8 minute read

Coin-Gate: Who Stole Yale’s Doubloon?

Seventy years ago, five burglars stole nearly one million dollars worth of coins from the Yale Numismatics collection. We still don’t know who they were.

By Lara Yellin

Advertisement

on the night of May 29th, 1965, five masked men broke into Sterling Memorial Library. The thieves hid among the stacks of old books before overtaking the night guards and breaking into the basement vaults. That night, they would carry out four thousand looted coins, weighing about sixty pounds, from the Yale Numismatics collection—one of the most decorated and valuable coin collections in the world. Among their loot, they took Yale’s famed Brasher Doubloon, the first gold coin produced in the United States following independence. Altogether, the stolen artifacts totaled a value of almost one million dollars at the time—the largest robbery New Haven had ever seen. The case remains unsolved.

“The theft was carried out with expert selectivity,” explained James Tanis, the University Librarian at the time, in a June 7, 1965, Yale University News Bureau press release. “Only a limited number of the stolen coins are unique and readily identifiable . . . In some instances, the thieves selected from individual trays only those coins combining high value and potential for undetected sale.”

Only a discerning eye can identify details that make coins more valuable, like their metallic composition and historic origin—the thieves had that eye. The press release also noted that the heist relied upon the “deactivation of burglar alarms and knowledge of the details of the safe keeping of the collection,” both well-kept secrets of the University Library. The thieves knew what they were looking for, and they knew how to get it.

Complete records of the coins in Yale’s numismatics collection were never made, largely because of the inconsistent means used to acquire them. Yale’s collection was obtained through various donations and gifts made by life-long collectors affiliated with the University, growing to more than one hundred thousand coins over two hundred years. By the time of the heist, only those who routinely handled the collection or assisted with its curation knew its specific contents. The collection’s long-time curator, Theodore V. Buttrey, was one of the only people with the memory and experience required to be able to recount the collection. Just before the heist, however, Buttrey left his curatorial position to become a professor of Greek and Latin at the University of Michigan.

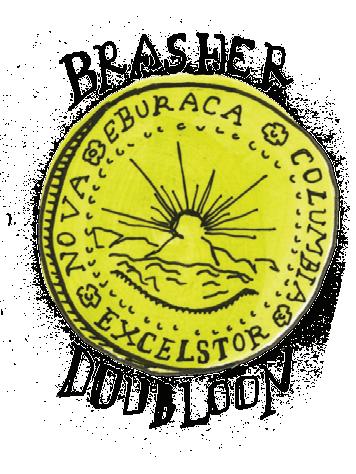

Following the break-in, Sterling Library administrators called Buttrey back to New Haven to identify the missing coins and provide an estimate of their cumulative value. The previously mentioned University press release also outlined these missing objects; the first page, titled “pieces easily identifiable,” contained the descriptions of only seventeen coins. To the untrained eye, the rest of the list read as disorganized and incomprehensible. To numismatists, however, attuned to the differences in composition and origin of the stolen coins, patterns appeared immediately—almost all of the collection’s American and English gold coins, for example, were stolen. The absence of one particular coin was conspicuous: Yale’s Brasher Doubloon. A 1981 New York Times article described Brasher Doubloons as “known among coin collectors as well as a Rembrandt among art lovers.” Ephraim Brasher, a New York goldsmith, forged only seven of these valuable gold coins in 1787. Brasher’s doubloons were made in the pre-federal period, before the establishment of the Philadelphia mint. Prior to the federal production of money, different types of metals were used to form the same coins, creating disparities in what should have been consistent values. Brasher would assay the coin’s actual value by measuring its weight in gold to ensure a standardized value. Upon completion, he would stamp the coins with his hallmark ‘EB.’ In addition to the coins’ pure composition and EB impression, the elaborate and unique designs covering each doubloon added to their historical and monetary value. The coins circulated in New York following their production, and in 1944, New York’s Holy Trinity Church donated one of the seven coins to Yale’s growing numismatics collection.

Yale’s famous coin was not missing for long. Two years after the 1965 break-in, Richard F. Andrews, an insurance agent specializing in the discovery of lost valuables, recovered the doubloon in Miami. According to a 1982 New York Times article, Andrews was working a different case in Florida when he “came across a trail” that led him to the Doubloon. The same article noted that Andrews “traced [the coin] through underworld figures to a coin collector in Chicago” but maintained that the coin was found in Miami. Andrews refused to provide further information about the coin’s recovery to the Times, adding only that “no money exchanged hands” in return for the doubloon. He only explained that the “investigation of the missing coins is still active—if I reveal any details, it will make the job much more difficult.’” needed the extra income to help fund the construction of the new Mudd library, leveraging the coin for a $650,000 payout. Following its sale, Yale added that concerns over the security of the Doubloon contributed to the decision

The five men made it out with over seven thousand coins, exceeding a modern value of ten million dollars. Among the loot was one of the other seven existing Brasher Doubloons.

Despite Andrews’ discretion, virtually no progress has been made on the case since 1967. Only one person has been convicted of a crime relating to the heist: John Reisen, an employee of the Chicago-based Columbia Stamp and Coin Company, was found storing sixty-nine of Yale’s missing coins in the company safe. The Yale Daily News reported on the event, emphasizing hope that Reisen’s arrest would lead to further discoveries relating to the heist. No further arrests have been made in the sixty-five years following.

Yale librarians and administration seem to want to leave this dramatic component of their numismatics career in the past. In 1981, Yale decided to sell their recovered Brasher Doubloon despite the energy and expenses invested in its recovery. The University reportedly

Yale’s numismatics collection has continued to grow in prestige and contents, despite its doubloon-less state. Perhaps the University’s eagerness to rid themselves of the Brasher Doubloon reflects their desire to move on from the embarrassment of the heist.

There is no shortage, however, of stories of other numismatic-related crimes. Contrary to the popular perception of coin-collecting as a hobby, drama is rampant in the numismatics community. Just two years after Yale’s break-in, millions of dollars’ worth of coins were stolen from the Miami mansion of Willis H. du Pont, the former Chief Executive Officer of General Motors and a famed numismatist. The mansion’s alarm system reportedly failed to turn on when five masked burglars entered in the night. Du Pont interpreted the thieves’ demand to give them “the money” too literally, and led them to his basement coin collection.

According to another article published by the Professional Coin Grading Service, one of the Miami thieves decided to keep a stolen coin for himself. He happened to select the Brasher Doubloon. For safekeeping, he taped it to his ankle. A few months later, he was admitted to the hospital following a severe beating by his mafioso father-in-law. The nurses attending to him found the doubloon still taped to his leg, recovering a coin worth nearly one million dollars.

Unlike the du Pont robbery, which is well-recorded and well known among coin collectors of varying degrees of seriousness, the infamous Yale Numismatics Collection heist is only infamous among those entrenched in mint madness—a small, but dedicated audience. This is despite the odd similarities in the cases. Even Yale’s undergraduate coin community was largely unaware of the dramatic know it. Noah said, “The President of [Heritage Auctions] was on the phone speaking with anonymous buyers bidding through the phone. There is a lot of anonymity within the coin world.” He explained that security is a large issue that most collectors, buyers, and sellers often worry about. the black market or liquified for its component assets, are often the subject of large robberies. What makes this heist so peculiar is its lack of closure.

Yale heist, until after the inaugural meeting of the Yale Numismatics Club, formed in 2021 by undergraduate numismatists eager to work more closely with the famed collection.

“A lot of people imagine coin collectors as nerdy kids or really old men,” said Noah Savolainen ’25, a sophomore in Grace Hopper College and co-founder of the Numismatics Club. “And there are a lot of those. But many coin dealers are just successful finance guys or suave high school dealers who sell coins instead of drugs.” Like the Yale heist revealed, the coin world can be equally lucrative and deceptive—traders need insider knowledge and a reputation of integrity within the community.

“I’ve been involved with coin collecting for a very long time, and it’s become a social and professional element of my life, on top of it being a hobby,” said Savolainen. He’s not alone. A few days before Savolainen spoke with me, he had been in Florida at the Florida United Numismatists (FUN) show, which attracts hundreds of dealers and thousands of attendees.

“Coin collecting is a hobby for almost everybody who’s involved with it, and a business for the others,” Savolainen explained. At FUN, Savolainen attended an auction offering coins from the collection of Harry Bass—a millionaire financier and avid numismatist—with sales that totalled $24 million.

The auction is a high-energy scene. Objects smaller than an iPhone can pack a room with people willing to spend millions on a single coin. Someone attending their first auction, or perhaps even their first coin show, could be seated next to someone with a world-renowned collection and never

Christian Hartch, a junior at Princeton University and fellow numismatist, reinforced this concern. He and Noah recently visited the New York International Numismatics Conference, where World Numismatics—a collection showing at the event—claimed to have around six figures worth of coins stolen from the show. Hartch said, “There’s always stuff going around, getting stolen.”

But despite this rather dramatic element of the coin world, it is not often talked about or highlighted as a large component of the community culture. In fact, Hartch, who created and runs one of the largest coin-oriented YouTube channels—Treasure Town Coins, with over one hundred thousand subscribers—had not even heard of the Yale heist until he learned of this article.

The heist that occurred at Yale seventy years ago was not rare in that valuable objects, easily used as collateral on

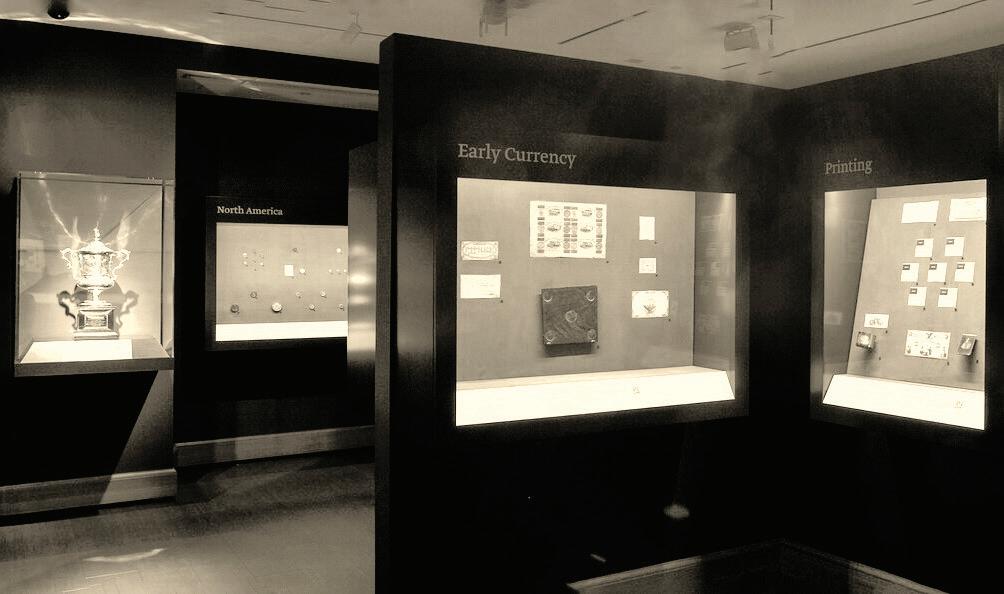

Today, Yale’s numismatics collection is alive and well. In 2001, the continuously growing collection boasting three hundred thousand coins moved into the bright, beautiful Bela Lyon Pratt Gallery of Numismatics in the Yale University Art Gallery. The gallery is composed of two adjacent wood-paneled rooms. The room on the right takes up the valuable real estate of a museum corner room with large, undisrupted windows looking down on Chapel Street. It houses just one large table that sits surrounded by a small library of worn books. The adjacent room of the gallery more resembles a maze of history, housing multiple floor-to-ceiling shelving units tightly packed with foam and leather padding. Despite the romantic and grand atmosphere of the gallery, unlike the glamorous drama of the fine arts community and their million-dollar mysteries, no one wants to talk about the successful collection’s mysterious past. Even the current curators of Yale’s collection—who hold the responsibility of elevating the collection’s profile—declined to comment on the crime. For now, things remain quiet and unsolved in the mystery of the missing coins. No one seems to want to dwell on it. Few even know about it. ∎