Workers show up. They are ready to learn from the moment they get to the barn. We all get distracted, but a worker is the one who puts in the extra time. They pick up, and help around the farm with whatever is needed. When they ride, they ride with a plan. They do transitions, and figures and have a goal. They ride without stirrups, without reins. They put in days of long, boring fitness rides because it is the right thing for the horses. They do the hard things, because it makes them stronger and better.

Chris Ritchey grew up on his family’s horse farm, famously home to Afleet Alex, the Preakness and Belmont Stakes winner. His passion for equestrian sports is deeply rooted in his heritage, with his father and grandfather accomplished in eventing, dressage, and showjumping. Chris actively rides and competes himself, training with Rebecca Robin at Robin Stables in Bridgehampton.

Along with his passion for horse riding, Chris is equally dedicated to real estate. He joined Compass in 2014 and most recently joined The Hudson Advisory Team, the #1 Mega Team in New York, where he leads the Hamptons division.

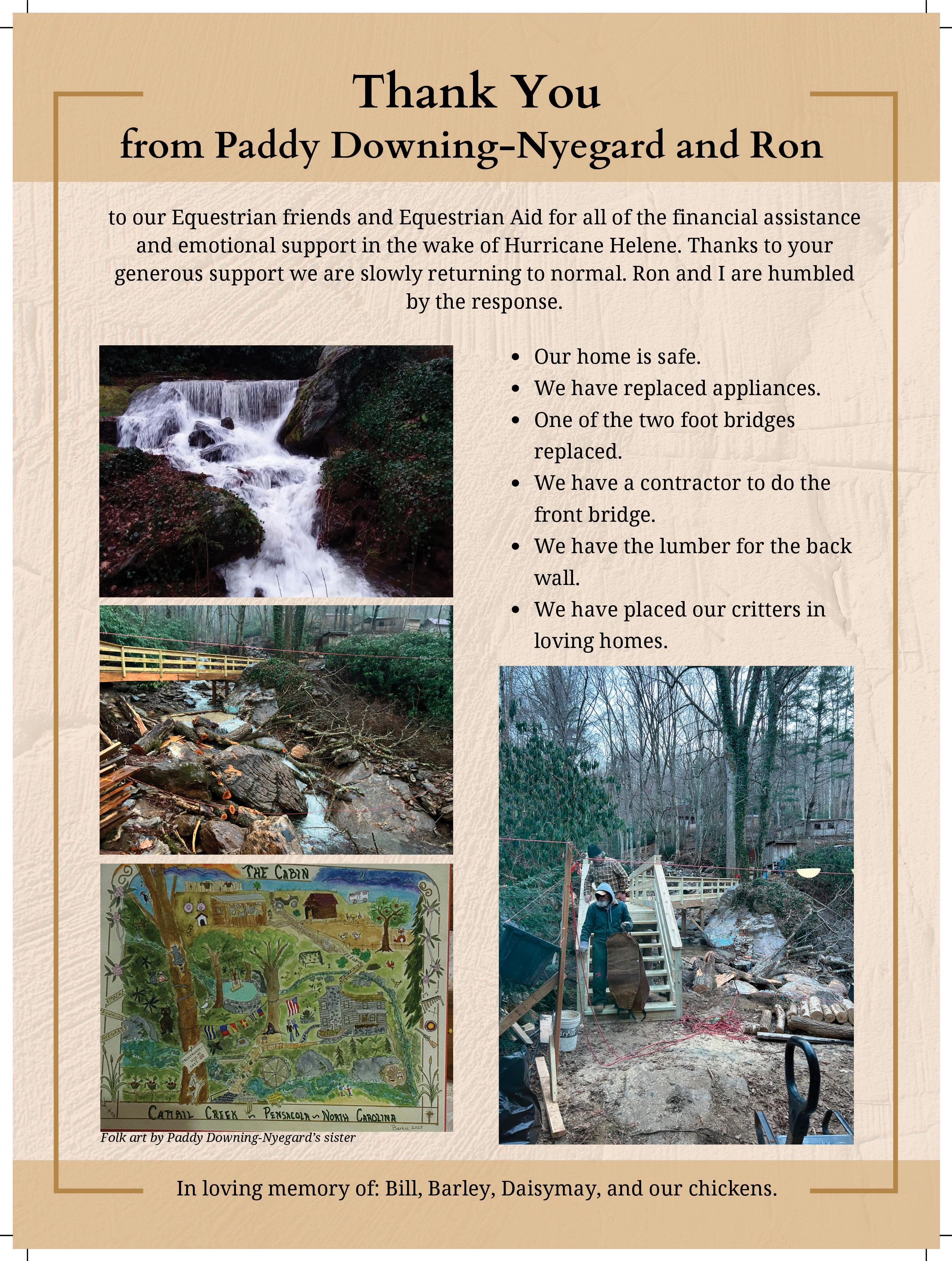

Chris is dedicated to providing clients with prime real estate opportunities, whether for a summer rental or a lifelong home. He guides clients through every transaction step, using his keen eye for design and staging. Chris also serves the community as Vice President of the Board for the Center for Therapeutic Riding of the East End and actively volunteers with East End Cares.

Your young equestrians deserve more than the standard horse barn. Build them a B&D equestrian facility, crafted for the champions of tomorrow.

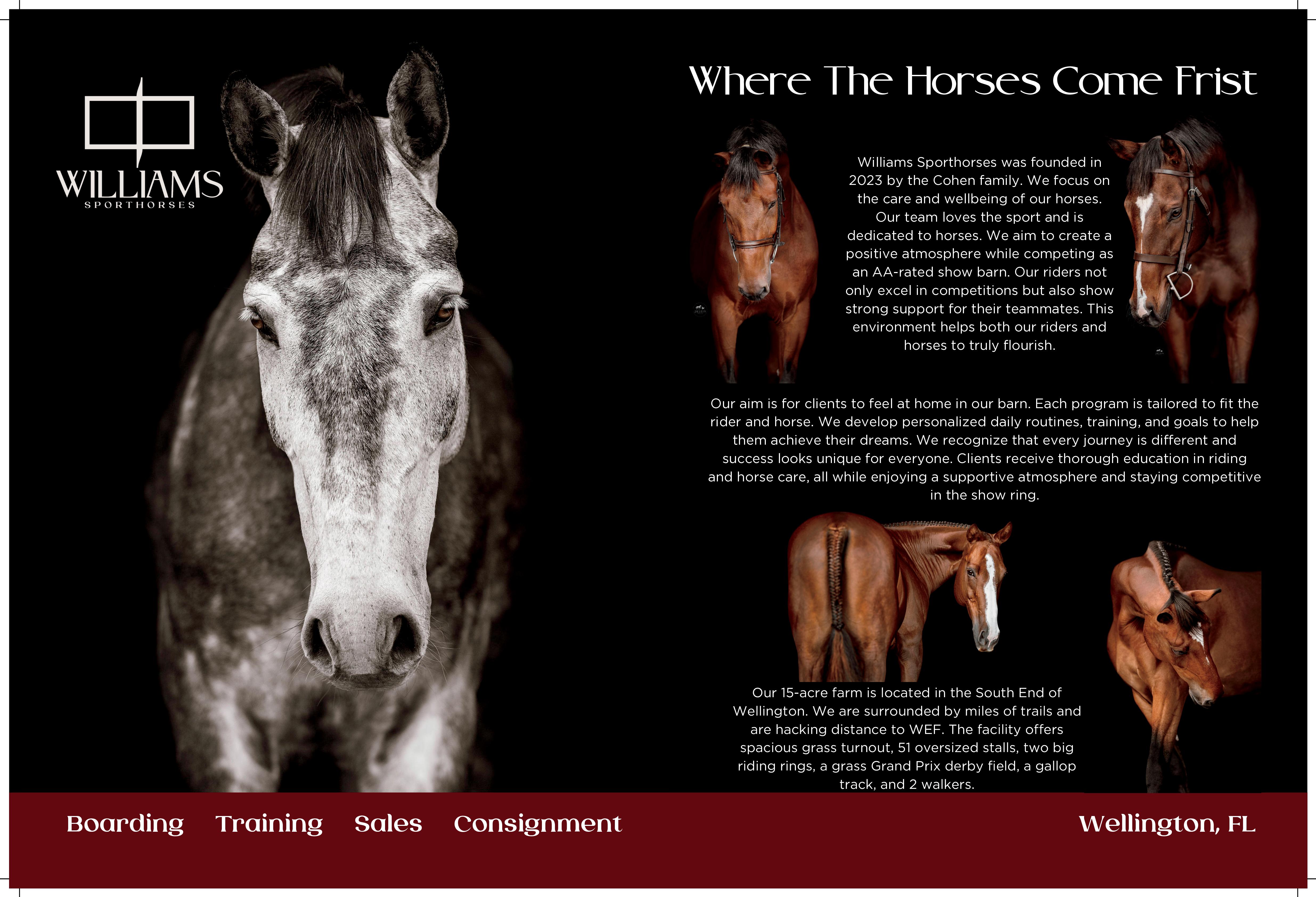

✰ Putting horse welfare FIRST!

✰ Taking care of your barn family.

✰ RESTING! You can’t perform at your best without rest.

✰ Making mental health part of regular conversations.

✰ Commenting on people’s accomplishments—not their bodies.

A low sugar and low starch forage blend enriched with probiotics to optimize microbiome function

An alfalfa-based forage blend that supports a healthy microbiome and promotes digestive performance

WHILE THE future of veterinary medicine can seem daunting on so many levels, it is impossible not to feel positive and optimistic after talking to Dr. Alberto Rullan, VMD. His story of passion for horses and growth in his education began at a young age. As he has expanded his practice and network, he has created pathways for more people to get involved and qualified at various levels of veterinary practices.

Alberto

Growing up in Puerto Rico, a country with no veterinary schools, Dr. Rullan experienced the heartbreaking loss of a family horse when he was just 8 years old. The horse was in a traffic accident with a truck and, even at that age, Rullan realized that a timely veterinarian could have likely saved the horse. (In reality, the vet couldn’t arrive at the farm for over

two days.) This experience crystallized his mission to figure out a pathway to become a vet himself, and a lifelong goal to provide exceptional equine healthcare to over a million horses.

“I worked hard to get good grades and my experience with horses was very intense—I had been following veterinarians around since I was 12. And when I was accepted to veterinary school I knew that’s where I was going,” Dr. Rullan tells The Plaid Horse

Coming from a rural farm family, Dr. Rullan faced multiple obstacles to his mission. Since there were no veterinary schools in Puerto Rico, he would have to go to the United States for college. This posed a challenge as he spoke no English and had limited financial resources. Undeterred, when he was accepted to Penn State University, he started his time

Dr. Alberto Rullan and veterinary technician Yazmin Rivera performing a flexion test

“I have never met one horse owner or trainer who wants to do harm to the horse,” Dr. Rullan says. “It’s about proper information and understanding.”

As equine healthcare evolves, many horse owners and trainers can be tempted by an over-reliance on quick fixes and supplements without understanding underlying issues. The Equine Performance Innovative Center offers a holistic approach that includes working to reduce drug dependence in horse treatments, utilizing a full range of various rehabilitation devices and healing practices, and educating owners about proper horse care.

“Just because you have all these machines and supplements doesn’t mean anything until you know what you’re treating,” Rullan adds. He advocates for a comprehensive approach that considers the horse’s natural environment and individual needs.

there learning English through an English as a Second Language (ESL) Program.

“Luckily, I was really good at math,” notes Dr. Rullan, as he faced his classes and language barrier with grit and determination. Upon graduation, he was accepted into the prestigious veterinary school at the University of Pennsylvania.

VETERINARY

Moving from Penn State to University of Pennsylvania meant relocating from a more rural community to a bustling metropolitan area. Unhappy in the city, he moved to a farm to work as a handyman and commuted to his classes.

Dr. Rullan matched with an internship program at Louisiana State University, where he learned practical veterinary skills. While internship programs are not required for veterinarians like they are for human doctors, Dr. Rullan believes most vets should take advantage of existing programs.

“There is a lot of theory, but in reality, when you graduate vet school, you don’t have the handy skills to be a proficient veterinarian. I truly believe an internship is the way to go because it gets you exposed to the practicality of the job,” he notes.

Through school, Rullan was often joined over the summers by his brother Willie.

When he started his first veterinary formal job in Ocala, Willie was happy to join him as a veterinary assistant. Their lives changed dramatically when Willie was kicked by a horse and his body was unable to recover, which ultimately revealed full-blown leukemia at age 22.

Experimental stem cell treatments were uncommon in most human medicine at the time, but Dr. Rullan had used it successfully in veterinary medicine. Applying the treatment to Willie’s care, he was able to make a full recovery. This experience further shaped Rullan’s approach to regenerative medicine but also put further strain on the brothers–not only did they have Dr. Rullan’s veterinary school debt of over $300,000, but they also now had $500,000 in medical debt. With their veterinary salary, they looked at all risks and opted to start their own business.

VETERINARY

Through his schooling, Dr. Rullan started to notice gaps in horse healthcare from many angles: language spoken between vets and horse care providers, practical experience of veterinary students, and a massive quantity of debt he was racking up in his education.

His experiences have inspired him to help others to alleviate as many of these

Need in the industry led Dr. Rullan to develop Equine Veterinary Programs through his Rullan University. There is a national shortage of veterinary assistants, which puts further strain on veterinary practices around the country and the world. Using systematic approaches developed in the field, Dr. Rullan teaches practical and hands-on anatomy, physical examinations, and handling critical situations.

Practical, hands-on skills learned in veterinary assistant courses include utilizing equine rehab modalities, sterile procedures and surgery preparation, equine reproduction, record-keeping, and equine ultrasonography.

Additionally, Rullan University offers Skill Improvement Programs for current veterinarians, which include regenerative therapies, rehabilitation, radiology, and ultrasonography.

Learn more about certified courses for Junior Vet Assistants, Senior Vet Assistants, and Advanced Vet Assistanst, as well as pathways for becoming a certified veterinary technician from Rullan University at rullanuniversity.com.

issues as he can. From improving communication between veterinarians and horse care providers (often bilingual), and pathways for those who want to join the veterinary profession as a veterinary assistant or technician.

With a vision to help a million horses, Rullan remains committed to evolving veterinary practice. His core philosophy is simple: understand the horse’s specific needs and approach treatment with knowledge, compassion, and precision.

WORDS: SONJA OCHADLIK

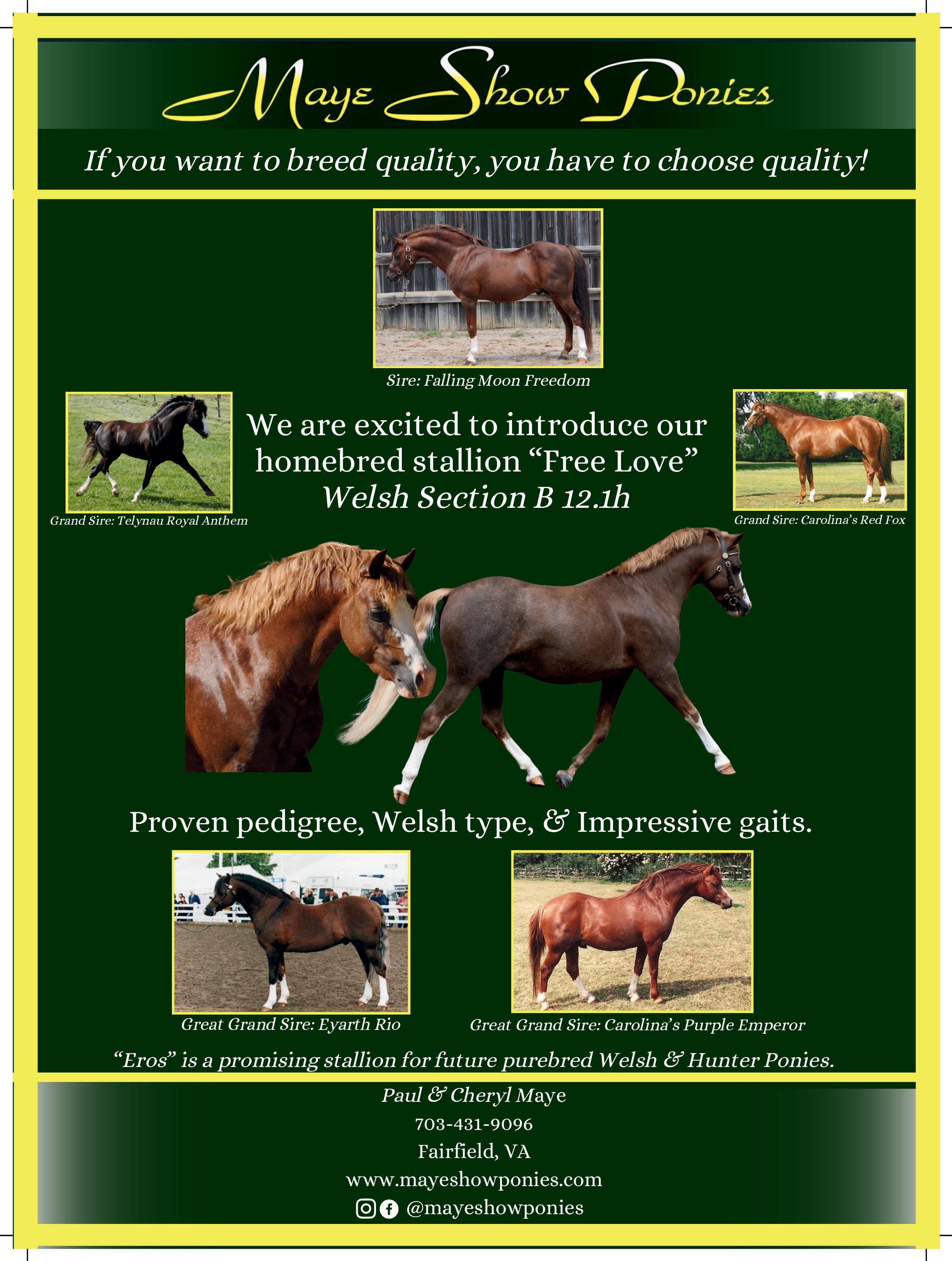

RECENT UPDATES to U.S. Pony Jumpers and proposed changes to U.S. Young Jumpers show us the current efforts to diversify the United States show jumping pipeline. These initiatives emphasize correct, safe, and welfare-driven development of both young riders and young horses. U.S. show jumping now has more pathways to nurture talent for high-level competition—which includes not only hopeful U.S. Team members but also aspiring professional young horse producers and beyond.

STARTING SMALL: CHANGES TO PONY JUMPERS

Previously, the Pony Jumper division in the U.S. left much to be desired. The original rules were inadequate, far inferior to other pony jumper systems globally, and severely underserving participants. There was only one pony jumper division open to junior riders and ponies 14.2 hands and under; jump height was listed as 1.05 m with a max specification of 1.15 m. At the 2024 edition of USEF Pony Finals held in Kentucky, only 13 ponies entered this division, compared to the 100+ entries in each of the Large, Medium, and Small Pony Hunter divisions.

To prepare for Pony Finals or even reach the Pony Jumper level, riders often had to compete in horse divisions with their ponies. This was not ideal, as the distances and course requirements were designed for horses, not ponies, which could be both ineffective for training and unsafe. There was no foundational system for a younger, smaller child to get experience in the smaller jumpers on a pony over a correctly set track of fences before taking to the national stage.

To address these issues, there is now the overhauled Pony Jumper divisions

SMALL PONY CATEGORY

Ponies not to exceed 12.2 hands, athletes USEF 12 years of age (maximum), fence heights .60-.65 m, not to exceed .70 m

MEDIUM PONY CATEGORY

Ponies not to exceed 13.2 hands, athletes USEF 14 years of age (maximum), fence heights .70-.75 m, not to exceed .80 m

LARGE PONY CATEGORY

Ponies not to exceed 14.2 hands, athletes USEF 16 years of age (maximum), fence heights .80-.85 m, not to exceed .90 m

1.05 CATEGORY

Ponies not to exceed 14.2 hands, USEF junior athletes, as dertermined under GR103 Fence heights not exceed 1.15 m

A Team Championship and an Individual Championship will be offered. The Team Championship will be a modified Nation’s Cup format (two rounds on the same day). The Individual Championship will be a multi-round competition.

SOURCE: USEF PONY JUMPER CHAMPIONSHIPS (2024) US EQUESTRIAN. ACCESSED 01/09/2025

and USEF Pony Jumper National Championships—new height categories for small, medium, and large ponies, in addition to the original 1.05 m championship. The new format provides courses set correctly for ponies, suitably sized jumps for the ponies for children to learn on, and an initial taste of team competition. While these changes provide safer, more educational opportunities than before, they also present a new kind of opportunity (see chart left). The traditional American pipeline for aspiring Olympic and Team USA riders starts, more often than not, in the hunter and equitation divisions. This pipeline can work; however, it may be appealing for some to start in the pony jumper framework to ride their way up the ranks.

Jumpers are a competition format that many parents can easily understand. Jumper rounds are judged on the horse and rider’s ability to first complete the course fault-free and then within various timing formats. The fault rules and timing formats are easy to learn quickly for an audience of parents or supporters. Jumpers allow for minor mistakes that are part of the learning process and don’t prevent success—an important aspect for children.

Financial constraints can make it difficult for some to participate in the sport, especially in the hunter and equitation divisions. These divisions are judged on an overall picture which requires a very specific type of horse, with added costs such as braiding. All different types of ponies can excel in jumpers, helping riders become better horsemen and improving accuracy, planning, and execution. A pony that is safe, rideable, and has aptitude for jumping can compete in the

jumper ring, offering an alternative to the more complex and costly demands of hunters and equitation. Jumper divisions still impart countless important riding skills such as: having a good position, an effective seat, how to pick up a good pace, ride a balanced short turn, be brave, and win. Beyond the riding and life skills participants gain, this program also offers emerging talents the opportunity to learn about educating and producing their own ponies.

Many young equestrians dream of becoming professional riders, winning at prestigious venues around the world and competing in the Olympics. Olympic riders might receive the most attention in magazines and online media. However, there are many extraordinarily talented riders and horsemen working within the global industry who aren’t on the Olympic track.

Of course, for success in the upper echelons of the sport, we want depth to the U.S. Team. Olympians and Team riders play a crucial role in the industry. They exemplify hard work and determination, inspiring riders of all ages while securing all-important media attention for the sport. But without breeders, owners, and good young horse producers, we don’t have Olympians.

The top sport is busy these days with shows week in and week out. In order to maintain status in the World Ranking, most riders don’t have time to be at home handling youngsters, taking them over their first jumps, their first training shows, and even their first international event. Young horse production can be a long road to success with the peaks and valleys of the learning process. Without recognition, there is less incentive for breeders, owners, investors, and riders to want to commit to the endeavour.

In Europe they overcome the obstacle of media attention by spotlighting young horse production in a number of different ways. For example, young horses have the center stage jumping in the same ring as the Grand Prix and Nations Cup at the Dublin Horse Show 5*. The FEI WBFSH World Breeding Championships for Young Horses in Lanaken, Belgium boasts hundreds of entries in each young horse age category. There, the breeders

and producers are awarded high praise for their horses’ success at all levels, from winning, to jumping a quality clear round.

Of course, a key consideration is financial—it is simply more economical to produce a horse in Europe than in America. Part of what keeps costs down in Europe is access to shows. Most places in Europe have access to numerous training shows and top-class international show venues all within an hour drive of their home farm. Europeans are able to go to a training show one week for an affordable entry fee and jump in the same arena over the same fences that will be jumped in the Grand Prix or a prestigious Young Horse class at a later date. This allows the horses to see and experience the main stage while jumping an appropriate height class without added pressure.

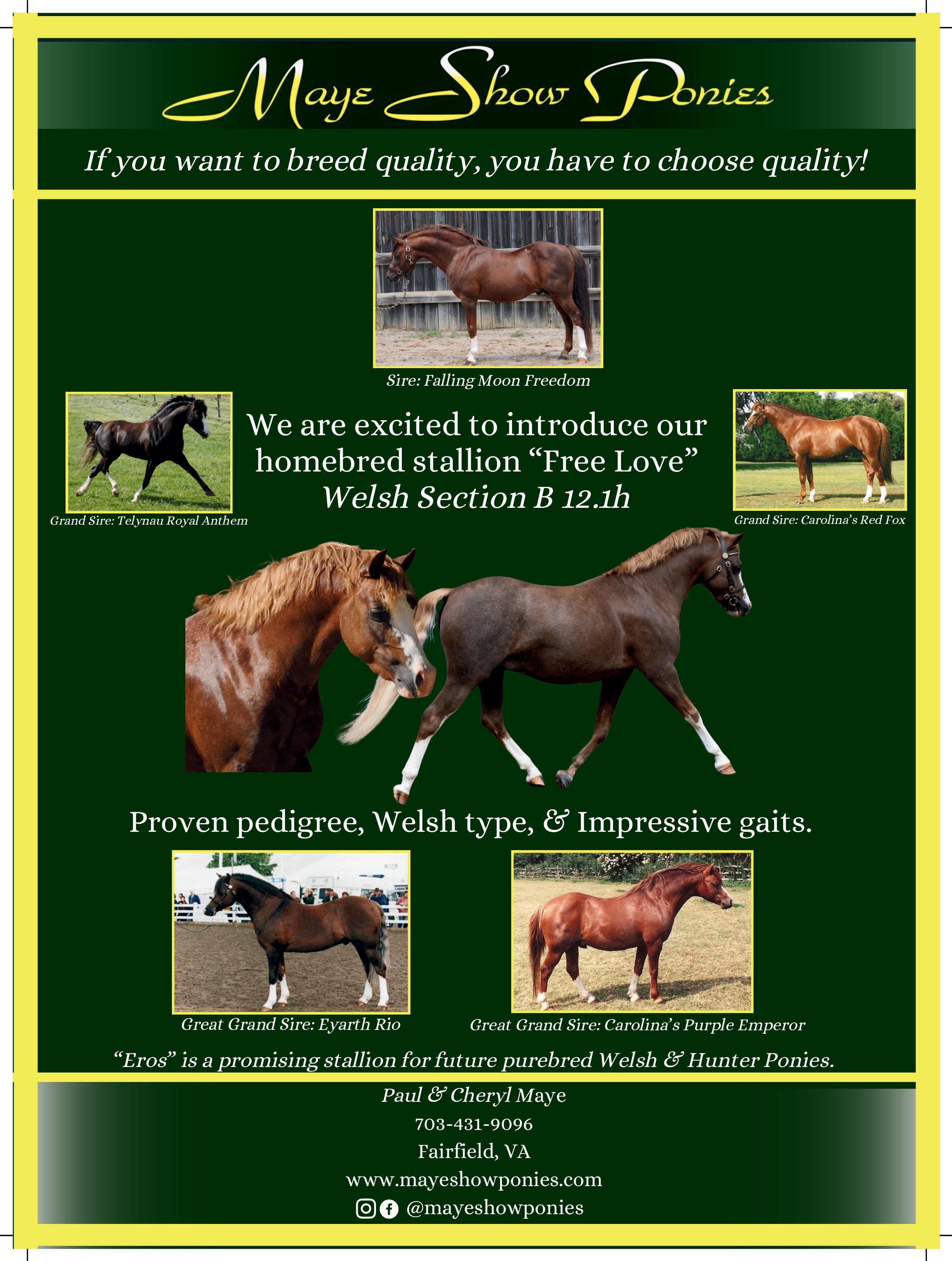

The USHJA Young Jumper Task Force has proposed a revamp of the Young Jumper classes that may address some of these factors that keep young horse production in Europe. Rule changes for young jumpers (JP 117) are currently awaiting approval from USEF. These proposed rule changes offer by height Young Jumper classes rather than age-related classes.

The proposed changes show continued support for this sector of the sport and allow a broader reach for young jumper competition entries (see chart right). The height classes allow for safety and welfare as a priority for horses, trainers and owner-riders alike. Equine welfare is at the forefront of much online discussion; this offers a competitive option for young horses to be developed at a pace to suit their individual needs.

Promoting this initiative from the Young Jumper Task Force will hopefully sustain growing interest and increase the number of entries. Show managers can then continue to offer and improve financial incentives for young jumpers, such as waiving nomination fees, lowered class fees, and providing generous prize money for their series finals. These incentives, coupled with an uptick in entries in young jumper classes and a well-attended U.S. National Championship, may attract crucial media attention. Media attention helps catch the eye of sponsors, owners,

riders, and audiences alike.

Exciting times ahead for the future of American show jumping! The current and proposed changes to the jumper rules promote welfare and inclusivity within the sport. They open up new pathways for aspiring young riders to achieve their dreams and become valuable members of show jumping community— whether that is young horse producer or a member of Team U.S.A.

About the Author: An American rider based in Ireland, Sonja works alongside her husband Johnathon at Stonehall Sporthorses. They focus on producing and selling top-quality horses and ponies prioritizing equine welfare and longevity in sport.

0.90 m , 1.0 m , 1.10 m CATEGORIES

Restricted to horses 4-7 years of age with a clear round format, seeing an increase in speed on course only at the 1.10 m level

1.20 m CATEGORY

Restricted to horses 5-7 years with both clear round format and the introduction to jump-off power and speed type classes

1.30 m CATEGORY

Restricted to 6- and 7-year-old horses with jump-off and power and speed type classes only

These classes all have fence height and prize money restrictions for previously jumped classes, rules for how the course should be set, and more.

To read the full details of the proposal, go to the USHJA site and Active Rule Change Proposals.

It is still unclear how these changes will affect the USHJA Young Horse National Championship, first the rule change must be approved by USEF.

WORDS: STEPHANIE JONES

HIGH UP in the North Carolina mountains, there’s a swath of land that was once mined and logged. Today, it’s called Balsam Mountain Preserve, a 4,400acre nature preserve gated community.

About an hour from the bustling showgrounds of Tryon, NC, the laid-back luxury community boasts a collection of amenities, including a gathering house and tavern, a world-class golf course, fitness center, spa, nature center, and a welcoming equestrian community that is all about kicking back and

having fun. The average home on the property boasts 2,500 square feet of living space, with some smaller homes and some larger—up to 6,000 square feet. There are also fractional ownership opportunities for equestrians to spend up to 56 days a year on the property.

Make your way to the equestrian corner of Balsam, and you’ll be greeted by Goose, the barn dog and unofficial mascot, eagerly awaiting the chance to show you around the barn at the equestrian facility. The equestrian center is managed by Goose’s owner and equestrian director, Lila Kilby.

Despite the proximity to Tryon, Balsam’s vibe is decidedly low-key and no pressure, with equestrian activities galore and pristinely maintained barns and fields. The property features 40 miles of old logging trails for endless riding opportunities, and Balsam even has horses available to borrow; and ponies available to give pony rides to kids. The equestrian center includes a riding arena, a 14-stall barn, and plans to expand.

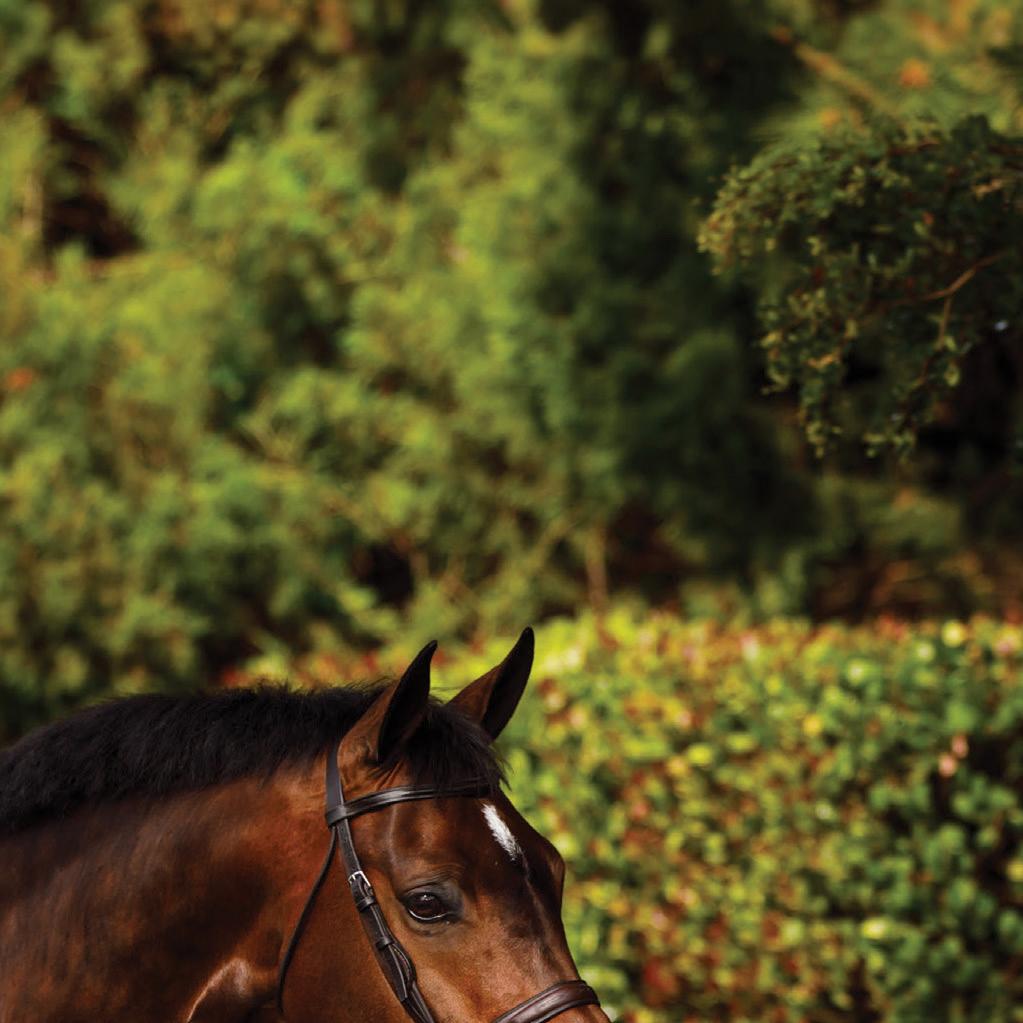

After a horsey photoshoot on the mountain complete with a shower of yellow autumn leaves, Kilby sat down

was never competitive with others. I was just competitive with myself.”

For as long as she can remember, Kilby says she has always loved the combination of horses and the mountains. “In elementary school, we had the classic ‘What do you want to be when you grow up?’ paper. I wrote: ‘I want to live in the mountains and take care of the horses.’

with The Plaid Horse to share more about Balsam.

A Greenville, SC, native, she describes her upbringing as a “total barn rat. I rode horses wherever my mom would drop me off. She would say, ‘Work hard, and maybe they will let you ride a horse.’ I started in a hunter/jumper barn, but I

Kilby had a Quarter horse growing up, Maserati, who “quickly became the love of my life,” she says. “It was just me and my dude, Maserati, out there against the world together.” After her junior year at Clemson University, Kilby’s aunt called her about an immediate opening back home at a barn with 10 boarders on site. She and a friend managed the barn for the summer. When Kilby graduated from Clemson with a degree in Animal Science, she knew she wanted to work with horses from then on.

Balsam developer David Southworth also grew up around horses in the Scottsdale, AZ area. “It was the West’s most western town,” he jokes. “Horses were always around, everywhere. I would walk by horse stables on the way to school every morning.”

Southworth studied hotel administration and was always interested in hospitality, which led to luxury resorts, which led to developing. So, why the North Carolina mountains for this particular development?

“In the early 2000s, I was working on a project with an Arnold Palmer golf course in Scottsdale, and some of the people I worked with were fascinated with this North Carolina Mountain project they kept talking about. Their excitement became my own and I began following the project as well.”

Community manager Sean McLaughlin says that growing up, his parents had about 45 rental homes, which piqued his interest as an adult. After college, he moved to the Adirondacks “and fell in love with the mountains.” Soon after, he moved to New Hampshire and started selling real estate at a ski resort.

And the equestrian corner of Balsam, McLaughlin says, rounds out the special experience that the property provides its residents.

Adds Southworth, “I love everything about the equestrian community and the audience it attracts.”

Everyone comes to the mountains for the fall foliage, but Balsam’s beauty doesn’t fade away with the leaves; A painted beauty and a golden soul, sharing the simple joys of the pasture

Few communities of this caliber offer equestrian programs, and even fewer offer such dedication to its offerings.

• 40+ Miles of maintained trails

• Youth training camps and graduation programs

• Year-round boarding with Daily Equine Care With a brand-new stable in the works, Members can expect...

• State-of-the-art facilities

• Continued investment in equine loved ones

WORDS: MARLEY LIEN-GONZALEZ

DR. BARB Blasko, founder of ShowMD, takes the translation out of treatment. When riders come to her saying that their horse ducked out of a one-stride and they fell right into a standard, or that their back hurts because their horse has an active hind end, she instantly understands. In fact, she might even be in riding clothes herself in the treatment room!

“I’ll watch videos of what happened with patients and know what’s going on. You don’t have to explain to me what chipping in is or leaving long–I know all the lingo!” Blasko tells The Plaid Horse.

In a traditional hospital or physician office setting, white coat-wearing doctors can be intimidating to anyone, not to mention difficult and frustrating in the communication department.

“A lot of times at horse shows when I’m seeing patients, I’m trying to show, too— so I’m there in my breeches and boots, taking care of people, and I think there’s just a different level of comfort. Even if I don’t know them as an individual yet, I know them on an equestrian level, and I think that makes a huge difference.”

MEDICAL SCHOOL

RESIDENT EQUESTRIAN

When Blasko’s peers in medical school saw an abandoned stack of textbooks in the library, they knew she had traded books for boots for a few hours.

“Everyone in my medical school used to laugh at me because I would take a break from studying, go ride, then come back and keep studying,” she recalls. “They all thought I was crazy because even the day before a big test, I’d go ride horses.”

The reason? The same as for many other riders: “When I was in college and medical school, I made it a priority to ride horses because they kept me mentally grounded. They gave me an outlet, it was something I loved to do, and

it really helped me to be able to take my focus off school and on something else.”

Blasko still excelled academically and even managed to lease a horse and ride through residency, the hardest part of a doctor’s life, but she had no idea that she might one day combine her medical profession with her life’s greatest equine passion. If she had known then, she says, “I would have started ShowMD way earlier. That’s my biggest regret.”

Since the organic beginning of ShowMD, Blasko had become known as “the doctor” at the horse show and patching friends up as needed, which snowballed into opening a mobile trailer office on the show grounds to treat all kinds of patients. Since then, Blasko has been expanding not only her business, but equestrian medicine as a whole.

“Probably the most common reason people come in is because they fell off and got injured and need whatever body part examined,” says Blasko. “After about two years of ShowMD, I invested in an X-ray machine because people needed X-rays. It was a big financial investment but worth it because I use my X-ray machine every day. If people come in and they repeatedly ask for a service or

something I don’t have, I feel compelled to try to figure out how I can provide that service.”

That is how ShowMD came to outgrow its original trailer and acquire two mobile offices and a permanent facility at the Desert International Horse Park, complete with IV rooms, treatment rooms, and a lobby. There’s even a pharmacy on-site so patients can go straight from the clinic to pick up their medications.

“It’s like a regular medical office, but I get to walk outside and see horses jumping around, so it’s pretty amazing,” says Blasko.

Understanding the time constraints and scheduling difficulties that come with being an equestrian, ShowMD is a flexible office offering everything from routine healthcare to concierge care and handling emergencies. Some riders in the past have even come in for replenishing IV treatment and then found out their course walk is running early, “So we discontinue the IV and the fluids that are going, and we leave the IV in the person and then they go walk and then they come back and finish,” says Blasko.

“We are athletes, it’s a demanding sport. It’s a lot of physical work, a lot of times we’re outside and face all kinds of

elements,” says Blasko, “ShowMD is multifaceted in terms of getting people feeling better.” If patients need specialty services, like to see a cardiologist or dermatologist, ShowMD arranges those appointments, but in their office, common requests include routine physical examinations, blood work, imaging, MRIs, trigger point injections, ultrasounds, TENS therapy, and even massages.

Riders are not the only patients on Blasko’s chart. “I provide primary care services and coordination of healthcare because a lot of times, trainers work seven days a week and they really just don’t have time to go to the doctor.” Being conveniently located on the horse show grounds means business owners don’t have to miss a day of work or potential customers for their medical needs.

ShowMD looks out for everyone on the showgrounds, especially grooms. “If they get injured by a horse stepping on them, biting them, or something else, there’s a discount I give to the grooms because they work really hard. I groomed for a long time when I was in high school and college to pay expenses, so I know what they do, and it’s a hard job,” says Blasko.

“A lot of them don’t have healthcare insurance. They don’t know where to get care, and sometimes they’re afraid to go to hospitals. A lot of them take horse medication, so part of my job is educating them also on alternatives and where to actually seek medical care,” says Blasko.

“I still work in the ER as an ER doctor, and I see people that are not necessarily documented or don’t have insurance and we care for everybody in the ER and I wanted to bring that to ShowMD.”

To Blasko, the horse community has given her everything so she’s committed to giving back the very best care. Looking into the future, she’s hoping to add a pediatrician to her already impressive team of ‘horse wise’ healthcare professionals and keep expanding operations. Blasko says, “The horse shows have all been so supportive of ShowMD, and the people have been especially wonderful.”

When Blasko sees patients in the ER, they’re often unhappy and bitter about waiting, but when people visit her office at the horse show, they’re impressed with the quality and expanse of care and very appreciative. Says Blasko, “That reaction is what keeps me going and pushes me to reinvest in the business and keep developing different services that I can offer to this community.”

“Barb has been our concierge physician for the past few years. As a rider herself, she totally understands the complexity of our industry and how to best care for us as riders and trainers. ShowMD has helped us navigate the medical system which has become very complex. We are so grateful to know she is always available for us.”

—TRACI AND CARLETON BROOKS, BALMORAL

“Having ShowMD at Desert International Horse Park gives us all a great sense of security knowing there is a board certified Emergency Medicine doctor right on site. Barb treats everyone at the show with the highest level of care and compassion.”

—STEVE HANKIN, PRESIDENT & CEO, DIHP

“Best conversation I’ve ever had with a doctor in my life. She actually listened and actually made sense!”

—MEGAN MCDERMOTT, OWNER, COUNTER BALANCE LLC, WINNER OF MULTIPLE NATIONAL AND FEI GRAND PRIX

WORDS: PAIGE CERULLI

WHEN ANTHONY and Kay Hart founded Hart Trailer LLC in 1968, they did so with the goal of manufacturing the best horse trailers in the industry. Rather than focus on mass-producing trailers, the Harts custom build trailers to meet their customers’ needs and forged meaningful, long-term relationships in the process. It’s that dedication to creating a quality, safe, reliable trailer that sets Hart Trailer apart. It also contributed to the business’ success; Hart Trailer is now owned by the second Hart family generation and will soon celebrate its sixtieth anniversary.

When Anthony and Kay Hart started Hart Trailer, their family was already in the manufacturing business. Anthony and Kay started the company at the same Chickasha, OK, location where it remains today. They began by manufacturing steel trailers, and the trailer designs that the company uses today have evolved from those very first trailers created.

Hart Trailer’s Amanda Williams explains that family involvement and ownership of the company is particularly unique to the company, especially today. “Kay and Anthony had three daughters, and their daughter, Tracy Hart, actually got her start sweeping floors at the shop,” Williams tells The Plaid Horse. When Tracy was a teen, she started working in the front of the company, and in 2010, she purchased Hart Trailer from her parents.

Anthony and Kay were highly passionate about their work and the trailers they produced.

“It wasn’t just a job to them; it wasn’t something they just did 8 to 5 and went home and forgot about,” says Williams. The couple always worked to maintain very strong relationships with customers, employees, and dealers, taking great pride in the quality of the trailers they produced.

Such dedication to quality meant that Anthony and Kay were intensely focused on the details of the business. Anthony mostly focused on the shop and the manufacturing, while Kay handled more of the business operations. Williams describes them both as being incredibly focused on the details, to the business’ benefit. “They did not do anything that wasn’t done properly,” she says. “Neither were people who would take a shortcut.” Tracy inherited those qualities and has continued to run the business with the same focus. “We don’t do anything that’s not as close to perfect as can be,” says Williams. “There’s a focus and drive of trying to make sure that we’re always improving and not taking shortcuts.”

Williams recalls one day early in her employment when she and Tracy were walking through the trailers. One trailer’s Hart Trailer decal had been applied slightly crooked, and Tracy immediately got an employee to remove it and correct it. “From the little details all the way down to the welds, she and Roy go over everything,” says Williams. “There’s not a trailer that leaves that they haven’t put eyes on.”

When customers call the company with questions, they get a sense of the company’s dedication. Hart Trailer employees directly interact with customers regularly, and when customers call in, they speak with a live person. Hart Trailer employees often become friends with customers, such as when the company repeatedly sponsors shows and organizations.

Many Hart Trailer employees are horse people, and they understand the importance of trailer safety and quality. Williams has a particularly unique perspective, since her parents professionally transported horses all over the United States and Canada. “I grew up with the opportunity to pull several different brands,” she says. “The way that [Hart Trailer] pull, you don’t know that they’re there. They are heavier-made and very structurally sound, but you don’t feel them behind your truck when you’re hauling down the road.”

Hart Trailer uses an axel placement formula that’s unique to the company. The trailers are built to not only last for

decades, but to also maximize safety in case of an accident.

“I’ll never forget when I first started, a mini trailer was at a stoplight and a semi ran into the back,” says Williams. The trailer sustained minimal damage, and once one corner post, the back doors, and ramp were replaced, it was road-worthy again. “I was in awe at how well the trailer held up.”

Such durability means that many older Hart Trailers are still on the road today. When Williams first started working with Hart Trailer 13 years ago, she worked in the parts department. She often got calls from trailer owners looking for parts for trailers that were decades old: “We have trailer on the road from the nineties, eighties, and on rare occasions, the seventies.”

Often, Hart Trailers are passed down from one generation to another. To support those younger generations of trailer drivers, Hart Trailer has launched a new scholarship initiative. “It’s an avenue for us to give back to some of the families,” says Williams. “These are all students involved in livestock or equestrian or rodeo, and their families own and pull a Hart Trailer.”

Scholarship candidates must complete an application and will undergo an interview process. Scholarship recipients will receive not only scholarship funds, apparel, prizes, and service opportunities for their trailers, but will also publicly represent Hart Trailer.

During its time in business, Hart Trailer has evolved from manufacturing steel trailers to manufacturing a wide range of aluminum trailers. Today, the company manufactures slant as well as straight load trailers.

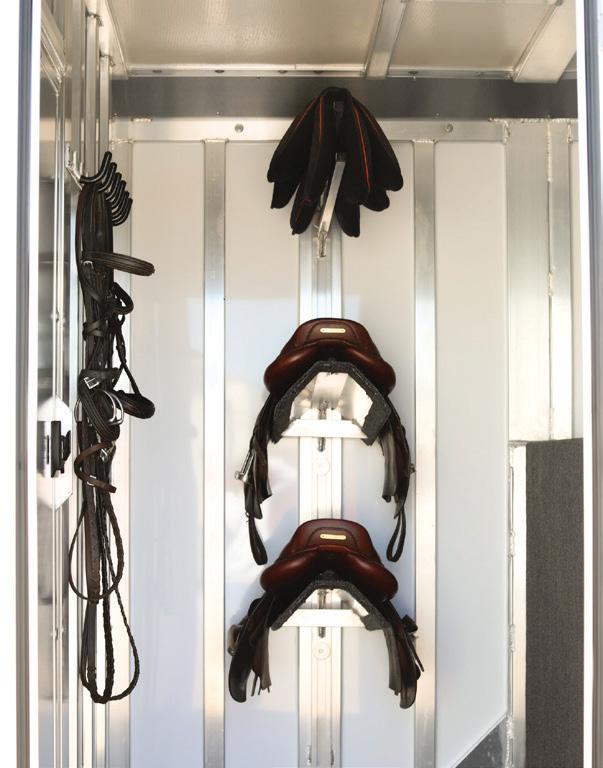

The straight load trailers are designed with larger horses in mind, such as jumpers and dressage horses. The straight loads are taller than the slant loads, and Hart Trailer even manufactures straight loads suitable for draft horses.

Hart Trailer doesn’t use sheeted floors. Instead, they use tongue and groove interlocking floors that won’t give when you walk on them. “These floors make our trailers incredibly strong,” Williams says.

The trailers feature a half-inch fiberglass composite roof, which helps with keep horses warmer or cooler depending on your climate.

All Hart Trailers are unique, and the company builds them custom. “We don’t have a cookie cutter or packaged trailer,” Williams explains. The width, height, and length can be customized on all but one model, which is limited only by width, and there are also several different tack options and configurations available. Additionally, with over 21 different sheet colors available, there are plenty of ways to make a Hart Trailer your own. “We don’t build two trailers alike,” says Williams.

While Hart Trailer is located in Oklahoma, you can find the trailers at dealers throughout the United States and Canada. In addition to choosing from stock trailers available at dealers, customers can place their own custom trailer order through a dealer. Customers are also welcome to visit Hart Trailer and see the extensive attention to detail and pride that goes into each trailer’s build.

As Hart Trailer nears its sixtieth anniversary, the company sets its sights on the future. “We’re always trying to stay on the front edge of innovation,” adds Williams. “How can we do things better? You don’t want to fix something that’s not broken, but you always want to be striving to do something better than before.”

That dedication to providing top-quality trailers designed specifically for horse owners is integral to the business’ success. Customers recognize that quality and keep coming back. “We have customers that are on their sixth trailer,” says Williams. In some cases, trailers are passed down from customers to their kids and, eventually, their grandkids. It’s a fitting achievement for a company that’s built upon the importance of family and the value of a top-quality product designed to last.

GASTRIC HEALTH is always a hot topic among equestrians. Equine Elixirs ushered in the New Year with a new liquid gastric supplement that has garnered a lot of attention. Slimer, an all natural way to coat the sensitive gastric lining from splashing acid, is the newest addition to Equine Elixirs’ exclusively show safe supplement lineup. “An easyto-administer liquid alternative to sucralfate is something we have been working on for a while,” said Elizabeth Ehrlich, the founder of Equine Elixirs. “We introduced Slimer at the AAEP this year in Orlando, and the veterinarians we spoke with were extremely impressed with its application.”

ALL ABOUT SLIMER

Slimer gets its name from the ‘slimey’ nature of its ingredients: hyaluronic acid, beta glucan, slippery elm, marshmallow root, and licorice root. This combination of ingredients not only provides mucosal soothing properties, but it helps shield the stomach lining from irritation. Slimer’s viscous nature forms a protective coating over the stomach’s squamous and glandular surface, and protects the

sensitive gastric tissue from splashing acid for 1-2 hours at a time. Slimer can be added to feed or can be dosed strategically before riding, traveling, competing, or times of additional stress. “There are several liquid gastric supplements available that contain lower levels of hyaluronic acid and beta glucan,” said Ehrlich. “One of the things that really sets Slimer apart from the rest, is the higher concentration of high molecular

weight hyaluronic acid and beta glucan, in addition to its other anti-inflammatory ingredients, which makes it a broader spectrum and more effective product.”

Sucralfate is a common medication used to treat ulcers and coat ulcerative tissue for several hours at a time, but often presents a management issue. For maximum effectiveness, it is fed on an empty stomach, typically 3-4 times daily in order to maintain its protective barrier. One of sucralfate’s drawbacks is that it can interfere with the absorption of other medications. Unlike sucralfate, which adheres to ulcerative tissue only, Slimer will coat healthy stomach tissue as well, providing a broad layer of protection throughout the squamous and glandular region, but for a shorter period of time. Slimer can be given before riding, traveling, or during times of additional stress, but can also be fed daily as part of a regular gastric maintenance program, and will not interfere with the absorption of medications. According to Vivian Yowan, rider and head trainer at Saddle Ridge, LLC, “Slimer has completely replaced the sucralfate that one of my nervous horses previously needed before competing.”

all-natural, show safe ingredients:

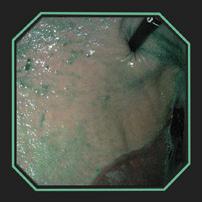

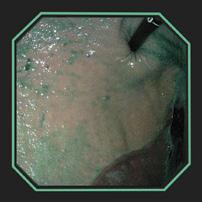

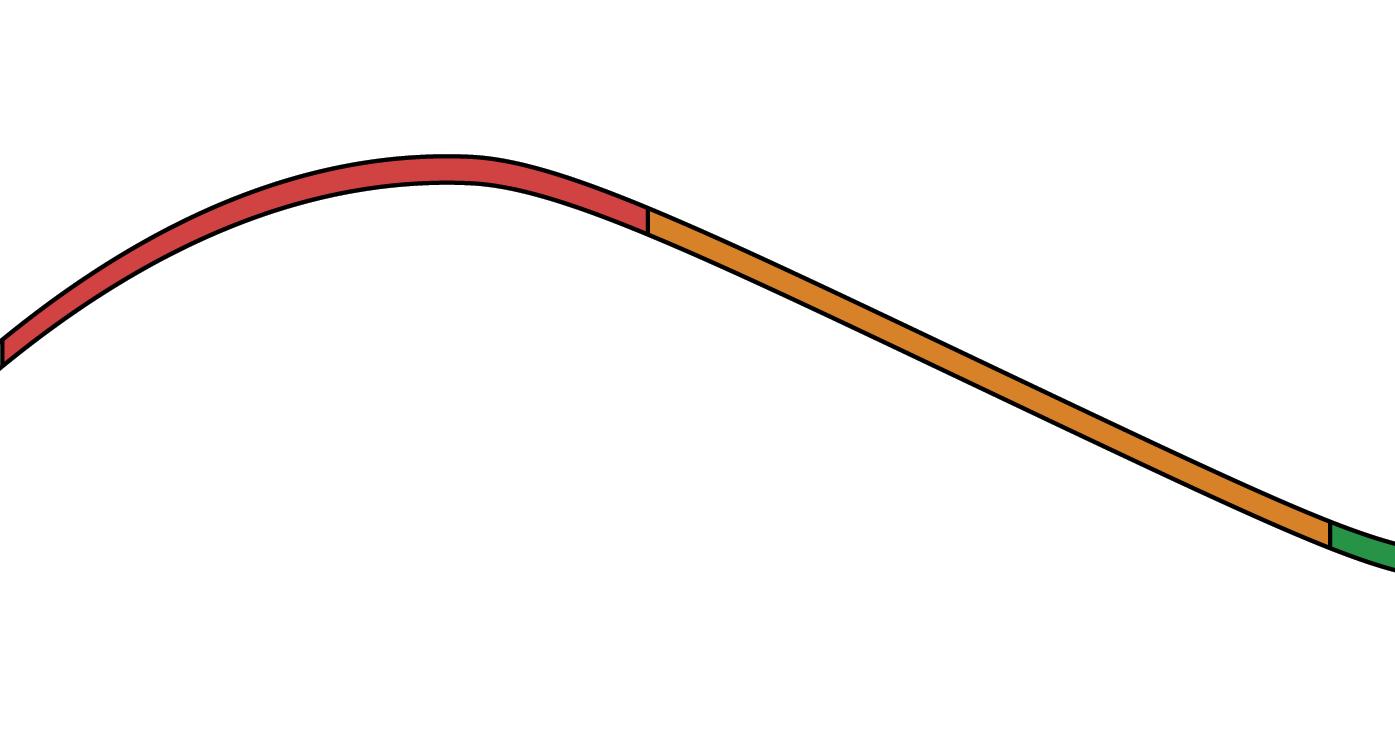

VISUALIZING SLIMER AT WORK

DISTRIBUTION OF SLIMER THROUGHOUT SQUAMOUS AND GLANDULAR REGIONS

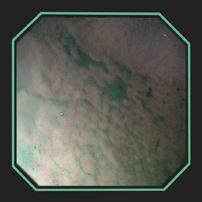

DISTRIBUTION OF SLIMER (without color dye) SHOWING PRODUCT GRANULARITY

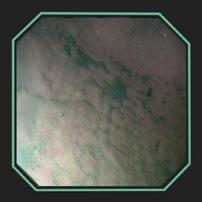

The above gastroscopy images show Slimer coating the stomach. The horses received 2oz of Slimer via syringe and then lunged at the walk and trot for 10-15 minutes to simulate splashing acid while being ridden. Though Slimer is brown, it was initially dyed blue to be more visible. In order to show that the blue dye did not discolor the stomach or disassociate from Slimer, over 90cc of water was inserted through the gastroscope to “rinse” a portion showing that the underlying tissue remained pink.

There is no shortage of riders and trainers already singing Slimer’s praises. “Slimer has been a game-changer for us,” said Lauren Crooks of Crooks Show Jumping. “I’ve seen a noticeable improvement in my horses’ comfort, focus and overall demeanor during competitions as well as at home. It’s clear that Slimer helps promote a healthy stomach environment and preserve the gastric tissue even in high-pressure environments.” Mary Ann Thomas, trainer at Ashwood Farm, said that she has “seen less reactivity under saddle and in the barn” for those specific horses she knows to have had ulcer issues.

GET TO KNOW SLIMER WITH SOME FAQS

How is Slimer di erent from Ulceraser and can they be used together?

Ulceraser is forage based, designed to increase the strength of gastric mucosa, increase circulation and help heal lesions, act as a sand clear, and encourages

DEMARCATION AREA RINSED WITH WATER HIGHLIGHTING SLIMER’S GRANULARITY

DISTRIBUTION OF SLIMER (without color dye) THROUGHOUT SQUAMOUS AND GLANDULAR REGIONS

“I’ve seen a noticeable improvement in my horses’ comfort, focus, and overall demeanor during competitions as well as at home. It’s clear that Slimer helps promote a healthy stomach environment and preserve the gastric tissue even in high-pressure environments.”

—LAUREN CROOKS, CROOKS SHOW JUMPING

digestion in the foregut rather than the hindgut to help prevent the release of volatile fatty acids that can contribute to hindgut ulcers. Slimer’s viscous nature is designed to coat the squamous and glandular portions of the stomach to help protect the sensitive mucosa from splashing gastric acid during times that horses are most at risk for ulcers. Both supplements are designed to be used together and compliment one another.

If Slimer has hyaluronic acid does that mean it’s also bene cial for joints? Yes! Slimer has more high molecular weight hyaluronic acid than most other joint supplements and it will benefit your horse’s joints. The reason Slimer isn’t marketed as a joint supplement is because it is not a ‘complete’ soft tissue support

supplement like Arthroscope, which also contains the traditional building blocks of joint health in addition to other potent anti-inflammatories.

How is Slimer di erent from omeprazole?

Omeprazole is a drug designed to completely eliminate the production of gastric acid. Slimer is all-natural and will create a temporary slime coating throughout the stomach, but does not eliminate the production of gastric acid, and will not interfere with normal digestion.

Slimer is a great addition for any horse that needs extra gastric protection before riding, traveling, or competing. With its all-natural, show-safe formula, Slimer is easy to administer and an effective way to keep your horses feeling their best.

WORDS: PHILIP RICHTER, ALAN BAZAAR, AND CAROLYN YUN OF HOLLOW BROOK WEALTH MANAGEMENT

OWNING AND MAINTAINING horses has never been a bargain proposition. More recently, equestrian world costs have skyrocketed. Hay, shavings, shoeing, vet bills, and entry fees have all escalated and continue to rise.

Despite soaring prices, we are all still drawn to the beauty of the horse and all the enjoyment and benefits they bring us. From Thoroughbred racing to show jumping to dressage, horses provide value that money cannot buy. Unlike some other sports, equestrian pursuits require significant, ongoing financial commitment.

Whether you are a seasoned horse owner, a parent with a child venturing into the sport, or a professional running an equestrian business, managing the costs associated with horse ownership and activities is essential for long-term financial wellness. As wealth managers with many equestrian clients, we find it incredibly important to explore and implement basic strategies to maintain financial integrity and family wellness while pursuing your equestrian dreams.

IDENTIFYING THE PURPOSE AND GOALS OF HORSE ACTIVITIES

Before delving into the financial aspects, it is vital to clarify the purpose and goals of your involvement in the equestrian world. This self-reflection

will guide your spending decisions and ensure they align with your core values and long-term objectives. Key questions to consider:

Is this a recreational activity for a few years, such as a child’s introduction to horseback riding, or is the goal to compete at higher levels? Recreational riding generally requires less financial investment than competitive pursuits, which can include training, show fees, travel, and high-end equipment.

Are you involved in horses purely for enjoyment, or is there a business component, such as breeding, training, or running a boarding facility? If it is a business, understanding your cost structure and profitability is critical. Additionally, the tax implications differ significantly between hobbies and businesses:

• Hobby: Expenses related to horse ownership as a hobby are generally not tax-deductible. You may, however, deduct certain costs up to the amount of income generated from the hobby (e.g., occasional prize winnings or small sales).

• Business: If you operate as a business, you may be able to deduct

expenses related to your horse activities, such as feed, boarding, training, travel, and equipment, provided you can demonstrate a profit motive. The IRS uses specific criteria to determine if an activity qualifies as a business, such as consistent efforts to generate income, keeping detailed records, and showing a profit in at least three of the last five years.

For families with children, it’s important to gauge whether the child’s interest is likely to wane after a few years or if this could evolve into a lifelong passion. For adults, consider whether this is a phase or a permanent lifestyle.

Answering these questions will help you define your equestrian involvement and provide clarity when allocating resources.

Equestrian activities can quickly become a source of financial strain without clear boundaries and defined decision-making processes. In our experience as wealth managers with equestrian clients, it is clear how divisive and isolating the dynamic can be—specifically with multiple generations of riders and large sibling groups with different interests.

B o a r d i n g & D a y S c h o o l f o r

G i r l s i n G r a d e s 8 - 1 2 s d -

E q u i n e S c i e n c e

G r o o m i n g f o r S u c c e s s

I n t e r n s h i p O p p o r t u n i t i e s

H i s t o r y o f H o r s e i n S p o r t

S t a b l e & H o r s e S h o w M g m t

E q u i n e / S m a l l B u s i n e s s M a t h

E q u i n e N u t r i t i o n & W e l l n e s s

E q u i n e A n a t o m y & P h y s i o l o g y

O l d f i e l d s S c h o o l . o r g

E Q U I N E S C I E N C E C O N C E N T R A T I O N

Whether you are a seasoned horse owner, a parent with a child venturing into the sport, or a professional running an equestrian business, managing the costs associated with horse ownership and activities is essential for longterm financial wellness.

It is not only about where parents of families spend their money; where they spend their time also impacts family wellness. We often recommend large equestrian families to engage in a family governance program to work it all out together. Whether it is casual and hosted by our firm, or co-hosted with professional consultants, it is key to all be on the same page. A system of family governance ensures that all stakeholders are on the same page and that financial decisions are made responsibly. Steps to consider establishing effective governance:

1 Set a Budget

Begin by determining how much you can realistically afford to spend on horse-related activities without jeopardizing other financial goals, such as retirement savings, education funds, or emergency reserves. Break the budget down into categories such as lessons, equipment, boarding, and competition fees.

2 Define Spending Parameters

Establish rules for spending. For example, decide in advance what level of competition you are willing to fund or how much you would spend on a horse purchase. This helps avoid emotional, spur-of-the-moment decisions that can derail finances.

3 Clarify Roles and Authority

Determine who has the authority to make financial decisions related to horse activities. For instance, parents might agree that one parent manages day-to-day expenses, while major purchases require joint approval. If multiple family members are involved, such as siblings, ensure everyone’s needs and priorities are considered.

Financial circumstances and goals can change over time. Schedule regular check-ins to review spending, assess whether you are staying within budget, and make adjustments as needed. This is particularly important for families with children, as their interests and skill levels may evolve.

Transparent communication is key to avoiding misunderstandings. Make sure everyone involved understands the financial constraints and goals. For example, explain to children why certain expenses, like a new saddle, additional lessons, or seeing a sports psychologist may or may not fit within the budget.

Horses have a unique way of capturing hearts and inspiring dreams, but they also come with significant financial responsibilities. Striking a balance between passion and practicality is essential.

• Consider Alternatives: If the costs of purchasing a horse are prohibitive, explore alternatives such as leasing or participating in riding programs.

• Plan for Contingencies: Unexpected expenses, such as veterinary emergencies or equipment replacement, can arise. Build a financial cushion to cover these costs without undue stress.

• Educate Yourself: Take the time to learn about the financial aspects of horse ownership, including insurance, tax implications, and ways to reduce costs.

The equestrian world offers unparalleled joy and fulfillment, but it is essential to approach it with a clear financial strategy. By identifying the purpose and goals of your horse-related activities and creating a system of family governance, you can ensure that your equestrian journey remains both sustainable and enjoyable. You can work towards these goals with support from your financial advisor, accountant, estate attorney, business attorney, family therapist—amongst other service professionals. With thoughtful planning and open communication, you can pursue your passion for horses while maintaining financial wellness for the entire family.

PHOTO GALLERY

JAN. 12, 2025 • BRUCETON MILLS, WV

PHOTOS: SHEILAJPHOTOGRAPHY

“With a deep passion for equine sports, countryside landscapes, and intimate moments between horse and rider, I seek to tell the stories that words often cannot,” photographer Sheila Jenkins tells The Plaid Horse. “I love to bring out the personality and energy of horses, creating timeless images that resonate with viewers and evoke a sense of wonder.” In January, she photographed Karrie Stithem on Tyree’s Classy Hombre (top and bottom left), and Kinley Manko (bottom left, in front) on Blade.

2025 Tryon Welcome & Spring Series Preview 27-Jun t

Welcome 1 - National / Level 3 - March 20-23

Welcome 2 - National / Level 3 - March 27-30

Welcome 3 - National / Level 3 - April 3-6

Welcome 4 - National / Level 3 - April 10-13

Spring 1 - Premier / Level 6 - April 30-May 4

Spring 2 - National / Level 4 - May 7-11

EE Spring 3 - Premier / Level 4 - May 14-18

Spring 4 - National / Level 5 / CSI 2* - May 21-25

Spring 5 - National / Level 6 / CSI 3* - May 27-June 1

Spring 6 - Premier / Level 5 / CSI 2* - June 3-8

Spring FEI levels TBA at a later date. All levels subject to change.

WORDS: JUMP MEDIA

HITS HORSE shows have undergone a stunning reinvention over the past two years. Wordley Martin has been a crucial partner in the process, leading the renovation of riding arenas at the HITS Post Time Farm in Ocala, FL, and at HITS Hudson Valley in Saugerties, NY.

With two-phase renovations at both venues, Wordley Martin has installed more than 942,000 square feet (or 21.6 acres) of footing to renew 18 competition and schooling arenas. Wordley Martin is a leading developer

of equestrian properties and premier riding surfaces, offering full-service bespoke equestrian facility planning.

In addition to new grading, underbase, footing, and irrigation, the founding partners of Wordley Martin— Sharn Wordley and Craig Martin— helped the HITS team create a new look for both venues. That work included raised berms, fencing, landscaping, design, and layout, and most crucially, they also oversee the maintenance of the arenas as part of a multi-year partnership to ensure the quality and safety of the footing is upheld following installation. In Ocala, Wordley Martin also had an arborist trim the mature live oak trees throughout the property, safeguarding the special atmosphere of North Central Florida.

“Our crew pre-blended 6,000 tons of footing in conjunction with building the arena, completing the whole project in an amazing 24 days,” says Craig Martin of the most recent renovation in Ocala, which was completed in December 2024. “It was a great team effort by all of the crew plus our office staff managing the logistics. We are grateful to the HITS team for their help and support.”

HITS

Read on to learn more from HITS Chief Customer Officer, Joe Norick, about his perspective on the mutually beneficial partnership with Wordley Martin:

1. Why did you choose Wordley Martin to renovate HITS Ocala, even though they weren’t known for horse show footing?

It was an easy decision to partner with Wordley Martin. I’ve known Sharn Wordley and Craig Martin for many years. I’ve seen their product firsthand, and we discussed it both from a professional point of view as a horseman, and as a horse show operator. They felt confident they could deliver the highest quality but also be able to handle commercial use.

2. What sets Wordley Martin apart as a commercial partner?

One of the things I find really interesting about Craig and Sharn is that both of them ride and show horses at a high level, so they understand how it should feel when the hoof touches a surface and what is best for the horse’s comfort and safety on the footing. They look to deliver that feeling of security for horse and rider

across the board on a commercial scale, which not everybody can do.

3. Why did you decide to make one giant, flexible space instead of separated arenas at HITS Ocala?

Personally, I am a fan of very large arena spaces that can be separated to create the best possible size arenas for competition. Utilizing a massive space like the six acres we developed this way worked perfectly for the HITS Post Time Farm property and created the flow that we wanted to achieve.

4. What is your favorite part about working with Sharn, Craig, and their team?

One of my favorite things about Sharn is he always returns my phone call or answers the phone! Craig comes up to Ocala and Saugerties regularly to make sure everything is going smoothly, and their office keeps all of the moving parts organized.

5. What sort of feedback have you gotten from riders and trainers about the new rings at HITS Post Time Farm? The success of the new competition area design has been overwhelming. The

trainers, the riders, and even other horse show professionals have all looked at it and said, “Wow, this makes sense.” It puts HITS Post Time Farm where it needs to be for today’s horsemen and horse professionals.

6. How does Wordley Martin’s long-term maintenance approach benefit HITS?

One of the main reasons we chose Wordley Martin is that they agreed to sign multi-year agreements to help us maintain the footing year-round. If someone says to me, “There’s a problem,” Sharn and Craig are always there to answer any questions.

7. What are future plans for HITS venues in partnership with Wordley Martin?

As we expand into other venues, I always consult with Sharn and Craig about what they think we should do for the footing and what they recommend as the correct mix. Wordley Martin is, without a doubt, our primary strategic partner, especially on the East Coast. From a show organizer’s perspective, nobody is more qualified to advise on these critical issues, and we look forward to continuing to benefit from Wordley Martin’s expertise.

As Grand Prix-level riders, Wordley Martin co-owners Sharn Wordley and Craig Martin fundamentally understand the requirements for a modern equestrian sports venue. They have used their extensive experience and knowledge to design and install hundreds of arenas, including for Olympians, with their world-class surfaces. Wordley Martin is more than just a footing installer, helping clients through every stage of the process of realizing their dream facility, from the initial designs, through site work, construction, and maintenance. They help clients map out and build full facilities and work as part of the Equine Design and Development Collective (EDDC) to provide a variety of additional services for equestrians and their farms. Learn more at www.WordleyMartin.com.

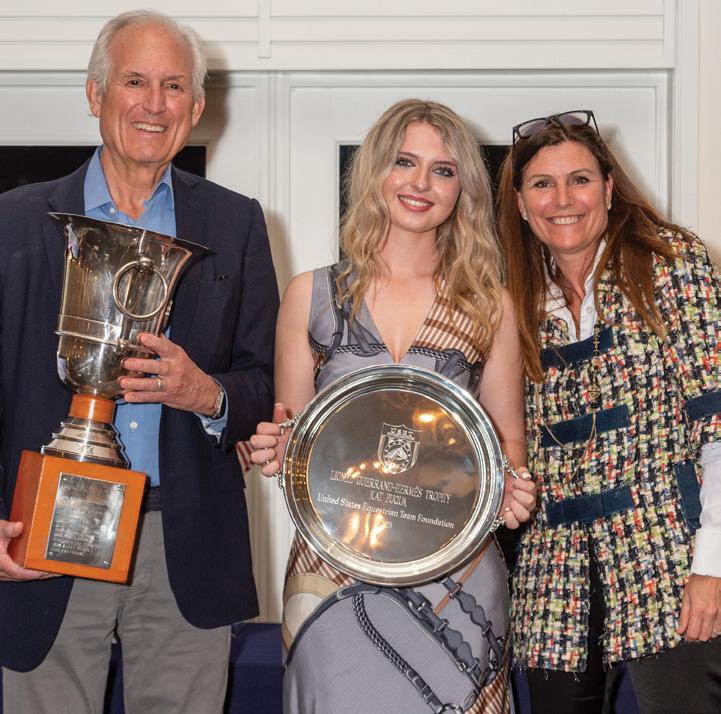

JANUARY 17, 2025 • THE WANDERERS

1 Kristi Mitchem along with John and Beezie Madden and USET Foundation

Trustee Angela Vogel • 2 Kat Fuqua is presented with the Lionel Guerrand-Hermès Trophy by USET Foundation Chairman W. James McNerney, Jr. and USET Foundation President and CEO Kristi Mitchem • 3 Rebecca Hart (right) and Paralympic owner Rowan O’Riley

PHOTOS: JUMP MEDIA

COLUMN

APPLIANCE TO ART

Barefoot horses: An appliance for soundness.

Post-circuit WEF. Why are you still there?

When we encounter art, or “the unexpected inevitable,” as Elizabeth Gilbert defines it, we might wonder: How did I get so lucky? This is what takes your breath away, allows contemplation, and inspires awe. On the other hand, there’s a lot of life that is pure appliance: Expected, hardware, completely unimagined.

This is your new monthly equine pop culture contribution—think: Where The Onion meets The New Yorker—to rate what we’re seeing out there, from Appliance to Art. Take it with a grain of salt and a hearty sense of humor. For the love of all things horse, don’t @ us. Have an idea for an entry? Email us at editor@theplaidhorse.com and we might include it in our next column.

Obligatory (and necessary) spring vaccinations & dentals.

Showing your Connemara pony “Potato Chip” on St. Patty’s

Awkwardly sweaty lessons (not hot, not cold, but real hot when you work out).

Bra horse hair buildup after “light grooming.” We know, it’s so itchy.

“Mud art” that shows up on your boots, girth, and beyond.

“Mental health is wealth.” Courtesy of WIHS “Kind Wins” campaign.

The US Equestrian Open Jumping Final being added to the Wellington International for Rolex Season Finale.

Spending spring break at a winter circuit.

“We Built a Community—A Family”

I BEGAN MY JOURNEY in the horse world at just ve years old, back when you could “rent” a horse and go for a trail ride without having to sign your life away or pay an arm and a leg. It was a time when horse rentals were common, riding schools thrived, and owning a horse was more accessible to the average person. My parents had no interest in horses—until I made them, much like many junior riders do today. It was my grandad who took me on my rst trail ride, and from that moment, the rest was history.

As I grew, my parents supported my passion by enrolling me in lessons, leasing horses, and eventually helping me own my rst horse. I trained, showed, and competed in dressage, immersing myself in every aspect of the sport. By the time I was old enough to work in a barn, I was eager to do anything— cleaning water troughs, feeding horses, mucking stalls, and grooming. My dedication eventually led to a full-time grooming job for a friend who had been my trainer since I was six.

When I started college, I was also working full-time as a groom, knowing that I wanted to become a trainer. I quickly realized that to support myself nancially, I would need to make some adjustments. At 20, I didn’t have a concrete business plan, but I knew I had to build something that attracted more than

just the ultra-wealthy clientele who could a ord expensive horses and high-end training. I was young, and while I had a solid junior career, that alone wouldn’t be enough to draw clients. Establishing myself as a new, young trainer was going to take time and e ort.

Above all, I have always simply loved horses. Even now, nearly 13 years later, you’ll still nd me at the barn a er a long work week, tinkering around just because I love it. When I rst started planning my business, I wanted to create that same experience for others—not just for competitive riders but for everyday people who shared my passion. Initially, my program was geared toward children, o ering them a place to chase their horse dreams, just as I had. I wanted parents to have the opportunity to give their kids a taste of what I was lucky enough to experience.

What began with one horse—generously purchased by my parents to help me get started—has grown into a thriving program. Today, we have more than 15 horses and over 85 riders each week, welcoming both children and adults.

What we have now is so much more than I ever could have imagined. We’ve built a community—a family. We have entire families who ride together, grandparents riding alongside their grandkids. Billings Equestrian has

become a home for so many riders, and I feel honored to be a part of their lives. My horses have helped not only me but also so many others through some of the hardest times in their lives, creating a space where dreams truly come true.

While this journey has been incredible, it hasn’t been without challenges. The growth we experienced during COVID was both exciting and overwhelming, bringing steep learning curves. I made mistakes, and they came at a cost. With rising prices and in ation impacting everything horse-related, there were moments when I thought I might have to close my doors. I questioned what I was doing during those times, but the thought of my clients—who have become friends—not having a place to ride, and the idea of losing my horses, the best coworkers anyone could ask for, made giving up simply not an option.

Though I haven’t been able to keep prices as low as I’d like due to these challenges, I’ve still been able to create a space where people can ride once a week and return another additional day each week to learn about horsemanship. We’ve built a place where people can truly learn to care for horses.

What’s even more exciting is how our riding school has evolved. Over the years, we’ve built a group of riders

who have gone on to buy their own horses and now train and compete in my dressage program. What started as a small riding school has grown into a thriving equestrian program and a full-time dressage training barn—more than my ve-year-old self could have ever dreamed.

I don’t know what the horse industry will look like in the next ten years, but I do know that transforming a riding school into a riding community has been possible through hard work, resilience, and adaptability. I can’t imagine a world where we don’t get to see a little girl’s eyes light up the rst time she sits on a pony or where an adult can’t nally ful ll their childhood dream of learning to ride. If riding schools disappear entirely, I worry that our sport will eventually fade—and, even worse, that people will lose the chance to have their lives changed in incredible ways by the horses themselves. Keeping this business strong and accessible has required continuous learning, adaptation, and innovation. Over the years, I’ve worked with a business coach and consulted with experts in building riding programs to re ne my approach and ensure long-term sustainability. I’ve adjusted my pricing model multiple times, always with the goal of making riding accessible to the largest possible demographic. This

“I can’t imagine a world where we don’t get to see a little girl’s eyes light up the first time she sits on a pony or where an adult can’t finally fulfill their childhood dream of learning to ride.”

—SAMANTHA BILLINGS

has not only strengthened my business but also helped create a more diverse community of riders—something the sport desperately needs.

To stay current and keep my program thriving, I attend conferences and seminars, always looking for ways to improve and adapt. One of the biggest shi s I made was designing a pricing model similar to a gym or dance school membership. Since this structure is familiar to many families, it makes it easier for newcomers to give riding a try. I also developed a structured curriculum with a dashboard that allows parents to see exactly what their children are learning. Parents today have countless sports and activities to choose from— soccer, gymnastics, swimming—and they want to feel con dent that their money is being well spent. By providing clear structure and measurable progress, I’ve helped parents feel comfortable

choosing horseback riding as their child’s sport.

Like any business, marketing and promotion are essential. I run promotions and have a structured advertising plan to attract new students while keeping longterm clients engaged. Client retention is something I care deeply about, and it shows—many of my riders have been with me for over ten years. That kind of stability creates a welcoming, loyal community where new clients quickly realize they’ve found a solid, established place to ride.

The only way to keep any business going is to seek out advice, embrace continuing education, and adapt to changing times. If the equestrian industry wants to remain robust and accessible, it must constantly evolve to stay relevant— especially to parents, who are the ones choosing their child’s sport in those early years. I’m committed to doing my part to ensure that horseback riding remains a viable, enriching option for future generations. This is why, no matter what obstacles come my way, I will always do my best to provide a place where children and adults alike can experience the joy, ful llment, and transformation that comes with a life enriched by horses.

Billings Equestrian is owned & operated by USDF Gold Medalist, Samantha Billings. Learn more at www.billings-equestrian.com.

WORDS: DANA ZITER

I MET Heidi Boggini in early Spring of 2015. A mutual friend, Kathy, connected us a er I had shared with her that I was looking to move my gelding, Rod, closer to home. Prior to reaching out to Heidi to inquire about boarding, I asked Kathy how it was to be a boarder at La Fazenda and she simply said, “Heidi treats all of the horses like they are her own.” Little did I know the depth of that insight at the time, but while pulling down the driveway for an initial meeting with Heidi, I quickly knew the farm was a special place, and also, that I probably couldn’t a ord to board there.

It was a blustery March day, and the paddocks had begun their annual winter thaw. In most cases this typically means a sloshy mix of ice, snow, mud, and poop. But there was not a manure pile in sight! This was due to the very rst image I have of Heidi, driving a Gator through the slush, with a dump bed full of manure and her faithful cattle dog, Joe, trailing close behind. I soon learned the extent Heidi took to keep the property pristine, in which she told me, “The horses give us so much, they deserve the respect of a clean and healthy environment.”

A er working out an arrangement where I would help with feeding and mucking a few days a week to reduce my board cost, Rod was slated to move in for April. Upon arrival, Rod settled immediately into the herd consisting of four other horses: Whitney, Scooter, Abba, and Henry. Whitney and Scooter were Heidi’s and Abba and Henry were other boarders’ horses. Abba moved on to a di erent barn shortly a er our arrival, but Henry’s owner Abigail was planning to stay put, as Henry, a sensitive TB gelding, was thriving at La Fazenda. This was due to the primary reason that drove my desire to board Rod there as well, as Heidi believed strongly in “natural” horse-keeping. While she had a beautiful barn, the horses were outside 24/7 with unlimited forage and abundant space to be horses.

THE TURNING POINT

It was within this timeframe that an unsurmountable heartbreak was headed full-bore for Heidi, her family, and friends. One sunny a ernoon in 2018, Heidi and I were enjoying the “golden hour” in the barn. This was a special time, late in the day when the sun would shine through the back door of the barn, casting a warm golden glow on the aisle. Heidi was texting someone and looked up at me and asked, “How do you spell apple? I am having a brain-fart!” We laughed out loud and I aided in spelling so she could send her text. A few months later, she shared with Abigail that she was having trouble when reading her favorite publication, Eclectic Horseman. This was also accompanied by random scenarios where she struggled with ne motor skills, such as screwing in the plug to the water trough or untying the hay net knots. Her husband, Glen, and mother-in-law, Jane, began aiding Heidi in pursuing medical advice for these new struggles. Eventually, this led to testing and conferring with top doctors at Brigham Women’s Hospital in Boston, MA.

On an August evening in 2019, I arrived at the barn to nd Heidi feeding the horses at a later time than usual. As I entered the paddock, she was visibly upset and when she locked eyes with me tears started to ow down her face. I was aware she had been at Brigham that a ernoon and before I could muster the

words to ask how the appointment went, she said, “They fuckin’ told me I have Alzheimer’s.” Heidi had just turned 60 in June. She has two vibrant sons in their early 20s, Max and Owen, and a family who has already experienced great loss. She had a young horse she planned to ride into her golden years with and a farm that embodied her soul. This could not be happening. But it was, and there were two options for people in her life—abort a relationship and create distance, or hang-on for the ride and support Heidi as she progressed through this awful, terminal disease.

One thing Abigail and I quickly learned about early-onset Alzheimer’s is that the person a ected can spiral into micromanagement of the ones around them, as its their way to gain a sense of external control since they are losing internal control. This made for a challenging environment at times, with some days Heidi not permitting us to groom our muddy horses inside the barn or being very particular about where items were placed. In November 2020, I reached the point where La Fazenda, my sanctuary, had become less than peaceful and felt it was time to move Rod to a new boarding location. When I told Heidi, she cried, and it felt awful. I felt like I was abandoning the ship, but the decision was made. Abigail remained steadfast at the farm with Henry, enduring Heidi’s mood swings and forgetfulness while helping her with farm chores and horse care. The entire six months I was gone, it just didn’t feel right. I made amazing new friends and enjoyed a peaceful boarding environment, but I felt a deep sense of guilt that I had deserted a friend in need. While I had continued to visit Heidi and Abigail during that time and assist how I could, it was in June Abigail shared with Glen (who had always been hands-o when it came to the horses) and myself how di cult it was becoming to manage Heidi in terms of horse care and safety. Glen shared his desire to support an environment in which Heidi could remain involved with her horses as long as possible and it became Abigail’s and my mission to ensure we would make that happen. I moved Rod back to the farm that month and we embarked on the most emotionally heart-wrenching journey I have had to date.

As the months progressed, Heidi’s cognitive condition worsened, and it was taxing for Abigail and myself to manage her safety and keep the farm running while holding full-time jobs. Thankfully, we had some assistance along the way. Cara, who lives in a rental house on the farm, helped Heidi with chores for many months. Not having much prior experience, she soon became an honorary horse person. We were also fortunate to have important help from two horse-savvy college students, rst Emilie and, when she graduated, Madi. The horse care routine became Heidi’s sole daily focus, replacing her rapidly diminishing social life outside the farm. As this intensi ed, so did the challenges for those of us aiding her. She was insistent on driving the Gator while mucking but was quickly losing the ability to safely operate the machine—o en driving into things and having many close calls with horses and people. Mucking itself also became an obsession, maybe from her deep-rooted belief in keeping a clean environment for the horses, but when winter came it was an emotional rollercoaster persuading her that frozen manure would have to wait until a thaw. It was painful watching her ability to communicate decline, as well as the struggle to perform certain tasks such as tying knots, putting on halters, or maneuvering clips/zippers/ buckles. Heidi’s outbursts of frustration re ected her emotional pain, and we all developed our own techniques in aiding her to minimize those scenarios as much as possible.

While there were many frustrating days for both Heidi and us, there were also beautiful moments seeded within these unhappy circumstances. Due to her cognitive decline, Heidi became almost child-like, which lent itself to the purest (and sometimes comical) interactions: a huge genuine smile when one of the horses would seek out attention, her mistaken conviction that Emilie had Alzheimer’s, and watching her deep belly laugh as Joe rolled around in the grass a er a case of the “zoomies.” One moment I will always cherish was an a ernoon when I came to the barn in tears a er learning some upsetting news. Heidi, who was verbally limited at this point, looked at me and said, “You are crying.” I said “Yes, I am,”

and brie y explained why. We then went about our routine, not mentioning it again. When I drove her up to the house that evening, instead of exiting the car and walking directly inside, she stopped and tapped on my window. As I rolled it down, she looked at me with a most compassionate stare that spoke volumes and then simply said, “I love you.”

This love Heidi held in her heart for her family and friends continued to extend to her horses. However, by 2022, interest in grooming and her riding abilities had diminished. Speci cally, she was no longer equipped to provide the training and mental stimulation Tobias needed, and this was taking a toll on his behavior. He was a young, rambunctious, smart horse who required consistency to maintain ground manners. A er multiple dangerous incidents, the decision was made by Glen to seek a new home for Tobias. Abigail and I began to network within our horse community to nd him a placement suited to his needs, knowing Heidi would be shattered. We were fortunate to connect with the Hoover family, who were more than excited to welcome Tobias into their family, regardless of the fact that he was lame from a recent hoof abscess. Glen’s plan was to tell Heidi that Tobias was leaving for training and would return when he was “ready,” with the intention that time and her failing memory would conspire to prevent her from realizing that he would not be returning. The Hoovers arrived on a warm May evening to pick up Tobias with great grace and compassion, as Heidi was extremely upset and confused, helplessly watching a piece of her soul walk onto that trailer. Abigail and I were there for support, but we were absolutely gutted witnessing our friend endure this loss. With Tobias in his new home, just “the boys”—Scooter, Henry, and Rod—remained at La Fazenda. Whitney had passed away the Fall prior. We were hoping a small herd of mellow-mannered geldings would aid in providing a safe environment for Heidi to continue her routine of horse care, but the quick progression of her disease was making her erratic behavior and unsafe scenarios increasingly harder to manage. By the end of summer, Abigail and I knew we could not manage the upcoming