L

ANNIV

E

RS

A RY

SPECIA

ISSUE 100

SUMMER 2019

EXPAND YOUR MIND, REFINE YOUR WARDROBE

E

DI

TIO

N

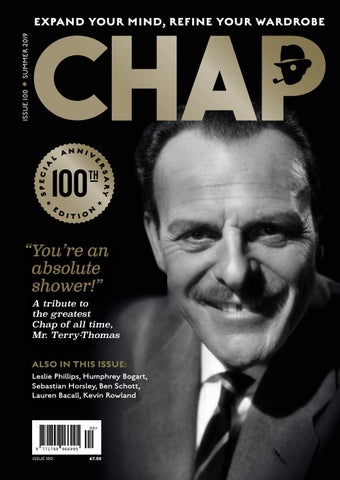

“ You’re an absolute shower!” A tribute to

the greatest Chap of all time, Mr. Terry-Thomas

ALSO IN THIS ISSUE: Leslie Phillips, Humphrey Bogart, Sebastian Horsley, Ben Schott, Lauren Bacall, Kevin Rowland

00>

9 771749 966995

ISSUE 100

£7.50

WWW.CAVANI.CO.UK

Editor: Gustav Temple

Art Director: Rachel Barker

Picture Editor: Theo Salter Circulation Manager: Keiron Jeffries

Designer: Carina Dicks

Sub-Editor: Romilly Clark Subscriptions Manager: Natalie Smith

Contributing Editors: Chris Sullivan, Liam Jefferies, Alexander Larman

CONTRIBUTORS

OLLY SMITH

LIAM JEFFERIES

CHRIS SULLIVAN

GOSBEE & MINNS

ALEXANDER LARMAN

Olly Smith is an awardwinning wine writer and broadcaster. He has been International Wine and Spirits Communicator of the Year, and Drinks Writer of the Year at the 2017 & 2016 Great British Food Awards. He is a regular on Saturday Kitchen and BBC Radio 2. Olly hosts his own drinks podcast www.aglasswith.com

Liam Jefferies is The Chap’s Sartorial Editor, in charge of exploring new brands, trends and rediscoveries of forgotten gentlemanly fashions. Liam’s expert knowledge covers the dark heart of Savile Row to the preppy eccentricities of Ivy Leaguers. You can follow him on Instagram @sartorialchap.

Chris Sullivan is The Chap’s Contributing Editor. He founded and ran Soho’s Wag Club for two decades and is a former GQ style editor who has written for Italian Vogue, The Times, Independent and The FT. He is now Associate Lecturer at Central St Martins School of Art on ‘youth’ style cults and embroidery.

Peter Gosbee is a jeweller, antiques purveyor and keen disciple of the sartorial arts, often to be found at markets, briar in hand and suitcase brimming with treasures. John Minns was brought up in what is commonly known as the rag trade. He cut his sartorial teeth working with ‘the King of Carnaby Street’ John Stephens.

Alexander Larman is The Chap’s Literary Editor. When neither poncing nor pandering for a living, he amuses himself by writing books: biographies of great men (Blazing Star) and examinations of greater women (Byron’s Women). He also writes for the Times, Observer and the Erotic Review, back when it was erotic.

HOLLY ROSE SWINYARD Holly Rose Swinyard is a reporter and fashion experimentalist. In between hosting sci-fi podcasts, Holly writes and speaks about contemporary revolutionary ideas such as gender equality and a post-gender society, along with the equally important topic of clothes and costume.

DAVID EVANS

SUNDAY SWIFT

DARCY SULLIVAN

David Evans is a former lawyer and teacher who founded popular sartorial blog Grey Fox Blog seven years ago. The blog has become very widely read by chaps all over the world, who seek advice on dressing properly and retaining an eye for style when entering the autumn of their lives.

The Dandy Doctor writes on dandyism, gender, popular culture and the gothic. Her writing has appeared in academic journals such as Gothic Studies and in popular books on cult television. Sunday is currently working on a book about fictional dandies in film and television. Twitter: @dandy_lio

Darcy Sullivan writes about comic books, aesthetes and algorithms. His articles have appeared in The Comics Journal, The Wildean and Weird Fiction Review. He is the press officer of the Oscar Wilde Society and the curator of the Facebook pages ‘The Pictures of Dorian Gray’ and ‘I Am Mortdecai’.

Office address The Chap Ltd 69 Winterbourne Close Lewes, East Sussex BN7 1JZ

Advertising Paul Williams paul@thechap.co.uk +353(0)83 1956 999 07031 878565

Subscriptions 01778 392022 thechap@warnersgroup.co.uk

NICK OSTLER Nick Ostler is an Emmywinning and BAFTA-nominated screenwriter of family-friendly entertainment such as Danger Mouse, Shaun the Sheep and the upcoming adaptation of Tove Jansson’s classic Moomin novels, Moominvalley. He is also co-author, with Mark Huckerby, of the British fantasy adventure trilogy Defender of the Realm, published by Scholastic.

E chap@thechap.co.uk W www.thechap.co.uk Twitter @TheChapMag Instagram @TheChapMag FB/TheChapMagazine

Printing: Micropress, Fountain Way, Reydon Business Park, Reydon, Suffolk, IP18 6SZ T: 01502 725800 Distribution: Warners Group Publications, West Street, Bourne, Lincolnshire, PE10 9PH T: 01778 391194

- 20 Years of -

THE CHAP MANIFESTO 1 THOU SHALT ALWAYS WEAR TWEED. No other fabric says so defiantly: I am a man of panache, savoir-faire and devil-may-care, and I will not be served Continental lager beer under any circumstances. 2 THOU SHALT NEVER NOT SMOKE. Health and Safety “executives” and jobsworth medical practitioners keep trying to convince us that smoking is bad for the lungs/heart/skin/eyebrows, but we all know that smoking a bent apple billiard full of rich Cavendish tobacco raises one’s general sense of well-being to levels unimaginable by the aforementioned spoilsports. 3 THOU SHALT ALWAYS BE COURTEOUS TO THE LADIES. A gentleman is never truly seated on an omnibus or railway carriage: he is merely keeping the seat warm for when a lady might need it. Those who take offence at being offered a seat are not really Ladies.

132

4 THOU SHALT NEVER, EVER, WEAR PANTALOONS DE NIMES. When you have progressed beyond fondling girls in the back seats of cinemas, you can stop wearing jeans. 5 THOU SHALT ALWAYS DOFF ONE’S HAT. Alright, so you own a couple of trilbies. Good for you - but it’s hardly going to change the world. Once you start actually lifting them off your head when greeting passers-by, then the revolution will really begin. 6 THOU SHALT NEVER FASTEN THE LOWEST BUTTON ON THY WAISTCOAT. Look, we don’t make the rules, we simply try to keep them going. This one dates back to Edward VII, sufficient reason in itself to observe it. 7 THOU SHALT ALWAYS SPEAK PROPERLY. It’s really quite simple: instead of saying “Yo, wassup?”, say “How do you do?” 8 THOU SHALT NEVER WEAR PLIMSOLLS WHEN NOT DOING SPORT. Nor even when doing sport. Which you shouldn’t be doing anyway. Except cricket. 9 THOU SHALT ALWAYS WORSHIP AT THE TROUSER PRESS. At the end of each day, your trousers should be placed in one of Mr. Corby’s magical contraptions, and by the next morning your creases will be so sharp that they will start a riot on the high street. 10 THOU SHALT CULTIVATE INTERESTING FACIAL HAIR. By interesting we mean moustaches, or beards with a moustache attached.

34

96

CONTENTS 8 AM I CHAP?

A look back at the successes and failures of this publication’s attempt to right the world’s sartorial wrongs

12 H ISTORY OF THE CHAP

The tables are turned on Gustav Temple, as he submits himself to an interview about the founding of this publication

FEATURES 22 TERRY-THOMAS

An in-depth look at the man behind the gap, with some insights and never-seen family photographs from Terry-Thomas’s niece

32 T HE FILMS OF TERRY-THOMAS

We pick the top five films starring T-T and explain why each one of them should feature in a Chap televisual library

34 L ESLIE PHILLIPS INTERVIEW

Chris Sullivan meets the debonair actor at his London home to look back at the suave one’s 100-film career

SPECIAL ANNIVERSARY EDITION

•

SUMMER 2019

Cover photograph: © Rex/Shutterstock

ISSUE 100

SARTORIAL FEATURES

LONGER FEATURES

44 CHAP PHOTO PORTRAITS

106 S EBASTIAN HORSLEY

We photographed some chaps and chapettes whose sartorial élan has helped define this publication’s style

52 THE HISTORY OF SAVILE ROW

Chris Sullivan takes a meditative stroll along the checkered history of the home of bespoke tailoring

60 S OUL BOY SOCCER

Dermot Kavanagh on Laurie Cunningham, the first black player to play for England, who also cut a stylish rug in 40s threads

Alexander Larman’s tribute to the last of the true dandies

116 T HE 100 BEST THINGS ABOUT DRINKING

Olly Smith lists one libatory joy for every issue of this publication

122 B IRDING

Nick Ostler on how the avian species pierced his soul as a child

126 D ANDIZETTE

The style, talent and seductive allure of Lauren Bacall

66 S ADDLE SHOES

132 CHAP TO THE FUTURE

68 A SARTORIAL PRIMER

REVIEWS

One chap’s quest to locate a pair of these surprisingly elusive 1950s suede two-tone shoes

Liam Jefferies recaps 99 issues-worth of sartorial advice, to see if readers have been paying attention

74 H UMPHREY BOGART

Nick Guzan reminds us why Bogie defined 1930s menswear by sartorially surpassing all other actors of his era

82 G REY FOX COLUMN

David Evans of www.greyfoxblog.com gives salient tips for living the analogue life by rejecting the digital fripperies of our age

88 S TYLE TRIBES

Olivia Bullock on Future Nostalgia and how street fashions nearly always look to the past before creating the future

94 T HE STRAW BOATER

Matt Deckard advocates the return of this oft-maligned item of headwear to the wardrobe of a gentleman

96 C HAP PORTRAITS PART TWO

Our second selection of notable chaps and chapettes who cut the sartorial mustard

The enduring appeal in popular culture of this style we call Chap

138 A UTHOR INTERVIEW

Miscellanist and Wodehouse homagiste Ben Schott

138 B OOK REVIEWS

Books about Wallis Simpson and Auberon Waugh

146 J .P. DONLEAVY

Noel Shine met the legendary author at his home in rural Ireland

152 T RAVEL: PARIS

Chris Sullivan discovers the city’s seedy and glamorous underbelly

160 R ESTAURANT REVIEW

A visit to Kaspars Seafood Restaurant at the Savoy, London

162 P EACOCKS & MAGPIES

Gosbee and Minns smoke their pipes without fear of prosecution

164 A POCALYPSE CHIC

How future humans will be dressing for the next 100 issues

170 CROSSWORD

SEND PHOTOS OF YOURSELF AND OTHER BUDDING CHAPS AND CHAPETTES TO CHAP@THECHAP.CO.UK FOR INCLUSION IN THE NEXT ISSUE

As a change from publishing acerbic comments on readers’ submissions to this column, for the 100th edition we are sharing, instead, some success stories from the archives. Chaps who, either by following our advice or through their own determination, overcame early sartorial obstacles to find their true inner Chap or Chapette.

Mr. Guy Fantome sent us a photograph of himself in 1970 with a Riley RMA, looking quite frankly like he should be driving it, or cleaning it, for someone else.

Poor old Simon Doughty was lost in a sea of serge de Nîmes when he started reading The Chap, finding an alarming consistency of hostility towards his raiment every time he sent us his photograph.

Mr. Fantome’s more recent photograph, with an Alvis TD21, showed that, as his taste in cars has matured, so his wardrobe has vastly improved.

Doughty has since seen the error of his ways and taken to wearing sturdier fabrics such as linen, wool and tweed. We still, however, expect his occasional cheeky attempt to slip some denim under our noses in the future.

When Lou Christou first sent us his photo, he had such difficulty in finding the right clothing that he took the bold decision to have a cravat tattooed on his neck.

When Hiroki Ohashi of Tokyo began his frequent correspondence with us, it wasn’t quite clear who was mocking whom.

Thankfully, by reading the Chap, Lou discovered that such tattoos can be easily purchased at menswear emporia. He does, however, still have the advantage of being well-dressed even when swimming.

By the time of his last submission, this was abundantly clear.

Oh alright then. In the words of Beau Brummell, these are some of our failures.

Some fellows went to extraordinary lengths to find their inner chap (and indeed each other’s), but it somehow eluded them and they continued wearing pantaloons de NÎmes and pretending to smoke pipes.

These rum coves couldn’t even find their outer chap, never mind their inner chap. This photo was sent to us in 2012, but apparently they are still standing at that bar, a light covering of dust on their plastic pipes and plastic moustaches. Meanwhile, our work continues.

This looks like exactly the same group of men, but surprisingly is a completely different set of humans in another part of the world. Here they are again, with the addition of two more to their macabre flock. The Chap takes full responsibility and apologises for any inconvenience caused.

Even we considered this a rather tasteless portrait when we received it in 2012. Whereas today buttoning the bottom button on one’s jacket is more acceptable.

“I had a Chapthemed stag do,” quoth Richard Walden in 2008. A decade later, we stand by our ogiginal response: No you didn’t.

Here are the shotgunwielding fellows from above again, but in their real clothes.

Since receiving this photograph in 2006, the seated gentleman has now become the butler to the standing gentleman, on account of the latter’s possession of superior facial hair.

Interview

THE HISTORY OF THE CHAP Dennis Merry turns the tables on founder of the Chap Gustav Temple, interviewing the habitual interviewer to discover the origins and growth of the UK’s longest-running gentlemen’s quarterly

S

one of those photocopying joints like KallKwik or ProntoPrint, I can’t remember which. It was designed in QuarkXPress, copied and stapled on A4 paper, because the original magazine was A5, and they ran off a hundred photocopies, and then a hundred colour copies of the cover, which we upgraded to card. It was pretty poor quality, but it was a start. We thought of it more as a sort of Samizdat dada pamphlet than a magazine.

o, The Chap is twenty years old, and here we are with the 100th edition; congratulations. When you look at this edition and compare it with the very first edition, how would you describe the differences? How has the Chap evolved? Well, it’s bigger and it’s in colour. The very first edition, published in February 1999, was only 36 pages; it was printed in black and white, and it was quite naïve as a magazine, really. Instead of having advertising or some kind of filler, we actually left four pages blank, because we didn’t know what to put on them. Back then I had a partner, Vic Darkwood, with whom I founded The Chap, and it was fortunate that we had similar skills, so we kind of did half each, and you couldn’t really tell which was which – specially as we used a series of bizarre noms de plume. The thing is, there were two first editions. The real first edition was printed at

“People used to point and shout at us when we strolled around in vintage tweed suits smoking pipes. It was shocking to them... – an anarcho-dandyist anachronism!”

13

for adverts for yachts and watches. Meanwhile, men and women are dressing much better, in certain quarters, than they were when we founded The Chap. People used to point and shout at us when we strolled around in vintage tweed suits smoking pipes. It was shocking to them, but not entirely as something new, more as an anachronism – an anarcho-dandyist anachronism!

So somewhere in the world there are a hundred copies of the first edition, made at ProntoPrint, which are true collector’s items! Yes, but sadly I don’t have a copy myself. Anyway, we sent a sheaf of those to various journalists on a wing and a prayer, just to see what happened and, surprisingly, we got some coverage in the media. We got invited on to a few radio programmes and were interviewed by a few broadsheets. Then, the day after we were featured in the Daily Telegraph, we had a sack full of letters with cheques and subscriptions, which came into a P.O. Box number we’d fortunately had the foresight to set up. So we had all these subscriptions to fulfil but no magazines, so we had a proper printer run off more copies on professional magazine paper. I think we spent about a thousand pounds and had a thousand copies printed of the exact same edition. But going back to your original question of how is it different. Now it’s a 164-page magazine, professionally designed and printed, with a substantial following. But it hasn’t strayed too far from its original ethos and that spirit of anarchodandyism, with a satirical element. We do have more advertising now, but compared to something like GQ , the ratio of ads to content is still tiny. I suppose the main difference between now and then is that we were a bit like a voice in the wilderness back then. There was no one else out there doing anything like this; no moustaches, no-one under the age of 60 wearing tweed, and nobody championing dandy culture with a certain satirical slant. Yes, there are more high-end men’s magazines touching on dandyism, but most of them seem to be vehicles

What gave you the idea for the Chap magazine in the first place? The idea really all came out of a conversation in the pub with Vic. I’d known Vic for about five years; he is an artist and we met through artistic circles in London and discovered we had a lot of interests in common. We shared an affinity for Chap-type values, and drinking of course, and somewhere in those sessions of chatting and drinking came this idea, but I don’t quite remember why, of publishing a magazine. Both of us were interested in things like old comic books and old etiquette manuals, and characters like Vivian Stanshall, Beau Brummell and Terry-Thomas. We were having this conversation in a pub in Camberwell in London one night, and somehow got to talking about starting a magazine and what kind of thing it would be. We started sketching it out and very soon

14

we had the contents. So we went away and worked on writing different bits. Being an artist, Vic did the illustrations too, although lots of the images we just scanned from our huge collection of comics and magazines from the 1940s and 1950s. A number of the original covers were old knitting patterns. So that’s how it all began, but I’m still not clear why we decided to do it! The Chap Manifesto obviously has ‘tonguein-cheek’ overtones, but what are the core elements which you feel are most important and relevant to modern life? Well, all of them, really. Those ten points in the front of every copy of the magazine didn’t actually go in until about 2004. Obviously, as an idea and a certain take on life, it was all there in the 2002 book of the same name. I suppose the only one we have slightly moved on from is the beard. Originally, we were in favour of moustaches and definitely anti-beard, because in 1999 beards were for old fuddy-duddies, or represented a certain hippy-ish scruffiness and a kind of unkempt, undisciplined approach; there was no grooming to speak of. The moustache has always seemed to me to be something of a bold statement, but the beard was kind of a lazy statement. Since then we’ve realised that any facial hair is good, because it’s flamboyant. I’ve come across so many chaps over the years who were sound fellows but wore a beard that I ended up thinking, we’ve got to give beards a chance. So, this begs the inevitable question: why does the founding father of The Chap not himself sport a moustache? Ah, of course; good question. I always thought that for every chap there is a moustache. But I have tried moustaches; I’ve tried them all, but none of them suited me, and I’ve come to see that it’s just not true; there isn’t a moustache for every man. And I have an early photograph to prove it. Have you always been interested in clothes? Have you always dressed well?

15

Yes, I have always been interested in clothes, but no, I haven’t always dressed well. I was in a rock band in the 1980s and I suppose my outfits for that were not a million miles from Chap, in that I used to wear Victorian frock coats and top hats; it was all a bit Artful Dodger. We were called the Jackals of Freshkid and, strangely enough, one of our tracks has just been released on a compilation album on Cherry Red Records. In our band, I didn’t follow any of the dress codes which were around; I went my own way and dressed in a kind of rock ‘n’ roll version of how I dress now. I’m not one of those chaps that wore a three-piece suit from the age of twelve and never looked back. But I suppose there’s always been a bit of a Chap thread of running through things. I don’t think of myself as a dandy, but dandies have always been my inspiration. So I’ve always looked up to people like Bunny Roger and Oscar Wilde, and of course the ultimate Chap himself, Terry-Thomas. My definition of a dandy is quite broad and includes rock ‘n’ roll dandies like Marc Bolan, David Bowie and Bryan Ferry. So, where did this love of Dandyism come from, was it always there? I was never cut out to be a rock singer. While I was in the band, I was reading a lot of Albert Camus, Andre Breton, Henry Miller and Baudelaire, and somewhere in all that came the idea of Dandyism. I suppose Baudelaire was the key, you know, wandering around the streets of Paris finding yourself, being a flaneur. So, in 1986, when the band broke up and I wasn’t sure what I wanted to do, I thought, ‘Where

The Timeline

Issue no.1 of The Chap is published. Initial attempts at self-distribution, in a Triumph Vitesse around London, receive a mixed reception. One doyen of a comic shop in Camden looks at it and says, “What the bejesus is this?” FEBRUARY 1999

The Chap’s first shindig takes place on HMS President moored on the Thames. Entertainment includes a snake charmer and a man reciting dada poetry through a megaphone.

Chaps, attired as Edwardian mountaineers, attempt to scale the north face of ‘Embankment’ by Rachel Whiteread at Tate Modern, a 40-foot pile of resin casts of cardboard boxes. They are successful but escorted from the premises.

NOVEMBER 2002

APRIL 2005

OCTOBER 2001

OCTOBER 2003

JULY 2005

Publication of The Chap Manifesto by Fourth Estate. The title is followed by The Chap Almanac and Around the World in 80 Martinis.

The Chap’s first protest against vulgarity, Civilise the City, takes place in London. Protesters enter McDonald’s and order devilled kidneys, before being escorted from the premises.

The inaugural Chap Olympiad takes place in Regent’s Park, London. 25 competitors alarm tourists by performing Trouser Gymnastics and Raconteur’s Relay.

The key points in the founding, development and manifesto-spreading exercises of this 20-year-old journal for the modern gentleman

The Chap expands to a larger A4 format and nearly goes bankrupt. The publication is saved by its readers in a fundraising campaign and quietly goes back to its former size.

The Chap’s second major protest is against Abercrombie & Fitch opening a store on Savile Row. The slogan is ‘Give Three-Piece a Chance’. They didn’t.

After years of failed attempts, The Chap finally secures an interview with Fenella Fielding, which turns out to be her last full published interview before she dies in 2018.

DECEMBER 2008

APRIL 2012

JUNE 2016

JULY 2012

MAY 2017

The Chap recreates the famous tennis match in School For Scoundrels at the 1960 film’s original location, Corus Hotel Elstree.

The Chap mistakenly agrees to field a mini version of The Chap Olympiad at the Olympic Games in London. Hardly anyone shows any interest except Linford Christie, who asks us where the toilets are.

The Chap relaunches as a quarterly (which it was in the first place, before becoming bi-monthly in 2005), redesigns all its logos and graphics and doubles in size. There are a few letters from disgruntled subscribers.

ISSUE 92

•

SUMMER 2017

APRIL 2008

17 17

92>

9 771749 966070

should a 21-year-old man go to find himself ?’ The answer of course was, and still is, Paris. I toyed with the idea of arriving in Paris in a frock coat and top hat, but then decided against it. So I started to wear black ill-fitting suits – they didn’t fit because I was too skinny and they came from charity shops. I thought a beret would be a step too far, so I wore trilbies and Fedoras. I went for that existentialist kind of look because that was the literature I was influenced by.

It’s ironic that those 1940s threads then came into fashion in the early 2010s, and now you can buy a Harris Tweed jacket in Primark! Also ironic was that, during our Civilise the City protest in 2004, we marched into a Nike store and demanded to see the head cutter. So in a way, they did listen to us, or at least the fashion industry as a whole did. Nike just called security. Do you hold to the old adage that ‘Clothes maketh the man?’ What I’ve discovered through reading about and meeting dandies is that the clothes are just an exterior expression of the inner self. I’ve seen plenty of people dressed up in all the right gear, dressing the part, but they don’t look authentic. It’s like the clothes are wearing them. So of course we have to wear nice clothes, but they have to be the right nice clothes for your personality and your beliefs. I do believe in all the rules, brown in town, black tie, white tie etc. but it’s important that your clothes are an expression of who you are as an individual. Something that appealed to us from the very beginning was that it’s all very well fussing over which correct tie to wear etc, but there was also something inherently comical about that too. Most of the other men’s fashion magazines take dressing so seriously; we wanted to put more raffishness back into fashion.

So when did tweed and pipes first make their appearance in your wardrobe? One of the reasons we started The Chap was to answer the question of how to dress after middle age. Vic and I were both in our mid-30s and conscious that men who ignored their age and carried on regardless in the same style they’d worn as youths frankly didn’t cut the mustard. No-one takes a balding mod or an overweight Goth very seriously. But at the same time, I felt quite passionately, and still do, that men should not be obliged to abandon all sense of personal style as soon as they hit 40. The answer seemed to be to find a new flamboyance – one that had nothing to do with whatever the youth were wearing. So we looked back to the 1940s, because the clothes from that period looked totally out of kilter with the times – remember this was 1999 – yet kind of edgy and anarchic. And the palette, once you started looking properly, was actually huge – much broader than whether to wear a blue hoodie or a grey one. This kind of clobber will easily take me all the way to retirement, I mused, and will provide ample opportunity for flair and individual expression. More so, if anything, than continuing to dress like a teenager and finding that the sizes just don’t scale up to middle-age spread.

How long has the Chap Olympiad been running and what gave you the idea? It all began in 2005, in Regent’s Park, London. There were 25 people and several bottles of gin and it was really just a bit of a jolly in the park. But it had actually started before that, with an article written by Torquil Arbuthnot and Nathaniel Slipper, who came up with

18

the idea of an Olympic Games in a one-off article, looking at what sports would be played by Chaps. The same year we published it, I said ‘Well, let’s try it out and see if these silly suggestions work in real life.’ And of course they did. So we did it and it grew, so the following year we sought a bigger venue in Regent’s Park. Then we began to put on an organized event with tickets and whatnot in Bedford Square Gardens, also in London. So it all started from that one article.

“Most of the other men’s fashion magazines take dressing so seriously; we wanted to put more raffishness back into fashion” Now that the Chap has crossed the Pond and is breaking into the American market, do you see it continuing to grow in its reach? Are there plans to expand into other markets and cultures? Yes, although it’s difficult to market outside of GMT, added to the fact that a different issue to the one in Britain is on the shelves in America for two months. The only two other places I think it would have a chance are Australia and Japan. The trouble is that the language is so idiosyncratic; English is so subtle, with lots of nuances and historical idioms that aren’t immediately obvious to non-Brits. So basically, there are no specific plans to take it elsewhere, but you’re open to the possibility if the right situation arose? Yes, and it is interesting that there are one or two countries where you wouldn’t necessarily expect the

19

Chap to develop a following. For instance, the biggest EU circulation for the Chap outside of the UK is in Germany, and they’re not Ex-pats, they’re Germans. The first offer we had for a translation of The Chap Manifesto into another language, was into Portuguese. So there are pockets of Chappism everywhere. Looking ahead to the next twenty years, what do you see for ‘Chapdom’? Do you think there will still be a place for the Chap and its values in twenty years’ time? Well, in twenty years’ time I’ll be 74, and whether I’ll be inclined to get up off my divan to put together a magazine is unlikely. But in 20 years The Chap has gone from the sidelines as a counter-cultural ‘voice in the wilderness’ to being associated with a mainstream fashion movement. It’s survived being in and out of fashion; it’s been on the sidelines and it’s had its resurgences; imitators have come and gone, but it’s survived. We’ve kept calm and carried on. Its ethos and its message are so clear and distinct, and so appealing to those who subscribe to the idea. There will always be chaps; men who want to grow moustaches and smoke pipes and look back to the old days, and what else are they going to read? Who yer gonna call? Exactly! There’s nothing else quite like it; there’s nowhere else that they can get all that information in one place. From the word go, I decided I would try never to do the obvious thing and always look to be innovative with the idea. Our mantra from the very beginning was never to publish a feature about the Bluebell Girls, and, at least with that particular rule, we’ve remained true. n

LEATHERBRITCHES BREWERY

A

small traditional craft brewery first established at the Bentley Brook Inn in 1993, now situated in Smisby on the Derbyshire/Leicestershire borders. Before the advent of science and technology, ale conners used to spill beer on the wooden benches and then sit on it while they had their snap (packed lunch) in order to determine the gravity of beers for duty payable to the king. Judging by how hard they stuck to the seat, the strength of the beer could be estimated. Only leather britches were able to withstand the wear and tear of the job, and this is where Leatherbritches Brewery takes its name. The beers brewed by Leatherbritches are caskconditioned ales made from malted barley, English hops, Nottingham yeast and pure Derbyshire water. No artificial additives are included. The new range of ales celebrates the cads and bounders of history, including one named after Terry-Thomas called, appropriately enough, The Bounder. This pale golden ale with an ABV of 3.8 has been described as hoppy and citrusy, with subtle notes of grapefruit and spice aroma. Others in the range include Cad and Scoundrel. www.leatherbritches.co.uk n

Features Terry-Thomas (p22)

•

Interview with Leslie Phillips (p34) 21

Undeterred by this inauspicious beginning, Thomas wore the suede shoes to work anyway, paired with a pork pie hat and doublebreasted suit with a clove carnation buttonhole – a lapel decoration he would apply daily, fresh from the florist, for the rest of his life

22

Chap Icon

TERRY-THOMAS Gustav Temple pays tribute to this publication’s most inspiring figure for the last 20 years All photographs courtesy of Penny Robinson

Bounder! By Graham McCann is gratefully acknowledged for research

“The last stronghold of gracious living in a world gone mad. MAD!”

I

Charles Firbank (Terry-Thomas) in How to Murder Your Wife

t would be understandable if The Chap had several icons, elements of whom all contributed collectively to the ethos of the publication; perhaps a Frankenstein’s monster composed of Leslie Phillip’s raffishness, Cary Grant’s sartorial elegance, and Peter O’Toole’s drinking habits. But, while those chaps all played a huge part in forming the basis of our credo, this composite fantasy figure plays second fiddle to one particular individual who single-handedly summed up everything we hold dear. That man is, of course, Terry-Thomas. There is no question that Thomas Terry Hoar Stevens is the sine qua non, the ne plus ultra, in fact nothing short of the spiritual godhead of this publication. There is no need to explain why, but the 100th edition is the perfect place in which to delve more deeply into the life of the actor and look beyond the public image we know so well: the bounder, the moustachioed entertainer, the bon vivant, the caddish roué who charmed his gap-toothed way through more than 80 films, in a succession of embroidered waistcoats (one of them made from mink), Savile Row suits, bowler hats, whangee cigarette holders and monocles. Terry-Thomas was born Thomas Terry Hoar Stevens in North Finchley, London, on 10th July 1911, the fourth son of five children, with older brothers Jack, Richard and William, followed by a

sister Mary in 1915. His father, Ernest, a welldressed but definitely not dandyish fellow whom T-T described as ‘always smelling like a first-class railway carriage’, worked in the meat trade at Smithfield Market. It cannot be denied that there was very little in the background of Thomas Stevens that indicated a life in showbusiness. He escaped the drab surroundings of North Finchley to the cinemas and theatres of London, inspired by actors such as Douglas Fairbanks Jr and Owen Nares, and, aged 10, already dreamed of one day owning a pair of suede shoes like the ones worn by Gerald du Maurier. It was only once enrolled at Ardingly College in West Sussex that Thomas Stevens first showed signs of evolving into Terry-Thomas. Surrounded by plummy accents more like the one he was developing himself, he made his mark by playing the clown and earned himself the sobriquet ‘the funny chap with the gift of the gap.’ By the time he left Ardingly, the 17-year old Thomas Stevens already felt he was destined for a glamorous life that involved the wearing of suede shoes, at the very least. Instead he was offered a job by his father as a junior transport clerk at the Union Cold Storage Company in Smithfield Market. Undeterred by this inauspicious beginning, Thomas wore the suede shoes to work anyway, paired with a pork pie hat and double-breasted suit with a clove carnation

23

buttonhole – a lapel decoration he would apply daily, fresh from the florist, for the rest of his life. He got through the dull routine of work by entertaining his colleagues with made-up characters and landed himself a part in the firm’s amateur dramatic society. This led to a few roles in minor productions at small theatres, and then into work as a film extra at Pinewood Studios. It was mutually agreed that Thomas Stevens was not cut out to sell meat, and he drifted into another job as an electrical engineer. On the side, he was still performing, strumming the ukulele in the Rhythm Maniacs and trying his hand at professional ballroom dancing at the Cricklewood Palais de Danse. His dancing led him into his first double act, and his first marriage, to the South African ballet dancer Pat Patlanski. At the beginning of the Second World War, Terry Thomas (he didn’t add the hyphen until 1947) and Pat were signed up to the newly formed ENSA (Entertainments National Service Association). His polished performances and ability to organise earned him a role as head of ENSA’s cabaret section. Terry was called up in 1942 and arrived at the training depot of the Royal Corps of Signals in a silver hire car laden with far too much luggage, including a Spanish guitar. His entrée into barracks did not go well; asked for his number by his CO, Terry Thomas replied, “Kensington 0736”. However, Private Terry knuckled down and earned himself the rank of corporal, before having his hopes dashed of earning a commission due to a hearing problem, incurred during his days as a film extra. Instead he was offered a part in a new Services touring revue called Stars in Battledress. This was where Terry Thomas developed a routine that was to become his calling card and eventually lead to a successful career in the early days of television. Inspired by the true story of newsreader Bruce Belfrage, who had continued broadcasting on the BBC while Broadcasting House was being bombed, ‘Technical Hitch’ had Terry Thomas attempting to orally recreate a series of records that were either missing or accidentally broken, the impressions ranging from Al Jolson to the entire Luton Girls Choir. How Do You View? was first broadcast to the television-viewing nation in autumn 1949. It is still regarded as the first proper comedy series on British television and was seen as groundbreaking, even without much competition. Terry Thomas, as the show’s star, creator and co-writer, had a huge

hand in making it fresh, original and exploiting the potential of the new medium. The show was ostensibly broadcast from his character’s dissolute man-about-town’s bachelor pad, and Terry was adept at using the intimate medium to its fullest capacity. His intention was for the viewers at home to feel they had a seat in the front row at a variety theatre. Well received by the public and reviewers, the initial 20-minute fortnightly shows were increased to 40 minutes and ran for four series, bringing in stars of the day such as Diana Dors. Terry knew he had arrived when he was named Best Dressed Man of the year in 1953 by the prestigious magazine Tailor and Cutter.

“Carlton-Browne of the F.O. was the only upper-class character I ever played. I based him on someone I knew who was described as ‘rubble from the nostrils upwards’. If you asked him what day came after Wednesday, he would answer, hoping he got it right, ‘Thursday?” With his name established on TV, the natural next step for the new household name of TerryThomas was cinema. His first major role was in The Boulting Brothers’ Private’s Progress in 1956, in which he showcased what was to become one of his catchphrases, “You’re an absolute shower!” In a television interview from 1976 he explained the origin of this phrase: “In America they still go around saying ‘You’re an absolute shard’. They don’t know what ‘shower’ means. It’s short for ‘shower of…’ and you fill in the last word. Used it in the Army.” Private’s Progress led to a fruitful period with the Boulting Brothers (see film guide, below) culminating in T-T’s finest role, at least for Chaps, of his entire career – Raymond Delaunay in 1960’s School For Scoundrels. Despite playing the second lead, Terry-Thomas is clearly the star of the film and his character encapsulates an incorrigible but charming bounder in a flawless performance. Based on the One-Upmanship novels of the 1940s by Stephen Potter, the film was beset by background

24

Terry-Thomas with his first wife Pat Patlanski

TERRY-THOMAS ON CLASS Terry-Thomas himself was always keen to dispel the notion that he only ever played the upperclass twit. In an interview on television’s Film Talk from 1976, he said, “Carlton-Browne of the F.O. was the only upper-class character I ever played, if one wishes to be pedantic about it. I based him on someone I knew who was described as ‘rubble from the nostrils upwards’. If you asked him what day came after Wednesday, he would answer, hoping he got it right, ‘Thursday?’

All the other characters were lower middleclass pretending to be upper middle-class. The same type of chap – motor-car salesman. If there are any motor-car salesmen watching this, I could change it to something else like… electrical engineer.” This particular profession had not been plucked randomly from the air – Terry-Thomas’ second job, after his inauspicious start in the meat trade, was precisely that of an electrical engineer.

Kramer noted, during the vast production of It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad World, that Terry, as the only British actor among a huge cast that included Spencer Tracy, Phil Silvers, Mickey Rooney and Milton Berle, was the least inclined of the whole cast to on-set displays of ego and attention-seeking. After several successful years in Hollywood, Terry crossed back over the Ocean (always travelling first class, of course, with his own personal hamper full of caviar, champagne, quail’s eggs, perhaps a couple of chops that he’d politely ask the stewardess to cook for him en route) to concentrate on what he’d always been very good at – spending money. He bought some racehorses, more cars, more clothes (his waistcoats alone numbered 150), upgraded his London home and bought a plot of land on Ibiza, where he had a vast house, Can Talaias, built to his own design. He married his second wife Belinda, 25 years his junior, and sired two boys, Tiger and Cushan (Cushan now runs T-T’s former villa on Ibiza as a hotel). What could a Balearic island in the late 1960s provide but endless parties, nude bathing and morning Bloody Marys? The man who first mooted the idea of moving to Ibiza to T-T was louche actor Denholm Elliot, who had already built his own place in the sun in the hills above Ibiza Town. Like all expat congregations, the British acting community, frequently bolstered by visits from people like Leslie Phillips and Diana Rigg (who never wore a bathing suit), created their own concoction of local and home culture, serving paella followed by apple crumble. Terry’s 1970s appearance on the debut episode of brand-new television chat show Parkinson marked a new phase of his career as the delightful raconteur. This required just as hectic a schedule as his acting career had, and it was during an appearance at Sydney’s Metro Theatre that a doctor first spotted the early signs of Parkinson’s Disease, noting that T-T’s left hand trembled slightly. Terry’s response to being informed that the disease would get progressively worse was to throw himself into an intense bout of film roles in locations all over the world. These included his appearance in 1972’s Vault of Horror, an anthology by Amicus Films, and voicing Dr. Hiss in Walt Disney’s 1973 Robin Hood. He was wise to choose such projects over the new genre of smutty movies coming out of Britain at that time; the tail-end of the Carry On genre and its lower-budget siblings the Confessions of… series. The closest T-T came

problems from the start, none of which detract from the final version. In an odd reflection of the Potter books, which give a chap a guide always to being ‘one-up’ on any rivals, co-star Alistair Sim made the eccentric announcement at the start of filming that he didn’t want to touch any props. Any scenes involving his touching anything at all had to be reshot to accommodate this peculiar request. The film’s original director Robert Hamer was a recovering alcoholic who fell off the wagon half way during production, and was replaced by the uncredited Cyril Frankel. With the golden age of British 1950s film drawing to a close, Terry made the shrewd decision to cross the Atlantic and coast on his success. He was welcomed with open arms in Hollywood and landed plenty of roles in his first colour films, including How To Murder Your Wife with Jack Lemmon – who incidentally was hugely complimentary about T-T’s generosity both as a performer and friend. Terry was quickly absorbed into Hollywood’s glamorous inner circle, befriending Groucho Marx, Dean Martin, Cary Grant and Liberace, among others. It wasn’t long, however, before T-T tired of the heat and snobbery of California; his response to being upbraided for inviting humble cameramen to his celebrity parties was to fly a Union Flag on his house and import a Bentley Continental from England at vast expense. Ironically, it was his very Britishness that was so in demand; director Stanley

Terry-Thomas being questioned for parking his drophead Jaguar on the kerb during the filming of School for Scoundrels in 1960

26

Terry-Thomas’s relations with his female costars was never anything less than outrageously flirty

to this cinematic nadir was a reunion with his old chum Leslie Phillips in Spanish Fly (1975), on whose set Phillips reported Terry not being his usual garrulous self. The Terry-Thomas family kept his progressive illness out of the public eye until 1977, when, with so many rumours abound, it was decided to make a formal announcement. He rarely appeared in public after that, bar the occasional advertisement to fund his increasing medical bills. A huge disappointment to him as an actor was having to turn down a role in Derek Jarman’s The Tempest. Terry-Thomas as Prospero under the distinctive hand of Jarman would have provided a perfect swansong for T-T. Terry’s only television appearance during the 1980s was in a series of BBC documentaries, The Human Brain. He effectively became the public face of Parkinson’s, raising considerable amounts of money for medical research by his appeal on the programmes. The dream house on Ibiza was sold to pay more medical bills, and Terry-Thomas’s next appearance in the media proved to be his most tragic and moving. In 1988 the Daily Mirror ran a story entitled ‘Comic Terry’s Life of Poverty’, reporting how the comic legend and his wife Belinda were living in a three-room house in South-West London in dire poverty – so impecunious that the couple couldn’t even afford an electric kettle and were boiling water in a pan to make tea. Terry sat blank and lifeless in an armchair, warmed by the single bar of an electric

27

fire. One of the readers of that article was writer and broadcaster Richard Hope-Hawkins, who, as a lifelong fan of Terry-Thomas, wrote to ask whether he could pay his hero a visit. The emotional effect of this visit resulted in Hope-Hawkins going to his friends in showbusiness to see whether any assistance could be given to the ailing and destitute Terry-Thomas. Once word got around, anyone who was anyone was putting themselves forward to appear in a huge benefit concert staged at the Drury Lane Theatre. With Michael Caine as chairman, the appeal attracted stars from both sides of the Atlantic. The show took place on 9th April 1989 before an audience of 2,500 and included spots from Eartha Kitt, Ian Carmichael, Terry’s second cousin Richard Briers, Lionel Jeffries, Harry Secombe, Ronnie Corbett and Barbara Windsor. The total cast numbered 150, including recorded appearances from some of T-T’s stateside acting chums. It raised £75,000, with an additional £23,000 raised via a television tribute. Terry-Thomas was moved to a nursing home in Godalming, Surrey, where he lived in relative comfort until 8th January 1990. His funeral took place on 17th January, with the theme from Those Magnificent Men in Their Flying Machines played while the coffin was carried, bearing a white cushion with a monocle, a cigarette holder and a clove carnation. Even in death, Terry-Thomas had not missed a single day without wearing a fresh clove carnation. n

Interview

TALES OF TERRY Gustav Temple meets Terry-Thomas's niece to find out what it was like growing up in the shadow of Britain's most loveable bounder

P

enny Robinson (83) is the niece of TerryThomas. Her father was Terry’s older brother Richard, who was killed in a motorcycle accident during the Second World War. Gustav Temple discussed the various ways that Terry-Thomas – whom she always refers to as ‘Tom’ – impacted on her life. She also wished to dispel a few inaccuracies about her uncle portrayed in the published chronicles of his life.

that you see on the telly was him, as a person. He was always the same; he spoke beautifully, he was very generous. But there is a perceived difference between his accent and the rest of his family, isn’t there? Well, my father spoke beautifully – they all did. And Jack, Tom’s eldest brother, was wealthy; he owned a huge butter factory. Tom’s mother, my grandmother, lived near us in Combe Martin in Devon.

Tell us about your family relationship to Terry-Thomas. Tom was my father’s brother. There were four brothers – Jack, Richard, Tom (T-T), Bill, and a sister, Mary.

Terry-Thomas is always described in biographies as ‘the son of a market trader’. Well, I don’t know about ‘market trader’ – they had a huge shop in Covent Garden! They tried to rubbish him, in a way, which the family found really annoying. “Oh, he wasn’t really like that at all.” Yes he was!

What was it about the way T-T’s life has been represented that you didn’t think was accurate? They made out that he came from the lower orders. He didn’t come from the bottom; that character

28

T-T on holiday in Devon with his oldest brother Jack

Richard Stevens (right), Penny’s father and T-T’s brother

Terry-Thomas wearing – yes – pantaloons de Nimes

Yes, he had a huge presence. His father, my grandfather, was also a very large man. And his mother was a huge character. She wore a long grey plait down her back and she was a clairvoyant; she used to tell fortunes. I remember watching her on the beach at Combe Martin, swimming across the bay in a black knitted bathing suit.

What’s the earliest childhood memory you have of Terry-Thomas? Towering over me! He was a very big man, broad shoulders and very tall. I remember Tom coming down to my boarding school when I was about nine. My dad was killed on a motorbike during the War, in 1944. He’d been posted to Devon and was just about to be posted overseas. My mother was left with four very young children. The family scraped enough money together to put the three girls into boarding school, and Tom paid for my brother to go to Ardingly, where he’d been educated himself. So Tom came to visit me at my school with his brother and his wife, and it brought the school to a standstill! He was a big star by then.

How much contact did you have with ‘Tom’ after he became famous? My mother took me to Malaya, where she went after she remarried. I was there until I was 19. When I came back from Malaya, I stayed with Tom and his wife Pat [T-T’s first wife Pat Patlanski] at their house in Queens Gate Mews in London. She was a great help to him professionally. She used to sit in the audience and afterwards tell Tom what to do with his act. There wasn’t enough room for all of us, as my sister was there

And was that the Terry-Thomas that we know, with the moustache and the cigarette holder?

29

as well, so we stayed in what they called the Cowshed, a lovely little Nissen Hut in the garden. I remember lots of cocktail parties, with some top people, and once getting in trouble with Tom for pointing out that his wife was very drunk!

Do you remember much about TerryThomas’s illness? We went to see Tom do a show in Sussex in the seventies and he was already on the wane. He’d had a bad fall and he had to hold a tennis ball in his right hand to keep it supple. It was a very slow decline. The last time I saw him, I went down to the farm in Devon and he was lying in bed. He became extremely difficult to cope with; he had terrible temper rages. My sister said he was a real handful. It was the frustration. I think his mind was alright but he had difficulty communicating.

“Tom’s first wife Pat Patlanski was a great help to him professionally. She used to sit in the audience and afterwards tell Tom what to do with his act”

Did you attend the funeral of TerryThomas? It wasn’t a very big celebrity funeral; I only remember seeing Eric Sykes there from Tom’s film career. Tom’s ashes are now in the cemetery at Combe Martin, where my mother and father are buried. But there’s no headstone, only a tatty wooden cross. There’s no monument at all. He was destitute when he died; he’d spent so much money on his declining health. My sister and I are trying to save up some money to have a proper stone placed above his ashes. n

What was it like staying with them? It was lovely. I was very fond of my aunt Pat. She’d been a very renowned ballet dancer from South Africa, trained by Diaghilev. And Tom was a ballroom dancer, that’s how they met; Pat was the one who got him into the Spanish dancing. It was very tough when they broke up. The marriage broke up because she had reached the menopause, and for a whole year she didn’t get out of bed.

30

31

THE TOP FIVE FILMS OF TERRY-THOMAS

T

erry-Thomas appeared in around 80 films; some of them excellent, some of them alright, and some of them appalling. However, he was never appalling himself; every appearance by T-T in a movie is a perfect, polished performance of almost always the same character. So to pick his best performances would be to choose the whole canon of 80 films. Instead, we are going to pick the five best actual films he appeared in, so that the viewer’s appreciation is a more rounded experience than simply admiring the gap-toothed charm of the incorrigible bounder.

high flier, set against the socially and romantically awkward Ian Carmichael. Benefitting from a tight script by the uncredited Peter Ustinov, based on the brilliant One-upmanship series of books by Stephen Potter, School For Scoundrels captures the very best of British comedy acting at the end of the 1950s. A morality tale told via a series of perfectly-devised (some of them entirely ad-libbed) set pieces that work equally well as comedy sketches: the oleaginous second-hand car salesmen; the pilfering of the fountain pen; the restaurant snobbery scene; and a tennis match that has become the stuff of legend.

1. SCHOOL FOR SCOUNDRELS (1960) “Hello hello hello! Where did you find this lovely creature? Do the decent thing, old chap; fellow club members and that sort of thing. April – what a romantic name. Oh to be in England, now that April’s here!” Meet Raymond Delaunay, the fictional character closest to the real-life Terry-Thomas, or at least a fantasy version of the arch-bounder and social

2. HOW TO MURDER YOUR WIFE (1965) “She doesn’t speak English? Well, if one goes around marrying people who pop out of cakes, well… it’s catch as catch can, isn’t it.” Not Terry-Thomas’s first Hollywood movie (that was Tom Thumb, 1958) but arguably his best. True to Hollywood form, the English actor was cast as a butler against Jack Lemmon’s confirmed bachelor Stanley Ford, with Virna Lisi as the cake-popping Italian

whom Ford accidentally marries, creating friction in the male household meticulously run by TerryThomas. Lemmon and T-T were close friends, Lemmon having based his character Lord X in Irma La Douce on his English chum. Terry’s portrayal of the butler is masterful, adding notes of pathos and vulnerability that take the edge off what could be seen as a rather misogynistic tale of a bachelor plotting to do away with an unwanted lady in the house. Here we see the best of Terry’s acting skills, with lots of tocamera asides and winks to the audience. His second cousin Richard Briers was always at pains to point out that T-T had real thespian talent, often overlooked, and How To Murder Your Wife shows this to the fullest. 3. THE NAKED TRUTH (1957) “But this is England – surely something can be done?” A pure farce based around the exploits of a seedy blackmailer (Dennis Price) who threatens upstanding members of the community with publication of lewd tales of their clandestine antics in a National Enquirertype magazine. Terry-Thomas, in a break from his usual middle-management role, plays a peer with a penchant for saucy encounters with a young mistress. This was T-T’s first collaboration with Peter Sellers, who plays a nouveau riche television celebrity who also indulges in secret assignations. The two actors complement each other perfectly, refusing, for different class-based reasons, to work together against the blackmail threats. Sellers and T-T went on to make several films together that explored similar tensions between old money and new money in postwar Britain. 4. I’M ALRIGHT JACK (1958) “You haven’t been here five minutes and the whole place is on strike. You’re a positive shower, a stinker of the first order!” A stinging satire on the politics of the trades unions movement in the 1950s, I’m Alright Jack is actually a kind of sequel to 1956’s Private’s Progress, which was set during the Second World War. Men who were billeted together in the army are reunited on the battlefields of the factory floor of a munitions plant, with Peter Sellers as the Marxist shop steward ensuring that no-one works too hard, while spouting

Lenin at them and calling everyone ‘brother’. Terry-Thomas is the bumbling manager, in thrall to the upper class overlords (Denis Price and Richard Attenborough) who conduct shady arms deals with Arabs and use the workers as pawns in their game. Ian Carmichael is the innocent abroad, caught in the middle of the class system, and his rousing speech at the film’s climax takes the pitch into territory that would be explored by the Angry Young Man genre that was to follow in British cinema. 5. THE GREEN MAN (1956) A knockabout farce of the first order, with echoes of Graham Greene’s Our Man in Havana. Hapless vacuum cleaner door-to-door salesman William Blake (George Cole) accidentally foils a plot by Harry Hawkins (Alistair Sim) to blow up a cabinet minister. The audience is clearly expected to sympathise with Hawkins’ grand scheme to rid the world of pompous politicians, headmasters and dictators by assassinating them. Terry-Thomas, surprise surprise, plays the philandering Charles Boughtflower, making a grand entrance in a provincial hotel, where he is conducting an affair, by greeting the septuagenarian all-female string quartet with a sly “Hello, ladies!” Based on the play Meet A Body by Frank Launder and Sidney Gilliat, who produced and adapted this big-screen version, it was directed by Robert Day, who went on to direct The Rebel and Two-Way Stretch (both 1960). n

© Rex/Shutterstock

34

Interview

LESLIE PHILLIPS Chris Sullivan meets the great British comic actor, now aged 94, whose recollections of his career serve as a history of British film, commencing with Phillips’ origins in Tottenham in the 1920s

I

first met Leslie Phillips in the newsagents opposite my flat, as he lives but 100 yards away. After putting it off for years, I eventually plucked up the courage to introduce myself as a fan, and was greeted with the most wonderful reception I could ever have imagined. He was glowing, so grateful and so humble. As soon as I had the opportunity to interview him, we spoke at length in his home.

or 12 – it was purely a means to earn some extra money for the family, as my dad had died mainly because of the awful area he worked in – it was called Angel Road and it stank of gas and it killed him. My mother was left with the princely sum of £15 and she was essentially a humble creature, under-educated with no great expectations, and to earn money she took in clothes for repair but wanted something better for us. One day she said she wanted me to meet this lady in the West End and after much to do we met, and I enrolled at Miss Italia Conte’s stage school in Holborn. So I went there three days a week, attending drama, dance and elocution, but reverted straight back to my usual heavy cockney when I went home.

I must say, Mr. Phillips, this is a lovely house. I bought this house many years ago and it has become such a place where people buy for investment, whereas I just bought somewhere to live, and now I have inadvertently created a certain security on a massive scale. But you’re from Tottenham originally? I was born in Tottenham and grew up there. All my mother’s family lived there and then we moved out to Chingford – so I’m a Cockney and an Essex boy! You’d never guess by your accent. But I didn’t learn this accent, it sort of grew on me. I started as an actor at such an early age – 11

35

Did you realise then what a different accent might bring you? Oh no, I didn’t learn to speak like this because of the benefits, I didn’t learn for that reason. I was around people who spoke differently and I sort of absorbed it, as diction is very important in theatre – the audience have to hear what you say. But I did very well as a boy actor and made a lot of films in the thirties; I did films like the Citadel and the Four Feathers that were huge British productions.

Was Italia Conte a culture shock? Well, I learnt a lot about the opposite sex from my time at the Italia Conte school, where the girls were busty, good looking, uninhibited and daring and didn’t care if you saw their knickers when they were dancing; if they needed a quick change they would strip off in front of everyone. I twanged one’s bra strap one day and she told on me, and I learnt that no matter how inviting some ladies might appear, you have to be careful, as they might bite. But I also learnt that a good woman can teach you a lot about everything.

Did that experience as a young actor teach you anything? Yes, that teaches one everything; you have to learn how to behave and have tremendous discipline, which is something I have always maintained. I learned discipline from working and I never stopped. As a boy I played some great parts on stage but not so many films. Theatre is my background and my love and that is where I learnt everything. The stage is a great place to hone one’s talents – if you have any – you do eight shows a week and it can be tough.

I still love those huge productions like The Thief of Baghdad. It must have been exciting working with the Korda brothers, Ralph Richardson etc? I started working at Pinewood in 1938, just after it had opened, and when they just had their 70th anniversary in September they realised I was one of the few that had been there since it opened. I did some great films there. I worked alongside Rosalind Russell, who was my first glimpse of true Hollywood glamour, and she set my little knees trembling each time I saw her. I also worked alongside Rex Harrison, who showed me that to succeed, a certain amount of sexiness was important. I heard that he was a man of spectacular sexual drive and apparently irresistible charm, which I immediately recognised as a formidable weapon for an actor.

Was there one person who taught you the most? My real education was from a lady called Odette, just before I joined the army when I was 17 or 18 and was so totally naïve – she taught me everything like only a good woman can. What was it like working in the West End during the War? I worked for a long time at the Haymarket for the great Binky Beaumont, with the likes of Rex Harrison, and I did a great revival of George Bernard Shaw’s Doctor’s Dilemma with Vivien Leigh, who was gorgeous to me. She helped me after the war, both she and Larry. Binky was very what we in those days called ‘colourful’, if you know what I mean. Did the War teach you anything? The Blitz was going all the time and I was a firewatcher in Charing cross Road, when I finished at the theatre, as we did more matinees when the bombing was on. What I learnt during the war was that people got used to even the bombs, and it was unbelievable how people just got on with each other and there was a great sense of togetherness. You made friends with prostitutes and black marketeers and bus drivers and all sorts, and you lived in the war with bombs dropping all over. If you got on a tram you were not alone. It was if we were all in it together.

“Discipline in everything is very important – always be on time, don’t go missing, don’t get big headed. I’ve been told I’ve got good comic timing, but it’s all down to good diction. If they can’t hear you, they won’t get the timing”

36

Š Rex/Shutterstock

I was very dapper and a lot of people used to copy me in those days. That happened a lot.

How was it going into the army so young? My brother was one of the first in and he suffered terrible injuries and survived, but he had a very tough time.

What was the part that pushed you into the spotlight? Vivien Leigh helped me, as she had seen me go off into the army as a kid, so when I came back they were all anxious to help. I was in the play Doctor’s Dilemma, which had all the great character actors and a great director.

Were you at all scared when you joined the army? Oh No! We were all pretty gung ho, as the Germans were such a bad lot and behaving so terribly that we all were itching to get even.

What was the film that propelled your career? Well, I had the toughest director, George Cukor, and he was one tough hombre and not the sweetest guy in the world. But Kay Kendal, who’d seen me acting in Curtain Up and remembered my playing the archetypal English goony type, pulled me in for the film Les Girls, with Gene Kelly and Mitzi Gaynor, and off I went to Hollywood; I could have stayed and become the poor man’s David Niven. But I didn’t really want to, because I had young family, and that was, and is still, more important to me.

Were you not worried at being shot at by Germans? I was shot at enough by my own people. When we were training, the army were allowed 10 percent causalities and they made sure they got them. My brother used to come to see me before he was wounded at Anzio and he was on his way to Scotland, as they thought the Germans were going to invade through Scotland, so all the British Army were up there and the Germans didn’t come. But he said we did far more dangerous things up there than in battle. I was in good shape when I joined, but by the time I left I wasn’t, as we were climbing mountains with bullets over your head… what did me was all the loud bangs from the artillery. People were killed up there in training. It was worse than battle. As my brother used to say, at least in battle you know who your enemy are. In training it’s your own side.

Thank the Lord you came back. Some of those sixties films you did are priceless. Ding dong! Well they were, but we didn’t earn any money. If I had my time again I’d sign a different contract. They got us all on the cheap. All the films have been turned into TV series and they made millions and we got nothing. I only did the first three with Carry On director Gerald Thomas and then I

38

graduated to the Doctors, taking over from Kenny More for three Doctor films. But I’ve done okay and haven’t stopped working. I must have done some 100 films and a lot of TV. What about the radio show the Navy Lark? That was a great joy. I did 250 of those. I learnt about discipline there, which is very important, but it is also important to enjoy your work and be on time and not piddle about and be stupid. One of the biggest problems with telly was that they pissed about. We did the work but always had a great time.

Who or what stands out from your 70 years in front of an audience? Rex Harrison had a great effect on me – he was a real character. The funniest of all my co-stars was Kenneth Williams, who always wanted to be a serious actor but he was a delightful man, just adorable; in fact they all were, Kenny, Hattie, Sid; the only reason I watch those old films is to see them, and although I only did three films with the gang, I loved them all. I was the oldest and I am the only one still alive. What’s your secret? That I don’t know. I’m not a drinker and I gave up smoking a long long time ago, as it affected my voice – I used to smoke those small cheroots. It was the best thing I ever did.

“On Doctor in Clover I said let’s play it down, as it’s funny anyway. We don’t need to drop our trousers or anything, and it was the best of the bunch because we didn’t overdo it. If the knickers come off, it’s a different kind of game” What was it like being such a huge style icon? I was very dapper and a lot of people used to copy me in those days. That happened a lot, and also a lot of people became a doctors because of the movies. In fact I blame myself for the NHS. But gradually I started looking for better roles and started doing more classical roles, and turned my career around into a different arena and back on to the stage, where I’ve done a lot of Chekhov, Shakespeare, all sorts.

How has it been being one of the country’s most recognisable faces for years? Has it taught you anything? What I learned was that even though you might be famous all over the world, it doesn’t mean you’re rich. All I got was the actor’s fee, apart from the odd fee. I argued over Doctor in Clover and got a bit more and got to change it – I said let’s play it down as it’s funny anyway. We don’t need to drop our trousers or anything, and it was the best of the bunch because we didn’t overdo it. I learnt that to be really funny you have to under and not over play. I also learnt that funny is not often dirty; the suggestion is funnier than the actuality, and that is the secret of great humour. If the knickers come off it’s a different kind of game. The great thing I enjoy is that male and female of all ages still enjoy the films, because they are constantly on TV.

What’s it like being a sex symbol? I learnt that being a sex symbol attracts the attentions of both men and women. I get it from all sides, if you excuse the pun; no seriously, I still get boxes of fan mail [points to a big basket of assorted parcels and letters] but recently I have been so busy I have not had the time to answer them.

What about Out of Africa? Sidney Pollack was a great man to work with, and Meryl Streep is the most amazing actress. She goes through the motions during rehearsals and saves herself for the camera. Then, bang, she is remarkable. But I’ve done a lot of other work that people never mention – Harry Potter, Mountains of the

39

Moon, a lot of TV, but no-one is ever interested in that, and looking at it these days I’m not surprised.

Is there one lesson that you have learnt through all this? Discipline in everything is very important – always be on time, don’t go missing, don’t get big headed. I’ve been told I’ve got good comic timing, but it’s all down to good diction. If they can’t hear you, they won’t get the timing. I’ve also learnt that I am a better father than a husband. Being a good husband requires a lot of hard work and you have to give your wife a lot of time, especially if she doesn’t work. I was born on the same day as Hitler, so that taught me that birth date does not dictate character.

Tell me about working with Peter O’Toole. I’ve done two films with Peter. My wife Angie played opposite him many times, and we were all very fond of each other and he was a great actor. He liked to have a say in what he was doing, as he knew so much. But even though he had a reputation as being quite strong, he was also a pussycat and so funny. He loved to make you laugh on the set but didn’t overdo it. Some actors, when they become great stars, they want it all but he listened, worked and gave to his fellow actors. And that is what he did when we did those little comic scenes in the church and the café.

How many times have you been asked to say your signature “Hello!”? Millions of times, and as for my other catchphrase, ‘Ding Dong!’, I couldn’t even count. But I have had a marvellous career and I am very fortunate. One thing I have learnt is that I would have liked to spend more time with my children as they grew up.

Your careers seem to have run parallel? Yes but in a different way – he had great charisma and loved to enjoy himself, but didn’t suffer fools. I put him on a measure with John Hurt – very similar talents. Great actors listen, so that when you are saying something they are listening, and not just waiting to say their lines and hog the camera. Peter was a joy to work with. Halfway through Venus, he broke his hip and we thought, ‘Oh No!’ And the doctors said they couldn’t fix it. He had this hip fitted and we thought the film was over, but when he came back after only four weeks, he was spot on.

Next time I bump into you in the street, we should have a cup of tea. Oh yes please! That would be lovely. Goodnight, Mr. Phillips. No, please call me Leslie, dear boy, and do watch those steps as they can be very slippery! n

40

r & t ow ito an N V i s r tic i p S a l e Pa s On ket

Ti c

Trade Stands Available

See website for details

In association with:

Sunday 16 June 2019 Fantastic range of prizes

up for grabs!

Live entertainment: Bad Detectives Spitfire Sisters Jitterbug Jive

The Biggest and Best Hot Rod & Custom Show in the South!

Bowscreated by: & Bra ces

Vintag Villagee Sellin g fash the best ion, vinta ho g and acce meware e ssor ies.

New for 2019! Classic American Car of the Year Heat

beaulieuevents.co.uk 01590 612888

ISSUE

2 0 Y E A R A N N I V E R S A RY

C H A P P O RT RA I TS To mark 20 years of The Chap and our 100th edition, we photographed the most stylish Chaps and Chapettes to have graced our pages. More portraits on page 96

S A RT O RIAL •

Chap Portraits (p44 & 96) History of Savile Row (p52) • Laurie Cunningham (p60) • Saddle Shoes (p66) • Satorial Primer (p68) • Humphrey Bogart (p74) • Grey Fox Column (p82) • Style Tribes (p88) • Straw Boater (p94)

John Sothcott

Photograph: Peter Clark

Boulevardier

Cinzia Sothcott

45

Photograph: Peter Clark

Professional Coquette

Darcy Sullivan

Photograph: Peter Clark

Flâneur

46

47

Photograph: Timelight Xxxxx Photographic

Zack Pinsent

Historical Costumier

Gaz Mayall

Photograph: Peter Clark

DJ/Impresario

48

Anita Stratton

49

Photograph: Peter Clark

Interior Negotiator

Photograph: Peter Clark

Natty Bo Musician

50

51

Photograph: Scott Chalmers

Mr B

Chap-Hop Superstar

Tailoring

THE HISTORY OF SAVILE ROW Savile Row is synonymous with Great British style and a Savile Row tailor is regarded as the best in the world. Chris Sullivan takes a stroll along the Row’s long and chequered history

T

he origins of the term tailor, from the French word tailler (to cut), go back to the 13th Century, when the coat replaced the tunic. The beginnings of Savile Row, however, only go back to the Elizabethan era. Robert Baker set up shop in 1600 in the Strand to sell the ‘pickadil’, a development of the ruff, which had reached such outlandish proportions that wire supports were needed to keep it stiff. Mr. Baker’s house soon became known as Pickadilly Hall and the street that led to it Pickadilly. Baker bought another two acres of allotments that included Golden Square and Carnaby Street, installed his nephews to work there and created the beginnings of the area’s tailoring tradition. After the death of Lord Burlington, the first resident of the semi-rural area that is

now Savile Row, it was his son Richard Boyle who would really put the area on the map. Upon his return from the Grand Tour, the third Lord Burlington was intent on building grand palazzos, in the Italian style, on the land that his father had bought, naming all the streets after members of his family: Burlington Street, Cork Street, Clifford Street and finally, in 1733, Savile Row. The architect Giacomo Leoni intended that “the passenger at every step should discover a new structure” and closed each street with a fascinating architectural feature. The area was now elegant enough to receive its most conspicuous customer, Beau Brummell. We all know the story of how Brummell laid the foundations for modern elegance. Overnight, men went from an over abundance of frills and

52

lace to a silhouette that is not massively removed from today’s. Brummell’s tailors were the first craftsmen of their kind to be known as Savile Row tailors. He favoured Schweitzer and Davidson in Cork Street, Weston in Old Bond Street and Meyer in Conduit Street. After Brummell, it was Napoleon’s turn to aid and abet Savile Row. After ‘The Nightmare of Europe’ escaped from Elba, virtually every ablebodied British man was swept into service, and every officer needed his mufti. Shropshire draper James Poole, who mobilized into a volunteer corps, had to provide his own uniform. His officer noticed his tunic, asked if Poole had made it and promptly ordered a dozen. Poole profited like no other from Napoleon, accepting orders by the truckload and expanding first to Regent Street and then to Number 4, Old Burlington Street. His son Henry took over and extended the business even further into the street behind, putting Savile Row well and truly on the sartorial map. Another aid to what we now know as Savile Row was Regent Street. Commissioned by the Prince Regent, it was originally intended as a royal thoroughfare that would take the eminent fat man from Carlton House to his proposed villa in Regent’s Park. Its construction cut a swathe through the tailoring establishment, dividing the outworkers, mostly resident in the East, from the master tailors in the West. Even today, one might buy a suit from Savile Row that would cost twice that of a tailor in

Soho, even though the same craftsmen make both. This curious anomaly was created by a strange concoction of extreme snobbery and Regent Street. The tailors themselves, however, were becoming increasingly important to a gent’s existence. They became so powerful that they were able to ward off every governmental attempt to curb their wage increases. By the 18th century, tailors had become the most militant union in the country. By the 1830s the art of tailoring had become a serious business, aided by the invention of the tape measure. Just as the tailors themselves became more powerful, so grew a certain antagonism within the industry. The master tailors had become increasingly envious of the journeymen, known as ‘flints’ or ‘honourable men’, who actually did all the work. The masters

“James Poole’s officer noticed his tunic, asked if he had made it and promptly ordered a dozen. Poole profited like no other from Napoleon, accepting orders by the truckload and expanding to Old Burlington Street. His son Henry extended the business into Savile Row”

53