R V E R T U F T S

R V E R T U F T S

2. Letter From the Editors

Erin Zhu and Mariana

Campano

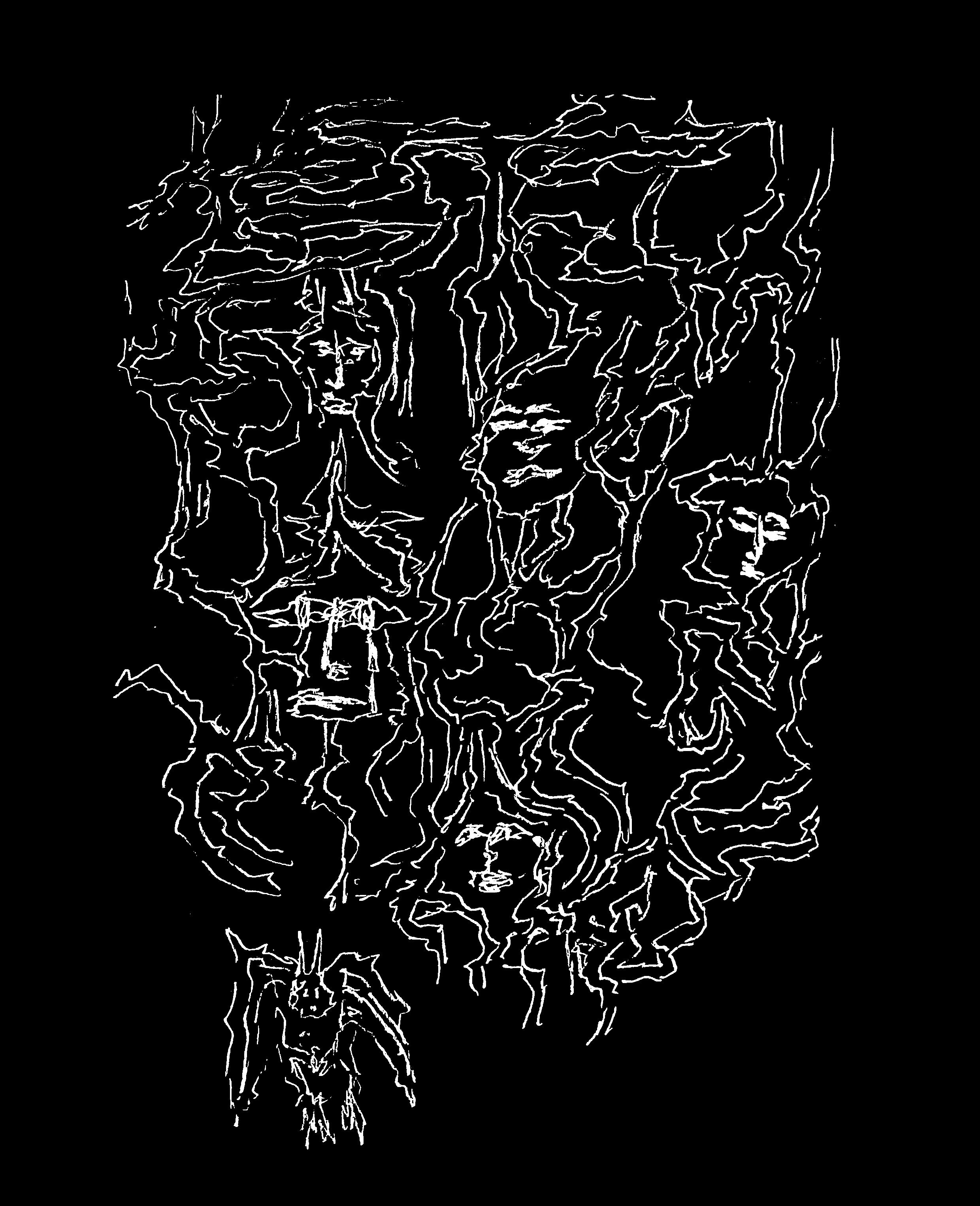

4. carcinogenesis

Samara Haynes

5. Cast

Bex Povill

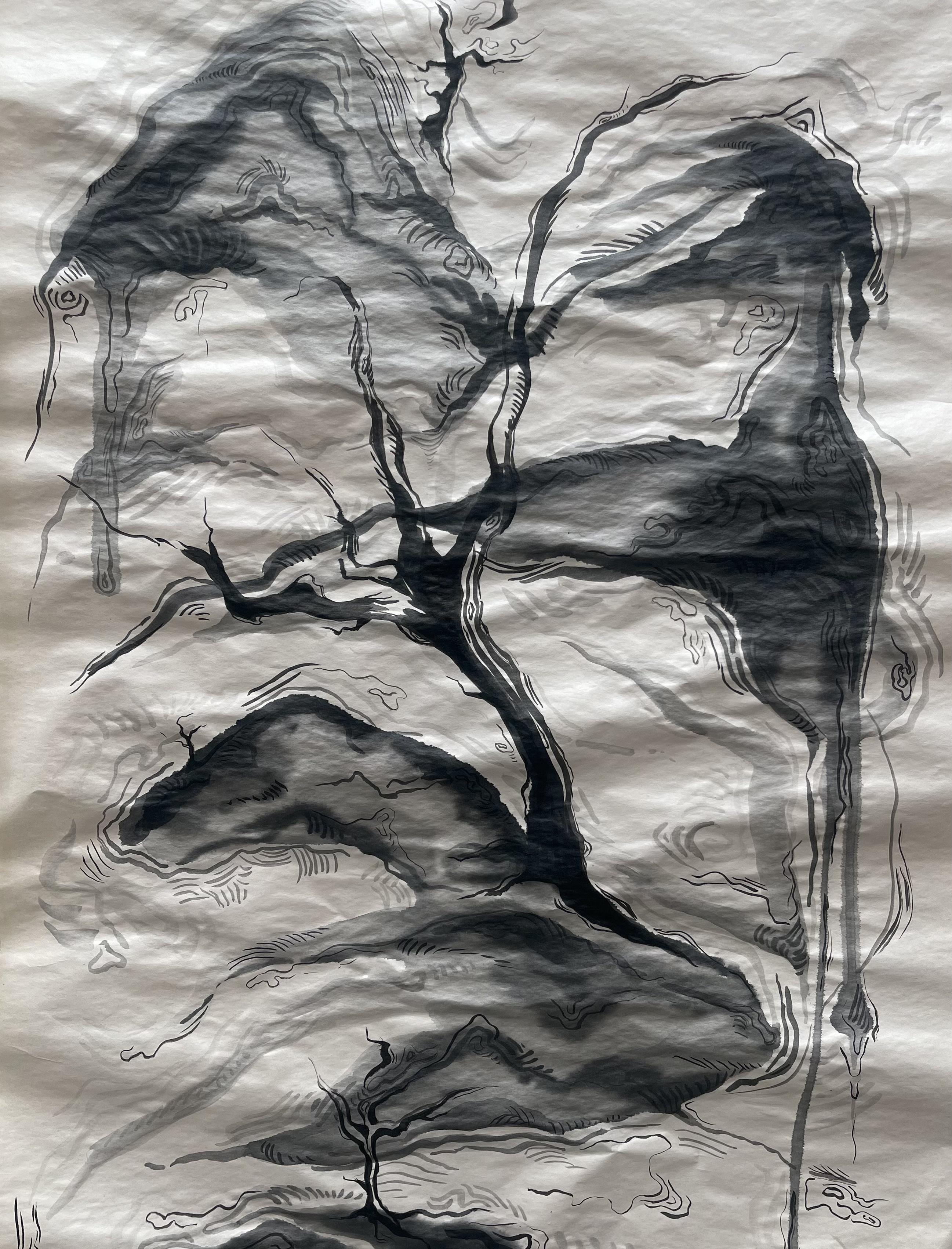

6. bog

Mariana Campano

8. Handfuls

Peaches Wright

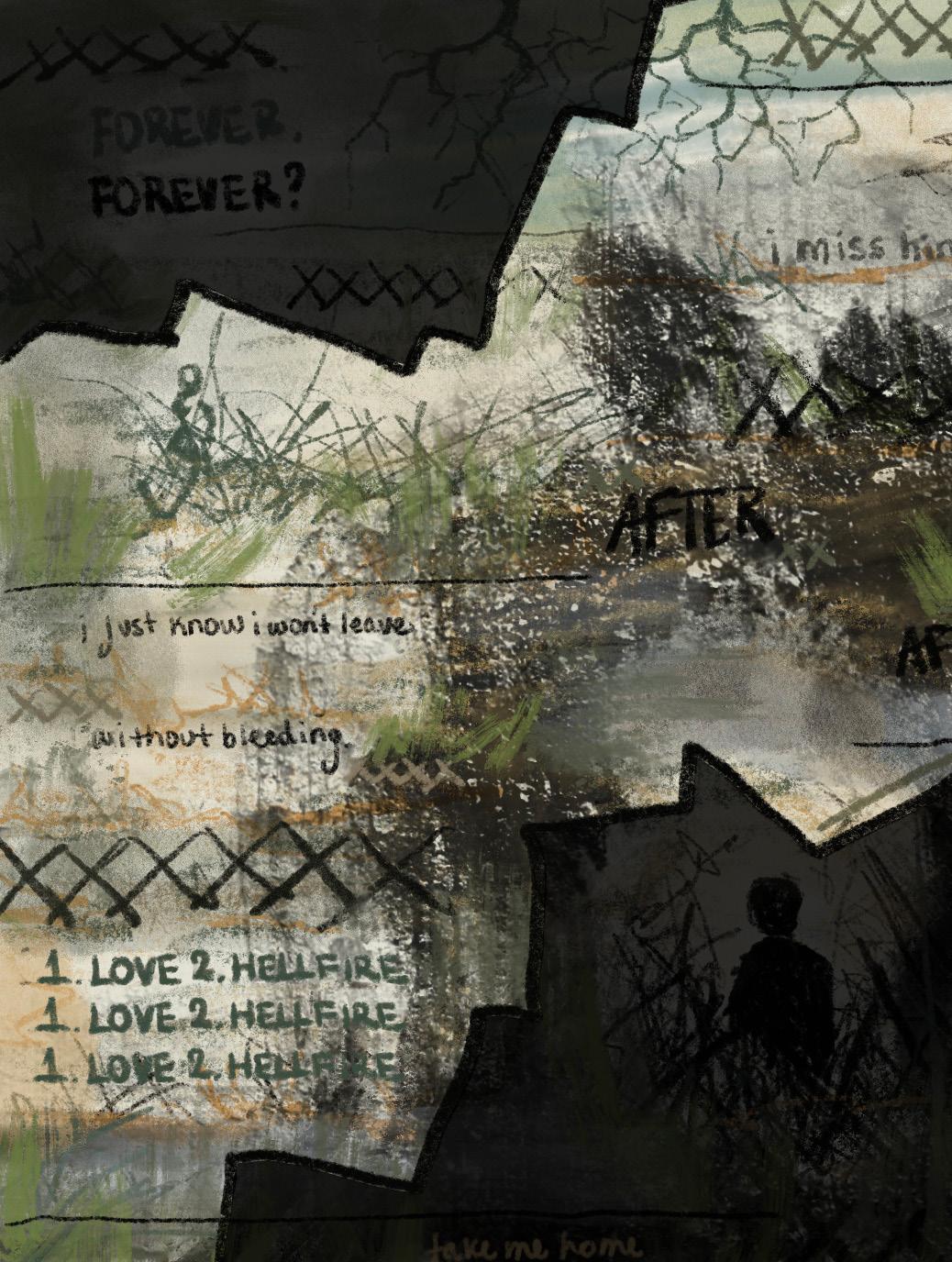

14. What It Means To Bleed Ashlie Doucette

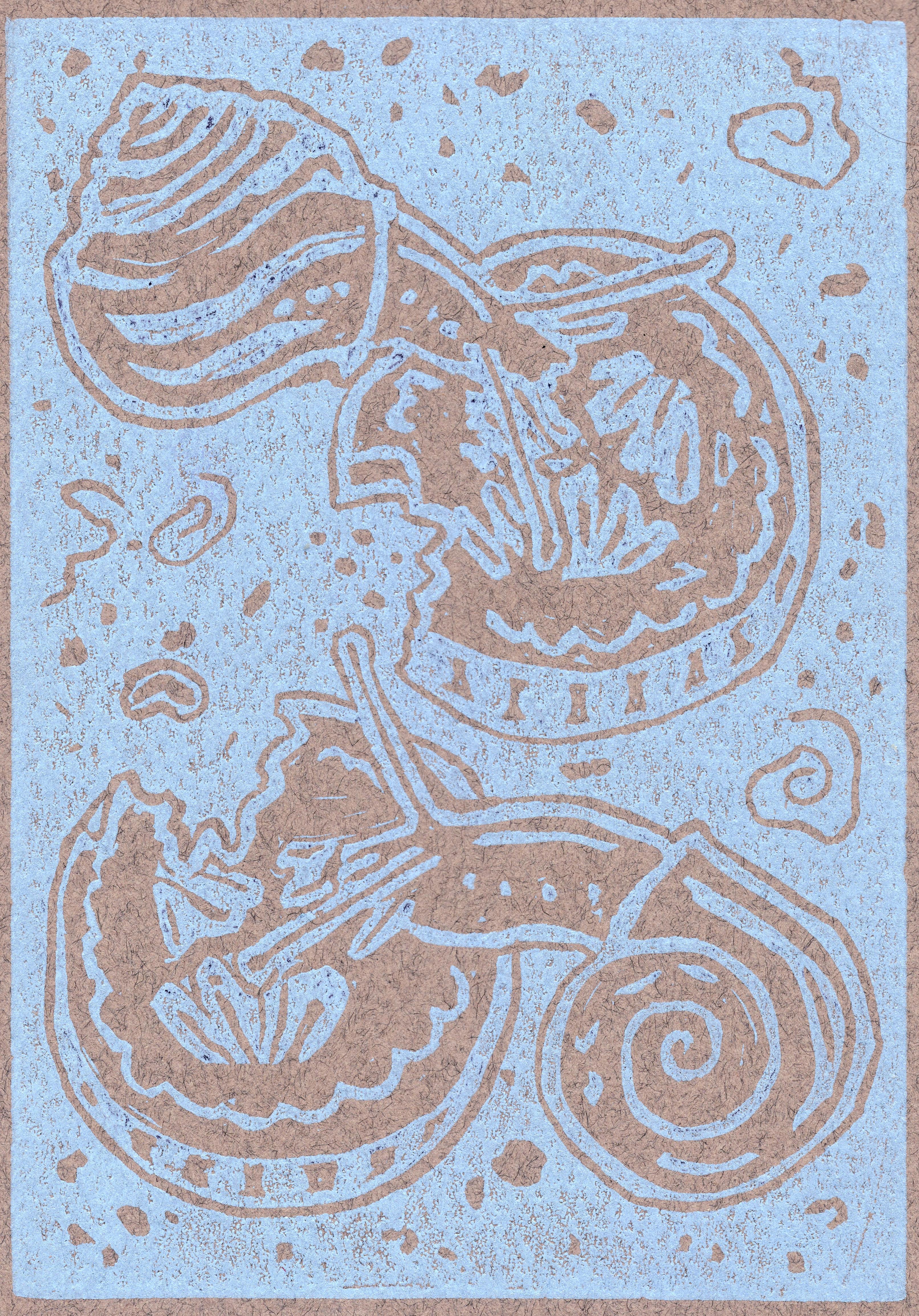

16. Filipino Groceries Cheyanne Atole

19. Bloody Boar’s Song, Pt II Reem Thakur

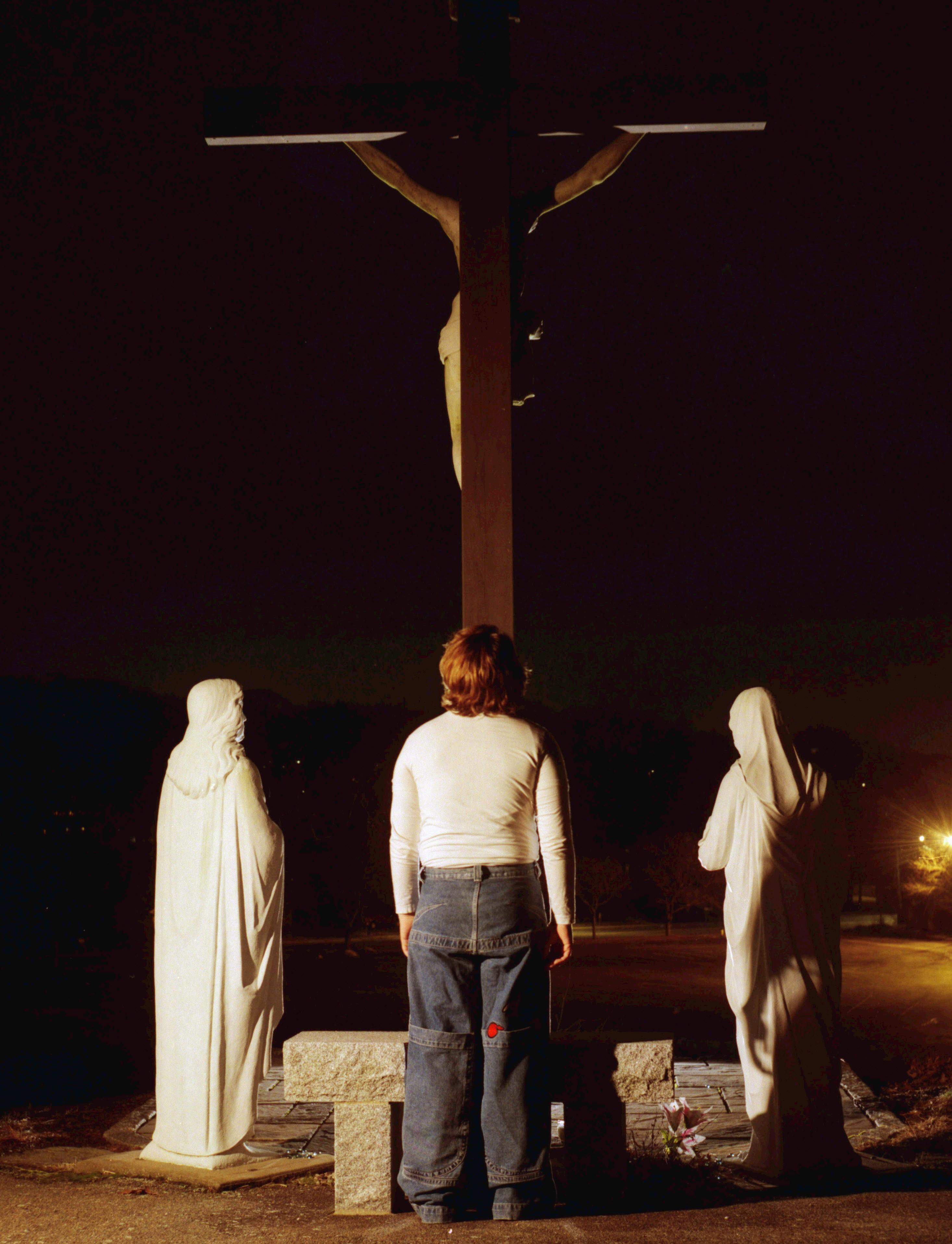

20. River’s Promise Ishan Walia

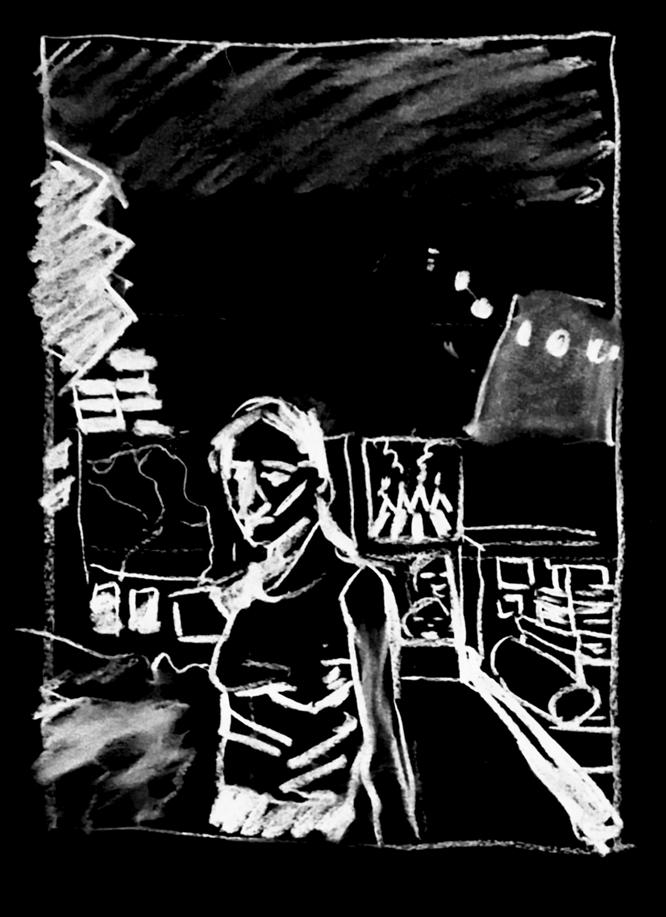

22. Sick Ione Geier

23. blunt blues E.S.

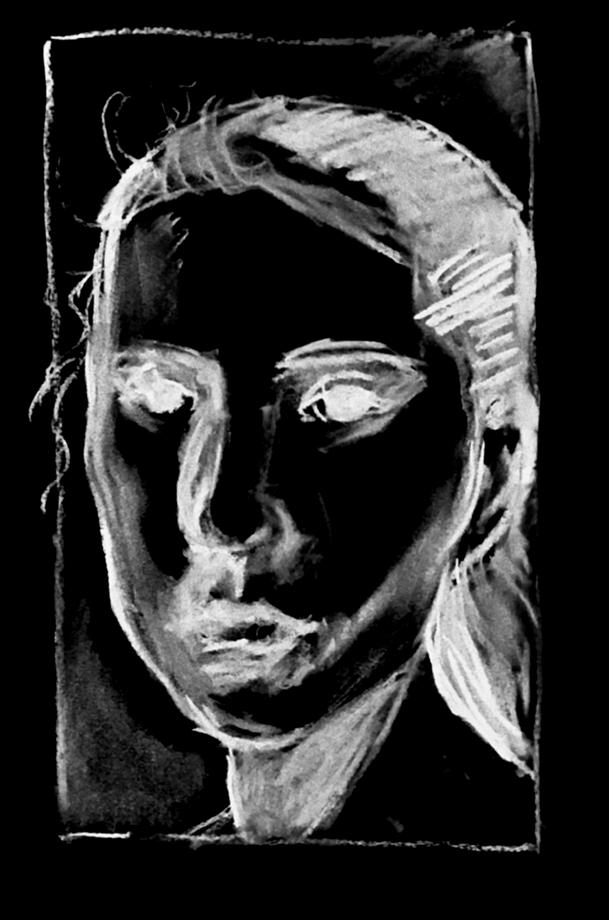

24. FOUR DAYS DEAD Wesley Jansen

29. Schrödinger’s Orange Veronica Habashy

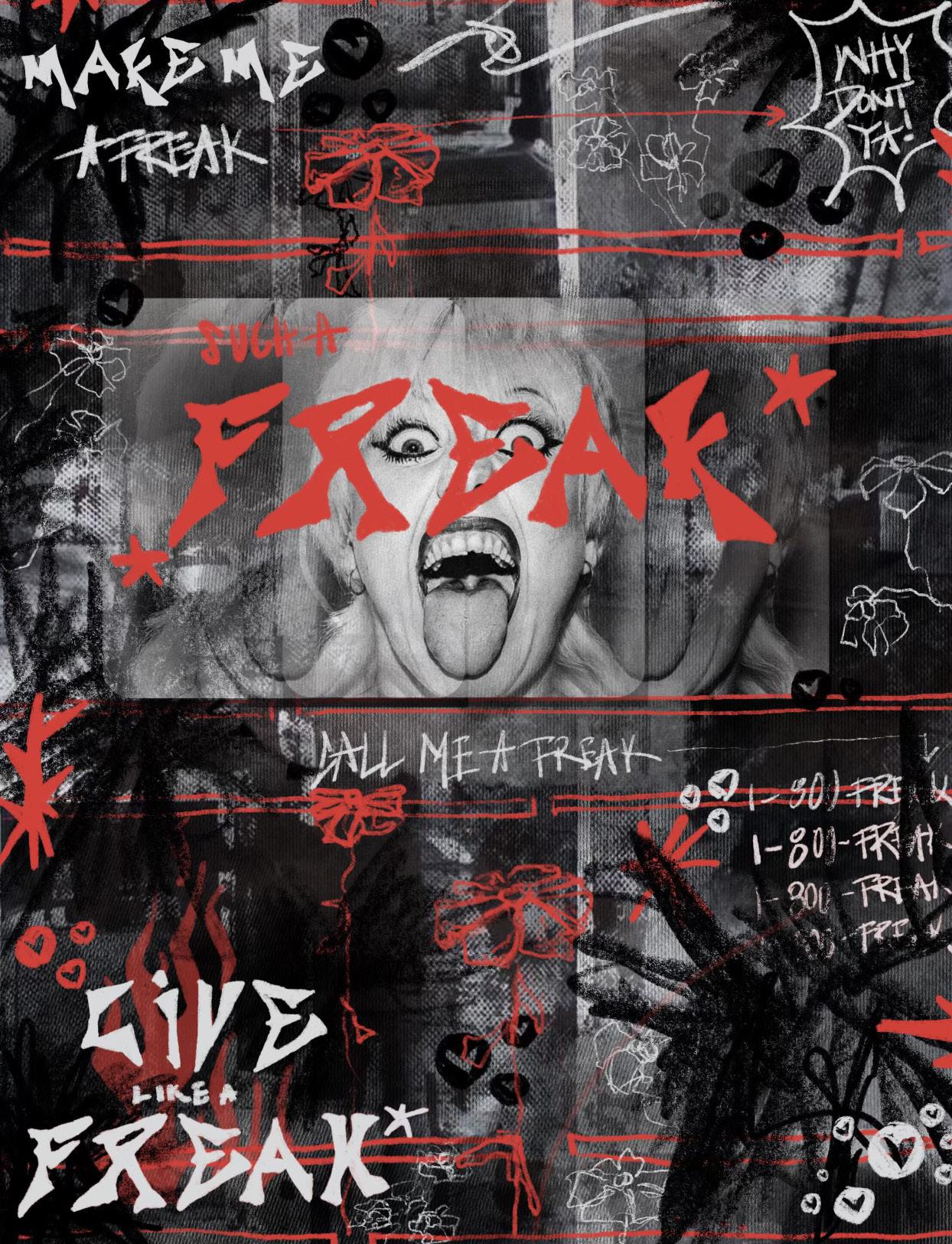

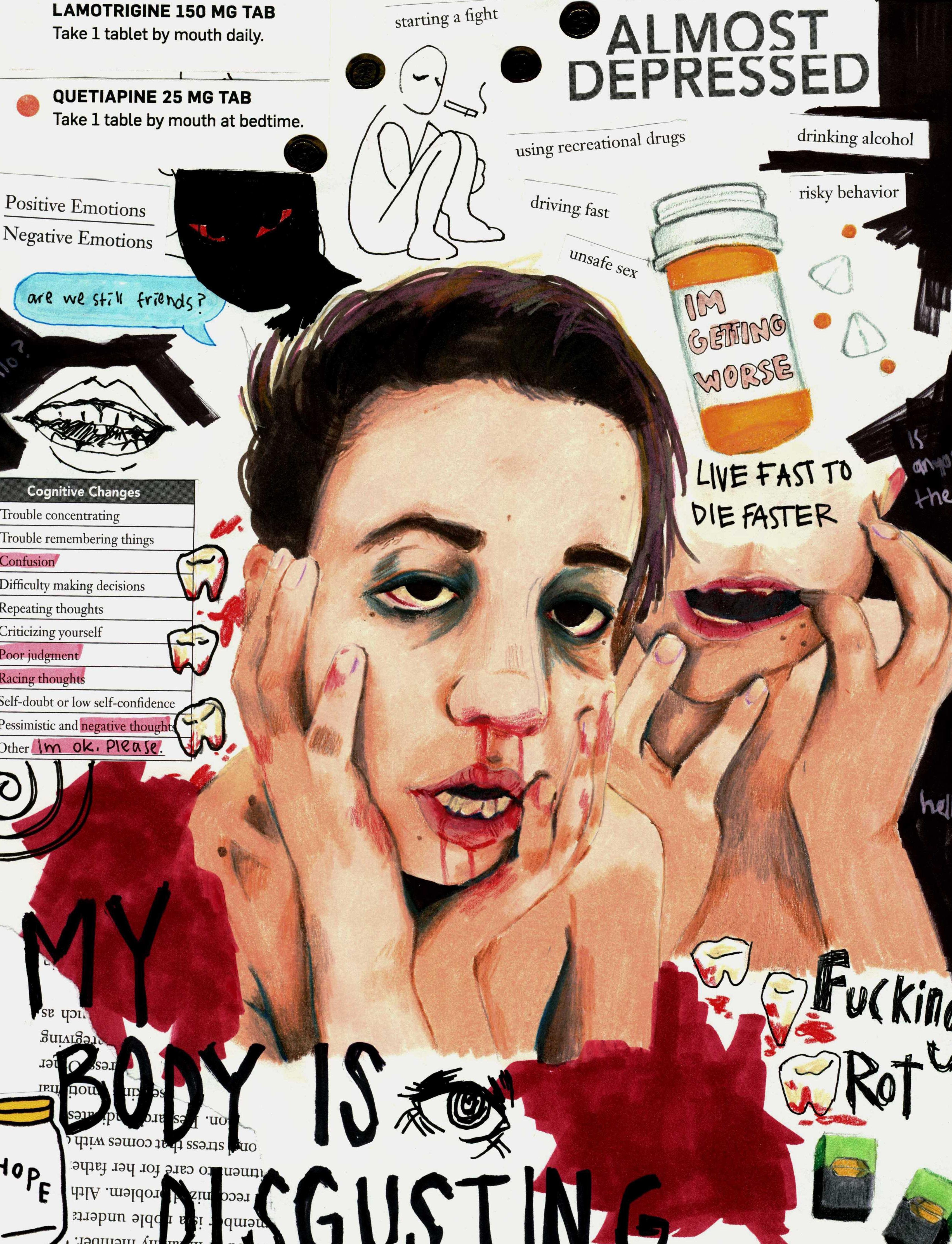

Filth. Grime. Shame. Pleasure. Secrets. Indulgence. Scum. Regret. Rage. Despair. Lust. Frustration. Muck. Fear. Panic. Ripe. Smut. Musk. Grunge. Bile. Silence.

Designers

Dana Jeong

Ahmed Fouad

Rachel Li

Kaya Gorsline

Jazzy Wu

Joey Marmo

Ruby Offer

Staff Artists

Editor-in-Chief

Emara Saez

Editor Emeritus

Juanita Asapokhai

Managing Editor

Veronica Habashy

Creative Directors

Unmani Tewari

Aviv Markus

Feature Editors

Ashlie Doucette

Miles Kendrick

News Editors

Kara Moquin

Sofia Valdebenito

Arts & Culture Editors

Alec Rosenthal

Liani Astacio

Opinion Editors

William Zhuang

Emma Castro

Campus Editors

Madison Clowes

Anna Farrell

Elika Wilson

Website Managers

Clara Davis

Eli Marcus

Multimedia Team

Andie Cabochan

Soraya Basrai

Dylan Perkins

Evelyn Yoon

Stella Omenetto

Adina Guo

Annica Grote

Erin Gobry

Elsa Schutt

Kaya Gorsline

Poetry and Prose Editors

Mariana Campano

Erin Zhu

Voices Editors

Ivi Fung

Madison Greenstein

Art Directors

Cheyanne Atole

Isabel Mahoney

Jaylin Cho

Avril Lynch

Ruby Luband

Ella Hubbard

Lead Copy Editors

Chloe Thurmgreene

Mia Ivatury

Copy Editors

Kerrera Jackson

Talia Tepper

Mallory Ewing

Wellesley Papagni

Liliane Newberry

Kazi Begum

Publicity Directors

Aatiqah Aziz

Francesca Gasasira

Publicity Team

Madison Clowes

Mathilde Vega

Angela Jang

Mia Ivatury

Podcast Team

Tamara Setiadji

Isaac Ulloa Antonio

Justin Deberry

Ryan Hachey

Emma Selesnick

Dominic Matos

Danielle Campbell

Anya Glass

Eli Marcus

Amanda Chen

Creative Inset Designer

Cherry Chen

Staff Writers

Layla Kennington

Sacha Waters

Samara Haynes

Ethan Guo

Almer Yu

James Urquhart

Ela Nalbantoglu

Dahlia Breslow

Kate Weyant

Ben Choucroun

Jillie McLeod

Connor Howe

Caroline Lloyd-Jones

Danielle Campbell

Roddy Atwood

Elizabeth Chin

Katarina Knott Ramirez

Treasurer

William Zhuang

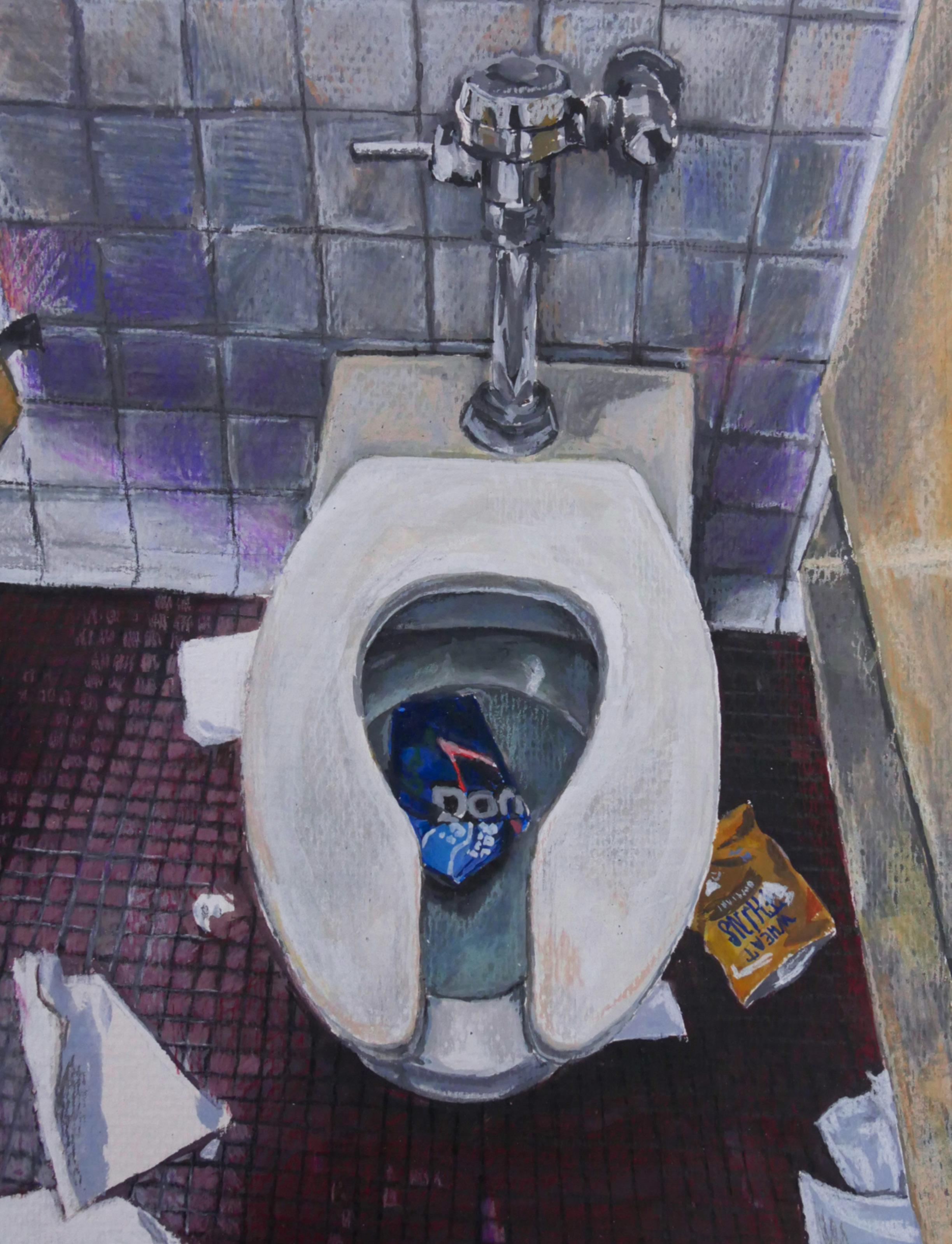

Te air in my room smells stale. Bits of trash and random receipts litter the desk next to my bed, dirty clothes strewn across the foor and the back of my tattered leather chair. Looking out through the cold glass of my bed room window, the gray sky outside confrms it: I won’t be going outside today—again.

Te theme for this issue was born from days much like this—days we can’t get out of bed, where the shower feels a little too ambitious and dinner is looking like whatever simplicities we can fnd in the kitchen. Filth is these parts of our lives: the ones we can’t bear but can never really escape, the moments and thoughts only truly known to ourselves. Feelings we can’t explain, topics we don’t discuss—in all the unnoticed crevices and cobwebbed closets of my life, flth makes its home. Shame, grief, regret, rage, revul sion—flth, for me, is about the unhealed wounds and unresolved conversations I don’t know what to do with. Filth, in all its unsung glory, is the parts of my life I can’t quite put into words, no matter how many poems I write.

But it’s not just the internal conficts in my life that make me feel flthy. Filth for me is the furtive looks I get on the train, the uncom fortable feeling I get in my stomach when I put on a skirt, once again. Filth is the angry shouts from passing cars, the glances over your shoulder on a dark street alone, the hesitation I see in a stranger’s face when I tell them my name; it’s the jealousy I hide as I imagine the blissful unawareness of those who don’t understand the things I just described. Filth is the way I run down the dark hallway to my bedroom afer switching of the lights; it’s the humid silence afer an admission of guilt, or afer turning of a movie because the painful scene just got a little too real. Filth is the inescapable hardship, and knowing you can do nothing about it except to learn how to cope. It’s the shame of feeling like you’re doing too little, or too much. It’s the guilt of feeling a little too comfortable rotting in your dirty bed.

Over the last several weeks, this issue has consumed me, mind, body, and spirit. I have put my heart and soul fully into curating artwork, editing pieces, digging into feelings, and just generally helping this issue come to life. Tanks to the incredible support of my lovely co-editor, Erin, and the hard work, sweat, and tears of the various writers, artists, and the ever-amazing O staf who have contributed to this project, I am so grateful to be able to fnally write this letter and send this issue of to you: our beloved readers. As you fip through the pages of this flthy issue, I hope the pieces you encounter inspire feelings you don’t quite know how to explain, feelings you don’t know how to hold space for—and I hope you take those feelings and fnd a way to express them and set them free, just like all of the endlessly talented creatives in this issue have so bravely done and shared with you all.

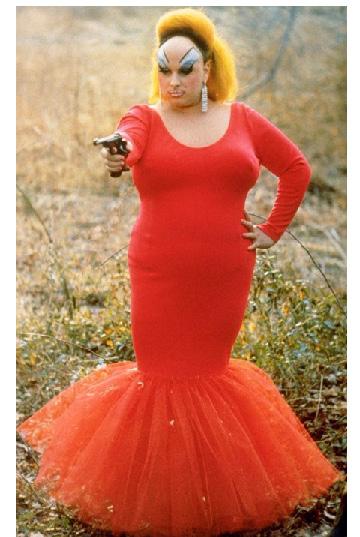

When I think back to how I felt laying alone in my dingy bedroom, stomach growling and body covered in stubble, I like to take a moment to re-enter that feeling; take a breath, and remember the resilience and self-mercy it took to get out of it. In the flthiest days, I take care to remind myself that it is not how I feel on my worst nights that defnes me, but my continued insistence on lifing myself and those around me out of our grease and grime, and into a space where we can breathe and enjoy the light fltering through the dust. It is not my ability to avoid flth that I am most proud of—rather, it is my unyielding need to push through it and live life in spite of it. In the famous words of the radical drag queen, Divine: “Filth are my politics, flth is my life.”

I love you, my sweet reader. Stay flthy—and fnd the glitter in the crumbs. xoxo, Mariana <3

Tank you so much for picking up this issue and taking the time to look through the incredibly beautiful art that was submitted. Tere was a lot of love and hard work put into this issue from our amazing artists and writers and we feel very lucky to have a role in sharing that with you.

Writing, and sometimes reading, can be frustrating and difcult, but something that I like to think about during the process is this: beneath the lines of poetry are fear and love and hate, and beneath all that lies a great mystery. But you don’t need to understand art and literature to take something away from it—you only need to be open to letting it change you!

I hope that somewhere in these pages you fnd a poem, a line, or even just a word that helps you understand yourself or the world around you a little bit better than the day before.

Tank you again for taking the time to read, we hope you enjoy it!

Sincerely, Erin

her name is derived from an Algonquian word meaning “peaceful valley” yet in headlines, she is The Most Toxic River in the Country poisoning the neighborhoods she hugs close to her chest.

so they fence off her banks and scoop out her infected tissues thousands of pounds of toxic mud; a sanitized apology forty years too late.

but when they sent my grandfather to Vietnam, he never wanted to go for love of her, his river, and how he longed to hold her again.

they told him he would save the world.

they lied about so many things, like they never told him he brought a piece of her with him— not in his heart, but in 55-gallon drums.

it was her tears that he dropped from planes, simmered in factories that burned her fngertips. they opened her mouth and she gulped down their carcinogenic byproducts until she was drowning, and her blood infected all it touched.

man and river died apart, decades later in a hospital bed, cancers metastasized, ecosystems stripped, inoperable. they were not the only ones who learned of those lies too late.

her blood still courses through the veins of her sisters across the sea. children bloom, then wilt in her wake—even now she longs to hold them close.

they knew what this would do to them all.

By Samara Haynes

By Bex Povill

On Tursday you tell me you want us to give up sugar. We are two days from the weekend and we are fading. First, I notice my hands growing pale, crumpling in the mirror like the bills on our kitchen counter. And you’ve started to wheeze in the evenings. Your breathing changes when your nose is stufed with wrappers from stolen candy. Where else are you to hide them? When I can’t breathe, I pull tafy from my lungs. I am reminded of this when you ask why I always leave our conversations looking less alive. You ask this like you’ve pulled all the life from my bones. I reply, I don’t know, speaking through cupped hands as I watch yours slip beneath chemical compounds. You’ve lost your double chin and I’ve lost my shadow. At last, we’ve emptied our cheeks, once red with fever, pink with halflife. We don’t know where we’ve gone wrong. We don’t know where we’ve gone. Empty wrappers, hollow shells are all we have lef

by Peaches Wright

June watched as Grandpa swayed in a plastic bag, clutched in her dad’s fist and hanging by his khaki shorts. Her dad had the bag crumpled and twisted at the top so that Grandpa bulged out a little in a heap at the base. There was no wind in Bloomington. Grandpa’s only movements came from each stride of her father’s as they walked through campus. June wondered if he was dizzy. No, she thought. He’s fucking dead.

June’s dress rode up at her waist. The wrinkled fabric hung at the crease of her ass and revealed her bunchy underwear each time she moved. It would have fit last summer, but now she just looked like a poorly dressed doll. The straps of her training bra interfered with the neckline of the dress, causing a jumble of lines and colors on her shoulders. She didn’t have boobs like the other girls in her class, but she wore

Othe cotton shelf as if she could coax them into existence. Spiky hairs ejected from her legs. She wasn’t wearing much. Still, the tiny dress managed to adhere itself to her thighs and unstick itself with each step forward. Stick. Unstick. Stick. Unstick. Walking with arms hovering inches from her torso, June willingly sacrificed every inch of exposed skin to the beating sun.

On the two-hour drive to the campus, June had tried to count the trees but lost interest immediately. The rental minivan was old—the AC whimpered, and the air refused to reach her in the back row. The car radio was set to old country music she didn’t know the words to. A man sang through the glitchy machine with a thick Midwestern accent until his voice began to cut out after a while. June’s family sat in silence for minutes at a time while the sound system emitted a wild crackling noise. Her older brother, James, clutched his new iPhone, clacking away at the flashing neon screen, his pre-calc homework lying neglected and creased under his sweaty thigh—pages he had promised their mom he would bring. June knew he wasn’t going to do it. June’s younger brother, Anders, pressed his face into the car window, entertaining himself by kissing the condensation with pursed lips and drawing back to examine the mark he had made. He repeated with the side of his cheek and the tip of his nose. Grandpa was perched awkwardly beside her, and she shifted away. The bumping roads would occasionally rearrange him in his bag.

When they arrived, June immediately felt sweat beading in her hair. After 10 minutes, the strands began to frizz at the roots. After 20, sweat began to creep down her legs from her crotch. Bloomington, Indiana had a UV index meant to suffocate. June understood less and less why Grandpa would want to end up here.

✮

The bag was never the plan. June’s dad would have wanted Grandpa to have been put in an urn for this, or a container, or just something more official than plastic. But the special box with his name engraved wasn’t coming until late September—there was apparently a hold-up from an unprecedented amount of orders (June guessed there were probably a lot of people dying that summer) and the trip to Indiana had already been planned. So, Grandpa stayed in the plastic bag he arrived in. Of course, when he showed up in the mail, he was concealed within a compact cardboard box. June knew this because she had been curiously rifling through his things that had also come—an oversized gold watch, emerald cufflinks, old chewed-up pipes with tobacco still in the barrels—when she

hastily threw open the flaps of Grandpa’s package and saw him as a pile of fine, white ash. She had stared, knowing that the bag was knotted shut but still hoping she hadn’t touched him.

✮

When June had first heard that Grandpa wanted his ashes spread at his former alma mater, she thought it was odd.

“So we’re all going to go there,” her mom said.

Squinting, she started to laugh at first but pulled the sound back into her lips. Her mom looked tight and her dad looked away. “Oh, uh, okay.”

Maybe her parents didn’t really mean it when they said they were going to scatter Grandpa illegally all over a private institution. But they obviously did, because there he was, clutched in a plastic bag as June and her family walked past large vines stretching over the surface of a building, threatening to suffocate the walls. June wondered if maybe that building indulged in the strangling, that at least it would reap the benefits of escaping the undying heat. She stuck out her jaw to reach an itch on her collarbone and looked like she was trying to catch a bug in her mouth. Unsatisfied, June drew her hand and clawed at her chest instead, and left five fingernail marks. She looked at Anders, who had dozens of medium-sized rocks in a makeshift pouch he had made by turning up his shirt. He bent down to collect another one. When he stood, he dropped the hem of the fabric and they all tumbled out. Their parents pretended not to notice.

Reaching a large plaza, June took a seat on a bench, sandwiched between Grandpa in his plastic bag, which her dad had set down, and a seated brass statue of an old man. She turned to look at Grandpa again. He said nothing. He was a pile. He was dead. She shifted slightly in her sneakers. They felt slimy against her damp socks. Getting up, Grandpa started to sway again, and June followed, matching her steps with each upward movement of him. She contemplated him, and came up with nothing. Squeaky toes slid in her socks and June sat with a mild discomfort that Grandpa could look like groceries in her dad’s hands. She adjusted her sweat-stained shirt and the training bra underneath. James had his head down, staring at the greasy phone

screen. He kept tapping, trying to keep the green Doodle Jump figure alive. June noticed that his score was 305,679. Anders sat two yards away, yanking up patches of grass.

It was like that all afternoon: James and his screen, June following her dad, Grandpa swinging. The sun sank and June felt less heat on her back, but the stickiness of her legs and armpits persisted like she had gum trapped in her crevices. Before long, she heard mosquitoes begin to buzz. She wondered if they knew Grandpa had blood once, or if he would always just be dust to them. June didn’t really know what she thought, either.

June’s father wasn’t at the table when she had learned Grandpa had died.

“He’s really upset. He’s taking some time for himself,” her mom said. Fidgeting with the band of her bra, June watched Anders handle his soggy meatloaf and James conceal his iPad underneath the table, glancing at it when their mom wasn’t looking. It was covered in a thin film of Dorito dust.

“Maybe it would be nice if we all thought of a nice memory of Grandpa to share,” her mom said. “I think it would make your dad feel nice to know he was loved. June, can you start us off?”

June’s mom loved this kind of shit. She liked to turn everything into a game. Her dad wasn’t even there.

“Uh, I guess, well, I know he used to play with me a lot when I was a baby, on the floor of our old house. And I would laugh at him.”

June’s mom beamed, but James, still looking at his screen caked in orange dust, said: “You don’t remember that. You were like one year old. Plus I know for a fact that we have a picture of that upstairs above the banister.”

“Shut up.”

“Hey. Don’t say ‘shut up’ to your brother.”

✮

June’s dad knew Grandpa best. June knew Grandpa best as ashes in a plastic bag. June knew logically, and from what her dad had said, that her Grandpa would have been a great one. The problem was that June, James, and definitely Anders, were born too late to know him. To An-

ders, Grandpa’s disease was like the name of their tour guide two summers ago: “Oh, Kate Parkinson, so you’re like Grandpa!”

To June, Grandpa was like a faraway idea. When June flipped through the archives of her brain for memories of him, the best she could come up with was a still image—and it wasn’t even hers. She had taken it from the wall, framed above the stairs of her home. Therefore, June knew Grandpa best as ashes, because at least this way June had looked at him face to face and felt like she understood something, remembered something. He’d never before given her that satisfaction.

By five o’clock, it looked like June had gone swimming. She tugged at the skirt of her dress so it would lower over her underwear but it popped back up when she let go. They had trekked over the entire campus. June counted fourteen bug bites on her left leg—four of them on her ankle bone. Her feet felt soggy in her shoes and sweat collected on her flat chest. June patted her bra down to soak up the moisture. She squinted at the sun, which was partially obscured by a large tower.

“Why here, again?” Her family turned around.

“What?” Her dad spoke.

“Just like, why did he want to be buried—or, I guess, spread—here, at a school? Like, isn’t it illegal and stuff?”

Her father frowned. “This was an important place to him. A really important one. Like where he met Grammie.”

“But… they hate—hated—each other. They got divorced and then got remarried and never talked to each other again. Can you just tell me why? Like, why a school, we’re in a school. I don’t really know what we’re supposed to get out of this—”

June bit her lip. She expected her dad to yell, to respond, anything, but he said nothing. He just turned away and continued walking. She wished he had made her feel something.

“June, that was really rude.” Her mom sighed. “I’m really disappointed in you.”

June watched as James beat his Doodle Jump High Score. Do do do!! It chimed. High score!! He wasn’t even looking.

They didn’t bring up what June said after that. At dinner, her family talked about Pokemon, the newest Supreme

Court Justice, and the smell and taste of mint. June noted a few times that she liked mint very much, even in ice cream, and no, she didn’t think it tasted like toothpaste. Anders shared, “I like to eat my toothpaste sometimes.” Grandpa sat in the corner on the dark crimson bench beside her dad, wedged between the perpendicular cushions, and didn’t say anything. Three minutes from campus, they were in a poorly lit diner with peeling floral wallpaper.

After dinner, June, her family, and Grandpa in his swinging bag returned to a heavily thicketed area obscured behind two large stone arches with a mudded creek. June’s dad had spotted this place some hours ago, after the bench with the brass man. Since they couldn’t do illegal shit during the day, June’s family had waited until the dark had fallen. After finding this place, June suggested they go to the tacky boutique store across the street. Her mom said that her dad wanted to continue walking, for Grandpa. June thought Grandpa probably didn’t give a fuck.

Settling by the sloping bank of the creek, June’s dad opened the plastic and Grandpa appeared. He was extremely pale and ground into fine powder. June didn’t want to touch him, but everyone else began to fill their palms with Grandpa, enveloping him in their cupped hands. June felt like she was engaging in some sort of cultic ritual. She’d never thought she’d hold a person like this. Her mom glared. June bent down hesitantly and let her fingers sink into him. She stood back up and Grandpa stared at her, inches from her face. June screwed her brows together and held her breath. When she began to move away, part of Grandpa caught wind and a small amount of ash blew from her fingertips.

When June, last, walked away from the plastic bag with her handful of Grandpa, she ventured past a large oak near the farther bank of the creek. Her family had gone off in different directions. She saw the top of Ander’s head far off to her left. He was digging a large hole. June bit her lip, shifted her weight to one hip, and let Grandpa fall through her hands to the ground below, sticking out like cocaine in the dark soil. She turned her palms to look at them. They were covered in him. June returned her gaze to Grandpa’s pile in

the dirt. She took the toe of her foot and pressed her sneaker into him, indenting the soil. She had flattened him against the earth. Grandpa persisted.

Frustrated, she began to move her foot in sweeping motions in an attempt to thin him out. Grandpa’s wouldn’t budge. Instead of one large puck-shaped pile, he became a collection of closely scattered granules. She kicked him, and Grandpa flew upward and some dozen bits of ash landed a few feet away. He remained just as unnerving. June thought that if Grandpa had requested to be buried here, of all places, he’d have the decency to not look so white. Then again, Grandpa ending up in the forest behind Indiana University was arbitrary in itself. Maybe Grandpa would have rather been dropped in an old classroom, sprinkled in a light bulb in the library, or next to the brass man.

Digging her nails into the ground, June retrieved as much of Grandpa as she could, pulling him up with the soil so that he mixed with the dirt and turned slightly brown. She turned him over like compost and pushed him back into the ground.

Go… away… Her knees were planted in the dirt. Grandpa remained.

Stop… being… so…white!

June lifted Grandpa upwards with too much force and he splattered onto her cheeks and into her tightly pursed lips. She spat him back into the ground. Her face grew hot. She folded him into the earth, incessantly. Over and over again she kneaded. Her dress was too short to reach the ground, but it fluttered while she pushed him into dirt and twigs. Specks of him littered the dress. He stained her shins. There was a little Grandpa in the crevices of her shoes. June sat back on her heels and ran her hands through her hair. When she looked back at them, she saw they were dirt-stained, and saw Grandpa underneath her fingertips.

Bile rose in her throat. June wanted nothing more than to be nauseous, but the only thing she could produce was seething tears burning on her cheeks. She continued to stare at her hands, at dead Grandpa all over them and all over her and all-fucking-everywhere. Knelt in an ironic form of worship, staring at Grandpa and her disgusting dress and more Grandpa all over the floor, tears fell into her hands held out

in front of her and mixed with Grandpa so he began to dissolve into her skin.

“GO AWAY!” She sobbed. “GET OFF OF ME… please…” June wiped Grandpa onto her dress, leaving dirty streaks. She didn’t even know him. She didn’t want to touch him. Enveloped in Grandpa, dead, and ash, June saw that all around her, Grandpa laid, smashed, persistent white in the semicircle around her frame. June dropped her head and felt sweat and tears mix like eggs into dry cake batter.

Hearing a twig snap, June’s head shot up. It was her dad. Quickly, she pulled herself up and stumbled back.

“I… um…” She hastily tried to wipe her hands together, dusting Grandpa off into the dirt, but he was already stained into her fingerprints. As June was doing so, she realized that ash residue covered her dad’s fingertips too, whitening the tips of his nails. She met his gaze, and he looked back at her emptily, like all of him had been vacuumed right from his chest. The white soot of Grandpa lodged into the soles of his shoes as he walked carefully towards her. June looked away and rubbed the edge of her eye with the back of her wrist. She left ash on her face, pressed into the crevice of her eyelid. Tears continued to fall, hot and coagulating with the residue of Grandpa.

Reaching forward, June’s father gently took both of her hands in his. She looked at both of their palms, now faced upwards, bleached in white soot. He took his hands and retrieved the hem of his shirt, leaving her palms suspended upwards in the air. Slowly, he began to wipe at the mixture of Grandpa on her hands. He lifted the fabric and reclaimed the ash from her face. Kneeling down, letting his knees press into the soil coated with white, he began to wipe at her kneecaps, shins, and the tips of her shoes. June just cried.

This morning, I found a pool of blood at my head and for the first time, I understood its beauty— the edges branching in every unpredictable direction, the core: vibrant, dancing, wet with life, just like summer cherries that settle beneath your fingernails and between your teeth. It’s not about a bleeding thing, although I would like to tell you about one: one time a bunny bled out in the yard and we were too afraid to watch the blood seep through flesh and earth so we tied it up in a plastic bag and buried it under a pear tree; but the burying only left me haunted by the possibilities of what the bunny was becoming—

I imagined it, swollen from sitting in the pool of its own blood, then gangrenous and hollowing as the last of the life drained from it.

This morning, when I find the pool of blood at my head (spilled from an ordinary cut on my pointer finger)

I trace its movements, and it reminds me of all the things I have sealed in plastic and left to rot;

I realize that today I would leave the bunny where it was, blood running freely through the dirt, letting it become what it will and I want to know that you would do the same for me.

By Ashlie Doucette

By Cheyanne Atole

Shame (for me) is a Filipino grocery store. Every distance is more vast when home is a sea away. My mom had a handful

of places that made the miles feel less stretched, where she could exist among familiar faces. She needed to be there—the closest traces of wholeness, and she

took me wherever she went. These tiny stores were all the same, quaint and sandwiched between six other stores. They were the end of the distance she wore on her face

and it was all to smell the pungent wet fish. In this production of The Philippines: The Play the scene is staged: sweat, electric fans, pale tiled floors, and looming decay

in the kick of the fish—their metallic stench—burrowed in rows and rows of ice. Their long familiar faces. The cashier weighs one and tells my mom the price

that isn’t marked on any of the shelves. The bags of exported leaves, waiting to be cooked far from their forgotten trees, the jackfruit, the pandasal, the strawberry jellies,

the foreign brands that confused me and hardened my hate, peeling me away like the labels I could not translate, while the white fluorescent lights flickered above

the shrimp chips I secretly liked, even though they could not hide the rot, all the shame of being lost, while I snacked on corn nuts that she bought, even though I said I didn’t want

them—to be dragged again and again from the slanted minivan—to all the stores without names—across the California desert. I did not know what home is, and I still cannot find it

in the burlap bags of jasmine rice. I am searching inside the fish displaced, fried far from their ice—grasping with my own bare hands, I will feed myself until I feel whole.

By Reem Thakur

i ache with a neruda, forlorn to hyacinth blood i drank, for verse falls to the soul like dew to the pasture; i write in her name. the lovely girl of austen and pigtails, i reeked of a heathcliff she fondly clung onto as she perched herself on my back and held my ivory horns. i crave her weight. i wish she still let me carry it. you can call me iago spewing lexical poison, a force of motiveless malignity— i did not mean to rip the red ribbon from her hair and tie it around my throat, but a pig will be a pig; my hooves are dirty and i will eat my way through anything.

i neither care for burns’ mouse, nor bishop’s fish, but the fox called my girl to heaven and i had to drag her down. i got used to her weight on my back, you see, i am no cowering mouse or fruitless fish. so i pounded the soil and pounded the slop— and pounded the girl, for what it’s worth. i love the way she breathes in iambic only when i rest upon her thin neck. i love when her collarbones pop out in a pentameter, just one beat off from my 4-chord song. we are an unlikely pair, but my petal girl of primrose and violet no longer sings with me, she gulps.

the stars weep a quiet melody, dripping silverlock and stone, pouring their wispy shades into the awning of her irises— i see my foul reflection in them and let out a whinny. she looks at me with a lifelessness i never recalled, forgetting the times i oh so sweetly read her alcott, and brontë, and kafka, and woolf, and wilde. when the day comes i will take my precious pet to the grave, and i will sink my teeth into her for the last time, as that is the only way a bloody boar like me truly knows how to kiss goodbye.

In autumn’s tepid air lonely men of Providence seek the river’s promise, wandering fingers finding their imagined inheritance— bounty tilled in her muddied banks, harvested from bloodied fields till she stank of death.

Dull brick bejewels the waterfront where the green of her banks was torn open with dirt-crusted nails, frantically digging for fertile wombs where sons would grow to hate the Father they will one day succeed— heir apparents to their planters’ legacy, claiming Columbia as their own.

Axes cleaving guardians from their shrines, the rubble used for a new temple built upon the water in honor of the defiled. Surely the river protested as men waded through her bowels, taking measurements of their curves to build efficient dams that choke her and plunging iron into fishes’ flesh. Surely the river shrieked as loud as hammer-beaten steel screams, but now silence sweeps through the bends and beds where giddy hands once gleaned for gold.

Long since had the vultures left but fouler a creature had lingered to feast on dilapidated lips and waterlogged lungs. Sick smiles protrude from their mouths as they pronounced her sweet, vomiting late into the night. Winter hopes to smother them all.

By Ishan Walia

By Ione Geier

I don’t like to share drinks or food with most anybody. It makes me feel all yucky and paranoid. I’m a germophobe, I guess. But I don’t mind sharing with you. In fact, I wanna share real bad. It’s a bond, I think—a secret little message that says, “I like to share saliva with you.” I don’t mind all your mouth germs in mine. I relish the bacteria growing on your teeth. I want your stomach acid and for our insides to mix and mingle and become something different. I want a lot of things, actually. I want our arms to tangle. I want our hair to knot. I want your breath in mine, hot down my throat. I want to bite the popsicle where you licked it. I want to share teeth marks. I want your mouth to open wide and swallow me whole. Swallow me. Drown me. Suffocate me with light. I want it all, baby.

There’s a lukewarm glass of milk on the table. There are your fingerprint smudges on the cup. I can count the creases of your skin, pressed in sweat. Take me by my hand, would you? Smile at me. Tug at my hair. Grimy bugs wriggle through our fingers, dirt caked under our nails. I wanna drink your blood. I’ll gnaw on your bones. Hug me. Hold me. I’m voracious, you know? Plunge me into the sea, that’s alright. Drag me down under. Flush me out with saline, like tears running down my knees. Salt caking, cracking, sticky in my palms. I’m bleeding—all my guts are spilling out.

Eat them up for me, will you?

Lick my wounds. Stitch me up with your lips. Let the strings catch in your teeth. I’m starved. I wanna be sick with your saliva.

By E.S.

i met you my freshman year, doe-eyed and desperate. i was quick to infatuation—no one warned me of the risk of inhaling deeply as if you’d be my last breath.

filling my lungs to the brim with your smoke, each exhale reminded me of the ash collecting under my fingernails, the curling, crisp edge of the burnt paper, sunken undereyes, a sign.

euphoric at first, then exhilaratingly draining afterward. too late, i realized i was hooked on your feeling of escapism— should’ve said no to that first puff, but they also didn’t tell me that the smoke eventually dissipates, just like the promise of forgetting, and leaves only swirling thoughts behind.

the high wears off, and leaves me alone in a crowded basement, feeling devastatingly worse than before i met you. instead, memory becomes smokier and grows putrid, only to be felt at night, in dingy rooms and trashed alleyways. didn’t think about the risk of being intoxicated and alone. no one, or thing, in this world has made me feel so charred.

craved the sweet release of vice, of feeling less for a little while, of numbing the constant roar, of escaping responsibility.

don’t want to remember, so i turn to you.

now, i know all too well, a dependency i can’t quite kick. the million-dollar question at the end of the night is how much longer will i poison my body with you before it gives up?

By Wesley Jansen

Once, I sat on a bench and watched five children playing a game. The game didn’t have many concrete rules aside from dying. They ran around laughing, yelling at each other, and then one would pretend to stab the other and excitedly proclaim ‘You’re dead!’ The dead child would happily lay in his constructive grave, putting on a tragic face to imitate the dead. He cried ‘Guys,’ then moaned ‘I’m dead!’ Then his friend ran over, stood above him, moved his hands elaborately, and revealed that the dead boy had been revived. Lazarus cried in joy and ran around looking to die again.

I got back to my residence hall. Swaying outside of the front doors, I smiled to convince myself that I was already forgetting her. My earbuds sounded an improvised percussion. Opening the doors to the lifeless building, I stood in the foyer for a few minutes, scrolling on my phone.

Making my way to my dorm, I saw five boys who lived on my floor, sprawled across the carpet. They were either drunk or high, maybe both. One was slurring incessantly, trying to make a joke. The only reason I knew he was joking was because he was laughing. The one next to him was sobbing. This bothered me—I had never seen them express anything more than passivity. Under the staircase, there were two more. One was on the floor, his knees tucked into his stomach, his soft gaze focused on nothing in particular. He was being held by his friend, who was mumbling comforting words that I couldn’t quite hear.

The scene was not so bad because of the distress itself. It was the way they carried themselves through life as if they weren’t allowed to be distressed.

I walked up to one of them and his vacant eyes wandered past me. I asked him what was happening.

“I…” he stammered and began to sob. “I’m sorry about this.”

“What happened?” I asked. He stared through me and began to sway and shiver. He tried to hug himself, but he continued to cry.

I asked again.

“You… you can’t say anything.”

“I won’t. What happened?”

He took a moment. Closed his eyes and inhaled. Then he looked at me again and began to speak.

And he told me something. He moved his mouth, describing something horrifying that reframed the way I viewed these people. Something that made me dry heave. I could tell that he was struggling to tell me, from how after one sentence, he would refrain, look down, and finally continue speaking. It was terrible. As he continued to confide in me, I felt myself already forgetting the words he hadn’t yet said. I cannot for the life of me recall what they were.

My eyes got glassy and I tried to say something, but I couldn’t. I looked at the boy being cradled under the staircase and I started to cry, too. I felt like I should say something so badly, but I looked at this disintegration and just started to feel like that. Disintegrated, that is. And to feel disintegrated is to not feel like much. So when I felt myself slipping, I wanted to say something and in a genuinely empathetic despair of verbiage, all I could produce was “I’m sorry.”

And I said it again and again.

So I return to intimacy, because you can say anything or nothing, and the outcome is really the same. I can’t thank her enough for the way she destroys me. Love is violence. To love is to kill the former self, allowing a more expansive, incorporative identity to emerge. It makes you Lazarus. God, to me, has always represented a glimmering death. An epiphytic assassination of the ego, a force of demolition and rebuilding. A part of me died in that bed. I lost matter, energy, in favor of the absorption of a foreign origin. Maybe that’s all this is. Some natural physical collision.

But I’m not a true Buddhist or Taoist or even a communist, so nothing is really physical, and one can’t sweep away expectations—those succulent impossibilities. They’re not physical, but they tell you things: that it will all be different very soon. It’s enough to keep you warm for a while, wrap you up in your fake future. It is only when you’re bundled in a silk blanket that you discover it’s a web. But the expectation is not malicious in the trap it creates, only in the realization it induces: the aching epiphany that you have become a fly. You wait to be eaten. You moan ‘Guys, I’m dead.’ Then you cry in joy at a wriggling escape, looking to die again.

By Veronica Habashy

I.

Among strawberry flesh and bones from birches there is my heart: a cardamom seed. She has waited her whole life to be kissed by the pestle, a most romantic kind of weight, and crushed into shards. To bring someone a sweetness— that transient pleasure washed over by a bitterness one must learn to enjoy, acquire a taste for, so to speak —too soon forgotten.

II.

The first time I was patient: for nectarines in April.

Taunting suns in the black wire bowl on the cold marble counter, the only time we could all agree on something— that waiting. That dripping flesh to be indulged in over the sink. Reward for aimless days spent— latent period— insistent thumbs gently crawling across hairless freckled carmine skin, searching for the first sign of readiness or perhaps initiating decay.

III.

Placed alongside plush fruit whose skin approaches rupture; minute by second most by more,; a final orange teeters on rot. Cardboard is suffocating, ethylene, effused and clutched as precious haunts radiant pocked skin, enters with no permission and thaws that perfect configuration of flesh. Bitter pith tries in earnest to contain, to perform its only purpose.

My mother only wants to keep me alive— that’s not what I mean. I mean she wants other things too— joy and sleep and my spine free from spiders.

She means no harm in ripeness.