A publication of Ideas from Robert Menzies College

Editor: Sam Wan

© Robert Menzies College 2024

Atul Gawande, a Professor of Health Policy and Surgery, at Harvard University writes that the question that transformed his end-

of-life care was: “What does a good day look like?” For years, he approached cancer treatment with the assumption of prolonging life, but was that what the patient wanted? How did they want spend their final moments? What does it mean to live beautifully? As I wrote my latest two publications, it dawned on me that from my university days of researching, I had always approached things with the assumption: “What is wrong with the world?” What was wrong shaped how I observed people, phenomenon, religious practices, and cultures; in turn, these things began to become problems to be fixed. As the adage goes, if you’re a hammer, everything looks like a nail.

“A BEAUTIFUL MIND IS SHAPED BY BEAUTIFUL QUESTIONS.”

On another episode of On Being with Krista Tippet, the American novelist, David Whyte, said: “A beautiful mind is shaped by beautiful questions.” At that time I was writing about beauty vis-à-vis theology and the experience of disability, I wanted the form to shape my enquiry: What beauty am I observing? How can it be more beautiful?

The telos of beautification shaped both the theological foundation of my research and the method of enquiry. When I began to engage in beautification, I found that I shifted from an enquiry of ‘need’ to an enquiry of ‘appreciation,’ it changed

"Atul Gawande: What Matters in the End," Krista Tippett and Atul Gawande: On Being with Krista Tippett, https://onbeing.org/programs/atulgawande-what-matters-in-the-end/.

"David Whyte: Seeking Language Large Enough," Krista Tippett and David Whyte: On Being with Krista Tippett, https://onbeing.org/programs/david-whyte-seeking-language-large-enough/.

my tone, posture, and the interpretation of data before me. The task of analysis and critique is part and parcel of research, but I saw that I was approaching antithetical ideas with a much softer tone. “What astounds me in this research? What makes me go ‘wow?’” It wasn’t a Pollyanna WOW that is blind to the issues of our world, but I observed how genuinely I prepared myself in seeing the good (rather than focus on the bad and ugly!).

Before, I would often want to hone into finding the exact issue or problem that needed to be fixed. When engaging research from the perspective of beauty, it pulled me back to look at the fuller picture, or to use ethnographist Clifford Geertz’s term, to see phenomenon and data with a “Thick Lens.”

“WHAT BEAUTY AM I OBSERVING? HOW CAN IT BE MORE BEAUTIFUL?”

In so doing, my practice widened to strengthening that which ought to be retrieved, deconstructing that which needed to be broken down, and considering new ways to beautify.

Theologian Von Balthasar posits that without beauty, there is no hope, desire, imagination, or love; for “we can be sure that whoever

sneers at her [i.e. beauty’s] name… can no longer pray and soon will no longer be able to love…. In a world without beauty… the good also loses its attractiveness.” Hope, desire, imagination, and love are some of the very core themes of what it means to be human – and so the very correlation of beauty and humanity is that the latter cannot exist (or at least exist healthily) without the former. The act of research, as a human act, can be called an extension of being human, an act of beauty – seeking beauty, considering beauty, creating beauty. Beauty as a concept, as pursuit, and telos can have subjective elements, the aphorism “one man’s trash is another man’s treasure” and “beauty is in the eye of the beholder” explore its subjectivity. Even the most

Clifford Geertz, The Interpretation of Cultures: Selected Essays (New York Basic Books Inc. Publishers 1973). 3 3

The Glory of the Lord: a Theological Aesthetics., trans. Erasmo Leiva-Merikakis (Edinburgh: T&T Clark 1982), 18-19.

repulsively horrifying acts, e.g. Nero’s burning of Rome or the answer to Nazi’s final question, are acts that seek to beautify the whole with (inhumane) means towards the some form of desired beauty (aesthetics, economy, ethnicity etc.). In a utilitarian (and even propaganda) way, these concepts –genocide as beautification, deforestation as beautification, capital punishment as beautification –as jarring as they sound, have been argued as beautiful and subsequently transforming whole moral landscapes in human history. Indeed, if my previous proposal is correct, i.e., to be human is to seek beauty, the concepts of genocide, deforestration, and capital punishment have equally been argued as humane

Alternatively, the same events are depicted by the films, Life is Beautiful or Schindler’s List, depict atrocious horrors in order to reinforce how human beings can be beautiful, ought to be beautiful, by reclaiming a form of beautiful in spite of another’s

totalising vision of beauty. In the cases above, humans are capable of horrifying acts for the sake and in the name of beauty, and at the same time, reclaim the beautiful in the midst of horror. Where, then, lies the locus for beauty? Perhaps, if we use the Robert Menzies College motto “Vera Cogitate,” how do we contemplate on true beauty?

Vera Forma

In this continuation of Robert Menzies College’s Vera Cogitate publication, I’m delighted to introduce three pieces of research written by our

current 2024 post-graduate residents. These pieces were all presented at our post-graduate supper in semester one, revolving around the theme “Considering Beauty.” Ivana sets the scene by outlining the age-long debate of whether beauty

ought to be considered from above (Plato) or from below (Aristotle). Yuma explores the potential hope found in medical trials for a drug that may impede and reverse motor-neurones disease. Then, as an interlude, I share some pieces of verse and photography written and taken during my travels reflecting on natural beauty. Alec, a visiting Phd. Candidate from the University of Manchester, shows us the beauty in a dying star. Rounding off our publication, our Scholar-in-Residence, Dr. Gordon Menzies, provides some reflections on these pieces. Four perspectives of looking at beauty and how beautification and humanity align together.

May you find truth (and beauty) in these pieces.

Sam Wan

B.Ed (Primary, USYD), MDiv (ACT)

Dean of Academics | Editor – Vera Cogitate. Macquarie Park, April 2024.

Ivana Silic (University of Zagreb)

In the 21st century, the wide range of views on beauty mirrors the complexity of the human experience. It seems as if no single prevailing

view is supreme, as beauty is subjective and shaped by cultural, social, and individual factors. In order to comprehend where we can find beauty in design, it is essential to acknowledge the connection between beauty and design, which can be better understood by considering both historical influences and potential future developments.

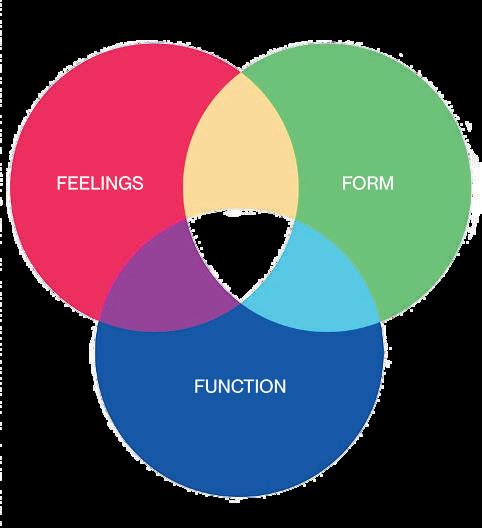

Throughout history, the perspective of design has shifted from a narrow focus on aesthetics to a more comprehensive acknowledgment of its enormous impact on all aspects of life. In ancient cultures, design was frequently associated with craftsmanship, and it served primarily decorative objectives. However, as civilizations developed, the role of design grew to include practicality, usability, and social importance. The Industrial Revolution pioneered a new paradigm of design characterized by mass production, standardization, and efficiency, while the Bauhaus movement, with its emphasis on “form follows function” revolutionized design thinking by prioritizing simplicity, utility, and accessibility. This shift towards functionalism laid the foundation for contemporary design principles, emphasizing the integration of form and function to create meaningful and impactful experiences, which is something that designers of the modern discourse still refer to as the three fundamental principles. So where can we place beauty in this diagram that so clearly encompasses the definition of design?

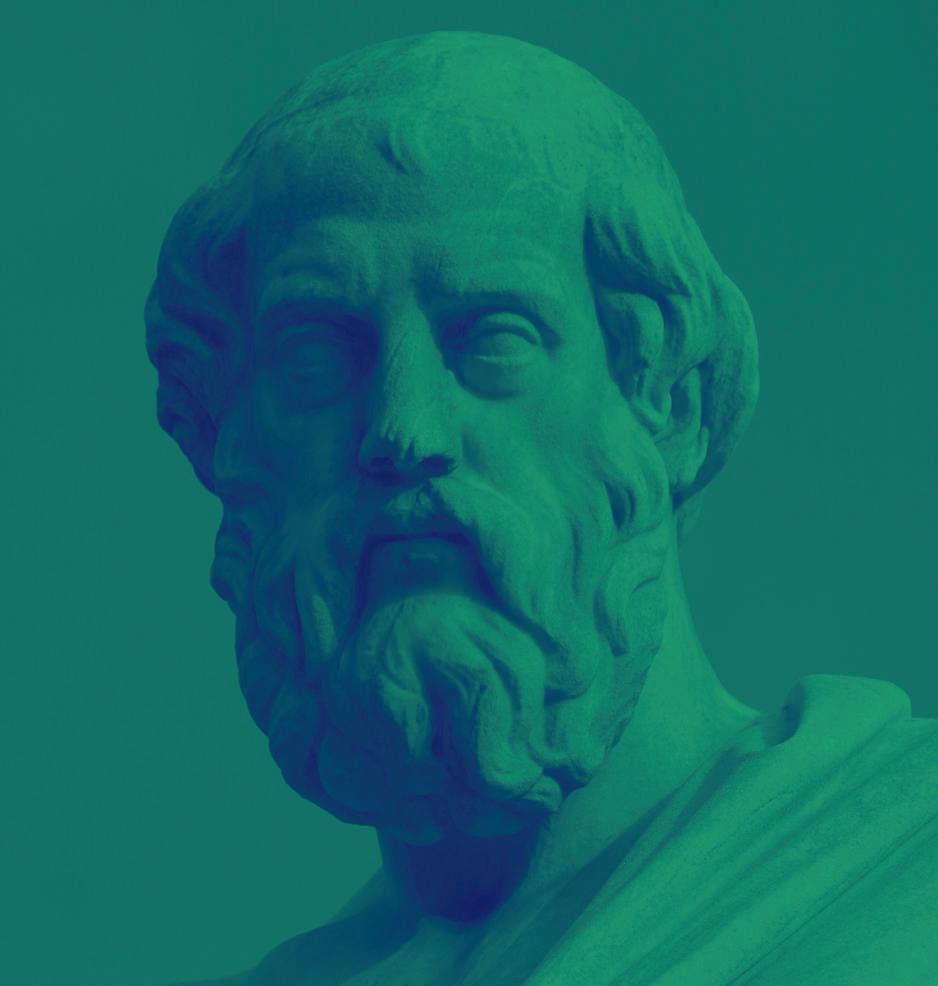

By taking another journey through time, back to the era of the Italian Renaissance and Raphael’s painting "The School of Athens,"

we encounter Plato and Aristotle, two towering figures of ancient philosophy. We can see them positioned in the center of the composition, debating the question as old as time itself: Where is beauty?

Surrounded by a gathering of various philosophers, they present two divergent perspectives on aesthetics.

Plato, shown with his characteristic long beard, gestures skyward, symbolizing the transcendence of beauty beyond the physical realm. For Plato, beauty resides in perfect forms beyond the material world, existing as an abstract harmony and balance. His stance reflects his belief in the transcendental nature of beauty, wherein it exists as an abstract ideal,

untouched by earthly imperfections. Plato envisioned beauty as a realm of perfect forms and harmonious proportions, inviting contemplation and introspection. In contrast, Aristotle stands firmly rooted on the ground, his finger pointing downward to emphasize his connection to the tangible world around him. For Aristotle, beauty was found in the here and now, in the natural order of things, and in the sensory experiences that define human existence.

FOR PLATO, BEAUTY RESIDES IN PERFECT FORMS BEYOND THE MATERIAL WORLD... FOR ARISTOTLE, BEAUTY WAS FOUND IN THE HERE AND NOW.

Even though these are ancient perspectives on aesthetics, the debate over who holds the correct view starts to pale in comparison to the value of blending these perspectives within modern design, where design continuously confronts challenges that we never thought would become our reality. Combining philosophical views and design thinking as a means of addressing these challenges, contemporary designers navigate the complex interplay of feeling, form, and function.

A design can be beautiful by form.

A design can work beautifully.

A design can evoke beautiful feelings.

A

A DESIGN CAN WORK BEAUTIFULLY.

When all this comes together, we should be able to find beauty in all of the aspects of what is considered a good design, Homo Forma

including the process and the final product. Beauty is inherent in the emotional and sensory responses evoked by a design. It encompasses the atmosphere, mood, and ambience, as well as the pleasure derived from interacting with it. Form is where beauty manifests in the visual elements, including the harmony of shapes, proportions, and colors. It encompasses the aesthetic appeal of the design's geometry, materials, and composition. Beauty emerges from designs that are not only functional but also elegantly solve problems and enhance user experiences. Efficiency, simplicity, and ergonomic considerations contribute to the beauty of a design's functionality.

As users and designers, our journey to finding and creating beauty requires exploration and observation of our everyday lives, from noticing the playful interaction of light and shadow in a room to the intricate texture of a certain material. It demands an open mind and a willingness to embrace looking at our surroundings actively, questioning the unique perspectives that have shaped our understanding of beauty so far. In the end, the pursuit of beauty in design is a testament to the enduring power of human creativity and expression. It reminds us that beauty is not merely a surface-level adornment but a profound reflection of our shared humanity, capable of inspiring wonder in the most unexpected places.

A

Yuma Okamoto

B. Clinical Science (MQ), M. Research (Current, MQ)

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), also known as Lou Gehrig's disease, is a devastating neurodegenerative disorder

characterised by the progressive degeneration of motor neurons, leading to muscle weakness, paralysis, and ultimately, death. This disease affects approximately 1 to 2.6 individuals per 100,000 people annually, with an average age of onset typically between 58 and 60 years old.

treatments to cure or reverse its progression. Therefore there is urgent need for further investigation into the underlying mechanisms of the disease and the development of novel therapeutic interventions.

My interest in ALS research was sparked during my final year of Bachelor of Clinical Sciences at Macquarie University, where I had the opportunity to

This is a fatal Motor Neurone Disease (MND) as patients face a life expectancy of only 2 to 5 years from the onset of symptoms. As the disease progresses, individuals with ALS gradually lose their ability to move, speak, swallow, and breathe, resulting in profound disability and a significant decline in quality of life.

Despite extensive research efforts, the aetiology of ALS remains largely unknown, and currently, there are no effective

undertake a research rotation unit with a focus on MND. Working alongside experienced researchers in the MND research team, I was interested in revealing ALS pathogenesis and gained valuable hands-on experience in laboratory techniques such as cell culturing and immunofluorescent imaging. The collaborative environment and cutting-edge projects I was involved in inspired me to pursue a career in academic research.

Now, as a first-year Master of Research student, I am involved in investigating ALS using a mouse model. This experience Where next?

has provided me with a broader perspective on research methodologies, particularly in vivo mouse work and preclinical trials. By studying ALS in a laboratory setting, I am committed to contributing to the development of effective therapies that can improve the lives of ALS patients.

The quest to find a cure for ALS is not without its challenges, but it is a mission fueled by hope and determination. My research aim is to unravel the complexities of ALS pathology and identify potential therapeutic targets. Through innovative approaches and collaborations, I believe we can create new treatments that offer hope and beautiful lives to come for patients and their family.

Each experiment I conduct, each discovery I make, brings us one step closer to restoring beauty in the experiences of patients with ALS. I believe that my research will serve as a crucial piece of the puzzle in the quest to conquer ALS and bring relief to patients and their families. Together, we can make a meaningful difference in the fight against ALS, and I am honoured to be part of this transformative journey.

Sam Wan

Dean of Academics RMC, B.Ed (Primary, USYD), M. Div (ACT, SMBC)

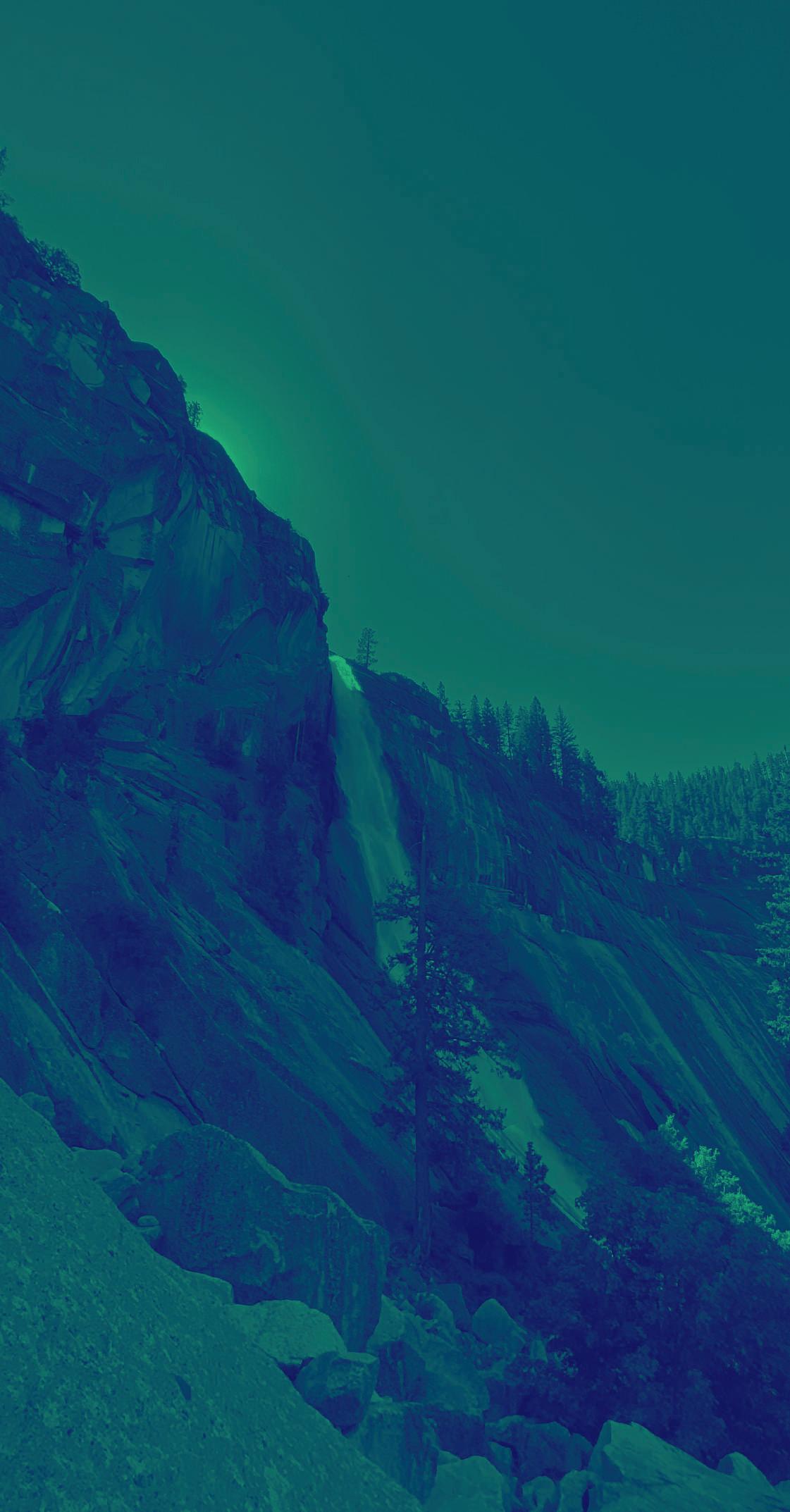

Are the mountains and trees who dance in three step harmony still beautiful in the absence of eyes that see?

Profligate with beauty that rolls one into another until the silence of peace is a cacophony.

Lightning struck A sycamore twice before it withered to the ground, thunder drowned. It dared the others to stand up for themselves. But they can’t. They know they can’t. Do they even want to? Who knows, they’re trees.

Nevada Falls, Yosemite National Park, California,

What can I say?

Kindness

Hides itself in the Wingbeats

Of butterflies that send Ripples

Cascading into a Stream

That trickles along Tributaries

Before gushing white-water Torrents –

Riverbed spilling gushing and turning gentle hardedged boulders, that grace thy feet – before An arc

Above air, held timeless for a sliver, rainbow flecked by sunlight and spray, but time can slow no more

A waterfall.

I stand and seek to embrace it’s litany.

My heart is in Toronto and my dreams are set to fly over the Pacific, over the Rockies, your hands, they safely do lie.

Alec Csukai Visiting PhD Candidate (University of Manchester)

“F

or my part I know nothing with any certainty, but the sight of the stars makes me dream” wrote Vincent van

Gogh in a letter to his brother Theo in 1888. A year later, in his asylum at Saint-Rémy he created The Starry Night, one of Western art’s great paintings. From William Shakespeare’s call to “Look how the floor of heaven / Is thick inlaid with patines of bright gold” to Oscar Wilde’s declaration that “We are all in the gutter, but some of us are looking at the stars”,

we find that humanity has often looked up to the stars in search of beauty and inspiration. Why is it that we find these little points of light so captivating?

As astronomy answers more of our questions about the stars, as uncertainty turns to certainty, do our dreams become any duller?

Ancient civilisations often linked celestial objects with the mystic. For the Chinese, the heavens were linked to the veneration of ancestors; for the Inca, the Milky

Way represented a bridge to the divine realm; for the Egyptians, the annual flooding of the Nile was identified with Sirius and its personification as the goddess Sopdet. The ancient Babylonians had a cosmology which placed the stars in a firmament which divided the Earth from Heaven. This idea was adopted by the Greeks, whose model of celestial spheres contained an outer starry orb, which Ptolemy placed at a distance of at least 20,000 Earth radii.

“WE ARE ALL IN THE GUTTER, BUT SOME OF US ARE LOOKING AT THE STARS”

For over a millennium, the geocentric model of celestial spheres became the Western consensus, until it was challenged by Nicolaus Copernicus during the Renaissance. Despite Copernicus’ status as a Catholic cleric, his heliocentric model was treated as an affront to religious authorities at the time, both new and old. The reformers Luther and Calvin are both known to have mocked Copernicus and his ideas, while the Catholic Church tried and convicted Galileo of heresy for espousing Copernicanism. These incidents may be interpreted as the beginning of centuries of apparent conflict between science and faith. Our modern knowledge seems to place a greater divide between the cosmos and the divine, but the stars do not lose any of their beauty because of it. The truth reveals itself to be just as wonderful. We now know the Universe to be absolutely vast, with each star functioning as a sun to its own stellar system. Even the very closest star, Proxima Centauri, is over a million times further away than Ptolemy’s estimate. These unimaginable scales are frequently employed to bedazzle viewers of pop astronomy content: a simple YouTube video (Universe Size Comparison 3D) which zooms out from the Moon to the Milky Way has managed to rack up more than 150 million views. Clearly, the stars are still able to fascinate our imaginations.

The idea of the sublime perfectly captures our response to the stars. The sublime is that which inspires awe through grandness, to the extent of becoming incomprehensible. We may find hints of this through the works of humanity. In literature, the sublime manifests through breathtaking scope of imagination, as seen in the richly woven realms of J.R.R. Tolkien's narratives, stirring our hearts with a blend of wonder and timeless truths. Through architecture, entering the chasmic space of a cathedral, with striking light falling from windows towering above, one is roused to a sense of reverence. But it is in the works of nature that we truly meet the sublime face-to-face. The sublime is not always positive - it may also explain why our eyes end up glued to the TV when a cataclysmic earthquake strikes. The Anglo-Irish statesman Edmund Burke described how the sublime evokes a dual emotional response of fear and attraction. When we gaze up at the night skies, the universe’s unimaginable scale may perturb us with a sense of Lovecraftian horror, a notion of staring into the void.

We find ourselves small and powerless.

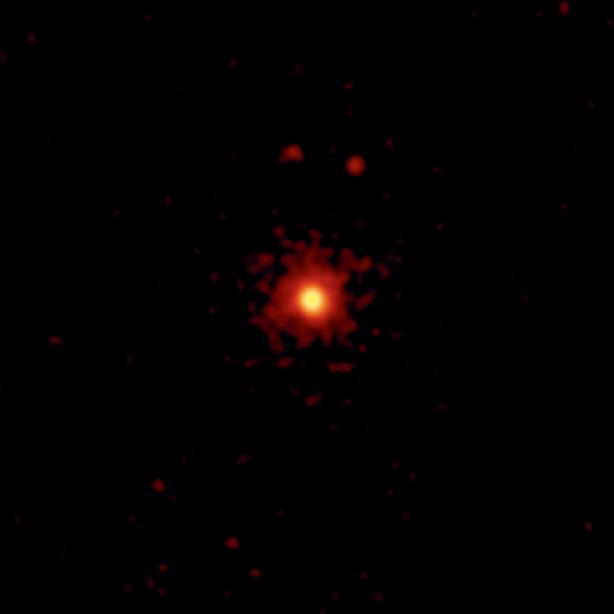

Proxima Centuri, source: NASA/CXC/SAO

Burke believed that the sublime was mutually exclusive with the beautiful, in contrast to Immanuel Kant’s belief that the confluence of both qualities allows an object to become splendid. If there is anything in the material world which exhibits splendour, surely it is the cosmos. The Universe that we discover through astronomy is a tapestry of wonders, with modern observatories producing vivid images which reveal intricate beauty in breathtaking detail.

NASA’s JWST represents a monumental feat in human ingenuity. One of the first images released from its observations was of the Southern Ring Nebula, which is a so-called planetary nebula. These objects are often chosen for public image releases, because of their stunning beauty. Looking through a catalogue of planetary nebulae is like ogling at a box of chocolates. But they do not merely hold aesthetic beauty. Through scientific studies of these objects astronomers have come to better understand them, which has revealed more of their beauty.

Planetary nebula turns out to be a misnomer. These objects have very little relation to planets. It turns out that they are a cosmologically ephemeral stage in the

THE UNIVERSE THAT WE DISCOVER THROUGH ASTRONOMY IS A TAPESTRY OF WONDERS.

Planetary nebula turns out to be a misnomer. These objects have very little relation to planets. It turns out that they are a cosmologically ephemeral stage in the death of stars like our Sun - their dying breath. As a star runs out of hydrogen fuel in its core, the star becomes unstable. The star’s core collapses until the temperature and pressure become sufficient so that nuclear fusion is able to transform helium into carbon, while hydrogen fusion ignites in a shell around the core. The overall effect of these changes is to push the outer material of the star away from the core, inflating the star into a red giant. Eventually, even the helium in the core will run out, causing further collapse and ignition of helium fusion in another shell around the core. This process blows the star apart, causing it to shed its outer envelope and leaving an inert core of carbon and oxygen. The beautiful planetary nebula that we observe is this material flying away from the dead star. This material is enriched with the heavier elements that are needed to form planets, becoming interspersed over time through the galaxy.

Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar boasted that he was “as constant as the Northern Star”. However, just as Caesar fell, we find that the

stars will eventually die. This is a reminder that everything is in flux: in the material world even that which is most grand will eventually meet its end. But this ending is necessary for what comes next. We believe that most of the carbon and nitrogen in our solar system will have come from the death of low mass stars, like that of the Southern Ring Nebula. These elements have allowed life to form on Earth. So in the flux, we may find beauty. A star, which holds beauty, becomes transformed into a planetary nebula, which also holds beauty, then into the wonders and beauties of the Earth that we experience everyday. And in the whole system, there is additional beauty.

IN THE MATERIAL WORLD EVEN THAT WHICH IS MOST GRAND WILL EVENTUALLY MEET ITS END. BUT THIS ENDING IS NECESSARY FOR WHAT COMES NEXT

Through science, we may increase our understanding of the truths of the world and the universe around us. These truths reveal beauty to us. It is through a commitment to truth, that we may reach closest to splendour.

Southern Ring Nebula, source:

https://webbtelescope.org/contents/media/images/2022 /033/01G70BGTSYBHS69T7K3N3ASSEB

Sources

http://www.vangoghletters.org/

Shakespeare - The Merchant of Venice

Oscar Wilde - Lady Windermere’s Fan

Fung, Yiu-ming (2008). "Problematizing Contemporary Confucianism in East Asia". In Richey, Jeffrey (ed.). Teaching Confucianism. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0198042563.

Jones, David M. (2015). The Inca World: Ancient People & Places. Thames & Hudson.

Redford, Donald B. (2001). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press.

Rochberg, Francesca (2010). In the Path of the Moon: Babylonian Celestial Divination and Its Legacy. Brill.

Neugebauer, History of Ancient Mathematical Astronomy, vol. 2

Beauty is an aesthetic naming of what we find attractive, satisfying and excellent in something or someone. It is perceived by the senses in art and music, and by the mind and imagination in literature. Some have hunted out its ingredients as unity, balance, symmetry and harmony of parts-but most of us do not experience beauty analytically at all. Someone says the word and we recognize it, and therein lies its charm. In the Bible, beauty is a general artistic quality denoting the positive response of a person to nature, a person or an artifact.

Birthed as an artistic response, beauty grows in its meaning to a generalized positive response to something or someone. We move even further from an artistic use of the term to a more metaphoric use when beauty is attributed to character of God. Here the positive qualities of artistic beauty provide a language for identifying the perfection of God and and the pleasure that a believer finds in that perfection. The scores of biblical references to beauty leave an impression that beauty is something of great value in human and spiritual experience.

FOR CHRIST PLAYS IN TEN THOUSAND PLACES, LOVELY IN LIMBS, AND LOVELY IN EYES NOT HIS TO THE FATHER THROUGH THE FEATURES OF MEN'S FACES.

Editorial

In the Beginning was Relation - Martin Buber

Sam Wan

Dean of Academics

The Multi-Identity of a Doctor

Stefan Thottunkal

Self and Other and the Singer Song Writer - the works of Sufjan and Adele

Sam Wan

Dean of Academics, B.Ed (Primary, USYD), MDiv (ACT)

Self and Other in Personal Identity

Ivana Silic (University of Zagreb)

Considering Theological Beauty vis-a-vis Disability and Impairment

Sam Wan