CONSERVATION AND THE ENVIRONMENT IN NAMIBIA THE FIGHT AGAINST WILDLIFE CRIME THE NEXT STEPS FOR CARNIVORE CONSERVATION IN NAMIBIA CITIZEN SCIENCE FAIRY CIRCLES ABOUT FAIRIES OF ALL SIZES TRAFFICKED PANGOLINS GET A SECOND CHANCE BUT DO THEY SURVIVE? 2022

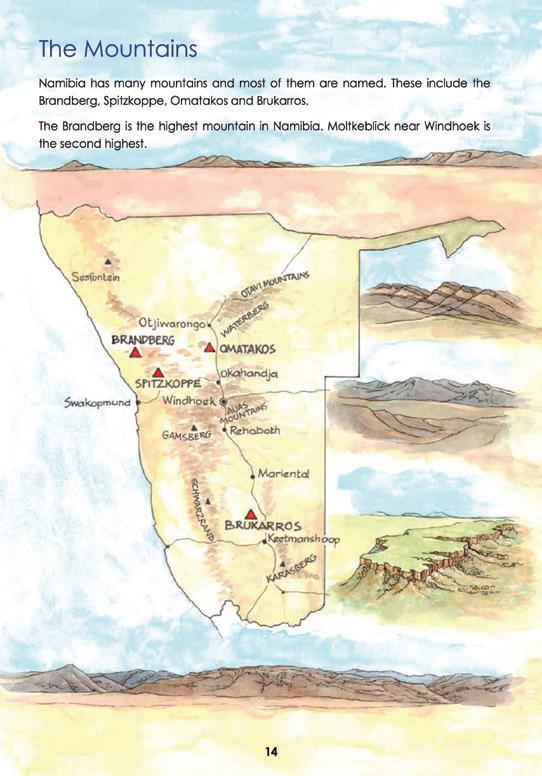

www.travelnewsnamibia.com 6.2 telephone lines per 100 inhabitants Freedom of the press/media GENERAL ENVIRONMENT INFRASTRUCTURE INFRASTRUCTURE PHYSICAL SOCIAL POPULATION TRANSPORT ELECTRICITY FAUNA FLORA DRINKING WATER TIME ZONES ECONOMY MONEY MATTERS TAX AND CUSTOMS 824,268 km² SURFACE AREA: Windhoek CAPITAL: 90% 21 March 1990 INDEPENDENCE: CURRENT PRESIDENT: Hage Geingob Multiparty parliament Democratic constitution Division of power between executive, legislature and judiciary Christian freedom of religion Secular state PERENNIAL RIVERS: Orange, Kunene, Okavango, Zambezi and Kwando/Linyanti/Chobe EPHEMERAL RIVERS: Numerous, including Fish, Kuiseb, Swakop and Ugab 20% 14 400 680 NATURE RESERVES: of surface area HIGHEST MOUNTAIN: Brandberg Spitzkoppe, Moltkeblick, Gamsberg OTHER PROMINENT MOUNTAINS: vegetation zones species of trees ENDEMIC plant species 120+ species of lichen LIVING FOSSIL PLANT: Welwitschia mirabilis Diamonds, uranium, copper, lead, zinc, magnesium, cadmium, arsenic, pyrites, silver, gold, lithium minerals, dimension stones (granite, marble, blue sodalite) and many semiprecious stones MAIN PRIVATE SECTORS: Mining, Manufacturing, Fishing and Agriculture 30% BIGGEST EMPLOYER: Agriculture FASTEST-GROWING SECTOR: Information Communication Industry MINING: ROADS: HARBOURS: Walvis Bay, Lüderitz MAIN AIRPORTS: Hosea Kutako International Airport, Eros Airport RAIL NETWORK: GSM agreements with 117 countries / 255 networks 37,000 km gravel 5,450 km tarred 46 airstrips 2,382 km narrow gauge TELECOMMUNICATIONS: Direct-dialling facilities to 221 countries MOBILE COMMUNICATION SYSTEM: Medical practitioners (world standard) 24-hour medical emergency services 1 4 medical doctor per 3,650 people privately run hospitals in Windhoek with intensive-care units EDUCATIONAL INSTITUTIONS: over 1,900 schools, various vocational and tertiary institutions bird species FOREIGN REPRESENTATION All goods and services are priced to include value-added tax of 15%. Visitors may reclaim VAT. The Namibia Dollar (N$) is fixed to and on par with the SA Rand. The South African Rand is also legal tender. Most tap water is purified and safe to drink. Visitors should exercise caution in rural areas. GMT + 2 hours 220 volts AC, 50hz, with outlets for round three-pin type plugs There is an extensive network of international and regional flights from Windhoek and domestic charters to all destinations. 2.5 million DENSITY: 2.2 per km² 420 000 inhabitants in Windhoek (15% of total) OFFICIAL LANGUAGE: 14 regions 13 ethnic cultures 16 languages and dialects English 92% ADULT LITERACY RATE: 2.6% POPULATION GROWTH RATE: BIG GAME: Elephant, lion, rhino, buffalo, cheetah, leopard, giraffe 20 antelope species 250 mammal species (14 endemic) 256 699 50 reptile species ENDEMIC BIRDS including Herero Chat, Rockrunner, Damara Tern, Monteiro’s Hornbill and Dune Lark frog species 15% Public transport is NOT available to all tourist destinations in Namibia. There are bus services from Windhoek to Swakopmund as well as Cape Town/Johannesburg/Vic Falls. Namibia’s main railway line runs from the South African border, connecting Windhoek to Swakopmund in the west and Tsumeb

the north. CURRENCY: Foreign currency, international Visa, MasterCard, American Express and Diners Club credit cards are accepted. ENQUIRIES: Ministry of Finance Tel (+264 61) 23 0773 in Windhoek More than 50 countries have Namibian consular or embassy representation in Windhoek. FAST FACTS ON NAMIBIA

in

PUBLISHING EDITORS

Elzanne McCulloch elzanne@venture.com.na Gail Thomson gailsfelines@gmail.com

PRODUCTION MANAGER

Liza de Klerk liza@venture.com.na LAYOUT Fiona Nandago fiona@venture.com.na CUSTOMER SERVICE

bonn@venture.com.na

PRINTERS

The editorial content of Conservation and the Environment in Namibia is contributed by the Namibia Chamber of Environment, freelance journalists, employees of the Namibian Ministry of Environment, Forestry and Tourism (MEFT) and NGOs. It does not necessarily reflect the opinions or policies held by MEFT or the publisher. No part of the magazine may be reproduced without written permission from the publisher.

CONSERVATION AND THE ENVIRONMENT IN NAMIBIA 2022 1

Bonn Nortjé

COVER IMAGE Kelsey Prediger, Pangolin Conservation and Research Foundation

John Meinert Printing, Windhoek

Conservation and the Environment in Namibia is published by Venture Media in

Hyper

Unit 44, Maxwell

Southern Industrial

Visit our website www.conservationnamibia.com CONSERVATION AND THE ENVIRONMENT IN NAMIBIA ALL FOR ONE AND ONE FOR ALL THE CONSERVATION RELIEF, RECOVERY AND RESILIENCE FACILITY A RIVER IN TROUBLE TEAMWORK AND SCIENCE ENABLES COEXISTENCE BETWEEN FARMERS AND CHEETAHS GLIDING INTO A BRIGHTER FUTURE ALBATROSSES AND NAMIBIAN FISHERIES 2021 CONSERVATION AND THE ENVIRONMENT IN NAMIBIA 2022

Windhoek, Namibia www.travelnewsnamibia.com Tel: +264 61 383 450,

City

street,

PO Box 21593, Windhoek, Namibia

ABOUT VENTURE Media

SHARING STORIES THAT MATTER.

That’s our mantra at Venture Media. Sharing stories, information and inspiration to an audience that understand and value why certain things matter. Why conservation, tourism, people & communities, businesses and ethics matter.

S H A R E Y O U R S T O R Y W I T H U S I N

How these elements interrelate and how we can bring about change, contribute to the world and support each other. Whether for an entire nation, an industry, a community, or even just an individual.

We find, explore, discover, teach, showcase and share stories that matter.

www.venture.com.na or email us at info@venture.com.na for a curated proposal.

T E L L , G R O W

2021, we're focussing on telling and sharing STORIES THAT MATTER acros riou tal p urney and share your s wi ders ertain things matter hica tion communities matter w t

ng about

ute

er for an entire nation mun dividual

In

elat

change,

ppor

o r e m a i l u s a t i n f o @ v e n t u r e . c o m . n a f o r a c u r a t e d p r o p o s a l W W W . V E N T U R E . C O M . N A

,

2 0 2 1

Elzanne McCulloch

from the PUBLISHER

We live in an interesting world during interesting times. A world where stories are shared far and wide, which sometimes is good and sometimes… not so much. In a recent conversation with Namibian conservationist and researcher John Mendelsohn I again realised the importance of sharing stories to an audience that appreciates them and understands why they matter. Yes, a TikTok video of a guy riding on a rhino in Namibia may get more views, but it is the antithesis of what we as Namibians, as conservationists and proponents of our country and its natural treasures, wish to achieve. We want to share the stories that matter with an audience that understands and appreciates the hows and whys

That is why it is such a pleasure and honour to be part of a publication such as this. A collection of stories written by authors, researchers, scientists and conservationists who stay true to the importance of conservation in Namibia and the reasons why our successes, as well as our shortcomings, are an integral part of our nation’s story and should be shared. So that others may learn from us and learn with us.

The pages of our 2022 edition of Conservation and the Environment in Namibia are packed with stories that matter We delve into our country’s tremendous successes in the fight against wildlife crime and the important role that partnerships and collaboration have played in it. Beyond the groundwork (which is tremendous), to preemptive arrests and successful persecution. As Helge Denker aptly points out: “In Namibia, wildlife crime clearly

doesn’t pay.” We follow Kelsey Prediger, our resident Pangolin Pro , as she continues her research on the world’s most trafficked mammal and on how to increase the efficacy of releasing liveconfiscated pangolins back into the wild. We get to know a group of young wildlife vets as they learn on the job and we discover more about carnivore conservation in Namibia, why tourism and conservation go hand in hand, how to be a Citizen Scientist and how to help diminish the scourge of invasive plant species. John Mendelsohn and his team also tackle the by now infamous Fairy Circle debacle.

We learn, we appreciate, we celebrate. Namibia is a country like few others, with conservation and environmental policies that have set us up for success. Our president has reaffirmed these commitments at COP27 and we look towards a future where our continued work, perseverance and commitment to our environment will enable us to remain a benchmark for protection of natural resources, wealth and heritage. A beacon of hope that others can strive to emulate.

So thank you to the writers for sharing your stories, and to the readers who appreciate them and understand why they matter.

Elzanne McCulloch

CONSERVATION AND THE ENVIRONMENT IN NAMIBIA 2022 3

Le Roux van Schalkwyk

Elzanne McCulloch

Elzanne McCulloch

ABOUT NAMIBIAN CHAMBER OF ENVIRONMENT

The Namibian Chamber of Environment (NCE) is a membership-based and -driven umbrella organisation established as a voluntary association under Namibian Common Law to support and promote the interests of the environmental NGO sector and its work. The Members constitute the Council – the highest decision-making organ of the NCE. The Council elects Members to the Executive Committee at an AGM to oversee and give strategic direction to the work of the NCE Secretariat. The Secretariat (staff) of the NCE comprise a CEO and Office Manager. Only the Office Manager is employed full-time. The NCE currently has 57 Full Members – Namibian registered NGOs whose main business, or a significant portion of whose business, comprises involvement in and promotion of environmental matters in Namibia; and 13 Associate Members – individuals running environmental programmes and non-Namibian NGOs likewise involved in local to national environmental matters in Namibia. A list of Members follows. For more information on each Member, their contact details and website link, please go to the NCE website at www.n-c-e.org/members

THE NCE HAS FOUR ASPIRATIONAL OBJECTIVES AND FIVE OPERATIONAL OBJECTIVES AS FOLLOWS:

Aspirational Objectives

• Conserve the natural environment

• Protect indigenous biodiversity & endangered species

• Promote best environmental practices

• Support efforts to prevent & reduce environmental degradation & pollution

Operational Objectives

• Represent the environmental interests of Members

• Act as a consultative forum for Members

• Engage with policy- & lawmakers to improve environmental policy & its

• implementation

• Build environmental skills in young Namibians

• Support & advise Members on environmental matters & facilitate access to

• environmental information

The NCE espouses the following key values:

• To uphold the fundamental rights and freedoms entrenched in Namibia’s Constitution and laws, including the principles of sustainable use, protection of biodiversity and inter-generational equity;

• To promote compliance with, uphold and share, environmental best practice, recognising that the Earth’s resources are finite, and that human health and wellbeing are inextricably linked to environmental health.

• To recognise that environmental best practice is best promoted by implementing the following seven principles: sustainability, polluter pays, precautionary, equity, effectiveness & efficiency, human rights and participation;

• To develop skills, expertise and passion in young Namibians on environmental issues;

• To ensure political and ideological neutrality, be evidence-based and counter fake information; and

• To promote inclusiveness and to fiercely and fearlessly reject any form of discrimination.

CONSERVATION AND THE ENVIRONMENT IN NAMIBIA 2022 5

AREAS:

1. Support to Members

The NCE provides office facilities, boardroom, internet and safe parking for its out-of-town Members when in Windhoek; in partnership with Westair, a Cessna 182 for conservation purposes such as aerial surveys, radio-tracking and anti-poaching work; three 4x4 Toyota Hilux double-cab vehicles for use by Members for their conservation work; registration and research permit facilitation; and any other support requested by Members.

2. National facilitation

The NCE organises symposia and workshops on topical and priority issues; supports the development of strategic Best Practice Guides at sector level, the first on mining, the second (in preparation) on hunting; reviews policy and legislation on and/or impacting Namibia’s environment; facilitates collaboration on conservation assessments and action plans, the latest being Namibia’s Carnivore Red Data Book; and representing the sector and Members on national bodies.

3. Environmental information

The NCE hosts and supports the development of Namibia’s Environmental Information Service (EIS at www.the-eis.com) in partnership with Paratus Telecom, a one-stop-shop for all environmental information on Namibia. The EIS comprises an e-library with over 18,000 reports, publications, maps, data sets, theses, etc., which are searchable and down-loadable. It provides an Atlasing platform for citizen science data collection that currently covers mammals, reptiles, amphibians, butterflies, invasive alien plants and archaeology, and records are conveniently entered via a free cell phone App. The NCE has also established a free, open access scientific e-journal –Namibian Journal of Environment – now in its sixth year (www.nje.org.na). The NCE and Venture Media recently launched a new environmental website “Conservation Namibia” (www.conservationnamibia.com) to tell Namibia’s conservation stories via blogs, factsheets, video and articles from this magazine. The NCE informs the public on topical environmental issues on its website (www.n-c-e.org), Facebook page and Twitter feed.

4. Environmental advocacy

The NCE addresses national threats to Namibia’s environment and natural resources by first attempting to work constructively with the relevant government or other entity but, if necessary, through public exposure. The NCE has addressed the issue of Chinese incentivised poaching and illegal trade in specially protected wildlife, the over-fishing of pilchards in Namibian waters, illegal and unsustainable timber harvesting and export, and the need to reduce and eliminate single-use plastic from Namibia’s environment. It has also initiated a highly successful Pangolin reward scheme in partnership with MEFT, some NCE Members and communities. The scheme rewards people for providing information on pangolin trafficking leading to arrests – more than 120 criminal cases opened and over 200 people arrested and charged.

5. Environmental policy research

When we talk about the “environment” we mean the interrelationship of ecological, social and economic aspects – essentially sustainable development. This is appropriate for a country with an economy reliant mainly on natural resource-based primary production where ecological and socio-economic issues are two sides of the same coin. However, this conceptual approach is rarely understood by people from western industrialised countries who think of environment as being just the green environment. To get around this problem, the NCE has established a socio-economic / livelihoods component that works seamlessly with the environmental component and focusses mainly on the urban environment. Over 50% of Namibians now live in towns and the city of Windhoek, with a projected rise to 70% by 2030. The priority areas

TO EFFECTIVELY IMPLEMENT THESE OBJECTIVES AND VALUES, THE NCE HAS DEVELOPED EIGHT STRATEGIC PROGRAMME

Elzanne McCulloch

of focus are access to affordable urban land for housing, appropriate sanitation, solid waste management, energy and research on the economics of poverty.

6. Young Namibian training and mentorship

Over the past five academic years the NCE in partnership with Woodtiger Fund has provided 140 post-graduate bursaries in the broad environmental field (including subjects such as environmental economics, environmental law, environmental engineering) and 41 internships, mainly for NCE bursary-holders, that involves close mentoring by experienced environmental professionals. The aim is to build the capacity and confidence of young Namibians to become the environmental leaders of tomorrow.

7. Fund raising

Core funding for the NCE is currently provided by B2Gold. This means that all additional funding received is invested directly into

MEMBERS

FULL MEMBERS

A. Speiser Environmental Consultants cc

African Conservation Services cc

Africat Foundation

Agra Provision (Agra Ltd)

Ashby Associates cc

Biodiversity Research Centre, NUST (BRC-NUST)

Botanical Society of Namibia

Brown Hyena Research Project Trust Fund

Cheetah Conservation Fund (CCF)

Conservancy Association of Namibia (CANAM)

Desert Lion Conservation Trust

Development Workshop Namibia (DW-N)

Earthlife Namibia Eco Awards Namibia

Eco-logic Environmental Management Consultancy cc EduVentures

Elephant Human Relations Aid (EHRA)

Environmental Assessment Professionals Association of Namibia (EAPAN)

Environmental Compliance Consulting (ECC) EnviroScience

Felines Communication and Conservation Consultants cc

Giraffe Conservation Foundation (GCF)

Gobabeb Research & Training Centre

Greenspace

Integrated Rural Development & Nature Conservation (IRDNC)

JARO Consultancy

Kwando Carnivore Project

LM Environmental Consultants

N/a’an ku sê Foundation

Namib Desert Environmental Education Trust (NaDEET)

Namibia Biomass Industry Group (N-BiG)

Namibia Bird Club

Namibia Nature Foundation (NNF)

Namibia Professional Hunting Association (NAPHA)

Namibia Scientific Society

Namibian Association of CBNRM Support Organisations (NACSO)

environmental projects and programmes – there are no overhead costs. The NCE focuses on corporate support and avoids targeting funding sources that may compete with its Members. The corporate sector assists with fund raising by approaching their clients, partners and networks. Our main sponsors are shown on the back cover.

8. Grants making

Funds raised by the NCE are used strategically to support priority environmental projects and programmes in Namibia. Emphasis is placed on legacy initiatives that have tangible outcomes. These are often based on national policy and bring together government and NGO partners, communities and the private sector, and frequently lead to investments by larger bilateral or multi-lateral funding organisations. An on-line grant application process allows NCE Members to apply for funding. To date 166 grants have been awarded, to the value of N$ 22.304 million, with 90% going to NCE Members. Some of these projects are showcased in this magazine.

Namibian Environment & Wildlife Society (NEWS)

Namibian Hydrogeological Association

NamibRand Nature Reserve Nyae Nyae Development Foundation of Namibia (NNDFN)

Oana Flora and Flora Omba Arts Trust

Ongava Game Reserve / Research Centre Otjikoto Trust Progress Namibia TAS cc Rare & Endangered Species Trust (REST) Research & Information Services of Namibia (RAISON) Rooikat Trust

Save The Rhino Trust (SRT) Scientific Society Swakopmund Seeis Conservancy SLR Environmental Consulting Southern African Institute of Environmental Assessment (SAIEA) SunCycles Namibia Sustainable Solutions Trust Tourism Supporting Conservation Trust (TOSCO) Venture Media

ASSOCIATE MEMBERS

Bell, Maria A

Black-footed Cat Research Project Namibia Bockmühl, Frank

Desert Elephant Conservation Irish, Dr John Kolberg, Herta

Leibniz Institute for Zoo & Wildlife Research Lukubwe, Dr Michael S

Namibia Animal Rehabilitation, Research & Education Centre (NARREC)

Seabirds & Marine Ecosystems Programme Sea Search Research and Conservation (Namibia Dolphin Project) Strohbach, Dr Ben Wild Bird Rescue

CONSERVATION AND THE ENVIRONMENT IN NAMIBIA 2022 7

Foreword

While it may take a village to raise a child, it takes a whole nation to conserve its natural environment. Many of the stories in this year’s magazine reach out beyond research and show how Namibians from all walks of life are getting involved in conservation.

You can join the growing number of citizen scientists by using a cell phone application to record animal and plant sightings. Turn to page 78 to find out how to download the Namibian Atlasing app and get started collecting information on a wide range of species. Technology is also a great way to get young people interested in the natural world, and was thus an important part of this year’s Earth Day event under the theme Shape Our Future (page 70). The young adults who participated in this event were inspired to collect biodiversity data and host their own conservation-related events in their communal conservancies.

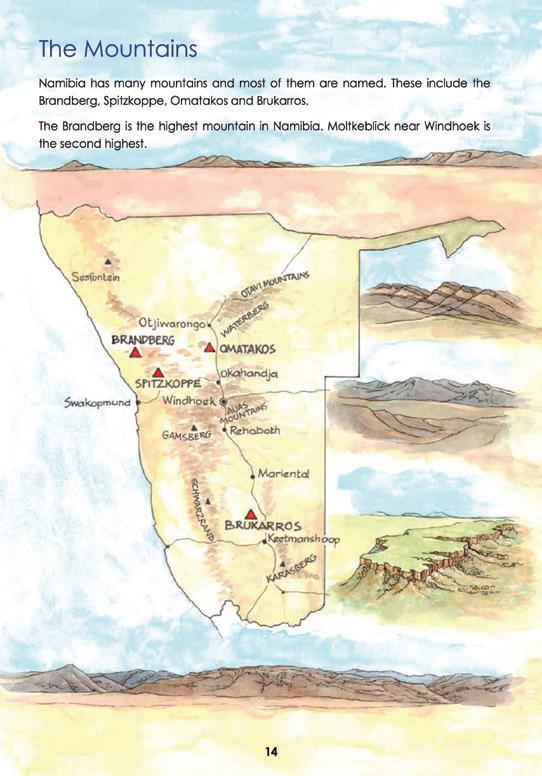

Once we know more about the state of the environment through data collection, we need to communicate it in a way that is both useful and engaging. Two brand new Atlases, presented on page 62, achieve this goal with hundreds of maps, charts, photos alongside informative text (for adults) and hand-drawn illustrations with simple explanations (for children). Another publication produced this year focuses on the 34 terrestrial carnivores of Namibia. It describes what we currently know about these species, what research gaps still need to be filled, and what we must do to ensure their long-term survival (page 28).

Lions are among the most difficult carnivores to live with, yet their survival in arid north-western Namibia relies on coexistence with local communities. The Lion Rangers programme (page 58) is one of many initiatives to conserve desert-adapted lions within the context of communitybased natural resource management. In a similar vein, Tourism Supporting Conservation (TOSCO, page 52) celebrates their first decade of existence, during which time they created closer links between the tourism sector and communal conservancies.

Conservation will ultimately succeed or fail to the extent that people understand environmental issues and are inspired to act. The Let Every Scale Count initiative (page 48) that links creative writing, art and pangolin conservation is a great example of how to raise public awareness about a serious problem – pangolin poaching and trafficking. Some of the stories written by children from all over Namibia (page 50) take a heart-breaking pangolin-eye view of being caught and trafficked alive. Rescuing live pangolins and releasing them into the wild is just part of the story, however, and new research (page 16) reveals that released individuals could be killed by other pangolins soon after release. Solving this problem demands a better understanding of pangolin habitat requirements and existing territories.

8

Beyond awareness and research, we need to prevent poaching whenever possible and pass strict sentences for wildlife crimes to deter future poachers. Namibia has launched a multi-pronged effort to tackle this challenge – increasing on-the-ground patrols, upgrading security in the national parks, improving investigations and prosecutions, and finally handing down stricter sentences in the courts (read all about it on page 12 and 42).

Two other less well-known, but nonetheless serious environmental problems in Namibia are presented here with calls for public participation and help. In The battle against invasive alien species in Namibia (page 64) members of the newly established Invasive Alien Working Group describe past and current efforts to remove alien plant species that are reducing groundwater and displacing indigenous species. The second threat is even more insidious, since most of us do not think about birds being killed on power lines that deliver electricity to our homes. Big birds, big power lines, big problems (page 74) calls attention to the problem and explores some potential solutions – including reducing our reliance on imported electricity.

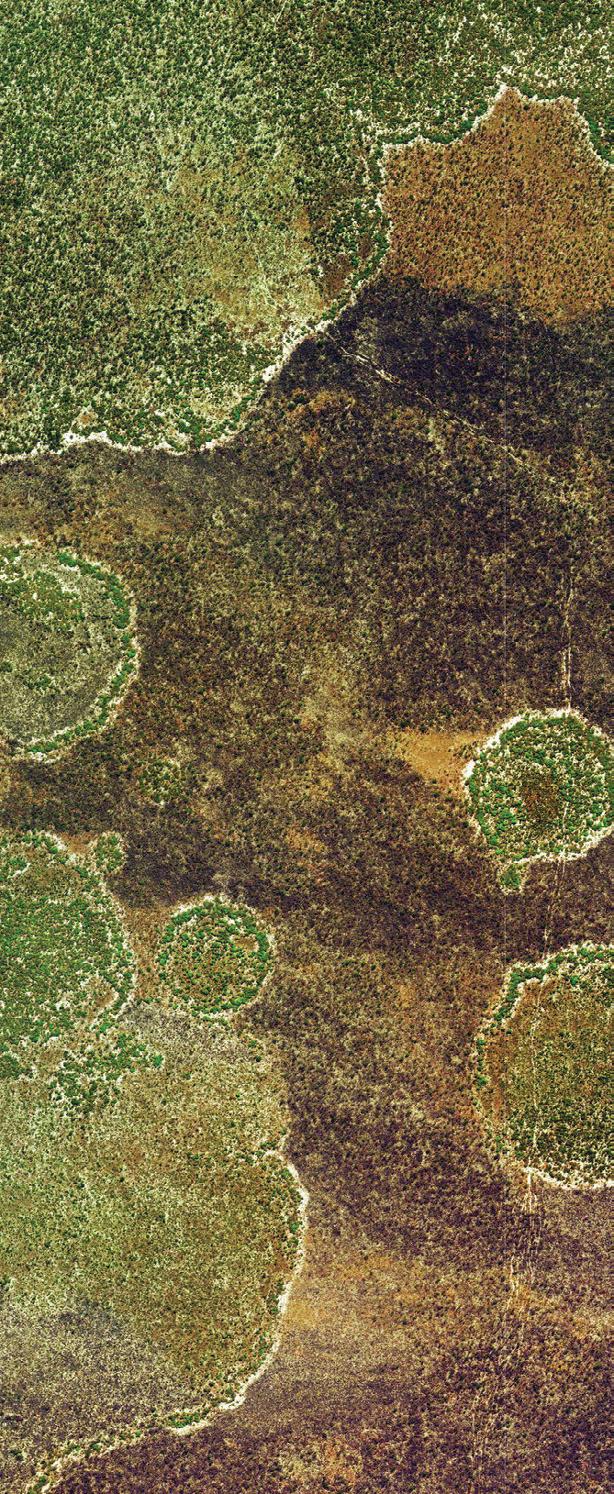

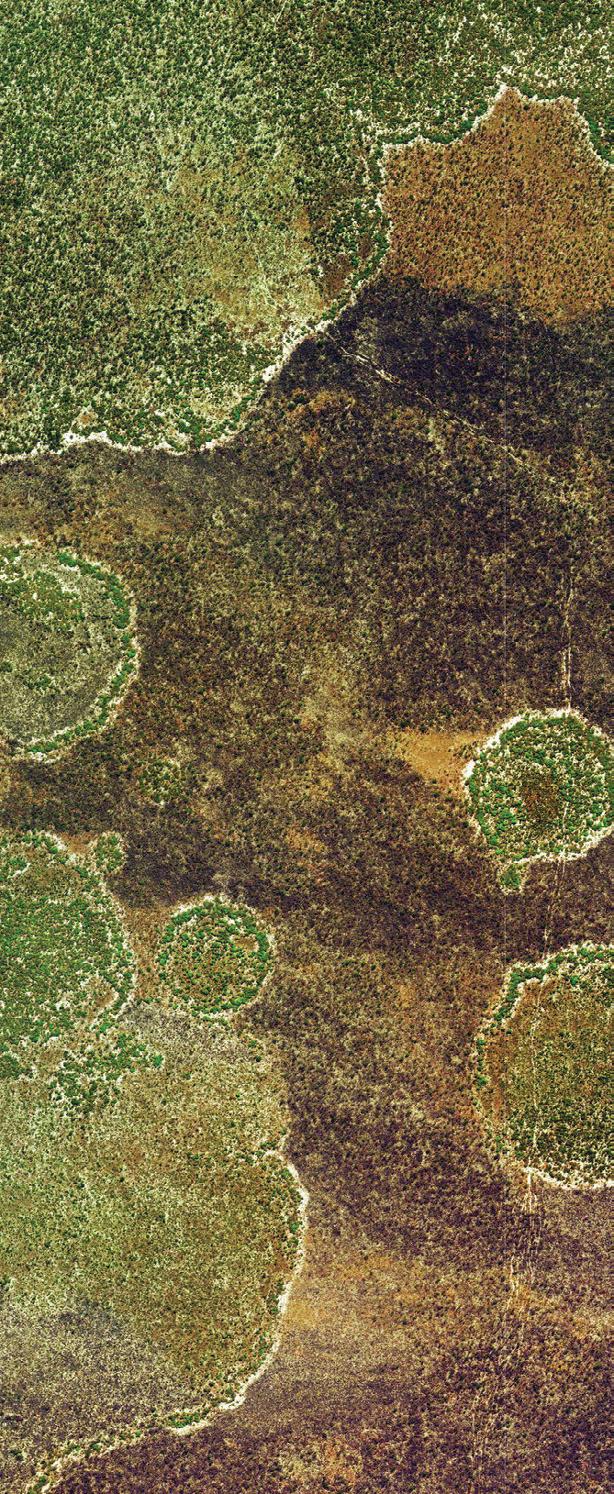

For a good news story, turn to page 22 to read about Namibia’s first ever specialist wildlife veterinary medicine course that included eight young veterinarians from Namibia and four other African countries. To tickle your curiosity, read About fairies of all sizes (page 34): going beyond the famous ‘fairy circles’ of the Namib to investigate other strangely circular natural phenomena in Namibia and Angola.

Conservation is everybody’s business. We are jointly responsible for leaving our environment in a better state than we found it. We hope that this edition of Conservation and the Environment in Namibia will inspire you to get involved in Namibian nature conservation. From collecting data on your phone to removing invasive alien plants in your neighbourhood, or simply using less electricity from the national grid – everyone can do something. Children, young adults, artists, scientists, rural community members, and dedicated senior citizens all feature in this year’s magazine as contributing to conservation in some way. You can too.

Yours in conservation

Chris Brown and Gail Thomson

Chris Brown and Gail Thomson

CONSERVATION AND THE ENVIRONMENT IN NAMIBIA 2022 9

Elzanne McCulloch

Conservation is the preservation of life on earth, and that, above all else, is worth fighting for.

Elzanne McCulloch

- Rob Stewart

Elzanne McCulloch

- Rob Stewart

From the Publisher 1 About Venture Media 2 About NCE 3 Foreword 6

Powerful deterrents against wildlife crime 12 Helge Denker

Trafficked pangolins get a second chance, but do they survive? 16 Kelsey Prediger

Taking African wildlife veterinary medicine to new heights 22 Giraffe Conservation Foundation and University of Namibia

The next steps for carnivore conservation in Namibia 28 NCE, LCMAN, and MEFT

About fairies of all sizes 34 John Mendelsohn, Elizabeth Shangano and Fillemon Shatipamba

Namibia is taking the fight to poachers and traffickers 42 WWF-Namibia

Let every scale count – Using creativity for pangolin conservation 48 Liz Komen

Bridging the gap between tourism and conservation: A decade of dreams, challenges and achievements 52 Lara Potma

Seeing lions in a different light – Lion Rangers and community conservation 58 John Heydinger

Getting to know Namibia with two beautiful new Atlases 62 Gail Thomson

The battle against invasive alien species in Namibia 64 Shirley Bethune, Petra Mutota, Lucrensia Ndeilitunga

Namibian Youth in Conservation are ready to Shape Our Future 70 Siphiwe Lutibezi and Ingelore Katjingisiua

Big birds, big power lines, big problems 74 John Pallett

Citizen science in Namibia 78 Alice Jarvis

NCE Supports 80

CONSERVATION AND THE ENVIRONMENT IN NAMIBIA 2022 11

contents

POWERFUL DETERRENTS AGAINST WILDLIFE CRIME

By Helge Denker

Temminck’s pangolin is the most-trafficked high-value species in Namibia - and pangolins are generally the most-trafficked wild animals worldwide. The animals are often trafficked alive and when seized from perpetrators can be released back into the wild. Vehicles used to transport illegal wildlife products are seized as instrumentalities and forfeited to the State – a painful additional punishment.

12

Environmental crime has exploded worldwide in recent years. According to a report by INTERPOL and UNEP 1 , environmental crime has increased at 2 to 3 times the rate of the global economy and is now the fourth-largest criminal sector after drug trafficking, counterfeit crimes and human trafficking. It is a massive problem, receiving massive attention. Similar trends are true for Namibia. Over the past decade, cases have skyrocketed from negligible to crisis levels –but over the past five years crime rates have been curbed through increasingly effective law enforcement.

Yet, catching criminals is only half the work. What happens to the arrested perpetrators? And what will deter environmental crime in the long run? Namibia may be finding at least some of the answers.

When independent Namibia was first confronted with modern, organised wildlife crime, the country was not prepared for the onslaught. After experiencing negligible losses while achieving significant conservation successes for more than 20 years, things changed rapidly and poignantly after 2010. Rhinos and elephants were particularly hard-hit, reaching a peak of 97 rhinos poached in 2015 and 101 elephants in 2016. Goaded by public outrage, including demonstrations in the streets, Namibia moved rapidly to counter the crisis.

National security forces were deployed to priority elephant and rhino ranges to help protect the animals. Maximum allowable penalties for wildlife crimes were substantially increased. New government departments were created, dedicated to wildlife protection and the investigation and prosecution of environmental crimes. The Ministry of Environment, Forestry and Tourism created a Wildlife Protection Services Division (MEFT, WPSD). The Office of the Prosecutor General launched an Environmental Crime Unit (OPG, ECU). Inter-agency cooperation between conservation, law enforcement and prosecution was strengthened with a law-enforcement focal point called the Blue Rhino Task Team, headed by the Namibian Police Force’s Protected Resources Division (NAMPOL–PRD) and the MEFT Intelligence and Investigation Unit (MEFT–IIU).

All of these interventions, facilitated through active support from international and local funding partners, helped to stem the tide of wildlife crime. Wide-ranging partnerships proved particularly important, as the government, non-governmental organisations, local communities and the private sector worked together to counter all forms of environmental crime. Losses of rhinos have been curbed appreciably and elephant poaching has been reduced to negligible levels (though the ivory from elephants poached in neighbouring countries continues to be seized in Namibia).

CONSERVATION AND THE ENVIRONMENT IN NAMIBIA 2022 13

Suspects arrested attempting to sell ivory to undercover investigators. The high number of cases and arrests resulting from the sudden spike in wildlife crime has led to a significant backlog in wildlife cases on the court roll.

The graph shows the decline in losses of elephant (purple bars) and rhino (pink bars) to poaching, compared to the increase in registered cases with arrests and seizures; green indicates all types of wildlife cases; red indicates high-value species cases (elephant, rhino, pangolin); black indicates meat-poaching cases (giraffe, buffalo, zebra, antelope, warthog).

For a time, meat poaching continued to increase, reaching a peak of 263 cases in 2019. This, too, has since been curbed by 30 per cent. Overall, registered wildlife crime cases have been reduced by one quarter over the past two years. Pangolin trafficking nonetheless remains one of the biggest current concerns, as little is known about the overall population status of Namibia’s pangolins, while trafficking has increased in step with international trends2. Numerous traffickers are being caught and live pangolins are being released back into the wild, but the drivers of the Namibian trade are poorly understood.

Effective law enforcement against an active criminal sector results in high numbers of arrests. Since 2015, more than 4,200 suspects have been arrested for various wildlife crimes in Namibia.

The rapid rise in the number of arrests and subsequent court cases has presented a new challenge, overwhelming an already stretched judiciary. Namibia already grappled with high rates of crime in other spheres, including homicide, domestic violence, fraud and corruption, burglary and armed robbery. The sudden massive expansion of the environmental crime sector resulted in a growing backlog of court cases, and the prosecution of suspects has lagged further and further behind arrests. This was not solely an issue of slow prosecution and case finalisation, however. Investigators, feeling they had achieved their goal of catching the criminals, often did not follow through effectively with further investigations and the finalisation of case dockets to ensure that these were trial-ready.

The Prosecutor General, Adv. Olyvia Imalwa, became increasingly concerned by these trends. The newly created Environmental Crime Unit was activated at the beginning of 2021 to whittle away at the backlog. The first step was to ensure that case dockets were trial-ready. The Head of the ECU, Adv. Jatiel Mudamburi, and his Deputy, Adv. Johannes Kalipi, conducted a thorough docket cleanup campaign, visiting nine Namibian towns to screen dockets and prepare them for trial.

The next step was to find a way to reduce the number of cases on the court roll in the various magisterial districts. It was decided that a Special Court would be needed to focus only on wildlife cases for an entire month. Based on wildlife crime prevalence, Katima Mulilo and Rundu were chosen as the priority candidates for the initiative.

Funding support was secured from the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, Space for Giants, TRAFFIC and Rooikat Trust. Prosecution teams were selected and dispatched, court space was secured, and on 1 April 2022 hearings began in both towns. The two teams worked tirelessly, far beyond official working hours and mandated court days, to prepare for each week’s court sessions and ensure that court delays were minimised.

Elephant tusks seized from a Zambian national who was attempting to sell the ivory in Namibia. Most of the ivory seized in Namibia originates from elephants poached in other countries. The finalised case resulted in a sentence of 126 months (10.5 years) in prison for the perpetrator

14

Team Katima Mulilo (from left to right): Mr Barry Buiswalelo Mufana – Magistrate; Ms Mildred Masiliso Ausiku – Clerk of Court; Ms Raonga Uanivi – Prosecutor; Ms Portia Kachana Mubonenwa – Interpreter; Sgt Muyambango – NAMPOL Court Orderly; Adv Johannes Mwatondandje Kalipi (ECU Deputy) –Supervisor; Mr Nabot Tangeni Charly Iyambo (ECU Member) – Prosecutor

Team Rundu (from left to right): Mr Peingondjambi Shipo – Magistrate; Marchell Hoeb (ECU Member) – Prosecutor; Ms Rovisa Marengi –Interpreter; Mrs Adrie Rickets (ECU Member) – Prosecutor; Const Muruti –NAMPOL Court Orderly; Adv Jatiel Mudamburi (ECU Head) – Supervisor; not present Ms Maria Ruben – Clerk of Court.

The operation entailed complex logistics, such as the transportation of accused to and from the courtrooms, ensuring the availability of witnesses and coordinating legal representation, among much else. Logistical challenges were overcome through active collaboration among regional NAMPOL and MEFT personnel and the prosecution teams, with support from Rooikat, Blue Rhino, the Directorate of Legal Aid within the Ministry of Justice, and the Law Society of Namibia. Highly committed interpreters, clerks of the court and court orderlies facilitated the daily court sessions.

The results produced by the end of April were tremendous. Cases were rapidly concluded throughout the month, with stern sentences being served. Noteworthy penalties include 9 years direct imprisonment for pangolin trafficking, a fine of N$ 800,000 or 8 years imprisonment for ivory trafficking, and 12 years direct imprisonment (with 3 years suspended) for ivory trafficking. Charges in these cases included transgressions against the Prevention of Organised Crime Act. A number of noteworthy penalties of up to 5 years in prison were also handed down in meat-poaching cases. These sentences serve as a powerful deterrent.

In addition, the vehicles and firearms used to commit the crimes were forfeited to the State along with the confiscated wildlife products. The loss of expensive four-wheel-drives or flashy sedans is a painful additional penalty for convicted criminals. A total of 5 cars and 16 firearms were forfeited in the course of the month. Between the two courts, 80 cases were finalised; 68 of these as convictions (a conviction

rate of 85 per cent). The achievements of one month compare very favourably with the results of entire past years.

In Namibia, wildlife crime clearly does not pay. The chances of being caught are high. Through effective investigations and law enforcement, numerous poachers are being caught – many even before they manage to kill an animal. Rapid investigations following a poaching incident are resulting in high success rates in solving cases. Ongoing investigations into old cases continue to lead to more arrests – and convictions. Wildlife crime cases are now receiving priority attention from the judiciary. The dedicated efforts of the Office of the Prosecutor General, in close collaboration with investigators, are ensuring that arrests lead to convictions. Offenders are facing justice, and that includes stern sentences.

Namibia has worked hard to ensure healthy wildlife numbers, in many cases rebuilding the populations of vulnerable species from historic lows. This has enabled the tourism and conservation hunting industries – both based on abundant wildlife, intact ecosystems and sound conservation structures – to become two of the most important economic sectors in the country. The Namibian conservation, law enforcement and judiciary spheres are now working equally hard to ensure that those gains are not eroded by the greed of selfish criminals. Together, Namibia’s collaborative efforts, bolstered by ongoing support from the international community, are creating a powerful deterrent against wildlife crime.

Notes

1

2

CONSERVATION AND THE ENVIRONMENT IN NAMIBIA 2022 15

Nellemann, C. et al. 2016. The Rise of Environmental Crime – A Growing Threat To Natural Resources, Peace, Development And Security. A UNEP-INTERPOL Rapid Response Assessment, p. 4. United Nations Environmental Programme and RHIPTO Rapid Response – Norwegian Centrer for Global Analyses.

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. 2020. World Wildlife Crime Report 2020: Trafficking in Protected Species, p. 66. UNODC, Vienna.

16

First GPS/SAT tagged pangolin in Etosha National Park

Kelsey Prediger, Pangolin Conservation and Research Foundation)

TRAFFICKED PANGOLINS GET A SECOND CHANCE,

BUT DO THEY SURVIVE?

By Kelsey Prediger, Pangolin Conservation and Research Foundation

In recent years, pangolins have become the most trafficked animal in Namibia. According to national wildlife crime reports, 491 pangolins (152 live and 339 carcasses or skins) were confiscated and 640 arrests were made in the last seven years (2015-2021, MEFT statistics).

Pangolins are poached for their scales, body parts, and meat for traditional beliefs, medicine and food worldwide. In recent years there is rising pressure on the species primarily due to their scales being used in Traditional Chinese Medicine. For nearly 80 million years their scales have protected them against predation. Now it is a reason for which they are killed.

CONSERVATION AND THE ENVIRONMENT IN NAMIBIA 2022 17

About 30% of the poached pangolins were still alive when their traffickers were caught. These pangolins are often weak and medically compromised, as they have been held in captivity for days or weeks without any food or water. Pangolins only eat live ants and termites in their natural habitat, which makes them hard to cater for even after they are confiscated. After a quick health check and treatment by a veterinarian approved by the Namibian Pangolin Working Group (NPWG), the animals are released. What we don’t yet know is how long these pangolins survive after their release.

Why are releases not always successful?

There are several reasons why releasing pangolins is a challenging task. Firstly, we do not understand where resident pangolins have already established home ranges. Secondly, trafficked animals have often gone through a great deal of trauma and often use their remaining energy to appear strong and “escape”. Finally, we are still working out how to determine what type of resources and habitat the released individuals need to survive. Rarely does the wildlife crime suspect reveal where they first caught the pangolin, making it impossible to know which area or habitat it came from.

Preliminary research shows us that pangolins are highly territorial towards individuals of the same gender, similar to the social structure of leopards. The core area of one pangolin does not overlap with another of the same sex. While there is some overlap on the outer edges of their territories, it is likely that neighbours will use these areas at different times.

When two pangolins of the same sex encounter each other, they will fight to defend their territories. They use their sharp, strong claws to scratch, slice, and pull at one another. Common injuries are at the base of the scale where it splits from the skin due to pulling by the opponent. They also target the soft underside and genitals of their opponents. Fighting injuries are common, but resident pangolins are usually healthy enough to recover. Newly released pangolins that have only just recovered from being caught up in the illegal wildlife trade are at a major disadvantage to residents.

Resident pangolins are hard to detect and often we know nothing about pangolin populations at release sites. If a pangolin is released in the middle of a resident’s territory, it will likely be beaten up if it does not move out soon. One of the Pangolin Conservation and

Research Foundation (PCRF)’s projects is collecting sightings and signs of pangolins to find out more about resident populations at potential release sites in an effort to address this challenge.

How are pangolins monitored?

To find out how released pangolins are faring, the PCRF started a research project in collaboration with the Ministry of Environment, Forestry, and Tourism (MEFT). Released pangolins are tagged with GPS satellite transmitters and VHF radio transmitters to track their movements and behaviour soon after release. They are caught and weighed at regular intervals as a measure to establish how well they are doing – an individual that has settled in well and started foraging is expected to gain or maintain their weight.

The data on the movements of the animal, sent to us by the satellite transmitter, can be viewed on a laptop or cell phone. We can thus remotely view the pangolin’s movement patterns, indicating matters like dispersal (moving out of a territory), death, and poaching. The VHF transmitter allows us to physically locate the animal on the ground to check its weight, body condition, foraging habits, and burrows used. Foraging samples are collected to record dietary preferences in different habitats. Remotely-triggered camera traps are deployed at burrows to monitor the activity and presence of resident pangolins.

The results of this project will inform the development of release, softrelease, and post-release monitoring guidelines for the species. This is the first project in Namibia to collect detailed data on survival, which is connected to the research on the ecology and genetics of resident pangolins across Namibia. These research findings should improve our understanding of pangolins and increase the survival rate of those that are confiscated alive from the illegal trade.

How do we know if a pangolin is dispersing or settling down?

Once a pangolin is tagged and released, we monitor its movements to find out if it leaves the area where we released it (i.e. disperses) or if it settles down and starts to forage. Dispersal indicates that the release site was within another pangolin’s territory, or not suitable for the released animal for some other reason. Settling down and foraging shows that the area is an available territory and contains enough food and burrows.

18

Kelsey Prediger, PCRF

These wounds between the scales of a pangolin were caused during a territorial fight with another pangolin, which is one reason why released pangolins may not survive.

On a map generated by a tag, dispersal looks like constant moving with fairly long distances between GPS points which are set to hourly fixes, showing that the animal is doing little or no foraging along the way. If an animal finds what it considers to be a safe burrow, it shows centralised movement patterns – they go back to the burrow each morning and move around its vicinity at night. Foraging patterns look like zigzags across the map, and the individual covers much smaller distances over time than during dispersal.

These movements immediately after release can be the difference between life and death. Individuals that do not settle down will lose weight rapidly and be exposed to heat stress because they are not resting in a burrow during the heat of the day. Using this knowledge, we can re-capture these animals and put them through a soft-release or rehabilitation programme to improve their physical condition and gain strength before they go back into the wild.

What has happened to pangolins released in reserves and parks in Namibia?

The first monitored releases on a private nature reserve in 2018 and 2019 were unsuccessful. Three individuals left the reserve within seven days of release, and one died as a result of injuries from fighting with residents. The animals were released before we knew anything about resident pangolins in the area. Since then, we have discovered tightly packed pangolin home ranges across the reserve, leaving little room for new individuals.

Since 2021, five GPS-tagged pangolins have been released into National Parks (Khaudum, Etosha and Bwabwata) and six onto

private land. This work is made possible by the close collaboration between stakeholders in pangolin conservation which was sparked by the NPWG, with post-release monitoring conducted by the PCRF and MEFT.

Three of the five individuals were released in the same areas of Etosha National Park at different times. Their post-release movements show mixed results. The first one, released on 12 March, initially showed centralised movement and foraging patterns, and the first weight check revealed that this male had gained a healthy 1.5 kg. For unknown reasons, however, it dispersed soon after the weight check. The tag on this individual has stopped working, so we do not know if it has settled in a new area.

The second pangolin, a male that was released on 29 March, demonstrated dispersal movement patterns for the first two weeks before finally appearing to settle. During the dispersal, the transmitter often checked in all day and tag temperatures reached up to 40°C – indicating that the pangolin was not finding burrows for refuge, or they were very shallow, offering no relief from extreme temperatures. A weight check on 5 May showed he had lost 2 kg (over 20% of total weight) since the time of release, and he was found dead on 16 May. It is likely that the constant movement without sufficient refuge led to the severe weight loss and finally death.

The latest pangolin, released on 15 September, dispersed 5 km in one night but has since settled in an area and is demonstrating centralised foraging patterns. This individual will be monitored as long as the tag is active; new tags will be fitted to track its long-term survival.

CONSERVATION AND THE ENVIRONMENT IN NAMIBIA 2022 19

Kelsey Prediger, PCRF

The sign of a truly successful release is reproduction. This camera trap photo shows a released female with her pup.

Centralised movement and foraging patterns shown by a released pangolin over a two-week period; it later dispersed.

Dispersal pattern of a released pangolin, which died at the end of this period.

20

Learning from past releases to improve pangolin survival

Post-release monitoring is just one aspect of pangolin conservation in Namibia. The work of the Blue Rhino Task Team, the Ministry of Environment, Forestry, and Tourism, and the Namibian Police is crucial to reduce pangolin poaching in the long term. Since releasing a confiscated pangolin is far from straightforward, the ultimate solution is to prevent poaching and keep pangolins in their home ranges. However, for as long as there are live trafficked pangolins, we will need to continuously improve their survival chances after rehabilitation and release.

Results from this project are reported back to the MEFT and the NPWG to inform conservation management planning. The NPWG has drafted the first Conservation Management Plan for pangolins in Namibia, which is slated for approval this year. Based on our findings, standard operating procedures for release, soft-release, and post-release monitoring will be developed to improve success rates of releasing confiscated pangolins.

Ideally, all live-confiscated individuals should be monitored until they have established a home range in their release site and remained there for more than six months. A higher bar for success, which would require even longer monitoring times, would be to show that the released individual has reproduced in its new home. To achieve this goal, more funding is needed to fit and replace tags during the monitoring period. This information would then be fed back into the guidelines for pangolin releases, ultimately improving the chances of survival for trafficked pangolins.

How can you help?

Consider donating to the NPWG emergency veterinary care fund or PCRF to support the care and release of these live-confiscated animals. Share what you have learned with others, as there are still many people who don’t know what a pangolin is! These relatively unknown animals provide valuable ecosystem services by consuming large numbers of ants and termites and they are an important part of Namibia’s natural heritage.

Acknowledgments

Kelsey Prediger is the Founder and Executive Director of the Pangolin Conservation & Research Foundation, the secretariat of the NPWG, and the co-chair for southern Africa of the IUCN SSC Pangolin Specialist Group. This research was conducted through multiple projects under her leadership with support from Novald Iyambo, Piet Beytell, Kenneth Uiseb, and Lovness Ndeiweda of MEFT, Dr. Morgan Hauptfleisch of the Namibia University of Science and Technology (NUST), Dr. John Irish of the National Museum, and Dr. Monique MacKenzie and Dr. Lindesay Scott-Hayward of the University of St. Andrews in Scotland. The Namibian Pangolin Working Group has also supported this project through their work on streamlining the process for live-confiscated pangolins. Rooikat Trust and the Namibian Chamber of Environment (NCE) have contributed to the veterinary care of animals. Generous financial and logistical support was received from NCE, Namibia2Go, B2Gold, Total, the Pangolin Consortium, the University of St. Andrews, NUST, MEFT, the Oak Foundation, Varta Batteries Namibia, Namib Tyre, Van Rensburg Holdings, Camp Hire Namibia, Otto Herrigel Environmental Trust and Bushwhackers.

CONSERVATION AND THE ENVIRONMENT IN NAMIBIA 2022 21

Release sites and movement patterns of three pangolins in Etosha National Park. They are numbered in the order of their release.

TAKING AFRICAN WILDLIFE VETERINARY MEDICINE

TO NEW HEIGHTS

22

Text and Images by Giraffe Conservation Foundation

Have you ever darted a giraffe from a helicopter or moved a sable antelope? Have you fitted a satellite tracking device to an elephant or a gemsbok? And have you done all of this in a single day? Eight young African wildlife veterinarians who recently participated in a 10-day hands-on training course would answer with a resounding YES!

During a highly interactive time in the field at the Etosha Heights Private Reserve, these young veterinarians worked hand-in-hand with several highly experienced Namibian and international wildlife veterinarians. They gained valuable experience in wildlife capture, collaring, tagging, moving of animals and much more, while at the same time supporting the conservation management of one of Namibia’s largest private reserves.

As the wildlife conservation field evolves to cover multiple disciplines and a more holistic approach, the wildlife veterinarian has become a critical member of any team. This branch of veterinary medicine, however, is highly specialised and difficult to master, because of the diversity of species which a wildlife vet is likely to encounter – each with a unique anatomy and physiology. Darting, anaesthetising and treating a giraffe is a very different proposition to doing the same to an elephant or rhino or large carnivore, for example.

Compared with domestic animals, we have very little information on veterinary care and treatment for each of these species, making this branch of veterinary medicine particularly challenging. Even more concerning is the fact that most wildlife veterinarians enter the field with little knowledge in safe handling of dangerous drugs, darting and capture equipment, and appropriate protocols for handling wildlife, as these topics are not generally part of their university training.

Wildlife vets operating across the African continent are frequently required to work in remote and isolated settings, often with limited experience, practical skills, networks, or confidence to handle wildlife safely. Unfortunately, training opportunities in African wildlife restraint and immobilisation are limited and the cost is prohibitive to most. This places most African veterinarians at a distinct disadvantage, and often results in many African state wildlife departments and conservation organisations being forced to bring in external expertise – often from Southern Africa – rather than developing or enhancing their own local wildlife veterinary capacity. However, this is quite different in Namibia.

The University of Namibia (UNAM) School of Veterinary Medicine, established in 2015, is one of just a few veterinary schools in Africa that offer a solid introduction to wildlife medicine. Veterinarians who graduate from UNAM are equipped to enter the field with a practical working knowledge of the specialised drugs used in wildlife capture as well as species-specific protocols, use of specialised capture

CONSERVATION AND THE ENVIRONMENT IN NAMIBIA 2022 23

equipment, and important legislative requirements for working with wildlife in Namibia. Furthermore, there is a broad and diverse network of highly experienced wildlife professionals (both veterinarians and conservationists) working in the country. As a result, Namibia is well placed to not only support local capacity building among Namibian wildlife vets and conservationists, but to also build the capacity of wildlife vets from other parts of Africa.

As the global leader in giraffe conservation, the Giraffe Conservation Foundation (GCF) currently implements and supports giraffe conservation initiatives in Namibia and 18 other African countries, often working closely with wildlife veterinarians. “Giraffe can be particularly difficult to immobilise due to their unique physiology,” says Dr Julian Fennessy, GCF’s Director of Conservation. “To ensure their safety, we often bring in vets from Namibia or South Africa if there is not sufficient experience in the country. The problem is not a lack of local vets, but often there is limited expertise in handling wildlife or simply a lack of confidence – confidence that can only be developed through practical experience. This is why we initiated discussions around a course for African wildlife vets here in Namibia.”

With this idea in mind, the GCF team approached potential partners in Namibia to develop the inaugural African Wildlife Veterinary Course. GCF, in collaboration with UNAM and the Namibia University of Science and Technology (NUST) – with the support of the African Wildlife Conservation Trust (AWCT), the Wildlife Conservation Alliance, and the Ministry of Environment, Forestry and Tourism (MEFT) – developed a dynamic, practical wildlife veterinary immobilisation course for young African vets. Over time, this course should create a network of capable African wildlife vets who can support multiple conservation projects and help each other through information exchange.

24

Tagging giraffe is a challenging operation. The immobilisation drugs have been reversed immediately and the giraffe is fully awake. The vets in charge collect samples, check on vitals and record all data before releasing the giraffe.

This waterbuck is blindfolded to reduce stress before it is moved to a different game camp within the Etosha Heights Private Reserve.

The training kicked off with a three-day intensive lecture series in Windhoek and was open to all Namibian vets for their continuing professional development. Specialist lectures ranged from general physiology and pharmacology to species-specific protocols and human safety considerations to wildlife medicine legislation. Experienced wildlife vets facilitated discussions by sharing different experiences from Namibia and other African countries, particularly related to varied drug and equipment availability, the ethics of wildlife tagging, policies and legislation, conservation science and management, and importantly, partnership development. Participants were brought upto-date with the latest developments and ideas in wildlife veterinary medicine and had the opportunity to reconnect with many familiar faces as well as establish new professional connections.

“Wildlife in Africa can ultimately only be conserved by African people – they simply need the relevant skills and opportunities to do this effectively,” says Dr Sara Ferguson, GCF’s Conservation Health Coordinator and lead veterinarian during the course. “Upskilling young Africans is an important step towards this goal and it is particularly important for wildlife veterinarians, who play a critical role in conservation,” she adds.

Following the lecture series, eight aspiring wildlife vets from the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Mozambique, Namibia, Tanzania and Uganda, four members of the MEFT game capture team, four wildlife ecologists and seven highly experienced wildlife vets travelled to Etosha Heights Private Reserve adjacent to Etosha National Park for the 10-day practical section of the course. Most newly-graduated veterinarians are uncomfortable taking responsibility for procedures they have not performed yet, so this practical exercise on a variety of common African species allowed them to learn by doing. Participation of international vets was made possible through the Namibia

CONSERVATION AND THE ENVIRONMENT IN NAMIBIA 2022 25

After a successful immobilisation and tagging, the young vets look on as the oryx finds her feet and runs off.

Dr Hagnesio Chiponde from the Mozambique Wildlife Alliance demonstrates how he stabilises his hands when filling a dart with drugs, while Drs Joshua Lubega (GCF, Uganda), Israel Amuthitu (UNAM, Namibia) and Dominique Tshimbalanga Mukadi (African Parks, DRC) look on.

The team tags an oryx and at the same time collects samples, measurements and checks on the animal’s vitals.

“The old adage ‘I hear and I forget. I see and I remember. I do and I understand’ is particularly relevant in the wildlife veterinary arena, for it is only through the actual acts of planning and executing the immobilisation of a wild animal that the veterinarian fully hones his or her skills in the face of challenging situations.” says Dr Mark Jago, Senior Lecturer at UNAM’s School of Veterinary Medicine. “It was a privilege to be part of something where young vets from around the African continent demonstrate knowledge, passion and skill in abundance, and there are few things as rewarding as being part of an opportunity for passionate professionals to take their skill set to the next level.”

During the hands-on training each of the aspiring African vets took the lead during the immobilisation of at least one animal

under the guidance of one of the expert vet mentors. Prior to each immobilisation, drug protocols and appropriate darting equipment were discussed, and each operation (on the ground or helicopterbased) was carefully planned and executed. Open debriefing discussions after each immobilisation offered ample opportunity for a peer-to-peer skills exchange, analysis of what worked well and what did not, including the effects of different drug regimens used for comparison.

During these discussions the participants often became the teachers based on their own experiences, thus creating a conducive and productive training environment. Each of the African wildlife vets brought a host of real-life experiences from their respective workplace and country to the discussions. This cohort of trainees now has an important network of peers for future information exchange, and an impressive resource of knowledge to tap into when back home.

26

Veterinary Council granting temporary registration for the duration of the field course.

DR TSHIMBALANGA’S STORY

Dr Dominique Tshimbalanga, a DRC vet, shared his story: “I always wanted to get involved in wildlife veterinary medicine, but in the DRC this was difficult. When I managed to secure a position with the African Parks Network (APN) in Garamba National Park, I was very excited. However, while I was based in a core wildlife area, I was in charge of the canine unit. I looked after the anti-poaching dogs that were used in the park. For any wildlife work, APN brought in vets from South Africa and Europe and I was mostly not even allowed to shadow them. This was becoming increasingly frustrating and I was almost ready to give up on my dream. But then things changed and I was invited by GCF to participate in this amazing course in Namibia. I learnt so much and now have a network of peers to discuss any questions I may have – and I do have many now that I have been promoted to Resident Veterinarian in Garamba National Park. This promotion was a direct result of gaining new skills and hands-on experience during this course. GCF has given me the key – now it is up to me to use it!”

Dr Tshimbalanga’s story is more than enough reason for us to hold more courses of this kind in future. Ultimately, we aim to empower young African wildlife vets to become the next leaders in conservation and secure a bright future for wildlife conservation efforts in Namibia and throughout Africa.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Participation of the eight African vets was fully funded through the Giraffe Conservation Foundation. The field course was generously supported by the African Wildlife Conservation Trust (AWCT), which kindly made its helicopter available for the training. AWCT, African Wildlife Services, MEFT, UNAM’s School of Veterinary Medicine and Wildscapes Veterinary provided valuable veterinary technical skills and mentorship. Financial support was received from GCF and their donors, including the Ivan Carter Wildlife Conservation Alliance and Oklahoma City Zoo. A special thanks goes to Etosha Heights Private Reserve, Natural Selection, the Namibia University of Science and Technology (NUST) and UNAM’s School of Veterinary Medicine for supporting this field course.

Two of the participants, Drs Hugo Paixao Perira and Hagnesio Chiponde from the Mozambique Wildlife Alliance, said about their impressions: “It is incredible how much you can learn in one week. We have worked with wildlife before, but this was an amazing opportunity to gain experience with animals we have not yet encountered in our professional practice. Working together with so many experts in their fields has been invaluable. Every participant and mentor brought something different to the course and having these open discussions has simply been fantastic.”

Capturing and moving sable antelope and waterbuck between camps on Etosha Heights Private Reserve, and fitting eland, African savannah elephant, gemsbok, Angolan giraffe, and Hartmann’s mountain zebra with tracking devices for remote monitoring were among the field course activities. Solar-powered Ceres Trace and Ceres Wild GPS satellite ear tags were fitted during this course – in most cases for the very first time on species in the wild. Weapon

handling and target practice with different dart projector models – both from the ground, from a vehicle, and from a helicopter –were another valuable aspect of the course.

It must be pointed out that all immobilisations in the field were undertaken as part of planned reserve management activities and landscape-level long-term conservation research programmes. The tracking devices that were fitted are part of a research project which explores the effect of different wildlife land use types – national park, private reserve, commercial game farms and communal conservancies – on biodiversity and ecological productivity in the Greater Etosha South-West Landscape (an area of almost two million hectares). Spearheaded by the NUST Biodiversity Research Centre and GCF, this study is a collaboration with many local and international partners and stakeholders.

CONSERVATION AND THE ENVIRONMENT IN NAMIBIA 2022 27

Group photo with all young African vets, their mentors and the MEFT game capture team.

When two carnivores meet it is often an aggressive encounter. Honey badgers are well known for ‘punching’ above their weight.

28

R. van Wyk

THE NEXT STEPS FOR CARNIVORE CONSERVATION IN NAMIBIA

By NCE, LCMAN and MEFT

Namibia is home to 34 terrestrial carnivore species – from Aardwolf to Zorilla (striped polecat), from the diminutive dwarf mongoose to the heavyweight lion, not to forget the world’s fastest land mammal (cheetah) and the renowned ‘tough guy’ of the African savannah (honey badger). Each species is unique and fascinating in its own right; all of them are worth conserving as part of Namibia’s natural heritage.

Producing the Carnivore Red Data Book

Conserving any species requires a detailed understanding of its current distribution and population trends, ecology and behaviour, alongside the known threats it faces. Drawing together all of this information in the Conservation Status and Red List of the Terrestrial Carnivores of Namibia (Carnivore Red Data Book for short) was no mean feat. From the initial idea during a workshop in 2017 until the final editorial touches and publishing earlier this year, the Carnivore Red Data Book involved 25 species assessors, 30 contributors and 31 reviewers.

As a joint publication between the Ministry of Environment, Forestry and Tourism (MEFT), the Large Carnivore Management Association of

Namibia (LCMAN) and the Namibian Chamber of Environment (NCE), this book is a testament to a successful collaborative process. Yet this is just the starting point for building a cohesive, joint action plan for carnivore conservation in Namibia. Having identified the threats and actions for each carnivore species, these and other stakeholders must work together as part of the newly established Carnivore Working Group to put these ideas into practise.

National Red Data Books follow a system created by the International Union of Conservation of Nature (IUCN) to determine the conservation status of each species. While the process is similar nationally and internationally, the global status of a species may be different to the national status, as it may be more or less threatened in one country than it is in the rest of the world.

The IUCN conservation status categories for all plant and animal species. Namibia’s carnivores fall between Least Concern and Critically Endangered.

CONSERVATION AND THE ENVIRONMENT IN NAMIBIA 2022 29

Namibian environmental conditions result in species that thrive in wetter environments (e.g. otters, serval) being naturally rare, while species that prefer drier environments (e.g. brown hyaena, black-footed cat) are favoured. For example, the black mongoose clearly favours the dry, rocky habitats in north-western Namibia and south-western Angola, as it occurs nowhere else on earth.

Species

Global Status Namibia Status Namibian range (km2)

% Global range

Population estimate Trend in Namibia

African wild dog EN CR 131,700 10.1 137-359 Stable Cheetah VU EN 439,400 14.1 1,500 Decreasing Black-footed cat VU VU 538,000 24.3 2,600 Decreasing

Leopard VU VU 776,800 9.1 <12,000 Variable Lion VU VU 94,300 5.7 800 Stable

Spotted hyaena LC VU 399,800 2.7 615-715 Stable Brown hyaena NT NT 685,600 28.0 <3,000 Stable Serval LC NT 291,000 2.3 1,500-4,000 Stable

African clawless otter NT NT ±34,000 <1 Unknown Decreasing Spotted-necked otter NT NT ±23,000 <1 Unknown Decreasing African striped weasel LC NT ±46,000 <1 Unknown Unknown

Eleven carnivore species in Namibia are considered Near Threatened or worse. Some species have naturally small ranges in the country due to environmental conditions (otters and weasels), while others are dependent on Namibia for large portions of their global range (brown hyaena, black-footed cat and cheetah). The population estimates and trends are based on the latest available data and expert assessments in the Carnivore Red Data Book.

Key threats to Namibian carnivores

In the Namibian assessment, all 34 species fell within the categories from Least Concern to Critically Endangered. Eleven species were classified as Near Threatened or worse, including five cat species, two hyaena species, the African wild dog, two otter species and the African striped weasel. All of these except the weasel face known threats to their survival. Reducing or eliminating these threats are the main focus of carnivore conservationists across Namibia.

Threats that affect more than one of the eleven carnivore species assessed as Near Threatened or worse in the Carnivore Red Data Book. Not all of these threats are equally severe for all species that are affected by them. Habitat loss in the graph includes habitat degradation and fragmentation, which are similar threats.

30

Whereas some individual species will require action plans tailored to the particular threats they face, multiple species would benefit from action plans that tackle the most common threats. Based on the Carnivore Red Data Book assessments, three threats affect eight species each: human-wildlife conflict, bycatch, and habitat loss, degradation or fragmentation.

While many carnivores are deliberately killed due to human-wildlife conflict (either in response to livestock losses or as a preventative measure), others are killed accidentally when other animals are being targeted – an issue known as bycatch. Carnivores that do not cause livestock losses at all can thus be killed as bycatch when snares, gin traps or poison are used to remove livestock-killing species. Poison is the worst of these methods, as it threatens vultures and birds of prey that are also threatened with extinction. Snares and gin traps are a close second, affecting many non-target animals. Reducing indiscriminate killing methods therefore requires special attention as part of broader plans to address humancarnivore conflict. This includes encouraging farmers to protect their livestock within healthy functioning ecosystems rather than fighting predators and in the process causing significant damage to their environment.

In the wetter areas of Namibia, habitat loss is caused mainly by land transformation to crop fields and through deforestation.

In drier areas, habitat is more likely to be degraded due to poor rangeland management (e.g. resulting in bush encroachment or other ecological changes) or fragmented by game-proof fencing that prevents some species from accessing the available habitat. When combined, these three habitat-related threats affect eight carnivore species.

Poaching or live capture for the illegal wildlife trade were described as threats to seven species, largely based on increased poaching in other countries that could become a problem in Namibia if left unheeded. The demand for lion bones and claws, leopard skins, and hyaena (both species) body parts in the Far East and within Africa (for status or traditional medicine purposes) drive poaching of these species. Capturing live cheetahs to be kept as pets within Namibia is problematic, although this is on a much smaller scale than the demand for pet cheetahs in the Middle East.

Seven carnivore species are reportedly killed in road accidents frequently enough for this to be considered a threat to their populations in some places. Since most carnivores are active during the night and at dawn or dusk, most of these accidents occur at these times. Tar roads that bisect national parks (e.g. Bwabwata) are a major source of road fatalities. Limiting the speed and restricting travel times to daylight hours would prevent many accidents and reduce the number of carnivores killed on the roads.

CONSERVATION AND THE ENVIRONMENT IN NAMIBIA 2022 31

The smallest cat species in Namibia, the black-footed cat, is a desert specialist and occurs in the southern parts of the country.

Brown hyaenas are mostly scavengers, while cheetahs rarely scavenge. This hyaena is helping itself to part of the cheetahs’ latest kill.

The African wild dog is Critically Endangered in Namibia and our most threatened carnivore species.

The honey badger is considered Least Concern in Namibia and globally.

A Sliwa

Derek Keats

Derek Keats

Gail Thomson

Trophy hunting was flagged as a threat to all three big cat species and the two hyaena species. The social structures and behavioural ecology of these species make their populations especially vulnerable to over-harvesting. Lions and leopards are infanticidal – i.e. when new males take over a territory they will kill any young cubs that are present at the time – which means that the removal of a dominant breeding male by any means could result in losing the cubs he sired. Both hyaena species have complex social structures that are disrupted by the removal of high-ranking females; females are easily mistaken for males during a hunt because they are slightly larger and their sex is difficult to determine (especially for spotted hyaena females, which have a pseudo-penis and pseudo-testes).

This threat is more complex than others, however, since the substantial money generated from trophy-hunting the big cats can offset livestock or game losses they cause, thus improving farmer tolerance and reducing human-carnivore conflict. Tolerance for leopards on freehold farms, where they occur widely, is linked to their value for trophy hunting. For all three big cat species, hunting quotas must be balanced to reduce negative impacts on cat populations and increase the benefits flowing to the most affected farmers.

The argument for hunting hyaenas is much weaker, as the trophy prices for both species are low. Brown hyaenas are primarily scavengers and rarely cause livestock losses, thus hunting them is unlikely to reduce human-carnivore conflict. Spotted hyaenas do cause livestock losses, but the low trophy fee is unlikely to increase farmer tolerance. Consequently, little is gained from hyaena trophy hunting in terms of increased tolerance, while the negative impacts of mistakenly hunting female hyaenas can be severe.

Negative perceptions of carnivores are an overarching threat that exacerbates other issues, especially human-carnivore conflict. Spotted hyaenas and African wild dogs are particularly disliked by farmers, while fishermen perceive the two otter species to be a threat to fish populations. A different kind of perception affects the black-footed cat, which although assessed as Vulnerable both nationally and internationally, receives no formal protection in Namibia because it is perceived to be secure. How we perceive carnivores thus affects the degree to which they are persecuted and our willingness to conserve them.

Climate change affected four species, especially the otter species and serval that rely on wetter habitats which are predicted to become drier over time. Disease was a particular concern for African wild dogs. They are highly susceptible to diseases borne by domestic dogs – e.g. rabies, canine distemper and parvovirus. Studies of black-footed cats show high mortality rates due to a combination of disease and predation by larger carnivores (e.g. black-backed jackal). The final risk that affected more than one species was prey decline, which is a problem in some areas. Lack of natural prey exacerbates human-carnivore conflict, as livestock are more frequently killed when prey populations are low.

32

Elzanne McCulloch

The lion is Africa’s largest carnivore and is listed as Vulnerable both globally and in Namibia.

Addressing the threats by taking action

In a similar way to the threats, some actions can benefit several species at once, provided they are centrally coordinated. To achieve this, one of the recommendations of the Carnivore Red Data Book is to establish a Carnivore Working Group chaired by MEFT that includes LCMAN members, farmers unions, conservancies, hunters’ associations and universities. Since many of the actions required – e.g. mitigating human-wildlife conflict, reducing bycatch and improving habitats – need to be implemented by multiple stakeholders, this working group can chart a collective way forward that takes different perspectives and interests into account. While the Carnivore Red Data Book provides a scientific perspective on each species, successful conservation requires scientific findings to be merged with socio-economic realities, which are best understood by non-academic stakeholder groups.

Within the working group, specialist task forces could be set up to focus on highly threatened species that face unique challenges (e.g. African wild dog), or multiple similar species (e.g. brown and spotted hyaenas), or to address some overarching common threats (e.g. negative perceptions). Besides the threatened species, many

Although it is common throughout Africa, the spotted hyaena is considered Vulnerable in Namibia, where the arid climate is better suited to brown hyaenas.