£5.95

LADY ANTONIA FRASER

June 2022 Nº 53

Inua Ellams Katy Hessel

2 THE LONDON LIBRARY 4 MAY – 4 SEP 2022 dpg.art/reframed #reframed RE FRAMED: The Woman in the Window Supported by The Elizabeth Cayzer Charitable Trust Official Paint Partner The Observer The Daily Telegraph ★★★★★ ★★★★★ ★★★★ The Times

DISPATCHES D. Welcome from the Director 5 D. News 7 Updating the shelfmarks New literary partnerships Flash fiction competition winner Saving energy in the Stacks D. Corner of the Library 11 D. From the Archive 12 FEATURES F. A Life in Books 14 Lady Antonia Fraser, the eminent historian, reveals her childhood favourites and what’s on her Kindle F. Literature, Remixed 22 Inua Ellams on revisiting Sophocles, and hosting hip-hop at the Library F. What Katy Did Next 30 Women are central in Katy Hessel’s fresh take on art history

L. Events 40 Workshops, book launches and more L. Meet a member 42 Historical fiction writer A J West CONTENTS 12 22

LAST WORDS

FOR THE LONDON LIBRARY

Josephine Noti

Head of Marketing and Communications

Elaine Stabler

Marketing Executive, Media and Communications

Felicity Nelson

Membership Director

The London Library

14 St James’s Square

London SW1Y 4LG

(020) 7766 4700

magazine@londonlibrary.co.uk

EDITORIAL: CULTURESHOCK

Contributors

Rachel Potts, Alexander

McFadyen, Deniz Nazim-Englund

Photography

Pål Hansen (cover), Ameena Rojee, Dale Weeks

Head of Creative

Tess Savina

Art Director

Alfonso Iacurci

Designer

Thomas Carlile

Production Editor

Claire Sibbick

Publisher

Phil Allison

Production Manager

Nicola Vanstone

Advertising Sales

Cultureshock

(020) 7735 9263

The London Library Magazine is published by Cultureshock on behalf of The London Library

© 2022. All rights reserved.

Charity No. 312175.

Cultureshock

27b Tradescant Road

London SW8 1XD

(020) 7735 9263

cultureshockmedia.co.uk

@cultureshockit

The views expressed in the pages of The London Library Magazine are not necessarily those of The London Library. The magazine does not accept responsibility for unsolicited manuscripts or photographs. While every effort has been made to identify copyright holders, some omissions may occur.

ISSN 2398-4201

WELCOME

A home for all

We always enjoy celebrating the creativity of our members in the pages of our magazine so it is a real pleasure to share this issue with you.

Inside, poet and playwright Inua Ellams speaks about using the Library to bring together the worlds of hip-hop and literature through his wonderful R.A.P (Rhythm and Poetry) Parties, while the art historian and broadcaster Katy Hessel outlines how the modern mediums of social media and podcasting have helped her to highlight women artists throughout history. Her new Art/Lit Salon is now a regular feature of the Library events programme. Lady Antonia Fraser tells us how the Library has been an essential source of inspiration and creative energy throughout her long and hugely successful writing career, citing the Library’s postal loans service as her most vital resource, and we meet novelist A J West who tells us how much faster he can write when working here. It is tremendous to know that the Library is playing its part in helping to inspire and support so much exciting work – long may that continue.

I would also like to take this opportunity to thank everyone who supported our Library Fund appeal over the last year. Thanks to your generous donations we have raised £87,000 towards the installation of new, energyefficient lighting in various parts of the Stacks. We depend on your support in order to keep improving the Library’s facilities and are delighted to be able to move ahead with this important upgrade. •

Philip Marshall, Director

5

UPDATING THE SHELFMARKS

Feminism and Gender & Sexuality collections updated

The Library’s unique classification system is renowned for its browsability and for the opportunities it creates for discovery. In place since the Library’s establishment, the system requires occasional changes to keep it up to date.

Following on from the removal and redistribution of S. Women last year, the Library has reviewed the shelfmark S. Sex to seek out and redistribute titles that are better placed in the newly devised S. Gender & Sexuality and S. Feminism class marks.

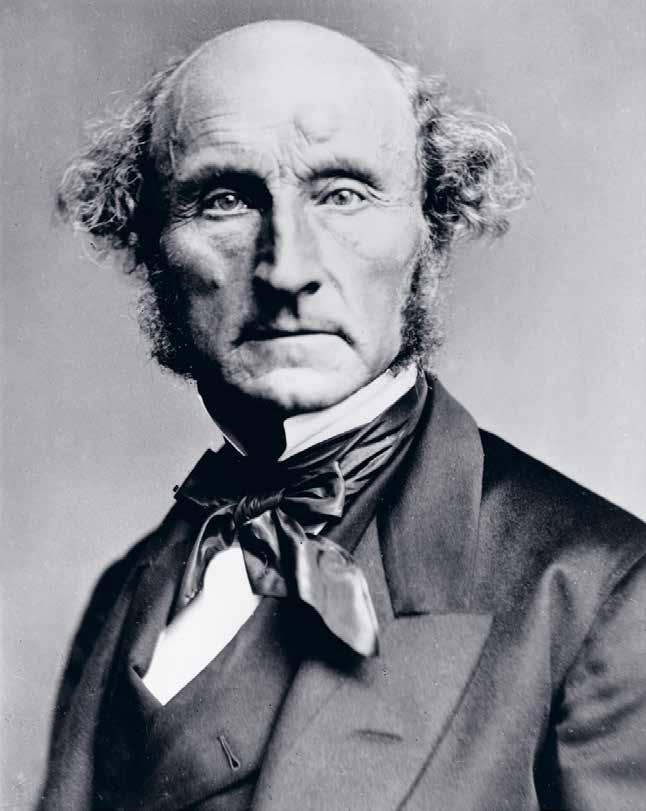

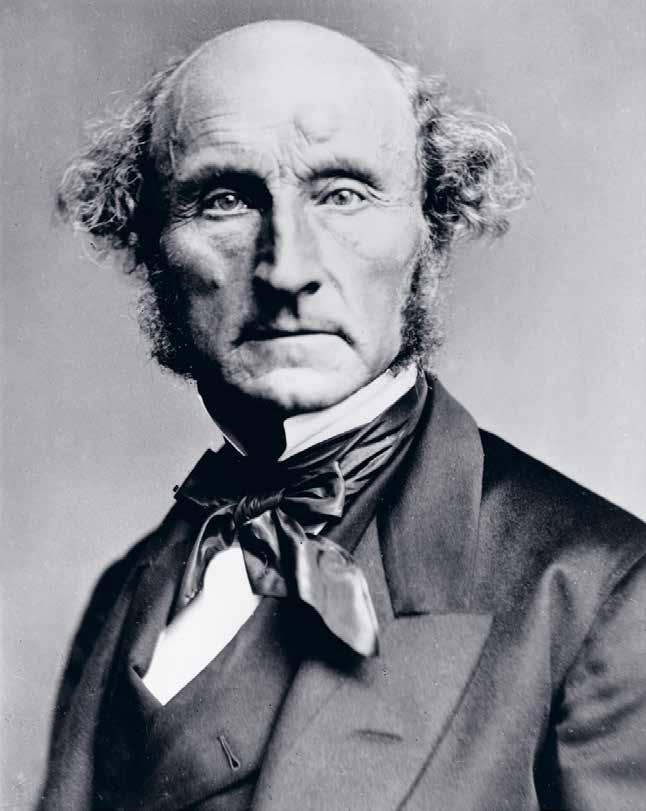

All 640 of the books in the S. Sex shelfmark were reviewed last year. Nearly half of the total works (254)

were redistributed, with 61 going to S. Feminism, and the remainder to S. Gender & Sexuality. Among them was The Subjection of Women, by Library founding member John Stuart Mill, which has now been moved to S. Feminism.

Upon its publication in 1869, The Subjection of Women and its advocacy for equality between the sexes caused considerable controversy. Co-authored by Harriet Taylor Mill, John Stuart Mill’s wife, it argued that sex inequality limits the development of society by confining women to the home, and proposed that this tradition had no place in the modern world. •

7 NEWS

Library founding member John Stuart Mill and his wife Harriet Taylor Mill, co-authors of the 1869 essay The Subjection of Women Photos: London Stereoscopic Company, c.1870; National Portrait Gallery, c.1834, artist unknown

8 THE LONDON LIBRARY

From left: Cal Flyn, winner of The Sunday Times Charlotte Aitken Young Writer of the Year award; Andrew Holgate, Literary Editor at The Sunday Times ; shortlisted authors Megan Nolan, Caleb Azumah Nelson and Rachel Long; Sebastian Faulks CBE FRSL. Photo: Camilo Queipo

NEW LITERARY PARTNERSHIPS

The Library extends its reach to support new and diverse voices

The London Library has entered into exciting new partnerships with initiatives including the Jhalak Prize and the Women’s Prize for Playwriting to support and celebrate writing talent.

Among them is a three-year partnership with English PEN, announced in late 2021, to support the organisation’s work with exiled writers and international writers at risk. To date the Library has welcomed two at-risk writers into membership.

In March, the Library teamed up with the Women’s Prize for Playwriting, established in 2020. Karis Kelly won for her play Consumed, which explores four generations of Northern Irish women and will be staged in Belfast in 2023. Kelly donated a portion of the £12,000 prize to those affected by the war in Ukraine.

The Library also celebrated the 2022 Jhalak Prize in May, dedicated to championing books by British and British resident BAME writers. An event was held in the Reading Room, hosted by Library trustee Yassmin AbdelMagied, with addresses from judges Nii Ayikwei Parkes and Chimene Suleyman and readings from shortlisted authors. Graphic novelist Sabba Khan was awarded the Jhalak Prize, and children’s author Maisie Chan received the Jhalak Children’s and Young Adult Prize.

The Library’s partnership with The Sunday Times Charlotte Aitken Young Writer of the Year award also continued. Author Cal Flyn was named the winner in a ceremony at the Library in February, for Islands of Abandonment, an account of remarkable places around the world that have been reclaimed by nature. Flyn received £10,000 and two years’ Library membership. Shortlisted authors received £1,000 and one year of Library membership.

Through these partnerships, the Library is proud to welcome and nurture writing talent from a range of backgrounds and disciplines, underlining its status as one of the world’s key literary institutions. •

9 NEWS

FLASH FICTION COMPETITION WINNER

Writer wins £500 prize for micro fiction entry

The winner of the London Library’s flash fiction competition has been announced.

Responding to the theme, “How do you want to be remembered”, Frank McPherson claimed the top prize with his timely story: “For the Virtual Tour, click here”.

The competition was launched in the Autumn 2021 issue of this magazine by trustee Daisy Goodwin, who also donated the prize money. All members were invited to participate, and encouraged to think about their legacy and whether the Library could play a part.

A number of imaginative submissions were received, with the winner announced online and in the Library’s

end-of-year newsletter, along with the four runnersup. These were Roland Watson-Grant for his entry “Could hardly drive. Still moved people”; Sally Miles with “A laughing, bookworm aunt; she gardened”; Anne Louise Avery who wrote “Shelved idiosyncratically and referenced with style”; and Richard Hopton’s “Many completed sentences, some good behaviour”.

The Library would like to thank all members who entered the competition. •

To find out more about leaving a gift to the Library in your will, visit londonlibrary.co.uk/legacy

SAVING ENERGY IN THE STACKS

Donations fund the installation of eco-friendly bulbs

This year, almost £87,000 was raised towards the installation of an energy-efficient LED lighting system in the Library’s Stacks.

This will provide more than 1,000m of lighting –enough to cover the entirety of the Back Stacks and the St. James’s Building, and reduce the Library’s total energy use by 20%. It marks perhaps the single biggest change the Library can make to reduce its carbon footprint.

The Building and Facilities Management team are now trialling lighting systems to decide the best option for the Library and members. A key consideration will be striking a balance between preserving the Library’s historic charm and finding a system that is high quality, energy-efficient, and long-lasting. •

10 THE LONDON LIBRARY

Find out more and donate at londonlibrary.co.uk/support-us/donate-library-fund

CORNER OF THE LIBRARY

A touching time capsule carved into the steel roof beams of the Literature Stacks

Two months after the Library was bombed in February 1944, large parts of the building were still closed for repair. As with many institutions at the time, it was staffed by a new wave of female recruits, who had replaced men called up for active service. Some of these new staff members decided to write themselves into the fabric of the building. In a high-up corner of the Literature Stacks, a small lump of hardened putty records the names Joan, Kitty, Pearl, Liz, Anne, Win, Foo, Nora and Olga, incised into its

surface before it set. One of the culprits, Joan Bailey, continued working at the Library until the late 1990s, and became a source of wild and wonderful anecdotes during her 50-year career. One story recounts how, while standing on the Library roof to share a cigarette with a colleague, she was startled by a V1 flying bomb passing overhead. It came so close, she recalled, that she was able to feel the heat of its vapour trail on her face. •

11 Wartime staff

their

left

mark.

Photo: Dale Weeks

FROM THE ARCHIVE

A 1950s joining form for the artist Gluck shows that refusing to accept gender norms is nothing new

12 “I request you place my name before the Committee for Election at their next Meeting Signed: (Miss) H.

professional signature

Gluck,

Gluck”. Photo: Dale Weeks

Known for evocative portraits and still lifes, and subjects including lovers, flowers and rotting fish, the gendernonconforming painter Gluck became a Library member in 1950. Born Hannah Gluckstein in London in 1895, as an adult they rejected their forename and, except in unavoidable circumstances, refused to use a title such as “Miss” or “Ms”. On Gluck’s joining form, “miss” is in brackets, “Hannah” is reduced to a simple initial, but their shortened, self-given name is repeated twice.

They were born into a wealthy Jewish family and educated at St John’s Wood Art School from 1913 to 1916. By the early 1920s, they had shortened Gluckstein to Gluck, and photographs from the time show them in men’s clothing with short-cropped hair. They smoked a pipe, and only exhibited works in “one-man shows”.

Like all official documentation, The London Library’s joining forms have presented an opportunity for applicants to assert or establish an identity – when Virginia Woolf joined at the age of 22, she listed her occupation as “spinster”. They can also reveal something of applicants’ personal lives.

Gluck was nominated for membership by their lover, Edith Shackleton Heald (1885-1976), a journalist and former mistress of W B Yeats (Yeats, while not a member of the Library himself, doubtless borrowed books through his wife, Georgiana Hyde-Lees). The address noted on Gluck’s joining form is The Chantry House, Heald’s home in West Sussex, where the couple lived together from 1944 until Heald’s death in 1976 (Gluck died at the address two years later).

Gluck had many close relationships with women. In the 1930s they fell in love with the florist Constance Spry, who inspired a floral period in their work. One close friend and artistic collaborator was Romaine Brooks (18741970), an American artist known for her society portraits. The two worked together on paintings and photographs. Brooks’s 1923-24 oil portrait of Gluck shows the latter as self-possessed and highly androgynous – it is titled Peter (a Young English Girl), and is currently on show at the V&A museum in its exhibition Fashioning Masculinities: The Art of Menswear (until 6 November).

Nesta Obermer (1893-1984) was perhaps their greatest love, and the married playwright and philanthropist inspired Gluck’s most famous painting, Medallion (1936). The double portrait of the couple, which Gluck called the “YouWe” picture, has come to be viewed as an iconic lesbian statement.

In addition to the nickname Peter, Gluck was also known as “Darling Tim” to Obermer, and to at least one admirer they were “Dearest Rabbitskinnootchbunsnoo”. To their family, they were known as “Hig”, and to Heald they were “Dearest Grub”. The artist’s biographer, Diana Souhami, says that “to the art world, and in [their] heart, [they were] simply Gluck”, and on their joining form, “Miss” is in brackets, “Hannah” is reduced to a simple initial, but their shortened, self-given name is repeated twice. •

13

Gluck at work on a portrait in their studio in Hampstead, London, November 1932. Photo: Fox/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

“Joining forms have presented an opportunity for applicants to assert or establish an identity”

Lady Antonia Fraser at home in London

Lady Antonia Fraser at home in London

From Agatha Christie to serious history, and a building in St James’s Square: the acclaimed writer and biographer Lady Antonia Fraser tells Lara Feigel about her love affair with the written word

Photography by Pål Hansen

A LIFE IN BOOKS

15 §

The circumstances of Lady Antonia Fraser’s first foray into The London Library speak eloquently of her family dynamics. Her father was Francis Pakenham, the 7th Earl of Longford and a government minister under Clement Attlee, and he had sent her to return his books. He couldn’t do it himself, he said, because they were so late, but she was youthful and charming enough to be forgiven. She’d also need to be forgiven for his furious pencil annotations – in contrast, Fraser herself is a very light annotator of books she owns and lives in fear of accidentally marking one from the Library.

She could not have known then that she would one day become a Library Vice-President, but when she walked into the lobby from St James’s Square, it was love at first sight and she would soon be a member. Here she would find many of the books that would enable her to become the prize-winning author of more than 20 works of history and biography that are now much-borrowed from the Library’s shelves.

The combination of capability and haplessness in his instructions was typical of Fraser’s father. He was a major political figure (at one point during his years as a Labour minister, Fraser wrote grandly in her diary that he was going to “abolish Want”), but was incapable of keeping his buttons done up or making a cup of tea. Fraser describes her mother, a practically minded socialist feminist, as the “paterfamilias”, and it was she who carved the joints, drove the car and taught Fraser to read.

Their Oxford house was full of books – many from libraries. One in particular, H E Marshall’s Our Island Story: A Child’s History of England (1905) shaped Fraser’s childhood and provided her first encounter with her later biographical subjects, who have included Mary, Queen of Scots and Oliver Cromwell. Aged four, she read tales of martyrdom and courage that transformed 1930s Oxford into the landscape of the past. She was gripped by the story of Empress Matilda, a claimant to the 12th-century English throne. Walking past Oxford Prison, Fraser imagined herself as Matilda, dressed in white, escaping imprisonment by skating across the icy river.

Fraser was the oldest of eight children, so home was cheerfully chaotic, and she was grateful to have her own attic bedroom (“a cell in dimensions, but my own cell”). In it, she devoured history books but also became a rapacious reader of crime fiction and the historical romances of Georgette Heyer. “There comes a point in every friendship when I say: ‘Either you think Georgette Heyer is the greatest writer who ever lived or our relationship is over’,” she says, sitting on her sofa with me in the Notting Hill house where she brought up her six children and lived for 30 years with the playwright Harold Pinter.

16 THE LONDON LIBRARY

Fraser’s most recent book, published last year, explores the Victorian writer Caroline Norton, who campaigned for women’s divorce and custody rights (Orion)

Fraser in 1969, at her home in Holland Park, with the first edition of Mary Queen of Scots

Photo: Trinity Mirror/Mirrorpix/Alamy

Fraser in 1969, at her home in Holland Park, with the first edition of Mary Queen of Scots

Photo: Trinity Mirror/Mirrorpix/Alamy

“Aged four, she read tales of martyrdom and courage that transformed 1930s Oxford into the landscape of the past”

She asks if I like Heyer, and I have to admit I have never read her. Luckily, I am not evicted from the sofa. I am saved, perhaps, by having made friends with Fraser’s affectionate black-and-white cat Bella, who spends the interview moving between our laps, settling at points on my page of questions (apparently instructed by her mistress to do so).

Heyer was deemed appropriate reading by Fraser’s mother, but other popular writers were not. Enid Blyton and Barbara Cartland were banned, though Fraser secretly raided their cook’s stash of Cartlands. Later Fraser would define happiness as “arriving at Inverness airport and finding an Agatha Christie you haven’t read before”, and unhappiness as “finding one you had read before but that had been given a different title”.

There was weightier reading, too. She discovered Anthony Trollope, falling for Lady Glencora Palliser, his “tiny tousle-haired heiress”. And there was the Bible. Her father converted to Catholicism in 1940 and the rest of the family followed. He was never without a copy of the New Testament and they would all read Psalms, which she still loves (each child had to learn a verse to get their pocket money).

She enjoyed English lessons at school – first a boys’ prep school in Oxford (at which she was among a handful of girls), followed by a boarding school and then a convent – but was most enthusiastic about theatrical texts: she loved playing Lady Macbeth. History remained her great passion, but her mother told her to put down PPE on her university

18 THE LONDON LIBRARY

“With Harold Pinter, reading was part of their shared intimacy”

application, despite Fraser not knowing what it was. A scholarship was forthcoming, but when she finally found out it would involve studying philosophy and economics, she was horrified. Thankfully, she was allowed to transfer. This combination of obedience and faithfulness to her own ideals is typical. I find during our interview that she is wonderfully, almost conspiratorially, compliant, but also that she directs very precisely what is said. This seems to connect to her voracity as a reader: somehow she has always managed to combine loyalty to family traditions with a willingness to follow her own desires. Her two marriages were both filled with books. Her first husband, Hugh Fraser, was a Conservative politician, so she tended to read alone while he was at the House of Commons. With Pinter, whom she met in the mid-1970s and married in 1980, reading was part of their shared intimacy, except in the heady days of their first trip to Paris. She noted with amazement in her diary: “There is something very odd about the time we have spent together. I haven’t read a book. This is the first time probably since I learnt to read.” But they quickly settled in to reading together, with her on the sofa where we are sitting and him on the chair (now gone), to which she gestures several times during our conversation, conjuring him as a presence (he died in 2008). They read separate books, pausing to read passages aloud or even entire plays, including his works in progress. Following the success of her first major work, Mary, Queen of Scots, in 1969, she continued to research and write biographies of historical figures, including King Charles II and the wives of Henry VIII. But she also began to write crime fiction. Her first Jemima Shore novel was set in the convent where Fraser had gone to school, and Shore herself was portrayed as a writer of Fraser’s age in an affair with a married man, which mirrored aspects of her early days with Pinter. Now she wonders about writing a final

Jemima Shore novel, in which Dame Jemima is in her 80s (Fraser is 89) and solves mysteries with the sharpness and charm of her creator.

It is clear that Fraser will continue to write for as long as she can, and that she reads as hungrily as ever. She is pleased with her Kindle, which enables her to have the complete works of Agatha Christie and of Dickens with her at all times, and has just finished rereading Great Expectations. When not writing, she campaigns to promote a love of reading as patron of the Give a Book charity. Our interview is followed by lunch, which Fraser would share with Pinter every day in the double-windowed dining room. In those days she would rush down with the chapter she had just written and present it to him exuberantly, hopeful that it was the best historical writing since Macaulay. He would read it and assure her that it was, while noting that she had used the word “sanguine” 45 times. “He adored the English language, he didn’t know history, and he was always encouraging – I miss it most terribly,” she says.

I am not invited to read the chapter she wrote on the morning of our interview, but I am permitted into the study where it was composed. It’s another dual-aspect room at the top of the house, full of pictures, with desks at each end piled high with books from Fraser’s beloved London Library. For years she scoured the shelves, and was especially impressed by the collection on the French Revolution, sometimes pausing to sit in the Reading Room. Now she gets books posted, and finds the speed with which they arrive remarkable. “I couldn’t imagine life without it,” she says. •

Lara Feigel is a Professor of Modern Literature and Culture at King’s College London and is the author of five works of cultural history and one novel, The Group. Her new book, Look! We Have Come Through! – Living With D H Lawrence is out in August

20 THE LONDON LIBRARY

“She has always managed to combine loyalty to family traditions with a willingness to follow her own desires”

ANTONIA FRASER’S GREATEST HITS

Brilliant books from across her career

MARY QUEEN OF SCOTS (1969)

Fraser’s first major biography was an international hit and awarded the 1969 James Tait Black Memorial Prize. In The New York Review, the respected historian and reviewer John Kenyon wrote, perhaps not entirely in jest: “Lady Antonia Fraser is young, beautiful, and rich, an earl’s daughter married to a busy and successful politician, the mother of a large family; yet she has surmounted all these handicaps to authorship to produce a first-rate historical biography.”

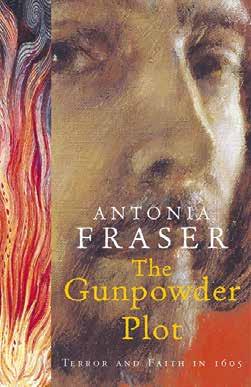

THE GUNPOWDER PLOT: TERROR AND FAITH IN 1605 (1996)

Fraser’s account of the attempted terrorism at the Houses of Parliament in 1605 is approached with her usual storytelling flair, boasting “a sense of pace and tension worthy of a John le Carré novel” according to The Sunday Telegraph. Covering one of England’s most famous historical episodes, facts about which are remarkably shaky, it was awarded the St Louis Literary Award and the Crime Writers’ Association Non-Fiction Gold Dagger.

THE WEAKER VESSEL: WOMAN’S LOT IN SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY ENGLAND (1984)

Departing from her lives of famous figures, this ambitious social history looked at midwives, courtesans, abbesses and more. Fraser was inspired to begin research in the 1970s, while working on her Oliver Cromwell biography, and drew on varied contemporary sources, from diaries to legal documents. Among the earliest mainstream books to piece together unwritten women’s stories, it was awarded the 1984 Wolfson History Prize.

MARIE ANTOINETTE: THE JOURNEY (2001)

A famous line about cake is only one of the untruths that Fraser aims to redress in this biography of the last queen of the Ancien Régime, who came to the throne aged 14. The book was adapted into a film by Sofia Coppola in 2006, focusing on the monarch’s dreamy teendom and seen today as a cult classic. The director said “I wanted to adapt Antonia Fraser’s book because her attitude was so different from other biographies about Marie.” Rachel Potts

21 SKY’S THE LIMIT

It all started with a library for the award-winning playwright and poet

LITERATURE,

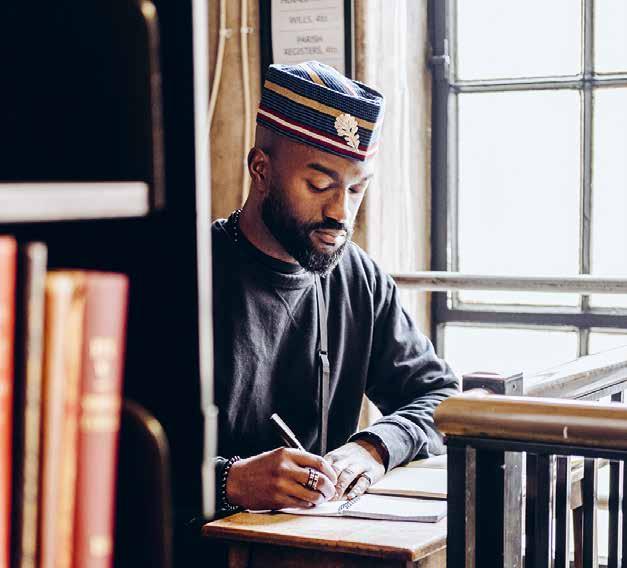

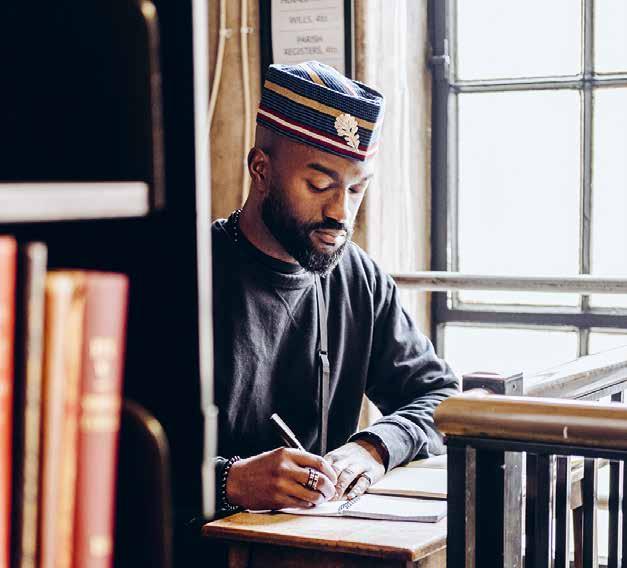

Acclaimed playwright and poet Inua Ellams joined the Library two years ago – and realised it was the ideal place for a hip-hop party, finds Kadish Morris

Photography

by Ameena Rojee

23 §

REMIXED

When Inua Ellams was 12, and newly arrived in England from Nigeria, he tested the boundaries with his parents by bringing home books from the library that he thought they wouldn’t approve of.

“I discovered Terry Pratchett’s Pyramids. The cover was this figure dressed as a ninja assassin, riding a camel with a half-naked woman dangling off his arm – but my mother didn’t care because of how thick the book was.”

Now a renowned playwright and poet, his rebellious edge, easy humour and his family’s love of books have served Ellams well. “We’d even read the Argos catalogue,” he says. He was born in 1984 in Jos, a city in the North Central of Nigeria, to a Christian mother and a Muslim father. The rise of militant Islamist group Boko Haram in the mid-1990s put the family in jeopardy, and so they moved to the UK. Libraries were a revelation. “It baffled me that I could go into this building and, because of a laminated card, they would trust me to take home as many books as I wanted. It was ridiculous.”

This helped to kickstart his career. As a young man he was unable to legally work due to his immigration status. “I began reading my way through everything, from French philosophy to graphic design, then I started designing flyers for poetry events and they invited me to come on stage.”

The rest is history. Since his first poetry pamphlet, Thirteen Fairy Negro Tales, was published in 2005 Ellams has become a major literary presence as a writer and performer.

His one-man show drawing on his own experience of immigration, The 14th Tale, won a Fringe First at Edinburgh in 2009; he combined poetry and graphic art in the 2012 show Black T-shirt Collection, since optioned for a TV series. His debut collection, The Actual , was published in 2020 and shortlisted for the Derek Walcott Prize for Poetry. Its 55 poems, written on his phone, explore everything from the British Empire to the rapper Tupac Shakur.

Elected a fellow of the Royal Society of Literature in 2018, Ellams might be best known for his work in theatre. His 2017 hit play, Barber Shop Chronicles, inspired by audio recordings made in Africa and described by The New York Times as “a group portrait of black men”, sold out the National Theatre twice and went on a world tour. In his adaptation of Chekhov’s Three Sisters in 2019, also for the National, its protagonists were relocated from Russia to Nigeria during the Civil War of 1967-70.

But Ellams says he’s not interested in trailblazing. “In the West there’s a need for the poet to always be new and to be groundbreaking. That is a riff on capitalist ideals – a pyramidic structure.” As a proud communist and hiphop fanatic, his work is all about community and union. “When I write, I’m not trying to be new. I remix poems. I acknowledge what comes before and figure out what I have to say and join this chorus of writers, which started from the caveman right up to the Shakespeares, the Toni Morrisons and the Maya Angelous of the world.”

24 THE LONDON LIBRARY

“One of my mentors told me that you have to write about yourself, you have to risk something”

25

Ellams’ reimagining of Three Sisters by Chekhov is set in Nigeria during its 1967-70 Civil War. Sarah Niles, Racheal Ofori and Natalie Simpson perform at the National Theatre. Photo: The Other Richard/ArenaPAL

Ellams’s R.A.P Party events combine music with poetry that is “affiliated with or in step with aspects of hip-hop culture”. Photo: Dale Weeks

“When I write, I’m not trying to be new. I acknowledge what comes before”

Ellams first came to the Library to do a live reading for an event with Malika’s Poetry Kitchen, the writers’ collective founded in Brixton by poets Malika Booker and Roger Robinson and which supports voices outside the mainstream. He was struck by the potential of the Reading Room as a place to hold one of his R.A.P Party events. Standing for Rhythm and Poetry, they have been combining live poetry and music since 2010, everywhere from the Southbank Centre to literature festivals in the UK, Ireland and Lagos, and are, he says, “like a house party, but with awkward speeches”. Their popularity suggests something more inviting. Ten poets read works that are “affiliated with or in step with aspects of hip-hop culture. The readings might be about songs directly, or reference a lyric. After that, we play two tracks attached to the poems.” He admits people often say they’ve never been to an event like it. “They talk about simplicity, which is one of its strengths; the equation works. It has this innate rebellious energy.”

In addition to enjoying “the taboo of holding a hiphop night in a library,” Ellams says, he values the space as somewhere “to meet people to discuss literature” and to write and study. Contemporaries such as Jay Bernard, Terrance Hayes, Caroline Bird, Rebecca Perry, Jack Underwood and Caleb Femi inspire him. Though whenever he’s really stuck, he goes to the American poet and novelist Stephen Dobyns, whose works are characterised by a cool realism. “He wrote the strangest of poems. But the most moving as well.”

Ellams admits his own approach to writing has shifted, and is now not as intensely political. “I used to think I wasn’t interesting, and that the world was spiralling so out of control I could throw a pen and hit something that’s wrong with it, so I’ll just write about that. But one of my first poetry mentors, Roger Robinson, told me that you have to write about yourself. You have to risk something.”

Yet ideas about injustice, culture and histories that have affected him still underpin his work. He’s working on a new play for the National, set in pre-colonial Nigeria, about the last days of British rule. Research has included

27

LITERATURE, REMIXED

interviews with academics from across Africa and revealed that “[colonisers] demanded books be rewritten in Boko [a Latin-script alphabet]. Those that weren’t translated were destroyed – they burned them and said ‘history begins here henceforth’.” In the Library’s archives of The Times from 1865 to 1902 he found “some of the things that were happening in Nigeria had been debated about in parliament”. Though it’s too early to reveal precisely how, these records have fed into the plot of the play.

Ellams is also working on an adaptation of Sophocles’ tragedy Antigone, written around 441 BC, which is partly about faith. In the aftermath of civil war, two brothers have died, and their sister Antigone, aligning herself with the wishes of the gods, refuses to accept an edict from her uncle King Creon that one be denied funeral rites. She is entombed in a cave, and hangs herself before Creon decides to free her.

At first, Ellams was unsure about taking on the commission, but he started to see it as a story about a woman versus the patriarchy. “I thought, Antigone is asked to stand up to the wastemen around her, politically and socially. When I saw it through that lens I thought the only way I could feel close to it would be if I removed the Greek gods and replaced them with a faith that I felt was under scrutiny: Islam.”

Part of Ellams’s research involves simply reading the news. When we speak he has just read an article about the government’s plans to deport refugees to Rwanda. “My version of Antigone is about the immigrants and Muslims who aren’t wanted in this country, who have to change so much of their culture. They almost feel like they are baggage around this country’s neck.” The play, he says, feels like it’s writing itself. •

Ellams’s retelling of Antigone is at the Regent’s Park Open Air Theatre, 3-24 September. Kadish Morris is a poet and critic

28 THE LONDON LIBRARY

A scene from Barber Shop Chronicles at the National Theatre. Photo: Tristram Kenton/The Guardian

in The Times

Hessel

Room

WHAT KATY DID NEXT

The curator and broadcaster Katy Hessel is on a mission to restore women to the art canon

Photography by Ameena Rojee

31 §

I’m not very good at being interviewed,” Katy Hessel laughs – an infectious sound that might explain why she is so good at drawing people out of themselves for her popular podcast The Great Women Artists. During her career to date, Hessel, 28, has interviewed artists such as Cornelia Parker, Lubaina Himid and Phyllida Barlow, as well as prominent scholars, curators and critics including Griselda Pollock, Helen Molesworth and Olivia Laing. She has curated exhibitions, presented for the BBC and is an arts consultant and adviser, matchmaking artists with galleries.

In September, Hessel publishes her first book, The Story of Art Without Men , which aims to redress Ernst Gombrich’s seminal 1950 book The Story of Art. Intended as an insight into “at least a fraction of the work by non-male artists who have contributed to ‘the story of art’”, its tone is crystallised in a quote from 1649 by Artemisia Gentileschi: “I’ll show you what a woman can do.”

This also neatly sums up Hessel’s all-consuming passion. We’re sitting in a cafe in Dalston, not too far from where she grew up in Crouch End. She was introduced to art at age six when her eldest sister started to take her to exhibitions at the V&A, the National Gallery and the newly completed Tate Modern.

It was the early 2000s, and London’s art scene was flourishing – Hessel recalls being struck by exhibitions by Anish Kapoor, Rachel Whiteread and Louise Bourgeois. “You couldn’t not be amazed by it,” she recalls. “I remember the first time I got on the Tube by myself, when I went to see Chris Ofili at Tate Britain. I would get up early so I could go and watch Christian Marclay’s The Clock [a virtuoso video work that splices existing footage of clocks to match its 24-hour length] at White Cube before school.”

Hessel went on to study a BA in art history at UCL, but her feminist awakening came later. A turning point was seeing portraits by American painter Alice Neel. “I couldn’t believe she wasn’t recognised, she was incredible,” says Hessel. “Then I realised there was this whole ecosystem of artists who had been largely ignored because of their gender.” An arresting 1973 portrait by Neel of the art historian Linda Nochlin – whose 1971 essay Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists? inspired Hessel’s Instagram handle and podcast – and her daughter Daisy features in the introduction to The Story of Art Without Men

In 2015 Hessel visited Frieze Masters, the historical section of the annual Frieze Art Fair, and didn’t see a single work by a woman. “I was shocked, I literally couldn’t sleep that night,” she says. Out of her frustration, the Instagram account @thegreatwomenartists was born: a platform for provoking conversation about the lack of representation of female artists and in particular “making it accessible for my generation”.

32 THE LONDON LIBRARY

a good start”

Hessel’s first book is born from her popular podcast and Instagram account. Reviews posted by her publisher so far include Tracey Emin’s comment: “It’s a long way before the balance is truly redressed but this is

“I realised there was a whole ecosystem of artists who had been largely ignored because of their gender”

Katy Hessel in the Library Stacks

Katy Hessel in the Library Stacks

36 THE LONDON LIBRARY

The Only Blonde in the World, 1963, by Pop artist Pauline Boty.

Photo: The estate of Pauline Boty/Tate

At that point Instagram was mostly a platform for sharing selfies and personal images, but Hessel saw an opportunity. “It was free, and I could do it on my phone. It was the ultimate millennial approach to writing,” she says. Bringing the conversation about gender representation in the arts to a wide audience is still at the core of what she does. “I’m jumping on the shoulders of amazing art scholars who have built this history for us, but I always want to be in tune with my generation and how they consume knowledge.” The account’s popularity soared, and now has more than 275,000 followers.

The London Library has become a fundamental research source because of its “incredibly rich selection of art books”, says Hessel. “I’ve found titles on all sorts of artists who have been overlooked. And it’s located close to all the galleries.”

She has keenly engaged with the Library community, including its events programme. “I loved interviewing Jennifer Higgie last year about her book – and I’m very excited that she will interview me about mine at the Library this autumn.” The Australian author of The Mirror and the Palette, about female self-portraits through history, is a former editor of Frieze magazine, and has been similarly mining the history of female artists.

It was Hessel’s podcast, launched in 2019, that cemented her reputation. She enlisted a friend to teach her the basics of audio recording, then taught herself how to edit. Her first guests included Juno Calypso, a fêted young British photographer, and Es Devlin, the celebrated stage designer. She also spoke to Zoé Whitley, the Chisenhale Gallery director (and then Tate curator) about the AfricanAmerican artist Betye Saar, and hosted Tate Modern director Frances Morris, “who I knew because I met her once at customs at JFK airport”.

Now in its seventh series, the podcast highlights artists and their work, but also the critics, curators and scholars who support them. “I enjoy interviewing the glitzy artists, but also the people who have been doing the work behind the scenes,” says Hessel.

In The Story of Art Without Men, she also gives space to many voices, spanning 1500–2015 and 350 artists. “It’s about the unexpected,” she says, “the juxtapositions between schools that were happening simultaneously but don’t get the airtime they deserve.” One of her favourite chapters covers the post-war period, in which she touches on women such as Pop artist Pauline Boty, who died of cancer aged 28 in 1966. “Her life feels so contemporary, it feels like mine. The relevance of these artists now is just incredible.”

37 WHAT KATY DID NEXT

“Instagram was free, and I could do it on my phone. It was the ultimate millennial approach to writing”

Now, when being categorised by their gender is something many female artists push back against, does Hessel think it is still a helpful strategy? “That’s an interesting one,” she says. “I am all-inclusionary – ‘without men’ can encompass so many other genders, but it should draw you to something.” She points out blockbuster survey shows in recent years, from Minimalist Agnes Martin at Tate Modern in 2015, to Lee Krasner, the Abstract Expressionist, at the Barbican in 2019, to the Venice Biennale this year, in the main venues of which women artists outnumber men by nine to one. These prove, Hessel says, that women have always contributed to cultural shifts and key movements.

She also mentions the exhibition Louise Bourgeois: The Woven Child, staged this spring at the Hayward Gallery and the first to focus exclusively on the artist’s use of fabric and textiles. “It’s also about appreciating the work she did in the last 20 years of her life – and you never used to get that with women, ever. That’s where we’re going now. The conversation is really happening.” •

The Story of Art Without Men is published 8 September (Penguin). Charlotte Jansen is the author of Photography Now and Girl on Girl: Art and Photography in the Age of the Female Gaze

38 THE LONDON LIBRARY

Works by female surrealists (from left) Ithell Colquhoun, Remedios Varo, Edith Rimmington, Dorothea Tanning and Leonora Carrington in The Milk of Dreams , the 59th International Art Exhibition in Venice this year.

Photo: Marco Cappelletti, courtesy of La Biennale di Venezia

EVENTS

Hone your writing skills and celebrate newly published work at the Library this season

14 July

THE PEN ACKERLEY PRIZE 2022 IN PARTNERSHIP WITH ENGLISH PEN

Now in its 40th year, the PEN Ackerley Prize is awarded annually for a literary autobiography of excellence, in memory of the writer and editor J R Ackerley. Join the shortlisted authors in conversation, chaired by biographer and historian Peter Parker, followed by the winner announcement.

6.45pm onwards, in person and online

21 July

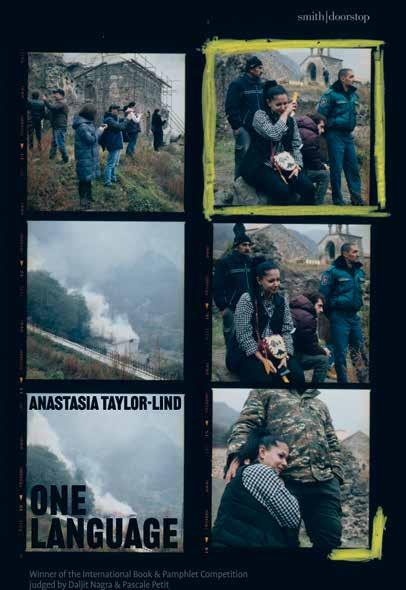

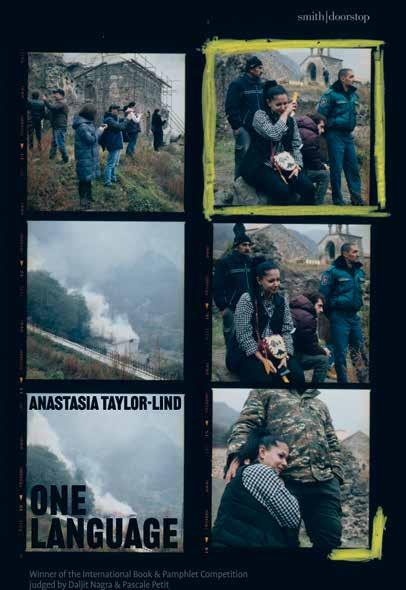

BOOK LAUNCH: ONE LANGUAGE BY ANASTASIA TAYLOR-LIND

Photojournalist, award-winning poet and London Library Emerging Writer Anastasia Taylor-Lind, who is currently reporting from Ukraine, launches her new book, One Language. This concise, complex collection draws on first-hand experience of war in the Donbas region to explore how damage is generated and perpetuated.

6.45pm onwards, in person and online

15 September

SEX AND THE CITY: AMBER MEDLAND AND MEGAN NOLAN IN CONVERSATION

15 July

WRITE & SHINE

An inspiring, 90-minute virtual writing workshop live from the Library. Author Gemma Seltzer leads a session called Memory, taking the work and ideas of author Edna O’Brien as inspiration.

7.30am – 9.15am, online

Amber Medland and Megan Nolan discuss their stunning debut novels Wild Pets and Acts of Desperation, both sharp, searing depictions of what it is to be young and lost as women navigating sex, mental health, creativity and the city. They will be in conversation with author and critic Chris Power.

7:30pm – 8:30pm, in person

40

From top: Amber Medland. Photo: courtesy of the author One Language by Anastasia Taylor-Lind, published by Smith|Doorstop

16 September

WRITE & SHINE

Make the most of the morning with a virtual workshop delivered live from the Library by author Gemma Seltzer. In a session called City Life, Country Life, the work and ideas of Cold Comfort Farm author Stella Gibbons are taken as inspiration.

7.30am – 9.15am, online

22 September

R.A.P. PARTY @ THE LONDON LIBRARY

Poet and playwright Inua Ellams brings his R.A.P (Rhythm and Poetry) Party, an exhilarating live literature phenomenon, back to the Library for an evening of hip-hopinspired poems and favourite songs.

7.00pm – 9.30pm, in person

29 September

THE STORY OF ART WITHOUT MEN

Katy Hessel of The Great Women Artists Instagram and podcast discusses her new book, The Story of Art Without Men with Jennifer Higgie, the novelist, art critic and former editor of Frieze. Described as “necessary and urgent”, Hessel’s revisionist history of art shines a light on female creativity and the way it has shaped and enriched our world.

7.30pm – 8.30pm, in person

Members receive discounts on many London Library events. For more information about the latest events, scan the QR code below, or visit londonlibrary.co.uk/whats-on

41

From top: Katy Hessel co-hosts the Library’s first Art/Lit Salon 28 April 2022; Inua Ellams at a R.A.P Party in The London Library, 7 April 2022

MEET A MEMBER

Emerging novelist A J West found truth is stranger than fiction when he first walked the Stacks

My debut novel was inspired by a true story, which I read while working as a TV newsreader and reporter in Belfast. A Magician Among The Spirits is Harry Houdini’s account of his exploits debunking spiritual mediums. Of course, I had no idea then that the book would change my life.

I went on to publish the gothic historical novel, The Spirit Engineer, in autumn 2021. It’s about William Jackson Crawford, one of the foremost scientific investigators of spiritual mediums of his day, who took his own life in 1920, most likely having suffered a mental breakdown after a discovery about the young medium, Kathleen Goligher.

After The Spirit Engineer gained some success, I was instructed by my agent to write a second book at doublequick pace. My husband and I live in a small studio flat and, after two years of lockdowns, I knew I couldn’t spend another minute staring out of the same window. That’s when I discovered the Library and, thanks to the support of a dear friend, managed to sign up as a member.

Since then, this building has allowed me to research and write at a pace I didn’t think possible, and people-watch at the same time. A few Library members have even inspired characters in my new book; all complimentary, of course.

There was one particularly strange occurrence on my very first visit, when I found myself lost, as all new members should, high in the towers, searching for nothing in particular and wondering if I might find some of the books I had used to research Crawford.

It was a particularly gloomy day, the light through the windows barely reached the shelves, which were so tightly pressed together I quickly became disorientated. Turning at the top of some stairs on the sixth floor, I stumbled and found myself staring directly at three small, black books, side by side. There on their spines, in golden lettering, was the name: W J Crawford. I don’t believe in the paranormal, but I knew then that this was going to be a very special place for me indeed. •

42 A J

West.

Photo: Dale Weeks

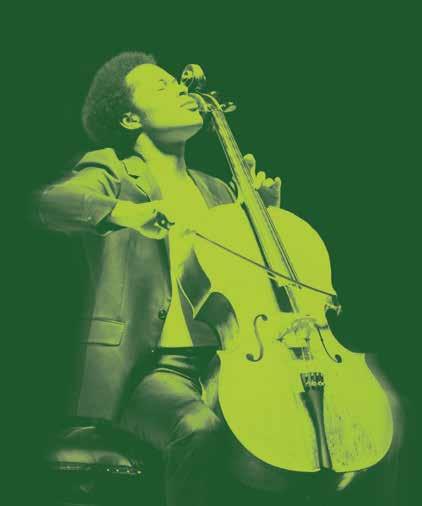

SanttuMatias Rouvali

Víkingur Ólafsson

Yuja Wang

Anna Clyne

Víkingur Ólafsson

Yuja Wang

Anna Clyne

London

Book now: philharmonia.co.uk 0800 652 6717

Sheku KannehMason

season highlights at the Royal Festival Hall

Lady Antonia Fraser at home in London

Lady Antonia Fraser at home in London

Fraser in 1969, at her home in Holland Park, with the first edition of Mary Queen of Scots

Photo: Trinity Mirror/Mirrorpix/Alamy

Fraser in 1969, at her home in Holland Park, with the first edition of Mary Queen of Scots

Photo: Trinity Mirror/Mirrorpix/Alamy

Katy Hessel in the Library Stacks

Katy Hessel in the Library Stacks

Víkingur Ólafsson

Yuja Wang

Anna Clyne

Víkingur Ólafsson

Yuja Wang

Anna Clyne