Nº 52 £5.95

THE LIBRARY'S EMERGING WRITERS: WHAT HAPPENS NEXT March 2022

Natalie Bennett Travis Elborough

10% off Library membership for you and a friend! Do you have friends or family that would relish access to our outstanding collections and spaces? Refer them to the Library now and receive a 10% discount on both of your memberships! Our

offer is available to anyone

to the Library

member and

membership types

discount

current

checkout and

*This is an introductory offer valid for new members only, T&Cs apply and are at

limited

introduced

by a current

applies to the first year of membership, valid across all

until midday on 31 March 2022. The

for

members is applied upon renewal. Friends can join online using the code MAG-FRIENDS at

must enter the current member’s name under ‘How did you hear about The London Library?’. Find out more at londonlibrary.co.uk/join

londonlibrary.co.uk/terms

D.

5 D. News 7

D.

11 D.

14 FEATURES F.

16

F.

24

F.

32 Popular

LAST WORDS L. Events 40 Rhythm and

fiction and

the

L.

42

CONTENTS 32 24

DISPATCHES

Welcome from the Director

Most borrowed of 2021 New books on display The Library seeks new Trustees Changing of the Guard Books

From the Archive

Collection Story

Sky’s the Limit

What the alumni of the Library’s Emerging Writers Programme do next

Changing the System

Natalie Bennett, the Green Party peer, has always been a bookworm

Outside the Box

history knows no bounds in the work of Travis Elborough

Poetry, short

Claire Tomalin feature in

spring programme

Meet a member

International correspondent Pádraig Belton

FOR THE LONDON LIBRARY

Julian Lloyd Head of Communications Felicity Nelson Membership Director

The London Library 14 St James’s Square London SW1Y 4LG (020) 7766 4700 magazine@londonlibrary.co.uk

EDITORIAL: CULTURESHOCK

Contributors Rachel Potts, Alexander Morrison, Deniz Nazim-Englund

Photography Theo Lowenstein (cover), Thomas Duffield, Hanna Gabler Art Director Alfonso Iacurci

Designer Thomas Carlile Production Editor Claire Sibbick

Publisher Phil Allison Production Manager Nicola Vanstone

Advertising Sales Cultureshock (020) 7735 9263

The London Library Magazine is published by Cultureshock on behalf of The London Library © 2022. All rights reserved.

Charity No. 312175.

Cultureshock 27b Tradescant Road London SW8 1XD (020) 7735 9263 cultureshockmedia.co.uk @cultureshockit

The views expressed in the pages of The London Library Magazine are not necessarily those of The London Library. The magazine does not accept responsibility for unsolicited manuscripts or photographs. While every effort has been made to identify copyright holders, some omissions may occur.

ISSN 2398-4201

WELCOME

Here’s to creativity

Our first issue for 2022 covers varied ground, as ever, but a prominent theme emerges in the importance of the Library to writing and research. Interviews with writer Travis Elborough and politician Natalie Bennett illustrate the point. Travis has been a member for two decades and his impressive range of eclectic titles have almost all been inspired by books from our collection. Ex-Green Party leader Natalie Bennett –who combines a hectic life in the House of Lords with a deep interest in history, ecology and feminism – is an equally voracious reader.

New writing is also celebrated with a focus on our Emerging Writers Programme, now entering its fourth year, and which supports as-yet-unpublished writers at the start of their careers. It has been a pleasure to bring participants together for this issue, to hear how they are enjoying publishing success and developing their work. We’re inspired to see new writing talent emerging and proud of the role that our programme has played in promoting it.

The Library as a creative hub is represented in a new display in the Issue Hall, featuring books written by Library members in recent years. Inevitably it represents only a fraction of the 700 books they produce every year, but we hope it celebrates the industry and creativity that is so abundant here. With members joining the Library in record numbers, and a packed events programme running in-person and online, there’s a genuine creative buzz around 14 St James’s Square.

So much of that is down to the hard work and support of our members, for which we’re very grateful. Many choose to support the Library even further by volunteering as Trustees. We’re recruiting a number of new Trustees this year and if you would like to apply, the article on p9 will tell you how. •

Philip Marshall, Director

5

MOST BORROWED OF 2021

What does the list reveal about members’ reading habits?

Biographies, novels and titles from the History and Art section topped the list of books borrowed more than five times from the Library last year, and were among more than 50,000 loaned out in total in 2021.

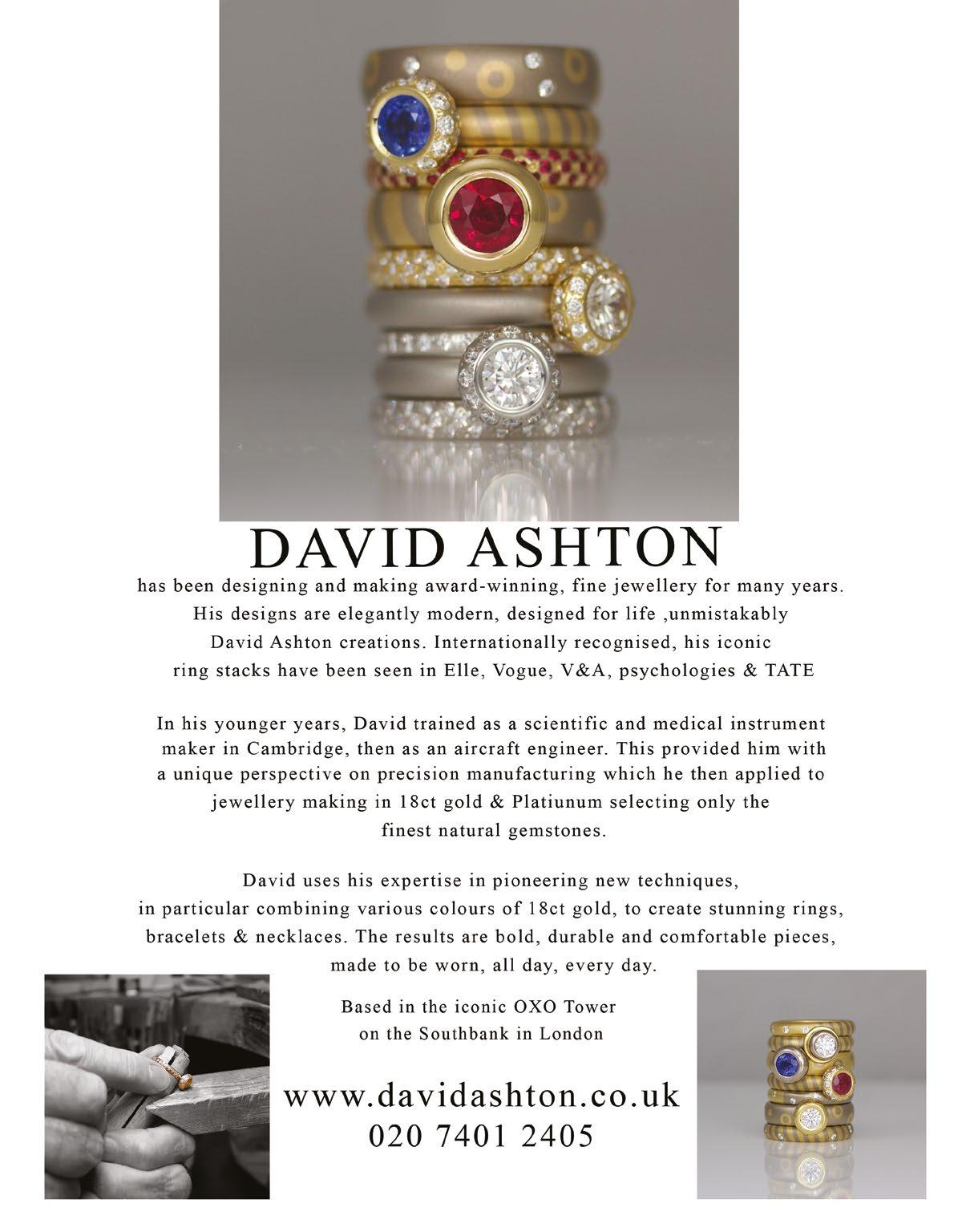

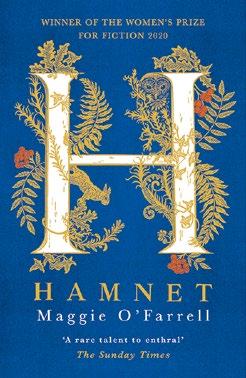

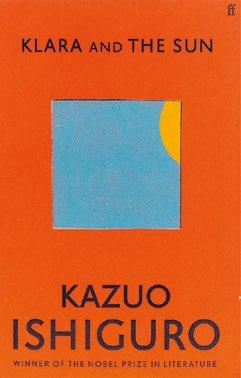

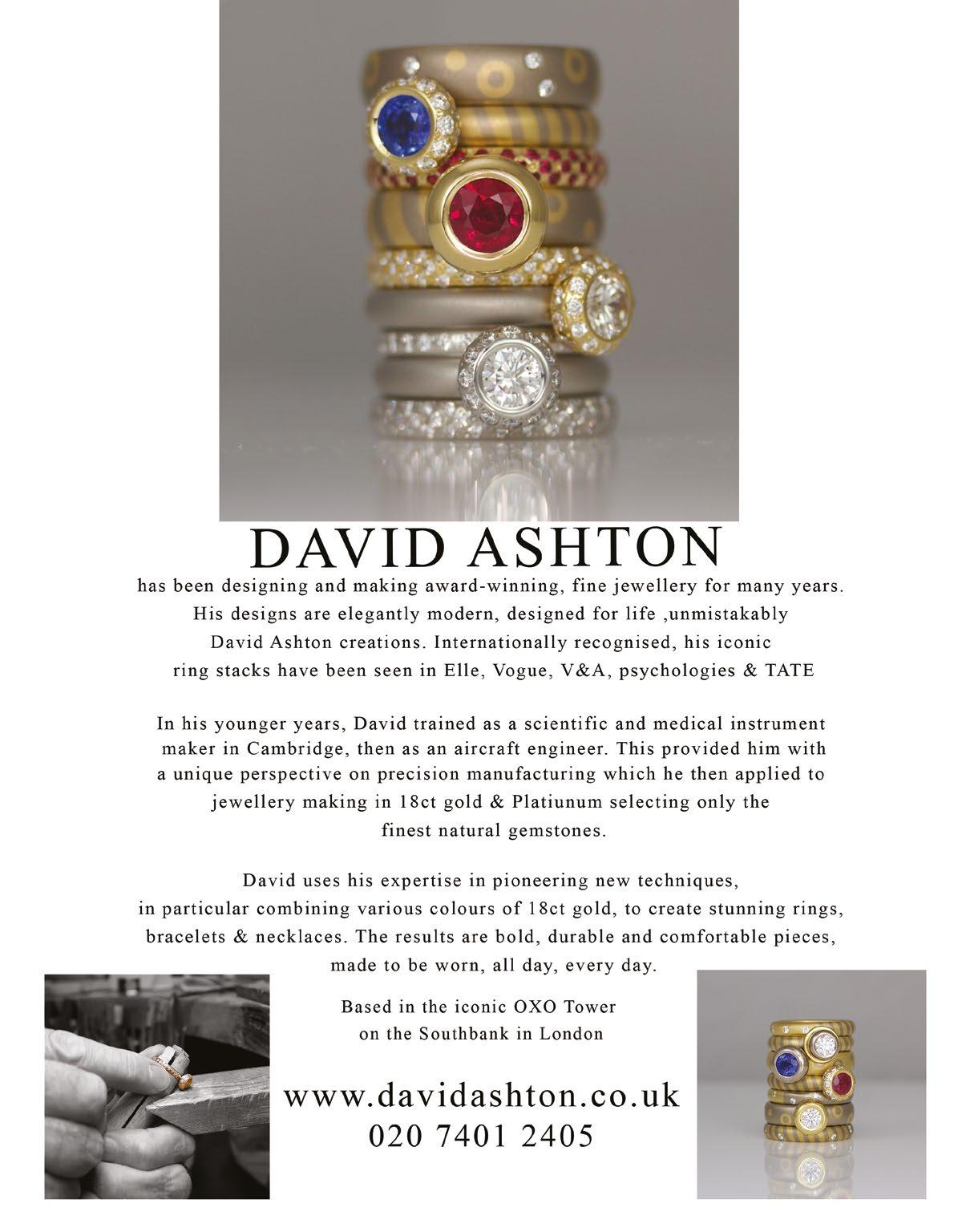

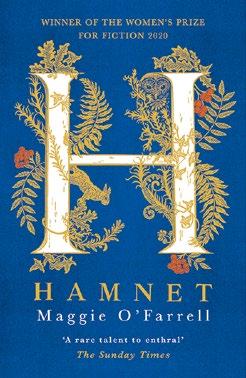

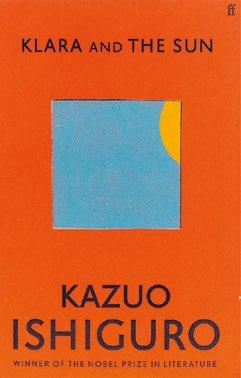

Top of the most-borrowed list was Kazuo Ishiguro’s Bookerlonglisted Klara and the Sun (borrowed 16 times), closely followed by Philip Hoare’s lyrical study of the artist Albrecht Dürer, Albert and the Whale (borrowed 14 times) and Maggie O’Farrell’s novel Hamnet, a fictional account of Shakespeare’s

son who died at age 11 (borrowed 13 times). In fourth place – and the top biography – is volume one of Henry ‘Chips’ Channon: The Diaries, edited by Simon Heffer, and described as “weapons-grade above-stairs gossip” by Ben Macintyre in The Times (borrowed 11 times).

With 10 borrows each, Paula Byrne’s The Adventures of Miss Barbara Pym, Sathnam Sanghera’s Empireland and Marina Warner’s autobiography Inventory of a Life Mislaid tied in fifth place. Honourable mention must also be made of latecomers – the

The three most-borrowed books of 2021

“Flying Off the Shelf Award” goes to David Kynaston’s On the Cusp: Days of ’62, the latest in his series of wide-ranging histories of postwar Britain, which was taken out no fewer than nine times since its arrival in the Library in September, placing it as one of the six most-borrowed titles of the year. •

The full list of books borrowed more than five times in 2021 can be found at londonlibrary.co.uk/ most-borrowed-books-2021

7 NEWS

NEW BOOKS ON DISPLAY

A celebration of Library members’ creative output

A new display in the Issue Hall celebrates the extraordinary output of London Library members. Panels installed next to the Red Stairs feature almost 120 book covers selected from the thousands of titles written by members over the past three years.

It is estimated that 700 books, 15,000 articles and 400 scripts and screenplays are produced by members each year – with their use of the Library’s resources generating an output of £21m into the creative economy.

The new display can only capture a partial snapshot of members’ publishing activity, but the panels will be

updated regularly to feature new books and, alongside the physical books display in Mason’s Yard, will highlight the Library as a centre of literary creativity.

The Library welcomes information on members’ publishing activity. This information is useful in planning the development of the collection and looking for ways to promote members’ work. •

Notify the Library about your new book at newbooks@londonlibrary.co.uk

New panels illustrate some of the hundreds of books written by members each year

8 NEWS

OPPORTUNITY TO JOIN THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES

We are seeking up to three enthusiastic and committed people to join The London Library Board as trustees.

Trusteeship involves helping with the Library’s overall governance, monitoring our strategic goals and supporting the Executive team. All trustees should be willing to engage in a constructive and collaborative manner with all the challenges affecting the Library and to act as its advocates in the wider world.

Our trustees are volunteers but the role can be highly rewarding in terms of personal development and the enjoyment that comes with working collectively in the best interests of the Library.

The Board meets four times a year and trustees will usually also sit on two committees (each also meeting four times a year). In addition to attending meetings, trustees will need to allow time to read meeting papers circulated in advance, offer advisory support and attend occasional Library events.

Trustees must be members of the Library and, due to trustee retirements this year, we are

particularly seeking candidates with substantial professional skills and experience in marketing (including an understanding of digital marketing), financial accounting (familiarity with the techniques of accountancy and the preparation of accounts), or recent publishing experience as a writer or researcher. It would also be helpful to hear from candidates with experience of managing IT projects and also those with current experience of EDI practices and strategies. However, we look forward to hearing how candidates from any background might feel they could use their own skills and experiences to benefit the Library and its governance.

We are keen to ensure a diverse and inclusive Board and so encourage applications from all backgrounds. Please also note that, while we are interested in some particular skills and experiences that are sometimes associated with professional qualifications, no specific educational or professional qualification is required in order to become a London Library trustee.

TRUSTEE PLACEMENTS

We are also seeking two young members to become Trustee Placements on the Board as the current post-holders will retire their positions this year. The Trustee Placement scheme is open to members aged between 18 and 30 and is designed to encourage participation by younger members at Board level. We value the insights and contributions of younger members very highly and we aim to ensure that our Trustee Placements receive a positive experience of charity governance. Please note that young members are also welcome to apply for our other trustee positions if they choose. The closing date for applications is 24 April 2022. •

Find out more about these roles and how to apply at londonlibrary.co.uk/work-for-us

9 NEWS

CHANGING OF THE GUARD BOOKS

The Library’s entire borrowing collection will be soon be searchable online

After recent progress by the Retro Cataloguing team, the Library’s venerable Guard Books will be brought into retirement. Housed in the Cataloguing Room and arranged into volumes of Author and Subject Indexes, for decades these print catalogues had been the only way to search the collection and negotiate the idiosyncrasies of its shelfmark system. The arrival of online systems – and especially Catalyst, which provides searchable records for more than 95% of the Library’s collection – made them largely redundant, but they could not be entirely replaced as they contained records of a few thousand old or obscure titles for which no digital cataloguing records existed. Throughout the pandemic, the Library team worked to unveil their remaining secrets. A data-matching

exercise revealed that some 12,500 items in the Guard Books were not listed on Catalyst. Digital catalogue records were created for them all before the team went in search of the books themselves. More than 8,000 have been traced, barcoded and integrated into the Library’s borrowing system (ALMA) and are now discoverable on Catalyst.

Work to track down the remaining 4,500 books is estimated to be completed this spring, and the Guard Books can then finally stand down after decades of service. Painstakingly produced, they are remarkable volumes in their own right and will be kept in the Issue Hall, in recognition of their unique contribution to the history of the Library and its collection. •

10 NEWS

FROM THE ARCHIVE

Letters to librarians are full of surprises

Coming from names like Somerset Maugham, George Bernard Shaw, Barbara Cartland and the exiled Italian revolutionary Giuseppe Mazzini, notes about routine book loans sent to librarians past have more life in them than you might expect. Sometimes this member correspondence, now kept in the Library’s archive, offers something quite personal. A 1951 air mail letter from Los Angeles was typed by Aldous Huxley – who suffered from poor and deteriorating eyesight for much of his life – and thanked the Librarian for the books he received some months ago. “I regret that I have kept them so long,” he wrote. “But

I have been interrupted in my work by recurrent attacks of iritis which has caused all manner of delays.” His letter ends with a touching postscript written in his increasingly illegible hand: “Excuse mistakes. I am still unable to read what I have written.”

More formal is a two-page letter typed on Women’s Social and Political Union stationery and dated 19 April 1915. It was sent by suffragette Christabel Pankhurst, then living in semi-exile in war-torn Paris, and contains her application for London Library membership. With hostilities on the Western front intensifying (she was writing

11

George Eliot’s 1871 letter concerns a long overdue book. Photo: Thomas Duffield

12 THE LONDON LIBRARY

A 1951 air mail letter to The Librarian from the Brave New World author, Aldous Huxley. Photo: Thomas Duffield

“Aldous Huxley’s letter ends with a touching handwritten postscript”

six days before the second battle of Ypres), Pankhurst reassures the Librarian: “Books will be brought over to me by hand, and returned in the same manner; so that they will be perfectly safe.” She offers a deposit of £5 to cover any books lost en route. Her letter also confirms that suffragette Grace Roe – released from prison the previous year as part of a government amnesty and Head of Operations for the WSPU – was Pankhurst’s contact in London dealing with her Library book borrowings.

A snapshot of George Eliot’s domestic life is contained in a three-page letter from May 1871 to her stepson George Henry Lewes (“Dearest Boy” from “Mutter”). Describing her recent illness and reporting that “Pater remains jolly”, Eliot is chiefly concerned to address an overdue London Library book – Friedrich August Wolf’s Prolegomena to Homer – recently requested by another member. Eliot had kept this somewhat obscure scholarly work for five months, relying “too confidently on the unlikelihood that anyone else would ask for it. Now however, by way of Nemesis, some student turns up who wants the said volume.”

In her letter she apologetically asks Lewes to find the book. “This much is certain,” she writes. “It is in one of the bookcases in my study.” With hundreds of books in her possession, Eliot thoughtfully offered further assistance, providing a description of the overdue book’s cover and the note: “It is very probable that it is in the upper shelves, or else in the middle cupboard, of the long bookcase that used to be in the drawing room in Blandford Square.” The Library still has a copy of Wolf’s Prolegomena from that time, suggesting Lewes succeeded in his mission.

Less successful was the Library’s rather desperate attempt to involve Stanley Kubrick in a hunt for unreturned books borrowed by novelist Gustav Hasford. Hasford had served as a military journalist during the Vietnam War and in 1979 published the bestselling novel The Short Timers, which was eventually adapted into Kubrick’s feature film Full Metal Jacket. In January 1987, shortly before the film’s release, the Librarian contacted Kubrick about Hasford “in the hope that you may know his current whereabouts”, as “I am anxious to locate him, simply to recover the books”.

The Librarian was right to be concerned. It turned out that Hasford was already wanted for grand theft in California for stealing from the Sacramento Public Library in 1985. Three years later, 10,000 stolen

books from libraries across the US, UK and Australia were found in his possession and he was sentenced to six months’ imprisonment.

While the Library’s letter to Kubrick is a model of polite – if anxious – restraint, the Librarian was unable to hold back when berating a careless member five years earlier: “We have just received back from you the copy of FH Hinsley, Power and the pursuit of peace, which you borrowed on 6th January 1982, and I am writing to protest in the strongest possible terms about the condition of this book.

“When my colleagues opened it to cancel the loan, they found inside the front end-papers the squashed bodies of 13 dead houseflies. Their reaction was one of instant disgust, and it is one I share.” The book was rebound in 1997 and thankfully no longer bears witness to the carnage that took place inside its covers.

•

13

THE ARCHIVE

Snapshot of a suffragette’s life: Christabel Pankhurst writes from Paris in 1915. Photo: Thomas Duffield

FROM

COLLECTION STORY

The Library holds a first edition of a classic work that divided opinion even before it was published a century ago

Cover page of the Library’s 100-year-old first edition. Photo: Thomas Duffield

14

This February marks the 100th anniversary of the publication of James Joyce’s masterpiece, Ulysses. Written between 1914 and 1921, it is regarded as one of the first great works of modernist literature. Before appearing as a book, it began in serialised form in US journal The Little Review from March 1918 to December 1920, and sections of the novel also appeared in London literary journal The Egoist, in 1919. These early serialisations soon ran into trouble.

Three of the chapters appearing in The Little Review were banned by the US Post Office before Joyce’s notorious Nausicaa episode appeared in 1920, which led John S Sumner, Secretary of the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice, to instigate a prosecution for obscenity. At the trial in 1921, the magazine was declared obscene and, as a result, Ulysses effectively banned in the US (until a court case reversed the ruling in 1932).

Joyce was resident in Paris at this time and had become part of the literary circle surrounding Americanborn bookseller and publisher Sylvia Beach. She agreed to publish the work in its entirety, suffering significant debts as a result, and released 1,000 numbered copies through her Shakespeare and Company publishing business on 2 February 1922, Joyce’s 40th birthday.

The print run of the first edition consisted of 100 signed copies on fine Dutch handmade paper sold at 350 francs, 150 copies on vergé d’arches paper at 250 francs, and 750 copies on less expensive linen handmade paper – one of which, copy no 316, is owned by The London Library.

Throughout the 1920s, the US Post Office Department burned copies of the novel and it fared little better in the UK, following the intervention of Sir Archibald Bodkin, the famously reactionary director of public prosecutions. Offering his opinion to customs authorities on whether to block its import, Bodkin acknowledged: “As might be supposed, I have not had the time, nor may I add, the inclination to read this book.” (He only managed pages 690 to 732.) Nonetheless he was able to advise that, “In my opinion the book is obscene and indecent… It is filthy and filthy books are not allowed to be imported into this country”. The novel was banned in the UK until 1936.

The Library’s treasured first edition came through a bequest made by Dr Ripley Oddie, medical consultant and director of Bayer Products, who died in 1959 at age 57. Oddie was fascinated by Ulysses and studied it carefully in his spare time. He was not the only fan. TS Eliot – Library President at the time Oddie made his bequest – had been greatly influenced by the work at the start of his own career. Writing in The Dial magazine in November 1923 (a year after his own modernist classic The Waste Land was first published) Eliot wrote: “I hold this book to be the most important expression which the present age has found; it is a book to which we are all indebted, and from which none of us can escape.”

The book was bequeathed by Library member Dr Ripley Oddie in 1959.

15

Photo: Thomas Duffield

•

“The US Post Office Department burned copies of the novel and it fared little better in the UK”

SKY’S THE LIMIT

For authors who make it onto the Emerging Writers Programme, access to the Library and unrivalled peer support are just a hint of what’s available to help with their craft, says Alison Flood

Making a name for themselves in writing: (back row, from left) Daniel Janes, Anastasia Taylor-Lind, Amber Medland, Krystle Zara Appiah, (front row) Gaar Adams, Mónica Ibarra Parle, Lianne Dillsworth. Photo: Theo Lowenstein

17 §

Anastasia Taylor-Lind is a war photographer, working for major publications from National Geographic to TIME magazine. She began working on her first collection of war poetry last year, and acceptance onto The London Library’s Emerging Writers Programme felt “like a creative door” had opened for her. “It was an affirmation that I was on the right path, finding a way to combine poetry and my photojournalism work,” says Taylor-Lind, whose first collection, One Language, is out on 1 March from independent press Smith|Doorstop. Ask any of the 100+ writers to have made it onto the Emerging Writers Programme, and they say something similar. “So much of writing for me is about confidence. It can feel indulgent, you question whether it’s OK that you’re

choosing to write when we all have competing responsibilities,” says Lianne Dillsworth. “When I received the email to say my application was successful, it was an incredible boost. My main emotion was relief – getting a place on the Programme gave me permission to prioritise my writing.” Dillsworth’s novel Theatre of Marvels, about a young Black British woman performing in one of the freak shows that were so popular in Victorian-era London, was pre-empted by Windmill within 24 hours and will be published in April.

Carole Hailey did an MA in creative writing at Goldsmiths and a PhD in the same subject at Swansea University. But it was only when she landed a spot on the Programme that she felt justified in calling herself a writer.

Hailey, 51, had been a lawyer before giving it up to go back into education. When she got a call to tell her she was one of 40 authors to be selected by The London Library from hundreds of applicants for the Programme, “it genuinely was the first time that I felt validated as a writer”.

“I thought, if they think I’m good enough to pick me, then it’s OK to say I’m not just an ex-lawyer,” she says. “You have to have a certain amount of potential to get onto an MA or PhD but, frankly, you’re paying for it. This was the first time I thought it was worth giving up my career, and the very nice income that I had, to try to be a novelist.” She has gone on to land a deal with a major publisher for the book she was working on during her London Library year, a fictional memoir written by a grieving daughter.

Daniel Janes, who now writes for popular Netflix series The Crown, feels similarly. “When I applied, I was a researcher. I’d done short plays, I’d made short films, but I wasn’t enormously professionally advanced,” says Janes, 32. “Before, if people asked me what I did, I’d come up with euphemisms, and say I dabbled in writing. But being in a world in which our writerly status was acknowledged and encouraged, and meeting people who were in the same position, means I don’t have those reservations now.”

Mónica Ibarra Parle, who was on the first year of the programme, agrees. “I’ve been working on a literary novel for a long time, and have writing groups I belong

18 THE LONDON LIBRARY

Daniel Janes writes for the popular Netflix series The Crown. Photo: Theo Lowenstein

to, but writing young adult fiction was a new challenge. It was wonderful to find a great group of writers to read my work, who were talented and thoughtful readers, and have such a vast map of the genre,” she says. “Every time I’m stuck they’re ready with a book recommendation, an offer to read a tricky passage or just a sympathetic ear. Beyond that, they were my lifeline during the pandemic. I don’t know that I would have retained any sense of self as a writer without them, juggling paid work with home-schooling my two children.”

The Emerging Writers Programme is now in its third year, with applications recently opened for the fourth. It offers authors – across all genres – writing masterclasses and events, which have included major names such as John

O’Farrell, Edward Docx, Jane Feaver, Hannah Lowe, Moira Buffini and Nii Ayikwei Parkes, as well as one year’s free membership of The London Library, literary networking opportunities and peer support. There is no application fee, and the Programme is funded through philanthropic support from individuals, and a range of trusts and foundations. The only stipulation is that applicants must be over age 16, and “working or planning to work on a specific project, with the aim of publication or production, have a clear idea of how they might use the Library’s resources to achieve that aim and be willing to fully participate in all elements of the Programme”.

“There are elements that you need to be a writer: time, space and resources, and guidance helps, too,” says Claire

SKY’S THE LIMIT

Krystle Zara Appiah has signed a six-figure deal for her first two novels. Photo: Theo Lowenstein

“I don’t think it’s good to write in isolation. It’s really important to have a group around you” – Krystle Zara Appiah

Spanning genres and age groups. (Left to right) Daniel Janes, Anastasia Taylor-Lind, Gaar Adams, Lianne Dillsworth, Mónica Ibarra Parle, Krystle Zara Appiah. Photo: Theo Lowenstein

Spanning genres and age groups. (Left to right) Daniel Janes, Anastasia Taylor-Lind, Gaar Adams, Lianne Dillsworth, Mónica Ibarra Parle, Krystle Zara Appiah. Photo: Theo Lowenstein

Berliner, who runs the Programme. “We wanted to create something that was for everyone, so no age limits, no genre limits – they just couldn’t have been published, or have had a mainstream production of their work.” Hailey appreciated this aspect of the Programme. “I really liked the fact that age wasn’t an issue, because so many emerging writer things are for those under 30,” she says. “I understand that, but it can be a bit demoralising to be an older new writer.”

In the first year, the Programme received 600 applications for 40 places, the second year 800, and the third, 1,000. Expert judges – a mix of authors, publishers and agents –selects each year’s participants; the 2021/22 cohort includes poets, playwrights, screenwriters, non-fiction writers, novelists, children’s authors and graphic novelists, spanning in age from early 20s to early 60s. Alumni range from Gaar Adams, who spent the Programme working on his book Guest Privileges, which explores queerness and migration in the Arabian Peninsula, to Amber Medland, whose debut novel Wild Pets came out from Faber last summer.

“We ask applicants to submit a writing sample and a brief description of what they plan to work on throughout the year,” says Berliner. “We ask them to talk about their writing, or what makes them interested in it, and in the Library and the Programme. We’re basing the decision on the whole application to see if they really want to get involved, and want that development, that community.”

The culture of peer support was definitely the most important part of the Programme for Janes. “We still meet every month, which encourages us to produce stuff. Writers need external pressure, and we create a friendly climate of encouragement.” As part of the mixed-genre group of authors, Janes says his peers have encouraged each other to experiment. “We can find new frontiers in our writing and not feel restrained by anything, shoot at the moon. The missile won’t always land, but it’s great to launch it,” he says.

Towards the end of the Programme, writers are given guidance about the book industry. Many, says Berliner, have landed book deals, been published or signed with agents.

Natasha Hastings, who was in the first cohort of Emerging Writers, was signed up by HarperCollins

21 SKY’S THE LIMIT

22 THE LONDON LIBRARY

Mónica Ibarra Parle’s fiction has been shortlisted for the Queen Mary Wasafiri New Writing Prize and the Bridport Prize. Photo: Theo Lowenstein

“Writing young adult fiction was a new challenge, and it was wonderful to find writers who had a vast map of the genre”

– Mónica Ibarra Parle

Children’s Books in October for a magical historical series aimed at 10–13-year-olds; Krystle Zara Appiah has signed a six-figure, two-book deal with The Borough Press for her debut novel.

“I’d written a draft when I applied, but I needed a place to edit. I had some very noisy neighbours,” says Hastings, who was 25 when she landed a place on the Programme, and is now 28. “I absolutely loved it. It was so motivating, being around people who have published books or are about to. I grew up seeing books on shelves, but didn’t realise it was a career I could have. It was only when I was in The London Library, and would speak to writers, that I saw that this was actually a job that people did – it was amazing, so motivating.”

Appiah was already immersed in the publishing world when she applied for the Programme, working as a children’s books editor; although she had a draft of her novel, she wanted the “accountability” that the Emerging Writers Programme would provide. “I liked the idea of having that really intentional year, to give me a kick up the bum and make me work on it,” she says. “I set myself a goal, which was to finish the draft and start the next book, which I did. The other writers were brilliant – we have a WhatsApp group and still chat regularly. I don’t think it’s good to write in isolation – it’s important to have a group around you.”

The chance to work in The London Library itself – with its historic collection dating back to 1841, when founding subscribers included Charles Dickens and John Stuart Mill – has also been important to participants, although lockdowns put paid to regular in-person visits.

“It was a bit spotty for our cohort because it coincided with lockdown, but there were times when I’d go every

weekend,” says Janes. “I took a week off work and spent most of it at the Library. I like to work in the Art Room, near the snuffboxes and shoemaking section.”

For Hailey, located in North Pembrokeshire, a quick trip was difficult, but the online resources were “fantastic”. “I had to do research around the use of contraception in the Democratic Republic of Congo,” she says. “I thought I wouldn’t find anything. But I found more than I could possibly read.”

To Berliner, the peer support is absolutely key to the Programme, and it continued even through lockdowns, with the instigation of Zoom meetings where the authors would work in each other’s company.

“To write something is a mad thing to do, it’s a shot in the dark, it takes forever, it’s solitary. Part of it is knowing that there are people who are as mad as you, but it’s also being able to talk about what you’re doing,” she says. “If you find people who are interested in the same things, who are struggling in the same way, it’s helpful. The London Library itself is a community – that’s what a lot of people love about it, and it’s also how it was started, by a writing community. It’s always been an inclusive space for writers.” •

Alison Flood is the Guardian’s books reporter

From the Silence of the Stacks, New Voices Rise Vols 1 and 2, anthologies of writing by alumni of the first two Emerging Writers Programmes, are available to download from The London Library’s website, for Kindle (£2) and in print (£8). For more information, including on 2022/23 applications, visit londonlibrary.co.uk/emerging-writers-programme

23 SKY’S THE LIMIT

Gaar Adams worked on a novel during his time at the Library, and has since signed to an agent and been accepted onto Penguin’s WriteNow programme. Photo: Theo Lowenstein

“I would spend my life here, happily.” Natalie Bennett in the Back Stacks. Photo:

Hanna Gabler

CHANGING

THEFor former Green Party leader Natalie Bennett, history, ecology and feminism are the pillars of her life, and her reading. Rachel Potts meets her among the Stacks

25 §

SYSTEM

It was an Elizabethan poet who first drew Natalie Bennett to The London Library. A former Green Party leader – now Baroness of Manor Castle, the area of Sheffield in which she lived until recently – Bennett moved from Australia to the UK in 1999. She was working as a print journalist, and used to walk the capital’s streets “looking at the blue plaques and asking, ‘Where are all the women?’” In 2004, she “met” Isabella Whitney in a shop selling out-of-print academic books – Whitney lived in the city in the 1560s-70s and is considered the first English woman to publish secular poetry. She inspired Bennett to write a book about women in London’s past; joining the Library was a first step.

Whitney’s life and writing suggest a breezy disregard for early modern social norms, which appealed to Bennett. Female members of the nobility sometimes wrote religious verse, but Whitney is believed to have been a member of the minor gentry: she worked, probably as something similar to a lady’s companion, in a wealthy London household (though lost her position in 1573, for reasons that are unclear), and wrote from the perspective of her class. The poem Her Wyll and Testament is a satirical goodbye to London: “For maidens poor, I widowers rich / do leave, that oft shall dote: / And by that means shall marry them, / to set the girls afloat.”

Bennett’s book is still on her to-do list, because on New Year’s Day in 2006, when she’d finished a series of night shifts as a news sub-editor at The Independent, she made the “utterly spur of the moment” decision to join the Green Party. In 2012, she went from part-time campaigner to winning its leadership race, and for the next four years experienced the Green surge including an historic election result in 2015, at which more people voted for the party than at any previous election combined. This career trajectory might have been unplanned, but on meeting Bennett it doesn’t seem all that surprising. Among members of the House of Lords, “particularly the whips,” she says: “‘Hyperactive’ is an adjective that has been used about me quite a bit.”

She has three degrees – undergraduate degrees in agricultural science and Asian studies and a master’s in mass communications – and spent four years in Thailand, at the National Commission on Women’s Affairs and consulting on women’s issues for the UN. She then worked in Fleet Street for more than a decade, including as editor of The Guardian Weekly, and had always imagined one day leaving journalism for work in an NGO or charity. But the climate emergency dawned in earnest in the mid-2000s and took her into politics.

Women poets and reading at the Library did not recede completely. In 2015, the Campaign to Protect Rural England asked for British party leaders to nominate a verse. Bennett found the “perfect green poem” by another Elizabethan.

26 THE LONDON LIBRARY

“Where I grew up, the cultural highlight of the week was mowing the lawn”

Bennett’s maiden speech in the House of Lords referenced the 19th-century poet Mary Hutton.

Photo: Hannah Gabler

Bennett’s maiden speech in the House of Lords referenced the 19th-century poet Mary Hutton.

Photo: Hannah Gabler

RECOMMENDED READING

A few of Natalie Bennett’s favourite books

DOUGHNUT ECONOMICS

BY KATE RAWORTH (2017)

BY KATE RAWORTH (2017)

“My number one book recommendation. An economics professor recently told me that all his first year students were talking about this, so it’s clearly catching on, which is lovely. Mainstream economics starts from the assumption that resources are replaceable, but the foundational Green understanding is that you can’t have infinite growth on a finite planet, which this book addresses.”

S. Finance &c

WOMEN LATIN POETS BY JANE STEVENSON (2005)

“A spectacular piece of scholarship from when Eastern Europe first opened up from behind the Iron Curtain. The author went to monasteries in the region, about which very little had been published before, and found some amazing, scholarly women from what we used to call the Dark Ages up to the Renaissance. It’s the best book I've ever read from The London Library.”

L. Medieval Lit., Hist of

THE NEW ECONOMICS, A MANIFESTO

BY STEVE KEEN (2021)

BY STEVE KEEN (2021)

“Not easy reading. Keen does at one point say, ‘You might want to go and get a cup of coffee if you’re not into maths’, which I did. But it tears apart the foundations of economics thinking. Keen goes back to the physiocrats: French economics thinkers of the 18th century who thought that wealth came from land. He wonders whether, if they had informed our economic framework, we might be in a better place.”

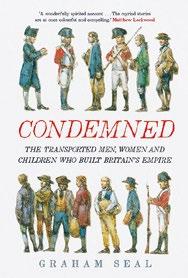

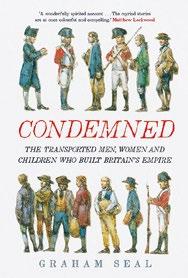

CONDEMNED BY GRAHAM SEAL (2021)

“I try to read things without a particular angle, but often the politics gets in there somewhere. This reveals how, in 1690, the City of London rounded up 100 children that it didn’t like the look of, that didn’t have an economic place, and shipped them to Virginia. This kind of thing goes on for a very long time right through to the history of Australia.”

S. Crime

28

Æmilia Lanyer’s Description of Cooke-ham from 1611 discusses natural beauty and female companionship, set on an estate where she stayed with her patron, Countess Clifford. Bennett maintains a history blog, Philobiblon , set up in 2004, and her unwritten book has become a podcast, History of the Women of England

“I’m always trying not only to read about the women of the past, but to put them back on the record,” she says. Hansard, the transcripts of Parliamentary debates, is a good place to do so. In a nod to the geographical site of her title, given in Theresa May’s 2019 resignation honours, her maiden speech in the House of Lords referenced the 19th-century Sheffield poet Mary Hutton, whose thoughts on poverty and human rights aligned her with the Chartists.

Natalie Bennett grew up in a Sydney suburb in the 1960s and 1970s “where the cultural highlight of the week was mowing the lawn”. But she could read by the time she was four, and in high school spent more time in the playground with Herodotus than with the other kids. “My parents had me very young; none of their friends had children. And because of my rather snobby grandmother, I wasn’t allowed to play with other children in the street,” she says. There was no television at home until Bennett was 11, so books – and the past – were her escape. She vividly remembers an exhibition of Chinese burial wares featuring

Bennett as Green Party leader in Liverpool, April 2015. Photo: Chris Philips

Bennett as Green Party leader in Liverpool, April 2015. Photo: Chris Philips

characters carved on ox-bones, and was “really into archaeology”. As an early teen, “my teacher wrote the famous phrase on my report card, ‘Natalie would be better off if she paid more attention to the living and less to the dead.’”

Europe seduced Bennett with its material history – but her upbringing in Australia inspired something else. Studying agriculture was partly the result of meeting and romanticising “amazing big farm families” on her early rural holidays. But in her third year at Sydney University “it became obvious to me that Australian farmers are not so much farming the soils as mining them”. She also studied philosophy as a non-degree subject in her third year.

Journalism followed. Then came an assignment on a country paper about a biodynamic farm. “This guy went into his field in the middle of summer when, usually in Australia, you’d need a pickaxe to break the crust. He very casually turned it over with his shovel and it was full of worms and organic matter, just amazing soil. That gave me a glimmering that something different was possible.”

30 THE LONDON LIBRARY

“Environmentalism and feminism have this in common: it’s not enough to just win a battle and change a law”

If history and ecology are pillars in Bennett’s intellectual life, there is a third that runs through it all. “I became a feminist at age five,” she says. It was a reaction to her family and society’s conservatism – she was not even allowed a bicycle as a child and was, for many activities, told, “because you are a girl, not only should you not do this thing, you shouldn’t want to do it”.

Bennett agrees that as women make up the majority of the world’s poor, they suffer most from environmental degradation. But there’s more that links women with climate issues. “I heard [British feminist] Sheila Rowbotham give a talk to launch her book Dreamers of a New Day: Women Who Invented the 20th Century [in 2010], saying that in the 1970s, as feminists, we thought there was progress. But we learned that you have to go back and fight the same battles again and again. Look at abortion in the US at the moment. Environmentalism and feminism have this in common: it’s not enough to just win a battle and change a law. You’ve got to change the system.”

Bennett was not much impressed by COP26 last year, where she says there were many more women in the climate conference’s alternative programming than at official events. But she saw progress on the UK’s latest Environment Bill, which passed in November, and is clearly energised by the Lords. “Technically, we don’t interrupt, but you can ask questions for clarification or correction. You sit there thinking, ‘Am I going to leap up and interrupt the minister and provoke a confrontation?’”

Her Library borrowing history suggests the demands of the Lords are less onerous than running a political party (and one with scant resources – at the height of the Green’s success, she had to rely on just one press officer for weeks).

Over the past 12 months she has taken out titles from the Science shelves on Natural History, Petroleum, Sea, Birds, Botany, Food, Butterflies, Insurance, Crime and Dreams. She likes the feel of the “vaguely joint endeavour” of being in the building: “I would spend my life here, happily.”

Nevertheless, a typical weekday for Bennett might begin with an allparty parliamentary group meeting – she co-chairs on Hong Kong and vice chairs many more, including Agroecology – then writing an online comment piece from the debate the previous night for outlets including The Ecologist and PoliticsHome, before the House begins sitting at three. There may be oral questions, on say, prison policy, then work on the day’s main bill happens between four and midnight. “Sometimes we have a dinner break,” she says.

This has not stopped her from completing the proposal for another book project. It will explore what a non-patriarchal, ecologically-minded system might look like beyond the “single-line axis” of socialism versus capitalism. “Basically, we have a complete political philosophy, and it’s really interesting that it doesn’t have a name. Green-ism? I don’t know. I’m still trying to work that out,” she says. It sounds like the women’s history book may stay on the back burner for a little while longer. •

31

“Hyperactive is an adjective that has been used about me quite a bit.”

CHANGING THE SYSTEM

Photo: Hanna Gabler

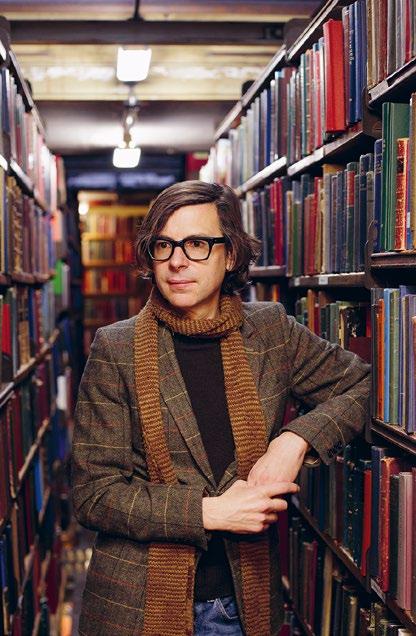

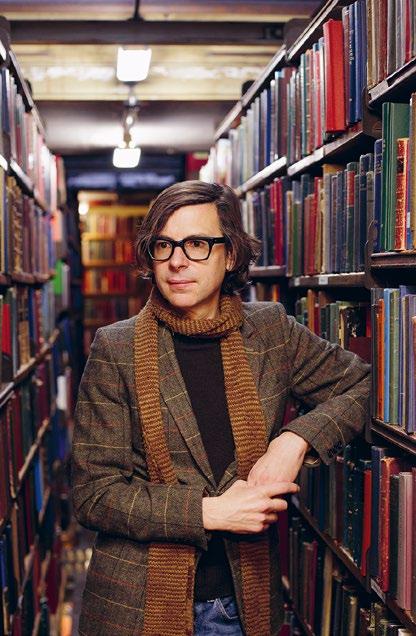

Travis Elborough in the Reading Room. Photo: Thomas Duffield

Travis Elborough in the Reading Room. Photo: Thomas Duffield

OUTSIDE THE BOX

Writers get inspiration from everywhere – for Travis Elborough, it is books from the Library’s shelves. Jessica Lack meets the hard-to-categorise author

33 §

At the turn of the millennium, Travis Elborough was working at the headquarters of Waterstones on an early version of its website, when he observed the new wave singer Gary Numan looking at a Smart car in the garage opposite. “Right there, I thought, ‘This is the future,’” he says, with a smile. The writer’s infectious enthusiasm for seemingly mundane connections has made him the author of several fascinating books on popular culture, among them Through the Looking Glasses: The Spectacular Life of Spectacles, A Walk in the Park: The Life and Times of a People’s Institution and The Long-Player Goodbye, a history of the LP.

When I ask him how he decides on a good subject, he says it usually starts by pulling a random book from the shelves of The London Library. The author has been a member for more than 20 years, having joined at the suggestion of his editor while writing his first book, an essential pocket guide to Friedrich Nietzsche, which he began after being made redundant from Waterstones. His second book, The Bus We Loved: London’s Affair with the Routemaster was inspired by a volume of photographs he found taken around 1907 from the top of the first motorised bus. “I wondered if the images were deliberately blurred to make it look like they were in motion,” he says.

Published in 2005 – just as the hop-on, hop-off Routemaster was being phased out, having been a London fixture since 1954 – the book is an affectionate look at a reassuring presence: “To travel on a Routemaster with the remnants of its original décor intact felt like being conveyed about the city in the lounge of an illustrious, if by now gone-to-seed, club.” With its mix of nostalgia and social history, it became something of a cult book and won praise from the writer Ian Sinclair.

Today Elborough is talking to me by video from his flat in Stoke Newington. Slightly built and wearing National Health specs in the Harry Palmer style (naturally the urbane and laconic spy features in Through the Looking Glasses), the author looks every bit the pop historian. As we talk, I notice a couple of Penguin paperback whodunnits on the shelf behind Elborough, with spectacles on their

front covers. Was Dorothy L Sayers also an inspiration? “Actually, they’re props for when I’m teaching over Zoom. They’re a lot more interesting than my kitchen,” he explains.

I imagine he’s an entertaining lecturer, freewheeling between gothic literature, synth pop and René Descartes. In the space of five minutes, we go from discussing the early-19th-century Scottish botanist John Claudius Loudon who was “bankrupted twice and lost an arm”, to the medieval mathematician Ibn al-Haytham, via a drunken night spent eating jam roly-poly and custard with actor Tom Baker. I learn that Elborough is named after Travis McGee, the Florida beach-bum detective created by pulp fiction writer John D MacDonald, a character who lives on a boat named The Busted Flush.

The author teaches creative writing at Westminster University where he advises his students to read old adverts in magazines. “Society is all there,” he says, and admits he is a devotee of the Periodicals section at The London Library.

34 THE LONDON LIBRARY

Winner of the Edward Stanford Travel Writing Awards Illustrated Travel Book of the Year 2020

Exploring the Topography shelves. Photo: Thomas Duffield

Exploring the Topography shelves. Photo: Thomas Duffield

“There was a period in history when anyone who had enough cash could write a guide book”

“Finding the most obscure things”: Elborough examines a book on the bridges of London.

Photo:

Thomas Duffield

His research has uncovered a smallpox hospital, a Cold War spy tunnel and the uninhabited Caribbean island of Redonda

“I spent a year looking at 200-year-old gardening magazines for A Walk in the Park.” Like Elborough’s other books, this entertaining history of our urban green spaces deftly navigates the subject’s evolution, in this case from medieval hunting grounds to today’s green living rooms, while interweaving references to The Great Gatsby, the culture of sunbathing and the dystopian visions of novelist JG Ballard. Such dexterity can make Elborough’s books hard to categorise. Where, for example, does his Routemaster book sit? In it, the author ruminates on the relationship between the big red bus and the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein, a memory of watching Return of the Jedi and the harmonicaplaying bus conductor Duke Baysee. Travel, design, social history? He concedes this can sometimes be a problem. However, he cites the maverick cultural historians Michael Bracewell and Philip Hoare as inspiration. “They came to Birmingham University when I was an undergraduate and had this amazingly wide-ranging conversation that flitted from Edwardian London to punk to Goldie. It was just like what was going on in my head.”

In recent years, Elborough has been haunting the Topography section in The London Library’s basement. The collection was an invaluable resource while he was researching his Unexpected Atlas series, five books about vanishing, improbable and “untamed” places. Each is beautifully illustrated by a cartographer and features photographs of the world’s strangest places, from ghost towns to subterranean realms and architectural oddities. He uncovered a smallpox hospital and a Cold War spy tunnel, a chapel in a sheer cliff side and the uninhabited Caribbean island of Redonda, with its wonderful proxy court of idiosyncratic grandees.

He took inspiration from old guide books, many of which can be found on the shelves near the Library’s entrance. “There was this period in history when anyone who had enough cash and could travel could write a book, regardless of how poorly executed it was.” Some, he says, “contain incredible period prejudices”, not least about the English coast and his home town of Worthing, a place that he has besmirched in the past: “It is hard to grow up somewhere where everyone else has gone to die.”

37

OUTSIDE THE BOX

In 2010, Elborough published Wish You Were Here, which celebrated the egalitarian nature of UK seaside towns, with their bandstands and boarding houses and charted their decline as holiday-goers abandoned the changeable weather for package holidays in sunnier climates. Like Through the Looking Glasses, which was inspired by the author’s life as a spectacle wearer, there is an element of autobiography to the book.

Not that he is a particularly nostalgic person, “but I sometimes wish I had my pre-internet brain back”. The London Library is a refuge from the rabbit holes of the digital world. “For a time, I used an old word processor as a way of avoiding being online, but then my smartphone would ring and…” he throws up his hands in resignation.

Currently the author is working on a film about London’s Soho with Madness frontman Suggs, “although the progress has been somewhat hindered by lockdown”, and looking forward to the publication of his fifth Atlas book, (the fourth won the Edward Stanford Travel Writing Awards Illustrated Travel Book of the Year in 2020). He is also relieved to be back in the Library after the upheavals of

the pandemic. “It’s great to be able to take books home with you, but I really missed just wandering along the shelves and finding the most obscure things.”

What’s the strangest book he’s ever found? “It’s called Motopia ,” he says, without missing a beat. Written by architect Geoffrey Jellicoe in 1961, it reimagines London as a series of motorways. “The city just disappears under a network of spiralling dual carriageways,” he says, “I find it odd that a man who lived in a very nice Georgian house on Parliament Hill was quite prepared to obliterate it all.” And Elborough is off again, making connections between Jellicoe and the novelist Alan Sillitoe, and revealing the little-known fact that Bram Stoker came up with Dracula in a nightmare after eating too much dressed crab with Henry Irving. •

Atlas of Forgotten Places: Journey to Abandoned Destinations from Around the Globe by Travis Elborough is out now (White Lion)

For Elborough, the Library is a refuge from the rabbit holes of the digital world. Photo: Thomas Duffield

Great Literary Friendships

Twenty-four literary friendships in succinct, structured entries – ‘A fun spin on literary analysis’ and the ideal gift for your literature-loving friend.

9781851245826

February, HB £16.99

Alexandra Lloyd

An overview of the White Rose anti-Nazi resistance group. Includes translations of the group’s pamphlets by students at the University of Oxford.

9781851245833

February, HB £15.00

British Dandies: Engendering Scandal and Fashioning a Nation

Dominic Janes

The scandalous story of fashionable men and their clothes as a reflection of changing attitudes not only to style but also to gender and sexuality.

9781851245598

March, HB £30.00

Tutankhamun: Excavating the Archive

Published in association with The Griffith Institute.

Edited by Richard Bruce Parkinson

Fifty items present a vivid and first-hand account of the discovery of the tomb and give an intimate insight into one of the world’s most famous archaeological discoveries.

9781851245857

April, HB £30.00

The Great Tales Never End: Essays in Memory of Christopher Tolkien

Edited by Richard Ovenden & Catherine McIlwaine

This collection of essays by worldrenowned scholars, together with family reminiscences, is essential reading for Tolkien scholars, readers and fans.

9781851245659

June, HB £40.00

Defying Hitler: The White Rose Pamphlets

Janet Phillips

FREE CATALOGUE

| ORDER

9 – 23 March 2022

publishing@bodleian.ox.ac.uk

FROM bodleianshop.co.uk NEW BOOKS The MUST see dance event of the Spring 8 companies over two weeks

Lucinda Childs & Philip Glass, Lyon Opera Ballet

Brigel Gjoka, Rauf “RubberLegz” Yasit & Ruşan Filiztek created in collaboration with William Forsythe Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker/ Rosas Katerina Andreou Christian Rizzo Boris Charmatz Gisèle Vienne SERAFINE1369

EVENTS

Yoga, short-story construction and the most scholarly song lyrics make appearances in the Library’s spring programme

3 March

Jewish Book Week 2022: Lehrer, Dylan and Cohen

At Kings Place as part of Jewish Book Week, music journalist and author of Genius & Anxiety Norman Lebrecht is joined by Harry Freedman, Barb Jungr and Andrew Robinson to discuss the lyrics, lives and legacies of three of the greatest – and most scholarly – songwriters of all time.

8.15pm, in person at Kings Place

17 March

Reverse Engineering

Chris Power, Irenosen Okojie, Jessie Greengrass, Sarah Hall and Jon McGregor are contributors to an innovative new anthology of short stories. They reveal the processes, instincts and ideas behind the construction of their perfect shorts. In partnership with Scratch Books.

7.30–8.30pm, in person and online

18 March 2022

Yoga for Writing

Stretch both body and mind in the early morning quiet of the Reading Room with Stella Duffy, a qualified yoga instructor and award-winning writer whose workshops are a unique combination of both practices.

7.30–9.00am, in person

40

Short story contributors in Reverse Engineering on 17 March, clockwise from top left: Chris Power, Irenosen Okojie, Jessie Greengrass, Jon McGregor, Sarah Hall. Photos: Eva Vermandel, Awakening/Getty Images, Andrew Eaton/Alamy, Antonio Olmos, Nadav Kander

24 March

The Young HG Wells

Claire Tomalin discusses her new biography of HG Wells – himself a former Library and English PEN member. It is a fascinating portrait of a man driven by curiosity and desire for reform, whose imaginative worlds still inspire today.

7.30–8.30pm, in person and online

1 April

Write

& Shine: People & Place

The session takes inspiration from the work of Rebecca West, the novelist, historian, critic and former Library member. Writer Gemma Seltzer will offer writing prompts on how we can tell stories of a place through its people and characters.

7.30–9.15am, online

7 April

The R.A.P. Party

@ The London Library Inua Ellams brings his exhilarating live literature phenomenon the R.A.P (Rhythm and Poetry) Party back to the Library for an evening of hip-hop-inspired poems and favourite hip-hop songs.

7.00–9.30pm, in person

15 July

Write

& Shine: Memory

Celebrate the work of author and Library member Edna O’Brien with this writing workshop. O’Brien wrote about her home country of Ireland in sensual detail, and this session uses recollection as a tool to create a sense of place in writing.

7.30–9.15am, online

13 May 2022

Write

& Shine: Landscape & Imagination

Start your day with a burst of creativity in this virtual writing workshop led by Gemma Seltzer. This session takes former Library member Daphne du Maurier – born on this day in 1907 – as inspiration.

7.30–9.15am, online

For more information on London Library events, go to londonlibrary.co.uk/whats-on or consult the fortnightly e-newsletter

41

Claire Tomalin discusses HG Wells on 24 March

MEET A MEMBER

Roving journalist Pádraig Belton takes Library books everywhere

It’s been five years since I joined The London Library. I’d moved away from Oxford and needed to fill the void left by the Bodleian and the 24-hour library at Trinity, which I’d made a lot of use of at 3am. The Library has become my spiritual home. I guess I’m a “collector” of the hidden desks – I remember finding an utterly secluded one at the top of the Back Stacks and thinking, “I’m never leaving it.”

I’ve made a living writing global business and technology features for the BBC for the past 22 years. I also write for the Guardian, and I’ve written five short books on international economics and intellectual history for Routledge, which the Library wisely doesn’t hold. I’m just finishing a doctorate in politics, which I’ve been getting through at the pace of a slug.

The Library’s books have accompanied me wherever I’ve been. Middlemarch came to Ukraine, Parade’s End to China, The Picture of Dorian Gray to Siberia and I’ve been working my way through Proust everywhere else. I started out as a foreign correspondent after some terrible advice from John Simpson, the veteran war correspondent. I asked him what he would do in my shoes, and he said, “I’d get on a flight to Ukraine, ring Broadcasting House and start pitching, because they don’t have anyone out

there.” It turned out the flights were cheap because no one in their right mind wanted to go there. But I did it and that’s how my career started.

I live between a hotel in Dublin and a succession of sofas in London. The London Library’s Back Stacks are my heaven of constancy. I come straight from Heathrow with too many bags and deposit them by the hat rack, which is glorious, and so are the Member Services team.

During lockdown, the Library posted endless books to me in Dublin – Betty Friedan, Patrick Leigh Fermor and others – to keep me as sane as I could be. I also joined the St John Ambulance as a volunteer. When I’ve been in London, I’ve been changing into my uniform, like a geekier Clark Kent, in the second-storey lavatories.

I love The London Library like a lover, one I’m very faithful to. Whenever I go into the Reading Room, I remember that George Smiley has a favourite desk here in the Le Carré novels. Once, amid the grilles, a woman’s brooch fell through two floors and ended up in a bin beside me. I didn’t ever get her name. But, I thought, I’ve always wanted to meet someone that way. •

As told to Deniz Nazim-Englund

Pádraig Belton outside his “spiritual home”

42

Spanning genres and age groups. (Left to right) Daniel Janes, Anastasia Taylor-Lind, Gaar Adams, Lianne Dillsworth, Mónica Ibarra Parle, Krystle Zara Appiah. Photo: Theo Lowenstein

Spanning genres and age groups. (Left to right) Daniel Janes, Anastasia Taylor-Lind, Gaar Adams, Lianne Dillsworth, Mónica Ibarra Parle, Krystle Zara Appiah. Photo: Theo Lowenstein

Bennett’s maiden speech in the House of Lords referenced the 19th-century poet Mary Hutton.

Photo: Hannah Gabler

Bennett’s maiden speech in the House of Lords referenced the 19th-century poet Mary Hutton.

Photo: Hannah Gabler

BY KATE RAWORTH (2017)

BY KATE RAWORTH (2017)

BY STEVE KEEN (2021)

BY STEVE KEEN (2021)

Bennett as Green Party leader in Liverpool, April 2015. Photo: Chris Philips

Bennett as Green Party leader in Liverpool, April 2015. Photo: Chris Philips

Travis Elborough in the Reading Room. Photo: Thomas Duffield

Travis Elborough in the Reading Room. Photo: Thomas Duffield

Exploring the Topography shelves. Photo: Thomas Duffield

Exploring the Topography shelves. Photo: Thomas Duffield