AC H ITECT UE DESIG NA T RR R

For Franco and Filippo

MARMO

Annual Magazine Issue no. 10, 2021 October

Editor in chief

Paolo Carli

Editor

Costantino Paolicchi

Deputy Editor

Aldo Colonetti

Editorial Coordinator

Eleonora Caracciolo di Torchiarolo Coordinator

Manuela Della Ducata

Editorial Staff

Eleonora Caracciolo di Torchiarolo, Nicola Gnesi

Graphic

Silvia Cucurnia, Thetis

Editor Henraux SpA

Printers

Grafiche G7 sas, Genova

Contributors

Cecilia Alemani, Roberto Bernabò, Chiara Bevilacqua, Jean Blanchaert, Edoardo Bonaspetti, Pickard Chilton, Lara Conte, Andrea Corradini, Turan Duda, Giacomo Faedo, Valentina Fogher, Rosi Fontana, Pierattelli Architetture, Bruna Roccasalva, Andrea Tenerini

Translations

Romina Bicicchi, Daniel Olmos

Photographers

Fogher Archive, Henraux Archive, Studio Tommasi Archive, Nick Ash, Ilario Bessi, Neri Casamonti, Stefano De Franceschi, Veronica Gaido, Nicola Gnesi, Giovanni Umicini

Cover Nicola Gnesi

“Printed under the auspices of Henraux SpA”

Registration no 3/2017 - 24/02/2017 of the “Registro stampa Tribunale di Lucca”

Paolo Carli

THE HENRAUX FOUNDATION. BETWEEN TRADITION AND EXPERIMENTATION, A POSSIBLE DIALOGUE

Edoardo Bonaspetti

PAOLO CARLI’S HENRAUX. BEAUTY AS A MODEL OF DESIGN

Aldo Colonetti

HENRAUX IN THE INTERNATIONAL ART SCENE. A STORY IN THE TELLING

Lara Conte

THE USE OF MARBLE FROM ALTISSIMO IN SCULPTURE FROM 1821 TO THE BEGINNING OF THE TWENTIETH CENTURY

Andrea Tenerini

HENRAUX SINCE 1821. THE GENESIS OF A GREAT ITALIAN COMPANY

Costantino Paolicchi FROM ARCHITECTURE TO ART AND BACK

Turan Duda

THE MORAL OF THE STORY ACCORDING TO NEÏL BELOUFA

Edoardo Bonaspetti

65 86 AC H ITECT UE DESIG NA T RR R

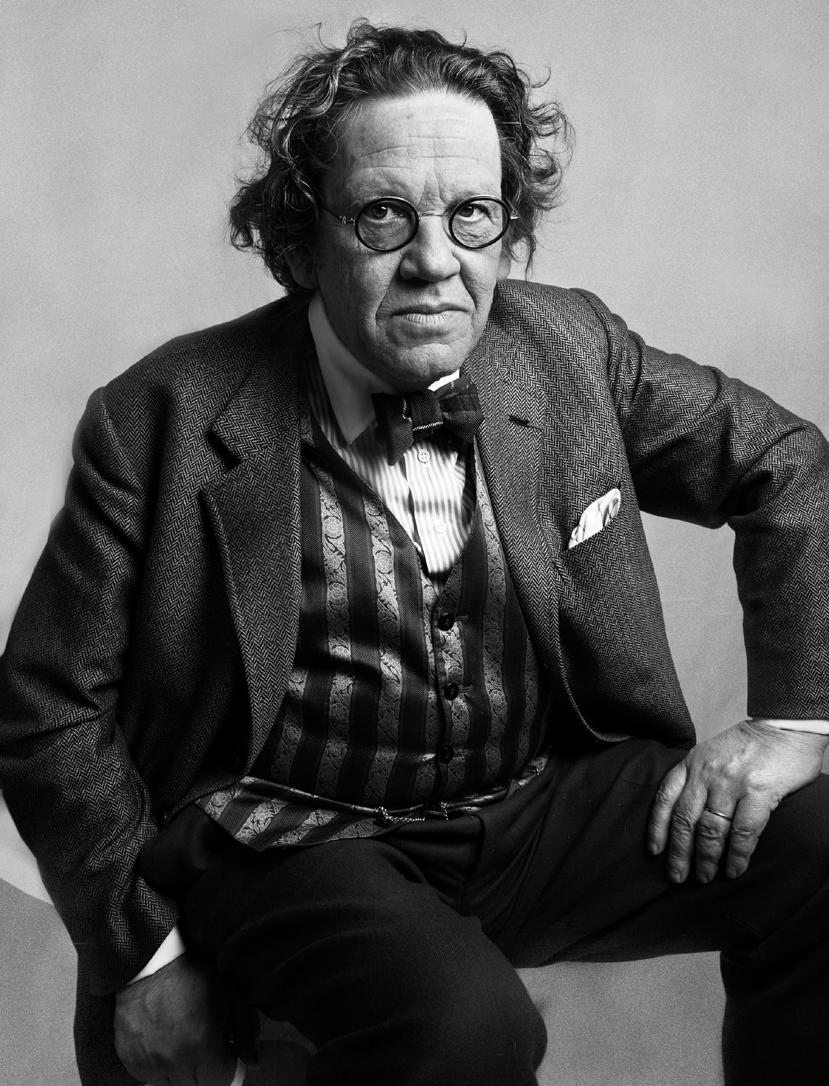

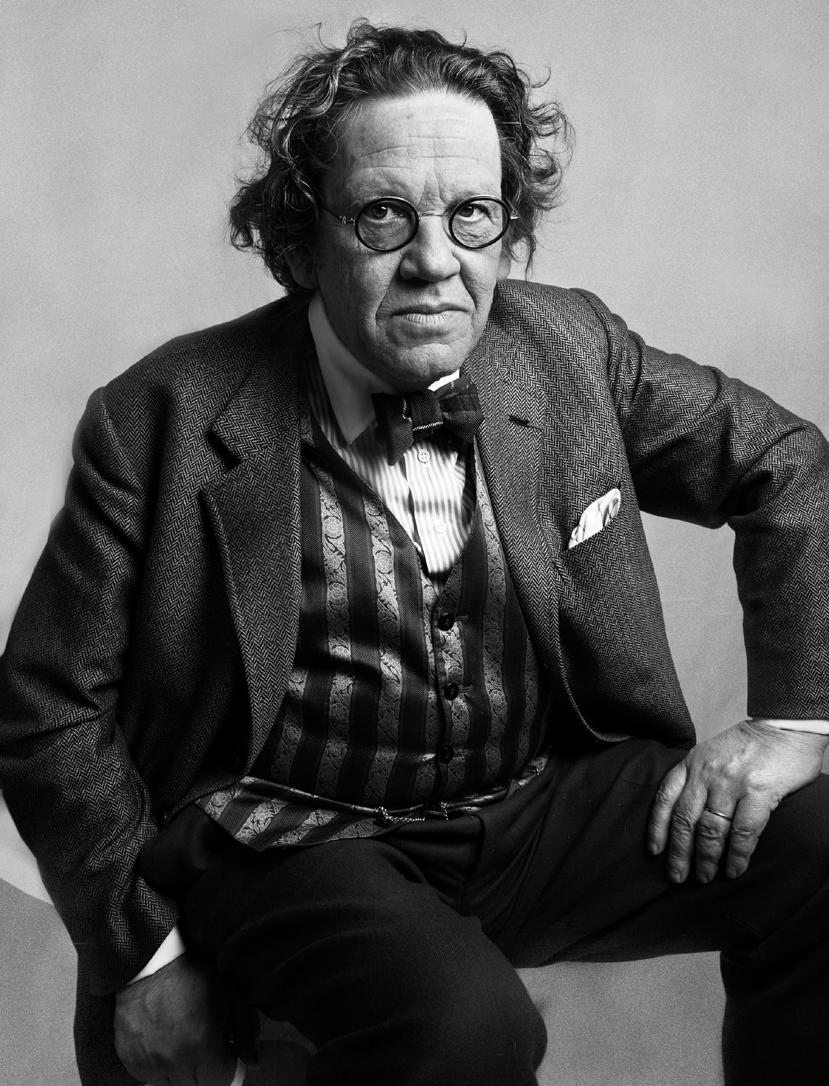

PHILIPPE, MARBLE AND THE HENRAUX PRIZE

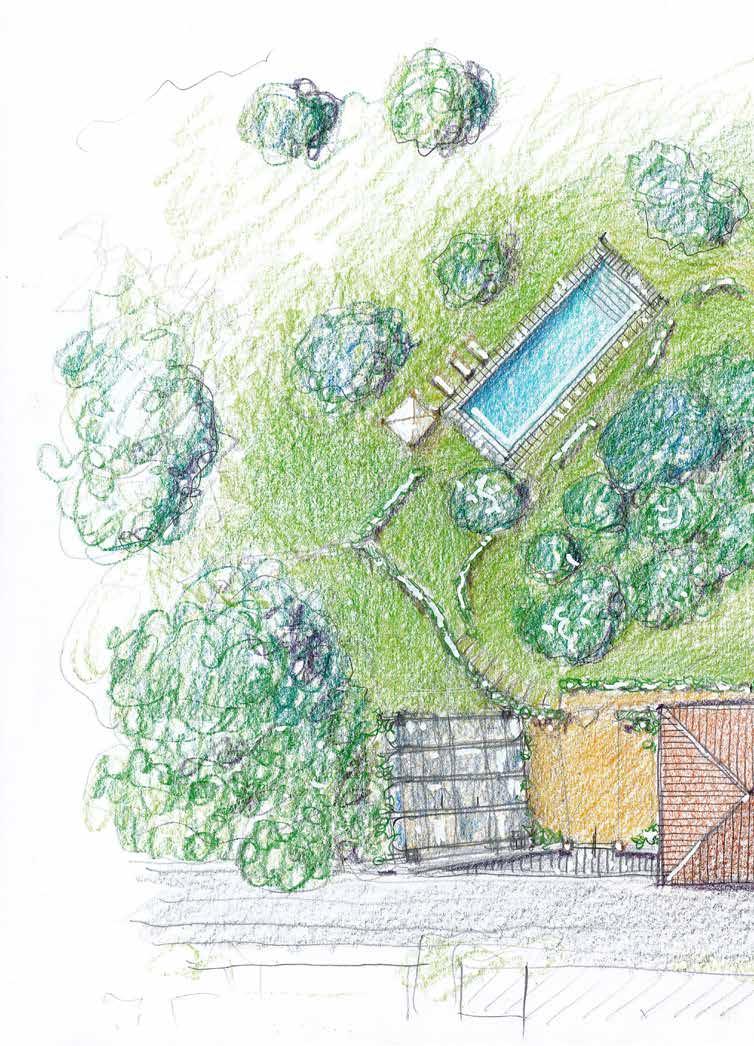

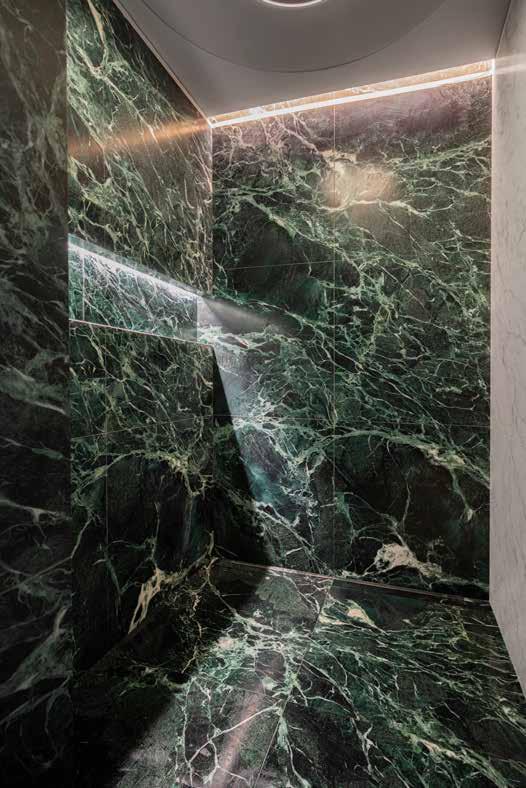

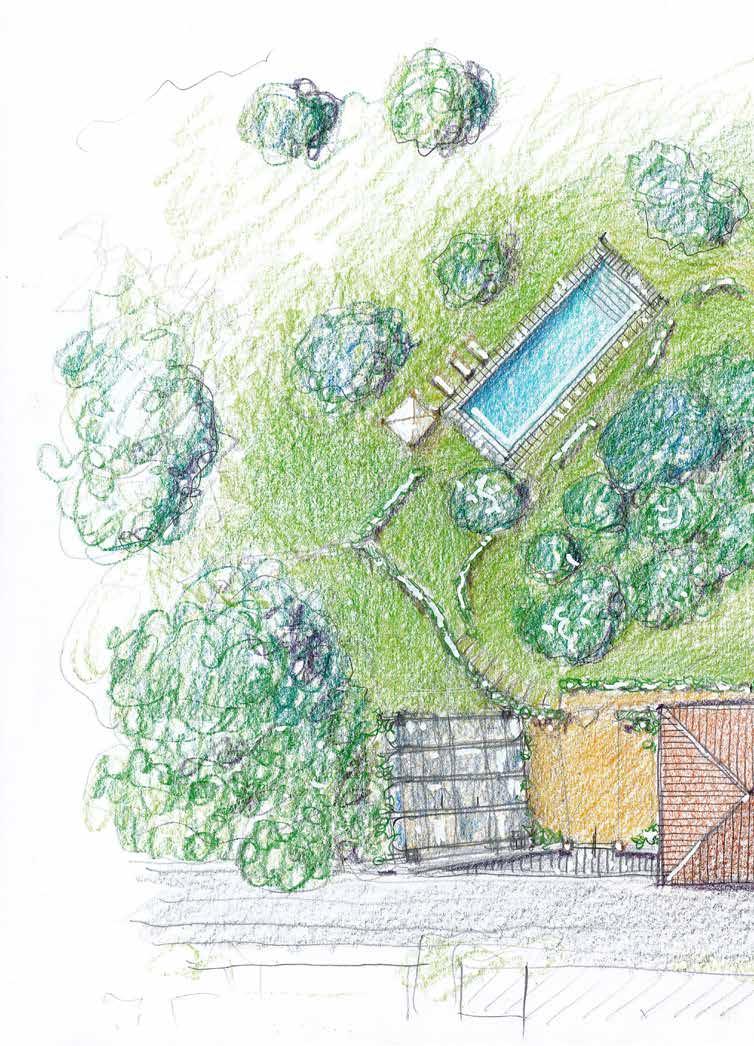

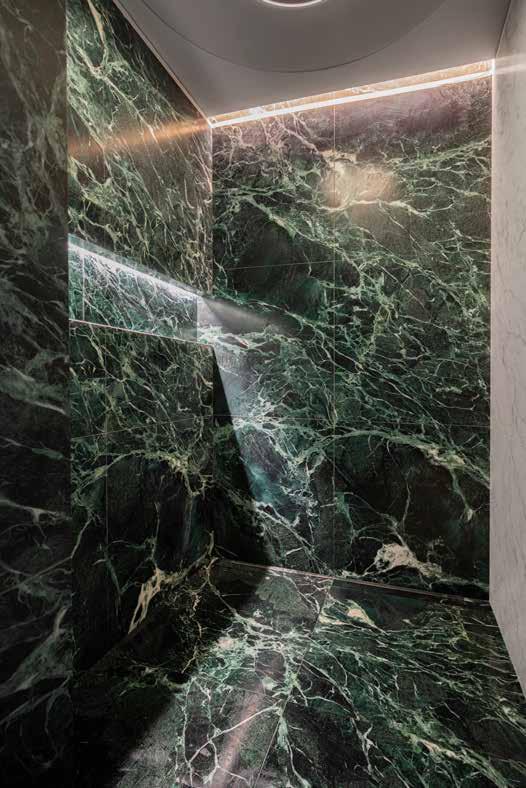

VILLA IL GIOIELLO: THE RESTORATION OF A HISTORIC VILLA IN FLORENCE, BETWEEN REFINED ATMOSPHERES AND ANCIENT INTIMATIONS

Pierattelli Architetture

10 7

40 54

20 30

EDITORIAL

Jean Blanchaert 76 92

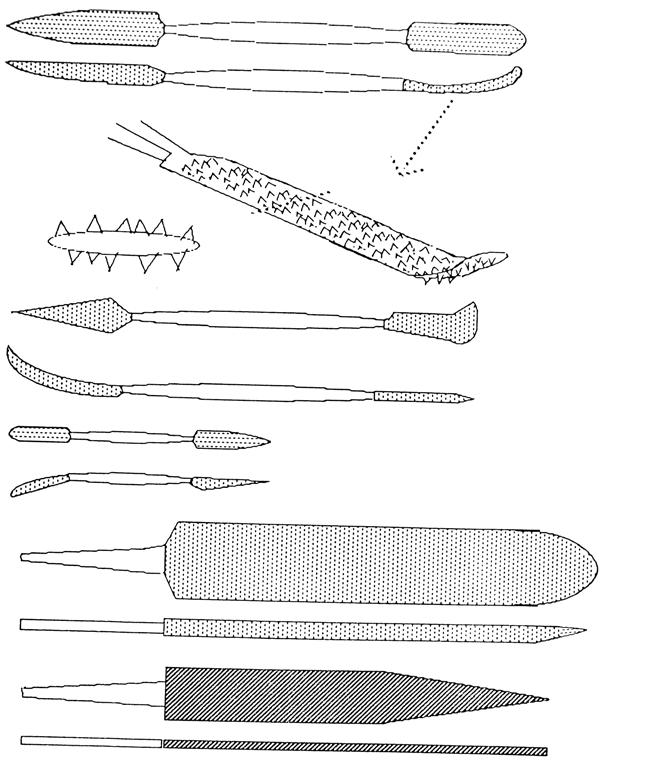

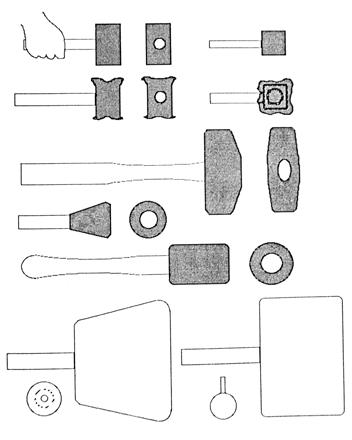

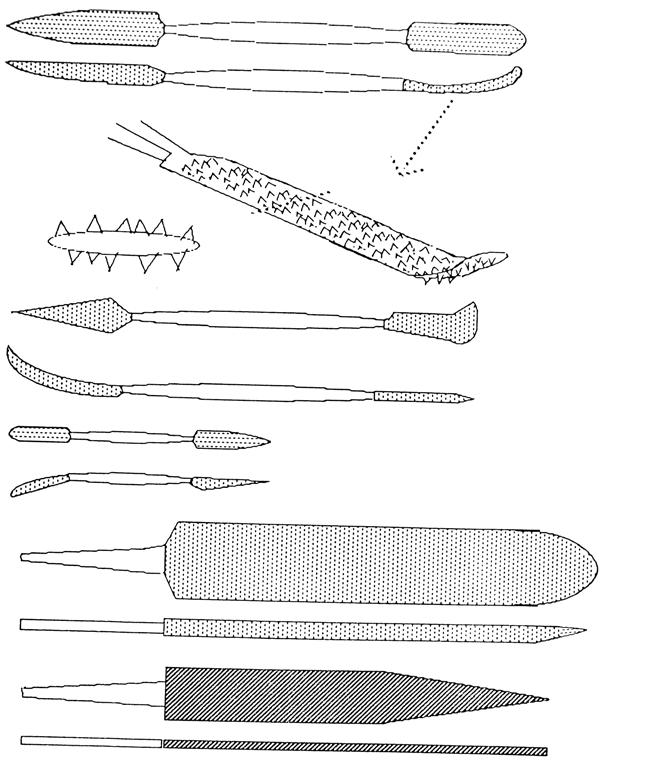

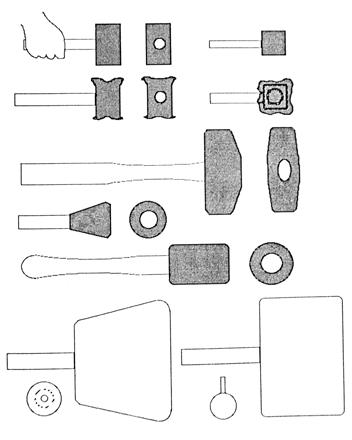

TO SCULPT. NEW TECHNOLOGIES FOR STONE SCULPTURE IN APUO-VERSILIAN WORKSHOPS

Valentina Fogher

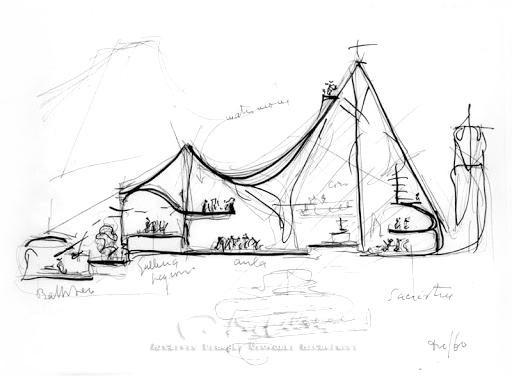

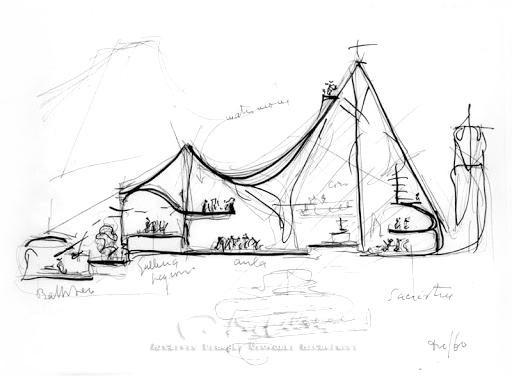

MICHELUCCI, MARBLE AND DYNAMIC SPACE

Chiara Bevilacqua

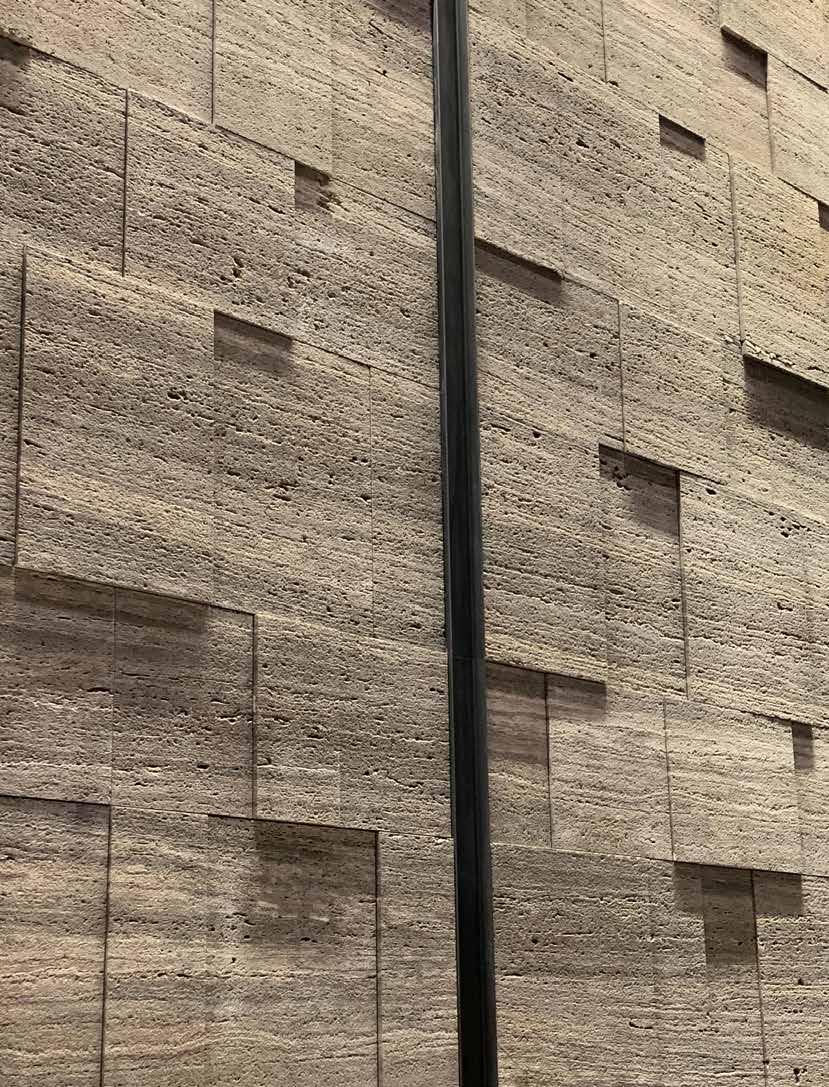

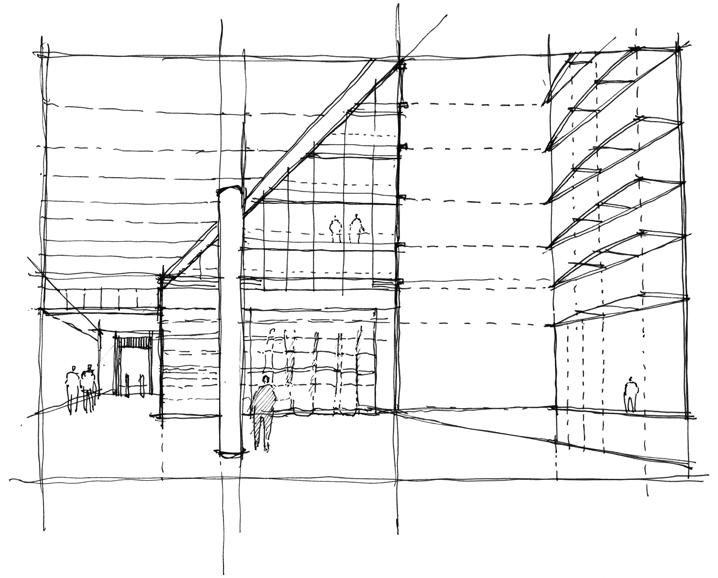

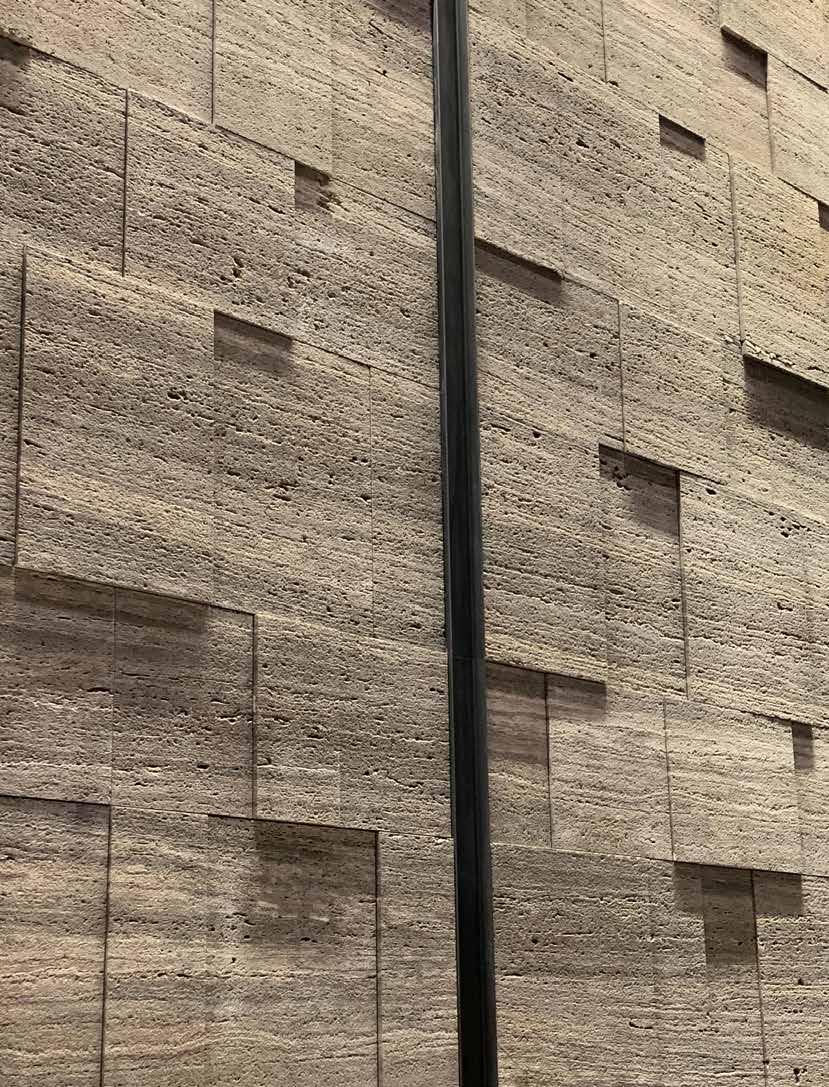

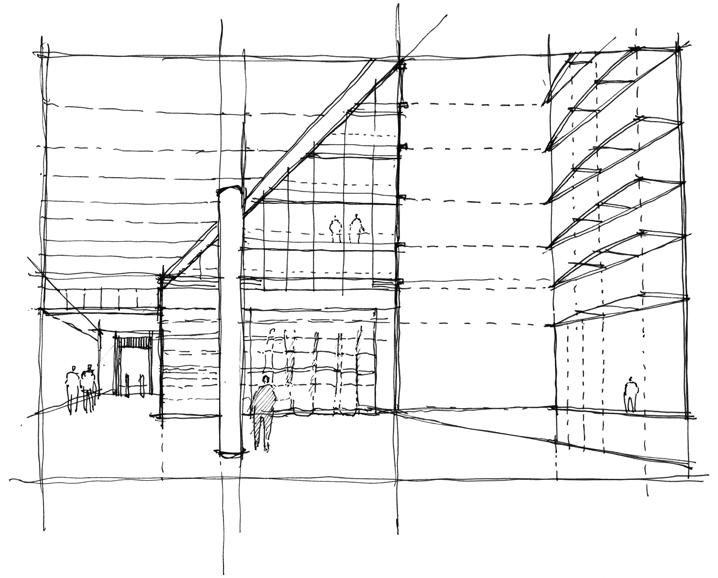

STONE SELECTION AND APPLICATION IN THE DESIGN OF “300 COLORADO”, AUSTIN, TEXAS

Pickard Chilton

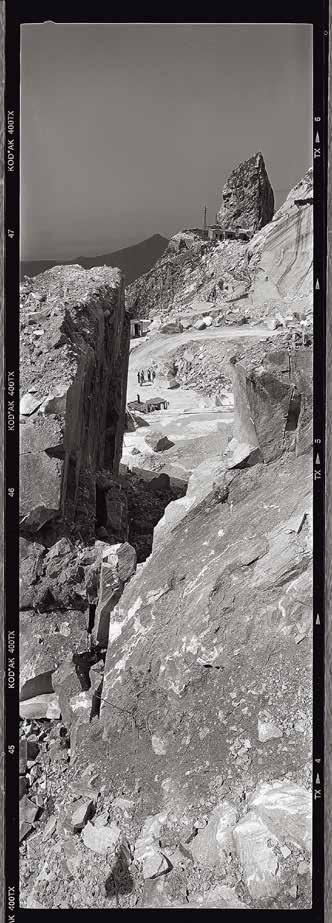

PHOTOGRAPHY AS A LANGUAGE OF VISION AND A SENTIMENT OF TIME

Costantino Paolicchi

ORGANIC FORMS, MARBLE AND METAL. HANNAH LEVY’S SCULPTURE IN NEW YORK

Cecilia Alemani

REDISCOVER MARBLE IN THE PRIVATE SPACE

Aldo Colonetti

LEONE TOMMASI. FAMILY ART

Roberto Bernabò

NAIRY BAGHRAMIAN. MISFITS

Bruna Roccasalva

BULLETIN

104 122 136 112 177 128 168 144 152

BY PAOLO CARLI PRESIDENT OF HENRAUX SPA AND HENRAUX FOUNDATION

This year’s 17th Venice Architecture Biennale has the title “How Will We Live Together”? This is the crucial question of our times, and it is with inexhaustible amazement that I see how, once again, it is the creative community who suggest the most acute reading of the present and show us a path to the future.

After living through the emergency last year, and through all the impossibilities of having the time and interior space to reach an overall reflection on what was happening, this year, in spite of ourselves, we have learned to coexist with a health crisis that continues, but with a minimum distance that allows us to make some considerations.

In light of the issues that are at the centre of our daily conversations with colleagues, neighbours, on social networks, which lead us to ask ourselves whether to consider our unquestionable freedoms, individual rights and duties, or the common needs of a community as a priority, whether to be individuals or communities, “How will we live together?” is indeed the question.

In making issue number 10 of Marmo I have realized that – perhaps unconsciously –Henraux gives the answer, which is nothing else than – simply, but not trivially – the synthesis of its work done so far. For two hundred years. Furthermore, I will also talk about this important milestone presently.

Henraux finds its strength – its answer – in the community. It finds vitality in the work, in the effort, in the thought and in the shared energies of hundreds of men and women who have followed one another within its walls over

two centuries and who have contributed, each with their own strengths – and with their own weaknesses, too – to make Henraux what it is today.

I arrive at this idea following a story that emerges not so much from the texts, which I will shortly go to mention, but from the images in this issue: historical, archival, black and white photos alternate, a little worn by time, to very recent photos, sharp, coloured, aesthetically the opposite to the previous images. In their heterogeneity, one element unites them: people. Whether they are photographs from the past or the present, they tell only one story: Henraux is made up of people who work. Together. The stories narrated by the images are accompanied by the words of our collaborators, which reinforce this idea of cohesive collectivity that emerges from the iconographic corpus. In anticipation of them, I would like to start with the contributions dedicated to Philippe Daverio and Giovanni Umicini, who recently passed away. They are homages (the first written by Philippe’s friend and companion of many adventures, Jean Blanchaert, the second by our director Costantino Paolicchi – full of vitality, sensitivity, melancholy – of course –but also irony) which restore to both, a profile that it is up to them, rich in shades and light and shadows. In humanity.

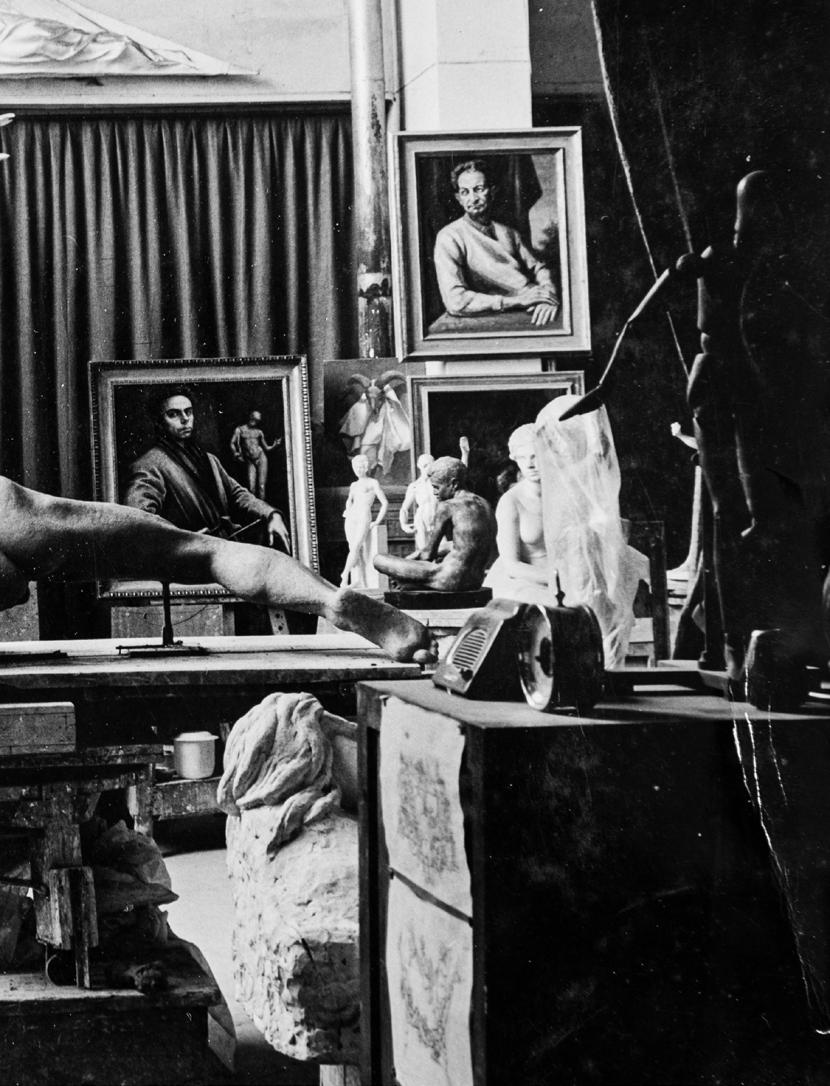

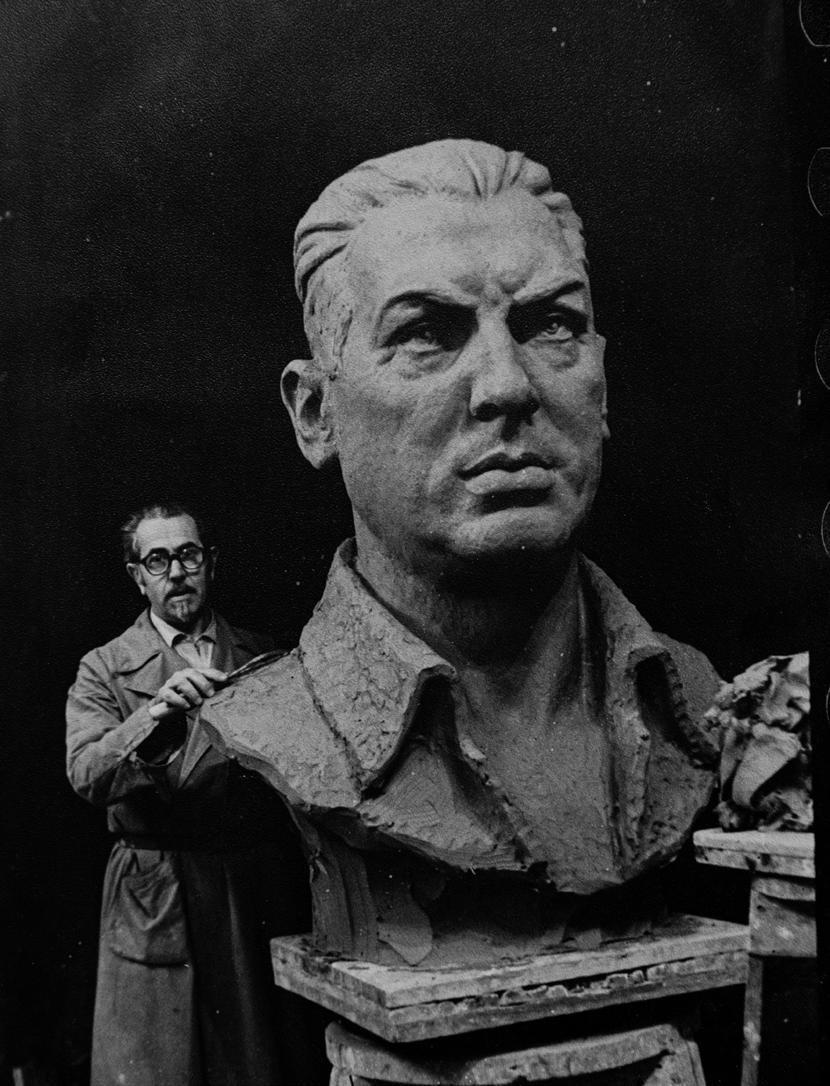

The column “The masters of Henraux”, inaugurated in the last issue, gives us the portrait of an artist who was the forefather of the history of contemporary art in Versilia: Leone Tommasi. His niece, Ilaria Tommasi spoke about it with Roberto Bernabò.

7

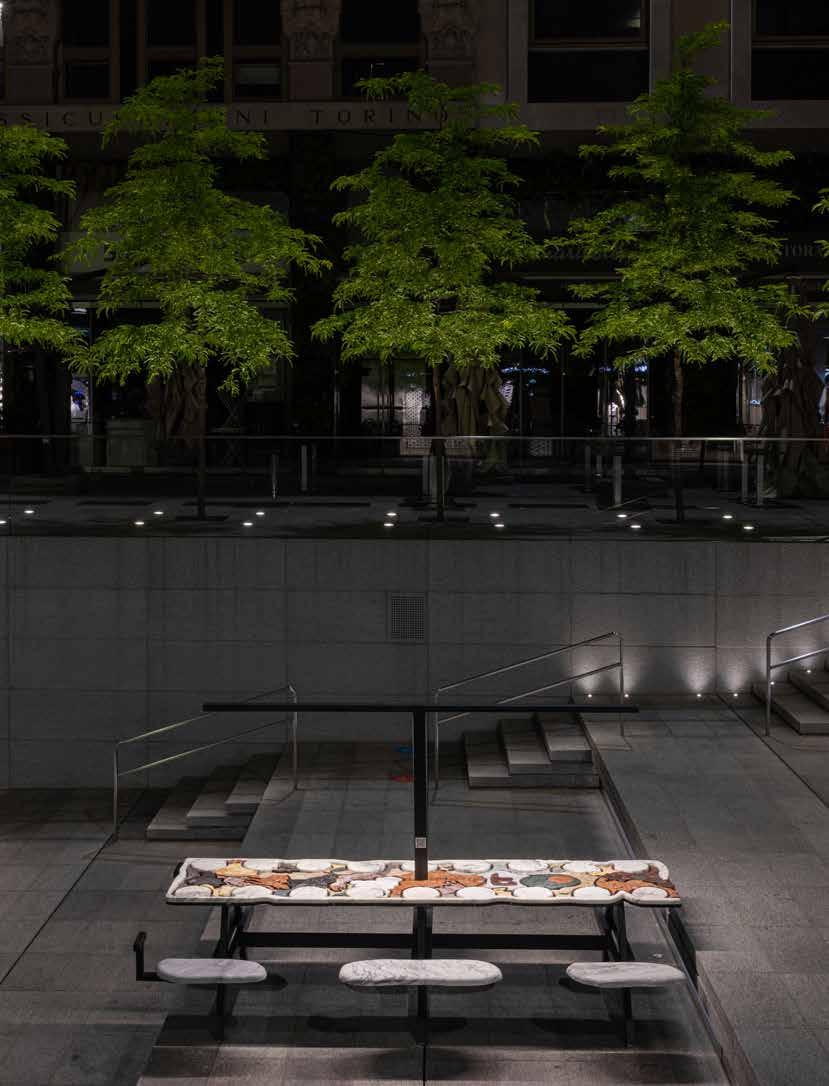

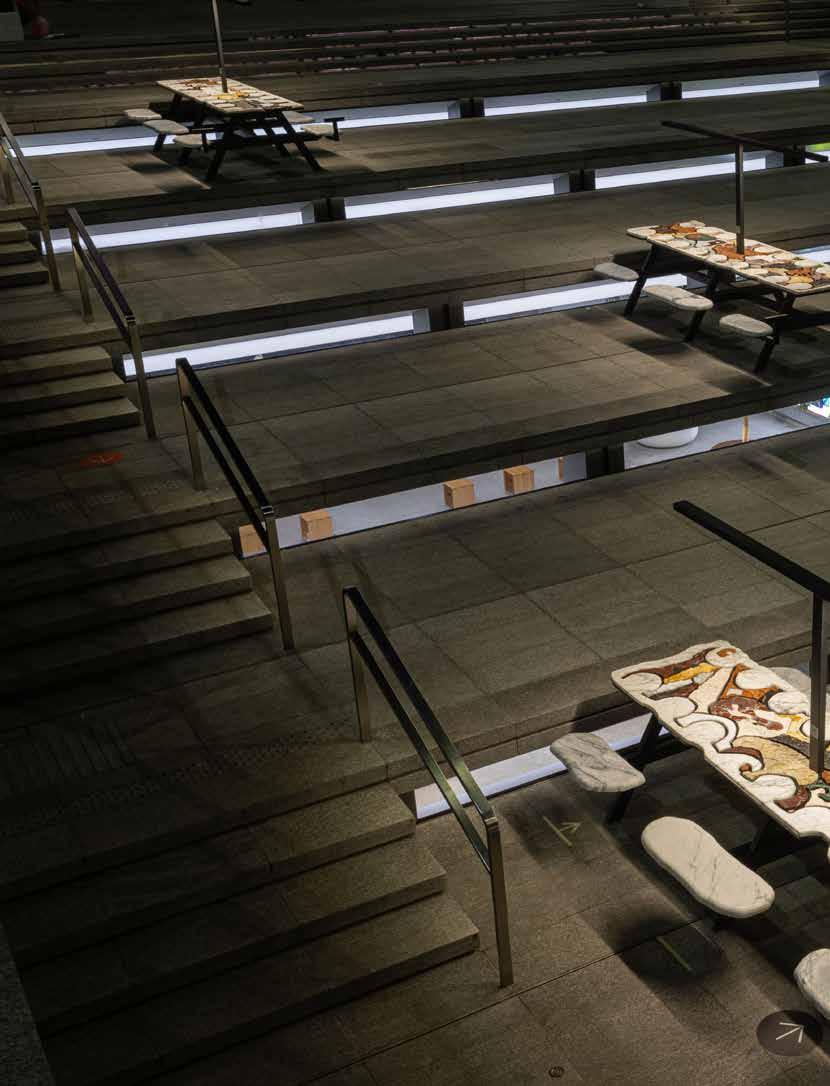

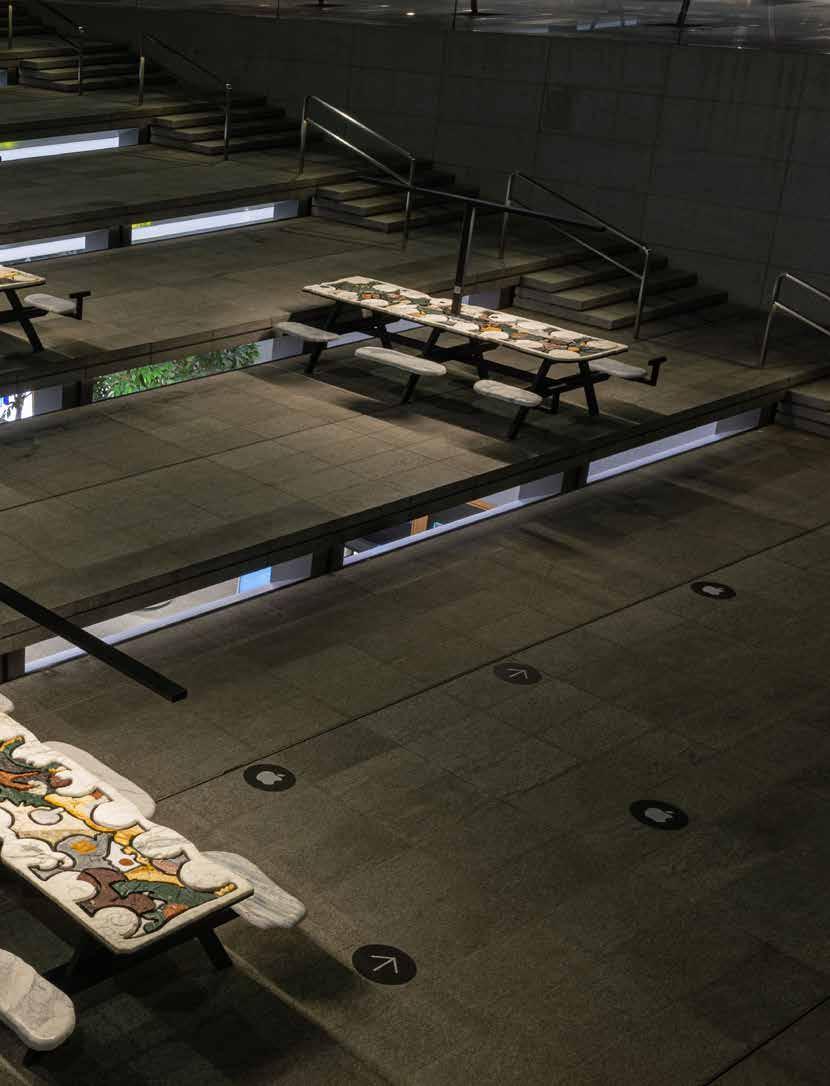

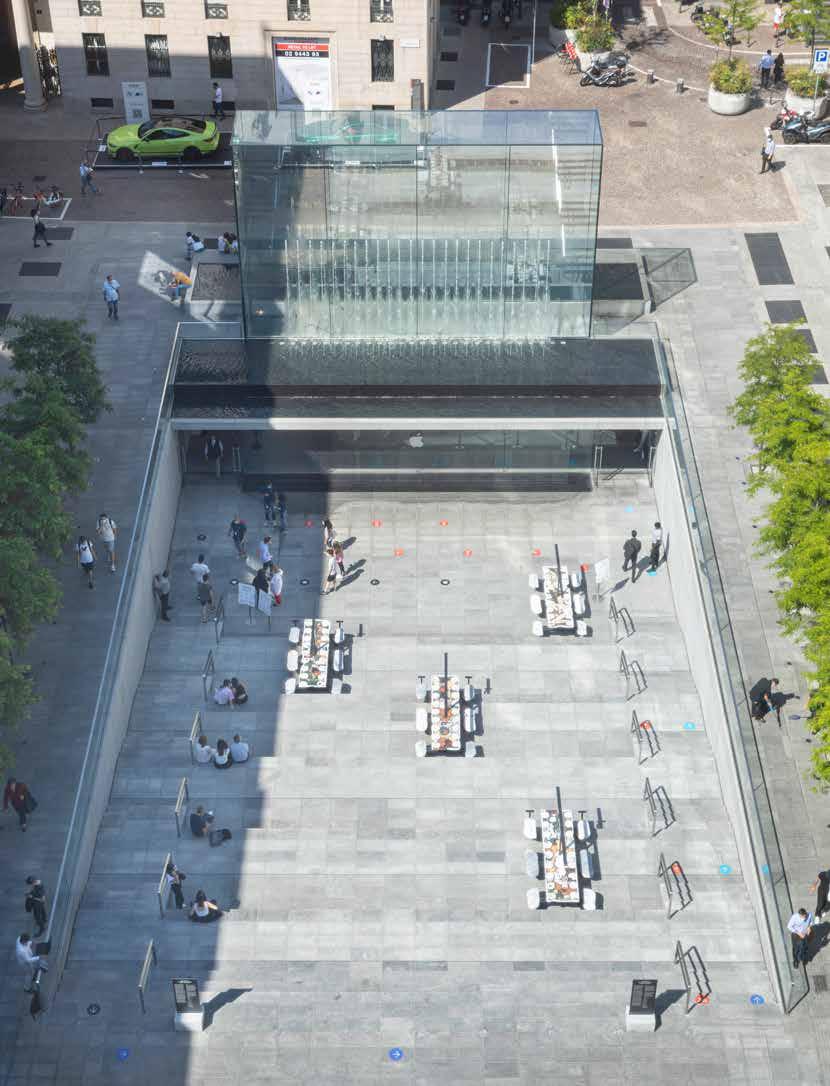

The tribute to the recent history of the company, which is above all a history of encounters to which these portraits testify, gives way to an in-depth study of today’s projects and to reflections on the present linked to the themes that are dear to us: art, design and architecture. The articles dedicated to the projects carried out by the Henraux Foundation in the last year, follow one another: one with the FrancoAlgerian artist Neïl Beloufa for Apple Piazza Liberty in Milan, one with Nairy Baghramian for the “Misfits” exhibition at the GAM –Gallery of Modern Art of Milan and, finally, the sculpture by Hannah Levy that Henraux produced for the High Line in New York. All curated by the writers: Edoardo Bonaspetti, Bruna Roccasalva and Cecilia Alemani.

In the field of architecture, we can find a splendid examination of the project for the Church of San Giovanni Battista “dell’Autostrada” by Giovanni Michelucci, penned by Chiara Bevilacqua alternating with the story of the most recent achievements to which the company has contributed its materials and know-how: the project in Washington DC with the Duda | Paine Architects studio and also in Austin, Texas, with the Pickard Chilton studio.

In the scope of design, one piece above all: Aldo Colonetti’s illuminating reflection on the multiple and new meanings that marble assumes in light of the new way of life that the pandemic has imposed on us and that the world of design simply cannot ignore.

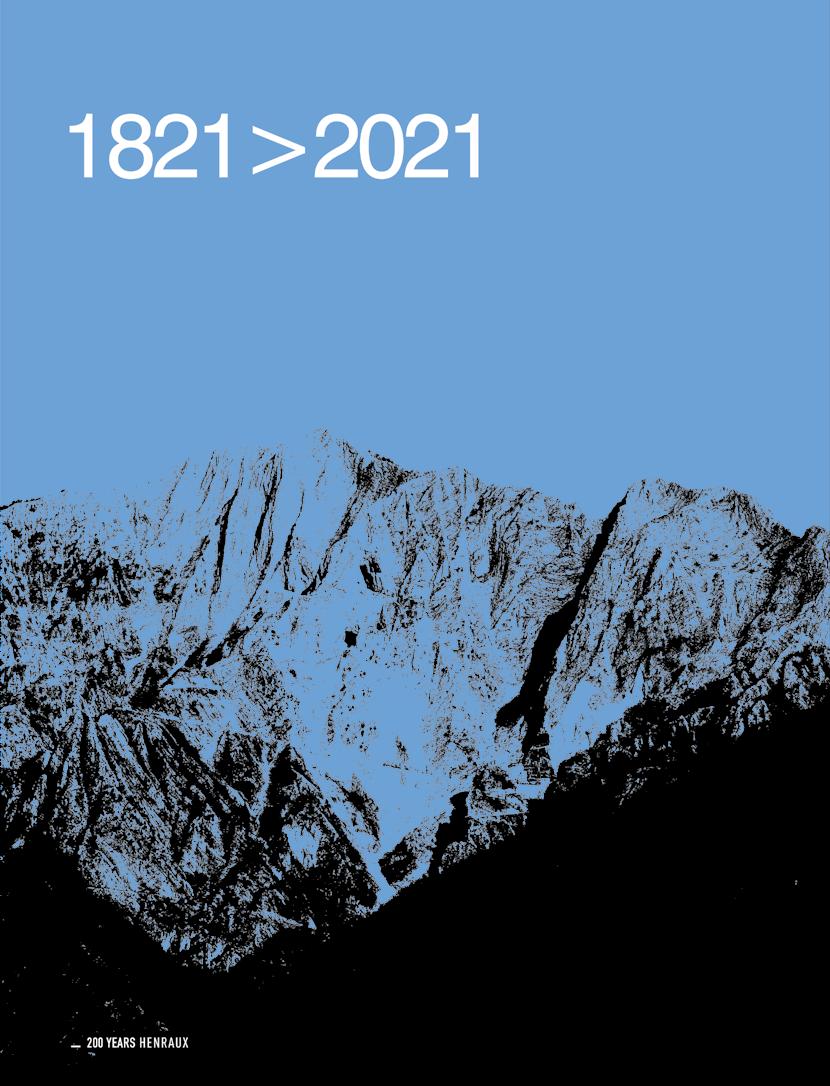

A very special section, which will remain unique in the history of the company, enriches the current issue of “Marmo”: is dedicated to the celebration of Henraux’s 200th anniversary. Henraux was founded in 1821.

In the whirlwind of emotions through which we look at this achievement – one which we can only partially celebrate given the times we are in – we have tried to line up the salient events that have characterized the path, in a backward journey that dates back from more recent times to the origins.

And so we begin with a contribution by artistic director of the Henraux Foundation, Edoardo Bonaspetti, who shares with the readers the vision that characterizes his work and which allows us to glimpse the frontiers he intends to reach in the near future.

Following that, in my conversation with Aldo Colonetti, I wanted to clarify the approach that characterizes my leadership of the company: an approach that as a priority, aimed to interpret its glorious history to be able to draw the best guidelines for the present and future. The Foundation, the International Sculpture Prize, the return of the publication “Marmo”, as well as all the technological innovations that have been introduced from an industrial point of view in recent years, all of these derive from that interpretation and are inscribed in my entrepreneurial style that in an attempt to make “beauty” from a design model.

From the story of Erminio Cidonio’s work –of his vision, of the renovations he made, of the crucial moment that he represented for the company – expressed to us with abundance by Lara Conte, we arrive at Andrea Tenerini’s research on the artistic personalities who from 1821 to the beginning of the twentieth century collaborated with Henraux, making use of its marbles and its workers. Starting with Giovanni Grazzini and Francesco Pozzi, passing through the Americans Horatio Greenough and Hiram Powers and reaching Auguste Rodin, the wealth of knowledge and experience brought by the experiences is very rich indeed.

From Costantino Paolicchi’s piece, we finally get to know the genesis of the company: the steps that led to its foundation and its evolution under its corporate profile until the advent of the “Cidonio era” in the Second World War. And the future? “How Will We Live Together?”. For us at Henraux, the question posed by the curator of the Architecture Biennale Hashim Sarkis also contains the answer: How Will We Live? Together.

8

1821>2021

Diego Marcon, Ludwig, 2018

THE HENRAUX FOUNDATION. BETWEEN TRADITION AND EXPERIMENTATION, A POSSIBLE DIALOGUE

BY EDOARDO BONASPETTI PHOTOS BY NICOLA GNESI

BY EDOARDO BONASPETTI PHOTOS BY NICOLA GNESI

It was a short step for Edoardo Bonaspetti from meeting the charismatic figure of Paolo Carli to accepting the role of artistic director of the Foundation. From the stories of the most recent projects, the vision of his direction emerges clearly, in a balance between history to be preserved and a future under the banner of experimentation.

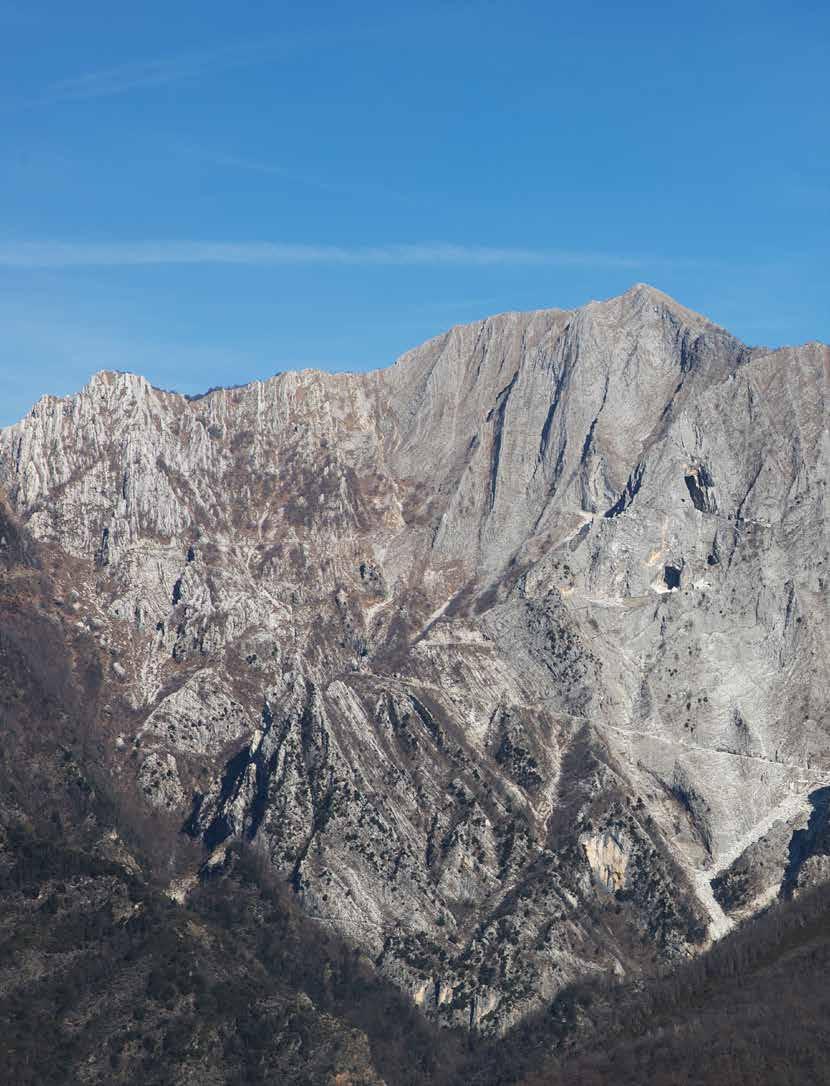

11 1821>2021

I first met Paolo Carli, president of Henraux Spa, in the spring of 2018 at the Milan Triennale. In those weeks I had inaugurated an exhibition at the institution and a mutual friend decided to introduce us, anticipating how his charisma and energy could give shape to interesting collaborations. The Triennale itself was evidence of this: recently, an imposing marble sculpture by Emilio Isgrò which Carli had produced in the company’s historic factories in Querceta, in Alta Versilia, was placed in the park in front of it. Its title, “ll seme dell’Altissimo” (“The seed of Altissimo”), refers to the mountain from which Henraux has extracted the precious material since the beginning of the nineteenth century and the seed –understood as the seed of art, a symbol of creative potential – suggests what life can offer and how, in some cases, it can surprise us in its evolution. On that occasion, I learned that the quarries had been discovered in the sixteenth century by Michelangelo Buonarroti for the commission of the facade of the church of San Lorenzo in Florence, that the company was founded in 1821 and that over the course of almost two centuries of activity, its history affected the architecture and artistic production of a vast international panorama. Paolo Carli told me about his projects to enhance the culture of marble and the legacy of Henraux, and how in 2011 he was committed to setting up a Foundation with the task of recovering both its vocation and innovative spirit in the various fields of visual arts, design and architecture. The reference model was the enlightened direction of Erminio Cidonio, director of the company during the nineteen fifties and sixties, who managed to create an international sculpture centre in Querceta, with the presence of artists of the calibre of Henry Moore, Hans Arp, Henri Georges Adam, Isamu Noguchi, François Stahly, Émile Gilioli, Georges Vantongerloo alongside many others, who gave life to an artistic and cultural season of great vitality.

The first initiative of the newly founded Henraux Foundation was the “VolareArte” event at the main airport

12 1821>2021

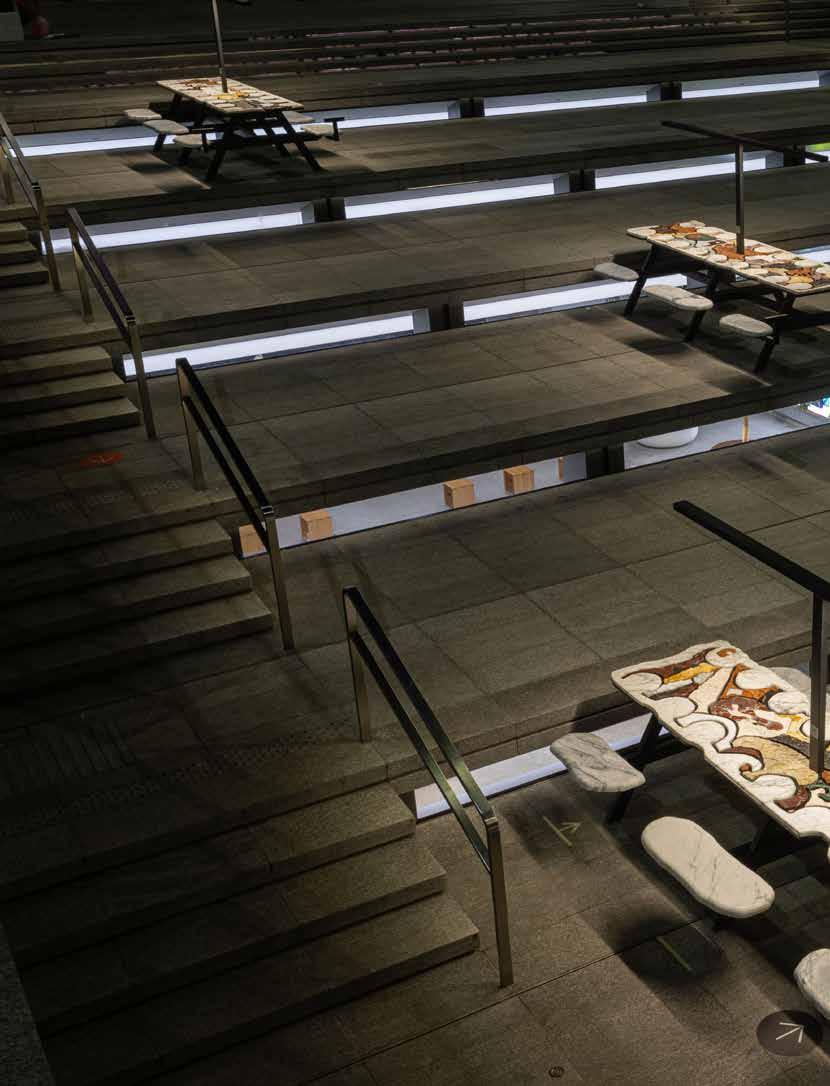

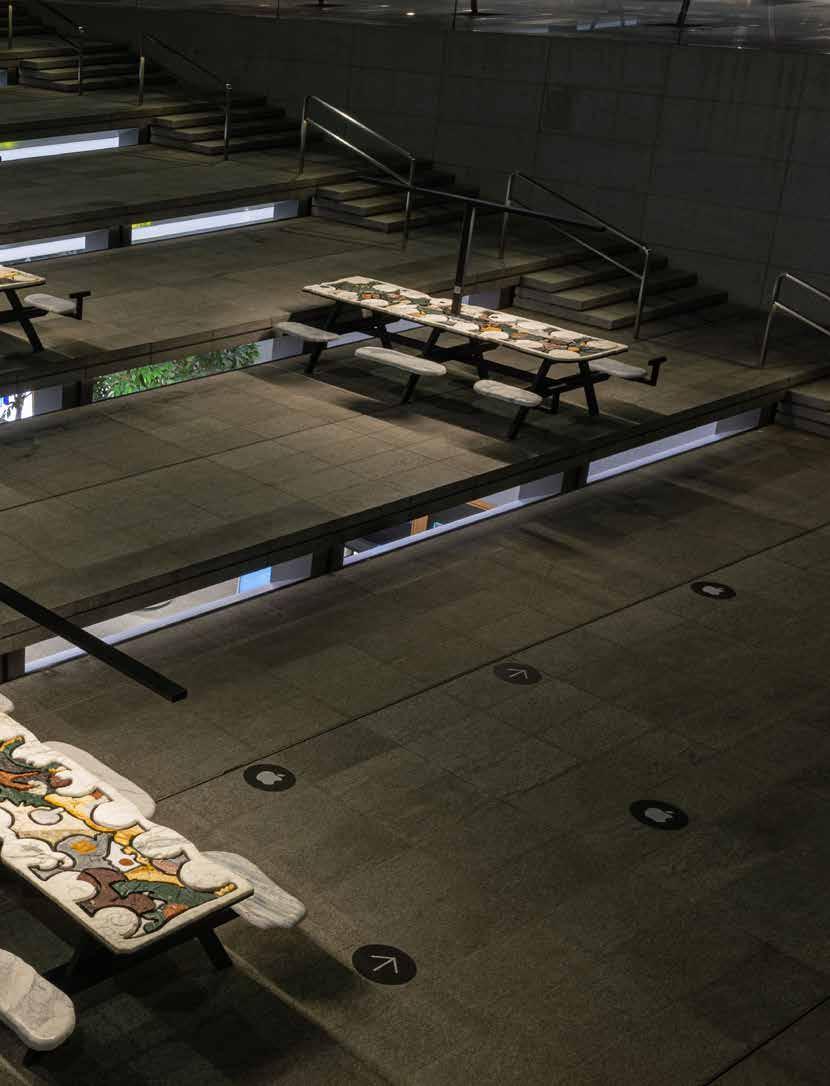

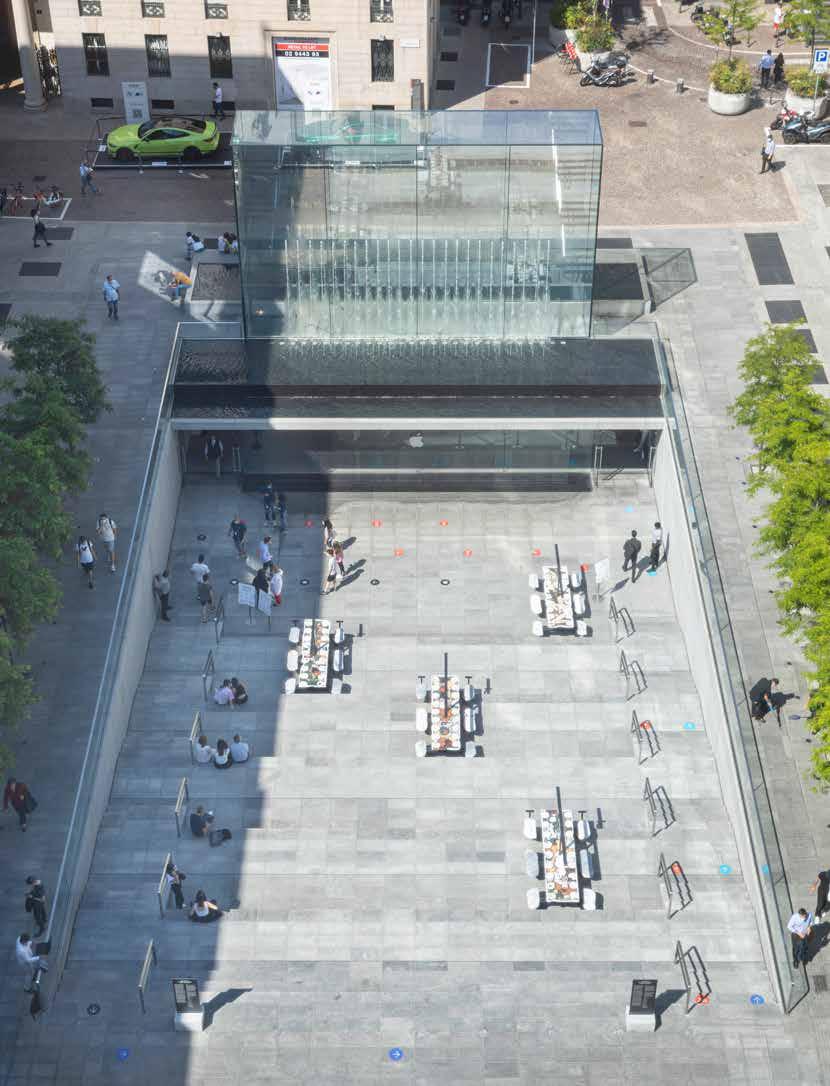

Above, Neïl Beloufa, The Moral of the Story, 2021, Milan, Apple Piazza Liberty, installation view

Nairy Baghramian, Misfits, 2021, GAM - Galleria d’Arte Moderna, Milan, installation view

Right, the artists Anto Milotta and Zlatolin Donchev at work in the Henraux workshop

13 1821>2021

We agreed that the new course should move along two guiding lines: on the one hand, to carry out ambitious exhibition projects in Italy and abroad and on the other to formulate collaborations with institutions, museums and artists in support of marble productions.

of the region, the Galileo Galilei airport in Pisa. The initiative, created in collaboration with SAT, the Tuscan Airport Company, offered arriving and departing travellers the opportunity to appreciate a series of site-specific sculptures and projects, presented every two years. In 2012 Carli also established the International Sculpture Prize, together with Philippe Daverio and Jean Blanchaert, it was the first in the world entirely dedicated to marble. The project, which continues to this day, is aimed at artists under the age of 45 and at the creation of works that combine ancient manufacturing traditions with the needs and vocations of contemporary art. Participants have the opportunity to confront the unique production reality of Henraux that combines high technology with centuries-old techniques, following all the stages of processing that transform the noble material into the finished product.

The exploration of the properties and limits of marble, linked to areas of innovative creation and thinking, benefits the company itself, which then has the opportunity to test applications, models and skills in a process of virtuous contamination. Paolo Carli pointed out to me how tradition and experimentation should converge and how this vision found its shape the same year via the monumental installation by Mimmo Paladino for the Santa Croce square in Florence. For the occasion, Henraux created a monumental cross of about

80x50 meters by placing more than fifty marble blocks of different sizes, shapes and colours in front of the Franciscan basilica, helping to transform the famous square into a place for participation, spirituality and art.

The conversation with Carli was engaging, there was a harmony of vision and we decided in no time to start working together on the new edition of the Prize that was due to be held in a few weeks and of which I would be president of the jury. The winners were Francesco Arena, David Horvitz and Diego Marcon. It was particularly gratifying for us to collaborate with artists who had never dealt with marble and who, thanks to digital control technologies, were able to push their research into new territories.

My professional partnership with the company was confirmed the following year when I was asked to take over the artistic direction of the Foundation. We agreed that the new course should move along two guiding lines: on the one hand, to carry out ambitious exhibition projects in Italy and abroad and on the other to formulate collaborations with institutions, museums and artists in support of marble productions, an excellent material of great statuary. The goals were to promote knowledge, to make our contribution to relevant cultural issues and to feed a network of virtuous relationships within the international art system.

The first project, a collaboration with

14 1821>2021

Mimmo Paladino, La grande croce, 2012, Florence Photo by Veronica Gaido

1821>2021

1821>2021

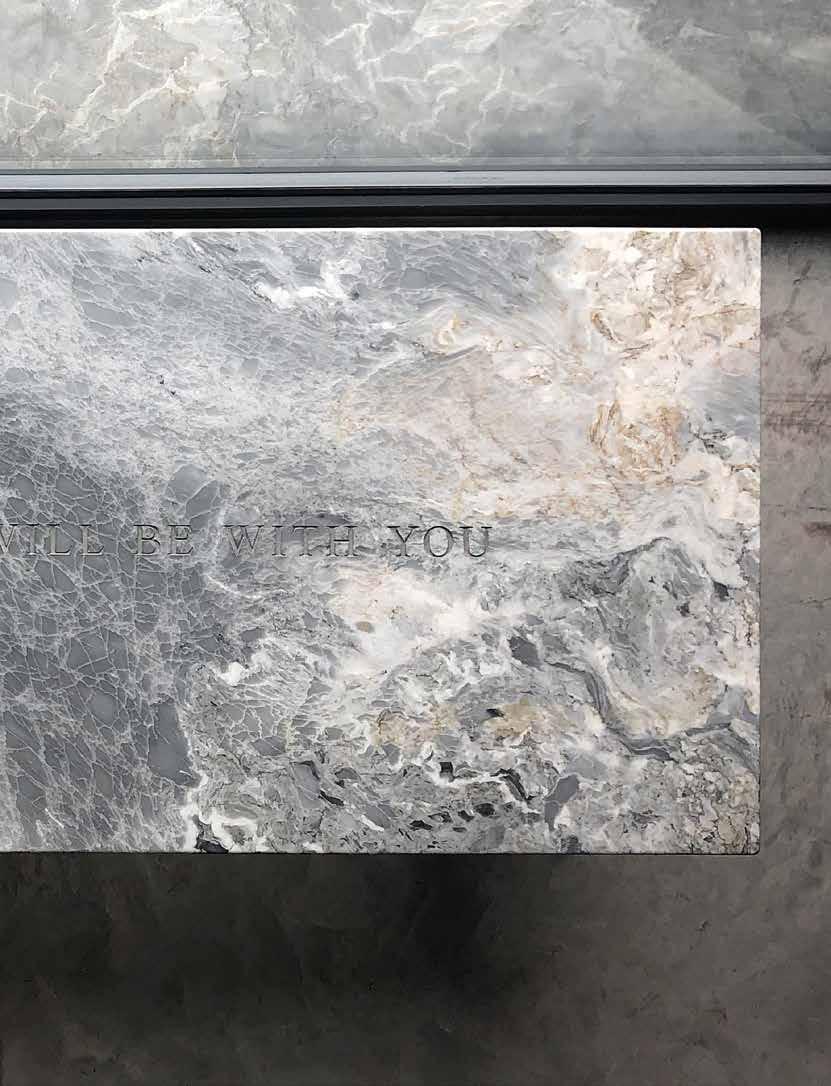

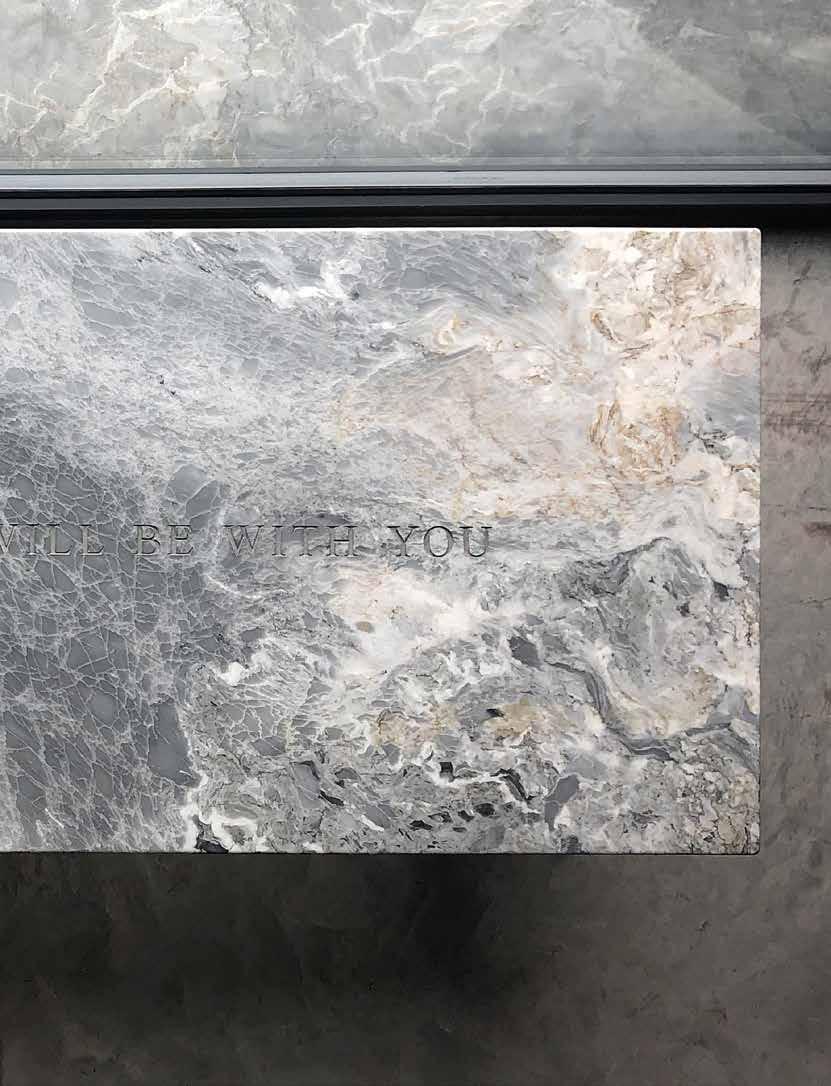

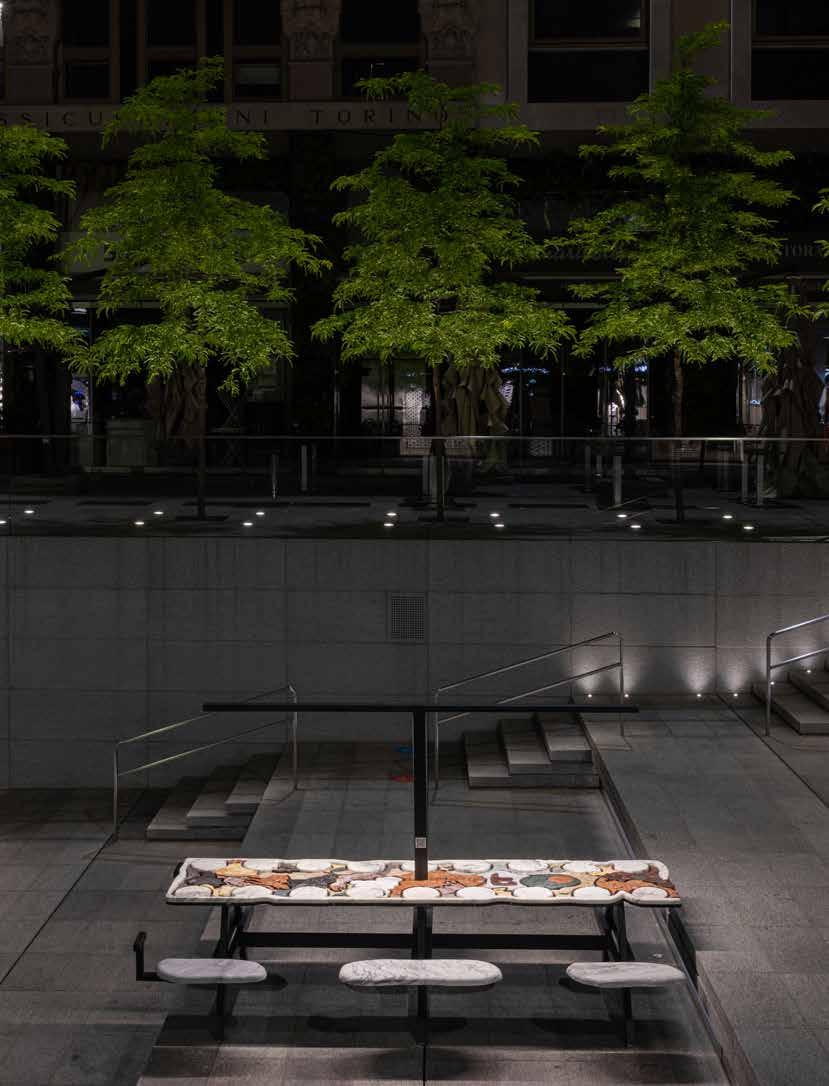

Jenny Holzer, With You, 2019 bench in Versilys marble

1821>2021

1821>2021

These collaborations and projects are often followed by acquisitions of works that enrich the Henraux Collection, which, from next year, will be accessible to the public for the occasion of the opening of an exhibition space at the Querceta factories.

the American artist Jenny Holzer on the occasion of her personal exhibition at the GAMeC in Bergamo. The work was composed of nine Versilys gray marble benches arranged in a circle in the penumbra of the Sala delle Capriate in the Palazzo Della Ragione. On each bench thoughts and verses about belonging or exclusion, by female poets and writers who dealt with gender identity issues were engraved.

A collaboration followed with Canadian artist Jon Rafman – recognized for his thrilling research on technology, digital media and their impacts on society and contemporary life – with which the Foundation created “New Age Demanded (Prince Arthur)”, a project composed of two large sculptures in Bianco Canal Grande e Bianco Macchietta marble which were permanently installed in the city center of Montreal.

The understanding of how important it was to bring more and more people closer to contemporary artistic practices prompted us to support the production of a provocative installation by the young American artist Hannah Levy, inaugurated this year in the elevated park of New York’s High Line. At the same time, in Milan, we worked with the Iranian-born artist Nairy Baghramian and the Furla Foundation

on “Misfits”, an exhibition curated by Bruna Roccasalva at GAM – Galleria d’Arte Moderna which addresses the idea of play as an educational device concerning the aesthetic experiences of inadequacy and imperfection. Also in Milan, I was able to curate “The Moral of the Story” by the Franco-Algerian artist Neïl Beloufa at the Apple Piazza Liberty amphitheatre. The public installation consists of four stations decorated with bas-reliefs and inlays of polychrome marble depicting the chapters of a fable written by the artist for his daughter. The outcome is an open, participatory space where social issues are intertwined with themes of representation between reality and fiction.

These collaborations and projects are often followed by the acquisitions of works that enrich the Henraux Collection, which, starting from next year, will be accessible to the public for the occasion of the opening of an exhibition space at the Querceta factories. The space will host historical and contemporary works, as well as the archive and a program of temporary exhibitions; the Foundation will reassert itself as an experimentation centre for contemporary sculpture which will support artists and bring together ideas, tradition and innovation: in short, the whole of Henraux’s past and future.

19 1821>2021

David Horvitz, A Sea, a Mountain, 2018

PAOLO CARLI’S HENRAUX. BEAUTY AS A MODEL OF DESIGN

BY ALDO COLONETTI

The concept of returning a culture of beauty to the world is a common thread that links the work of Paolo Carli, president of Henraux since 2003, in continuity with the figure of Erminio Cidonio. This is how the Foundation, the International Sculpture Prize and countless other activities that restore value to the industrial and cultural heritage of Henraux were born. In a conversation with our deputy director, the president explains.

20 1821>2021

Paolo Carli with Tony Cragg at Cervaiole Quarry

Photo Henraux Archive

1821>2021

22 1821>2021

“Volarearte”, 2015. Park Eun Sun’s works at Pisa airport

Photo Nicola Gnesi

Aldo Colonetti: Why do you think it is strategic for a company with a history spanning two hundred years to have a Foundation? When did the idea of organizing it arise?

Paolo Carli: It all began with a research of Henraux’s history. When I joined the company in 2003, I wanted to understand it by reading documents from the past, especially from the 1960s, concerning Erminio Cidonio’s vision for this company and its territory. Mostly, it was important to understand what he represented when he arrived in Versilia in 1957. Cidonio, upon his arrival, faced decades of history that described an industrial, economic and even social path. Reinterpreting a period, that of Cidonio, for me, was an act of foresight and a great interpretative effort towards an industrialist, but not only that, because I believe that Cidonio did not see himself only as a company man. The industry developed later, here as well as throughout Italy. Just think of figures like Olivetti, Piaggio: the project was industrial and cultural because “beauty” is not just a category of the spirit, but represents a design model that is the foundation of all our “Made in Italy”. Going back to that period, rereading that story, meant for me to put this particular sensibilty back on its feet. Art is a path that Henraux has within itself: from 1821 to today, the history of the company has always been linked with art, as large orders came from there. Once the “architects” were artists, the artist was the one who brought you the large order. Today this large order is brought to you by the architect or the designer, and art is something that makes you grow and develop memory, it is fundamental more today than yesterday from the point of view of “doing”. I was a young entrepreneur faced with an important industrial history, a company that owns important quarries, a proprietary mining business, a great brand that was about to celebrate its two bicentennial. I wondered how to reinterpret this industrial philosophy and by reading the stories of Henraux and Cidonio I realized that I had the solution under my nose: art, but not forgetting architecture and later design. Art is a challenge for us, art is creating

a unique piece; all my collaborators, from the project director to the manager who oversees the individual production activities, know that to enter into a dialogue with an artist means accepting a challenge. An artist’s piece is a unique piece, and is only finished when the artist tells you that he is satisfied with it. It is a challenge towards quality, its achievement, the tension towards perfection: thought and action, mind and hands. From history to contemporary art, the step was short and necessary, because we live in the present and above all we must always look towards a near, attainable future.

A.C.: In a company like Henraux, art is an activity in refining the processes and thoughts of the entire corporate work culture. As if to say that it is not just your choice, but it is a collective heritage that is present in the same production organization.

P.C.: I would summarise it like this: art is discipline. If you observe an artist, perhaps with an apparently disordered life, he is disciplined in his work, he is maniacal. An artist who wants to create a piece and arrive at a certain result is so obsessed with achieving the result that he loses sight of the practical aspects of everyday life. The most successful artist is, however, the most pragmatic, almost a “spokesperson” for himself; this is what this obsession is able to control a little; observing the making of art is a bit like analyzing ourselves, always suspended between what we are and what we would like to be.

A.C.: Once a project is completed, the work of art has been completed, I believe that all this experience collected inside the factory is transformed into extraordinary cultural capital. Basically, the reason and the need for the Foundation is born in this way.

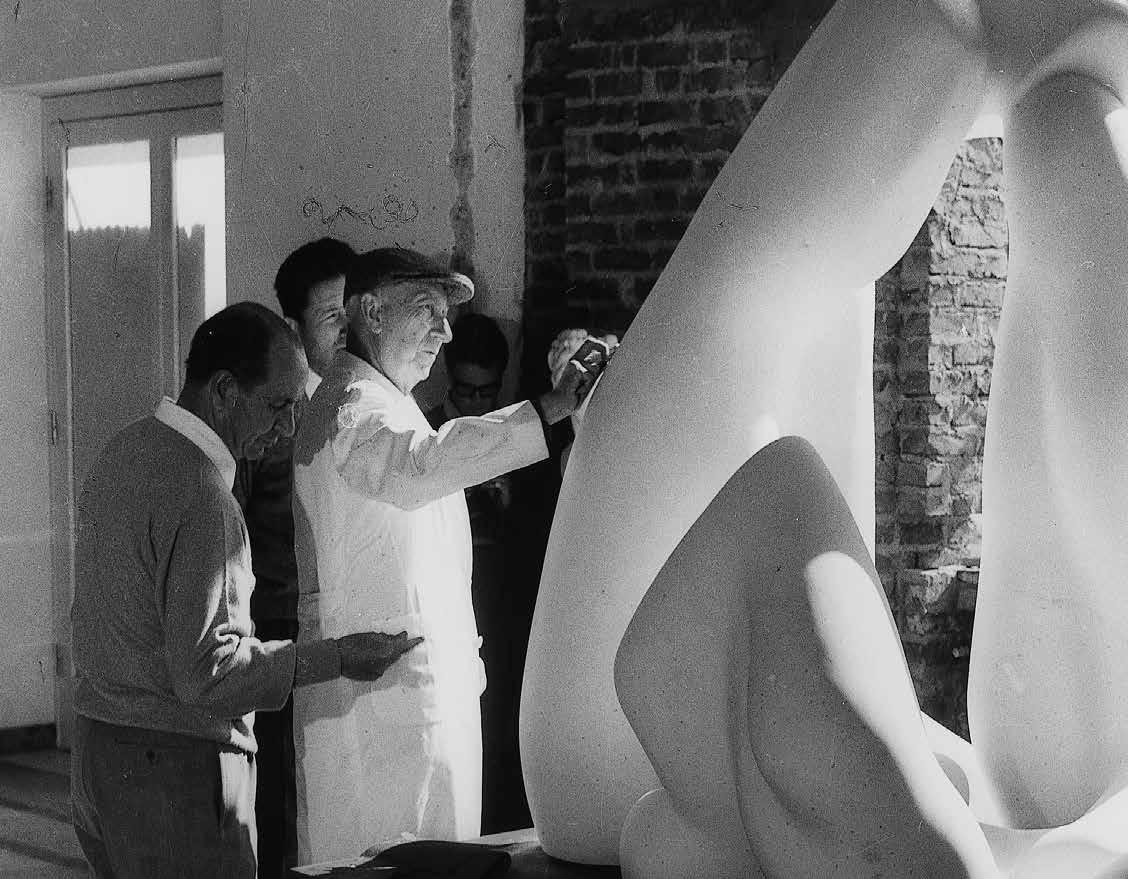

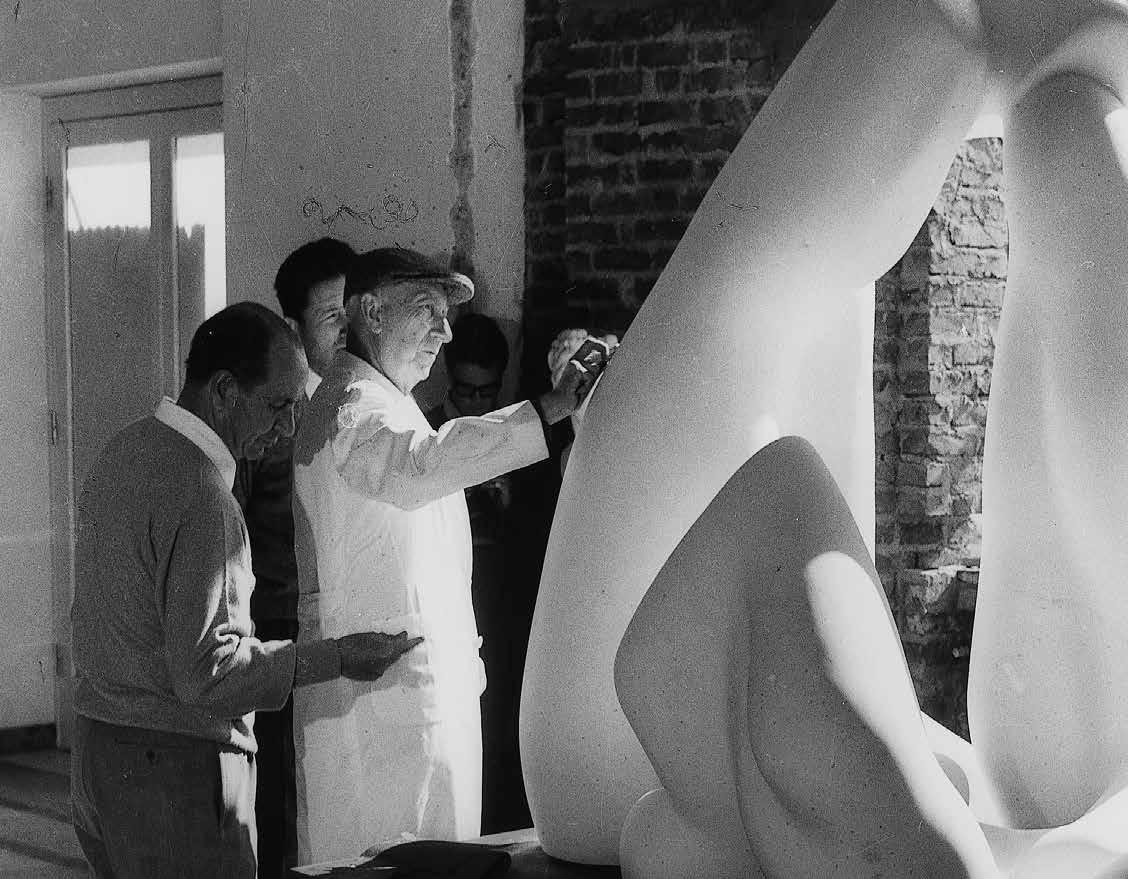

P.C.: Exactly. Collaboration with an artistic dimension within a company like Henraux represents the heart, the value of everything we do. Today we face contemporary art, but the method is the same as in the 1960s when Henry Moore arrived at the factory: he had

23 1821>2021

faith in a craftsman, who was at his side, in his case Sauro Lorenzoni, who from a small maquette, we are talking about something no more than 10-15 cm, was able to develop a sketch that would then be represented, point by point, in a set of data, then transmitted not to the machine that was still not yet there, but to a compass which through the progressive multiplication of these points, allowed, through the skilled hands of our workers, the transition from sketch to monumental form.

A.C.: The passage from the compass to the machine is important because it indicates the relationship between the instrument and the work, however, at the center there is always a man, the artist.

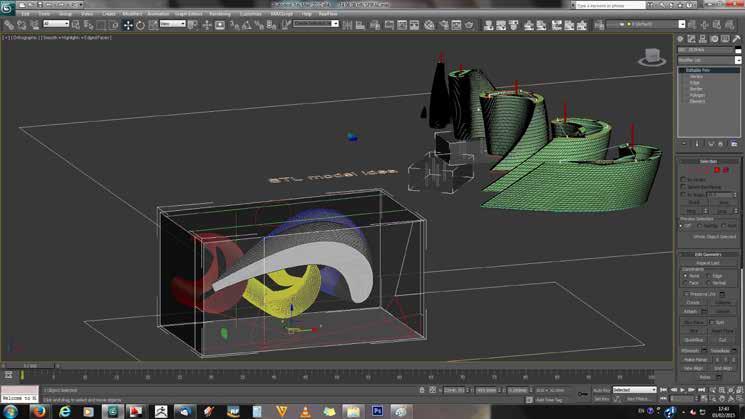

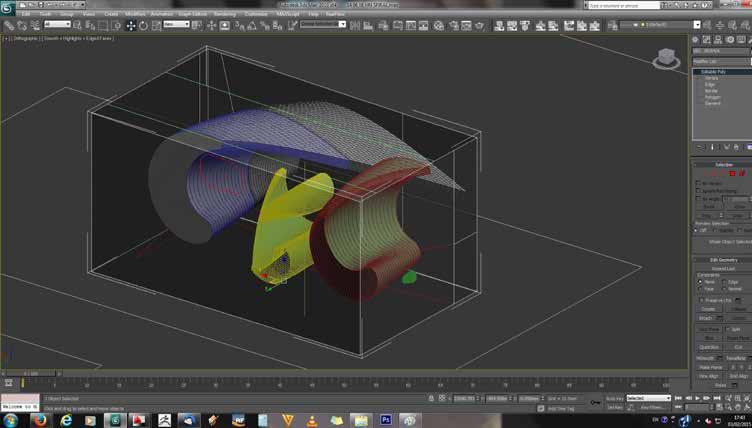

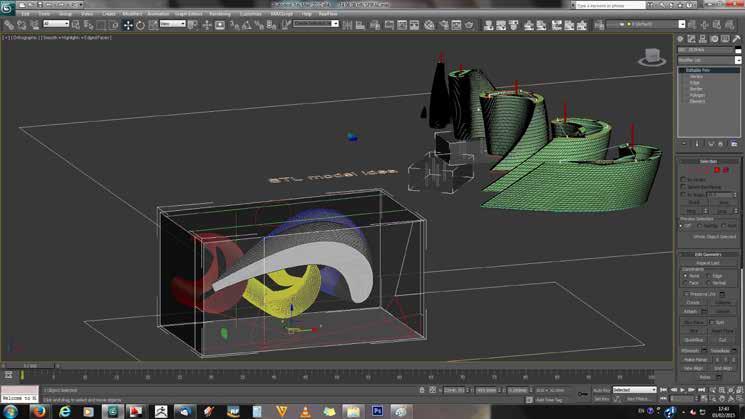

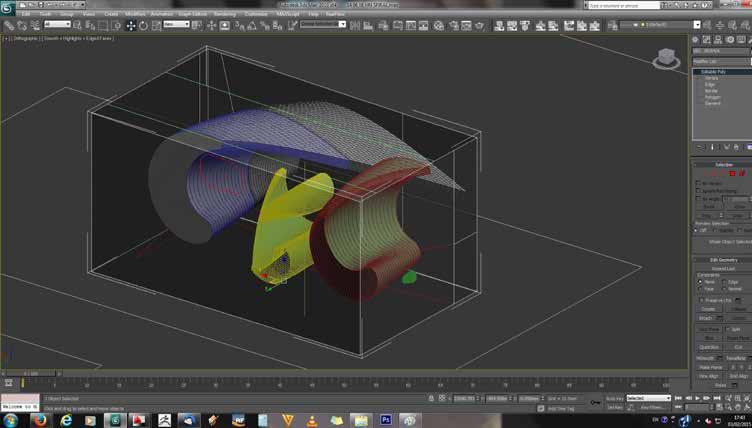

P.C.: Certainly, it was the multiplication of the point by point of the compass, and what the artist saw in small dimensions, the craftsman transferred it into something large. The artist himself then came to refine the lines. Today, however, we make these forms through technology, robotics and digital controls, but the artist’s control is always present. For this reason, another very important structure has been created in the company, made up of young people who know how to read and reinterpret this special culture which is that of 3D design and development of a certain shape; certainly the machine, but always controlled by the watchful eye of the technician and the artist. Now the forms are more and more abstract, more and more expressive, a challenge towards the unattainable. What is difficult to do today? Achieving the extremization of a form through matter: you already know that there is a material that reaches a breaking point and that breaking point is the maximum capacity for expressive development.

A.C.: At this point it is very clear how you came to think of the Foundation as a strategic element of the company’s structure: it is not just an individual choice,

it represents a future that gathers the past, always paying attention to the present, because it is here that it is the pulse of an industrial activity can be measured.

P.C.: What are the reasons behind the Foundation? First of all, because when I joined the company I realized that many resources of the past had been lost, including Cidonio’s own collection. This is how Cidonio worked: I welcome you, I make you feel the marble, I make all my structure, the raw materials and all the rest available to you, but at least leave me something! And this something was a work of art: so he had created a unique collection of absolute beauty! Others are inventing such a thing today, while we do not have to invent anything: Henraux has a heritage of two hundred years that arises from a collaboration with the great art of the moment, starting from the nineteenth century, passing through the twentieth century and reaching up to the 2000s. The Foundation was necessary to give an institutional form to a single story. This meant that to form the foundation it needed an operational structure within it, whether it is one or two people who animate, feed and coordinate all the activities on a daily basis. Our events are now well known, starting with the International Sculpture Prize, which I truly wanted, thanks also to the collaboration with Philippe Daverio. All I did was revisit Cidonio’s experience, Daverio accompanied me, first discussing and then trying to dissuade me from this crazy idea of mine, then, given my stubbornness in carrying it out, exhausted, he said yes. And from there it all started: in 2012 the Prize. We brought young artists back to reinterpret marble, an extraordinary but very difficult to work with.

A.C.: The project is also a sign of the attention given by a private company towards its reference territory. In your opinion, has this plan towards the context, in such a way as to return what Henraux has received in 200 years from such an

Henraux has a heritage of two hundred years that arises from a collaboration with the great art of the moment, starting from the nineteenth century, passing through the twentieth century and reaching up to the 2000s. The Foundation was necessary to give an institutional form to a single story.

24 1821>2021

Above, robot working at the Henraux workshop

Photo by Nicola Gnesi

Below, Paolo Carli with a craftsman: the hand refining phase at the Henraux refining workshop

Photo by Nicola Gnesi

25 1821>2021

1821>2021

1821>2021

The site of the Henraux Foundation

Photo by Neri Casamonti

extraordinary and unique place, been understood?

P.C.: When I considered the Foundation, I immediately chose the path of a mixed system, something public and private: Henraux spa, the Municipality of Seravezza, the Municipality of Stazzema, the Municipality of Forte dei Marmi and the Province of Lucca, choosing strong local roots. Unfortunately, it was not fully understood. I always trust in a future, mainly in young talents, of which, as you can see, I make a lot of use, both in terms of new hires, some of which come from our extraordinary territory, and in relation to collaborations with designers, architects and artists. Henraux must pass on its story, it is an obligation that I have as an entrepreneur who has decided to undertake this great challenge but also as an “inhabitant” of a unique place in the world.

I made a commitment to pass this on to new generations, to pass it on for more than its two hundred years. Today we represent a company aimed at an international market. I believe that despite the current crisis, Henraux possesses such human energy, much superior to financial energy, that it allows us to look to the future with optimism.

A.C.: Your Foundation, by statute, does not produce profits directly, but indirectly constitutes an element of value that can be found in the production capacity, in selling to the world a unique material that is not only symbolic of a history but also of a territory that the whole world envies.

P.C.: If the company knows how to perform, it must do so off the artistic path; the artistic paths are those that enrich us, that nourish us, so it is clear and fundamental that this cultural heritage must be defended. I do everything I can do to defend a company with two hundred years of history; a large internal production with large vertical production chains. I would like to be a model, but I must also say that our commitment is not always recognized. We have a heavy and cumbersome bureaucratic system. We represent legality, I want to

say, like other companies. Henraux has certified financial statements for at least eight years, and therefore we represent true legality, not being protected or not being relieved of all this bureaucratic heaviness.

A.C.: Moving on to the bicentennial, a goal closely linked to everything we have mentioned.

P.C.: For me, the bicentennial is very important milestone. When I acquired the company nineteen years ago, 2021 was far, far away. We have arrived at an extremely sad and dramatic moment for the entire community, worldwide. I see great potential within this bicentennial; the company, despite the difficult times it had to overcome in 2020, has shown great resilience. We are facing a 2021 in which we will not be able to best express our history; we have decided to postpone the celebrations until next year, however we have already started this year with a series of projects, because 200 years only comes once in a lifetime.

I am very proud, because we work with great humility. We won’t have big celebrations. The first commitment is to put this large collection in order, in such a way as to connect past history with the activities carried out in recent years, highlighting an openness to the contemporary.

A.C.: Can we hope that in 2022 the State will be able to be present, to show with a symbolic gesture, which never remains only symbolic, the outset of another political, and above all ethical and cultural path?

P.C.: Let’s hope so. Meanwhile, we are working to make this happen. Everything I have done in these twenty years goes in that direction: the Prize, the Foundation, the presence on the territory through exhibitions, such as those organized in the airports of Pisa and Florence with the VolareArte event, the sculpture by Emilio Isgrò “The Seed of Altissimo” which was produced for EXPO 2015 and later placed in Milan in front of the Triennale headquarters, the republication of the

28 1821>2021

magazine “Marmo”, this year we have already reached number 10. Publishing a company magazine with this diligence represents a sign of continuity, as Cidonio had guessed: it was the first magazine that, going to the desks of the best international architects, represented marble as a product to be cultivated, understood and nurtured. With “Marmo” we want to give the “culture of beauty” back to the world.

A.C.: Marble a part for the whole; marble is synonymous with Henraux, and in

the imagination of the world, Italy has some elements that characterize it –design, fashion, food, art, architecture – and marble crosses them all because it belongs to nature and to culture in its highest expressions. One only needs to think of Michelangelo.

P.C.: In fact, the subtitle of “Marmo” is: Architecture Design Art, thus meaning an interpretation of forms and spaces in a broader sense, where these three disciplines interact with each other and intertwine, maintaining their own identity and then returning together.

29

1821>2021

With “Marmo” we want to give the “culture of beauty” back to the world.

External view of the Henraux Foundation

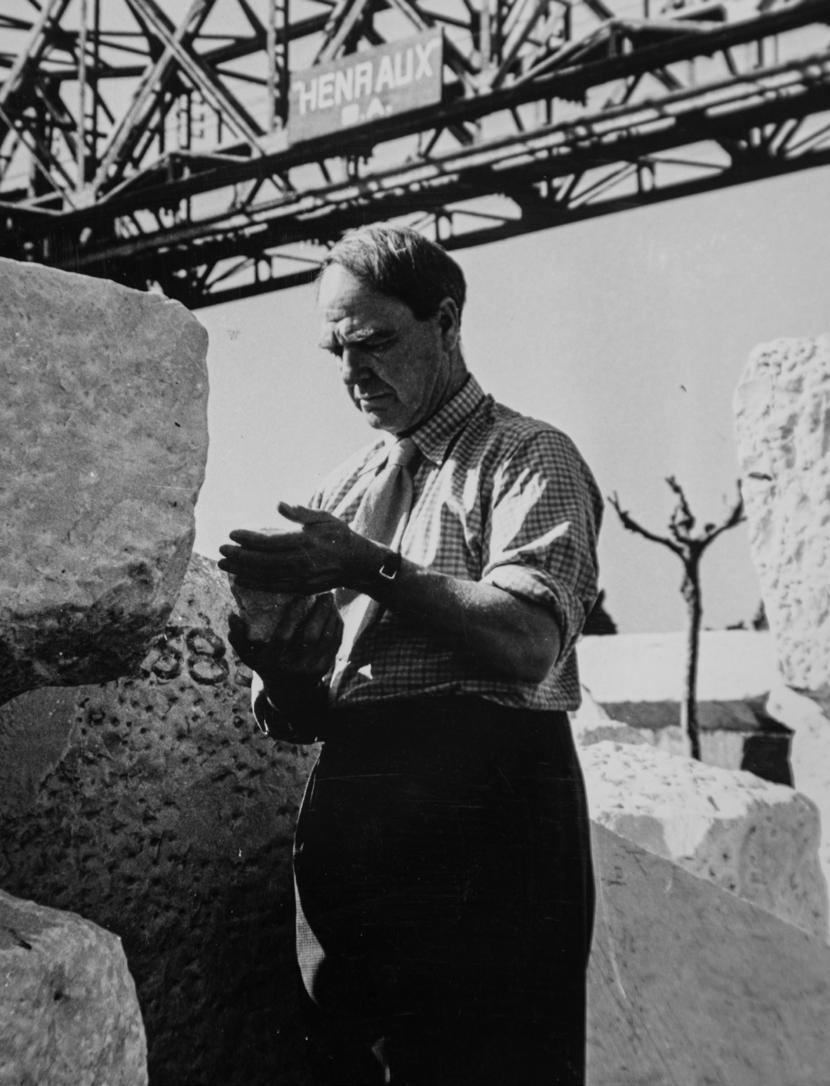

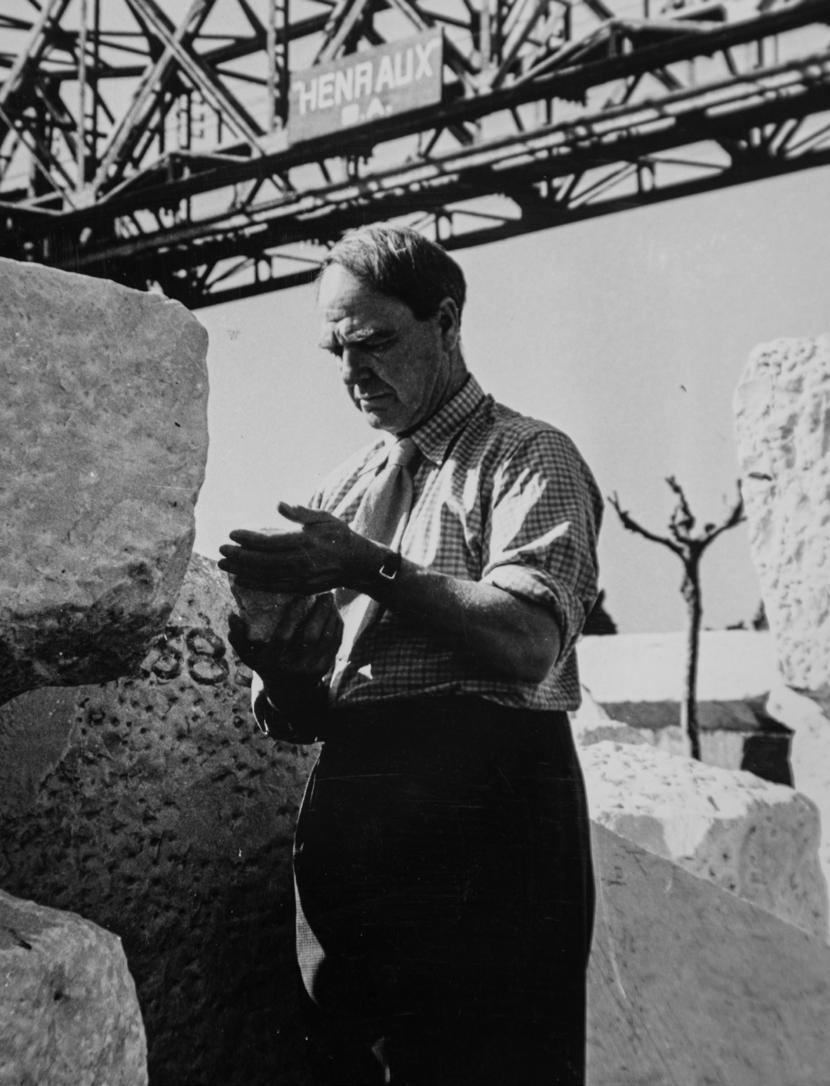

Henry Moore at the Querceta establishment

HENRAUX IN THE INTERNATIONAL ART SCENE. A STORY IN THE TELLING

BY LARA CONTE PHOTOS FROM HENRAUX ARCHIVE

A time of utopia and research for Henraux has arrived with Erminio Cidonio, through the involvement of great sculptors and young artists and the promotion of contemporary sculpture, of which the establishment of the magazine “Marmo” itself constitutes a fundamental part. It is a project driven not by pragmatic intentions but by an authentically enlightened vision.

30 1821>2021

1821>2021

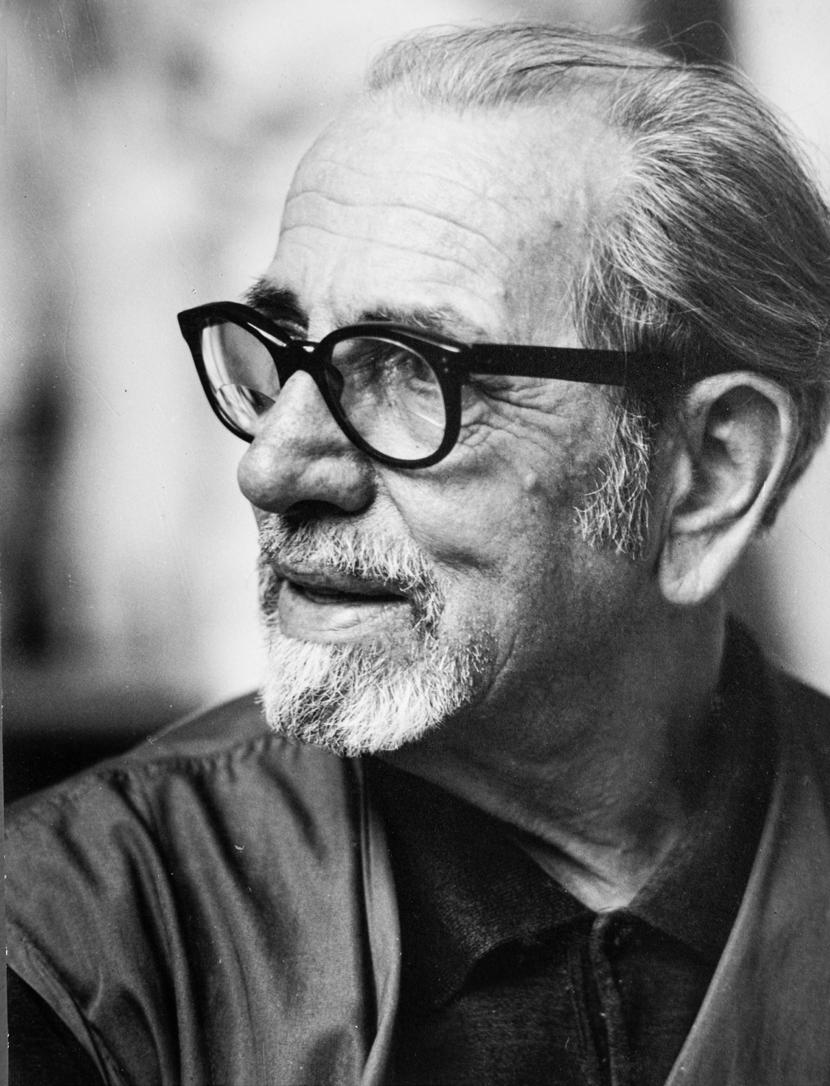

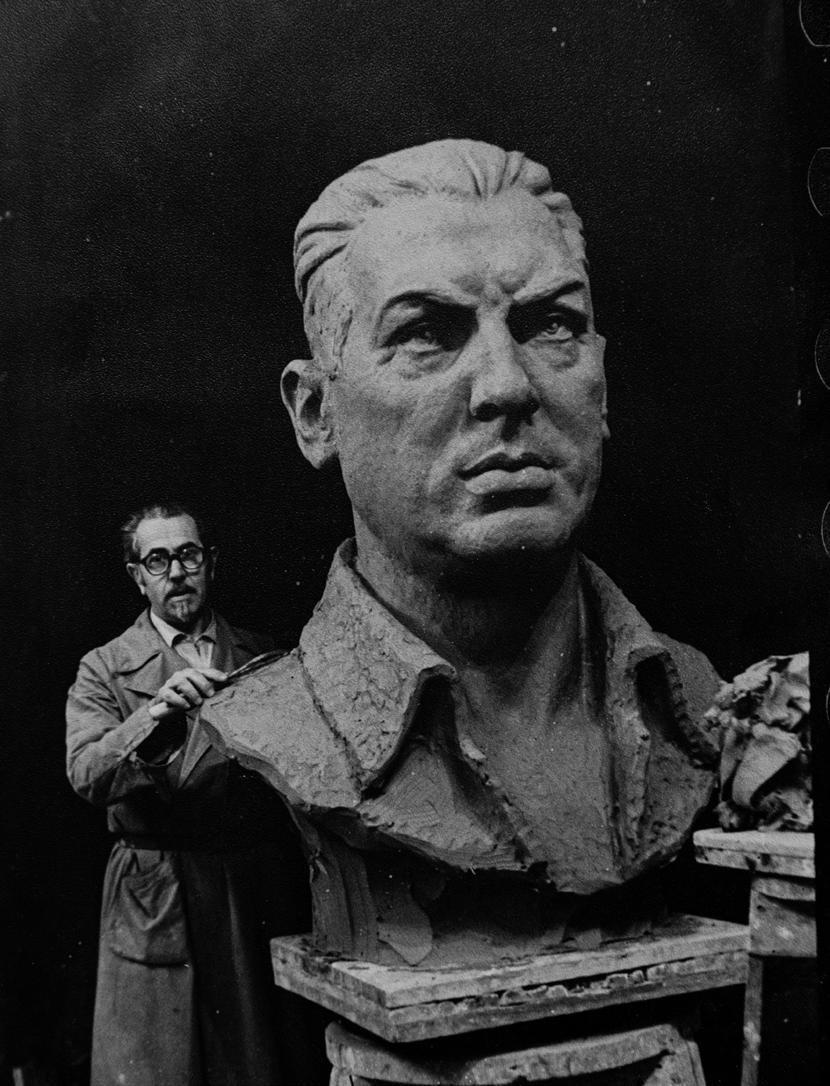

Leone Tommasi

Some crucial background

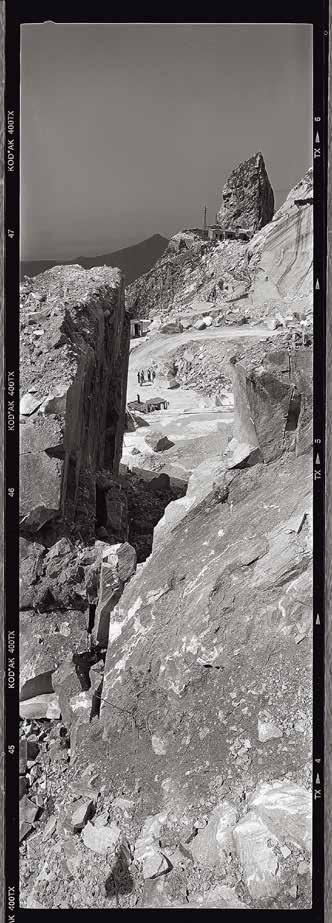

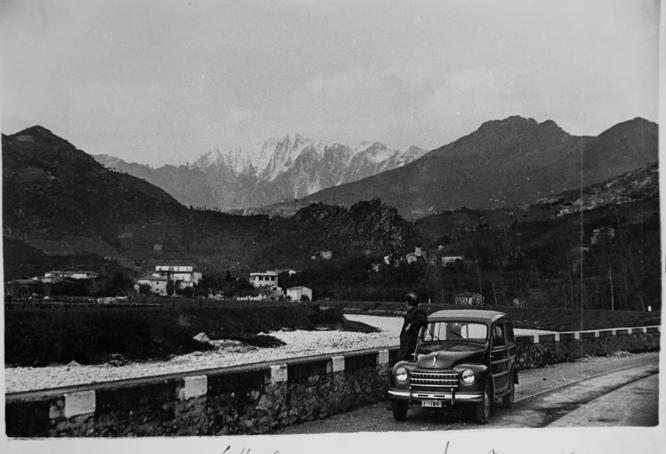

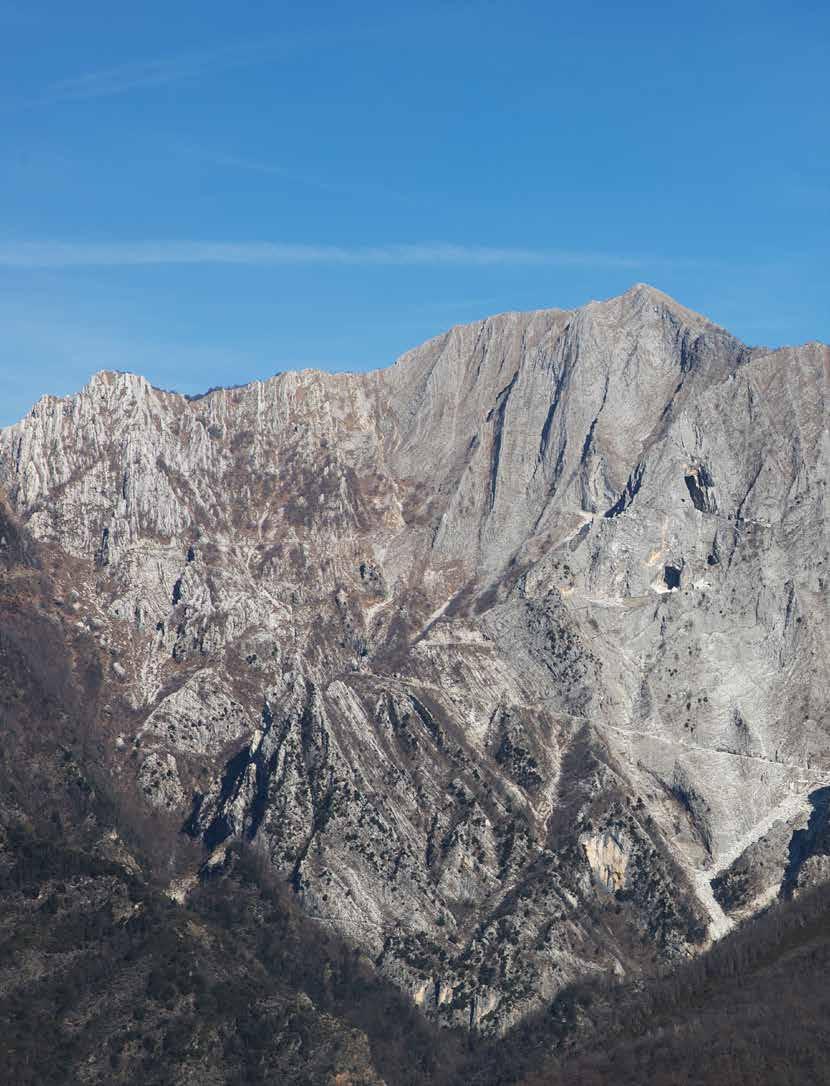

“I went to Querceta, near Forte dei Marmi, in Italy, for the Unesco sculpture. Querceta is a small village at the feet of the Carrara mountains. For me, Monte Altissimo is enormously exciting and fascinating. It is there that Michelangelo spent two years of his life extracting marble. The Henraux Company owns the Monte Altissimo and trades marble and stone all over the world”1.

This is how Henry Moore remembers his first encounter with Versilia; a meeting that marked the beginning of the artist’s collaboration with the Henraux company. The fortune and impact of Moore’s sculpture in Italy, consolidated by exhibitions and increasing attention in the specialist and popular press starting after the war, became even more apparent in the second half of the 1950s. It was in 1956 when, having obtained the prestigious commission for the creation of a large sculpture for the Unesco headquarters in Paris, Moore chose to create his “Reclining figure” in Roman travertine. Hence his decision to go directly to Versilia, where he could not only choose the material, but above all, he could benefit from the technical collaboration of skilled local artisans.

Moore frequently stayed in Querceta between 1957 and 1958, so much so that, as Davide Colombo and Giorgio Zanchetti recently highlighted, “monumental stone sculpture became for Moore ‘an activity inextricably linked to Italy for the rest of his life’”2

At first, local artisans found themselves unprepared to face dialogue with the forms of contemporary plastic art research. What must have generated amazement was the sculptor’s decision to use Roman travertine instead of white marble. The bemusement grew even more when Moore showed the local workers “a plaster model no larger than twenty centimetres, from which a statue of over four meters was to be made”3, this implied a revolution in traditional processing methods.

It was this “challenge”, so well received by the Henraux company and its collaborators, which played a decisive role in the fate of the historic company and for the future of the Versilia area tout court

Erminio Cidonio’s plan

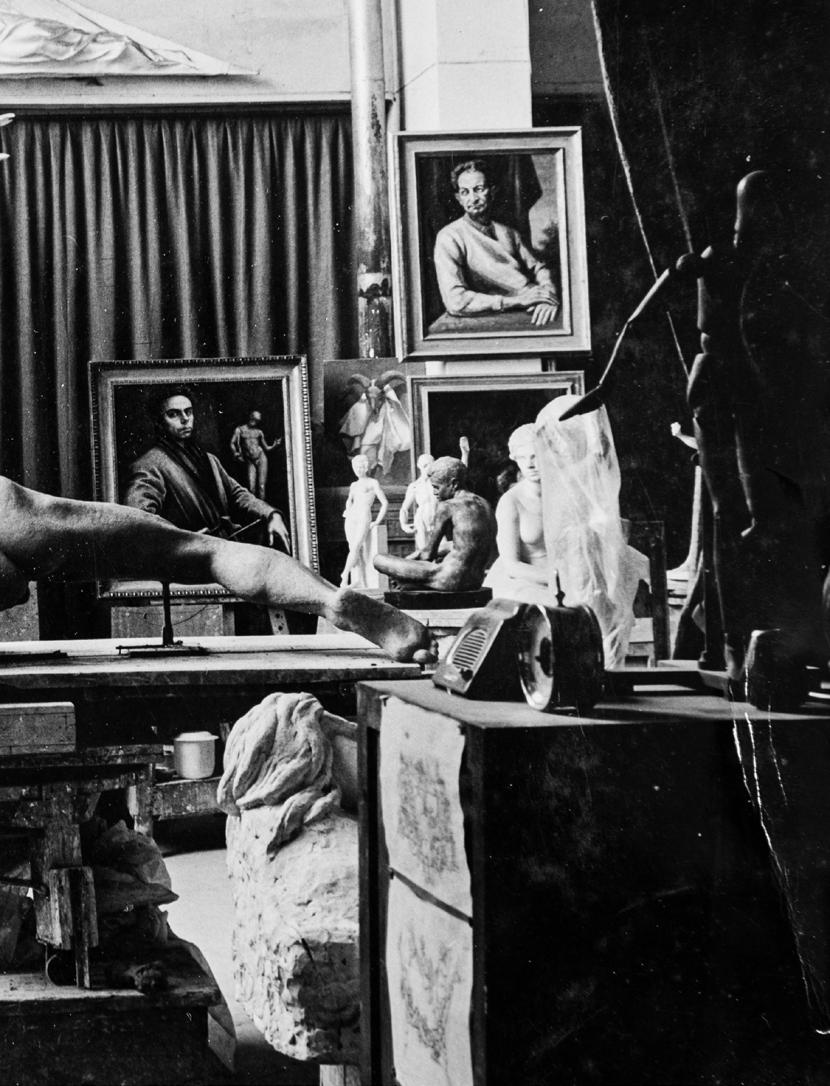

Henry Moore’s presence at Henraux can therefore be considered as the background to an adventure that found shape during the 1960s, assuming an articulated physiognomy. This was thanks to the foresight of the then CEO of the company Erminio Cidonio4, who managed to give life, in just a few years, to a project promoting contemporary sculpture of great international resonance, involving established sculptors alongside young artists, intellectuals and professionals gravitating in the world of art, architecture, design and of restoration.

Erminio Cidonio realized that the way to give new vigour to the marble sector was precisely to promote the use of marble in the field of contemporary sculpture, architecture and mass production, involving great masters and young artists who attended the Henraux workshop, taking advantage of the collaboration of local artisans. It was only in this way that marble could return to the centre of contemporary debate, freeing itself from the heavy fascist legacy and from all the monumentalism identified with the ideology and image of the regime. According to the recollections of Pier Carlo Santini, Cidonio “was not happy to share the practical dress, the arid and calculating pragmatism of his colleagues [...]. His was a dissent illuminated by acute and precise intuitions, supported by his constant enthusiasm, aimed at the cultural and technological renewal of the environment in which he found himself operating. For Cidonio, doing research meant being passionate about any proposal or project that looked to the future, promoting initiatives that could not have immediate productive feedback, encouraging experimental methods and methods, giving great space to utopia”5

A utopia – Cidonio’s – which certainly drew inspiration from the most modern examples of industrial entrepreneurship aimed at combining production, social and cultural commitment, in that temporal curvature that extended from postwar reconstruction to the years of the economic miracle.

For the realization of his original project, the entrepreneur surrounded himself with

32 1821>2021

“For Cidonio, doing research meant being passionate about any proposal or project that looked to the future, promoting initiatives that could not have immediate productive feedback, encouraging experimental modes and methods, giving a great space to utopia”.

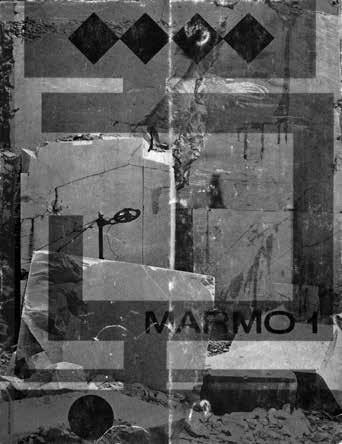

skilled collaborators and declined a more diversified plan, giving importance to the theoretical side and practical impact, to the international image and local identity. In this sense, the idea of founding a magazine as a receptacle of experiences and a place for theoretical elaboration seemed to be the first useful step in describing and disseminating the project. During 1962 Cidonio came into contact with the publisher Bruno Alfieri6, who accepted the job of editing “Marmo”, an international art and architecture magazine promoted by Henraux. From that moment on, he forged debate and a network of relationships that allowed other aspects of the project to bring fruit. Alfieri in turn proposed Pier Carlo Santini and Giuseppe Marchiori as collaborators and interlocutors of the project. The latter, together with the publisher, was promptly involved by Cidonio in the design of a sculpture seminar for young artists and in the organization of a contemporary sculpture museum to be set up in Querceta, at the Henraux7 The goal was precisely to bring together the most important personalities of international plastic art research in Versilia, making sure that through their works there remained a trace of their passage.

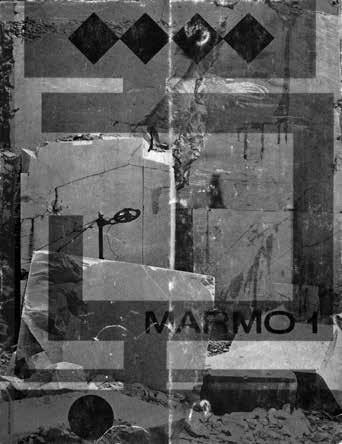

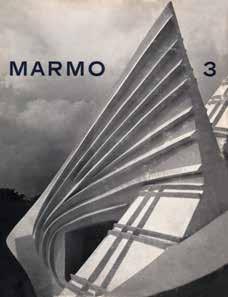

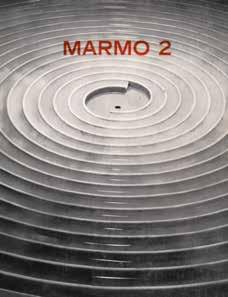

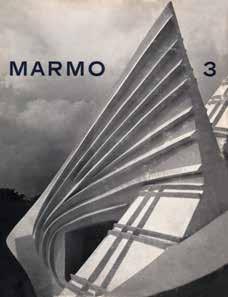

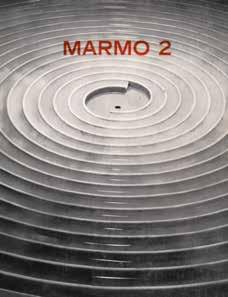

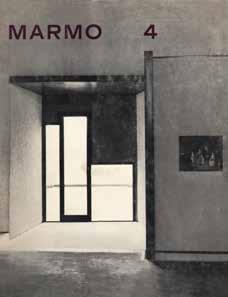

“Marmo” magazine

According to the agreements between Cidonio and Alfieri, the magazine “Marmo” was to publicise the projects carried out by the company alongside collected critical contributions on sculpture, architecture and design, in such a way as to “create an international, non-sectarian platform of modern culture, that looked towards the future”8. It would present “modern creations by artists, architects and designers, in any material, as long as they were screened through a filter of art and technical criticism”9. Marble is therefore the dominant, but not exclusive, theme of the publication.

Alfieri edited the first three issues, printed annually from 1962 to 1964; the direction of the fourth issue, which appeared in 1965, and of the fifth, which

came out – after an interruption of a few years – in 1971, was instead taken on by Pier Carlo Santini.

The first four issues collated reflections from art historians, critics and specialists from the many disciplines covered. As far as sculpture was concerned, the diligent presence of Giuseppe Marchiori should be noted, who wrote in-depth essays on the great sculptors who, with thanks to him, arrived at Henraux. In addition to the already consolidated presence of Henry Moore, which he recounted over the years, the contributions dedicated to Hans Arp and Henri Georges Adam10 should be noted. Excerpts from a diary, projects and sketches by Le Corbusier, Giovanni Michelucci and Alvar Aalto enrich the pages dedicated to contemporary architecture11. Issues relating to archaeology, the history of architecture and restoration were addressed by Piero Sanpaolesi, Marco Dezzi Bardeschi, Brunetto Cartei, Licisco Magagnato and Pier Carlo Santini, who also edited the pages designated for design12.

Undoubtedly, the publication’s intentions were clarified by the second and third issues, pressed, respectively, in November 1963 and December 1964. They are made up of historical-critical contributions, of a column entirely dedicated to marble, entitled “Marmorama” and a “Henraux Bulletin”. This last section illustrated the projects conducted and completed by the company in that fruitful two-year period; projects ranging from architecture to restoration, from industrial design to contemporary sculpture. “Marble 2” presented a piece on the Cavalieri Hilton Hotel in Rome (whose design was taken up by Franco Albini, Franca Helg, Ignazio Gardella and Melchiorre Bega), in which Henraux marble was widely used in flooring and furnishings. An interview by Giuseppe Patané with Ugo Blätter, also published in the second issue of the magazine, documented the construction of the floor for the portico of San Pietro designed by Giacomo Manzù, whose work was conducted by the “Reconstruction and Sacred Art” department of Versilian society13. “Marmo 3” provided in-depth information on the reconstruction of the Abbey of Montecassino destroyed by

33 1821>2021

1821>2021

Henraux craftsmen pose the large pavement of the portico of San Pietro designed by Giacomo Manzù

the bombs of the Second World War, the largest restoration project in which Henraux collaborated and one which saw the company’s workers engaged for more than a decade14

The project of the Centre for contemporary sculpture

Starting from 1963, Cidonio’s project, aimed at creating a centre for contemporary sculpture in Querceta, took on a well-defined physiognomy, as was also testified by the magazine, in which the sculpture seminars organized by Alfieri and Marchiori were advertised. Seminars which were held in the summer months of 1963, 1964 and 1965, and the presence of the artists who, in those years, visited Henraux are also documented.

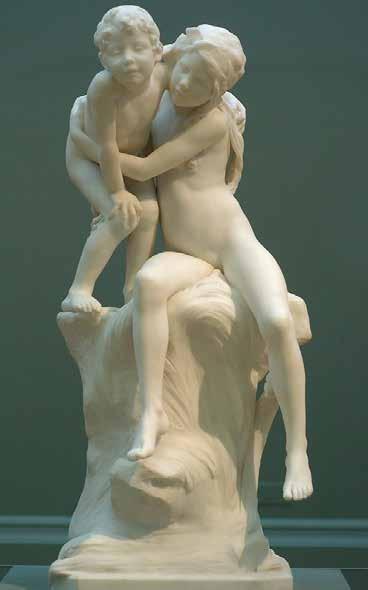

The young sculptors sent to the seminars had the opportunity to work with marble (each artist was provided with the material needed for their needs) and to benefit from the technical assistance of local workers. According to the provisions of the Regulations, the artworks created during the seminars would remain the property of the company and would form a collection of sculptures, subject to the opinion of the jury15. The intent was to “guide young sculptors into the terrain of professional maturity, in working with materials that only allow a direct and intimate conversation between the work and the artist, freed of any forced intellectualism”16. The artists chosen for the first edition were: Marisa Mauri, Silverio Riva, Paolo Icaro and Guido Pinzani; for the second: Fumio Otani and Antoine Poncet; and for the last: Juan Dries, Bruno Raspanti and Aldo Dezza. For some, that experience turned out to be a brief parenthesis within their creative paths that continued towards completely different experiments, for others it constituted the beginning of an assiduous collaboration with the company and a lasting frequentation of Versilia. This is the case, for example, of Antoine Poncet.

1964 was a crucial year for the development of the project linked to contemporary sculpture. In fact, in attendance were Henry Moore, Hans Arp,

Henri Georges Adam, Isamu Noguchi, François Stahly and Emile Gilioli. As Marchiori observes, “the interest in Henraux’s cultural initiatives, relating to the use of marble in the century of iron and autogenous welding, manifests itself in artists of very different, indeed often antithetical, backgrounds”17. Noguchi planned a rearrangement of the garden in which the first group of sculptures of the museum were to be set up and of which – according to Marchiori himself –there was already a lot of talk in the international world of the arts. During the summer, Arp visited Querceta to put the finishing touches to the “Paysage Bucolique”, the great sculpture with which the Versilian company chose to be represented at the Milan Fair in 1964. We read in “Marmo”: “Arp, wearing a white doctor’s coat, started to smooth a curve that seemed too accentuated to him with sandpaper and a very fine rasp. Arp almost caressed his sculpture and the raised white powder made the artist’s spiritual face appear more lunar than usual. White on white in a face, which takes on unexpected expressions of curiosity, detachment, irony, spiritual harmony, and sometimes even farcical buffoonery, like Dada”18

When Arp left for Meudon, François Stahly arrived at Henraux, who would later send a sketch to be translated into marble for the museum. Artworks by Alicia Penalba and Georges Vantongerloo, the historical founder of De Stijl, were also underway. The company’s expert workers, who had also recently finished Adam’s monument for Vincennes, carried out the marble transposition for the collection.

Henraux was becoming “a European sculptural workshop” 19. During the summer of 1965, the appearances of Antoine Poncet, Alicia Penalba, Emile Gilioli, Isamu Noguchi, Pietro Cascella and Henri Georges Adam were recorded.

“This is Adam who is finishing the great wall for the castle of Chantilly –reported Marchiori in “Marmo”– A wall made up of barely hewn elements, with deep incisions, of beautiful geometric

35 1821>2021

warping, intersecting lines, apparently random like graffiti. The boulders are of different colours and often almost natural shapes. They will be placed on a body of water”20. And it was precisely to the great Adam fountain for Chantilly Santini that he dedicated an in-depth essay – also published in “Marmo 4” – accompanied by splendid photographs by Ugo Mulas, in which he described the process of the plastic art realization of the monument, for the creation of which the sculptor had fully exploited the technological contribution of the Versilian company’s machinery, creating a perfect integration between the work of the artist, the workers and the machines21

After the summer of 1965, a period of intense change loomed for the Versilian company.

Financial problems arose concerning the project dedicated to contemporary sculpture, presumably linked to the publication of the magazine and the organization of seminars.

In August 1965, the publisher Bruno Alfieri ended his collaboration with the company. The direction of the fourth issue of “Marmo”, published in December 1965, was in fact taken over by Pier Carlo Santini.

In January 1966, Cidonio, who had already resigned from the posts of administrative director and technical director in May, decided to leave Henraux. The position of managing director was consequently taken by Giuseppe Formai.

Unfortunately, the publication of the magazine was suspended after Cidonio left Henraux22. This change of direction,

36

Erminio Cidonio with Hans Arp at work on a sculpture

Photo by Ilario Bessi

1821>2021

Right, Joan Miró, Oiseau solaire, 1968, white marble

The publication of the magazine was suspended after Cidonio left Henraux. This change of direction managed to ensure continuity for the sculpture museum project, thanks also to the collaboration of Giuseppe Marchiori.

however, managed to ensure continuity for the sculpture museum project, thanks also to the collaboration – albeit less assiduous than in previous years – of Giuseppe Marchiori. During the second half of the 1960s, internationally renowned artists, therefore, continued to frequent the Henraux workshop and sent works for the museum. A review of the correspondence preserved in the Company’s Historical Archive allows us to draw up a rather detailed list of the sculptures that, in those five years, were added to the collection, and also to define the methods of acquisition of the same: in some cases, the artists authorized

Collectable events and new perspectives

At the beginning of the seventies, Henraux’s adventure in the field of contemporary sculpture was about to come to an end. Two events set the chronological boundaries of that exciting season: the publication of the latest issue of “Marmo”, released in November 1971, after a few years’ silence, and the exhibition held in the Cortile d’Onore of Palazzo dei Diamanti in Ferrara in 197227, in which the sculptures of the Versilia collection could be appreciated in all their splendour. On that occasion, works

the execution of a copy of the work that was in progress at the laboratory; in other cases, they expressly donated their own plastic ideas, either free of charge or in exchange for the supply of materials. Among the sculptures gathered in the collection in those years, we can mention, “L’oiseau solaire” by Joan Miró23, “Unidades yunta” by Pablo Serrano24, “Rencontre dans l’espace” by Maurice Lipsi25 and “Ghibellina II” by Giò Pomodoro26

by Hans Arp, Giovanni Benvenuti, Carmelo Cappello, Pietro Cascella, Nino Cassani, Lynn Chadwick, Gaetano Di Martino, Joan Dries, Richard England, Agenore Fabri, Maurizio Giannotti, Rosalda Gilardi, Emile Gilioli, Gigi Guadagnucci, Maurice Lipsi, Juan Mirò, Luigi Mormorelli, Rosario Murabito, Isamu Noguchi, Maria Papa, Alicia Penalba, Giò Pomodoro, Antoine Poncet, James Ritchie, Branko Ruzic,

37 1821>2021

38 1821>2021 The

covers of the first five issues of “Marmo”

NOTES

1 “Henry Moore in Forte dei Marmi and Versilia. The man, the artist”, exhibition catalog (Forte dei Marmi, LU, Civic Gallery of Modern Art, 1998), Pisa 1998, p. 9.

2 D. Colombo, G. Zanchetti, “Moore: voyage in Italy”, in “Henry Moore” exhibition catalog (Rome, Terme di Diocleziano, 2015), edited by C. Stephens and D. Colombo, Tate Electa, Milan 2015, p. 166.

3 Testimony of Vando d’Angiolo, in “Henry Moore”, quote. p. 47.

4 Erminio Cidonio, born in Rocca di Mezzo (AQ) on 13 October 1905, was appointed Henraux’s delegated administrator on April 29, 1957. On May 31, 1961, he assumed the position of general manager. The documents kept in the Henraux Historical Archive [ASH] certify that, on 30 May 1963, he held the positions of managing director, general manager and technical director.

5 P. C. Santini, Introduction, in “Marmi nel parco”, exhibition catalog (Marina di Pietrasanta, LU, Parco della Versiliana 1984), edited by P. C. Santini, Pietrasanta 1984, p. 16.

6 Much of the information on the “Marmo” publishing project is derived from a conversation with Bruno Alfieri on 25 March 2004 in Milan, at Automobilia s.r.l. - Society for the History and Image of the Automobile. For a study of the “Marble” magazine, see L. Conte, “The ‘Marble’ magazine”, in “From ‘Marmo’ to marble. 1962-1972”, exhibition catalog (Seravezza, LU, Palazzo Mediceo, 2004), edited by A. Tosi, with the collaboration of L. Conte and A. Salvadori, Seravezza 2004, pp. 25-33; L. Conte, ‘Marmo’: an international magazine of the sixties, between architecture, sculpture and design”, in “Marmo”, a. I, December 2016, pp. 20-28.

7 Thanks to a letter kept in the Marchiori Archive, published by Anna Vittoria Laghi, it was possible to set the beginning of the collaboration between the critic and the entrepreneur of the Versilian company in July 1962. For an in-depth study of the relationship between Erminio Cidonio and Giuseppe

Giannetto Salotti, Adolfo Saporetti, Pablo Serrano, Carlo Sergio Signori, François Stahly, Alina Szapocknikow, Cornelia Von Den Stein, Georges Vantongerloo and Giorgio Zennaro were exhibited. Shortly thereafter, this organic and refined collection would be dismantled. In fact, on December 31, 1973, as many as twentyfive works were purchased by the Italian Commercial Bank and left Henraux definitively in July 1976. Thanks to the actions of Pier Carlo Santini, some sculptures made a temporary reappearance in Versilia in 1984. The critic from Lucca curated the “Rassegna Marmi del Parco” at the Versiliana Park, hypothesizing a possible museum itinerary for the exhibition of the Versilian collection, created in collaboration with the architect Giuseppe Davanzo.

In 2000, part of the collection was exhibited as part of the 10th International Biennial of Carrara, in a section designated by Anna Vittoria Laghi. A further moment of study was provided by the exhibition “From ‘Marmo’ to Marmo. 1962-1972” curated by Alessandro Tosi with the collaboration of Alberto Salvadori and the writer, held in 2004 at the Palazzo Mediceo in Seravezza. On that occasion, an exhibition itinerary was proposed that privileged the presentation of works still preserved in the collection of the Henraux company (including sculptures and sketches), attending the future museum reorganization project promoted by the Henraux Foundation to give the proper visibility to these works and the visual narration of a story that outlines the identity of the company in the global economic and cultural scenario to the present day.

Marchiori, see A. V. Laghi, “Cidonio, 1963-1965: chronicle of an utopia”, in “X International Biennial City of Carrara. The primacy of sculpture. The Twentieth Century in Carrara and Surroundings”, catalog of the exhibition (Carrara, 2000), edited by C. Bordoni, A. V. Laghi, A. Paolucci, Siena 2000, pp. 280-285; A. V. Laghi, “Giuseppe Marchiori, Henraux and “his” sculptors, from Rossi to Morandi, from Viani to Arp. Giuseppe Marchiori art critic”, exhibition catalog (Venice, Bevilacqua La Masa Foundation, 2002), edited by S. Salvagnini, Venice 2001, pp. 97-109. A.V. Laghi, “L’Henraux di Querceta (1962-72) and his sculptors”, in “From ‘Marmo’ to marble”, cit., pp. 13-21.

8 B. Alfieri, “A new magazine”, in “Marmo”, n. 1, December 1962, p. 13.

9 Ibid.

10 “The sculptor Henry Moore”, in “Marmo”, n. 1, December 1962, pp. 22-47; “Jean Arp, 50 years of creation”, in “Marmo”, n. 2, November 1963, pp. 21 - 57 (with the publication of two poems by Arp); “Adam monumental sculptor”, in “Marmo”, n. 3, December 1964, pp. 28-39.

11 Le Corbusier, “Sur l’Acropole”, in “Marmo”, n. 2, November 1963, pp. 17-21 (diary pages from 1910; indicated in the magazine as published in “Almanach d’architecture moderne”, Esprit Nouveau Collection, 1925); G. Michelucci, “Notes”, in “Marmo”, n. 2, November 1963, pp. 61-63; E. Brunori, “Meeting with Michelucci”, in “Marmo”, n. 2, November 1963, pp. 63-75; L. Mosso, “Alvar Aalto’s Vogelweidplatz”, in “Marmo”, n. 4, December 1965, pp. 8-51.

12 The following contributions are worth noting: P. Sanpaolesi, “The Artemide construction site in Sardi”, in “Marmo”, n. 2, November 1963, pp. 75-87; M. Dezzi Bardeschi, “New research on the Holy Sepulcher in the Rucellai Chapel in Florence”, in “Marmo”, n. 2, November 1963, pp. 134-161; P.C. Santini, “Marble objects by Enzo Mari”, in “Marmo”, n. 3, December 1964, pp. 130-132.

13 Made on commission for Pope John XXIII on the occasion of the Second Vatican Council of 1962.

14 B. Cartei, “The restoration of the marble inlays of Montecassino”, pp. 97-112; A. Dini, “The installation of Henraux at Palazzo Grassi”, pp. 113-122; G. Nuti, “Note on the exhibition of the restoration of Montecassino”, pp. 122-130.

15 Henraux Sculpture Seminar. Regulation, ASH.

16 B. Alfieri, “The first Henraux sculpture workshop”, in “Marmo”, n. 2, November 1963, p. 212.

17 C. V. (Giuseppe Marchiori), “Artisti alla Henraux”, in “Marmo”, n. 3, December 1964, p. 134.

18 C. V. (Giuseppe Marchiori), quote, p. 141

19 C. Volta (Giuseppe Marchiori), in “Marmo”, n. 4, December 1965, p. 202.

20 Ibidem.

21 P. C. Santini, “The great fountain of Adam for Chantilly”, in “Marmo”, n. 4, December 1965, p. 110.

22 Cidonio would follow up elsewhere the project to create an international center for the visual arts in Versilia. In the following years he in fact, opened the “Officina” laboratory at Argentiera di Seravezza, which was oriented towards design.

23 The work can be dated to the end of the 1960s. See A. V. Laghi, profile, in “X International Biennial”, quote, p. 256.

24 The work was presumably made between 1968 and 1969. See letter sent to the artist on 14 March 1969, kept at ASH.

25 The work was presumably made in 1968. See letter sent by the artist to the Henraux company on January 17, 1968, kept at ASH.

26 The work was donated to the company in January 1969. See letter sent by the artist to the General Manager of the Henraux Company on January 9, 1969, kept at ASH.

27 The exhibition ran from 1st July to 30th October. It was organized by the then director of the company, Mario Paiotti, with the collaboration of Tacconi and Citi.

39 1821>2021

THE USE OF MARBLE FROM ALTISSIMO IN SCULPTURE FROM 1821 TO THE BEGINNING OF THE TWENTIETH CENTURY

BY ANDREA TENERINI

Despite the difficulty of finding the sources, the author gives readers a well documented and unique survey on the use of the statuary of Mount Altissimo in great European and international sculpture during the first hundred years of Henraux’s activity.

40 1821>2021

1821>2021

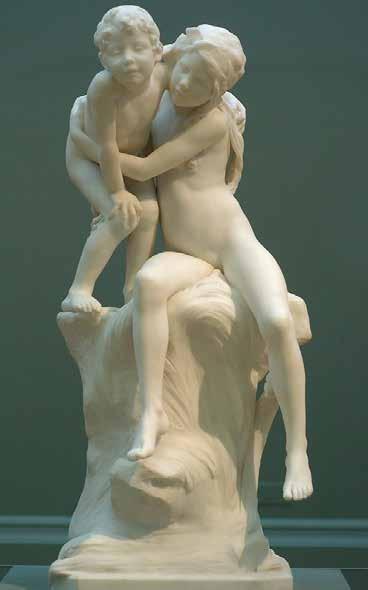

Ernest Christophe, The Human Comedy

The presence of material that lent itself «to any kind of sculpture work» in Seravezza had been confirmed by all the authoritative artists that the two, thanks to their respective friendships, had brought to Versilia.

The disappearance of the oldest evidence relating to the supplies of the material from the Henraux archive prevents a systematic reconstruction, starting from the epicentre, of detailed history on the use of Versilian marble in the sculpture of the period from the neoclassical to the early twentieth-century avant-gardes. To attempt an initial assessment on the subject, which is inevitably just a summary and necessarily discontinuous, it is necessary to direct research into the study of publications on different artists and on the scrutiny of publications of the time or in foreign archives. The French ones, in particular, are rich in documentation, albeit poorly studied. However, they present some difficulties since in the documents the statuary is often defined, in a generic way, as simply coming from Carrara.

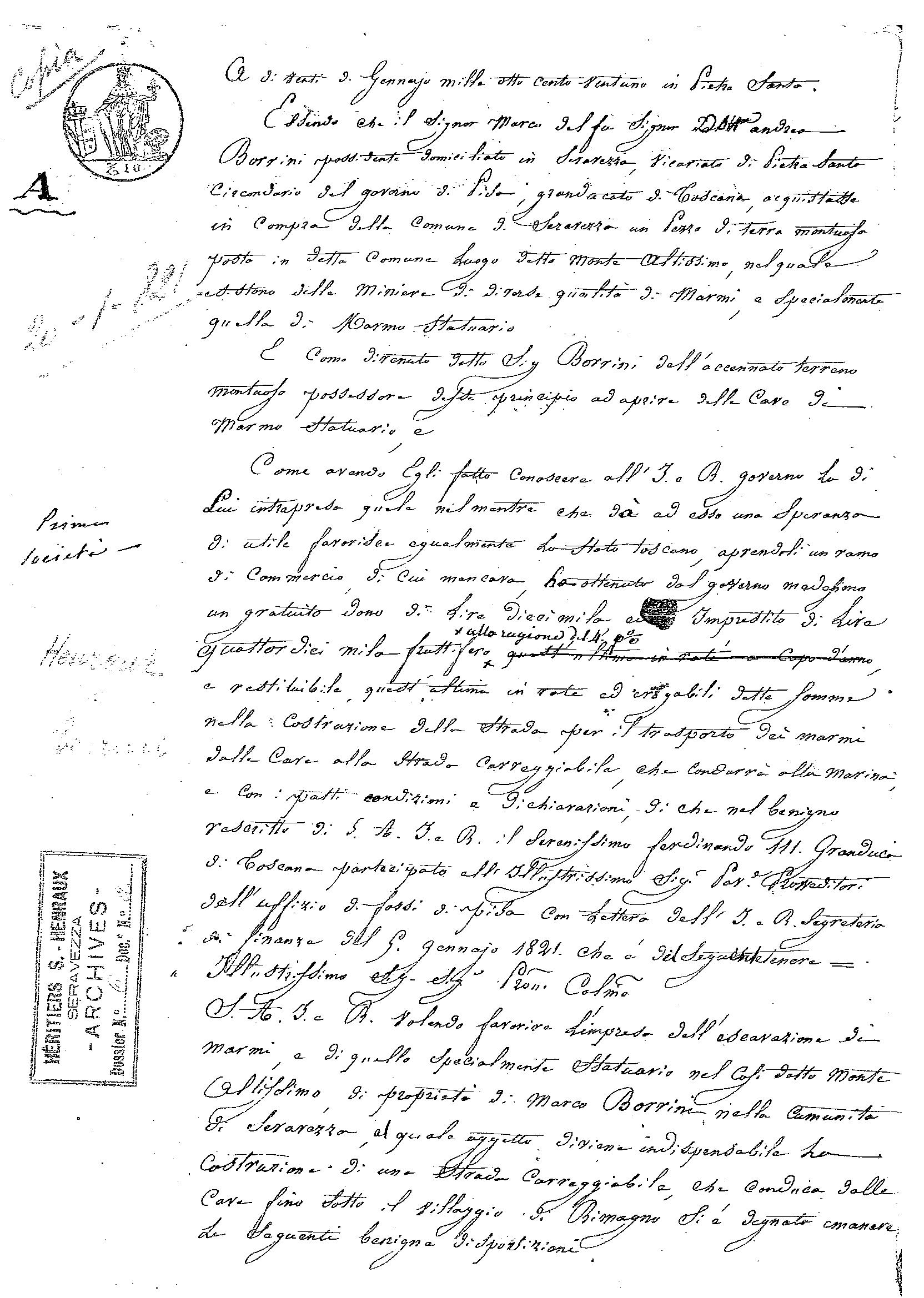

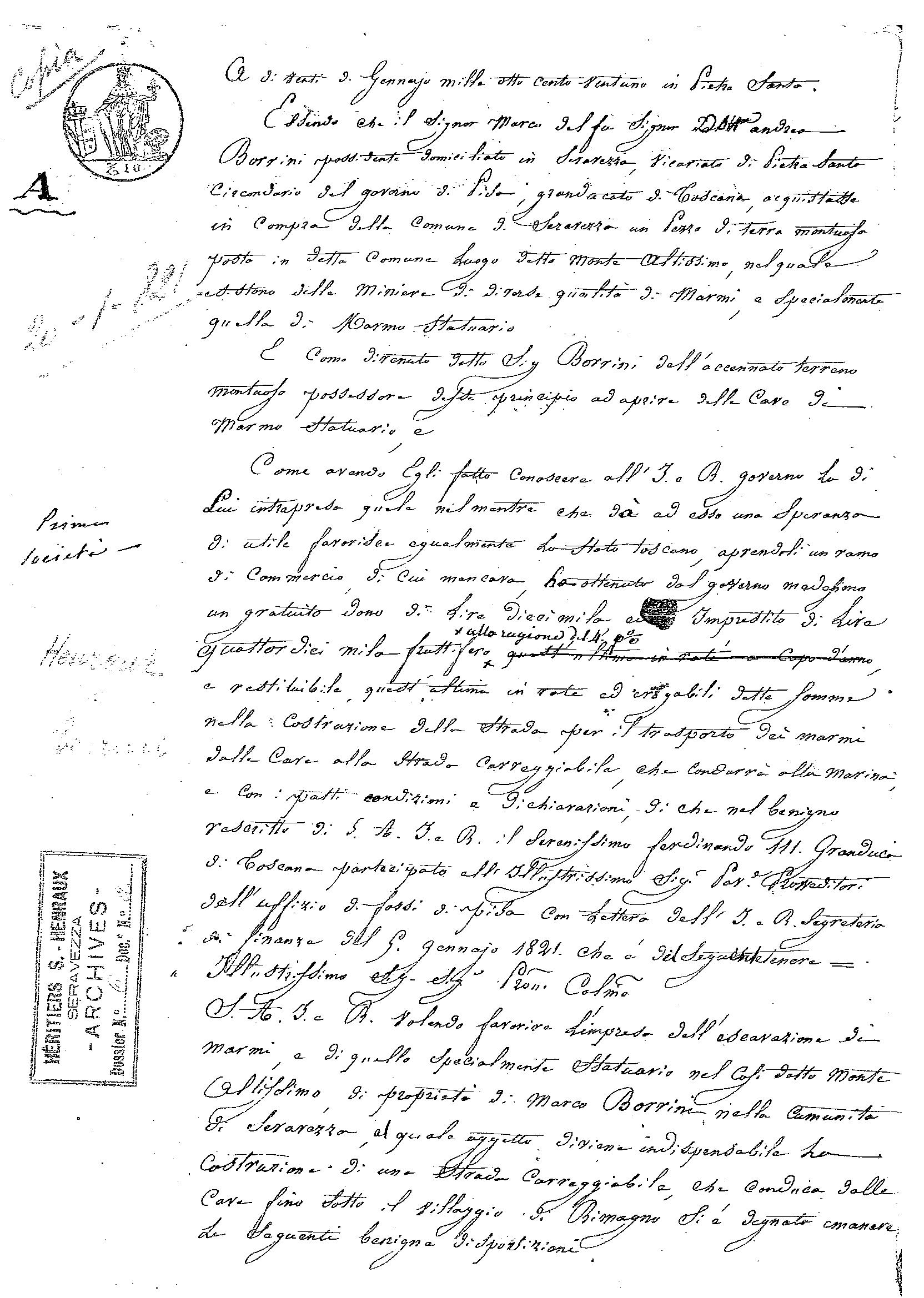

Central to the partnership between the former Napoleonic officer Jean-Baptiste Alexandre Henraux and Marco Borrini for the reopening of the Altissimo quarries there was a rather ambitious project which, making use of the men’s relationships, started with the extraction and sale of marble for architecture and decoration to reach the more prestigious one of statuary.

The presence of material that lent itself «to any kind of sculpture work» in Seravezza had been confirmed by all the authoritative artists that the two, thanks to their respective friendships, had brought to Versilia. So already by the beginning of 1823, just over two years after the start of the company, Cavalier Cordero di San Quintino, in correspondence with the Royal Academy of Sciences of Turin following an excursion to the quarries, reported that he had seen «... in Florence at the end of 1820 the first experiment that was made with the new statuary marble of Seravezza which fully corresponded to the common expectation. A skilful Tuscan sculptor took to portray the effigy of Grand Duke

42

1821>2021

Francesco Pozzi, Latona and Her Children

Ferdinando Terzo in profile and surrounded the bas-relief with an ornament so subtly carved and with a garland of flowers carried with so much love, that each of its leaves, each of its branches is drawn into it. hair as if it were made of very white and transparent wax, rather than stone». After the test, the fame of the new marble spread so quickly that, as the numismatist, archaeologist and art historian recalled, “even the Knight Tordwalsen wanted in recent days to prefer it to any other to draw the bust of Emperor Alexander”. Almost simultaneously with the resumption of mining, an artistic workshop was opened in Seravezza and the marble was supplied to the sculptors Giovanni Grazzini and Francesco Pozzi so that they could make works from it. If the former had shaped the aforementioned “Portrait of the Grand Duke”, which produced serially was purchased by various Tuscan administrations, with the Versilian stone Pozzi first created a figure of “Isis” and, in 1825, the group depicting “Latona with sons”, a work celebrated for the sharpness, beauty and toughness of the material.

Probably thanks to the intercession of San Quintino, the Piedmontese Giacomo Spalla, the greatest sculptor of monuments in the Turin of Vittorio Emanuele I, in July of the following year, after a visit to the quarries, bought several blocks of statuary for the execution of some reliefs dedicated to the Savoy victories. In a letter sent to Borrini in February 1827, the author praises the marble obtained “both for its whiteness and uniformity of grain, and for the ease with which it lends itself to the blows of the chisel”. Thanks to a product of undoubted value, to the strong friendships in the Grand Ducal world and, last but not least, to his lively and casual way, Marco Borrini was able to quickly and significantly enter the supplies for the remarkable market of the Italian artistic communities, in particular Florence and Rome. But the attempts of his partner

43

The letter from Charles Blanc to Henraux for the supply of a block of marble for the group “Ulysses” by James Pradier

Right, Gaetano Grazzini, Aronne

1821>2021

Over the following years, the appreciation of the material provided gave the definitive push for the complete affirmation of Seravezza marble within the studies of most of the active sculptors across the Alps and a large number of local artists.

Henraux to replace the use of Carrara marble with that of Seravezza in the French market found met with greater difficulty.

From 1806 Henraux was responsible for managing the purchase and shipment of marble blocks for Paris on behalf of Napoleon Bonaparte and later became the government commissioner for these supplies. With the Restoration, the demand for the material for the monuments, which was already high, increased exponentially and the French government tried, unsuccessfully, to find local marble capable of replacing that from the Apuane. Faced with discredit, Henraux, albeit with great difficulty, retained the role of Commissioner until 1823, the year in which Viscount Héricart de Thury, director of public works, suppressed his salary and replaced him with Carlo Orsolini owner of a quarry in Carrara, for the supply of statuary marble. The former officer took a few years to return to de Thury’s good graces, but from 1828, with the closure of all relations between the ministry and Orsolini, the marble of Monte Altissimo began to be used systematically by French sculptors, albeit to achieve a real predilection on the part of the ministerial bodies towards the material of Seravezza, it was necessary to wait until at least 1833.

Two orders, important in this sense were obtained at the beginning of the 1930s for the delivery of the statuary necessary to create many public works to be placed in Paris: four colossal statues for the stock exchange – entrusted to Jean-Pierre Cortot, Pierre Petitot, Jean-Baptiste Roman and James Pradier – and eight sculptures of the “Grands Hommes” series requested by the civil list for the Tuileries Garden.

Shortly thereafter a similar program, with manifest educational and civil values, was undertaken in the Grand Duchy of Tuscany on the initiative of the Florentine printer Vincenzo Batelli with the plan of «twenty-eight statues, representing as many illustrious Tuscan men for virtuous actions, sciences, letters, and arts», to be placed in the loggia of the Uffizi. In 1835 Borrini, adhering to the subscription wanted by Batelli, undertook to deliver the marble of Monte Altissimo to the twenty-four selected Tuscan artists for the realization of all the works. Over the following years, the appreciation of the material provided gave the definitive push for the complete affirmation of Seravezza marble within the studies of most of the active sculptors across the Alps and a large number of local artists. To achieve true international recognition, if not decisive superiority, at least of equivalence between the Versilian and Carrarese stone, it was, however, necessary to activate a more decisive involvement of the artists who worked in the other great Italian cities of art - in particular Rome - and above all to boost the use of the product in the wide Anglo-Saxon artistic world, which for centuries has been the prerogative of the entrepreneurial market of Carrara.

The opportunity to open an important gap also in this last sector of the market was presented with the arrival of Americans Horatio Greenough and Hiram Powers in Florence. Originally from Boston, Greenough was the first American sculptor to settle in the city in 1828. In July 1832 he received a prestigious commission for the construction of a large marble monument to George Washington, to decorate the heart of the Parliament building, from the government of his country. The sculptor and his collaborators took just under ten years to complete the work. Probably thanks also to the high opinion of the Bostonian on the material, several other artists active in the New World came to choose the marble of the Altissimo for the works to be transferred to America; among these, we recall the Neapolitan Luigi Persico who, at the beginning of the 1840’s, decided to use a large block of Versilian marble for the sculpture “The Discovery of America”, placed on the left side of the staircase of the eastern facade of the Capitol. On the right side, about ten years later, the group of “The Rescue” created by Greenough, again with Seravezza marble, was placed. A friend and colleague of the latter, Hiram Powers decided to leave America to settle in Florence in 1837. Shortly after arriving in the city, together with Greenough, he visited the «Seravezza quarries under the name of Altissimo, Vincarella, Polla and Falcovaja»; the two sculptors wrote to Borrini that in those places there is a marble

44 1821>2021

1821>2021

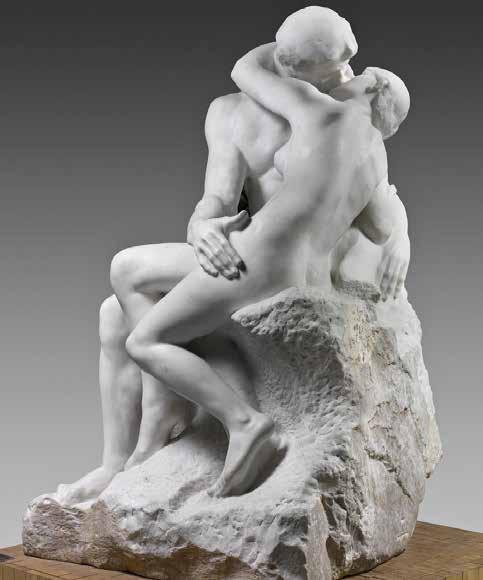

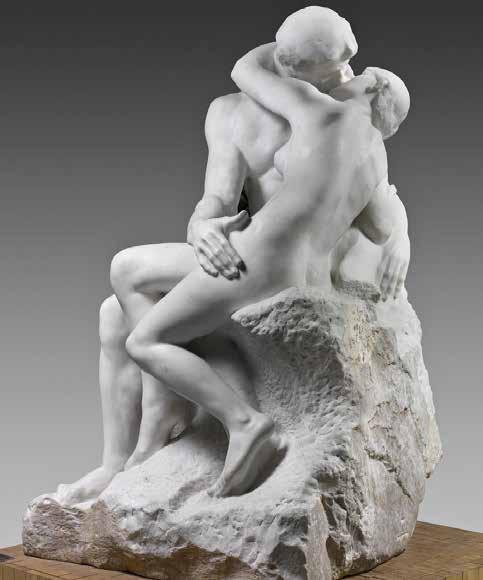

Above, Auguste Rodin, The Kiss

Right, Horatio Greenough, The Rescue

1821>2021

Powers was so impressed by the marble from Altissmo that he openly declared its predilection and superiority over the Carrara marble and, in a short time, became its greatest supporter in the Anglo-Saxon artistic world.

«of a quality equal to the best they had worked», as well as being «in terms of colour, context, fineness of the grain worthy of the highest recommendation».

Powers was so impressed by the marble from Altissimo that he openly declared its predilection and superiority over the Carrara marble and, in a short time, became its greatest supporter in the Anglo-Saxon artistic world. Shortly thereafter, among others, the American Thomas Crawford, a pupil of Thorvaldsen, used the white statuary blocks of Seravezza for the imposing work sculpted in Rome depicting “Orpheus and Cerberus” and the Irish John Hogan, for the colossal statue depicting “Daniel O’Connell”, now in Dublin City Hall.

In 1840, in a short anonymous text entitled «Tuscan statuary marbles» printed in the “Gazzetta di Firenze”, mainly to reject the rumours about an alleged inferior quality of the Altissimo marbles was circulated by the merchants of Carrara, eleven artists were listed in the city studies of which “this Tuscan marble is being worked on in greater or lesser quantities”. Among these, in addition to Hiram Powers and Horatio Greenough, were Luigi Pampaloni, Aristodemo Costoli, Paolo Emilio Demi, Emilio Santarelli, Gaetano Grazzini, Ulisse Cambi, Odoardo Fantacchiotti, Luigi Magi and Raphael Insom.

But it was mainly thanks to the success of the works of Hiram Powers that the fame of the marble of Altissimo spread throughout Europe and the Anglo-Saxon world. Tormented by the expressive rendering of the modelled surface, the American artist found in the marble of a vein recently discovered in the Falcovaia quarries, the ideal material capable of influencing his aesthetics. The obsession with the natural description of Powers’ bodies is particularly expressed in the statue of “Tempted Eve” – now at the National Museum of American Art in Washington – which the artist had exhibited privately in his studio and on which he had worked, shortly after his arrival in Italy until his death. In 1841 – the year in which Berthel Thorvaldsen’s visit to the Altissimo quarry is also remembered – he sculpted “The Greek Slave”, his most famous work, with which he obtained extraordinary success in England and America. The triumphant English premiere of a replica of the statue at the Crystal Palace exhibition

47 1821>2021

Left, Enrico Pazzi, Dante Alighieri

in 1851 strengthened the popularity of the sculpture internationally, boosting Powers’ reputation and definitively promoting the qualities of Seravezza marble.

The sculptor – with Greenough, the Grand Duke, the antiquarian Arcangelo Migliarini and the banker Emanuele Fenzi – strongly encouraged the use of this material, considering it the most suitable for rendering the complexion as, despite being harder than marble Carrara, had such a fine grain that it resembled porcelain. When asked about the merits, Powers later declared to the press: «Everyone now craves Seravezza marble and this is largely due to the reputation it has obtained in England through some of my works which did not show stains or defects in the material».

Twenty years after its birth, at the moment of greatest diffusion and appreciation of the Altissimo marble, came the appointment as director of the company of Jean-Bernard Sancholle, whom in 1839 Alexandre Henraux had designated as his universal heir, and the difficult situation of Borrini burdened by debts intensified the company’s relations with France. The award of the prestigious contract for the supply of marble for the tomb of Napoleon I at the Hôtel national des Invalides, together with that for the ornament of St. Isaac’s Cathedral in St. Petersburg designed by Auguste de Montferrand, stipulated in 1845, further consolidated the fame of the Seravezza marbles beyond the Alps. The relations of the Henraux family with the sculptors active in Paris and in particular with James Pradier, creator of the twelve sculptures that today adorn the architectural layout that surrounds the Bonaparte sarcophagus, depicting “Victories” to symbolize Napoleon’s

48 1821>2021

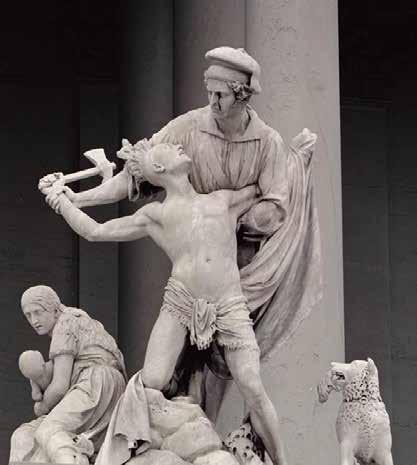

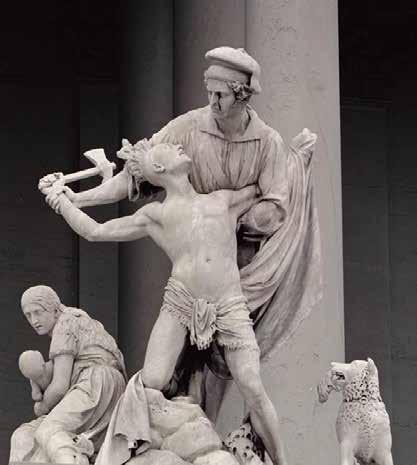

Henri Gaudier Brzeska, Samson and Delilah, erotic group

military campaigns, initially helped the company to maintain a leading role in the supply of the statuary to French sculptors, through state orders.

Despite the appreciation of the international artistic community for the statuary of the Altissimo, the financial difficulties and heavy disputes between the shareholders continued from the mid-1840s. This was due to the inclusion of new shareholders and the establishment of a new company, combined with the reinvigoration of the Carrara market and the use of almost all the workers active in the quarries in honouring the heavy commitment of the order for St. Petersburg. All of which heavily influenced the supply of the material for sculpture.

So, despite Leonardo Pilla in 1845 recounting that «the largest blocks of first-class statuary marble extracted from the quarries of Falcovaia, reduced to the highest degree of cleaning, were 500 to 600 cubic palms (approximately), and served for colossal sculptures», and that the marbles of Altissimo continued to be requested by many artists, especially for works of a monumental nature, the few documents found tell of a considerable slowdown throughout the 1850s and the first half of the following decade in the use of the statuary of Seravezza.

Due to its limited availability and high quality, the marble for sculpture extracted from the Seravezza quarries continued to be the most expensive Apuan marble at the beginning of the 1860s. In the catalogue of the Universal Exhibition in London of 1862 it is recounted how the statuary of Mount Altissimo was «superior to any other, preferred by every chisel,

49 1821>2021

Hiram Powers, The Greek Slave

50 1821>2021

but at the same time the most expensive». In that year, in the square of Florence, the firstclass quality marble for sculpture of Carrara was sold at 1200 lire per cubic meter, against 1400 of the similar product of Seravezza, with much higher prices in the case of the larger blocks and those without stains.

During this period there was the extraction from the quarries of La Polla and the triumphal arrival in the city of the majestic 33-ton boulder used by Enrico Pazzi to carve the large statue of “Dante”, which now resides on the side of the facade of Santa Croce in Florence. The sculptor from Ravenna would create several works with Seravezza marble including “Girolamo Savonarola presents Christ as King of Florence to the People” and the bust of “Jean-Bernard Sancholle Henraux” for the home of the entrepreneur, which his son Roger would later replicate, using the same artist for the funeral monument located in the cathedral of Seravezza, designed by the architect of the Paris Opera, Charles Garnier. At the end of January 1864, on a journey to Italy with painter Gustave Boulanger and colleague Louis Victor Louvet, coming from Menton, Garnier stopped for a couple of days in Seravezza and then continued by train to Pisa. In Versilia, hosted by SancholleHenraux, he took the opportunity to visit, probably not for the first time, the quarries of the Altissimo and chose the marble that would be used to build the large staircase of the Opéra.

In this period France, together with Italy, remained the privileged place for sending the statuary marble of Altissimo: in addition to the prominence that the Versilia quarries continue to have in French publications, also the news on the use of the material by important Artists such as Julies Cavelier, who used it for the work “Cornelia mother of the Gracchi”, or Ernest Christophe who chose it for the sculpture “The Human Comedy”. A work also known as “The Mask”, now in the Orsay Museum, is known for the poetry dedicated to it by Charles Baudelaire.

The reasons for the success in France of the statuary marble of Vincarella, Polla and Falcovaia can also be attributed to the more than excellent ties that Jean-Bernard Sancholle Henraux held with the various directors of the French Académie of the Villa Medici in Rome, until his death in 1881. The supply of marble for the plastic artworks sculpted by Pensioners and the granting of considerable discounts, which reached half the market price, undoubtedly exerted a loyalty effect on the product. With the taking over of the company from Jean Bernard’s son, Roger, the attitude became less condescending, also

51 1821>2021

Left, William Robert-Colton, The Spring Tide of Life

Above, Giacomo Spalla, Vittorio Emanuele’s Return to Turin

due in part to some disagreements over the quality of the material supplied and regarding the procurement of the same by Carrara traders. At the end of the eighties, the alternation of the heads of the institution and the arrival of artists linked by an old friendship to the Seravezza company restored strength and impulse to the historic collaboration. At this stage, among the artists most fond of using the marble of Altissimo, we find Henri Chapu. The sculptor, known for the frank and elegant naturalism of his works, is remembered visiting the Seravezza quarries on several occasions and documented, one last time, in the spring of 1890 to work on the bas-relief for the “Monument to Gustave Flaubert”, today at the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Rouen, which its workers had roughed up in the previous weeks. When Roger died in 1890, the Sancholle Henraux family turned to Chapu for the creation of the bust for the monument in the cathedral of Seravezza, which due to the death of Chapu was completed by Charles Desvergnes.

In the autumn of 1901 Bernard, son of Roger, hosted Auguste Rodin in Seravezza, during his triumphal trip to Italy which, in addition to Venice – where he was the guest of honour at the Biennale – also took the sculptor to Turin, Lucca, Perugia and Pisa. His presence in Versilia was determined by the idea of acquiring blocks of marble to be used, in particular, for a replica of the famous «Le Baiser» group. Not only, as the French press wrote, Rodin «returned satisfied with his trip», but the speed of sending the block and, probably, the prices charged were so benevolent that the close collaboration between Rodin and Henraux is continuously attested to over the next fifteen years. The relationship took on even more force in 1906, when Alexandre Berring-Nicoli’s widow,

52 1821>2021

Left, Paolo Emilio Demi, Mother Educator Right, Pio Fedi, Nicola Pisano