WEIGHED DOWN

BY KYLIE CHAU AND MARLENA ROHDE

BY KYLIE CHAU AND MARLENA ROHDE

BY SIERRA SUN

BY SIERRA SUN

“WE NEED THIS TO STOP!”

ACCOLADES:

NSPA Pacemaker Top 100, 2018 NSPA Print Pacemaker Finalist, 2011 & 2014 NSPA Online Pacemaker, 2012 NSPA Print Pacemaker, 2007 & 2011 NSPA All-American, 2009 NSPA First Class Honors, 2007 NSPA Web Pacemaker, 2007 CSPA Gold Crown

Editors-in-Chief Chloe Chon Kelcie Lee Marlena Rohde Opinions Editor Chloe Chon Sports Editor Roman Fong Art Managers Darixa Varela Medrano Elise Muchowski

Photographers Kahlo Friel Asay Malena Cardona Kylie Chau Katharine Kasperski Lauren Kim Reina Lee Ava Rosoff

Business Managers Yi Luo Adrienne Nguyen Primo Pelczynski

Social Media Managers

Juliane Dabi Erin Guo Gianna Ou Aaliyah Español-Rivas Miyabi Yoshida Advisor Eric Gustafson

News Editors

Angela Chen Kelcie Lee

Columns Editors Aaliyah Español-Rivas Dylan Twyman

Multimedia Editors Libby Bowie Marlena Rohde Yeshi-Wangmu Sherpa

Reporters

Isadore Diamond Clarabelle Fields Maya Law Niyati Mandhani Marshall Muscat Victoria Pan Evan Powers Laura Reyes Sierra Sun Illustrators Joey He Charon Kong Katey Lau Hugh McDonald Danica Yee Emily Yee

Web Managers

Roan Rafter Joanne Zeng Researcher Saw Nwe

As a result of the $3.6 million budget cut from last school year, our journalism program was cut. For tunately, the Lowell Alumni Association (LAA) and Parent Teacher Student Association (PTSA) donated $900,000 to fund elective courses, including two journalism classes. This was a temporary solution that has allowed The Lowell to continue to produce content through print, online, and social media outlets. Without elective funding from the city or state, electives are overlooked, and schools are in dan ger of losing the abundant benefits that these classes provide.

Classes like journalism are unique in creating student experiences that cannot be taught in conventional classes at Lowell. City and state govern ments need to create policies to fund elective programs to ensure students have access to these educational oppor tunities.

On Nov. 8, 2022, California cit izens voted on state propositions, one of which was Prop. 28, which guarantees arts and music education for K-12 pub lic schools. Prop. 28 overwhelmingly passed with over 64 percent of voters in support of it. However, this proposition excluded elective courses that don’t fall under the visual performing art (VPA) category, including journalism.

Some electives may be brought back at Lowell due to Prop. 28, while several will not, due to not being categorized as an art or music class. Although Lowell’s architecture and photography courses have been cut for the 2022-2023 school year, these VPA classes have the possibility of being revived due to Prop. 28. Unlike these VPA classes, the Yearbook class was cut and will not receive benefits from Prop. 28, with Yearbook teacher Christian Ferrey stating that he doesn’t know if there will be a

Yearbook class for the 2023-2024 school year. While journal ism received benefits from the PTSA and LAA temporarily, it also is not supported by Prop. 28 to secure funding for the coming years.

Journalism is one of the electives at Lowell that pro vides unique benefits, like being entirely student-run. Our classroom is essentially a newsroom, with frequent meet ings and brainstorming sessions. We have a photo backdrop, and desks set up in a way that is like no other at Lowell. In stead of lectures or lessons, we have discussions, one-on-one work time to edit articles, photo-essay critiques, and suggestions for spread designs being yelled across the room. When something occurs that requires breaking news coverage, reporters are leaving class to rush to the event. Pho tographers are immediately taking and editing photos, editors are coaching reporters through interviewing on the spot, and other staff members listen to recordings and transcribe interviews word-for-word. With every protest, walk-out, and admin decision being different, experience is gained to foster new skills. As a staff, we’ve found that you don’t need conventional classroom style teaching in order to learn.

As of now, we can still produce the newsmagazine you are holding be cause of the generosity of the LAA and PTSA. But it is not feasible for the LAA and PTSA to give $900,000 every year to support programs like journalism, making the future of our publication uncertain. Students cannot be deprived of the opportunities journalism classes bring to education, making it imperative that SFUSD offi cials, as well as city and state elected officials, create policies that will fund more electives.

The Lowell is published by the journalism classes of Lowell High School. All contents copyright Lowell High School journal ism classes. All rights reserved. The Lowell strives to inform the public and to use its opinion sections as open forums for de bate. All unsigned editorials are opinions of the staff. The Lowell welcomes comments on school-related issues from students, faculty and community members. Send letters to the editors to thelowellnews@gmail.com. Names will be withheld upon request. We reserve the right to edit letters before publication.

The Lowell is a student-run publication distributed to thousands of readers including students, parents, teachers, and alumni. All advertisement profits fund our newsmagazine issues. To advertise online or in print, email thelowellmanagement@gmail.com. Contact us: Lowell High School 1101 Eucalyptus Drive San Francisco, CA 94132, 415-759-2730, or at thelowellnews@gmail.com.

City and state governments need to create policies to fund elective programs to ensure students have access to these educational opportunities.

Dear readers of The Lowell,

In November, 27 staff members from The Lowell went to St. Louis, Mis souri to attend the National High School Journalism Convention. At the conven tion, The Lowell was awarded the National Scholastic Press Association’s (NSPA) Pacemaker 100 Award, which recognizes the top 100 high school publications in the nation. We are honored to be a small part of The Lowell’s century-long award-winning history. Thank you to the PTSA, LAA, parents, and all those who have supported The Lowell at bake sales that made this trip possible.

We had an incredible time exploring St. Louis, talking to other high school journalists from around the country, and learning about different subjects from social media content to journalism ethics. We hope that this enriching expe rience comes through in this issue and content to come.

But the future of our journalism program is not a guarantee.

The cover story of our March 2022 issue, “Cuts to the Community,” ex plored the immediate effects of SFUSD budget cuts on students and teachers, in cluding the journalism program initially being cut. The feature story in this issue, “Overcrowded, Understaffed, and Overwhelmed,” dives into the long-term effects that we’ve observed as a result of those cuts. In our editorial, “Take Journalism Off The Chopping Block,” we reflect on how our journalism program was cut and stress the importance of funding Lowell’s electives.

Editors-in-Chief, Chloe Chon, Kelcie Lee, and Marlena Rohde

BY NIYATI

BY NIYATI

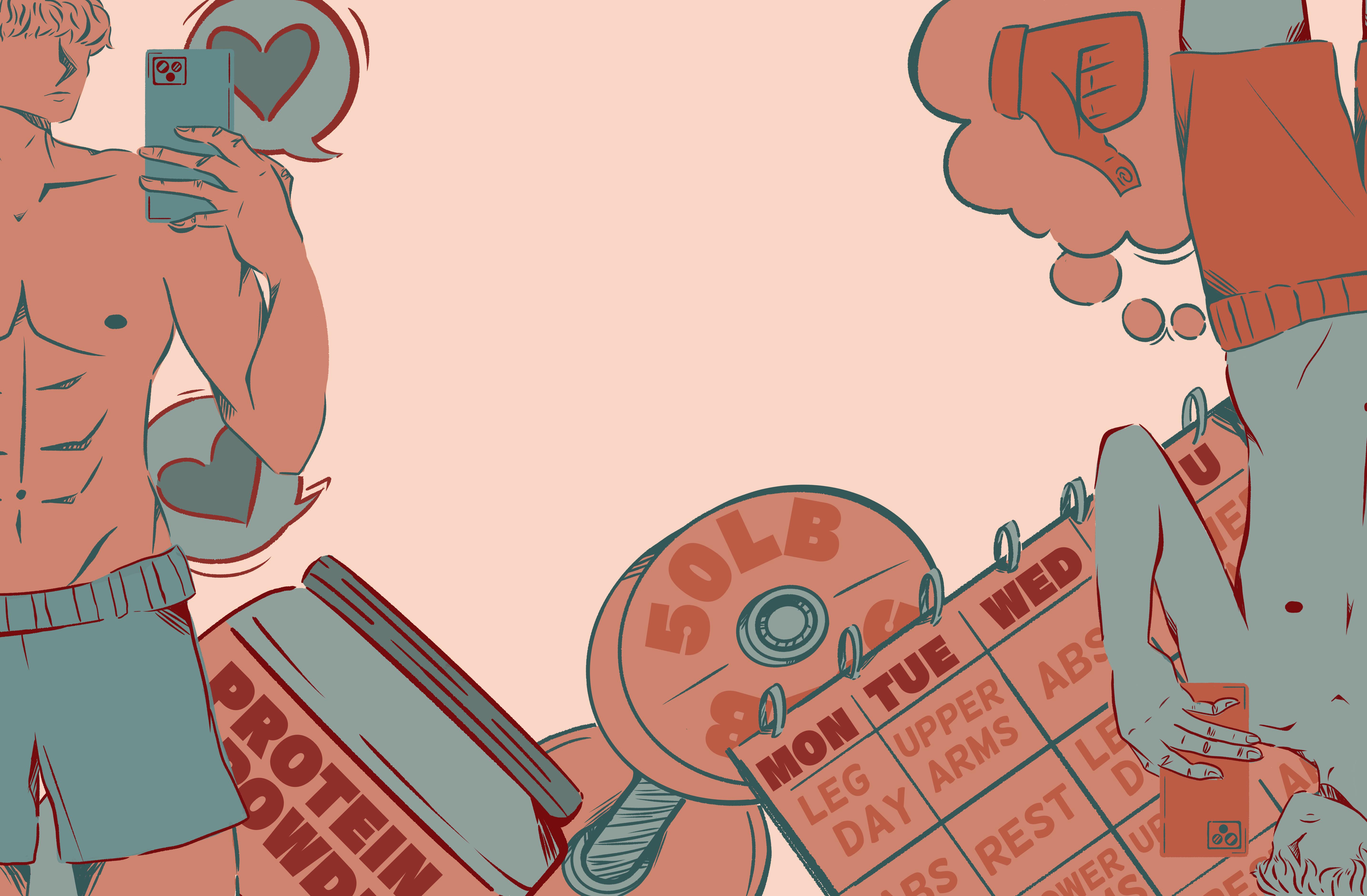

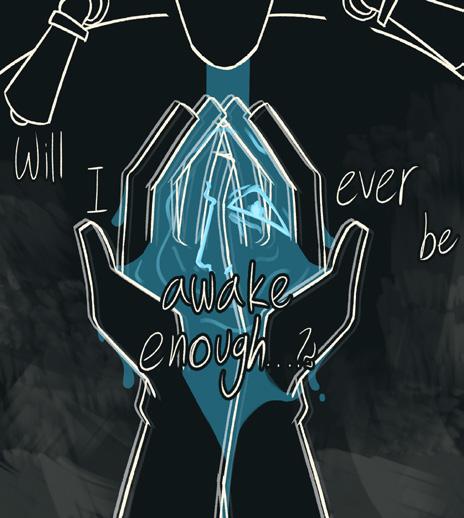

Senior Caleb Leung walks out of the gym tired yet satis ed, hav ing li ed a new milestone weight, one he couldn’t have imagined li ing just a month or two ago. As Leung opens TikTok to post his new person al record, he sees a video of another man li ing an unbelievable amount of weight. Impressed, he scrolls through the other man’s pro le, seeing months and months of progress

condensed into just a few videos. He frowns as he puts his phone away, ex citement over his new personal record erased. Leung contemplates whether he should do one more set, each passing second feeling like wasted time.

Going to the gym is a hobby rising in popularity among teens, espe cially teenage boys. While going to the gym yields many physical and mental health-related bene ts, one of its potential negative consequences is body dysmorphia, a mental condition that involves an unhealthy percep tion of one’s body. Body dysmor phia is primarily associated with females, accentu ated through pop culture and unreal istically high beauty standards. However, body dysmorphia af fects males as well, of ten leading to similar behaviors like restric tions on diet and low self-esteem. Whereas girls su ering from this condition usually xate on thinness and see themselves as over weight, boys are most

likely to focus on adding muscle mass and see themselves as overly thin. As a result, the term muscle dysmorphia is o en ascribed to males su ering from this condition. Social media has created an additional outlet for gym culture to idealize muscularity and put pressure on boys to obsess over working out and bulking up.

Body image has been stereo typed as a female issue, causing it to be overlooked in men despite it being prominent among males. According to Dr. Jason Nagata, a pediatrician at UCSF specializing in eating disorders, the lack of attention to body image is sues has given boys more reason not to seek help or talk about it. “ ere’s already a stigma for anyone with body image issues or eating disorders regard less of their sex or gender,” he said. “But

“But boys and men with muscle dysmorphia have a double stigma because they’re both affected by this condition and they are an underserved population. That is even harder for them to talk about.”

Gym culture has risen in popularity among teenage boys, leading to an obsession with muscularity and body image issues.

boys and men with muscle dysmorphia have a double stigma because they’re both a ected by this condition and they are an underserved population. at is even harder for them to talk about.” Nagata pioneered the term “Bigorexia,” a nickname for muscle dysmorphia, which refers to the preoccupation with insu cient muscularity that can im pede peoples’ ability to function. is may lead to anxiety, depression, or eating disorders. According to a 2019 study, around one-third of teenage boys are actively trying to gain muscle mass, with one-fourth changing their diet or using muscle-enhancing supplements to do so.

While many teens go to the gym to improve their body image, do ing so results in the opposite for some individuals: further insecurity and in creased body dysmorphia. Leung began going to the gym to get bigger muscles, feeling indirect pressure from peers and himself to meet his high standards. Although his overall perception of his body has improved since he started li

ing, Leung feels like going to the gym intensi es pre-existing insecurities of thinness, largely due to impatience with muscle growth. “You go to the gym to improve yourself, but you don’t feel like you’re improving,” Leung said. “It’s a slow, long-term improvement, so when you go to the mirror the next day ex pecting to see something, you don’t see it right away.” According to Leung, this is what leads to the obsession to achieve muscularity and bulk, his de nition

of “perfect body,” and leads to “feeling like [you’re] not good enough for other people, and for [yourself].” He even tells himself he isn’t good enough to nd a source of motivation to li . “I put my self down on purpose and make myself want to go to the gym and work out even harder,” he said.

Many boys become obsessed with going to the gym. According to Nagata, some teens may become over ly dependent on the gym, speci cally those who experience body dysmor phia. “People who develop body dys morphia feel guilty if they’re not exer cising all the time, and it becomes an obsession,” Nagata said. To see serious results, Leung began overly dedicating his time to the gym; he changed his diet and began spending all of his free time working out. Leung believes there’s a healthy extent to that, but it can also go too far. “If you don’t have self-discipline, you get lost going to the gym,” Leung said. “You’re going to focus on the gym, which becomes your life, and you don’t have a life anymore.” is summer, he fell into the hole of weighing food and obsessing over calories, not letting him self enjoy anything else. He stopped going out with friends and found him self going through the same daily cy cle: gym, home, sleep and repeat. For Leung, being unable to go to the gym reminds him that people are working while he isn’t, which manifests in a feel ing of being undisciplined. “I feel disap pointed whenever I miss a day,” Leung said. “I feel like I’m going to lose all my progress in that one day.” Senior Za meer Maqsood’s routine is dependent on the gym, as it adds structure to his day. “Without that structure, everything falls apart,” Maqsood said.

Body dysmorphia o en causes disordered eating that can have extreme health consequences. Dr. Nagata works with patients who can’t eat out at restau rants or with their families because they can’t reach their nutrition goals. “It re ally leads to impairment in the quality of one’s life,” Nagata said. According to him, people with body dysmorphia don’t o en get enough nutrients to sus tain their exercise habits; if they’re not eating enough and are in the gym for

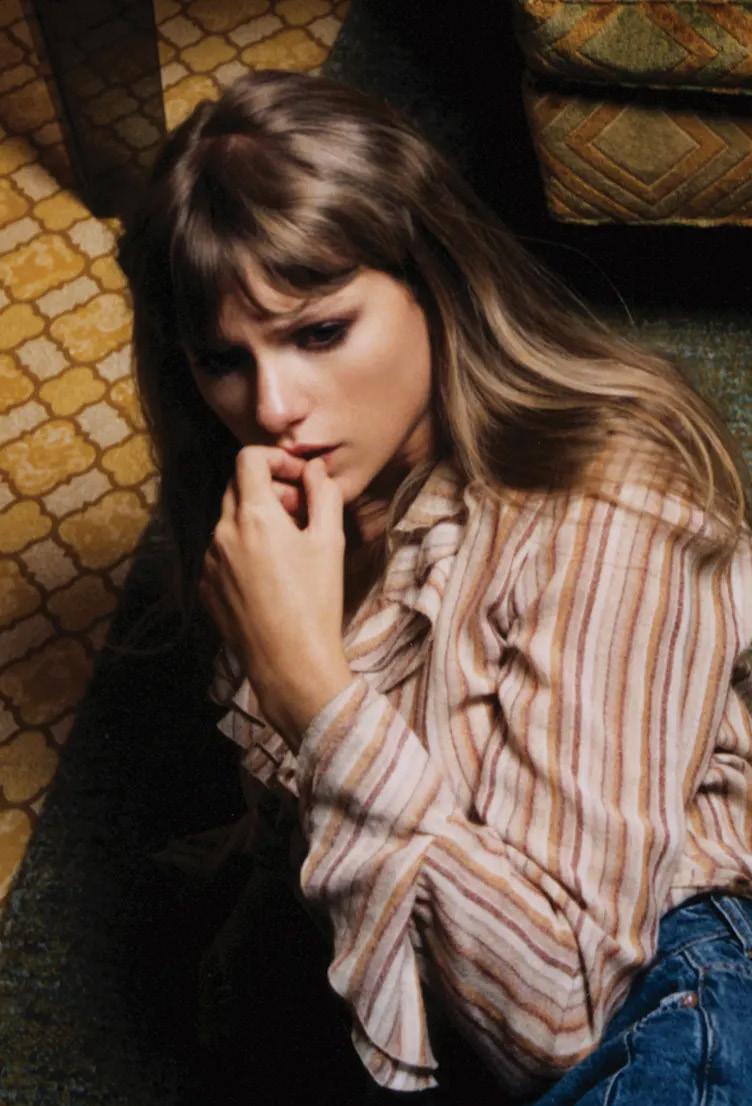

BY CHARON KONG, SPREAD DESIGN BY ELISE MUCHOWSKI“It’s a slow, longterm improvement, so when you go to the mirror the next day expecting to see something, you don’t see it right away.”

hours every day, they can get seriously sick and end up in the hospital. Accord ing to Leung, his progress of muscle gain slowed down because he isn’t on a strict, high protein diet anymore. Al though his past eating habits have im proved, Leung still struggles to forgive himself a er eating large amounts of unhealthy food, feeling guilty and lazy if he doesn’t immediately burn o the calories. “If I eat ve slices of pizza or something I… put myself down until I want to go to the gym again,” he said. With the accessibility and al gorithms of social media, boys are con stantly being exposed to content created by men and other teens with extreme muscularity. Junior Parker Higgins is used to seeing gym-related content; people posing, li ing, and even giving advice remind him that there are peo ple who have made more progress than him. “If I’m scrolling on Instagram and I see all these jacked dudes who look better than me, it makes me self-con scious,” he said. “So there’s a constant hunger to get better at weightli ing and go to the gym.” Nagata explained how

social media algorithms create a nega tive feedback loop, where engaging in gym-related content on social media leads to it consuming your entire feed, further promoting muscularity issues and driving interest higher. is follows a trend noticed by Nagata and other professionals, where teenagers who en gage on social media are more likely to be dissatis ed with their bodies.

Not only does social media target viewers with speci c content, but it also tends to portray working out through a positive and desirable lens. Leung noticed how social media creates an illusion of noticeable gym progress happening quickly. “With social media, you go into a TikTok page, and you see a whole year of progress,” Leung said. “But you scroll through it in ve min utes, making it feel like that progress only took ve minutes to get there.” Al though not an avid gym-goer, Senior Alex Blacker has also noticed the false narrative social media creates around gym progress. According to him, while some content has valuable aspects, much of it pushes people toward un healthy gym habits. “Especially on In stagram, there are things like, ‘You’re working out wrong. is is how you get six-pack abs,’” Blacker said. Blacker agrees with Leung on the harm of seeing years of progress condensed into a short clip or just a few posts. “People might think, I’m not gonna have to work out for that long. I just have to work harder, and so they’re gonna push themselves

“If I eat five slices of pizza or something

I… put myself down until I want to go to the gym again.”

too far,” Blacker said. Even for people who don’t go to the gym, not working out can cause insecurities around their body image by being exposed to aspects of gym culture through their friends and social media. Senior Dexter Shen doesn’t go to the gym, but is surrounded by friends and peers focused on improving their phy sique, which makes him feel pressured to do the same. Shen thinks there is an ideal body, and more importantly, he doesn’t have it. is becomes a barrier for him in both his mental health and personal life. Within hookup culture, Shen believes that having a “good” body is essential, causing him to feel unattractive and uncomfortable with showing his body when with a part ner. “I’m just not appealing if I’m not t,” he said. In addition to body image issues, Blacker views the gym as cre ating a toxic culture that equates body image to self-worth. “I feel like part of [going to the gym] has become nothing but a comparison between yourself and other people,” Blacker said. “It’s almost like the weights are just values, and how much you can li translates to your val ue.”

As an o en nor malized issue — that is, working out is good for you — solu tions to male body dysmorphia can be harder to nd with out support. According to Nagata, the rst step in dealing with body dysmorphia is to look for warning signs, from obsessions with weight gain or loss to excessive gym com mitment; many teens who struggle with muscle dys morphia don’t even realize it. Nagata stresses that reaching out to trusted adults and sup portive friends about any concerns is essential. Leung, who experienced a period of over-commitment to the gym, says it’s hard to snap out of that cycle. “You can try to x your own mindset, but it’s hard to do because it’s hard to see yourself doing something wrong,” Leung said. “From a rst-person per spective, you don’t see it as that big of an issue, but once you step back and see it from a third-person perspec tive, you realize that it isn’t the best lifestyle.”

Although Leung and Higgins have recognized their experiences with body dysmor phia, they have found support from within the gym communi ty, speci cally from others who have gone through similar body image issues. Higgins be lieves that a com mon goal of self-im provement can unite the community and foster

better mindsets that can counter inse curities, especially concerning body im age. “You’ll see huge bodybuilders, skin ny guys, and overweight people who have similar goals of getting healthier and having better habits,” Higgins said. According to Leung, receiving encour agement from adults and friends is the healthiest way to deal with dysmorphic conditions. “If you surround yourself with the right people who support you, you’ll eventually be okay with who you are and not get too deep into feeling like you aren’t good enough,” Leung said.

“It’s almost like the weights are just values, and how much you can lift translates to your value.”

After the first half of the day and a long wait in the lunch line, it is not uncommon for students to be met with school lunch that is too small, lacking in nu trients, or both. The lunch at Lowell tends to leave students wanting to go back to the lunch line to get another serving, and keeps them drained of energy for the rest of their classes. SFUSD needs to address our lunch’s small portion size. It is imperative that they make our lunches big enough to sustain students.

The portion size of school lunch is underwhelming and not enough to sustain high school students. Looking at the cafeteria lunch line is enough to reveal options that are unreasonably small in the eyes of our student body. It is gen erally agreed upon that 18 year olds need more food than 11 year olds, but according to SFUSD’s menu page, the menu at Lowell is shared by multiple middle schools. A.P. Giannini, a middle school also using the same menu, has portion sizes and menu plans are exactly the same as Lowell. There is no

way to distinguish between the food that is given to high schoolers and that which is given to middle school children. There is no reason that the same sized lunches given to pre adolescents should be served to students that are almost legal adults.

The actual numbers are incriminating. SchoolCafe provides nutrition information about SFUSD lunches. Most of the entrees are only around 350-400 calories, and meals only total up to around 500-550 when fruits, vegetables, and milk are included. For example, the hotdog is 305 calories, the

“There is no reason that the same sized lunches given to preadolescents should be served to students that are almost legal adults.”

the cheesy bread and tomato sauce is 368. A typical meal of a pupusa, milk, carrots, and an apple only amounts to 555 calories. However, the California Department of Education requires that high schoolers should have 750-850 calories a day for lunch. With these figures, it is undeniable that stu dents need to get more than what is being provided. In ad dition, to even hit the 500 calorie mark, Lowellites need to take milk, but many people do not or cannot drink milk, which cuts them off from a critical part of what little caloric value there is in the first place. Calories are a measure of energy, and we are not getting the amount of energy that is necessary to make it through each school day. If we want to have a more productive student body, it is essential that SFUSD presents us with a proper amount of energy. It would be too much of an exaggeration to say that all the food is nu trient deficient. The turkey sandwich carries a good amount of vitamins and food groups. Mixing this with the fruits or vegetables and milk makes a healthy meal. In addition, pasta dishes like the alfredo or spaghetti have 607 calories and 30 grams of protein, but also come with over 1000 grams of sodium and 10 grams of saturate fat. The pasta lunches may

Lowell’s lunch would be something that students can rely on. Unfortunately, there are very few meals like this and if the school district wants us to have a proper diet, they need to make sure we have options like this every day.

Portion size only scratches the surface of the prob lems. More issues arise with the lack of options for those with dietary restrictions or how individuals from low income back grounds rely on an inadequate school lunch, but the most dire concern right now is that the school simply does not provide enough food with its meals for any student.

The health of students should be a priority for the school and that starts with proper lunches. At the moment, the amount of food in our lunch is not enough. Lowell needs to almost double the size of our lunches in order to provide a healthy level of nutrition for our school.

PHOTO-ILLUSTRATION BY MARLENA ROHDE

AND DARIXA VARELA MEDRANO

ILLUSTRATION BY DARIXA VARELA MEDRANO

PHOTO-ILLUSTRATION BY MARLENA ROHDE

AND DARIXA VARELA MEDRANO

ILLUSTRATION BY DARIXA VARELA MEDRANO

PHOTO BY AVA ROSOFF

PHOTO BY AVA ROSOFF

ILLUSTRATION BY DANICA YEE

PHOTO BY MALENA CARDONA

ILLUSTRATION BY DANICA YEE

PHOTO BY MALENA CARDONA

Impressionism was an art movement during the late 19th century that emphasized the depiction of emotion, fluidity, and movement, rather than realism. We asked our photographers and illustrators to work together to create pieces in an impressionistic style, highlighting fluidity and emotion. By setting the photos next to each other, we show the contrast between impressionism and realism in the world around us.

ILLUSTRATION BY EMILY YEE

ILLUSTRATION BY CHARON KONG

SPREAD DESIGN BY MARLENA ROHDE

ILLUSTRATION BY EMILY YEE

ILLUSTRATION BY CHARON KONG

SPREAD DESIGN BY MARLENA ROHDE

By Maya Law, Victoria Pan, and Laura Reyes

By Maya Law, Victoria Pan, and Laura Reyes

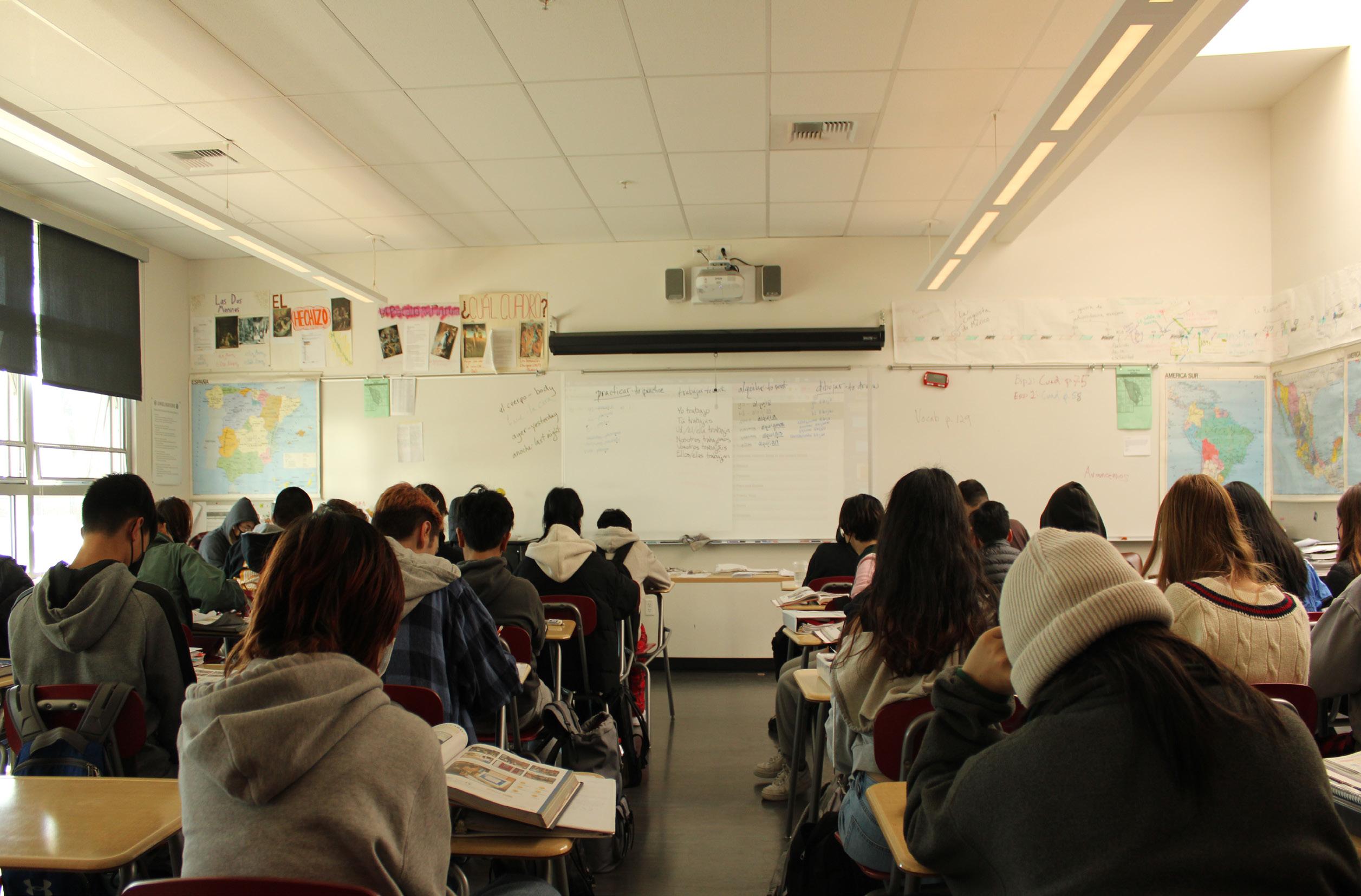

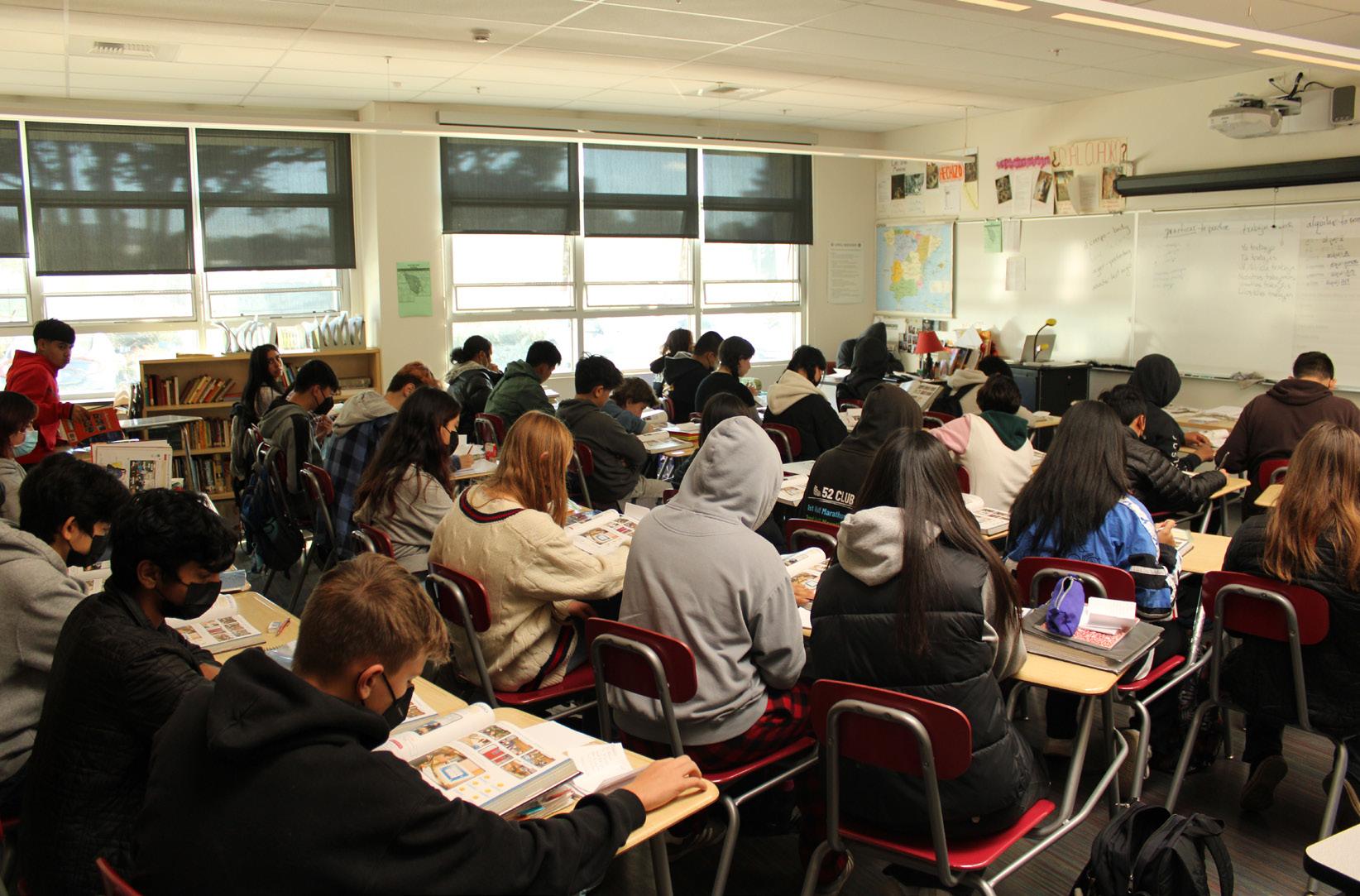

Sitting in his Spanish 1 class, sophomore Yamin Shaikh looks down at his paper filled with unfamil iar vocabulary terms. He wants to ask for help from his Spanish teacher, Carole Cadoppi, but is hesitant when he sees many of his 38 classmates also needing support. He looks next to him and notices that a student with a learning disability also needs assistance on their work.

the Lowell Alumni Association (LAA) and the Parent Teacher Student Association (PTSA) donated $900,000 to alleviate some of the impacts. However, Lowell is still suffering effects, including overcrowded classrooms and understaffing. In the World Language and Visual Per forming Arts departments, teachers are struggling to at tend to students’ needs, as they feel overwhelmed with

Shaikh realizes this is not a problem unique to him alone, but one many of his classmates are also experiencing. Lacking the help he needs during class, he doesn’t feel motivated to succeed in Spanish. To Shaikh, there are too many students and only one teacher.

As a result of understaffing, experiences like this are common among Lowell students.

Following the budget cuts San Francisco Unified School District (SFUSD) imposed last school year, Lowell is experiencing a 25 percent budget cut and widespread understaffing. After the removal of AP funding, Lowell was predicted to lose 29 teachers and staff, leaving classes cut and consolidated. Because of these predicted losses,

the increased class sizes. Understaffing in the Learning Resources Department and the Library is resulting in stu dents’ needs going unmet.

Lowell’s World Language Department was heav ily affected by budget cuts. According to Department Chair John Raya, seven Spanish classes were consolidat ed, with 12 out of the 40 Spanish classes having over 35 students. For Cadoppi, she struggles to fit 38 students into her classroom. “I don’t have enough desks for one of my classes,” Cadoppi said. “Somebody has to wait and see who’s absent before they can even sit down.” According to Cadoppi, the increased class size has caused grading to take much longer, and prevented her from teaching

“Somebody has to wait and see who’s absent before they can even sit down.”PHOTOS BY MALENA CARDONA

Spanish cultural activities such as cooking and dancing. She also feels that she can’t provide appropriate attention to students and can’t teach the course like she did before. According to her, having 25 students would be much preferable. For junior Scarlett Carew, a Spanish 3 student, her large class size has minimized the individual attention each student receives from her teacher, and reduced the number of opportuni ties to speak out loud in class. “I learn things best by speaking and experienc ing them,” Carew said. “And you don’t get to do that as much in a big Spanish class.”

World Language teachers have taken multiple initiatives to communi cate the urgency of this problem to the Lowell adminis tration, but changes have yet to be made. According to Cadoppi, she and other World Language teachers filed several grievances to hire more teachers. To further her efforts, Cadoppi personally wrote to Lowell’s principal about how it directly affected her and other Spanish teach ers both mentally and physically. “I know my colleagues,” Cadoppi said. “One of them has chronic migraines now, and another one has insomnia.” Despite these efforts, she has not gotten a response back. Cadoppi was disappointed at the lack of acknowledgement of the understaffing with in the World Language Department. “We have not been sent any emails. It has not been discussed,” Cadoppi said. “When we try to bring it up, it’s just dismissed.”

the teacher without her having to rush around and talk to ten different kids who are all like, ‘Hey, I need help with this’” Perez said. “She just doesn’t have the ability to go around and talk to everybody.”

In addition to art classes under going changes, choir and band classes have also been consolidated. There is now only one band class and one ad vanced choir class. For the band class, VPA Department Chair Jason Chan said this has been especially detrimen tal due to the vast differences in skill level and style of the students. “Jazz, symphonic, and advanced bands are all in one,” Chan said. “They’re at different levels, especially jazz, [since] they play different music. Instead of being able to rehearse in class, jazz band needs to do it after school.”

Additionally, the VPA department was forced to cut both Architecture and Photography classes, taking away opportunities for students who might be interested in pursuing these fields. Architecture is only offered at a handful of SFUSD high schools, with Lowell no longer being one. After taking Architecture 1 as a sophomore, junior Madison Chou discovered an interest in pursuing the subject in higher education. With the removal of the class, she feels that she can no longer properly explore her interest in architecture. “I thought, ‘Oh this is kinda fun, I think I might want to do this in college,’” Chou said. “I was going to try it out a little bit more in depth, but that didn’t happen.”

Scarlett Carew

Budget cuts have also negatively impacted the Visual Performing Arts (VPA) De partment. It was forced to combine classes, such as Art 3 and AP Art, resulting in classrooms of around 40 students. Senior Catherine Pe rez said that this has been especially damaging because art classes re quire a certain amount of space to do projects. “At the beginning of the year, people had to share desk spac es,” Perez said. “So it’d be two or three kids per desk. People felt very squished, like they wouldn’t have the space that they usually need.”

AP Art, in particular, requires the construction of a large portfolio due in December, leading to high de mand for individual meetings with the teacher. According to Perez, her art class has too many students for this to be possible. “It’s difficult for kids to get one-on-one time with

Overcrowded class rooms and understaffing is also affecting the Learning Resourc es Department. Currently, it is down 12 paraeducators out of a total of 39. According to Learning Resources Department Chair LaMastra Vida, paraed ucators are important because they provide one-to-one sup port to students with behavioral and medical concerns. “[These students] are our first priority,” Vida said. “Those positions have to be filled.” According to Vida, in previous years, there were enough paraeducators within the department to substitute for teachers when they were absent. Now, teachers within the de partment use their lunch time to cover for other classrooms. Ad

BY DYLAN TWYMANTo Shaikh, there are too many students and only one teacher.

ditionally, Chan noted that, in VPA classes, there are an insufficient number of paraeducators for these students to receive effective assistance. “We want to support them, but there’s just one of us and there are five special-ed stu dents,” Chan said. “I feel the stress of, ‘Oh I want to help’, but I need to keep the class going, too.”

Budget cuts have also hit Lowell’s library staff. It has been cut in half, from two full-time librarians to one. This has come despite the library receiving funds from the LAA and PTSA’s $900,000 check to alleviate budget cuts. The LAA and PTSA specifically requested that the library be earmarked to receive funds to hire a second librarian. When longtime Lowell librarian Steven Sasso retired at the end of the 2021-2022 school year, Matt McDonnell was hired for the position. However, after McDonnell’s

and requires more than one librarian to assist students. “I’ve only been to a couple other school’s libraries, but there was only a fraction of as many students using the facilities. And even then, not for doing homework, just re laxing between classes,” Jones said. “Whereas [at Lowell,] we teach here.”

Jones voiced his frustration with the adminis tration’s decision to close the librarian position, as one fewer librarian resulted in library closures before school and during Blocks 1 and 5. “I’m shocked at the lack of concern about what the consequences are of closing the library,” Jones said. Senior Tracy Law said she was forced to study in the hallways, because the library was closed. Due to the importance of the library as a resource, other staff members have had to temporarily fill in to maintain

transition to assistant principal in November, there is no longer a second librarian nor an option to have one. Ac cording to the Lowell librarian Jonathan Jones, Lowell’s administration does not plan on hiring another librarian and has indefinitely closed the position, meaning the li brary cannot hire a substitute to help out as they had done in the past. Although most other SFUSD high schools only have one librarian, Lowell had a tradition of having two. Jones believes Lowell needs two certificated librari ans, because it’s one of the most popular spots on campus

the library’s usual hours of operation. McDonnell moni tors the library from 8 to 8:40 a.m., while Math teacher Alex Cheng takes over during first block. However, this is not a permanent solution. Due to McDonnell’s position as assistant principal, he often needs to attend to administra tive duties before school, leaving no option but to close the library. Similarly, Cheng may not be able to continue to supervise the library next semester, as he is currently giv ing up his teacher prep period during first block to do so. Although the library can be open with approved adult su pervision, Jones believes that the presence of a certificated librarian is essential to best serve students. In addition, when Jones teaches classes on information and literacy, the rest of the library must be closed if there is no other official supervision. Without the option to hire another librarian, Jones is not opti mistic about the situation. “As far as I’m concerned, this is the first of many cuts that will happen,” he said.

Lowell’s financial future is unclear. The only thing that is certain is that the methods the school took to keep it self afloat are unsustainable moving forward. Accord

The only thing that is certain is that the methods the school took to keep itself afloat are unsustainable moving forward.Carole Cadoppi

ing to Social Studies Department Chair Rebecca Johnson, depending on outside sources of funding, including the Alumni Association and the PTSA, cannot be a longterm strategy. “The district put out this mandate last year that everyone had to take a nine percent cut. But we were facing a 25 percent cut, and that’s just unsustainable and catastrophic for us,” Johnson said. “Again, we patched the holes for a year, hoping that the district would come to realize just what 25 percent out of this school means, but I don’t know that they’re aware or that they care.”

On the other hand, increased state funding does provide some hope for the future. The statewide budget has been steadily rising over the years and has been at a record high in the years following the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition, the recently passed Prop osition 98 sets a guaran teed minimum budget for California public schools and could result in $37.2 billion being al located to schools. But these increases come

with a big catch. According to Julien Lafortune, a research fellow at the Public Policy Institute of California, these recent budgets often include one-time funds that will not be included in coming years. “[Budgets] could even look worse in a few years depending on how they’ve factored these one-time funds into the deficit,” Lafortune said. In

terms of usage, these are lump sums that the district “can’t use to hire someone that will stay in the district for many years in a row, because that goes away in a couple years,” Lafortune said. So, in the end, the hope among teachers that Prop. 98 will alleviate the impacts of budget cuts, in cluding overcrowded classes and understaffing, may be dashed.

As one teacher with too many students, Cadoppi stands in her Spanish 1 class with a feeling that she can not support all of them, including students like Shaikh. “They’re lost. They feel annoyed,” she said. “They feel in visible.”

“I’m shocked at the lack of concern about what the consequences are of closing the library.”

The mullet has made a comeback. Are you enraged? Horri ed with the haircut that de ned ’80s glam rock? Or are you ecstatic, ready to take scissors in your hand and give yourself a DIY chop? Despite the polarizing opin ions regarding mullets, the look is here to stay.

e hairstyle is characterized by two main elements. ere’s the “busi ness” aspect: a sleek, normal-appearing front; and the “party” aspect: a dramat ic, lengthy back. e contrast has blazed the mullet’s legacy of controversy, caus ing many people to view it with distaste. However, the unsightly look is what makes mullets attractive; the objectively ugly haircut is alluring, simultaneously destroying beauty constructs while al lowing the wearer to value frivolity over pure looks.

One valuable element of the mullet hairstyle is its androgyny. e

masculine, scru y front combined with an elegant rear makes for a gender-in clusive fashion statement. If you want to up your manliness, give yourself a red neck hick mullet, consisting of a close side shave and powerful locks towards the back. If you’re looking for a more feminine look, cut yourself the chic NYC model mullet, a pixie-like, layered shag.

Senior Adam Gooch has been rocking a mullet a er a spontaneous, at-home haircut during the beginning of their junior year. Since then, they’ve dedicated themselves to the mullet lifestyle, noting it as a positive change. ey describe mullets as something transcendent and unde nable. “You see someone with a mullet and you just feel things you can’t describe,” Gooch said. ey compared wearing the cut to lis tening to your favorite song, a feeling of euphoria and elation.

e community of mullet wearers is one of acceptance and love. O en associated with David Bowie’s Ziggy Stardust and other rock stars of the ’80s and ’90s, mullets have long been worn by those in alternative cul tures. Not much has changed since. “Al ternative people do own the mullet, no matter what kind of culture you’re a part of, because mullets are inclusive. We don’t judge people,” Gooch noted. ey expressed trusting mullet wearers, feel ing a sense of personhood in a shared hairstyle.

e mullet represents much more than hair, a factor that will prevent it from ever dying out. Although one might loathe anything related to mul lets, I invite you to open up. Embrace the ridiculous, and have fun with your hair.

When my friend saw the video of me reacting to Midnights — with a scream or two, a few jumps, ailing arms, and perhaps an unusual amount of tears — he thought it was a college acceptance video, and I had just gotten into my dream school. Now that I think about it, I don’t blame him. Listening to the album for the rst time threw me into a loop of both excitement and awe.

Midnights, Taylor Swi ’s tenth studio album, shattered several records within the rst week of its release. e songs on this pop album were written about her sleepless nights, encapsulating both her night mares and sweet dreams. It’s lled with songs surrounding how others perceive her, analyses of past relationships, and raw love. Taylor Swi ’s songwriting on Midnights reveals deeper meaning through powerful, feministic, and vulnerable lyrics.

e strongest aspect of Taylor Swi ’s songs is her elegant and sophisticated songwriting, and her lyrical genius delivered yet again in Midnights. In “Labyrinth,” angelic echoes mix with parallel syntax to paint a picture of the trust needed to fall in love again a er being in a taxing relationship. She writes, “Break up, break free, break through, break down. You would break your back to make me break a smile.” is illustrates the sacri ce some people would go through to bring back their happiness.

Midnights displays Swi ’s most mature feminist writing by straying away from cliched mantras and diving into feminism in the con text of relationships. Upbeat anthems like “Bejeweled” and “Midnight Rain” portray Swi leaving a relationship due to a lack of deserved recognition and a desire for inde pendence. “Mastermind” is about cra ing a cryptic plan for a perfect relationship, despite being consistently underestimated as a woman. “You see all the wisest women had to do it this way, ‘cause we were born to be the pawn in every lover’s game,” Swi writes. Society views her as a pawn — some one weak and without control — when in reality, she holds discrete dominance which is demonstrated in the following lyric: “I’m the wind in our free- owing sails and the liquor in our cocktails.”

In an interview with talk show host Jimmy Fallon, Swi called Midnights her “ rst directly autobiographical album in a while.” As a result, it was a bittersweet release because she wanted to share her vulnera bility through the record, but also felt very fragile with millions of people listening. However, Swi ’s honesty triggers a whirlwind of emotions that allow fans to better connect to the album.

In “You’re On Your Own, Kid,” she opens up about her eating disor der and how she perceives herself. She writes, “I gave my blood, sweat, and tears for this. I hosted parties and starved my body like I’d be saved by a perfect kiss.” In “Would’ve, Could’ve, Should’ve,” Swi re ects on a toxic relationship, confessing all her regrets. e track’s bridge and outro build the instruments as the desperation in her voice seems to grow into a cry for help. She sings, “And now that I’m grown, I’m scared of ghosts. Memories feel like weapons,” and, “I ght with you in my sleep. e wound won’t close.” e pain and vulnerability revealed in these lyr ics le me stunned and empathetic, as it opened the door for listeners to understand how she was wrongfully judged for this toxic relationship.

Swi writes about her personal expe riences — including relationships, body image, and others’ external perceptions — which allows her audience to form individual connections through relatable songs. Midnights is a record with some of her best songwriting to date, and its addicting tracks are a result of lyrics only a mastermind could write.

THE STRONGEST ASPECT OF TAYLOR SWIFT’S SONGS IS HER ELEGANT AND SOPHISTICATED SONGWRITING, AND HER LYRICAL GENIUS DELIVERED

YET AGAIN IN MIDNIGHTS.

BY JOEY HE

BY JOEY HE

BY KATEY LAU

BY HUGH McDONALD

BY CHARON KONG

BY KATEY LAU

BY HUGH McDONALD

BY CHARON KONG