EXPAND YOUR MIND, REFINE YOUR WARDROBE

ZOOT SUITS

BENTLEY BOYS

PETER O’TOOLE

GAME OF THRONES

EXPAND YOUR MIND, REFINE YOUR WARDROBE

ZOOT SUITS

BENTLEY BOYS

PETER O’TOOLE

GAME OF THRONES

“SHOW A FEW FACIAL TICS AND THROW SOMEONE AROUND THE ROOM OR BLOW THEIR BRAINS OUT, AND PEOPLE THINK IT'S GOOD ACTING”

MAX RAABE

LESLIE PHILLIPS

“One’s personal portmanteau should be selected, both upon purchase and for each day’s tasks, with as much care and attention as one’s suit of clothes.”

Gustav Temple, CHAP Spring 22

Gustav Temple, CHAP Spring 22

Editor: Gustav Temple

Picture Editor: Theo Salter

Circulation Manager: Andy Perry

Art Director: Rachel Barker

Sub-Editor: Romilly Clark

Subscriptions Manager: Jen Rainnie

Contributing Editors: Chris Sullivan, Ed Needham

The editor of The Chap for the last 24 years is also the author of The Chap Manifesto, The Chap Almanac, Around the World in 80 Martinis (Fourth Estate), Cooking For Chaps and Drinking For Chaps (Kyle Books) and How To Be Chap (Gestalten). He is currently working on a book without ‘Chap’ in the title.

Chris Sullivan is The Chap’s Contributing Editor. He founded and ran Soho’s Wag Club for two decades and is a former GQ style editor who has written for Italian Vogue, The Times, Independent and The FT. He is now Associate Lecturer at Central St Martins School of Art on youth style cults. @cjp_sullivan

Ed Needham is the editor and publisher of Strong Words magazine, launched in 2018 to give book enthusiasts a fighting chance of keeping up with the blizzard of new titles, with reviews that don’t feel like homework. He was previously editor of FHM in its million-selling nineties heyday and managing editor of Rolling Stone in New York.

MARIE DE WINTER &

Our German correspondents are editors-in-chief of the German 1920s magazine Le Journal of the Bohème Sauvage. On their blog wintersturm.jimdofree.com, the ‘time-travelling journalists’ provide many articles in English about their diverse activities in the name of good (vintage) style.

David Evans is a former lawyer and teacher who founded popular sartorial blog Grey Fox Blog twelve years ago. The blog has become very widely read by chaps all over the world, who seek advice on dressing properly and retaining an eye for style when entering, whatever the age. @greyfoxstyle

ACTUARIUS

Olivier Woodes-Farquharson is an adventurer, diplomat, voice actor and writer, although not always in that order. When not travelling to obscure places that may or may not exist, he is most likely to be found at Cheltenham Races – the best place to blood his latest tweed – or furiously foraging in the English countryside.

A photographer and jazz singer inspired by all things vintage, especially the golden age of Hollywood, Noelle’s photographic work has been featured by the BBC and national press. Her sultry vocals have entertained establishments such as Ronnie Scott’s with swing band The Jive Aces. @noellevaughnphotography

Actuarius is an artist, essayist, photographer and journalist. A selfconfessed petrolhead, he mainly produces works based around his twin passions of Art Deco and mechanised transport, making the shortlist for the highly prestigious Guild of Motoring Writers Feature Writer of the Year in 2021.

Subscriptions 01442 820 580

Alf Alderson is an awardwinning adventure travel writer whose work appears regularly in the world’s leading newspapers, magazines and websites. He has also written and contributed to a wide variety of guidebooks on adventure travel, skiing, surfing, cycling, hiking, mountain biking and camping.

contact@webscribe.co.uk

John Minns has been a collector, buyer and seller of antiques and collectables from the age of nine, when he first immersed himself in the antique world by foraging London antique markets in the morning before school, then selling his finds to his eager school pals. His passion is still as strong today.

Email chap@thechap.co.uk

Website www.thechap.co.uk

Twitter @TheChapMag

Instagram @TheChapMag

Facebook/TheChapMagazine

ALF ANDERSON JOHN MINNS OLIVIER WOODESFARQUHARSON NOELLE VAUGHN FERDINAND STURM DAVID EVANS1 THOU SHALT ALWAYS WEAR TWEED. No other fabric says so defiantly: I am a man of panache, savoir-faire and devil-may-care, and I will not be served Continental lager beer under any circumstances.

2 THOU SHALT NEVER NOT SMOKE. Health and Safety “executives” and jobsworth medical practitioners keep trying to convince us that smoking is bad for the lungs/heart/skin/eyebrows, but we all know that smoking a bent apple billiard full of rich Cavendish tobacco raises one’s general sense of well-being to levels unimaginable by the aforementioned spoilsports.

3 THOU SHALT ALWAYS BE COURTEOUS TO THE LADIES. A gentleman is never truly seated on an omnibus or railway carriage: he is merely keeping the seat warm for when a lady might need it. Those who take offence at being offered a seat are not really Ladies.

4 THOU SHALT NEVER, EVER, WEAR PANTALOONS DE NIMES. When you have progressed beyond fondling girls in the back seats of cinemas, you can stop wearing jeans.

5 THOU SHALT ALWAYS DOFF ONE’S HAT. Alright, so you own a couple of trilbies. Good for you - but it’s hardly going to change the world. Once you start actually lifting them off your head when greeting passers-by, then the revolution will really begin.

6 THOU SHALT NEVER FASTEN THE LOWEST BUTTON ON THY WAISTCOAT. Look, we don’t make the rules, we simply try to keep them going. This one dates back to Edward VII, sufficient reason in itself to observe it.

7 THOU SHALT ALWAYS SPEAK PROPERLY. It’s really quite simple: instead of saying “Yo, wassup?”, say “How do you do?”

8 THOU SHALT NEVER WEAR PLIMSOLLS WHEN NOT DOING SPORT. Nor even when doing sport. Which you shouldn’t be doing anyway. Except cricket.

9 THOU SHALT ALWAYS WORSHIP AT THE TROUSER PRESS. At the end of each day, your trousers should be placed in one of Mr. Corby’s magical contraptions, and by the next morning your creases will be so sharp that they will start a riot on the high street.

10 THOU SHALT CULTIVATE INTERESTING FACIAL HAIR. By interesting we mean moustaches, or beards with a moustache attached.

8 AM I HOMBURG?

Readers submit photographs of themselves in their ‘Edens’

12 THE CORONATION: A CHAP’S GUIDE Torquil Arbuthnot shares the advice he has given to the palace on protocol and dress code at this summer’s royal beano

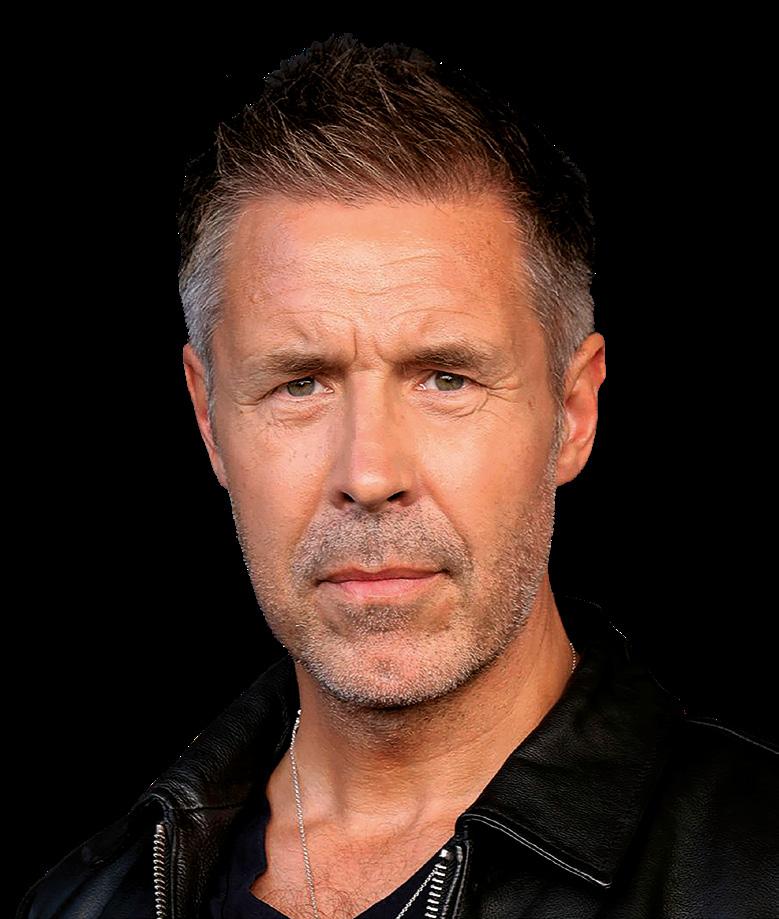

22 INTERVIEW: PADDY CONSIDINE

Chris Sullivan meets the affable man behind the iron mask in House of the Dragon

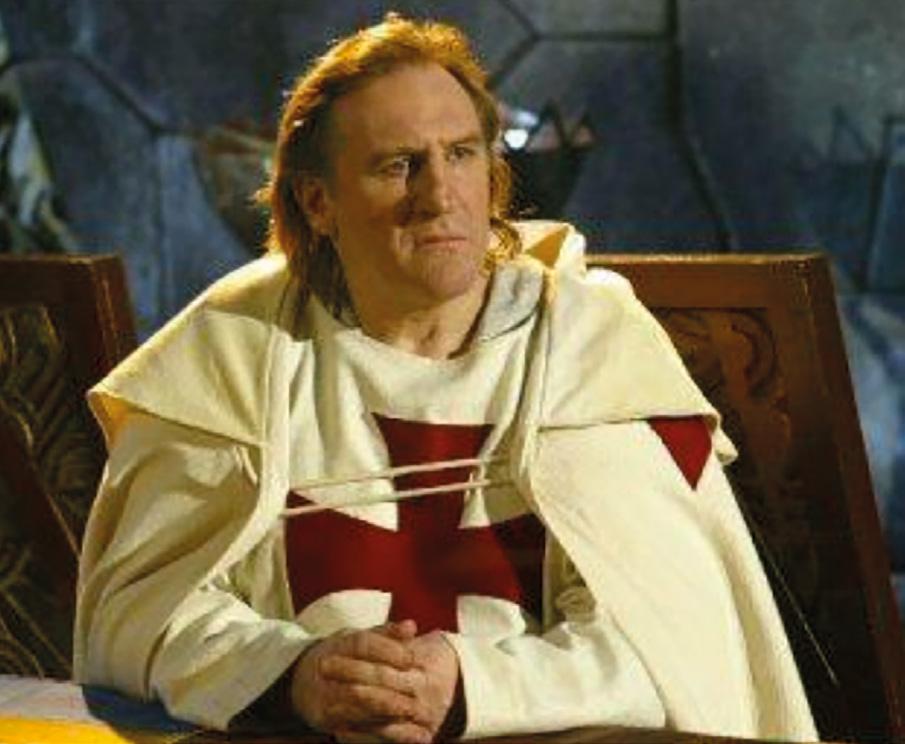

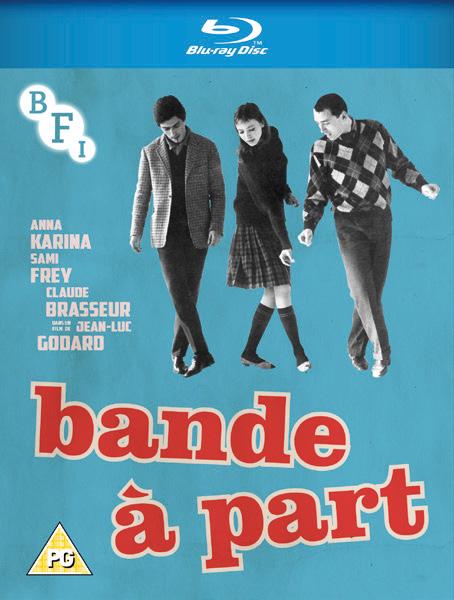

30 LES ROIS MAUDITS

The stories by Frenchman Maurice Druon that inspired George RR Martin’s historical epic Game of Thrones

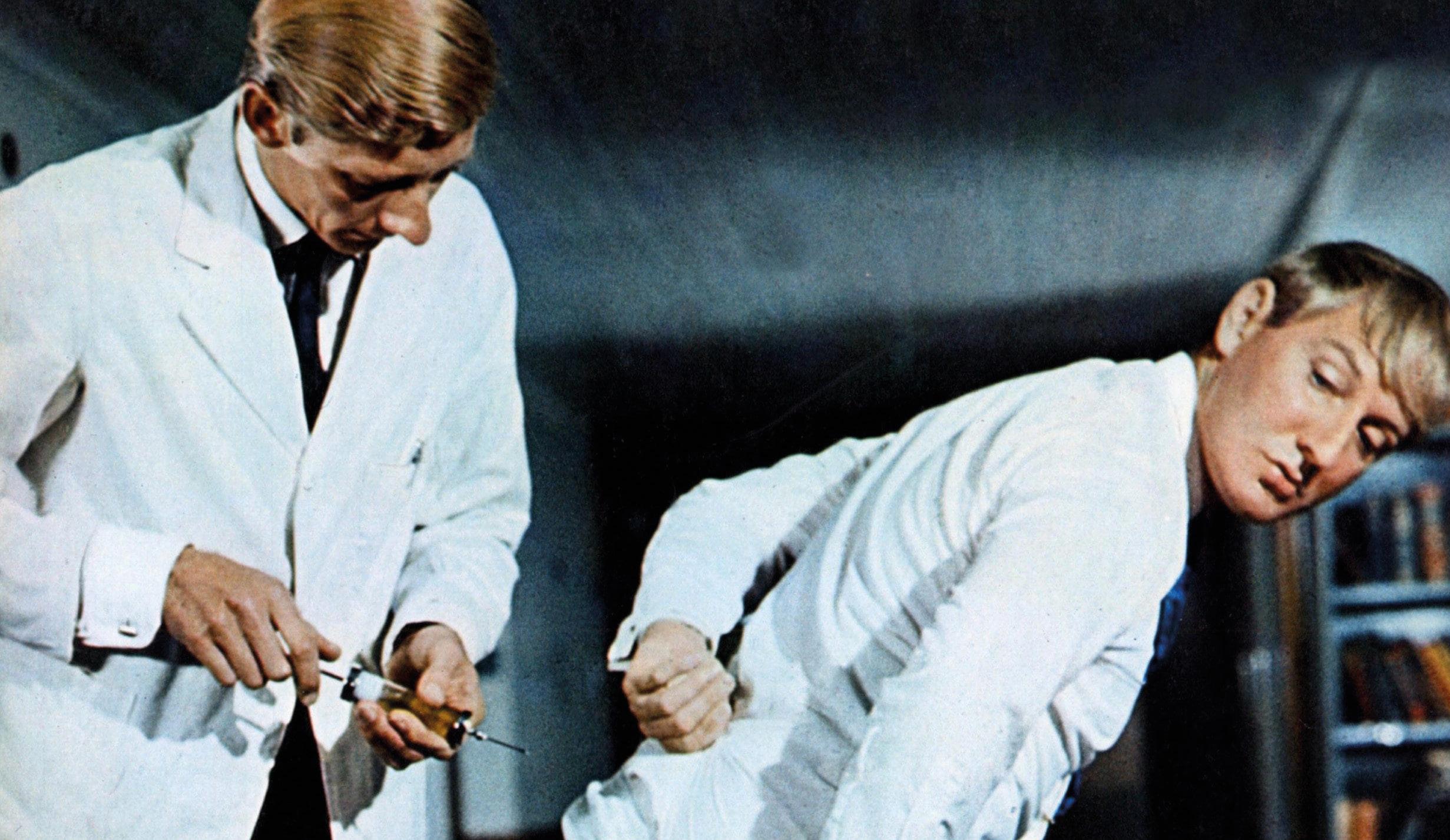

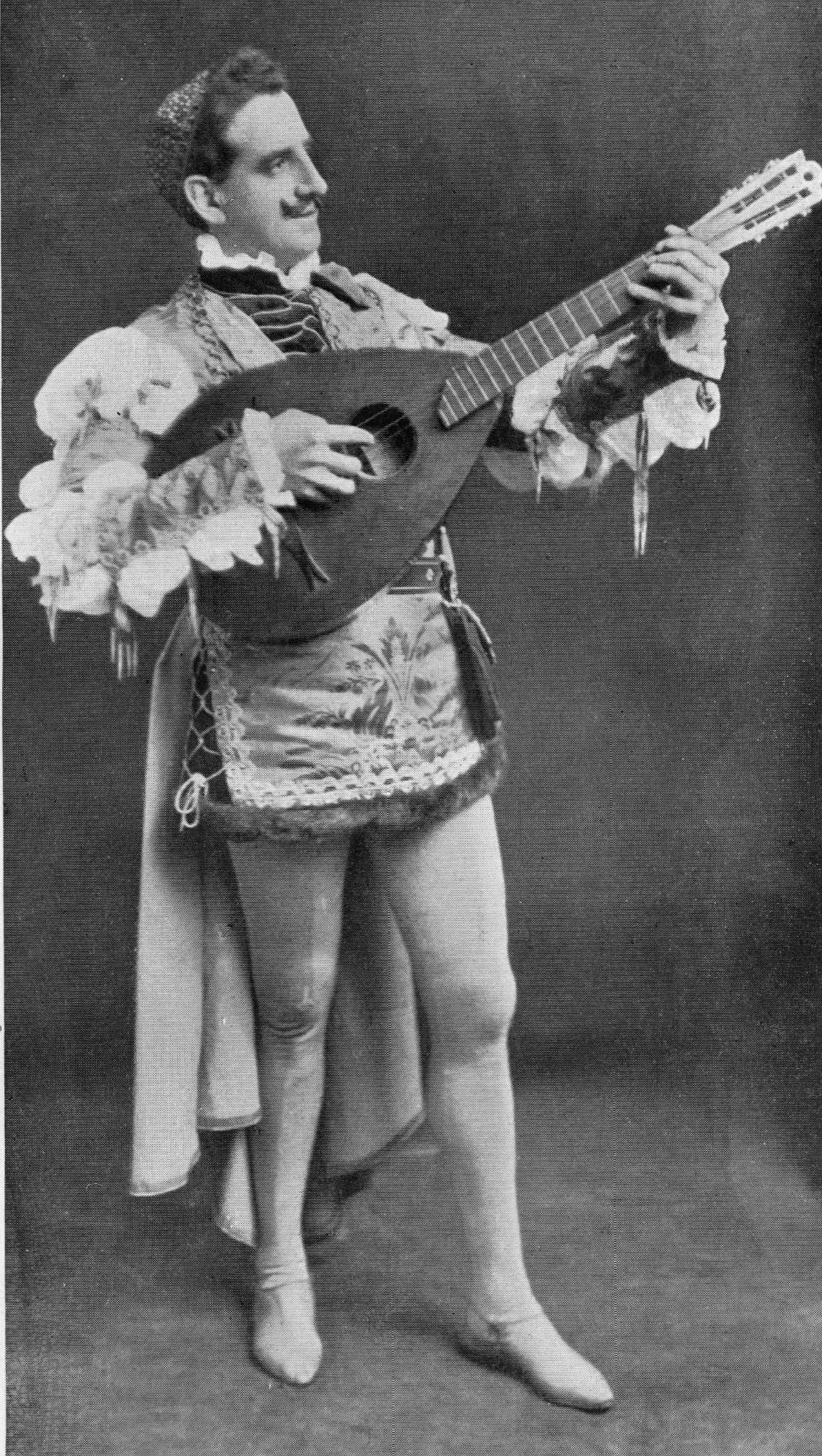

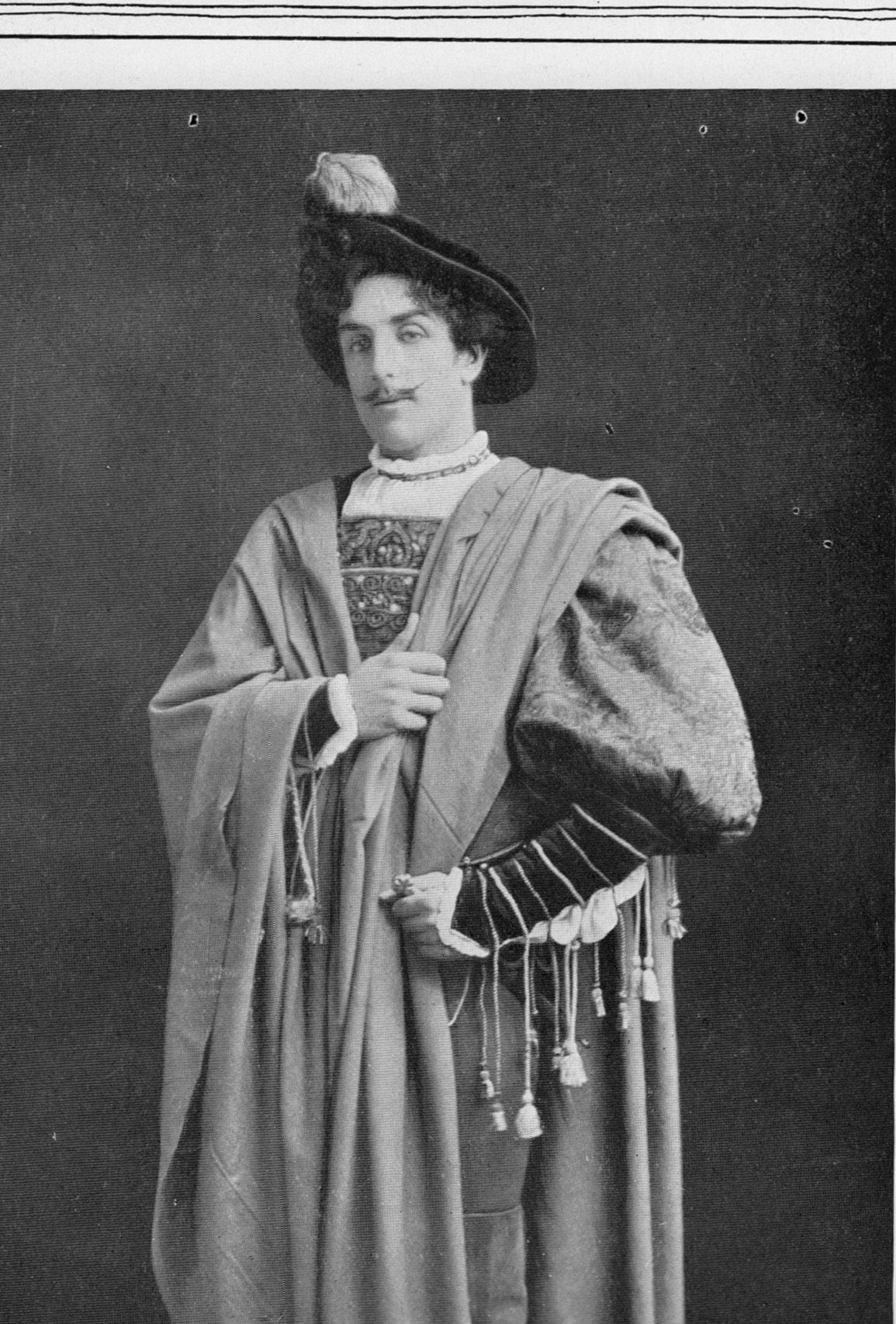

36 LESLIE PHILLIPS

Andrew Roberts’ tribute to the great actor, who departed this earth last year aged 98

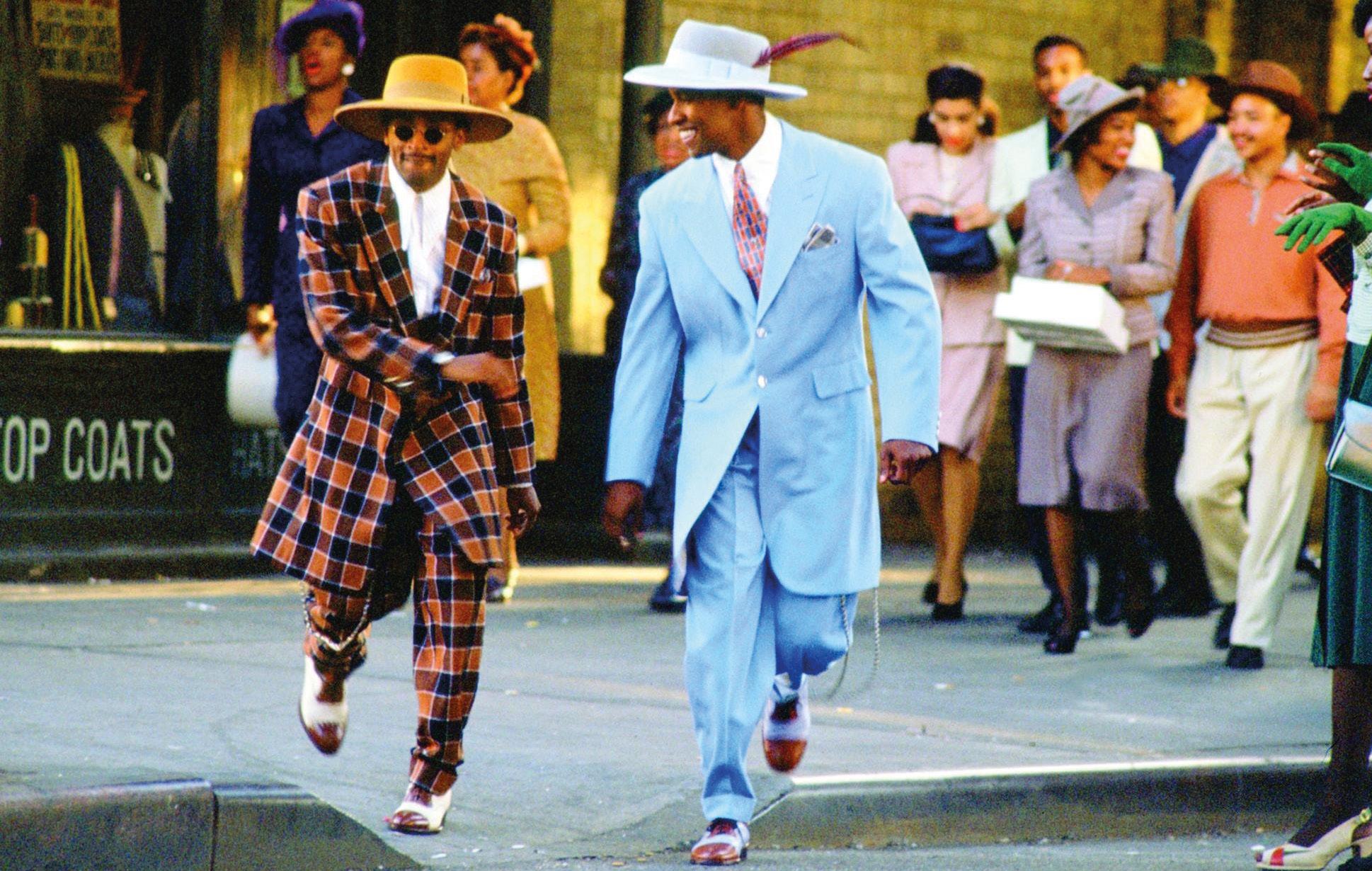

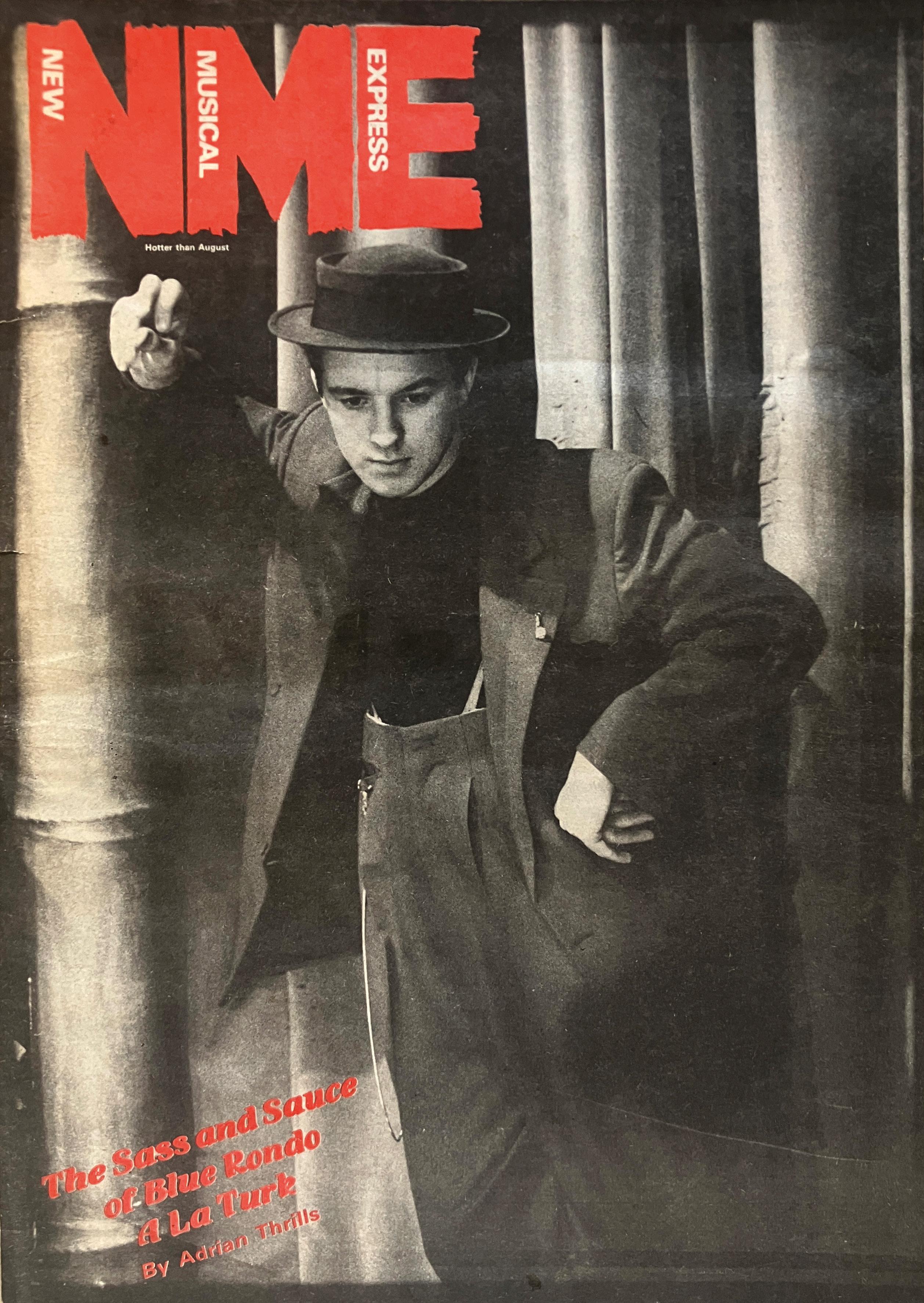

44 ZOOT SUITS

Chris Sullivan on the most inflammatory item of male clothing from the last century and why it caused riots in 1940s Los Angeles

54 LONDON BOY LOU

The sharp dressed man-about-town brings a splash of violent elegance to the streets of Whitechapel

66 GOOD HOMBURG

Gustav Temple follows the sartorial trail of the Homburg back to its roots in 19th century Prussia

70 GREY FOX COLUMN

David Evans admires the colourful eccentricity of David Hockney and searches for more colour in menswear

76 MAX RAABE

Our Teutonic correspondents meet the silky-voiced Berliner to discuss the state of vintage style in Germany

86 THRONE OF GAMES

Henry Cockburn advises Chaps in search of mediaeval splendour in Middle England

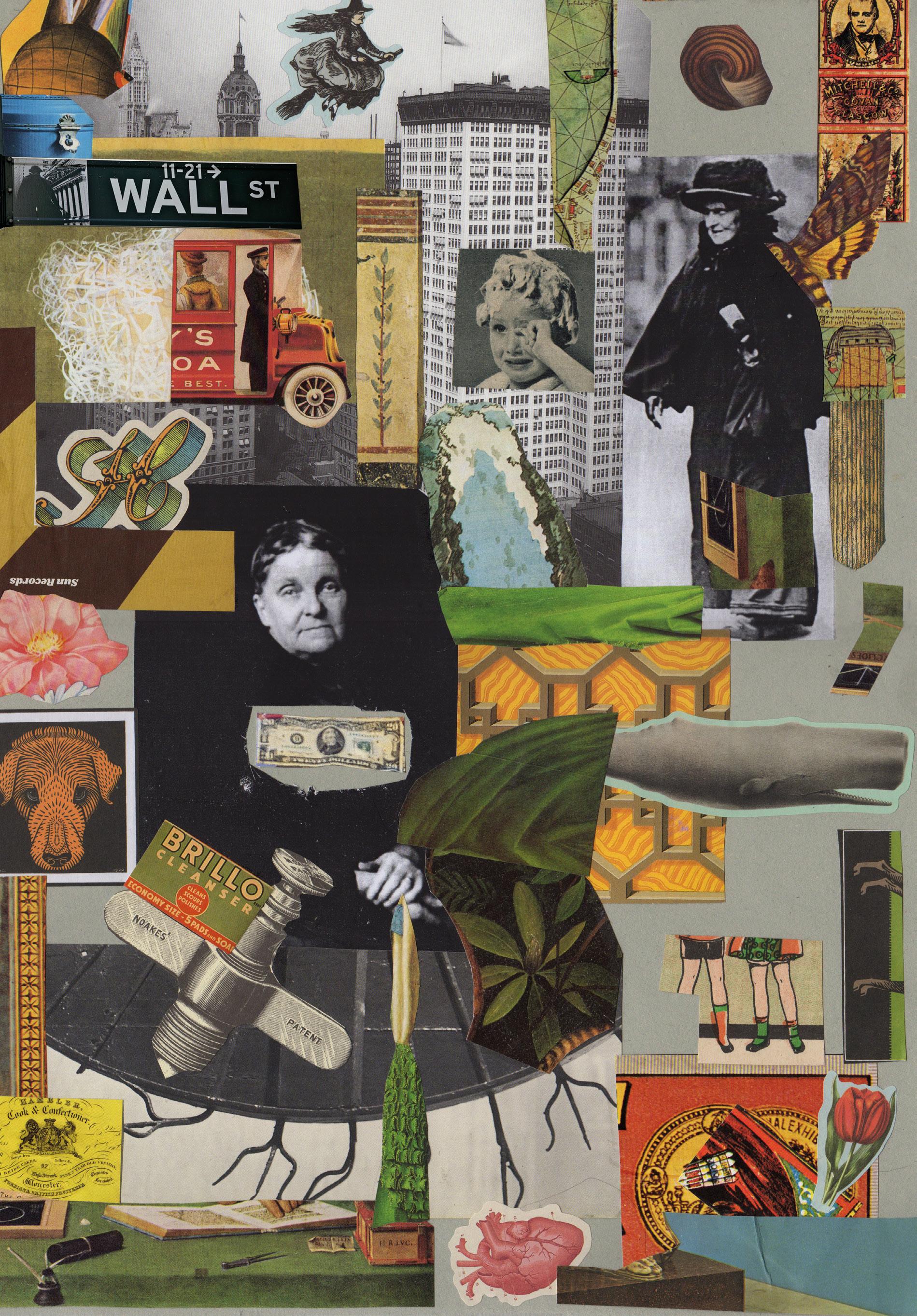

93 THE WITCH OF WALL STREET

Olivier Woodes-Farquharson on the dangerously parsimonious habits of Hetty Green

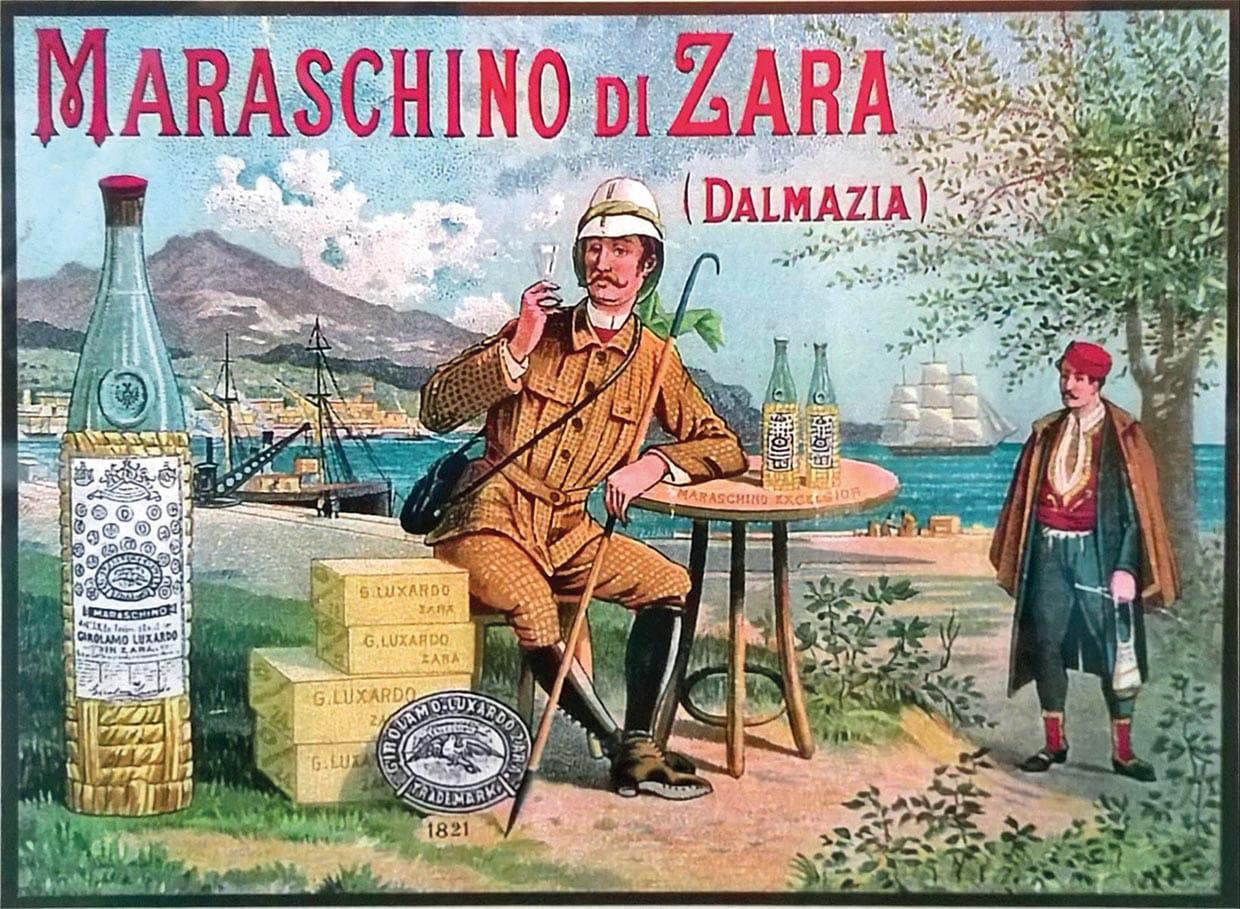

100 DRINK: MARASCHINO EXCELSIOR

Gustav Temple samples the cherrylicious range from Italian brand Luxardo

106 THE LANESBOROUGH GRILL

Alexander Larman and Gustav Temple dine in the shadow of Buckingham Palace

114 BENTLEY BOYS

Actuarius relives the glory days of Bentley by taking a spin in a recreated Bentley Blower

121 MAZDA MX-5

Alf Alderson road tests the affordable sports car that handles like a much pricier roadster

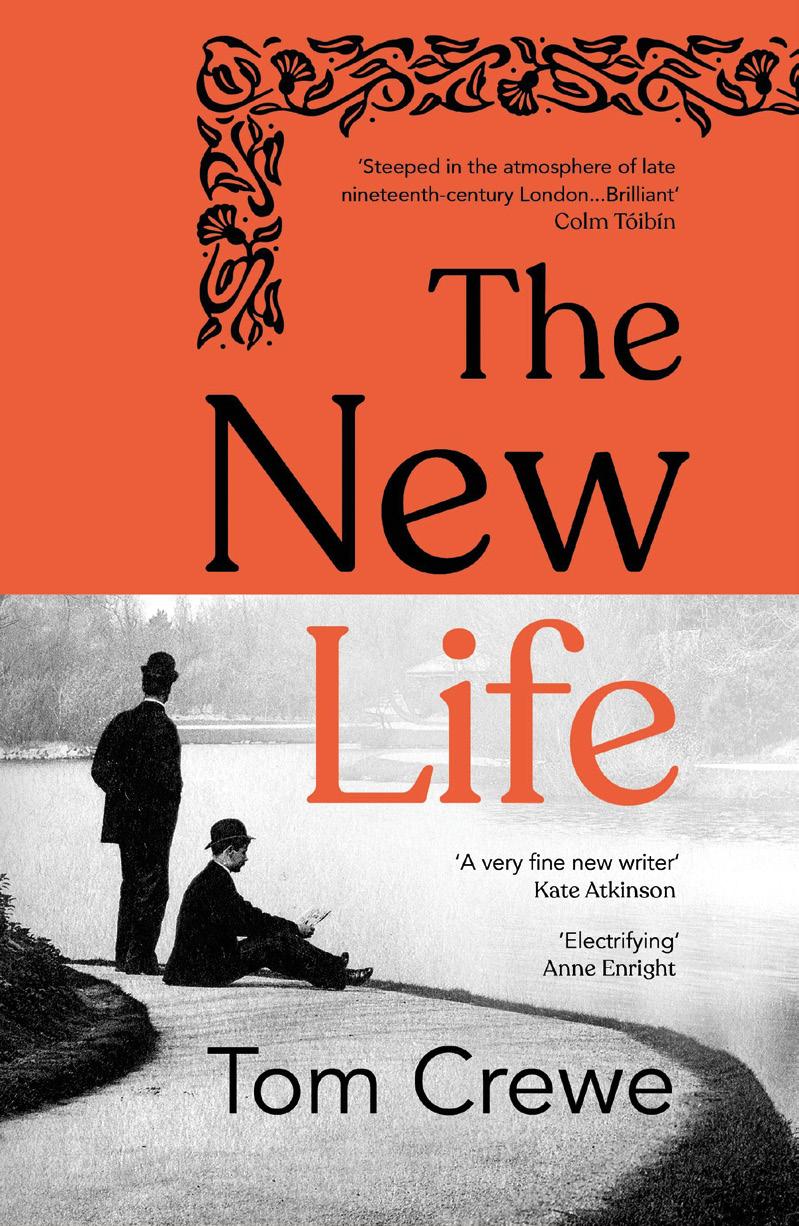

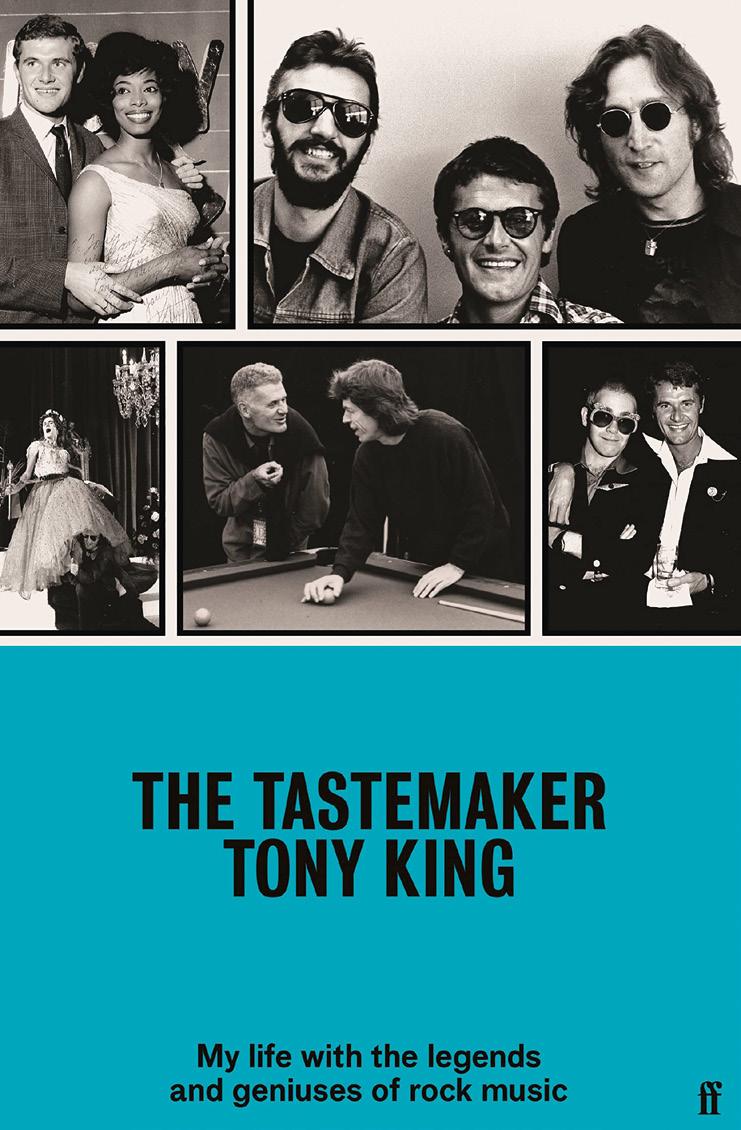

130 AUTHOR INTERVIEW

Ed Needham meets Tony King, publicist to such luminaries as Elton John, The Rolling Stones and The Beatles

136 BOOK REVIEWS

New books from priests, butlers, people hackers and men of letters

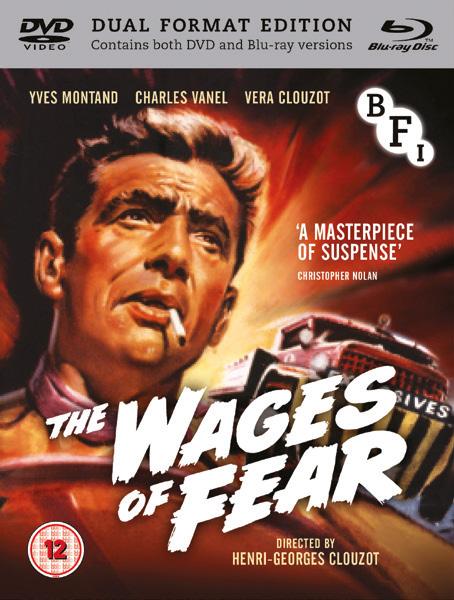

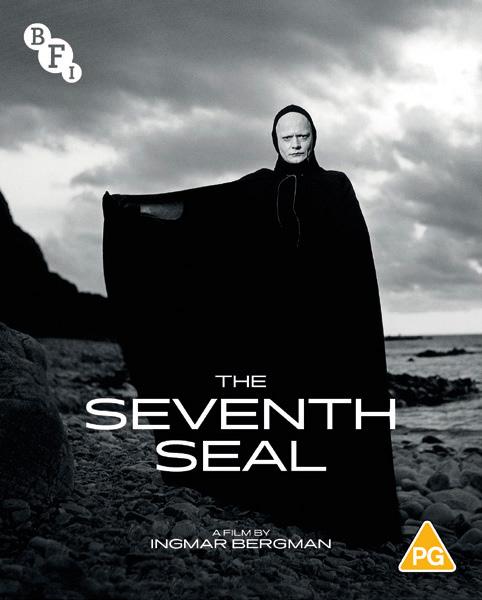

140 THE RULING CLASS

Stephen Arnell asks whether Peter Medak’s 1972 satire starring Peter O’Toole satire has finally come of age

148 THEATRE

Ruby Demure treads the haunted boards at the Theatre Royal, Brighton, in the footsteps of Marlene Dietrich, Lauren Bacall and Diana Dors

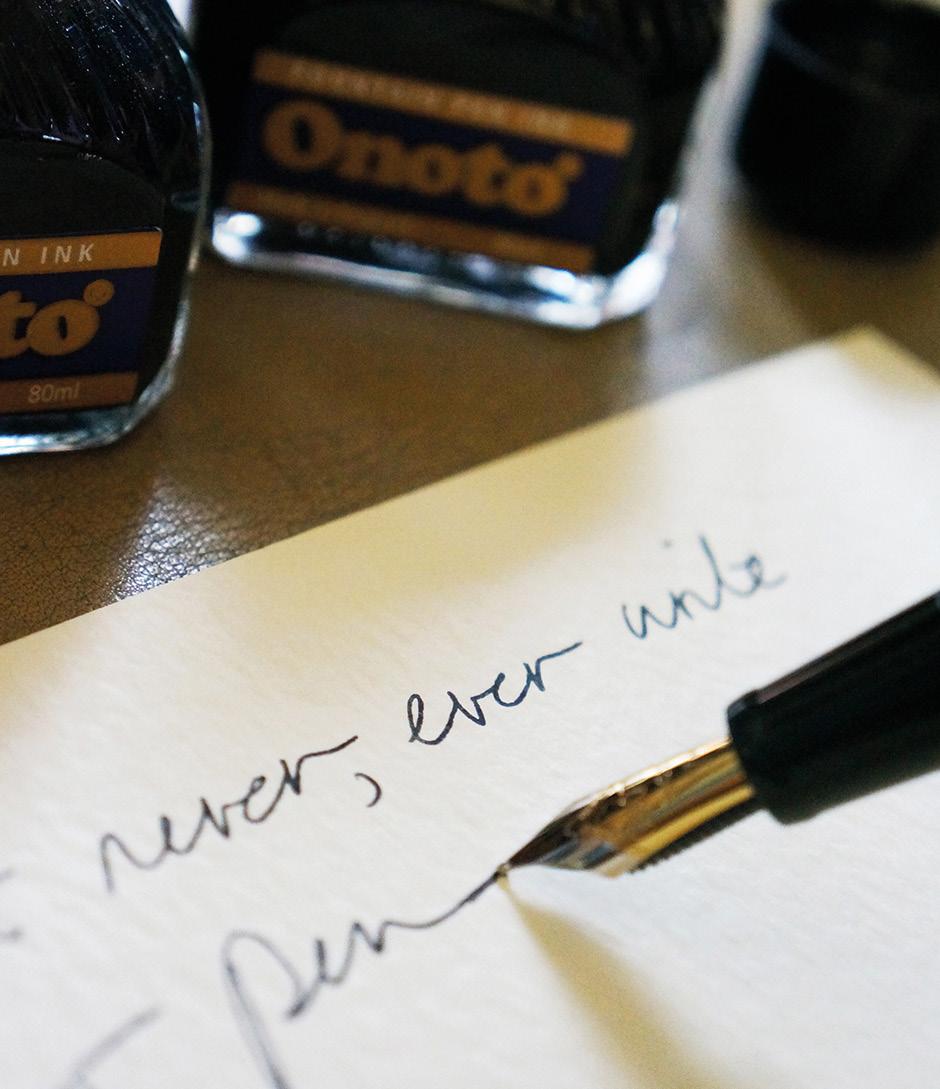

157 ANTIQUES

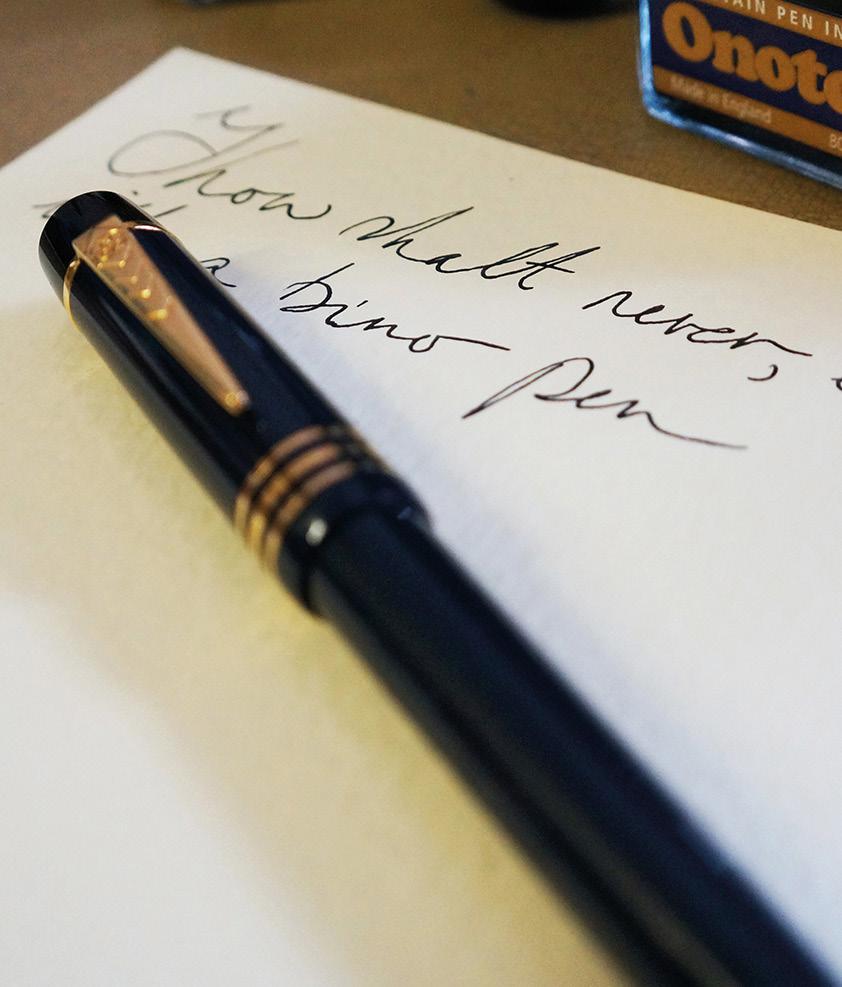

John Minns allows the ink to flow through his Waterman Taper In-Cap to provide a history of the fountain pen

162 CROSSWORD

WE REQUESTED PHOTOGRAPHS FROM READERS OF THEMSELVES IN THEIR HOMBURGS, AND THE RESPONSE WAS PRECEDENTED, FOR EVERY CHAP READER SHOULD OWN ONE OF THESE ELEGANT ITEMS OF HEADWEAR.

In the next edition, we shall be tackling the Straw Boater. Please send your photos to chap@thechap.co.uk

“I do not claim to have successfully got down with my Bad Homburg self,” writes Clive Collett, “nor that I Eden come close... I leave such judgements to your good selves.”

Sir, we have no hesitation in declaring you ‘Star Homburg’, due not only to the excellent quality and fit of your ‘Eden’, but also to the natty ensemble accessorising it. As such, we can overlook the terrible puns.

“I have on occasion been known to leave the Fedora or Bowler at home in favour of something more classy,” writes David Hodson. “Pleasant as it is to don one of the aforementioned hats, I believe the Homburg has a tad more panache about it, though sadly is not seen often enough.”

Quite so, sir. We should also compliment you on your pocket camera, which must allow you to take photographs of people without them even noticing.

“Please find attached a photograph of m’self,” writes Jonathan Ross, “wearing a Homburg with a recently acquired Inverness cape, standing outside Gallery 286 beside ‘The Conspirator’ by Gil Whyman.”

At first we were unsure whether this was in fact a Homburg, and whether it can indeed be worn with an Inverness Cape. An enquiry to the management of Lock & Co came back with the reply, ‘With a moustache like that, anything is permitted.’

Where would this publication be without Paul Lawford? Most likely in some flamenco tap room in Andalucia, with hopefully something higher in alcohol content than Señor Lawford’s bathwater, though this is unlikely to exist.

“A photograph is attached of myself donning a Homburg on Bloom’s Day,” writes The Penguin Chap, “hence the reading material of Joyce’s Ulysses.”

Sir, your ability to read the works of James Joyce in reverse is rather impressive, and we are only glad you didn’t decide to wear your excellent Homburg backwards as well.

Ian Taylor, like the Penguin Chap (previous page) also has the ability to read books backwards, but sadly no skills with a razor, whether forwards or backwards.

“In response to your most recent cri de chapeau,” writes Stephen Myhill, “I attach an image for your consideration. I trust it may be looked upon kindly, following the disappointment of failing to make the fez muster.”

Sir, how could we possibly resist such a plaintive cry, especially from the rather melancholyfaced love child of John Waters and Robert Crumb?

Mark Wolff put on his finest outfit and stood outside a gift shop hoping for employment, but all he got was a man in a Homburg asking to have his picture taken with him, which didn’t pay very well.

Whereas Sean Lacey has gone beyond melancholy, which is not surprising for the love child of Lytton Strachey and HP Lovecraft.

Despite Rick Evan’s (sic) alarmingly typing his name with an apostrophe, we were relieved that, at last, one of our submissions made the sine qua non reference to Edward VII, supposedly the inventor of the Homburg (see page 66). Congratulation’s (sic), sir.

“A photograph of myself wearing a ‘chapeau diplomate’ with my spouse in Belgium,” writes Dominiek Dendooven, from Belgium.

Sir, your steely gaze, obviously fake spectacles and glamorous accomplice suggest you are on the wrong side of le corps diplomatique. We shall get Tintin on the case immediately.

“I’d like to submit a couple of photos,” writes Andrew Parsons, “of my vintage mid-century Eden from Germany (a Homburg from Hamburg, no less!)”

Another shady customer clearly up to no good in a gentlemen’s convenience, having probably stashed a secret microfilm in the cistern. The Homburg clearly doubles as the choice of headwear for secret agents.

“I am sporting a prewar black Homburg with moss green band by Lock & Co,” writes Dominic Carey, “paired with 1930s kid leather gloves in cream and a green silk scarf.”

If only utility bills were anything like they were pre-war, then you wouldn’t need to wear this many clothes merely to walk between one room and another, sir.

“Here attached a picture of me with the Homburg,” writes Luigi Sbaffi. “The photo was taken in Oxford last spring.”

Looks more like winter to us, sir, but let’s not quibble. How refreshing to see a Homburg paired with black tie, as it should be, especially in Oxford.

“Upon arrival at the Abbey, the King will be reminded of the health and safety regulations and shown where the fire exits are. He will also be asked for a voluntary donation to the Abbey’s restoration fund. He will be escorted down the nave by the Garter King of Arms, the Beige Dragon Pursuivant, a phalanx of Pearly Kings and four whirling Dervishes”

So many years have passed since the last royal coronation took place that at the time I was still being referred to as ‘Arbuthnot minor’ and ‘Arbuthnot –detention’ by various schoolmasters. So it was with some trepidation that I answered the

call from the Palace and agreed to advise them on sundry aspects of this forthcoming beano. I was told that King Charles wished to ‘modernise’ and ‘slim down’ the ceremony, and also to include all faiths rather than just that of the Bolshevik C of E. Happily, I have experience of events of this

importance and dignity, having once organised a stag weekend in N’Djamena. Since I have insider knowledge of how the big day will proceed, I thought it only fair to warn readers of The Chap what to expect, and how the ceremony will differ from that of Elizabeth II’s coronation.

The King expressed an interest in using a dry-slope skiing centre for the ceremony, but the only one which has an appropriate licence is Cleethorpes Alpine Wonderland, and to book that for a Saturday would cost the taxpayer £400, and in these times of austerity this would seem like flippant spendary, so I advised against it.

King Charles is known to be a strong supporter of green issues, and therefore neither the internal combustion engine nor methaneproducing horses will be used. Instead, he will be conveyed to Westminster Abbey in a gold-painted dogcart pulled by eight of the late Queen’s favourite Corgis, led by the alpha male, Pickles Peregrine ap Rhys. The Groom of the Scoop will follow close behind. The King will be accompanied by his emotional support animal (a gerbil called Carlos) and the procession will be escorted by a squadron of the Blues and Royals

on pre-paid Santander bicycles. The Thames will be patrolled by the Special Boat Service in kayaks and pedalos. The King will have ‘preloaded’ for the ceremony beforehand, by listening to noted thespian Mr. Raymond Winstone give a medley of stirring speeches from Shakespeare’s more bloodthirsty plays.

Upon arrival at the Abbey, the King will be reminded of the health and safety regulations and shown where the fire exits are. He will also be asked for a voluntary donation to the Abbey’s restoration fund. He will be escorted down the nave by the Garter King of Arms, the Beige Dragon Pursuivant, a phalanx of Pearly Kings and four whirling Dervishes. It is expected the King will do away with the more archaic dress code and instead wear military uniform rather than knee-breeches. To show he is a man of the people, he will wear the ceremonial uniform of a corporal in the Royal Army Pay Corps.

Once the King has taken an oath and made the Accession Declaration, an ecclesiastic presents a Bible to the sovereign, saying “Here is Wisdom; This is the royal Law; These are the lively Oracles of God; You the Man!” Instead of the King James

version, a modern rendering of the Bible, Jesus Is My Co-pilot, will be presented. The King will then proceed to the throne for the anointing, having first checked that Prince Andrew has not placed a whoopee cushion on it. Due to an administrative oversight, the Dean will have forgotten to fill the ampulla with consecrated oil, so a bottle of ‘Be Good to Yourself’ French dressing, found in the sacristy fridge, will be substituted. While performing the anointing, the Archbishop recites a consecratory formula recalling the anointing of King Solomon by Nathan the prophet, Zadok the priest and Ming the Merciless.

While the anointing is happening, the Queen Consort will nip out to the royal smoking area by the dustbins, where she will graciously accept a Woodbine from behind the ear of one of the footmen.

The sovereign is then enrobed in the colobium sindonis (shroud tunic), over which is placed the supertunica and regulation high-vis gilet. He then checks the hallmarks on the Crown Jewels and buffs the sceptre with the royal sleeve. The King

will lighten the proceedings by muttering “Left a bit, right a bit” in his Neddie Seagoon voice, as the Archbishop of Canterbury places St Edward’s crown on his head. At this moment, the guests in the Abbey cry in unison three times, “God Save the King!” and “Death to the French!” The trumpeters sound a fanfare and church bells ring out across the kingdom, as gun salutes echo from the Tower of London and tutting echoes from the Labour front bench.

Normally the sovereign would leave the Abbey to the sounds of the choristers belting out Top 20 hits from Purcell and Handel. However, in his zeal to modernise the ceremony, King Charles has decreed that the music will reflect the four sovereign nations of the United Kingdom. Therefore, the melodies will be provided by popular Belfast beat combo Stiff Little Fingers (Northern Ireland), The Wurzels (England), the Bay City Rollers (Scotland) and Cardiff crooner Shakin’ Stevens (Wales).

Historically, the coronation was immediately followed by a banquet held in Westminster Hall,

but this year’s afterparty will be held at Pizza Express in Woking, due to the substantial discount now offered the royal family. Traditionally the King’s Champion (the office being held by the Dymoke family) would ride into the hall on horseback, wearing a knight’s armour and throwing down a gauntlet, and make a proclamation of the readiness of the champion to fight anyone denying the monarch. The current King’s Champion is Tyson ‘Irongloves’ Montmorency de Coverley Dymoke, a scrapmetal dealer from Bermondsey, who will break with tradition by making the proclamation barechested from the car park of the Lamb & Flag: “Verily, if thou reckon thyself a little bit tasty, come and have a go.”

By the end of the day, the nation will be in a state of stupefied contentment. They will then settle down to celebrate like their Anglo-Saxon forbears by eating coronation chicken sandwiches, quaffing chilled continental lager and watching reruns of Dad’s Army on the television. n

1. All pillar boxes must be painted gamboge for the day of the coronation.

2. For a month before the ceremony, binary messages will be beamed into outer space asking aliens not to invade on 6th May.

3. The Archbishop of Canterbury can request that his fee for the day is paid in hogsheads of brandy or lottery scratchcards.

4. Due to the limited seating, peers decide which of them will attend the ceremony by a game of British Bulldog in Windsor Great Park.

5. Daily newspapers are prohibited from printing cryptic crosswords on a coronation day.

6. Airline pilots are only allowed to announce the moment of crowning on their tannoys if they are flying over a part of the map that used to be coloured pink.

7. It is both against the law (1648) and compulsory by law (1847) to wear gloves during a royal coronation.

8. A space at Westminster Abbey is reserved for a big game hunter, in case any wild beasts invade during the ceremony. This is due to the King’s fear of being eaten by a polar bear.

9. It is considered good luck to invite a tobacconist into your house on the day of a coronation.

10. Jose Cuervo Tequila and DFS Sofas are the official sponsors of the event.

11. By royal tradition, on the night before the coronation King Charles will let off all the fire extinguishers in Buckingham Palace.

12. On the day after a coronation, commoners are allowed to walk around Regent’s Park in an anti-clockwise direction.

An advice column in which readers are invited to pose pertinent questions on sartorial and etiquette matters, and even those of a romantic nature. Send your questions to wisbeach@thechap.co.uk

Craig Feltham: I should like to dress appropriately to watch the King’s coronation on television on 6th May this year. Could you advise me whether black tie, morning dress or tweeds are the correct attire?

Wisbeach: This all depends on whether you are watching the coronation ‘live’ during the morning of the sixth, or whether you are watching it on a ‘catch-up’ service later in the evening. If watching it live, then Wynciette pyjamas, a silk dressing gown with a vibrant pattern (peacocks or fleur-de-lys, for example) and a pair of velvet Albert slippers with an embroidered royal crest in gold would be suitable. If watching in the evening, then full military ‘Number 1’ kit must be worn, for whichever regiment you belong to. White cotton gloves are traditional, though not obligatory, as they make it difficult to use the mute button on the remote control during the adverts.

Montague ‘Chaps’ Gristle: I have a Landing Craft Utility (LCU MK.10) as I prefer their versatility to a motor car. Imagine my chagrin when I received a parking ticket for exceeding my time at J Sainsbury in Cheam. The Parking Warden said that the LCU was occupying a space that could have fitted 50 cars, end to end. I am of the opinion that I shouldn’t pay the fine, as my LCU is more boat than car. Do you agree?

Wisbeach: I am in total agreement, sir, and believe you should contest the fine. If the local council’s parking department still insist, I would pay their office a visit in your LCU, and see how many parking tickets they issue when their building has been razed to the ground. ...

Simon Creasewell: I have heard that British club ties have the stripes running from left kidney to right shoulder, whereas American ties have the stripes running ‘to the heart’, from right shoulder to left kidney. But what if the stripes are horizontal? Which nation does the tie hail from, in that case?

Wisbeach: You are quite correct, sir, and this tradition is said to originate from the way in which

rifles were slung over soldier’s shoulders; in the US from right to left and in the UK the other way round. A British officer wearing a regimental tie under his uniform would never countenance the stripes going in the opposite direction to his rifle. As to the national origin of a tie with horizontal stripes, sir? Most probably French. ...

Montague ‘Chaps’ Gristle: My bunions are giving me the jip. Transporting an ice pack or a bag of peas wrapped in a tea towel in my valise is grossly inconvenient. When I use one on the bus, my fellow passengers pointedly stare out of the window as I nurse my ailments. The advice I read on the NHS website regarding bunions is ‘Do not wear high heels or tight, pointy shoes’. I do not. What should I do?

Wisbeach: The NHS advice is sound, on a general sartorial level as well in the case of bunions, for no gentleman should wear high heels or pointy shoes, unless they work in the theatre. One should instead, when faced with this condition, take a sartorial tip from Mr. David Hockney and wear a boldly checked tweed three-piece suit and a pair of Crocs, preferably in yellow (see page 71).

campfire, where local tribesmen are cooking goat. Around me are the glories of the mountains. It is a beautiful place to be, Wisbeach. So beautiful that it has inspired me to write a poem, which I have titled On Tirich Mir, in the Hindu Kush. I have written four stanzas, but now seek my final rhyming couplet. The penultimate line reads “Oh, how happy I am to be, on Tirich Mir, in the Hindu Kush.”

Can you please furnish me with the last line and a word that rhymes with ‘Kush’. All I’ve been able to come up with is ‘tush’, ‘bush’ and ‘mush’.

Wisbeach: More than happy to oblige, sir, though please bear in mind that I am no Pam Ayres; I shall nevertheless do the best I can.

It is so magnificent here, on Tirich Mir, that I do declare it makes my mind go whoosh.

I respectfully request readers, in future, to make enquiries of a more sartorial nature, which can be sent to me at wisbeach@thechap.co.uk n

Montague ‘Chaps’ Gristle: I am on the peak of Tirich Mir, in the Hindu Kush. Below me I can smell a

Chris Sullivan meets the Midlands-born actor who has played gritty characters in British indie films, television goodies and baddies and, most recently, the doomed King Viserys in House of the Dragon

In all my decades as interviewer of both actors and directors for many of the UK’s finest broadsheets, I cannot recall any actor of renown who is less up himself than Paddy Considine. He seems like a man who has inadvertently become famous for doing something he never had ambitions to do and, even though he is extremely adept, still seems rather surprised at his success.

“I’ve never had a plan,” chuckles the amiable thespian, sitting in the Harley Davison Office in Fitzrovia, casually dressed in jeans and leather jacket. “I feel as if I’ve been shifted along towards this almost by accident and coincidence. I didn’t start acting till I was 25. Before then I’d only done the odd school play. So I always had a career as a

“I go to Hollywood and people blow smoke up my backside for a week and tell me I’m the greatest thing that ever lived, and I have no problem with that. It doesn’t go to my head, as I know that they will do the same to the next person who walks through the door. I find it really funny”

filmmaker, someone behind the camera rather in front of it, at the back of my mind.”

Considine’s first acting role came via his friendship with eminent director Shane Meadows. “We met at Burton College,” recalls the actor fondly. “And became this combustible duo who you either loved or hated but could not ignore. We even had a band together, with me drumming and him singing. Shane asked me to be in his film, A Room for Romeo Brass, so I gave it a go and became an actor because of that film, which is the most important and favourite movie I’ve done. Everything rolled on from that.”

“In school Paddy never did anything good in the workshops,” says Meadows, director of This is England, among many other triumphs, “but once you got him in the canteen, he could mimic anyone. Paddy would come over to my place and put on these different guises, catch a glimpse of himself in the mirror and literally would drop straight into that

character. When Paddy first saw my films, TwentyFour Seven and Small Time, he realised he had to give acting another go. After making A Room for Romeo Brass, he said he didn’t realise making film could be like that... and it was quite a revelation for him. He is a natural.”

Considine attracted the attention of James Sheridan, the Dublin-born director of My Left Foot, Bloody Sunday and In the Name of the Father, who cast him in the lead role for In America (2002). Considine’s rendering of Johnny Sullivan, an Irish fellow who’s moved to New York with his family in search of a better life but finds the polar opposite, was unimpeachable to the last twitch of his jaw. “Talk about being thrown in the deep end,” says Considine, still obviously taken aback. “I thought, ‘Oh God, Jim made all these films with Daniel DayLewis, so what am I going to give Jim that Daniel hasn’t?’ But Jim was Ireland’s top filmmaker and my Irish dad was dying at the time, so I took a chance

and did it for my dad so he could be proud of me. Unfortunately, my father died just before filming started. Still, I learned a lot about how to work with actors from Jim and it put me on the map.”

Now highly regarded as an actor who always delivers the goods in a rather quiet, no-nonsense way, Considine was born on 5th September 1973 in Burton on Trent, Staffordshire. He grew up in a council estate in Winshill at the North of the city, with his brother and four sisters. His entrée into the world he now inhabits came in 1990, when he enrolled on a National Diploma in Performing Arts at Burton College.

“I dropped out of the drama course, though, and had no desire to be an actor whatsoever,” he recalls, his Midlands accent totally undiminished. “I then worked on building sites, was unemployed and used to hang out at the college. It was somewhere to go even though I wasn’t on a course. Then Colin Higgins, the photography, film and video tutor

caught me hanging about and got me to do a course in editorial photography. I ended up having photos in The Guardian and Independent and I loved it.”

Nevertheless, after stand out parts in the likes of 24 Hour Party People and Close Your Eyes, he took the bull by the proverbials and made his indelible mark. For his next feature, Shane Meadows’ Dead Man’s Shoes (2004), Considine co-wrote the screenplay with the director. His rendering of the disillusioned army veteran Richard, who returns to his hometown in the Peak district to exact merciless revenge on the gang of drug dealing brutes who bullied his younger brother, is pitch perfect. Reminiscent of Clint Eastwood in High Plains Drifter, Paddy’s silent authoritative menace and sense of purpose are unassailable and gripping to watch.

Now very much a name to drop in cineaste circles, your man excelled in such award-winning pictures as Pawel Pawlowski’s My Summer of Love (2004) alongside Emily Blunt. In 2005 he shone in

both Cinderella Man opposite Russell Crowe, and as Brian Jones’ suspected murderer in Stoned, and in 2007 stood out in The Bourne Ultimatum. He then

entered our living rooms in earnest as Assistant Chief Constable Peter Hunter in Red Riding: the Year of Our Lord 1980 for Channel 4 in 2010, part of a landmark trilogy that fictionalized accounts of the investigation into the Yorkshire Ripper.

“Selling out doesn’t sit well with me,” admits the actor, who was diagnosed with Asperger’s syndrome in his thirties. “I go to Hollywood and people blow smoke up my backside for a week and tell me I’m the greatest thing that ever lived, and I have no problem with that. It doesn’t go to my head, as I know that they will do the same to the next person who walks through the door. I find it really funny. But I’m lucky to be offered the good work, and being in the right place helps, as does working with the right people and making the right choices.”

In 2011 he wrote and directed his first full-length feature Tyrannosaur, starring Perter Mullan and Olivia Coleman, a solid chunk of urban realism featuring turns that are staggeringly authentic.

“I feel more comfortable as a director. When they say ‘action’, I feel as if someone is putting handcuffs on me rather than letting me off the hook. But with directing I feel free, as a big part of directing is managing actors to get the best out of them and make them feel as if they are doing something worthwhile”As Father John Hughes in Peaky Blinsers

“I feel very fortunate that I was allowed to direct, as it can be very cathartic, but it takes guts, tenacity and a stubborn resolve to get films made. But I feel more comfortable as a director. I feel as if the pressure is off. I always feel intimidated as an actor because I feel I am not doing a good enough job, which isn’t very productive, as the best creativity (and fun) comes from being uninhibited. When they say ‘action’, I feel as if someone is putting handcuffs on me rather than letting me off the hook. But with directing, I feel free, as a big part of directing is managing actors to get the best out of them and make them feel as if they are doing something worthwhile.”

In 2016, while rendering Father John Hughes in series 3 of Peaky Blinders, Considine was prepping his second feature as an auteur, but this time he would also play the lead role. Journeyman (2017) tells of Matty Burton, middleweight boxing champion of the world, who sees the twilight of his career on the horizon, and knows that he must soon retire but first

make enough money to secure a home with his wife Emma and a future for their infant daughter Mia.

“I’ve loved boxing since I was a kid and have always had this assumption that I would play a boxer, but wasn’t sure how that would manifest itself,” he explains. “I started writing this in 2009 and didn’t want to do a standard boxing movie. I wanted to do my boxing movie, and the way it ended up, my character could have been a racing driver, a jockey or a rugby player, as it was more about him overcoming these extreme obstacles that come his way than the boxing. When I started writing it, I didn’t know he was going to collapse injured and suffer brain injury and the disintegration of his world. That came out of nowhere, but I pursued that idea as I thought that was where I should go.

“For me the most challenging aspect was not the acting, directing or the boxing, it was the edit. I did a 12-week training camp and it was great. I trained in the mornings then did reccies in the afternoon. I

was on a regimented diet and a regimented life and I loved it once I was in it. But I’m not comfortable watching myself, so the edit was tough because I was really hard on myself. But I remembered being enthralled by filmmaking as a teenager and asking the head of year on my drama course how I could become a film director, and he said ‘You could never be a film director, Considine!’ And I believed him. But even though it took a while, I’ve directed two films now, so always follow your dreams.”

Considine has recently turned to long format television and delivered cracking performances in four TV series: Informer, The Outsider, The Third Day and more recently House of the Dragon. The prequel to Game of Thrones sees Paddy as King Viserys – replete with long tresses tumbling past his shoulders that could rival every aged rock star –overshadowing nearly all his fellow cast members. For most actors, being tied to such a huge and long running production is usually a blessing, but not for Considine.

“I was really happy about having only one season and to be able to tell a story and have a

beginning and an endpoint like that,” he says. “And to fully develop a character and go on a journey with him was a real blessing.” The actor charts his character’s demise into a painful death. A difficult task by anybody’s measure, but for Considine it was rather beguiling.

“I am a big fan of an artist called Richard Hamilton and I watched a documentary on him. He was someone who got cancer later in life. He was a drug addict, and he got what looked like scoliosis. I watched that, and I’d spoken to [coshowrunner and director] Miguel Sapochnik about visuals of him, going, ‘This is kind of where Viserys should end up physically.’ A lot of it was informed by where the first lesion started at the base of his spine and how this thing’s just eating off his body. He’s just dying a very, very slow death. So that wasn’t a creative choice for me.”

But despite giving, according to many pundits, the performance of his life, Considine said his rendition had its issues. “It was a couple of days and it wasn’t just difficult in an emotional way, but it was also difficult to shoot. I was lying in that bed for

hours and hours and doing that kind of breathing. The strange thing that happens is you think you’re just acting, but what happened when I was breathing that way was after a few hours my oxygen levels went straight down.

“I had my levels measured and they said, ‘We’ve got to get out of here; you need to get outside.’ And it was interesting because it was almost like my brain was telling my body how to breathe and my physiology was reacting to it, so my oxygen was dropping down. So, I actually felt like I was dying, which was fun.”

The subsequent result of all this effort is that millions upon millions of Game of Thrones fans now know exactly just who Mr. Patrick Considine is. “I hate the idea of being a celebrity,” sighs the actor who still lives in the town where he was born, with the girl he first met aged 18 and married in 2002, with their three children. “If I ever thought that was happening I’d disappear and go and make shoes like Daniel Day-Lewis did after Gangs of New York.”

“Where I came from, we had nothing to lose and no one ever told me to stop dreaming, but

there is a lot of shit you have to go through to move into this other world. It’s not easy to overcome being root bound, but you have to try, as you never know what you might succeed in. When I was a kid I wanted to be Adam Ant, I was obsessed with him [He shows me his tattoo of Adam Ant on his forearm] and how could I do that? But I remember kids on the estate getting punk bands together when I was young kid, and me being so impressed and inspired by that DIY punk ethic – to get off your arse and try something, even if you’re untrained and even if you fail, you still know you’ve tried.”

Indubitably, the punk rock dogma did work for Considine. What’s your greatest achievement? I wonder aloud.

“Getting my college degree, that was my greatest achievement, but nothing to do with films. I think my mum would have been more pleased with the fact that I have been married for 26 years and have three wonderful children, and have been a decent husband a good father. There is nothing I could do professionally that would have made her prouder of me than that.” n

If you thought House of The Dragon's Targaryens were an odd bunch, Stephen Arnell introduces us to the Capets – the ‘Accursed Kings' who inspired the original books on which Game of Thrones was based

Although many believe England’s Wars of the Roses (1455-87) between the rival related houses of Lancaster and York was the basis for George R. R. Martin’s epic series of novels A Song of Ice and Fire, they would be sorely mistaken.

The Wars of the Roses obviously has some influence on the fictional events in Westeros, but, according to Martin himself, the chief inspiration was author/politician/literary grandee Maurice Druon’s seven-volume cycle The Accursed Kings, based on the lives of the final Capetian monarchs of medieval France.

Writing in 2013, Martin stated, “The Accursed Kings has it all: iron kings and strangled queens, battles and betrayals, lies and lust, deception,

“The Accursed Kings has it all: iron kings and strangled queens, battles and betrayals, lies and lust, deception, family rivalries, the curse of the Templars, babies switched at birth, she-wolves, sin and swords, the doom of a great dynasty, and most of it straight from the pages of history”

family rivalries, the curse of the Templars, babies switched at birth, she-wolves, sin and swords, the doom of a great dynasty and all of it (or most of it) straight from the pages of history. And believe me, the Starks and the Lannisters have nothing on the Capets and Plantagenets. I think Druon is France’s best historical novelist since Alexandre Dumas père.”

Not a bad recommendation, especially if you’re an aficionado of Martin’s oeuvre – as I am, déclassé as some may find that admission. Last Christmas I began to re-read the English translations of all seven novels of Les Rois Maudits (The Accursed Kings), and exceptionally good they are too. Plenty of Game of Thrones-style treachery, sex, violence and religious fanaticism abound – with the difference being that Druon’s thoroughly researched books are all chiefly based on recorded history.

However, in tone there is an enormous contrast compared to Game of Thrones, in which many of the characters have at least some redeeming features and motivations. In Les Rois

Maudits there is precious little in the way of empathy for the characters, almost all being fairly vile, with even the less awful ones demonstrating self-interest as their abiding motivation.

Druon’s series is akin to the historical novels of the largely forgotten Alfred Duggan (1903-64), which are enjoyably free of the sentimentality that plagues many others in the genre. For those wishing to sample the work of Duggan, Three’s Company (1958), following the tragi-comic career of overlooked Roman Triumvir, the hapless boob Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, makes a good starting point.

But back to Les Rois Maudits. The period covered by Druon’s magnum opus is High Middle Ages France, between reigns of the last four kings of the Capetian dynasty and the first two kings of the succeeding cadet branch, the House of Valois. The English Plantagenets also feature, in the form of the frankly useless Edward II, his duplicitous wife Isabella (the ‘She-Wolf of France’) and their son, the chivalrous Edward III.

Druon himself aspired to a less middlebrow readership than the best-selling The Accursed

Kings appealed to, but compared to many of today’s historical fiction novels they are more akin to Robert Graves (I Claudius/Claudius the God) than Bernard Cornwell (Sharpe) or Ken Follett (The Pillars of the Earth etc). According to the Independent’s French correspondent John Lichfield, a personal friend of Druon, “Les Rois Maudits was written to make money very quickly; he himself was not very proud of it.”

Like fellow writer Romain Gary (The Roots of Heaven), Druon was a staunch Gaullist and served in the Pompidou administration as minister of culture (Gary had been a diplomat). For the French, Druon will always be remembered as the co-writer of the Resistance anthem Chant des Partisans, the song that followed General Charles de Gaulle’s radio announcement to the French people in June 1944 that liberation was under way.

The first six novels in the series were completed in a spurt from 1955-60, with the last, somewhat disappointing entry, Quand un Roi Perd la France (The King Without a Kingdom) published 17 years later in 1977. In this, Druon mirrored the late Colleen McCullough (1937-2015), whose superb six-novel Masters of Rome series (1990-

2002) was so popular that she was cajoled by fan pressure to write the merely average seventh instalment (Antony and Cleopatra) in 2007.

The Accursed Kings proved popular enough to be adapted twice (in 1972 and 2005), with even a spoof TV version in 1973 – Les Maudits Rois Fainéants (The Damned Lazy Kings). Both versions are available to watch free on YouTube, but only the 2005 mini-series has English subtitles. According to George R.R. Martin, the original series was popular enough to be known as the French I, Claudius – although the show actually predates the BBC adaptation of Graves’ books.

A recent re-viewing of the 2005 series version of The Accursed Kings revealed a truncated tale compared to the novels, and the Brechtian style (set-bound, with exaggerated Gothic/ German-Expressionist architecture) was distancing, although I did watch every episode, a testament to the strength of the storyline.

The 1972 show starred Jean Piat as chief protagonists Robert d’Artois (a kind of protoDaemon Targaryen) and Hélène Duc as his venomous aunt Mahaut (comparable to the ‘Queen of Thorns’ Olenna Tyrell).

In the 2005 series, Philippe Torreton (Monsieur N) and Jeanne Moreau played the scheming rivals in 2005, with Gerard Depardieu as doomed Knights Templar chief Jacques de Molay and Tchéky Karyo (Baptiste) as the somewhat ironically named King Philip the Fair (no softhearted Viserys he). Hélène Duc returned to play Mme de Bouville in the later adaptation.

In an odd quirk of fate, all three lines of the House of Capet (excepting the final brief usurpation by the cadet Orléans branch of Louis-Philippe, 1830-48) ended in three heirless brothers who took the throne in succession when the elder died:

The Capetians (987-1328): John I, Philip V & Charles IV

The Valois (1328-1589): Francis II, Charles IX & Henry III

The Bourbons (1589-1792, 1814-1830): Louis XVI, Louis XVIII & Charles X

In the UK, BBC2 got in on the act with the similar The Devil’s Crown (1978), a lowish budgeted depiction of the first three Plantagenet Kings of England. Brian Cox (Succession) starred as Henry II in the series. Other cast members included Kevin McNally (Harold Wilson in the recent Stonehouse) as Henry the Younger and Freddie Jones (The Elephant Man) as Bertran de Born. The second Doctor

Patrick Troughton appears as William Marshal, 1st Earl of Pembroke.

All thirteen episodes of The Devil’s Crown are available to watch on YouTube, as is the eight-part Cleopatras, where you can enjoy the ripe performances of Richard Griffiths (Withnail & I) as King ‘Potbelly’ Ptolemy and a similarly scenestealing Graham Crowden (Waiting for God) essaying crafty royal tutor Theodotus. n

Stephen Arnell is the author of The Great One, a satirical mystery novel set in the civil wars of the Roman Republic

Gerard Depardieu starred in the 2005 mini-series as Knight Templar Jacques de MolayHe finally achieved long overdue screen stardom in Carry On Nurse as Jack Bell. Phillips dominates the ward, despite only appearing at the 44-minute mark. Bell is insouciant, debonair and an overgrown schoolboy, making ‘Hello!’ sound like the invitation to a weekend in Brighton and ‘Ding Dong!’ a phrase of harmless lubriciousness

“Nor did Phillips possess the seediness of Terry-Thomas’s rotters, who conveyed the air of one forced to resign his commission just before an investigation into the NAAFI accounts in Valletta. By contrast, Phillips was frequently eager to impress, forever devising another brilliant plan and hoping the valiant cry of ‘Left hand down a bit!’ would save HMS Troutbridge of The Navy Lark from yet another disaster”

The year is 1979, and the place is a Hampshire village so dull that a typical headline in the local newspaper might be ‘Hughie Green Opens New Bus Shelter’. Fortunately, the BBC is doing its best to alleviate boredom with Crooks Anonymous – a 1962 film with many of the essential ingredients for a comedy of quality. There is the black and white cinematography, the police Wolseley 6/90s with

clanging bells, and the familiar faces of Raymond Huntley and Colin Gordon. But, most importantly, there was a stellar performance from Leslie Phillips as ‘Dandy’ Forsdyke, with a poise that David Niven and Cary Grant might have applauded and would have had Rex Harrison seething with envy.

Crooks Anonymous would be the logical starting point if a chap needed to provide a guide to Leslie Phillips’ films for the novice viewer. It is the second

in a trio of comedies helmed by Ken Annakin, following Very Important Person and preceding The Fast Lady, all starring Leslie Phillips, James Robertson Justice and Stanley Baxter. At the heart of the narrative, Forsdyke is elegant without being flamboyant, guileful yet harmless and always likeable. It is also plausible that Julie Christie’s ‘Babbette’ has fallen for this entertaining bounder, played by a master of light comedy. The cast may contain some of the finest scene-stealers known to British Equity, but even when Wilfrid Hyde-White is on screen, Phillips effortlessly dominates the proceedings.

By Crooks Anonymous’s release Phillips was 38, with a film career that had commenced in the late 1930s. As with his near contemporaries, Laurence Harvey and Peter Wyngarde, his image was due to self-invention via Italia Conti and a wartime commission in the Royal Artillery. Devotees of British cinema may be surprised to hear Phillips use his original Tottenham vowels as a locomotive fireman in a 1949 Ealing drama, or his cameo, sans moustache, as a Birmingham police sergeant in 1953’s Time Bomb.

Wardour Street did not initially know how to use Phillips, and he featured in various supporting roles, including the 1955 science-fiction drama

The Gamma People. Of course, few true cineastes could resist an immaturely blazered Phillips as a

photographer helping to defeat a mad scientist who subjects bit-part actors to electromagnetic radiation. However, it was theatre that showcased his talents, and in the stage adaptation of The Diary of a Nobody, Phillips played a role that anticipated his future screen characters. Lupin Pooter is brash, witty, and insistent on everyone having a jolly time – whether they wish to or not.

1957 saw the release of Les Girls, Phillips’s one foray into mainstream Hollywood; he subsequently noted, “I didn’t want to become the poor man’s David Niven”. Two years later, he finally achieved long overdue screen stardom in Carry On Nurse as Jack Bell, a bunion operation patient and genial bounder. The second entry in the series is replete with delightful performances, notably from a magnificent Hattie Jacques and a thoughtfully understated Kenneth Williams. Still, Phillips dominates the ward, despite only appearing at the 44-minute mark. Bell is insouciant, debonair and an overgrown schoolboy, making ‘Hello!’ sound like the invitation to a weekend in Brighton and ‘Ding Dong!’ a phrase of harmless lubriciousness.

Phillips made two more Carry Ons and three other comedies for Peter Rogers and Gerald Thomas, before making a typically well-timed exit. The parsimonious £sd rates were one reason for his departure, and another was fear of stereotyping. Rogers’ wife, Betty Box, offered

greater scope for his abilities in the Doctor series, supporting Michael Craig in 1960’s in Love and starring in 1966’s in Clover and 1970’s in Trouble. That the last-named – a would-be ‘swinging’ conclusion to the series guest-starring Simon Dee – is remotely watchable is almost entirely due to Phillips. Dirk Bogarde temporarily returned as Simon Sparrow for 1963’s Doctor in Distress, and the two actors’ approaches to comedy acting could not be more diverse. Phillips was relaxed yet eager

and only temporarily cowed by Sir Lancelot Spratt referring to him as a ‘nincompoop’. Meanwhile, the ‘Idol of The Odeons’ Bogarde conveyed the sardonic disdain of one obliged to fund his arthouse career by returning to commercial cinema.

By the time Doctor in Love went on general release, Phillips’s image as a bounder du jour was firmly established with the nation’s cinemagoers. Leslie might try to sell you a case of ‘the finest Empire claret, old boy!’ but was seldom a threat, unlike the dangerous Mayfair lounge lizards of Laurence Harvey. Phillips might devise a ‘wizard plan’, while the saturnine Dennis Price would invite you to his club, only to stab you in the back as Nigel Patrick poured you a brandy. Nor did Phillips possess the seediness of Terry-Thomas’s rotters, who conveyed the air of one forced to resign his commission just before an investigation into the NAAFI accounts in Valletta. By contrast, Phillips was frequently eager to impress, forever devising another brilliant plan and hoping the valiant cry of ‘Left hand down a bit!’ would save HMS Troutbridge of The Navy Lark from yet another disaster.

A T-T-style bounder would also use his military titles in civilian life, as if clinging to the wreckage of their service career. But Phillips tended to play amiably lascivious professionals who, as with Kenneth More’s Ambrose Claverhouse in Genevieve, have quickly adapted to the first stirrings

“The promotional gimmicks for Spanish Fly included a string bag containing a record by Geraldine singing Fly Me and, in a discreet plain envelope, a pair of frilly green knickers. All of which sounds more entertaining than the actual film, and in 1981 Phillips decided he would no longer play ‘lecherous twits with suave chat-up lines and dysfunctional trouser braces”With Jeremy Lloyd in Doctor in CLover (1966)

of consumerism. With The Fast Lady, Freddie Fox (Phillips) may sell a 1927 Bentley to Baxter’s hero, but he was equally at ease behind the wheel of an MGA. Phillips’s acting range could have easily encompassed Freddie Page of The Deep Blue Sea, but his characters tended to anticipate the next adventure rather than hark back to the Battle of Britain.

The treasurable sequence that best demonstrates this Phillips trait is Gaston Grimsdyke exploring Carnaby Street in Doctor in Clover, accompanied by Kiki Dee’s Take a Look at Me. This may be an alien world to our hero, but he is prepared to give it a jolly good try. The sixth Doctor comedy further benefits from the utterly charming screen partnership of Phillips and Robertson Justice, the latter ever eager to please his surrogate father figure. Richard Roud of The Guardian may have considered the series provided ‘people of an arrested mental or sexual development the chance of indulging themselves with a relatively clean conscience’, but the critic was clearly a mouldy fig. Such indelible screen moments have the power to linger in the memory while countless lumpenly expensive Hollywood productions remain mercifully forgotten. Similarly, the 1950s and early 1960s was an era where various tweed-jacketed types were oft heard to utter the immortal line ‘Gosh!’ throughout Pinewood and Elstree, but

Phillips was never of their number. His playing was effervescent, just as certain juvenile leads were as charismatic as a Morris Oxford. Phillips would promise the female lead dinner at ‘this little trattoria’ he knew, while the tweed-jacketed leading man planned to spend 10/- on afternoon tea at the Lyons Corner House.

Alas, 1970s British cinema presented Leslie with far fewer opportunities. His output reached a possible nadir with 1975’s Spanish Fly, co-starring with T-T in a slightly less hilarious narrative than the test card. As Michael Davie wryly noted in The Observer, the promotional gimmicks included a ‘Spanish string bag containing a record by Geraldine singing Fly Me and, in a discreet plain envelope, a pair of frilly green knickers’. All of which sounds rather more entertaining than the actual film, and in 1981 Phillips decided he would no longer play ‘lecherous twits with suave chat-up lines and dysfunctional trouser braces’.

That some were surprised by Phillips’ later stage roles in Chekhov, Shakespeare, and Tennessee Williams is a depressing indictment of how the art of British comedy actors is so often misunderstood. As with other masters of screen humour, Phillips had a wonderfully malleable face that could also express pain and barely suppressed anger. It is far from impossible to envisage him as one of the angry, damaged post-war failures as played by Denholm Elliott or Dudley Foster.

Leslie Samuel Phillips CBE died aged 98 on 7th November 2022; that he was not ‘Sir Leslie’ is a testament to Britain’s frequent neglect of its finest comedy actors. If one had to select his most indelible performance, this writer would have to cite Dandy Forsdyke, as first sighted on a Ferguson 20inch set. Crooks Anonymous is a picture that dates just before the arrival of The Sixties proper, with Julie Christie cast as a Liz Fraser-style ‘dolly bird’ and bearded curmudgeons berating their inadequate subordinates. With a leading man of lesser renown, the result would have been an entertaining way of passing the time. But with Leslie Phillips as the star, the result is one of those minor gems of British cinema that connoisseurs would avidly seek on television schedules.

As Penelope Gilliatt wrote in her seminal Unholy Fools: Wits, Comics, Disturbers of the Peace: ‘The funniest men always seem independent of your opinion. You take them or leave them’. Or to quote the great man himself – ‘Ding dong, you’re not wrong!’ n

Chris Sullivan’s interest in the zoot suit began purely as an anti-fashion statement, before he discovered the chequered history of the oversized outfit that made the zoot suit one of the most politically sensitive clothing items of the early 20th century

Unnaturally obsessed with film noir as a lad in 1973, I was overjoyed to see a fashion shoot in a Club International nudie mag I’d purloined from a newsagent in my home town, which featured tailored zoots from Malcolm McLaren and Vivienne Westwood’s Let It Rock store. Two years later found myself in London buying vintage suits from Beaufort Market, big ties from Retro and black-and-white shoes from Acme Attractions. I’d wear this gear dancing to raw US imported funk in clubs like Crackers.

I even managed to get myself an ice-creampink Mal and Viv zoot from the Westwood store, which was now called Sex. Meanwhile I became a teenage zoot spotter ‒ eyes glued to the TV, clocking every stylish instance in the movies of the 1940s.

In 1980, having no truck with the futurist music and camp fashions that were all the rage at clubs like the Blitz, I turned the clock back and started DJ-ing funk and Latin music and wearing 1940s clothes. That summer, after a trip to New York, I formed my own Latin-funk band, Blue Rondo à la Turk, and, having discovered a book, The Zoot Suit Murders, realised the social importance of this stark silhouette.

Blue Rondo penned our first composition, Me and Mr Sanchez, after Thomas Sanchez, author of The Zoot Suit Murders. I then designed my very own zoot and commissioned Bob the Tailor of Aldgate ‒ whose pattern cutter was coincidentally a Chicano who had been involved in the aforementioned riots as a teen ‒ and started a night at Le Kilt (the first of the clubs to devote itself almost entirely to rare groove), which served as a necessary haven for all those of a similar stylistic persuasion.

“What is certain is that the zoot spread through the working classes like wildfire, becoming a coveted item that some today might describe as ‘bling’. Due to the amount of fabric used, you needed a good few bucks to acquire a zoot”

“The suit is a widelapelled, knee-length ‘killer-diller’ coat with a drape shape, shoulders padded ‘like a lunatic’s cell’, while the deeply pleated trousers balloon to 32" at the knee and 14" at the ankle. Worn with a large Fedora with feather, fat tie and spearpointcollared shirt, the look, when it first appeared among late 1930s hep cats in urban jazz saloons, was radical to say the least”

Of course, the band, the club and the style took off like a rocket, and soon I launched my own range of ready-to-wear zoot suits, in partnership with exAmen Corner saxophonist and style entrepreneur Alan Jones, under the brand Sullivan Suits, which sold all over the country in shops such as Demob in London and Paradise Garage in Bristol.

Headlines (usually ‘Zoot Alors’) in The Face, L’Uomo Vogue, The New York Times, LA Times and Paris Match proclaimed the global return of the style, while designers such as Giorgio Armani and Jean-Paul Gaultier created collection after collection featuring toned-down versions of the style, until the oversized, large-shouldered, pegtrousered suit became the signature eighties style. I designed more zoot suits ‒ albeit with my own twists ‒ made by tailor Chris Ruocco of Kentish Town and worn by chart toppers Spandau Ballet, Ultravox, Adam Ant (who wore it for Live Aid) and Madness, to name a few.

The country was soon festooned with fellas in oversized suits, long chains and co-respondent shoes. The conceit was further propagated in 1982, when August Darnell of Kid Creole and the Coconuts fell on the zoot as his chosen look and, due to his chart success, totally eclipsed our usage, and fair play to the man. He did it very well.

More than just an outlandish fashion fad, the zoot suit silhouette defied an era of wartime conformity

and racial prejudice and was a declaration of freedom and auto-determination among beleaguered minorities. The suit itself comprises a wide-lapelled, often knee-length ‘killer-diller’ coat with a drape shape, with shoulders padded ‘like a lunatic’s cell’ (as Malcolm X put it), while the deeply pleated trousers ballooned to some 32 inches at the knee and 14 inches at the ankle. Worn with a large felt Fedora with feather, fat tie and spearpoint-collared shirt, the look, when it first appeared among late 1930s hep cats in urban jazz saloons, was radical to say the least. Exactly who invented the zoot remains under debate. Claimants have included Beale Street tailor Louis Lettes of Memphis, Charles Klein and Vito Bagnato in Manhattan, Lew Eisenstein on 125th Street, and a Detroit retailer known as Nathan (Toddy) Elkus.

Chicago tailor and bandleader Harold C. Fox asserts he made the first zoot suit with the reet pleat, the reave sleeve, the ripe stripe, the stuff cuff and the drape shape in 1941, influenced by underprivileged urban black teenagers. “The zoot was not a costume or uniform from the world of entertainment,” he once said. “It came right off the street and out of the ghetto.”

The word ‘zoot’ was common currency in the jazz circles of the 1930s. Some say it was employed to denote all that was extravagant and slipped into the vernacular to specifically describe said item. Some say that since it was common jazz slang to put a ‘z’ at the beginning of words, so the suit became a zoot, while others claim it was first coined by Mexican-American ‘pachucos’ as part of their street cant, ‘Caló’, and evolved from the Mexican Spanish pronunciation of the word ‘suit’, with the ‘s’ taking on the sound of a ‘z’.

What is certain is that the zoot spread through the working classes like wildfire, becoming a coveted item that some today might describe as ‘bling’. Due to the amount of fabric used, you needed a good few bucks to acquire a zoot. It isn’t difficult to imagine the hatred felt by some poor white Americans as they saw these upstart dandies parade their finery. Little did they know that many of these black and Hispanic ‘zooters’ had toiled on the lowest rung as bus boys, labourers and factory workers for months to buy their threads.

Described as ‘the worst mob violence in Los Angeles history’, the Zoot Suit Riots of June 1943 came about due to a variety of factors, not

One of the original Sullivan Suits at the Axiom fashion show in New York

One of the original Sullivan Suits at the Axiom fashion show in New York

Christos Tolera modelling the first collection of Sullivan Suits

Christos Tolera modelling the first collection of Sullivan Suits

least of them the War. Civil rights were denied to most blacks, while anti-Mexican sentiment had long prevailed. In March 1942 the US War Production Board restricted the use of cloth by 26 per cent, resulting in what Esquire magazine called ‘streamlined suits by Uncle Sam’, causing the manufacture of the zoot suit to be banned. Underground tailors all over the US still produced the item, however, leading the public to view anyone wearing a zoot as a flouting of wartime rationing. The zoot was a red flag to already racist redneck bulls. The truth is that many Mexican pachucos had enlisted in the forces, while much of the cloth used had existed long before war broke out and was old stock.

Another factor was the Sleepy Lagoon Murder. Accused of the 1942 murder of José Diaz, 22 members of the gang known as the 38th Street Boys were put in the dock in the largest mass trial in Californian history. The Sleepy Lagoon Defence Committee was formed by civil rights pioneer Carey McWilliams, and included Hollywood celebrities like Orson Welles and Rita Hayworth, whose involvement further aggravated this controversial affair.

17 of the 22 defendants were convicted. Meanwhile white folk, whipped up by a press that characterised all Mexican youth as dark-skinned hoodlums, became overwhelmingly paranoid and terrified of those who sported the zoot.

Altercations broke out between servicemen and zooters all over California, two of which had a particular effect on the forthcoming riots. On 30th May 1943, a group of sailors and soldiers harassed a group of pachucas (female zooters) in downtown LA, and were battered by the ladies’ male counterparts as a result. Four days later, sailors were again routed by a gang of zooted Chicanos, causing a mob of off-duty LA coppers, who called themselves the Vengeance Squad, to further attack Hispanics on Main Street.

The following day about 200 sailors turned up in East LA and attacked a group of mainly teenage boys, stripped them naked and burned their clothes in a big pile in the street.

And thus the riots began.

As journalist Carey McWilliams wrote: Marching through the streets of downtown Los Angeles, a mob of several thousand soldiers, sailors, and civilians proceeded to beat up every zoot suiter they could find. Pushing its way into the important motion picture theatres, the mob ordered the management to turn on the house lights and then ran up and down the aisles dragging Mexicans out of their seats.

The most heinous violence occurred on 7th June, after one Los Angeles paper printed a guide on how to ‘de-zoot’ a zoot suiter. ‘Grab a zooter. Take off his pants and frock coat and tear them up or burn them,’ it instructed. After Councilman Norris Nelson called the zoot suit ‘a badge of

“The most heinous violence during the zoot suit riots occurred on 7th June, after one Los Angeles newspaper printed a guide on how to ‘de-zoot’ a zoot suiter. ‘Grab a zooter. Take off his pants and frock coat and tear them up or burn them,’ it instructed its readers.

After Councilman Norris Nelson called the zoot suit ‘a badge of hoodlumism’, the LA City Council criminalised the suit within the confines of the city”A de-zooted pachuco taking it in what’s left of his strides

hoodlumism’, the LA City Council criminalised the suit within the confines of the city.

Ironically, in 1943, at the height of the riots, the hugely successful black jazz musical feature films Stormy Weather and Cabin in the Sky were released, with cast members wearing zoot suits, while in the same year America’s favourite comedy duo Laurel and Hardy wore zoots in the film Jitterbugs. The song A Zoot Suit (For My Sunday Gal) was a huge hit in 1942 for several artists. ‘Dig a zoot suit with a reet pleat and a drape shape and a stuff cuff to look sharp enough to see your Sunday gal’ went the lyric. The zoot suit had found a place in mainstream contemporary culture and yet it still caused riots.

The debacle was eventually contained, not on any humanitarian basis but for purely economic reasons. California’s state senators were only concerned about the adverse effects on the relationship between the United States and Mexico. The government declared, ‘The riots might endanger the program of importing Mexican labour to aid in harvesting California crops.’

The Mexican Embassy complained to the State Department, and US Service Chiefs had no choice but to intervene on 7th June, declaring Los Angeles off-limits to all military personnel and confining

sailors and Marines to barracks. By the middle of June the situation had calmed down in LA, but riots erupted elsewhere in California, as well as in Texas, Arizona, Detroit, Harlem and Philadelphia, where two zoot-clad members of Gene Krupa’s charttopping band were given a hiding.

It was during the riots that young zoot suiter and soon-to-be Chicano union activist Cesar Chavez became involved with community politics, which transformed California. Elsewhere, a certain young pimp, ‘Detroit Red’, aka Malcolm Little, embarked on a political journey that ultimately transformed him into the radical black leader Malcolm X. Ultimately, then, the debacle achieved the opposite of what was intended. It did not cleanse the area of mobsters; it actually turned many law-abiding young men on to the gangster life.

The zoot suit exerted considerable influence elsewhere. UK spivs took to wearing outsized suits as proof, like their Mexican counterparts, that they could afford and source the cloth prohibited by cloth restrictions during World War II. Jamaican settlers sported their versions as they alighted from the S.S. Windrush in London’s Tilbury Dock in 1948, thus influencing young Brits.

Today, as clued-up hep cats find the fashions of today rather predictable, the zoot is enjoying another renaissance. I just hope that any would-be Zootie McVouties can find a tailor like Bob of Aldgate and Chris of Kentish Town to produce one of the quality it so rightly deserves. n

Post-WWII, Dior launched his New Look for women, in which everything went big. American male fashion responded with a style that was heavily influenced by the zoot ‒ high-waisted, pleated peg trousers, heavily shouldered jackets with big lapels, wide kipper ties and spearpointcollared shirts ‒ which became almost a uniform for the stars of film noir such as Alan Ladd, Victor Mature and Jack Palance.

“American male fashion responded with a style that was heavily influenced by the zoot – high-waisted, pleated peg trousers, heavily shouldered jackets with big lapels, wide kipper ties and spearpointcollared shirts – which became almost a uniform for the stars of film noir”

Having learned of the checkered history of the zoot suit, we made it our mission to comb the streets of the City of London until we found someone wearing one. It was only when we reached the seamier side of the City, where it bleeds into Whitechapel, that London Boy Lou stepped into the frame, accompanied by his dandizette moll Tiffany Smith.

Lou has only one zoot suit for now; their cost, as we learned on the previous pages, can be prohibitive due to all that extra yardage of fabric. His was made at Lawton Ltd by Kimberley Lawton, a tailor who apprenticed at Huntsman and now makes sharply cut suits for men and women.

Joined by make-up, hair and special effects artist, and erstwhile fashion model, Tiffany Smith, the sharply dressed duo led us into the darker streets and alleys of the area of Whitechapel

where they dwell, drawing us into some of the ghoulish alleys where Jack the Ripper carried out his grim work in Victorian times.

As if summoned by our occult journey, a mysterious stranger joined us outside the Hoop and Grapes on Aldgate High Street, dressed for all the world like a camp version of Jack the Ripper himself. This turned out to be Sean Bailey, who kindly informed us that the Hoop and Grapes was the only pub in the City of London to survive the Great Fire of 1666.

It may have survived the flames, but subsidence is gradually slanting this ancient pub, built in 1593, towards the east of the City, where all the dark stuff occurs.

Reader, we survived this perilous journey, and returned with the photographs herewith displayed. n

TIFFANY WEARS:

Jacket: Vintage 1960s Pendleton

Blouse: Freddies of Pinewood

Skirt and shoes: Vintage 1970s

LOU WEARS: Zoot Suit by Lawton Ltd

Hat: Sierra & South

Shirt: Vintage 1940s Gabardine

Co-Respondent Shoes: Cheaney

LOU WEARS: Zoot Suit by Lawton Ltd

Hat: Sierra & South

Shirt: Vintage 1940s Gabardine

Co-Respondent Shoes: Cheaney

LOU WEARS: Zoot Suit by Lawton Ltd

Shirt: Mark Powell Bespoke

Tie: Vintage 1950s

LOU WEARS: Zoot Suit by Lawton Ltd

Shirt: Mark Powell Bespoke

Tie: Vintage 1950s

SEAN BAILEY WEARS: Jack the Ripper’s camp cousin’s couture

SEAN BAILEY WEARS: Jack the Ripper’s camp cousin’s couture

Gustav Temple delves into the mercurial history of the Homburg, to find that it is a hat revered on both sides of the moral compass

“In the spring, Jeeves, a livelier iris gleams upon the burnished dove.” “So I have been informed, sir.”

“Right ho! Then bring me my whangee, my yellowest shoes, and the old green Homburg. I’m going into the Park to do pastoral dances.”

– P.G. Wodehouse, The Inimitable Jeeves

Picture the scene: 1882, Bad Homburg, an elegant spa town in Prussia (now Germany) where gentlemen pay a visit when feeling slightly under the weather, to enjoy the healing waters and the healing properties of the baccarat tables. One such regular visitor is Edward VII, then the Prince of Wales. After losing a few Reichsmarks at the tables and splashing a few drops of the healing waters on his beard, he is immediately bored and asks his hosts what else there is to do in this kleine ortschaft

“There is a famous hat factory,” one lackey tentatively suggests. To everyone’s great relief, the Prince’s reply is, “Take me there immediately, I simply adore hats.”

The Möckel Hutfabrik, or hat factory, had been founded in 1806 by Johann Georg Möckel, descendant of a hatmaking family for many

“Bertie liked his nephew’s hat, but not that much, so he asked Möckel to fashion him something similar but in grey felt. Always one for starting national trends

spats, the dinner jacket, and undoing the bottom button on one’s waistcoat), Bertie’s new titfer quickly caught on back home, and soon everybody wanted one”

(see

generations. Aided by his technology-loving son, Möckel installed the latest machines in his factory, being the first company in Bad Homburg, in 1856, to install a steam engine. One of their most valued customers was Kaiser Wilhelm II, the Prince of Wales’ nephew. Möckel had made ‘Willy’ a hunting hat of his own design, of pale green felt with a dark headband and a curled, bound brim.

Bertie liked his nephew’s hat, but not that much, so he asked Möckel to fashion him something similar but in grey felt. Always one for starting national trends (see spats, the dinner jacket, and undoing the bottom button on one’s waistcoat), Bertie’s new titfer quickly caught on back home, and soon everybody wanted one. The Homburg gradually overtook the bowler and the topper as the formal hat of choice for English gentlemen. Möckel themselves did alright as well, securing a patent for their new Homburg hat and a Royal Warrant in 1909.

The Homburg was still popular by the 1950s, when US President Dwight Eisenhower broke with tradition at his 1953 inauguration, wearing a black Homburg instead of the traditional top hat (at least he wore any hat at all, unlike one of his successors John F Kennedy). British Prime Minister Anthony Eden, who led the country from 1955 until his resignation in 1957, was already a dapper dresser when he entered office. But his adoption of the Homburg caused such a strong association with him that the hat began to be known, particularly on

Savile Row, as ‘The Eden’. Winston Churchill also favoured the Homburg, but they stuck with Eden as a snappier name.

One would think that this tale sounds perfectly satisfactory, and that the sartorial historians need not trouble themselves for further details. But wait –the Italians, as ever, are getting hot under the collar. Enter Christiano Lobbia (1826-1876), a rather dashing Venetian soldier and Colonel of the Royal Army. On the night of 15th June, 1869, Loggia was

the victim of an unprovoked attack in the street, resulting in a heavy blow to the head and three stab wounds to the chest. At the time of the incident he was wearing a bowler hat, the blow causing a crease to open up in the middle of the crown. On his next session in Parliament, Loggia deliberately wore the very same damaged hat, to draw attention to the ongoing fight against malfeasance and corruption in politics. A Florentine hatter began to make hats based on this battered bowler, calling it ‘la Loggia’ and the new shape quickly caught on.

Since the Florentine hatter remains unknown, there

is no way of verifying this story as the true origin of the Homburg. The hat is still called a Loggia in Italy, and another reference to its origins in times of great violence was its appearance in 1972’s The Godfather, worn by Al Pacino as Michael Corleone.

And the tale of the origins of the Homburg doesn’t end there. There is a very similar hat called a ‘Lord’s Hat’ (at least in the US), with a similar ‘pencil curl’ brim, but with a pinched crown instead of (or sometimes as well as) the Homburg’s gutter crown. The Lord’s hat usually doesn’t have a brim adorned with the same crosgrain as the band. Fans of television series Boardwalk Empire will have noted lead character ‘Nucky’ Thompson, played by Steve Buscemi, wearing a traditional Homburg, while Charles ‘Lucky’ Luciano (played by Vincent Piazza) dons a Lord’s Hat, recognisable by its pinched crown.

What we have learned from all this, dear reader, is that the Homburg is a slippery, elusive hat, at least from a historical perspective. What we do know is that it has been worn by kings, princes, presidents and prime ministers, as well as fictional gangsters and Italian colonels. So when you don your own splendid Homburg, you can delight in the fact that the style has been on a long and arduous journey before reaching your head, and that in itself should give you an air of mystery, intrigue and rakishness that few other hats can bestow. n

Daniel Day-Lewis in 1993’s The Age of Innocence (and the age of the curlier-brimmed Homburg)

Daniel Day-Lewis in 1993’s The Age of Innocence (and the age of the curlier-brimmed Homburg)

www.greyfoxblog.com @greyfoxstyle

It’s remarkable how time flies by. It seems like only yesterday that I was doing homework to my newly bought LP, The Who Live at Leeds, played on my Philips record player. It also seems like only yesterday that a young David Hockney came to visit my school and we were able to chat with him in my class. The same Hockney caused a stir a few months ago by attending an Order of Merit luncheon with King Charles III (how strange it still seems typing that) wearing a loud checked tweed suit and bright yellow Crocs

– or ‘galoshes’ as His Majesty delicately referred to them. Hockney is now aged eighty five and it’s his age that is relevant to the point I’m labouring to make here, namely that advancing years give a confidence, a devil-may-care attitude, that enables a man or woman to dress boldly, even brashly, when meeting a king.

What doubtless caused the press to take such an interest was Hockney’s wearing such unconventional footwear to such a prestigious event (and I suspect that Crocs’ press and PR department