Welcome to Issue 45 of The Meducator! The healthcare field is rapidly evolving, with new discoveries and advancements emerging everyday. This embodies a modern-day Renaissance—an era characterized by profound shifts in social attitudes and scientific innovation. Henin Ye captures these principles in her illustration of Issue 45’s cover, inspired by Michaelangelo’s iconic Renaissance masterpiece, The Creation of Adam. Likewise, we extend a hand in joining us in exploring revolutionary connections and transformations unfolding in the medical field today, through our winter issue.

Editors Dominic Gangemi and Ria Patel begin Issue 45 by describing novel health developments worldwide, including the first FDA-approved Chikungunya vaccination in Brazil and Canada’s research on modelling pexophagy pathways to treat neurodegenerative diseases. We continue The Meducator’s collaboration with the International Women and Children’s Health Conference by featuring abstracts from Brittney Davy on Black women’s health and Deepikaa Jeevanthan on the vaginal microbiome. Through extensive literature review, Florence Deng and colleagues describe the pathophysiology and treatment landscape of Crohn’s Disease. In a Critical Review, Morgan Puusaari and colleagues describe a novel α-synuclein seed amplification assay for early detection of Parkinson’s disease.

In this issue we are excited to feature articles that explore health from a multifaceted perspective. In MeduAmplify Local, Parth Arora and colleagues characterize Hamilton’s opioid epidemic and potential response strategies. In another MeduAmplify, Aditya Misra and colleagues discuss the ‘orange jumpsuit’ stigma by exploring the health of incarcerated peoples.

We take tremendous pride in our journal’s emphasis on diversity in healthcare. In a MeduAmplify, Veronica Grignano and colleagues explore the evolution of art in medicine, highlighting the underrepresentation of marginalized bodies in anatomical illustrations. Meanwhile, artists Arim Yoo and Elaine Wang present “Echoes of Representation,” a centrefold illustration depicting how predominantly white representation in medical textbooks affects clinical practice.

We extend our heartfelt appreciation to our 95 talented staff, executive members, faculty reviewers, and the McMaster community for their invaluable partnership throughout the 45th publication cycle. Finally, we offer our sincerest appreciation to you, our reader, for your continued support of our publication. We feel privileged to have served the McMaster community. We wholeheartedly welcome Florence Deng and Anna McCracken as the Editors-in-Chief for the upcoming academic year. We believe their potential is unlimited and cannot wait to see them uphold and advance the Meducator’s legacy.

Improved cellular recycling could benefit patients with neurodegenerative conditions

CANADA | January 2024

Researchers at SickKids Hospital are discovering new ways to treat neurodegenerative conditions. Zellweger Spectrum Disorders (ZSDs) are a set of rare inherited neurodegenerative diseases characterized by dysfunctional peroxisomes: organelles commonly used in lipid metabolism. the autophagic degradation of peroxisomes, was analysed to model similar selective autophagy pathways. showed that similar ‘recycling pathways’ could not effectively break down other cellular waste.2 Their findings extended to in vivo cell models of ZSD and other neurodegenerative conditions, like Parkinson’s Disease and Huntington’s Disease.2 Hence, therapeutically enabling a cell to better recycle its own components could reduce the accumulation of damaged cellular material.2,3

North Carolina’s Duke University is now home to the first ever heart valve transplant that has grown with its neonate recipient for one year.4 Dr. Joseph Turek sought to address the issue of recurrent implant exchanges for children born with irreparable heart valve dysfunction as their heart grows with age.5 A partial heart transplant from a neonate donor provides the ideal treatment since the patient now requires fewer immunosuppressants and further surgical intervention is minimized. door to more life-saving partial heart transplants, tissue engineering of heart valves, and the potential for domino transplants where a single heart can save multiple patients.

Chikungunya vaccination could help millions in South America

BRAZIL | November 2023

Originating from Tanzania in 1953, mosquito-borne chikungunya virus—“disease that bends up the joints” in Swahili—is characterised by severe joint pain. tropical disease has spread across Africa, Asia and, notably, South America, which faces an ongoing epidemic with an estimated total of 3.7 million cases. the form of the first FDA-approved chikungunya vaccine, called Ixchiq, developed by Valneva. shown that 99% of people develop long lasting antibodies after a single shot.11 Discussion around vaccine rollout, prioritising South Americans or tourists, is ongoing.

TheFightingTemeraire, 1838 (England)

Untitled, 1999 (Uganda)

DOMINIC GANGEMI 1 & RIA PATEL 1

Bachelor of Health Sciences (Honours), Class of 2027, McMaster University & CHRISTINA TAM 3

Bachelor of Health Sciences (Honours), Class of 2024, McMaster University

Bachelor of Health Sciences (Honours), Class of 2026, McMaster University

A groundbreaking study led by Genomics England has shown that whole-genome sequencing (WGS) could be the key to more precise and personalised cancer treatments.12 The Cancer Programme of the 100,000 Genomes Project, initially announced in 2012, analysed WGS data from 13,880 solid tumours across 33 types of cancers.12,13 From this data, researchers found that over 90% of tumours in the brain, and over 50% in the lungs or colon, exhibited genetic alterations that would impact patient treatment.14 Furthermore, 13% of 1,617 sequenced sarcomas expressed large structural variants.12 These discoveries help highlight precision oncology as a promising avenue for cancer treatment.

GallopingHorse, 1953 (China)

Prostaglandin degradation enzyme found to be potential therapeutic target for ischemic stroke

Researchers in China are paving the way for a new treatment for ischaemic stroke. Where standard treatments seek to catalyze plasminogen into plasmin to dissolve blood clots, this research targets an enzyme responsible for the degradation 15‐Hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase (15‐PGDH) is the degrading enzyme of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), which has been shown to be important for the control of When inhibited, new research shows the activated PGE2/EP4 axis transcriptionally upregulates vGPX4, a protein responsible for regulating cell death through ferroptosis.16,17 Therefore, inhibition of 15-PGDH alleviates ischemic stroke and, consequently, presents a promising therapeutic target for the near future.16

Novel model for rheumatic heart disease treatment

Rheumatic heart disease (RHD), a condition caused by chronic heart valve damage following rheumatic fever, is the leading cause of heart disease for youth in Uganda.20 To streamline RHD screening and recurrent antibiotic admission, the Ugandan Ministry of Health is advancing the "Accelerating Delivery of Rheumatic Heart Disease Preventive Interventions in Uganda" It offers free RHD screening in schools, health centres, and community events from nurses and clinical officers who received training from experts at the Uganda Heart Institute.21 To improve secondary treatment times, Uganda moved their existing RHD registry from a centralised location to the Uganda’s exemplary work sets effective standards for global RHD treatment and situational public health action.

A collaboration with the 2023-2024 Women’s and Children’s Health Conference at McMaster University

ARTISTS: MISHAL HOSSAIN 1 & ARIM YOO 21Bachelor of Health Sciences (Honours), Class of 2025, McMaster University

2Bachelor of Health Sciences (Honours), Class of 2024, McMaster University

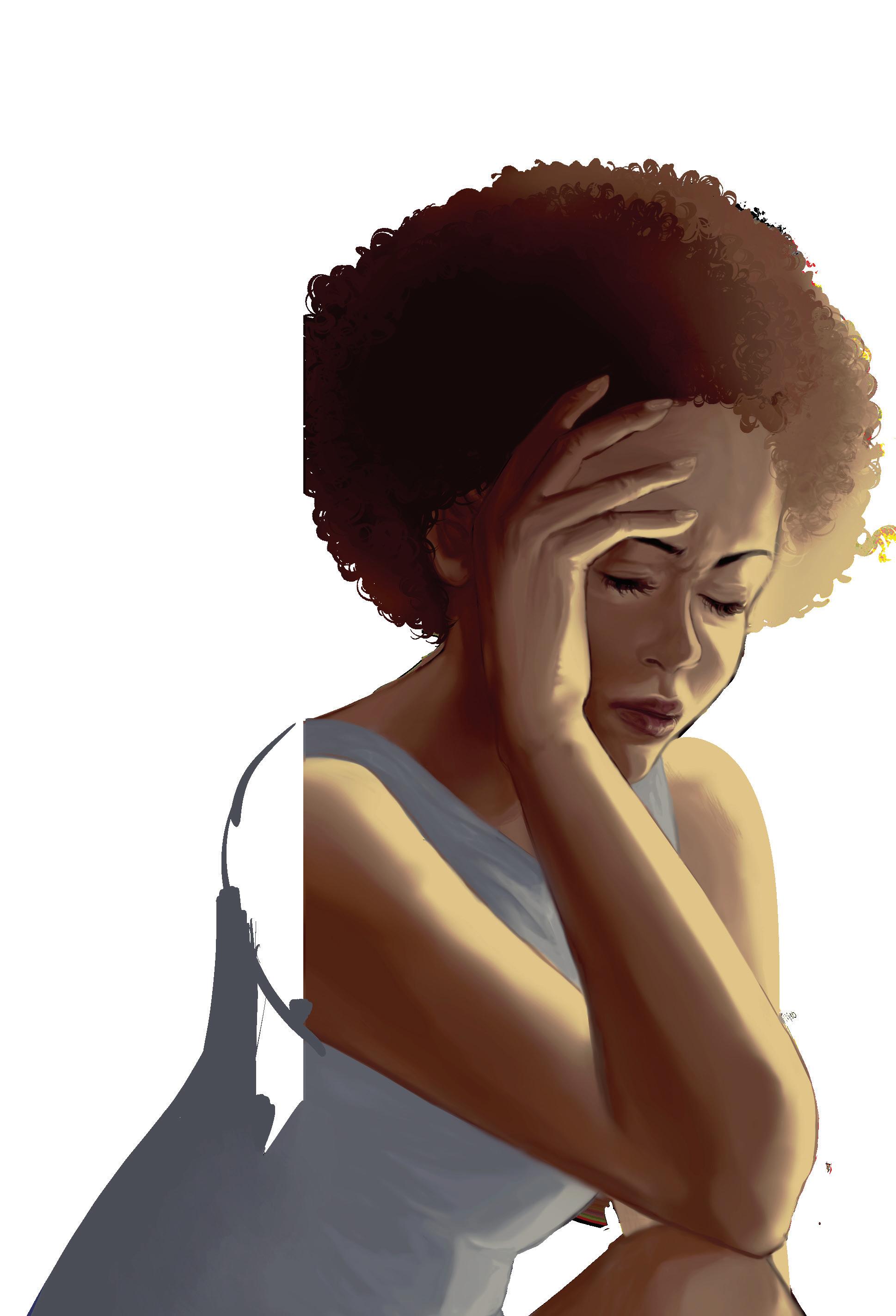

Black womens’ health matters: A literature review of the impact of racial stereotypical narratives on Black womenAUTHOR: BRITTANY DAVY (BCBA, MA ADS) 1 1Department of Health, Aging & Society, McMaster University

Black women have been disproportionately affected by negative stereotypical narratives and complex representations of their community. The “strong, Black woman” stereotype and many others which are contextually similar possess diverse meanings dependent on social context and lived experience. Studies exploring the implications of normative and stereotypical narratives of Black women on their health have revealed differences in health outcomes dependent on experiences and perception of these stereotypes.

This literature review explores a range of popular meanings attributed to similar racial stereotypes. The researcher, an Afro-Caribbean Black doctoral student in Ontario, examined published research in North America to highlight patterns in the positive and negative mental health experiences of Black women who have been exposed to common racial and gender-focused stereotypical narratives. Studies included in this review discussed the experiences of women that identify as Black members of African descendent populations including but not limited to African American and Afro-Caribbean, from various age groups as early as firstyear college students to women approaching old age (approximately 60 years old).

Researchers that have previously interviewed Black women within the North American context found that there were several theses associated with stereotypical narratives specifically applied to Black women: strong/assertive, independent, educated, hardworking/ambitious, caring, and self-confidence. Several Black women expressed their beliefs that internalizing and perpetuating strong, Black women traits has been a source of empowerment and promotes self-sufficient and resilient behaviour in this marginalized population. Comparably, these narratives can be particularly debilitating and oppressive as Black women may feel objected to altering their behaviour to fit within the boundaries ascribed by the stereotype. Other Black women have displayed symptoms commonly associated with depression, which have been correlated with their exposure to these stereotypes which have harmful effects on their physical and psychological health. Predominant stereotypes and lifestyle behaviours contribute to experiences of threatened mental health as society constantly reproduces unattainable images of an ideal.

Further investigation by the researcher is expected to reveal differentiated but interrelated results between the endorsement of Black women centered narratives and health experiences throughout the life course. This research is crucial as much of the published literature is conducted within the United States of America and the importance of the deep-rooted slavery history, culture, and covert racist treatment of Black people today may hinder the generalizability of the findings to the Canadian context. While Black women remain disadvantaged within Canada, literature regarding the impact of these stereotypical narratives on Black women within the Canadian context is underrepresented within published research.

AUTHORS: DEEPIKAA JEEVANANTHAN 1,2 , AISHA NAZLI (MSc, MPhil, PhD) 1,2 , & CHARU KAUSHIC (MSc, PhD) 1,2

1Department of Medicine, McMaster University 2McMaster Immunology Research Center, Michael G. DeGroote Center for Learning and Discovery, McMaster University

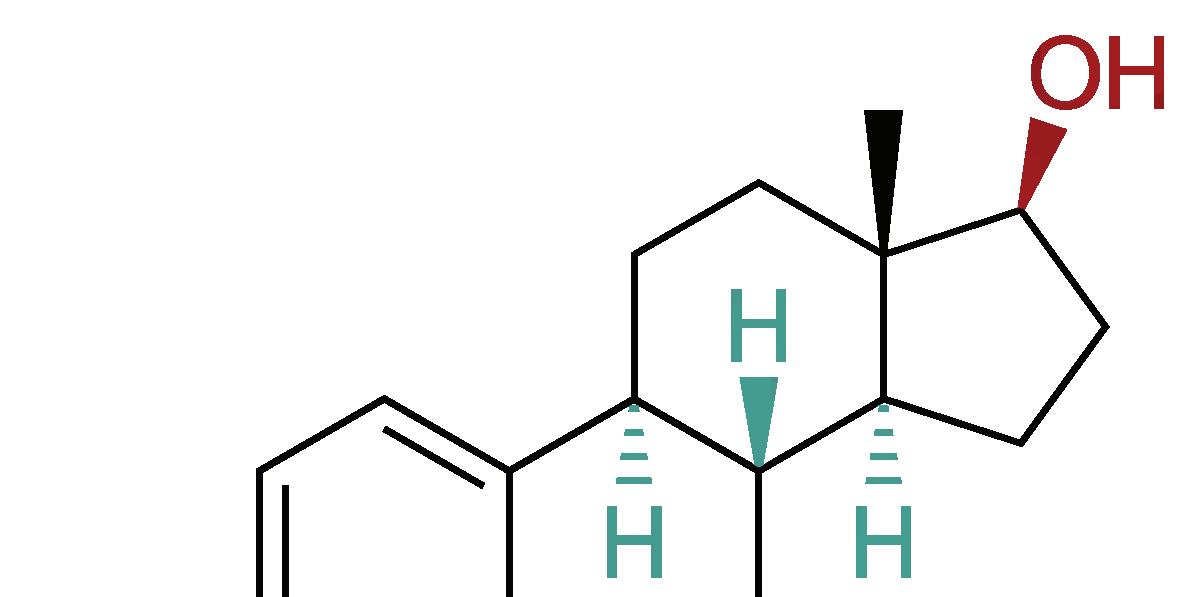

The prevalence of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) remains a major issue worldwide. The composition of the vaginal microbiome (VMB) has a crucial role in maintaining reproductive health. A eubiotic VMB is colonized by Lactobacillus crispatus and is considered protective against STIs. A dysbiotic VMB is populated by anaerobic species such as Gardnerella vaginalis, which are associated with increased susceptibility to STIs and often aggregate to form biofilms. With antibiotic resistance presenting an ever-growing concern, it is important to examine biofilm formation – one of the resistance mechanisms developed by bacteria to overcome clinical treatments. Biofilms are communities of aggregated bacterial organisms contained within a thick matrix of extracellular polymeric substance (EPS). The physical shield created by the biofilm EPS confers antibiotic resistance by protecting the bacteria and decreasing their response to antibacterial agents. The formation of bacterial biofilms by dysbiotic bacteria in the vagina can thus increase the likelihood of treatment failure and recurrence of vaginal infections. Investigating the important structural components of biofilms can help develop ways to target and disperse these communities, leaving bacteria less resilient and more susceptible to treatment. Extracellular DNA (eDNA) released by bacteria, either actively or through cell lysis, is considered to be an important component of biofilms. eDNA has been shown to be critical in bacterial attachment and aggregation of biofilms on surfaces, especially in the early states of biofilm formation. It also helps maintain the structural stability of the rigid biofilm matrix that protects the bacterial cells within. The role of eDNA in the VMB is not well-researched, but could be a target for disaggregation of biofilms. Determining the role of eDNA in biofilm formation and vaginal health can aid the development of treatments for recurring vaginal infections.

We assessed the timing of DNA release in 4 different bacterial species: dysbiotic bacteria Prevotella bivia and Gardnerella vaginalis, eubiotic bacteria L. crispatus, and an intermediate between dysbiotic and eubiotic state, Lactobacillus iners. The release of eDNA in the stationary-growth phase is indicative of bacterial lysis, while maximal eDNA release in the early exponential-growth phase is associated with active release mechanisms. We found that eDNA release in G. vaginalis only peaked in the early exponential growth phase, which represents active release, rather than bacterial lysis. In contrast, eDNA release in L. crispatus, P. bivia and L. iners peaked in the stationary phase, indicating release of eDNA after bacterial cell lysis. Currently, we are investigating the effects of eubiotic and dysbiotic bacterial eDNA on vaginal epithelial cells by assessing changes in vaginal epithelial barrier integrity, as well as immune factors induced by eDNA in vaginal cells. Preliminary findings have shown that eDNA derived from L. crispatus upregulates anti-inflammatory factors in vaginal epithelial cells, while eDNA from G. vaginalis and L. iners induces upregulation of pro-inflammatory factors. In the future, we will determine whether the eDNA of different bacterial species can modulate the inflammatory response in vaginal epithelial cells against an immune insult. This study will help to understand the role of eDNA in biofilm formation to potentially improve biofilm treatment options for women suffering from recurrent infections.

ARTISTS:

ARIM YOO 1 & ELAINE WANG 2

1Bachelor of Health Sciences (Honours), Class of 2024, McMaster University

2Bachelor of Health Sciences (Honours), Class of 2026, McMaster University

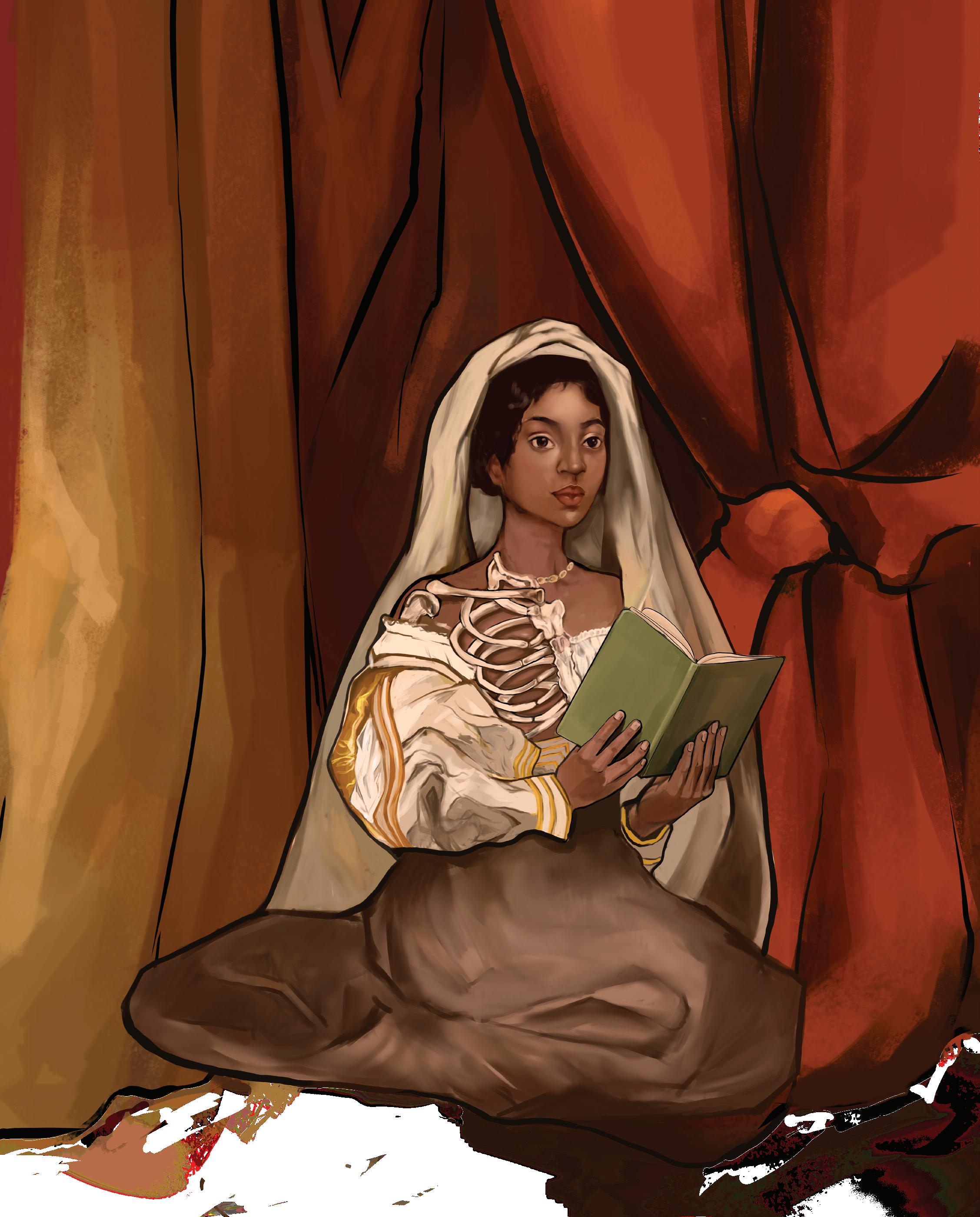

“ECHOES OF REPRESENTATION”

The representation of diverse bodies in medical illustrations has been consistently lacking throughout history. Medical textbooks, posters, and scientific models all tend to depict the white male body as the standard. In contrast, bodies of those who are Black, Indigenous, and People of Colour (BIPOC), fat, or disabled, are significantly underrepresented. In a 2021 study by Massie et al., it was found that just 18% of the medical images from the New England Journal of Medicine depicted non-white skins.1 It is necessary to improve diversity in medical illustrations in order to render medical education of both providers and patients more equitable for the underrepresented populations.

doi: 10.35493/medu.45.08

AUTHORS:

VERONICA GRIGNANO 1, MATTHEW OLEJARZ 2, & DEVLYN SUN 2

1Bachelor of Health Sciences (Honours), Class of 2027, McMaster University

2Bachelor of Health Sciences (Honours), Class of 2026, McMaster University

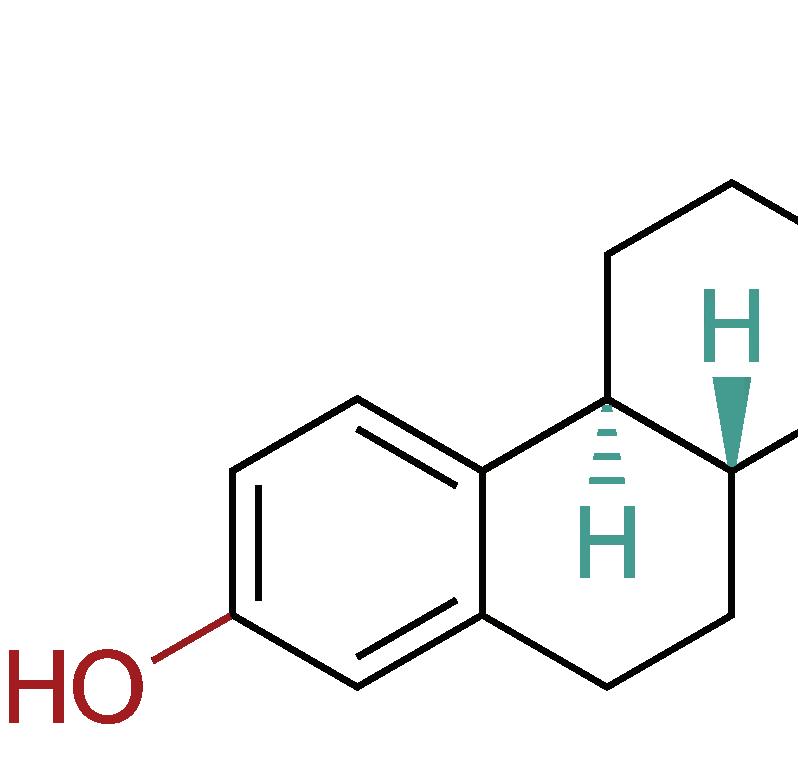

Across human history, the intersection between the visual arts and human anatomy has revealed an unlikely partnership between scientific accuracy and creative artistry. From historical anatomical sketches to current 3D medical models, the visual representation of the human form has facilitated the advancement of modern medicine throughout the world. This relationship has changed the methods of dissemination of healthcare information, aided in the understanding of anatomy, and led to anatomical accuracy in historical works of art. However, the methods by which artistic and anatomical knowledge have been acquired throughout history were not always ethical. In fact, nonconsenting marginalized populations were often the victims of human cadaver dissections that were later adapted to visual representations. Despite this fact, anatomical illustrations in historical and contemporary scientific texts still exhibit a lack of diversity and clear biases toward a depiction of the white male archetype. An improved understanding of the complex interplay between art, anatomy, and the abuse of marginalized groups in these fields is crucial to foster inclusivity and protect the rights and autonomy of all individuals involved in anatomical art–both in the past and the future.

EARLY DEVELOPMENT OF ART IN ANATOMY: A GLOBAL PERSPECTIVE

Although the Renaissance period is often cited as the era of anatomical revolution, it is important to note that advances in art and anatomy are not limited to this era, nor Western civilization. In fact, the convergence of art and anatomy dates back to over 25,000 years ago, with evidence of anatomical artifacts, sculptures, and drawings found in caves across Western Europe, Africa, Asia and Australia.1

Ancient Egypt

Some of the earliest records that contributed to modern knowledge of human anatomy are credited to the Ancient Egyptians. While their knowledge was crude, Ancient Egyptian sculptures and drawings marked a turning point where the perception of medicine moved away from a simple practice to a highly regarded and skillful craft.1

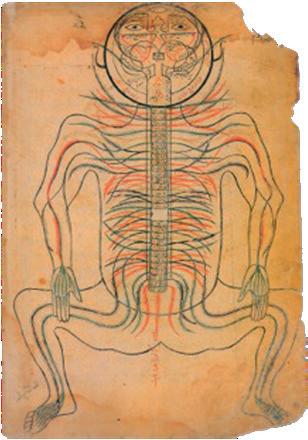

Persia

A Persian anatomist, Mansur ibn Elyas, is credited with publishing the first illustrations of the human body in its entirety in his manuscript, Tashrih-i Badan-i Insan. The book contained six coloured figures, each detailing a different anatomical system: the skeletal system, the nervous system, the muscular system, the veins and arteries of the cardiovascular system, and the female reproductive

system via a pregnant woman delivering a breech baby.2 The colour illustration of the pregnant uterus is thought to be the first depiction of the gravid uterus. Each illustration was accompanied by detailed descriptions of various systems of the body, including the visual pathway and the development of the embryo.2 Despite some deficits in accuracy, the diagrams in Tashrih-i Badan-i Insan were so significant that they were still used in Persian and Arabic medical manuscripts for more than two generations after their original publication.

Ancient China

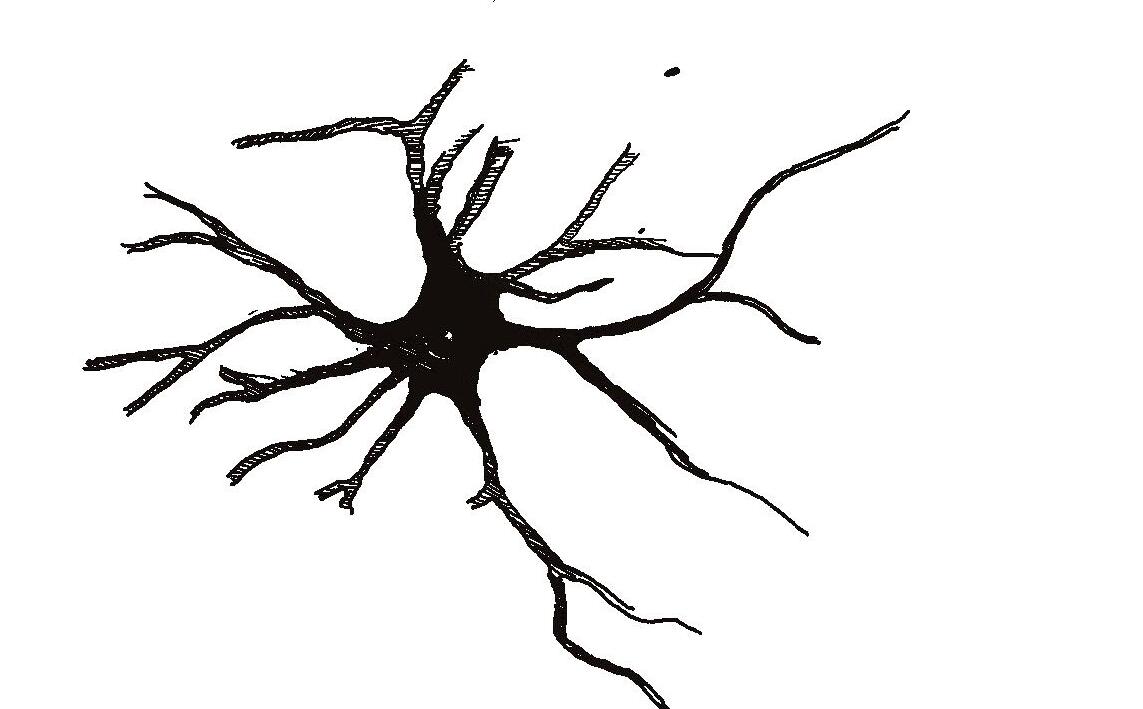

Early anatomical illustrations also developed throughout Ancient China. Artist Yan Luozi drew six human anatomical maps, titled Illustrations of Inner Body, that depicted various parts of the human body. Figure 2 displays a drawing made by Yan of the inner body as viewed from the back. This particular illustration correctly identified the existence of various internal organs, despite placing these organs in the wrong locations. Notably, Illustrations of Inner Body accurately depicted the location of the kidneys. Illustrations of Inner Body constitutes one of the earliest attempts at visualizing anatomy, ending the era of “talking without drawings” in China and permanently altering the way of communicating medical information.3

Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome

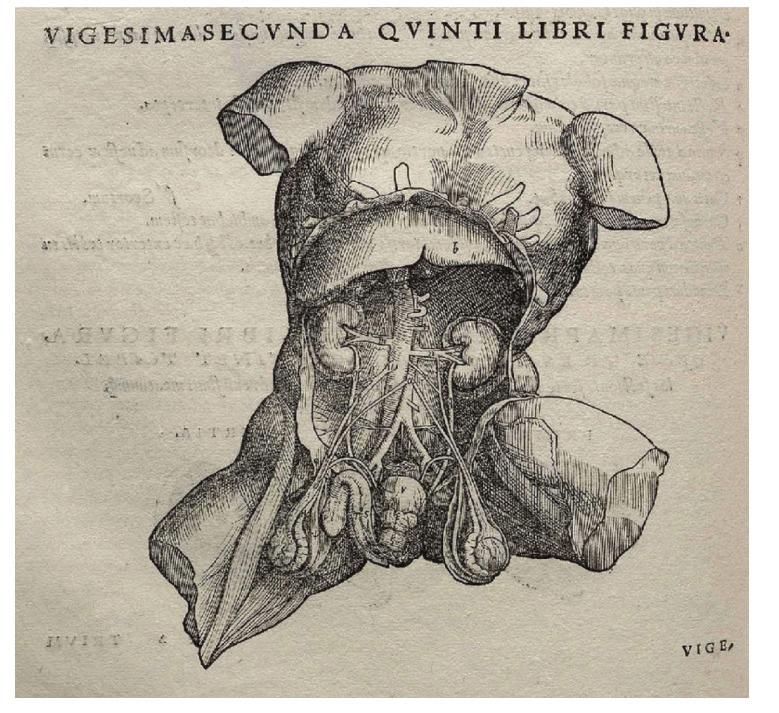

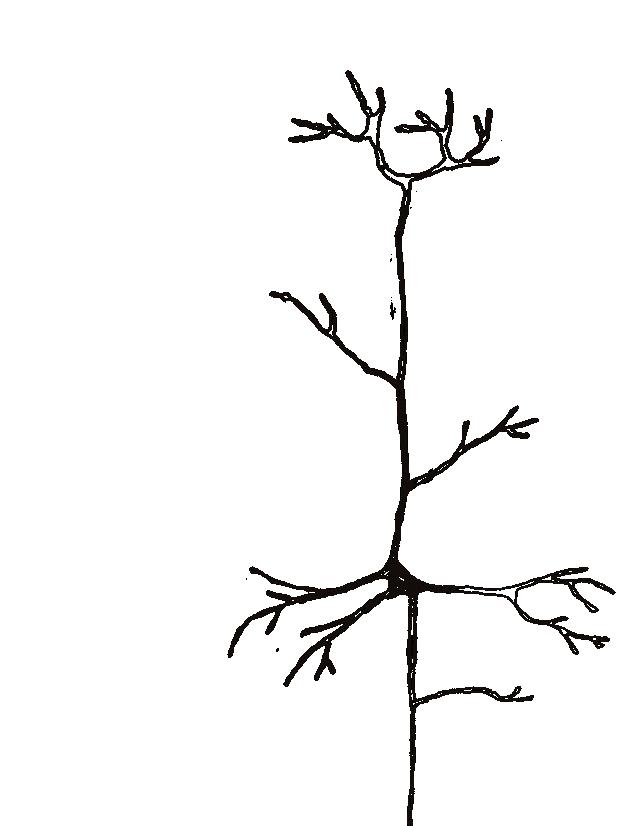

The Greeks and Romans, too, dominated much of early anatomy. Due to the strong influences of religion, the use of human cadavers was forbidden, and animal dissections became increasingly popular in advancing medical knowledge.1 During this time, theories in the field of anatomy were predominantly governed by physician Claudius Galenus, whose anatomical theories were misinformed. Anatomist Andreas Vesalius took note of these inaccuracies and challenged societal norms by incorporating the dissection of human cadavers into his understanding of anatomy, challenging centuries of medical dogma and encouraging a more empirical approach to medicine and science. These dissections and studies led to the creation of Vesalius’ work, De Humani Corporis Fabrica (Figure 3), published in 1543. His textbook contained

numerous detailed drawings completed by disciples of the great Italian Renaissance painter, Titian. Both a groundbreaking exploration into human anatomy and an astounding artistic work, this textbook revolutionized the understanding of anatomy with didactic text and accompanying imagery.4 The work was comprehensive, covering the full spectrum of human anatomy in unprecedented detail. This allowed for a more nuanced understanding of the human body, facilitating advancements in surgical techniques and medical treatments. The anatomical drawings in particular served as crucial pedagogical tools, aiding in the dissemination of knowledge throughout the medical and artistic communities. This was a significant advancement in medical education and meant that those who might not have direct access to human dissections could still learn about medicine. In addition, the direct observation and dissection methodologies introduced by Vesalius have persisted into modern medical education, emphasizing the importance of experiential learning.

As medical advancements were made, anatomical knowledge permeated artistic communities across the globe. Modern analyses of historical artworks have concluded that ancient artists actually possessed a firm grasp on human anatomy—a fact that is frequently overlooked due to the separation of these fields. The Fasting Buddha sculpture is one such example. Carved by Ancient Indian sculptors of the Gandhara region in the 2nd or 3rd century AD, the statue depicts the fasting, emaciated Buddha seated in a meditative pose (Figure 4).5 The statue was carved with generally correct muscle, neck, bone, and joint anatomy, demonstrating the expansive knowledge that the ancient artists possessed regarding the approximate shape, size, and position of various musculoskeletal features.5 In addition, the sculpture exhibits an understanding of the physiological changes that occur during starvation, evident by the Buddha’s skinny appearance.5 Certain errors were noted, including an extra number of ribs and a segmented sternum.5 However, this statue still demonstrates the undeniable connection between art and medicine—a connection marked by a shared pursuit of understanding the intricacies of the human form. This connection can also be considered symbiotic in nature; anatomists benefit from artistic visual depictions, and artists infuse scientific accuracy into their work based on anatomical knowledge. marked by a shared pursuit of understanding the intricacies of the human form. A symbiotic relationship of sorts; anatomists benefit from artistic visual depictions and artists infuse scientific accuracy into their work based on anatomical knowledge.

Renowned figures such as Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo also epitomize this unique relationship between science and art. Da Vinci’s detailed anatomical sketches, like the famed Vitruvian Man, reflect an astute understanding of anatomy that transcends artistic boundaries.6 Similarly, Michelangelo’s meticulous dissections, notably of human cadavers, informed his masterpieces like the Statue of David.7

The visual language developed in eras past became a crucial tool for conveying complex anatomical concepts and dismantling anatomical misconceptions, laying the foundations of art in medical anatomy into the 19th and 20th centuries. By the early 19th century, the use of human cadavers became commonplace.8 In fact, demand for human bodies grew so high that professors and surgeons in England turned to an unethical and nonconsensual practice. Anatomists often acquired cadavers from ‘body snatchers’, who illicitly removed corpses from burial sites.9 As the study of medical science and practice grew, anatomists began to favour direct engagement with human cadavers, and wax models of the Renaissance and Enlightenment were quickly disparaged.10

TThe uptick in the use of cadavers led anatomist Wilhelm Braune to adopt a new technique in anatomical study.11 In 1870, Braune received a cadaver of a young woman who had committed suicide during the last month of her pregnancy. Braune froze the body before slicing it into sections and traced the outlines of the tissues and cavities, creating a drawing that would be reproduced, debated, and replicated in several publications.12 Braune’s frozen sections simplified the three-dimensional intricacies of the human body onto a precise and detailed two-dimensional surface. Proponents of this practice hailed these frozen sections as revolutionary for understanding the body’s spatial relationships, but those traditionally opposed to artistic aid in anatomy argued that direct engagement with bodies through dissection was the only reliable way to acquire anatomical knowledge.12 Nonetheless, frozen sectioning spread across Europe and North America, marking a reconvergence of art and anatomy.13 Little information is available on the pregnant woman that Braune dissected, including her race, income, and the circumstances of her death. It is likely that she did not provide consent for her body to be used in such a manner. The authors wanted to highlight the inherent trauma ingrained into this practice and emphasize that despite the medical advancements made from this act, the immorality and breach of autonomy should not be overlooked.

The use of art in medical anatomy continued through the next century. Published books of anatomical illustrations became richer in detail and more vivid in color, revealing intricate details of skin, muscle, tendons, nerves, and bone. However, as seen above, the routes to this enhanced artistic production were often unethical. At the University of Vienna, Eduard Pernkopf received enhanced artistic production were often unethical. At the University of Vienna, Eduard Pernkopf received the bodies of executed prisoners for dissection, including political dissidents and members of historically marginalized populations. Using such unethically obtained information, Pernkopf published the Atlas of Topographical and Applied Human Anatomy. His atlas features over 800 illustrations, which despite having roots in violence and trauma, is still used today.14 It is essential to

Figure 3: An anatomical sketch by Andreas Vesalius from the De Humani Corporis Fabrica.1recognize that the continued influence of works like Pernkopf’s atlas, partnered with the lack of transparency regarding the dark history of the information featured in this work, underscores the lengthy road toward reconciliation that still remains in this field.

The discussion of art in anatomy is inextricably tied to a discussion of ethics, with considerations oscillating between the pursuit of medical advancement and the preservation of human sanctity and autonomy. Much of our past and present understanding of anatomy is tied to unethical dissections and graphic distributions of unconsenting people. From ancient Greece to the 20th century, vivisections were conducted on prisoners under the rationale of utilitarianism, which stripped individuals of their rights and autonomy and led to societal criticism and scrutiny. Grave robbing and burking for the purpose of dissection particularly plagued communities of low socioeconomic status, further demonstrating the horrific ethical transgressions in anatomical practice.15 In 1942, Germany passed legislation that denied families of executed Poles and Jews the right to claim the bodies.16 Countless more examples across history demonstrate a complete lack of regard for the respect of human life, particularly for historically marginalized populations. These tragedies should serve as a reminder that the advancement of anatomical understanding cannot justify the disregard of moral values. Ethical considerations must be paramount in all scientific and artistic endeavours.

Currently, it is widely accepted that prisoners have full rights over their bodies, and after death, their rights are then passed on to their next of kin. Furthermore, body donor programs are now the most common way of receiving cadavers, with a significant emphasis on respect, controlled graphic distribution, and informed consent. Activism and other progressive movements have also considerably reshaped the educational landscape, promoting awareness for inclusivity and equity.17 A prominent manifestation of these movements is the decolonization of education, which aims to address and rectify the historical biases and injustices found within anatomical curricula. This effort involves recognition of the injustices committed against minorities for scientific advancement and an overall reflection of how these events have shaped knowledge dissemination and the perpetuation of unjust social structures. More emphasis has been placed on diversifying anatomical information and moving away from the colonialist view of anatomy.18 In addition, the model of the white male is often presented as the universal standard of the human form, which is an untrue and incorrect perspective. This misrepresentation has led to an underrepresentation of certain bodies in anatomy, both in terms of cadavers used and educational imagery such as textbook diagrams and physical models.18 The omission of diverse bodies in education perpetuates biases and discrimination within the healthcare system, and educational and medical professionals must work to undo these unjust representations.

With the increasing emphasis on ethics in anatomy, modern educational systems have experimented with the visual mediums used during education. Interestingly, the visual medium used in a course has been proven to impact the engagement of students with the material presented. In a 2020 study conducted at The University of Thessaly, researchers found that the use of painted models in anatomy lectures improved interest

and understanding in undergraduate students as opposed to classical images. Further, many students hoped that this would become a permanent hallmark of the curriculum.19 These applications extend beyond undergraduate education. Medical students at Yale University are already required to participate in a program which involves learning through museum observations. The philosophy behind this method rests on visual literacy—the idea that meaning can be derived from the visual cues of an object. The program encourages students to first understand and see structures before applying their knowledge to a clinical setting. Following exposure to a piece, students are asked to observe and inventory the artistic details. They are then asked to analyze and derive meaning from their observations, prompting them to draw conclusions about the piece. According to the program director, this method of study allows the students to emulate the act of observing signs and symptoms, and providing an analytical diagnosis to a patient. A randomized controlled study was conducted to test the effectiveness of this intervention, and found that with this program, students identified visual cues required for a diagnosis with greater accuracy.20 Applications of art in medical education have found their way into residency programs as well. A systematic review conducted in 2022 showcased various art-based humanities approaches to teaching surgical residents, as well as the effects on their performance. The review concluded that anatomical drawing and modeling was found to enhance surgical learning. One example involved trainees creating three-dimensional models out of PlayDoh based on two-dimensional images, enhancing their ability to better conceptualize the three-dimensional conformation of various structures. An additional observation derived from this review indicates that art training helped enhance drawing and communication of their operations. This was exemplified in one study which found that with an increased focus of drawing, sculpting, and casting in classroom education, residents were better able to grasp the technical aspects of operations. Finally, drawing was actually found to be a particularly useful evaluation tool. Whether artistic competence was evaluated through sculpting exercises, the ability to draw accurate surgical markings, or the drawing of a therapeutic operative procedure, the ability to perform well in these tasks was associated with improved performance in the associated procedure.21

From historical compositions to educational methods, the art of anatomy has become a hallmark of human history within the last few centuries. The intersection of art and anatomy over the centuries has brought about significant ethical concerns. However, the evolution of ethical approaches to artistic anatomical practices reflects moral progress within society and a newfound responsibility to uphold the respect for and autonomy of every individual in pursuit of scientific knowledge. Nonetheless, art will continue to shape our perception of the human form and its complexities for generations to come.

THIS ARTICLE WAS ANONYMOUSLY REVIEWED BY AN ASSISTANT PROFESSOR OF PATHOLOGY & MOLECULAR MEDICINE AT MCMASTER UNIVERSITY.

doi: 10.35493/medu.45.12

AUTHORS:

PARTH ARORA 1, ADITYA MISRA 1, & ALINA PACE 2

1Honours Integrated Science (Biology Concentration), Class of 2026, McMaster University

2Bachelor of Arts & Science (Honours), Class of 2025, McMaster University

ARTIST:

HAMNA MALIK 3

3Bachelor of Engineering and Biomedical Engineering, Class of 2025, McMaster University

For the past two decades, Hamilton, Ontario—like many Canadian cities—has faced an escalating opioid crisis. In 2021, there were 162 opioid overdoses that resulted in death, 43% higher than the provincial average.1 In 2023, the Hamilton City Council declared opioid-related deaths an official emergency.2

The complex nature of opioid use disorder (OUD) in Hamilton necessitates a thorough investigation into its origins and a critical analysis of the current stratgies available to address this ongoing public health concern. Opioid addiction functions as both a clinical and social phenomenon, requiring contextualization

of the opioid epidemic within the history of Hamilton. Against this backdrop, the clinical aspects of opioid use are multifaceted. Hamilton emergency responders face the challenge of rising rates of opioid-related overdoses, 911 calls, and managing opioid dependence in conjunction with other comorbidities. As a result, a comprehensive understanding of the clinical condition is vital for effective implementation of prevention, intervention, and treatment strategies. This article will explore the specific patterns of opioid use in Hamilton, at-risk populations, and health outcomes.

To respond to the epidemic, the municipal government and local nonprofits have designed a variety of interventions. Analysing these response strategies implemented in Hamilton has revealed their response strategies implemented in Hamilton has revealed their effectiveness on a local scale and areas for improvement. Whether through harm reduction initiatives, drug-replacement therapies, or community-based interventions, it is critical that policies are tailored to the unique needs of Hamilton’s population. There are funding gaps that create barriers for users to receive treatment, and exacerbate challenges created by recent increases in polysubstance use, specifically when preventing overdoses.

By elucidating the specific challenges faced by the community, this

article aims to contribute to the ongoing dialogue surrounding the opioid epidemic, providing a foundation for targeted interventions to address this pressing public health crisis in Hamilton.

According to the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, OUD is a clinically diagnosed condition involving a harmful pattern of opioid use leading to significant impairment or distress.3 OUDs are categorised as mild, moderate, or severe based on criteria such as tolerance, withdrawal symptoms, and impact on daily life. The repercussions of OUD on an individual’s health are two-fold, are two-fold, affecting both mental and physical well-being. Individuals with OUD often struggle with mental health disorders, such as depression and anxiety, and face physical health challenges, including respiratory problems and a higher susceptibility to infectious diseases.4,5 These complexities underline the critical need for holistic treatment strategies that concurrently address the physical and psychological facets of OUD.6 The broader term ‘opioid addiction’ is often defined as a chronic and compulsive disorder that involves the uncontrollable use of opioids despite harmful consequences. Understanding OUD and differentiating it from the more stigmatised and historically used term ‘opioid addiction’ is crucial for encouraging open dialogue and promoting effective treatment.1 Stigma, in the context of OUD, often stems from misconceptions about the disorder, which can lead to discrimination and social exclusion.1 However, the term ‘addiction’ has evolved to bear social stigma and thus, replacing it with OUD supports the notion that this condition is a health issue rather than a personal shortcoming.

In Hamilton, managing OUD presents challenges unique to the city. Hamilton is grappling with the need to balance evolving national and provincial chronic pain opioid prescribing guidelines with the increasing demand for chronic pain treatment and surging overdose deaths. Hamilton’s approach to OUD management needs to contend with the intertwined issues of homelessness, mental health, and substance abuse, highlighting the necessity for a comprehensive approach to controlling OUD.

Within the past five years, Hamilton has seen a large increase in opioid-related incidents and deaths. In 2023, Hamilton Paramedic Services responded to 964 incidents related to suspected opioid overdoses, compared to 814 incidents in 2022, representing a 16% increase in a single year. number of opioid-related deaths has also been increasing annually from 52 confirmed deaths in 2016 to 106 in 2023. In January 2024 alone, there have been 36 incidents of suspected opioid overdoses in the city of Hamilton.

The impacts of the opioid epidemic in Hamilton are profound. Geographically, the opioid crisis is widespread across Hamilton, with overdoses reported in every ward. However, areas with higher rates of unemployment and lower median home values have higher rates of opioid prescriptions, opioid-related hospital visits, and opioid overdose deaths.

The public health impacts are equally important to consider as the socioeconomic impacts. The rise in opioid use has led

to an increase in emergency room visits, neonatal abstinence syndrome, and OUD treatment admissions.13 Demographically, more than 65% of opioid deaths in Hamilton are among men aged 25 to 65.11 Older adults also present a significant concern, with approximately 15% of Hamilton citizens over the age of 50 being exposed to opioids.14 Overall, the opioid crisis has strained public health services, with Hamilton Paramedic Services and local hospitals responding to an increasing number of opioid-related incidents.10

The types of opioids used clinically in Hamilton are diverse. Codeine and tramadol are often the first-line opioids for mild to moderate chronic non-cancer-related pain.15 If these prove ineffective, stronger opioids like oxycodone, hydromorphone, and morphine are prescribed. For the treatment of OUD, methadone or buprenorphine-naloxone are commonly used.16

The opioid crisis in Hamilton has also led to a rise in the number of children and young adults exposed to opioids. The City of Hamilton found that childhood risk markers predicting opioid use include male sex, tobacco use, depression, conduct disorder, cannabis use, having peers exhibiting social deviance, and elevated systemic inflammation. These factors contribute to the risk through a mix of social, psychological, and biological vulnerabilities, such as societal norms, dependence pathways in the brain, mental health issues, impulsivity, peer influence, familial instability, and potential links between inflammation and dependence vulnerability.17

In June of 2023, the city’s Public Health Board implemented the Hamilton Drug Plan, an 18-month action plan focused on reducing opioid harm and deaths and increasing access The specific initiatives included scaling up supervised consumption sites, developing safer-use policies, increasing availability of drugchecking services, and expanding support for families and youth prevention programs. This comprehensive plan reflects a commitment to both immediate and sustainable long-term solutions, emphasising collaboration, evidence-informed recommendations, and the inclusion of individuals with lived experience in the decision-making process.7

However, gaps exist in Hamilton’s approach. The city’s strategy was put on pause during the pandemic to focus on COVID19-related relief, leading to an increase in deaths linked to This suggests a need for a more resilient strategy that can adapt to external shocks like a pandemic. Additionally, most drug-related deaths in Hamilton occur in private residences, indicating a need for more community-based

interventions.7 Private residences may lack immediate access to emergency services and overdose prevention tools like naloxone.19 Community-based interventions could include educational outreach programs, increased resources, direct in-home support, as well as training for family and friends on how to respond to overdoses, which could be crucial in preventing fatalities.7

Comparatively, the opioid crisis is also a global issue, with different regions executing a variety of strategies which Hamilton can also implement. For instance, in the United States, strategies primarily involve targeted naloxone distribution and medication-assisted treatment.6 In Europe, regulatory restrictions, drug policy measures, and large-scale implementation of opioid dependence treatments have been used.18

Moving forward, the City of Hamilton could adopt strategies proven successful in other countries. For instance, the U.S. emphasises specialised care, acknowledging different stages of OUD that specific citizens are facing, and promoting collaboration among community entities.6 Europe’s approach of better accessibility and full reimbursement of OUD treatments could also be beneficial to reduce the financial burden of treatment and incentivize more citizens to seek help.18 By incorporating elements from both the American and European strategies, Hamilton can develop a more robust response to the opioid crisis that addresses various aspects of prevention, treatment, and recovery support.

In addition to the challenges mentioned, the rising use of other drugs along with opioids has created new issues. A 2023 report by Public Health Ontario notes that “opioids and stimulants in combination with each other made up the highest proportion of toxicity deaths during the COVID-19 pandemic (43.1%).”20 They also reported that deaths in Ontario where the primary cause was alcohol, stimulants, or benzodiazepine use, over 80% also involved opioids. In many of these cases, people may be unaware that their drug supply is impure and could contain additional opioids or stimulants in their drug supply. Since polysubstance use is associated with higher fatality rates, this further suggests that Hamilton needs better substance management programs for all substances. Addressing polysubstance use may help reduce the number of deaths due to opioid-related and overall overdoses.

Opioid-related morbidity and mortality data has been collected in Ontario since 2004, and the City of Hamilton’s opioid-related death rate has been consistently higher than the provincial average.10 To respond to the recent surge in opioidrelated deaths, the City has implemented various communitybased initiatives through the Hamilton Drug Plan, which will tackle the emergency based on a comprehensive, evidencebased approach. The recent shift in the substance abuse landscape towards polysubstance abuse is poised to become a problem if the city does not address these concerns. Although there are still gaps in the City’s response, only time will tell the effectiveness of ongoing initiatives. Nevertheless, the pressing need to reshape the narrative of stigma associated with opioid addiction and OUD still remains. It will take the collective efforts of the community, healthcare workers, and policymakers for a sustained response to the opioid emergency in Hamilton to be effective and successful in preventing deaths.

REVIEWED BY: DR. DOROTHY BAKKER (MD, MA, CCFP, FCFP)

Dr. Bakker graduated from McMaster University Michael G. DeGroote School of Medicine and completed her family medicine residency at the North Hamilton Community Health Centre. She has practised as a rural family physician in Port Elgin, a student health physician at the University of Guelph, and an immigration panel physician. She completed a Master of Arts in leadership studies at the University of Guelph, and received a Certificate in Travel Health from the International Society of Travel Medicine.

EDITED BY: DOMINIC GANGEMI & RIA PATEL

1. Cheetham A, Picco L, Barnett A, Lubman DI, Nielsen S. The impact of stigma on people with opioid use disorder, opioid treatment, and policy. Subst Abuse Rehabil . 2022;13:1–12. Available from: doi:10.2147?SAR.S304566.

2. van den Brink W, Pierce M, van Amsterdam J. What lessons from Europe’s experience could be applied in the United States in response to the opioid addiction and overdose crisis? Addict Abingdon Engl . 2022;117(5):1197–8. Available from: doi:10.1111/add.15839.

3. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders [Internet]. DSM Library. [cited 2024 Jan 31]. Available from: https://dsm.psychiatryonline.org/doi/book/10.1176/appi. books.9780890425596.

4. Santo T, Campbell G, Gisev N, Martino-Burke D, Wilson J, Colledge-Frisby S, et al. Prevalence of mental disorders among people with opioid use disorder: A systematic review and metaanalysis. Drug Alcohol Depend . 2022;238:109551.

5. Dydyk AM, Jain NK, Gupta M. Opioid Use Disorder. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 [cited 2024 Jan 31]. Available from: http://www.ncbi. nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK553166/.

7. News · CN· C. Hamilton public health board moves forward with new opioid action plan | CBC News [Internet]. CBC. 2023. Available from: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/hamilton/ opioid-crisis-action-plan-1.6873396.

8. News · SB· C. Hamilton set to declare state of emergency for homelessness, mental health and opioid addiction | CBC News [Internet]. CBC. 2023. Available from:https://www.cbc. ca/news/canada/hamilton/hamilton-state-of-emergency-homelessness-1.6804478.

9. Klimas J, Hamilton MA, Carney G, Cooper IR, Croteau NS, Dong H, et al. Characteristics and incidence of opioid analgesic initiations to opioid naïve patients in a Canadian primary care setting. Can J Addict . 2022 Mar;13(1):43. Available from: doi: 10.14288/1.0407128.

10. Hamilton Opioid Information System | City of Hamilton [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jan 30]. Available from: https://www.hamilton.ca/people-programs/public-health/alcohol-drugsgambling/hamilton-opioid-information-system.

11. Hamilton has seen an “exponential rise” in opioid deaths. Is it a “state of emergency”? [Internet]. CBC. 2023. Available from: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/hamilton/opioidemergency-1.6713522.

12. Seltzer N. The economic underpinnings of the drug epidemic. Popul Health. 2020;12:100679. Available from: doi:10.1016/j.ssmph.2020.100679.

13. National Academies of Sciences E, Division H and M, Policy B on HS, Abuse C on PM and RS to APO, Phillips JK, Ford MA, et al. Trends tin Opioid Use, Harms, and Treatment. In: Pain Management and the Opioid Epidemic: Balancing Societal and Individual Benefits and Risks of Prescription Opioid Use [Internet]. National Academies Press (US); 2017. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK458661/.

14. Buckley N. The prescription opioid epidemic: a call to action for our profession. Can J Anesth. 2016;63(1):8–11.

15. Kahan M, Mailis-Gagnon A, Wilson L, Srivastava A. Canadian guideline for safe and effective use of opioids for chronic noncancer pain. Can Fam Physician . 2011;57(11):1257–66.

16. Srivastava A, Kahan M, Nader M. Primary care management of opioid use disorders: Abstinence, methadone, or buprenorphine-naloxone? Can Fam Physician . 2017;63(3):200–

5. Available from: doi:

17. Shanahan L, Hill SN, Bechtiger L, Steinhoff A, Godwin J, Gaydosh LM, et al. Prevalence and childhood precursors of opioid use in the early decades of life. JAMA Pediatr 2021;175(3):276–85. Available from:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.5205.

18. News · BH· C. Hamilton’s opioid deaths during pandemic among worst in Ontario, report says | CBC News [Internet]. CBC. 2021 [cited 2024 Jan 30]. Available from: https://www.cbc. ca/news/canada/hamilton/hamilton-opioids-covid-19-1.5918251

19. Partnerships Between Public Health and Public Safety | Drug Overdose | CDC Injury Center [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2024 Jan 30]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/ strategies/public-safety.html.

20. Gomes T, Leece P, Iacono A, Yang J, Kolla G, Cheng C, Ledlie S, Bouck Z, Boyd R, Bozinoff N, Campbell, T, Doucette T, Franklyn M, Newcombe P, Pinkerton S, Schneider E, Shearer D, Singh S, Smoke A, Wu F. Characteristics of Substance-Related Toxicity Deaths in Ontario Stimulant, Opioid, Benzodiazepine, and Alcohol-Related Deaths. 2023; Available from: https://odprn.ca/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Substance-Toxicity-Report-Final.pdf

6. Evidence-Based Strategies for Preventing Opioid Overdose: What’s Working in the United States | Drug Overdose | CDC Injury Center [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2024 Jan 30]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/featured-topics/evidence-based-strategies.html.

doi: 10.35493/medu.45.16

AUTHORS:

FLORENCE DENG 1 & RUHANI KHATTRA 1

ARTIST:

KATIE LIN 1

1Bachelor of Health Sciences (Honours), Class of 2026, McMaster University

Crohn’s disease (CD) is a chronic inflammatory disease of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract that falls under the umbrella of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).1 A 2023 impact report estimated that approximately 4.1 in 1000 Canadians live with CD.2 CD is characterized by discontinuous and patchy ‘skip lesions’ and transmural inflammation. The former may impact any part of the GI tract from the mouth to the anus, while the latter extends across the entire thickness of the bowel wall.3 Symptoms are variable and may include diarrhea, abdominal pain, and weight loss, among other potential complications.3 Patients with CD experience a poorer quality of life due to unpredictable bouts of remission, relapse, and no known cure.1

Although the exact pathogenesis of CD is unknown, studies have shown that dysregulated immune responses, genetic factors, gut microbiota, and other environmental factors can modulate disease risk.3 Currently, there is ample evidence to postulate a link between the gut microbiome and IBD. Clinical and animal trials have suggested that gut bacteria trigger and perpetuate colitis and IBD.4 In one study, researchers deduced that individuals with GI infections from Salmonella or Campylobacter have an increased risk of developing IBD within the first year of illness.3 Early antibiotic exposure and gut microbiome disruption, most prominently from ages 0 to 5, also correlate with an increased risk of CD. Among other environmental factors, emerging evidence suggests that diet may be a potential risk factor for CD. For instance, Narula et al. discovered that a high intake of ultra-processed food was positively associated with a higher risk of IBD.5 Although genetic risk factors are still being elucidated, over 200 genes are found to be associated with IBD development. For instance, homozygotic mutations at the NOD2 locus of chromosome 16 may result in fibrostenotic–or narrowing–disease of the GI tract and altered interactions between ileal microbiota and mucosal immunity; affected individuals are 20 to 40 times more likely to develop CD.3,6,7

CD diagnoses are made based on clinical evaluation, diagnostic imaging, and laboratory tests. Generally, CD is suspected when a patient presents with GI symptoms such as inflammation or obstruction, abdominal pain and bloating, persistent diarrhea, perianal fistulas or abscesses, and malnutrition and malabsorption of nutrients, particularly vitamin D or B12.3,8 Using a combination of computed tomography and magnetic resonance scans as well as upper and lower endoscopy imaging, physicians can recognize the internal markers of CD: bowel wall thickening, narrowing of the intestines (stricturing), ulceration, and a “cobblestone” pattern of inflammation on the intestinal lumen.8,9 While imaging is typically required to confirm CD, blood and stool laboratory testing can also be helpful in diagnosis, monitoring inflammation, and ruling out other digestive disorders (e.g., GI infection, Celiac disease, malignancy, irritable bowel syndrome, etc.).8,9

For research and treatment purposes, CD is categorized into three phenotypes: inflammatory, stricturing, or fistulizing CD.3,8 Inflammatory CD may evolve into either of the two latter phenotypes of CD and is characterized by transmural inflammation of the GI tract. This begins with inflammation and small focal ulceration, which may develop into deep longitudinal or transverse GI ulcers.8 These mucosal lesions produce edema, creating a characteristic “cobblestoned” appearance in the bowel of individuals with CD.8

In the stricturing phenotype of CD, excessive inflammation may result in hypertrophy of the muscular mucosa of the intestine, intestinal fibrosis, and stricture formation.8 Strictures refer to areas of stenosis and luminal narrowing in the GI tract, which could cause a bowel obstruction. These fibrostenotic changes are irreversible, aside from surgical correction.3

Prolonged transmural inflammation may also produce a sinus/ fistulous tract, which is characteristic of the fistulizing phenotype of CD. Fistulas are abnormal tunnels that can form between the bowel and adjacent organs.3 CD fistulas result from an epithelial defect related to chronic inflammation—epithelial-tomesenchymal transition (EMT). In EMT, intestinal epithelial cells (IECs) lose their epithelial phenotype to undergo mesenchymal differentiation. The epithelial phenotype is characterized by strong intercellular junctions and cell polarity, whereas the mesenchymal phenotype results in a fibroblast-like morphology, which involves reduced intracellular contact.10 Due to this, IECs gradually migrate and tunnel into deeper layers of the gut wall, causing tissue damage and fistulous tract formation.10 If this tract does not reach an adjacent organ, an abscess—a painful collection of pus, typically caused by infection—is likely to develop. Fistulas and abscesses can induce systemic pain, fever, and other infections related to their location on the GI tract.3,8

While CD is not fatal, it may increase the risk of life-threatening complications, such as sepsis, colorectal cancer, malnutrition, and peritonitis.11 Fistulas may also tunnel to the skin’s outer surface, forming an enterocutaneous fistula.11 Moreover, chronic inflammation, fistulas, abscesses, and strictures can weaken points of the intestinal wall, tearing or perforating the colon to allow for subsequent leakage of GI substances into the abdomen.11

TREATMENTS

Currently, there are no available curative treatments for CD or preventative therapies to correct a potential underlying genetic factor for disease onset.12 The course of management is often individualized depending on a range of factors, including age, comorbidities, symptoms, severity of inflammation, and location of disease.13 CD management involves two primary goals: treating inflammation and complications, and minimizing symptoms.13 Treatments induce mucosal healing, resulting in sustained clinical and endoscopic remission.12 Patients with mucosal healing consistently demonstrate improved outcomes such as lower relapse rates and improved quality of life.14

In the intestine, macrophages, neutrophils, and T cells promote pro-inflammatory mediators like tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α. Intestinal inflammation in CD dominantly presents with a T-helper 1 and 17 cell-mediated response.1 At present, anti-TNF therapy is an established biologic that may be effective on some CD patients.14 Human TNF is a family of proteins and receptors involved in immune regulation.15 TNF is strongly associated with CD as its biological effects include increased inflammatory cytokine production and inhibition of inflammatory cell apoptosis.15 Therapeutic uses of antiTNF antibodies result in anti-inflammatory effects, including TNF neutralization, depletion of TNF overexpression, and cytokine suppression via reverse signalling processes.15 These effects allow anti-TNF therapy to be effective in inducing and maintaining remission in moderate to severe CD.3 Anti-TNF therapy is often prescribed alongside immunosuppressants (e.g., thiopurine, methotrexate) to decrease immunogenicity rates and increase anti-TNF drug concentration.3,14 Other potential treatments include enteral nutrition and corticosteroids.10 Combination therapies play a substantial role in symptom improvement, mucosal healing, and remission maintenance, with complete remission being the ultimate goal.3,12

Novelly, the Genetic, Environmental, Microbial (GEM) project, an international research study dedicated to determining possible causes for CD, has recently discovered that the gut bacteria composition of individuals who develop CD differs from healthy individuals up to five years before disease development.16 By establishing a model to evaluate the microbiome risk score (MRS), researchers could classify individuals who later developed CD or not, providing insight into microbial determinants of CD pathogenesis. Notably, Ruminococcus torques and Blautia were positively correlated with the MRS, whereas Faecalibacterium and Lachnospira, which produce anti-inflammatory protective metabolites, were negatively correlated with the MRS.17

The role of nutrition, which is suggested to be a significant environmental factor for CD, is an ongoing area of investigation.18

A recent 2024 prospective observational study comparing nutrient intake and blood values of CD patients undergoing anti-TNF therapy suggests potential new nutritional biomarkers capable of predicting therapeutic responses.18 Blood analysis conducted before anti-TNF therapy showed that patients who did not respond to treatment also had significantly decreased levels of taurine and iron.18 Additionally, there was an observable trend of decreased vitamin B12 levels in those who could not achieve

clinical remission upon biological therapy.18 Within the realm of CD management, the lack of therapeutic response is a common problem, calling for optimized treatment and predictions for patients. Rizzello et al. suggests iron and taurine blood levels may be connected to CD patients’ therapeutic outcomes, and has the potential to be used in association with validated biomarkers to assist in therapeutic decision-making.18

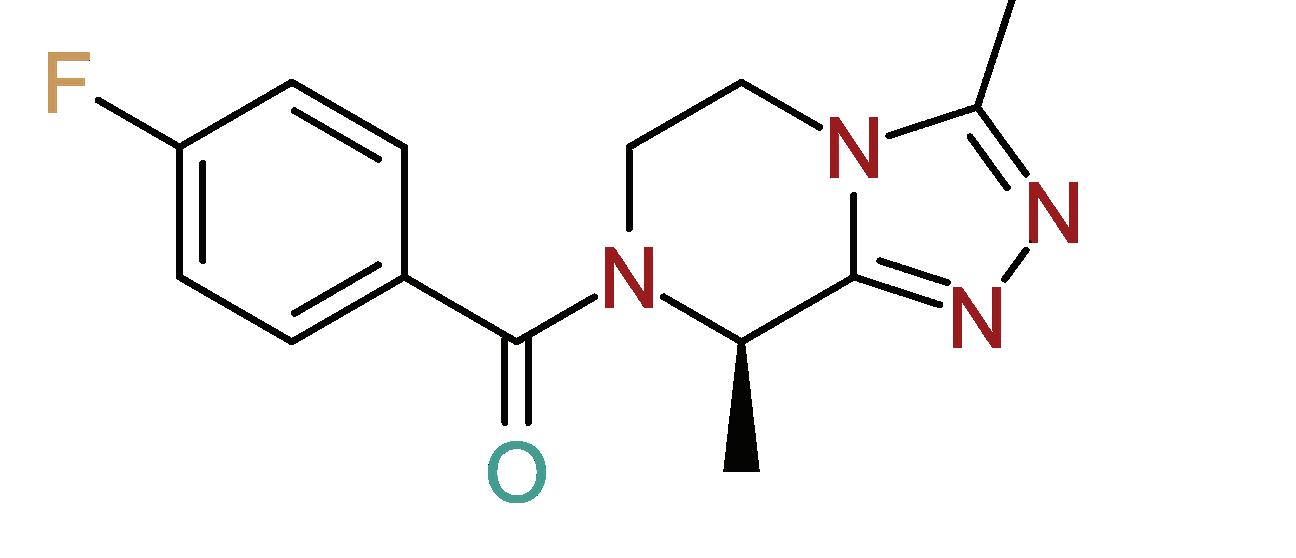

Colonic lesions in CD also have characteristically high levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, like interferon-γ, interleukin (IL)-2, IL-12, and IL-18.1 A breakthrough study in May 2023 introduced the first oral medication, upadacitinib, successful in treating moderate-to-severe CD.19 Upadacitinib is a novel Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor and a promising therapeutic candidate for treating inflammatory disorders, including CD.20 The mechanistic ability to modulate the JAK pathway, which is key to CD pathogenesis, demonstrates potential in achieving remission and improving quality of life, especially for patients with suboptimal responses to existing treatments.20 JAK inhibition results in decreased production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, significantly diminishing immune events inciting and perpetuating the chronic inflammation characteristic of CD.20 A Phase 3 trial conducted for upadacitinib has demonstrated that patients with moderate-to-severe CD responded favourably compared to a placebo, garnering US Food and Drug Administration approval.21 However, safety profiles show consistent reports of adverse events following upadacitinib use, urging careful monitoring of treatment continuation.20 Further investigation has persisted into the efficacy of dual-targeted therapy (DTT), in which the amalgamation of different inflammatory cascades can lead to a synergistic therapeutic effect in select CD cases.21 One study explores the concurrent use of upadacitinib and ustekinumad, a monoclonal antibody to the p40 subunit of ILs. Ultimately, combining the two drugs was effective and well tolerated for patients with medicallywresistant CD.21 However, the long-term safety profile of DTT remains scarce and limited, given the novelty of upadacintinib.21

Though a permanent cure for CD has not been developed, exciting strides in prognosis and treatment set the stage for continued progress and evolution.

REVIEWED BY: DR. MOHAMED ELTORKI (MSc, FRCPC, MBChB) & DR. WALIUL KHAN (MBBS, PhD, FRCPath, CAGF, MBChB)

Dr. Mohamed Eltorki is an Associate Clinical Professor in McMaster University’s Department of Pediatrics, with research initiatives in gastroenterology, pediatrics, and emergency medicine research ethics. He is also the Trauma Team Leader at McMaster Children’s Hospital and part of the Pediatric Emergency Medicine Simulation Oversight Committee.

Dr. Waliul Khan is a professor and principal investigator at the Fancombe Family Digestive Health Research Institute of McMaster University. He is also the Academic Division Lead of Clinical Pathology of the Department of Pathology & Molecular Medicine at McMaster University and works as a Clinical Scientist/ Consultant Immunologist at Hamilton Health Sciences.

References can be found on our website: www.themeducator.org

The Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD) hypothesis proposes a connection between early life exposures—encompassing the prenatal conditions of sperm, in-utero conditions and thereafter—and long-term metabolic disorders and diseases like diabetes, cancer and neurodevelopmental disorders. This hypothesis suggests that environmental conditions can modulate epigenetic processes, driving DNA changes in response to environment and impacting fetal behaviour.1 For example, epigenetic mechanisms such as histone modifications alter genomic DNA during the embryogenesis stage.2 These alterations in early developmental stages can induce and maintain altered gene expression throughout life, consequently affecting adult pathology.3,4 While a plethora of factors— such as paternal exposures, postnatal environments, and sociocultural factors—also contribute to the DOHaD theory, emphasis is placed on maternal exposures in utero.5 As epigenetics garners media attention, Richardson et al. warn about the impacts of oversimplification and miscommunication of DOHaD, contributing to narratives that unjustly blame mothers for their children’s future disease susceptibility.6 This paper will examine the causes, implications, and strategies to address mother-blame narratives pervading DOHaD discourse through a feminist lens, focusing on the experiences of pregnant mothers.

Media language evidenced in news headlines, such as “Mother’s diet during pregnancy alters baby’s DNA” and “Grandma’s Experiences Leave a Mark on Your Genes,” imply that maternal choices or experiences affect the genetic material of the developing fetus without acknowledging the various environmental, social, and paternal determinants that also influence offspring health.6 Consequently, the sensationalization of scientific findings as

definitive conclusions results in anxiety for pregnant women. For instance, Beatriz, a participant in a focus group conducted by Norrmén-Smith et al., shared that the media “take[s] a scientific paper, one piece of information, [and] make[s] it a big headline, and then they talk about it like it was the end of your life. It’s like, they take it out of context and it creates so much anxiety.”7 Reductionist and exaggerated headlines fuel harmful societal expectations, which cause anxiety, blame, and stigma for mothers.

Women with children who develop Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD), a spectrum of disorders caused by in utero alcohol consumption, are often privy to stigma as a result of distorted health narratives. Shanker et al. interviewed an FASD policy worker who illustrated the stigma experienced by FASD mothers: “The mom is solely responsible to produce that FASD child…Responsibility is part of the bigger picture, but it is mom that has the relationship there.”8 As such, societal stigma often places full responsibility on mothers for choices made during pregnancy, depicting mothers as neglectful caregivers or addicts who are in denial.9 While mothers are often burdened with their children’s health outcomes, it is imperative to consider the role of fathers in contributing to FASD risk. Although paternal alcohol use does not directly cause FASD, “Fathers who drink may contribute to this condition through their influence on women’s alcohol use in pregnancy” and “can negatively impact intelligence and cognitive ability in their children.”10 Stigma experienced by FASD mothers underscores a societal tendency to assign blame solely to them, reinforcing traditional gender roles and overlooking the shared responsibility of both parents in contributing to the child’s well-being. These harmful narratives can commonly lead to lower self-esteem and persistent guilt in women. In particular, affected mothers are more likely to attribute their alcohol consumption during pregnancy to individual responsibility, rather than consider the societal and structural factors that may influence their behaviors: “I am the responsible one...I am the one who was pregnant. I feel horrible about that,” stated a participant in a study conducted by Zabotka et al.9,11 Hence, dismantling this public stigmatization not only requires a shift in individual perspectives, but also prompts a collective societal acknowledgement on the lack of support infrastructure in place for pregnant women.

Lappé et al. argues that biocentric communications of epigenetics and DOHaD shift significant responsibility of birth outcomes to mothers, perpetuating historical narratives that disproportionately affect racialized communities (e.g. Black, Brown, and Indigenous populations).12 For example, studies suggest that gestational diabetes may be related to up to 30% of type two diabetes cases amongst Oji-Cree mothers, compared to 6% of cases amongst other populations in Saskatchewan.13 Coupled with the lack of comprehensive nutritional counseling programs, these potential health risks contribute to anxiety and guilt amongst Indigenous women.14,15 Related discourse glosses over the historical consequences of colonization on healthcare systems, including food insecurity, loss of traditional hunting land, and practices that modulate higher risks for gestational diabetes.16 Consequently, the effects of social determinants of health and racial inequities in maternal healthcare become overlooked in epigenetics discourse. For example, Scott et al. discussed the detrimental implications of medical professionals abdicating responsibility for poor birth outcomes of Black women who come to pregnancy “older, sicker, and fatter.”17 As highlighted by clinician-scientist Monica McLemore, “focusing on a mother’s individual characteristics or behavior avoids the uncomfortable truth that health care systems, namely hospitals and clinics and the people who work in them, contribute to these poor [birth] outcomes.”18

BIOSOCIAL DISCOURSE

To mitigate mother-blame narratives in DOHaD, it is critical to bridge gaps in knowledge translation between biological scientists, social scientists, clinicians, public health professionals, and the public. Molinaro et al. suggests that public health translation of DOHaD should be made more readily available to the public, in addition to promoting awareness about social determinants of health

which acknowledge the historical and social barriers that restrict individual choices.19 Similarly, Harris et al. suggest a biosocial approach that considers “dynamic, bidirectional interactions between biological phenomena and social contexts, which contribute to the lifelong development of humans to shift away from viewing healthcare as a strictly empirical and scientific field.20 Moreover, it is suggested that the roles of community and society are emphasized in epigenetics discourse to acknowledge the upstream effects of sociocultural factors (e.g. economic instability, food insecurity, environmental exposures to toxins, and marginalization) on the biological processes that contribute to and occur during fertilization and pregnancy.20 Thus, biosocial discourse promotes the collective efforts to support and improve the wellbeing of women.

Rather than using language that implies maternal responsibility, language describing the circumstances behind the mother’s decision-making should be applied. For instance, conventional communication instincts such as, “we need to focus on mothers’ diets during pregnancy” or “if women experience too much stress” subtly reinforce a restricted viewpoint centered around the mother.21 To foster a more comprehensive understanding, Winett et. al suggest that effective communication should employ frameworks transcending individual-centric narratives, focusing instead on broader concepts framed as “the circumstances in which women are pregnant and in which children develop” or “the social and economic pressures facing that community.”21 Such framing facilitates an expanded cognitive map, fostering consideration of the intricate network of influences contributing to the issue, which avoids invoking perspectives that impede inclusive thinking.

The historical focus on the intrauterine factors and maternal responsibilities in epigenetics and DOHaD discourse results in mother-blame narratives that perpetuate stigmatization, fear, and guilt in mothers. These narratives enable potential abdication of responsibilities to deliver quality healthcare and public health initiatives. To dispel these narratives, DOHaD discourse should be made more accessible to the public and approached from a biosocial lens that acknowledges the multifaceted relationship between maternal and paternal biological epigenetic processes and sociocultural factors contributing to disease risks. Rather than placing blame on mothers, the insights provided by DOHaD

research can be leveraged to develop educational public health campaigns and policies that promote healthy living, public nutrition, and mental wellness initiatives to protect from disease risk.

REVIEWED BY: DR. MAHMOOD AKHTAR (PhD)

Dr. Mahmood Akhtar is a professor and facilitator in the faculty of Health Sciences at McMaster University. He received his PhD in the field of molecular microbiology, and has completed 2 postdoctoral fellowships. His research has focused on mitochondrial function and metabolic disease.

EDITED BY: OLIVIA KIM, ZAHRA TAUSEEF, & ANGELA HONG

1. Lacagnina S. The Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD). Am J Lifestyle Med. 2019;14(1):47-50. Available from: doi:10.1177/1559827619879694.

2. Sharp GC, Lawlor DA, Richardson SS. It’s the mother!: How assumptions about the causal primacy of maternal effects influence research on the developmental origins of health and disease. Soc Sci Med. 2018;213:2t0-7. Available from: doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.07.035.

3. Richardson SS, Daniels CR, Gillman MW, Golden J, Kukla R, Kuzawa C, et al. Society: Don’t blame the mothers. Nature. 2014;512:131-2. Available from: doi:10.1038/512131a.

4. Norrmén-Smith IO, Gómez-Carrillo A, Choudhury S. “Mombrain and sticky DNA”: The impacts of neurobiological and epigenetic framings of motherhood on women’s subjectivities. Front Sociol. 2021;6:653160. Available from: doi:10.3389/fsoc.2021.653160.

5. Shanker I. Risky bodies: Allocation of risk and responsibility within fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD) prevention campaigns.

CJDS. 2016;5(2):152-77. Available from: doi:10.15353/cjds.v5i2.276.

6. Roozen S, Stutterheim SE, Bos AER, Kok G, Curfs LMG. Understanding the social stigma of fetal alcohol spectrum disorder: From theory to interventions. Found Sci. 2022; 27(1):753-18. Available from: doi:10.1007/s10699-020-09676-y.

7. Gearing RE, McNeill T, Lozier FA. J FAS Int. 2005;3(e14):1-11.

8. Zabotka J, Bradley C. “How could I have done this?” Thoughts of mothers of children with fetal alcohol syndrome. J Soc Work Pract Addict 2017;17(3):258-316. Available from: doi:10.1080/1533256X.2016.1243123.

9. Lappé, M, Fahey, FF, & Hein, RJ. Epigenomic stories: Evidence of harm and the social justicve promises and perils of environmental epigenetics. ST&HV. 2022. Available from: doi:10.1177/01622439221137028.

10. Osgood ND, Dyck RF, Grassmann WK. The inter- and intragenerational impact of gestational diabetes on the epidemic of type 2 diabetes. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(1):173-9. Available from: doi:10.2105/AJPH.2009.186890.

11. Neufeld HT. Food perceptions and concerns of aboriginal women coping with gestational diabetes in Winnipeg, Manitoba. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2011;43(6):482-91. Available from: doi:10.1016/j.jneb.2011.05.017.

12. Neufeld HT, Marchessault G. Perceptions of 2 generations of aboriginal women on causes of diabetes during pregnancy. Can J Diabetes 2006;30(2):1-8. Available from: doi:10.1016/S1499-2671(06)02008-9.

13. Elamurugan K, Esmaeilisaraji L, Strain J, Ziraldo H, Root A, MacDonald H, et al. Social inequities contributing to gestational diabetes in indigenous populations in Canada: A scoping review. Can J Diabetes. 2022;46(6):628-11. Available from: doi:10.1016/j.jcjd.2022.05.003.

14. Scott KA, Britton L, McLemore MR. The ethics of perinatal care for black women: Dismantling the structural racism in “mother blame” narratives. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs. 2019;33(2):108-7. Available from: doi: 10.1097/JPN.000000000000039.

15. McLemore MR. What blame the mother stories get wrong about birth outcomes among black moms [Internet]. Center for Health Journalism. 2018 March 14. Available from: https://centerforhealthjournalism.org/our-work/insights/what-blame-mother-storiesget-wrong-about-birth-outcomes-among-black-moms [Accessed 8th Jan, 2024].

16. Molinaro ML, Evans M, Regnault TRH, de Vrijer B. Translation developmental origins of health and disease in practice: Health care providers’ perspectives. J Dev Orig Health Dis. 2021;12(3):1-7. Available from: doi:10.1017/S2040174420000483.

17. Harris KM, McDade TW. The biosocial approach to human development, behavior, and health across the life course. RSF. 2018;4(4):2-26. Available from: doi:10.7758%2FRSF.2018.4.4.01.

18. Winett LB, Wulf AB, Wallack L. Framing strategies to avoid motherblame in communicating the origins of chronic disease. Am J Public Health

doi: 10.35493/medu.45.22

AUTHORS:

PARTH ARORA 1 & ADITYA MISRA 1

1Honours Integrated Science (Biology Concentration), Class of 2026, McMaster University

ARTIST:

STEPHANIE ALELUYA 2

2 Bachelor of Health Sciences (Honours), Class of 2026, McMaster University

The “Orange Jumpsuit” stigma reflects many complex issues found at the intersection of criminal justice and healthcare.1 It represents the widespread prejudice and discrimination faced by incarcerated peoples, particularly regarding their access to adequate healthcare.2 In prisons, healthcare is often perceived as a secondary concern to societies, overshadowed by the punitive aspects of imprisonment.3 This stigma can lead to significant health disparities as a consequence of poor quality care, as seen by the increased onset of mental and physical illnesses. This is particularly seen in the case of Alzheimer's disease and cardiovascular disease within incarcerated populations.3

The Orange Jumpsuit stigma has serious impacts in medical and societal contexts. Adequate prison healthcare is not just a matter of human rights, but is instrumental to the successful reintegration of incarcerated peoples into society.4 By ensuring that standard medical care, mental health support, and rehabilitation services are received, prisons can facilitate smoother transitions for incarcerated people post-release, thereby reducing recidivism and enhancing community safety.5

This article aims to explore the health disparities fostered by the Orange Jumpsuit stigma and examine the ongoing efforts to mitigate these challenges. It seeks to provide an understanding of the current state of prison healthcare, the obstacles incarcerated peoples encounter when accessing healthcare, and the initiatives being undertaken to bridge these gaps, addressing the overarching stigma associated with incarceration.

The origin of the Orange Jumpsuit stigma is deeply rooted in societal attitudes towards incarcerated peoples.6 These attitudes are often shaped by a mix of fear, misunderstanding, and a punitive mindset that portrays incarceration as a means of retribution rather than rehabilitation.7 This perception feeds into a cycle where prisoners are dehumanised, and their basic needs, including healthcare, are overlooked by society.6 The stigma is further perpetuated by media portrayals that often depict incarcerated peoples as irredeemable, thereby reinforcing harmful stereotypes and public indifference toward their well-being.6 This stigma has a profound impact on healthcare policies within