5 minute read

It’s all about Hydrogen – Part One

The shift to Net Zero Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions globally over the next few decades will see a shift away from fossil fuelspredominantly petroleum derived diesel in construction machines. Alex Woodrow, managing director, KGP Powertrain Intelligence talks all things Hydrogen for Construction Worx…

The shift will require low carbon fuels, including electricity, hydrogen and other liquid and gaseous fuels to meet the various broad demands of the sector. Hydrogen, most likely produced by electrolysis from renewable electricity, is likely to be a major contributor to this sector’s decarbonisation

Advertisement

Hydrogen has many detractors. The total lifecycle energy requirement of an electric machine is much lower than a diesel machine, or a hydrogen powered machine using either a fuel cell or a hydrogen fuelled combustion engine. However, there will be a need to timeshift and place-shift energy use, storing it when renewable electricity generation is high, for periods of high demand or when renewable generation is condition limited. If the amount of renewable electricity that is converted to hydrogen is abundant enough and can be stored, then overall efficiency may be less critical than the benefits of GHG reduction.

Looking at hydrogen investment globally its clear to see that many stakeholders are placing bets on hydrogen taking a share of future energy supply. The European Green Deal/RePower and US Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), are the tip of the iceberg of these investments - looking towards both reducing climate impact but also improving national energy security.

Even with the considerable worldwide investment in hydrogen production there will be competition for its use. Concerns persist over supply, cost and energy efficiency, but it is likely that a significant share will be used in construction equipment, as well as adjacent segments –mining, agriculture and material handling. But availability as well as cost will be a key factor.

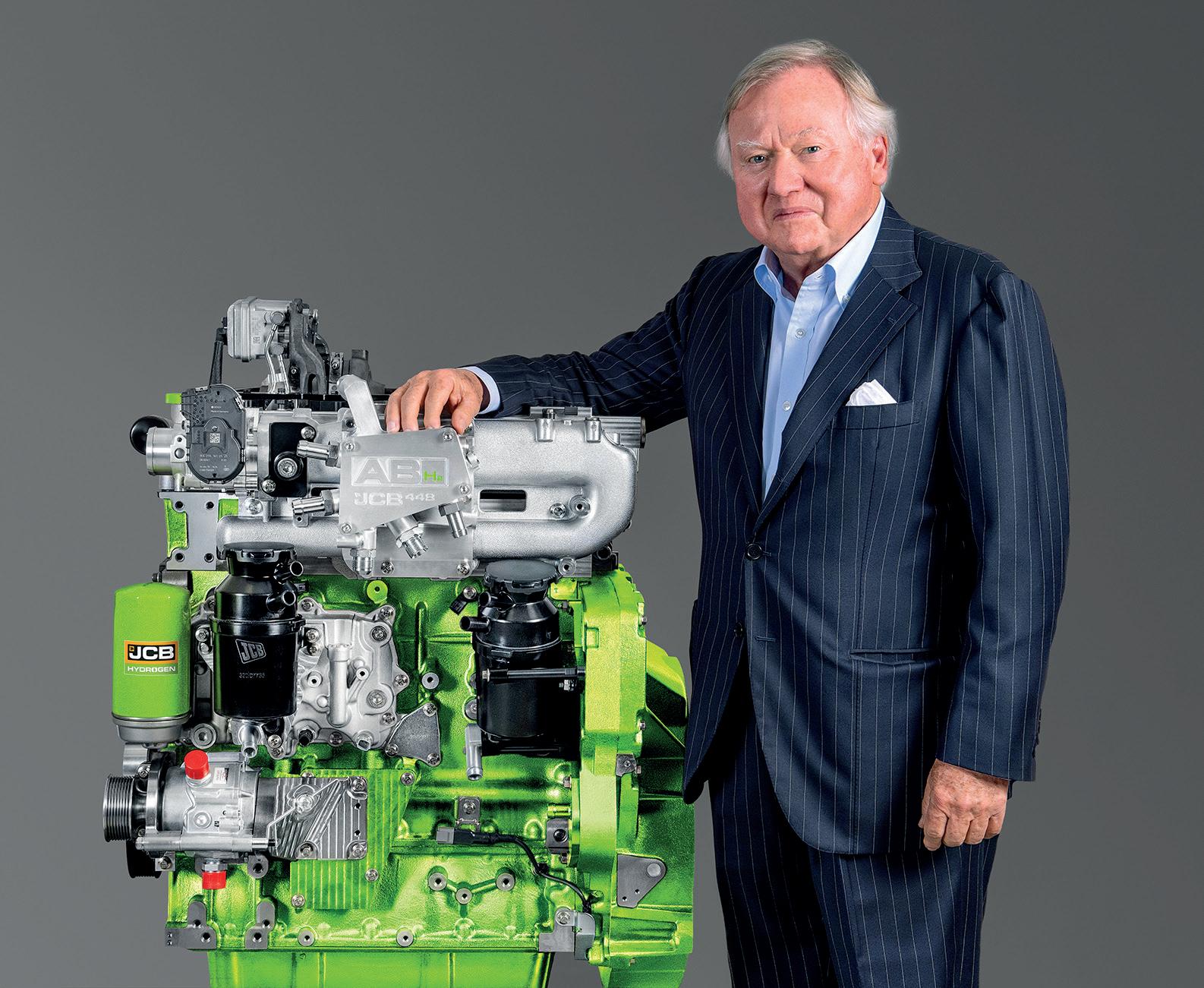

Lord Bamford and the JCB hydrogen engine

In 2021, the latest full year of statistics available, global demand was 94Mt according to the International Energy Agency’s 2022 Global Hydrogen Review. The vast majority is used in the refining and chemical industries. Less than 1Mt was low carbon hydrogen, with over 98% produced from fossil fuels. This hydrogen is known as ‘Grey’ hydrogen. ‘Green’ hydrogen will be produced from renewable electricity, ‘Blue’ from fossil fuels, combined with carbon capture and storage. Hydrogen produced from nuclear generation is ‘Pink’ or ‘Purple’.

Investment in green hydrogen, largely using ‘behind-the meter’ rather than grid electricity in scale should make the cost competitive in the future with that from fossil sources today, albeit not until close to 2050. At around $1-2.50 per kg now, in the future with solar it could be as low as $1 in 2050, up to $4 with on-shore wind.

With all the investment in hydrogen, key users will be prioritised for industrial processes, or injection into gas grids. However, as it scales around specific sites or regions (or hydrogen clusters, valleys or islands) surplus will be used in harder to electrify transport and industrial segments, including trucks and construction machinery.

Pipeline distribution of hydrogen will be feasible in some of these clusters, but initially transport will be on a tanker truck. With current technologies transport is relatively expensive, as compression allows 1t of hydrogen to be transported on a 40t truck/trailer combination.

For truck and construction application the choice of prime mover will be either fuel cell, or hydrogen combustion engines (H2-ICE). Fuel cells are being widely used in commercial vehicle applications and light vehicles - and being tested in other applications, but still remain immature. For heavy truck applications fuel cell modules from passenger cars are being tested. There is a trade-off between price and durability that will need to be overcome for truck and potential construction applications. A passenger car fuel cell system may require in the order of 5,000 hours durability, but 30,000 hours are being targeted for trucks. For non-road construction machinery the additional demands of the application, dust, vibration and G-forces from hammering, drilling, loading and ripping duties amplify durability concerns.

Technology and Decarbonisation Minister Jesse Norman pictured in Rocester, Staffordshire, today with a JCB backhoe loader powered by a hydrogen combustion engine

Fuel cell durability concerns mean that the hydrogen alternative, shifting diesel engines to hydrogen combustion is being widely explored. It is expected all major engine non-road engine manufacturers are working on the hydrogen engine. JCB in the UK is likely to be one of the first to market with its AB H2 4.8 litre engine, based on its existing 448 diesel model. Speaking at recent events, JCB has highlighted that it considers hydrogen combustion’s four major issues solved, 1) Hydrogen Mixing, 2) Air Compression, 3) Spark Ignition and 4) Steam Management. In the UK other investment in H2-ICE includes that at Cummins’ Darlington plant where an updated version of B6.7 will be designed as a fuel agnostic engine, with hydrogen as an option. Hydrogen combustion, using green hydrogen, produces much lower emissions that even the state of the art next generation diesels. Both CO2 is very low, as there is no carbon in the fuel, also lower particulates, although burning of a small amount of lubrication oil may cause some particulate matter to be produced. Under future EU legislation it is expected that a H2-ICE may be considered zero tailpipe carbon and noxious emissions. This view was reinforced in the EU’s recently updated truck and bus CO2 proposals, a view that remains to be agreed by the UK government.

Part Two will focus on H2 ICE’s outlook – look out for this in the next issue of Construction Worx, which will be the Plantworx 2023 special.

JCB has installed its super efficient hydrogen engine into a 7.5 tonne Mercedes truck