THE KING’S SCHOOL INSTITUTE March 2024 ISSUE 01 VOLUME 01

Editor in Chief

Dean Dudley, PhD

Proofing

Di Laycock, EdD

Editorial Assistant

Kylie Sandilands

Graphic Designer

Heath Manion

Contributors

Tony George

Adam Larby

David Idstein

Jackie Camilleri

Lachlan Blue

Charlotte Chester

Penny Coleman

Tamara Dabic

Harry Hanna

Matthew Harpley

Patrick Hilgendorf

Sandy Mathies

Allison McDonald

Tracy Owen

Brett Pickup

Paul Taylor

Dave Trill

Ash Vali

Rodney Wood

Access this journal online at:

https://issuu.com/thekingsschool_official/docs/leader_1.1

The King’s School Institute

(02) 9683 8555 | thekingsinstitute@kings.edu.au

ISSN 2982-0197 (Online)

ISSN 2982-0189 (Print)

i

Introduction

Welcome to “Leader,” an academic journal of The King’s School Institute that showcases the intellectual prowess and thought leadership of the esteemed faculty and staff at The King’s School, Australia. Within these pages lies a treasure trove of insights, reflections, and innovative ideas stemming from the diverse experiences and expertise of our educators.

As an institution deeply committed to academic excellence, character development, and community engagement, The King’s School has fostered an environment conducive to intellectual exploration and scholarly discourse. Our faculty members, representing various disciplines and roles within the organisation, embody a rich tapestry of knowledge and perspectives, each contributing to the vibrant intellectual ecosystem that defines our institution.

“Leader” serves as a testament to the intellectual vitality pulsating within the corridors and across the landscape of The King’s School. Through a collection of essays, our faculty members delve into a myriad of topics, ranging from pedagogical innovations and educational philosophies to leadership principles and societal challenges. These essays are more than mere scholarly contributions; they are artefacts of thought leadership,

encapsulating the wisdom, creativity, and passion of our dedicated educators.

Moreover, “Leader” exemplifies our unwavering commitment to continuous improvement and lifelong learning. By sharing their experiences, insights, and research findings, our faculty members aim to inspire dialogue, spark curiosity, and drive positive change within the Australian educational landscape and beyond.

We invite you to embark on a journey of discovery and enlightenment as you peruse the pages of “Leader.” May these essays ignite your intellect, provoke contemplation, and invigorate your commitment to excellence in education and leadership.

Sincerely,

Associate Professor Dean Dudley, CF Editor-in-Chief

ii

Associate Professor Dean Dudley

Featured Articles

Navigating

Jackie

Active

Lachlan

The need for

change for students in the middle Penny

Gamification

Allison

Empowering

Tracy

Contents

Introduction

A call to empathy: Educational Leadership at The King’s School Tony George Reflections on leading at King’s – a commentary Adam Larby A proposal to apply the VUCA framework to experiential learning David Idstein

distributed leadership and team dynamics: A reflective narrative on academic excellence at The King’s School

Camilleri

bodies, active minds

Blue

Chester

Improving HSC performance in Visual Arts starts in Year 7 Charlotte

Coleman Promoting whole-school cultural competency through the English curriculum Tamara Dabic Transforming TKS Mathematics Harry Hanna Rationale and protocol paper for developing psychological capital to support teacher wellbeing and reactions to negative student behaviour Matthew Harpley Clipboard – administrative efficiency and accessibility in co-curricular programs Patrick Hilgendorf Project managing the Clipboard integration: A co-curricular manager perspective

Mathies

educational

Sandy

to improve student outcomes

McDonald

staff: A comprehensive

support and operational

framework for continuous growth

Owen

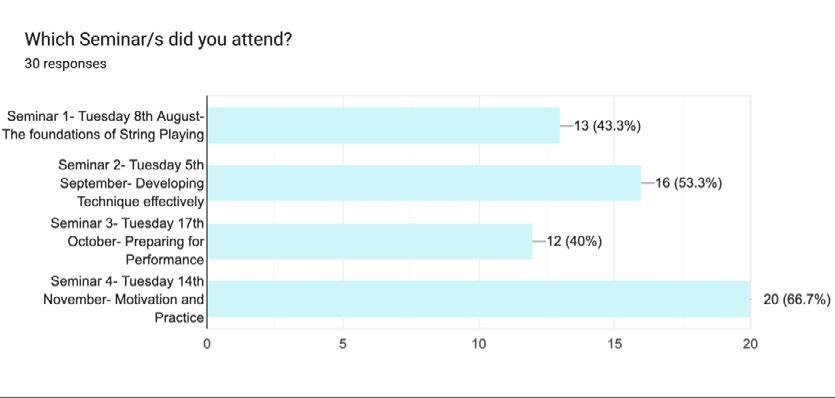

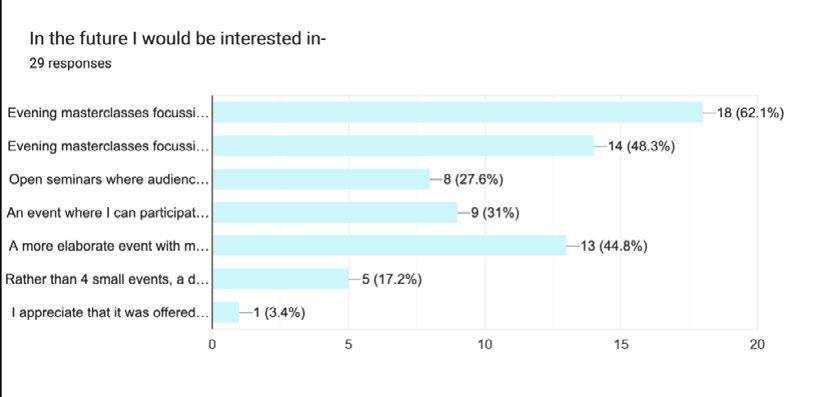

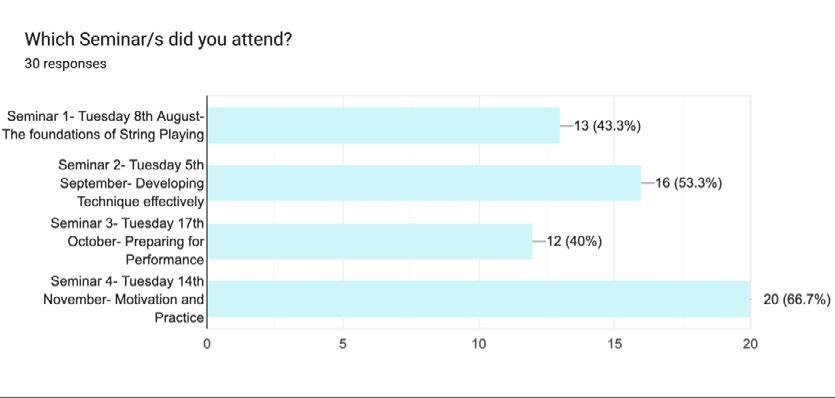

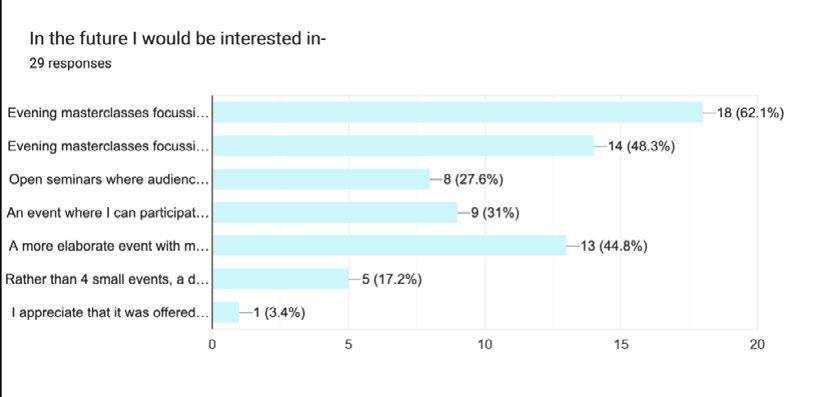

development program Brett Pickup String Seminar Series at King’s Paul Taylor Incorporation of Year 8 into The King’s School Cadet Corps program Dave Trill Cyber education – equipping the next generation in the age of technology Ash Vali Character assessment with the Student Activity and Initiative Log (SAIL) Rodney Wood 1 7 10 16 22 28 34 40 49 56 64 70 76 87 96 103 112 123 133 ii iii

Swimming

A call to empathy: Educational Leadership at The King’s School

Tony George - Headmaster

The King’s School was founded in 1831 by King William IV to produce leaders for the emerging colony of New South Wales. This is reflected in the school’s mission as “a Christian community that seeks to make an outstanding impact for the good of society through its students and by the quality of its teaching and leadership in education.” Almost two hundred years later, The King’s School continues to produce leaders, but of a very different kind and for a very different purpose. The world has changed significantly over the past two centuries and so too has school-based education. When the School was originally established, leadership formation was generally associated with the military and the intended purpose was to lead the colony of NSW. However, in the 21st Century, the scope of leadership is far broader than that of the military and that of NSW. Graduates of The King’s School aspire to commit themselves to the betterment of others through all aspects of society and across the world. And they are to do so bravely and faithfully, fortiter et fideliter (the King’s School motto).

However, instead of acknowledging and celebrating the significant achievement and contribution of independent schools to society, sections of government and the press seem intent on deriding independent boys’ schools with any story they can concoct,

invariably referencing the kinds of clickbait memes that tantalise memetic cliches, such as toxic masculinity linked to stories on single-sex schooling, or elitism linked to stories on school fees and funding. With such distractions, how are we as a modern democratic society to make sense of the contribution of schools like The King’s School for the good of society through its commitment to the formation of Global Thought Leaders through Academic Excellence with Character Development in Christian Community?

Toxic masculinity has become a memetic cliché of progressive extremism. To be clear, any kind of toxic behaviour is bad, whether by males or females in single-sex or co-ed schools. However, the practice of linking toxic behaviour to masculinity is to malign all males, just as linking oppression to the West maligns all western countries as oppressive. In sporting terms, this is to play the man and not the ball. Case in point, the criticism of single-sex schooling in this manner is not against all single-sex schooling, but exclusively single-sex elite boys’ schools. Government single-sex schools have seemed to avoid criticism, as have single-sex girls’ schools. However, the underlying agenda against the strawman of white privileged males has fuelled the creation of the term toxic masculinity and the religious fervour it subsequently generates. Rather than

1-6

Educational Leadership at The King’s School

1

George, T (2024). A call to empathy: Educational Leadership at The King’s School. Leader, 1. Leader, 1

(1).

lambast men, boys, and males with the same tarred brush of paranoia, we need to aspire to the formation of men who are empathic leaders, ready, willing, and able to bring optimism and hope as they seek the betterment of others.

The Cultural Malaise of Wokeness and Victimhood

Unfortunately, genuine critical reflection and action has given way to movements of cancel culture. For example, “wokeness,” initially a call for heightened awareness and sensitivity to social and racial injustices, has evolved into a broader social movement of complaint and victimhood. Its core principles originally involved recognising and combating systemic inequalities and promoting inclusivity. However, central to more recent critiques of wokeness are its apparent tendencies to embrace “victimhood,” focusing primarily on grievances and the identification of societal ills, often at the expense of positive action or constructive solutions. Consequently, wokeness often appears driven by a spirit of complaint rather than hope, as compared with the more hopeful and proactive stances of previous social justice movements. Significantly, the emphasis on victimhood within wokeness may lead to a lack of agency and a dearth of effective leadership, as characterised by a narrative focused on external blame, and its demands can potentially stifle self-empowerment and internal leadership within communities. Other social and political movements that have similarly navigated the challenges of advocating for change, have done so while maintaining a sense of agency and constructive leadership. No doubt, there are counterarguments that defend the movement’s approach as a necessary response to systemic injustices, without resorting to cancel culture, and while its focus on highlighting injustices

is valuable, the perceived predilection for victimhood has almost certainly hindered its potential for fostering effective leadership and meaningful change. The challenge lies in balancing the recognition of systemic issues with the promotion of agency and constructive action.

In recent years, the discourse surrounding social grievances and identity politics has undergone significant transformation. This shift, often termed as “the age of victimhood,” is marked by a distinct focus on microaggressions and a departure from the approaches of traditional civil rights movements. Campbell and Manning (2018) provide an in-depth analysis of this transition, positing that modern sensibilities have evolved towards a heightened sensitivity to slights, both real and perceived. Victimhood culture, as defined by Campbell and Manning, is characterised by a sensitivity to slight and an emphasis on victim status as a source of moral authority.

Virtue signalling, the act of publicly expressing opinions or sentiments to demonstrate one’s good character or the moral correctness of one’s position, is also a significant feature of victimhood culture. Importantly, we need to distinguish between the legitimacy of victims experiencing genuine suffering and abuse and their need and rights for justice, as against the illegitimacy of victimhood culture that seeks to use the genuine suffering of others to validate its own ideological agendas. Victimhood culture often involves signalling solidarity with victims or oppressed groups and can be seen as a way of accruing social capital in a society increasingly sensitive to issues of social justice. This contrasts with earlier “honour cultures,” which valorised physical bravery, and “dignity cultures,”

Educational Leadership at The King’s School

1-6 2

George, T (2024). A call to empathy: Educational Leadership at The King’s School. Leader, 1(1).

which emphasised stoic endurance of suffering. Victimhood culture is seen as a product of this evolutionary societal process. While Campbell and Manning’s (2018) analysis provides a compelling framework, it has not been without criticism. Critics argue that the concept of victimhood culture overlooks systemic issues and delegitimises genuine grievances. However, there is a world of difference between those who suffer violence and abuse, and those who experience ideological incongruence.

The Social Malaise of the Public Sphere

The shift in modern journalism from reporting news in the public interest to content that merely interests the public, along with the pursuit of clickbait as the financial model, has contributed to the decline of critical thought in contemporary media. The concept of identity abuse, where individuals are misrepresented and objectified for sensationalism, is a disturbing trend with children attending non-government schools being increasingly targeted and ridiculed. The landscape of journalism has undergone significant changes, with modern tabloids increasingly prioritising content that captures public curiosity over matters of genuine public interest. Consider, for example, the tabloid infatuation with the school fees of the Top 1% of schools, instead of the brain-drain affecting more than 90% of NSW Government schools by their own selective schools. This shift, driven by the monetisation and consequential pursuit of clickbait, has resulted in a decline in news quality and critical thought. The need to drive traffic and engagement has led to salacious sensationalism, often at the expense of accurate and thoughtful reporting.

The distinction between what is in the public interest (news that informs

and educates) and what is interesting to the public (content that entertains or shocks) is important, as the blurring of this distinction is detrimental to the societal role of journalism in informing the Public Sphere. The notion of the Public Sphere is important for a healthy modern democratic society. Max Weber and Jurgen Habermas, among others, both advocated for the Public Sphere as essential for a functioning modern society. A functioning modern society relies on truth telling and transparency on matters in the public interest, together with a commitment to critical thinking and discourse. However, the advent of social media and clickbait has no doubt fuelled the shift from reporting and commenting on that which is in the public interest to that which is merely interesting to the public. Certainly, gossip, rumour, and inuendo have always been interesting to the public, but economic incentives and changing media consumption that favours echo chambers of personal newsfeeds has also seen a shift from critical thought to mere criticism. Sadly, the Public Sphere may be becoming increasingly devoid of constructive critical thinking in favour of the destructive and superficial nature of criticism prevalent in the modern tabloids. Yet, while journalists have joined the ranks of politicians for losing trust and credibility with the public, tabloids and their gossip columnists are unlikely to self-reform due to their dependence on the clickbait model and the growing plethora of alternative newsfeeds. In this context, we need more critical thinking, wisdom, and leadership characterised by kindness and empathy in our education systems, not less.

The Need for Empathetic Leadership at The King’s School Leadership, while a multifaceted and dynamic concept, is essentially

School

Educational Leadership at The King’s

3

George, T (2024). A call to empathy: Educational Leadership at The King’s School. Leader, 1. Leader, 1 (1).

1-6

concerned with effecting collective decision-making for the betterment of others. Leaders need to navigate through both prosperous and adverse times, offering both stability and perspective. Consequently, leadership is significantly influenced by the ability to maintain optimism and hope, especially during challenging times, qualities that distinguish effective leaders from mere critics and sceptics. This kind of leadership stands in contrast to that of wokeness discussed earlier, which is often criticised for its emphasis on problems and perceived negativity, as opposed to the ability to see solutions and opportunities in the face of difficulties, a trait that stands in stark contrast to the cynicism and scepticism associated with wokeness. While it is relatively straightforward to lead in good and prosperous times, it is more difficult in adverse or challenging times, when leaders inevitably face heightened criticism and scepticism. It is at these times, that we need to be genuinely awake and aware of community needs, not merely woke to our own agenda, whereby awareness involves not just recognising problems but also identifying potential solutions and opportunities. Optimism and hope are crucial for leaders to inspire and guide others, particularly in contrast to the despair and complaint associated with the contemporary woke critique.

However, as discussed earlier, the original focus of wokeness to bring attention to the oppression of racial discrimination and other genuine issues of social injustice reminds us of the need for not only optimism and hope, but also forgiveness and gratitude. The cyclical nature of oppression, where victims can turn into oppressors, is a critical concept in understanding social dynamics. Both the Brazilian educator Paulo Freire and Croatian theologian Miroslav Volf offer

insightful perspectives on breaking this cycle, particularly in the context of current societal trends that veer away from empathy and towards discord. In Pedagogy of the Oppressed (Freire, 1970), Friere observed that oppressed individuals can internalise their oppression and, given the opportunity, may become oppressors themselves. This observation led to his work in bringing about forgiveness and reconciliation through social praxis, a combination of reflection and action rooted in humility, conversation, and social action. Miroslav Volf (1996) extends this idea emphasising forgiveness and living by the golden rule, do unto others as you would have them do unto you, as essential for breaking the cycle of victimhood and oppression. The contemporary shift from these ideals towards a culture of vengeance and discord, is the social context into which our graduates will need to be willing, ready, and able to bring clarity and influence.

Sadly, contemporary social movements have shifted from a focus on insight, wisdom, and empathy to a more militant form of victimhood, often exacerbating cycles of oppression. Yet, while history is replete with examples of oppressive leaders, the kind of leadership to which we aspire at The King’s School should be rooted in principles of empathy, understanding, and the upliftment of others, as opposed to domination and oppression. Adopting Freire’s and Volf’s principles could lead to more effective and compassionate leadership and social activism for the good of society and its communities.

The Formation of Character by Nurturing of Empathy

Character is often perceived as a mosaic of qualities that define a person’s moral and ethical fibre. The deeper

Educational leadership at The King’s School 4

George, T (2024). A call to empathy: Educational Leadership at The King’s School. Leader, 1(1). 1-6

dimension of character formation, that of the empathic leader, is less about what one is taught and more about what one endures and overcomes. Character is predominantly forged and shaped through challenge and adversity. It posits that character is more than a set of traits taught or learned; it is a quality honed by facing and overcoming life’s trials, enabling leaders to empathise with others and inspire hope. The character of empathic leaders, built upon experiences of suffering and perseverance, should naturally engender a spirit of optimism, humility, and gratitude. Consequently, the character with which we associate empathic leaders is not characterised by a mindset of victimhood and complaint, but by a perspective that sees adversity as an opportunity for personal growth and contribution to the betterment of others.

The relationship between character and hope is one we find in the Apostle Paul’s letter to the Romans (Zondervan NIV Study Bible, 2002, Rom 5:3-4) in which he states, “suffering produces perseverance; perseverance, character; and character, hope.” Character formation is often associated with sufferings, trials, and failures, but it is seeing failure as hitting one’s limits and striving beyond them with perseverance, being closely linked to enduring hardships and persisting despite them, that naturally cultivates a sense of hope. This hope is not naïve optimism but a grounded belief in the potential for positive change and growth, where character is shaped by life’s challenges and adversities. The transformative power of hitting one’s limits and stretching beyond them is often associated with bravery and courage, illustrating how these experiences forge resilience, determination, and integrity.

Character is antithetical to attitudes of whinging, complaining, or

adopting a victimhood mentality. While victimhood focuses on grievances and disempowerment, character is built on the willingness to strive against odds and embrace growth through adversity. Individuals of strong character often exhibit qualities such as optimism, hope, humility, and gratitude. These attributes are not superficial but are deeply rooted in the trials and triumphs of personal experience that nurture empathy and form character.

An essential aspect of character is its outward orientation – the desire not just to succeed for oneself but also to contribute positively to the lives of others, with a lived commitment to the greater good. From this perspective of character as forged in the crucible of life’s challenges, it calls for a recognition of adversity not as merely a setback or failure but as an integral part of character development, leading to a more hopeful, resilient, and compassionate society. Everyone has been a victim of something or someone at some time. This is not exceptional. It is how one responds that can be exceptional.

Conclusion

The past half-century has witnessed an unprecedented acceleration in cultural change and transformation, driven by rapid advancements in technology, travel, communication, and artificial intelligence. The implications of this accelerated change highlight the challenges posed by an increasingly volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous (VUCA) world. We are increasingly experiencing ‘wicked problems’ – problems like terrorism, poverty, and climate change, characterised by their complexity and resistance to straightforward solutions. These kinds of problems are “real world” problems, not just problems of developed countries. Furthermore, these

George, T (2024). A call to empathy: Educational Leadership at The King’s School. Leader, 1. Leader, 1 (1). 1-6

School 5

Educational

leadership at The King’s

problems are mostly human problems. The limitations of science and technology in addressing these challenges, has not only contributed to a growing distrust in traditional institutions and methodologies, but has highlighted the need for empathic leaders of character who embody wisdom, discernment, optimism, and hope.

As discussed, leadership is fundamentally concerned with effecting collective decision-making for the betterment of others, especially our global society. The rise of VUCA kinds of environments and wicked problems can be met with despair, or hope – the choice lies in the kinds of leaders we are committed to producing. At The King’s School, we aspire to produce Global Thought Leaders through Academic Excellence with Character Development in a Christian Community. Yet, as necessary as the knowledge and skills of academic excellence will continue to be, it is the character of our graduates as shaped by the School’s Christian Community, its beliefs, and values and attitudes, that will see empathic young men of wisdom and discernment ready, willing, and able to bring hope to a VUCA world. We are not only committed to shaping the mind, but the heart and the soul also. The challenge for The King’s School is that of creating innovative, interdisciplinary approaches of challenge and adventure in which our students can hit their limits and strive beyond them, all the while reconsidering how we understand and tackle the complex issues facing humanity.

References

Barker, D.L. & Burdick, D.W. (Eds). (2002). Zondervan NIV study Bible. Zondervan.

Campbell, B., & Manning, J. (2018). The rise of victimhood culture: Microaggressions, safe spaces, and the new culture wars. Palgrave Macmillan.

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed (M.B. Ramos, Trans.). Herder and Herder.

Volf, M. (1996). Exclusion and embrace: A theological exploration of identity, otherness, and reconciliation. Abingdon Press.

George, T (2024). A call to empathy: Educational Leadership at The King’s School. Leader, 1(1). 1-6

6

Educational leadership at The King’s School

Reflections on leading at King’s –a commentary

Adam Larby – Head of Tudor House

“It is winter in Narnia,” said Mr. Tumnus, “and has been for ever so long …. always winter, but never Christmas.” (Lewis, 1950, p16)

Lewis’s immortal words from The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe have captured my imagination for a long time. Reading them as a child, re-reading them as an adult, and reading them again to my children has brought new levels of depth to the words and has given me an added appreciation of the brilliance of Lewis’ mind to distil something so complex into something so simple.

The Chronicles of Narnia series of seven books penned by C.S. Lewis in the mid-20th century might feel a long way removed from 21st century at The King’s School and a professional learning journal themed around leadership, but these are wise words that have much for us to consider.

Mr Tumnus’ words to Lucy articulate a weariness in the brokenness of his wintery world and a deep longing of a return to the way things are supposed to be (cue the return of Aslan and a restoration of hope and order). But isn’t this also our experience, not of a fictional fantasy land, of reality in our own world? A weariness of the broken, coupled with a deep longing for something, anything. Failed relationships, financial pressures, the death of loved ones that seem far “too soon,” the lasting ripples of COVID-19, and news of war and conflict from near

and far. The list goes on.

Yet, like Tumnus in Narnia, the need to maintain our sense of hope, optimism, grace, and belief in our complex reality remains. For without hope we could easily end up in existentialism, stoicism, or cynicism. The existentialist sees the hopelessness of the situation and ends up in a state of despair with crippling anxiety; the stoic accepts it for what it is, builds a wall and never lets anyone in; the cynic starts to believe that there’s no point and even if there was, one person can’t make a difference and then proceeds to numb the pain or pursue hedonism. As leaders within The King’s School, we must ensure that our thinking steers well clear of these approaches.

It is worth noting that being hopeful does not have to play out as a naïve and childish mindset defined by wishful thinking. Rather, is it possible to reject these three options for our broken world and live a robust life that is rich and meaningful and a gift to others? If it is possible, what would it look like if The King’s School were full of these types of people doing life together in community?

In his book Visions of Vocation, Steven Garber (2014) stated that “These are the truest truths in the universe: We

7 Reflections on leading at King’s Larby, A (2024). Reflections on leading at King’s – a commentary. Leader, 1(1). 7-9

do not flourish as human beings when we know no one and no one knows us; we do not flourish as human beings when we belong to no place and no place cares about us. When we have no sense of relationship to people or place, we have no responsibility to people or place. Perhaps the saddest face of the modern world is its anonymity” (p133).

He also notes “... that is what matters most in life, for all of us. The long obedience in the same direction. Keeping at it. Finding honest happiness in living within the contours of our choices. To wake up another morning, beautifully bright as a summer day spreads its warmth across the grass, or awfully cold as winter blows its way over the high prairie, and stepping into the world again, taking up the work that is ours, with gladness and singleness of heart” (Garber, 2014 p196).

Organisations as large, complex, and old as The King’s School require many things to remain successful, and one of them is the strength of the community. A disparate set of individuals galvanised under the sky blue and white banner to become a living and breathing multi-generational community; a community that gives individuals an opportunity to flourish, develop and maintain hope. A community where nobody is anonymous, and everyone is fully known. A community that shares its best and worst stories to learn from the past and not repeat its mistakes.

Is simply having an affinity to King’s enough to create this type of community or is something deeper required? Garber (2014) seems to think so, but it will not be easy. His challenge for individuals and communities like King’s is summarised in one key question, “Can you know the world and still love it?” To extrapolate further, knowing what you know about yourself

and the world, having read what you have read, having seen what you have seen, what are you going to do?

Since its establishment in 1831, The King’s School has (unknowingly) sought to answer this question and it has done so in an embodied way through a “taste and see” pedagogy. Through seeing, doing, knowing, sharing, discussing, hypothesising, laughing, crying, war-crying, eating, and walking side by side, we have brought abstract assertions to life and provided glimpses of hope that it is possible to care and love and make an outstanding impact in our hurting world. The residential experiences are the foundation for an education that builds knowledge and skills whilst simultaneously developing the moral compass of the individual. The community then uses its collective knowledge and skills to act on what it knows through acts of service and love.

For us as leaders within The King’s School, this embodied pedagogy is a cornerstone of our community, but we must also remain hopeful. Sometimes, this will be despite the circumstances, and at other times, hope will be the only logical response. This is our responsibility, to lead in a way that garners hope for our community. It is a hope that The King’s School can make a significant positive difference to our neighbourhood, city, nation, and world. It is a hope that will ripple out to our colleagues, the students, the families, and the alumni. It is a hope that will challenge a public discourse that often lacks hope. It is a hope that prevents us from giving up.

The long obedience in the same direction that Garber (2014) describes is not necessarily an overly glamourous or notable existence. There will be “Groundhog Day” moments in the everyday and the mundane that feel more

8 Reflections on leading at King’s

7-9

Larby,

A (2024). Reflections on leading at King’s – a commentary. Leader, 1(1).

like duty than delight, but this is the essential work we need to consistently do. This is the exhortation from Garber’s second quote: to live a life of daily faithfulness and perseverance.

Throughout its history, The King’s School has endured “wintery seasons,” and many individuals have acted bravely and faithfully to ensure that hope was not lost. And so, the school continues its natural growth and evolution as it marches proudly towards its bicentenary, and as it does it needs brave and faithful leaders to not lose hope. Fear not … Christmas is coming.

References

Garber, S. (2014). Visions of vocation: Common grace for the common good. InterVarsity Press, Lewis, C. S. (1950). The lion, the witch, and the wardrobe. Geoffrey Bles.

9 Reflections on leading at King’s Larby, A (2024). Reflections on leading at King’s – a commentary. Leader, 1(1). 7-9

A proposal to apply the VUCA framework to experiential learning

From Aristotle’s early contemplations on character in Nicomachean Ethics to contemporary investigations conducted by Dana Born (2019) within the US and Australian Military, a prevailing and universally acknowledged consensus has emerged. This consensus posits that an individual possessing a “good” character embodies virtuous agency—someone driven by a genuine desire to discern the right course of action, actively opts for it, and ultimately follows through with decisive and principled actions.

Simply said, it is critically important that we learn from and apply the wisdom of the ancients to the current thoughts and practices as to how character and leadership are acquired and developed. The timeless wisdom of the ancients is even more relevant today given the ever-increasing pace, complexity and uncertainty faced by individuals, organisations and societies. (Born, 2019, p. 68)

Born and Megone (2019), using ancient classic Greek philosophy, go on to link good character to good leadership, and good leadership to promoting good character in oneself and society. In The Republic, Plato (2007) suggests that good character, “justice,” will lay a platform for true happiness and flourishing. Good virtues, and thus character, enables an individual

the necessary resources: courage, selfcontrol, and integrity manifesting as wisdom, to make judgements and act on them (Born & Megone, 2019). Wisdom is, therefore, promoted and understood to be a crucial component and process of character and leadership. That is, the wisdom to make decisions is both a process and an outcome of character and leadership.

Born and Megone (2019) further argue that virtue acquisition is analogous, based on a similar narrative by Aristotle, to the process of acquiring skills, such as carpentry, that is a habituation process. This process includes: guidance, practice, action and repetition, and speaks to the experiential learning model of development. The values reflect the hard skills required to perform the trade and manifest as virtues when the tradesman can execute skills under pressure in an autonomous manner.

It can be argued that, with the advent of artificial intelligence and the proliferation of the internet, information is no longer hard to come by. Almost all information that is available to humans can be accessed within seconds with an iPhone or laptop. The role of the human in this development is the uniquely human ability to make judgements through wisdom. We need the ability to discern fact from fiction when engaging

10 VUCA framework to experiential learning Idstein, D (2024). A proposal to apply the VUCA framework to experiential learning Leader, 1(1). 10-15

David Idstein – Director of Character Development and Leadership

with information. The vaccination debate and COVID conspiracy theories being recent examples where such discernment has been necessary. There are also risks that data sets can become corrupted and that AI (Artificial Intelligence) may learn from both valid and invalid data sources. With the benefit of experience and perspective, humans need the wisdom to make judgements about the potential outputs and their validity. Wisdom, a uniquely human capability, is therefore a fundamental element and crucial to leadership.

Influence

Spain and Woodruff (2023) of the U.S. Military Academy, propose The Applied Strategic Leadership Process (ASLP) in order that leader developers and aspiring strategic leaders may be able to better navigate, and thus enable, success, in an increasingly VUCA world. The ASLP model has three themes: strategic judgement (what we have reference here as wisdom), strategic influence, and strategic resilience. Judgement is useless without the ability to influence those around them (Spain & Woodruff, 2023) and thus, this model articulates the second element of The King’s School’s dual pillar leadership model of wisdom and influence. The U.S. Army defines leadership as “the activity of influencing people by providing purpose, direction and motivation to accomplish the mission or improve the organisation.” (as cited in Spain & Woodruff, 2023, p. 48). Leaders need the ability to influence the people around them, both internally and externally, to be effective and successful in leading change. Influence of change requires emotional intelligence, people skills, negotiation skills, interpersonal skills, and an understanding of the need to influence up (Spain & Woodruff, 2023).

Collective Decision Making

Boyd (1995, as cited in Spain and Everett, 2023) explains that decisionmaking can provide competitive advantage if executed faster than one’s competitor and is achieved by engaging those around you. In other words, by making collective decisions. Leadership is about major decisions and direction-setting, compared to day-to-day management, which is more aligned to the fulfilment of operational processes. This notion of leadership is supported by Zaidi and Bellak (2019), who suggest that leaders need to develop a network mindset. Lessons from military leadership demonstrate strong relationships facilitate influence, jointness, and collaboration; thus, empowering and creating common perspectives and more robust solutions (Zaidi & Bellak, 2019). Maxwell (2007) in his landmark book 21 Irrefutable Laws of Leadership doubles down and highlights the importance of influence when he declares, “the true measure of leadership is influence. Nothing more, nothing less.”

The ASLP framework and John Boyd’s articulation of the central role of decision-making in leadership, compliments the US Military’s (Spain and Everett, 2023), John Maxwell’s (1940) and Zaidi and Bellak’s (2019) weighty and direct emphasis on the importance of a leader’s ability to influence those they lead. With the above support and resonance for the dual pillar leadership model of wisdom and influence, it is timely to ask how are these attributes developed?

How do Individuals go in Character?

From the early Boy Scouts and Outward-Bound movements to modern leadership programs there is an assumption that experiential learning, particularly outdoor education, has a direct and verifiable link to

11 Idstein, D (2024). A proposal to apply the VUCA framework to experiential learning Leader, 1(1). 10-15

VUCA framework to experiential learning

the development of the virtues and behaviours mentioned above. This, it is assumed, manifests as wisdom and influence, and thus, increased leadership capacity. But how well has this link been established and what are the environments and problems faced, within the experiential learning context, that foster this growth? Further to these questions, is it possible to describe and categorise outdoor experiential learning environments with the aim of linking these characteristics to changes in behaviour? A possible framework to examine these environments is VUCA.

At King’s we deeply value and prompt the role of experiential learning in the development of character and leadership. However, to what degree is there a demonstrable link between experience, particularly in the cocurricular space, and the growth of desirable characteristics? At this point it is also worth asking are the environments that we encourage our young men to engage with in order that they be challenged, succeed, and fail, similar or unique? If, as I expect, most would agree that these events and experiences are in fact widely different and varied, it follows to ask how do they vary? With what characteristics do different experiential situations vary? And how do these varying characteristics relate and correlate to the growth of different elements of one’s character?

How Do Leaders Grow? Through Experiential Learning? A VUCA Environment?

VUCA: Volatile, Uncertain, Complex and Ambiguous. We have all been in many situations, both in our private and professional lives, that seemed particularly chaotic and VUCAed! VUCA is a term which first came out of the U.S. Army War College at the end of the Cold War in the 1960s

(Born, 2019) and has since become somewhat ubiquitous, particularly in the military context, post 9/11 and the follow-on conflicts in the Middle East, specifically the Joint Special Operations Task Force, and in business. The US Military War College continues to use this term and concept as a framework to analyse problems and develop leaders (Spain & Woodruff, 2023). VUCA gained further profile and mainstream usage when General Stanley McCrystal, commander of The Joint Special Operations Task Force, published Team of Teams (2015), and used VUCA to help the reader establish a small taste of the environment that the Task Force encountered with Al Qaeda in Iraq. General McCrystal focussed heavily on the complex environments and the important differences between a complicated and complex situation. – Jet fighters and rainforests, respectively.

Whilst VUCA environments can seem overwhelming and all-consuming, if we are able to pull ourselves out of the chaos of the dance floor and onto the balcony for at least some reflection and strategic time, it is possible to learn and take advantage of these volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous situations. VUCA environments can create opportunities and a chance for growth. How? The challenge is threefold: How do we recognise a VUCA environment? How can VUCA help us identify and categorise characteristics of challenging situations? And what behaviours and, therefore, potential growth in these characteristics, are aligned to each V.U.C.A. quadrant?

VUCA Disaggregated

While some authors have tried to capture each quadrant of VUCA, often all four are simplified to one common term to describe a VUCA environment or problem. Very few authors have

12 VUCA framework to experiential learning Idstein, D (2024). A

apply

(1). 10-15

proposal to

the VUCA framework to experiential learning Leader, 1

endeavoured to disaggregate these four quadrants beyond a vague highorder concept. Thus, this proposal is to disaggregate the four quadrants and propose a model of each. Part of this disaggregation and proposed framework will be to investigate if each quadrant of VUCA occurs to varying degrees, possibly on some sort of continuum. And how can a suite of questions be developed and applied to allow a diagnosis of situations or environments to be formed. It is possible that only through a deep analysis of each quadrant, in isolation, that it will be possible to build this complete model. A later investigation may be required to align each quadrant to possible characteristics of character; for example, the PRIME model (Bennett, 2014) which links volatility with agility.

Experiential Learning

The experiential learning theory is a holistic model, which argues that individuals grow and learn through doing and reflecting. “The Military has long recognised this strong interdependence of the Why-What-How, the importance of good leadership, and the notion of practice and habitation” (Born, 2019).

This long assertion that outdoor experiential learning has a demonstrable link to the growth of individuals has its foundation with John Dewey (1986) as the father of experiential learning theory. He suggested that a transactional relationship occurs between the individual and the environment; that is, assimilation of the individual is impacted upon by the environment, with the environment accommodating the individual: “An experience is always what it is because of a transaction taking place between the individual and, what at the time, constitutes the environment” (Dewey, 1938, p.43). Dewey proposed that an individual engages in “trying,” and the

environment “undergoing” potential change by the individual. The concept of an environment or event changing an individual is at the heart of what we understand and propose as the benefits and driving purpose of experiential learning. The environment experiencing some sort of accommodation may be a physical change, such as rubbish being picked up, or it could be a perspective change, from the individual, of the event/environment. An example of this “undergoing” might be when one perceives the challenge of camping in the rain to be a more manageable experience after having camped for a week in poor weather. Relative to the individual, this environment has changed to be less overwhelming and confronting.

David Kolb (1984) developed his “learning cycle,” which is often represented as an overly simplified version, comprising of four components: concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualisation, and active experimentation (see Figure 1).

Simplified Kolb’s Experiential Learning Cycle

Source: Ord & Leather, 2011.

Whilst Kolb uses these four elements in his model, a deeper exploration of his work shows that it may not necessarily be a cycle with steps, but rather frames of learning which are discrete and possibly occur in random order. Kolb also raises the question that

Figure 1

13 VUCA framework to experiential learning Idstein, D (2024). A proposal to apply the VUCA framework to experiential learning Leader, 1(1). 10-15

it may well be possible for a participant to be within more than one frame at a time. That is, could a hiker or camper be simultaneously experiencing, whilst also reflecting on, an outdoor adventure. Kolb (1984) goes further to suggest that retrospective reflection may not be the most powerful and meaningful sequence, but rather, reflection while experiencing the event. Likewise, he argues that it is difficult to have a concrete experience at the same time as an abstract conceptualisation; these are abilities that are possibly polar opposites. Thus, Kolb posits that learners must bring more than one learning ability to many specific situations; independently or discretely.

Dewey (1986) goes on to say that learning does not occur as one point in time but rather on a continuum across the past, present, and future. True experiential learning helps not only inform behaviour when a similar event is faced, but more powerfully, when an individual is faced with a somewhat different challenge in a varying context. That is, behaviours such as knowledge, resilience, and empathy for others are transferable from one context and experience to another. Kolb (1984) refines this thinking, by suggesting that experiential learning is not an outcome but rather a continuous process grounded in experience and making meaning from that experience. This is reflected in Dewey’s work as well:

It is not experience when a child sticks his finger into the flame; it is experience when the movement is connected with the pain which he [sic] undergoes in consequence. Henceforth, the sticking of the finger into the flames means a burn. (Dewey, 1916, p. 104)

It is, therefore, well established that experiential learning has a meaningful and powerful impact on individuals. However, neither Dewey or Kolb attempt

to investigate the characteristics of these environments and challenges. Nor do they attempt to investigate the depth or continuum of varying characteristics of problems faced by individuals.

Conclusion

As a school we deeply value and prompt the role of experiential learning in the development of character and leadership. However, how strong is the demonstrable link between experience, particularly in the cocurricular space, and the growth of desirable characteristics – character and leadership? The environments in which our young men face challenges are dynamic and unique and it follows to ask, how do they vary? With what characteristics do different experiential situations vary? To what degree? And how do these varying characteristics relate and correlate to the growth of different elements of one’s character?

The VUCA model is four quadrants, Volatility, Uncertainty, Complexity and Ambiguity, offer the potential to build a framework to assess and define the characteristics of outdoor experiential learning environments. This model has the ability to build a description or score through a suit of questions aligned to each quadrant. Through a robust and validated framework, further work may be engaged to investigate how environments of varying scores across the different quadrants, say, high in volatility, may impact an individual’s growth and development.

At King’s we understand that boys flourish and grow through the pursuit of challenge, and importantly the success and failure associated with the embrace of this challenge. A valid and reliable framework linking VUCA characteristics of environments to an individual’s growth in character and leadership

14 VUCA framework to experiential learning Idstein, D (2024). A proposal to apply the VUCA framework to experiential learning Leader, 1(1). 10-15

would provide a powerful tool to help us assess, refine, and grow our co-curricular offerings at The King’s School and Tudor House.

References

Bennett, N. (2014). What a difference a word makes: Understanding threats to performance in a VUCA world.

https:// doi.org/10.1016/j. bushor.2014.01.001

Born, D., & Megone, C. (2019). Character and leadership: Ancient wisdom for the 21st century. Journal of Character and Leadership Development, 6(1).

Dewey, J. (1988) The later works of John Dewey, Volume 13, 19251953: 1938-1939, Experience and education, freedom and culture, theory of valuation, and essays

Southern Illinois University Press

Dewey, J. (1986). Experience and education, The Educational Forum, 50(3), 241–252.

Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning. Eaglewood Cliffs.

Maxwell, J. C. (1940). 21 irrefutable laws of leadership (2nd ed.). Thomas Nelson.

McChrystal, S. (2015). Team of teams. Penguin Random House. Ord, J., & Leather, M. (2011). The substance beneath the labels of experiential learning: The importance of John Dewey for outdoor educators.Journal of Outdoor and Environmental Education, 15(2), 13–23.

Plato. (2007). The Republic. (D. Lee, Trans., 2nd ed.). Penguin. Spain, E., & Woodruff, T. (2023). The applied strategic leadership process: Setting direction in a VUCA world. Journal of Character and Leadership Development,

10(1), 47–57.

Zaidi, I., & Bellak, B. (2019). Leadership development for international crises management: The whole person approach. Journal of Peacebuilding & Development, 14(3), 256–271.

15 VUCA framework to experiential learning Idstein, D (2024). A proposal to apply the VUCA framework to experiential learning

1(1). 10-15

Leader,

Navigating distributed leadership and team dynamics: A reflective narrative on academic excellence at The King’s School

Jackie Camilleri – Deputy Head - Academics, Senior School

Grounded in the research of Harris (2018), this reflective narrative delves into the leadership dynamics and their impact on The King’s School. The journey of the school in its leadership evolution is a compelling case study of this transformation. Historically, the school’s leadership framework was defined by traditional hierarchical structures. These structures, while effective in certain contexts, often limited the scope for collaborative decision-making and innovation, which are increasingly recognised as vital in contemporary educational environments.

Harris’s (2018) research into distributed leadership provides a theoretical foundation for understanding this evolution. According to Harris, distributed leadership is not just about delegating tasks, but about creating a culture where leadership is a shared, collaborative, and inclusive process. It involves recognising and utilising the diverse strengths and skills of all team members to achieve organisational goals. This approach contrasts with the traditional top-down leadership model, where decisions are made by a few individuals at the top of the hierarchy.

At The King’s School, the shift towards this more collaborative and inclusive approach aligns with contemporary educational leadership theories, which advocate for a more

distributed, participatory, and teamoriented leadership style. This change was driven by the understanding that effective leadership in education requires adaptability, shared vision, and a capacity to foster a supportive and empowering environment for both staff and students.

The evolution of leadership at The King’s School also reflects a broader trend in educational leadership, which sees the role of a leader not just as a manager, but as a facilitator of growth, learning, and collaboration (Harris et al., 2017). This paradigm shift recognises the complex, dynamic nature of educational environments where leaders need to be responsive to the needs of a diverse community of learners and educators.

In this context, the historical leadership model at The King’s School, began to transform. The school started to embrace a model that values consultation, collaboration, and shared responsibility. This shift was not just structural but also cultural, requiring a change in mindset from all members of the school community. Leaders at the school began to see themselves more as facilitators of learning and growth, rather than mere administrators or decision-makers.

This transition towards a more distributed form of leadership has allowed the school to become more agile

16 Camilleri, J (2024). Navigating distributed leadership and team dynamics: A reflective narrative on academic excellence at The King’s School. Leader, 1(1). 16-21 Navigating distributed leadership and team dynamics

and responsive to the changing needs of its students and the broader educational landscape. It has fostered a culture of trust, respect, and mutual support, which is essential in creating an environment conducive to learning and innovation.

Adopting distributed leadership was not without its challenges. The initial phase was characterised by ambiguities in decision-making roles and responsibilities. Addressing this required the establishment of clear communication protocols and the introduction of regular team meetings. These meetings enhanced transparency and deepened staff commitment, serving as platforms for open discussions on school policies and strategies (Harris, 2018).

The Role of Reflective Practice, Team Dynamics, and Addressing Skill Gaps

Reflective practice emerged as a crucial element in navigating the complexities of distributed leadership (Harris, 2018). Regular reflection sessions, such as HSC Cluster meetings, have been instrumental in identifying areas for improvement, assessing the effectiveness of new strategies, and fostering a culture of continuous learning and adaptability. This reflective practice has contributed significantly to both personal and professional growth, enabling a leadership approach that is agile, inclusive, and responsive.

The creation of a collaborative team environment was central to our leadership approach. This required moving beyond rhetoric to genuinely cultivating a culture where diversity was celebrated (Spillane, 2012). Initiatives such as team-building exercises, collaborative strategic projects, and open forums for discussion played a crucial role in building robust team

dynamics. These initiatives fostered a sense of camaraderie and mutual respect, essential for a thriving educational environment.

A key aspect of our leadership strategy was recognising and maximising the potential of our staff. Through introspective evaluations, feedback mechanisms, and talent identification, we identified skill gaps and implemented targeted professional development programs (Brown & O’Reilly, 2020). These initiatives, including staff mentorship programs, workshops, and training sessions, were aimed at enhancing the competencies of our team members, thereby elevating the overall educational standard.

Deans of Studies: Implementing a Stage Structure

In 2022, The King’s School embarked on a strategic restructuring of its academic framework, adopting a “Stage Structure” across its three pillars of education. This approach represented a significant shift in the school’s operational dynamics, aligning three Deans of Studies with specific stages of learning—Stage 4, Stage 5, and Stage 6. This alignment brought about a more nuanced and effective oversight of academic matters, tailored to the distinct needs and developmental stages of the student body, now at 250 students per cohort.

The implementation of the Stage Structure marked a departure from the traditional, more generalised approach to academic management. Each Dean of Studies was assigned to oversee a specific stage, allowing for a more specialised focus on the educational and developmental requirements pertinent to that stage.

The roles of the Deans of Studies became pivotal in bridging the gap

17

Navigating

distributed leadership and team dynamics

(1). 16-21

Camilleri, J (2024). Navigating distributed leadership and team dynamics: A reflective narrative on academic excellence at The King’s School. Leader, 1

between the strategic vision of the school’s leadership and the practical, day-to-day academic operations. Working closely with the Deputy Head (Academics), the Academic Office, and Heads of Department, the Deans of Studies played a crucial role in translating the school’s educational goals into actionable plans and initiatives at each stage. This collaborative approach facilitated a more cohesive and aligned effort across different departments and levels, ensuring that the school’s academic objectives were consistently pursued and achieved, thus enhancing the distributed leadership model at The King’s School.

Deans, with their specific stage responsibilities, were able to develop a deeper understanding of the needs and dynamics of their respective student groups. This focus facilitated a more tailored approach to professional development, mentoring, and support for Year Coordinators. It also encouraged the Deans to innovate and experiment with new methods and designs of curriculum that were particularly suited to their stage of learning. With Deans focusing on specific learning stages, they were better positioned to monitor and support the emotional and psychological well-being of students, alongside Year Coordinators and Housemasters. This holistic approach ensured that students received not only academic guidance but also the necessary support to thrive in all areas of their school life.

Transition to a Transdisciplinary Model

Historically, The King’s School operated under traditional departmental structures, characterised by distinct academic disciplines with minimal cross-departmental collaboration. While effective in certain respects, this model limited the scope for interdisciplinary

learning and innovative problem-solving. In 2022, the school initiated a transition to a more transdisciplinary approach. Departments were reorganised into clusters, fostering greater collaboration and shared expertise. This represented a significant step towards enhancing pedagogical practices and academic excellence.

Transdisciplinary learning, integral to The King’s School’s educational approach, merges knowledge from multiple disciplines, fostering holistic problem-solving and equipping students for real-world challenges. This method transcends traditional academic boundaries, enhancing creativity, innovation, and a comprehensive understanding of complex issues. Paramount in today’s educational landscape, transdisciplinary learning not only promotes holistic problem-solving and collaboration but also prepares students for contemporary challenges. It encourages communication, fosters creativity and innovation, and aligns with the evolving demands of the workforce. By integrating diverse fields of knowledge and expertise, this approach cultivates innovative solutions, preparing students for the complexities of the modern world.

Implementing Distributed Leadership through Deans of Clusters

The King’s School’s initiative to restructure its academic departments into transdisciplinary clusters represents an innovative step forward in enhancing collaboration, sharing expertise, and improving pedagogical practices. The move towards this transdisciplinary approach is marked by the creation of clusters such as the “Thought Leadership” and “Global Engagement” clusters. These clusters have already shown promising results in fostering

18

distributed leadership and team dynamics Camilleri, J (2024). Navigating distributed leadership and team dynamics: A reflective narrative on academic excellence at The King’s School. Leader, 1(1). 16-21

Navigating

greater cooperation among departments and enhancing the overall educational experience.

In 2022, the physical integration of the Languages department with the Thought Leadership cluster staff room was a significant step, leading to increased collaboration and a fruitful exchange of teaching methodologies. This integration serves as a model for the potential benefits of a more interconnected academic structure.

The next phase of this transformation involves the introduction of Deans to oversee these clusters, a move intended to enhance the distributed leadership model and streamline the reporting process to the Deputy Head of Academics. This phased introduction of Deans, beginning with two and gradually expanding, is a strategic approach. It allows for the careful development of leadership capacity within each cluster while maintaining the focus on collaborative excellence.

The Thought Leadership Cluster, under the guidance of Sonya Harper, and the Global Engagement cluster, led by Jeanette Mikhael, are poised for continued success. Both clusters, which include high-performing departments that have demonstrated a strong ability to collaborate and elevate their pedagogical standards and are particularly noted for consistent outstanding HSC results, are indicative of the kind of leadership that can drive the school’s academic ambitions forward. The focus on leveraging the expertise of emergent leaders will be crucial in this process.

Adopting a staged approach to introduce Deans of clusters over two or more years, allows the school to build on its existing strengths, develop necessary

leadership capabilities, and ensure the retention of key talent. This gradual implementation also facilitates increased collaboration opportunities between the newly appointed Deans, further reinforcing the school’s commitment to a transdisciplinary approach and a distributed leadership model.

Challenges and Opportunities in the Transition

The transition to a transdisciplinary model and distributed leadership presented both challenges and opportunities. Aligning diverse academic cultures, fostering open communication, and developing shared goals were critical hurdles. However, these challenges also provided opportunities for professional growth, innovation, and enhanced student learning outcomes.

The transition to collaborative leadership at The King’s School has been instrumental in driving academic excellence. This shift, characterised by involving a diverse array of perspectives in decision-making and strategy formulation, has led to the implementation of more effective, innovative educational programs. The inclusive nature of this approach has brought about a transformative change in the way educational strategies with new interventions are conceived and executed. By drawing on the collective wisdom and experience of a broader segment of the school, including teachers, staff, and sometimes students, the school has been able to design and deliver curricula that are not only academically rigorous but also resonant with the needs and interests of its students.

The democratisation of the decision-making process has resulted in a stronger sense of ownership and commitment among the staff.

19

Navigating distributed leadership and team dynamics

16-21

Camilleri, J (2024). Navigating distributed leadership and team dynamics: A reflective narrative on academic excellence at The King’s School. Leader, 1(1).

Teachers and administrators, feeling more invested in the outcomes of their efforts, have shown heightened levels of engagement and performance. This heightened engagement is evident in the classroom, where teachers employ more dynamic and student-centred teaching methods, leading to more interactive and engaging learning experiences for students.

The impact of this collaborative leadership is clearly reflected in the exceptional academic results achieved by The King’s School, especially in the Higher School Certificate (HSC) across various courses. These achievements have not only bolstered the school’s reputation for academic excellence but have also laid a solid foundation for the introduction of the International Baccalaureate Diploma Programme. The successful implementation of this program requires a strong academic foundation, which The King’s School has demonstrably built through its impressive HSC results.

Furthermore, these academic achievements are all the more remarkable considering they have been attained alongside a strong focus on cocurricular activities. The King’s School’s commitment to holistic education, which emphasises both academic excellence and character development, has resulted in producing confident, well-rounded individuals. Students are not only achieving high academic standards but are also developing essential life skills such as leadership, teamwork, and resilience. This balanced approach is preparing students for the challenges they will face beyond the school gates, in higher education and in their future careers.

The balance between academic rigor and character development underscores the effectiveness of the

distributed leadership and robust team dynamics at The King’s School. By fostering an environment where leadership is shared and collaborative, and where every member of the school community feels valued and empowered, the school has created a vibrant, dynamic learning environment. This environment not only drives academic success but also nurtures the personal growth of each student, ensuring they are not just academically proficient but also equipped with the character and skills needed to succeed in all aspects of life.

Conclusion

The King’s School’s evolution underlines the pivotal role of distributed leadership and dynamic team collaboration in achieving and sustaining academic excellence. The school’s transformative journey, marked by a series of strategic shifts and adaptations, highlights the challenges encountered and the innovative strategies employed to foster a culture rich in collaboration, innovation, and ongoing improvement. These experiences not only enrich the broader dialogue on effective leadership in educational settings but also offer valuable insights for other institutions navigating similar pathways.

The introduction of the Stage Structure in 2022 stands as a key milestone in the school’s progressive approach to academic leadership and management. By aligning Deans of Studies with specific learning stages, the school has reinforced its distributed leadership model, deepened collaborative ties among its academic staff, and focused its efforts more effectively on education delivery and student development.

Moreover, the School’s strategic pivot towards a transdisciplinary approach, characterised by the

20 Navigating distributed leadership and team dynamics

Camilleri, J (2024). Navigating distributed leadership and team dynamics: A reflective narrative on academic excellence at The King’s School. Leader, 1(1). 16-21

inauguration of Deans overseeing clusters, affirms its commitment to academic distinction, pioneering leadership, and cooperative learning. This approach is poised to enrich the educational experience, cultivate leadership skills, and establish the institution as a frontrunner in modern educational methodologies.

Crucially, the impact of collaborative leadership at The King’s School has been profound and multifaceted. It has not only elevated the quality of education but has also led to remarkable academic achievements. More importantly, it has nurtured the growth of well-rounded individuals, equipped to navigate the complexities of the world with confidence and skill. This holistic approach to education, adeptly balancing academic rigor with character development, exemplifies the efficacy of the distributed leadership model and the positive dynamics of teamwork within the school.

In essence, The King’s School’s journey is a resonant example of how adaptive leadership, a focus on transdisciplinary learning, and a commitment to collaborative excellence can collectively forge an educational environment where innovation thrives, academic achievement is celebrated, and students are holistically prepared for the future.

References

Bourke, J. (2016). Which two heads are better than one? how diverse teams create breakthrough ideas and make smarter decisions. Australian Institute of Company Directors.

Brown, M., & O’Reilly, K. (2020). Developing leadership for the changing world of work: Insights, best practices, and thought leadership. Springer.

Harris, A. (2018). Distributed leadership: Implications for school improvement. School Leadership & Management, 38(2), 134–144.

Harris, A., Jones, M., & Huffman, J. B. (Eds.). (2017). Teachers leading educational reform: The power of professional learning communities. Routledge. Spillane, J. P. (2012). Distributed leadership. John Wiley & Sons.

21

distributed leadership and team dynamics

Navigating

Camilleri, J (2024). Navigating distributed leadership and team dynamics: A reflective narrative on academic excellence at The King’s School. Leader, 1(1). 16-21

Active bodies, active minds

Lachlan Blue: Colour Housemaster and Teacher, Tudor House

The “Active Bodies, Active Minds” initiative is a proposed project intended to transform the learning experience at The King’s School, Tudor House. Inspired by Nordic schools’ practices (Wilkins, & Corrigan, 2019), which send students outdoors every 45 minutes, this project explores the potential connection between physical activity and heightened classroom concentration.

The primary goal of this proposed initiative is to enhance students’ overall wellbeing and academic performance through thoughtfully designed, short physical activity sessions. Research indicates that physical activity can positively influence students’ attentiveness and behaviour (Ruhland, & Lange, 2021).

The potential implementation of this project at The King’s School, Tudor House, would involve structured sessions that focus on increasing heart rates, enhancing cognitive function, and promoting overall wellbeing. These brief, invigorating breaks aim to empower students, enriching their mental states while fostering independence and responsibility.

With existing evidence supporting this approach, “Active Bodies, Active Minds” represents a promising modern educational best practice. Adopting this strategy, The King’s School, Tudor House can create a more engaging and

holistic learning environment. Students may excel academically while developing a deeper connection to their physical wellbeing, making this proposal an innovative approach with the potential to positively impact the academic and personal lives of Tudor House students.

Students’ Health and Concentration

Physical activity is crucial for holistic child development as it impacts both physical health and cognitiveemotional wellbeing (Melbourne & Port, 2018). In today’s increasingly digitalised and sedentary classrooms, schools, educators, and parents are responsible for introducing, nurturing, and normalising physical activity. Recent research has illuminated effective strategies comprehensively addressing this challenge (Booth et al., 2020).

One noteworthy discovery emerged from a citizen science study led by Booth. Engaging in self-paced outdoor activities, exemplified by “The Daily Mile” for just 15 minutes, proved a significant benefit for pupils’ cognitive performance and overall wellbeing (Booth et al., 2020). This approach outperformed the alternatives of mere sitting or standing outdoors and exhaustive running exercises. The key factor here is the term “self-paced,” allowing students to determine the intensity and pace of their activity; thus, enhancing enjoyment and

22 Active Bodies, active minds Blue, L (2024). Active bodies, active minds. Leader, 1(1). 22-27

maximising the mental and physical wellbeing advantages (Booth et al., 2020).

Interestingly, while not achieving the same benefits as self-paced activities, high-intensity physical activities were beneficial, too. They yielded results similar to the control measures in the study, indicating their suitability for inclusion in the physical activity curriculum without adverse effects on students (Booth et al., 2020).

The holistic benefits of these self-paced physical activity breaks extend well beyond immediate cognitive enhancements. Long-term health benefits align with acute cognitive improvements, bolstering the learning environment (Booth et al., 2020). Furthermore, Booth and colleagues note that these breaks are practical tools to support and enhance learning, solidifying their position as invaluable components of modern education.

However, it is crucial to emphasise that these breaks should not be considered replacements for other forms of physical activities. Booth et al. (2020) emphasise that these activity breaks represent one avenue to augment youth activity levels. Traditional physical education (PE) and active transportation methods retain their essential roles. My research underscores that selfpaced breaks offer supplementary advantages, justifying their integration into school routines. Decisions regarding their implementation should be made collaboratively by educators and school administrators.

Bershwinger and Brusseau’s (2013) study provides additional evidence of the benefits of classroom activity breaks. Their research found that Fourth Grade students who participated in classroom activity breaks averaged 845 more steps

and 4.6 more minutes of moderate-tovigorous physical activity (MVPA) per day than those who did not.

Additionally, Janssen et al.’s (2014) study highlights the positive impact of physical activity within the school setting. Their research demonstrated that brief physical activity breaks, especially those of moderate intensity, significantly affected the attention of primary school children. These findings suggest that incorporating moderate-intensity physical activity breaks into the school day can effectively enhance students’ attention levels (Janssen et al., 2014).

Additionally, Janssen et al.’s (2014) study serves as a reminder of the significance of integrating physical activity breaks into the daily school routine. These breaks offer cognitive benefits and contribute to developing well-rounded and healthy students (Janssen et al., 2014). Schools can cultivate an improved learning environment by encouraging students to participate in moderate-intensity physical activities during holidays, ultimately positively influencing overall school performance (Janssen et al.). This research underscores the multifaceted advantages of integrating physical activity into the educational setting, highlighting its role as a cognitive and physical development catalyst in young learners (Janssen et al.).

It becomes apparent that physical activity is pivotal in fostering holistic child development and recent research underscores its vital role within the school setting. Initiatives like “The Daily Mile” and self-paced activity breaks demonstrate the profound impact of incorporating physical activity into students’ daily routines, benefiting their immediate cognitive performance and long-term wellbeing (Booth et al., 2020; Janssen et al., 2014). Bershwinger and

23 Active Bodies, active minds Blue, L (2024). Active bodies, active minds. Leader, 1(1). 22-27

Brusseau’s (2013) research further supports the implementation of classroom activity breaks, highlighting their potential to increase students’ daily physical activity levels. Schools can take proactive steps to promote physical activity by:

• offering a variety of selfpaced and moderate-intensity physical activity breaks throughout the school day,

• collaboration between educators and school administrators to implement a variety of self-paced and moderate-intensity physical activity breaks throughout the school day,

• giving students opportunities to participate in traditional PE classes and active transportation methods,

• encouraging students to be physically active during holidays and extracurricular activities. (Booth et al., 2020; Janssen et al., 2014)

Optimising Student Wellbeing and Concentration: Insights from Classroom Demographics and Activity Strategies

The Year 1B class at The King’s School Tudor House, a private educational institution in the Southern Highlands of New South Wales, is composed of seventeen students, including nine boys and eight girls, all aged between 6 and 7 years old. This setting provides a unique environment for their daily interactions and learning experiences.

In a classroom of seventeen students, the gender distribution provides insight into the demographic dynamics of modern classrooms. The

near-equal representation ensures that classroom discussions, activities, and group work have a balanced mix of male and female perspectives. This balanced dynamic is particularly beneficial in creating an environment where both genders can express themselves freely, ensuring a comprehensive view of student responses and interactions in various scenarios.

Within an educational framework, transitions between different spaces play a vital role in the flow of the day. Moving students from the structured environment of a classroom to the open expanse of an outdoor setting requires well-coordinated planning. Every minute counts, and the route taken, the order of movement, and even how students line up can influence the efficiency of this transition. Pre-defined paths, clear markers, or designated student roles (like door holders or line leaders) can assist in smoothing this movement, ensuring minimal disruption.