Words and photos by Zoe Ho

Words and photos by Zoe Ho

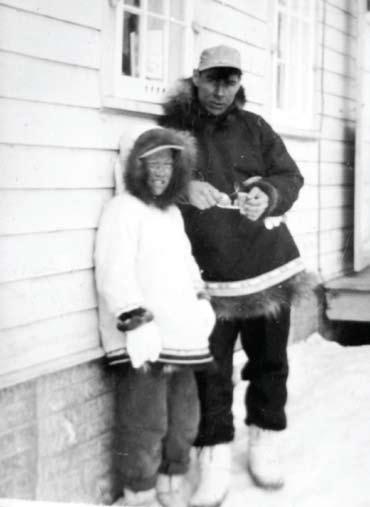

Sachs Harbour residents Lawrence and Beverly Amos pose with a plaque commemorating their community's participation in the survey.

Sachs Harbour residents Lawrence and Beverly Amos pose with a plaque commemorating their community's participation in the survey.

for residents living in s achs h arbour, a full health check-up is rare. There is only one nursing station, and no full time doctors in this community of about a hundred people. kevin Gully, an eighteen year old youth, is wearing a holster monitor for the first time. Having his health assessed on an icebreaker, the a mundsen, parked in the ocean several miles from the shores of his home makes this situation even more unique.

“Oral health is minimum to none in our fly-in communities,” said Crystal Lennie, health policy coordinator for the Inuvialuit Regional Corporation (IRC). “They get a dentist maybe twice a year. If you lived in southern Canada, you could just pull over to the side of the street and walk into a dentist’s clinic.”

“I’ve heart problems, abnormal beating,” he said. “My mum told me to go for this to see if I am ok.”

When medical emergencies happen that the nurse in his community cannot handle, medevacs – emergency flights -- are employed to fly patients to Inuvik, or Edmonton. “I don’t understand it really,” he said, “It costs a lot more to fly people down south, than just to have a doctor on site?”

Those who live there, or who work in the area know about the lack of proper health services in the n orth, especially in the remote communities.

Dr. kue young, professor of p ublic health at the u niversity of Toronoto, and Dr. Grace Egeland from McGill u niversity in Montreal shared the desire to make a contribution towards improving the health of indigenous people.

“There have been many studies about the Inuit, major surveys in last 20 years in Greenland and n unavik, most are land based. It’s very expensive, and everybody was doing things slightly differently so it was difficult to combine data,” said Dr. Young. The doctors launched the Inuit h ealth s urvey, with funding from the International polar year and the Canadian Institute of h ealth research.

This survey would travel through the Canadian Inuit regions, to collect data on Inuit health with a standardized protocol. In 2004, n unavik (in n orthern Quebec) was surveyed. Eastern n unavut was surveyed last year. This year, the a mundsen icebreaker carried the survey to the Inuvialuit s ettlement region, n unavut, and n unatsiavut.

The Inuvialuit regional Corporation partnered with the survey, coordinating a steering committee, helping with planning and focusing the questionnaires to reflect the priorities of this region.

p articipants, with their ages ranging from young to elderly, were randomly picked to take part in the survey, to keep the data pure and usable. They have to fast before they get on board, as blood tests are required as part of the clinical testing. The survey takes about two hours, from the time participants are transported to the a mundsen either by helicopter or by barge.

o n arrival participants are welcomed and given a health chart. They then have blood samples taken by nurses. These samples will be tested for glucose and diabetes risk, environmental contaminants and fat levels. for participants who are over forty or who have heart problems, a holster monitor is attached to measure heart rhythm and rate. stations are set up for interviews and bone density testing (for women over fourty). p articipants over fourty will also be given an ultrasound to see if there are any blockages in a main artery, to see if they are likely to have a stroke. n urses will also measure your basic height and weight, weight circumference and body mass index.

a manda Lester, resident of p aulatuk, said, “I am glad I had the oppourtunity to do it. At first, I wasn’t interested, but now I am thinking, let’s do it again! It showed me more about my health, and for the others who participated too.”

a manda was excited to show s amantha kerr, p aulatuk nurse, the ‘passport’ she received after completing the survey. Together, they decipher the numbers for her hemoglobin (the amount of iron in her blood), her blood pressure, and other immediate measurements from the tests. The nurse will be able to follow up on some of these for a manda.

“They’ve got a lot going on here that we can’t offer at the clinic,” said s amantha. s he hopes that the study will be “ammunition” for the region to demand for better healthcare services.

s he also noted that the questions in the questionnaire, regarding mental health, physical health, food, country food, housing and expenses, were “things that we would really like to ask but don’t always get the chance to. It’s a way to get a whole group to learn what’s going on and what’s changing.” The questions were included at the request of Inuit organizations, who wanted to assess urgent priorities.

“W e are hoping that this study will impact policy, that we’ll be able to get funding for programs that are needed in the ISR, so we won’t just be saying [to funding resources such as government] ‘this community needs this’, we’ll have the numbers to back it up,” said Crystal.Shelly Illasiak, participant from Paulatuk, sharing a moment with interviewer Bernice Aggark of Chesterfield Inlet. Aaron Ruben cuts his toe nails for the selenium testing.

“She asked if I wanted to get a counselor. But I told her I was fine after I took a moment. a s long as I felt a connection, I felt I could open up.” a manda said she was ultimately happy to contribute to an initiative that could bring better healthcare to her community.

The words ‘I am proud of you’ and ‘ you’ve done our people proud’ were heard regularly during the days of the Inuit h ealth s urvey in the I sr a nita pokiak, interpreter and interviewer for the survey, thanked each participant she met this way.

ooleepika Ikkidluak, dispatcher and liason for the Inuit h ealth s urvey is from Iqaluit. She took a month of annual leave from her job to be part of the survey for the second time. s he said giving up her personal time to be part of the survey is “totally worth it.”

“It will help us to have real data to urge the government to wake up to the resources that are needed here,” ooleepika said. s he said she was always aware that Inuit have common challenges, but seeing through her travels for the survey, “first hand the lack of resources, social issues, language barriers and overcrowding really opened my eyes.”

The researchers are going to work hard to get the rest of the test results back to the communities as soon as possible. There will be a follow up study in seven years. researchers hope the communities will be eager to assist in the study again then.

“I am so proud of everybody, said Samantha. “At first I worried because we don’t have enough mental health resources and support already, and I knew that there was going to be a big mental health component in the questionnaire. a nd we’ve had a lot of triggers already, with the residential school experience and the I pa trials [the I pa provides compensation for sexual and physical abuse] that are coming up. But they had a mental health practitioner on board, and they’ve told people even if you’re right in the middle of something, you can stop.”

a manda said she was in the middle of her interview with interviewer a nita pokiak, who is also Inuit and living in the Inuvialuit region, when she felt triggered.

“It’s always good that the feedback is immediate, so the elders don’t feel, ok, we got studied again, now what?” said Edna Elias, an interviewer originally from kugluktuk. s he was also part of the land team that begins the initial contact with participants, informing them about the purpose of the survey and interviewing participants who are home-bound. “In u lukhaktok today, I interviewed elders and people who were home-bound,” she said. “I could use my dialect and they were happy to see someone they know. That makes it really comfortable from the get-go.”

Crystal Lennie, health policy coordinator for I rC, seems to be everywhere at once. from 6am onwards, she is on the a mundsen ice-breaker, or in communities, helping to mobilize, inform, and sanitize participants. s he travels back and forth by barge on choppy waters, all in the name of doing everything she can to help the Inuit h ealth s urvey run smoothly.

h er involvement with the h ealth s urvey began in n ovember 2007. Lucy kuptana, executive director of I rC’s Community Development Division had heard through Inuit Tapiriit k anatami that an Inuit h ealth s urvey, similar to the one carried out by Laval u niversity in n unavik in 2004, will be conducted in n unavut.

“We wanted in,” said Crystal. The Inuit h ealth s urvey is a polar year research program, and ITk informed the principal investigators that there were Inuit living in the rest of Canada that could not be left out. n unasivut also pulled together funding so they can become part of the survey.

Crystal brought the I sr Inuit h ealth s urvey steering committee together for an initial meeting, the first of many meetings to take place in Inuvik, a klavik, and Edmonton. The questionnaires that participants would have to answer were thoroughly considered, balancing the need to reflect the local culture of the ISR and yet kept similar enough to the questions in the 2004 survey so that data collected can be comparable.

a s the a mundsen was only available for a limited amount of time, the land teams had to work hard to make sure that the number of participants needed for the survey in each community can be met. u nexpected weather or community events are challenges when the icebreaker can only be in each community for a day or two. Tuktoyaktuk, which had two events that weekend, was the first community to participate in the survey.

“It was tough going in Tuk at first, but we had participants going on the ship,” said Crystal. “It was nice when people stepped off the helicopter and came back to hug me. Everybody was saying, ‘Thank you so much for picking me!’”

She remains uplifted despite the challenges she is facing. “I really enjoy visiting all the communities,” she said. “Because they enjoy seeing me, that’s what gives me the love of the job, it gives me the extra jump to work harder.”

She does not mind the hard work, and says it is an honour to be chosen for the job. “Sometimes I feel pressure, but you stay up till 1 o’ clock in the morning till it gets done,” she laughs. “I feel very blessed and honoured to work in healthcare. It is a field with such large impact, especially because it impacts lives.”

She smiled appreciatively. “It’s a what-you-make-of-it type of job and I really wanted to get the best that we can get for our people.” h er contributions will in part bring in services such as cancer screening and palliative care.

“When I first started I went to talk to the communities, the community corporations and the elders committees. I asked them: what are your priorities in healthcare, where do you want me to focus and how do you want me to go about doing my job -- they directed me and that’s where I take my direction.”

Crystal, who grew up in Inuvik, and also partially in a klavik, Tuktoyaktuk and s hingle point, tries to prioritize family time when she is not traveling. “When I come home and see the smiles on my nieces and nephews’ faces, I work harder, because I want to keep the smiles on their faces pretty. a nd I know that means we’re working for them, not just for ourselves and the older generation,” she said. Her parents’ dream is for her to achieve her degree, but Crystal might go further, especially after her accumulated experience of working in hospitals alongside doctors when she was in various positions with the Beaufort Delta h ealth and s ocial s ervices, as well as stanton h ospital.

“I have good parents,” said Crystal. “They’ve always encouraged me to go further in my education.”

“Maybe it’ll happen, I am still young enough. I am twenty eight, and Cindy Orlaw (first female Inuvialuit medical doctor) started back when she was twenty eight.” for now, Crystal loves her work and will wait to see where her life evolves when the funding for her position ends in 2010.

on July 10th s achs Harbour officially welcomed a permanent rCM p head quarters to the community. RCMP officers Todd Midgett and Eric Mc kenzie have been newly posted in s achs h arbour and have been working around the clock to establish a presence, introduce themselves to the community and come to understand life in s achs h arbour.

The rCM p were previously been in s achs h arbour from 1954-1992, their presence in many respects helped the area’s development as a permanent residence. In those days the rCM p integrated well with the community; hunting, trapping and keeping a team of dogs. n ow much of that lifestyle is unavailable to the newly placed RCMP officers, but they are still embracing and being embraced. Midgett said that “ s achs h arbour is a little paradise that very few people know about,” and Mc kenzie agrees, “people [in s achs h arbour] are tremendously friendly and supportive; it is so rare to have such a strong relationship between community and the rCM p. The people of s achs h arbour are so pro-police and so positive in their support of the rCM p.”

a ndy Carpenter, an elder of s achs h arbour and one time s pecial Constable for the rCM p, has been pushing for a permanent rCM p presence since they left in 1992 due to financial constraints. Though he recognizes success to be in large part a result of issues of sovereignty, he believes that the rCM p act as a deterrence to crime. “The rCM p play an important role in maintaining community values.”

a nd while he notes that s achs h arbour has very little crime, he says that “people generally feel safer when [the rCM p ] are here.” The rCM p, he says, play an important role in encouraging a sense of community.

Mc kenzie agrees and says that aTV use is the primary community complaint. a ndy Carpenter and his son r ichard say that they already notice a difference. Interestingly, many youth in the area have never known permanent rCM p presence with s achs h arbour receiving only intermittent visits from the Inuvik unit. When asked whether he was excited about the new arrival, Jeff kuptana, a young s achs h arbour resident for the summer, said he felt that the rCM p presence was very positive. h e was happy to have them despite the fact that he felt as if little had changed or needed to change.

The face of justice in the North is very versatile. Many communities have flourishing Justice Committees, relying on mediation and Elder participation. Though s achs h arbour has also experimented with such initiatives, for now they look to the rCM p and the mandate of education and community initiatives that they promote. Mc kenzie speaks of the rCM p dedication to working with the Community Justice Committee to reestablish a restorative Justice system to address and resolve minor offences outside of the courtroom. “This is a small community,” a ndy Carpenter says, “and ultimately people have to get along so there is a lot of forgiveness.” This stems directly from traditional life and the role that Elders used to play in regulating their communities says Joey Carpenter, son of one of the first Sachs h arbour families.

o ften the Elders would determine the appropriate response to any given conflict and then the whole community would heal and forgive. This is one of the most attractive aspects of working in the n orth for Eric Mc kenzie. h e feels that he can learn so much from a community about cooperation and living together in harmony.

prime Minister stephen h arper visited Inuvik and Tuktoyaktuk in the n orthwest Territories, and Dawson City in the yukon, for three days from august 26th to 28th.

During this short northern tour, he made announcements asserting Canada’s sovereignty in the a rctic, and held a high level federal cabinet meeting Inuvik.

In Tuktoyaktuk, Harper announced stricter regulations for sea traffic through the n orthwest p assage and other Canadian waterways. h e also announced that the a rctic Waters pollution prevention act will have its legislation range doubled to 200 nautical miles from the nearest Canadian shore. In Inuvik, h arper announced that a $720 million icebreaker to be named John G. Diefenbaker will be replacing the current icebreaker in 2017.

h arper met with aboriginal and territorial political leaders on his visit, including n WT premier floyd roland, I rC CEo n ellie Cournoyea, n unakput ML a Jackie Jacobson, and Tuktoyaktuk Mayor Merven Gruben.

While Harpers visit means increased publicity for the North and the Conservative(L-R) Minister Brendan Bell, Prime Minister Stephen Harper and Tuktoyaktuk mayor Merven Gruben. Inuvik airport: NWT Premier welcomes the PM of Canada. Tuktoyaktuk: The Tuktoyaktuk Drummers and Dancers performed for the PM.

“We would like to have had more definite support for infrastructure funding, like for roads or port facilities, or shore erosions. a nything that would help us immediately," said n ellie Cournoyea.

Tuktoyaktuk Mayor Merven Gruben agrees, noting that “I thought maybe it would have been a perfect time for him to announce the all weather road out of Tuk, as we will be pretty quiet this coming winter. Inuvik companies did get some work with MGM but that’s Inuvik. There’s nothing major for Tuk. These oil companies will have to realize that in the near future, most, if not all work will be in the Tuk area. Then they will be dealing with us.”

Merven also said that local residents would have welcomed the new icebreaker being named after a northern local hero, instead of a southerner.

“The prime Minister comes up, and here we are fighting with problems such as climate change and soil erosion, and yet he did not say one word on global warming. In fact, it was the reverse; he was talking about taking resources out of our land. We have so many other clean energy resources in Tuktoyaktuk, wind, gas -natural resources. There wasn’t a moment when he consulted with the people,” he said.

n unakput ML a Jackie Jacobson thought h arper’s announcements were a good start. “I think the Western a rctic will play a big part in a rctic sovereignty,” he said.

“The mayor, town council, community corporation [of Tuktoyaktuk] and myself, we met with him for about 30 minutes. We gave him our list of issues: the deep-sea port, the all-weather road, to try to get access for gravel source 177.” Jackie Jacobson said a bill was passed in the last legislative assembly budget sitting, allowing the G n WT to approve funding for the all gravel access road from Tuktoyaktuk to Inuvik.

“It’s in the federal government’s hands right now. a nd we let him know about the high cost of living for people in my riding, and how we need that road for our people to survive.”

Both the Mayor and ML a believe it is only a matter of time before the all-weather access road can be built, and are determined to continue pushing the issue ahead.

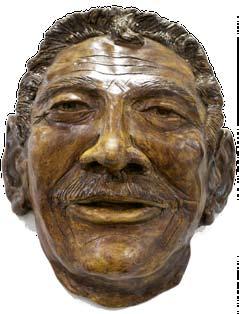

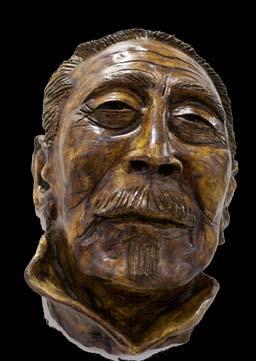

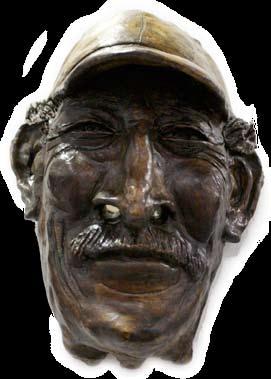

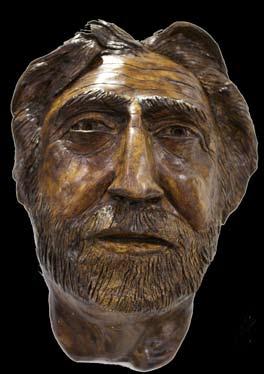

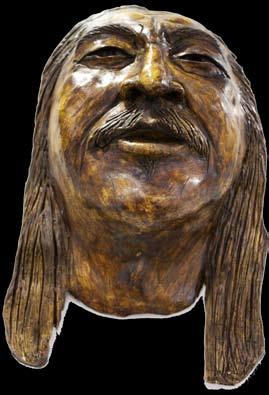

Tommy s mith grins as he looks at the ceramic mask of his face, on display as part of the “ f aces of the Elders 20th Anniversary Mask Project” during this year’s Great n orthern a rts festival. Tommy was chosen as one of the twenty elders to be honored for their contribution to the flourishing of the arts in the North. He has been a volunteer from day one of the festival’s launch two decades ago, and he is proud to once more volunteer as a logistics person. “I like to see the art work go up, and to meet the artists every year. It’s like a family reunion,” said Tommy.

s ome of the other familiar faces commemorated include Mary kendi and n ellie Cournoyea, as well as deceased, well respected artists s arah kuptana (seamstress) and Billy Thrasher (carver). a rtists from the Eastern Arctic were honored as well, reflecting the diverse make-up of talent at the Great n orthern a rts festival.

Mary kendi was surprised to see a mask made of her face, even though she too, had been involved with the festival from its beginnings. s he smiles serenely as she continues sewing, “It’s just fun, I’m happy about everything. I’ve enjoyed my trip. Thank you everyone for being so kind to me. Masi Cho.”

The Great n orthern a rts festival is the biggest arts event north of sixty, and has attracted artists and visitors from all over to explore and enjoy the vitality and beauty of Northern Art. This year’s turnout was especially robust, as many visitors came back to Inuvik to celebrate the town’s 50th anniversary.

Executive Director Tony Devlin and his team injected new life into the festival by bringing in performances and events that drew the audience back again and again over the ten-day festival. The headline concert with Lucie Idlout and the Bryce O’Conner Project set the tone for a rock ‘n’ rolling opening night, followed by equally exciting events such as the fort Good h ope Drummers.

Photos: Masks made by artist Harreson Tanner for the ‘Faces of the Elders’ project. George Roberts, Whitehorse Judas Ulluulaq, Gjoa Haven Magaret Vittrekwa, Fort McPherson Simon Tookome, Baker Lake Sonny MacDonald, Fort Smith Tommy Smith, InuvikThe audience got off their feet, moved to dance to their intricate and intense drum beats. James rogers and the Good Time Band also kept the audience dancing all night at the o ld Time Dance.

a variety of workshops during the days allowed aspiring artists to connect with established ones, and a variety of skills were generously shared, including soapstone carving by John s abourin to n etsilikmeot style Throat s inging with Mary Ittunga and Bessie u quqtuq.

The theme of this festival was “Homecoming” and the faces and voices of people who had lived and contributed to this region over the past fifty years were seen , heard and celebrated.

Les Carpenter, n ellie Cournoyea and roy Goose, who were radio announcers back in the day, went on air to share old stories about Inuvik’s years of building. These shows were broadcast live daily for four days by the CBC from the festival and Inuvik’s riverside. Dorothy Arey, veteran CBC announcer enjoyed hearing the voices of the ‘old timers’ again. “It’s a lot of fun to think back about how we lived long ago. It brought back a lot of memories for people, it’s good to hear again,” she said.

Those that attended the Great n orthern a rts festival this past summer would have witnessed something that has not been seen in a long while: an Inuvialuit qayaq being built by an Inuvialuit with local materials. Like qayaq building in the past, this was a family affair -- my husband, kevin floyd and I, Jennifer Lam working together. It was also a community affair with elders and locals coming to share their knowledge and support. We even received much appreciated local materials like sinew and wood from community members.

a s we unveiled our qayaq frame at the G naf closing ceremonies, I chuckled at how far we’ve come in such a short time. In the beginning of this year, we were living in n anaimo, BC, looking forward to a new chapter in our lives. a fter a four-month climbing trip that took us through the rockies and Western us , we looked northward. We arrived in Inuvik in a pril and loved it so much we decided to stay.

for many years, we have been researching the history of Canadian Inuit qayaqing. We found that much of the published information about traditional qayaqing is about Greenland Inuit qayaqing. We believe that there is a rich, deep history of qayaqing in the Canadian a rctic that is in danger of being lost. o ur Traditional Canadian Qayaq Project looks to recover local qayaq culture and re-introduce qayaqing to northern communities as a part of a healthy lifestyle, an environmentally sustainable way to explore this great area and as a meaningful, dynamic tool to connect with traditional knowledge and culture.

n o qayaq is made alone and no qayaq hunter succeeds alone. Many hands are needed to build the qayaq, both of men and women. Like the whale hunt who draws from a range of skills and expertise to capture and process the game, qayaq making draws from a range of knowledge as well.

Kevin’s journey to Inuvik began 37 years ago. His birth mother, a young Inuvialuit girl, gave him up for adoption to a loving family in Victoria, BC, where he was raised. o ver the years, he has continued to search for his roots. Clues slowly came and they all pointed to the adams family in Inuvik.

Thanks to an unexpected angel, kevin found himself at the doorstep of his nanaak, Lucy adams, within a day of arriving in town. When that door opened, Lucy learned of a grandchild she never knew she had and kevin found the key piece to his puzzle. Those that know Lucy adams, a much respected and loved elder, know of her kindness and good humour. We have been graced with both.

kevin’s search was not only for biological roots, but also his qayaqing roots. Like his Inuvialuit ancestors, he makes his living with his qayaq. u nlike his ancestors who made their living hunting, he makes his as a certified lead qayaq guide, instructor and outdoor adventure facilitator.

by Jennifer Lam

by Jennifer Lam

We found that within each step of the process were several challenges that led to knowledge that could not be gained from books, only from experiment and experience.

Building a qayaq at G naf was a rewarding experience. It gave us a great venue to share our knowledge and passion and to receive the same from others. We were overwhelmed by the warm support and enthusiasm.

Much of the materials for our qayaq came from local sources. The frame is made of wood from a log that came up the East Channel and the ribs are made with willow steamed and bent into shape.

Though power tools were used in roughly shaping the log into lumber, all the carving of the wood into qayaq parts was done by hand with simple wood block planes, a swiss a rmy knife, a handmade carving knife and good dose of humour. kevin even carved wooden wedges to use in splitting open the log and made his own jigs for the mortices.

There are no metal nails or glue, instead, sinew lashings and pegs were used to hold together the frame. The covering is made with canvas from fort Mc p herson, sewn with sinew and sealed with marine paint.

With only vague building instructions, kevin relied on his experience as a qayaqer to guide his construction process. h e also drew from a deep, ancestral intuition within for insight and ideas.

a round the world, qayaqing is a popular sport. u p here in the a rctic, it is more than just another hobby, it is part of a greater culture and legacy. It is here that the skills of rolling and sculling were evolved since one wouldn’t want to exit their qayaq into these frigid waters.

Its pivotal place in the whale hunt has evolved the qayaq into a sophisticated technology, even by modern standards. Even in modern hunts there is still a use for the traditional qayaq. a well-trained qayaqer can manoeuvre through waters and areas that larger craft can’t get through; it can approach game with stealthy precision and can cover huge distances quickly. The qayaq is a symbol of individual self-sufficiency within the spirit of community co-operation.

Our qayaq building demonstration is one step of a larger journey to spread the lessons of traditional Canadian Inuit qayaqing through the local Arctic communities, Canada and the rest of the world. We are currently starting a Qayaq club to teach people how to make qayaqs and pautiks (paddles) and also how to use them, including how to roll, scull and hunt in a qayaq. We are looking forward to taking part in a whale hunt in our qayaqs. Our plans also include a qayaq eco-tourism operation staffed with local qayaq guides. In the near future, we are planning to host international qayaq competitions and conferences up here in the north.

for more information please contact us at dancingbearadventures @hotmail.com

Kevin’s search was not only for biological roots, but also his qayaqing roots.

Like his Inuvialuit ancestors, he makes his living with his qayaq.Jennifer working on a paddle. All parts of the canoe are handmade. Kevin and Jennifer with grandmother Lucy Adams.

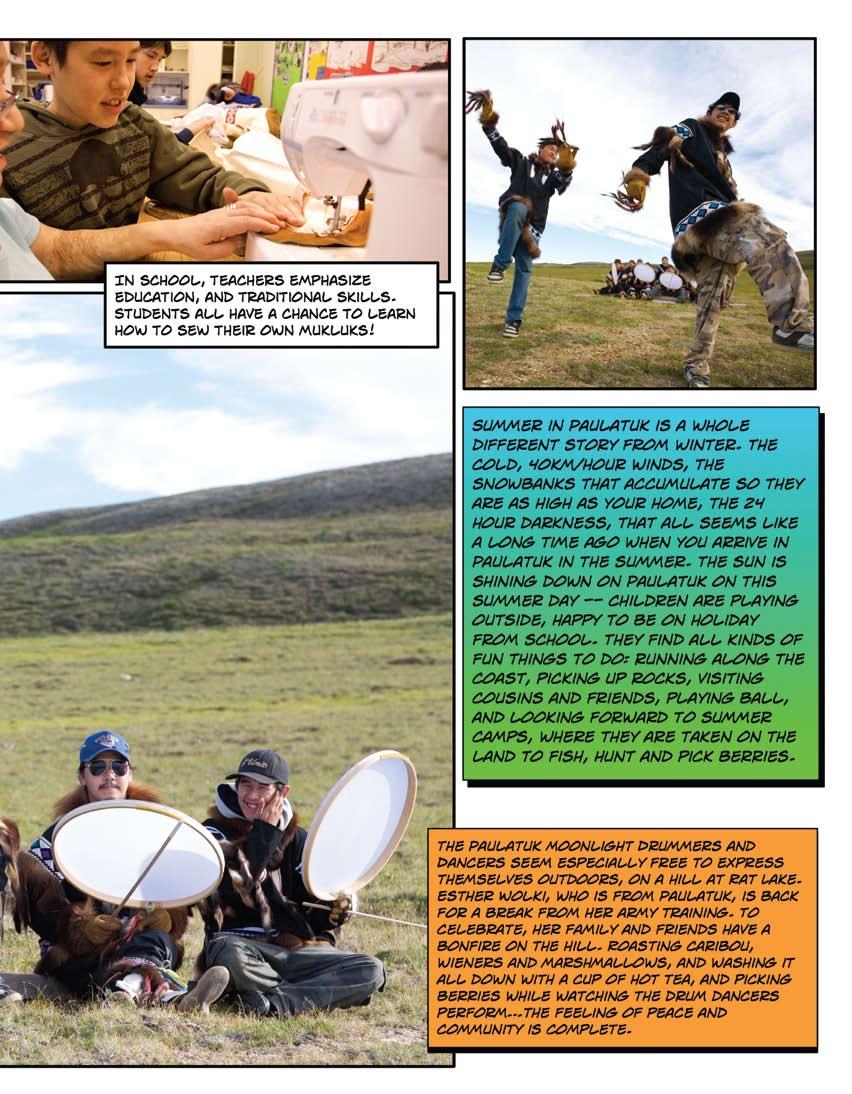

aboard the icebreaker a mundsen eight Inuit students held a silent audience enraptured, among them scientists, media, elders, and Inuit youth. s peaking of traditional knowledge and science, the students became representatives for the face of climate change and the face of activism and education. a s part of International polar year, the a mundsen hosted a program called “ s chools o nboard,” a chance for Inuit students from all over the circumpolar to collaborate and share with scientists in an effort to paint a more holistic picture of climate change in the north.

The student’s presentation was the culmination of a week-long session aboard the a mundsen with the hope of bridging science and traditional knowledge, attempting to carve out a path of communication and cooperation. John keogak, an elder participant from s achs h arbour spoke of the old days when researchers would come up to the north. “ researchers would do their thing and be gone, without any effort of communication. Things have changed for the better, and with cooperation much can be accomplished,” he said. Marko h olm from Greenland agreed, demanding that communities of the north want feedback from the scientists. h e said, “ s cientist must communicate their results to the community.”

During the week, the students shared information each had gathered from their respective homes about the drastic ways each community is experiencing climate change. Each were amazed that Inuit communities from russia, Greenland, a laska, and the Inuit s ettlement region are all experiencing similar changes: later fall freeze up, little multi-year ice, thinner ice, permafrost thawing, unpredictable weather, winds changing, stronger currents and wider channels.

James kuptana who currently lives in o ttawa but calls s achs h arbour home, stressed that as “an Inuk living in the s outh I have a responsibility to get this message out to people – to encourage change.”

Words by Lindsay TrevelyanJohn Keogak agreed, “If [climate change] keeps going we have no home; we are losing our culture, losing our ice, losing our lives here – this is very serious, it is going to change our life completely. It is good to see youth involved, this is their future to deal with; perhaps we can ease the pain of climate change.”

The message John was reiterating was that climate change threatens the future of the planet and presents a grave threat to traditional culture and lifestyle. This was also central to the discussion during the week of the “Schools Onboard” project. Prior to the presentation, s achs h arbour elders and the youth participants discussed methods of traditional knowledge transfer and suggested ways to improve youthElder exchange.

Logan Gruben from Tukotyaktuk spoke of traditional knowledge as something that is experiential. He said, “To learn to dry fish one used to be able to watch your mom or grandmother to explain what to do, we need to have more hands on learning.” Logan feels such learning will encourage a better respect for the environment.

To close the day, the elders, youth and a scientist launched a balloon with a G ps tracker into the ocean air. The balloon measures the humidity, temperature and density of the northern atmosphere. a s the balloon rises, it seems to beacon the collaboration underway on the a mundsen: a science that is participatory and inclusive, with youth, elders and scientists all working together.

Frank Issac Joe

September 22,1988

Though your smile is gone forever, And your hand we cannot touch. We have so many memories of the one we loved so much.

Your memory is our keepsake. With which we shall never part, God has you in His keeping. We have you in our hearts.

Forever remembered and loved by his children, Darlene, Doreen, Diane, Dwayne, Douglas.

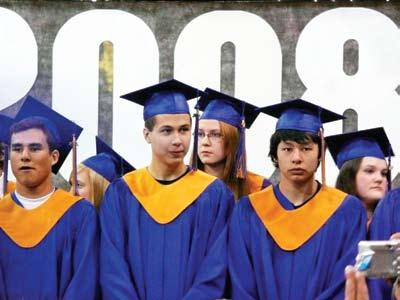

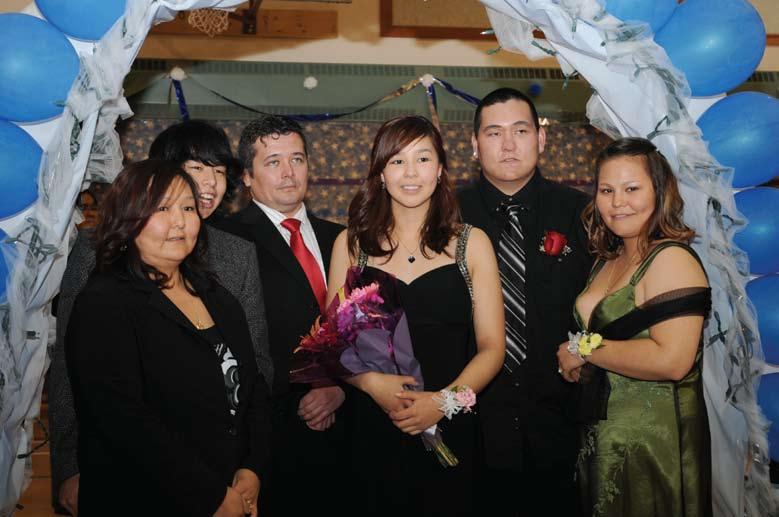

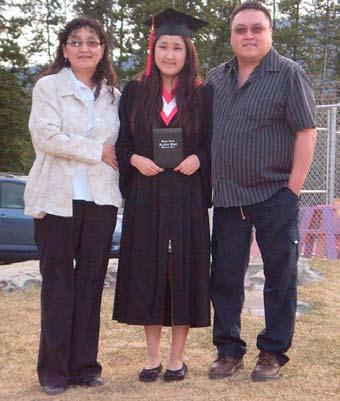

Merven Gruben shared with us this photo of Inuvialuit graduates from Yellowknife. This May, Sir John Franklin High School celebrated their 50 th anniversary and the graduation of 149 students. There were three Inuvialuit graduates, as well as some youth who formerly resided in Tuktoyaktuk.

Congratulations to Travis and Ryland Anderson, Kiefer Pokiak, Logan Andrew, and Justine Klengenberg!

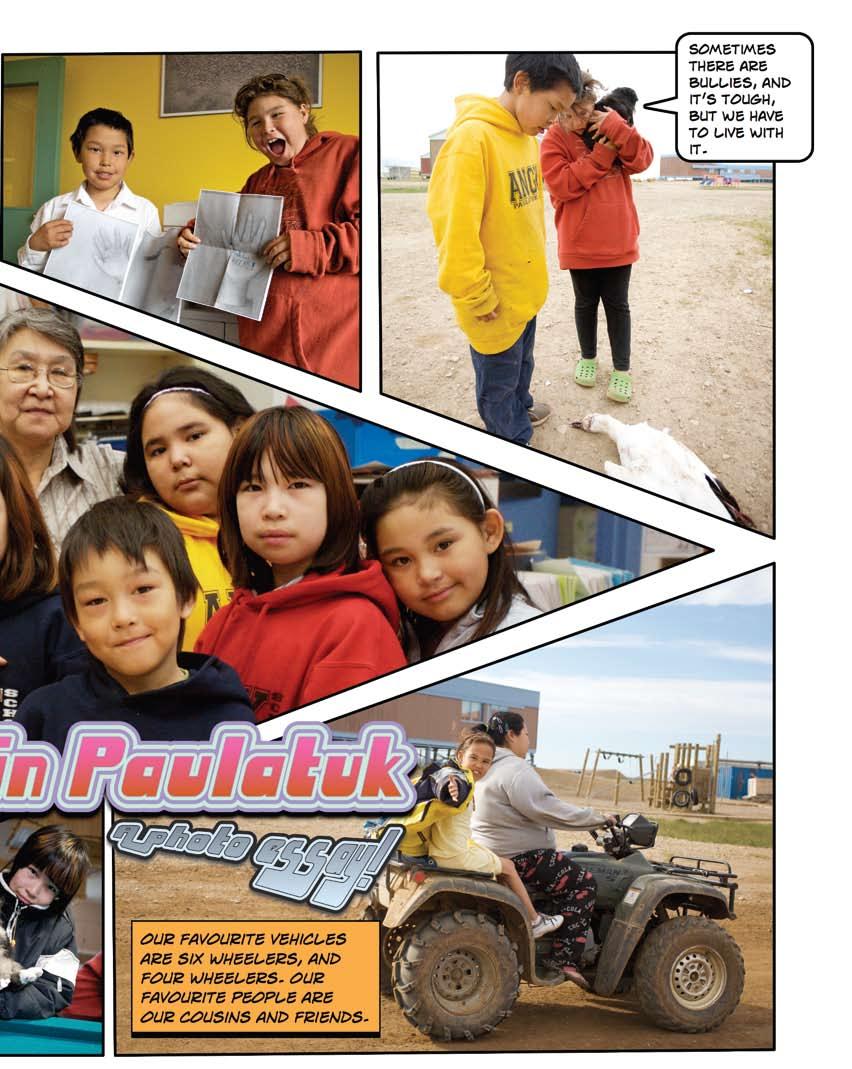

herb n akimayak had been traveling for the last decade. he is home in p aulatuk, at last, this year. “I was born and raised in p aulatuk until I was sixteen,” he said. “I went to Inuvik to finish my high school, after which I moved to Yellowknife. I’ve been working all over the n orth, and I got to work all over Canada.” h is work has taken him to revelstoke, BC, Iqaluit and Calgary. He has gained experience working in a variety of fields, including national parks, trades and development industries. he likes being part of big projects.

h erb feels his life outside of his community has increased his pride for his culture. h e even brought his two young children to p aulatuk. “I have my two young daughters with me. They live in fort s mith so I am giving them the oppourtunity to experience their culture. They are certainly finding it interesting. They’ve always wanted to build an igloo so this winter will be a cool time to do that,” he said.

It is important to him that his children have the freedom to explore and be proud of their culture. He believes it is easy to stereotype people and places unless you have lived there. “I think everyone is motivated in their own way,” he said. “A lot of people here are raised to hunt and fish. To them, that’s what’s important. They are making a living for their families.”

h e also values the community spirit in p aulatuk. “We all help each other, when we hunt we bring back food not just for ourselves, but to others who need it,” he said.

Last year, h erb was in a four-year entrepreneurship program in Calgary. “I am going back next year to complete that,” he said. This year, he is going to be home for his children and family. Even at home, he has many goals to accomplish.

h e is helping his father convert his business from big game hunting to eco-tourism. h e also took on work with the Inuit h ealth s urvey as the community research assistant, in the hope that it will help to make changes one day, to the lack of health care in the n orth. This summer, he also assisted the department of Environment and n atural resources with caribou monitoring.

He also goes out to fish and hunt whenever he can. “I’ve lived the life of an outdoorsman my whole life,” he said. “I don’t go to the gym, my gym is my backyard. I don’t get to spend enough time with my family, so I like coming back for some time. It makes me feel better.”

We asked if he felt conflicted between modern city life and the traditional ways at home. “I find myself in between sometimes,” he said. h e had originally moved because he “wanted change,” and “to see what’s around the corner.”

“It was refreshing to go out there, to see what’s going on, but there’s also a lot at home,” he said. “I feel more traditional every time I come home.”

“My father has been in the guiding business for about thirty years. h e started the business eleven years ago. I used to travel a lot with him so seems natural, to go from managing the lodge for him, to now running and owning it. I want to make it bigger and better than what it is,” he said. “The lodge will also be a good home for my parents to retire to, they can trap and fish just like they did a long time ago, except now they live in a house instead of an igloo.”

“When I am away from home, that’s when I feel stuck in between sometimes. But the days are getting better and better as I get older,” he laughs. His definition of success is not monetary, but holistic. “It’s about my well being,” he said, and getting involved with his community and family’s needs is part of getting there.

Words & photos by Zoe Ho

Isabelle Hendrick looks serious, as she wields her ulu and cuts off the head of a herring. She has been watching her sister, Ashline, help with the fourty fish that were harvested from yesterday’s net, and is excited to finally take part in helping out her nanaak (grandmother) with today’s harvest for the first time.

SIx-YEAR- OLD Isabelle Hendrick concentrates, as she wields her knife and cuts off the head of a herring. She has been watching her sister Ashline help with the forty fish that were harvested from yesterday’s net. Today Isabelle gets to help out her nanaak (grandmother) for the first time.

Isabelle first washes the fish in a bucket, then sets it on the table, where she is just tall enough to reach the work surface. h er bug suit, which wards off the swarms of mosquitoes that plague Whitefish Station during summertime, is covered with fish scales and stains from her hard work; but her pride is evident each time she hangs up a fish that she has readied for drying.

“I knew she could cut cut the head off, I didn’t know she could skin it, she did really good,” laughed nanaak Clara Day. “ s he even wanted to start making dryfish. I didn’t want her to try because she had a dull knife, I was scared.”

The small beach of Clara’s fish and whaling camp is just the right size for a maktak/ fish drying stand, a smoke house, a bench and a little white tent. We climbed up a small hill to her cabin, which is neat and looks out to an inlet, where beluga whales sometimes swim.

Behind the cabin is endless tundra, which the children love to play in. They took us on a hike to ‘Bum Lake’, where there was a split pingo that resembles its namesake. u p the river is their great-grandfather, Billy Day’s camp. Billy Day was celebrated for his love and protection of the environment and Inuvialuit rights. The children seemed to have inherited his ability to read nature’s signs.

They were able to tell us how to differentiate a seagull from a swan (“ swans have long necks and seagulls have short necks”) as well as which berries will cause belly ache (crowberries, the red ones that look like small cherries).

They also did a pretty good job imitating the calls of the cranes on the opposite shore. Brandon, who is thirteen, is already trusted to drive the fishing boat in the area. The adults have taught him how to observe the currents, and he can see a sandbar or currents that could pull a boat underwater. “My nanaak taught me so we can be safe when we go boating,” he said.

Clara believes it is important to educate the children respect their culture and to not waste. s he tries to speak in Inuvialuktun to the children, who learn by guessing what she said and answering. s he laughs, “When they say let’s get that squirrel I say no. If you do, you’re going to skin it and you are going to eat it. We were taught that if you don’t need something, don’t kill it.”

a ll the children agree that being on the land was better than living in town, where they mostly entertain themselves with computers, Bebo and electronic games. In contrast, they prefer their bush camp life where after a day’s work they can go find rocks, play baseball, go for hikes, as well fishing, visiting and swimming.

Ashline and Brandon pointed out wildlife and sights that at first we could not see.

“Look, there’s a heron! Are those caribou?

Waayy over there, see, they’re moving! There’s lots around.”

The heady aroma of cedar wood chips fill the dry fish smoke house as Rose stokes the fire.

The heady aroma of cedar wood chips fill the dry fish smoke house as Rose stokes the fire.

“Mmmn. Yummy!” said Ashline as she ate some cubes of maktak (beluga blubber).

They even say that “helping nanaak do stuff”, helping to haul wood and water makes them “more tough”. They admit they do not help out as much in town.

Brandon had his first chance to throw a harpoon this summer. “It was pretty awesome, and I like the part when I harpooned and it gets stuck into a whale. I was pretty scared of shooting a rifle because that’s my first time this year.”

The walls of Clara’s cabin are covered with signatures from visitors as well as milestones that her children and grandchildren achieve. “Long ago women and children never went whaling – women only prepared the whales after they are caught – the reason why women did not go – is if something happened out there, at least you have a parent home. It was like a jinx if the kids went and they were too young,” said Clara.

Today, rose Day, Clara’s daughter is as capable as any hunter. rose looks on the walls to find out when she had first harvested whale. “2004.” s he said. h er father and stanley, her boyfriend had taught her. “It was awesome. It was scary at first, following the waves behind the whale.”

“ first you see the current, but it’s far behind the whale, and you follow that. The whale will stay under but eventually it will have to come up for air, so when it comes up you try to harpoon it. I must have thrown the harpoon ten times the first time, until I finally got it. The harpoon jabs into the maktak and when it swims away, the pointy

head of the harpoon curves and stays in there. There is a long rope with a buoy tied to it, and that’s what we follow as the whale swims away. When it comes up for air, we shoot it. The whale sinks, but that’s why we have the buoy on it.” When the whale is pulled up on the shore, Dolly Sydney, the whale monitor for Whitefish station will be alerted to collect samples and to measure the whales. The one that rose got this week was 13 feet 4 inches.

Clara has nicknamed rose ‘Bush Woman’, because rose prefers to be outdoors than in town. Rose finds that “time goes by fast” on the land. rose said, “I’ll rather be outside, getting wood, burning garbage, getting water from the lakes.” s he is animated as she tells stories of watching coneys jump out of the water at her mother’s other bush camp, where five creeks meet. Even in minus forty degree weather, she likes to skidoo out to the bushcamp with her boyfriend. “It was so still outside, so cold, stars, clear skies, and the moon was very bright. I’m going to stay out on the land as much as I can until I get a job in town, enjoying the land, helping my mum, being here for the kids, I am loving it.”

Rose is also finding her social life changing. “a few years back I felt different,” said rose, “but from the experiences of staying in town, going to school, going south and working…now I just try to stay away from them because my boyfriend doesn’t drink…when I see them I just go sit around and have a pop…they’re used to it now, they’ll say have a shot and I’ll say I’m fine, I’ll just have my pop.”

Whitefish station used to belong to Clara’s mother, rebecca Chicksi, and coming back to it with her partner stanford, her daughter and grandchildren is like coming home. Clara tries to continue the tradition of sharing when on the land, giving five out of seven pails of her maktak to her extended family. Many people who used to whale at Whitefish Station have moved to Kendall Island, to escape the mosquitoes, which take advantage of the coves, which protect them from winds in the area.

It takes about four hours to travel by boat from Inuvik to Whitefish station, and so far, Clara has spent $1,300 on gas so her family could go whaling. “It’s not cheap, but it’s worth it,” she said. “I would spend a million dollars just to come down, for my grandchildren to have this experience.”

Ashline said, “It’s better here than running around in town, having fast food and junk food. There’s no gambling and no drinking, or being bad…or being worried about people and what we have to do.” Brandon added, “It’s boring to play Wii games once you have played it twenty times. It’s funner out here.”

In Inuvialuktun “aulavik” means “the place where people travel.”

This summer was no exception. p arks Canada staff travelled to aulavik n ational p ark to host a youth camp from July 8th to July 12th. Lisa h odgetts, an archaeologist working in the park offered to introduce local youth to archaeology during her project in the park. Three students from Inuvik and three students from s achs h arbour attended. k rysta rogers, o lympia Gillis- ross and rebecca k aufman were the students from Inuvik and accompanying them from s achs h arbour were kyle Wolki, steven Lucas and Isaac Elanik. It was a great opportunity for the students to spend time on the land, make new friends and learn about archaeology.

The students really enjoyed their time on the land. To add to their experience p arks Canada brought along Lena Wolki, an elder from s achs h arbour. Lena shared with them how and where she used to travel on Banks Island. s he talked about how everything had changed since she was a young girl and the challenges she had to overcome. s he said one of her biggest challenges was money. The students found this very strange. Why would she consider money a challenge?

As Lena would say “ it’s just a little piece of paper, I never needed it before, but now it’s what you need for everything.” It’s hard for us today to really understand what people went through to make that transition from living off the land, where everything you needed was there for you to just go and get, to living in civilization.

a big chunk of the youths’ time was spent team building. We played cooperative games so we could all get to know each other better. In these kinds of games, everybody wins!

The games make youth think together, work together and talk together. This was the highlight for all the youth on the trip, and everyone wrote about it in their journals.

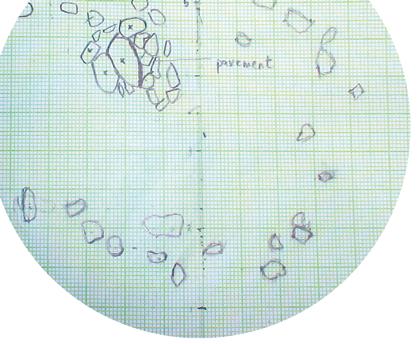

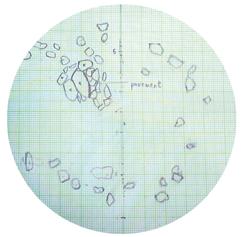

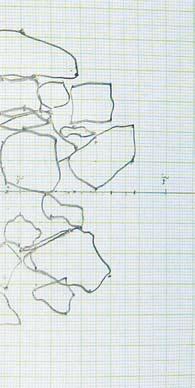

The group learned much from Lisa Hodgetts archaeological field crew. Lisa ( u niversity of Western o ntario) and her crew, spent the month of July in aulavik n ational p ark. for them, this was a pilot year in what will hopefully become a long-term study of past interactions between people, animals and the land on northern Banks Island. The main goal of the 2008 field season was to map unsurveyed archaeological sites surrounding the Thomsen r iver in the area around green cabin.

Over eighty new archaeological sites were mapped this field season, some with the help of the students. The girls from Inuvik were responsible for mapping a tent ring and the boys from Sachs Harbour were responsible for mapping a cache. Mapping the sites involves measuring the site and carefully drawing a map to scale of all of the items on the site. This took patience, thought and team work: both groups did a really great job. Their work will be included in the final report for the Archeological Project.

for Crysta, o lympia, rebecca, kyle, steven and Isaac this was the experience of a lifetime. They learned from an elder, researchers and each other. The youth camp held in aulavik n ational p ark was a success!

Lisa Hodgetts will be back in Inuvik and Sachs Harbour later this fall to discuss the preliminary results from the 2008 field season and to discuss plans for future work. She will give presentations in both communities on her project, what she learned this summer, and what she hopes to learn in the future.

The whole youth group with trip leaders. (L-R Back row) Melinda Gillis, Isaac Elanik, Kyle Wolki, Steven Lucas & David Haogak. Front: Crysta Rogers, Olympia Gillis-Ross & Rebecca Kaufman.

family and friends from all over crowded into the gym at Mangilaluk s chool to watch as eight fresh graduates accepted their diplomas on 29th august 2008. a s they marched on stage dressed in white graduation gowns and hats, you could see the pride these graduates felt about their accomplishment. p hillip n asogaluak could not begin to describe his joy. “It’s really great! I can’t even explain, but I just really want to celebrate,” he said.

The road to graduation was not always easy. It took a lot of hard work and determination. “It’s not hard to come to school but it is hard to get up in the morning,” said graduate n oah Gruben. he says he was able to graduate because he studied hard and never gave up, even though he says his English class was “pretty tough.” Graduate Kristy Anderson, who is the first female high school graduate in her family, admits that all the studying was difficult and the exams were pretty nerve wrecking but the results made it all worthwhile. “I am just happy that I could make my mom proud,” said a nderson.

Tuktoyaktuk Mayor Mervin Gruben and n unakput ML a Jackie Jacobson made it a point to be there for the event. With kind words of wisdom and advice, they wished the graduates all the best in the future. “The n orthwest Territories,” said Jacobson, “is one of the territories that is leading the country in developments. It has vast resources and you are the key to its success.” I rC chairperson n ellie Cournoyea, who also spoke at the event, urged the graduates to go further with their studies. o ther speakers included BDEC representative Camellia Gray, TCC representative robert Gruben, DE a Chairperson Jean Gruben and principal fred Butler.

Teachers Robin Hayslip and Janie Jones recalled stories from the graduates’ high school years. They spoke about the time when Noah Gruben “borrowed” a pair of his mother’s ivory earrings to give them to his teacher, just because he thought it would make her happy, and the early years when Charles Lucas, who they affectionately referred to as ‘Hugger-Man’, used to come into the school every morning and demand a hug from each and every female teacher.

With smiles and laughter resounding throughout the gymnasium, pleased parents and friends nodded in agreement at how far these graduates have come.

Many people played a part in getting these students to this day. Whether it was parents helping their children get to school on time, or teachers who pushed the students to hand in their work, the graduates were extremely thankful to them all. Each student selected a person they would like to thank, and presented them with a rose. for p hillip n asogaluak, the choice was easy. “My teacher, Janie Jones, was such an inspiration to me. I’ll always remember her classroom as a classroom of perseverance. I learnt a lot about myself in English class.”

a s the night was coming to a close, Charles Lucas was chosen to give the student address and his advice to the class simple. “This is just the beginning and the future is open to us all.” In front of proud parents and supportive friends, they walked on stage as high school students and they left graduates.

“We’ve loved, laughed, cried. We’ve lived life.”

Charles Lucas

“The world awaits you, make the best of it.”

Principal fred ButlerCharles Lucas receives his diploma from principal Fred Butler. Charles and Noah, proud graduates pose with family and friends. Maia Lepage photo

Tuktoyaktuk’s Mangilaluk s chool celebrated eight graduates this august 2008. English teacher Janie Jones recalled her favourite memories of her students, one of which is nineteen year old Loni n oksana.

“I’ll always remember the day when Loni successfully handled grade 12 level work,” said Janie, “ s he was reading and writing at a grade 12 level, even if she was still in grade 11. I remember her standing at my desk with her work, and I remember the happiness we both felt.”

“at the grade 12 level Loni, at a grade 12 level!” The teacher exclaimed. a s always, Loni’s reponse was a calm smile. Even today, her graduation day, Loni was well composed. h er eyes shone when nostalgia and pride hit her as classmates and teachers spoke. Loni said her parents have taught her to be even tempered. “I’m a Christian,” she said, “so I can’t be mad with anybody!”

Loni will miss her home community when she begins her new job. “I love Tuk. It’ll always be my home,” she said. She has enjoyed being on the land with her family growing up. “We always went to Taaqaaq, Husky Lakes, to camp and fish,” she said.

Always planning ahead, Loni has a job lined up even before her graduation. “I have a job in Inuvik,” she said excitedly, “I will be teaching pre-school.”

h er dream has always been to work with children. While in school, she held the position of assistant recreation coordinator for the hamlet.

Loni was able to bring many great events to the youth, holding teen dances and karaoke nights for them. Even adults had game nights. Loni liked the communication between adults and the younger generation.

“at home, my family speaks in Inuvialuktun if there are elders around,” she said. Her father, David Noksana Sr. leads outfitting sports hunts. “I’ve seen hundreds of bears,” she said, “I’ve seen him lay them out in the garage, and take out their teeth. I am never scared,” she smiled.

“I love kids,” she said. “I play with them and listen to what they are saying. I realize that once they’ve talked a lot they will open up.”

might not be french, but she makes a succulent Cordon Bleu: stuffed chicken breast with bacon and swiss cheese and mushroom sauce. s he is chef at the a rctic Char Inn, and the dinner she is serving tonight has both looks and flavour.

Julia laughs, “I like being cook, I have learnt a lot from Martin, there are so many ways of cooking I had never seen before.” Martin, who is french Canadian, has been teaching Julia how to make gourmet meals.

This is especially interesting to Julia, as the local n orthern store usually offers little to the imagination in terms of ingredients. Martin has shown her how to make basic ingredients into delicious dishes. o ne of her favourites is turning potatoes into seasoned wedges.

“I didn’t know you can first boil them, and then fry them,” she said.

“I don’t buy anything at the store,” she said, “only chicken and pizza. I like to harvest my food myself. It’s exciting to go on the land to harvest, I like doing fish and cooking outdoors.”

Julia’s creative sewing and artwork is also well known in u lukhaktok. Even with her job as chef at the hotel, she continues to sew. “I like what I am doing at the hotel, and if I am not working, I am sewing,”

she said. This week, she is putting together a batch of zipper pulls, miniature mukluks and mitts that she plans to sell in Inuvik.

Life is expensive in the North, but Julia finds creative ways to make do, like selling her work in Inuvik while she brings her children there for medical check ups.

youngest is 21 months old.

h er oldest boy tries to show his appreciation for her by taking care of her. “ h e’s a teenager now, so it’s exciting. h e is the man of the house, he hunts and works to make a living. h e tries to buy me things, but I tell him to save it for himself,” she said.

Julia tries to incorporate tradition into everything she does. s he speaks in Inuvialuktun to her children. s he said she kept her language by taking care of her parents and grandparents. When harvesters sell their harvest to the hotel, she is glad to make traditional dinners such as muskox stew and stir fry.

“

I’ve been offered a job as camp cook in 2010. I am taking it. I need to go to work to make a living for my family, but I don’t mind,” she smiles. She has a boy and three girls, the oldest is fifteen and the

Honestly! is a new column in Tusaayaksat. How do you say, ‘Honestly?’, do you stretch it out ‘Hoooneestttly!’ like we Northerners do? This new column is all about our common knowledge; we will be discussing with northern youth their honest opinions on issues that impact them. Our first topic to be handled is suicide. We believe with more openness and discussion, everyone will feel better and honor their lives more!

according to an Inuit statistical Profile postedv on Inuit Tapiriit k anatami’s (ITk) website, the Inuit suicide rate is more than eleven times higher than the overall Canadian rate. We asked u lukhaktok youth Trevor o kheena to talk to young people in his community, to find out the factors that they see as causing suicide. The youth of u lukhaktok also came up with some suggestions and solutions for the issue.

Reported by Trevor Okheenas uicide seems to happen in northern communities for many reasons. Drugs, alcohol and even relationships can be triggers leading to suicide. There is a vicious cycle. When you are a teenager in high school, you tend to stay out late on school nights, and want to sleep in the next day.

That leads to decreased attendance. you start dropping classes and then get kicked out of school. It is hard enough to try to find a job around here, you do not have much of an option in terms of careers. Some people think of themselves as useless. If they cannot get a job. If parents begin asking if their children are ready to find a job or move out soon, that leads to more stress.

relationships are the best and the worst of one’s experience in small northern communities. There can be the happiest couples, and in contrast also the angriest couples. When you are a teen you try to have many relationships while trying to find the one person who truly makes you happy.

When you find that ‘special someone’, you tend to fall hard. Everything seems to be going fine, and all of a sudden it all falls apart. When the deepest love that you have ever felt is unrequited, either with the one you love kissing somebody else, or if the other person only wants to be friends, your heart feels broken like it never has been before.

You might run away in tears, hoping to find someone you can trust to share your personal feelings with, but you might find that hard, because in a small community, so many of us are related. We might

find it hard to trust someone to not betray your secret. o bsessing about the problem by ourselves can make it seem worse, we might give too much importance to a failed relationship, mistakenly believing it was our only chance.

Gossip can spread pretty fast in a small community, even if the gossip is not true. The person being gossiped about will try hard to find out how it started, but sometimes the gossip can go around for days, weeks, even months. This could lead someone to think of suicide.

In our community, we have close friendships amongst small groups of people, beginning from when we were very young. h owever, that could change as we grow to like different things. When friendships change, and people stop talking or looking at each other, the other person almost seems to not exist anymore. That does not last long, we soon begin missing and thinking of the best friendship we once shared, and hoping that we could undo the mistake we made.

Justine Okheena says, “Do something, or go somewhere that keeps you from staying in too much, from thinking about alcohol and drugs. You could try to get a youth center in our community, so people could have someplace they would like to go.>>

are

on challenges, excercise, and talk

others!

Do sports outdoors or at the gym. Don’t do reckless driving. young people in our community usually stay in, play poker and smoke weed because there is usually nothing else to do in a small community. If there is something we can do to stay active then everyone would be healthy.

“If you’re thinking about suicide, you can get help. Just talk to someone that you know, that you can trust. There are a few examples of people you can trust: your best friend, a social worker, school councilor, your teacher or even your parents. Take it one step at a time, you know in your heart you will feel better eventually.

you can’t always run away from your problems. Deal with them. It’s life. you will learn from your mistakes. Just let people know how you are feeling. Get it out. Talk to someone and you will feel better. stay away from drugs and alcohol. It won’t do you any good.”

Micah Okheena said, “ s uicide is something most youth who live in northern communities have thought about. It may seem like the easy way out, but it isn’t. Most youth start doing drugs and alcohol at an early age, and after the first experience, they will want more, because they feel there is not much else to do. s chool is important, but sometimes it feels boring because we don’t have enough courses to choose from. The youth here need something to keep us busy, like a youth center and more sports. s uicide doesn’t need to happen.”

Crystal Kuneyuna said, “I grew up around a suicidal father. The best thing to do is to let people know how you are feeling. Talk to someone (not just anyone, but someone you trust) who will understand how you are feeling in that moment. Don’t leave someone who is feeling down alone.”

Go to www.honouringlife.ca

or call the Inuvik Suicide Crisis Line Phone: (867) 777-1234

Monday to Friday, 5 p.m. - 8:30 a.m. or check out http://www.kidshelpphone.ca/

Congratulations to r ichard Cockney and Katrina Gruben, who celebrated their wedding day at Kitti Hall in Tuktoyaktuk on August 8th, 2008.

— With love, your family and friends

With many thanks to Maureen and Merven Gruben for their assistance

Eddie and the dog team that he describes as ‘the dogs who made me millions.’ He began his transportation business with only a dog team over five decades ago.

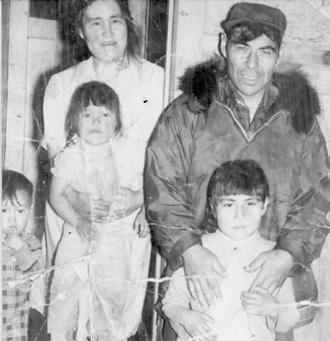

Itwas a bitterly cold spring in 1924. Angnaeennaq, a young Inuvialuit woman traveled with three starving dogs, and two equally hungry children, one aged five (Eddie), the other aged ten (Diamond), from Tuktoyaktuk to Saunaktuuk. The thirty-mile journey was arduous. As the woman became tired, her children would try to push ahead to help the dogs. The younger boy remembers that his mother had only snow to eat.

The first night they camped at Amittuuq, before a big hill. The shelter his mother built was two snow-blocks high, with a canvas over the top. When they woke up the next day, they kept walking to s aunaktuuk, where they camped again in the cold. a ngnaeennaq, decided to make three fishing holes along the sandspit. The five-yearold boy was the first to hook a fish. It was too heavy for him, so he called his stepmother, and she pulled it out. That day they caught over thirty fish. The three took their fish back to their shelter, eating it raw. They felt so good and strong. “ n ow we are rich,” said the young boy.

The young boy was Eddie Gruben. Today he is eighty-eight. The lessons from his life are remarkable. h is daughter Maureen Gruben has been taking notes when her father reminisces, and the story above is one he loves to tell.

Eddie’s self-made company, E. Gruben’s Transport Ltd. is now a multi-million dollar enterprise specializing in construction, transportation, and services for the oil and gas industry. The company has major holdings in the Mackenzie Delta Hotel Group, Storm Communications, and Horizon North Logistics, and has offices in Inuvik, Tuktoyaktuk, Edmonton and British Columbia, employing over 250 employees during peak work season.

Even though Eddie is current more ‘rich’ materially, than when he was at age five, his maintains a simple lifestyle. His meals are mostly made up of fish and caribou, and he is grateful each time he eats country food. He says his greatest achievement is being alive to enjoy his family life, with his many children, grandchildren and great grandchildren.

o ne of the notes Maureen took reads: I remember everyday of my life since 1924. I was born in 1919. I sure have seen a lot of change in my life -- from the hard way of living, fighting for survivial, to modern day living. I know both sides of life.

Eddie’s life began with ‘hard living’. h e was born about 7 miles from the mouth of the river at k ittigaruit. h is father was John Gruben, a German man who came to the Western a rctic with whaling ships in the 1800s. he managed the h udson’s Bay trading post at k ittigaruit, a summer whale camp and gathering place for the Inuvialuit. h e was only in his early twenties, when he met Eddie’s mother in the Delta. Her name was Mary (Talromek). She was about fifteen years old.

“I was two days old when I was adopted by a couple in Tuktoyaktuk (a ngnaeennaq, and p aniksak),” said Eddie. “They wrapped me up in a deerskin, I was brought over with a dog team, and my [adoptive] parents had a log house right here [on a small pingo in Tuktoyaktuk].”

During the epidemic flu in Aklavik, Eddie was seven. He remembers being asked to run down to the river to get water for people, who were dying in their tents. There was a young four-year-old girl helping him. The next day they would check on the people they brought water to, and find them all dead. The young girl, Alice Cockney, would later become his wife.

Eddie went to residential school in h ay r iver. When the Great Depression hit Canada in the 1930s, the schools sent many students home. Eddie was in grade four, and had become orphaned. “I had no home, my step-parents were dead, my grandparents were dead,” Eddie said. a Caucasian trapper, Gus Eastanak, asked Eddie to come trap with him at kuaaluk. They would travel by Gus’ boat, the Goldenhein. Eddie still remembers Gus saying, “ h ey, boy, do you want to come with me? you won’t be lonely. There’s lots of other boys to play with. you can use my boat and I’ll teach you how to trap.”

The lonely boy grew strong and self-sufficient. Somehow, he was driven by a belief: everybody had it within himself or herself to survive and to make good of their lives. h e became an excellent hunter and trapper.

“It never cost me anything to raise my kids,” he said. “a lice would make the clothes and patch them. Behind every man is a good woman, and if you have a good woman to come home to, it makes you work harder.”

This year, E. Gruben’s Transport Ltd celebrates officially its 35th anniversary, but Eddie’s business was begun more than two decades before that.

Eddie adapted well to change. In the winter, when the rCM p needed dog teams to travel by, Eddie was hired as a guide from Tuktoyaktuk to Bailey Island. In the summer he made dry fish that the RCMP would buy for food and for their dogs.

“I am an inquisitive person. I like to ask, no matter to who, how did you do that?” When the old Mangilaluk s chool was built in Tuktoyaktuk, Eddie asked the truck driver how much he was paid per load. “When he told me it was $15 a load, to me it sounded like a million dollars.”

“I thought if they could do that, I could do it too. I was a good trapper. I made a lot of money trapping.” at a fur auction in Edmonton, Eddie was able to make enough to invest in modern equipment. “That’s when I bought my bombardier snow mobile.”

This bombardier, bought through the rC missionary f ather ruyant and the rCM p, made him even more money, and he was able to buy a gravel hauling truck next. o ver the next decade, Eddie was able to watch for opportunities brought on by oil exploration and government construction, and to reinvest his earnings into more assets, and more ways to accumulate profit. While other businesses might seek to purchase by credit, Eddie was proud that he was able to purchase trucks, front-end loaders and C aT machines without borrowing. When people working on the DEW Lines needed goods transported to them, Eddie would travel for eight hours on his Bombardier from Tuktoyaktuk to a klavik, in order to deliver.

“That’s how I started,” he said. “I used to work day and night in those days, I always really worked hard. I made every dollar from my hard work, I used my head for my teacher.”

When the oil and gas industry began its boom in the n orth, Eddie’s company boomed too. “ from there, there was no looking back, we just kept on going. Now it’s one of the biggest companies in the whole n orthwest Territories, Gruben’s Transport,” said Eddie.

Eddie is fiercely independent. He refused to live in government housing when it was offered to him. Instead, he lived in tents, and then in a hudson Bay h ouse a lice bought with her earnings from the furshop. Eventually, he built a million dollar log house in the same spot his adoptive parents had built theirs. While he built his business, he also hunted and trapped for his family and others in his community. Eddie’s son Bobby and James worked alongside him in his business endeavors, while his daughters took care of his secretarial work, the bakery and the camp.

In the early 1970s, Eddie met a young man who paddled to Tuktoyaktuk from h ay r iver with a kayak. “ h e was 19 years old, from n ew york,” said Eddie. “There were three of them traveling together, and they had a tent with a fire outside. They were roasting fish, but they had no bread. Before they left, someone had told them to come visit me, so they came when my wife had just finished baking. They ate a loaf each, hot bread and butter!”

russel n ewmark would stay in the n orth and become an integral part of Eddie’s management team. Eddie is proud of his team: made up of russel, James Lay, his oldest grandson Merven Gruben and head foreman Bob stefure. They were able to take Eddie’s business to the next level. The company is still a family owned business.

“I helped so many people out. That’s why I was blessed. I gave myself to the people,” said Eddie. h is company continues to support

“

I made dryfish for the RCMP, ” he said. It was a profitable business. “Honestly nobody taught me how to start the business. I watched so many guys from down south come up here in big trucks, all kinds of machines, and we in Tuk, we had nothing.”h usband and wife team: a lice and Eddie Gruben worked hard to provide for their family. Eddie takes a break from fishing with the first Bombardier snowmachine he purchased.

n orthern initiatives for youth and sports, as well as employ and train many northerners. It is now the biggest company in the n orthwest Territories.

Eddie and many members of his family continue to live in Tuktoyaktuk. h e believes “There’s no place like Tuktoyaktuk,” especially after his extensive travels. “ you get all kinds of animals here,” he said. “ s o much moose, caribou, beluga whales, seals, polar bears, geese, and so much wood, whole pieces, even logs.” Many of his children and grandchildren continue to contribute community, including one as a teacher and Merven Gruben, vice president of the company, is also mayor of Tuktoyaktuk. Eddie is proud of all his nine children, and encourages his family to believe in the philosophy that “ n o matter what color, what race, we are all alike. a nd your mind is your teacher, it’s all in your mind, it’s just a matter of using it.” He celebrates the achievements of his two grandsons, s heldon Lundrigan, a pilot for Canadian n orth and Toby stefure, who is training for his commerial pilot’s license.

Merven Gruben said, “I am really proud of my grandpa. He sacrificed a lot to make life good for us. h e’s at the age now to be retired, and to be well looked after.” a s for the business, Merven said, “We look forward to the future and the future looks good.”

Taavyumani 1924 upinngaami qiqauvialuktuaq. Angnaeennaq, arnaq nutauyuaq Inuvialuumiblunilu aulamayuaq qimmiliyaqluni pingasunik qimmini payanapittillugit, malrungniktauq nutaralik kaaktuaktauq, atausiq tallimatun ukiulik, tugliaptauq qulitun ukiulik atinga Diamond Tuktuuyaqtuumin Sauniqtuumun aulamayuat. Thirty-milestun aulamayuat ayurnaqtumi. Arnaq taamna yarangasigami, nutaraalungik ikayuqniaqsimayait qimmit. Nukatpiraaluk taamna itqariyaa amaamani apunmik nirimagami allanik niqiksailam. Tanmaatqaaqtuat Amitturmi, qimiryuam satqaanun. Amaamaa igluliuqtuaq qutchiksilugu malruktun avguqtanik apunmik qaangagun aasiin tupiqsamik iliyiblugu. Ublaakunngurmaung tupagamik, pisuakkiqtuat Sauniqtuumun, tamaani tanmaaqtuat qiqimi. Angnaeennaq isumaliuqtuaq pakkaliurukluni pingasunik tamaani tapqami. Taamna nukatpiraaluk tallimanik ukiulik iqaluktuaq sivullirmik. Uqumaitpallaaqlugu, amaamaksani ququakkiraa, amaamaa nutqiblugu piyaa. Pingasuuyuat aasiin uqquutiksamun aggitiyaat iqaluk, uilaqtuqtuat iqalungnik. Nakitqiyuat aasiin nakuruklutik. “Umialinnguqtuanni,” unniqtuaq nukatpiraaluk.

Taamna nukatpiraaluk atqa Qarisaaluk. u bluq, eighty-eightun ukiuniktuaq. Ilisaangit inuusimingni marlangnaqtut. p ania Maureen Gruben aglaksimayait aappani quliarman itqaumayanginnik, una quliaq quliaruuyaa nakuugiblugu.

Qarisaaluk savagviliuqtuaq inmiguaqłuni, E. Gruben’s Transport Ltd. a ngivialuktuq savagvia qangma akiruaqtuq multi-million dollartun savaaruaqtuq piliuqlutik sunik, aulaviksaniklu, savaaruaqluiglu uqsiqiyinun. Ilaumayuat savaamingnik ukuanik pimablugugulu tamatkikapsainik ukuanik Mackenzie Delta h otel Group, storm Communications, h orizon n orth Logisticslu, aglagviruaqlutik ukuani Inuuvik, Tuktuuyaqtuuq, Edmonton, British Columbiamilu, savaktiruaqtuat 250tun savaksait inugiaksimmata ilaanni.

Qangma Qarisaalum inuusia ayupsangaittuq, taimanitun inngituq tallimanik ukiuruaqtiluni, inuusiruaqtuq qangma sapirnaittumik suli allangasuitpangniqtuaq. n irisuuyuq suli iqalungniklu tuktuniklu, quyasukpaktuaq nirimagami niqiptingnik nunamin. Quviasuktuaruuq inuugami suli ublumi quviagiyait ilangit iqatigimagit, nutarait, inrutaalungitlu inrutaalutqiutingitlu.

atausimik uvva aglaamingnik taiguqtuaq Maureen: Inuusira puiguyuitkiga 1924mingaaniin. a niyuami 1919 ukiungani. Inugiaktuanik takuyuami inuusimni allanguqtuanik – sapirnaqtumin inuusinik, qangmamun aglaan nutaani inuuniarusinun. Ilisimayunga tamainnik inuusingnik.

Qarisaaluum inuusinga sivunrani ‘sapirnaqtuaq’. a niyuaq tallimat malrungnik milestun paanganin k itigaaryuum kuunganin. a appaa John Gruben, Gamaaluk qaiyuaq u allinirmun arvirniaqtigun 1800ni ukiungani. n iuvvaayauyuaq h udson Bayiitkuni k itigaaryungmi, auyami tamaani Inuvialuit qilalukkiarviani katimagiaqtuqpaktuatlu tamaani. Taimani ukiuruaqtuaq twentiesnik, tatdjvani Uummarmi takuyaa Qarisaaluum amaamaa Mary Talromek. u kiuruaqtuaq nutaublunili fifteentun.

“Malruktun ubluruarama tiguuyuami Tuktuuyaqtuuq (a naraatchiaq and p aniksaq),” uqallaktuaq Qarisaaluk. “ u liktitaani qunngium amiinnik, ikaktuami umiamik, tiguuvikka igluruaqtuak qiyuvialungmik maani [pinguqsaaryualungmi Tuktuuyaqtuumi].”

Taimani fluuqpaalungmata Akłarvik, Qarisaaluk tallimat malruktun ukiuruaqtuaq. Itqaumayuaq quliutimmatdjung imiqtariaqublugu kuungmin, inuinnun tuqunapittuanun imitqublugit. a ngnaeennaq sitamatun ukiuruaqtuaq ikayuqsimayaa. u blaakunngurman takuyaqtuqpagait imiqtittuanun, paqitpagait tuqungayuat. n aluniqtuaq taamna arnaaraaluk atinga a lice Cockney (nuliurutiyaa aasiin seventeentun ukiunirman).

Qarisaaluk ilisariaqsimayuaqtauq ilisarvingmun h ay r ivermun. Taima aasiin Inuusiq tamainnun s apirnaqsiyuaq k anatami 1930sni, ilisarviit inugiaktunik ilisaqtuanik aggitinigait nunaminun. Qarisaaluk ilisaqsimayuaq sitamani ukiuni, iliappanguqłunilu. “Aimaviruanngituami, ilakka tuquyuat, tiguuviikka tuquyuat, ataataakka tuquyuat,” Qarisaaluk taimaliyuaq. u uma naniriaqtuqti tanaaluk Gus Eastanak apiriyaa Qarisaaluk naniriaqatigisuklugu kuugaalungmi. aulavaktuak Gus’gum umianganik, atinga Goldemhein. Qarisaaluk itqariyaa suli Gus uqallangman, “ n ukatpiraaluuk, aulaqatigisukpinga? a liasulaittutin. n ukatpiqqat inugiaktuat piuyaqatiginiaritin, umiara atulagin ilisautiniaripkin naniriaqturnirmik.”

a liasuktuaq nukatpiraaluk suangamuktuqtuaq inmigun munarilasiblunilu. Qanuqlunikiaq, ukpirutiruarniqtuaq: tamaita inuit sunngurukkumik sunngulayuq inuulasibluni nakuuyumik. n aniriaqtinguqtuaq anguniaqtinngurlunilu ilimmaariksilugik.

“ n utaqqatka inugurniarapkit akiruanngittuami,” uqallaktuaq. “a lice annuraaliuqpaktuaq ilaaqtublugitlu. a ngutit tamarmik nakuuyumik arnaruaqtuat, arnaruaruvit nakuuyuamik, taimannaptauq savavialugungniaqtutin.”

u vani ukiumi, E. Gruben’s Transport Ltd ilimayuaq 35th ukiuni, aglaan Qarisaaluum savaanga isagutiyuaq sivuani qulini malrungni ukiuni.

Qarisaaluk allanguqtillugu inuusiq inmiptauq maliksimayaa. u kiumi, a maqqut qimmiliruaqtuanik qinirmata aulasukkamik, Qarisaaluk aullautivagait Tuktuuyaqtuumin u tqalungmun atuqtitpagait qimmini akiliusiaqluni. auyami, pipsiliurutivagait a maqqut niuviqpagait qimminunlu niriksamingniklu atuqlugit.

“a maqqunun pipsiliuqtuami maniksitillunga taimanna,” uqallaktuaq. “a llam ilisautinngitaani savaamnik isakkaarama. Takunnakpakatka inugiaktuat tanngit nunaannin qaimayuat aksaligyuamik aqublutik, allagiiktuanik aksaliganik, uvaguttauq aasiin Tukmi, suittugut.”

“ u vanga ilisimasukpaktunga sunik. a piqsisuuyunga sunik, kinaliqaamun, qanuq pivakpit taimanna?” Mangilaaluum Ilisarvia napinmatdjung Tuktuuyaqtuumi, Qarisaaluk apiriyaa aksaligaqti qanuqtun akiliusiarman nunamik usiarman. “ u qallautigaminga $15tun akiliusiaqtuaq atausirmik usiarman nunamik, uvamnun million dollarstun ittuaq.”

“Isumayuami taimanna pilangagumik, uvangaptauq taimaliulayungaptauq. n aniriaqtulguyuami. Maninnaktuami naniriaqturama. Tunimmagit tuniyiviksamun Edmontonmi, niuviqtuaq allanik aksalikkamik bombardiermiklu.”

u na bombardier, niuviqtuaq rCiit minisitangatigun f ather ruyant suli a maqqut maninnaktigiyaat angiyumik, taimana niuviqtuaq usiarviksamik uyaraliamik aksaligaqyuamik. Qulini ukiuni aasiin, Qarisaaluk savaaksaniktuaq uqsuryualiqiyuani kavamanilu, maniksinnami niuvipsaaqtuaq allamik taimannaptauq maninnaksibluni kiilumik. a llat savagviruaqtuat inmikun niuviyuitpangniqtuat inmikun, Qarisaaluk marlaktuq inminun niuviramitigit inmigun atugaksamik qiniyuittuq niuvirami aksalikkamik, front-end loadersniglu C aT ingniqutainiklu. s avaktuat DEW Linesni aulaviksanik qinirmata, Qarisaaluk aullautivagait aulabluni tallimat-pingasunik ikaarnini Bombardierkun Tuktuuyaqtuumin Akłarvingmun, usiaqluni sunik.

“Taimanna aullaqiyuami,” uqallaktuaq. “Taimani savakpaktuami sivitiyumik ublumilu unnuamilu, savavialukpaktuami. Maniksatka savavialuklunga piyatka, isumaga aturiga ilisarama.”

u qsiqiyit niuqtuakirmata n unagiyaptingni, Qarisaaluum savagvia aglimuktuaq $70 milliontun atausimi ukiumi. “Taimangaaniin nutqangittuanni. Qangma anginiqsauyuq allanin savagvianin tamainnin n unatchiami ittuat, Gruben’s Transport,” imaliyuaq Qarisaaluk.

Qarisaaluk inmiguaqluni pivaktuq. k avamat igluanun nuutchungituaq qaitchiniaqtilutik. Tupirmi inuuniaqsimayuaq, aasiin a lice niuviqtuaq iglumik h udson Baymin akiliusainginnik miqurvingmun akiliblugu. Igluqpaaluliuqtuaq aasiin qiyungnik akiruaqtuanik million dollatun suli iliyaa tiguuvingik iniyaaluanginnun. s avagviani aglimuktuqtillugu naniriaqtuqpaktuaq anguniaqlunilu savautilugit ilangitlu inuuniaqatingitlu. Eddie’m irnaak Bobby Jameslu savaqatigiyaak savagviani, paningittauq ikayuqlugu aglagvianilu, niqliurvianilu savagvianilu.