from a place passed by

28 a statement from mboard veronica habashy, ashlie doucette, miles kendrick, unmani tewari, & angela jang

from a place passed by

28 a statement from mboard veronica habashy, ashlie doucette, miles kendrick, unmani tewari, & angela jang

Editor-in-Chief

Veronica Habashy

Editor Emeritus

Emara Saez

Co-Managing Editors

Ashlie Doucette

Miles Kendrick

Creative Directors

Angela Jang

Unmani Tewari

Feature Editors

Ruby Goodman

Sophie Fishman

News Editors

Lucy Belknap

Anna Farrell

Arts & Culture Editors

Kerrera Jackson

Sofa Valdebenito

Opinion Editors

Megan Reimer

Mia Ivatury

Campus Editors

Chloe Thurmgreene

Rohith Raman

Poetry & Prose Editor

Ivi Fung

Peaches Wright

Voices Editors

Emma Castro

Max Greenstein

Art Directors

Ella Hubbard

Erin Gobry

Sta Writers

Billy Zeng

Joyce Fang

James Urquhart

Kate Weyant

Danielle Campbell Connor Howe

Neya Krishnan

Ela Nalbantoglu Alec Rosenthal Siena Cohen

Amon Gray

Claire Stromseth

Oliver El Hadj

Peaches Wright Ishana Dasgupta

Devon Chang

Demilade Ajibola

Designers

Emma Selesnick

Rachel Li

Ruby Ofer

Anya Glass

Madison Clowes

Dana Jeong

Ahmed Fouad

Joey Marmo

Felix Yu

Lead Copy Editors

Caroline Lloyd-Jones

Talia Tepper

Copy Editors

Wellesley Papagni

Henry Estes

Alison Tsai

Oyinkansola Akin-Olugbade

Lucie Babcock

Isabella Tepper

Amena Weifenbach

Publicity Directors

Francesca Gasasira

Mia Ivatury

Publicity Team

Madison Clowes

Sophie Littman

Emilia Ferreira

Carson Komishane

Sta Artists

Isabel Mahoney

Amanda Chen

Phoebe McMahon

Avril Lynch

Ruby Luband

Jaylin Cho

Cherry Chen

Ella Hubbard

Elika Wilson

Yayla Tur

Felix Yu

Maria Sokolowski

Leila Toubia

Website Managers

Dylan Perkins

Andie Cabochan

Treasurer

Andrea Li

Bazinga!Bingo!Eureka!Huzzah!

Dear Reader,

What, I wonder, do you know about the Circus Smirkus traveling clown troupe? Did you know that it is the only tented traveling youth circus in the United States? at each year it touches the hearts, souls, and minds of approximately 42,000 New England adults and children? In case you did not, allow me to explain. Founded in 1987, Circus Smirkus is the creation of European clown enthusiast and accomplished mime Bob Mermin. Every summer, my family would make the pilgrimage up from the mossy swamps of Charleston, South Carolina, to the shores of Kennebunkport, Maine, where my grandparents lived and where Circus Smirkus found itself each July. It was here, surrounded by the screams of sobbing children and booms of circus cannons, that I met the love of my life. Towering over my 10-year-old frame, holding out his hand to usher me through the doors, a gorgeous, freshly pubescent, red-nosed amateur juggler ipped a switch in my brain that could never be unswitched: I’m gay. And I would tap this clown.

Epiphanies are more than spur-of-the-moment happenings. ey take time and energy to materialize, like dormant volcanoes waiting for their magma to push through the vents and !ssure to the surface. Was it the teenage clown, with his handsome features and twink-like charm, that turned the light bulb on? Or was he merely the straw that broke the camel’s back, an a rmation of what I always knew but could never quite admit? In reality, I had been questioning my attraction for a long time. Boys on the playground, my older brother’s friends from soccer, that picture of Daniel Radcli e in Equus—something had not been adding up for a while. Not quite the spontaneous realization, my epiphany was the result of a lot of long nights and deep ponderings.

My point, I guess, is that we all deserve a little more credit. When inspiration strikes and epiphanies occur, they do so because we’ve put in the work to make it happen. Archimedes didn’t just sit in a bathtub one day and shout “Eureka,” he spent years studying density or buoyancy or whatever it was that he was so excited about. e same could be said about the Observer. Abstract concepts become pitch ideas, pitch ideas become new dra s, and dra s become real articles. As you peruse this issue, take note of all the little epiphanies that brought it to you, and remember the work that created those epiphanies in the !rst place. And if you happen to see a six-foot-tall clown with gigantic blue shoes, rainbow suspenders, and a icker in his eyes that says, “I could take you far away from this life,” tell him to give me a call.

Miles

I just thought of this I just wanted to say

Please tell me exactly how much it is going to hurt.

I scorn you for not knowing what comes next, I really do (Tat’s what I tell myself)

Veronica

I am hardly graced by epiphany Tis letter is going to be edited so many times so it’s not really, truly In the moment of their conception that you read these words— Not at all and not for any of the ones to follow either—

am curious if you, like me, are a slow reader. When I’m reading, I get the invasive sense that I have missed something critical—perhaps a comma that changes the meaning of es as I near the end of the poem, article, or book, and it feels like each word and punctuation presents another

But for a moment, for me, imagine you are hearing them as such. We say it now all together: “I just thought of this”! And you believe it. (I do)

is not always entirely true. In the context of the can override some of this fear by promising ourselves that we will return to it. rst sitting. I trust you will nd much inside this issue worthy of your engagement and interpretation. However, also take comfort in knowing that this is yours to hold on to for as long as you wish. You are welcome back here—into the ideas sprawled across these glossy pages—anytime. personally, I’ll be back. Both to the pages of this issue and also to the

By Ruby Goodman

Everything we do requires some amount of energy. Brushing our teeth, making breakfast, walking to class— these are routine tasks most of us barely notice doing. ere are, of course, various factors that determine our capacity to function at a high level, but, essentially, we wake up every morning with a regenerated fuel tank that propels us through our lives. is unlimited energy supply is especially vital for college students at a place like Tu s where the way of life o en demands students to balance their academics with jobs, robust social lives, and extracurriculars.

However, the busy routine that many students and faculty take for granted is largely unattainable for students at Tu s who experience chronic illness. Many in the chronically ill and disabled communities describe the di erence between their lives and the lives of their healthy counterparts with something called the “Spoon eory,” a concept that originated in 2003 when blogger Christine Miserandino tried to articulate the symptoms of her autoimmune disease.

“Each spoon represents a nite unit of energy,” explained Amalia HirschhornMartinez, a Tu s senior who was recently diagnosed with dysautonomia, a nervous system dysregulation disorder. “Healthy people, especially the average college student, may have an unlimited supply of spoons, but those with chronic illness will have to ration them throughout the day.”

Something that most of us wouldn’t think of as a taxing activity—having a conversation with a friend, grocery shopping, washing a dish—can be totally draining for someone like Hirschhorn-Martinez, who struggles with chronic fatigue, nausea, and brain fog daily. “Let’s say I have six spoons in a given day, and I expend three on going to class,” Hirschhorn-Martinez said. “ en I’ll only have three le to do di erent things like making food, taking a shower, going on a walk—and it leaves very limited space for interacting with life.” e amount of energy a speci c task requires may vary

hugely on a day-to-day basis. And in college, the amount of spoons necessary to stay on top of things is high. “I used to be able to attend class, have a robust social life, complete my necessary assignments, and engage in clubs, but now I’m unable to keep up with any of that,” HirschhornMartinez said.

Chronic illnesses can take many forms. Tu s senior Sierra Shostac, for example, has hypermobility syndrome, which leads to chronic pain, di culty walking, and joint instability. ough her symptoms have improved with medication and physical therapy, she deals with discomfort on a daily basis. is is made even more di cult by the nature of Tu s’ campus, full of stairs, hills, and buildings without elevators. “Tu s is a really hard campus to be on,” Shostac said. “It makes it hard to want to go anywhere if you don’t have to, and I have to plan my day around the amount of time it’ll take to get somewhere or how much stu I can carry given the length of a walk.” For Shostac, these constant calculations can be exhausting.

According to part-time Tu s lecturer Leandra Elion, who works in the Department of Child Studies, Tu s doesn’t have the same requirements as public universities to provide special programs and protections for their students with disabilities. However, this doesn’t mean they don’t have an obligation to do so. “If Tu s is an organization that gets any federal funding, which it does, they have to abide by the Civil Rights legislations and not discriminate against people who have disabilities,” Elion said. In other words, students at Tu s with disabilities of any form must be a orded the same opportunities as their peers, even if the process of attaining those opportunities looks di erent.

experience, from the classroom, to the residence halls, to navigating campus and through any Tu s-related activities that the student wishes to participate in.” ese accommodations can take the form of Ly credits, specialty furniture in classrooms, extended time on assignments, and more. Tu s also o ers support through Health Services, the Counseling and Mental Health Service (CMHS), and the O ce of Equal Opportunity.

ese e orts also extend to students with mobility issues. According to Behling, Tu s is currently undergoing a physical accessibility audit of its campus. “ is year-long process has involved students through focus groups, surveys, mapping areas of concerns and walk-abouts on campus. e administration will use this audit to prioritize accessibility needs moving forward,” Behling wrote.

In compliance with these federal standards, Tu s has many structures in place to support the university’s chronically ill and disabled students. Tu s’ Student Accessibility and Academic Resources (StAAR) center is among the most impactful. According to a written statement sent to the Tu s Observer by Kirsten Behling, the associate dean of the StAAR Center, “ e StAAR Center works with [students with chronic illnesses] to identify access barriers and put accommodations into place to

With these administrative e orts toward inclusion and support, there is no doubt that many students have bene ted from Tu s’ resources. However, it’s not always as easy as requesting an accommodation and receiving it. “ ere’s a lot more advocacy that hasn’t happened,” Hirschhorn-Martinez said. “Even though I’m promised some of these things, I still have to go through a lot of di erent systems to ensure that they’re in place for me.” ese bureaucratic hoops can, in some cases, be attributed to the complicated nature of things like insurance, but there’s also something of a bad reputation among students around the StAAR Center’s e cacy. Both Hirschhorn-Martinez and Shostac have heard stories of students not getting the accommodations they were promised, or getting them only a er a long and complicated pursuit.

Additionally, many of the daily accommodations that chronically ill students need are not even able to be granted by in-

stitutions like the StAAR Center. ey are, rather, under the jurisdiction of individual professors. ough the StAAR Center can suggest and encourage accommodations, only the professors can grant extensions, excuse absences, and adjust class policies. Elion suggests that this exibility is key for professors helping chronically ill or disabled students. “It’s not in lowering your expectations, but exibility in how you will meet those expectations… at has been a research, evidence-based practice of allowing accessibility,” Elion said.

Professors, though, may not be able to fully grasp the ebbs and ows of their students’ health. “It’s hard when my health impacts me 24/7,” Hirschhorn-Martinez said, explaining why the accommodations granted by the university are sometimes not enough. “It’s not like one day of the semester, I’m gonna have to take an extension. You know, these things repeat themselves. ings are cyclical. I have good days and bad days.” A professor may be lenient about one, two, or three missed classes or a handful of extensions. But there comes a point when it might become di cult for both the student—who may feel apprehensive about asking for further exibility, fearing their professor will misunderstand their genuine struggle as a lack of commitment—and the professor, to do more. But this doesn’t mean that the student doesn’t need more. Working through these academic knots can be physically and mentally straining for students with chronic illnesses, leading to vicious cycles of stress and an accumulation of work.

“I’ve gone up to a professor saying sorry for missing class, and I’ve had a professor tell me, you’ve already missed two classes, I’m a little bit worried about attendance, even a er I’ve sent them an accommodation regarding attendance,” Hirschhorn-Martinez said. It’s also possible that a course is not even compatible with accommodations like exam retakes or

missed classes, leaving these students in an even more impossible position.

Some of the lapses of understanding or empathy chronically ill students experience at Tu s may be due to a more pervasive lack of awareness regarding health conditions. Even with the emergence of long-COVID, where long-term health problems like chronic fatigue are cropping up more and more, there seems to be general resistance—or at least indi erence— to talking about chronic illness in younger spaces. “People are uncomfortable with disability and don’t really know how to talk about it,” Elion said. “And why is that? It’s because…we don’t really have a truly inclusive society when it comes to talking about disabilities, right? And so disabilities are seen as sort of rare and unusual.”

Shostac echoed this sentiment. “I think usually, at Tu s, [disability] is not a big part of the conversation. I mean, everyone will joke about the hill and how terrible it is to walk around campus, but I don’t think it’s that big of a consideration in general,” she said. ose who don’t have to think about their health on a daily basis won’t necessarily view their campus through the lens of disability.

Universities’ passivity to disability and chronic illnesses seems to be a national trend. ese students are less likely to graduate than their peers and o en move through college without being o ered or made aware of the resources at their disposal. A lot end up dropping out. is can be attributed to many factors, including the profound mental strain of facing illness while young, as well as the stigma surrounding disability that undoubtedly exists in American society.

To Elion, progress begins by talking. “You’ve got to have these conversations and make changes that take place amongst the students and then amongst the faculty,” Elion said. “You’ve got to help faculty understand things, and you’ve got to help students understand things, and then bring it all together.”

According to Associate Dean for Student Support Erin Flood, Tu s has taken steps to incorporate more discussion about disability into university decisions. “We are constantly in conversations across campus about policies, processes, and ini-

tiatives that impact students with chronic illnesses, and part of our role is to raise the concerns, challenges, unique needs, and unique strengths of these students so that they are considered and present in larger institutional decisions,” Flood said. One place this work is re ected is in class syllabi, which all include a disability statement, though these are o en not verbally addressed by professors.

But no matter how much a student shares with their friends or feels supported by Tu s, health struggles can still o en impede a full social life. Students with chronic illness or pain are making constant sacri ces and considerations to exist among their peers. “For me, it comes down to prioritizing things,” Shostac said. “I know that I will be in pain a er dancing to live music or something like that, but it’s something that makes me so happy.”

ough there are many students in the Tu s community who deal with some form of chronic illness, most do not. Because of this, it can be di cult for those students living with health issues to feel at ease talking about their symptoms or asking for support. “I think I’ve de nitely felt a lot more isolation,” Hirschhorn-Martinez said. “It’s very di cult for me to not feel like I’m a burden on my friends. Asking for help is o en di cult, and even when I do, it’s hard to ask for help repetitively.”

ough the 18,19, 20–something yearolds around us may appear totally healthy, energetic, and present, anyone can be dealing with a chronic illness, and so many in the Tu s community are. “Once you su er from a certain illness, you see another side of Tu s,” Hirschhorn-Martinez said. “We need to try and gure out the right way to

By Talia Tepper

Change is probably the worst thing in the whole world. It hurts really badly. It’s whiplash. It seems futile to ever acclimate to anything when you will ultimately be uprooted. To be uprooted—passive. It happens to you. You are forced into submission, to relinquish control of this life you have so carefully curated. Unfortunately, this is harrowingly inescapable. Sorry for the bad news.

In Buddhism, the ultimate human mistake is expecting life to be permanent, within our control, and without hardship. To reject or deny the inevitability of change, disorder, and pain— appropriately named the “marks of existence”—is to reject truth.

Change is the most natural thing. It is, as the philosopher Heraclitus originally said, the only constant. My friend once said she liked moving from California to the East Coast because she felt validated that her retreat into solitude in the winter aligned with the rhythm of the earth. In theory, I too should feel inspired by the way death in nature spurs regrowth, that following every winter is a spring. In theory, I should feel solace in the companionship of the earth as I emotionally and physically hibernate and then blossom again alongside it. I try to adopt this mindset, but it’s hard to shake the resentment I feel for the changes in the weather. How can I possibly appreciate a departure from the easiest and most perfect state of being (70°F and higher)?

I want to write a manual for my younger sister so she won’t have to experience all the bad. I want to shield her. She should never have to face a hard winter. I yearn to teach her the lessons I’ve learned so she won’t have to go through the treacherous task of learning them herself. Should we warn children about all the evils before they go out into the world and see them for themselves? Or, in trying to protect them, do we do them a disservice, because they need to know, because

they’ll !nd out eventually, because it is denying them invaluable experience?

e allure of stability. e fallacy of permanence. A painless existence, an eternal summer: it all sounds so nice and comfortable, and that’s exactly the problem. Growth doesn’t occur where it’s comfortable (cliché, sorry, and there are more of these to come so prepare yourself). Growth occurs when it’s hard and di erent and new and you have to adjust and that’s hard too.

once did, and it’s di cult to watch without intervening at every corner. It’s also incredibly disorienting because she looks so much like me that it feels like I’m reliving being 15 (devastating). I can’t mold her, life has to mold her, and she has to mold herself. I can’t always be her teacher—at some point, I have to let pain do the teaching. I still do the preachy thing, and I’d like to think it’s relatively helpful, but ultimately, the clichés are empty until you experience their truths !rsthand.

Simone Veil writes in Gravity and Grace that to attempt to conquer suffering only increases our su ering, and to cower beneath it is to be defeated by it. Instead, she suggests the radical concept of allowing the void (i.e. the wound le by a iction), of tolerating and accepting the discomfort of it. is sounds counterintuitive—humans are hard-wired to evade pain at all costs (biological self-preservation, avoiding death and whatnot). And why wouldn’t we try to avoid it? It’s the worst thing in the whole world!!! But, as they say… Pain is our Greatest Teacher. e Wound is Where the Light Comes In. e Range of the Human Experience: With Great Love Comes Great Loss. With Desire Comes Su ering. Lacerations Require Lamentation (a sentiment from the poet Rainer Maria Rilke). From the Mud, the Lotus Flower Grows. Maybe you haven’t heard this last one, or maybe you don’t think of any of these that o en. But I do, all the time, and I preach them to those around me, all the time (probably too much). I’m not suggesting there is good in every experience; there are some wounds so deep and dark that it’s hopeless to look for the budding lotus amongst all that mud. Instead, I am saying that every new feeling and experience molds us, changes us, and acts as growth for the sake of itself. We would be doing a disservice to children if we tried to protect them from the world; I would be doing a disservice to my sister if I shielded her from all pain. I can’t prevent any heartache in her life, and I shouldn’t. She goes through all the same 15-year-old shit I

Kintsugi is a Japanese ceramic practice wherein one repairs broken work by !lling the cracks with gold. Metaphorically translated: in the end, one can !nd good in the pain, good in the learning, good in the growth. Even beauty in it all. Everything happens for a reason. Does everything happen for a reason? It’s hard to !nd the reason when something feels like shit and it would have been easier not to feel it at all. But not feeling is not living. And not learning. And it’s boring. Maybe everything doesn’t happen for a reason, but everything happens. It doesn’t matter how why what when where; it happened and here we are and we have no choice but to accept embrace experience learn grow repeat—to me, this is the meaning and purpose of human life.

and two years ago and a year ago and even a month ago—she knew nothing!!! She knew everything, everything she could, but so much has happened since then, and it’s been so hard and so good and so bad, and I am di erent now. And I’ll be di erent tomorrow, just a little. I will not make the same mistakes I have once made. I will try not to make the same mistakes I have once made. But I guess, on some level, I wouldn’t go back on any decision. If anything in my life had been di erent, if I were to forego any experience, I wouldn’t know what I know now. In e Metaphysics of Morals, Immanuel Kant says, “Only the descent into the hell of self-knowledge can pave the way to godliness.” Contemplation, introspection. To know thyself is to learn from thy mistakes, to better thyself, to recognize thy faults and work on them. Constant growth. Not just one epiphany but a continual, life-long epiphany, and more and more and more and more. And so on. Forever and ever. Or at least until I’m 27.

A recent development in my life is that I can literally feel my brain growing. Something new occurs in my life, and I’m like, “Ohhhh my god I get it!!! Wow. Ok cool.” I hope it isn’t true that the brain stops growing at 25 (I heard they increased the !nish line to 27, which sounds kind of arbitrary, but I’m just going to go with it). When I think about the person I was !ve years ago

I think I might sound like a Ram Dass podcast. I think I am wise and I know I am not. I am learnéd and learning. What I have learned is that I keep learning all the time. Every day. Multiple times a day, even. Every experience is a bit of growth. Every experience is something learned. A million little epiphanies and a thousand big ones. O

feels like everything has already been done. Every other movie is a reboot, docudrama, or a biopic; new songs twist and sample iconic beats—it’s as if we've lost the ability to create truly “original” media.

tone tools were the rst of humankind’s creations. en, re was discovered—which, I’d assume, was a pretty big deal. Now, we have things like laptops, sports, the internet, music, and… LinkedIn. From that rst invention came a plethora of discoveries and original tools. Traditionally, originality refers to creating something entirely new, and for much of history, that perception formed our understanding of what it means to be original. Originality quickly manifested itself in the tools that were being whittled and in the caves that were being drawn on in the darkness before the dawn of modern society. Whether it be drawings of families or simple hunting maps, the arts quickly entered the lives of humans. And since then, humanity has continued creating and making its own content. Now we’re in 2024, and

Two new movies are set to release next year—one a sequel and the other a live-action adaptation. While sequels and remakes successfully capitalize on nostalgia, the industry’s heavy reliance on them is concerning to some. As Vira Chawla, an undergraduate student interested in Film and Media Studies at Tu s, said when discussing the lack of original scripts, “I think it’s really frustrating; with a lot of these franchises, they go on to make four, ve, six, maybe even twelve movies… e quality kind of decreases, or the engagement with the viewers [decreases] as it gets repetitive.” Despite the backlash that some Disney remakes, like , have faced— largely due to its failure to deliver the essence of the animated version, its destruction of Mulan’s character arc, and most importantly, its inaccurate representation of the Chinese culture—production companies seem unable to move away from revisiting the past. Interestingly, when Disney did branch out with original lms like and —neither of which are princess movie remakes—they were rewarded with higher IMDb ratings than (7.2 and 7.4 respectively, compared to 5.8).

Moreover, the rise of the biopic genre raises the question of whether there is a lack of

original plots in the entertainment industry. In 2023 alone, 17 biopics have been released. From the two lms about the life of Elvis Presley released in the past two years ( and ), the upcoming Bob Dylan biopic starring Timothée Chalamet, the poorly received , the controversial , and Sydney Sweeney’s upcoming portrayal of boxer Christy Martin, it seems as though pre-existing real-life stories have replaced creative writing. e genre that once consisted of inspirational movies is now over owing with repetitive storylines of di erent icons.

In ne arts, however, the concept of “remaking” isn’t as obvious—it doesn’t take the form of a direct sequel or spino . Rather, artistic in uences and styles tend to “determine” the originality of a work. Artists’ works are o en in uenced by external factors. is may be due to a combination of reasons: the subconscious (or conscious) in uence of the media we consume, our admiration for our mentors or idols, or self-improvement: the list goes on and on.

Fadi Azra, a combined degree student at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts at Tu s, highlights, “Sometimes people come up with concepts and they think that it’s something that is unique or something that hasn’t been created before, but I feel like to an extent, people get heavily in uenced by things… [and they] subconsciously in uence their actions and what they do and what they create.” He adds,

“[in] our age, coming up with something original is almost impossible because of the amount of creation that’s been happening on all di erent platforms.”

As originality becomes less attainable, the debate of whether inspired works hold just as much value as what we consider “originals” becomes more complex. To this, Azra adds, “In a way… when you’re remaking something, you’re not making an exact copy of it, you’re making it with a di erent take—[you add] something that wasn’t in the older version, so in that way, a remake is an original.” is argument, and exploring novelty in the arts, brings into discussion the meaning of originality—if humans are in uenced by the ever-changing world around them, then could anything ever truly t the traditional de nition of the word “original?”

Much like the visual arts, music thrives on in uence. For example, at the time when Radiohead struggled to nish the song “Fake Plastic Trees,” they attended a Je Buckley concert, where they found inspiration. In an interview with the Far Out Magazine, Dougie Payne, a friend of Radiohead’s lead singer om Yorke, says, “Radiohead went back to the studio, and om completely changed the way he was singing, using that falsetto.” You can hear Buckley’s in uence in Yorke’s voice, yet the two artists—and their songs—remain distinct. e song doesn’t follow the traditional idea of originality as it came into fruition a er Buckley’s artistic in uence, however, deeming “Fake Plastic Trees” “unoriginal” might undermine the creativity that went into its production.

Similarly, the practice of sampling songs also clashes with the traditional denition of originality—many songs we now consider “classics” were also sampled or remade from earlier tracks. Britney Spears’ “Toxic” was sampled from a song used in an ’80s Bollywood movie, . Mariah Carey’s “Fantasy” drew from Tom Tom Club’s “Genius of Love,” and Da Punk’s “One More Time” sampled Eddie Johns’ “More Spell on You.” Even Led Zeppelin relied on heavy sampling, with songs like “Dazed and Confused” and “Stairway to Heaven” closely mirroring other artists’ work. As sampling grows more common across genres and is embedded in both new and “classic” songs, pinpointing truly original songs becomes challenging—if such a song can even exist. If originality means doing something entirely novel, then none of these artists’ works are original.

When asked about the originality of the arts, both visual and musical, John Howard, an English Professor at Tu s University, highlights, “ ere is no originality—everything is sort of inspired and everything recreates and redevelops what we have been exposed to and what we are inspired by” and that “there are ways in which we can recon gure, reshape, reinvent things that we’ve been inspired by to create what feels like an original work.”

Howard pulls into the literary practices of remaking as well, diving deeper into his ideas on originality through the book by Percival Everett, which is a reimagined version of by Mark

Twain. He says,“[ ] is very original… It very clearly cannot exist without Mark Twain’s book and Mark Twain’s character… it’s being written by a black man now… and so there is almost like a historical speculative work that reinvents the past through this work. And that is really wildly inventive.” By highlighting how remakes or in uences can still be original and inventive, Howard and Azra both challenge the traditional de nition of originality. Sampled songs remain originals because they add a unique twist. Reimagined versions of previously told stories are originals because they reinvent, not recreate. Works in uenced by other artists are original because they are shaped by new artistic hands. Biopics are original because they focus on e ectively portraying stories that might otherwise never have been heard. ere’s no denying that in this era of mass production, we’re constantly exposed to similar content and media, whether in visual arts or music. From movies to songs, patterns emerge across mediums. Our increased reliance on social media platforms as a means of communication makes us aware of every new thing that’s happening across the world, and this might make us feel as if nothing is truly novel. While 12 lms may feel excessive, it's important not to equate originality with complete novelty. Humans are in uenced by one another; we’re inspired by artists and role models, learning from their skills and abilities, and creating accordingly. While it’s crucial to be unique, perhaps the traditional de nition of originality—as doing something that has never been done before—is awed. Maybe true originality lies in how you can uniquely interpret the world around you. As Howard put it, “ e notion of originality is actually a notion of e ectiveness in recalibrating whatever it is that you’re recalibrating.”

By Celia Duhan

I saw heaven in an ant hill, then it started to pour the sky scabbed over, gathering sound clawing hands couldn’t save the sacred citizens raindrops’ barrage turned dirt to mud and the celestial city washed away

Everything is forever until it’s no more

My childhood best friend, we’d whisper yarns that rolled into balls and unraveled on the stairs to her room, where we lay curled in bed hearing scandals in the spinning of her ceiling fan she listened to the radio when falling asleep I needed quiet, no more than a murmur the White Stripes played over and over I dreamt I fell asleep, and when I woke up she and I didn’t speak anymore

By the morning, I had new friends

Worlds suspended in consciousness growing the more we dance, the more knowing, knowing air bends and constricts, an atmosphere glowing crystallized moments, refracting parallel faces night skies crack, letting rays break the glass wandering home, we search for shards of the spirit

But the world we knew last night, today is no more

Mud dries and turns to dust underneath the Earth, stoically waiting holy soldiers maintain their tunnels heaven has shi!ed and their hill resurfaces under the scattered pieces of last night’s quartz wanderers admire the diligent workers nding the spirit they sought all night return home, pick up the tale and respool its twine send out a letter to an old friend, rekindle the whispers

Because everything is forever until it’s no more

By Elizabeth Chin

e living room sits 10 inches lower than the house’s oor, recessed as if sunken into the earth, like a descending elevator stuck between oors. e metal knob on the outside of the replace is charred from the time I forgot to open the ue; we repainted the interior to cover the blackened walls, a thin yet opaque lm now settled atop the soot. e LEGO bonsai tree sits pretty on the co ee table, the meticulously trimmed leaves replaced with green plastic and the storytelling rings of the trunk built in a matter of minutes, beauty trapped in its form—a moment trapped in time. I relay my memories as such, as if ipping through a pop-up book, in constant fear that at any given moment, with the gentlest gust, my stories might collapse into a child’s tale. I’ll realize it all was just a gment of my imagination, my memories an embellishment of a distant life lived.

I recall the cozy family movie nights, joyful anksgiving mornings, drives to Honey Pot Orchards, and the warmth of homecooked meals. As the leaves transition from dull da odil yellow to ripe

papaya and deep scarlet, my childhood memories radiate into more vibrant bursts of color. Every year was the same: a fresh balsam r strung in a helix of lights, the framed photo ornaments, the melodious notes of “Christmas Time is Here” and “ e Christmas Song” on piano. ey ash at me almost violently; the re’s glow, a rich, midnight indigo, the ocean’s azure and emerald tones thinning by the shore. I take a step closer to the tide, peering through the dispersed water into the nights of ghting, the consuming anger, the resulting fear. I wade through the water and in my wake, I revel once again in the distorted images.

Day to day, I live each waking hour with a looming shadow the color of deep charcoal once the embers have gone cold. Unsure of myself, I cower beneath it. It wraps around me like smoke and seeps down my throat, su ocating my mind in a constant fog. It controls me. In retaliation, I run. But I feel it at every turn, in each new place, with every person. Two sets of footsteps approach, heavy and fast against the worn wooden boards, accompanied by strained voices. Yells echo through the tunneled hallway, two trains about to collide—a chorus I’ve listened to before. Raising my pointer ngers to my earlobes, I quickly press and release them over the canal, just as my sister taught me. e ringing screams disappear, replaced with the vibrations of incoherent syllables. My hands fall to my lap.

Last year, on a family vacation, well past midnight, I laid beside my sister as we tried to fall asleep. We stared up at the ceiling.

Do you remember when she le ? I met her with silence.

Do you— I return to the shore, where I stare at myself in the ripples. I thrash and

slam my palms against the surface before I nally relinquish control, and I sit, a child plopped in the sand. e water settles before me. For the rst time, I nd myself back in the living room.

In the northwest corner of the house, un ltered light phases through the crystalline bay windows and washes over the room. On stormy nights, animated shadows of the droplets on the glass stain the gray couch cushions, interrupted intermittently by the sharp illumination of lightning. Her words strike me. You have to be better, Elizabeth. Next time… who knows? When she leaves the second time, I brace for her departure—numb and lost, wandering about in a fantasy.

—I remember.

ere we went, tumbling from Eden. As I fell, I felt the cloud of smoke ready to consume me as I stretched out my arm into the void beneath me. I reside one step behind, one step below. Trapped in the elevator, I forebode the snap of the cable. ere is no greater agony than longing for the love of a person you resent. I rationalize so as to not feel the sharpness of it all, that prickliness that coats every ber of my being, starting from my ngertips and from the depths of my chest, a prickliness I’m convinced I created, that I could x if I could just be better. Some days I do wonder—with a bitter taste—if it would have been better if she never came back. Now, when face to face with abandonment, I’m forever left with the hope of return.

I place the emptiness inside me within a vat of desolation and join a collective that is no longer so empty. I crawl deep within the cove I have carved, beneath the mattress and into the walls. I reunite with the passing frames, snapshots of my happiest memories. I’m ooded with the tender hues of ripe blood oranges and handpeeled pomegranates. In my dreams, I cry for an alternate reality, a lost life so vivid and alluring that, even asleep, I know it isn’t so. In my dreams, I imagine that my tears will water a lost seed buried beneath concrete slabs, yearning to touch the sun. I bring my fingers to my ears. And I am happy.

By Lucy Belknap

Olivia Potier saw Southern Appalachia as a second home growing up. Potier, a senior studying Anthropology and Race, Colonialism, & Diaspora who uses she/they pronouns, grew up in Charlotte, North Carolina, but spent several summers in the area surrounding Asheville, a city a few hours away. So when Hurricane Helene tore through this part of the state on September 26, 2024, she deeply felt the personal e ects on a community close to her while simultaneously struggling to process the concrete damage. “[Picturing] physical landscapes that you’ve known your whole life literally ceasing to exist is really hard to imagine,” they said. “It feels like something that can never change, the land from underneath you. So it’s kind of hard to imagine how many people were going through that.”

Hurricane Helene rst made landfall in Florida before traveling through Tennessee, Georgia, and North Carolina, bringing with it up to 130 mph winds and 30 inches of rainfall. e hurricane killed more than 230 people and caused an estimated minimum of $50 billion of damage. is cost will be felt most heavily by the estimated 95 percent of victims who do not have the speci c insurance coverage needed for damage caused by $ooding or high winds.

Less than two weeks later, Hurricane Milton hit Florida on October 9 and crossed the state with 120 mph winds. While the recency of Helene helped motivate greater evacuation e orts among residents, the damage of Milton was still severe, spawning over 100 tornadoes in its path and killing at least 14 people. e communities most devastated by these

hurricanes are still knee-deep in the recovery process more than a month later. “In a lot of places even now, there’s still not drinkable water,” Potier said. “ power in some places. People who were formerly housed still can’t go home.”

One crucial similarity between these two hurricanes is the shocking speed with which they developed into deadly and destructive storms. is is at least partly due to record-high water temperatures in the Gulf of Mexico: hurricanes gain strength from hotter water and air temperatures, which both cause them to spin at a higher speed and add more moisture that later turns into rainfall. A er this summer, the Gulf was abnormally warm, with some patches in Milton’s path around 2–3ºC hotter than usual. e e ects of this phenomenon were extraordinary—Helene transformed from scattered thunderstorms to a Category 4 hurricane in just over two days, while Milton grew from a Category 1 to a Category 5 hurricane in a mere nine hours as it circled over the Gulf.

Researchers have conclusively pointed to human-induced climate change as the culprit for high water temperatures, as oceans absorb the vast majority of human-induced heat. Attribution analyses, which investigate the relationship between fossil fuel emissions and environmental phenomena, found that the water temperatures that strengthened Hurricane Helene were 200–500 times more likely to occur with the e ects of human-induced global warming than in normal conditions. Jonah Bloch-Johnson, an Assistant Professor of Earth and Climate Sciences, described the impact of climate change as pushing every weather extreme just a little further.

that it’s creeping into everything. Everything just carries this extra little edge, and that edge is getting stronger.”

ese most recent hurricanes are far from the only extreme weather events worsened by climate change this year. In the last 10 months, human-induced warming contributed to the extremity of heat waves across the globe, ampli ed droughts in the Amazon which enabled wild res across over 32 million acres of rainforest, and intensi ed deadly $oods in India, Brazil, and central Europe. Boston has experienced its own share of unusual weather—an abnormally warm autumn has had cities throughout New

Investment and Jobs Act of 2021 and the In$ation Reduction Act of 2022 invested a combined $50 billion in climate resilience programs, upgrading roads and bridges, supporting climate resilient agriculture, and improving water infrastructure. is proactive work is essential to protecting atrisk communities and reducing restoration costs, particularly given that every dollar invested in disaster preparation is estimated to save $13 in damages and cleanup.

However, Hurricane Helene exposed the weaknesses of these resilience attempts by hitting hardest an area generally unfamiliar with severe climate disasters. In Asheville, an area previously perceived as a “safe city” for climate refugees escaping coastal areas and extreme heat based on its temperate weather conditions, just 0.72 percent of homes and businesses have e extreme rain, that’s one thing if you’re in Florida—it’s terrible, but it’s a thing that people expect,” BlochJohnson said. “But if you’re in Appalachia, and suddenly these things are happening that never would have happened before— this small change [in climate] suddenly pushes you into a completely

locally. In 2018, Woolston said the O&ce of Sustainability conducted a resilience study on the Medford/Somerville campus in which it brought together stakeholders to examine its climate vulnerabilities and assets. It also worked with the Tu s Emergency Management Department to factor climate change into its hazard mitigation plan, which prepares for a variety of potential crises. “We asked our consultants to look at the impact of climate change and how all these risks that they identi ed would be impacted by climate change,” Woolston explained, examining how climate disasters like wild res and hurricanes might be worsened by global warming over the next 25 years.

tions that are a whole order of magnitude larger can then match that,” he explained. “You can’t get to giant mitigation without rst getting through the smaller steps.”

Ultimately, while the e ects of climate change are already making themselves known, the e ort to combat further warming is far from over and remains deeply essential to preventing further damage. “ e reality is…we can make climate change as terrible and destructive as we want,” Woolston emphasized. “How destructive do we want it to be? If we want it to be less destructive, we still have to be actively involved all the time in reducing greenhouse gas emissions.”

As it becomes increasingly cult to predict where and when the next climate-related weather crisis will occur, some universities s have taken it upon themselves to build climate resilience

However, the increased focus on the consequences of climate change does not detract from the goal of reducing fossil fuel emissions in the rst place. Tu s remains committed to achieving carbon neutrality on all Tu s campuses no later than 2050. Woolston described Tu s’ plans to achieve this goal, which focus heavily on transitioning to renewable electricity-powered ground source heat pumps for heating and cooling in university buildings, given that this is currently responsible for 75 percent of Tu s’ emissions. e school has already begun this process with projects like the construction of the Joyce Cummings Center and the renovation of Eaton Hall, gradually preparing each new building to be hooked up to a future renewable energy system.

While reaching carbon neutrality at Tu s may not single-handedly have a substantial impact on climate change and extreme weather, Woolston emphasized that the goal is not just to reduce Tu s’ contributions to global emissions, which are currently 50–60,000 metric tons of carbon dioxide a year. “At the university, we think about it in a bunch of different ways,” she explained. “We can use our campus as a test bed. We can use our campus as an example. We can use our campus as a learning opportunity to train our students on how to [achieve carbon neutrality] in other places.”

Bloch-Johnson agreed that Tu s can at least lay the groundwork for carbon neutrality on a larger scale. “Change is sometimes something that scales in a way that, if there are institutions and places that learn how to do something, then institu-

In the meantime, though, as each approaching natural disaster is exacerbated by climate change, each newly a ected local community must learn how to adapt and respond. “I think that there’s an acceptance of, climate change isn’t something that we’re preparing for, it’s something we’re in the middle of,” Bloch-Johnson said. In the context of Helene, Potier highlighted the growing role of neighborhood mutual aid and other rudimentary community e orts to adapt to the challenges presented by its damages. “I’ve been very inspired by reading stories about communities organizing hyper-locally to support neighbors,” Potier said, describing the efforts of friends in Asheville to adapt to water and power shortages, developing their own simple water ltration systems and other makeshi solutions.

To Potier, this illustrates what climate resilience might come to mean in the future. “It shows to me the ways in which the people and the communities themselves are needing to take climate resilience into their hands,” they said. “I think that focus on our hyper-local ecosystems and communities is going to be where many of us will have to turn to in this era of climate emergency.”

to

Is experiencing the smell of and the of seeing a film on the a relic of the

buttered popcorn, stranger sitting next to you, lights, excitement big screen past? the dimming of the the belly laugh or sobs of a

By Siena Cohen

We come to this place for magic, we come to AMC theaters to laugh, to cry, to care

As Nicole Kidman began her preshow monologue at an AMC showing of In Our Time, I looked around the movie theater and failed to locate the “we” the Academy Award winner was referring to. Aside from me and my friends, the theater was nearly empty; we had a private screening experience for just $15 per ticket. It seems like this experience has recently become more common among moviegoers. Is experiencing the smell of buttered popcorn, the belly laughs or sobs of a stranger sitting next to you, the dimming of the lights, and the excitement of seeing a lm on the big screen a relic of the past?

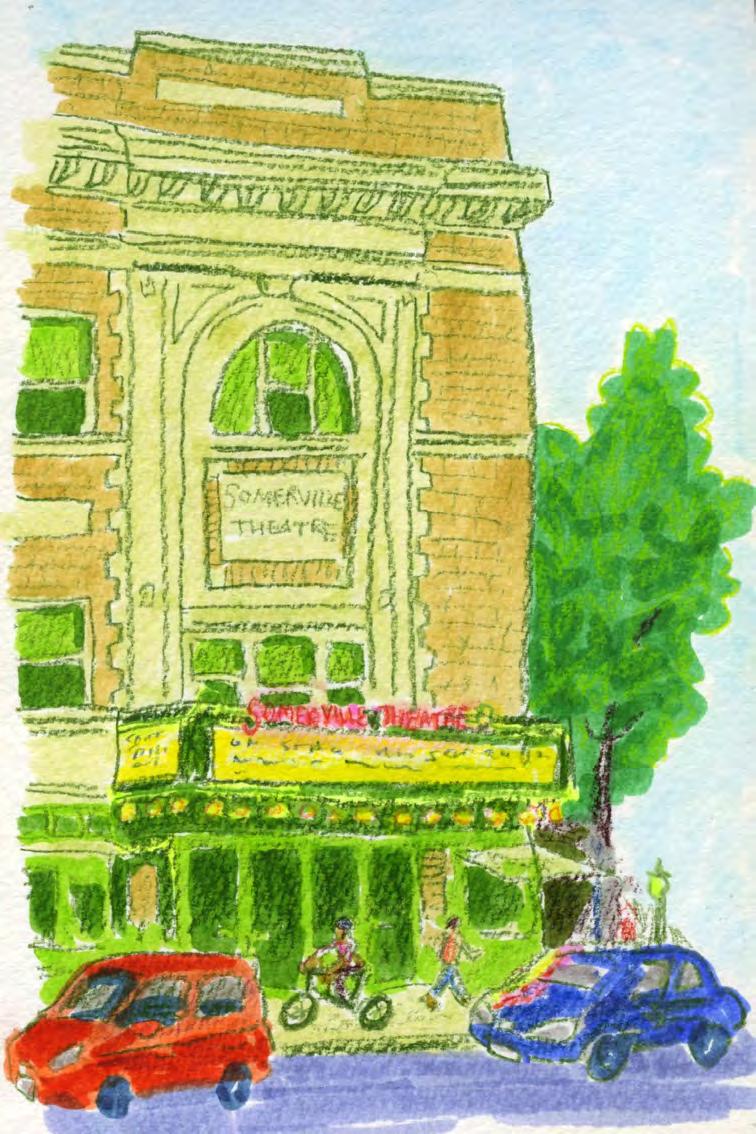

Indie theaters like Davis Square’s Somerville eatre are doing all they can to prevent that from happening, but attendance has waned in recent years. “[ e Somerville eatre] is one of the few the-

aters in America that still projects 70mm lm,” Film and Media Studies major and self-proclaimed cinephile Hannah Schuller explained. Films shown on 70mm have frames that are crisper, brighter, larger, and more uniform than standard digital projection. “It’s sad to see fewer people in attendance at these highly sought-a er viewings,” Schuller shared.

Recent movie attendance data reveals this decrease in attendance is felt by small and large theaters alike. AMC theaters experienced a 31 percent fall in revenue during the second economic quarter of 2024. Net losses for the multi-billion dollar movie theater chain during this three-month period plummeted to $32.8 million; a gure that nearly quadrupled the numbers from the same period in the previous year. Even arthouse cinemas that were once a hub for exploring avant-garde and underground

lms are dwindling due to decreased interest in going to the movies.

When examining this data, it is important to consider the impact of COVID-19 on both movie theater companies and individual lmgoers. During the pandemic, not only did the number of lmshowing attendees rapidly decrease, feelings of belonging and collectivity among Americans also plummeted, leaving one out of two adults facing loneliness and social isolation. In May 2023, the U.S. Surgeon General reported that Americans are facing an epidemic of loneliness, citing our increased dependence on the internet, technology, and social media as a cause of extreme isolation. A symptom of this epidemic is the drastic decrease of in-person interactions; striking up a conversation with a person on public transportation or the person bagging your groceries has

become a rare occurrence, one that is even unthinkable for some.

e mobilization of the internet allows us to occupy space in the public sphere without actively engaging with it because our private lives can come with us everywhere we go. Conversing with a friend via text or scrolling through familiar faces on Instagram while in public are prime examples of the blurring of these two spheres. We can be in public while actively engaging with the private happenings of our own lives on our smartphones. e sugar rushes of dopamine our brains receive when we look at our smartphones overshadow any desire we may have to fully immerse ourselves in public life. Why would you talk to that stranger on the train when you could instead submerge yourself into the events of your private life through a device that ts into the palm of your hand? To that end, why would you spend money to watch a movie in the cinema, next to a random stranger, when you could watch an entire movie on your phone in the privacy and comfort of your own home?

Proud AMC Stubs member, lm connoisseur, and Tu s student Mia Vassilovski passionately disagrees with the idea that watching movies at home o$ers viewers an adequate and holistic experience.“When I’m at a [movie] theater, I feel the unanimous excitement of an entire crowd of people who are here for the same reason as me–to engage in a true lm-watching experience.” Vassilovski also underscores the importance of the movie theater in removing all external distractions from the viewing experience, like her phone or laptop. “I feel a lot more engaged with a lm [at a movie theater] than at home… it feels like there’s really something at stake.”

Letterboxd, a social media platform for rating, sharing, and talking about taste in lms, has more than 13 million active users as of March 2024. is app’s following demonstrates that users still yearn for community surrounding lm; viewers want to know what their friends are watching and what they think of anticipated new releases as well as timeless classics. It’s just that users would rather wait for the inevitable wide release of blockbuster lms on the streaming platform they’re already paying for. e ubiquity of streaming services grants subscribers access to hundreds of lms per

month for the cost of one movie ticket, as well as the priceless ability to watch a movie from the comfort of your own bed.

What streaming will never o$er, though, is the aesthetic advantages of the theater experience, like ultra-crisp audio and larger-than-life screens. Similarly, the enjoyment of streaming movies is hindered by the lack of social interaction experienced by at-home movie-watchers. e social aspect of watching a movie in a crowded theater is one of the main factors contributing to one’s overall enjoyment of a lm. Malcolm Turvey, founder of Tu s’ Film & Media Studies Program and current professor of History of Art and Architecture, describes how viewers can experience emotions more intensely in a collective environment. Filmgoers “feed o$ other people’s reactions [to a lm] because we typically don’t experience emotions in an autonomous fashion, rather we experience them socially.” Laughter, he explained, is a prime example of this phenomenon; when we see or hear someone else laughing, it makes us laugh harder. e emotional aspect of a lmwatching experience becomes enhanced during the communal viewing that occurs in a theater.

ese kinds of intense, collective, and emotional experiences that lms have the power to create are dull, in comparison, to the instant grati cation we can get from checking our smartphones. To truly feel the emotions lms provoke, we have to choose to commit our time and attention to the public experience (and not our phones) for the entirety of a lm. eoretical physicist Micheal Goldhaber observed how the economy has become attention-based as a result of advertisers and tech companies capitalizing on the scarcity of human attention. e attention economy is doing everything in its power to turn this choice into an impulse–and thereby take this choice away from us entirely.

Apps like TikTok and Instagram employ algorithms that analyze viewing habits in order to show users other content that would be interesting and engaging, therefore encouraging more scrolling through both similarly tantalizing content as well as a plethora of advertisements. Advertising companies at large have been successful at captivating human attention, as the average

American spends four hours and thirtyseven minutes on their phones per day. e rise of screen time numbers decreases both our available time and desire to have collective experiences like watching lms. While the internet claims to unite us by allowing us to discuss if that dress was white and gold or blue and black, and laugh at the same video of that cop falling down a slide (how did he go down so fast??), Professor of Medical Sociology at the University of Manchester, Tarani Chandola, warns that collectivity on the internet is not a replacement for in-person experiences. He argues that the internet creates an atomized and intangible common reality that removes us from the real world, and too much time in the intangible world of the internet is dangerous. Studies have shown that poor or insucient social connection can cause vast physical health consequences, like increased risk of heart disease and even premature death.

Despite what technology and advertising companies want us to think, we do have the ability to put the phone down and experience social life in a real way—the movie theater is a prime example. By simply remembering the joy of being one of many in a full theater erupting in laughter or gasping in collective shock, you have taken the rst step in reclaiming your attention.

Writer, visual artist, and self-described digital minimalist August Lamm has written extensively about ways to reconnect with social life in her pamphlet titled “You Don’t Need a Smartphone.” Smartphones, she argues, are the biggest thief of collective experience. Lamm herself “downgraded” from smartphone to &ip phone, and encourages others to follow. is switch allows us to “reorient [our attention] around the present moment in [our] own life.” Lamm exempli es the fact that we have the capacity to regain our very human desire to nd beauty in real collectivity and connection in the public sphere. A movie theater is one of many places where we can go to experience these vital feelings of community. As Nicole Kidman said, “We need that, all of us.”

Why “Easy A” Classes are an F in US

From 6:00 to 7:15 PM every Tuesday and ursday last semester, I would sit in a lecture hall and watch my professor desperately try to engage a class of 300 students. Each week, I gazed out at the room as it slowly thinned. Every question the professor asked was met with resounding silence, except for the stray jingle that played when somebody nished e New York Times mini-crossword and forgot to mute their computer. Why show up when you can ll out the online attendance form from your dorm room? Nobody cared about his class. Why? Because it was an “easy A” natural science course, one that wouldn’t even count for an actual STEM major, and everyone, including myself, was doing the bare minimum. I do not want to shame people who take these classes. Personally, I’ve had plenty of fun thinking of creative nal projects rather than cramming for huge exams. Instead, I want to ask the question: Why the hell is this a part of my curriculum in the rst place? Aren’t there better things I could be learning?

William Deresiewicz’s Excellent Sheep touches on this subject and elite American universities as a whole. Deresiewicz highlights a key path in higher education—elite institutions end up sending students toward three main career paths: nance, consulting, and tech. Why is this happening? Imagine someone decided to pursue a career before going to college. ey ll their schedules with their major’s requirements. With more and more “easy A” classes, they can dilute their course loads and focus on two or three classes that help them graduate. ese classes fail to work as introductions to subject matters and rather come o as a glimpse of the department without any substance. How can you have an astronomy class

where you don’t learn or apply any math? With courses like these, there is nearly no chance of stumbling upon other subject matters worth exploring.

The purpose of modern-day liberal arts education needs to change. We shouldn’t have these “easy A” classes because they aren’t doing anything for anyone. Scrap ‘em.

In the United States, liberal arts has been the centerpiece of higher education since the 17th century. e Yale Report of 1828 summarizes the founding principles of a United States liberal arts curriculum as one that focuses on the development of a well-rounded education. e appeal of a liberal arts education is that students are able to diversify their knowledge by choosing from a broad range of unfamiliar subjects. Most schools that adhere to the liberal arts system happen to be smaller, private, elite universities. Now, however, it seems as if there is an opposite e ect at play, where students go to these universities and end up conforming to very specific and outlined futures. Yes, some people have genuine interest in these areas, but

why do they have such a gravitating e ect compared to other elds?

I have two theories. Firstly, these career paths are high-paying. School is expensive, and high-paying jobs make that expense feel more worth it. Ultimately, this is a rational decision—if I have the education I need, why not go into the highestpaying eld I can? Secondly, there could be a sense of accomplishment aspired to because certain jobs are publicly regarded as important and powerful. Philosopher Robert Nozick argues that people do things not because the things themselves actually produce pleasure, but because they like the feeling of wanting to do them and accomplishing that. It’s easy to see how this is possible. Maybe I like telling people I major in computer science more than I like actually doing it.

With the way things are going, it seems as if schools are falling short of their original goals. Is it time for a change? Perhaps the purpose of college should be to prepare young adults for their professional careers. ere are bene ts to both systems. Preparing for the professional world helps people actively contribute to their communities and societies. Liberal arts focus on knowledge itself and esteem the commitment to knowledge. But, with the gravitational pull that Deresiewicz describes, it seems as if the goal of liberal arts universities is headed toward that of professional preparation. Sure, institutions can label their systems as liberal arts and require a variety of subjects for graduation, but the reality is that the payo of an elite education nowadays comes from names and alumni networks. ese are valuable tools, but $90,000 a year is quite the price for a good network. is semester, I enrolled in a class that I hoped would be easy in order to ful ll my world civilization requirement: Law and

that I might not do as well in this class as I could have in an easier one, and if I want to do well, it will require much more time and e ort. On the other hand, I appreciate the subject matter and am glad to be taking a class that is forcing me to read and learn about a subject that has carried so much weight throughout human history. I want to be a lawyer and have read that the average undergraduate GPA for top law schools is about 3.85/4. While I am learning about a relevant subject matter, I am forced to feel as if this class is damaging my chances of getting in rather than boosting them. It would have been better for me to get a better grade in an easier class that I’d never think about again than a worse grade in one that might truly in$uence my intellectual application to the eld I aspire to join.

e purpose of modern-day liberal arts education needs to change. We shouldn’t have these “easy A” classes because they aren’t doing anything for anyone. Scrap ‘em. While classes like these might give students the occasional fun fact or conversation starter, they fail to educate us in the way higher institutions should, and in the ways stated in documents such as the Yale Report of 1828. Given the price that people pay for the opportunity to attend these schools, schools should be responsible for o ering an education on diverse sub-

jects that can be further explored based on personal interest. Currently, introductory classes tend to try and “weed out” students with heavy workloads, forcing them out instead of drawing them in. Instead of a random natural science class that sounds like an episode of Neil deGrasse Tyson’s Cosmos: A Spacetime Odyssey, o er a physics class that works as a true introduction, without the weed-outs and extreme workloads. Imagine a student who didn’t know they loved physics or chemistry taking one of these classes and discovering their passion because of an accessible introductory class. Instead of majoring in something that they might have enjoyed less, they are given the right opportunities and are able to nd their academic niche. At the end of the day, knowledge about these subjects is always more valuable than the college version of an educational TikTok page. Schools owe their knowledge-hungry students an education that can actually allow them to explore di erent elds without the burden of worse grades and less free time. We can’t expect every student to be an outstanding polymath, and we shouldn’t. Whether or not someone does well in physics isn’t what should be

By James Urquhart

important. What’s important is that everyone learns about a subject that is worth knowing. Everyone tries. In the end, I think everyone will bene t. As corny as it sounds, knowledge is important, it’s powerful.

As students and members of a higher education institution, we must turn our focus toward achieving a strong, diverse education. However, it’s important not to dump the burden on students. Academic institutions should spend more time teaching exactly what they argued was important when they laid out their founding principles, as Yale did in the Yale Report. How has not learning become the greatest advantage of higher education? Applicable, diversi ed knowledge should be the primary focus, and schools should cater to this instead of focusing on what happens a er graduation. Ultimately, if you want to focus on a speci c subject, the option should exist. But if, like me, you are attracted to the liberal arts philosophy, it should be worth it for the price. For that to happen, schools need to shi their focus and be dedicated to teaching students about key subjects without burdening them with the prospect of ultimately detrimental failure in the long run.

Again, I’ve taken so many of these “easy A” classes. I want to get good grades and go to graduate school. ese help, but they’re a big waste of time and money. Rather than lling your schedule with easy courses, take di cult, introductory classes across all elds. Find your niche. at should be the purpose of a liberal arts education.

By Kerrera Jackson

Who could you be, now that you aren’t surrounded by the people or places from your past? Going to college provides a fresh, new beginning to the rest of our lives; the opportunities are endless. You could make your personality all about your newfound love for math, dance, classical literature, or improv theater. You could dress di!erently, cut your hair, put on more (or less) makeup, and no one would know that that wasn’t you before you came here. But there is one thing that can pull you back to who you were before Tu s, before the possibil-

ity of reinvention was accessible. During those rst few nights standing on Tisch Roof, everyone gets asked the same question: “Where are you from?” is is something we have no control over, no ability to manipulate, even in a new location. Still, our need to perceive others persists. When meeting so many reinventions, we latch onto the one thing we know for sure.

I wasn’t expecting it when I came here: the pause, the glint of confusion in people’s eyes when I tell them that I’m from Minnesota. ey take a moment to see if they can remember where that

is, or suddenly realize that it’s a state in the rst place. ere’s the shock that I made it all the way over here, followed by polite conversation wherein they attempt to remember one thing, something, anything, about Minnesota. is can only happen for a second until they quickly move on to something else, something they’re more familiar with discussing. From these moments on, it’s always felt like I have to work upwards—from the disappointment and confusion I’ve caused them, from the vision that I’m from this unheard-of place, a blank gray slate where a state should be. What lls in this slate are stereotypical images of middle-of-nowhere farmland and tiny towns pretending to be cities.

My whole life I’ve been from one place: Bloomington, Minnesota (but I always tell people “Minneapolis”). I grew up a 10-minute walk away from the Minnesota River and the Mississippi a 10-minute drive. Not only did I have rivers to escape to, but waterfalls too, and a lake always a stone’s throw away. School got canceled for snow days but also for “cold days,” when it would get to -40ºF, and no one would bat an eye.

Not only is the nature beautiful, but the culture is too. “Minnesota nice” is a common phrase most people connect to my home state. It’s not just a saying, it’s a way of life. You pass strangers on the street, and you wave, say hello, and ask how their day is going. !ere is a sense of greater community there that I miss when walking on these gray Bostonian streets lled with blaring car horns and turned-down faces. Our music scene is also something I miss—there’s nothing Minnesotans know how to do better than show out at live music. If I wanted to get a decent view at a show I had to line up by 4 pm, even on a weekday, with the line already trailing down multiple blocks. I grew up going to the Dakota Jazz Club with my parents and later graduated to hot and sweaty shows at First Avenue, an iconic venue where Prince got his start. When I think of home, I think of those late nights in the city, where time felt endless—where it felt like I would never leave. I’ve never moved homes, let alone states, and like almost everyone else, I’ve never thought about what it would be like to be from somewhere else. Where else could I even be from?

But when I came to Tu s, I started to ask myself this question—or better, where else might people see me as being from? What if I lied about it so that I could feel like I t in more here? I started to make people guess. !e classic answers always appeared: New York? L.A.? D.C.? Maybe this was just a way of delaying it, though: the reaction that always followed, the reaction that even the humor of the game can’t fully cover up, a game I made so I can feel connected to them for a little bit longer.

Every chance I get, I sprinkle some facts about Minnesota into conversation.

“Minneapolis has an incredible food scene.”

“I live super close to the Mall of America, the largest mall in the country!” “We have a ourishing art scene, like did you know that Keith Haring had a long residency at the Walker?” “Did you know that Prince is from

there? Bob Dylan? Winona Ryder? Judy Garland?” I’m from there, isn’t that enough?

But these reactions also mean presumption. It’s human to immediately ll in the blanks when key data is missing, but what’s lled in are assumptions—that it must be uninteresting, that it must not be worth their time. My stomach sinks, and it’s hard not to go quiet, to feel numb at the mercy of the perceptions of what people think my life was like before coming here.

My experience is not a singular one, it’s something I talk at length about with friends from other “unmemorable” places. !at is something that I am grateful for, though: the community that being from a place Tu s doesn’t normally encounter brings. Every time I meet someone from Kansas or Wisconsin or South Carolina, I jump at the opportunity to tell them that I’m from somewhere uncommon too, something that we share.

!ere’s an assumption being made by Dake’s friends when they say they don’t want to visit his home in West Virginia. He tells me that he would love to experience his home with the people from Tu s that he cares about. But he knows that they will never want to visit. I beg my own friends from Tu s to come and visit me every summer, and every time I get the same response— a polite smile and quick a rmation that they’ll “check the ights.” !ere’s an assumption being made when I get asked if I’m glad I le home, like being in Boston has saved me from a dreary and boring future, like I can’t love where I’m from just because they don’t know how.

!ere’s an assumption being made when someone asks Eleanor, a lesbian from Alabama, if she’s ever been “hate crimed,” or when her dad gets told that he’s “just a doctor from Alabama,” like if he was a doctor in New York he’d automatically be smarter. A caricature is easy to remember, but the reality of a diverse and multifaceted place is not.

!ere are painters from Iowa, musicians from Louisiana, and philosophical theorists from North Dakota. !ere are trans people in Oklahoma, aspiring lmmakers in Utah, and schoolteachers in Ohio trying to build a brighter future. !ere are pride parades in Arkansas and musical theater scenes in Indiana. !ere is so much joy, so much culture, and so much life in places people don’t expect it from.

But then again, what if there wasn’t? What if there were only farmers, factory workers, or non-college-educated people in these places? !ey aren’t any less deserving of your time, respect, or consideration. We single out what we perceive as interesting, instead of recognizing the complexities of other’s lives. We only accept our experiences, or our perceptions of the world, as the “correct” ones.

“People automatically assume that everyone in West Virginia is someone that would disagree with them politically, and I wish people understood that you don’t have to discount a whole state just because of your perception of what they believe,” said Dake. It’s easy to make perceptions based on a place’s politics, and there is so much to say about the political climate of where someone is from or why they wouldn’t want to move back there. But boiling their lives down to just that does a great disservice to their homeland, the place that raised them and that they can still hold tenderness for. !e thing is, can I even blame them? To what extent can any of us actually ever understand each other, before we all melted into the same liberal arts school pot? Someone who grew up in New York City can’t understand my life before Tu s, and I can’t understand theirs. I can’t understand what it was like for Dake to grow up in West Virginia; I have my own presumptions about that, too. But what I wish for, and what I think we all wish for, is an attempt to understand, to not be thrown away.

“I’m very proud of where I’m from, and that has to do with a lot of my personal growth and my relationship to where I’m from. At the beginning… I felt ashamed of where I was from. I was really trying to not have any kind of Southern accent, and I was really trying to push that down. I didn’t want people to know that I was di erent. But I don’t at all anymore, and I regret having that shame… A lot of who I am is dependent on where I came from, and I don’t want to lose that,” said Eleanor.

I will never lose the way I elongate my O’s when I get excited, my constant Minnesota fact-dropping, or my life in the Midwest. We can’t change where we are from, we can only change our perceptions of it, and we can all accept that there is so much more to the world, to this country even, than we think we know.

It’s 2013. You’re in the checkout line of Stop & Shop, sorting through gum, Milky Ways, and dozens of celebrity tabloids as you wait for your mom to pay. !e headlines read something like, “Too Young For Surgery: Surgeons Reveal !eir Star Clients!” and “Plastic Surgery Shockers!” or “Kardashians: Destroyed By Vanity?” You ip through the pages, turning your back to your mom so she doesn’t see you gawking at the scandalous photographs and raunchy stories. !ere’s just something disturbing about it all that makes you unable to tear your eyes away.

Before the social media boom, celebrity culture used to revolve around tabloids, paparazzi, and A-list movie star millionaires. !e hottest gossip was knowing exactly which celebrities got work done and how. It was like a game: who could

expose their secrets the fastest? Even into the early 2020s, people debated whether Madison Beer got work done and wondered: why on earth was she lying about it?

With the age of tabloids fading away, the real problem many young girls and teens face now is more complex. !ey have to ght comparison battles with not only their classmates, but also the very relatable, attainably pretty, “normal” celebrities of the digital world, some of whom are only months older than them. Celebrity content and culture are nowhere close to where they used to be, all because of the new wave of social media.

Back then, conversations I heard about celebrity culture always centered around the dangers of comparison to celebrities because of their unrealistic beauty standards. Parents, teachers, and other adults in my life constantly told me that young girls should not judge themselves against celebrities because they can a ord to augment their bodies in a way that society deems “perfect.” !ey seemed so terri ed that a young girl would see a celebrity with a boob job and immediately feel poorly about their own pre-pubescent body.

As a tween, the incessant preaching about plastic surgery stood out to me because it felt like the wrong conversation to be having. Of course, major celebrities would always look more “perfect” than regular people—

they had the money, the fame, the expectation. I didn’t care about them. I wanted to know how to stop comparing myself to the girls in my own grade. It was these girls, the ones who had a life comparable to mine, who I measured myself against. I didn’t care what any celebrity looked like. It was the girl who sat next to me in math class and the one who played soccer with me on Saturdays who I was jealous of. !e e ort spent shielding young girls from celebrity-driven insecurities would have been better directed toward helping us navigate peer comparison issues. !e real problem young girls and teens face now is more complex. Catalyzed by the rise of TikTok, this demographic now closely follows social media in uencers and less so A-list celebrities. Consequently, they have to ght comparison battles with not only their classmates but also with the “normal” in uencers who curate their platforms as relatable and attainably pretty, with clean and beautiful lifestyles that are within reach if you just put in the work to get there. While the Kardashians' excessive lives may have felt too distant for young people to relate to, this new wave of in uencers feels so accessible that they open the door for easy comparison.