ISSUE 96

SUMMER 2018

EXPAND YOUR MIND, REFINE YOUR WARDROBE

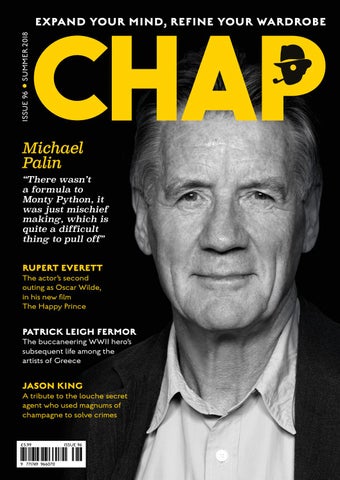

Michael Palin “There wasn’t a formula to Monty Python, it was just mischief making, which is quite a difficult thing to pull off”

RUPERT EVERETT The actor’s second outing as Oscar Wilde, in his new film The Happy Prince

PATRICK LEIGH FERMOR The buccaneering WWII hero’s subsequent life among the artists of Greece

JASON KING

A tribute to the louche secret agent who used magnums of champagne to solve crimes

£5.99

96>

ISSUE 96

771749 966070 9 9 771749 966070