4 minute read

Island Dreams

in search of DISTANT ISLANDS

In his book Island Dreams: Mapping an Obsession, published in 2020, Edinburgh-based GP and writer Gavin Francis weaves cartography, philosophy and literature into reflections on his own travels to islands around the globe. The following extracts include some of his explorations on Scotland’s west coast

Iwas in search of distant islands, in love with the idea that, on a patch of land, protected by a circumference of sea, the obligations and irritations of life would dissolve and a singular clarity of mind would descend. It proved more complicated than that.

Iona. Blaeu Atlas Maior, Vol. 6, Æbudæ Insulæ sive Hebrides (1662–5)

One November at the close of the millennium, when I was starting out as a junior surgical trainee, I left the hospital wards behind for a week’s camping on the Hebridean island of Barra. The forecast was for storms: after a couple of nights in a shaking tent I swapped canvas for a hotel room, and set up my camp stove in the en-suite bath. Each day I walked: over the high blustery freedom of Ben Scurrival, around the western reaches of the island, down to Vatersay Sound, across beaches raked by waves. There were families of otters, endless horizons, abandoned homesteads, inquisitive seals. There was a beach that doubled as an airport runway, its landing timetable rotating with the tide.

The open bays were chopped into textual, symmetrical lines of waves. The agitation kindled by my hospital work was gradually extinguished. As the days passed I began muttering as I walked, random subconscious connections, snatches of songs, memories. Their content didn’t seem to matter, my voice being lost in the sound of the wind and waves. At age twenty-one the writer Adam Nicolson inherited the Shiant Isles, a tiny archipelago between the Scottish mainland and the island of Lewis. In his book about them, Sea Room, he wrote: Perhaps . . . the love of islands is a symptom of immaturity, a turning away from the complexities of the real world to a much simpler place, where choices are obvious and rewards straightforward. And perhaps that can be taken another step: is the whole Romantic episode, from Rousseau to Lawrence, a vastly enlarged and egotistical adolescence?

Thinking of islands often returns me in memory to the municipal library I visited as a child. The library was one of the grandest buildings in town – entered directly from the street through heavy brass doors, each one tessellated in panes of glass thick as lenses. As my mother browsed the shelves, often as not I’d sit down on the scratchy carpet tiles and open an immense atlas, running my fingers over

DISTANT ISLANDS

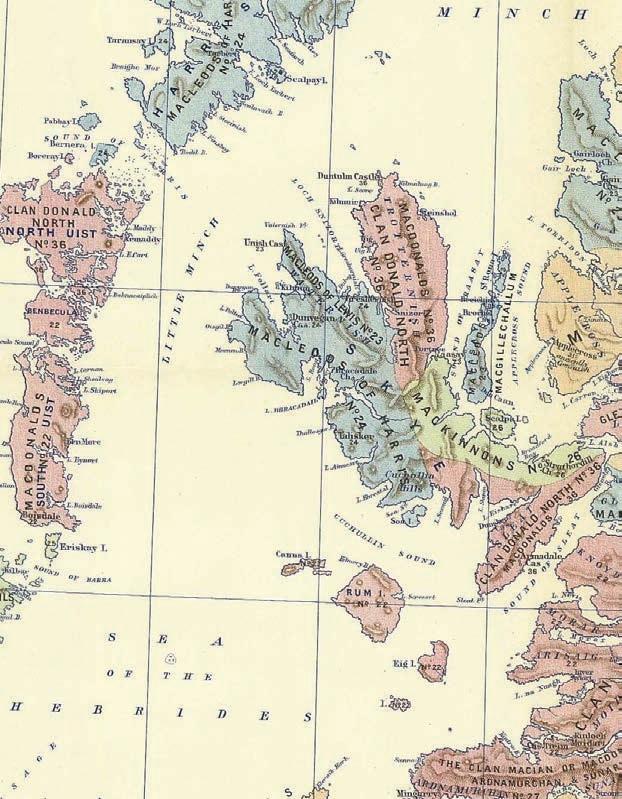

Skye. Map of the Clans of Scotland (1899)

distant and unreachable archipelagos as if reading Braille. I hardly dared hope I’d reach any of them; that I have reached a few is something of a relief. And so the love of islands has always, for me, been inextricable from the love of maps.

Around 1,500 years ago an Irish monk known as Brendan explored the archipelagos north and west of the island of Britain – his oral account has survived in a Latin text dated to the ninth century, the Navigatio Sancti Brendani Abbatis. The Navigatio

sees Brendan and his companions beaching their leather boat on an island carpeted in flowers of white and purple. White, the narrator informs us, represents innocence. Purple, on the other hand, with its undertones of papal, imperial and Byzantine authority, represents maturity.

That sense of awe or reverence, of seeking after the sublime, that so many others have sought and found in islands, has without doubt influenced my love of them. This may have been what first drew me to Iona, an island off the west coast of Mull, and the adopted home of Brendan’s contemporary Columba. Columba sailed there from Ireland on the same kind of leather boat Brendan used. In common with many of the islands I’ve been writing about, Iona is often now considered ‘remote’; but when people connected more easily by sea than by land, it was much less so. For Columba, Iona was central to the Irish world. This was a time of shifting borders: Irish Scoti pushing east into the lands of the Picts.

SCOTLAND BY THOMAS BRUMBY JOHNSTON AND JAMES A. ROBERTSON SCOTLAND MAP COLLECTION; FROM HISTORICAL GEOGRAPHY OF THE CLANS OF L TO R: (NLS 108520521) USED WITH THE PERMISSION OF THE NATIONAL LIBRARY OF

On Lewis I met a buzz-cut banker from New York who had quit his job to spend three months cycling around the Hebrides, hauling his surfboard behind him on a trailer. He had already cancelled his flight back. I’d begun to doubt it was possible to feel this free,

he said. It reinforced to me that my fascination with islands – my isle-o-philia – was far from unique. There seemed to be a connection between a certain kind of sparsely populated island, remote from urban centres, and dreams. Or perhaps it is that such islands have the power of concentrating dreamers.

Extracts, published with kind permission from the author, are taken from Island Dreams (Canongate) © Gavin Francis 2020