GP of 102, who has no plans for retirement

20-21

‘Be kind, do good’

Paying tribute to a doctor remembered for her decency and commitment to equality

22-23

A fair deal

Born in a gulag, a doctor dedicated to social justice

Welcome

Phil Banfield, BMA council chair

Phil Banfield, BMA council chair

In this edition of The Doctor magazine we pay tribute to former BMA representative body chair Anthea Mowat – a beloved colleague and friend whose passing has left an enormous hole in the lives of her loved ones and our profession. Anthea dedicated herself to others. She lived by the mantra ‘be kind, be true, be inclusive, do good’. The world would be a much better place if we all delivered on those values. The thoughts of everyone associated with the BMA go to Anthea’s family and friends at this diffi cult time, as they do to all of our colleagues who have lost loved ones.

This magazine prides itself on using investigative journalism to reveal injustice, hold power to account, and to advocate for our profession, our patients and our NHS. The latest piece in our series, Paucity of Esteem , does exactly that, exposing the parlous state of mental health services in this country. It reveals thousands more detentions of the most severely unwell patients under the Mental Health Act in recent years. The first part in this two-part investigation highlights a healthcare system so broken it can often only store unwell people up until they are in absolute crisis. As psychiatrist Andrew Molodynski says, this is a ‘vicious cycle and an unsustainable model’. This has to change.

Also in the August issue of The Doctor we interview Professor Sir Michael Marmot, find out his views on the state of health inequalities across the country and what his prescription for politicians is with an election, and a possible change of government, looming. And we cover the remarkable story of 102-year-old Gladys McGarey, an American GP, who enrolled in an all-female medical school in Philadelphia in 1939 and is still on a mission to improve people’s health all these decades later.

Elsewhere in the magazine, we hear the ‘business case’ for kindness in medicine and inspirational deafb lind medical student Alexandra Adams tells us about her harrowing near-death experiences. Deputy chair of council Emma Runswick also writes on the importance of international medical graduates to our workforce, our NHS and our society; fairness and justice again, something Anthea would be telling us is still unfi nished business.

In this issue

02 the doctor | August 2023

Keep in touch with the BMA online at instagram.com/thebma twitter.com/TheDrMagazine

AT A GLANCE

Junior doctors strike for fifth time

A new cohort of doctors has brought fresh impetus to junior doctor industrial action in the long-running dispute around pay and conditions.

The BMA insists the ‘final’ 6 per cent offer and lumpsum payment of £1,250 made by prime minister Rishi Sunak last month – which equates to a below-inflation

10 per cent uplift – is not credible.

The association is demanding the Government recognises years of pay erosion and commit to restoration of pay towards 2008 levels in real terms. A re-ballot to extend the industrial action mandate in England is open until 31 August.

Thousands of foundation year 1 doctors joined picket lines in England, including Jessica Chan and Georgina Knapman at St Thomas’ Hospital on Friday, 11 August, shortly before The Doctor went to press.

Dr Knapman said: ‘Five or six years ago, medicine was a well-paid graduate job. Now it’s not.’

Dr Chan said it had been ‘nerve-wracking’ and ‘demoralising’ coming into the profession amid a continuing dispute – and has already been asked to work a 69-hour week owing to staff shortages.

Hundreds of doctors rallied outside Downing Street on Friday afternoon.

Addressing his colleagues from the stage, BMA junior doctors committee co-chair Robert Laurenson said that doctors were sick and tired of the Government’s empty rhetoric and false promises over meeting the profession’s concerns on pay.

He said: ‘For 15 years we’ve been told to wait, that it’s “not a good time” that we’re “all in it together”. Now we are standing up for ourselves, standing up for our profession and our future and we’re fighting for

pay restoration [and] we will keep going until they get the message.’

The cost of industrial action was recently estimated by NHS Providers at £1bn – roughly the amount it would have taken to restore junior doctor pay. JDC member Arjan Singh said: ‘That money could have helped retain doctors and reduce waiting lists.’

Consultants in England are to walk out for the second time this month, with 48 hours of industrial action scheduled on 24 and 25 August. They have been offered a 6 per cent pay uplift and will strike again on 19 and 20 September if government continues to refuse to agree to talks or present a credible offer.

BMA consultants committee chair Vishal Sharma said 15 years of ‘asking nicely’ had failed because the pay review body is ‘rigged’.

Junior doctors in Scotland were voting in a consultative ballot on whether or not to accept the Scottish Government’s pay offer when The Doctor went to press. The BMA Scottish junior doctors committee recommended members accept the offer, of 17.5 per cent over two years and ‘a path towards pay restoration’.

In Wales, BMA Cymru rejected a 5 per cent pay offer for consultants, junior doctors, and staff, associate specialist and specialty doctors on the 2008 contract. Only the existing multi-year pay deal was offered to those on the 2021 SAS contract. Committees will consider whether to enter a trade dispute with the Welsh Government.

Doctors in Northern Ireland were told they will not receive the DDRB-recommended pay uplift offered to colleagues in England owing to funding shortfalls.

By Ben Ireland

the doctor | August 2023 03

bma.org.uk/thedoctor

A FAIR DEAL: Junior doctors picket outside University College Hospital London

SARAH TURTON

04 the doctor | August 2023 GETTY

WHY BE KIND?

It’s been described as an underground movement – a new approach to medicine attracting followers from across the globe.

It’s a radical concept that demands change in the way we treat one another and lead our organisations. Kindness is making a comeback.

This is not feel-good, fluffy stuff. Its advocates are making big claims about kindness’s potential to improve everything from staff performance to patient outcomes.

A growing number of organisations are prioritising kindness as an organisational strategy as well as a value. Hywel Dda University Health Board in West Wales, for example, now recruits to its nurse apprenticeship scheme based on applicants’ kindness, not their qualifications.

‘When we’re kind to people, it creates better relationships, we get better information from each other, we make better decisions, we perform better,’ says Chris Turner, the doctor behind the Civility Saves Lives campaign. ‘And if we treat patients compassionately, they do better too.’

But how can you ask an overstretched workforce to be kind? And how do you nurture kindness in a system that many feel has lost its heart?

The ‘business case’

Bob Klaber is director of strategy, research and innovation at Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust and a consultant general paediatrician. He helped set up the monthly online ‘Conversation for kindness’ which now attracts healthcare professionals and leaders from some 30 countries.

He believes that kindness is ‘at the heart of

outstanding care’. ‘Pretty much everything else flows from it,’ he says.

The ‘business case’ for kindness is compelling, backed by a growing body of evidence.

Kinder care has been associated with better outcomes in cancer patients in a study by US professor Leonard Berry into healthcare service quality.1 It has also been linked with faster healing of wounds, shorter hospital stays, and reduced pain, anxiety and blood pressure, according to research by Stanford University and Dignity Health. 2

And kindness need not take long: a study by Johns Hopkins University found that giving just 40 seconds of compassionate care – even a simple message such as ‘We’ll go through this together’ – can measurably lower a patient’s anxiety.

It can even save time: a randomised trial among homeless adults attending an emergency department found that those receiving compassionate care made a third fewer repeat visits within the month. 3

But there’s another reason why Bob advocates treating others in a way that values and respects them. He believes a focus on relationships and the relational has the potential to transform workplace culture and, by extension, staff morale.

‘Our country’s healthcare leaders’ dominant focus on policy, systems and processes, to the detriment of the emotional needs of our workforce, has persisted for too long,’ he says.

‘We have a massive workforce crisis whose roots are multifactorial but the way we’ve treated people is absolutely key,’ he says. ‘I’m not prepared to spend the rest of my career

the doctor | August 2023 05

The words may grace a million drinks coasters but there’s far more than sentiment to the invitation to ‘Be kind’. Seren Boyd hears from the people trying to embed kindness into everyday NHS working practices and with it, better outcomes and safer care

working in a system that’s inherently not psychologically safe, that is unkind.’

He cites a Google study, part of its Project Aristotle, which found psychological safety to be the most important condition needed for a team to be high performing.

‘I have found no better tool in creating that condition than a strong focus on kindness,’ he says.

Trusting environment

A regular contributor to the ‘Conversation for kindness’ is Dr Turner, a consultant in emergency medicine at University Hospitals Coventry and Warwickshire NHS Trust. He helps explain how kindness builds psychological safety.

Kindness, Dr Turner says, creates an atmosphere of trust that allows people to be vulnerable and ask for help when difficulties or dilemmas arise.

The more people can exchange feelings and ideas, the less they become isolated in their stress or distress. And the better the flow of information, the better their decisions, he believes.

‘In medicine, we’ve been absorbed in a culture of personal mastery. “I need to be able to cope, I need to be able to answer this straightaway.” But the answers don’t come from me on my own: they come from us collectively.

‘When we as individuals are viewed positively, particularly when we’re not seen as somebody who’s going to weaponise information or think “What a fool,” we help other people to turn on the flow of information and we can feed it back to them, to help them make sense of things or make decisions.’

But Dr Turner adds a word of warning: don’t make assumptions about how others perceive you. In his training with senior staff and health leaders, he often asks: ‘What’s your theme tune? What music do people hear when you walk in the room?’ Dr Turner was horrified to learn that at one time younger colleagues associated him with the soundtrack to Jaws –because of a miscommunication.

‘We need to think: “What theme tune would I like to have?” then “How should I behave so people hear that theme tune?”’

Work pressures

Yet, many will say, today’s NHS is not conducive to kindness. Dr Turner’s the first to admit that we can’t demand kindness of people in an unkind system.

‘We are hostage to our environment,’ he says. ‘You cannot expect people to be kind when you are driving them into the ground, when you get no space to be humane to each other.

‘At the moment, we’ve got a system that sometimes creates burnt-out cynics and that’s then role-modelled to others. Many very senior people are so burnt out they can’t see the impact they’re having on others. Kindness isn’t always achievable but we need to provide environments where people can be kind.’

But Dr Turner also believes that, despite the pressures, senior colleagues and health leaders have a responsibility to lead by example.

‘The more senior you are, the more influence you’re having, the greater the responsibility on you to set the behavioural tone within the organisation. Seniority doesn’t come with the privilege to behave as you like without accepting the impact this has. Our leadership behaviours are key to creating cultures of decency and kindness.’

Creating the culture

Maria Battle, chair of Hywel Dda University Health Board, says that the kindness movement in her organisation was born out of

BOB

KLABER: Kindness at heart of quality care

06 the doctor | August 2023

‘When we’re kind to people, it creates better relationships, we get better information from each other’

‘You cannot expect people to be kind when you are driving them into the ground’

BATTLE: Culture of care and kindness

staff values and pre-dates her arrival four years ago.

The health board’s HR department has led the charge, with a deliberate focus on recruiting for kindness and building ‘strong, understanding relationships’. The new organisational development relationship managers, recruited within the past year, embody this ambition.

Mrs Battle recognises that a compassionate culture is not built on wellbeing retreats, listening rooms, commendations and activebystander training alone, though these are all things her health board has instituted and they matter.

For her, it’s about creating a culture of care and kindness, and she takes her role championing this very seriously. She starts every job interview with the same question: ‘Give me an example of a spontaneous act of kindness that you’ve undertaken recently.’

‘It’s so important that leaders live their values, not preach them,’ she says. ‘We need to reach out, listen and keep listening, show we care and be visible.’

Translated into action

Bob Klaber at Imperial goes a step further: he believes that everyone – no matter their role or grade – has the power and potential to influence workplace or departmental culture. But they sometimes need reassurance that they have permission to live out their values.

‘I say to medical students on the wards, “People are watching you all the time for how you behave. They’re looking for your leadership.” Maybe we can’t change the political environment but think about what you can directly control and influence, and start there.’

Bob is keen to help colleagues translate values into practical action. Kindness features at the very top of the ‘organisational ethos, values and behaviours’ on Imperial’s website, and among the kindness habits listed are simple acts such as ‘making eye contact and smiling’ and ‘noticing when someone needs help’.

He is personally challenged by Prof Berry’s practical behaviours that can lead to better outcomes in cancer patients. These include ‘deep listening’ and ‘generous acts of discretionary effort that go beyond what

bma.org.uk/thedoctor

patients and families expect’.

One important practice that Bob is encouraging is being an active bystander, someone who challenges bad behaviour and stands up for values such as inclusiveness. This might mean asking people who are behaving unkindly, ‘What’s really going on for you?’

‘When we talk about kindness, people may say, “That’s all very well, but have you been down to Theatre 4? It’s toxic down there.” So, we’ve got to get down to Theatre 4 and say: “That behaviour is not acceptable.”’

Bob and his fellow kindness advocates are determinedly optimistic about the power and potential of kindness to change the culture – not least because it’s contagious. Kindness leads to more of the same.

‘You can teach it, you can learn it, you can practise it: everyone’s capable of it,’ says Bob. ‘Having a bad day might be context for how one is feeling, but ultimately, however one is feeling, kindness is a choice of action we can all choose to take.

‘Try it: hold the door open for somebody, rediscover a bit of joy by holding a patient’s hand, and see what happens.’

1 The Role of Kindness in Cancer Care, Journal of Oncology Practice, 2017 www.researchgate.net/publication/320439113_Role_of_Kindness_in_Cancer_Care

2 www.dignityhealth.org/about-us/press-center/press-releases/scientific-literature-review-with-stanford

3 www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS01406736(95)90975-3

‘You can teach it, you can learn it, you can practise it: everyone’s capable of it’

the doctor | August 2023 07

TURNER: Senior staff should lead by example

ED MOSS

PAUCITY OF ESTEEM

SYMPTOMS OF A CRISIS

Tom Burns will always remember the three or four times he ‘got it wrong’.

One of those occasions –among hundreds of ‘painful and distressing’ detentions he has made under the MHA (Mental Health Act) – was a 22-year-old hypomanic art student. ‘I was going to take her in,’ Professor Burns, a retired psychiatrist, recalls. ‘Her dad was desperate for her to stay out, she was desperate to stay out.

‘I let her stay out.

‘She killed herself that night.’

Professor Burns, emeritus professor at the University of Oxford, could hardly give a more powerful example of the seriousness of an assessment under the MHA – of the effect a decision whether to detain or not can have, and the extreme pressure on psychiatrists and other healthcare workers

making these choices.

The decisions – ultimately depriving someone of their liberty because they are so unwell and pose a risk to themselves or others – are always a ‘last resort’. Some doctors describe these moments as a ‘privilege’, others as ‘daunting’ and ‘emotionally demanding’. Each is a whirlwind of complexity –with a demanding cocktail of patient history and judgement required from clinicians.

This is the context for an investigation by The Doctor which shows there were thousands more detentions under the MHA in 2021/22 than in 2016/17, with analysis of NHS data highlighting a 16 per cent rise from 45,864 to 53,337, with year-on-year increases.

Through a number of interviews with leading psychiatrists and other healthcare professionals,

academics, charities and policy experts, The Doctor has built a picture of the reasons for the rise in seriously ill patients being detained – including the dismantling of the structures that for decades built in continuity of care for mental health patients.

Services overloaded Doctors reveal the effects of evolving drug misuse, austerity policies crippling deprived communities, and cuts to early intervention services as massive contributing factors.

Psychiatrists also paint a frightening picture of typical inner-city mental health hospitals, with huge rates of severe mental illness among those ‘contained’ on chaotic wards and the rate of acute illness now so high only those with the most worrying conditions are admitted.

On top of this, mental health professionals are

08 the doctor | August 2023

GETTY

‘If people don’t have timely access to care, they get more acutely ill and then come in crisis to the service’

Thousands more people have been detained under the Mental Health Act in recent years. In the first of a twopart feature Ben Ireland and Peter Blackburn investigate a healthcare system that is so ‘broken’ it stores unwell people up until they are in crisis

under pressure to find beds for those in the most severe crises, leading to many patients being discharged early, piling pressure on stretched community services with police forces now questioning their roles as they face staggering numbers of emergency mental health calls.

It is a perfect storm which we assess in detail across two features – the second of which focuses on societal factors and will appear in the next issue of the magazine.

Prof Burns says a typical ward of 20 patients today might have 18 patients sectioned under the MHA. Twenty years ago, he says that would be closer to five. It is, he says, ‘much more overwhelming’ for clinicians.

Sir Robin Murray, professor of psychiatric research at the Institute of Psychiatry at King’s College London, says: ‘In order to get into one of these beds,

you have to be very ill.’

He describes crumbling wards ‘full of almost everybody being acutely psychotic’, as a ‘very unpleasant’ environment in which patients ‘can interact and make each other worse’.

Swaran Singh, a professor of social psychiatry in Warwickshire, agrees and describes wards as ‘places of containment’ because of the lack of resourcing where ‘we provide no care, no compassion’.

The extreme threshold to be admitted to acute wards means there is no space for some patients in severe states of crisis, those who would have been admitted for treatment in years gone by, or they are sent out of area. Psychiatrists also spend more time dealing with court hearings and have less time for hands-on care.

BMA analysis of NHS data shows the number of NHS mental health beds in England

dropped by 24 per cent from 23,607 in the fourth quarter of 2010/11 to 18,029 in the same period of 2022/23.

Low bed stock

At the same time occupancy rates have flatlined between 87 and 90 per cent, above the 85 per cent ‘risk threshold’, the level generally considered to be the point beyond which safety and efficiency are at risk. Meanwhile, mental health referrals have soared from three million in 2016, when comparable records began, to a staggering record 4.6 million in 2022.

Veena Raleigh, an epidemiologist at the King’s Fund, says NHS bed stock has consistently been lower than other comparable countries for years. In 2021, according to the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, rates stood at 0.34 psychiatric beds per 1,000 people compared with 1.31 in Germany, 2.58 in Japan, and 0.61 in Poland.

‘Services are overstretched,’ she says. ‘And if people don’t have timely access to care, they can get more acutely ill and then come in crisis to the service.’

Dr Raleigh says the ‘supply side issue’ means ‘there are long lead times to access mental health services’.

The system, it seems, is storing up unwell people until they are in absolute crisis.

AMHPs (approved mental health professionals) are responsible for coordinating MHA assessments and detentions with the consultation of doctors.

Greater Manchester-based social worker Christina Cheney, chair of the National AMHP

the doctor | August 2023 09

MURRAY: ‘In order to get into one of these beds, you have to be very ill’

‘Recent reductions in NHS beds have gone too far’

RALEIGH: Bed stock lower than comparable countries

SINGH: Wards have become ‘places of containment’

NHS beds down while referrals soar

NHS mental health beds dropped by 24 per cent from 23,607 in the fourth quarter of 2010/11 to 18,029 in the fourth quarter of 2022/23

Mental health referrals have soared from 3 million in 2016 to 4.6 million in 2022

The growing number of detentions under the Mental Health Act

Leads Network, reports ‘a pattern of people cycling in and out of hospital’.

She says the lack of beds means ‘people come in too late and are discharged too soon, to make space’ which results in more requests to assess people for detention shortly after they have been discharged from hospital as they ‘very quickly become unwell again’.

As a result, working in acute services becomes ‘ever more pressured’ so recruiting and retaining staff becomes increasingly difficult, and ‘capacity decreases again’ which ‘repeats the impact’.

For patients and staff these horrendous cycles are deeply damaging.

More patients than ever are being treated by a smaller workforce. Vacancy rates of medical professionals working in mental health services have been above 11 per cent since 2017, and now stand at 14 per cent.

Admission threshold

Lade Smith, president of the Royal College of Psychiatrists, says often the ‘threshold for coming in is so high that you only get in if you’re detained’.

One statistic perhaps

exposes the state of things more powerfully than any other. Detentions on admission to hospital have risen by 25 per cent since 2017/18 and now make up nearly two thirds of detentions, while detentions following admission have fallen by 22 per cent.

It is a stark situation where people are so unwell when they get to hospital that there is no time to see if their condition escalates, or if they can be managed without detention, Dr Smith says.

And Sir Robin, who cares for patients within the National Psychosis Unit at South London and Maudsley NHS Trust, says conditions are so ‘unpleasant’ that people immediately want to leave and are detained when they try.

As a result of pressures in acute wards, problems are pushed back into community services, where staff deal with patients with increasingly severe conditions and, as a consequence, cannot offer therapeutic or preventive services to as many people with milder symptoms. Without early intervention, those patients’ conditions worsen and become severe while others are simply not seen.

Look Ahead, a charity working in East London and Kent, works with patients who have been discharged from hospital. It reports a rising level of acuity among patients amid a wider NHS ‘strategy’ to keep people out of hospital.

Angelina Morgan, the charity’s director of complex specialist services, says hospital bed pressures also mean a growing number of patients being discharged ‘who are not well’ and would previously have stayed in hospital for longer.

This results in some psychotic patients living in the same supported housing as people ‘at other points in their recovery’, increasing pressure on staff.

A lack of hospital beds

CHENEY: Work becoming ever more pressured

10 the doctor | August 2023

‘If a psychiatrist knows you, he or she is much better placed to judge whether you really do need to be in hospital’

2016-17 45,864 2017-18 49,551 2018-19 49,988 2019-20 50,893 2020-21 53,239 2021-22 53,337

SOURCE: NHS DIGITAL. FIGURES REFER TO ENGLAND

hasn’t happened by accident. Successive governments have driven reductions. Alongside this trend, CTOs (community treatment orders) were introduced in 2008 in an apparent bid to reduce the number of so-called ‘revolvingdoor’ patients and free up those inpatient beds.

They can be applied to people detained under the MHA who are unlikely to pose a risk to others. Use of CTOs peaked in 2020/21, when 6,070 were issued – and 10 per cent (621) of patients were recalled to hospital – but dropped to 5,552 in 2021/22.

However, Prof Burns, who wrote a paper on their use with BMA consultants committee mental health lead Andrew Molodynski, says there is ‘no evidence that they work’.

‘If someone needs to be detained, get them to hospital and treat them,’ he says. ‘To deprive someone of their liberty when they’re well enough to be out of hospital poses an ethical challenge.’

Ms Cheney also wants a rethink on the use of CTOs. She says they have ‘no impact’ on numbers of detentions and suggests they are a back-door mechanism by which ‘compulsory powers are being extended long after an admission is ended’.

Among the most critical factors driving the rise in detentions, psychiatrists say, is the ‘steady decline’ of continuity of care over the last two decades.

‘If a psychiatrist knows you, he or she is much better placed to judge whether you really do need to be in hospital or whether you would manage at home,’ Sir Robin says.

‘Someone seeing you for

bma.org.uk/thedoctor

‘Increasing pressures mean more staff burn out and conditions only get worse. It’s a vicious cycle and an unsustainable model’

the first time starts entirely afresh and may be more alarmed than necessary.’

Continuity of care lost

Dr Smith says the landscape has changed from a model whereby patients would be looked after long-term by the same team, under the overall responsibility of the same consultant – whether they were in hospital or the community.

That meant teams would ‘get to know the patient really well’ and ‘step up support’ when necessary – either seeing them more often or prescribing appropriate medication.

‘It helped keep people out of hospital,’ says Dr Smith, who practises in South London. ‘And if they did need to come in, you would bring them in earlier, informally. Then when people were in hospital, you could bring them out quicker, knowing you’d be there to watch them.’

Dr Molodynski says: ‘This investigation shows how nearly every mental health patient in hospital is detained now, in what are often not therapeutic, but noisy, busy, austere, and coercive environments.

‘The deinstitutionalisation

of the UK over many decades has been a remarkable achievement, but recent reductions in NHS mental health beds have gone too far.

‘People are often discharged much earlier into their recovery because of the lack of beds. Riskier patients are being treated in the community, which is now separated from inpatient care, hindering vital continuity.

‘Increasing pressures mean more staff burn out and conditions only get worse. It’s a vicious cycle and an unsustainable model, as we are increasingly seeing.’

For Prof Burns that model of continuity of care, which he says is ‘vastly more important’ to mental health than physical health, is crucial.

He wants clinicians to have more autonomy to create multidisciplinary teams that can get to know, and keep in touch with, patients. Those relationships between clinicians and patients are of the utmost importance, he says.

Neither Prof Burns’ expertise nor motivation are in much doubt. Improving the system is about preventing illness and saving lives.

The potentially unnecessary suffering of every extra patient who becomes so unwell that they need an MHA assessment is a tragedy which also increases the burden on services and staff and, ultimately, the risk of mistakes.

Even in retirement he has never forgotten that 22-yearold art student and the three or four times he ‘got it wrong’.

Additional work by Claire Chivers and Olivia Clark

the doctor | August 2023 11

SMITH: Threshold for admission is very high

A CURE FOR A BROKEN LAND

Austerity had a terrible and disproportionate effect on the poorest members of society, says one of the country’s leading experts on health inequalities. Professor Sir Michael Marmot tells Peter Blackburn that a raft of measures, including action on child poverty, working conditions and climate, are urgently needed

‘Igot so agitated while I was listening to it that I got a blister on my morning walk.’

Professor Sir Michael Marmot is reflecting on an interview former chancellor George Osborne gave recently, where he described the UK as ‘the envy’ of the rich countries of the world prior to Brexit.

It was a defence of their records in government that Mr Osborne and former prime minister David Cameron also doubled down on in their evidence to the COVID inquiry. In what might seem like an entirely alternative universe to

many doctors, they described a country which had been well prepared for the pandemic, thanks to their rigorous programme of austerity.

Sir Michael is eviscerating in response. ‘Austerity killed the UK,’ he says. ‘If you look at the changes the chancellor made to the tax and benefit system after 2010, working families with children in the bottom 10 per cent of household income, their incomes would have gone down by 20 per cent. And for families in the second poorest decile, their income would have gone down by 12 per cent. It was clearly regressive – these were just

simply regressive policies making it harder for poor people to make ends meet.’

Sir Michael says that by 2019 government spending went down from 42 per cent of GDP to 35 per cent, and local government spending per person went down by 17 per cent in the least deprived 20 per cent of areas and 32 per cent in the most deprived.

‘Why would you imagine that wouldn’t have a negative effect? Do you think that all public money was going to waste, and you could cut with impunity?’

The result? Public services were in a ‘sorry place’,

‘Austerity killed the UK... these were regressive policies making it harder for poor people to make ends meet’

12 the doctor | August 2023

INSTITUTE OF HEALTH EQUITY

MARMOT: Regressive spending cuts have harmed society

regressive cuts to local government meant authorities’ ability to support communities was deeply limited and, perhaps most damningly of all, child poverty increased. Sir Michael echoes the confusion of a whole profession when trying to find ‘the envy of the world’ or a well-prepared country among the inequitable ruins of society in the UK.

Taking heed

It is now 13 years since Sir Michael’s landmark strategic review of health inequalities in the UK, Fair Society, Healthy Lives , which called for urgent action to address health inequalities in the UK.

The recommendations were to give every child the best start in life, enable all children, young people and adults to maximise their capabilities and have control over their lives, create fair employment and good work for all, ensure a healthy standard of living for all, create and develop healthy and sustainable places and communities and strengthen the role and effect of ill-health prevention.

The report was followed by a 10-year update in 2020 which revealed that, for the first time in more than 100 years, life expectancy had failed to increase across the country and, later that year, another report examining the relationship between COVID-19 and health inequalities – urging UK politicians to rebuild the country more fairly.

In the 13 years since Fair Society, Healthy Lives, there have been great successes for Sir Michael’s campaigning including cities, regions and local authorities declaring

bma.org.uk/thedoctor

themselves as basing their work around the Marmot principles.

In recent days and weeks Sir Michael has been invited to put together a report looking at health inequalities in Mexico and will look to work with the national institute of public health in italy on a plan to create a network of modern, healthy, cities.

He continues to work with the Welsh and Scottish Governments, too. ‘The fact is the arguments I’ve been making are being taken up all over the place,’ he says.

‘I don’t feel like I’m being ignored – I’m being listened to.’

There is, however, one glaring exception – the Westminster Government. Sir Michael says he ‘could spend all my time being unhappy because the Government in Westminster isn’t listening’ but is resolved to work with anyone who wants to in his bid to improve lives across the country and the world.

Best start in life

With a general election required by January 2025 a change in government may lie ahead.

So, what is Sir Michael’s prescription for the country’s

health should politicians be listening?

He says: ‘First we make sure we give every child the best start in life – that includes reducing child poverty, investing in pre-school, restoring closed Sure Start centres and addressing having among the least affordable childcare in Europe. Second, education and lifelong learning. Third, employment and working conditions. Fourth, everyone should have at least the minimum income necessary for healthy life. Fifth, healthy and sustainable places in which to live and work. And six, taking a social determinants approach to prevention. So yes, we would look at obesity and smoking and drinking but we also look at the social determinants.’

Those principles remain true to the original asks set out 13 years ago, but Sir Michael has also added two more for the ministers of 2023. He says: ‘We need to tackle discrimination, racism and their outcomes. And, finally we must tackle the climate agenda and the inequality agenda together.

‘That’s my prescription for the next government – that’s what I’d like them to do.’

‘We would look at obesity, smoking and drinking but we also look at the social determinants’

the doctor | August 2023 13

GETTY

BENEFITS LOST: Restoring closed Sure Start centres is one of Prof Marmot’s proposals

LESSONS FROM A FRAGILE LIFE

In the last issue, doctors told us how close encounters with their own mortality had changed their attitudes to life and work. It’s a subject into which deafblind medical student Alexandra Adams has a huge amount of insight, owing to a range of complex medical conditions. She says patients who have been through ICU need more support

14 thedoctor | August 2023

My first, and perhaps worst, near-death experience was when I was in a coma in Italy in 2018. My parents were essentially told I would ‘return home in a box’. I was in ICU for three weeks with respiratory failure, pneumonia and sepsis, and I suffered awful delirium; I still get flashbacks.

When I consider how many times I’ve been so close to the brink, I am reminded life is precious and I am incredibly fortunate to still be able to do most of the things I love. My mantra is: we need to embrace life as much as we can, regardless of our past, the what-ifs and our circumstances. After a traumatic event, you appreciate life so much more, such as the emotional connections you have with people, or daylight and fresh air. You will remember the smallest act of kindness, like a hand-hold, for a lifetime. I’ve also found that it has helped me let go of the things that don’t matter, like the drifting of relationships or materialistic stuff.

I will admit I sometimes feel I have been dealt a very unfair hand in life but I also see that my health crises have given me a unique insight into patients’ experiences that not many other healthcare professionals have. When you are a patient, on the other side of the bed, you become an outer shell of yourself, fragile, vulnerable, frustrated and powerless. I deem that insight my most precious gift, something which I am very grateful for and empowered by.

But empathy can make things harder too – especially when I come across another patient who is going through the system without the necessary support networks or with inconsistent care, which have been my experience. It only makes me more frustrated and upset, for them and for myself. But it’s also a reminder why I’m training to be a doctor.

And, as for anyone who has had a traumatic experience, it still catches you when you least expect it. I had to go back to ICU (as a medical student) last term, to see a patient, and I found myself experiencing flashbacks, completely out of the blue.

Focus on support

My own experiences have also reaffirmed to me that, as an NHS, we really lack in providing sufficient mental health support for patients. It can take people years to come to terms with a traumatic or life-changing event or illness.

Soon after my ICU stay in Italy, I was on a

ward round when I met a patient who had just come out of ICU and was feeling distressed and traumatised. I was able to comfort and reassure her, and signpost her to a local ICU patient support group who had helped me. I’ve developed a passion and ‘calling’ to help support and improve care for other patients who’ve gone through similar experiences to mine, post-ICU.

I don’t yet have all the answers to what’s going on with my health, and I still don’t have a team that will take responsibility for me, so the future can feel quite uncertain. I’ve been very lucky to ‘bounce back’ from all these blips before, but we’ve realised it’s a progressive thing and ‘bouncing back’ might not always happen, which hits home quite a bit. I choose not to wallow or let it weigh on my mind, but I think my parents worry.

Passing on Dying

is the one thing that we all have in common and it’s important to break down the taboos around it. Currently, we receive so little teaching on dying/end of life in medical school, and I fear that, with so much focus on saving lives, we will become completely ignorant to the fact that sometimes dying a good and dignified death is far better than extending and advancing life.

I am interested in specialising in palliative care one day because it is so patient-centred, holistic and strongly focused on helping patients to conserve their dignity, take control, and lead by their wishes and goals.

It also remains one of those specialties where, excuse the irony, I can best use my eyes and ears, as a deafblind person, to understand and support the patient perspective.

the doctor | August 2023 15

bma.org.uk/thedoctor

‘As for anyone who has had a traumatic experience, it still catches you when you least expect it’

‘I choose not to wallow or let it weigh on my mind, but I think my parents worry’

ADAMS

:

We need to embrace life as much as we can

FAIRNESS FOR ALL

By

Since the inception of the NHS, doctors trained overseas (commonly called IMGs [international medical graduates]) have been recognised as an integral part of the workforce. They make up approximately a fifth of all licensed doctors in the UK.

Better pay and conditions will not be won unless UK-qualified doctors and IMGs stand together.

Migrants have a long and successful history in the British trade union movement alongside British workers, from historic dock and factory disputes to now, such as in the Unite logistics disputes.

There is a similar and opposite history of governments, employers and others attempting to divide workers by race and nationality. The latest government attempt to pit workers against each other with its decision to fund its sub-inflationary pay offer to public sector staff through punitively increasing the immigration health surcharge (the fee paid by international

workers to access NHS services) and increasing visa costs is just one such example.

Beneficial effects

Without solidarity, workers will be divided and cannot organise successfully. One of the ‘wins’ predicted by supporters of Brexit was that it would reduce immigration in the agricultural sector, meaning there would be more and better paying jobs for British-born workers in farming. But despite this, pay hasn’t improved and conditions for workers in the sector, particularly migrant workers, remain brutal.

Migrants in general are good for the economy and society – there is lots of evidence that migrants are a net positive for economic growth and productivity.

There are more than 8,500 medical secondary care vacancies in England alone, even with the contributions of our current international colleagues, and these vacancies are having a huge impact on doctors. The

16 the doctor | August 2023

‘The problem with pay and conditions of doctors in the UK is not IMGs – it is the Government’s refusal to invest in the workforce’

The UK needs international medical graduates, and it needs them – and all doctors – to receive fair pay, conditions, and training opportunities.

ESSENTIAL: International medical graduates are integral to the UK workforce GETTY

Emma Runswick

majority of us work well beyond our rostered hours (70% of doctors in 2022 report working over and above their hours, up from 59% in 2021) and more than one in five doctors (22%) took a leave of absence due to stress in the last year. There is plenty of demand for our work, and not enough supply.

Labour demand and supply are not the driving factors in the exploitation of farming, social care or medical workers. Like medicine, both farming and social care serve crucial needs, they are labour intensive, and they are understaffed. Wages and working conditions in these sectors are currently far more influenced by the relationship between workers and employers, and the relative power they have. Like medicine, both sectors are also heavily influenced by government policies and subsidies. The number of UK-trained doctors in training has continued to slowly increase following the addition of all doctors to the shortage occupation list in March 2021, despite competition ratios increasing and the growing number of IMGs joining the workforce. Competition ratios have of course skyrocketed. Despite this, IMGs acquire training jobs at a lower rate than their UK-trained colleagues.

Artificial competition

The real source of the problem, however, is that despite increasing numbers of medical school graduates, and growing need in our population, the number of training posts has insufficiently increased. Now a workforce plan has been published, but it has no specific targets for postgraduate medical training places, which unless rectified will exacerbate the issues.

This has created artificially high levels of competition amongst colleagues, causing some to target each other rather than the government responsible. The problem with pay and conditions of doctors in the UK is not IMGs – it is the Government’s refusal to invest in the workforce. Many other countries offer better pay and conditions than the UK. We are currently haemorrhaging UK-qualified doctors to other countries, where they can earn more: one in seven UK-qualified doctors are currently practising abroad.

There have been suggestions that international medical colleagues, who are already vulnerable to visa restrictions and culture shock, should be prevented from direct entry to nationally recognised terms and

bma.org.uk/thedoctor

conditions and training roles to preserve access for the UK-trained. Creating a cohort of doctors who must endure locally employed (exploited) service to progress in the NHS is not to the benefit of those doctors, doctors in training or our patients.

In the choice between solidarity with colleagues and the threat of deportation, solidarity will not always win. This would create conditions of fear around whistleblowing and around challenging unfair treatment, including in situations shared by doctors in training. It would weaken doctors in pay disputes. Dividing doctors by calling for restrictions on visas and immigration, by punitively increasing fees for migrant workers, or by placing additional barriers to access nationally agreed terms and conditions, is unhelpful and will make it harder to fight and win together. Doctors are vital to society and there aren’t enough of them – in the UK or elsewhere.

All doctors should be paid fairly and have access to professional development. If the NHS wants to be an attractive place for doctors to work, it needs to pay better wages for all doctors working in the UK, regardless of where they qualify. This will only happen if doctors stand and fight together.

Emma Runswick is BMA council deputy chair

From September, the BMA will offer New to the UK – Free BMA membership, a special introductory rate for IMGs. For more information visit: bma.org.uk/join

RUNSWICK: All doctors should be paid fairly and have access to professional development

‘Creating a cohort of doctors who must endure locally employed (exploited) service to progress in the NHS is not to the benefit of those doctors, doctors in training or our patients’

the doctor | August 2023 17

Gladys McGarey saw Gandhi when she was nine, Afghanistan when she was 86, and at 102 has no plans for retirement. She tells Seren Boyd what drives her

‘NOT DONE YET’

One of the benefits of living to the age of 102 is perspective.

American GP Gladys McGarey lived through the Great Depression and the Second World War broke out just as she started medical school. She has survived cancer twice.

She has learnt to accept change and tough times with grace and courage. When her husband of 46 years asked for a divorce, she bought a new number plate for her car:

‘BE GLAD’.

One of the most striking things about Dr McGarey is her strong sense of purpose. It’s the answer she gives to questions about her longevity following the recent publication of

her book, The Well-Lived Life . (She also aims for 3,800 steps a day and regularly tours her garden in Scottsdale, Arizona, on her tricycle.)

Put simply, she loves helping people. That’s fundamentally why she’s still offering phone consultations, although she no longer has a licence to practise.

‘If I’d be doing something and I quit, my dad would look at me with his big black eyes and say, “Are you a quitter?” I’d say, “No, no, no, no.”

‘I have this inner drive that says, “You have a mission here. You have work to do. And you’re not done yet.” So, I’m 102. Next year, I’ll be 103, I guess. And we’ll see where it goes.’

‘My dad would say, “Are you a quitter?”

I’d say, “No, no, no, no”’

The man in the white cloth Dr McGarey’s family is full of medics. Her parents were osteopaths and missionaries serving in the Himalayan foothills of India, where Dr McGarey spent the first 15 years of her life. They treated everyone but prioritised the marginalised and ‘untouchables’.

Another strong influence on her desire to help people was a chance encounter with history when she was nine. Out of her train window, she saw a procession led by a ‘small man in a white cloth’. People started pouring out of the windows and running along the roof, shouting, ‘Gandhiji!’ It was 1930 and Gandhi’s Salt March protesting against the hefty taxes the

18 the doctor | August 2023

British levied on salt.

But not everyone wanted Dr McGarey’s help. She enrolled in an all-female medical school in Philadelphia in 1939, at a time when few accepted women. ‘We were told we had to be tougher and meaner than the men. We started with 50 students and graduated with 25.’

She was the first female intern to work at Deaconess Hospital in Ohio, and the ‘head resident’ took an instant dislike to her. While the male doctors were given a room to sleep in, she had to make do with the X-ray table. She was pregnant and suffering from morning sickness.

Dr McGarey didn’t realise till later that Lucille, the night cleaner, would secretly change the rota on the chalkboard, shifting Dr McGarey’s early shifts to later ones.

bma.org.uk/thedoctor

Always determined, always different, Dr McGarey soon made her mark once she’d qualified as a GP. A mother of six herself, she became a strong advocate of natural home births, at a time in the 1970s when labour was heavily medicalised.

‘When I was in medical school, we totally anaesthetised the mother. But we shouldn’t “deliver” babies: we deliver pizzas and speeches. Women birth babies. We have taken away the essence of who women are in relationship to the whole life process, including medicine.’

Her embrace of more holistic approaches led her and her husband Bill to cofound the American Holistic Medical Association in 1978. Today, some of her views about the mind-body relationship remain radical. Yet, other beliefs, including

her focus on nutrition and social connection as determinants of health, have become increasingly mainstream.

‘Back then, talking about the inner aspects of our being was woo-hoo. We were called all kinds of names. Things are changing but it isn’t there yet.’

A living force

Dr McGarey shows no bitterness when she says that the years since her divorce have been her best. When her husband left her, she left the clinic in Phoenix where they were business partners, and she set up in practice with her daughter, GP Helene Wechsler, in nearby Scottsdale.

Now a great-greatgrandmother, she still cuts a distinctive figure with her crown of white braids: she’s not cut her hair since her 40s.

And she still has a 10-year plan, which does not include retirement. At 86, she visited Afghanistan to support her brother’s project improving health outcomes for women giving birth in rural areas. She has continued to visit and work in India.

Dr McGarey still loves medicine because she still loves people.

‘I don’t see medicine as a war against disease and pain. I see it as a way in which we as physicians can be in touch with the living force within another human being and create a connection. You help because you care about that person. Love is the great healer.’

The Well-Lived Life, published by Penguin Michael Joseph, is out now

the doctor | August 2023 19

‘You help because you care about that person’

‘YOU HAVE WORK TO DO’: Dr McGarey through the decades

‘BE KIND, DO GOOD’

Doctors have paid tribute to Anthea Mowat, the hugely respected and admired former chair of the BMA representative body, who has died at the age of 64.

Dr Mowat will be remembered for her dedicated work in promoting equality and inclusivity, addressing the gender pay gap and championing her fellow staff, associate specialist and specialty doctors.

Her husband Andrew says his wife’s passing has left an enormous hole in his and his family’s lives, adding that they had been enormously touched by the extent of tributes and condolences expressed in person and online.

Paying thanks to the vital support Anthea and her family received from Morpeth district nurses and Macmillan carers during the final weeks of her life, Dr Mowat says he hopes his wife will be remembered for the values that informed and guided her career and life, namely to ‘be kind, be true, be inclusive, do good’.

Dr Mowat says: ‘People who knew her well, and those whose familiarity was less, have highlighted her kindness, her smile, her generosity and inclusion of others, and particularly her ability to get things done collectively, with agreement and

goodwill all round.’

BMA representative body chair Latifa Patel says Dr Mowat’s passing is a huge loss for medicine, adding that the contributions made during her career will leave a lasting legacy for future generations of doctors.

She says: ‘Anthea broke many glass ceilings and left behind open doors, so it was easier for others to follow. Her absolute dedication to equality and representing the groups that are too often forgotten in medicine was always evident.

‘She fought hard for SAS doctors, for flexible workers and for women in particular so the path was easier. We are indebted to her. I have no doubt that her legacy will live on in all those who she helped, supported, and lifted up as well as those who benefitted from her work without realising.’

Doctors’ advocate

Born in Gosforth, Newcastle, Anthea Mowat studied medicine at the University of Aberdeen where she first met Andrew, with the two marrying in 1984 and raising two daughters, Siobhan and Catriona.

After qualifying, Anthea chose to specialise in anaesthesia ultimately becoming an associate specialist in anaesthesia and chronic pain at United

20 the doctor | August 2023

‘Her legacy will live on in all those she helped, supported and lifted up’

Anthea Mowat broke many glass ceilings, and encouraged others to do the same. Tim Tonkin hears tributes to a doctor remembered for her decency and commitment to equality

DEARLY MISSED: Tributes flood in from family and friends of Dr Mowat

Lincolnshire Hospitals NHS Trust in 1993.

During the 25 years she worked at the trust, Dr Mowat took on a number of roles and responsibilities including serving as chair to her trust’s local negotiating committee for a seven-year period. She also mentored her SAS colleagues as a clinical tutor and was the lead appraiser at her trust.

It was in 2002 that Dr Mowat became a member of what is now the specialist, associate specialist and specialty doctors UK committee. Her work on SASC saw Dr Mowat become more deeply involved in the BMA, serving as the association’s deputy RB chair, and then RB chair, between 2013 and 2019.

A staunch advocate for gender equality in medicine, Dr Mowat helped to inspire many other women doctors to increase participation in the BMA.

Ujjwala Anand Mohite, the current and first ever female chair of SASC UK, remembers well the kind and supportive mentoring she received when working with Dr Mowat.

She says: ‘When I first came to SASC there were not many other women; Anthea really looked after me. She was very supportive of women and very inspiring. I still remember when I was on the agenda committee and she was RB chair, every time the SAS section came up she would encourage me to join her on the stage as deputy chair.

‘She was always welcoming, and she made me believe nothing was impossible.’

Tackling bullying

A recipient of the BMA’s association medal, an award given for members demonstrating outstanding achievement and commitment, Dr Mowat eventually stepped down from her role as RB chair in 2019.

Reflecting on the achievements made alongside her colleagues during her BMA career, Dr Mowat expressed particular pride for her work on improving equality and inclusion and leading on the association’s anti-bullying and harassment project.

Retiring from medicine in 2019, Dr Mowat returned to frontline work following the outbreak of COVID-19 during which she trained and served as a medical examiner throughout the pandemic until standing down again in 2021.

Dr Mowat was honorary secretary of the Medical Women’s Federation and since October last year had served as the World Medical Association chair of WMA associate members.

She also chaired the Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland’s SAS

bma.org.uk/thedoctor

committee, receiving the association’s Pask Certificate of Honour, a commendation given to those who have ‘demonstrated exceptional bravery in the performance of their clinical duties’ in 2009, and the AAGBI’s Anniversary medal in 2018.

Outside of her career, Anthea enjoyed singing in the church choir and socialising with her old school friends. She was also an avid fan of murder-mystery TV and literature, with Agatha Christie being one of her favourite authors.

News of Dr Mowat’s death prompted tributes and condolences from many corners of the medical profession.

In an online post, former Royal College of Physicians president Dame Jane Dacre described Dr Mowat as ‘a superb contributor to the gender pay gap review’ and someone who had ‘made a huge impact on the lives of specialty doctors’.

Diversity champion

Consultant radiologist, BMA council, consultants committee and equality, diversity and inclusion advisory group member Anil Jain meanwhile paid tribute to his former colleague saying: ‘I had opportunity to work closely with Anthea at BMA committees, ARM and [on the] bullying and harassment project. She will be remembered and missed.’

Paying tribute to his late colleague, BMA council chair Philip Banfield describes Dr Mowat as ‘a dedicated representative for – and servant to – her fellow doctors’, and someone who would ‘never be forgotten’.

He says: ‘Anthea was unusually kind and welcoming in the medico-political world that she has helped to change the face of. She cared deeply about equalities and representation, taking on a leading role in the BMA’s equality, diversity and inclusion work and was passionate about the vital role women doctors contribute to the NHS.

‘She was instrumental in speaking up for SAS doctors – themselves a traditionally underrepresented group – and negotiated on behalf of them locally and later nationally in various roles in SASC.

‘Her commitment to the profession was matched in her care for patients and dedication to the NHS during her long career, during which time she taught doctors on a variety of topics for the benefit of the future workforce.’

He adds: ‘Anthea’s death is an enormous loss to the medical profession and to those she inspired to “have a go”. She will be sorely missed, but never forgotten.’

the doctor | August 2023 21

‘She was always welcoming, and made me believe nothing was impossible’

MOHITE: ‘Anthea looked after me’

A FAIR DEAL

Vytenis Andriukaitis has led a remarkable life: born in a Soviet gulag in 1951 to becoming a co-author of the Independence Act of Lithuania in 1990. He has been a practising cardiovascular surgeon and a senior member of the European Commission and World Health Organisation. Peter Blackburn speaks to a man of many talents for whom social justice means everything

‘Iremember it was a terrible time when he delivered his speech… I was so attacked… I saw this guy who spoke about issues which were far from reality. He sent to people his lies and of course it was painful to see. I was deeply touched by such lies.’

Vytenis Andriukaitis has achieved extraordinary amounts through his various careers in domestic politics, the international arena and medicine. But he has rarely had more coverage in the press than when – following a now infamous speech by archBrexiteer Nigel Farage in the European Parliament, in which he accused MEPs of ‘never having a real job in their lives’ –he was pictured desolate, head in hands, despairing.

It was a moment which united many pro-Europeans

in the UK and across Europe in horror – but Farage’s speeches, which often likened the EU to the Soviet Union, were particularly triggering for Dr Andriukaitis, who had dedicated so much of his life to fighting authoritarianism and had been arrested on several occasions in his younger years for his role in anti-Soviet movements. For Dr Andriukaitis the European project was the absolute antithesis of – the antidote to – the sort of authoritarianism that affected his early life and saw his parents deported from Lithuania to a Siberian gulag.

‘It was painful,’ he says, reflecting on Mr Farage’s speech. ‘Absolutely stupid.’ Brexit, and the extrication of Britain from the EU, both politically and in the general sense of distance it created,

felt like personal tragedies for Dr Andriukaitis. He feared back then it would be a ‘disaster’ for the UK and hurtful for the EU and none of the events since 2016 have changed his view, particularly when it comes to health and healthcare.

Dr Andriukaitis describes access to healthcare, health systems, food safety, safety standards, research and investment, fighting rare diseases and public health as ‘sensitive areas’ which need cooperation across the continent.

‘It was clear it would be so difficult for all of us and you would see a lot of difficult questions related to practical implementation of your separation, and still now you see some very difficult consequences in areas of people’s health and disease

22 the doctor | August 2023

‘We need to find ways to build new bridges between the UK and the EU’

ANDRIUKAITIS: Dedicated to fighting authoritarianism

ANNIKA HAAS

the doctor

and access to treatment and investment. We are facing those challenges now.’

Social justice

In particular, Dr Andriukaitis cites shortages of medicines and healthcare staff as reasons for greater collaboration, and in recent days and weeks the UK’s scientific community has urged access to the EU’s Horizon programme for scientific collaboration and discovery.

Collaboration, ever closer union, railing against nationalism – these are not just buzzwords or slogans for Dr Andriukaitis. They mean everything. That sense of togetherness and a motivation for social justice are his key principles. ‘Social justice was, and still is, the main goal which inspires me to serve people,’ he says. ‘Today we see big problems with social justice, in my country, in the EU and globally also.’

Social justice is not only Dr Andriukaitis’ inspiration in politics but was also the driving force for his study of medicine. When he was at school, Lithuanian doctors were key national leaders and figures and ‘had a strong influence in our Lithuanian national movement’.

He says: ‘They made a lot of steps in defending social justice, proposing

broad concepts like social guarantees, social security and healthcare security. Those ideas – to be a medical doctor and to serve people were very close to my heart. I tried to connect my understanding about how to treat people… with their health… and to be prepared to help them in their difficult circumstances.’

Dr Andriukaitis, who is also passionate about history and holds a degree in the field from Vilnius University, specialised in cardiovascular surgery for more than 20 years before moving into politics.

His political achievements have been vast. He is coauthor and a signatory of the Independence Act of Lithuania of March 1990 and one of the co-authors of the Constitution of the Republic of Lithuania adopted in 1992. Dr Andriukaitis was one of the founders of the Lithuanian Social Democratic Party and later chairman of the party. He was a member of the Lithuanian Parliament for six terms and served as minister for health, and chaired the committee on European affairs, including during the accession to the EU in 2004, as a member of the foreign affairs committee, and as a deputy speaker of the Parliament. He has also been European commissioner for health and food safety and now special

The Doctor BMA House, Tavistock Square, London, WC1H 9JP. Tel: (020) 7387 4499

Email thedoctor@bma.org.uk Call a BMA adviser 0300 123 1233

@TheDrMagazine

@theBMA

The Doctor is published by the British Medical Association. The views expressed in it are not necessarily those of the BMA. It is available on subscription at £170 (UK) or £235 (non-UK) a year from the subscriptions department. All rights reserved. Except as permitted under current legislation, no part of this work may be photocopied, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the editor. Printed by William Gibbons. A copy may be obtained from the publishers on written request.

The Doctor is a supplement of The BMJ. Vol: 382 issue no: 8395 ISSN 2631-6412

envoy of the WHO for universal health coverage.

Britain’s future

It has been a life extraordinarily well lived – a list of achievements few can match. But Dr Andriukaitis is focused only on the future and continuing to fight for those principles of social justice. He also hopes that the story of Britain’s role in the EU is not yet over. ‘I am an optimist, generally,’ he says. ‘Of course, I am 72 years old, not a young man, but in every difficult situation I have always stayed as an optimist.

‘We need to unite our forces… We need to find ways to build new bridges between the UK and the EU. I truly believe that the UK will join the EU once again. Of course it needs to take time.’

He adds: ‘My profession as a cardiac surgeon was a very difficult one but we stayed always in a positive mood. We tried to find ways to be constructive, to be progressive, to see what can inspire and how we can inspire people to be positive and to seek positivity.’

Perhaps Dr Andriukaitis’ biggest focus is on campaigning for universal healthcare across the world.

He says: ‘Health is one of the biggest human rights. Health for all.’

Editor: Neil Hallows (020) 7383 6321

Chief sub-editor: Chris Patterson

Senior staff writer: Peter Blackburn (020) 7874 7398

Staff writers: Tim Tonkin (020) 7383 6753 and Ben Ireland (020) 7383 6066

Scotland correspondent: Jennifer Trueland

Feature writer: Seren Boyd

Senior production editor: Lisa Bott-Hansson

Design: BMA creative services

Cover: Getty

Read more from The Doctor online at bma.org.uk/thedoctor

‘In every diffi cult situation I have always stayed an optimist’

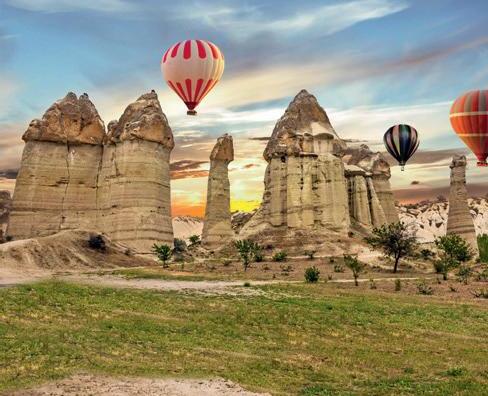

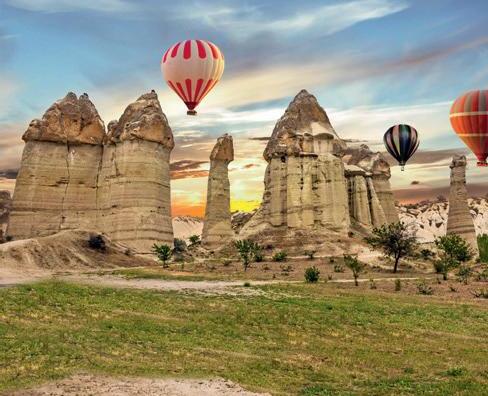

Including a spectacular range of excursions:

Days 1 – 7: 5-star cultural tour of Cappadocia

• Cappadocia (World Heritage): enchanting landscape, with unique natural phenomena, buildings and bizarre tufa formations

• Konya: visit the Monastery of the Whirling Dervishes whose dance has been declared an Intangible Heritage of Humanity (admission included)

Package includes:

(Price when booking the following separately)1

Return flights with a reputable airline2 £2501 to and from Antalya, incl. hotel transfers

7-day 5-star cultural tour of £5651

Cappadocia

Including Monks Valley (World Heritage)

Including Karpuzkaldiran Waterfall Including Konya Including + FREE 8 days of relaxation in an 5-star luxury hotel Including

Sensational rate for you as a reader of THE DOCTOR from only

• Göreme (World Heritage): open-air museum, which includes numerous monastery complexes, wall paintings and a cave church, a highlight of any trip to Cappadocia (admission included)

• Çavuşin: impressive village where you can enjoy typical green tea

• Monks Valley (World Herçitage): fairytale rock formations and changing colours promise unforgettable moments, together with Göreme a World Heritage

• Arts and crafts in traditional carpet factory

• Sinasos: idyllic village with ancient Greek mansions

• Valley of Love: romantic walk through the uniquely shaped tufa formations in the Valley of Love

• Underground cities: more than 100 cities have been dug out of mountains here. You will explore the secrets of one of the many mysterious underground cities of Cappadocia (admission included)

• Craftsman tradition in a jewellery and leather factory

• Historic Silk Road: numerous medieval caravanserais line this world-famous route

• Antalya: city tour through the capital of the Mediterranean region with Mediterranean flair

• Karpuzkaldiran Waterfall: imposing waterfall which thunders into the open sea on the coast

Day 8 – 15: FREE extended holiday in an exclusive 5-star luxury hotel

Spend the next 8 days relaxing on the Turkish Riviera in your 5-star luxury hotel! The comfortable rooms are luxurious and modern. Unwind in the hotel‘s fantastic spa with sauna or stroll along the beach.

- 7 nights in a double room in selected 4- and 5-star hotels (national category)

- 7× tasty breakfast

- Round trip in our modern and air-conditioned travel coach

- Spectacular range of excursions + admissions (as per itinerary)

OUR GIFT: FREE 8 days of relaxation £3851 in a 5-star luxury hotel

- 7 nights in a double room in an exclusive 5-star luxury hotel in the Turkish Riviera (national category)

- Attractive outdoor pool, heated indoor pool, private beach and wonderful spa area, including sauna

Qualified, English-speaking cultural tour guide

Combined price per person £1,2001

£565 £385 £1,200 Göreme (World Heritage)

Price difference per person – £1,0001

£1,2001

British citizens do not need a visa to enter Türkiye for stays of up to 90 days. Passports must be valid for a minimum period of six months from the date of entry into Türkiye and there should be a full blank page for the entry and exit stamps. Nationals of other countries are advised to enquire at the Turkish Embassy about the entry requirements applicable to them.

* The statutory bed tax is already included in the price. A deposit of 20% of the tour price is payable upon receipt of written booking confirmation. The remaining amount must be paid 80 days before departure. The price applies on 27 February 2024 for flights from Birmingham. For other travel periods, seasonal price increases apply as listed in the flight schedule. The trip only applies to the recipient and accompanying adults. The travel conditions and privacy policy of RSD Travel Limited apply. These can be requested from the travel hotline or viewed at www.rsd-travel.co.uk. The passenger can terminate the contract at any time before the package tour begins in exchange for payment of a commensurate withdrawal fee. For more information, please see the T&Cs of RSD Travel Limited. Note: minimum number of participants 15 people for each travel date. Cancellation no later than 20 days before the start of the trip, if this is not achieved. Planned group size approx. 30 people. Not suitable for people with reduced mobility. Subject to misprints and changes. The photos show typical examples of what you can expect from our hotels. Gift only applies when booking the cultural tour.

# Holiday price increase p.p.: £49.

Your advantage code! DOC111183

021 1267 now, absolutely free, to secure your preferred travel dates.

0800

The hotline is open Monday – Friday from 9 a.m. to 6 p.m. Tour operator: RSD Travel Ltd., 2nd Floor Suite, Cuttlemill Farmhouse, Cuttlemill Business Park, Watling Street, Towcester NN12 6LF, United Kingdom Registered No. 07507940 (England & Wales) Call

1 The combined price of individual components if booked separately was calculated on 27 June 2023 the travel dates 27 February 2024 to 12 March 2024. Flight from Birmingham to Antalya and Antalya to Birmingham on www.turkishairlines.com (cheapest, cancellable available flight including luggage), transfers airport – hotel – airport on www.suntransfers.com. Holiday Inn Antalya –Lara, Akra Hotel, Dervish Cave House on www.booking.com, coach tour on www.nbktouristic.com, excursions on www.viator.com. The comparative price for the gourmet package is based on the standard prices of our Turkish partner (www.nbktouristic.com). Between the date of the price comparison and the date of travel, these prices may go up as well as down.

2 e.g. SunExpress

3 Feedback provided by customers of RSD Travel Ltd and RSD Reise Service Deutschland GmbH, a European group of companies travelling in 2021/22.

All the flights and flight-inclusive holidays in this brochure are financially protected by the ATOL scheme. When you pay you will be supplied with an ATOL Certificate. Please ask for it and check to ensure that everything you booked (flights, hotels and other services) is listed on it. Please see our booking conditions for further information or for more information about financial protection and the ATOL Certificate go to: www.caa.co.uk

ADVERTISEMENT For you as a reader of THE DOCTOR One of the UK’s most popular cultural tours !3 – Including a spectacular range of excursions & admissions ! 15-day 5-star tour Cappadocia Combined price £ 1,2001 Price difference – £ 1,0001 only £ 200* p. p. from Days 1 – 7: 5-star cultural tour of Cappadocia Days 8 – 15: Relaxation in an exclusive 5-star luxury hotel ! FREE! Your saving per person -

per person

of

£200*

£1,0001

instead

Your rate per person from only £200* example hotel

Optional services at attractive conditions: Gourmet package: The package includes a delicious buffet every evening with international specialities during the 7-day cultural tour: only £129 per person instead of £ 1 Single room surcharge: £200 per person (subject to availability) Cappadocia (World Heritage) Including Airports Birmingham London Gatwick Manchester Airport fees p. p. £0 £35 £35 Days of Depature Tue Tue | Wed | Thu Tue | Wed | Thu

£149 Flight Dates Sept. 2023 (19 – 28.9) Oct.2023 (3 – 12.10) Oct. 2023 (17 – 19.10) Oct. 2023 (24 – 26.10) Oct. 2023 (31.10) Nov. 2023 (2 – 7.11) Febr. 2024 (21 – 28.2) March 2024 (6 – 31.3) March 2024 (19 – 27.3)# April 2024 (3 – 10.4)# April 2024 (17 – 24.4) Seasonal price increase p. p. £200 £150 £100 £50 £0 £0 £0 £60 £120 £180 £240 111183_TheDoctor_UK_Kappa_190x260_ANZ.indd 1 20.07.23 16:13

Our travel tip