8 minute read

The Rise and Fall of the Elm City Express

For a glorious two years, New Haven had a soccer team.

Advertisement

By Maggie Grether

In the stands of Yale’s Reese Stadium, four drummers pounded out a roiling beat. Their heads bobbed in telepathic communion as the rhythm rolled through a crowd of over three thousand people.

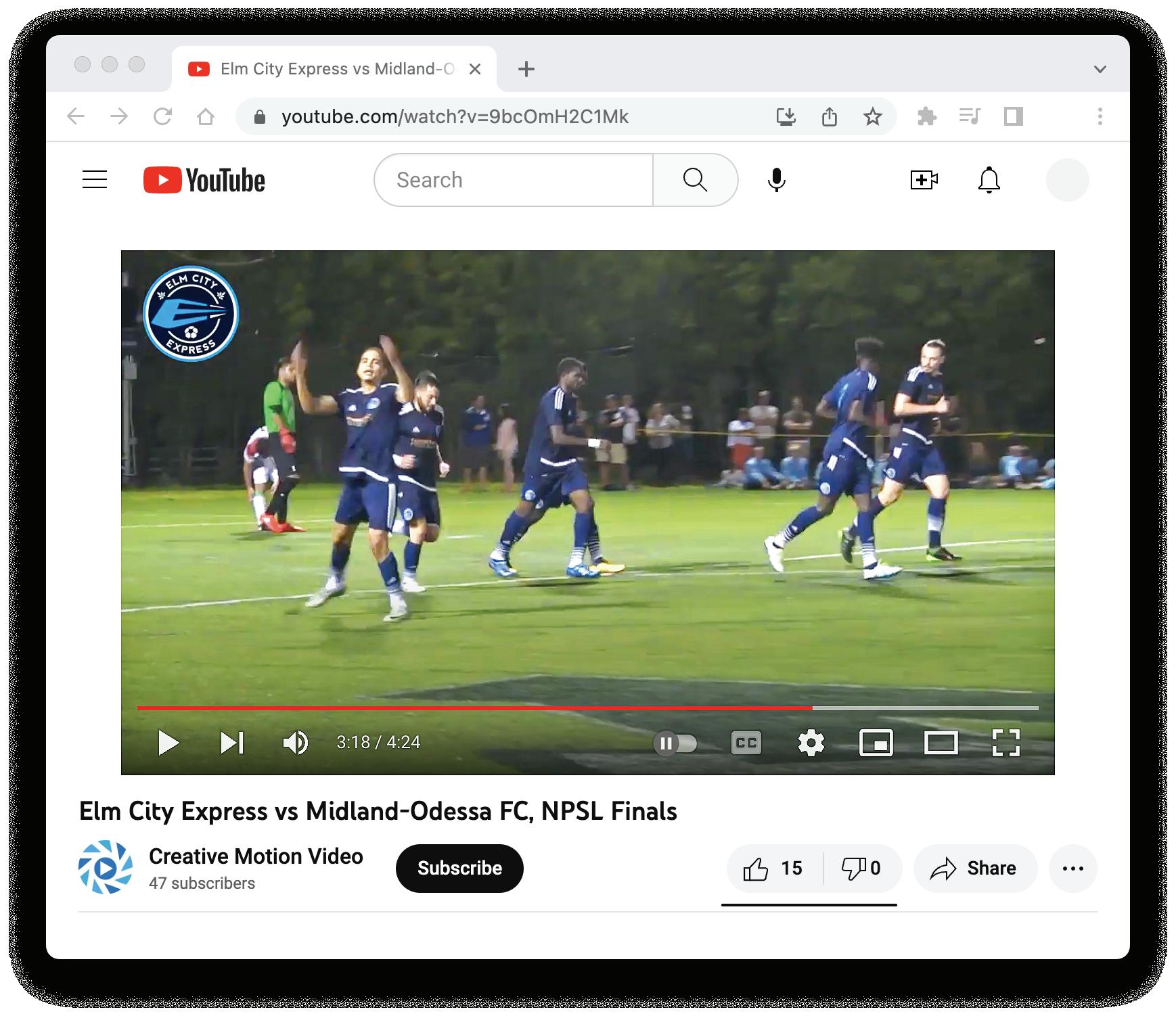

It was August of 2017, and fans had gathered for the championship game of the semi-pro National Premier Soccer League, or NPSL. The final was a showdown between Texas’s Midland Odessa F.C. and the Elm City Express—New Haven’s fledgling team, which had remarkably risen to the league championship in its inaugural year.

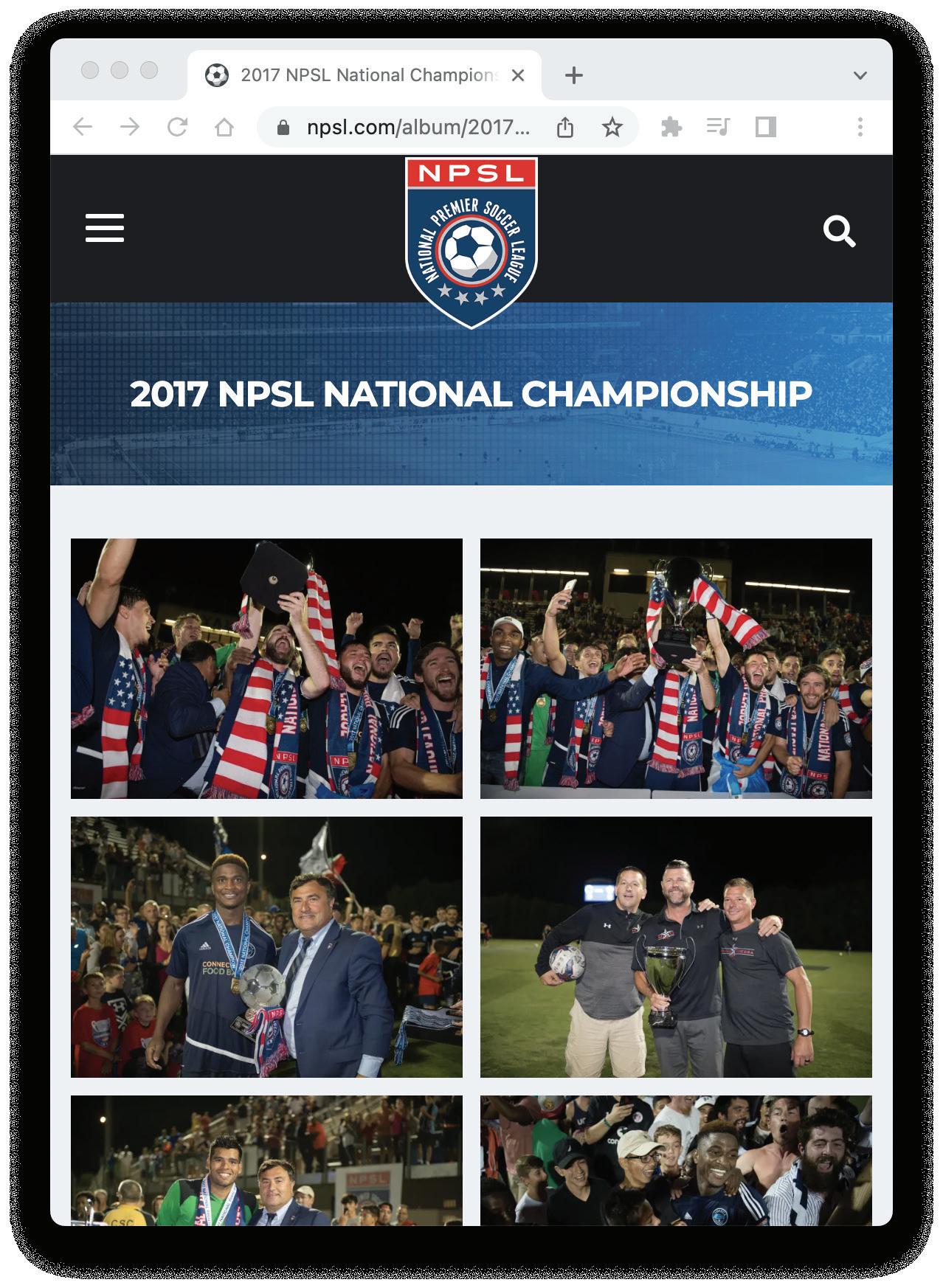

The game’s first goal came when Tavoy “Bull” Morgan, Elm City’s fleetfooted top scorer, twisted past three defenders to slot the ball into the corner of the net. Minutes later, Morgan scored again: a mid-air volley with his right foot, which blasted the ball to an impossible space just between the crossbar and the keeper’s outstretched fingers. In celebration, the Bull rammed a defender to the ground and sprinted to the stands with his hands cupped behind his ears to hear the fan commotion. More goals followed—the final score: 5–0, Elm City Express.

The 2017 NPSL championship marked a high in New Haven sports. Over the past century, the city has seen a hockey team, a baseball team, and another soccer team come and go. And by 2019, Elm City had disbanded too, leaving New Haven, once again, without a professional sports team.

But during that 2017 season, a new team and an eager fan base briefly alchemized into something unstoppable. “We started in the cold of February, and we ended up winning it by August,” remembers former right winger Shaquille Saunchez over a phone call last December. “It’s a journey that probably we will never forget.”

An online search for Elm City Express leads you five thousand miles south to the Brazilian state of Santa Catarina. The team was owned by the company K2 Soccer North America and its affiliate K2 Soccer South America, which also oversees a Brazilian soccer club. Both companies operate under the Brazilian-based investment outfit Baltoro Group. The reason why K2 Soccer landed in New Haven remains somewhat unknown—but when the company arrived, they found a rich history of soccer in the city.

Josh Nelkin was an Elm City fan and is a former player for the New York

Matches drew in die-hard soccer heads and people new to the game, young kids who dreamed of one day playing under an Elm City jersey and older fans Nelkin recognized from his pickup days, fans from a variety of cultural backgrounds. Even local Arsenal and Liverpool supporters quelled their rivalry to unite behind Elm City.

Ukrainians, an amateur soccer club. He remembers growing up in New Haven in the eighties and nineties among a vibrant and welcoming pickup soccer scene, rooted in the city’s European, Latin American, and African immigrant communities. Nelkin had always wished for a Connecticut soccer team. “A New Haven-based team seemed like a far, far, dream,” he tells me over the phone.

Nelkin’s dream became reality when Elm City arrived in 2017. The team built a roster based on local talent: in addition to a few loan players from K2 Soccer’s Brazilian club, management recruited heavily among soccer alumni from Post University, University of Connecticut, Quinnipiac University, Sacred Heart University, and other Connecticut schools.

“[Elm City] were the unifiers, all barriers were broken,” Nelkin remembers. Matches drew in die-hard soccer heads and people new to the game, young kids who dreamed of one day playing under an Elm City jersey and older fans Nelkin recognized from his pickup days, fans from a variety of cultural backgrounds. Even local Arsenal and Liverpool supporters quelled their rivalry to unite behind Elm City.

Some of the team’s most loyal fans included participants of Elm City Internationals, a New Haven organization that offers academic and soccer programming to low-income youth, especially immigrants and refugees. Lauren Mednick, the organization’s founder, remembers her students collecting autographs and kicking the ball around with players after matches. Outside of games, a few Elm City players tutored and coached students during their summer academy. Mednick would take students to practically every match, even traveling out of state so kids wouldn’t miss a chance to see their favorite players. “It was really something that they looked forward to, especially our youngest kids at the time. They really idolized the players and got to know the players,” Mednick says, and even over our crackly phone call, I can hear the smile in her voice.

Head coach Ted Haley remembers that the number of fans grew steadily with each game. “It was kind of like the new restaurant that people start to rave about,” Haley says. “We were lucky enough to catch fire.” with the Brazilian management and a lack of enough funding to carry on past the 2018 season.

According to Haley, the team also had supporters’ groups, or fan clubs, including a group with a New Haven pizza theme. “My kids still sing the songs that they were singing,” he adds.

The pizza song, I discovered, was to the tune of “Seven Nation Army.” Its composers were members of an Elm City supporters’ group known as the Brick Oven Brigade.

I meet Ed Foley, one of the Brigade’s founding members, at The Cannon, a soccer bar on Dwight Street. The Cannon is styled like an English pub and home to the New Haven Gooners, a local fan base of the English Premier League team Arsenal F.C. Behind the bar, amidst a red collage of Arsenal memorabilia, hangs a blue Elm City scarf.

Foley, who is trim with a well-kept goatee, is a regular at The Cannon and a long-time member of the Gooners.

He spins stories expertly, never pausing or backtracking, and his speech is peppered with references to mythology and ancient history I have to look up after we talk. There’s a palpable excitement in his voice as he recalls stories about Elm City.

With fans dispersed among Jess Dow’s bleachers, the games lost their original intimacy.

Foley describes Elm City’s 2017 season as “the halcyon days,” and the games as the “the greatest open mic night in all of New Haven.” He and his friends would sit behind the goal and poke fun at the opposition’s keeper—giving them nicknames or calling them by celebrity look-alikes. He remembers once yelling at the opposing team as they lined up for a defensive corner kick until a defender stopped, turned around, and started laughing. “It was—how would I put it . . . not a hostile atmosphere, but an imposing atmosphere of just we’re gonna laugh at you for like ninety minutes and offer you a beer afterwards,” Foley says.

In the YouTube recap of the finals, after Elm City wins, players and fans melt onto the field in a screaming, jumping mass. Fans shake blue and white scarves while the silver cup gleams overhead.

The Brigade was born when Foley bought a $3.50 Italian flag emblazoned with the word “ PIZZA” off of Amazon. But he objects when I refer to him as a founder of Brick Oven Brigade. “It really wasn’t anything that formal,” he says, “we were just local dummies.”

While Foley has scrubbed Brick Oven Brigade socials off the internet, the now-inactive Facebook of a different supporters’ group lingers as a snapshot of that exciting time in Elm City Express history: The Yard Dogs, named after guard dogs that roam rail yards to protect trains. Their posts are just as aggressive as the group’s name suggests, tearing into their Connecticut rivals, especially Hartford F.C. , and reveling in Elm City’s dizzying rise.

For that 2017 season, Elm City Express had no brakes. They rolled through the regular season with a 9–2–1 record. In the postseason, they glided past their first four opponents, scoring eleven total goals and conceding only one. Suddenly, the team had reached the league championship.

In the YouTube recap of the finals, after Elm City wins, players and fans melt onto the field in a screaming, jumping mass. Fans shake blue and white scarves while the silver cup gleams overhead. Mednick remembers players hoisting one of her students up on their shoulders in the middle of the field. In the back, you can see Foley waving the PIZZA flag.

“It was like the epitome of local team wins,” says Foley. He went to Christy’s, a soccer pub at the time, and partied with players after the game. “It was just a real good night. One of those feelings that you only really get with a semi-professional team.”

Loose summer nights stiffened into a Northeastern autumn, and Elm City entered the off-season. When the team returned in 2018, Nelkin, Haley, Foley, and the players I talked to said the urgency and energy of the first season had dissipated.

First, Elm City lost their home turf. When Reese Stadium underwent renovations in 2018, the team moved to Jess Dow Field at Southern Connecticut State University. Dow Field was twice as large as Reese and less centrally located.

The roster changed, too. According to goalkeeper Matt Jones, nearly all players worked separate jobs to supplement their income, making it difficult to keep players longterm. In the background, rumors floated about conflict

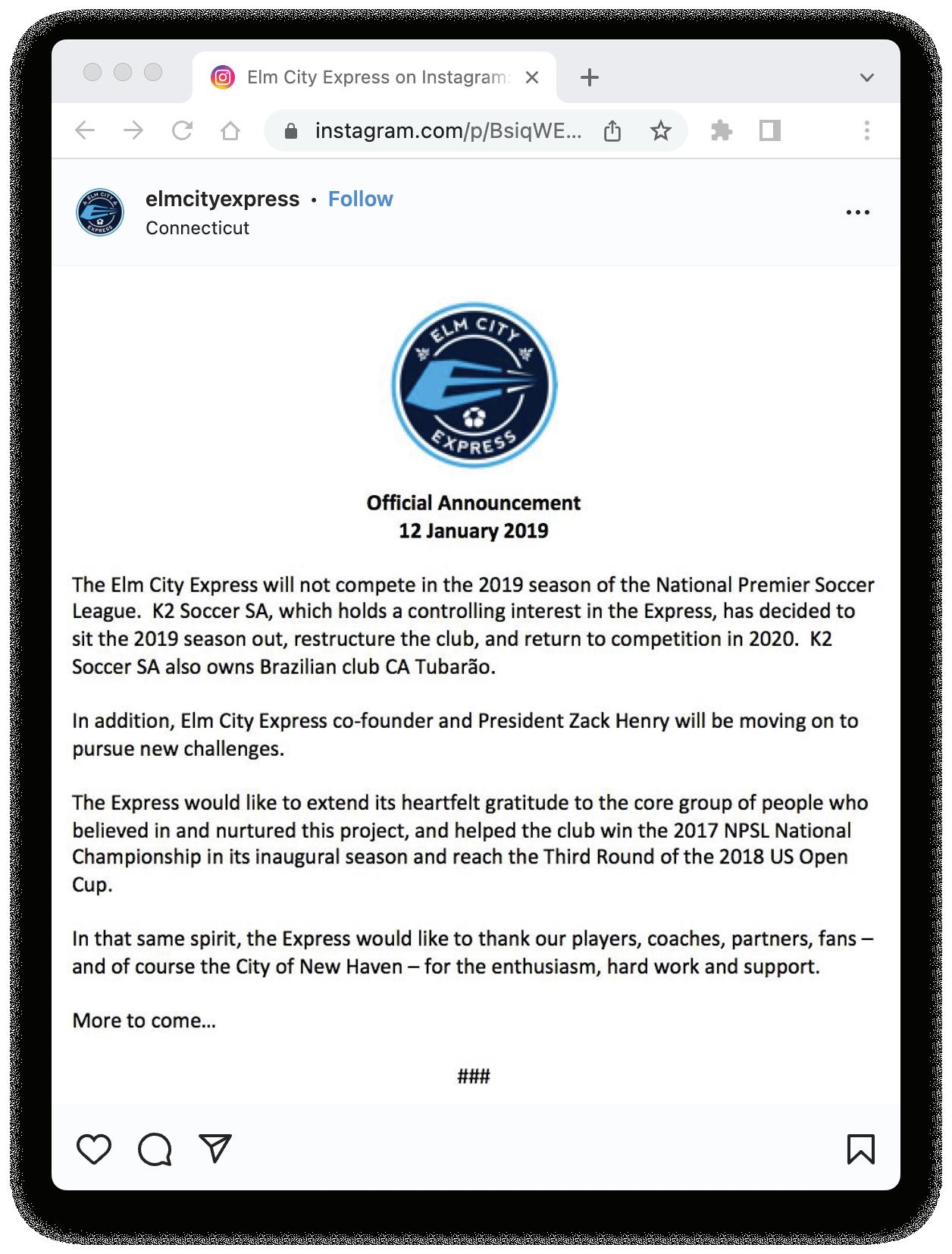

The official announcement that Elm City would not participate in the 2019 season appeared on the team’s Instagram in January. It remains the last post on the account.

There’s no epic trainwreck to mark the end of Elm City Express: just a scattering of gently rusted remains. As I collected bits of the team’s story, I wandered through abandoned social media accounts, old YouTube clips, and corporate websites translated from Portuguese; I learned about the pickup soccer games that used to rule Yale fields and heard strange stories of hundreds of Elm City scarves spontaneously appearing at the local Savers. Slowly, an image began to emerge—one of a team so intimate, so tangible for fans that, for one summer, it became transcendent.

In one telling, the story of Elm City Express ends in a surprising tragedy: a source of joy for New Haveners vanishing with no satisfying explanation. In a different version, Elm City’s demise was inevitable. The very things that made the team special—its smallness, localness, its concentrated fanbase—made it difficult to pull in a wide group of casual viewers, creating a model too insular to survive long-term.

What I can say for sure, is that New Haven had a soccer team. A good one, too. They created something special at Reese stadium. But they’re not here anymore, and the craving for the energy, connection, and purpose Elm City generated for its fans remains. Nearly every fan I talked to expressed a hope that someday Elm City, or a local team like it, could return to the city.

Since the disbandment, some players joined other teams or started coaching, while others moved on to different professions. The players most involved with Elm City Internationals are still in contact with the kids they mentored, usually through FaceTime. Ted Haley remains at Post University. Foley has directed much of his energy back to the New Haven Gooners. He still has the PIZZA flag, however, packed away at his parents’ house.

Foley remembers his time with Elm City as a “weird little bright spot” in his life while he worked a job he didn’t like. For one excellent summer, he slipped into a routine: meeting friends for drinks, going to the game, winning, and then bringing everyone back to the bar to celebrate.

“Knowing the way it ended and how disappointing it would be, I’d still take it,” he says. “I wouldn’t even say bittersweet, just sweet memories.”

Nelkin hasn’t given up on his dream of a New Haven soccer team. He thinks the Elm City fan base lies dormant, ready to be resurrected at any moment. Yale’s renovated soccer field, set in front of the brick backdrop of Coxe Cage field house, reminds Nelkin of a small English stadium, and he believes that, if Elm City Express came back, they could consistently sell it out. Every time he passes the stadium, he peeks inside and imagines: the stands brimming with New Haven soccer heads, the pitch studded with players in navy shirts, the air filled with chanting, a shrill whistle, and the echo of drums. ∎

Previously incarcerated Connecticut residents face complicated barriers to receiving their licenses, making it difficult to get to work.