Editor-in-Chief

Veronica Habashy

Editor Emeritus

Emara Saez

Co-Managing Editor

Miles

Creative

Unmani Tewari

Feature

Staff

Billy

Joyce

Kate Weyant

Danielle

Alec

Siena

Publicity Director

Francesca Gasasira

Mia Ivatury

Publicity Team

Madison Clowes

Sophie Littman

Emilia Ferreira

Carson Komishane

Staff Artist Isabel Mahoney

Phoebe McMahon

Avril Lynch

Ruby Luband

News

Designer

Rachel

Arts

Sofia Valdebenito

Opinion Editor

Megan Reimer

Mia Ivatury

Campus Editor

Chloe Thurmgreene

Rohith Raman

Poetry and Prose Editor

Ivi Fung

Peaches Wright

Voices Editor Emma Castro

Max Greenstein

Art Director

Ella

Erin Gobry

Dana Jeong

Ahmed Fouad

Joey Marmo

Felix Yu

Lead Copy Editor

Caroline Lloyd-Jones

Talia Tepper

Copy Editor

Wellesley Papagni

Henry Estes

Alison Tsai

Oyinkansola Akin-Olugbade

Lucie Babcock

Isabella Tepper

Amena Weiffenbach

Ella Hubbard

Elika

Felix Yu

Maria Sokolowski

Leila Toubia

Website Manager

Dylan Perkins

Andie Cabochan

Treasurer Andrea Li

Crossword Editor

Max Greenstein

a vast expanse, vertiginous darkness, blacker than it should be/ unprompted shiver/ the sudden feeling that something (someone) is missing/ it’s a twin, and then another twin where you didn’t know there would be one/ haven’t I been here before?

By Amanda Alatorre

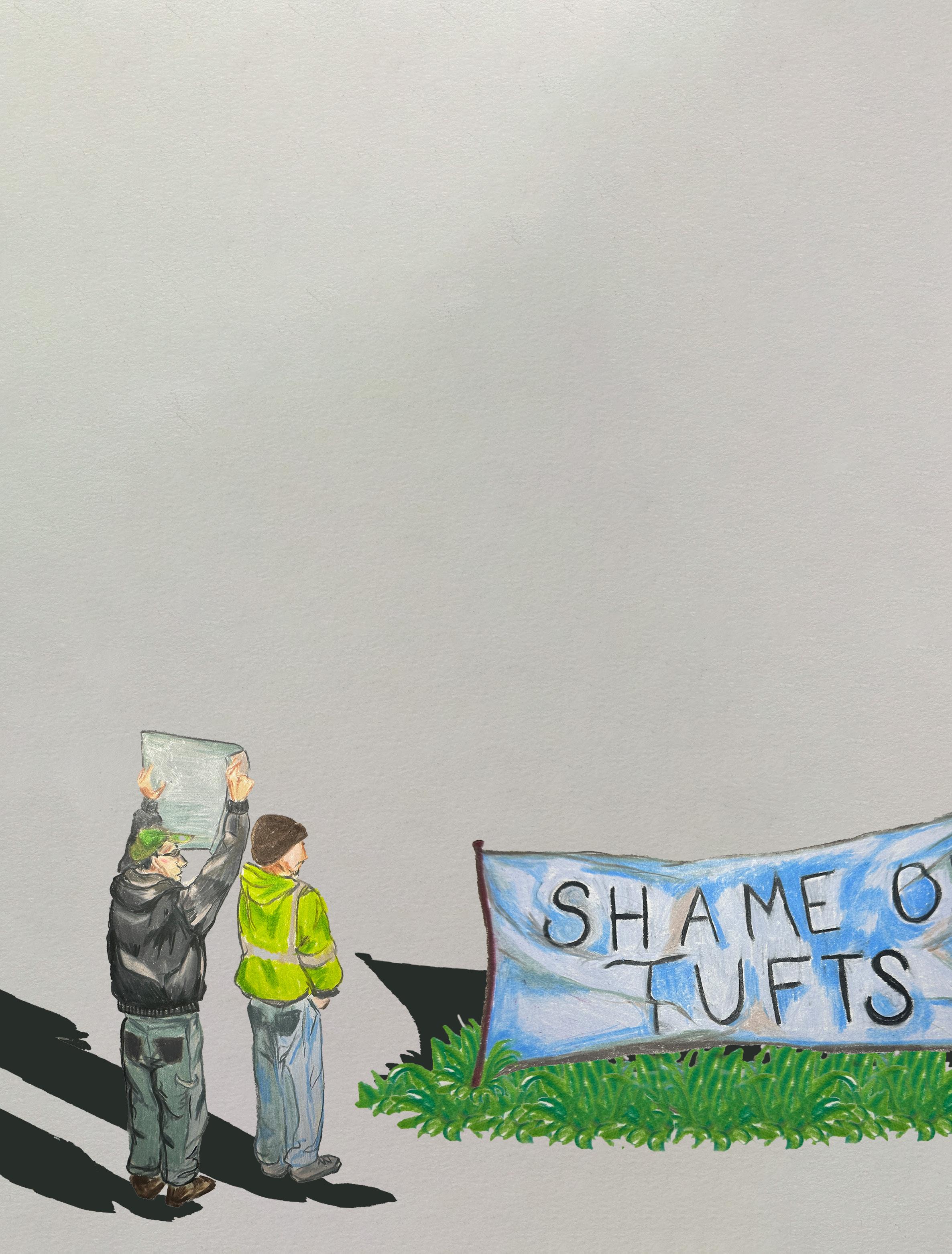

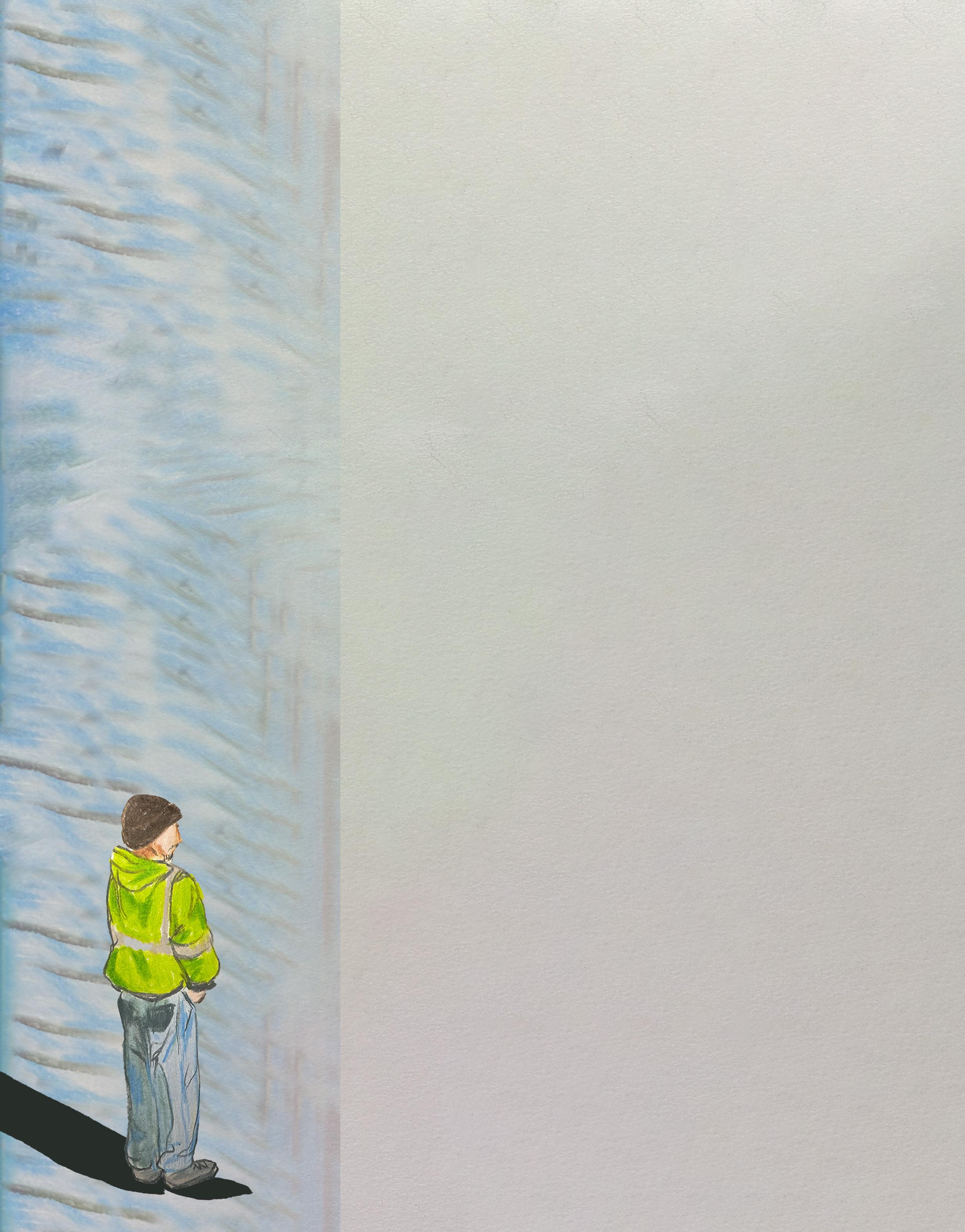

On October 18, members of the Carpenter’s Union, alongside supportive students, filled the streets with noise, holding posters high and marching down College Ave with electrifying energy. The protest, organized by the North Atlantic States Regional Council of Carpenters (NASRCC), mirrored similar demonstrations held on August 23 and 28 of this year when first-year students arrived on campus. Their presence was a reminder to the Tufts community that their struggle for fair labor practices persists, months after it was first brought to the University’s attention.

According to their mission statement, the union advocates for fair wages, safe working conditions, and comprehensive benefits for carpenters across the New England region. They have consistently alleged that Tufts engages in unethical labor practices by hiring contractors accused of wage theft and not employing union-affiliated carpenters.

According to flyers distributed at their protests, “some of the general contractors selected by Tufts to manage projects on campus, such as

Dellbrook and Windover Construction, have a history of hiring subcontractors that… engage in practices that do not comply with [labor ethics] laws.”

The NASRCC Director of Organizing Noel Xavier explained that Tufts has primarily done business with responsible unionized contractors in the past. However, the standards of contractors employed by the University have deteriorated in the last five or so years.

According to Xavier, the general contractor Dellbrook, which was recently employed to build a structure at Tufts, “predominantly uses subcontractors that use these second, third tier subcontractors that do all this cheating all the time.” He went on to emphasize the excessive number of levels that may exist between the general contractor and employee in construction.

“You have the general contractor that manages the construction site,” Xavier continued. “He hires all the subcontractors that do all the different scopes of work. So he’ll hire the concrete subcontractor, the framing subcontractor, the drywall subcontractor, the flooring, the finish, the painting, the plumbing, the electrician.”

Due to its lack of regulation, construction has historically been a field heavily disposed to unfair labor practices. With so many different levels of management between contractors and workers, it becomes increasingly difficult to hold anyone accountable

for malpractice. “There’s no incentive for a general contractor right now to really regulate who they hire, because they’re not on the hook for anything that goes wrong,” Xavier said.

This unregulated system results in workers being denied benefits or even instances of wage theft. “What happens is the prime subcontractor pays the second tier. The second tier guy pays all these [carpenters], typically in cash… There’s no payroll check with the state, taxes, federal, all of that they’re not paying, insurances that they need to [have] by law.” The practice of using cash payments allows employers to evade labor laws and underpay their workers, given that the transactions are off the books. This can quickly morph into the economic exploitation of workers, many of whom are already vulnerable, such as undocumented immigrants.

“It’s really an immigrant-heavy industry, construction,” Xavier said. “A lot of these workers are also undocumented, so they don’t really know their rights. They feel scared sometimes if they’re going through wage thefts, if they didn’t get paid, or if they’re working 60 hours a week.”

In a physically grueling field like construction, the implications of not having insurance or employment benefits are particularly dire. A study conducted by the University of Michigan found that “migrant construction workers … face higher fatality rates, safety incidents, and

discriminatory practices … in part due to a failure of safety training for immigrant workers, a failure to bridge multicultural workforces, a large separation from authority figures on site, and the reluctance and improbability to receive workers’ compensation or medical attention for work-related injuries.”

The union tries to counter those contractors that evade certain prerequisites for labor by offering comprehensive apprenticeship programs. These programs, according to Xavier, provide high-quality training to hopefully minimize safety risks by equipping workers with the knowledge they need to stay safe. But there is only so much the union can account for. In the construction business, workers may only work to a certain age because of the physical demands. When they are no longer able to work, they are often left without retirement benefits and social security protections, leaving them with a meager source of income or none at all.

Because of the various levels of power imbalances in construction between workers and contractors, the rights of nonunion employees are ill-protected. Xavier recalled specific instances of wage theft the union had encountered, “We just ran into a couple of cases in Portland, Maine, where about 22 workers haven’t been paid in a month of doing wood frame and we’re helping them recover the wages.” These cases of exploitation are pervasive in the construction industry. “There’s another project here in the Boston area where 13 workers came forward, [they] haven’t been paid in five weeks, and we’re helping them through the process with the right agencies, [to] file the right paperwork, and trying to get them paid,” Xavier said.

In expressing the University’s sentiment toward unions, Tufts’ Vice President of Operations Barbara Stein affirmed that the University values unions.“Tufts has a deep respect for labor unions,” Stein wrote. “We have several unions at the university and continue to cultivate strong and productive relationships with each one.”

Stein further emphasized that Tufts is not responsible for the hiring choices of their contractors. “For its construction projects, Tufts hires general contractors who are responsible for hiring the trades that perform work on the projects,” Stein

wrote. In other words, Tufts does not regulate who their contractor chooses to hire to complete the project. Despite this, Stein claims that the University makes an effort to hire responsible contractors. “Tufts works with many vendors and contractors, and pays close attention to vetting, hiring, and engaging with these third-party companies,” she wrote.

“[Tufts has] a specific type of power at this institution, and we can leverage it by making it clear to the administration what we will not stand for.”

Xavier acknowledged that these cases of exploitation didn’t occur on Tufts property. However, he explained that the contractors the University hired are notorious for these practices around Massachusetts, which should hypothetically be flagged by the University. “Any contractor that does work on campus knows that they are under scrutiny from the University, from organizations like ours,” Xavier said.“But these same contractors are doing jobs all over Massachusetts… In all these projects, they use the same characters, the same contractor, the same subcontractors that typically cheat all the time, cheat the workers.”

The NASRCC is calling for Tufts, as an academic institution with significant influence, to assume a leadership role in reversing this trend. By ensuring ethical labor practices and exercising their power to influence other universities, Tufts can set a precedent for how construction workers should be treated.

“For a university that should be standing up for what’s right,” Xavier

said, “[Tufts should be] making sure that contractors on site are just as responsible and great as the university itself.”

A member of the Tufts Labor Coalition, Junior Ananya Khedkar, agreed with this sentiment, saying in a written statement to the Tufts Observer that “as a student group dedicated to standing in solidarity with workers, we believe Tufts has a responsibility to commit to fair labor practices, and embody the values of equity and justice that the institution claims.”

Beyond protesting and harnessing the support of student groups like TLC, the union has made several efforts to meet with Tufts President Sunil Kumar, but to no avail. “We’ve had conversations with folks at the University about [the union’s concerns], and we haven’t really gotten anywhere,” Xavier said.

When prompted about the union’s concerns, Stein responded that the university itself does not engage in unethical labor practices with its employees. “The [NASRCC] does not represent any university employees, and the University is not a party to any collective bargaining agreements with this union,” she wrote.

Stein also outlined the University’s criteria for selecting contractors.

“In making its final determination,” she wrote, “the university considers approach, ability to meet the project schedule, ability to maintain a safe work environment, compliance with laws and regulations, and other factors. And, in recognition of its fiduciary obligations, it chooses the lowest-cost, qualified contractor.”

Xavier acknowledges the University’s concern over budget. However, he argues that, in the name of financial concern, ethical labor is the first thing to go. “Materials are what materials are,” Xavier said. “Doesn’t matter if you’re union or non-union, materials cost the same.” When Tufts chooses a lower-cost non-union contractor, the low cost has likely been derived from contractors that “cheat” their workers.

There is recent progress with Tufts’ stance on labor issues. Previously, the University had accepted a new contract for graduate workers that included significant pay raises, improved health

and safety protections, and parental leave benefits. Tufts was the third university in the country to accept demands from a graduate student union, and other colleges soon followed suit. This case confirms the national influence that Tufts can exercise through its leadership as a prestigious academic institution. Khedar echoed this sentiment, writing that “[Tufts has] a specific type of power at this institution, and we can leverage it by making it clear to the administration what we will not stand for.”

Xavier and the union believe that there is much more work to be done. The protesters and their supporters are urging Tufts to adopt a policy of hiring responsible contractors with respect for unionized labor, thereby taking a stand against wage theft and unsafe working conditions. By doing so, they argue, Tufts can influence labor practices not just locally, but across the academic and construction industries. “At the end of the day the university has a legacy,” Xavier said. “And do they want to be a part of a legacy where everybody wins or just where the university itself wins?”

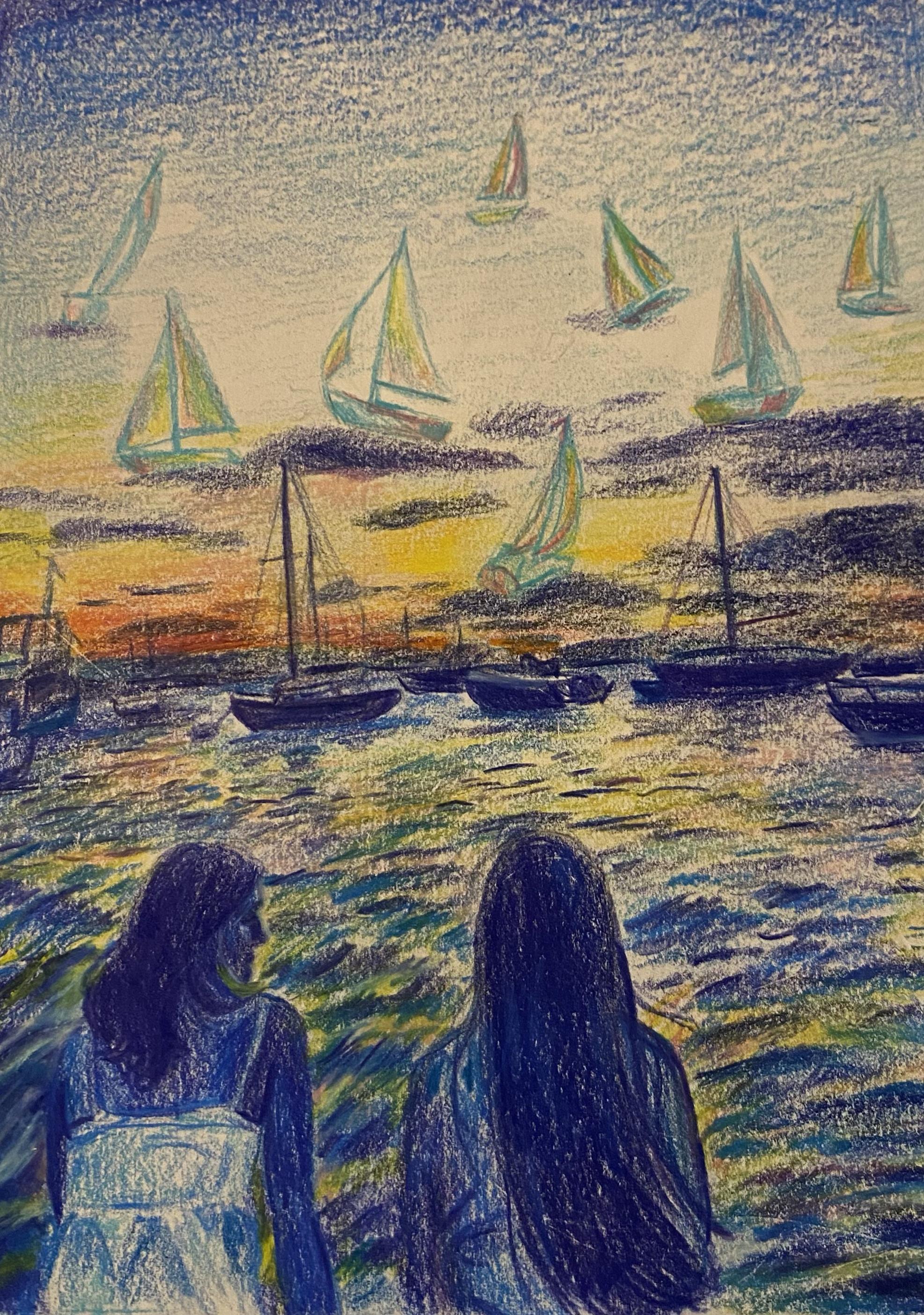

By Lucie Babcock

Ever since 5:05 p.m. on September 19, 2005, I’ve been a twin, a fact that always leads to wide-eyed questions: Are you identical? Nope. Moving on. Who’s older? Me, by a very slim margin that I nonetheless use to victoriously claim the title of Older Sibling every chance I get. Do you have twin telepathy? As if I would tell you if we did. And then, with either an envious or suspicious look: What’s it like being a twin?

I never quite know what to say to that one. It feels wrong to claim to be the mouthpiece for the millions of twins across the world when I only have a meager nineteen years of experience with my one twin. The truth is, I can’t really tell you what it’s like to be a twin, I can only tell you what it’s like to be my twin’s twin—which is a bit about me and a bit about Ryan and a lot about the spaces we grew up in together.

I can tell you that in elementary school, my parents issued a proclamation that both of us were required to act in the yearly talent show at least once, in a well-meaning attempt to get us to branch out. I had been in a dance routine, another dance routine, a skit, a homemade drum circle, yet another dance routine, and by sixth grade, I was ready to cap off my career in the coveted role of Emcee. Ryan, meanwhile, had been in absolutely nothing. My parents informed him that that year was his time to shine, or else. Despite the myriad of Acts That Are Just Mildly Okay

Enough to be Relatively Enjoyed by the Audience I had so helpfully demonstrated over the years, Ryan wasn’t called to show business through any conventional ways. Instead, he chose an act that had really and truly never before graced the talent show—he walked out on stage with a scrambled Rubik’s cube, dramatically displayed it to the crowd, then dropped to the ground and proceeded to solve it while doing sit-ups as Imagine Dragons’ “Thunder” blasted through the auditorium. When the feat of abdominal exercises and cubing had been completed (in under the 90-second time limit), he got up, showed off his solved cube, and walked off the stage without a word.

Competition was always like that between us. Bereft of even the thin line of age to shield us from direct comparison, we protected ourselves by doing wildly different things so that there were no chances to hold up a measuring stick. It wasn’t about picking a winner, but knowing that a spotlight diffused on both of us would never shine as bright as it would on a solo. I wonder, sometimes, if I would have picked volleyball and books if Ryan hadn’t picked football and math, but then I remember that in a universe without Ryan I wouldn’t be the same person at all anyway.

I can also tell you about high school football games, where I’d stand packed shoulder to shoulder on the rickety metal bleachers of the student section and cheer along with everyone else when Number 27 took the field as the kicker (the only position our mom would let Ryan play). It’s surreal, hearing your own last name shouted by people you’ve never met through the haze of colored smoke and waving pom poms and mingled perfume. I didn’t exactly pay attention to the rest of the game, but if the idiots on the bench in front of me ever started to boo I was quick to shout over the roar of the crowd that “he was supposed to kick it like that! It’s a new kickoff!” Even if football was Ryan’s thing, it was mine by association, and watching a perfect field goal soar through the uprights always filled me with pride.

I can tell you that for every single day of our senior year, Ryan played the exact same two songs in the car on our drive to

school. There wasn’t a dawn I didn’t greet without “Temperature” by Sean Paul and “Glorious” by Macklemore. And as much as I bemoaned his music taste when it was 7 a.m. and I had a test in 30 minutes, the first time I heard “Temperature” at 2 a.m. in a crowded college basement, I was the only person to burst into tears from the sound of reggae rap.

I can tell you that when I bingewatched Gilmore Girls during COVID, Ryan spent approximately half an episode looming in the corner of the living room and pretending not to watch—and then the entire rest of the seven seasons sitting beside me and loudly debating the merits of each love interest. Quarantine was like an extreme melting pot of our different hobbies. I probably would never have wanted to know so much about video game controllers or the founders of Facebook, but it was interesting because Ryan thought it was interesting.

I can tell you that we’ve never looked alike, but it would still shock me when the girl I sat next to for an entire semester showed up to class and told me she only just figured out that we were twins. Sure, the only obvious clue was our last name, but I always thought it was somehow written into my appearance: brown hair, green eyes, twin. In college, where there’s not even the slightest chance of anyone knowing Ryan, it feels like everyone should anyway. Trying to adapt to being one instead of half a set of two feels a bit like being startled by a fresh haircut in the mirror.

I can tell you that when I came out to him while driving to school (guess what song was playing?), he just said “uh-huh” offhandedly and flicked the turn signal on. When I overcame my sweating palms to demand more of a reaction, he shrugged and said, “Oh, my B, I thought you were, like, leading up to something more exciting.”

I can tell you that when I was lying awake in May and trying to decide if I could really move across the entire country in the fall, he was contemplating the same thing. And I can tell you that I never considered not taking the train to Philadelphia for the weekend of our nineteenth birthday, even though it was six hours

there and six hours back and my foot fell asleep at least three times in the cramped train car. We walked around his campus and waved at all his friends I’d never met, and for once I missed the days of hiding upstairs because his middle school friends I knew too well were having a ping pong tournament in our garage. I missed knowing names and faces, now I was struggling to match them together.

And okay, I realize, after all of that, I haven’t actually answered the question I set out to answer. I can’t tell the entire story of being a twin in a few paragraphs, because I can’t condense the entire story of my life into a few dozen sentences. There isn’t the faintest childhood memory without Ryan—not a single inside joke or constantly-quoted movie or shaky home video or solitary moment of my life (except the very first minute) that doesn’t have his fingerprints all over it. I get it, it’s easy to shrug and say that’s just the same as having a regular sibling—I can’t refute that without employing some shaky metaphors, but I’ll give it a shot.

For every part of me, Ryan is the matching part—not the sharp teeth of puzzle pieces but a smooth meshing—like the crust of the earth reshaping under a glacier. We always mirrored rather than copied: where I scribbled wild fantasy stories, he added all the jokes. I lived for history class, while he loved math (our parents used to joke that if only we could take the SAT together, we’d get a perfect score). I don’t think you can ever really understand who I am without understanding who Ryan is, understanding how the valleys in my psyche are the mountains in his, understanding who we are together and who we are apart and everyone we’ve ever been. As I’m working to reconcile myself to the first fall we haven’t slept under the same roof, I’m starting to give a different answer to the age-old question we’re tired of hearing.

What’s it like being a twin?

I don’t know. What’s it like not being a twin?

By Alec Rosenthal

Within a sea of chest tattoos lies a portrait of La Virgen de Guadalupe, a depiction of the Virgin Mary associated with international gang MS-13. Bearing this image on his body, El Salvador citizen and green card applicant Luis Acensio Cordero was barred from obtaining his US Visa, which prevented Asencio from reentering the US, much to the dismay of his wife, American citizen Sandra Muñoz. Contesting this decision, Muñoz filed a lawsuit against the government, arguing that her right to marriage and family life was violated, a liberty constitutionally guaranteed under the Due Process Clause. However, on June 21, 2024, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of the government, a partisan decision that fundamentally weakened the legal understanding of the right to marry, creating cracks in previous verdicts such as Obergefell v. Hodges (2015) and Loving v. Virginia (1967) that have broadened the institution of marriage and diversified the image of the American family. This regressive stepping stone cemented by Department of State v. Muñoz mirrors larger-scale efforts by American conservatives to restrict personal autonomy, limiting the right of the individual to enact national sociocultural change in favor of the nuclear family.

While June 26, 2025 will mark 10 years since Obergefell, the Supreme Court decision that nationally legalized same-sex marriage, such a landmark falls in firm contrast to national discussions about the place of queerness in society. The queer identity exists in opposition to the right’s alignment with the nuclear family as a “moral” construct. The concept of the nuclear family emerged in the 1950s and entails a white, heterosexual union and their biological children—a standard perceived by 75 percent of Americans to be the predominant form of US families, according to an HP Inc. study from 2018. In contrast, only 25 percent of American families actually embody this conventional stereotype. This discrepancy between representation and reality, noted by 80 percent of participants, demonstrates the weak hold of such an exclusionary concept of family on the diverse population of the US, especially when considering marriage’s legal restructuring within the past 56 years.

Constitutionally protected changes to the right to marry have reshaped the institution of marriage and broader familial frameworks. Formerly, these structures operated as an engine for the systematic enforcement of a heteronormative, racially divided society. As an evolved legal prin-

ciple, the inalienable human right to marry without limitation is a defining aspect of the modern American sociocultural atmosphere. Freedom itself is inextricable from the American foundation. This inevitably conflicts with the traditional notion of the nuclear family. We as Americans must abandon the concept entirely and actively resist any alterations to this fundamental right. While only indirectly impacting the right to marry, Muñoz embodies a larger conservative movement that aims to use the revocation of rights under the Due Process Clause to enforce sociocultural control, through the implementation of legislation and targeted language that places queer Americans under a lens of immorality.

Regarding the beliefs of the American public, this culture war seems fruitful for the right: from 2021 to 2023, the GOP underwent a 16-point decline in the percentage of Republicans who would define same-sex relations as “morally acceptable,” a shift that parallels the introduction of trans-restrictive and anti-queer educational legislature across the nation by conservatives. Legislation such as Florida’s “Stop the Sexualization of Children Act” and other subtle swipes against Obergefell such as those by Justice Samuel Alito since 2020 exemplify a strengthening resistance

to LGBTQ+ equality in America, working alongside GOP mischaracterizations of queer Americans to orchestrate a backslide of acceptance.

Half of US adults believe that having fewer children produced by two-parent households will negatively impact the country’s future. While Americans are generally tolerant of different familial structures, it is still a partisan issue, especially when children enter the conversation. 64 percent of Republicans completely or somewhat accept gay and lesbian marriages, with this figure reducing to 41 percent for queer couples with children. This drop can in part be explained through the context of these national debates over the morality of queerness, flipping efforts to reduce LGBTQ+ stigma for youths through social, political, and medical avenues on their head. Conservative figureheads such as former President Donald Trump and Florida Governor Ron DeSantis misrepresent gender and sexuality awareness as child abuse and sexualization, restricting educational and medical outlets for queer youth self-expression in ways that completely contradict practices that actually benefit their mental and physical health. In this sense, it is clear that these conservative leaders do not care about children but rather use the idea of the child to exert control over the American populace.

Increasing contention over the queer identity and queer bodies within the po litical sphere originates from an American fascination and cultural attachment to having children, with the symbol of the child often dictating greater sociopolitical phenomena. This concept, titled “reproductive futurism,” as defined by queer theorist and Tufts Professor Lee Edelman, declares that our culture regards queerness as undignified due to LGBTQ+ relationships’ inability to produce biological children, which reduces queer sociocultural importance to an obstacle in relation to a productive cisheteronormative society. The expectation of reproduction restrains individual freedom as a foundational piece of our society’s structure, not only limiting the path of the queer person, but imprisoning all

individuals within a narrow, gendered definition of purpose. Politicians such as Vice Presidential Nominee JD Vance publicly espouse such principles, promoting a pronatalist agenda through critiques of “antichild ideology” and declining birth rates.

Under a heteronormative framework, the widespread social appraisal and acceptance of the nuclear family infects the individual with a personal impetus to assimilate into a cisheteronormative society. Within this understanding, movements for marriage equality find themselves intrinsically attached to a traditional concept of the family. Same-sex marriage adopts a

questionable position either as an assimilatory submission to marriage as a broader heterosexual practice or a progressive embrace of queerness within a traditional format. However, any queer marriage is inherently unfit for traditional notions of the nuclear family. Even beyond this lens, the diversified vision of the family misaligns with its traditional application. Hence, we must not only abandon the notion of the nuclear family entirely, but we must further eliminate the unconscious directive of the family.

Of course, it is easy to say we must abandon this construct, yet it is difficult

to actualize this. Changing familial structures, among other factors, have brought the US birth rate to its lowest level historically, a trend that could produce negative long-term economic repercussions. While the greatest effects of this phenomenon will not be felt for decades, issues such as an increased cost of living and a diminished labor force are symptomatic of disillusionment regarding the family as an essential or obtainable structure. In this sense, when establishing a family, actively creating non-traditional familial structures can also create issues that might necessitate a reexamination of what abandoning all notions of traditional familial structures truly entails. However, this does not grant the government the right to impose alterations on individual freedoms in the form of marital limitations, which do not resonate with modern American ideals.

In its finality, Muñoz acts as a silently significant watershed in the American struggle for personal autonomy, pushing precedent out the window and prioritizing conservative ideals over individual rights. For conservatives, the tradition of the nuclear family acts as a blueprint for their idealistic vision for America, devaluing those who may not contribute to a natalist culture. Etymologically, the nuclear family finds its roots in the idea that each member of the familial unit is essential, a representation that automatically others non-conforming families, implying that they lack completion. With other recent changes to our constitutionally protected personal freedoms, such as Roe v. Wade’s overturning in 2022, it is more clear than ever that autonomy has no permanence and one’s rights are always at risk. However, with the knowledge that the majority of the current American population is incompatible with these traditional ideals, we can collectively embrace our own disruption of the cisheteronormative order.

By Ishana Dasgupta

Everyone has, at some point or another, been told that they bear somewhat of a resemblance to a Clist actor or influencer. Usually meant as a compliment (although sometimes backhanded), this common phrase exemplifies people’s obsession with the concept of the celebrity doppelgänger, a mechanism in which we can put others, and ourselves, into a predetermined box of who they are, or who, ideally, they could be one day.

But why do we seek out these doppelgängers with such fervor? What drives individuals to base their sense of self on socially accepted figures, or to mold their personalities around celebrity trends?

The word doppelgänger originates from mid-nineteenth-century German folklore, and meant “double-goer” or

“double walker,” but its meaning in English has changed over the years. Throughout history, seeing a doppelgänger generally meant seeing a ghostly double of a living person, especially one that haunts its fleshy counterpart. These apparitions, which many famous historical figures claimed they saw, were a harbinger of bad fortune, signaling the death of who they appeared to be. Abraham Lincoln, Catherine The Great, and Queen Elizabeth I all claimed to see their doppelgänger shortly before they died. There are many historical claims that Elizabeth saw her “pallid, shivered, and wan” doppelgänger lying in a corpselike state on her bed in her chambers. Despite Elizabeth being level-headed and mentally stable, she appeared to know that something bad would happen when she

saw this. A few days later, the sixty-nineyear-old Queen Elizabeth I, who reigned for forty-five years, passed away.

So why would anyone want a doppelgänger, much less seek one out? The word doppelgänger, today, is used to describe more of a ‘twin stranger’ or individuals who bear a striking resemblance to one another despite having no familial connection.

While humans have always had a fascination for doppelgängers, with the advent of artificial intelligence and the ubiquity of social media, this fascination has evolved into a full-blown pop-cultural fixation. Websites and apps promising to match users with their celebrity lookalikes have infiltrated the market. At the same time, TikTok’s filters instantly transform users into their favorite stars with the tap of a screen. One viral filter allows you to upload any photo which includes multiple people, and it’ll morph your face into whichever person it thinks you look most like.

These filters use AI facial recognition technology to analyze a user’s features and match them with those of celebrities, often providing instantaneous results that users can share with their followers. Avid TikTok user and Tufts freshman, Tara Patnaik, said it feels “like a slot machine.” She noted that it initially seemed that the product was “randomly connecting two unconnected faces,” but after trying the filter multiple times, she found that she was obtaining the same precise outcomes no matter how many times she tried. When asked why she used these filters to find her doppelgängers, she said, “I think it’s human nature to find fun in unexpected familiarity.”

This technological facilitation of the doppelgänger search has transformed what was once a rare, one-chance occurrence into an everyday thing for many TikTok users. The accessibility of these filters has democratized the concept of celebrity resemblance, allowing anyone with a search engine or social media to participate in this digital manhunt for their celebrity doppelgänger.

This obsession with finding a doppelgänger has also catapulted a few individuals to stardom, as they monetize the fame of their celebrity lookalike. Paige Niemann has over ten million followers on all her social media accounts because of her uncanny likeness to Ariana Grande. Niemann’s

content, which often features her mimicking Grande’s mannerisms and style, has garnered billions of views. Ty Jones, an Ed Sheeran lookalike, is a professional doppelgänger who books impersonator roles in advertisements and events. Jones first gained fame on Facebook in 2011 and has since started the ‘Ed Experience’ featuring him playing gigs worldwide. These doppelgängers have effectively leveraged their celebrity likeness into social media stardom, further fueling the public’s obsession with finding their lookalikes in hopes of reaching the same level of fame.

While many try a filter, laugh at the results, and then move on with their lives, the persistent desire to resemble celebrities often stems from complex psychological and social factors. One such factor is Celebrity Worship Syndrome (CWS), a term coined by psychologists Lynn E. McCutcheon and John Maltby in 2003 to describe an obsessive interest in famous personalities. The ‘Celebrity Attitudes Scale’ (CAS) is most often used, and results show that those who score highly on the CAS (those who suffer from CWS) are more likely to get cosmetic surgery to emulate every aspect of a star’s life—especially their appearance. They also have poor interpersonal boundaries, identity dispersion, as well as anxieties about their bodies, and foster parasocial relationships with celebrities. CWS is often correlated to mental health disorders and maladaptive behaviors. However, there is still debate about whether mental health issues precede celebrity worship or whether celebrity worship somehow causes mental health issues.

In this way, hidden behind the fun of the filters are issues of self-esteem and personal insecurities. Magazine covers, movies, TV shows, and social media feeds are saturated with images of conventionally beautiful people that are curated and often heavily edited. This constant exposure shapes our collective understanding of what is considered attractive or desirable, creating a positive feedback loop where people strive to emulate these ideals, further reinforcing their dominance in popular culture. A 2023 study published in Frontiers in Psychology found that individuals who frequently used filters that changed their physical features reported

lower self-esteem and higher rates of body dissatisfaction compared to those who did not use such filters.

Furthermore, looking like a celebrity can be seen as a shortcut to validation and acceptance, as these figures are often beheld as the pinnacle of beauty and success in our society. ‘Pretty Privilege,’, or the social advantages offered to conventionally attractive individuals, comes into play here; studies show that we constantly perceive and respond to people based on their facial appearances. Facial features and expressions convey impressions about a person, and people who are perceived to be more physically attractive are often believed to be “more sociable, dominant, sexually warm, mentally healthy, [and] intelligent.” Then, these impressions are accompanied by preferential treatment for more conventionally attractive people in occupational, social, and even judicial settings. Hence, physical appearance matters not only when our reactions to a face are arguably relevant to our choices, but even when those choices should be driven by more objective information. So, by attempting to emulate the appearance of socially accepted celebrities with a widely beloved face and persona, people hope to tap into these privileges and gain the associated benefits in their personal and professional lives.

In extreme cases, the desire to look like a celebrity can move from temporary filters to permanent plastic surgery. One plastic surgeon from Montreal with over twenty thousand followers on Instagram, Dr. Moubayed (@montrealfacedoc), advertised his signature ‘Cindy’ nose, which became a widely accepted rhinoplasty style after many patients requested a small, upturned nose like the one of the Instagram model Cindy Kimberly (@wolfiecindy). The ‘Cindy’ nose job has become a running joke among plastic surgeons on TikTok. For example, Dr. Charles S. Lee (@ drlee90210 on TikTok), a plastic surgeon in Beverly Hills with over one point two million followers, made a TikTok of himself sighing after “the 178th patient that asked, ‘Can you make my nose look like Cindy Kimberly?’” This demonstrates how quickly a specific feature can become a trend, leading to the homogenization of beauty standards.

The case of Oli London, who underwent multiple surgeries in an attempt to resemble BTS band member Jimin, is another stark example of this trend. Oli London (@londonoli on Instagram) is a thirty-four-year-old internet personality who became infamous after he underwent thirty-two plastic surgeries—including six nose jobs, an eye surgery, a facelift, a brow lift, a temple lift, and skin whitening injections—in his journey to look like Jimin, or his quest to achieve “perfection” as he puts it. Oli London, a white man, identifies as Korean and believes he is “transracial” after his surgeries, which were based on racist stereotypes about Koreans. These surgeries transformed him into a caricature of what he believes a Korean man was supposed to be like, furthering harmful notions about the singularity of Asian people.

Such drastic transformations carry significant physical risks, including complications from surgery, long-term health issues, and permanent results that fall short of expectations. The problem is the loss of human values and replacing them with the false values of glorifying an attractive person of higher social status and the fact that these surgeons profit from the ideology of a society that serves vanity.

Ultimately, the doppelgänger phenomenon serves as a mirror to our society, reflecting our collective obsessions, insecurities, and the power of celebrity influence. We all feel the pressure to place on ourselves and others the concept of “looking like someone,” unconsciously attempting to align ourselves with the aesthetics we value, but would it be so bad if we just looked like ourselves? If you could stand face to face with the idealized version of yourself, would the person staring back at you even be you?

In the last weeks leading up to the 2024 Presidential Election, America has watched as both presidential candidates make their final attempts to secure votes from the ever-ideologically-shifting electorate. While this is becoming increasingly common each election year, this cycle has witnessed many crucial demographic groups shift away from the parties with which they have historically aligned. As this battle for key votes takes place, two demographic groups stand out as particularly important: Latinos and white women. These two groups reflect how voting habits have transformed over the last few election cycles, but their shifts are happening in opposite directions—Latinos toward the right and white women toward the left. Whether it is social media presence, ideological adaptation, or rallies across the US, both the Kamala Harris and Donald Trump campaigns have made enormous strides in attempting to reach these pivotal demographic groups.

Though Kamala Harris currently has a 14-point advantage against Trump amongst registered Latino voters, this advantage is the lowest Democrats have held in the last four presidential election cycles. In contrast, the support for the Republican Party by one of the largest demographic voting blocs, white women, has eroded by six points since the 2020 election. In a time where many voters are loyal to their views and undecided voters are few and far between, both the Democratic and Republican parties have been swarming these demographic subgroups with a plethora of strategies in order to secure any votes still up for grabs.

The recent rise in Trump-aligned Latino voters coincides with an increase in the number of second- and third-

By Sofia Valdebenito

generation Latino American voters, who make up ⅔ of eligible Latino voters. In an interview with NBC News, Trump pollster Tony Fabrizio pointed out that Latino voting habits are now beginning to resemble those of white voters more than other minority voters. Tufts Political Science Professor Deborah Schildkraut explained that as these second- and thirdgeneration Latinos become removed from their first-generation Latino American relatives, the Latino population in the US retains “varying degrees of connection to the immigrant experience.”

As a result, their policy priorities have shifted from seemingly more relevant issues like immigration to the issues that Americans tend to care most about nationwide. In a written statement to the Tufts Observer, junior political science major Rolando Ortega drew from his personal background as he explained, “Latinos aren’t single-issue voters… Yes, immigration is very important, but I feel like it becomes less prevalent the longer someone has been here and for younger generations.” He emphasized that “Latinos are part of unions, want to open small businesses, rely on public housing and schools, and worry about their kids’ safety too and want to hear how the candidates are going to address these issues on top of immigration.”

Generally, these shifting priorities are pushing them in a more conservative direction. Schildkraut agreed, saying, “If you look at the attitudes and candidate preferences of Latino registered voters, the ones who were born in

the US tend to give higher ratings to the Republican candidates.”

These preferences are revealing themselves in the 2024 election—70 percent of Latino voters for Trump expressed that they intended to vote for Trump because of what he stands for, rather than as a means to avoid Harris as president. Ortega cited “the fact that Trump has tried to embrace a “macho” persona” as one factor in this trend. “Feelings of strength/competency and machismo is something I feel is very important to Latinos, especially among men who traditionally have assumed the role of providers for their families and communities. They want to see leaders who reflect that strength and effectiveness in the context of politics.”

In comparison, Latino voters for Harris are almost split evenly (46 percent to 54 percent) in their choice to vote for Harris because of what she stands for, including her stances on the economy, health care, and gun policy, as opposed to voting for her in order to avoid Trump. More broadly, many Americans of the electorate aren’t fond of either of the two major-party candidates for president. Recent polls display that 47.3 percent of Americans had an unfavorable opinion of Kamala Harris, while 52.2 percent had similar feelings toward Donald Trump.

On the other hand, white women have been drifting in the opposite direction from that of Latino voters—shifting away from the Republican party, to whom they usually give an advantage. As a significant portion of the national electorate, they have given the majority of their vote to Republicans in most elections since 2000. In 2016, Trump won the white women vote by 47 percent, followed by an increase to 53 percent in 2020. However, Democrats may be on the verge of finally obtaining that advantage, thanks to what Schildkraut explained “has been building over the past couple years, in particular with respect to abortion, [which] has the po-

tential to make things different.” Since the overturning of Roe v. Wade in 2022, younger white women have shifted away from the Republican party, in particular those ages 18 to 34.

As a critical demographic group, many white women are torn between their dislike for Trump and their discontent with the results of Joe Biden’s presidency, specifically with how he handled the economy. These women are especially prominent in Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, and Michigan, the three former “blue wall” states (Democrat-voting states) that have the greatest chance of uplifting Harris to an Electoral College victory. Women in these key states have been targeted by a voter contact program run by the American Bridge 21st Century, a party super Political Action Committee that has spent around $140 million in their efforts to reach them.

Recently, Harris attempted to influence this demographic by appearing on Call Her Daddy, the advice and comedy podcast known as the “most-listened-to podcast by women” on Spotify, whose audience includes women from a variety of political backgrounds. In the same vein of looking to reach these crucial subgroups socially and culturally, Trump and his platform have received endorsements from well-known figures among Latinos to influence voters. In August, during his rally in the battleground state of Pennsylvania, Trump brought out Puerto Rican reggaeton artist Anuel AA, who noted the need for Puerto Rican unity to support Trump. Nicky Jam, another Latino reggaeton artist, also joined Trump at a Las Vegas rally in September to preach his support.

The candidates themselves are not working alone to mobilize the vote among these key demographics. Organizations across the nation are working to get out the vote and motivate historically low-turnout groups, particularly Latino voters. At Tufts, JumboVote is one such organization that works to connect college students with voting resources. Junior and

Co-Director of Resources Seona Maskara explained, “For underrepresented voters at the polls, at JumboVote, we’ve seen it’s really an access issue. A lot of times at Tufts, we see that our underrepresented voters are our Black population or Hispanic population.” She emphasized the effort the organization dedicates to these communities in particular, saying, “What we’ve been really trying to do is increase access by working with the Latinx Center and the Africana Center to host events where we can bring information to people.”

Whether through cultural connections or community appearances, both candidates and organizations are working to adopt this practice of meeting these significant voter subgroups where they are at. This is significant for Latino voters, many of whom access their media solely through American Spanishlanguage sources. Ortega considers this when talking about his own family. “I immediately think about my grandparents who speak very limited English, so they almost exclusively get their news from Spanish-language media (everything from Univision/Telemundo to their Facebook networks) and basically only listen to Spanish artists,” he wrote. With each new election cycle comes a unique set of voters, as the individuals that compose each demographic group naturally continue to shift. However, ultimately, these voters’ decisions are informed by much more than the actions each candidate takes within the final stretch of their campaign. As Schildkraut put it, “People are not voting in a vacuum—they are voting in a context.”

By Emma Selesnick

e sun beat down on the tall grasses of Hearsthall—a place so lush and untenanted in this heat, one could never imagine the bustling metropole only a mile down the road. e shadow of a young girl stretched peculiarly over the ground before her as she traveled her usual path. She cut west across the grass, but moved only at a trudge against the day’s humid mid-summer air. e path was rocky as usual. She headed to the main house of Hearsthall, where the families picnic when the weather is nice; on a day like today, though, she gured she would have it all to herself.

Hearsthall was a vast property, navigable only by three paths: West, East, and North. e main house laid at their convergence, with wild elds extending out on all sides. It was made of crumbling stone and, in the youthful eyes of the girl, stretched miles above her head. Abandoned for decades, the interior had been cleared out for the public, used as storage by farmers in the winter and as fairgrounds in early summer.

e girl’s family lived on the outskirts of the estate in an old cottage originally reserved for its serfs. Her parents were bakers and had been scrambling about the house since dawn, preparing for their upcoming market. e day’s chaos allowed her to slip past the white outer gate without notice and into the woods behind.

As she walked, she slipped her sandals o and icked them up, barely catching them with her ngertips. She relished the feeling of the tilled dirt between her toes. Coming around the bend, she could hear the rumbling of the sheep brushing their thick coats against one another in the far knoll. It was her custom to take the northern path, through the knoll, upon return to visit them. She liked to savor the last days of wooly coats before their summer shearing, watching knots entangle and bunch into distinguishing clots.

A cloud passed overhead.

She saw the worn pine gates in the distance and started to smell the house’s freshly manured lawn. Running to meet the splintered wood—an old friend—she tossed a leg over. And then the other. Balancing on the top rung of the gate, she looked back towards the trees and threw her arms back contentedly. She hopped down and walked to the backside of the house. As suspected, there was not a soul. Her body hit the ground. She writhed and rolled and curled her feet under herself. e dew-lit grass le a cold residue on her bare back. She rolled down the shallow slope and reached her arms out wide, forming a grass angel. Running her ngers against the damp earth, she closed her eyes and let the sun’s warmth atten the wrinkles in her blouse and between her brows.

With her eyelids steeped in golden rays, the girl began to remember. She thought back to the visit before last. In this eld. In this spot. Except then, she wasn’t alone. She recalled the visage of an old woman with silver curls resting just above her eyes. She had come from the other side of the house, had traveled the eastmost path. She told her the story of Hearsthall, the same one her mother had always told—the property had once belonged to the county but was opened to the public as a gi , a symbol of cooperation. Except, the old woman’s story ran deeper than her mother’s. She told a tale of unrest and cruelty. Of ghts over animals and earth. She told the girl of the contract made between the people and the nation. A settlement for peace upon one condition: the sacri ce of their sheep.

“Prophet,” the old woman called him. at was her favorite sheep. He would stand amidst the herd, acute and compelling. His wool shone twice as bright as the rest. It was double in length, too. As the girl’s mother had always told her, a sheep’s wool holds the memory of its people. Prophet was their keeper. No matter what challenges the nation posed, the sheep would uphold the culture of the land by means of oral tradition.

at day, however, the old woman warned the girl of a greater change coming—one not even Prophet e Sheepdog. “ e nation needs an agent,” she said. Someone to sew up the peace. While she had always imagined the dogs as docile creatures, the old woman explained that his shaggy frame and deep-set eyes, parading as one of the herd, would be of a much more baleful nature. His arrival would warrant an absorbing portent; perhaps a deep soreness in the bottom of her belly or a spacey dissociation in her head.

could withstand. the of and the ing and

Her eyes opened to the fading of the sun behind the trees. Still, the sky stayed bright chirring of the sparrows grew louder. She held the grass between her ngers—open-

28, 2024

closing around the dull blades. Her toes followed suit, muddying in the patch of earth at her feet. As she rolled up o the ground, she watched her blurred sight come slowly into focus. e familiar sound of e Shepherd’s boots traveling the house’s path became clear. A signal of her decided ight. She leapt and headed to the far side of the house, towards the east path—the old woman’s path—uncharted territory for the girl. She listened for the rumbling but heard only the wind’s rustling of Hearsthall’s rumpty bones. As she climbed the knoll towards the herd’s pen, more clouds crept in around the clearing.

On all other days, Prophet stood close to the gate to greet travelers and protect his sheep, but today, the girl could not nd the blur of his unkempt wool up ahead. e darkening sky cast long, spindly shadows on the grassy hill. She heard the booted feet again, realizing now they were not the footsteps of e Shepherd himself, but those of his young son. Beating against the dirt path, the boy was still obscured by darkness. A chilling breeze shot up the path and through the small of her back. e Sheepdog.

e comforting rumble of the sheep had been replaced by a pulsating growl. e path laid before her had turned to mud. e booted feet cried.

She skipped over the path’s last stretch to reach the pen. Prophet’s shadow was cast over the gate, pouring through its cracks. e sun’s rays crept through the overcast sky and illuminated the rich pool of sheep coats, revealing rough stripes of blood, red upon Prophet’s pure white wool. e two black boots had fallen over the pen and into the herd. e Shepherd’s son lay sprawled at the feet of e Sheepdog.

Like the girl, e Shepherd’s son had slipped away from his father. He had cut through the high grass and climbed the knoll. But he had heeded no warn- ing about the coming of this new dog. e lost boy, with one bloodied hand outstretched, laid still in the humid grease of the herd. Prophet nudged him with his nose, a prayer. e Sheepdog li ed a black boot between his teeth, a triumph. e young girl threw her legs over the gate once more, stood atop the rung, and screamed.

Joe Dante’s 1993 film Matinee is an affectionate, comedic homage to the horror B-movies of the 1950s. The film takes place in a small Floridian town during the height of the Cuban Missile Crisis. It centers around Gene, a boy who is taken under the wing of a con artist director preparing for the premiere of his new monster movie, Mant! featuring the iconic tagline “half man, half ant, all terror!” During the climax of the movie-within-themovie, the audience is sent screaming out of the theater in terror, genuinely believing that nuclear fallout had begun, only to find that the sun is still shining, at which point they breathe sighs of relief and demand to see the movie again.

Horror is a safe space for people to confront their anxieties. A truly effective horror film brings an audience as close to their deepest fears as possible while still keeping them behind the screen. These fears range from the lasting phobias humanity has felt throughout history, such as death, failure, or change, to contemporary cultural, political, and technological tensions. It is impossible to trace an exact parallel between American history in the 20th and 21st centuries and what horror films were made at the time. However, certain eras, especially ones of heightened social and political tensions, stand out as being particularly fertile ground for horror cinema.

Matinee is a campy and nostalgic movie, but it also illustrates why movies like Mant! appealed to audiences in the 1950s. A reptilian metaphor for nuclear fallout stomping through Tokyo hit much closer to home than the Transylvanian vampire that had frightened audiences two decades prior. Most of the horror films of the 1930s and ‘40s were influenced by gothic novels

and other classic literature. The monsters attacked and terrorized the individual, but they were not world-ending threats. In the book Terror and Everyday Life, a retrospective on the cultural significance of some of the shifts between eras in horror, author Jonothan Lake Crane describes this transformation.

Crane states in his book, “Where previous horror films had relied almost exclusively on the husks of earlier dramatic forms and inherited folktales for scenarios to enact, the 1950s horror film repudiated those conventions and began to work on

By Amon Gray

American soil with contemporary dilemmas.” In the 1950s the monster became the bomb, the promise of a devastating nuclear war, and the collapse of society. Movies like Them! (1954) and Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956) used a combination of horror and science fiction unseen in decades prior to tell stories influenced by Cold War paranoia.

Dr. Malcolm Turvey, an art history professor at Tufts who teaches a course on horror films, describes a major shift that occurred in horror in the late ‘60s. This was due to the Hays Code, or the

Motion Picture Production Code, being lifted, which gave studios strict guidelines around violence, profanity, and suggestive material. Because of this, horror movies after the ‘60s contained more graphic violence, which became a staple of many subgenres of horror to come.

Turvey also noted a more subtle shift in the subject matter of horror films. Psychoanalysis began to infiltrate American culture in the 1940s, which can be seen in movies like Cat People (1942), the story of a woman who believes she is descended from ancient shape-shifters and a psychoanalyst who attempts to “cure” her. However, the rise of the psychotic killer and the public notion of the serial killer did not enter the public sphere until the late ‘50s and early ‘60s. This introduced characters like Norman Bates from Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960), one of the first, and still culturally iconic, serial killers in film.

“I think that when new concepts and nw paradigms are introduced into the culture, that gives rise to new conceptions of the monstrous,” Turvey said.

tween these characters and the ones shown in films from that decade is apparent. As Crane explains, “By starting in the late 1950s with this trite picture of teenage relics at the end of the Atomic Age, Friday the 13th is ridiculing scenarios created following the leveling of Hiroshima. The characters are thin, even by the standards of the postwar era, and the events that ensue would never have appeared in an atomic horror film.”

In 1978, John Carpenter’s Halloween splattered onto the big screen to incredible financial and critical success. The story follows a teenage girl, Laurie Strode, and her friends, who become the target of the iconic escaped mental institution patient, Michael Myers. The film’s success led to an explosion in the slasher genre with subsequent titles including Friday the 13th (1980), Nightmare on Elm Street (1984), and Scream (1996). While John Carpenter’s directing, use of suspense, and iconic piano melody heralding Michael Myers all worked to terrify the audience, one of the biggest reasons for Halloween’s unlikely success might have been its setting. Placing the killer in middle-class suburbia, a comforting representation of American post-war values, threatens the audience in a way that no other setting could.

Another setting situated in a quintessential part of the American experience is summer camp. In the horror film canon, summer camp is the stomping grounds of Jason Voorhees, the masked killer of Camp Crystal Lake in the Friday the 13th franchise. The opening of the film shows two counselors being murdered by an unseen figure in the late 1950s. The contrast be-

While slashers lurking in quiet, middle-class America exhibits clear cultural anxieties, some films are more subtle in their parallels—or don’t exhibit them at all. Turvey observed that movies like Alien (1979) more subtly incorporate the fear of corporations sacrificing human life for profit while other films like Christine (1983), featuring an evil killer car, are more divorced from the current culture. We’ve seen how the subconscious fears of American society have a tendency to find their way into horror films, but that’s not always the case.

“As Freud said, a cigar is just a cigar. I think the way people make horror films is that they try to think about things that are going to scare people, and those things aren’t always going to be representations or expressions of things that really do scare people,” Turvey said.

The parallels between American history and horror movies seem to appear most often when there is something real to be afraid of. In the wake of the September 11 attacks on the World Trade Center, the imagery of rubble, smoke, and falling buildings became taboo for movies, with popular disaster films like Independence Day (1996) and Armageddon (1998) becoming far less prevalent than they were in the late ‘90s. While not a horror movie in the traditional sense, War of the Worlds (2005) was one of the first films to invoke imagery paralleling 9/11 to terrify its audience by portraying the vulnerability of urban life. Urban destruction was a subject of spectacle for disaster movies of the ‘90s. However, War of the Worlds stylistically portrayed the ground-level chaos with ash, dust, and fleeing crowds.

In the modern era, art horror films have grown in popularity. Directors like Jordan Peele, Ari Aster, and Robert Eg-

gers have satisfied audiences’ needs for a more sophisticated approach to horror. These films explore relevant themes of isolation, cultural identity, and technological dependence.

“There has been a rise of what some people refer to as complex storytelling, where, instead of the more easy to understand, linear narratives of many mainstream movies, you have more challenging narratives that have more parts to them, characters are more ambiguous, messages are more ambiguous, and so forth,” Turvey said.

Halloween ends with Dr. Loomis, Michael Myers’ psychiatrist, shooting Michael and sending him out of an upstairs window, but when Laurie looks out the window Michael has vanished. The movie closes with shots of the empty house, reminding the audience of the place they will return to once the credits roll, and leaving them with the lingering feeling that the killer is still out there. A staple of horror is that the monster never really dies. They live on in sequels and remakes only because the audience can’t walk through the screen and poke them with a stick just to make sure they are really dead.

To some, movie monsters such as Michael Myers are characters made frightening by a suspenseful narrative and clever filmmaking tricks. To others, they are representations of universal fears. To everyone, whether they know it or not, they are a chilling reminder of the current fears of the American public. From the atomic monsters of the ‘50s to the slashers of the ‘80s to the crumbling cities of the ‘00s, horror has realized some of American society’s deepest anxieties. Just like the images at the end of Halloween, our fears linger within us even as the lights go up and the credits roll.

By Jason Lee

They are SO fake online!—an accusation that many of us have heard when someone’s online presence does not match their “real” self. Whether we are scrutinizing a botched Facetune attempt or questioning a post that is just asking for attention, many of us have either made or witnessed this type of judgment. In an age when flters, photoshop, and AI-generated images dominate our feeds, conversations about online authenticity are growing louder, with Merriam-Webster naming “authentic” as 2023’s Word of the Year. Social media tasks users with building content through a series of creative decisions that ofen involve crafing a convincing portrayal of the truth—fnding the perfect angle, writing a witty caption, and editing photos subtly to enhance them without making it obvious. Social media is driven by users’ curation, and producing content for others’ consumption is inherently a performance. Authenticity, or the ability to present ourselves truthfully, becomes clouded by this curation, making it impossible to achieve. If we consider social media as a realm in which “reality” does not and cannot exist, why do we hold ourselves to such high standards of “truth” online? Why do we ultimately condemn inauthenticity on platforms designed to promote it?

Te internet, no longer a place where users simply log on and of, now exists as a distorted extension of our reality. Social media pushes us to manufacture a lasting portfolio of our lives through photos, videos, and text, causing a disconnect between our online social rituals and our lives. Given this departure from reality,

online authenticity is not only impossible to measure objectively but unattainable and not something to strive for.

Always one search away from any digital portfolio, humans have never before had such easy access to others’ lives. Social media grants us this ability but implicates us in a system of constant surveillance. Tis system mirrors the panopticon, a theoretical prison design introduced by 18th-century English philosopher Jeremy Bentham. Its design consists of a central watchtower that allows a guard to observe each prison cell. Te inmates cannot tell if a guard is in the tower, much less who the guard is. Consequently, they internalize this surveillance and regulate their own behavior as the watchtower’s authority transforms from a “limited physical entity” to an “internalized omniscience.”

By merely existing on social media, we assume both the role of the voyeur—one who gains satisfaction from secretly observing others—and the performer, the watcher and the watched, the guard and the inmate. Whether consciously or not, we as performers internalize the surveillance by considering the responses and critiques of the voyeurs. We post knowing that our lives will be observed, yet we remain unaware of when, how, or by whom we are being observed. Given these parameters, one cannot post authentically. We cannot “dance like nobody is watching,” because it is so deeply instilled in us that everybody is watching.

Given our awareness of this constant surveillance, our social rituals become calculated and fake. Likes, comments, and other interactions operate as social cur-

rency, representing the value one gains through one’s presence in a social network. As an avid commenter, I ofen refect on why I do so. Yes, I comment to show support and afection, but the implications run deeper. Public social media interactions serve to legitimize friendships, both in the eyes of the friends and in the eyes of the voyeurs. In addition, the reciprocity of these interactions carries an unspoken social weight. We inevitably feel curious when our online interactions go unreturned. If I always comment on a friend’s posts, I might be peeved if that friend does not interact with mine. I wonder: was their silence innocuous, or is there something under the surface? Were they in the panopticon’s watchtower, or did they just not see my post?

Despite the anonymity of many online actions like unfollowing and stalking, this information can be revealed for a price. Several sketchy third-party apps claim to reveal hidden analytics, like which accounts view your profle the most. Tese apps are ofen free but sometimes generate revenue by stealing your information or hacking your account. In 2017, I used an app called Sherlock to see who had stalked my account and it automatically and nonconsensually posted a screenshot of this information to my Instagram profle— ironically, this may have been the closest thing to authenticity on my feed. While this is pretty harmless, I have also witnessed

my friends’ accounts being hacked to promote online pornography or shady cryptocurrency sites. More recently, a scammer produced a deepfake video of my friend, using her digital dopplegänger to lure her followers into clicking a virus-ridden link. Getting hacked is an inherent risk of social media use, but we amplify this risk by acting upon our desire to know how others interact with our content. Is this beneft of stalking our stalkers worth the cost of losing access to our digital portfolio?

As voyeurs, we are constantly drawing conclusions about others’ lives and relationships based on their online performances. I am guilty of exclaiming, “ Tey took down their photos together—did they break up?!” to my friends about a couple I hardly know. Tese digital gestures of unfollowing and archived photos may be small, but someone could always be watching. Perhaps our assumptions refect our own anxieties or the social pressure to remain “in-the-know.” When we cannot perceive aspects of someone’s life online, we become critical and skeptical. I especially remember moving to college and trying to gauge how my high school peers were doing: She hasn’t posted all se-

mester; I wonder if she’s not having a good time. When people’s lives are inaccessible, we almost feel excluded and make assumptions as a result. Te ambiguity of these online interactions causes us to overanalyze their real-world impact. Te fault lies not with the individual voyeur for making assumptions, but with social media’s structure, which encourages us to interpret others’ lives based on small, performative snippets.

However, some contend that authenticity is an attainable ambition. One might approach authenticity by adhering to a casual posting style, which is becoming increasingly common. Te movement to make Instagram casual again aims to revert Instagram’s posting culture to a spontaneous and laid-back vibe. It was facilitated by the introduction of the carousel feature, which allowed users to share up to fve photos (now expanded to 20 photos or videos) in one post, giving birth to the “photo dump,” which began as a collection of photos with little cohesion but now dominates feeds. Despite the photo dump’s notion of whimsically cleaning out one’s camera roll, it is no less a performance of curation. Te performer may

be “dumping” out their photo album, but they do so within a system that fundamentally distorts reality. Sharing anything on social media requires decisions regarding how to present oneself. Tese choices create an inevitable rif between the “real” self and the constructed online persona.

If this game of surveillance and inauthenticity stresses you out, why don’t you just forfeit? It is an option, but I am afraid that we are far too entangled in this system for a smooth departure. If you end the performance and delete your online portfolio, you are the only one taking a bow whilst the show continues in your absence. To repeat, the internet no longer feels like a separate dimension as was perhaps once the intention, but rather a distorted extension of our lived reality. Disappearing from the internet will bring freedom from the panopticon, but also entangles one in a new trap of exclusion. Instead, you become invisible to the audience of voyeurs, eliminating your perceived existence. By stepping away from the social networks in which the average American spends over two hours a day “socializing,” you risk social disconnection. You will be living of-the-grid, which is a veritable path, but not an easy one. Ultimately, the desire for online authenticity is paradoxical. Te virtual world is a virtual display of reality, meaning that it is nearly as described, but not completely. Given the intrinsic role of performance in posting, striving for authenticity becomes a fruitless goal. Perhaps, we are better of shifing the focus from authenticity to social media’s impact on ourselves and our relationships. Rather than chasing an elusive ideal, we can aim to engage more consciously with social media and our online interactions. We must challenge our assumptions and remind ourselves that social media is a mirage. Please continue to post however you like, but do not chase authenticity—it is just not worth it.

Maybe you’re scared of change. Maybe you’re scared of isolation. Like most people, maybe you’re scared of death. Those things are frightening, I agree. However, they’re completely out of our control. They happen no matter how you feel about them. The unknown, heartbreak, and death are inevitable in human existence; it’s futile to stress over these when there’s much more that is actually in our control.

For me, that lack of control is comforting. Like many other college students, I try hard (naively) not to experience failure or rejection. I avoid public speaking in class, but I am definitely not scared of it. I am an avid roller coaster rider and I love heights; I loved flying so much as a kid that I would tell people my favorite place in the world was the airport. I’m also not scared of small spaces, needles, blood, confrontation, being judged, intimacy, or any of the other heavy hitters. What keeps me awake at night, what makes me nervously zone out in class, what sends utter chills down my spine, is my fear of forgetting.

For me, time is nightmarish. It marches on at an unchanging pace, yet seems to slip out of my fingers no matter how hard I try to come to terms with its persistence. Time doesn’t wait for you to be ready to keep going. You might realize five years went by, but where were you?

By Kate Weyant

After the pandemic, I don’t remember things as clearly as I used to. I think most people would agree that there’s been a clear schism in our timelines: Before COVID (B.C.) and After Disease (A.D.). Since the pandemic, time has felt like a flip book, each fleeting moment and image blurring together, with fragments of images just slightly out of my reach. Life has felt like a train I’m passively trailing behind, whereas before 2020, I was firmly in the driver's seat. Chalk it up to long-term COVID brain fog, but I think the sudden jump from being a high school freshman to a graduating senior pushed me out of control, out of the driver's seat. It feels like I’ve been playing catch-up ever since, like the train of life left without me and I’m struggling to keep pace behind. And with it, took my once sharp and vivid memory. When I was younger, everyone told me I had the best memory. I remembered names (Chloe’s, a soft serve place my family visited in 2017, not to be confused with Zoe’s, a breakfast diner we hit one time in 2015), random facts (my kindergarten teacher’s grandchildren decorate heavily for Halloween), and miscellaneous trivia (ask me anything about the PBS Kids show Arthur.)

My mom, also known for her incredible recall, leaned on my 8-year-old self to

remember even the most minor specifics. In my small town, with my teeny tiny grade, it was something I was actually known for. And with it, I experienced life with profound intensity. For better and for worse, every memory was colored by fervent sensation. My emotions were potent, tangible. They formed my memories, made them crisp. My brain was filled with a light show of every emotion, vibrant, powerful, and always on.

Entering my senior year of high school, I realized my brain no longer functioned as it once did. That somewhere around 17, all my moments blended together at half the intensity they used to hold, and my greatest fear came into the light: forgetting. Or rather, not being able to keep sticky memories—to only have memories that come and go as they please, slipping out of my mind like they never really cared to be there. It’s weird, I think. In terms of day-to-day actions and decisions, I’m in charge, calling the shots, and soaking up every bit of college possible. Making sure every single penny I am paying to this school is worth it. But that’s what’s so scary; despite all the ways I do so much, live so fully, I can’t remember it with the color I feel that I should. I can’t remember how I felt in November of last year, nor the

nerves of being a freshman during Orientation Week.

That’s what’s so terrifying. It feels like the intensity of my brain, the millions of neurons firing all the time, are just shooting into the dark. They used to paint dynamic pictures, moving images in striking brilliance. No fog, no haze. Now, it feels like my brain runs at thirty miles a minute, a tornado of thoughts and songs and worries and reminders and fears and plans and conversations. My perpetually active mind helps me in many ways: it keeps me rigidly organized, observant, and perceptive. But this whirlwind of noise is the gatekeeper to my hippocampus. It’s the beast that stops me from living in the moment, from remembering. All the thinking prevents me from actually feeling.

I now recognize this fear in two distinct points of my life. First, in June of my senior year of high school. The supposed biggest year of my life at that point—the most emotional, the most fun—had gone by, and I couldn’t remember most of it. A chapter was coming to a close, yet I couldn’t think of the words that were in it. I remembered crying over supplemental essays, driving to school, and complaining about rehearsal, but not much else.

Then, there was winter break of my freshman year of college. My parents asked me to reflect on my first semester as a college student, to give them the rundown of how I felt, what I did, and I barely knew what to say. I felt like a middle schooler, basically giving them the classic: “I don’t know… it was good.” Typically a chronically verbose oversharer, I knew something was wrong.

Temporary solutions quickly arose, but they were just that: stand-ins. I became ever more glued to my phone, diverting the burden of memory onto it. My notes app is filled with memories I thought I’d be upset to forget, hastily typed in the moment. For many months, I had a reminder fixed on my lock screen: “take more videos!” because I felt like I wasn’t documenting enough real footage and I didn’t have enough supplementary memories. I’ve tried to journal (which I don’t

love), tried to meditate (hated that), and even tried going to bed earlier (which just gave me more time for extremely vivid dreams).

Giving in to my mom’s nagging, I finally got a therapist. This led to my process of researching ADHD in women, my diagnosis of generalized anxiety disorder, and getting on Lexapro. It decreased the noise, cleared the fog, and slowed the train down long enough for me to finally hop back on. It changed my life. It made me feel like myself again.

Anti-anxiety medication can be seen as a long-term solution, but for me, I think it’s still temporary. Quieting the noise allowed me to reflect on my life since 2020 and on my inability to store memories the way I want to, but it wasn’t a cure.