6 minute read

Piano Man

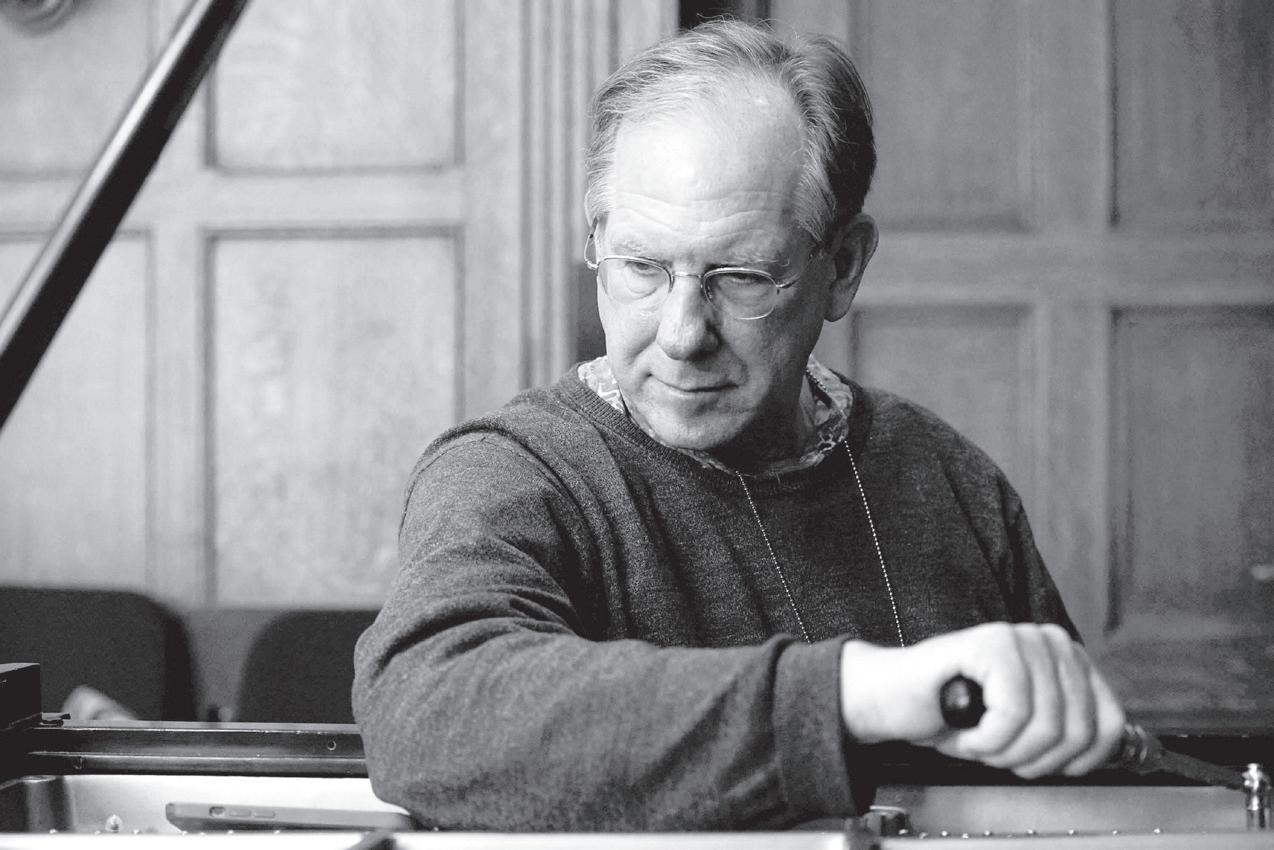

In the School of Music, piano technician William Harold has been attending the 130 Steinways for the last twenty-four years.

By Cora Hagens

Advertisement

My first impression upon meeting William Harold is that he has absolutely destroyed the piano in front of him. He’s trustworthy, of course, because he is a piano technician, but at the current moment the Steinway grand that he sits in front of looks genuinely wrecked. He’s taken it apart in ways I didn’t realize a piano could be taken apart. The keys, for example, and the entire action (the mechanism which translates a press of a key into a hammer strike) have been slid forward, out of the piano frame, and onto his lap.

Harold has been Yale School of Music’s resident piano technician since 1997, which means that he is responsible for maintaining the 130 Steinways (high-quality pianos built by Steinway & Sons) on the University’s property. He tries to stay invisible, but perhaps you’ve still heard him making his rounds between 8:30 and 5:00 every weekday, traveling between concert halls, practice rooms, and studios on campus. Each session takes him about an hour and a half, which means he tunes around four or five pianos every single day. Harold’s job requires more than simply tuning each piano, though. As I interrupt his session in Woolsey Hall, he’s adjusting what’s called a “backcheck”, a small block that catches the hammer so that it doesn’t bounce too far away from the string, allowing a pianist to repeat a note very quickly.

Harold grew up not far from New Haven in the town of Guilford, Connecticut, and studied physics at Hampshire College in Amherst, Massachusetts for two years. He had no formal piano training before college, but he started teaching himself to play on a friend’s keyboard, “to distract myself from all the physics.” At first, he taught himself by ear, improvising blues and jazz-inspired tunes, which he wordlessly describes by turning to the piano in front of him. “At Hampshire, my sound was all—” he improvises for a few minutes, leaning deep into the keys to churn out bluesy licks and progressions, reminiscing on the soulful sounds that first drew him to the instrument.

“Physics and music—you’re learning all about wave forms, and about how sound waves interact with each other . . . that was the perfect thing to be studying to do this because in the end, this is a mechanical acoustical phenomenon,” he explains. After graduating from Hampshire with degrees in both Physics and Music, he began working at the Sohmer Piano Factory in Ivoryton, Connecticut, much to his parents’ chagrin (“You go to college to get out of the factory!”). Forty years later, he’s still in love with his craft. He employs his physics degree as he describes the tuning pro- the inner mechanism of the instrument is still largely a mystery to me, so Harold invites me to peer into the piano with him as he launches into a patient demonstration of his process. Using the wrench, he starts to turn a tuning pin––a small knob that, when twisted, tightens or loosens a string in the piano, raising or lowering the pitch it produces. Each note is produced by three separate strings that are hit simultaneously by one hammer, so he must make sure that they’re all completely in tune with each other, and in equal temperament with the rest of the piano. He pounds the key as he tunes, moving his hand with the sound waves being produced by the two strings. He’s revealed something I wouldn’t have picked up on before—a beat within the sound, a wavering that lines up with the pulsing motion he’s making with his hand. He has a finely honed ability to hear that discordance, when the sound waves are “out of cycle,” as well as a tuner app on his phone, and he uses both to wiggle the tuning pin into its rightful place. After a few adjustments, the note rings out clearly. cess, explaining, “If you have two notes that are in perfect tune, then the crest and the troughs and wavelengths are all coherent. The waves are the exact same frequency and each crest is matching up with each crest.”

He pounds the key as he tunes, moving his hand with the sound waves being produced by the two strings. He’s revealed something I wouldn’t have picked up on before—a beat within the sound, a wavering that lines up with the pulsing motion he’s making with his hand.

Harold bends down to sift through his bag of tools, reaching for an oddly shaped wrench and two small rubber wedges. Although I myself am a pianist,

“Sometimes, over the years, just like anything else you do forever, there are some days where I’m just like, ‘what am I doing? I’m tuning a piano—what’s a piano?’” Harold admits to brief moments of existential crisis about a job where he is “just tightening and loosening strings all day,” but immediately thereafter he adds, with a hint of disbelief at his own good fortune, that “I’ve been doing this for a long time, and it’s still cool to me, isn’t that weird? I was lucky, you know?”

Harold has a riveting disposition. You can tell that he doesn’t often get the chance to talk about himself, and now that he has someone’s full attention, he barrels forward and answers questions without even needing to be asked. In a drawling voice, he speeds through physics-heavy explanations, graciously checking for comprehension every few minutes.

“You got that?” he asks, making eye contact.

“Uh-huh,” I say, nodding along, “and how––”

I don’t get my question in, but it’s O.K., because he’s started talking about something far more interesting.

“The ultimate goal is to make myself as invisible as I can, and the best way to do that is to do my job.” He tunes pianos before rehearsals and performances, long before anyone else has arrived. He tries to finish fifteen minutes before he’s supposed to, as it makes everyone nervous to see him doing last-minute touchups on the piano. Today, we’re sitting at the Steinway that lives in Woolsey Hall, Yale’s largest and most opulent recital hall, in preparation for a concert in the afternoon. This is already the third time this week that he’s tuned this specific piano, which seems both tedious and excessive, but he insists it is important for the success of tonight’s performance.

Join us!

“Well, you know, if something [goes] wrong I can always blame you, right?” he chuckles.

“Sure,” I offer. I’m definitely distracting him.

“No. I can’t. I can’t blame anybody, it’s my responsibility to get this thing done. I can’t blame anybody else,” he says with finality.

While he defends that it’s his responsibility to make sure the piano is in working order, he admits that he used had just spent two days perfecting everything within it. It was flawless.

“I see what the problem is, but I need a half an hour,” he told them. When the pianist returned from a walk twenty-five minutes later, Harold was pretending to finish up by twisting a tiny screw in the action (which he had simply rotated back and forth a few times). He set the piano up exactly the way it was half an hour earlier. The pianist re-attempted their piece, and Harold received a rousing round of thank yous for whatever miracle he had performed.

In this way and in countless others, Harold has been the unsung hero of hundreds of concerts held at Yale over the past twenty-five years. He’s set to retire at the end of this year, and he has a surprising plan for his well-earned free time.

“I’ve been taking [piano] lessons,” he says, “and I practice two or three hours a day when I come home, so I’ll have something to do.” to be tempted to make excuses for flaws in tuning jobs, likening this to inexperienced musicians who are quick to blame their instrument for flaws in their performance. He won’t give me any names, but he recounts a story of an accomplished pianist who was rehearsing in Woolsey Hall a few years back and complained about the piano action. Harold took a look inside the piano, even though he

He closes our interview by playing a full piece on the freshly-tuned piano, one he’s been working on with his piano teacher that’s been giving him a little bit of trouble. It’s a tango by Alberto Ginastera, and it sounds lovely. It’s not nearly the most difficult piece that’s been played on this stage, but William Harold plays with a remarkable amount of sensitivity. He’s spent the past forty years getting to know this instrument, inside and out, and now he’s finally getting a chance to play. ∎

Gilgamesh to Enkidu

The New Journal, founded in 1967, is a student-run magazine that publishes investigative journalism and creative nonfiction about Yale and New Haven. We produce five issues a year that include both long-form and short features, profiles, essays, reviews, poetry, and art. Email us at thenewjournal@gmail.com to join our writers’ panlist and get updates on future ways to get involved.

We’re always excited to welcome new writers to our community. You can check out past issues of The New Journal at our website www.thenewjournalatyale.com

We are becoming human together Washing dishes in the morning

Pulling spoons from the disposal

You move in your sleep so much it startles me Temple to Temple

We are slow to rise Wildly, You say, It takes so long to become a person

—Edie Lipsey