CONSERVATION AND THE ENVIRONMENT IN NAMIBIA

824,268 km²

21 March 1990 INDEPENDENCE:

CURRENT PRESIDENT: Nangolo Mbumba

Multiparty parliament

Democratic constitution Division of power between executive, legislature and judiciary

Secular state

Christian freedom of religion

SURFACE AREA: Windhoek CAPITAL: 90%

MAIN PRIVATE SECTORS: Mining, Manufacturing, Fishing and Agriculture 46% BIGGEST EMPLOYER: Agriculture

FASTEST-GROWING SECTOR: Information Communication Industry

Diamonds, uranium, copper, lead, zinc, magnesium, cadmium, arsenic, pyrites, silver, gold, lithium minerals, dimension stones (granite, marble, blue sodalite) and many semiprecious stones

CURRENCY:

The

is

and on par

Foreign currency, international Visa, MasterCard, American Express and Diners Club credit cards are accepted.

TAX AND CUSTOMS

ROADS:

NATURE RESERVES: of surface area

HIGHEST MOUNTAIN: Brandberg

OTHER PROMINENT MOUNTAINS: vegetation zones

Spitzkoppe, Moltkeblick, Gamsberg

PERENNIAL RIVERS: Orange, Kunene, Okavango, Zambezi and Kwando/Linyanti/Chobe

EPHEMERAL RIVERS: Numerous, including Fish, Kuiseb, Swakop and Ugab

20% 14 400 680

species of trees

ENDEMIC plant species 120+

species of lichen

LIVING FOSSIL PLANT: Welwitschia mirabilis

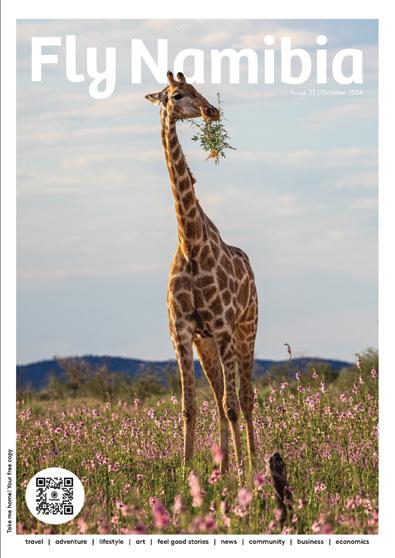

BIG GAME: Elephant, lion, rhino, buffalo, cheetah, leopard, giraffe

20 antelope species

250 mammal species (14 endemic)

256 699

50 reptile species

ENDEMIC BIRDS including Herero Chat, Rockrunner, Damara Tern, Monteiro’s Hornbill and Dune Lark frog species 15%

All goods and services are priced to include value-added tax of 15%. Visitors may reclaim VAT.

ENQUIRIES: Namibia Revenue Agency (NamRA) Tel (+264) 61 209 2259 in Windhoek

Public transport is NOT available to all tourist destinations in Namibia.

There are bus services from Windhoek to Swakopmund as well as Cape Town/Johannesburg/Vic Falls.

Namibia’s main railway line runs from the South African border, connecting Windhoek to Swakopmund in the west and Tsumeb in the north.

There is an extensive network of international and regional flights from Windhoek and domestic charters to all destinations.

HARBOURS: Walvis Bay, Lüderitz

MAIN AIRPORTS: Hosea Kutako International Airport, Eros Airport RAIL NETWORK:

6.2 telephone lines per 100 inhabitants

MOBILE COMMUNICATION SYSTEM:

Direct-dialling facilities to 221 countries

0.4182 medical doctor per 1,000 people privately run hospitals in Windhoek with intensive-care units

4

Medical practitioners (world standard) 24-hour medical emergency services

3.1 million DENSITY: 3.8 per km²

461 000 inhabitants in Windhoek (15% of total)

EDUCATIONAL INSTITUTIONS: over 1,900 schools, various vocational and tertiary institutions bird species

Most tap water is purified and safe to drink. Visitors should exercise caution in rural areas. GMT + 2 hours

220 volts AC, 50hz, with outlets for round three-pin type plugs

FOREIGN

More than 50 countries have Namibian consular or embassy representation in Windhoek.

PUBLISHING EDITORS

Elzanne McCulloch elzanne@venture.com.na

Gail Thomson gailsfelines@gmail.com

PRODUCTION & LAYOUT

Liza Lottering liza@venture.com.na

CUSTOMER SERVICE

Bonn Nortjé bonn@venture.com.na

PRINTERS

John Meinert Printing, Windhoek

The editorial content of Conservation and the Environment in Namibia is contributed by the Namibia Chamber of Environment, freelance journalists, employees of the Namibian Ministry of Environment, Forestry and Tourism (MEFT) and NGOs. It does not necessarily reflect the opinions or policies held by MEFT or the publisher. No part of the magazine may be reproduced without written permission from the publisher.

That’s our mantra at Venture Media. Sharing stories, information and inspiration to an audience that understand and value why certain things matter. Why conservation, tourism, people & communities, businesses and ethics matter.

How these elements interrelate and how we can bring about change, contribute to the world and support each other. Whether for an entire nation, an industry, a community, or even just an individual.

We find, explore, discover, teach, showcase and share stories that matter.

www.venture.com.na or email us at info@venture.com.na for a curated proposal.

In 2021, we're focussing on telling and sharing STORIES THAT MATTER acros riou tal p urney and share your s wi ders ertain things matter

tion communities matter

w t elat ng about change, ute ppor er for an entire nation mun dividual

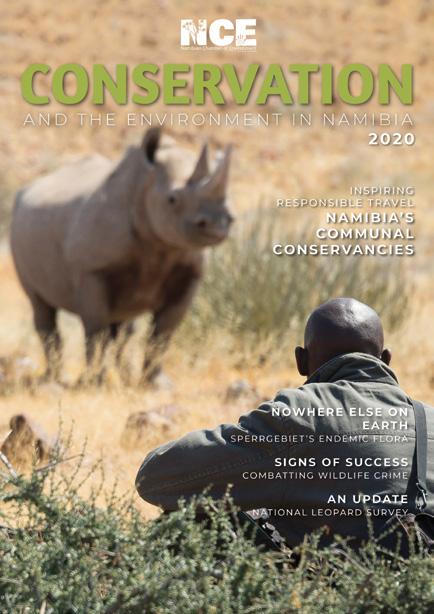

As we usher in another edition of Conservation and the Environment in Namibia, I am once again reminded of the unwavering dedication that permeates our nation’s conservation efforts. This magazine, with its array of stories, not only showcases our achievements but also highlights the challenges we face in safeguarding our natural heritage. Namibia, a country blessed with a rich and diverse ecosystem, continues to set an example of how conservation can be intertwined with sustainable development.

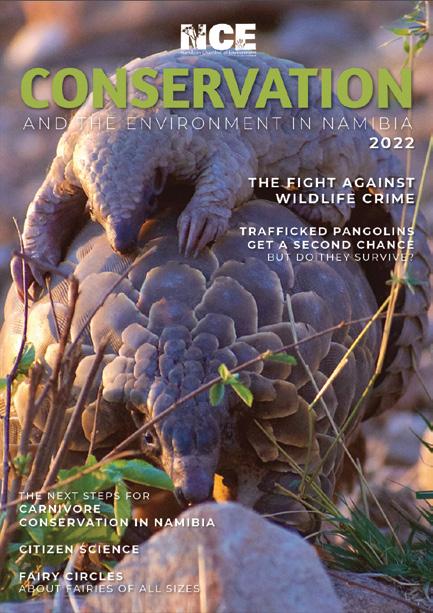

In this issue, we explore and celebrate innovation, such as the Nyae Nyae Pangolin Project, which is working tirelessly to protect one of the most trafficked species in the world. The importance of such initiatives cannot be overstated, as they provide a blueprint for tackling the global wildlife trafficking crisis. From community rangers to advanced tracking technologies, Namibia is at the forefront of conservation strategies that prioritise both people and wildlife.

Additionally, the feature on the Greater Etosha Carnivore Programme emphasises our commitment to preserving the delicate balance of predator and prey in one of Africa’s most iconic landscapes. These efforts are not without their hurdles, as climate change, humanwildlife conflict, and habitat encroachment continue to pose significant threats. Yet, despite these challenges, Namibia’s conservationists remain resilient, driven by the knowledge that the success of these programs extends far beyond our borders.

Each time I read a story about Namibia’s bush encroachment management programmes, I am left in awe of the creative ways we can turn problems into opportunities. The article in this issue offers another innovative approach and exemplifies how we can harness the power of nature to restore our landscapes and boost our economy through sustainable practices.

As we reflect on these stories, it becomes clear that conservation is not just about protecting species – it’s about creating a future where people and nature thrive together. Namibia’s conservation model, rooted in community-based natural resource management and sustainable use, is a testament to the power of collaboration. It’s a model that reminds us that the greatest solutions often come from within, fueled by the passion and commitment of our people.

To our readers and contributors, thank you for your continued support in amplifying these stories that matter. Together, we are ensuring that Namibia’s conservation legacy continues to shine brightly.

Yours in conservation,

Elzanne McCulloch

The Namibian Chamber of Environment (NCE) is a membership-based and -driven umbrella organisation established as a voluntary association under Namibian Common Law to support and promote the interests of the environmental NGO sector and its work. The Members constitute the Council – the highest decision-making organ of the NCE. The Council elects Members to the Executive Committee at an AGM to oversee and give strategic direction to the work of the NCE Secretariat. The Secretariat (staff) of the NCE comprise a CEO and Office Manager. Only the Office Manager is employed full-time. The NCE currently has 65 Full Members – Namibian registered NGOs whose main business, or a significant portion of whose business, comprises involvement in and promotion of environmental matters in Namibia; and 13 Associate Members – individuals running environmental programmes and non-Namibian NGOs likewise involved in local to national environmental matters in Namibia. A list of Members follows. For more information on each Member, their contact details and website link, please go to the NCE website at www.n-c-e.org/members.

THE NCE HAS FOUR ASPIRATIONAL OBJECTIVES AND FIVE OPERATIONAL OBJECTIVES AS FOLLOWS:

Aspirational Objectives

• Conserve the natural environment

• Protect indigenous biodiversity and endangered species

• Promote best environmental practices

• Support efforts to prevent and reduce environmental degradation and pollution

Operational Objectives

• Represent the environmental interests of Members

• Act as a consultative forum for Members

• Engage with policy- and lawmakers to improve environmental policy and its implementation

• Build environmental skills in young Namibians

• Support and advise Members on environmental matters and facilitate access to environmental information

The NCE espouses the following key values:

• To uphold the fundamental rights and freedoms entrenched in Namibia’s Constitution and laws, including the principles of sustainable use, protection of biodiversity and inter-generational equity;

• To promote compliance with, uphold and share environmental best practice, recognising that the Earth’s resources are finite, and that human health and wellbeing are inextricably linked to environmental health;

• To recognise that environmental best practice is best promoted by implementing the following seven principles: sustainability, polluter pays, precautionary, equity, effectiveness and efficiency, human rights and participation;

• To develop skills, expertise and passion in young Namibians on environmental issues;

• To ensure political and ideological neutrality, be evidence-based and counter fake information; and

• To promote inclusiveness and to fiercely and fearlessly reject any form of discrimination.

TO EFFECTIVELY IMPLEMENT THESE OBJECTIVES AND VALUES, THE NCE HAS DEVELOPED EIGHT STRATEGIC PROGRAMME AREAS:

1. Support to Members

The NCE provides office facilities, boardroom, internet and safe parking for its out-of-town Members when in Windhoek; in partnership with Westair, a Cessna 182 for conservation purposes such as aerial surveys, radio-tracking and anti-poaching work; three 4x4 Toyota Hilux double-cab vehicles for use by Members for their conservation work; registration and research permit facilitation; and any other support requested by Members.

2. National facilitation

The NCE organises symposia and workshops on topical and priority issues; supports the development of strategic Best Practice Guides at sector level, the first on mining, the second (in preparation) on hunting; reviews policy and legislation on and/or impacting Namibia’s environment; facilitates collaboration on conservation assessments and action plans, the latest being Namibia’s Carnivore Red Data Book (http:// the-eis.com/elibrary/search/27193); and representing the sector and Members on national bodies.

3. Environmental information

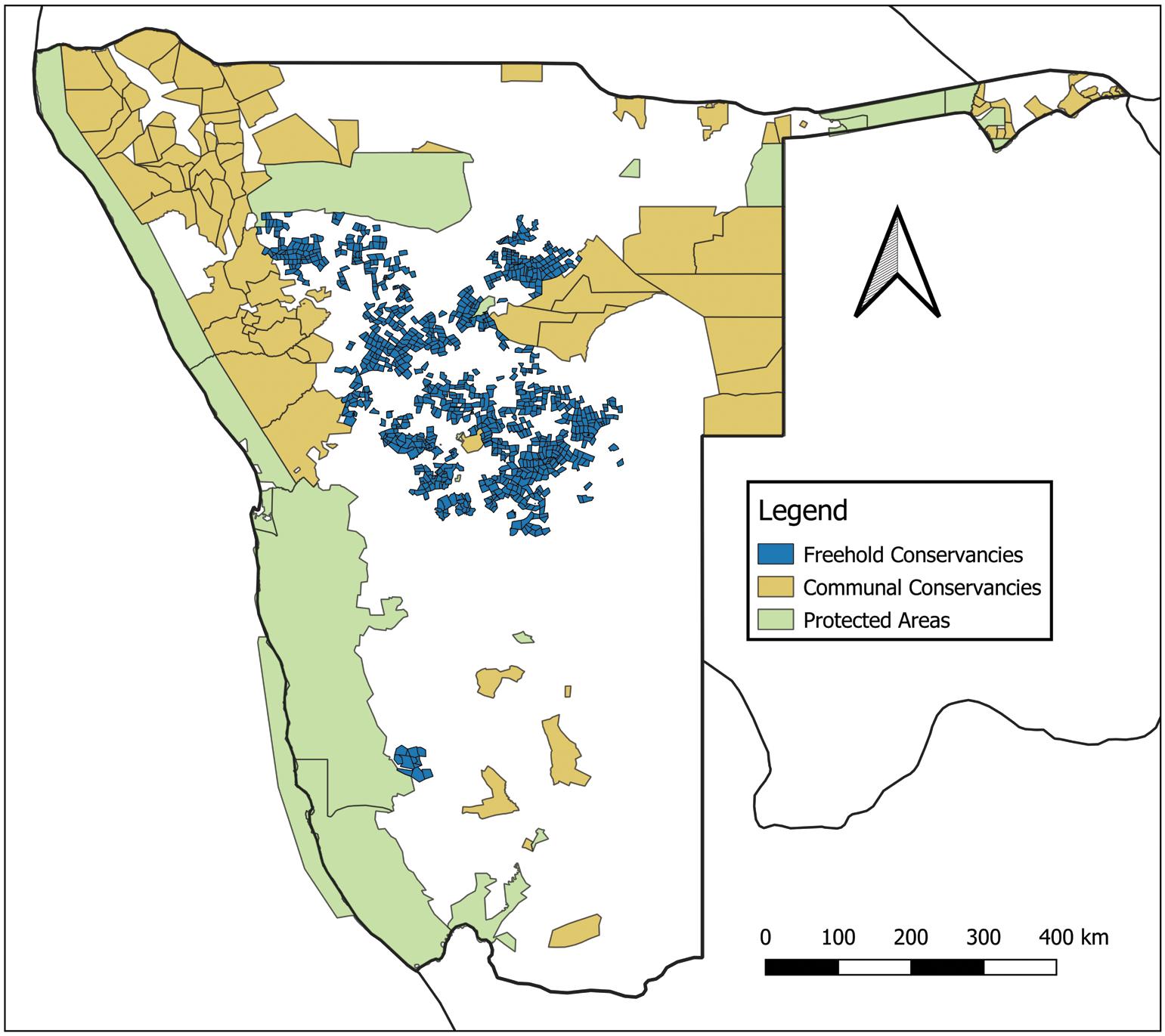

The NCE hosts and supports the development of Namibia’s Environmental Information Service (EIS at www.the-eis.com) in partnership with Paratus Telecom, a one-stop-shop for all environmental information on Namibia. The EIS comprises an e-library with over 28,000 reports, publications, maps, data sets, theses, etc., which are searchable and down-loadable. Included are all Environmental Impact Assessment

(EIA) reports since 2020 (over 4,500), almost 800 wildlife survey reports and counts some going back to 1926, and wildlife crime reports (over 4,500). It provides an Atlasing platform for citizen science data collection that currently covers mammals, reptiles, amphibians, butterflies, plants (both indigenous and invasive alien) and archaeology, and records are conveniently entered via a free cell phone App.

The NCE has also established a free, open access scientific e-journal – Namibian Journal of Environment – now in its seventh year (www. nje.org.na). The NCE and Venture Media’s environmental website “Conservation Namibia” (www.conservationnamibia.com) tells Namibia’s conservation stories via blogs, factsheets, video and articles from this magazine. The NCE informs the public on topical environmental issues on its website (www.n-c-e.org), Facebook page, X (Twitter) feed and LinkedIN profile. The Namibian Environment and Wildlife Society (NEWS) with support from the NCE recently launched a new tool to help stakeholders and the public better engage with EIAs – the EIA Tracker (https://eia-tracker.org.na/), a transparent, user-friendly system that presents and maintains information on all development projects that require EIAs, with a current database of 1,437 proposed and existing projects.

4. Environmental advocacy

The NCE addresses national threats to Namibia’s environment and natural resources by first attempting to work constructively with the relevant government or other entity but, if necessary, through public exposure. The NCE has addressed the issue of Chinese incentivised poaching and illegal trade in specially protected wildlife, the overfishing of pilchards in Namibian waters, illegal and unsustainable timber harvesting and export, and the need to reduce and eliminate single-use plastic from Namibia’s environment. It recently published a position paper on the proposed hydrogen developments for the Tsau ||Khaeb (Sperrgebiet) National Park, explaining that this product is correctly termed red hydrogen due to the major potential impacts on biodiversity (https://n-c-e.org/wp-content/uploads/Green-hydrogen-Tsau-KhaebNational-Park-NCE-Position-Paper.pdf).

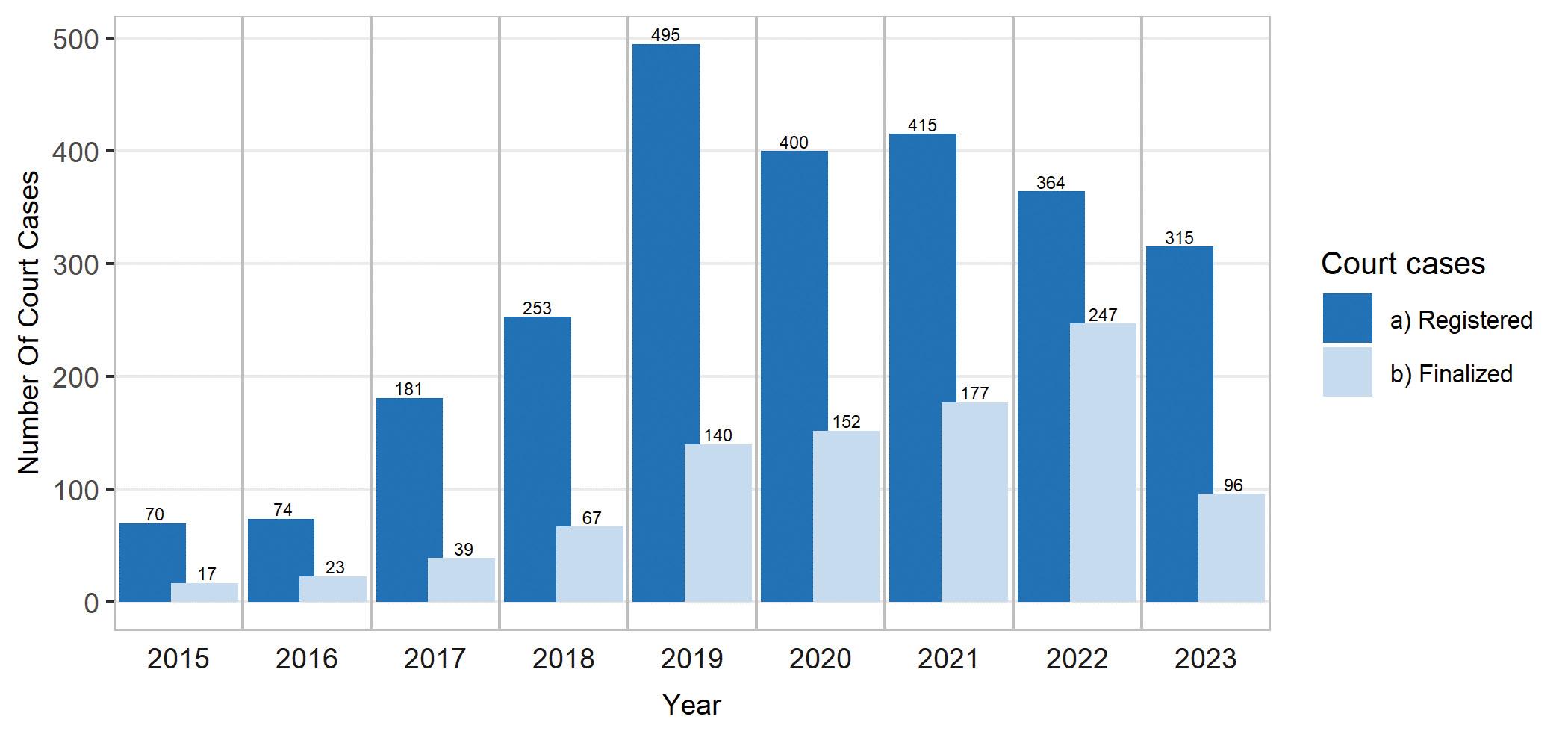

It has also initiated a highly successful pangolin reward scheme in partnership with MEFT, some NCE Members and communities. The scheme rewards people for providing information on pangolin trafficking leading to arrests – more than 300 criminal cases opened and over 500 people arrested and charged.

5. Environmental policy research

When we talk about the “environment” we mean the interrelationship of ecological, social and economic aspects – essentially sustainable development. This is appropriate for a country with an economy reliant mainly on natural resource-based primary production where ecological and socio-economic issues are two sides of the same coin. However, this conceptual approach is rarely understood by people from western industrialised countries who think of environment as being just the green environment. To get around this problem, the NCE has established a socio-economic / livelihoods component that works seamlessly with the environmental component and focusses mainly on the urban environment. Over 50% of Namibians now live in towns and the city of Windhoek, with a projected rise to 70% by 2030. The priority areas of focus are access to affordable urban land for housing, appropriate sanitation, solid waste management, energy and research on the economics of poverty.

6. Young Namibian training and mentorship

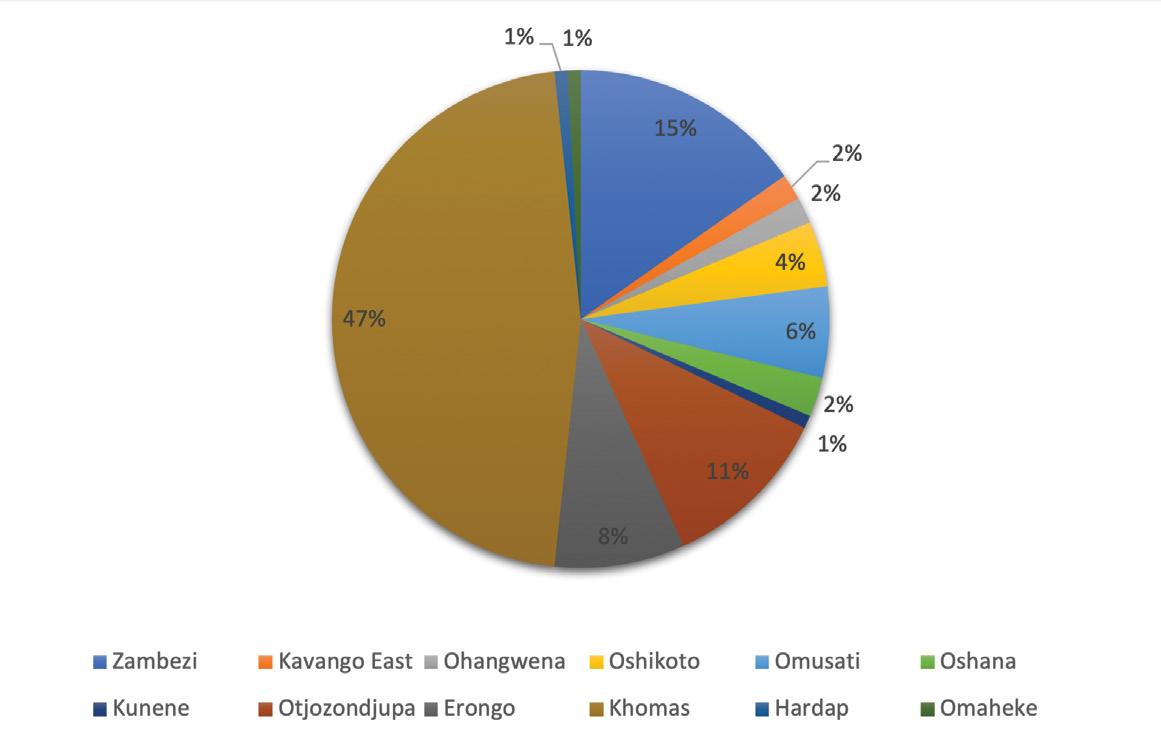

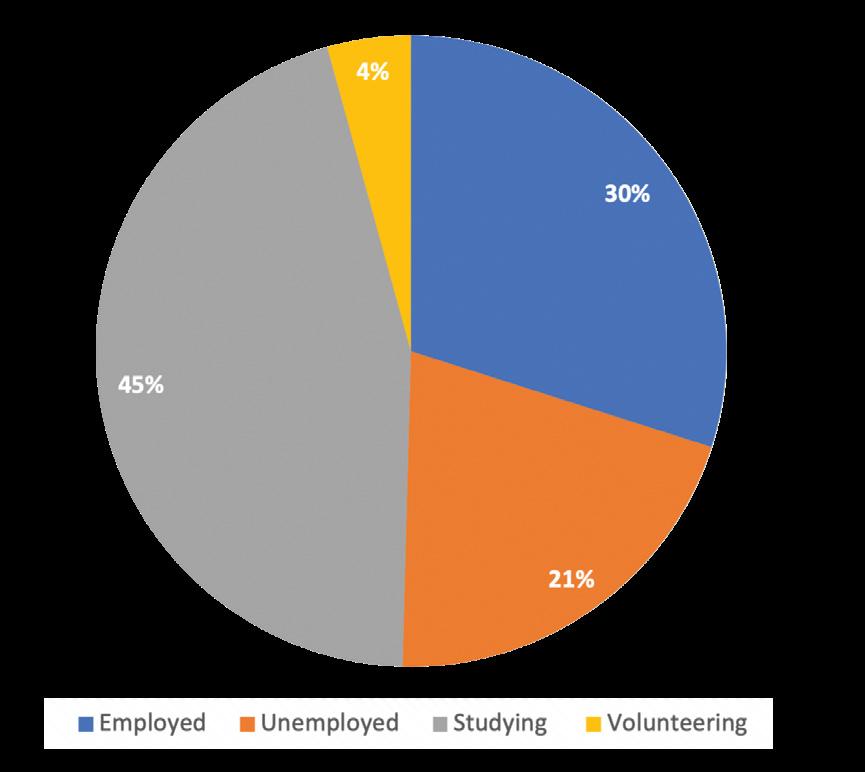

Over the past seven academic years (2018-2024) the NCE in partnership with Woodtiger Fund has provided 226 post-graduate bursaries in the broad environmental field (including subjects such as biodiversity conservation, natural resources management, wildlife and tourism management, sustainable agriculture, water, forestry and fisheries

management, climate change mitigation and adaptation, renewable energy, data and spatial science, risk and change management, leadership, through to environmental economics, environmental law, environmental engineering) and 52 internships, mainly for NCE bursaryholders, that involves close mentoring by experienced environmental professionals. The aim is to build the capacity and confidence of young Namibians to become the environmental leaders of tomorrow. In 2024, NCE supported the establishment of the Namibian Youth Chamber of Environment, which seeks to inspire and equip young (18-35 years) Namibians with the confidence and skills to advocate for the environment during their studies, within their communities and in their professional settings. Current membership stands at 112 individuals and two youth organisations.

7. Fund raising

Core funding for the NCE is currently provided by B2Gold. This means that all additional funding received is invested directly into

A. Speiser Environmental Consultants cc African Conservation Services cc Africat Foundation

Ashby Associates cc

Biodiversity Research Centre, NUST (BRC-NUST)

Botanical Society of Namibia

Brown Hyena Research Project Trust Fund

Bwabwata Living Museum

Cheetah Conservation Fund (CCF)

Canyon Nature Trust

Conservancy Association of Namibia (CANAM)

Desert Lion Conservation Trust

Development Workshop Namibia (DW-N)

Earthlife Namibia

Eco Awards Namibia

Eco-logic Environmental Management Consultancy cc EduVentures

Elephant Human Relations Aid (EHRA)

Environmental Assessment Professionals Association of Namibia (EAPAN)

Environmental Compliance Consulting (ECC) EnviroScience

Felines Communication and Conservation Consultants cc Giraffe Conservation Foundation (GCF)

Gobabeb Research and Training Centre

Greenspace

Integrated Rural Development and Nature Conservation (IRDNC)

JARO Consultancy

Kwando Carnivore Project

LM Environmental Consultants

Museums Association of Namibia

N/a’an ku sê Foundation

Namib Desert Environmental Education Trust (NaDEET)

Namibia Biomass Industry Group (N-BiG)

Namibia Bird Club

Namibian Beekeeping Association

Namibia Nature Foundation (NNF)

Namibia Professional Hunting Association (NAPHA)

Namibia Scientific Society

Namibia Archaeological Trust

Namibian Association of CBNRM Support Organisations (NACSO)

environmental projects and programmes – there are no overhead costs. The NCE focuses on corporate support and avoids targeting funding sources that may compete with its Members. The corporate sector assists with fund raising by approaching their clients, partners and networks. Our main sponsors are shown on the back cover.

8. Grants making

Funds raised by the NCE are used strategically to support priority environmental projects and programmes in Namibia. Emphasis is placed on legacy initiatives that have tangible outcomes. These are often based on national policy and bring together government and NGO partners, communities and the private sector, and frequently lead to investments by larger bilateral or multi-lateral funding organisations. An on-line grant application process allows NCE Members to apply for funding. To date 212 grants have been awarded, to the value of just under N$ 30 million, with 90% going to NCE Members. Some of these projects are showcased in this magazine.

Namibian Environment and Wildlife Society (NEWS)

Namibian Hydrogeological Association

NamibRand Nature Reserve

Nyae Nyae Development Foundation of Namibia (NNDFN)

Ocean Conservation Namibia

Omba Arts Trust

Ongava Game Reserve / Research Centre

Orange River-Karoo Conservation Area (ORKCA)

Otjikoto Trust

Pangolin Conservation and Research Foundation

ProNamib Nature Reserve

Progress Namibia TAS cc

Rare and Endangered Species Trust (REST)

Research and Information Services of Namibia (RAISON)

Rooikat Trust

Save The Rhino Trust (SRT)

Scientific Society Swakopmund

Seeis Conservancy

SLR Environmental Consulting

Southern African Institute of Environmental Assessment (SAIEA)

SunCycles Namibia

Sustainable Solutions Trust

Tourism Supporting Conservation Trust (TOSCO)

Twin Hills Trust

Venture Media

ASSOCIATE MEMBERS

Bell, Maria A

Black-footed Cat Research Project Namibia

Bockmühl, Frank

Desert Elephant Conservation

Irish, Dr John

Kolberg, Herta

Leibniz Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research

Lukubwe, Dr Michael S

Namibia Animal Rehabilitation, Research and Education Centre (NARREC)

Seabirds and Marine Ecosystems Programme

Sea Search Research and Conservation (Namibia Dolphin Project)

Strohbach, Dr Ben

Wild Bird Rescue

As we write this, some 23,000 people from nearly every country on earth are meeting in Cali, Columbia to discuss the conservation of biological diversity. Biodiversity, as it is better known, encompasses all life forms on this planet we call home and which we have a responsibility to conserve. It is therefore particularly fitting to introduce the most biodiverse edition of Conservation and the Environment in Namibia that we have produced to date.

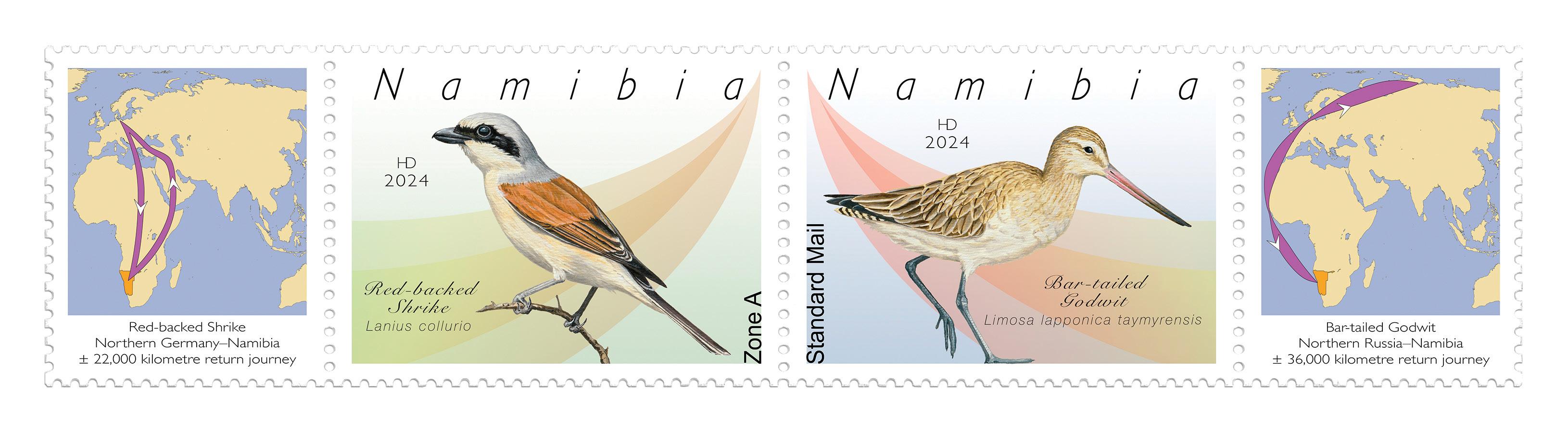

Of all the plants and animals found naturally in Namibia (known as indigenous) the ones that are found only here and nowhere else – endemic species – represent the country’s special contribution to global biodiversity. Turn to p.26 and p.32 to find a tantalising sample of these species and the ‘near-endemics’, which Namibia shares with South Africa or Angola.

Worryingly, some of Namibia’s most interesting endemic and near-endemic plants are threatened by plant poachers (p.38) that mainly collect these species to sell to people who want them in their gardens, perhaps without realising that their hobby threatens these plants in the wild. On p.58, Helge Denker zooms out to consider Namibia’s fight against wildlife crime more broadly, which remains a critical national challenge.

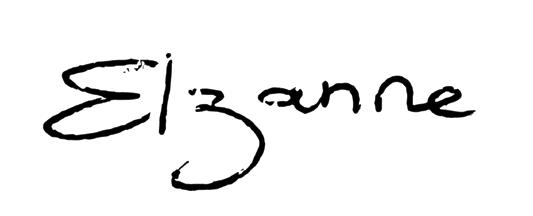

Another national challenge for biodiversity is the prevalence of fencing that criss-crosses freehold land. While Peter Cunningham looks at the impacts that relatively low livestock fences have on springbok (p.54), fencing that is high enough to keep jumping antelope from crossing is an even greater threat – especially if electrified. The ability of wildlife to move in response to changing climatic conditions in arid and semi-arid ecosystems is their most important behavioural survival mechanism. The freehold conservancy concept, which was initially supported by government, provides a potential solution to this problem by encouraging landowners to drop some of their game-proof fences (see p.18).

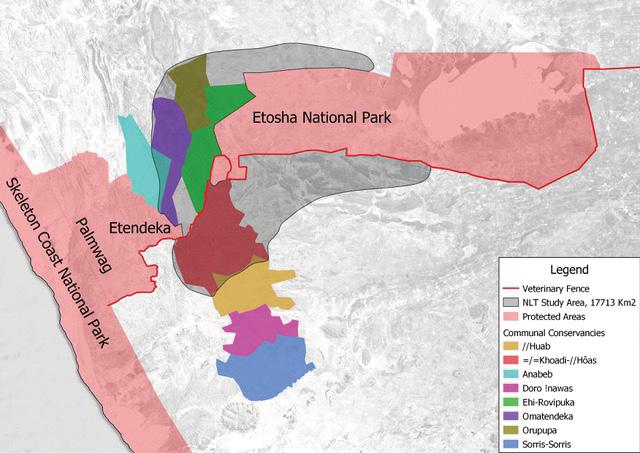

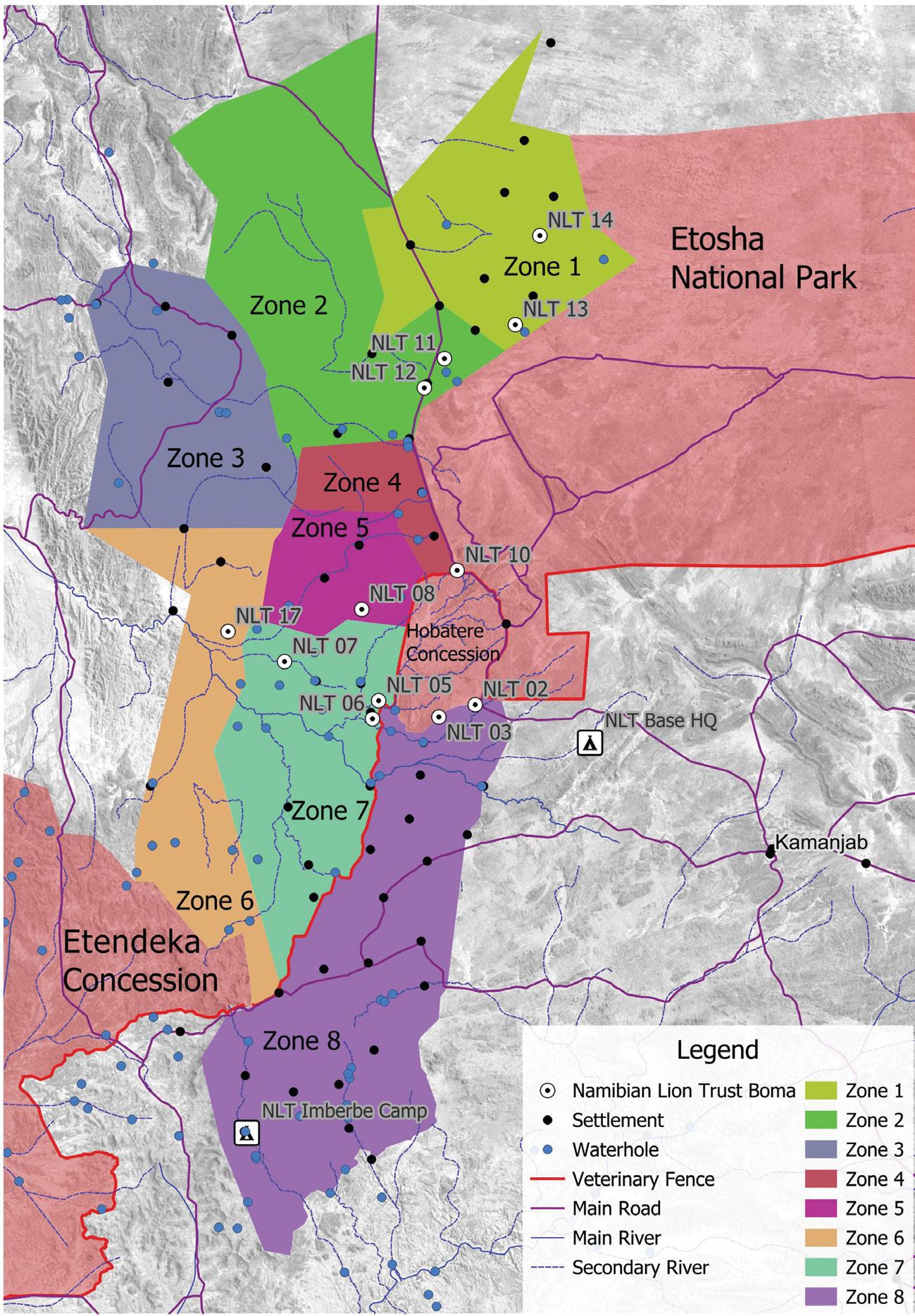

Namibia’s communal conservancies continue to enjoy national and international support for their role in supporting sustainable rural livelihoods by managing their biodiversity. Find out more about a new four-year project to support multiple conservancies that create a ‘bridge’ between Etosha and Skeleton Coast National Parks on p.12. Conservancies in this hyper-arid north-western part of the country also play a key role in connecting lion populations across this landscape (see p.44). Meanwhile, 12 conservancies and a community association on the north-eastern side of the country have benefitted from the multi-pronged, collaborative Sustainable Wildlife Management Programme (p.68).

The state of our biodiversity is not only the concern of a few trained conservation scientists – every Namibian citizen should be concerned about how the environment is managed and be acquainted with related government policies and processes. Most appropriately for an election year, you will discover that democracy and the environment can indeed go hand-in-hand on p.64. The system for Environmental Impact Assessments is supposed to allow the public to exercise their democratic rights to comment on new development projects, but as you will find on p.22, this system is broken.

The connection between human well-being and biodiversity conservation is most clearly evident in the matter of health. The rabies virus is deadly to humans and animals, posing a particular threat to domestic and wild cats and dogs. Rabies vaccination programmes, such as that described on p.50, are critical for tackling this disease and protecting humans and animals.

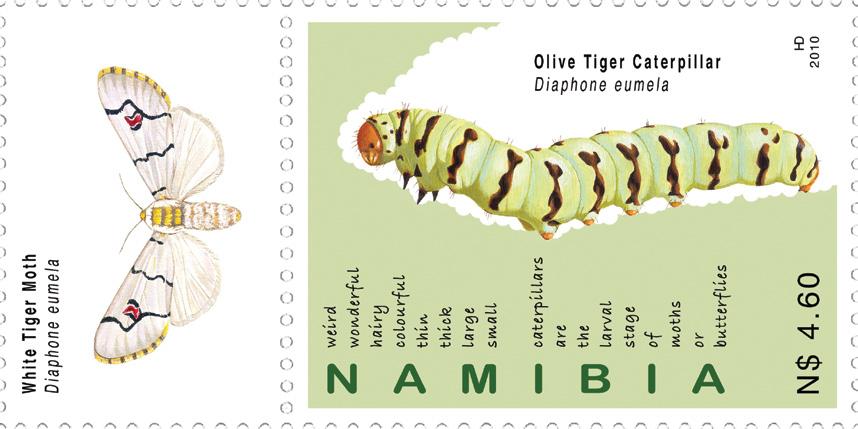

Finally, we invite you to reflect on the passage of time with the beautiful stamps on pp.74-75 that depict Namibia’s natural beauty. With the rise of email and instant messaging, using and collecting stamps is becoming a thing of the past. Before you get too melancholic, turn to the final page of this year’s edition to read about the future. We are excited to support the Namibian Youth Chamber of Environment, a dynamic group of students, young professionals and job seekers who are eager to take up the baton of biodiversity conservation to secure their future.

Yours in Conservation,

Chris Brown and Gail Thomson

By

The 55,299 square kilometres of land between the Etosha and Skeleton Coast national parks are renowned for unique biodiversity and an exceptionally high species variety. This part of the country is highly vulnerable to climate change, however. It is also home to people who have lived alongside wildlife for untold centuries. They were among the pioneers in community conservation and established some of the first communal conservancies in Namibia.

Fourteen of these communal conservancies form a ‘bridge’ between the two national parks by creating space for wildlife and thus generating socioeconomic benefits for the people living on this land. The newer concept of People’s Parks allows conservancies to create formal protected areas on their lands by joining areas that are zoned for wildlife while retaining their rights to that land and the benefits it generates. Although these conservancies are well-established (some are nearly 30 years old), they continue to face challenges that require external support and partnerships to overcome.

The Legacy Landscapes Fund (LLF), which aims to provide long-term support for nature, climate and people, has come at an ideal time for the conservancies. This global fund was established in response to a critical realisation among policymakers: traditional short-term project approaches of 3-5 years have proven inadequate in addressing the urgent needs of global conservation. Recognising that the challenge of biodiversity loss is too vast and complex for any single sector to tackle alone, LLF was created to forge a powerful partnership between public and private sector actors with a unified and sustainable framework for long-term conservation efforts.

LLF was established in late 2020 by the German Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development as an independent charitable foundation under German law, designed to guarantee long-term conservation funding for nature, climate and people. Four years later, LLF provides long-term funding for the protection of areas in 15 countries across 4 continents, covering more than 473,000 square kilometres. This includes the Skeleton Coast Etosha Conservation Bridge in Namibia.

John Kasaona, CEO of Integrated Rural Development and Nature Conservation (IRDNC), an LLF implementing partner, says, “The Legacy Landscapes Fund provides vital support to elevate the existing conservation efforts to new heights. The long-term goal is to enhance conservation efforts and support the upliftment of rural communities. The changing climate requires rural residents to participate in climate-resilient activities. Additionally, landscape-level connectivity will be crucial for the future, as individual conservancy areas may not have a significant impact on species abundance. This presents a new opportunity for nature-based development, which will ultimately benefit the local people.”

Dr Juliane Zeidler, Country Director of World Wildlife Fund (WWF) Namibia, adds, “Respect for indigenous people and local communities is at the core of WWF’s inclusive conservation approach and it is embedded in the fabric of LLF. Environmental and social safeguards are applied throughout consultation, development and implementation processes, and there is a secure mechanism for sharing grievances with the confidence that they will be handled with honesty and respect.” Namibia’s WWF office is the first in the WWF network to become a partner in LLF.

The vision for the Skeleton Coast Etosha Conservation Bridge is ambitious: To ensure a connected, resilient, economically viable conservation landscape for people and nature that restores and maintains landscape connectivity and generates conservation and improved socio-economic development.

This statement reflects the will of the local people. "For me, I was born here, grew up here, I know the living standard of the people. LLF inspires me because I know it will bring changes to the people of these conservancies. The child of my child’s child will be better off

than we used to be,” says Siegfried Muzuma, the Chairperson of the Ehrivopuka Conservancy.

A great deal of demanding work will be needed to bring this wish for the future to fruition. Partners in government, WWF Namibia and IRDNC, other national non-government organisations (NGOs) and rural communities are working together to achieve results in three defined thematic areas: good governance and management, improved livelihoods, resilience, health and education, and to secure healthy habitats and connectivity.

At a recent meeting with the LLF technical team, Bennett Kahuure, Director of Parks for the Ministry of Environment, Forestry and Tourism (MEFT), emphasised, “Livelihoods are especially important to us, as are human rights. The government supports the LLF, which will help us continue to upscale and improve the delivery of our work.”

Conservation challenges in this landscape include climate change and aridification, alien invasive plants, pressure on small populations of rare species from wildlife crime, human-wildlife conflict, abandoned small mines and the risk of encroachment from unsustainable development including mining and tourism operations. There has also been a sharp decline in wildlife numbers, due at least in part to the prolonged drought.

WWF and IRDNC are approaching these challenges methodically with projects designed for long-term impact. Pauline Lindeque, Wildlife and Landscapes Programme Director for WWF Namibia, explains, “The LLF grant provides one million USD per year. The plan which WWF developed with IRDNC and MEFT is designed to focus on specific activities in targeted areas, to achieve the set objectives in those areas and then allocate resources to address new challenges

or pursue additional opportunities, ultimately promoting progressive self-sufficiency”.

For example, remnants of old mining operations will be cleared from Skeleton Coast National Park and discrete barriers will be established to protect lichen fields in Dorob National Park. Another example is providing support for the emerging Ombonde and Hoanib People’s Parks, making it possible for the communities to charge entry fees, hire game guards and build tourism infrastructure that will increase their long-term income.

One of the programme’s research priorities is to understand the dynamics of wildlife populations in hyper-arid north-western Namibia for improved post-drought recovery, while maximising livelihood benefits. A collaborative project involving WWF, the Namibia University of Science and Technology (NUST), MEFT and St. Andrews University – supported by the UK government’s programme Reversing Environmental Degradation in Africa and Asia (REDAA) – is designed to answer questions relating to the current drought and low wildlife numbers.

During the early years of community conservation in this region, wildlife populations recovered dramatically, allowing communities to begin building a thriving wildlife-based economy. However, prolonged drought has caused wildlife (and livestock) numbers to crash over the last decade. People have lost their food supply, and while the embryonic tourism side of the wildlife economy survived despite the devastating impact of COVID-19, it has been seriously weakened. For full socioeconomic recovery, wildlife populations need to recover.

Over the next four years, researchers and stakeholders will work together to:

• Collate data collected by communities and researchers to identify wildlife corridors and dispersal zones and identify obstacles to those.

• Develop a strategy for the restoration of habitats and wildlife within the landscape (including possible reintroduction of key

species once land-use and governance structures are in place and the drought has broken).

• Explore Payment for Ecosystem Services (PES) models (wildlife, biodiversity and carbon credits) as mechanisms to secure the protection of key habitats.

• Identify and facilitate joint venture biodiversity economy partnerships for socio-economic development.

By understanding the social, environmental and spatial dynamics that have led to wildlife and habitat decline, actions can be taken to reverse the trends and enhance climate resilience, thus improving livelihoods and conservation outcomes.

“In my opinion, LLF's support arrived at a critical moment when the future of Community-Based Natural Resource Management (CBNRM) was uncertain. We are grateful for LLF's generous commitment, and we are confident that it will help us change the conservation landscape going forward, ultimately improving the lives of the local community members”, John Kasaona says.

It will take time to achieve these goals, which is why the longterm focus of the Legacy Landscapes Fund is so well suited to the conservation and economic needs of this landscape. Funding for the Skeleton Coast Etosha Conservation Bridge will be in place for 50 or more years, allowing us to plan with care, act with a common purpose and achieve a better future for all.

Acknowledgment: We are grateful to the Rob Walton Foundation for providing the matching funding to LLF, to make this conservation effort possible.

A neglected part of Namibia’s conservation story

By CANAM executive committee with Jan Hennings, Jürgen Rumpf, Thomas Peltzer, Gudrun Heger and Tim Hofmann

Namibia’s freehold farmlands host 80% of the country’s wildlife. This is the result of forwardthinking policies implemented during the 1960s and 70s that allowed for private ownership over wild animals. Freehold farmers would nonetheless be able to contribute much more to national conservation efforts and global targets if their conservancies were fully supported and incentivised by the government.

While many people are aware of the history and role of communal conservancies in Namibia, fewer know about the conservancy movement on freehold farms that started with the establishment of Ngarangombe Conservancy in 1991. Prior to this, freehold farmers started conserving wildlife on their farms in response to the Nature Conservation Ordinances of 1967 and 1975 that granted landowners the right to own and use the wildlife on their land for economic purposes.

As game numbers increased because game was now valued for trophy hunting, live sales, meat and photographic tourism, increasing numbers of landowners constructed game-proof fences to keep wildlife on their land. This cut off the migration routes of large herds of plains game, which then required more intensive game ranching to maintain their population sizes in an ecologically sustainable manner.

Understanding the long-term ecological issues that the fragmentation of land would have for wildlife, some freehold farmers considered joining their farms together and managing their wildlife cooperatively. This notion was strongly supported by farsighted government officials in the early 1990s, who visited farmers associations throughout the country and enabled the establishment of the first conservancies.

Five years before legislation was passed to allow conservancies on communal lands, these first freehold conservancies were trailblazers. They defined a conservancy as “A legally protected area of a group of bona fide land-occupiers practising co-operative management based on a sustainable utilisation strategy, promoting conservation of natural resources and wildlife while striving to

reinstate the original biodiversity with the basic goal of sharing resources amongst all members”. This definition extended to people living on communal lands, which were yet to receive the legal right to establish their own conservancies.

Whether on freehold or communal land, conservancies are voluntary associations that are led by people living within these communities who wish to conserve and use their wildlife sustainably. Conservancies represent a mosaic of Namibia's diverse landscapes, from the arid deserts to lush river valleys, each with their unique challenges and opportunities.

By 1996, the number of freehold conservancies had grown substantially, creating a need for greater coordination and a unified voice to address cross-cutting challenges and cooperation with what was then the Ministry of Environment and Tourism (MET). The Conservancies Association of Namibia (CANAM) was established to meet this need. Supported by MET, CANAM aimed to represent and coordinate all conservancies across Namibia, whether in communal areas or on freehold farmland.

CANAM's objectives are multifaceted. It represents conservancies, liaises with authorities, encourages landowner participation, coordinates research, protects the environment and raises awareness both locally and internationally. Beyond these goals, CANAM embodies a spirit of cooperation and a shared commitment to conservation. During its peak, up to 25 conservancies on freehold farmland were united under CANAM.

The number of freehold conservancies (blue) in 2004.

The number of freehold conservancies in 2024, including dormant ones (pale blue).

Unfortunately, because of the different legal requirements for establishing communal conservancies, they were supported and developed separately from freehold conservancies during that time. This led to limited cooperation across land use types and restricted CANAM to representing freehold conservancies only. This divide has led to declining support for freehold conservancies from government and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) over the past few decades, leading to a decline in CANAM membership and the eventual shrinkage or dissolution of many conservancies.

Freehold farmlands conserve most of the wildlife in Namibia, provide thousands of jobs and contribute to a vibrant wildlife economy. Occupying most of the central parts of the country due to historical land distribution, freehold lands could provide important links between conservancies and national parks on communal and state land. The prevalence of game fencing is a key factor limiting connectivity, which would be addressed through properly supported freehold conservancies.

Under the current Ministry of Environment, Forestry and Tourism (MEFT), freehold conservancies receive no support, in contrast to the early years. Conservancies used to enjoy greater autonomy in terms of wildlife management than individual freehold farmers, thus incentivising landowners to create conservancies. These benefits have been withdrawn, reducing the incentive for freehold farmers to participate in landscape-level conservation. The resulting decline in the number and size of freehold conservancies is detrimental both economically and ecologically, especially as Namibia faces the dual challenges of climate change and international pressure regarding the sustainable use of wildlife.

Looking beyond Namibia, freehold conservancies contribute to global conservation targets, particularly Target 3 of the Global Biodiversity Framework that aims to protect 30% of the planet's land and oceans by 2030 (known as the 30 by 30 target). Freehold conservancies already comprise vast tracts of land that support biodiversity and wildlife conservation and therefore meet the international definition of Other Effective Area-Based Conservation Measures (OECMs). They also protect

vegetation types which are not adequately protected by national parks. To make significant gains for global conservation, the Namibian government only needs to formally recognise freehold conservancies as OECMs that contribute to the global 30 by 30 target and incentivise their formation through minor policy changes. This would restore game migrations in Namibia, assist predator conservation efforts and allow for greater collaboration across land use types.

CANAM is ideally positioned to revitalise the freehold conservancy membership and create a win-win partnership between the public and the private sector. We are willing to work with MEFT to identify key policy changes that would incentivise farmers to once more establish (or revive) their conservancies and work closely with the government to achieve the joint goals of nature conservation and sustainable rural development.

CANAM continues to advocate for freehold conservancies to be rightly recognised as contributors to national and global conservation goals. The vision for the future is clear: a robust network of conservancies that support biodiversity, sustain wildlife and provide economic benefits. The story of CANAM and Namibia's freehold conservancies is one of resilience, cooperation and hope.

By John Pallett and Ndelimona IipingeNamibian Environment and Wildlife Society

In an ideal world the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) process would ensure that any development project in Namibia is socially just and environmentally sustainable. In reality, the whole process appears to be a boxchecking exercise that serves a wealthy and well-connected few at the expense of the majority of Namibians and our environment.

How do we know that EIAs are not working in Namibia? Our assessment is based on evidence from tracking all EIAs in Namibia since May 2023 on the EIA Tracker. The EIA Tracker logs all EIAs that are registered with the Office of the Environmental Commissioner (OEC) in the Department of Environmental Affairs (DEA) and places all the relevant information on the web for easy access – forever. If you want to check out the environmental details behind a new or existing project since May 2023, or what conditions were set in the Environmental Management Plan (EMP), the EIA Tracker can help you. Details on older projects between 2019 and May 2023 are available from Namibia’s Environmental Information Service (EIS).

Without the Tracker you can only get this information from the DEA for a short period when the EIA is active. Thereafter the DEA deliberately makes it difficult for anyone trying to find out more about an EIA. This is a significant concern, because the EMP sets out how the project should be run and what it has undertaken to do to mitigate social and environmental impacts. This information is hidden from the public. As the OEC seldom inspects projects, there is no accountability for EMPs being implemented.

Offers practical guidance in order to make the development socially just and environmentally sustainable.

Welcomes comments and concerns from Interested and Affected Parties (IAPs), which improves the outcome of an EIA.

The Environmental Assessment Practitioner (EAP) is competent and responsible, and open to information that will improve the social and environmental outcomes of the development.

The government department overseeing EIAs is efficient, and intent on achieving the best outcome from the EIA process.

BID Background Information Document

DEA Department of Environmental Affairs in the Ministry of Environment, Forestry and Tourism

EIA Environmental Impact Assessment

EAP Environmental Assessment Practitioner

ECC Environmental Clearance Certificate

EIS Environmental Information Service

EMP Environmental Management Plan

EPL Exclusive Prospecting Licence (for geological exploration)

IAP Interested and Affected Party

OEC Office of the Environmental Commissioner

A box-ticking exercise to get an Environmental Clearance Certificate (ECC).

Often hidden from public scrutiny, while public inputs are downplayed or ignored.

No qualification is required for EAPs, and young entrepreneurs see EIAs as an easy business opportunity. EAPs are eager to please the developer and willing to bend rules and cut corners to do so.

The government department overseeing EIAs is slow, opaque and unresponsive to suggestions.

The EIA Tracker provides information on every project that is applying for Environmental Clearance, based on the Background Information Document (BID) provided by the relevant Practitioner. Based on this information each project is classified as high, medium or low risk. Although any member of the public has the legal right to access any BID, our attempts to do so have been an eye-opening exercise! In many cases, EAPs unlawfully refuse to provide the BID. These same Practitioners are often associated with placing EIA adverts (another legal requirement) in obscure places, such as the tiny print of the classified ads section of a newspaper. These are deliberate measures by some EAPs to keep the EIA out of the public’s sight. The EIA Tracker has reported them to the Environmental Commissioner – with no response.

The projects we assess as high risk are those which carry significant environmental and social issues, such as large mines and dams. They require a thorough EIA, usually with specialist studies on water, biodiversity, social issues, archaeological impacts and so on. Medium-risk projects carry slightly lower risks for the environment and people, such as possible pollution and risks to water resources that are manageable with the appropriate mitigations. These more common projects include geological exploration (since every Exclusive Prospecting License, EPL, requires an ECC before it can commence activities), small mines and powerlines. Low risk projects carry generally insignificant impacts for people and the environment. Examples include rezoning in

The percentage of projects requiring EIAs in Namibia that fall into high, medium and low risk categories, based on data collected in the EIA Tracker from May 2023 to July 2024.

urban areas, fuel stations, small earth dams, most lodges and solar farms that are outside sensitive areas.

Of the 1,189 EIAs registered with the DEA in the 15-month period up to July 2024, 52% were low-risk projects. These relatively trivial EIAs occupy a large proportion of the DEA’s effort and time, each taking about three months from submission of the EIA to issuance of the ECC. In our opinion, this is wasted effort. They could more efficiently be handled through a simplified checklist, speeding up the process and freeing up time for more important matters, where more thorough due diligence on significant EIAs is needed.

An example of an EIA that deserved greater scrutiny and which should not have been given the go-ahead, was an EPL in a prime tourism area near Khorixas. The BID drew attention to the presence of rhinos in the area, which prompted Save the Rhino Trust and local lodge owners to raise concerns against the project. The EAP fraudulently stated that the risks to biodiversity were low. The ECC was issued despite this clear irregularity and major negative impacts, and the geological exploration project has gone ahead. This and many other similar examples reinforce the view held by many that the EIA process cannot be trusted, and that it is at best just an administrative procedure to tick the ECC box, or at worst, an area of growing concern about corruption.

An Environmental Management Plan should stipulate that oil spills be prevented. Pollution such as this is rampant, since there is little enforcement of EMPs by the regulating authority, MEFT.

Landscape scars can be avoided through thorough rehabilitation after mining. The EIA process addresses rehabilitation, but in many cases it is ignored, and there is no enforcement of the mine’s responsibilities.

The EIA Tracker team met with the Environmental Commissioner and his senior staff to discuss these problems and made several recommendations, including the need to establish in law a professional body for EAPs, like those for earth sciences, medical and engineering professions. Such an organisation – the Environmental Assessment Practitioners Association of Namibia (EAPAN) –has been in existence for a decade as a voluntary association, but it gets little recognition and no support from the DEA. EAPAN ensures that its members have the required qualifications and experience, and abide by a strong code of professional conduct. Proponents of projects looking for professional EAP services would be advised to approach members of EAPAN.

At this stage, only half (48) of Namibia’s 93 EAPs are registered with EAPAN, and only one third (337 out of 1,189) of the EIAs registered in the past 15 months were conducted by EAPAN-registered EAPs. The Environmental Commissioner has promised to give priority to a professional body for EAPs, but so far, nothing. This relatively simple step would ensure that only members of EAPAN would be allowed to prepare EIAs, thus eliminating unscrupulous and unqualified individuals from the pool of potential practitioners that developers can employ.

The EIA Tracker is one step towards improving transparency of the EIA process by allowing affected parties to contribute information on high-impact projects and gain access to documents that are not provided by the DEA. A democratic and transparent EIA process is in the interest of improving overall environmental management. When the public is fully engaged with development projects, those projects are more likely to have sustainable and socially acceptable outcomes. This is the ultimate objective of the Environmental Management Act.

The Tracker has shown us that many aspects of the EIA process are currently failing in Namibia. Our message to the OEC, based on the solid facts revealed by the EIA Tracker, shouts out: “Clean up your act!” We call on the Environmental Commissioner to implement the Environmental Management Act in a professional manner as part of his duty to work on behalf of all Namibians.

Geological explorarion may involve drilling, earth-moving and a construction camp. These activities can have significant repurcussions on local people, tourism operations and wildlife in the area.

The EIA Tracker is a project run by NEWS with funding from the NCE. Sincere thanks to NCE for the ongoing financial support and suggestions.

To find EIAs from May 2023, visit the EIA Tracker at www.eia-tracker.org.na

To find EIAs between 2019 and 2023, visit the EIS at the-eis.com/elibrary/ search-result-custom?topic=130960

By John Mendelsohn

Africa has many special features. Among them is the exceptionally high plateau stretching across the southern half of the continent and rising 1,000 metres and more above the surrounding Atlantic and Indian Oceans (see map below). A large part of this plateau forms the great Kalahari Basin, renowned for being the biggest continuous area of sand on planet Earth.

Another special feature is the Great Escarpment, which encircles this plateau. In the west the Great Escarpment stretches south from Gabon through Angola, Namibia, into South Africa and then east and north all the way to Ethiopia. In many areas the Great Escarpment and its peaks rise to 2,000 metres or more. Most rivers either flow rapidly down to the surrounding coast or lazily into the broad plain encompassed by the Great Escarpment.

Biologists have long focussed their attention on species found only on these highlands. Studies in the Ethiopian highlands, Tanzanian Eastern Arc Mountains, Zimbabwe Eastern Highlands, South African Drakensberg and Cape Fold Mountains have made these areas famous for their endemics, the term for organisms found only in certain restricted areas. However, relatively little information was available about endemism on the highlands of Angola and Namibia.

The Namibian Journal of Environment (https://nje.org.na) recently published a review written by 64 people from around the world, most of them specialists in their fields of study on particular groups, for example euphorbias, petalidiums (petal-bushes), reptiles and butterflies. The review consists of 26 articles and runs to 338 pages. Individual articles or the whole book can be downloaded for free (see QR code and link at the bottom of this article).

Broadly, the review seeks to answer five key questions: 1) What characterises the highlands’ structure, climate, biota and land uses? 2) How diverse are the taxonomic groups represented in the highlands? 3) How many endemics have been catalogued there? 4) Where are centres of diversity and endemism located within the highlands? 5) How are highland species and subspecies related to similar plants and animals found elsewhere in Africa?

The monograph focuses on the highlands and escarpments that stretch some 2,700 km from Cabinda and the Congo River southwards to the Orange River on Namibia’s border with South Africa. Two plateaus 1,700 metres and more above sea level cover large areas: the Angolan Planalto and Namibia’s Khomas Hochland. Both occupy central areas in their respective countries. Numerous inselbergs (isolated mountains) rise above the landscape, and many scarps form sharp margins between lower, western and higher, eastern areas. The highest peaks rise to about 2.5 kilometres above the sea, the best known in Namibia being the Brandberg (2,573 masl) and Moltkeblick (2,489 masl) on the Auas mountains.

The rim of highlands around the margins of Africa and its high internal plateau south of the Equator. The blue line demarcates the highlands of Namibia and Angola.

Average annual rainfall ranges from about 1,200 mm in the north of Angola and on the Angolan Planalto to less than 100 mm in the far south of Namibia. To the south, declining rainfall as well as increasing evapotranspiration make the southern areas much more arid than those to the north. As a result, verdant tropical forests characterise the northern parts of this western section of the Great Escarpment while its southern areas support sparse covers of small grasses, shrubs and succulents.

The monograph begins with chapters summarising its main findings (to which I will return), and the ecoregions, and physical and human geography of HEAN – our acronym for the Highlands and Escarpments of Angola and Namibia. Other early chapters present detailed maps

of the HEAN, the geology and landscape evolution of these highlands, and the challenges facing the conservation of Angolan highlands.

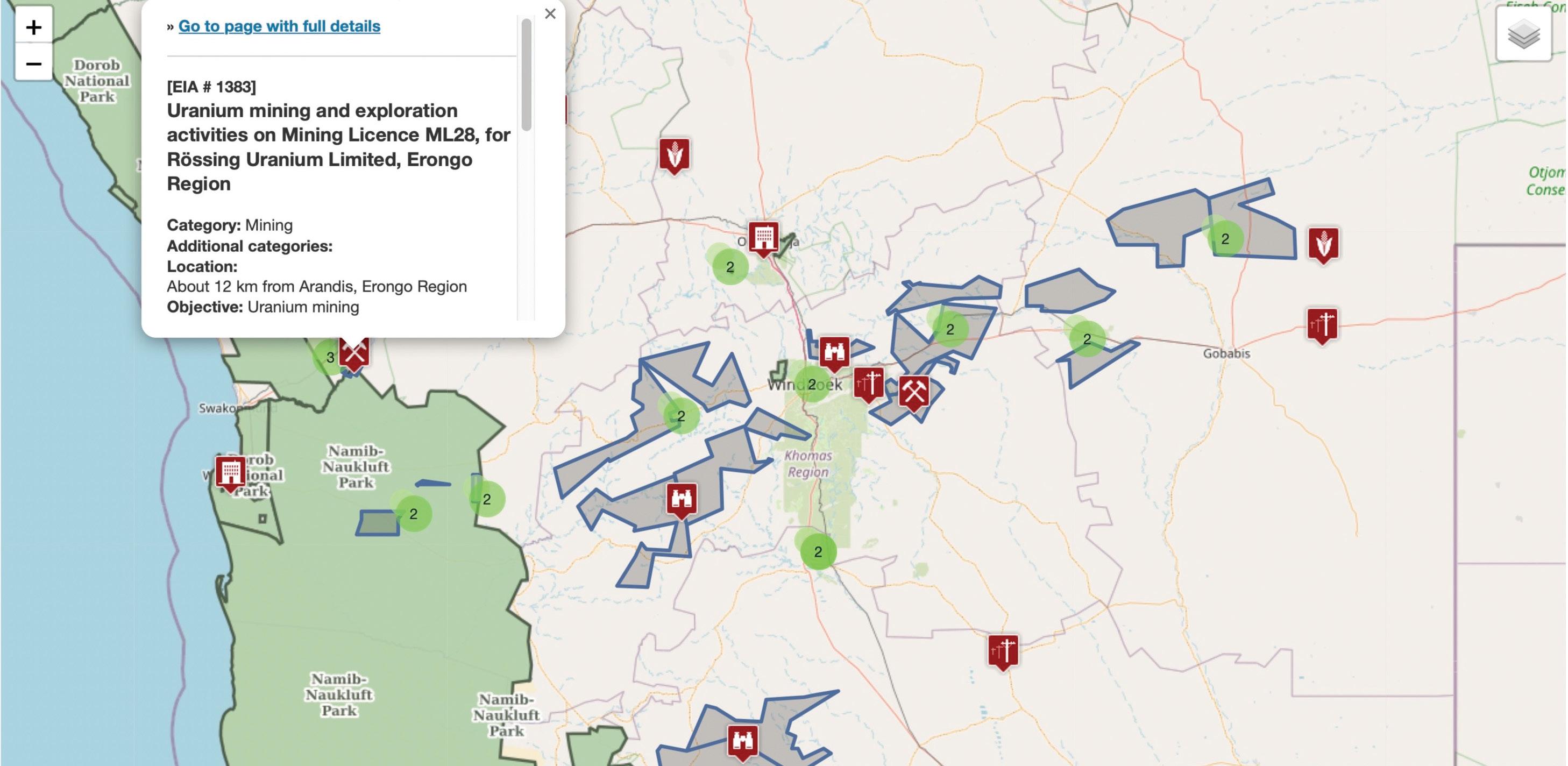

Then follow chapters on the HEAN’s endemic arachnids (spiders, scorpions and allies), birds, reptiles, flat geckos, ants, lacewings and antlions, termites, mammals, frogs, reptiles, fishes, Petalidium plants, Ceropegieae and euphorbia plants, and commiphoras.

Other chapters focus on endemism in certain areas: plants on and around Angola’s Mount Namba, plants and animals in northern Angola’s Serra do Pingano mountains, plants in Namibia, underground geoxyle plants on Angola’s central Planalto, and dragonflies and damselflies in Angola, and animals occurring mainly in caves.

Namibian authors who contributed include Roy Miller, Wessel Swanepoel, Leevi Nanyeni, Frances Chase, Alice Jarvis, Pat Craven, Francois Becker and Herta Kolberg.

What was found

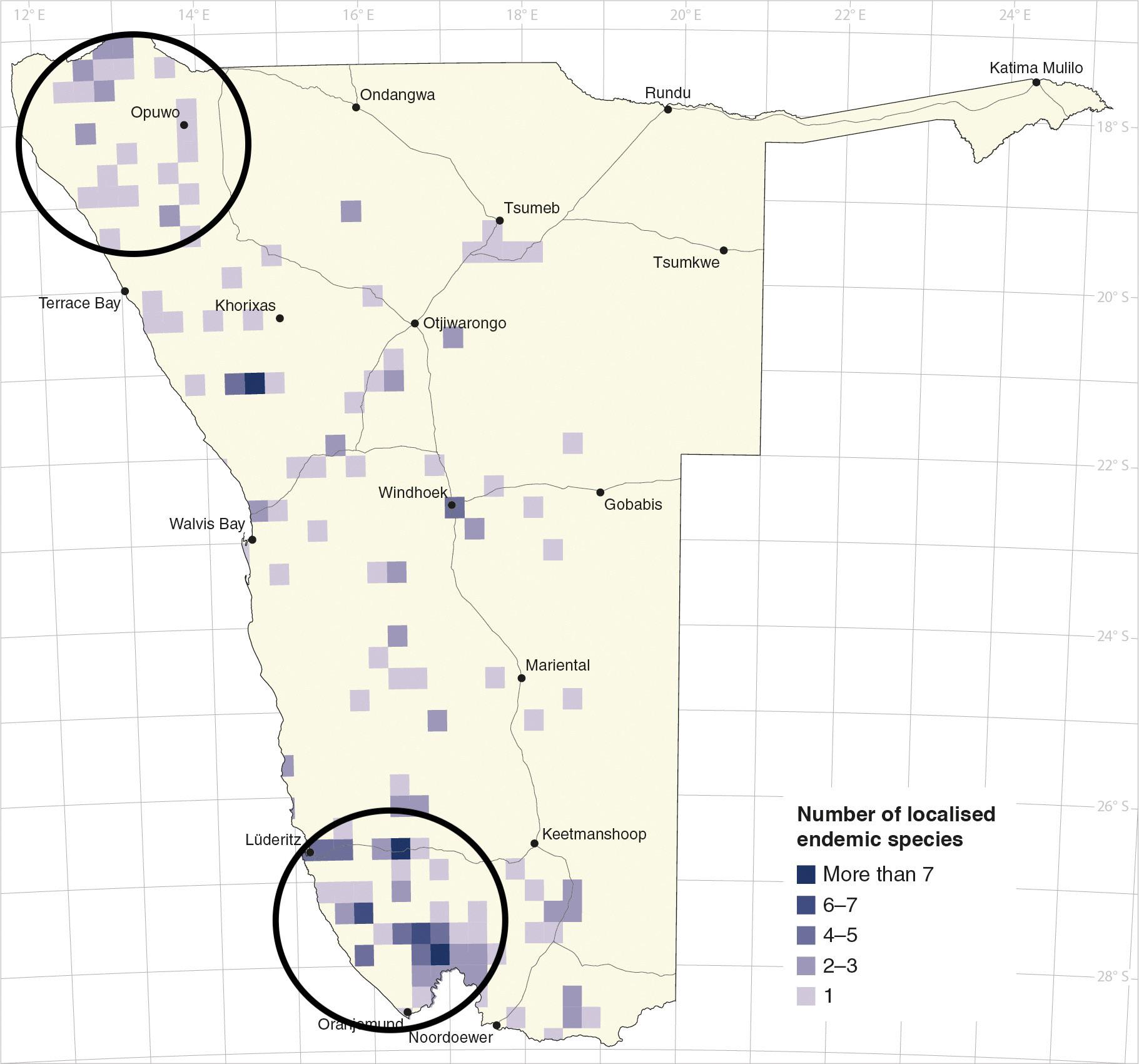

Lots of endemics! Among the taxa reviewed at least 570 known animals and plants are now known to be endemic to the HEAN. But the number would be quite different if other groups could have been added to the review. These include groups that have many species, such as beetles, flies, bugs, crustaceans, round (nematode) and segmented (annelid) worms, snails and allies, mosses and allies (bryophytes), algae and others.

In Namibia, of some 4,000 species of indigenous seed plants, over 100 are known only from the highlands. In their chapter, Pat Craven and Herta Kolberg found that Brandberg is home to over 480 indigenous seed plants, of which about 90 are Namibian endemics and nine are limited to the mountain itself. Kyle Dexter and his coauthors found that 22 of the 36 African species of Petalidium are endemics or near-endemics to the HEAN. Among the 570 endemics found in this area, some are particularly charismatic and well-known among naturalists, such as Angola Dwarf Galagos, Angola Cave Chats, and Swierstra’s Francolins.

The authors of the articles in the review would agree on several priorities. Special emphasis should be placed on exploring neglected regions and habitats within the HEAN. We also need to take stock of endemism among other taxonomic groups not covered in this publication. Effective conservation measures are urgently required to protect the fragments of relict forests, grasslands and savannas that carry the products and evidence of many millions of years of evolution. These habitats are progressively decimated by frequent hot fires, charcoal production and the clearing of woodlands and forests for shifting agriculture. Pedro Vaz Pinto and his coauthors working in Angola stressed the urgency of conservation interventions in the country.

Perhaps the most striking conclusion is how little is known about most plants and animals that live only on our highlands, and for which Namibia and Angola are fully responsible. Much of this ignorance is due to a scarcity of records in museums, herbaria and digital databases, such as the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF www.gbif.org). But there is also a great shortage of students and scientists who study different groups of organisms.

The collection of specimens, fieldwork, and studies of biogeography, taxonomy and systematics are no longer fashionable. Indeed, much of the information on which humanity now relies was collected by hardy, brave explorers, missionaries and naturalists who trudged their way across Namibia, Angola and beyond 50, 100 and 150 years ago. Where is the new generation of naturalists to fill the gaps and document recent changes? How many species known to scientists in Angola and Namibia a century ago no longer exist? We can only dream about those we don’t know, and never will!

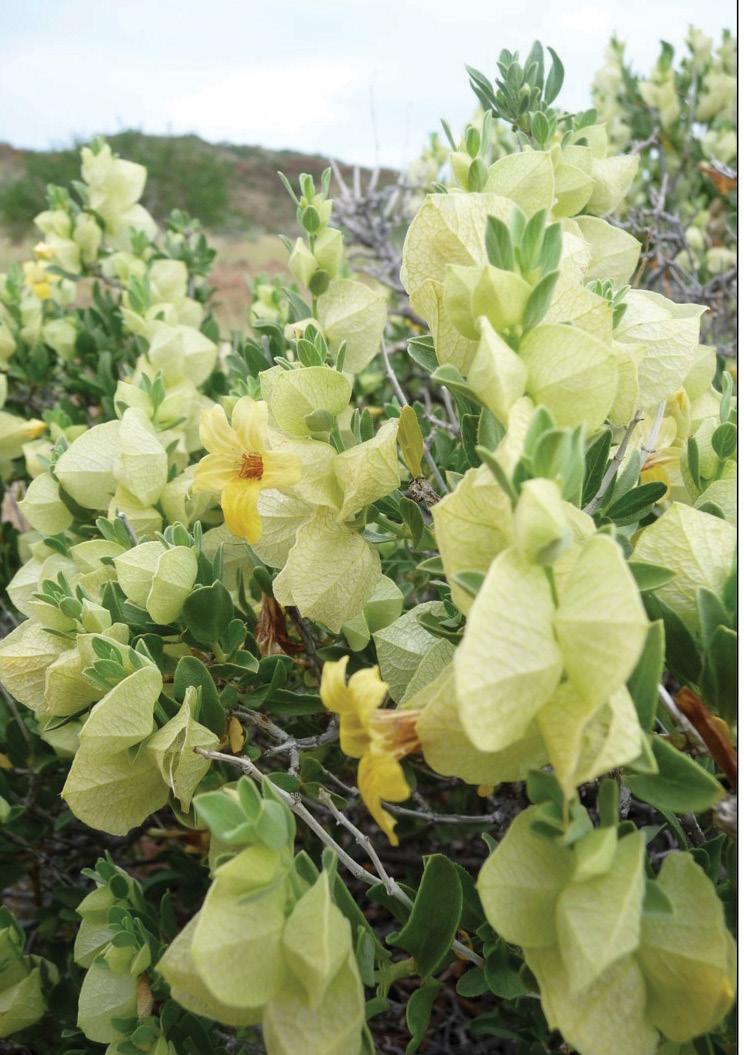

Twelve Petalidium species endemic to the highlands of Namibia: A) Petalidium cymbiforme (EMT), B) Petalidium rautanenii (EMT), C) Petalidium ohopohense (EMT), D) Petalidium subcrispum (EMT), E) Petalidium pilosi-bracteolatum (EMT), F) Petalidium sesfonteinense (KD), G) Petalidium crispum (EMT), H) Petalidium angustitubum (LN), I) Petalidium giessii (EMT), J) Petalidium rossmanianum (EMT), K) Petalidium lanatum (EMT), L) Petalidium kaokoense (EMT).

Great credit goes to the Ongava Research Centre and Namibian Chamber of Environment for material and financial support. Similar support from the institutional homes of the many authors is likewise acknowledged. More personally, I am indebted to Brian Huntley and Pedro Vaz Pinto for their help in editing the volume and to Alice Jarvis and Carole Roberts for their dogged determination to get the language, style, and layout done correctly!

Credits for the magnificent photos in this article are: AMB – AM Bauer, BB – B Branch, EMT – E Manzitto-Tripp, ES – E Swartz, FB – F Becker, JLR – J Lobón-Rovira, JM – J Marais, JP – J Penner, KD – K Dexter, LMP – LMP Ceríaco, LN – L Nanyeni, NLB – NL Baptista, PS – P Skelton, PVP – P Vaz Pinto, RB – R Bills, WC – W Conradie.

Download the full publication by scanning the QR code or visit: https://nje.org.na/public/ journals/1/TOC-volume8.pdf

By Herta Kolberg and Sofia Amakali

Plants are the basis of almost all other life on earth, yet they are highly undervalued in Namibia due in part to the lack of knowledge about indigenous plants among ordinary citizens. Some of Namibia’s plants are rarer and more highly threatened than black rhino, yet few people could even name them. As plant poaching becomes increasingly prevalent, more Namibians need to know why plants are important and what they can do to conserve them.

To improve awareness and better manage our plant resources, we started collecting all existing knowledge on Namibian plants in one user-friendly database. Since we have close to 4,200 indigenous plants, we had to divide this task into more manageable sections and decided to start with endemic and near-endemic species. “Endemic” refers to plants that occur nowhere else on earth. Our near-endemics occur mainly in Namibia, with smaller parts of their ranges in other countries. As the only or primary national custodian of these plants, Namibia has a particular responsibility to conserve these species.

The challenges and rewards of building a plant database

Quite a substantial amount of information on Namibian plants is available, but it is scattered throughout the world in different sources and formats, including online databases, herbaria, scientific articles, internet sites, unpublished reports, postgraduate theses, field notes and photo collections. Most of this information is not accessible to laymen, mainly due to language barriers (much of it is in German), financial resources (getting access to published articles can be expensive) or complex terminology that only experts understand.

Besides these challenges, much of the information is inaccurate or simply wrong, especially on the internet. This is often due to websites being managed by laymen or even professional botanists who do not know Namibia and its flora or do not understand German. We want to correct these errors and present a definitive data set for Namibian plants.

To this end, I (Herta Kolberg) started a database of indigenous Namibian plants more than 40 years ago. This was later combined with my colleague Patricia Craven’s database, to which we added information as it became available. This soon became an overwhelming, full-time task.

In 2022, Patricia and I were funded by the Namibian Chamber of Environment to update the endemic plant information and enter it into the Environmental Information Service Namibia (EIS), which hosts atlases for many species groups and a library of information about Namibia. This was the first time plant information was included in the EIS. In May 2023, I obtained funding from the JRS Biodiversity Foundation to update the information for near-endemic plants over two-and-a-half years; enlisting the help of Sofia Amakali to enter the data. Our ultimate goal is to bring together all existing information, verify, summarise and analyse it and make it available freely online through the EIS. We aim to publish information that is scientifically correct, yet understandable and useful to the layman.

The Plant Information System on the EIS now lists all the indigenous plants recorded in Namibia. One of our significant challenges is deciding which scientific names to use, since these change quite frequently as scientists investigate how different plant species and genera (the category above species) are related to each other. In some cases, a plant may be renamed by one scientist and then changed back to its old name by the next scientist. The scientific community has numerous ongoing debates about which names are correct.

In recent times, many plant naming decisions are based on molecular (DNA) differences between plants or groups of plants. If the differences between plants at the molecular level are not related to what you can see and use to identify a plant (known as morphological differences), this is of no use to the field botanist or layman. Foreign researchers often do not use Namibian specimens in their work for

plants indigenous to the country, but also occur elsewhere. This leads us to question whether their results also apply to Namibia. For these reasons, we do not accept all name changes for Namibian plants and instead stick to the ones we know until there is better evidence and disputes are settled. This is not just our view – many botanists worldwide have called for greater stability of plant names.

Exploring and contributing to the plant database

When exploring the EIS Plant Information System you will find basic information, where available, for each plant species. This includes the plant group (Dicotyledon, Monocotyledon, Gymnosperm), plant family, lifeform (tree, shrub, grass, etc.), status (endemic, near-endemic), legal status (if it is protected in Namibia and by which law) and the region or regions in Namibia where it can be found. You will also find out how threatened the species is according to the International Union for the Conservation of Nature’s red list and whether or not trade in this species is regulated by the Convention on International Trade of Endangered Species (CITES).

Each endemic and near-endemic species entry (336 of 618 species targeted for the JRS-funded project completed thus far) includes a link to a species information sheet, which contains all the information we have as well as a distribution map and some photographs of the plant, when these are available. Eventually, we want to produce these sheets for all indigenous Namibian plants. We use information from specimens collected in Namibia to generate the plant descriptions. This makes the descriptions truly Namibian, because plants of the same species may look slightly different in other countries where they occur, mainly due to different growing environments. This guide should make it easier to identify plants in Namibia.

As we develop information sheets for each species, we discover the need for more information that could be supplied by Namibians who are acquainted with these species. First, many of the common names of each plant in different languages may be mis-spelt or absent. We included only published names, found on herbarium specimen labels or in reports and an index card system created by the late botanist Willy Giess. We retained the spelling used in the source, but realise that this may be outdated or wrong. For this reason, we appeal to speakers of the various languages to give feedback on any such

mistakes. Not many local names are recorded for the endemic and near-endemic plants – if anybody can provide additional names, we would be very grateful.

Secondly, we have little or no information on the traditional uses of many endemic and near-endemic plants. On the species sheets, we include only broad use categories (e.g., food, fodder, medicinal) and only information that is already in the public domain to protect the intellectual property of the holders of that knowledge. Recording traditional uses for plants is nonetheless an important task, and we invite any traditional knowledge holders to work with us to preserve this information.

Thirdly, we have few photographs of all the endemic and near-endemic plants, which limits the usefulness of this database for people to identify these species correctly. The JRS-funded project includes two field trips annually to obtain photographs and make other botanical discoveries. We completed one trip to southwestern Namibia and one to the northwest, during which we took photographs of 226 species, but we are still missing photos of just over 200 species. To fill this gap, we launched a competition to encourage the citizen science community to submit images to the Indigenous Plants Atlas of the

EIS. Cash prizes were offered to the top three contributors of nearendemic plant photos. Unfortunately, the drought seems to have put a damper on the number of records submitted by atlasers and we haven’t received as many photos as we had hoped.

Our two field trips resulted in several interesting discoveries that reveal how much more is yet to be discovered about Namibia’s plant diversity. In the northwest we found one species (Lamiaceae family) possibly new to science and two species (Hybanthus mossamedensis, Distimake aegyptius) known only from outside Namibia up to now. We also recorded one species (Cleretum papulosum), known only from South Africa until now, on the field trip to the southwest. Based on this success, we look forward to future trips to add to our knowledge of Namibian plant species.

During the current project, we trained 37 stakeholders, 13 junior staff or interns at the National Botanical Research Institute and a project intern. Mentoring new plant scientists and transferring the knowledge I have accumulated during my long career in Namibian botany are important parts of this endeavour. Since this work will continue long

into the future, we need many more dedicated young Namibian botanists to take up this challenge.

Once we have completed the current work with endemic and nearendemic species, we aim to produce an electronic record of all the plants in the country. Each record will include basic information about a plant: an identification key, description, distribution, old names (synonyms), voucher specimens and more. This should allow the user to identify plants. To publish a hard-copy Flora book with full colour photographs of each plant would not be feasible, firstly because by the time a book is published, the information is already out of date and secondly because of cost. We are therefore working towards a digital, online Flora for Namibia, which can be kept up to date with the latest discoveries and science.

We will complete the present phase of the programme, focusing on endemic and near-endemic plants, during the next 15 months. Towards the end of the project, we will demonstrate how the information on the EIS can be used for the different purposes of our stakeholders. Once this phase is completed, we need to identify further funding sources to move on to another group of plants. We were thinking of dividing the remaining species (over 2700) into categories linked to their growth form (e.g. trees, grasses, bulbs) or use type (e.g. forage, medicinal, cultural). If we maintain our current rate of progress, this work should keep us busy for the next 12 years!

• We have close to 4200* plants indigenous to Namibia.

• About 700* of these occur nowhere else on earth (endemic to Namibia).

• For about 715* plants, the largest part of their distribution range is in Namibia, with a smaller area extending into one of our neighbouring countries (near-endemic to Namibia).

• Namibia has a full responsibility to protect endemic species and a greater duty to conserve near-endemic plants.

* It is impossible to give exact numbers, because there is continuous research conducted worldwide

distribution ranges updated.

Work on the endemic and near-endemic plants programme requires many hours of searching for data and digitising this, but we also get to enjoy the highs and lows of fieldwork and visit some beautiful places.

By Esmerialda Strauss, Leevi Nanyeni and Theunis Pietersen

Namibia is renowned for its rich diversity of endemic succulent plants, which unfortunately, makes it a target for plant poaching. While Namibia welcomes the interest of plant lovers to see our plants in their natural habitat, increasing attention from illegal plant poaching syndicates is a troubling development.

Most of our unique succulents occur in the Kaokoveld Centre of Endemism in north-western Namibia, which continues into Angola, and the Gariep Centre of Endemism in south-western Namibia, which continues into South Africa. These remote areas are vulnerable to cross-border smuggling and difficult to patrol, while many of the plants growing here occur nowhere else (known as endemic species).

Plant poaching in Namibia used to be restricted to occasional, isolated incidents. Since 2021, we have recorded a sharp increase in plant poaching activities due to the increased trading in rare plants ascribed to global trends in online trade of succulents for ornamental purposes. In the initial stages of this spike, most border officials had never encountered plant smuggling and therefore could not identify species of conservation concern.

Investigators have established that international crime syndicates drive the Namibian plant trafficking operations, employing Namibian nationals to harvest endemic and protected plant species illegally using their local knowledge. The plants are then smuggled across Namibian borders

and sold to international plant collectors. From January 2021 to April 2024, 16 wildlife crime cases involving ten protected plant species were registered and 37 suspects were arrested. A staggering 4,128 individual plants were confiscated during these arrests, indicating the level of threat these activities pose to the survival of these species.

In response to increased plant poaching activities, the Ministry of Environment, Forestry and Tourism, the Namibian Police Force and the Namibian Revenue Agency established the Protected Plants Task Team (PPTT) in 2023. This initiative is similar to the Blue Rhino Task Team that focuses on animal poaching.

Among the priority tasks for the PPTT is to ensure that border officials are made aware of this problem and have clear Standard Operating Procedures to follow when intercepting plant traffickers. The PPTT team developed several posters, plant identification guides, and training curricula for border officials and law enforcement staff. This training and awareness programme was later extended to community members in communal conservancies in the northwest that host highly targeted species. A total of 242 community members from five conservancies were trained, who will help spread the word that these plants are threatened and that plant poaching is a crime.

Members of the PPTT undertook a Flora-Focused Trafficking visit to South Africa to engage with counterparts and share experiences and lessons learned on the illegal harvesting, trafficking, and trade

of succulent plants. Our South African colleagues included botanical experts, non-governmental organisations working on plant conservation, and relevant government officials.

Our collective efforts resulted in a significant breakthrough in November 2023 with the arrest of Diana Mashiku, a plant poaching kingpin from Tanzania, and her three Namibian accomplices. The suspects were arrested for possession of 46 Adenia pechuelii plants, known as Elephant’s Foot. This near-endemic species is highly sought-after by international plant collectors because of its peculiar shape that comes from growing in rocky areas. Unfortunately, plants from the wild are preferred as plants grown in the nursery tend to have a uniform shape. Based on the rate of illegal harvesting, Adenia pechuelii is threatened with extinction.

The kingpin, Ms. Mashiku, was charged with contraventions of the Prevention of Organised Crime Act 24 of 2004 (POCA), and the Forest Act 12 of 2001, as well as violations of the Immigration Act (conducting business without a permit). She entered a guilty plea and was sentenced to a fine of N$ 4000 (or twelve months imprisonment) for the Forest charges and another N$ 4000 (or imprisonment) for violations under the Immigration Act. The organised crime charges relating to illegal commercial activities carry heavier sentences – she was therefore fined a further N$ 20 000 (or five years imprisonment). The same charges against her Namibian co-accused persons are still pending. These additional charges and sentences might carry a stronger deterrent message, although the value of these plants on the international market continues to incentivise poaching.

This case revealed a new dimension of wildlife crime in Namibia and laid the foundation for collaboration between local law enforcement agencies and their counterparts in foreign jurisdictions. Namibian and Tanzanian

Authors

*Esmerialda Strauss, Deputy Director Forest & Botanical Research, Directorate of Forestry, Ministry of Environment, Forestry & Tourism, Private Bag 13306, Windhoek, Namibia

**Leevi Nanyeni, Senior Forester, National Botanical Garden of Namibia, National Botanical Research, Directorate of Forestry, Ministry of Environment, Forestry & Tourism, Private Bag 13306, Windhoek, Namibia

***Theunis Pietersen, Control Warden, Intelligence Investigation Unit (IIU), Directorate of Wildlife and National Parks, Ministry of Environment, Forestry & Tourism, Private Bag 13306, Windhoek, Namibia

officials working for their respective environment ministries were able to discuss this issue further during the African Wildlife Forensic Network workshop in November 2023. The criminal connections between the two countries are being further investigated to uncover trafficking routes and identify kingpins in the international syndicates.

What happens to the plants in these cases? Unlike poached animals, plants get a second chance at life, although replanting and caring for them is a costly exercise that may fail if the plants are too stressed. All consignments intercepted and confiscated are handed over to the National Botanical Research Institute (NBRI) in line with the Chain of Custody. NBRI staff provide the plants with initial care in nursery conditions, replanting healthy individuals within their natural habitat. Once the confiscated plants have been replanted in suitable habitats under the custodianship of landowners and communities, they are monitored at least once a year to determine the plants’ survival rate and health status.

Preventing the illegal harvesting, trafficking and trade of endemic and protected plant species is an important part of the overall fight against wildlife crime. The PPTT has made a promising start, illustrated by the increase in interception of illegal consignments and number of criminal cases registered. We continue to raise awareness among government officials and local communities about the threats that plant poaching poses to our environment, while our joint law enforcement efforts ensure that plant traffickers are arrested and prosecuted for their crimes.

The PPTT consists of members from the Ministry of Environment, Forestry and Tourism (MEFT) represented by the National Botanical Research Institute (NBRI) of the Directorate of Forestry and the Intelligence Investigation Unit (IIU) of the Directorate of Wildlife and National Parks (DWNP); the Protected Resources Division (PRD) of the Namibian Police; and the Namibia Revenue Agency (NamRa), the latter three entities also forms part of the multi-agency Blue Rhino Task Team, with technical support provided by the United States Forest Service International Program. The PPTT is supported by the RooiKat Trust; the Namibia Nature Foundation; the US Department of State, Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs (INL) and the US Fish and Wildlife Service.

in northwest Namibia

By