OBTAINABLE AND ADDICTIVE February2023

FULLY COMMITTED

BY NIYATI MANDHANI

“WAKE UP CALL”

BY MARSHALL MUSCAT

BY MARSHALL MUSCAT

After continuous lack of response from SFUSD surrounding payroll issues, Lowell teachers staged a “sick-out” to bring further attention and urgency to the problems.

2022 WINTER SHOWCASE

BY LAUREN KIM, KAHLO FRIEL-ASAY, AND YESHI-WANGMU SHERPA

BY LAUREN KIM, KAHLO FRIEL-ASAY, AND YESHI-WANGMU SHERPA

ONLINE EXCLUSIVES @THELOWELL

IT’S TIME TO END THE USE OF A HATE FILLED SLUR BY MAYA LAW

Editors-in-Chief

Chloe Chon • Kelcie Lee • Marlena Rohde

News Editors

Angela Chen • Kelcie Lee

Opinions Editor

Chloe Chon

Columns Editors

Aaliyah Español-Rivas • Dylan Twyman

Sports Editor

Roman Fong

Multimedia Editors

Libby Bowie • Marlena Rohde • Yeshi-Wangmu Sherpa

Art Managers

Darixia Varela Medrano • Elise Muchowski

Reporters

Charlotte Ackerman • Maren Brooks •

Isadore Diamond • Clarabelle Fields •

Thomas Harrison • Tatum Himelstein •

Ramona Jacobson • Alisa Kozmin • Maya Law • Stephanie Li • Anita Luo • Kai Lyddan

• Niyati Mandhani • Alina Mei • Hayden Miller • Indigo Morgenstern • Marshall

Muscat • Victoria Pan • Evan Powers • Laura

Reyes • Mehreen Shaikh • Sierra Sun • Sia Terplan

Photographers

Kahlo Friel Asay • Malena Cardona • Kylie Chau • Katharine Kasperski • Lauren Kim • Reina Lee • Ava Rosoff

Illustrators

Joey He • Charon Kong • Katey Lau • Hugh McDonald • Danica Yee • Emily Yee

Business Managers

Yi Luo • Adrienne Nguyen • Primo Pelczynski

Web Managers

Roan Rafter • Joanne Zeng Social Media Managers

Juliane Dabi • Erin Guo • Gianna Ou • Aaliyah Español-Rivas • Miyabi Yoshida

Researcher Saw Nwe Advisor Eric Gustafson

02 04 10 12 14 19 20 EDITORIAL ACCOLADES NSPA Pacemaker Top 100; 2018 NSPA Print Pacemaker Finalist, 2011 & 2014 NSPA Online Pacemaker, 2012 NSPA Print Pacemaker, 2007 & 2011 NSPA All-American, 2009 NSPA First Class Honors, 2007 NSPA Web Pacemaker, 2007 CSPA Gold Crown MULTIMEDIA MEDIA REVIEWS NEWS FEATURE HOT TAKE COLUMN UNDERREPRESENTED STUDENTS NEED ADMINISTRATIVE SUPPORT MY SILENT PROTEST BRIDGING THE GAP FOR ENGLISH LEARNERS OBTAINABLE AND ADDICTIVE DEFINING DECADES: A TRIBUTE TO NADIA LEE COHEN OVERPRICED AND OVERWROUGHT HIGH SCHOOL MUSICAL 3: SENIOR YEAR SOMETIMES I MIGHT BE INTROVERT

COVER The Lowell February 2023 1

SPREAD

DESIGN BY MARLENA ROHDE

UNDERREPRESENTED STUDENTS NEED ADMINISTRATIVE SUPPORT

When freshmen students are thrown into the crowded hallways at Lowell, some feel lost among the 75 percent Asian and White students. The disproportionately low representation of students with Black and Latinx backgrounds render them unable to easily find a sense of community at school. To address this, the support programs African American Common-Core Education Support Group (AACES) and Latino Equity Achievement Program (LEAP) were created through the leadership of former principal Andrew Ishibashi to provide in-depth mentorship and academic aid. Today, nearly a decade later, administrative support for these programs has diminished to the point where they are at the cusp of extinction. For the sake of these struggling Black and Brown students, Lowell’s administration needs to center more attention on AACES and LEAP.

For students that are involved in LEAP and AACES, they’ve been successful in finding comfort through a small community that celebrates a similar heritage. These affinity groups help create meaningful connections between students, bolster their academic performance, and build familiarity with the student body. Through LEAP, Latinx underclassmen are welcomed by other Latinx student mentors and are encouraged to socialize with their peers, under the supervision of program coordinator Christian Ferrey. Similarly, AACES allows Lowell’s Black community to take advantage of scholarship opportunities and receive school support from program coordinator Timothy Gray. As students build friendships and a better appreciation for their culture, these programs help bridge the gap of unfamiliarity in the Lowell community.

When principal Ishibashi was in charge, he made it a priority to aid Lowell’s disadvantaged communities through these programs. Ishibashi was able to do so through the frequent meetings he held with each program’s coordinators and the sufficient funding he designated to LEAP and AACES. “In the past when Ishibashi did it, he would meet with [coordinators] regularly to set up goals and ideas, and give guidance,” college counselor Maria Aguirre said. “These programs were like Ishibashi’s babies — he was the one that envisioned them, so he put people in place and gave them guidance as far as what to do for students.” Following his departure from Lowell in 2019, the administrative support that LEAP and AACES once had, decreased.

The constant restructuring of administration, including three new principals in the past four years, has meant that these programs have not been sustained thoroughly or consistently since 2019. Since the departure of Ishibashi, the incentives and instructions to preserve LEAP or AACES have

not been passed along the line of principals. Currently, these support programs no longer have regular meetings with administration, clear funding, or coordinators with enough bandwidths to lead them. Ferrey said that the administration’s recent hecticness and his workload led to his initial uncertainty of LEAP’s existence this school year. “It hasn’t been a priority for not just the administration, but us too,” he said. “And to be honest, I didn’t even know if I was going to receive any funding this year for LEAP,” Ferrey said. Without the support, the programs were unable to host their yearly cultural events or even split the duties to other possible adult sponsors at Lowell.

Additionally, distance learning during the COVID-19 pandemic put a pause on the AACES program in the 2020-2021 school year, making it difficult for many Black students to receive academic or emotional support through them. “[The pandemic] definitely put a block to the progress we were making with AACES, and everything kind of got off target,” Gray said. He feels that the pandemic took away a crucial year for many Lowell students, as a year of inactivity has meant that most students are now not even aware of the programs. The affinity groups resumed last fall, but they continue to receive little attention from the administration. As a result, AACES and LEAP remain invisible to struggling students.

With the administration turning its back on LEAP and AACES, many upperclassmen have taken matters into their own hands. Despite their busy schedules, they’ve committed themselves to helping underclassmen within the programs themselves. At times, upperclassmen in LEAP prepare future meetings regarding how to help their mentees academically, without the attendance of their adult sponsor. Since carrying the weight of aiding underclassmen in a minimally supervised space, the upperclassmen feel overwhelmed. In the case of LEAP, members are no longer meeting at all. Black and Latinx students remain sunken in an ominous ocean of disproportionate demographics and lack of support. Many are exhausted from holding onto LEAP and AACES for dear life. These affinity groups have allowed students to reconnect with their community and opportunities to excel academically with the aid of their coordinator. It is imperative that the Lowell administration aids these diminishing programs through more funding and giving guidance by holding meetings with students and advisors. The power to build a future of inclusivity and community at Lowell rests in the hands of administrators, and to achieve that, they must understand the first step: recommitting themselves to the LEAP and AACES programs.

2 The Lowell February 2023 EDITORIAL

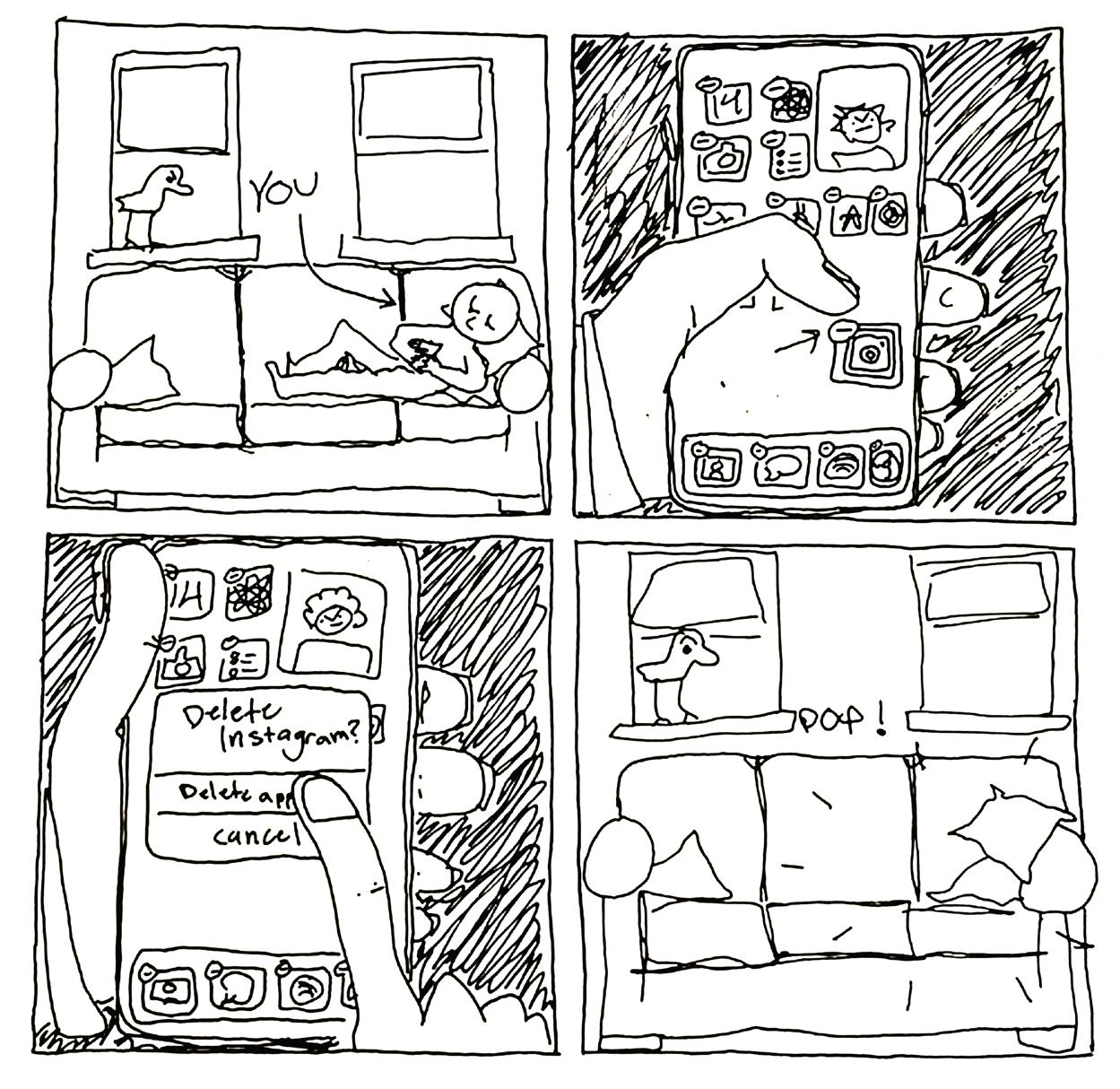

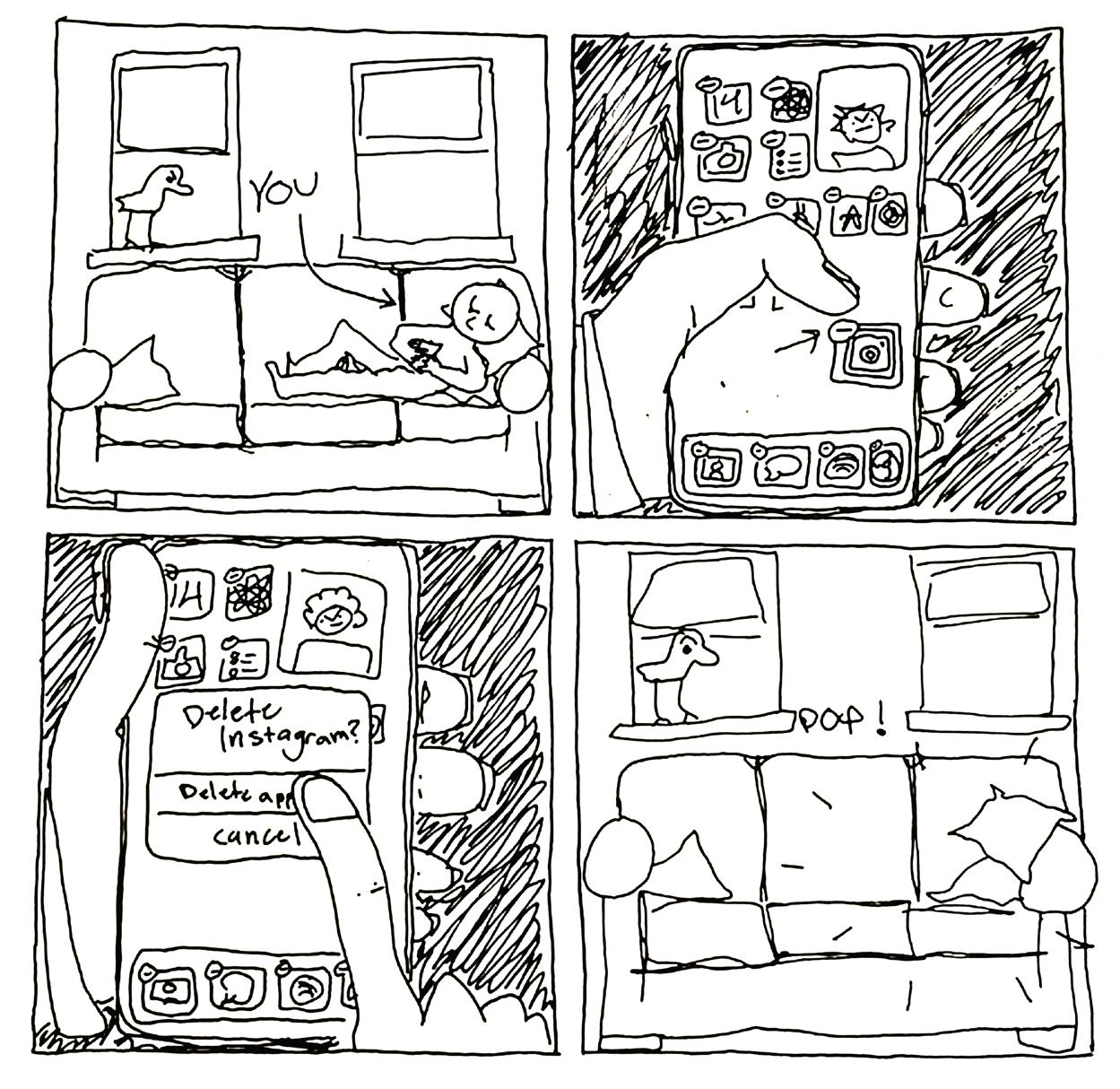

LITERALLY YOU

BY HUGH MACDONALD

From the editor

Dear readers of The Lowell, With the start of the new year, people often think about new beginnings. We at The Lowell began our spring semester with around 20 new members, resulting in one of the biggest staffs we’ve ever had. And with the start of this new semester, we decided to finally pursue an article that has been in the works for years: an in-depth look at drug use at Lowell. Underage illicit drug use has been an issue for a long time, but as each successive false fire alarm attests to, it’s a growing problem at Lowell. In our cover story, “Obtainable and addictive,” we’ve tackled it by interviewing users, admin, and experts, as well as conducting a lengthy survey of 32 randomly selected registries. What we discovered was a need for more resources. In this issue, we also focus on several other groups who need more support from our community, including Lowell’s growing English Learner population and Black and Latinx students who face disproportionately low representation on campus. While some of these issues are attributed to district or school policies, there are also ways that parents, students, and other community members can help these groups. We hope these articles help open up conversations on how we can better support Lowell students.

Editors-in-Chief, Chloe Chon, Kelcie Lee, and Marlena Rohde

The Lowell is published by the journalism classes of Lowell High School. All contents copyright Lowell High School journalism classes. All rights reserved. The Lowell strives to inform the public and to use its opinion sections as open forums for debate. All unsigned editorials are opinions of the staff. The Lowell welcomes comments on school-related issues from students, faculty and community members. Send letters to the editors to thelowellnews@gmail.com. Names will be withheld upon request. We reserve the right to edit letters before publication.

The Lowell is a student-run publication distributed to thousands of readers including students, parents, teachers, and alumni. All advertisement profits fund our newsmagazine issues. To advertise online or in print, email thelowellmanagement@gmail.com. Contact us: Lowell High School 1101 Eucalyptus Drive San Francisco, CA 94132, 415-759-2730, or at thelowellnews@gmail.com.

SPREAD DESIGN BY KELCIE LEE

The Lowell February 2023 3

CARtoon

ILLUSTRATION

As illicit drug use increases on Lowell’s campus, some students find themselves reliant on substances and unable to receive help from school.

4 The Lowell February 2023

PHOTO-ILLUSTRATION BY KATHARINE KASPERSKI AND DANICA YEE

The Lowell February 2023 5

SPREAD DESIGN BY MARLENA ROHDE

Veronica, a sophomore under a pseudonym, stood inside the handicap bathroom stall, waiting nervously. It was her first time buying drugs on campus. As she stood waiting, her eyes drilled into the door when she suddenly heard footsteps approaching. Soon enough, the door swung open and her friend walked in. She saw the plastic bag containing a vape and cigarettes and quickly took it from her, tucking it away and out of sight. Veronica pressed crumpled up bills into her hand, before leaving the bathroom within a couple seconds. That was easy, she thought.

Veronica is not alone in her experience.

Illicit drug use by students has been a continuous issue at high schools across the country, including Lowell. However, interviews with a number of students and a poll conducted by The Lowell suggests drugs are relatively easy to obtain on campus and that a number of students are using them. In some cases, this includes the use of hard drugs. This has led to increasingly detrimen-

2023

tal effects on both Lowell students who abuse drugs, and students who don’t as well. Although Lowell has policies in place aiming to combat the issue, students believe that these efforts aren’t enough to support those who use illicit drugs.

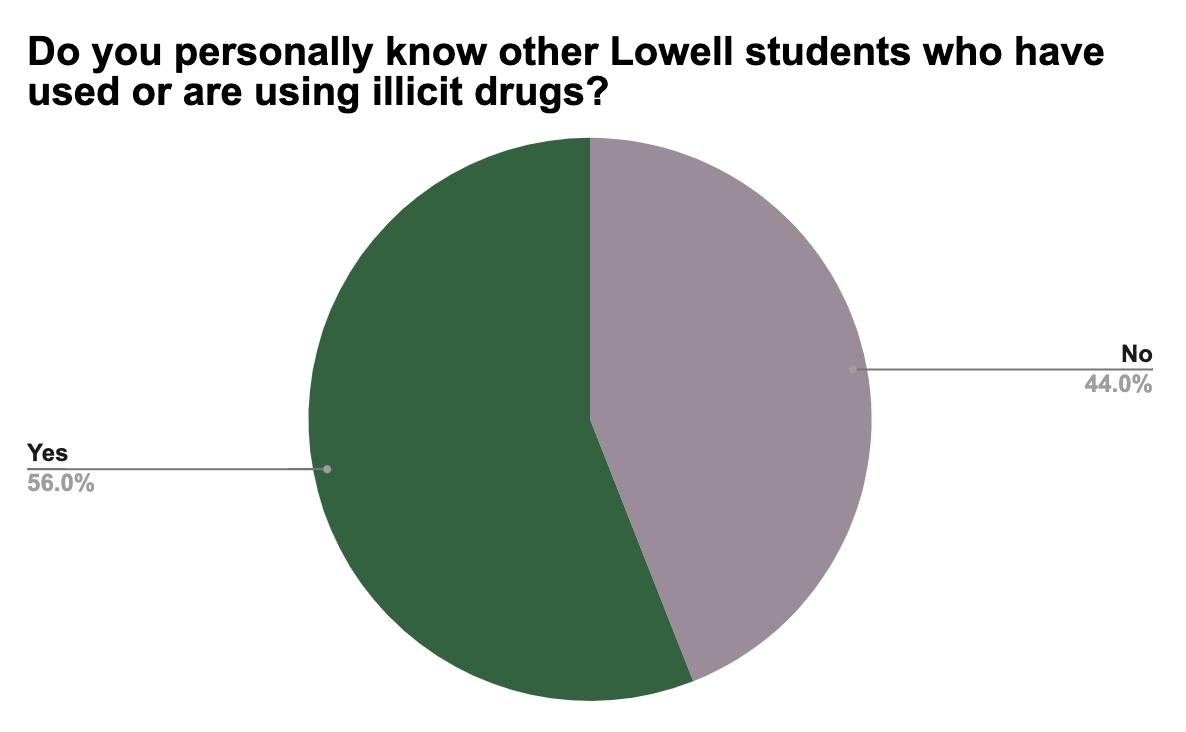

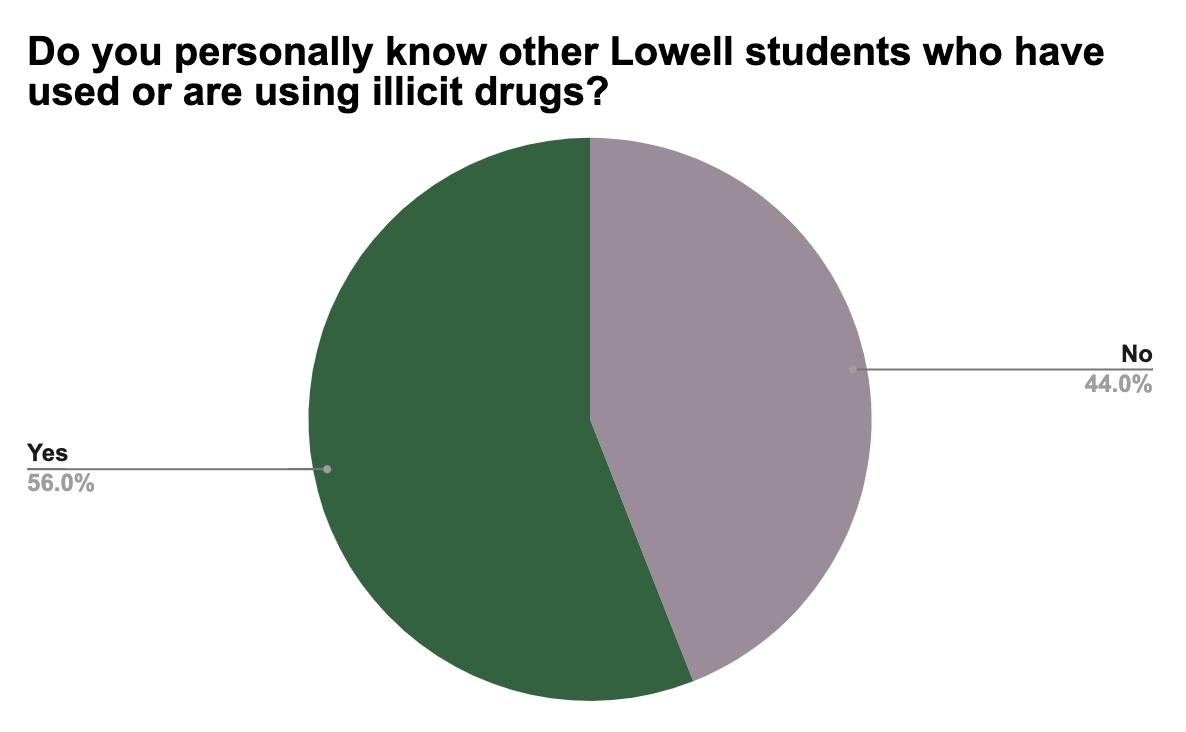

Many students are aware of the prevalence of drug use on campus. In a January 2023 survey conducted by The

Lowell of 20 randomly selected registries, 44 percent of respondents reported directly witnessing Lowell students using illegal drugs on campus, and 56 percent of respondents said that they knew at least one Lowell student who has used or is using illicit drugs. These statistics are backed by the Lowell administration, including Isaac Alcantar, one of Lowell’s assistant principals, who believes that vaping and other forms of smoking is an expected issue among high school students.

For many, the student bathrooms are the primary hotspot for smoking and drug use, with smoking in particular being the most prevalent. With the rise of e-cigarettes and vapes, many students use these bathrooms for smoking throughout the day. Emily, a junior under a pseudonym, likes to leave class to vape in different bathrooms across the campus. Before Emily leaves for the bathrooms, she texts

The Lowell February 2023

6 COVER

“I have to go around school, trying to find an open bathroom that doesn’t smell like drugs.”

Data from a random sample of 268 students who responded to a survey conducted by The Lowell in January

some of her friends. They discuss what flavor vapes everyone has, if anyone has marijuana, and if anyone is available to come share their goods with her. “I will text a couple friends and ask them to meet in the bathroom, and then we all bring our stuff, and then kind of just vape,” she said. If nobody is willing to come meet Emily, she’ll just smoke by herself.

Because illicit drug use by high schoolers typically includes nicotine and marijuana, the abuse of more dangerous drugs on campus has gone largely unnoticed. Veronica was alarmed after hearing about Lowell students abusing what she called “harder” drugs, including hallucinogens like ketamine. “You don’t imagine high schoolers using [these drugs],” she said.

Adderall is one example of a drug only prescribed for medical purposes that some Lowell students are using illegally. Anna, a senior at Lowell under a pseudonym, sells extra pills that she receives through her medical prescription for her ADHD. “People generally take it if they want to really focus or really study,” she said. “Finals week, SAT tests, AP tests, things like that; it’s performance-enhancing drugs for academics.” This proved apparent for Ryan, a senior at Lowell under a pseudonym, who tried Adderall during his junior year after hearing from friends that it helped students focus. “I tried ‘study drugs’ because a lot of my friends were,”

he said.

While Lowell’s administration is aware of a certain level of substance abuse on campus, there hasn’t been any awareness of more harmful substances that surveyed students have reported using, including ketamine, Adderall, and cocaine. “[Harder drugs] haven’t come onto our radar,” Alcantar said. “I think right now the biggest challenge

we have is the vaping type of materials.” According to Dr. Steven Sussman, the Professor of Population and Public Health Sciences at the University of Southern California (USC), easy access to drugs leads to addiction and dependence among teens. “A social climate that does not impede use can result in use continuing until a problem develops,” Sussman said. Lowell students who have attempted to obtain drugs on campus have found that the process can be surprisingly easy, which can fuel further drug abuse. “The access [to drugs] is definitely there. It’s easy to fall into it,” Veronica said. “I think once you know one person, you get introduced to others and realize how many kids at Lowell actually do drugs.”

Jamie, a senior under a pseudonym, believes that obtaining illicit drugs depends on who you know. “If you know the right people, and you have the right friends, then it can be really easy, like it was for me.” she said. When Jamie was interested in buying cocaine, she easily found a seller through mutual friends. “We made a plan, and she just gave it to me in the bathroom,” she said.

Some students believe that drug use at Lowell has greatly increased recently, which falls in line with a greater nationwide trend. With COVID-19 slowly subsiding, schools opening back up, and people interacting more, there has been a bigger opportunity for students to access drugs. According to Monitoring the Future, a national study conducted yearly, nearly all forms of illicit drugs have gone up in use among high schoolers from 2021-2022. According to Ryan, this issue has gotten blatantly worse over the past year on campus. “So many more students, including younger grades, are just vaping in bathrooms and it’s becoming more obvious,” he said. According to Alcantar,

INFOGRAPHICS BY SAW NWE, ILLUSTRATIONS BY EMILY YEE

INFOGRAPHICS BY SAW NWE, ILLUSTRATIONS BY EMILY YEE

SPREAD DESIGN BY DYLAN TWYMAN

SPREAD DESIGN BY DYLAN TWYMAN

The Lowell February 2023

7

“The access [to drugs] is definitely there. It’s easy to fall into it. I think once you know one person, you get introduced to others and realize how many kids at Lowell actually do drugs.”

Lowell has also seen “an uptick in our fire alarms triggered,” which has been attributed to vaping in the restrooms. The consequences of substance abuse can be especially detrimental to teens, who don’t have fully developed brains and often experience harmful

perienced side effects such as extreme nausea and dizziness that reminded him of the dangers of taking illicit substances. “It’s an illegal drug that I took for f*cking algebra homework,” he said. “It’s not worth it.”

side effects. Academically, the cognitive and behavioral changes caused by drug abuse can frequently lead to challenges in doing schoolwork, while more time spent using drugs can lead to students skipping classes, according to the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. Many mental health problems may also arise because of drug use. According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, drug-abusing youth are at a higher risk of having mental health problems, such as personality disorders, depression, and suicide. Drug abuse can also affect a person’s physical health, weakening the immune system and increasing the risk of many illnesses and infections, according to Gateway Foundation. After taking Adderall to help him focus on homework, Ryan ex-

Substance use on campus has started to affect the greater student population as administration attempts to mitigate the issue by shutting down restrooms. “Fire alarms have been going off in specific bathrooms,” Alcantar said. “We’re trying to make sure that students aren’t using them for things that are inappropriate, like vaping or smoking, and stuff like that, which is not the purpose of the bathroom.” As a result of these shutdowns, survey respondents reported waiting in long lines, traveling to different floors and school buildings, and not being able to use the bathroom at all. One respondent was frustrated when trying to find smoke-free bathrooms. “I have to go around school, trying to find an open bathroom that doesn’t smell like drugs,” they said. Another reported difficulties in trying to use gender-neutral bathrooms. “As someone who identifies as non-cisgender, it’s frustrating when I need to use the gender-neutral bathroom but other people are using it for drugs,” they said.

To combat the issue, Lowell’s administration has long followed San Francisco Unified School District’s (SFUSD) policies when addressing students caught using substances. According to Alcantar, SFUSD policies and

guidelines use a “progressive discipline model,” which involves a more supportive approach to drugs. “We try to start with bringing the student in to thinking about why they’re doing it, bringing the family on board, and making sure that we’re trying to support the kid to make better choices,” Alcantar said. “We refer the students to Brief Intervention Services, which is where they talk about what kind of substance abuse they’ve been doing and why.” If a student is caught using substances on campus after that, they risk being subject to harsher disciplinary measures, includ-

The Lowell February 2023

8

“We don’t have a nurse anymore, so I don’t really know who I would go to.”

Although Lowell has policies in place aiming to combat the issue, students believe that these efforts aren’t enough to support those who use illicit drugs.

ing suspensions and expulsions.

The students interviewed for this story conveyed confusion about both the penalties for drug use on campus, as well as the help they can receive to stop using. Several sources just aren’t aware of the help that they can get at school for addiction, and expect punishments from administrators. Laura, a senior under a pseudonym, who is currently struggling with a nicotine addiction, said that the consequences of reporting drug use to school staff is not accessible information. “It isn’t common knowledge,” Laura said. She also said that when her friend was caught vaping, their device was taken away and their parents were called. She believes that is punishment enough and doesn’t want to turn to school staff, in fear of their parents knowing.

Although these policies exist, many students believe that there still aren’t enough available resources at Low-

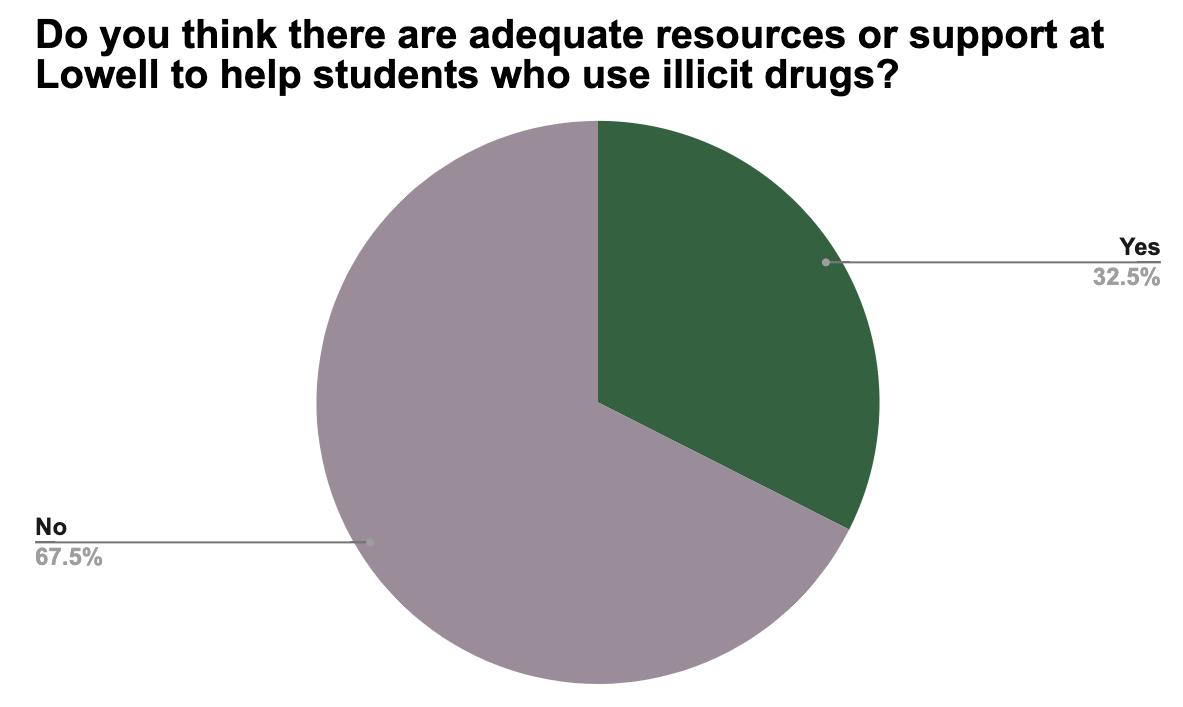

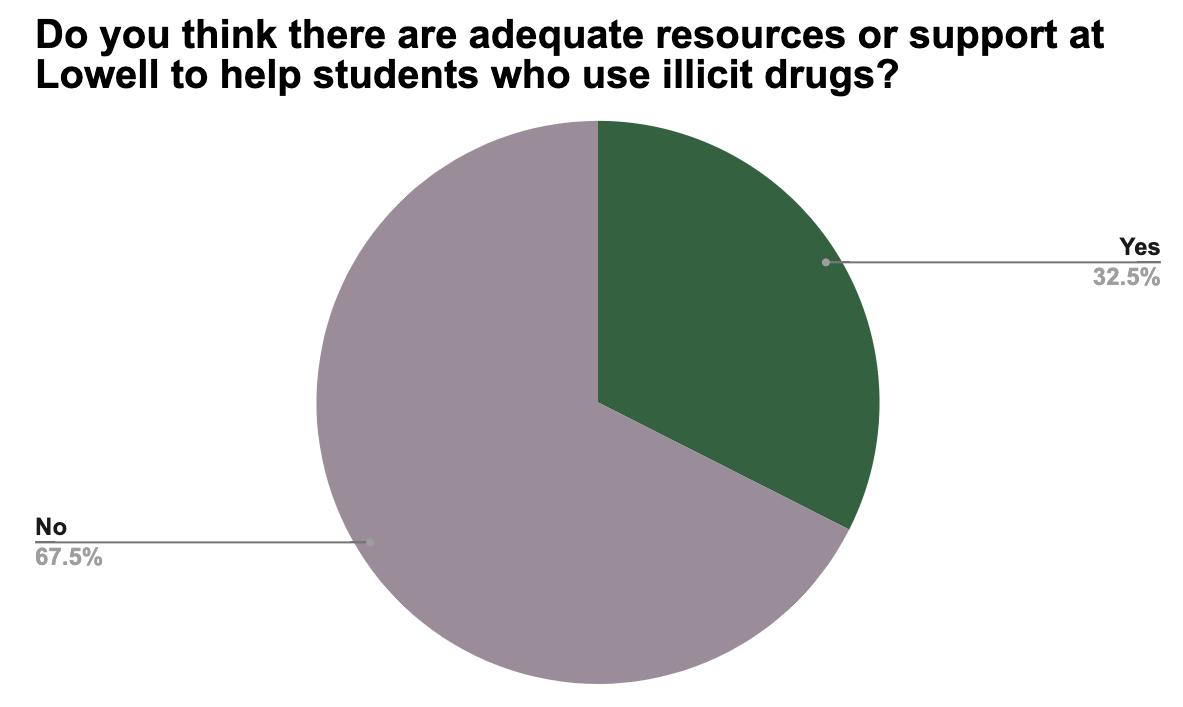

ell. According to Veronica, she felt lost when considering reaching out for help. “We don’t have a nurse anymore, so I don’t really know who I would go to,” she said. Though Veronica considered her counselor, she ultimately decided that wasn’t a comfortable option either. “[My counselor] has a ton of kids to talk to and not having that connection makes it harder to go to him for personal things.” Sixty-seven percent of survey respondents reported that they believed Lowell did not provide adequate resources or support to help students who use illicit drugs. Ryan believes that Lowell doesn’t do enough about drug use, and needs to be more vigilant in how they prevent students from “spiraling down the drug hole.” Laura believes Lowell should take steps toward providing more resources. “I think it would be very beneficial to a lot of people if they had more educational services and help for people who are struggling with addiction,” she said.

Additionally, the fear of getting in trouble or facing disciplinary action at Lowell, along with what many believe is a punishment-oriented approach to drug use, prevents many students from reaching out for support despite the need for help. Dr. Sussman believes that implementing proven programs that focus on students’ wellbeing and rehabilitation can help, especially with nicotine addiction. “There are evidence-based programs for teen cessation from tobacco use, such as Project EX,” he said. Project EX, a schoolbased program for teenagers, “aims to teach self-control, anger management, mood management, and goal-setting techniques, and it provides self-esteem enhancement.”

At present, Lowell is missing two key elements for providing such wellbeing support

for its students: a nurse and a Wellness coordinator. The two employees staffing these positions quit this past fall, and, as of yet, no new hires have been made. According to principal Mike Jones, there are currently no candidates for these positions and he does not anticipate there being any for the rest of this semester. At a recent faculty meeting, he explained that problems with SFUSD’s EMPowerSF payment system has driven away potential candidates. “Folks don’t want to work in the district at this point,” he said.

Without a nurse or a fully staffed Wellness center, much less a dedicated drug program such as a Project EX, students struggle to receive the help they need. In some cases, they don’t know who to turn to, or if they should reach out to adults on campus. “I don’t even know if you get in trouble for going to a counselor and saying you’re addicted, but we need to get rid of that idea because some people do want help,” Ryan said. “They’re just afraid of getting in trouble if they do reach out.” For Veronica, this fear has kept her from confiding in adults at Lowell as well. “Even when we had a nurse, I was scared to go to her because I thought I would get in trouble,” she said. Laura also believes Lowell’s approach to the issue deters students from seeking help. “Addiction is not a choice, it’s a disease,” she said. “I think they punish us instead of offering support, which is really problematic.”

INFOGRAPHICS BY SAW NWE, ILLUSTRATIONS BY EMILY YEE

SPREAD DESIGN BY DYLAN TWYMAN

The Lowell February 2023

9

“I don’t even know if you get in trouble for going to a counselor and saying you’re addicted, but we need to get rid of that idea because some people do want help.”

MULTIMEDIA

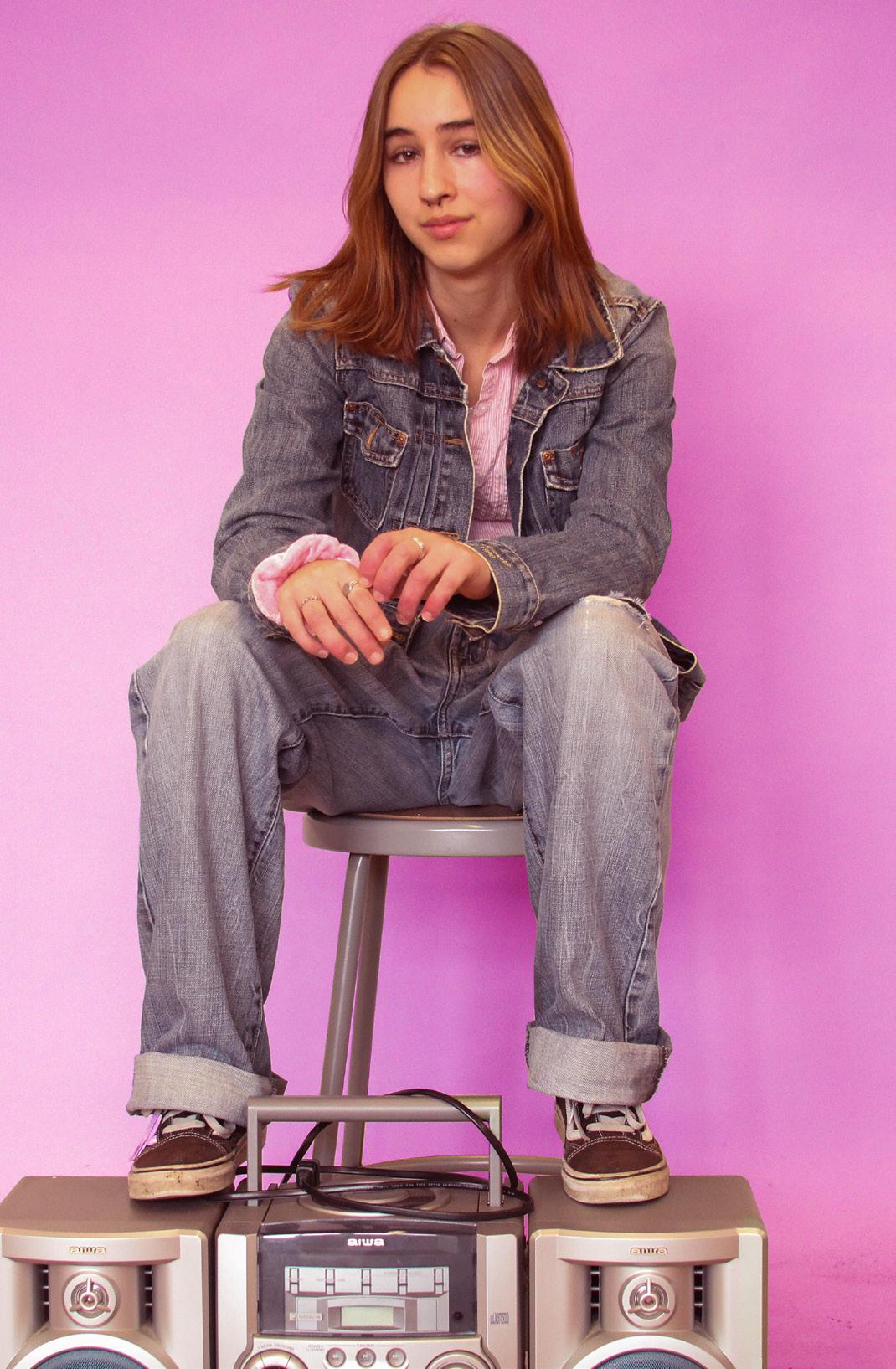

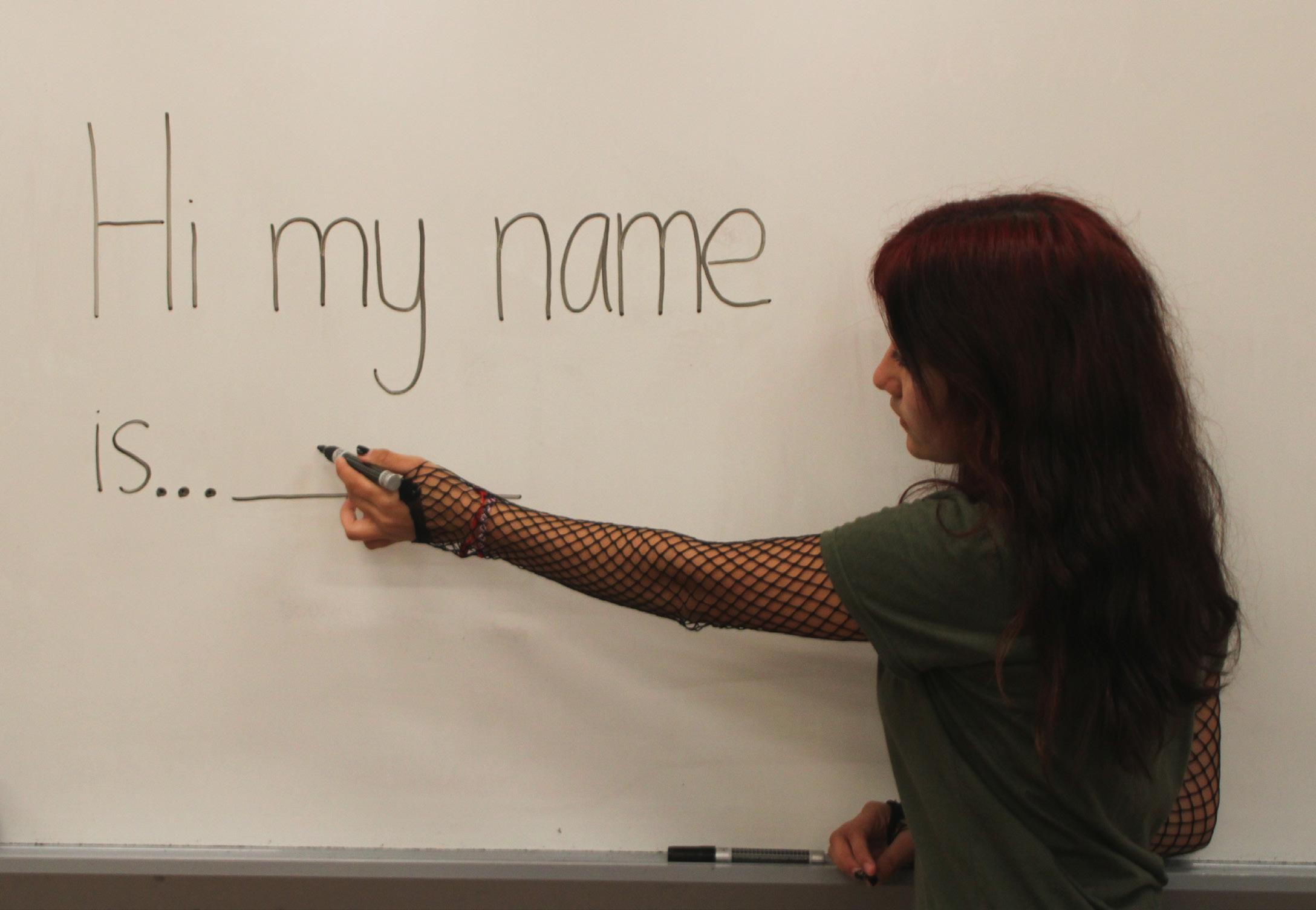

DEFINING DECADES: A

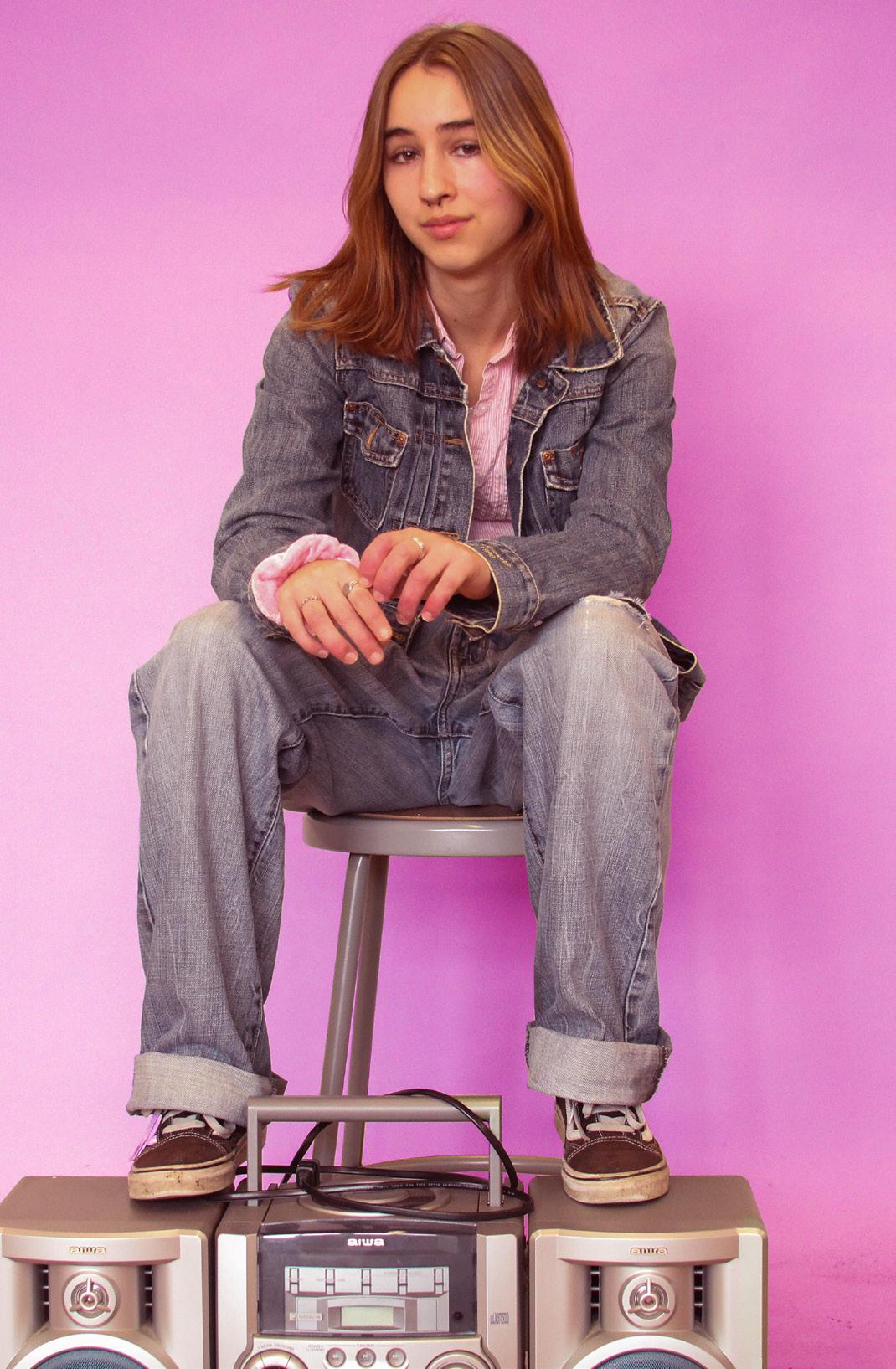

TRIBUTE TO NADIA LEE COHEN

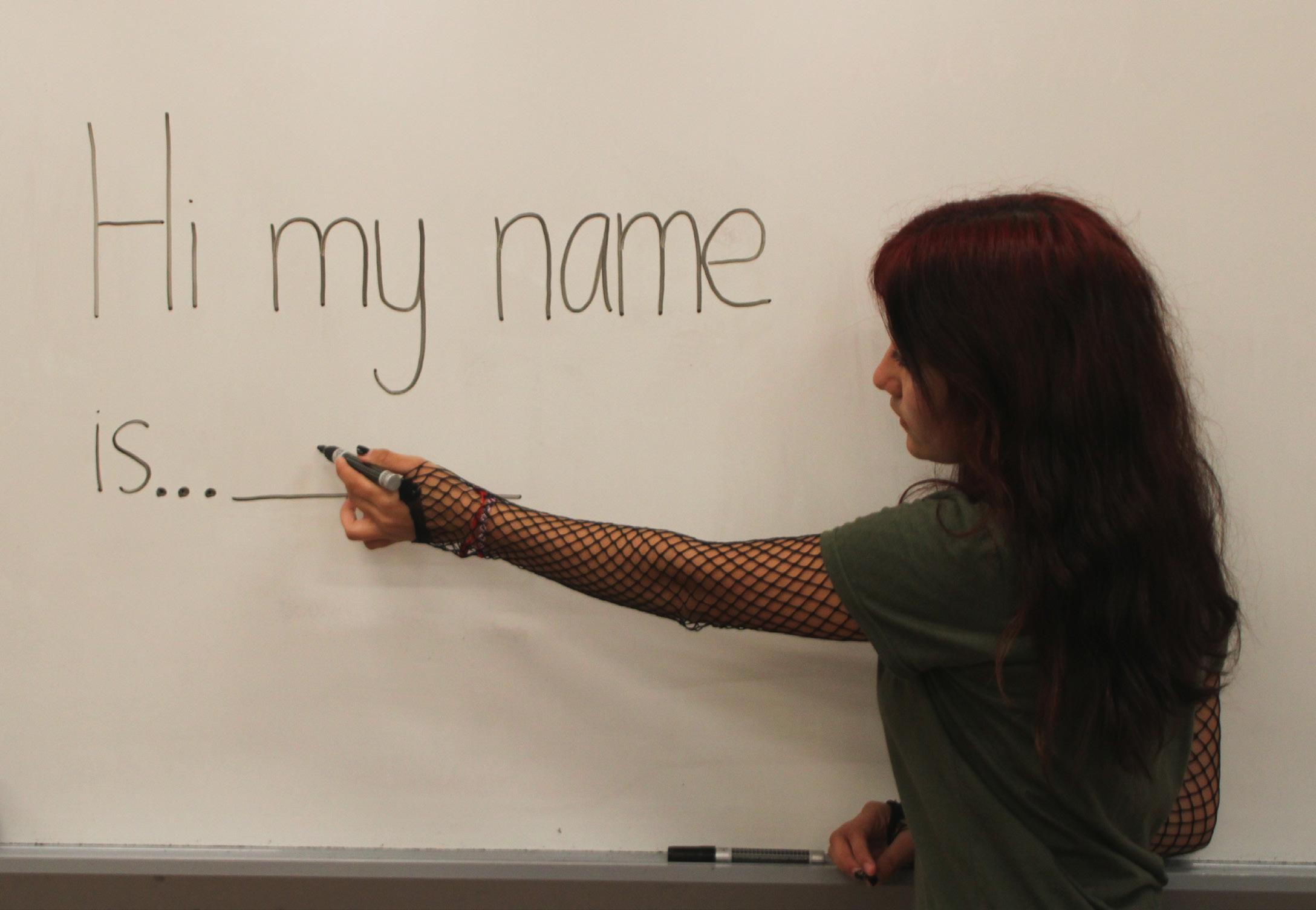

How can one encapsulate a person’s nature in two images? British photographer Nadia Lee Cohen’s multimedia project “Hello, My Name Is,” from 2022, answers this question. It portrays the artist transformed into 33 original personas. Each character’s distinct life and personality is summed up in two photos: one portrait, and one shot of their belongings. Cohen’s pairing of familiar faces with their personal items allows viewers to gain an intimate understanding of the individuals’ disposition. Our multimedia team was inspired by Cohen’s work to create representations of American teenagers throughout the 20th century, while exploring the combination of portrait and still-life photography. Each pair of photos attempts to capture the essence of an individual decade.

The Grunge movement was a musical era and lifestyle originating in the Pacific Northwest in the early 1990s. Common lyrical themes included emotional turmoil and social isolation, resonating with teenage sentiment and alternative youth. Popular bands like Nirvana gained immense recognition, selling out shows all over America.

60s 90s

1960s America experienced a rise in political and social counterculture. Adolescents spent the day protesting war movements and the night dancing away to rock and roll. Fashion was influenced by a contemporary relaxation of strict moral codes.

10 The Lowell February 2023

PHOTOS BY

MARLENA ROHDE, KATHERINE KASPERSKI, KAHLO FRIEL-ASAY, AND ELISE MUCHOWSKI

In the 1980s, New Wave music rose to popularity. Teens shared music, as well as fashion, with each other as this scene developed. The Camcorder was invented in 1980, allowing youth to capture what life was like at the time.

80s

America in the post-World War II years saw a period of prosperity and technological advancement, as well as the growth of Cold War politics and ideas. Teen counterculture thrived as young people produced pamphlets, listened to new records, and pushed the boundaries of fashion.

The Lowell February 2023 11 40s

SPREAD DESIGN BY ELISE MUCHOWSKI

HIGH SCHOOL MUSICAL 3: SENIOR YEAR

By Aaliyah Español-Rivas

By Aaliyah Español-Rivas

While it was na

ive to hope high school would be like “High School Musical,” I real ized if there was one thing the franchise got right, it was their interpretation senior year. “High School Musical 3: Senior Year” portrays the complicated journey seniors face, when trying to figure out what they want in life before entering the real world.

Jammed into two hours, viewers are brought through the final months of the East High students, focusing on the journey of Troy Bolton (Zac Efron). Saying goodbye isn’t easy, and with time running out, all of the characters grapple with conflicting emotions that encapsulate how all seniors feel.

Nonetheless, as real as the emotions may be, it wouldn’t be a “High School Musical” movie without the overdramatized sequences. During the song “Now or Never,” Troy is in his final high school basketball game, with 16 minutes left to win the championship. This intense moment is accompanied by lyrics like, “the way we play tonight is what we leave behind,” and “this is the last chance to get it right, history will know who we are.” Cheesy and dramatic as it may seem, this isn’t a rare feeling. Troy and his teammates are simply expressing emotions in their fight with the clock. When the buzzer rings, it marks the end of their high school career, and for Troy, whose future of college basketball is uncertain, this may be Troy’s final time playing basketball. This song encapsulates the heightened emotions felt during final events in your senior year. You can’t help but to think that this is your last time doing something, and you never want to leave.

In the song “Right Here Right Now,” sweethearts Troy Bolton and Gabriella Montez (Vanessa Hudgens), sing about how they both just want time to stop. From winning the championship game to Gabriella’s early acceptance to Stanford, resulting in an early departure from school, Troy and Gabriella feel like time is slipping away. With graduation mere months away, it isn’t wrong for them to wish for endless time with one another. Knowing they won’t attend the same college, the two are grasping to any time they can spend together. Choosing to ignore the clock ticking, they imagine a world where they can stay in that moment forever, together. Wheth-

er or not one has a significant other, the feeling of wanting to never leave high school is a shared sentiment as you reach graduation.

The climax of the movie arguably contains the most relatable and over-the-top song in the entire “High School Musical” catalog. “Scream” is a song all about Troy’s internal conflict throughout the whole series: singing or basketball? After receiving a possible offer from Julliard, his father pressuring him to play basketball for the University of Albuquerque, and his girlfriend deciding to permanently stay at Stanford until graduation, Troy is clueless about what to do with his life. Angrily running around an empty school while the halls rotate on a stormy night, Troy reaches a turning point in his adolescence: he finally has the power to choose his path, but at what cost? Troy knows he loves basketball, but can not deny his love for theater. He doesn’t want to disappoint his father, but knows he must be true to himself. At this point in the movie, it becomes clear that these characters aren’t ready to graduate. But the show must go on. In the final moments of the film, Troy gives his valedictorian speech, where he announces his decision to attend the University of California at Berkeley, to pursue basketball and theater. Not only this, but it is 32.7 miles away from Gabriella, his girlfriend, who inspires him the most.

Ultimately, “High School Musical 3” accomplished its goal. While, yes, it is truly amazing to think that Troy and Gabriella are lucky enough to attend colleges so close to one another, it’s unrealistic. And yet, that’s what makes the movie so comforting. As seniors, you can’t help but think about the clock that’s counting down the days until graduation. You reflect on the final memories that you make, the future ahead of you, and contemplate which path you should take. It is, without a doubt, fun to live through these characters vicariously, but there the movie maintains a high level of relatability. “High School Musical 3: Senior Year” is comforting in the sense that even if these moments in your final months of high school aren’t accompanied by a song, you aren’t alone in feeling the way you do. As a senior, this movie is painfully relatable. And just like the seniors in East High, I want the rest of my life to feel just like a high school musical.

The Lowell Month Year MEDIA REVIEW The Lowell February 2023 12

“It is, without a doubt, fun to live through these characters vicariously, but there the movie maintains a high level of relatability.”

IMAGE COURTESY OF WALT DISNEY PICTURES

SOMETIMES

I MIGHT BE INTROVERT

By Roman Fong

Little Simz’s Sometimes I Might Be Introvert was not what I was expecting. Based on the title, I expected it to be serene and self-reflective, full of mellow beats and smooth vocals. While definitely self-reflective, it’s also emotional, loud, and blatantly unapologetic, filled with honesty and truth about wider issues. She uses this album to open up conversations about issues surrounding parent abandonment, class division, and flaws within the music industry.

the reflection that he hated, the part of him he wished God did not waste time creatin’, the broken homes in which we’re coming from but who’s to blame when you’re dealt the same cards from the same system you’re enslaved in?” Comparing her rough childhood to the boy’s life, Little Simz criticizes how people living in less-privileged environments are given no other option than resorting to violence. Little Simz’s complex lyrics are full of honesty and lead the listener from being angry at the boy to feeling sympathetic. This reinforces her plea for listeners to do the same in the real world and look at all sides of the story.

jjj\\\\\|jjjNigerian-British rapper Simbiatu Ajikawo, who goes by the stage name “Little Simz,” dives into her traumatic past in the emotional “I Love You, I Hate You.” As Little Simz struggles to get her thoughts out, she asks herself: “How many times did I cry for this? I would hate myself if I didn’t try for this.” Little Simz opens up about her rocky relation ship with her father, revealing the wound that he inflicted. She writes, “Never thought my parent would give me my first heartbreak.” She acknowledges her hesitancy to con front the issue, trying to build the confidence to get her thoughts out – finally speaking directly to her father with the gut-wrenchingly vulnerable line, “Is you a sperm donor or a dad to me?” She uses their relationship to emphasize the harshness of reality, calling her father out for running from his responsibility to care for his family, but also herself for running away from having this discussion.

In “Little Q, Pt. 2,” Little Simz tackles the issue of class division. She tells her cousin’s story of being stabbed, stress ing the idea that blame shouldn’t instantly be put on the less fortunate. Using the boy who stabbed her cousin as the prime example, she looks back on her own life, saying, “I could have been

Little Simz then goes on to criticize other issues within the music industry, specifically regarding the lyrics of other artists. In “Standing Ovation,” Little Simz claims many artists often get caught up in the fame and romanticize violence and criminal activity with their lyrics, “Rapping about pieces” (a slang term for firearms), when “people are really dying, is that what’s needed?” Little Simz boldly compares her work to theirs, condemning the artists for their insensitive subject

SPREAD DESIGN BY AALIYAH ESPAÑOL-RIVAS

AALIYAH ESPAÑOL-RIVAS

SPREAD DESIGN BY AALIYAH ESPAÑOL-RIVAS

AALIYAH ESPAÑOL-RIVAS

matter and warning fans not to exchange meaning for hype – instead, to appreciate the “Overachievers in the shadow of the gatekeepers.”

Overall, Little Simz’s SometimesIMightBe takes on large and complicated issues and makes them relatable, universal, and real. Backed by stunning orchestration and soulful beats, Little Simz’s emotional lyrics take center stage, culminating in meaningful and expressive songs that contribute to what Sometimes I Might Be Introvert truly is – a compelling and breathtaking journey into Little Simz’s mind.

The Lowell Month Year

The Lowell February 2023

SPREAD DESIGN BY

13

“This reinforces her plea for listeners to do the same in the real world and look at all the sides of the story.”

“While definitely self-reflective, it’s also emotional, loud, and blatantly unapologetic, filled with honesty and truth about wider issues.”

The Lowell February 2023

IMAGES COURTESY OF LITTLE SIMZ

SPREAD DESIGN BY

Bridging the gap for

14 The Lowell February 2023

English learners

By Darixa Varela Medrano

Since Lowell’s demographics have changed, the demand on its English Language Development program has increased, resulting in a lack of support for students struggling to communicate fluently in English.

The Lowell February 2023 15

ILLUSTRATION BY KATEY LAU

SPREAD DESIGN BY MARLENA ROHDE

In her World History class, freshman Kimberly Lopez sat alone. Her tablemates were standing across the room, analyzing articles their teacher had taped to the classroom walls. None of them had asked her to join them, and having moved to San Francisco from Mexico only four years earlier, Lopez wasn’t yet confident enough speaking English to approach them or contribute to the discussion. Her peers felt distant. To Lopez, her lack of English proficiency had formed a wall between her and other students.

This uncertainty about interacting with others due to language barriers is a shared feeling among Lowell’s English Learner (EL) population, students who struggle to communicate fluently in the English language.

When comprehending English becomes an obstacle in their social and academic lives, EL students risk falling behind in school and failing to connect well with their peers. To support these students, California mandates public schools to have an English Language Development (ELD) program that provides them with specialized aid. However, to English Learners at Lowell, this program often isn’t enough to optimize their learning experience and wellbeing. They believe that additional and reformed assistance from students, teachers, parents, and administrators alike are necessary to create a more inclusive environment.

Lowell first implemented its ELD program in 2017, following the enactment of Proposition 58 in 2016, which

mandated that all California public schools provide students with access to ELD programs. Students of various backgrounds who have difficulty speaking English — whether they are recent immigrants or come from non-English-speaking households — are brought together for this program. SFUSD has structured the program for EL students to have both designated (D-ELD) and integrated (I-ELD) classes. In designated classes, ELs are provided with instructions modified to develop their English. These designated classes are currently limited to Heath, Ethnic Studies, and Communications and Writing. Integrated classes refer to the rest of Lowell classes that are not formed solely for ELs, where they are able to intermingle with the rest of the student body.

Navigating the larger Lowell community is a daunting task for English Learners. According to Lopez, she has yet to make strong connections with peers in her integrated classes. While she hopes the cause may be that it’s still her first year at Lowell, she’s noticed that her lack of fluency speaking English has caused her to shy away from socializing with other students. In some cases, she feels that she is outright being mocked for her lack of fluency. “I get embarrassed to ask others questions in case I say something wrong in English,” Lopez said. “It makes me so scared because there are sometimes bad people who make fun of me for that.” According to Amy Crosson, Associate Professor of Education at Pennsylvania State University, this fear has consequences that go beyond

The Lowell Feburary 2023 16

FEATURE

Kimberly Lopez often feels isolated from peers because of the language barrier.

the inability to befriend other students. “If a student doesn’t have an opportunity to participate in a discussion, they don’t have that opportunity to articulate their understanding and get feedback and sharpen their thinking,” she said. “The longer-term would be kind of a demotivating effect.” According to Crosson, because of these events, EL students are more likely to start believing that they’re incapable of pursuing higher education.

In the classroom, having trouble understanding lessons also causes EL students to fall behind on course material. In the 2021-2022 School Plan for Student Achievement (SPSA), the graph for students’ grades based on English proficiency showed that 17 percent of ELs at Lowell obtained D’s or F’s, compared to 9 percent of the rest of the student population. “When I don’t understand the work and I’m too shy, I feel like I’m not as smart as others,” Joseph Pacheco said, a freshman in the ELD program. He hopes that teachers will take more time to clarify their lessons as much as possible for EL students to understand.

Lowell’s ELD program aims to support English Learners through both these academic and social difficulties. Lopez and Pacheco both agreed that the program has led to improvements in English fluency. According to Lopez, having a small group of EL peers in their designated group who understand each other’s backgrounds and struggles provides emotional solace. Learning alongside these students in her designated ELD classes also gives her confidence. “It’s a very nice community,” she said. “I feel very comfortable speaking English there.” It is because of this level of comradery that ELs are less likely to shy away from the tasks they’re given and speak up. However, they still have yet to reach that same level of relief in their integrated classes.

While the program provides a safe space for many students, Pacheco believes that the instructional aspect of it

and interact with peers.

The number of students enrolled in the ELD program saw a slight increase after Lowell switched to a lottery admissions system for the 2021-2022 school year. According to the School Accountability Highlights report of 2021-2022, 3.5 percent of Lowell students were reported as ELs out of

“I get embarrassed to ask others questions in case I say something wrong in English.”

2,662 enrolled students, a 1.4 percent rise from the constant 1.9 percent reported in both 2019-2020 and 2020-2021. This increase didn’t go unnoticed by ELD coordinator and English teacher Jacqueline Moses, who oversees the program and advises teachers on how to best support EL students. Moses was assigned to teach two smaller designated Communications and Writing classes as opposed to one large one. The number of students in the ELD grew again for the 2022-2023 school year.

With this increase in ELs, so came an increase in issues with accurately classifying their English proficiency. The ELD program is heavily dependent on data obtained from students’ assessment tests, specifically the English Language Proficiency Assessments for California (ELPAC), which is administered between February 1 and May 31. Since the students were preparing and taking the ELPAC during the COVID-19 pandemic, many of them had to take the test online. The lack of a proper testing environment decreased the accuracy of the data collected. “None of that situation was an ideal testing environment,” Assistant Principal Jan Bautista said.

The misleading data on the students’ proficiency made it more difficult to give them the proper amount of support. This was especially true in terms of classroom placement. “Some of the students don’t necessarily need to be in Communication and Writing as their levels were higher,” Moses said. “It kind of shut the door for those who could have been in that class.” Moses has had to reach out to counselors and teachers who report having students falling behind due to their lack of English proficiency, while, at the other extreme, students that were held back despite being proficient enough have to stay in the ELD program until they retake the ELPAC or opt to drop out of the program themselves.

PHOTOS BY KYLIE CHAU

could be improved. He wishes that ELD would provide students with more speaking practice, rather than focusing on reading and writing in his Communications and Writing class. According to Pacheco, shifting the program’s focus to verbal communication would help him and other EL students gradually overcome their reluctance to ask teachers for help

For some EL students, having teachers in their integrated classes who don’t understand their individualized needs has posed a problem. Lopez recalled a time when a Lowell teacher wouldn’t allow her to communicate with the class through Google Translate, a translating app that allows her to clearly express her doubts and stress. According to

The Lowell February 2023

SPREAD DESIGN BY DYLAN TWYMAN 17

Uncertainty about interacting with others due to language barriers is a shared feeling among Lowell’s English Learner (EL) population.

Crosson, while using Google Translate might feel distracting during class, this technology can be necessary for an EL student who may not be able to articulate their thoughts effectively, due to the language barrier. “I think that there are many moments when it can be really elucidating and helpful and support learning to use those kinds of technologies,” Crosson said.

According to Moses and Crosson, in order to better understand the needs of EL students and best support them, it is essential that educators receive proper training. Moses regularly attends seminars that teach her how to create an inclusive learning environment, peruses specific teaching sites, and reorients herself to be more empathetic toward students’ individual circumstances. While these types of training may be effective, Crosson offers a different perspective. “Maybe even better than taking classes would be to be connected to a teacher who is knowledgeable about working with multilingual learners, language acquisition, and some of the instructional practices that support kids to thrive academically,” Crosson said. As coordinator of Lowell’s ELD program, Moses expressed her willingness to share what she has learned with fellow teachers to better help EL students.

In addition to teachers, parents also have unique opportunities to support English Learners. Bautista and Moses regularly recruit parents of Lowell students to join the English Learner Advisory Committee (ELAC), which leads the formation and design of the ELD program. “Parents have

the right to be able to advocate for how we spend money to support EL students,” Bautista said. Every year, ELAC holds a meeting to discuss data about EL students, their own perspectives as their parents, and each student’s reclassification progress. Using this information, ELAC writes up suggestions for the principal to use when budgeting and planning courses for the program. According to Bautista, this could open opportunities for teachers to have smaller designated classes and receive more training.

Another pressing concern ELAC aims to address is the limited amount of counseling resources available to Lowell students. To Bautista, a student’s first instinct when they’re upset or concerned at school is to turn to counseling resources. “The blanket thing is to go to your counselor, or Wellness, or the school nurse,” she said. However, according to Bautista, the lack of a school nurse and Wellness Center coordinator limits the accessibility and availability of support for EL students navigating high school. ELAC hopes to continue their advocacy to hire more support staff for EL students.

The ELD program faces multiple challenges and limitations to how much it can serve students. However, Moses and Bautista believe change is possible if teachers, parents, and students remain involved in the process. Until then, ELD students may continue to have similar emotions as those expressed by Lopez. “I have felt a little bit of rejection, but I don’t know if it’s me, or that they don’t understand me, or don’t listen to me,” she said.

The Lowell Feburary 2023

18

Lopez struggles to form connections with peers.

HOT TAKE

OVERPRICED AND OVERWROUGHT

BY LIBBY BOWIE

BY LIBBY BOWIE

There are few items that encompass my utter hatred for ugly footwear and uglier prices more accurately than the near-thousand dollar Tabi boots. For those lucky enough to have never set eyes on these monstrosities, they’re split-toed boots made of upscale leather that not-sosubtly resemble horse hooves and camel toes. They look like a slightly more socially acceptable (emphasis on slightly) version of toe socks – except they’re $990 at minimum and are considered fashionable. Aside from maybe giving these shoes to Grover, the satyr from Percy Jackson and the Olympians, to complement his goat feet beautifully, I can’t think of a single instance where these shoes would be appropriate.

However, my concern is less about the look of the shoes themselves and more about what this trend could mean for fashion in the future. If horse-hoof boots become the standard, who’s to say that million-dollar lizard-toe sandals aren’t next? Our society can’t survive an overpriced animal footwear trend. The economy might collapse under

the weight of thousand-dollar ferret shoes, everyone would eventually be driven mad by the constant sight of atrocious footwear, and the world as we know it would be thrown into chaos.

For some consumers, the thousand-dollar price tag and the promise of participating in a niche, high-end fashion trend is enough for them to overlook the fact that Tabis look like high heels for horses, playing into the idea that expensive and designer always means better. These shoes symbolize the rising popularity of unnecessarily expensive fashion trends that are creating a metaphorically gated fashion community. Fashion shouldn’t be about whether or not you can afford the next wildly expensive, trendy pair of shoes; it should be about individualism and self-expression.

The Lowell February 2023 19

SPREAD DESIGN BY LIBBY BOWIE

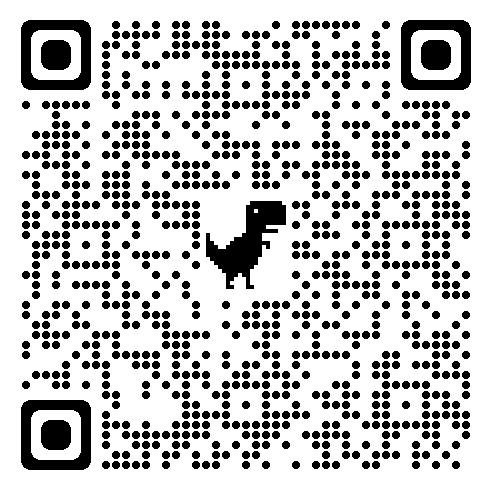

DO YOU WANT YOUR AD IN THE NEXT ISSUE OF THE LOWELL? EMAIL US AT THELOWELLMANAGEMENT@GMAIL.COM OR SCAN HERE TO LEARN MORE :

MY SILENT PROTEST

PHOTO BY AVA ROSOFF ILLUSTRATION BY ELISE MUCHOWSKI

PHOTO BY AVA ROSOFF ILLUSTRATION BY ELISE MUCHOWSKI

As the teachers finished organizing us into our class lines, everyone quieted down for the morning assembly. Our necks straining to watch the cues of the lead drummer, we began proudly harmonizing to the Tibetan national anthem. But as I was singing along, a flash went off from the corner of my eye. Suddenly, the loud beats of the drum became a faint background noise as the pounding of my heart took over. I slowly turned my face away from the camera, as I began to feel my hands shake uncontrollably.

Although this was a typical Sunday school morning assembly routine, my fear of being photographed while participating prevented me from singing along.

Growing up, I often heard stories of people inside Tibet being punished for the political involvement of their relatives abroad. Because I have close relatives that live there, I began restraining myself from participating in certain Tibet-related activities, such as the annual uprising protests

and religious community events. The only methods of protesting I could participate in felt ineffective, as they were always silent and non-political. But as I grew older and my view of the world expanded, I realized that by just keeping my language and culture alive, I was positively contributing to the greater Tibetan struggle. Although I initially felt purposeless in the Tibetan movement, I eventually learned that I didn’t need to protest in public in order to make a difference. Instead, I realized that there was value in keeping the nonpolitical aspect of my Tibetan identity alive.

People’s Republic of China in 1949 resulted in the loss of its independent status. As the Tibetan people do not recognize the Chinese government’s legitimacy in Tibet, numerous uprising and coup attempts have been made. Consequently, Beijing strictly controls this region, heavily cracking down on any form of protest and cautiously monitoring its internet for signs of resistance.

To fully assess the scope of the Tibetan-Chinese conflict, you must understand the historical relationship between these two neighboring nations. Although the Tibetan empire dates back to prehistoric times, its invasion by the

If I were to be publicly politically involved in the TibetanChinese conflict, my family in Tibet would face unjust suspicion by the Chinese government. Actions such as participating in protests calling for the independence of Tibet or showing respect to the Dalai Lama (Tibet’s spiritual leader) could cause my relatives inside Tibet significant trouble. These relatives, which include my aunt and her family, could be put under constant scrutiny from officials. If incriminated, they could lose their jobs, homes, and even their children. So when I realized that the photo of me singing the Tibetan

20 The Lowell February 2023

I FEARED FOR THE SAFETY OF MY FAMILY IN TIBET.

COLUMN

national anthem could be used as a weapon to attack my aunt and cousins, I feared for the safety of my family in Tibet.

My parents and I have always resisted the Chinese government in a more private manner. Even as Americans, we can’t attend independence rallies or join any Tibetan organizations in fear for our relatives in Tibet. Instead, we’ve studied our language and preserved our culture as much as possible. Although this has no major or immediate political effect, it is a silent protest of the Chinese assimilation of the Tibetan people and culture. But for as long as I can remember, I have been self censoring my words, thoughts, and actions.

Because I have always been aware of the consequences my aunt’s family could face in Tibet for my actions, I have kept myself isolated from political events. In addition to having never participated in an independence rally nor being present at any heavily politicized event, I have even stopped myself from going to community concerts because of the highly political hosts. Recently, I became exhaustively aware of how much I was restraining my words and actions when I rejected a friend’s invitation to attend Tibet Lobby Day. Tibet Lobby Day is an annual three day event hosted by the Students for a Free Tibet organization. Tibetan Americans from multiple states went to Washington D.C. and talked state representatives into supporting the Tibetan cause. As well as being a great opportunity to connect with senators and representatives to push for Tibet related bills, it was also a rare chance to network with young Tibetan American students and professionals that live across the country. As I watched daily updates of the lobbying event through social media, knowing that I couldn’t participate because of the jeopardy it might’ve put my aunt’s family in, I felt completely useless and isolated from the greater Tibetan struggle.

However, as I began to notice increased methods of silent protesting in recent years, my initial rejection of this technique’s effectiveness was

altered greatly. Last fall, an apartment fire in Xinjiang resulted in the death of 10 residents. Because of zero-Covid policies in place, firefighters at the scene were not allowed to interfere with the disaster, sparking mass protests across China. To counter relentless online censorship, citizens of major cities like Beijing, Shanghai, and Chengdu resorted to several days of blank paper protests. Instead of signs with political slogans, protestors held up blank sheets of white paper, symbolizing the lack of freedom of speech in China. These pieces of paper represented the Chinese people’s criticisms to the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) that they could not safely vocalize. As I realized this sentiment, I was reminded of the ways that I couldn’t speak up for myself and my country. I began to understand that my silent struggle against the CCP was not an isolated one. Across several countries, Chinese citizens showed up to protests with covered faces and blank paper. They understood the risk of vocalizing their dissent, and still had shown up in a literal silent protest.

The Tibetan youth inside Tibet had also found a solution. Right around the time of the blank paper protests, I participated in a non-political engagement conference bridging the gap between the Tibetan youth inside Tibet to those abroad. Here, I was introduced to several community-based projects that Tibetan youth were involved in. Although it was never directly stated, many of these projects were methods of silent protest. For example, a group of students had created a Lhasa (Tibet’s capital) map initiative. Although on the surface, it just seemed like a map project that recorded Lhasa’s layout, it was, in reality, one of the only ways to save the parts of cultural architecture that had increasingly continued to disappear

as the Chinese tightened their grip on Tibet. The Lhasa map initiative created three dimensional models of the ancient city’s layout, accompanied by videos explaining the historical and cultural significance behind each of the roads, buildings, and religious structures such as temples. Additionally, I was introduced to the concept of Tibetan hip hop, which used music to keep hold of one’s identity. The underlying message in Tibetan hip hop was to tell the Tibetan youth to be proud of their language, culture, and identity. Through the universal language of music, this message continues to resonate well with the Tibetan youth both in Tibet, China, and abroad.

Gathering inspiration from the Chinese citizens and the Tibetan youth inside Tibet, I have focused my attention onto my own ways of silent protesting. Through my cultural interests in the ancient linguistic system to the extensive medicinal and psychological practices, I began working to keep these elements of our culture alive. I intend to document and translate these aspects of our culture into the English language so that the next generation of TibetanAmericans can easily access them, even if a language gap occurs.

Censoring myself as an American has always been something I despised of my Tibetan background. Nonetheless, my recent observations and experiences of the silent resistance methods used by Chinese and Tibetan people have comforted and inspired me. It has always been a challenge to quietly resist, but now that I know that I’m not alone, I see this as an opportunity, rather than a challenge. Like the Chinese protestors who used blank pieces of paper and the Tibetan youth who use rap to keep their identity alive, it is now my turn to discover where I fit in as a silent but hopeful fighter.

SPREAD DESIGN BY LIBBY BOWIE

The Lowell February 2023 21

I REALIZED THAT BY JUST KEEPING MY LANGUAGE AND CULTURE ALIVE,

I WAS POSITIVELY CONTRIBUTING TO THE GREATER TIBETAN STRUGGLE.

1 2 3 4 5 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 15 16 17 STARCROSS(WORD)ED LOVERS DISCLAIMER: If you are found leaking crossword answers via social media or any online platform, you will be ineligible for any and all rewards. ACROSS 2. Romantic dinner theme 5. Staple item in John Cusack’s romantic gesture 6. Unoriginal Valentine’s Day gift found at your local CVS or Walgreens 7. City of love, and the setting of the Aristocats 8. Valentine’s date 9.“Valentine’s Day is a _______ holiday.” - critics 12. Serial people-eater in a 1991 psychological thriller released on Valentine’s Day 15. 14 line love poem 17. Love at ______ _______ DOWN 1. State where you might see “10s” 3. Beats 4 u ;) 4. For Lowell Valentines 7. Object thrown at a window to grab a lover’s attention 8. Hugs & kisses! 10. Sign of Valentine’s Day 11. Olivia Rodrigo once sang, “White flowers and ___ ____” 13. Text found on conversation heart candy 14. Ero’s Roman counterpart 16. Birth month for “Valentine’s babies” Submit your completed crossword to the QR code for a chance to win a portable charger! ILLUSTRATIONS BY JOEY HE

CROSSWORD AND SPREAD DESIGN BY LIBBY BOWIE

BY MARSHALL MUSCAT

BY MARSHALL MUSCAT

BY LAUREN KIM, KAHLO FRIEL-ASAY, AND YESHI-WANGMU SHERPA

BY LAUREN KIM, KAHLO FRIEL-ASAY, AND YESHI-WANGMU SHERPA

SPREAD DESIGN BY DYLAN TWYMAN

SPREAD DESIGN BY DYLAN TWYMAN

By Aaliyah Español-Rivas

By Aaliyah Español-Rivas

BY LIBBY BOWIE

BY LIBBY BOWIE