SECRETS OF THE WOOLLY MILKCAP TV’S ARIT ANDERSON EXPLORES THE GARDEN MAPPING THE DNA OF NATIVE SPECIES ISSUE 84 AUTUMN 2022 UNLOCKED THE MAGICAL WORLD OF TREES

OUR CONTRIBUTORS

Dani Garavelli

Freelance journalist and documentary maker Dani Garavelli is a columnist for Scotland on Sunday, and contributes to titles including The Scotsman, The Herald and The Guardian. She was named Feature Writer of the Year at the Scottish Press Awards in 2019, 2020 and 2021.

Susan Flockhart

A freelance journalist based in Glasgow, Susan Flockhart is a former editor of The Big Issue in Scotland and a long-time comment and features editor for The Sunday Herald

She writes on a broad range of topics including literature, heritage, nature and wildlife.

Laura Forrest

Molecular laboratory manager for the Garden, Laura Forrest divides her time between teaching and helping others with their projects, and research. Since completing her PhD on begonia phylogenetics, she has largely worked with bryophytes. She carries out DNA barcoding for the Darwin Tree of Life project.

10 Discover the Garden with our new columnist Arit AndersonKirsty Anderson

IN THIS ISSUE

2 THE VIEW

Memories of Queen Elizabeth II on a visit to the Edinburgh Garden

5 EXPLORE

The latest news, exhibitions and events to inspire you

8 GROUNDWORK

Fiona Leith takes a deep breath and uses the quieter months to prepare

10 INTERVIEW

Walk with BBC Gardeners’ World presenter Arit Anderson as she explores the Edinburgh Garden

18 COVER STORY

Arborist Will Hinchliffe unravels the magical mystery of trees

24 SCIENCE

How the Garden is helping sequence the genomes of all life on Earth

27

Your guide to the best presents available at the Garden’s shops this autumn and OF

The Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh is a Non Departmental Public Body (NDPB) sponsored and supported through Grant-in-Aid by the Scottish Government’s Environment and Forestry Directorate (ENFOR).

The Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh is a Charity registered in Scotland (number SC007983).

Patron HRH The Prince Charles, Duke of Rothesay

The Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh, 20a Inverleith Row, Edinburgh EH3 5LR 0131 248 2800 rbge.org.uk

Consultant Editor Kathleen Morgan kathleen.morgan@thinkpublishing.co.uk

Commissioning Editor Andrew Cattanach andrew.cattanach@thinkpublishing.co.uk

Group Art Director Jes Stanfield jes.stanfield@thinkpublishing.co.uk

Group Managing Editor Sian Campbell sian.campbell@thinkpublishing.co.uk

Client Engagement Director Clare Harris clare.harris@thinkpublishing.co.uk

Advertising Sales Elizabeth Courtney elizabeth.courtney@thinkpublishing.co.uk 0203 771 7208

Botanics Edinburgh by Think Enquiries regarding circulation of Botanics should be addressed to Clare Harris clare.harris@thinkpublishing.co.uk

Opinions expressed within Botanics are those of the contributors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh. All information correct at time of going to press.

Printed by The Manson Group, St Albans. Finished reading? Please pass your copy on or recycle it.

DIVE IN

GIFT GUIDE

winter 28 ANATOMY

A FUNGUS The secrets of the woolly milkcap WE’VE CHANGED Tell us what you think of your new Botanics magazine at membership@rbge.org.uk Cover photograph by Bailey-Cooper Photography/Alamy RBGE.ORG.UK AUTUMN 2022 1

Queen Elizabeth II

The Garden was honoured to welcome Her Majesty The Queen on several occasions during her 70-year reign. Her most recent visit was in 2010 to open the John Hope Gateway. Her Majesty is seen here leading the way during a visit in July 2006 to unveil the Queen Mother’s Memorial Garden – a living tribute to her mother, who had been patron of the Garden. Queen Elizabeth is followed by the Duke of Edinburgh and Camilla, now the Queen Consort.

PHOTOGRAPH BY SECCHI/SHUTTERSTOCK

PHOTOGRAPH BY SECCHI/SHUTTERSTOCK

2 AUTUMN 2022 RBGE.ORG.UK THE VIEW

1926-2022

MARCO

RBGE.ORG.UK AUTUMN 2022 3

EXPLORE

Discover a world of possibility at the Garden, from biodiversity to sculpture

SCOTLAND LEADS THE WAY WITH NEW PLANT BIODIVERSITY STRATEGY

Ahead of the delayed final instalment of the UN Biodiversity Conference (COP15) in Montreal, Canada, this December, we co-authored a plant biodiversity green paper that will lead the way in Scotland’s response to the biodiversity crisis.

The paper, Building a Plant Biodiversity Strategy for Scotland,

published in summer 2022, forms part of a larger, nationwide strategy to restore and safeguard the country’s wildlife. It targets and prioritises the actions needed to help combat the threats facing Scotland’s plant biodiversity, including climate change, habitat loss, invasive alien species, pathogens and pollution.

Written in collaboration with NatureScot, the paper pinpoints the key elements of a successful plant biodiversity strategy, placing plants and botanical expertise at the forefront of any legislation that hopes to effect meaningful change.

As COP15 takes place this year, the paper complements our vital work in the

field, including the cultivation of the country’s most threatened species, and the use of genetic and horticultural techniques to help grow the most robust specimens that can be reintroduced into the wild.

As active members of the Consortium of Scientific Partners, we look forward to participating at COP15, and will take part in events which focus on genomic approaches to biodiversity conservation.

The full strategy green paper is at nature.scot/doc/building-plantbiodiversity-strategy-scotland

Blanket bog, The Flows National Nature Reserve and (inset) the Alpine blue sowthistle translocation team, Cairngorms National Park

Lorne Gill

RBGE.ORG.UK AUTUMN 2022 5

1

/ NatureScot / 2020Vision; RBGE

INSPIRED REGIUS KEEPER SIR ISAAC BAYLEY BALFOUR REMEMBERED

Sir Isaac Bayley Balfour, who died on 30 November 100 years ago, was the Garden’s eighth Regius Keeper. During his period in office he transformed the Gardens administratively and physically, rebuilding the main Glasshouses and constructing a botany building. The son of John Hutton Balfour, Isaac was considered to be an outstanding academic and inspiring teacher. He was knighted in 1920.

GIFT IDEAS

Give something extraordinary to the plant lover in your life this Christmas. Starting from just £31 a year, gift memberships include a year of free, unlimited access to our four Gardens, and other Gardens around the UK and abroad, along with a host of other exclusive benefits. What’s more – your gift gives back to nature, with every penny going towards helping explore, conserve and protect plants for generations to come. To find out more visit rbge.org.uk/giftmembership

CELEBRATING THE LIFE AND WORK OF DR ARCHIBALD HEWAN

This October, we pay tribute to the life and achievements of 19th-century black doctor and naturalist Dr Archibald Hewan. In our Archives and Herbarium we hold letters and plant specimens sent from Equatorial Guinea, West Africa, to Professor John Hutton Balfour, the Regius Keeper at the time. Dating back to 1862, these specimens were one of the main ways that the scientific community gained a global understanding of plants.

Learn more about the story of Dr Archibald Hewan at rbge.org.uk/news

BALFOUR BEATTY AWARDED PALM HOUSES CONTRACT

We have awarded construction company Balfour Beatty the contract to restore our Grade-A Listed Temperate and Tropical Palm Houses. The two-year, £12.5-million contract will see Balfour Beatty renovate stonework, roof structures and windows, as well as all ironwork, including the spiral staircases, guttering and downpipes. Once complete, the project will form a critical part of our ambitious ‘Edinburgh Biomes’ plan, which aims to protect the Garden’s unique and globally important plant collection.

6 AUTUMN 2022 RBGE.ORG.UK EXPLORE

3 2

4

READ ALL ABOUT THE YEW HEDGE

The Edinburgh Garden is surrounded by a unique conservation hedge, comprised of almost 2,000 yews collected from 16 countries.

Researchers at the Garden, along with their international partners, described 70 species in a 12-month period, despite Covid-19 lockdown restrictions. The species, which include mosses, fungi and a single tree, were from countries around the world, including Australia and Ukraine.

One species of begonia, which grows on the eastern ridges of the Himalayas, turned out to be the same as an undescribed species tended by horticulturists in our Research Glasshouses since 1986.

The Garden’s Dr Mark Hughes collaborated with his colleague in Bhutan, Phub Gyeltshen, to describe Begonia bhutanensis in a joint research paper.

“Every time we describe a species as new to science we are recognising the international obligation to fulfil the objectives of the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation,” says Hughes.

“Giving plants a scientific name is the first step towards ensuring their future, that of their habitats, and the humans and animals that benefit from their very existence.” BEGONIA

An outdoor sculpture trail at Dawyck, A Delicate Balance, explores feelings and themes of strength and fragility in nature. It is a collaboration between Dawyck and Susheila Jamieson, a sculptor based in the Scottish Borders. Find out more at rbge.org.uk/delicatebalance

Martin Gardner’s latest book tells the fascinating story of these remarkable plants, including ‘celebrity’ heritage trees, such as Scotland’s Fortingall Yew in Perthshire, and details of those collected from other countries, including Croatia and Albania.

Martin Gardner worked for 25 years at the Garden and is an expert on conservation, for which he was awarded an MBE in 2013.

The Yew Hedge by Martin Gardner, priced £20, is available to buy at rbgeshop.org

Begonia researcher Dr Mark Hughes in the Research Glasshouses

Begonia researcher Dr Mark Hughes in the Research Glasshouses

RBGE.ORG.UK AUTUMN 2022 7

5 RARE

AMONG 70 NEWLY DESCRIBED SPECIES DON’T MISS 6

A slow dance with nature

Autumn days spent reflecting and preparing are to be relished, writes Fiona Leith

Come a little closer so that I can let you in on a secret. The home gardening year doesn’t end when the schools go back, or when the clocks go back, or even when the whipping south-westerly winds of autumn threaten to knock you on your back as you totter round your patch armed with nothing but faith, hope and a tammie full of dreams.

Fools we might be, optimists most certainly, but far from the joy of secateurs being over for another year, we gardeners are arguably at our most productive and imaginative in these coming months.

It’s not all on paper, either – no, leave that for the dull January and February days when you’re champing at the bit to get out while the snow is threatening and it’s too darn early to plant seed. These are the autumn days, my friends, of warm mugs, wellies and creating your planting plans for the year ahead. Whether something failed or flopped, or a new idea has taken root, this is the time for taking physical stock and preparing to grow again.

As seasons pass, my horticultural instincts at home creep more and more towards slow gardening. The greatest learning, I have found, takes place in the watching and waiting. It’s the exact opposite of the boom and bloom commercialism of the large-scale plant sales we see in high street retail spaces, where I was astounded in August to see healthy cosmos and dahlias at cut price simply because they needed deadheading. My cosmos were still waltzing in the sunsets of November last year, so I’m bemused by such short-termism.

What is a garden if not a space to watch things grow? I am all for the right plant in the

Fiona Leith is a graduate of Horticulture with Plantsmanship at RBGE/SRUC. She now runs her own business as The Plantswoman, supporting Scottish nature and gardens.

TRY THIS

A feast for birds

You might not be sowing in autumn, but you can leave your seedheads for the birds to feast on. Poppies, alliums, honesty and sedums make for a great menu.

A home for insects

right place design principle, but as my earthly pursuits have developed over the years, so have my patience and understanding for the fact that a garden is truly at its best when it functions as a slice of nature, and nature is wild, unpredictable and bigger than us all.

Gardens are living, breathing ecosystems which, when respected and valued, can become one of our greatest personal achievements as well as prized botanical assets such as those of Edinburgh, Benmore, Dawyck and Logan. Yes, they are a showcase for pleasure and taste, but they are ultimately our acknowledgement of our responsibilities to nurture and protect where we live.

Our little depictions of the natural world root us and remind us of what really sustains every living thing. I’d like to think we can all play our part in understanding the role of flora and fauna in the world beyond our own nose, and that a growing appreciation of gardening as an act of benevolence can become second nature. It would be worth all the waiting and watching.

Want to see a nature-based solution and biodiverse gardening in action? The green roof at Dawyck Visitor Centre will not only help insulate the building over the colder winter months, it also creates a crucial habitat for insects and pollinators.

A haven for humans

Being in your garden at night can be one of the most mindful and sensory experiences. Catch the evening opportunities while there’s still light and warmth to bask in.

Shutterstock 8 AUTUMN 2022 RBGE.ORG.UK GROUNDWORK

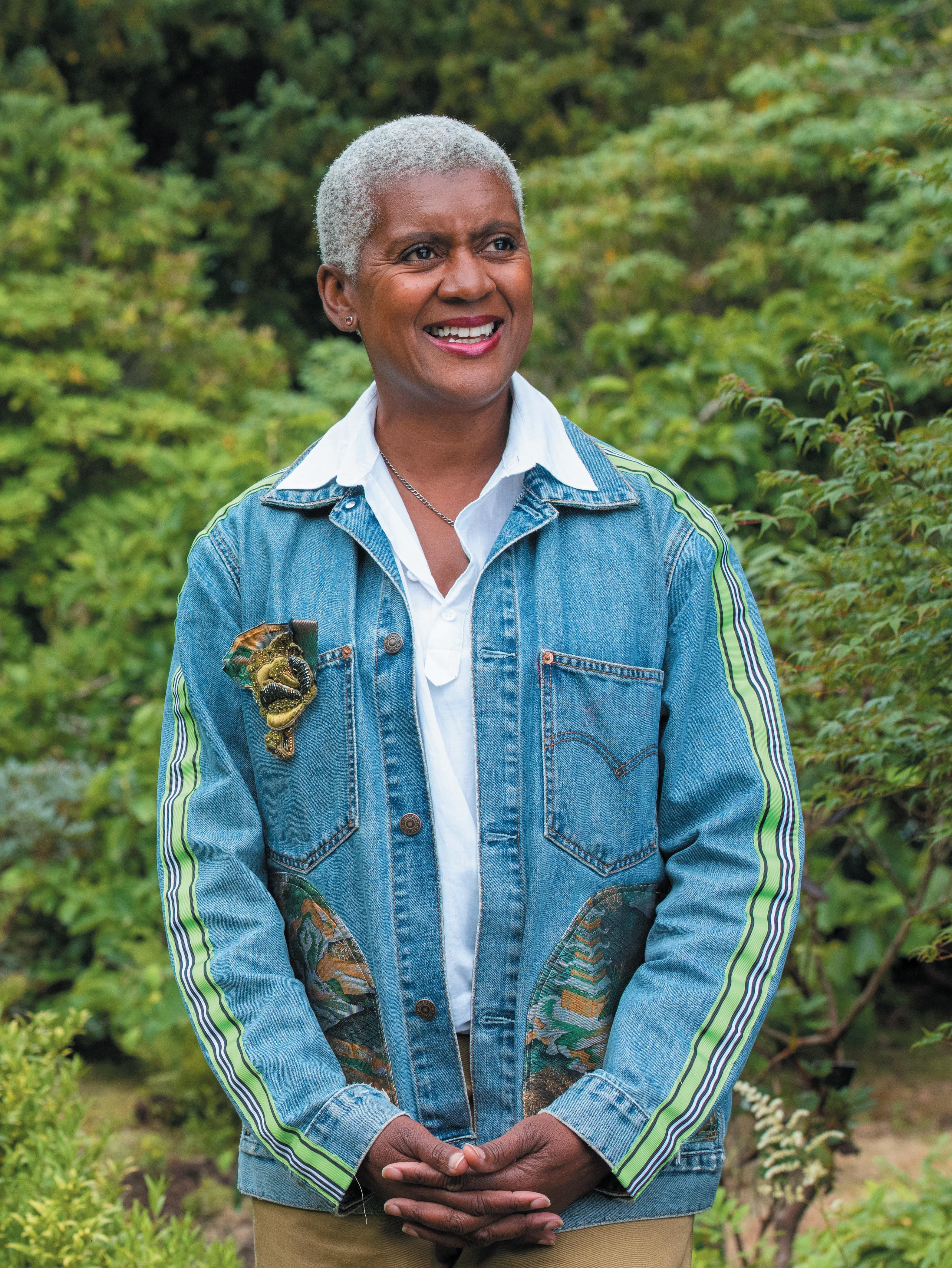

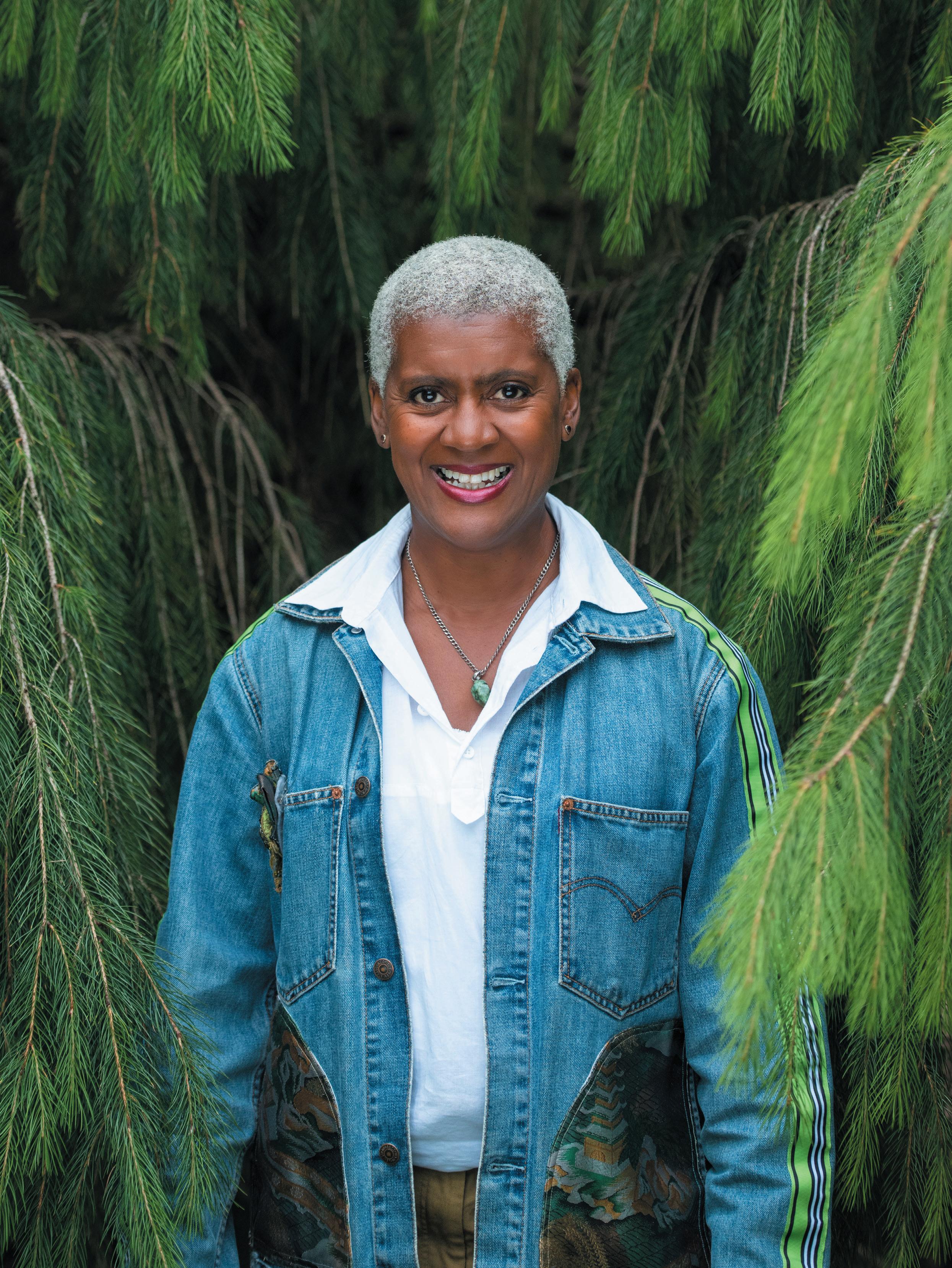

‘Without plants we don’t eat, we don’t breathe’

Arit Anderson is sitting in her garden, enjoying the dappled shade. The presenter of BBC Two’s Gardeners’ World has just returned from a visit to the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh and is fizzing with enthusiasm about the plants, the features and the people she encountered there.

“I was very lucky to be escorted round by David Knott [curator of Living Collections], and I was really impressed by the fact that, number one, the space offers free access,” says Anderson, who lives in south-west London. “That’s just wonderful as it means everybody can enjoy the Garden.”

Having lived most of her life in cities, Anderson believes green spaces are crucial to people’s wellbeing in urban areas and the Edinburgh Garden – just a mile away from Princes Street – is designed to be as accessible as possible. As she wandered happily among the Garden’s 70 verdant acres she was struck by the rich array of plants, trees and pathways. “I loved the fact that there

were lots of different zones and places to explore,” she says.

Arit Anderson is the new columnist for Botanics, and from the next issue will be sharing insights about all things horticultural, with a particular emphasis on sustainability. She is passionate about the need to garden with the planet in mind and during her Edinburgh visit was struck, she says, by “how well kept everything looked, especially given the recent lockdowns and hot weather”. Where she lives, the heatwave has been severe and even her drought-tolerant Rosa glauca is having to be “nursed back from the brink of dryness”.

The writer, broadcaster, garden designer and environmentalist doesn’t have a favourite plant – “That would be like being asked to name a favourite child!” Those she loves, though, include umbellifers, dahlias and that Rosa glauca – a sustainable gardening champion that’s a haven for bees, birds, butterflies and other wildlife. Assuming it recovers, the bush will soon be adorned with bright, beautiful hips, just as Anderson is coming into her elemental prime. “I’m a Virgo

Our new columnist, BBC Gardeners’ World presenter Arit Anderson, enjoys a voyage of discovery in the Edinburgh Garden

WORDS: SUSAN FLOCKHART IMAGES: KIRSTY ANDERSON

10 AUTUMN 2022 RBGE.ORG.UK INTERVIEW

INTERVIEW

and I like the handover of summer to autumn,” she says. “I love the shift of light when it becomes that bit more mellow. You get those slightly longer shadows and there’s a beautiful quality to the light.”

Virgo spans that period in the calendar when crops begin to ripen and, in classical myth, the constellation is linked to harvests, growth and the Earth’s cycles. And whatever role the Zodiac plays in our fortunes, there can be no doubt Anderson is a force of nature. Even her exuberant dress sense is now as integral to Gardeners’ World as all those blooming herbaceous borders. The customised denim jacket adorned with sequins that she wears on her visit to Edinburgh is a case in point.

Yet unlike many celebrity gardeners, who seem to have absorbed Latin plant names with their ABC, Anderson is something of a horticultural Jenny-come-lately, having rarely picked up a trowel until her mid40s. Brought up in the Hertfordshire greenbelt, she and her sister were fostered at a young age and grew up with several foster siblings. “We did have a garden,” she recalls, “but we were quite a big family so there wasn’t time for my mum to be tending it. But we lived near open

fields, so we’d play in the local woods or go for nature walks with the dog.

“I can’t pretend that as I child I sat there making mud pies and messing around with insects, but I’ve always had a sense of curiosity about the world and an awareness of nature. I remember in my teens sitting in a park watching

staying in central London flats and working in the fashion industry. Then, in 2011, aged 44, she moved a few miles south-west to Isleworth and a house with a small garden, expecting that her green-fingered sister would design the plot, allowing Anderson to simply “come home after floating around fashion-land and deadhead with a glass of wine”.

That’s not how things turned out. Being a “curious Virgo”, she says, returning to her astrological theme, she planted some herbs in an old sink to see what would happen. “They didn’t die, so that was good,” she laughs. “I probably didn’t even eat them – I was just in awe of the fact they were still actually there.”

cloud formations shift and change. And I loved going for walks with my mum, watching the wind through her hair. She had straight hair, I had short curly hair and I was like – I wonder what that would feel like?”

Despite her love of the great outdoors Anderson went on to embrace city living,

One plant led to another. Anderson became hooked and soon began offering garden design services around her neighbourhood before enrolling for a horticulture course at Capel Manor environmental college, then winning a Fresh Talent competition at RHS Chelsea Flower Show with some fellow students. When in 2016 she scooped a gold medal for a pioneering eco-conscious design at RHS Hampton Court Palace Garden Festival, she was interviewed on television and soon found herself presenting popular programmes such as the BBC’s Garden Rescue. Today she

‘I can’t pretend that as I child I sat there making mud pies and messing around with insects, but I’ve always had a sense of curiosity about the world and an awareness of nature’

Arit Anderson discovers the Edinburgh Garden with the help of David Knott, curator of Living Collections

RBGE.ORG.UK AUTUMN 2022 13

combines a successful broadcasting career with running her own garden design company, Diamond Hill, named after a piece of land in Nigeria that her late father had loved.

Sustainability is at the heart of all Anderson’s work – an ethic she traces back to her mother and wider family. “We’ve always been respectful of people, respectful of place,” she says. “We’d never be allowed to drop litter. As I get older all of that subliminal messaging is coming to the fore: are you leaving a place in a way that you’d expect to find it? Our own plots don’t just exist within their boundaries, they’re part of the patchwork of the wider environment.”

The best thing we can all do to improve our surroundings is relax and let wildlife in, she says. “If the garden is alive, with bugs and birds and even the annoying squirrels, it means your garden is functioning because there’s something in there to be had, whether it’s shelter or food. When you’ve got a garden that’s teeming with wildlife, then the garden’s alive and you feel more alive. And you can only have that sense of life in there if you’re not trying to kill everything with bug spray.”

What about slugs, though? Anderson admits to a past obsession with the slimy munchers, when she’d conduct early morning slug patrols and despair over the demolition of her lupins. These days she takes a more sanguine approach: she doesn’t plant lupins. “You wouldn’t invite someone for a gourmet dinner, lay it out with all the trimmings, and then say ‘Ah-ah, don’t touch’,” she chuckles.

Anderson presents a Growing Greener podcast but, rather than sanctimonious finger-wagging, her approach is to enthuse and inspire. She hopes her unusual trajectory – “fashion bunny to gardener” –shows the industry is open to everyone; it’s “inclusive, regardless of ability, physical or mental, and, of course, it doesn’t matter about colour, creed and so on”.

It takes hundreds of staff and volunteers to keep Edinburgh’s Garden looking beautiful and Anderson enjoyed chatting to some of them during her visit, along with Regius Keeper Simon Milne. One topic of conversation was the need to attract young people into horticulture. Anderson thinks this is crucial, partly to engage future environmental custodians but also because, as a qualified massage therapist, reflexologist and wellbeing therapy teacher, she believes in the power of the natural world to protect and restore mental health within this increasingly digitalised world.

“We know there is a prevalence of mental ill health among young people and, given the known benefits of gardening and horticulture to wellbeing, we need to make sure they have the opportunity to experience that.”

She wants to see horticulture on the curriculum, partly to address the lack of recognition for professional gardening skills and knowledge. “RBGE looks after massively important collections of plant material and research, and is doing fantastic work archiving plant material from around the world and acting as a connector to other gardens and the research being conducted within them.

“Yet, as someone said recently, we can be a little bit shade-loving as an industry. We’re quite modest. We share a lot and we like sharing knowledge, but we don’t necessarily get ourselves out there onto the right platforms or make ourselves as sexy as some other industries.

“We don’t pay brilliantly and there’s a perception, even in [the UK] government, that if you can’t get a job you can be a cleaner or a gardener –as if it’s a bad thing to do those roles, as if there’s something meaningless about our industry.

“Without plants we don’t eat, we don’t breathe. Yet the value of green space and nature is not given the credence that it should be.”

Teaching horticulture in schools would also tackle the situation highlighted by a recent study that showed a third of five-to-seven-yearolds think fruit and vegetables grow on supermarket shelves. “We don’t want to be in a situation where a younger generation doesn’t have a clue about food production,” she says.

At the home she shares with her partner and stepchildren, Anderson has remodelled their space, creating small vegetable plots for the children.

“We don’t have an allotment-sized garden but they can go outside and cut some lettuce or pick tomatoes,” she says. “It doesn’t have to be like The Good Life, completely self-sustaining, but when you appreciate something and

‘The Garden looks after massively important collections of plant material and research, and is doing fantastic work archiving plant material from around the world’

Arit Anderson at the Botanic Cottage, built in 1764-65 at the entrance to the former Edinburgh Garden on Leith Walk

RBGE.ORG.UK AUTUMN 2022 15 INTERVIEW

INTERVIEW

understand why something happens, it gives you a better connection to it.”

She has built a small garden studio and is looking forward to enjoying an al-fresco morning cuppa before starting work there – though her schedule looks hectic. A second series of her podcast has been commissioned and, as well as working with others to set up a Sustainable Landscape Foundation, she is designing the Huntingdon community garden as part of an RHS Community Grant Scheme to create a new garden in each of the four UK nations. (Scotland’s equivalent is being created in Barshaw Park, Paisley, by Semple Begg Garden and Landscape Design.)

Anderson is looking forward to connecting with Botanics readers: “It’s a real honour to be asked to write the column. Having the chance to play a small part in the history of the Garden is quite amazing.”

As we chat online, a fragment of Anderson’s own plot can be glimpsed over her shoulder. Verdant and enticing, it’s a little urban Eden. Asked to describe her dream garden, she places “the luxury of space and time” at the top of her bucket list, then paints a vivid picture of the landscape she’d create given unlimited quantities of both.

“I’d have my meadow,” she begins. “I’d have a beautiful pond, perhaps even a lake. Maybe a copse of trees for shade. I’d have a rolling backdrop behind my garden, so I could look out over that, that lovely, borrowed landscape. And I would be a fantastic vegetable grower, which I’m not, so there’d be an allotment growing area.”

Anderson recently described her pinnacle moment, when she felt she’d “arrived” as a professional horticulturist, as sharing a stage with Sir David Attenborough at a Landscape Institute awards ceremony. Now, she mentions another ambition. “I’d love to have a cutting garden. Cut flowers are a joy, and if I had a walled garden dedicated to growing them, I’d know I had arrived.”

BEECH HEDGE

“I particularly liked the huge beech hedge that runs along the full length of the 165m herbaceous border. It was stunning and so impressive. That’s a show stopper.” Anderson believes green spaces play a “massively important” role within urban settings. “When I lived in a more central part of London, there’d be times when I’d crave open space and I would periodically go to Richmond Park for a walk. Those green spaces are important because they are subliminally in our energy field – they keep us connected. Living in big, urban, hard cities is great for certain things, but it doesn’t necessarily feed you. You have to have that green space around you.”

THE BOTANIC COTTAGE

“The beautiful Botanic Cottage is brimming with centuries of history from within its walls. I felt I could be in Provence.” The Botanic Cottage was built in the 1760s and stood at the entrance to the earlier

Edinburgh Garden on Leith Walk, both as the head gardener’s home and a place of study for historical figures such as Charles Darwin. For many years it lay unoccupied until, in the early 2000s, it was scheduled for demolition before being saved by a community campaign working alongside the Botanics. It was carefully dismantled and rebuilt within the current Edinburgh Garden in 2016.

MEADOW PATH

Anderson particularly enjoyed the semi-wild meadow-like borders along the path to the Botanic Cottage. “As well as being a critical place within the gardens for pollinators to feed and rest, they give a wonderful sense of perspective.” At the time of her visit, the borders were crammed with grasses, bright poppies and frothy cow parsley, one of the bestknown umbellifers. “I love looking at umbellifers. Just look at that flower head: you’ve got light and structure and the delicateness and the landing pad. They’re so pretty.”

Kirsty Wilson; Kirsty Anderson

THREE HIGHLIGHTS OF ARIT ANDERSON’S VISIT TO THE EDINBURGH GARDEN

You can read the first column by Arit Anderson in the Spring issue of Botanics, published in March 2023

16 AUTUMN 2022 RBGE.ORG.UK

WILL YOU SAVE OUR GREEN PLANET?

Our natural world is facing threats like never before. We must act now before it’s too late – but we cannot do it alone. With your help, we can protect and restore threatened species, ecosystems and habitats.

Donate today to join the fight against the twinned climate and biodiversity crises. Protect our natural world for generations to come.

Scan here or donate online at rbge.org.uk/donate

ARBORICULTURE SPECIAL BRANCH He nurtures a living collection of more than 3,500 trees. The Garden’s arboriculture supervisor, Will Hinchliffe, tells Dani Garavelli his vocation can be as tough as it is magical PHOTOGRAPHS: JEREMY SUTTON-HIBBERT

Before I meet Will Hinchliffe, arboriculture supervisor at the Garden, writer and tree-lover Mandy Haggith tells me a touching story about him. It dates back to 2013 when she was poet in residence there. An old Atlas cedar had succumbed to needle blight, and it was to be taken down. Haggith is a veteran of forest blockades where environmentalists pit themselves against loggers. She has witnessed giant trees crashing to the ground, their trunks mutilated by chainsaws.

“What Will did was the opposite of this,” she says. “He started at the top and cut it branch by branch, lowering each one gently to an assistant below. It was peaceful, meditative and respectful. It reminded me of nurses in palliative care who try to make the end as dignified as possible.”

So here I am a few days later, in the Edinburgh Garden, my neck craned,

watching Hinchliffe in a harness and helmet, move methodically through the branches of an American plane tree, a handsaw swinging like a sheathed cutlass from his waist.

Hinchliffe is slightly built – more Jack Flash than lumberjack – and as protective as Haggith has intimated towards the 3,500 trees and more than 730 species in his care. He is passionate, too. “This is the best part of the job,” he hollers down from his vantage point tens of feet above the ground. “Up in the canopy you see all sorts of things: the remnants of nests, different types of epiphytes [plants that grow on other plants], the way the branches have broken off or fused together in strange and interesting shapes.”

One day, while working in India, he peered into a cavity only to find some owlets peering back. But it can be just as thrilling here in Edinburgh. “On winter mornings when the sun is low and it filters through the flaking

trunks of the paperbark trees – that is magical,” he says.

Hinchliffe recalls Haggith’s Atlas cedar well. “It’s not so much cutting the trees down that’s tough, it’s making the call,” he says. “There was another cedar we removed last year – a very old tree, planted around 1847, and in a prominent position on the landscape. But its canopy had collapsed under the heavy snow in 2010 and we had had to take out the bits that had split to make it safe. It didn’t respond well.”

His team ummed and ahhed for a long time before deciding it had to go. Then they cut it into planks so its timber could be sanded and shaped into beautiful artefacts. Many of the Garden’s trees have been sponsored as memorials to loved ones who once wandered its lawns and groves. Their solidity and durability makes them perfect foils for the ephemerality of human existence. But when they finally die, they are often crafted into memorials to themselves.

19RBGE.ORG.UK AUTUMN 2022

“When trees get turned into an object they have a legacy,” Hinchliffe says. “Not only that, the object holds the narrative of the tree – in this case a story of storm damage and decline. Trees in general have huge interpretative potential held within them.”

“Because they have seen so much?” I ask.

“Absolutely,” he replies, “and because you can find a tree from most parts of the temperate world here, and you can tell a story about the place they come from.”

After studying botany at Aberystwyth University, Hinchliffe, 41, worked in the grounds and gardens at Longleat House in Wiltshire. Then one day his manager asked him to conduct a survey of an arboretum and he realised he wanted to specialise in trees. He did several courses and worked as a commercial tree surgeon before successfully applying to the Garden in 2011.

Today, his role within the Garden is wide-ranging and constantly evolving. He makes sure the Living Collection is nurtured and curated, but also undertakes consultancy and research, travelling to countries such as Japan, Nepal and Iran to study the flora, and to bring back seeds from wild trees so the species can be propagated and conserved here.

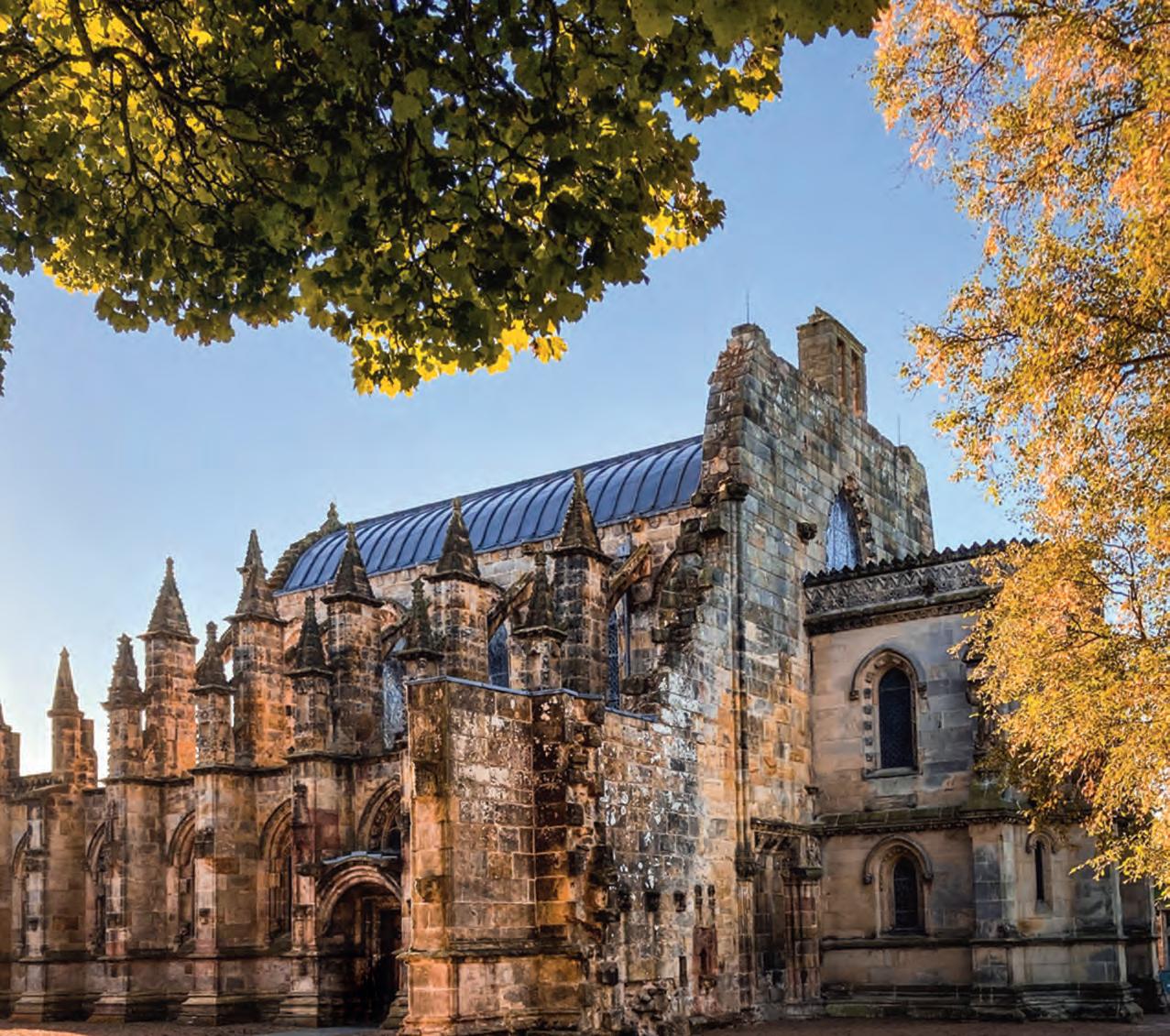

With a team of arboriculturists working under him, he doesn’t spend as much time up trees as he used to. But, as he wanders round the Garden on one of the hottest days of the year, pointing out his favourites, it is clear he still loves the limbs of them. There’s a sweet chestnut (Castanea sativa) with a trunk that twists like the Apprentice Pillar in Rosslyn Chapel, and an Indian hazel tree (Corylus jacquemontii) with its rugged bark and lush leaves – the only one of its species in cultivation in the UK. Not to mention the dawn redwoods (Metasequoia glyptostroboides) – relics of the Mesozoic Era. Until the mid-20th century this species was known only from 150-million-year-old fossils found in

California and was assumed to be extinct, but in 1943 a living specimen was found in China and soon seeds were distributed among the notable arboretums of the world, including Edinburgh.

The challenge for arboriculturists is that trees are being assailed on all sides. These giants of carbon sequestration are on the frontline of climate change, buffeted by winter gales, sucked dry by summer droughts. When Storm Malik hit the Garden in January 2022 it ripped a massive branch off a 130-year-old Himalayan cedar (Cedrus deodara), leaving a giant raw gash along its front.

“That limb accounted for a third of the tree,” Hinchliffe says. “It has opened the rest of the tree up, so other branches that were previously sheltered or restricted from moving are now exposed to future winds.” Soon the arboriculturists will attempt to cut it back in a way that makes it safe yet preserves its elegance and grace. It’s an art form. “You’re trying

to leave a flowing branch line, leave it sort of naturalistic, so there’s no sudden diameter change in the branches as you come up,” he says.

Global trade means the collection is also under attack from new diseases that stow away in plants as they cross international borders. There are checks, but phytophthora (fungus-like pathogens) are microscopic and it is difficult to inspect the soil imported alongside potted trees. Insects, such as oak processionary moths, come in as eggs, which are camouflaged against the tree bark to protect them from birds and other predators.

Hinchliffe shows me an old prickly castor oil tree (Kalopanax septemlobus) which looks as if it is bleeding. It has been infected with honey fungus, which has wrapped itself tight around the trunk below the bark like a girdle. The girdle prevents the tree tissue from conducting water from the roots to the canopy. The syrupy excretion is the tree’s distress response.

Clockwise from top: Will Hinchliffe with a sweet chestnut (Castanea sativa); an Atlas cedar; and Jacquemont’s hazel (Corylus Jacquemontii)

‘The challenge for arboriculturists is that trees are being assailed on all sides. These giants of carbon sequestration are on the frontline of climate change, buffeted by winter gales, sucked dry by summer droughts’

RBGE.ORG.UK AUTUMN 2022 21 ARBORICULTURE

There is a huge emphasis within the Garden on biosecurity and the arboriculturists were practising Covidstyle precautions long before the pandemic. “It’s important we clean our tools and think about how we are moving plants within the collection because, as we move them, we move the organisms and diseases associated with them,” Hinchliffe explains.

As with Covid, though, the precautions don’t always prevent transmission. The blight-infected needles of another Atlas cedar are now turning pink. It was a neighbour to the one cut down in 2013, and the disease may have spread from there. “There are no fungicides licensed for use on amenity trees,” Hinchliffe says, “so all we can do is take a holistic approach: make sure the soil is good, look after the roots.”

“Will it recover?” He shakes his head. “I think it’s more a question of how long it has got. And in terms of curating the collection, you have to ask: ‘What value is a tree in poor condition like this? What ecology does it support? What role does it play in the landscape? Are there historic or sentimental reasons for keeping it?’” In any case, trees, like every living thing, are part of a cycle, the old fading away as the next generation comes to the fore. You can see it in the way the gnarled giants are flagging in the heat, while the saplings lap up the rays, and grow. “We have a queue of [younger] trees waiting to come out,” Hinchliffe says. “If we remove an old tree, we make space for something else.”

It might be assumed an arboriculturist would pay the greatest attention to the parts of the tree above ground, but its roots are its anchor and source of nourishment. Since the 1990s, scientists have understood that deep within the soil lies an almost mystical network created by the filaments from mycorrhizal fungi. This network allows the trees to communicate and transfer water, carbon, nitrogen and other nutrients and minerals from root system to root system.

The importance of tree roots and the soil has been uppermost in Hinchliffe’s mind as plans for the Garden’s ambitious £70m Biomes project progress. Soon the land around the Glasshouses will be a frenzy of construction activity. Some trees have already been moved to other locations, but the ones that remain require protection. An immovable fence has been built around them, and an ingenious bridge of steel piles and

beams submerged in the haul road so heavy vehicles can pass over the roots without damaging them.

The Biomes project is a necessity to avoid the loss of up to 4,000 plant species which are protected under glass. While the Garden was founded as a way to improve medical knowledge in Scotland, it now stands with others against the biodiversity crisis and climate emergency. “The climate is changing so rapidly, there are many trees here we will not be able to grow in 50 years, so we have to be much more forward-looking in what we are planting,” Hinchliffe says.

These are unchancy times, but whatever happens trees will be vital, not only to the planet as a whole, but for us as individuals seeking refuge from the elements.

“They play a fundamental role in making cities liveable,” Hinchliffe says, as we stand beneath the spoke-like branches of the Indian hazel.

“Here, in the middle of the city, on a really hot day, we can step into their shade. And it’s not just the shading effect: the trees are transpiring and, as they lose water, there’s an active cooling. Trees also intercept pollution, give shelter from wind and rain, and help us connect with nature.”

We step back into the glare of the sun and I take his point. As he returns to his office I head off in search of other great green parasols to dally under.

From alder to sycamore, find out how you could sponsor a tree at rbge.org.uk/treesponsorship

‘The climate is changing so rapidly, there are many trees here we will not be able to grow in 50 years, so we have to be much more forward-looking’

A dawn redwood (Metasequoia glyptostroboides); Will Hinchliffe prepares for work beneath a sweet chestnut

22 AUTUMN 2022 RBGE.ORG.UK ARBORICULTURE

DISCOVERING LIFE’S BUILDING BLOCKS

Our scientists are collecting and analysing Scotland’s flora for the Darwin Tree of Life project, which aims to sequence the DNA of all plants, animals and fungi in Britain and Ireland

The Garden’s scientists are busy working on a ground-breaking project that will transform our understanding of the natural world for generations to come.

The Darwin Tree of Life project, a collaboration between scientific organisations across the UK, aims to sequence the DNA of all 70,000 native species of plants, animals and fungi in Britain and Ireland. It is part of a larger initiative to sequence the genome of all complex life on Earth.

As one of 11 partner institutions, the Garden has been designated a Genome Acquisition Lab, responsible for collecting and identifying plant specimens, and sending the specially preserved samples to the Wellcome Sanger Institute in Cambridge for sequencing.

It begins with a plant

But how do scientists get to a plant’s DNA? Take, for example, Scotland’s national flower, the spear thistle (Cirsium vulgare), carefully collected in early summer by the Garden’s own Dr Markus Ruhsam, a botanist with more than 30 years’ experience.

From the selected plant, chosen for its new flushes of growth, Dr Ruhsam took several samples and a voucher specimen. While some of the samples were flashfrozen in liquid nitrogen for transport to the Wellcome Sanger Institute – for whole genome sequencing, assembly and annotation – another was dried and returned to base camp for analysis.

The voucher specimen was catalogued in the Herbarium, home to approximately three million specimens, where it will remain as a point of

Clockwise from above: spear thistle (Cirsium vulgare); sampling apples in the Garden; the Garden’s molecular ecologist Dr Markus Ruhsam working in the field

Clockwise from above: spear thistle (Cirsium vulgare); sampling apples in the Garden; the Garden’s molecular ecologist Dr Markus Ruhsam working in the field

24 AUTUMN 2022 RBGE.ORG.UK SCIENCE

FACT CHECK

DNA is the common thread that links all life on Earth, helping us understand biodiversity and evolution

70k 11 149 billion

reference if scientists need to examine the plant’s morphology further.

Meanwhile, the remaining sample was taken to our lab where Dr Laura Forrest, the Garden’s molecular laboratory manager, was ready to get to work extracting and sequencing a small section of DNA that will verify the sample as being the Cirsium vulgare that Dr Ruhsam first identified in the field.

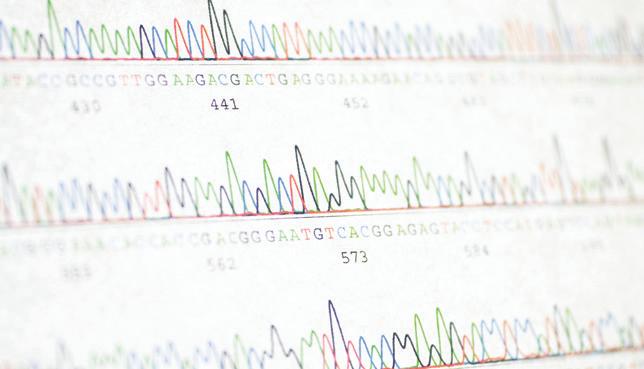

The process, known as DNA barcoding, outlined in the panel to the right, comprises several stages including extracting, amplifying and sequencing a small section of the DNA. The sequenced section of DNA, along with pictures of the specific plant, is then made public on an open-source database online.

Open-source data

Once fully sequenced, the Wellcome Sanger Institute will add the genomic data to another database. So far, mainly animals and insects have been fully sequenced – plant DNA is relatively hard to extract. Soon enough, all the data gathered by the Garden and partners will be freely accessible to researchers the world over. The material will be an eradefining resource and will likely play a major role in the ongoing battle against the effects of climate change.

Top 10

Institutions are working together to map the DNA of all complex life in Britain and Ireland

The Paris japonica plant has the world’s largest known genome, with 149 billion base pairs

HOW TO STUDY PLANT DNA

Dr Laura Forrest on DNA barcoding, the method we use to verify samples before they are sent to the Wellcome Sanger Institute for full genome sequencing

DNA extraction

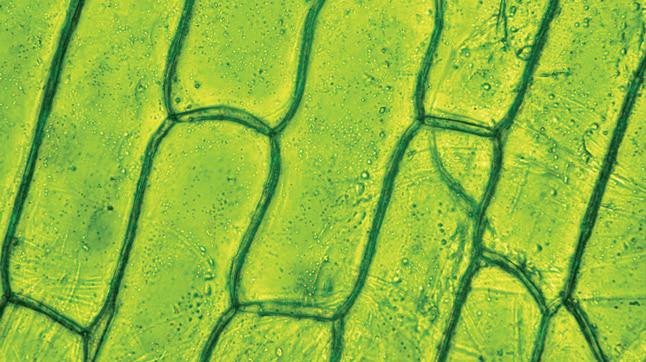

When extracting DNA from plants, you need to break down the cells’ walls. This can be done by brute force (a tungsten bead vibrating at 20 hertz) and chemistry (a buffer that pops open the cells’ membranes). You then separate the DNA from the solution and ‘wash’ away the material you don’t need.

Run a chain reaction

Primers are added to the sample –these are short strands of DNA that let you pinpoint the region you want to isolate. You then run a polymerase chain reaction (PCR), a method of amplifying the region of interest through heating and cooling, so that the sample finally contains multiple repeats of the same section of DNA.

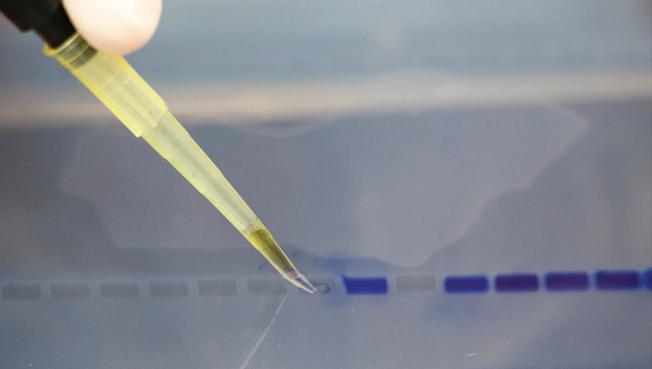

Gel electrophoresis

Next you want to find out how successful your extraction and PCR process has been before moving on to the sequencing stage. We use a method of gel electrophoresis, separating DNA molecules based on their size, which allows you to see how much amplified DNA you have. If you think there’s enough, you move on to the next step.

Sequencing

For barcoding, we send our samples to a lab at the University of Dundee for sequencing. When it returns, I like to check the sequencing manually, using a computer program. Then, you verify if the DNA matches the species, using an online database. Finally, you put the DNA analysis online, barcoding the plant for future cross referencing.

There are 72,572 known native species of plants, animals and fungi in Britain and Ireland The Scottish thistle is among the most nectarproducing plants in the UK

‘All the data gathered by the Garden and partners will be freely accessible to researchers the world over’

RBGE.ORG.UK AUTUMN 2022 25

1 3 2 4

The joy of giving

Discover locally sourced and sustainable gifts, including a specially commissioned new scarf by artist Annie Broadley, at the Garden this autumn and winter

Stationery

Our exclusively designed stationery includes a Lilian Snelling notecard set (£8) and a hardback journal featuring botanical works from the Garden collection (£14)

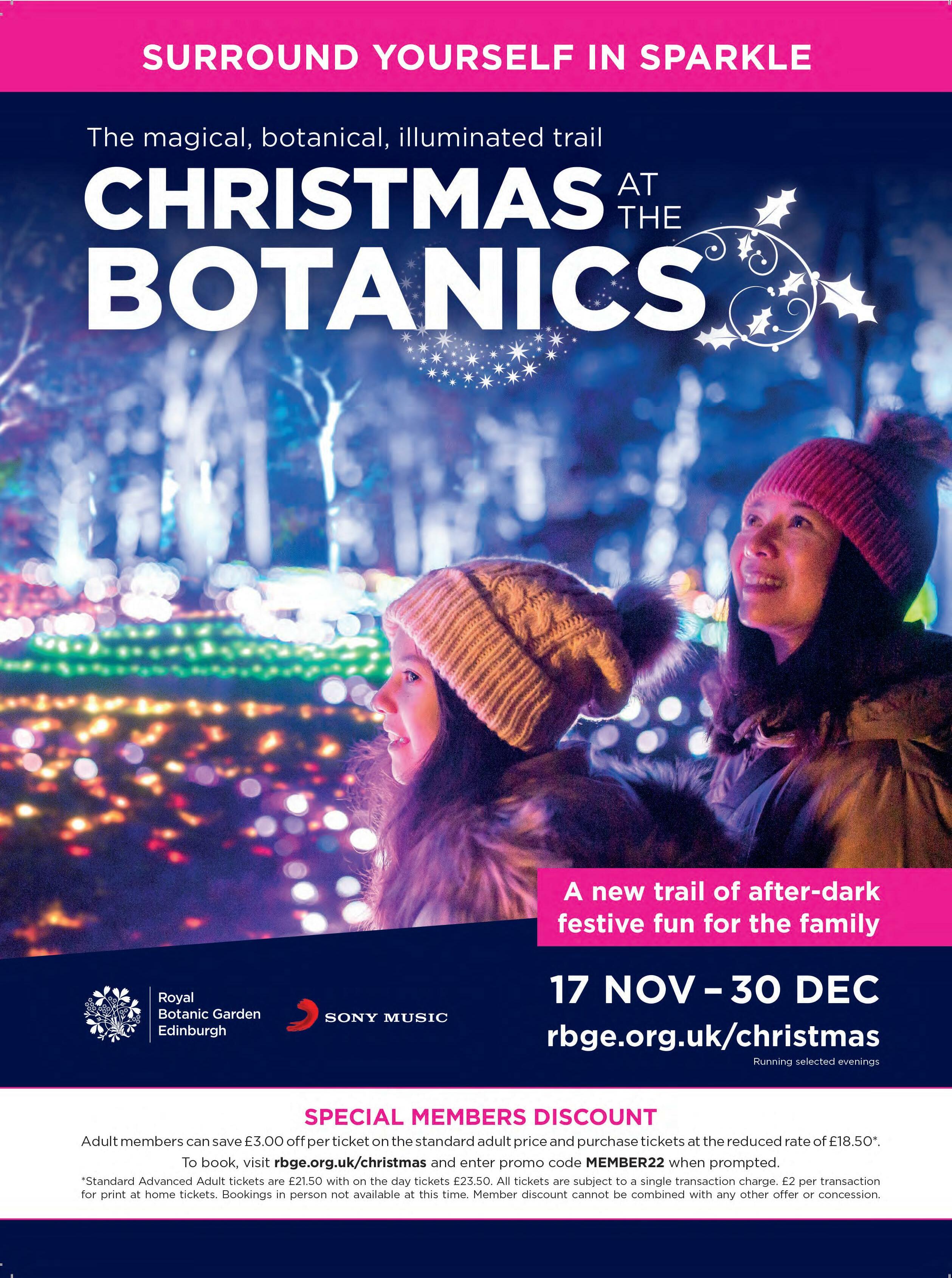

Members’ Christmas Shopping Days

Every year, as winter comes around, the Botanics Shop is transformed into a festive spectacle, full of great gift ideas for the whole family. Discover everything from locally sourced foodstuffs and beautiful knitwear to an exclusive unisex perfume. Prices range from £5 to £125.

Among the products on sale this year, we are excited to launch an exclusive new limited-edition scarf made in collaboration with Edinburghbased artist Annie Broadley (£125). This luxurious and colourful design was inspired by the artist’s autumnal walks in the Edinburgh Garden and

Bring your membership card to get a 15% discount on stock (some exclusions apply).

Edinburgh: 10 November Benmore: 30 October Dawyck: 17 November Logan: 30 October

includes details of the plants and wildlife she encountered there.

“I spent hours walking round the Garden and was drawn to the pond with its wonderful willow trees. These became the inspiration for this work,” says Broadley.

This limited-edition scarf, titled ‘By the River’s Rim’, is among a range of gifts available to buy from the Botanics Shop or at rbgeshop.org.uk

Knitwear

Visit the Botanics Shop to see our full selection of knitwear, including this hat (£51) and pair of gloves (£56)

Gardening

Discover a range of gardening gift ideas, including these robust gardening gloves (£21.50) and handy speedweeder (£8)

3 MORE GREAT GIFT IDEAS RBGE.ORG.UK AUTUMN 2022 27

GIFT GUIDE

ANATOMY OF A FUNGUS

Wild and woolly

Lactarius torminosus, known for its shaggy appearance and ‘tormenting’ the stomach, is seen in this painting by Constance Drummond-Hay from the Garden’s archives

1Lactarius torminosus, also known as the woolly milkcap, is a common and widespread fungus found in Europe, northern Asia, northern Africa and North America. It is a mycorrhizal fungus associated with birch trees, sharing moisture and nutrients via fungal strands and the tree’s roots.

2Although not clear in this watercolour, painted by Constance Drummond-Hay in 1899, the woolly milkcap has a distinctive fluffy appearance. The artist’s description notes that “[t]his Lactarius is very downy & shaggy” and “of a beautiful strawberry colour … also ochre Turning Pale.”

FUNGI FINDER

The Gardens host a wide variety of fungi throughout the year, particularly in the autumn. Look out for the woolly milkcap growing under birch trees. While you’re at it, watch out for redlead roundheads, cucumber caps, false chanterelles and many more.

3Despite its attractive appearance, the fungus’ species name – torminosus – implies it will torment the stomach. It is regularly eaten in Scandinavian countries after being salted, but we recommend you leave this one for the squirrels, unless you know what you’re doing.

4Constance DrummondHay collected the specimen in “[o]pen mossy plantation” in Pitlochry on 12 October 1899. The daughter of ornithologist Henry Drummond-Hay and great niece of botanist Lady Charlotte Murray, her bold watercolour paintings of wild Scottish fungi are now held in the Garden’s extensive art collection.

Constance Drummond-Hay, one of six siblings, was brought up in Seggieden, the Hay family home in Perthshire. Her date of birth is estimated to be around 1861. The sisters, all unmarried, were artistic and heavily involved in local church life.

28 AUTUMN 2022 RBGE.ORG.UK