Since 1999

WHY HUNTING MATTERS

CONSERVATION HUNTING IN NAMIBIA

NAMIBIA'S ULTIMATE HUNTING TALES Celebrating a country, and industry's, conservation successes

Discover the very best of Namibia

DAILY hop on hop off shuttle flights to Namibia’s top destinations... at the price of a self-drive. Spend less time travelling and more time discovering the wonders of Namibia. With special rates and packages available for all NAPHA members and their clients. Contact info@flynamibia.com.na.

Cover

Such an iconic sight in Namibia... a gemsbok bull scaling the soft sandy dunes of the Namib.

Photo by Jofie Lamprecht

Read the latest and older issues of Huntinamibia online. Huntinamibia’s website also contains a wealth of information sourced over two decades. It is an archive of material which has appeared in the printed magazine since 1999.

Publisher

Venture Media

PO Box 21593, Windhoek, Namibia www.huntnamibia.com.na www.travelnewsnamibia.com

Managing Editor

Elzanne McCulloch elzanne@venture.com.na

Administration Bonn Nortje bonn@venture.com.na

Design & Layout

Liza de Klerk design@venture.com.na

Printing

John Meinert Printers (Pty) Ltd

Huntinamibia

is published annually by Venture Media in collaboration with the Namibia Professional Hunting Association (NAPHA) and with the support of the Namibian Ministry of Environment, Forestry and Tourism.

Editorial material and opinions expressed in Huntinamibia do not necessarily reflect the views of Venture Media and we do not accept responsibility for the advertising content.

Some of my very first memories are of seeing a bright white flower as it glowed in the early morning light from its perch on a trumpet-thorn bush. Or of the feel of a shepherd tree’s bark under my fingers. The most visceral memory is probably the ice-cold sting of the early morning air biting your cheeks on the back of the ancient Cruiser bakkie as it dips and weaves along the two-track path through acacia bushland. Many of you, many Namibians, know that sting well. The cold so invigorating that it ignites a fire inside. For it is the best kind of wake-up call. Better even than the dramatic hues of red and gold that accompany the sun rising to the east. The one that ensures you that you will be spending the day where your soul feels most alive. In the wilderness.

This issue of Huntinamibia is dedicated to the most important question we can find in our community and the broader popular opinion today: Why does hunting matter? The issue is not meant to preach to the converted. The stories inside are of course meant to entertain, inform and inspire, but they are also meant to reinvigorate the spirit within all of us. Your spirit as a hunter and conservationist. To reinstill that firm and tangible knowledge that what you do, what you are passionate about, matters. Especially if done right.

On another level, many of the stories contained in these pages are also aimed at those who are unfamiliar with that clarifying, invigorating, cold sting on the cheeks only found in the wilderness… Those not lucky enough to have grown up or been able to experience the adventure and soul-finding that happens on the back of a bakkie in Africa. Or trekking on foot through some of the earth’s last true wild places. This is a collection of new stories that focus on our topic, combined with some of the very best stories from past issues that prove the point. They are stories from our hearts and minds to theirs . To try and explain, through facts and figures, reason and logic, or sometimes through emotion which they wield as their most comforting tool, why hunting matters. An almost impossible feat to be sure, but as hunters, conservationists, nature-lovers, and Namibians, we are nothing if not hardy and determined people. People for whom the idea of giving up is as far-fetched, unlikely and near-impossible as finding a polar bear while glassing the Kaokoland plains.

The 2022 issue of Huntinamibia is a collection of stories that matter. A good hunting story, I have learnt, allows you to smell the veld around you as your eyes travel across the words. To feel the soft wind rustle around you. Hear the crack of a branch in the brush. Taste the morning

passion of nature within our hearts

dew. A good hunting story has your heart yearning for the African bush and desert plains, but also makes you take a moment to pause and think. Whether the moment is as short as the breath the hunter takes before pulling the trigger, or as languid as the hours spent before traversing rugged terrains in search of the quarry. A good hunting story leads your soul to ponder and then appreciate the whys . Why do we love nature? Why do we feel most alive outside? Why do we care so much about preserving it? Why do we continue to rally, fight and rage despite seemingly insurmountable odds, against the dying of the light. Why does hunting matter?

Thank you to those of you who once again shared your stories with us and continue to allow us the great honour of sharing those stories with the world. Stories that matter and definitively prove why hunting does, too. For conservancies and rural communities. For landscape-level conservation, population management and economic development. For that sense of ownership, pride, passion and tradition. You will find in this issue the true power behind the passion. We unpack why Namibia’s conservancy model and hunting partnerships between private companies and rural communities is a driving force for positive change. We rediscover the importance of hunting to the growth of wildlife populations and land under sustainable management and the role private landowners play in continuously advancing this. We rediscover why we hunt – heritage, passion and purpose at play.

I could not have put this publication together without the firm support of the NAPHA team and our two greatest allies when it comes to the pages of Huntinamibia – Rièth van Schalkwyk who was the editor for 21 years and built a legacy through which we can advocate and share Namibia’s hunting and conservation stories with the world, and KaiUwe Denker, who, more than almost anyone else I know, carries the flame for Namibian hunting and a passion for doing things the right way like a torch through our darkest hours.

Happy hunting, exploring, conserving, appreciating and advocating,

Elzanne McCulloch Editor

Elzanne McCulloch Editor

The icy sting of early morning air to reinvigorate the soul and kindle the

NAPHA MEMBER HOW DO I BECOME A

Obtain your Membership Application Form at the NAPHA Office, or find it on our Website: www.naphanamibia.com

Determine your Membership category.

Fill out the Form, and write a short Motivation as to why you want to become a NAPHA member.

NAPHA MEMBERSHIP CATEGORIES

(Membership cycle: 01 September – 31 August)

Ordinary Member

This member must have passed the official Namibian examination as a hunting professional.

NAD 4,350.00 per annum Applicants below the age of 30 qualify for a 50% reduction: NAD 2,175.00 per annum

Extraordinary

Member

Any natural person living in Namibia (Namibian resident or a person with a valid permanent residence permit) who generates an income from trophy hunting or any person (Namibian resident or a person with a valid permanent residence permit) who has a safari company with trophy hunting as a full-time or part-time occupation qualifies as can be an “Extraordinary member”.

NAD 4,350.00 per annum

Sponsoring Member (Internationals & Namibians)

Any natural person with a personal interest in the implementation of the Association’s objectives, and who does not qualify for Ordinary or Extraordinary membership, qualifies as a “Sponsoring member”.

NAD 2,350.00 per annum

Hunting Assistant / Camp Attendant

Any natural person who does not possess any official Namibian examination qualification as per Section 3.2.1 and is employed by an ordinary, honorary or extraordinary member as a hunting assistant / camp attendant and who does not qualify for any of the other NAPHA membership categories qualifies as a “Hunting Assistant” or “Camp Attendant”.

NAD 350.00 per annum

For Ordinary and Extraordinary Membership submit the following to office@napha.com.

na : A copy of your NTB registration A copy of your MEFT registration A copy of your ID

STEP 1 STEP 2 STEP 3 STEP 4 STEP 5 note

Provide us with 1 Endorsement letter and 3 names and contact numbers within the Hunting industry that can motivate your Application. www.naphanamibia.com

• We are happy to assist with Endorsement letters, and anything you might have trouble with.

• Fees include 15% VAT.

• The membership cycle runs from 1 September to 31 August annually.

• Your application is subject to approval by the Executive Committee of NAPHA.

• NAPHA’s right of refusal or reason / disclosure of non-acceptance of membership application is reserved.

contact us

T: +264 61 234 455

E: office@napha.com.na P.O. Box 11291 Windhoek, Namibia www.napha-namibia.com

CONTENTS

FEATURES: WHY HUNTING MATTERS

AN AFRICAN’S CONVERSATION ABOUT THE CONVERSION OF AFRICAN CONSERVATION - 16

CARRYING CONSERVATION: COMMUNITIES - 30

HUMANITY IN HUNTING - 42

PARAFFIN LAMPS - 46

FUNDING CONSERVATION - 66

A FUTURE FILLED WITH HOPE AND OPTIMISM

The past two years have been challenging for our country in general and for the hunting industry in particular.

Namibia has experienced severe drought over the past few years, leading to incredible losses among our precious game and a reduction in their numbers. These losses affected quota allocation for sustainable hunting.

COVID struck in March 2020, leading to travel restrictions which added to the predicament. Not only did we lose much on personal levels, but our tourism sector suffered incredibly, with recent statistics indicating a decline of 89.4% in 2020 tourism arrivals compared to 2019. However, these challenges present us with an opportunity to look back with a fair measure of pride in our achievements over the course of the year. We should thus endeavour to keep track of these challenges, to provide fitting solutions that will ensure a resilient and sustainable industry. In 2021, the Ministry of Environment, Forestry and Tourism launched the Elephant Conservation and Management Plan, which was developed through extensive consultations with stakeholders, including the Namibia Professional Hunting Association. We believe this is a forward-looking and comprehensive plan which will serve well to ensure the future of one of Namibia’s greatest natural resources for generations to come.

Notwithstanding our successes during the last year, we remain cognisant of the threats and challenges we face here in Namibia. Our constitutional right to sustainably utilise our natural resources is being challenged and under threat from those outside our borders who seem to believe they know better than us how to protect our own natural resources.

These international decision makers are continuously pushing Africa into a corner, bolstered by personal preference opinions and

irresponsible media reports which advise the public that hunting has no place in this modern day and age. At the same time, they display complete ignorance about the science of wildlife management, the vital importance of healthy habitats, and the role that wildlife management plays, or should play, in the maintenance of biological diversities. They make decisions, clearly, having absolutely no experience or understanding of science-based wildlife management –let alone of sharing our beautiful earth with beasts, birds and wildlife.

It is unfortunate that instead of following Africa’s example, they are undermining our efforts, successes and in effect take away the tools with which we in Africa are able to promote and sustain good conservation.

I urge all of us, however, to remain optimistic as we move forward. The Ministry of Environment, Forestry and Tourism will continue to work with the Namibia Professional Hunting Association and other stakeholders, as we have done in the past, to secure the future of conservation in Namibia through sustainable, ethical and sciencebased utilisation of our wildlife. We are glad to have good and close cooperation with NAPHA. We will continue to engage and discuss matters of mutual interest. It is our belief that the resolve and passion shown by members of NAPHA to conserve our natural heritage is a clear indication that hunters in Namibia play, and shall continue to play, a pivotal role in the continued success of the Namibian conservation model.

N. Pohamba Shifeta Namibian Minister of Environment, Forestry and Tourism

ABOUT VENTURE MEDIA

Venture Media is the pioneer of Namibia tourism and conservation promotion. We are the leader in spreading extraordinary Namibian stories around the world. We distribute accurate, credible, up to date and regular information on paper, via social media, on the World Wide Web, and on mobile apps. We have reached hundreds of thousands over almost three decades. Be part of our community and let’s do it together.

T E L L , G R O W , S H A R E

Y O U R S T O R Y W I T H U S I N 2 0 2 1

We're dedicated to telling and sharing STORIES THAT MATTER across our various magazines and digital platforms. Join the journey and share your stories with audiences that understand and value why certain things matter.

Why ethical business, conservation, tourism, people and communities matter. How these elements interrelate and how we can bring about change, contribute to the world and support each other. Whether for an entire nation, an industry, a community, or even just an individual.

www.venture.com.na or email us at info@venture.com.na for a curated proposal.

uss

harin

MATTER acro azin orm and share you enc and things matte ess rism munities matt em d ho ut change, wo ch o n entire natio an industry, a community, or even just an individual.

We believe that sustainability is the only way to ensure that our children (and their children) have the privilege of hunting genuinely wild game ethically, as we have done for generations.

WHY DO WE HUNT?

We love to hunt. Hunting is part of our upbringing and deeply entrenched into our value system. This is simply who we are as dedicated conservationists. Hunting matters to us, because we are passionate about it and it gives us a sense of belonging in the circle of life. Members of NAPHA are the true ambassadors who do care for the wildlife and their environment, irrespective of whether we will put a financial value to it or not.

Statistical data by a leading research company in Namibia found that 3% of tourist arrivals are indeed conservation hunters. Although they make up only a fraction of the entire market, they account for close to 20% of all the tourism revenue. Namibia’s tourism sector has the ability to provide an unparalleled nature and wildlife-centred experience without surrendering key sustainability initiatives [UNDP, 2020].

Yes, Africa, and especially we in Namibia, are heavily dependent on the international markets’ interest in our wildlife. We use the income derived from conservation hunting to finance our conservation efforts; livelihoods and much more is at stake without the foreign earnings. Sustainable hunting brings multiple solutions to counter the everincreasing human-wildlife conflicts encountered especially in rural areas. Some form of sanity prevailed when the UK, which is not a key market for Namibia, admitted that a possible import ban on trophies is not such a good idea – at least for the moment.

Other European countries, such as Germany, tried to follow suit in a similar manner by imposing a moratorium to market conservation hunts at Europe’s biggest hunting show in Dortmund. Luckily, such a move by the German Green Party was turned down during Dortmund’s City Council meeting. During the livestreaming of the discussion, we listened to the various arguments for and against the moratorium.

The views and arguments presented by the various politicians were characterised by the same problems. It is unfortunately an emotional debate by people who live detached from nature and far away from all our costs and benefits associated with our well-regulated and sustainable use concepts.

As a hunting community we continually evolve and we see an obligation to ensure that our actions are truly sustainable and not detrimental to the population at large. NAPHA is proud to say that

we have introduced new initiatives such as the age-related trophy measuring system, ensuring that hunting remains sustainable.

The establishment of our new NAPHA School of Conservation, where we educate and train aspiring hunting professionals, shows that we are optimistic and serious about our future. NAPHA does not operate in a void and is heavily dependent on our national and international partners. Without the active and generous support from various hunters and like-minded associations we would not be able to fund and host community outreach projects facilitated by our Hunters Support Education Committee.

We applaud our government for creating through the Ministry of Environment, Forestry & Tourism (MEFT) an enabling environment where we as hunting professionals can live our dream by allowing conservation hunting as an approved method to utilise our natural resources. Almost half of Namibia is under some form of conservation management and has a proud heritage of conservation which is recognised internationally.

All of us are happy that our Huntinamibia is back, now in a revitalised and new digital format. Let us use this new platform to market and display what Namibia and its hunting professionals have to offer. Let us remain staunch advocates for responsible, sustainable, and ethical conservation hunting in Namibia.

Safari greetings from the Land of the Brave.

Cramer NAPHA PresidentWhy hunting matters...

I practise conservation hunting because I believe it is the best way to ensure the future of wildlife for generations to come and, as we all know, hunting animals has a much smaller carbon footprint than domestic livestock or photo safaris. Sustainable hunting will only have a place in our world while there is a value to the animals. As they say 'the proof is in the pudding' and one only needs to look at the numbers of wildlife in Namibia today versus 30 years ago to find that proof.

- Hannes du PlessisBeyond the personal challenge and passion, hunting is the most natural way of land use in Namibia, to the benefit of many people who depend on it. The real wilderness is threatened by human growth and the need for food production. Hunting wild animals on free range land is the only way to balance food requirements, nature and conservation – that is why I hunt.

- Harm Woortmann

- Harm Woortmann

I love to hunt. Hunting is part of my upbringing and deeply entrenched into my value system. This is simply who I am, a dedicated conservationist. Hunting matters to me, because I am passionate about it and it gives me a sense of belonging in

the circle of life. Ethical hunters care for the wildlife and their environment, irrespective of whether we put a financial value to it or not.

- Axel CramerHunting matters because it goes far beyond meat provision or job creation: it is a school of life. Hunting allows you to take part in nature and understand basic principles of life and nature. Moreover, if practiced sustainably and ethically, hunting is the number one land use form that contributes to conservation of large tracts of the natural environment.

- Hagen DenkerSustainable and managed utilisation of ALL our natural resources is the only way whereby Africa will be able to keep and expand the natural habitat and all ecosystems that rely on that habitat for future generations. This includes selective hunting as a valuable and low-impact form of sustainable utilisation which provides income, employment and growth opportunities for the people of Africa

- Royston WrightHUNTING CONCESSIONS

- Namibia's conservation success story

The sustainable use of wildlife, especially trophy hunting, has played a critical role in the development of communal conservancies. Prior to 1998, there were only four hunting concessions operating on Namibia’s communal lands, with none of these concessions providing meaningful engagement with or benefits to resident communities. Today there are 46 trophy-hunting concessions operating on communal lands, with the conservancies being empowered as both the benefactor and custodian of these hunting concessions.

ParkNamib-Naukluft

Kwandu - J. Traut

Orupembe - Anton Esterheizen

Mayuni - J. Traut

≠Khoadi-//Hôas - Anton Esterheizen

/Audi - Jaco Oosthuizen

Uukolonkadhi Ruacana - L. van Zyl

Sesfontein - L. J. van Vuuren

George Mukoya - D. Swanepoel

Muduva Nyangana - D. Swanepoel

- King Nehale - H. van Heerden

- !Khoro !goreb - Jaco Oosthuizen

Otjimboyo - Nicolaas Nolte

Tsiseb - Kai-Uwe and Hagen Denker

- Sorris Sorris - Gerard Erasmus

Sanitatas - Anton Esterheizen

Sikunga - K. Stumpfe

Sobbe - K. Stumpfe

Brown Hyaena

Steenbok

Klipspringer Giraffe

Kudu

Springbok

Brown Hyaena

Steenbok

Klipspringer Giraffe

Kudu

Springbok

Status of different wildlife species in Namibia

Common name Scientific name Distribution status Conservation IUCN & CITES Notes on distribution

Cape Rock Hyrax Procavia capensis √ Southern African near endemic Secure Distributed across central and southern Namibia

Kaokoveld Rock Hyrax Procavia welwitchii √ Namibian near endemic Secure Kunene region of Namibia and into SW Angola Bush Hyrax Heterohyrax brucei √ Peripheral indigenous Secure Extreme NW in Kunene River valley African Bush Elephant Loxodonta africana √ Indigenous Vulnerable (CITES II) Historically occurred across all of Namibia except Namib sand sea

Aardvark Orycteropus afer No Indigenous Near Threatened Widespread across Namibia except for extreme west

Chacma Baboon Papio ursinus √ Indigenous Secure (CITES II) Widespread across Namibia except extreme west Vervet Monkey Chlorocebus pygerythrus No Indigenous Secure (CITES II) Confined to northeast and Orange River valley

African Wild Dog Canis pictus No Indigenous Endangered Historically occurred across all Namibia except for extreme west

Side-striped Jackal Canis adustus No Indigenous Secure Northeast Namibia Black-backed Jackal Canis mesomelas √ Southern African nearendemic Secure Widespread across Namibia Bat-eared Fox Otocyon megalotis No Southern African endemic Secure Widespread across Namibia

Cape Fox Vulpes chama No Southern African endemic Secure Widespread across Namibia except for extreme west and northeast Ratel Mellivora capensis No Indigenous Secure Throughout Namibia except for extreme west Lion Panthera leo √ Indigenous Vulnerable (CITES II) Historically occurred across all of Namibia Leopard Panthera pardus √ Indigenous Near Threatened (CITES I) Widespread across Namibia except extreme western Namib sand sea Serval Leptailurus serval No Indigenous Secure (CITES II) Historically across northern and eastern Namibia Caracal Caracal caracal √ Indigenous Secure (CITES II) Widespread across all Namibia Cheetah Acinonyx jubatus √ Indigenous Vulnerable (CITES I) Widespread across Namibia except for far west African Wildcat Felis sylvestris No Indigenous Secure (CITES II) Throughout Namibia

Black-footed Cat Felis nigripes No Southern African endemic Vulnerable (CITES I) Across Namibia except for far west, northwest and northeast

Brown Hyaena Hyaena brunnea x Southern African endemic Near Threatened Across all Namibia

Spotted Hyaena Crocuta crocuta x Indigenous Secure Historically across Namibia except for extreme west Aardwolf Proteles cristata No Southern African nearendemic Secure Across Namibia except for extreme west Plains / Burchell’s Zebra Equus quagga burchelli √ Southern African endemic Near Threatened Across Namibia except for extreme west and northeast Plains / Chapman’s Zebra Equus quagga chapmani √ Indigenous Endangered Northeast Namibia Hartmann’s Mountain Zebra Equua zebra hartmanni √ Namibian endemic Vulnerable (CITES II) Western escarpment and central plateau (mountainous rocky terrain) Black Rhinoceros Diceros bicornis bicornis √ Indigenous Vulnerable (CITES I) Historically across Namibia except for extreme west

White Rhinoceros Ceratotherium simum simum √ Southern African nearendemic Near Threatened (CITES I)

Historic range across Namibia above about the 250 mm rainfall isohyet Bushpig Potamochoerus larvatus √ Indigenous Secure Northeast Namibia

Desert / Cape Warthog Phacochoerus aethiopicus aethiopicus

No Southern African endemic Extinct Extreme southern Namibia – Orange and Fish River valleys

Common Warthog Phacochoerus africanus √ Indigenous Secure Widespread across Namibia except for far west and south

Common Hippopotamus Hippopotamus amphibius √ Indigenous Vulnerable (CITES II) Historically occurred in all perennial river systems in Namibia Giraffe (Angolan Giraffe) Giraffa camelopardalis angolensis √ Indigenous Vulnerable Historically widespread across all Namibia except for extreme west

African Savanna Buffalo Syncerus caffer √ Indigenous Secure Historically widespread except for far west and southern Kalahari Nyala Tragelaphus angasi √ Exotic Secure Occurred naturally in northern KwaZulu-Natal and Kruger NP Lowveld

Greater Kudu Tragelaphus strepsiceros √ Indigenous Secure Widespread across Namibia except for extreme west Bushbuck Tragelaphus scriptus √ Indigenous Secure Northeast Namibia Sitatunga Tragelaphus spekii √ Indigenous Secure Reedbeds in north-eastern perennial rivers

Common Eland Taurotragus oryx √ Indigenous Secure Historically throughout Namibia except for far west

Common / Grey Duiker Sylvicapra grimmia √ Indigenous Secure Throughout Namibia except in far west

Sharpe’s Grysbok Raphicerus sharpei √ Peripheral indigenous Secure Extreme eastern Zambezi Region Steenbok Raphicerus campestris √ Southern African nearendemic Secure Throughout Namibia except in extreme west

Damara Dik-dik Madoqua kirkii damarensis √ Namibian nearendemic Secure

Central, north-central and north-western Namibia

Springbok Antidorcas marsupialis √ Southern African endemic Secure Throughout Namibia except in north-eastern woodlands

Oribi Ourebia ourebi √ Peripheral indigenous Secure Eastern Zambezi Region Rhebok Pelea capreolus No Peripheral indigenous Secure Huns Mountains in Namibia’s extreme south Southern Reedbuck Redunca arundinum √ Indigenous Secure Perennial rivers in north-eastern Namibia Puku Kobus vardoni √ Peripheral indigenous Near Threatened Extreme eastern Zambezi Region – Chobe floodplains

Southern Lechwe Kobus leche √ Indigenous Near Threatened (CITES II) River systems in northeast Namibia

Waterbuck Kobus ellipsiprymnus √ Indigenous Secure River systems in northeast Namibia Klipspringer Oreotragus oreotragus √ Indigenous Secure Hilly, rocky & mountainous areas of southern, central and north-western Namibia

Common Impala Aepyceros melampus melampus √ Indigenous Secure Historically across central-eastern and northeastern Namibia

Black-faced Impala Aepyceros melampus petersi √ Namibian nearendemic Vulnerable Northwest and southwards to northern central plateau

Bontebok Damaliscus pygargus pygargus √ Exotic Vulnerable (CITES II) Occurred naturally only in the Western Cape coastal fynbos, RSA Blesbok Damaliscus pygargus phillipsi √ Exotic Secure Occurred naturally only in South Africa’s grassland Highveld & Karoo Tsessebe Damaliscus lunatus √ Indigenous Secure Northeast Namibia Red Hartebeest Alcelaphus buselaphus caama √ Southern African endemic Secure Kalahari and thornveld savanna ecosystems in Namibia

Blue Wildebeest Connochaetes taurinus √ Indigenous Secure Historically widespread, except in the west & extreme south Black Wildebeest Connochaetes gnou √ Exotic Secure Occurred naturally only in South Africa’s grassland Highveld & Karoo

Roan Antelope Hippotragus equinus √ Indigenous Secure North-eastern woodlands of Namibia Sable Antelope Hippotragus niger √ Indigenous Secure North-eastern woodlands of Namibia Southern Oryx Oryx gazella √ Southern African endemic Secure Throughout Namibia, except for Zambezi region

DEFINITIONS

Indigenous – where the species occurs naturally without any human intervention. This refers to the species’ actual distribution, not the countries where it occurs. For example, Waterbuck and Lechwe are indigenous to the wetland systems of NE Namibia – they are not indigenous to the whole of Namibia. Similarly, Hartmann’s Mountain Zebra are indigenous to the western escarpment and central plateau of Namibia, but not to the Kalahari.

Endemic – where an indigenous species has a naturally restricted range. Thus, a Namibian endemic means that the species occurs naturally only in Namibia. We therefore have a special responsibility for its conservation. A Southern African endemic means that the natural global distribution of a species is confined to south of the Kunene and Zambezi rivers. Near-endemic – where about 80% of the natural range of a species is

confined to the specified area. For example, the Damara Dik-dik is a nearendemic to Namibia, with just a small part of its range extending into southwest Angola.

Exotic – where a species originates from another part of the world and has never occurred naturally in Namibia, e.g. Nyala, Blesbok, Black Wildebeest.

Peripheral – where a species just enters the very edge of Namibia, with most of its distribution occurring elsewhere, e.g. Puku, with a tiny population on the Chobe floodplains but most of its population in Zambia.

Conservation Status – IUCN global conservation assessment (see www.iucnredlist.org - not the Namibian status); and the CITES Appendix status.

An African’s conversation about

the CONVERSION OF AFRICAN CONSERVATION

Basically the debate is about how we are supposed to protect our wildlife from destruction in the face of the relentless encroachment of mankind. And that is where the first problem comes in – all of those screaming to protect OUR wildlife actually mean certain animals – the big ones and the furry ones. They have the flagship species in mind: Elephant, rhino, lion, leopard, gorilla, giraffe, and zebra – the animals commonly associated with the general picture of “Africa”. Very few people are concerned about the bontebok or the grey rhebok, or even know what they are. No-one really cares to mention the small, the ugly and the less cuddly ones which just as much form part of wildlife. They are all catalysts in the natural chain of ecology and biodiversity, which also includes the various plants. This biodiversity is needed to support all animal species, not only those few that everyone wants to protect.

Closely linked to this is the question of balance of the ecosystem. Where land is utilised, carrying capacity plays a significant role in the balance of nature. As we all know, too much of a thing is never a good thing. As an example, too many antelope will eat all the available food and none will be left for the dry season. An over-abundance of prey species also promotes a better stimulus and survival of predator populations which have a faster reproductive cycle. Something to avoid is a total population crash when too many predators and lack of grazing impact prey populations simultaneously.

Carrying capacity is the maximum number of units that can be maintained sustainably (i.e. balanced) in a given area utilising a natural resource within a given timeframe. Logically, it would make sense to try to maintain a population at or just below the carrying capacity.

That brings us to the question of “maintaining” population figures. We want wildlife populations to grow and be protected, but the human population continues to grow as well. As a result, wildlife habitats are shrinking at an alarming rate. In fact, Africa’s human population is growing so fast that the ever-increasing demand for land is the biggest item on all African government’s agendas. More land for human use will be to the detriment of wildlife – that is a given.

“Animals are safe in game reserves and national parks”, the armchair conservationists are screaming. Well, if it comes to that we have failed! Little islands of conservation areas would decrease potential genetic signature dispersal, and it also leads to a concentration of the prime poaching species.

Wildlife management is about maintenance of the land, water points and water systems, erosion control, anti-poaching, accessconstruction, fences, invader plant control and wildlife population control. It is what game rangers and park wardens, land owners, farmers, ecologists, pastoralists, conservancies and concession holders do all the time: Putting their knowledge about ecosystems, behavioural patterns, growth cycles of plants and animals, and interactions between all these, into an overall plan that is constantly adjusted to account for changing circumstances and needs in a given area. Larger areas need less direct management than smaller ones, as they tend to selfregulate to a degree.

Ideally, one would want an area to be large and left alone, but unfortunately such areas are getting less and smaller, thus more direct human input is required. Wildlife population management seems to be the hottest topic these days as it involves the removal of

excess animals from an area.The cry from the armchair conservationists will be that if a population starts to naturally adjust to the carrying capacity, why manage it? The answer is that firstly the carrying capacity is constantly changing with the weather conditions. Secondly, management is needed to prevent human-wildlife conflict (HWC) and to prevent animals dying from starvation, over-predation, disease breakout and other factors that lead to drastic population declines. All these criteria would not be such a problem in large areas, but large areas actually do not exist anymore. The narrowing corridors and open (humanpopulated) land between the “wildlife islands” are the cause for HWC, one of the biggest concerns of our conservation era. People who live in areas bordering parks and game reserves have to deal with dangerous wild animals on a daily basis. This creates resentment, the exact opposite of what we are trying to achieve. Some communities want ALL elephants removed because they are tired of having their fields – an entire year’s food supply – destroyed overnight. These communities in remote parts of the country are ultimately responsible for the survival of wild animals outside parks and the preservation of the supporting habitat. They have to benefit from the wildlife otherwise we are losing.

Too many elephants in an area eventually destroy their habitat by over-utilisation. Such areas (usually along watercourses) are devoid of all intermediate trees and shrubs. Only larger (somewhat mangled) trees remain. The full extent of this becomes more visible from the air.

This is where population management comes in, the removal of animals from an overpopulated area to maintain carrying capacity. The methods are hunting (for meat or trophy), culling, or capture. All of them

We know that the world is getting smaller thanks to the internet and various social media platforms and apps, as well as long-haul air travel which takes you to another continent overnight. Unfortunately, that level of connectivity creates a problem for the public debate on African conservation. The same people keep attacking each other with the same old arguments. Byron Hart

are regulated by the wildlife authorities through some type of permit system, that creates control and statistics, based on the management plan for that area. By contrast, poaching is indiscriminate and benefits only the poacher.

Culling involves the removal of a certain number of animals irrespective of gender or age, so that the dynamic of the population is not skewed by human bias. The aim is to reduce the numbers as quickly as possible with minimal impact on the remainder of the population. It is usually done at night by a team of expert shooters and butchering teams. The advantages of culling are the rapid reduction of numbers in a very short period of time, and the meat is very hygienic as it is processed quickly. Also, the remaining population is usually unaware of this action.

Meat hunting mostly takes place during daylight, and is generally more biased as to which animal is harvested. The hunter will take one or two animals, of a specific gender or age group, for his own meat supply. The reduction impact is a lot slower than that of culling, but meat hunting can be implemented continuously over an entire season.

Trophy hunting attracts the most criticism by far. It is generally seen as a “blood sport” practised by the wealthy to collect animal heads. Yes, that may be the case, and it may be the reason why hunters travel to distant places (supporting local economies). Very few people, however, are aware of the conservation benefit of this method: the population impact is the lowest but it generates the biggest income. Yes, good money is made – by entire rural communities who provide the services for trophy hunting in remote areas. The economic factor is so remarkable that people are keen on creating more habitat for wild animals. Investors are prepared to buy land, usually marginal livestock land, and convert it back to a habitat suitable for game herds. This gives the local people a sense of ownership because they are actually helping the wildlife populations to flourish, with the incentive to be able to ‘harvest’ a select number per year. No one will over-harvest and deliberately destroy their source of income, and game populations in southern Africa have therefore increased drastically even though a controlled number of animals are hunted every year.

Game capture is a fast method for the live removal of animals. The most common way is to chase them with vehicles or helicopters

into a funnel-shaped chute or into hanging nets and then load them onto a truck. This generally causes quite a bit of area disturbance, albeit short-lived. There are also various methods of passive capture, such as a trap at a water hole or salt lick.

People who do not [want to] understand the need to keep animal numbers in check will ask: “Can’t we move them to another place?” They usually mean the flagship species, mentioned above. The question is – move them where? Where should we move lions? Or elephants? To areas that already have them in excess anyway? This inevitably brings us back to the issue of ”available land”.

Let us look at elephants for a moment. Every available piece of land that can support a “viable” population of elephants has already got them [and too many]. Land that does not have elephants either cannot support them, cannot be protected sufficiently against poaching, or the human communities living in and around that area do not want them because they are a nuisance to their livelihoods. We are talking about thousands of elephants that some areas have too many of. Sub-Saharan Africa still has over 300,000 [and growing,

naturally] elephants, but with nowhere for them to go. Should we put them into Central Park in New York? How long would it be before NY residents start complaining? Yet it is people like those living around Central Park, the city dwellers, the “good to do community”, who are quick to criticise the management of elephant numbers in Africa – but few come up with viable solutions.

Imagine putting 20 lions in Central Park… Who wants more lions? Definitely not the communities in rural Africa. Many of them kill the lions themselves, either by shooting or by poisoning (horrible), because their governments cannot solve HWC problems within acceptable timeframes. In fact, besides the private game reserves that already have the big cats for their tourists, the only people who want lions on their doorstep are those who live in cities or on another continent.

How do we create habitat for wildlife when available land is decreasing? By creating a value for these animals so that the people who live with them will benefit – in the form of financial compensation, jobs from hunting and photo tourism or the meat of hunted animals.

The crude way of putting this is: If it pays it stays.

You have probably heard many hunters, like myself, say that hunting is conservation and that sustainable utilisation (SU) is the only way forward. It is not, but right now it is the most advanced conservation model that we have for the protection of habitat in rural areas with marginal communities.

We utilise our [natural & mining] resources to exist, yet we criticise hunting, the one activity which is a management tool for a resource that is 100% renewable in an expedient time-frame, produces protein, income, jobs and the incentive to coexist. Without this coexistence, wildlife numbers will be decimated (poached) by the increasing human populations through their natural urge to live, and land will be cleared to make room for agriculture. It is this uncontrolled utilisation that will ensure the extinction of species. Controlled sustainable utilisation, on the other hand, contributes to the well-being of local communities in exchange for them “being tolerant” of having to live with wild animals at their doorstep every day.

"

How do we create habitat for wildlife when available land is decreasing? By creating a value for these animals so that the people who live with them will benefit..."

Last minute Leopard

Just three more days on safari. Only three days to get a leopard. And our difficulties already started with the hunt for bait. Chris Balke

Despite the alert trackers and despite my experienced PH, we could not find a suitable antelope. Most likely owing to the fact that the predator population in this area was comparatively dense. During our stalk through the thick bush in the late morning, sheer luck presented us with a gemsbok cow, but leading a calf. She sensed us before we saw her and broke away into cover with her calf. We could not follow in a straight line, because the thick and thorny hell was simply impenetrable. Instead, we continued our stalk on an elephant track. All of a

sudden we heard the wailing of an antelope. Immediately my hunting guide commanded: “Quick, we have to get there. Hurry!” On the double we rushed into the direction from where we had heard the wailing. But since it had stopped after only seconds, we followed our instinct more than our ears. Now we heard the call of the cow for her calf. This gave us a good idea of the position of the cow. We approached the cow quickly and quietly until we had her in sight. It stood quartering away from us, continuously calling in the same direction. “A leopard must have taken the calf.

Shoot the cow when it is standing broadside,” my PH whispered. Moments later a shot rang out of the .375 H&H cal. Blaser R93.

After the shot we waited quietly for a few minutes. “Maybe the leopard shows up,” the PH noted. But it remained invisible. We attended the cow, called the vehicle in to cart it away. Then we searched for the calf, since the fresh kill would make the ideal bait for our purpose. We finally found it, killed with a well-placed throat bite. The trackers pulled it some 5 yards out of the scrubs, into the open,

tied it to a trunk and left it on the ground. In a blink a small blind was erected, approximately 50 yards from the calf. From noon onwards we sat in the blind, waiting. I had little hope. The gemsbok cow had been standing close to the leopard. It means, that when we shot her, the bullet had been whistling around the leopard’s ears. And then all the commotion when we attended the cow, the human voices, the pick-up coming in and leaving. Would the leopard really dare to come back? Our waiting was unsuccessful and I mentioned that I did not believe in a true chance at this spot. But, my hunting guide said: “No, the ruckus does not really affect the leopard. And since there are only few antelope around he will not give up his quarry. The calf was an easy prey, and we‘ve actually driven it into its fang. I‘m sure the cat was close by tonight, but has sensed us somehow. Maybe we‘ll get it tomorrow.”

New day, new tactics. We checked the bait which showed clearly that the leopard had been on the bait indeed. Since my rifle was scoped with a 1-4x20 my PH suggested hanging the bait on the tree. This would improve my chances in vanishing light. In addition we erected a second blind further to the left and a bit closer to the bait. At noon, this second blind was manned with two trackers, while we would again sit in the first blind. Just before, the trackers left their blind, talking loudly, while we remained silent. But again, the predator did not show up. “You‘re just too noisy, Chris! The leopard is there, but it hears you fizzling all the time!”, my PH complained. I couldn‘t believe it! For hours I had endured lying absolutely motionless next to him on the ground. In my opinion the wind was not steady and had given us away.

My last day in Africa had come, and again the strategy had changed. A third blind was erected, this time more to the right, but also just 40 yards from the blind. The three blinds forming a sort of triangle, with “our” blind being in the middle but furthest away from the bait. Both the second and the third blind were manned by the trackers, while we occupied the center blind. As on the previous days, we started around noon and the trackers left before dusk, this time picking-up each other, speaking loudly and making a lot of noise. They also approached our blind, pretending that we had also left. They then

Below are some of the conditions applicable to a predator trophy hunting permit

• A trophy hunter, trophy hunting guide and trophy hunting operator must read and acknowledge and sign the predator trophy hunting permit conditions before the hunt commences. After a successful hunt all parties involved have to sign the reversed side of the permit.

• The permit must be in the physical possession of the trophy hunt ing guide while the predator is being hunted and is only valid for a period and the hunting areas specified on it.

• Only free roaming, self-sustaining and adult predators may be hunted as trophies. In the case of leopard, only males may be trophy hunted.

• Predator trophy hunting may not take place during the period between 30 minutes after sunset in any day and 30 minutes before sunrise the following day. Artificial light is prohibited.

• Canned hunting in any form is illegal

• After the hunt 4 photos (as specified in the gazette) have to be taken and submitted.

disappeared in the direction of the vehicle, departing with a lot of revving up the engine. What a show, I said to myself. Who expects the leopard to buy that? A really unbelievable hunting tactic.

Dusk was approaching when suddenly I felt my PH prodding my leg - almost gently for the circumstances, whispering: “The leopard is up the tree.” I could now see its silhouette, barely contrasting against the sky. I peeped through the scope and could see little, close to nothing. I said: “I can barely see it.” He replied, “I see it clearly, with the bare eye!” Unbelievable, I thought, and tried again to pick up the target. “I don‘t get a clear view!” “Try anyway,” he replied. And I did. The shot rang out and nothing happened. After a few seconds I heard my PH whisper, “It is still sitting there.” As quietly as possible I chambered a new round, keeping my eyes on the bait and the trunk. “Now it is lying flat on the branch and looking at us. It knows exactly where we are sitting.” I peeped through the scope again, raising the reticle a bit above the trunk and shot again. This time a deep thud followed. My PH laughed out loud in warm cordiality like I have never heard him laugh before. “That looks good! It came down with its rear legs first. That is a very good sign.” After waiting about ten minutes, we approached a mighty and heavy tomcat. According to the PH, it was the second biggest leopard he has ever taken in that area. For me, it was a dream of a lifetime come true.

THE WARRIOR of solitude

For outdoorsmen who have not yet hunted in Namibia, you cannot begin to explain the vastness or sheer beauty of what the ancient desert has in stall for you. Text Sigurd Hess

Carl had booked a desert hunt in the Tsiseb Conservancy. High on his agenda was a gemsbok –the ‘warrior of solitude’. Gemsbok are notorious for their toughness and are known to absorb a lot of lead if the hunter’s first bullet is not placed well. This, Carl experienced firsthand.

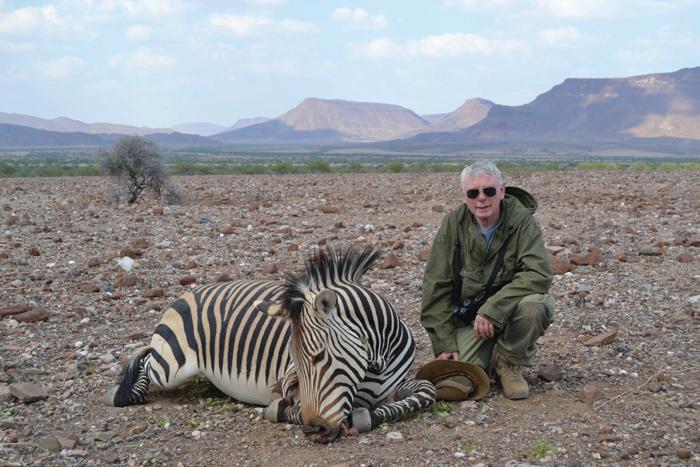

On the seventh day of an eight-day hunt we were making headway up a hill, where the rock formations resembled the scales on the back of a large dragon. We had seen several gemsbok in the preceding days, but they were either cows or groups of young animals. In these days, with hard work and a bit of luck thrown in, Carl had managed

to bag a Hartmann´s zebra and an old, decent-sized springbok ram. But since then we have not been lucky. Our prized quarry had evaded us. Then, as we were scanning the surroundings, seemingly from nowhere, a gemsbok appeared on top of one of the parallel running ridges. It was about noon, and no sooner had we spotted him than

On the seventh day of an eight-day hunt we were making headway up a hill, where the rock formations resembled the scales on the back of a large dragon. As we were scanning the surroundings, seemingly from nowhere, a gemsbok appeared on top of one of the parallel running ridges.

he disappeared again over the ridge. From where we were, we estimated the distance to the hill as roughly three kilometres.

My immediate concern was that the border of the Dorob National Park was a mere seven to ten kilometres on the other side of the ridge, the same direction in which the gemsbok had disappeared. Here we were, hunting in a concession area encompassing close to one million hectares, and it still seemed too small! I said to Carl: “If ever we had a chance, this is it!”

Being about ten kilometres from the vehicle, with our water supply running low, it was

now or never. “I cannot even tell you if it´s a bull, nor if he is old enough! But it’s a solitary animal, which is always a good sign.” All Carl did was shrug his shoulders and reply in his Texan drawl: “Well, let´s go!”

The urgency, anticipation and excitement turned us into walking machines. Elias and Eric, the two trackers, Carl and myself covered the distance to where we had seen the blur of the gemsbok in record time. You know that feeling of having bags of cotton wool in your mouth, your pulse rate soaring? A very dry north-easterly wind was howling, making it even harder to walk, blowing straight at us, causing sand to sting our legs, arms and faces.

Before we reached the top of the ridge, we soothed our dry throats with the by-now warm water from our bottles. Tensely we crept up onto the ridge, scanning in all directions, down into the gullies and beyond. Alas! Nothing in sight. “Well! Where the heck is that gemsbok?” Carl barked in agitation. Moments after finishing his sentence, and having similar thoughts in my mind, we saw the typical grey colour of the gemsbok ambling up a ridge about a kilometre away. This time we could easily identify the animal as a large, heavy-bodied bull with long horns. He had not seen us. We waited until he disappeared over the ridge and then moved

quickly, half running, towards the next ridge. I urged Carl on to give everything for this opportunity to bag the warrior. He stayed on my heels. Just before the ridge we paused to catch our breath and for Carl to load his 30-06. Ever so cautiously, in single file, we crawled up to look over the edge.

And there, 160 metres from us on a little ridge, stood our warrior of solitude staring down into a large plain below, his tail blown sideways by the wind.

We tried to get ourselves ready, lying rather uncomfortably on the black rocks, using the rucksack as a rest. By now it was two hours past midday and the rocks we were lying on were hot enough for frying an egg. “Carl, he is a good bull, you can take him! But allow for the wind,” I whispered.

The report of the rifle came a lot faster than I had wanted it to, and the reaction of the gemsbok, kicking out to the back, did not bode well, as this was often the telltale sign of a shot that had struck too far back. Carl immediately cycled a new round into the chamber, but before he could squeeze off another shot, the bull had sped down into the valley out of our sight. We jumped up and raced ahead, throwing ourselves onto the ground again to take aim as the gemsbok increased the distance between itself and us. Carl aimed and fired – nothing! He tried again, and the bull staggered, ran another 40 metres, and then sat down on his haunches. “Fill your magazine!” We slowly approached the bull and Carl delivered the coup de grâce.

After reliving the rollercoaster of emotions over and over again, we sat down next to the gemsbok, quite exhausted, but relieved and happy. Days like these make us proud to be hunters and grateful to be able to hunt the way we do in areas such as this.

But that is never the end of a hunt. We manoeuvred the vehicle as close as possible and only once all the meat was on the truck, were we ready to head for camp, just as the sun was setting, ending a sublime week of hunting and leaving us with fond memories.

DESERT MAGIC

The vast gravel plains of Namibia's western desert fringes are strewn with large granite boulders etched against a backdrop of mountain ranges and changing colours as the day waxes and wanes. Ephemeral rivers that have cut through rolling hills for millions of years feed springs that still yield water, sometimes for the duration of regular droughts. These green oases, maintained by fog generated by the Atlantic Ocean and intermittent rainfall, form the nuclei of the astonishingly abundant life flourishing in this arid land. All flora and fauna that have subsisted in this barren desert for millions of years have adapted to not only survive but also to thrive here. Natural selection, bizarre adaptations and evolution are but some factors that make life possible in this extraordinary region.

Being fortunate to hunt in these extensive desert areas is a privilege in its own right. There is no camera – whether video or photographic – that can ever capture the extent of what the Namib offers. Having walked the desert for kilometres on end pursuing a solitary old springbok in the heat of the day, the heat shimmer and glare so severe that it is close to impossible to judge the trophy size through your binoculars, humbles both me and my clients, who come from all walks of life. The experience underlines the fact that we hunters, with rifle and binoculars in hand, are here for only a nanosecond compared to how long the desert has been around, and for how long it will still be here. More often than not, after a long day of hunting the desert, one can sense that the desert is most certainly alive. I would go as far as saying that you sense that the desert harbours many secrets, if not the very cradle of life.

What an awesome sight to see a solitary gemsbok bull wandering across a gravel plain in the typical regal gait that only these antelope have. He gives the impression that the heat does not affect him in the least. His occasional swishing of the tail is a sign of pure contentment. It seems he knows exactly where he is going. He seldom veers off course or changes speed. He rarely stops to scan the surroundings, his head held high. To me this makes him the warrior of solitude. He seems to be in tune with the desert and the loneliness.

wily old roan ON THE SPOOR OF A

It is late November, the Christmas beetles kick up a deafening racket with their high-pitched screeching, the air is dry, the parched earth is longing for rain. The deciduous trees use their last resources to grow their foliage. In front of us lies the track of a wily old roan antelope. We are hunting this elusive antelope in Bushmanland and find the tracks of the solitary bull on the white sand of the road between Tsumkwe and the border post just after sunrise. Sigurd Hess

“These tracks are probably from before sunrise or late last night”, I say to Jürgen. The excitement is tangible and we pack our kit and hide the vehicle some distance from the road in dense shrub. Tracks cross the road southward and back across the road to the north, then west. Tracks of a herd mingle with the bull's spoor. Finally the jigsaw puzzle is solved and off we go in search of the roan bull. As the sun travels to the zenith, its glare makes tracking ever more difficult. The two San trackers Robert and !Tuxa and my tracker Elias follow

the spoor with perseverance for hours on end. The bull is in walking mode and it dawns on us that he will not stop anytime soon to lie low. He hardly pauses to rest or feed, which makes me nervous. As we haven’t bumped into him yet I assure Jürgen that it is still a level playing field and not all the odds are stacked against us. We compose ourselves and push on. But our breaks are getting longer and more frequent, necessitated by lapses in concentration, thirst and heat. Time flies and soon it is close to 2 pm. The north-easterly wind prevailing in the morning has subsided

and soft swirls are now coming from all directions. This is worrying as we climb onto a dune with a dense Terminalia pruniodes thicket. The rustling leaves are blown from left to right, front to back. A carpet of dry leaves makes it impossible to move as silently as we should.

Suddenly Robert squats down and vigorously points forward. The fatigue, thirst and frustration vanish in a split second and are replaced by excitement, a racing pulse, hunger and the urge to bag

the desired animal. The bull has bedded down at an angle 60 yards away. I grab Jürgen by the arm because all we need to do now is crawl five yards to a termite mound and reward our hard work with a spectacular trophy animal. Ever so cautiously we peep over the termite mound. The place where the roan was lying is empty, as if he had never been there.

“The darn wind spoilt it,” I dejectedly say to Jürgen. All hopes crushed, the pulse returns to normal. The thirst and the sense of fatigue and desolation returns. Questions crowd your mind and block out everything else. Were we too slow? Why didn’t it work out? Was it just not meant to be? Just bad luck?

Our water supply is finished but we decide to try once more after giving the bull and ourselves an hour to relax. While we were lying there, the time ticks by slowly. The afternoon wind is hot as if out of a furnace, a reminder of the harsh conditions with which animals have to cope on a daily basis season after season. As a hunter you want your quarry and the hope,

determination and willpower return in tiny increments. Giving up is not an option.

After the painful hour has passed we get up rather groggily, discuss how to continue and decide that we will try only once more because our energy levels are low and no water is left in the canteens. With renewed determination we pick up the track where the roan thumbed his nose at us. Silence and concentration must reign supreme. After just 1000 yards all hell breaks loose and our roan, which had calmed and lain down again not far from us, jumps up and runs through a recently burnt area to stop and face us at about 175 yards. Instinctively Jürgen is on the sticks and finds his aim on the roan still facing us. A couple of seconds go by and as the bull turns to run, the rapport of the 375 H&H shatters the silence. The bullet finds its mark on the shoulder and with his roan “death squeak” the bull goes down after a few steps.

Walking up to the bull, feelings of elation, sadness, joy, humility, calmness, satisfaction and empathy overcome you as a true hunter.

This could be you...

Dirk de Bod Safaris Namibia is one of Namibia’s select hunting destinations, boasting over 48 500 acres of private game reserves with 31 different species available.

Dirk de Bod Safaris Namibia is one of Namibia’s select hunting destinations, boasting over 48 500 acres of private game reserves with 31 different species available.

MAKADI SAFARIS

CARRYING CONSERVATION: communities

I am not a hunter, by any stretch of the imagination. But I am Namibian. To me, being Namibian inherently means a deep-seated love and respect for our wildlife, landscapes and cultures. Sometimes this love and respect is translated into understanding, advocacy and practise. Other times we do not understand and subsequently refrain from advocating or practising, yet the love and respect remain. You do not have to be a practising hunter to understand and advocate for it. Because being Namibian, loving and respecting our wildlife, landscapes and cultures, goes hand in hand with understanding the importance of hunting and advocating for its continued contribution to what makes this country so phenomenal. Charene Labuschagne

On a recent visit to the northeast, particularly the Nyae Nyae Conservancy, I was exposed to the tangible impact that Namibia’s Community Based Natural Resource Management (CBNRM) has on communities. Nyae Nyae is one of 86 conservancies nationwide that empowers rural people, improves their livelihoods and conserves wildlife and the environment. The San people who reside in Nyae Nyae are a remarkable example of the native skills and knowledge of the bushveld that contribute to CBNRM’s roaring success. They know their land better than anyone, which is why it is pointless for outsiders, particularly people from industrial urbanised societies, to tell us how to conserve our corner of Africa.

The creation of communal conservancy hunting concessions has assisted in making Namibia one of the most desired hunting destinations in Africa. The big five (buffalo, elephant, leopard, lion and rhino) as well as a diverse mix of plains game freely roam on the conservancy ground, making for an attractive hunt. There are 45 trophy-hunting concessions operating on communal land, with conservancy communities directly benefiting from the sector through meat (protein) supply, job creation and monetary compensation used to construct infrastructure. But to fully understand why hunting really matters to communities, it is integral to grasp the reality of what said communities would look like in the absence of hunting concessions.

In the late 1700s when the first western explorers, hunters and traders entered what is now Namibia, our national wildlife population was probably in the range of 8-10 million animals. The centuries that followed spelled a massive decline in wildlife populations. Uncontrolled and wasteful hunting, veterinary policies and fencing as well as modern-day farmers regarding wildlife as useless and competing with their domestic stock plagued the animal population. A steep decline in wildlife numbers finally yielded below 1 million in the 1960s. Wildlife was of little value to the layman as they could not derive any benefits from “state-owned” wildlife. The

animals’ imperative role in a larger-thanlife ecosystem was yet to be understood, or quite frankly cared for.

direct family members and the broader community members. Their livelihoods are dependent on hunting concessions.

Other than the severe impact that the banning of conservation hunting would have on rural communities, wildlife would also bear the brunt. In the absence of income generated from trophy-hunting concessions in conservancies, these communities would seek money elsewhere – the most dreaded of which is from poaching. It is safe to say that this inevitable outcome, if hunting in Namibia were to end, is more destructive to animal rights and conservation agendas than legal, ethical hunting of indigenous animals within sustainably managed populations could ever be.

Only when conditional rights over consumptive and non-consumptive use of wildlife was introduced in the 1960s and 1990s did the attitudes of landowners and custodians change drastically. This new policy meant that wildlife finally had value to freehold and communal farmers as they could benefit financially from trophy and sport hunting, meat production, live sales of surplus animals as well as tourism. As the sector developed, farmers discovered that in our arid, sub-humid landscape wildlife is a much more lucrative, competitive form of land use than conventional farming. Subsequently, stock animals declined and wildlife numbers increased because freehold and communal landowners began seeing the value in wildlife from a broader perspective of collateral habitat protection and biodiversity conservation.

If ever this value rightfully assigned to our wildlife were to perish, there would be over 700 game guards and resource monitors left unemployed. If conservation hunting were to be put to a stop, as in Botswana, over 100 full-time employees would be jobless. Over 1000 conservancy employees would be forced to pursue alternative incomegenerating jobs, of which there are very few in rural areas. These may seem like marginal numbers, yet the income of these rangers and employees directly uplifts both

It has become a rather hot topic amongst global animal rights activists, and some elitist Namibian tourism operators, that hunting is contradictory to conservation. This could not be further from the truth. Hunting and conservation are engaged in a delicate dance – one could not exist without the other. The greater the benefits that freehold and communal landowners can derive from wildlife, the more secure it is as a form of land use and the more land is under conservation management.

What baffles me most about the arguments of people opposed to hunting is that these individuals, often from abroad, could never imagine themselves – let alone tolerate –living in such close proximity to wildlife. From an apartment in a high rise, or an air-conditioned conference room knee-jerk judgments and decisions are made by people who have very little insight into the reality on the ground. The reality is that hunting concessions in conservancies are a matter of people’s livelihoods. When and how will the voices of those most impacted by – and impacting wildlife – be heard in the context of international conservation discourse?

more information you can read The State of Community Conservation in Namibia here: www.communityconservationnamibia.com

For

Other than the severe impact that the banning of conservation hunting would have on rural communities, wildlife would also bear the brunt."

Give a dog a helicopter

Each year, NAPHA selects a Conservationist of the Year. This highly honoured and recognised title is awarded to a person, group or institution that has accomplished significant achievements in the conservation of Namibia’s habitats and wildlife. At its AGM in December 2021, NAPHA announced the latest recipient of the award: the Ministry of Environment, Forestry and Tourism’s K9 unit. Based at the Waterberg Law Enforcement Training Centre, but deployed all over the country, MEFT’s highly trained dog unit has become an extraordinary addition to its toolkit in fighting, and preventing, wildlife crime in Namibia. Namibian wildlife vet and pilot, Conrad Brain, and the Ministry’s own Manie Le Roux, who heads the unit, give us a glimpse into what it takes to utilise this special group of “Conservationists.”

The MEFT K9 unit recently won top accolades from NAPHA and this is only the beginning. The ability and capacity of dogs in all fields of substance detection, ballistics, explosives, wildlife products, narcotics and even cell phone recognition is astounding, but it still goes beyond that. Dogs are also highly effective in human disease detection such as COVID-19, most cancers, diabetes, epilepsy and even as far as identifying pre-suicidal people.

Namibia can pride itself in being an African leader in many fields of dog training, and in some cases, the first and only African country to embrace and utilise a resource that is making maximum use of a latent canine talent present in everyday life. It makes sense that well-trained dogs have to be extremely mobile and the unit needs to have the capacity to be deployed at short notice anywhere from Epupa to Lüderitz.

Just to access the locations – villages, schools, informal settlements, fishing camps and even urban areas – in many cases requires time, logistical planning and inevitably long distances of travel. The extreme gradients of topographical, climatic and even biome changes in Namibia make it a difficult and challenging environment to work in. However, with our trained canine resources on hand it is time to take flight – literally.

For most humans, the first time they ever set foot in a light aircraft is an utterly exciting, terrifying, tantalizing event that comes along with a series of sensory perceptions that they could never have predicted. The sounds and smells, the unfamiliar cabin, the radio talk that they do not comprehend, and then finally the lift-off into a space of supportive atmosphere, produces varied responses. Joy, terror, amazement, gastric disturbances and excitement.

So how do the dogs feel before their first flight? We do not know, but as for us humans, it is a process of acclimatisation, training and understanding that each individual is different. One aspect however stands out – the dogs’ implicit trust in their handlers: If

they (the handlers) are okay, we (the dogs) are okay. There is also the faith in the pilots, ground and support crew that create an atmosphere of confidence and yet again, amazingly, the dogs pick up on this in a manner that we cannot explain but know it is there and real: A mutual trust and understanding that exists between man and dog.

With a highly trained cohort of canine candidates, it only makes sense that we appreciate and use their extraordinary talent to the maximum. The dogs absolutely thrive on challenges presented to them and their success rate in both sensitivity and specificity in all aspects of substance and disease detection continues to exceed all our expectations. The near one hundred percent success rate to date in the dogs’ detection and the subsequent follow-up by the authorities regarding the unlawful transfer and possession of weapons, ammunition, pangolin scales, rhino horn, bush meat, copper wire, illegal whisky and cigarettes, indicates the undeniable value of their contribution. Transporting them fast and efficiently to locations to maximise their natural talent is a must for us. So, give a dog a helicopter.

RHINO cunning

Ihad no prior experience of rhino hunting. So I just had to use the combined experience that I have gained over all the years of stalking and outwitting trophy animals. This hunt was not straightforward at all. The Ministry of Environment and Tourism (MET) identified three potential males in two different areas. To make sure that we’d take the right animal two rangers of

the Ministry had to accompany the hunter, myself and two trackers. And on top of that, a CNN photographer and journalist joined the hunting party to document the adventure. Not the ideal situation for any hunt,

The first day of the hunt started as usual. Find the tracks. When the game ranger

said, ‘yes it is the right one’, we started out on the spoor. But easier said than done. After walking in 40-degree heat, through soft sand and thick vegetation until two in the afternoon, and again the same story the following day, I decided that this was going to be too dangerous with such a big hunting party. This hunt was not going to be an ordinary one and there was no margin for

“This was the hardest hunt of my life. They say you hunt elephant with your feet, buffalo with guts, leopard with your brain, but the most important of all is experience.”

anywhere.

error. The black rhino in this area do not sleep in the heat of the day like they do in other areas. Here they lie or stand in the shade of a tree, but when they hear something approach, or if they smell something odd, they get up and storm through the brush and keep running.

We informed MET that we were packing up, moving to the other identified area where the landscape is more forgiving, the vegetation sparser and the visibility better.

Two hours into the six-hour journey I received a call from the Ministry to say that they had located the identified animal in the area we were heading to, but it had died two weeks earlier, of natural causes associated with age, the horns still intact. So we turned back to square one.

The next day we start out early. Find the right spoor and start walking. We walk and

walk because we know that at some point we will see him. MET confirmed it was the one, and we keep following the track. It is not like on an elephant hunt where you at least see the animal towering above the tall grass. If like now, the grass is tall and the vegetation thick, you just don’t see him. He runs away from the noise. Then turns downwind and walks back in a half-circle (like a fish hook). You don’t know when he will make the loop, because you concentrate on following the spoor. The first you know he has looped is when you hear the 1.5-ton animal storm through the brush and run.

That is when you realise you have passed him and he either heard you or got your smell. Rhino have very bad eyesight, but can hear extremely well and their sense of smell must also be very well developed.

You continue to follow the track and do the loop and find where he has rested and jumped up to storm off. And you keep on the track. The vegetation is so dense that it is impossible to see the animal when it is lying down. You cannot see further than 20-30 metres. You walk almost shoulder high in the tall grass, because the veld has not burnt yet.

You follow him through candle thorn, and umbrella thorn. Although the wind is in our favour, he outsmarts us twice. We follow the track and do not even hear him getting up and running on.

The sand is soft and we trudge on for kilometre after kilometre. It’s hot. And I know we have only today. Tomorrow he will have more tricks. We must just soldier on. He will get up and run and get up and run, until he gets tired. We must push him to get up sooner and as he gets tired he will run shorter stretches.

“

It is four o’clock in the afternoon and it is hot. We are even more tired and thirsty and our concentration is not what it should be. When you hunt big game it is at this point that you turn back and continue the next day."

You don’t walk on animal paths. You just walk on the spoor and sometimes when he goes straight through a bush you have to go through that bush, too. Sometimes you see where he pauses, when he goes slowly. Where he moves from one shady spot to another. You realise that he is restless.

We are cautious now, because occasionally he just stops and looks back. He knows he is being followed and not by something that is giving up.

It is two hours after we left the rest of the hunting party behind. It is hot and we are thirsty. But now is not the time to give up. The cameraman discovers that his battery is flat, because he never switched it off, in case of unexpected action. Now we have to retrace our steps back to the group, where the spare batteries are.

We did not realise that just there, where we turned back, the old male heard us, got up and ran again.

Back with the group it was decision time. Do we turn back now, or continue? We are tired and thirsty. The heat of the day bears down on us and the vehicle is hours of walking from where we are.

I know that if we turn back now we have to start all over again tomorrow. And then this one will be even more cunning. We disturbed him all day. Just when he wanted to doze off, we bothered him and he had to get up

and run. Earlier in the day he had run up to five kilometres before stopping. Now his running was down to 600m. He is definitely getting tired. We must push on.

We notice that he is walking zigzag. We must push harder. He knows we are behind him. Careful now. We leave the rest of the group behind. Just me and the hunter move forward cautiously. Twenty metres further we lose the spoor, because he zigzags. We spread out to find it again.

It is four o’clock in the afternoon and it is hot. We are even more tired and thirsty and our concentration is not what it should be. When you hunt big game it is at this point that you turn back and continue the next day.

At that moment I hear branches breaking and I hear him snort. Forty metres to the right he comes crashing through the bush. I turn around and shout “take him”, but there is a bush between the hunter and the rhino. The rhino charges the tracker, who is experienced enough to freeze.

After a few metres the rhino turns and trots off.

Our knees are shaking as we all gather from different directions. We have to go on now. He is angry and I don’t know how he will react, so we must all stay together. A hundred metres further on, we find the spoor again and we realise that he is going slowly again.

As a big game hunter you gain experience of animals that can hurt you if you are ignorant - elephant, buffalo, lion, leopard, gemsbok. You get a feeling for what reaction to expect. It is as if you start to ‘think’ like them. But

my years of experience do not include this one. When he slows down again and starts to zigzag, I tell the rest of the group to stop. The wind is in our favour. We are going to meet up. I just have that feeling. Fifty metres on and one of the group staying behind walks up to us to take a photograph. I hear a panicked scream and turn around just in time to see how the photographer runs towards us edgeways and over his shoulder I see the rhino in full charge. I shout “get out of the way” and he dives into the sand as the first two shots ring out.

Of course this old male did exactly what he did all day. Made a loop, stood under a tree and waited for us to back off. He must have known that what he heard was not the familiar sounds of the bush. Not an eland or gemsbok trotting through the brush. It could also be that he was familiar with the