Tusaayaksat

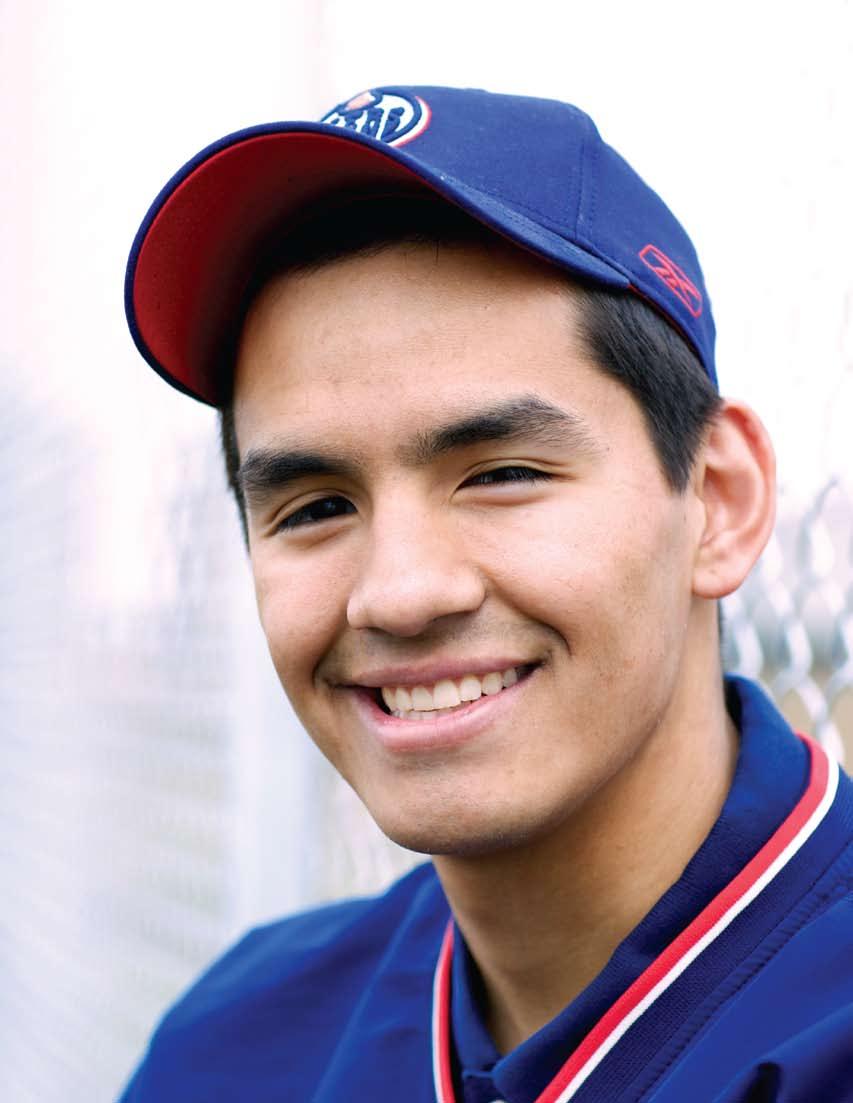

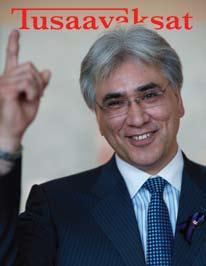

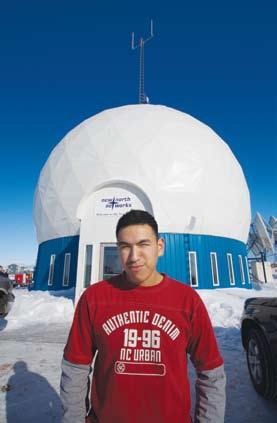

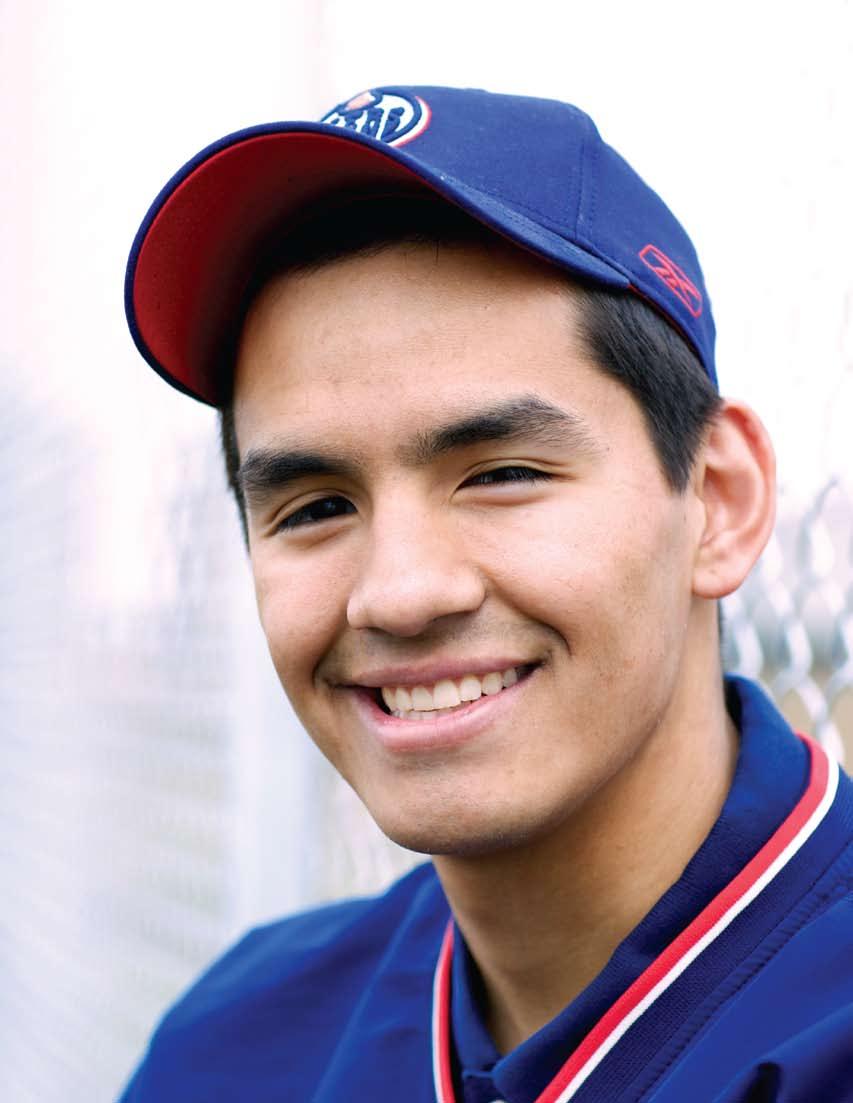

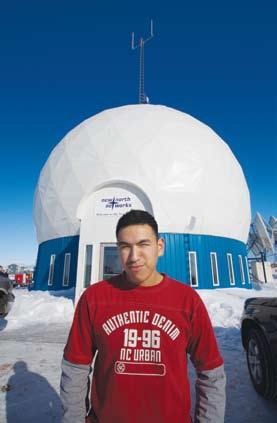

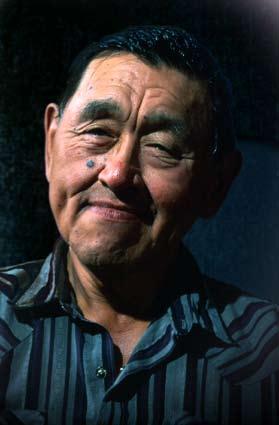

Kyle Kuptana

Kyle Kuptana

National Aboriginal Role Model

ISR Graduates!

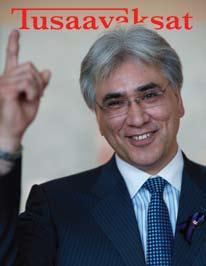

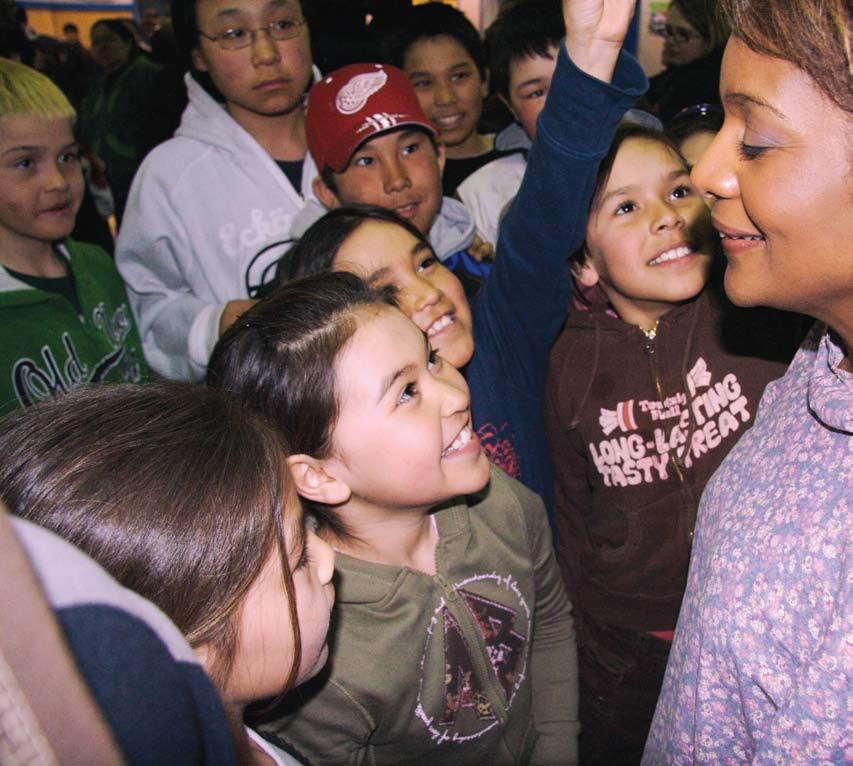

Governor General Visits Inuvik + Tuk

Climate Change discussion on the Amundsen

DREAM BIG!

Volume 22 Number 3 SUMMER 2008 $4.00 Inuvialuit News + Culture

Tusaayaksat

2008 Quyanainni Volume 21 Number 6 September/ October 2007 $2.50 something new to hear about horton river builds character new mexico soccer gold andy carpenter & cope ivvavik inspires northern fashion show inuvialuit professionals Volume 22 Number 1 November/December 2007 $2.50 something new to hear about NWT Premier Floyd Roland O N TOUGH LOVE Elders Helping Scientists STOKES POINT CLEAN UP Jessie Colton: RENEWING TRADITION Literacy Lives Here Curfew in Inuvik Capacity Building FOR RESIDENTIAL SCHOOL SURV VORS YOUTH MONITORING CARIBOU something new to hear about Volume 21 Number 2 January/February 2007 $2.50 Paulatuk Moonlight Dancers Mary Evik Ruben Canada Winter Games Caribou Workshop Beluga Harvest Venturing For th: Dez Lo een Esther Wolki Children’s Contest! Inuvialuit RCMP Volume 21 Number 5 July/August 2007 $2.50 something new to hear about From the Arctic to Germany! GraduationSalutations! NelliePokiak:Collegeisforallages! Bushcamps Past and Present Inuvialuktun Language Immersion Ulukhaktok Kingalik Jamboree something new to hear about Volume 21 Number 3 March/April 2007 $2.50 Going for Gold Inuit Games at the Canada Winter Games Edward Lennie, Father of the Northern Games IRC Native Hockey Cup Edmonton Special: Achieve Your Dreamz Moving South for a Change Larga Home Away from Home Sachs Harbour Environmental Monitoring Course Caribou Summit Inuvialuit Guardian Angels Ulukhatok Revives Printshop Lila Voudrach Phillip Jacobson something new to hear about Volume 20 Number 2 March/April 2006 $2.50 something new to hear about Volume 20 Number 3 May/June 2006 $2.50 MUSKRAT JAMBOREE 2006 AGNES FELIX LOVE POINTERS SELF-GOVERNMENT YOUNG MUSKRAT TRAPPER REPORTS KURT WAINMAN THE GREAT NORTHERN CIRCUS MAKTAK STIR-FRY IRYC PICS! AWG WINNERS HAPPY BIRTHDAY EMMA DICK! & Lots More! something new to hear about Volume 20 Number 4 July/August 2006 $2.50 NELLIE ON TRADITION & CHANGE REINDEER UPDATE DRIMES TRADITIONAL ARTS INUVIALUIT DAY YOUTH RAP TO BUTT OUT JAMBOREE IN TUK, AKLAVIK & ULUKHAKTOK PETROLEUM SHOW & CLASS OF 2006 GRADUATION! something new to hear about Volume 20 Number 5 September/October 2006 $2.50 Beaufort Delta Residential School Reunion Mary Simon's Vision for Inuit Great Northern Arts Fest Jordin Tootoo visits Edmonton Jacob Archie on Trapping New Legislation for Tuktoyaktuk Hunters Tony Alanak to teach Fiddling Cindy Voudrach + Confidence Lanita Thrasher Flies High Top of the World Film Festival something new to hear about Volume 20 Number 6 November/December 2006 $2.50 Emma Dick "It's Good to Wake Up in the Bush!" Christmas Greetings from the ISR What do we want? Safe Homes! Iqalukpik Jamboree Margaret Lennie Inuvialuktun Writing System CN Rail Memories Kendyce Cockney "John John" Stuart & The Tuk Youth Center The Bomber Pages! Children’s Story & Contest Inside! Volume 22 Number 2 SPRING 2008 $4.00 Inuvialuit News + Culture Tusaayaksat Ulukhaktok drum dance reunion Sachs Harbour muskox harvest Nellie’s commitment IRC Hockey Cup highlights Good news for Ulukhaktok Artists For advertising and subsription inquiries, please email us at tusaayaksat@ northwestel.net or call 867 777 2320. Tusaayaksat o ur goal: to celebrate and showcase the voices of Inuvialuit across Canada, bringing you the best coverage of our news, vibrant culture, and perspectives. Thank you for your supporT. Please support us by advertising with us. We offer advertising discounts to Inuvialuit businesses.

3 Publisher Topsy Cockney Inuivaluit Communications society, Executive Director Editor/Writer/ Creative Dir. Zoe ho Tusaayaksat {is Inuvialuktun for “something new to hear about”} Inside: Contributors anne Crossman Markus siivola Lindsay Trevelyan pat Dunn simon routh adam k. Johnson Proofreading simon routh Photography David stewart Zoe ho Design, Illustration, Layout & Typography Zoe ho Translation LIllian Elias ICS Board of Directors President foster arey, aklavik Vice-President Joanne Eldridge, sachs harbour Secretary-Treasurer sarah rogers, Inuvik Directors stan ruben, paulatuk Joseph sr. kitikudlak, ulukhaktok Jimmy komeak, Tuktoyaktuk 10 {Special Feature Nuitaniqsaq Quliaq} Content Highlights ISR Graduates! In The News Tusaayaksani 70 ResidentialCanada’sApologyto School Survivors In The News Tusaayaksani 52Ottawa Bureaucrats Meet the North In The News Tusaayaksani 24 ClimateChangePolicy MeetingonAmundsen 30 50thAnniversary ofInuvik SpecialFeatureNuitaniqsaqQuliaq 62 GovernorGeneral BringsMagictoISRSpecialFeatureNuitaniqsaqQuliaq We acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Canada Magazine Fund toward our editorial costs. Printing Quality Color Identical twins Lekeisha and Shayala Elias graduated together from SAM School’s kindergarten program!

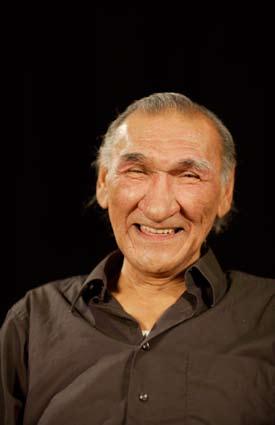

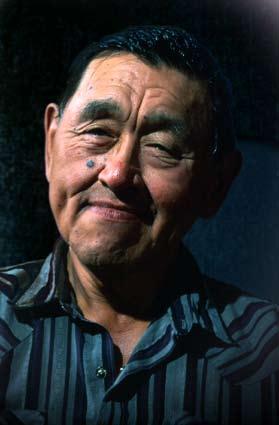

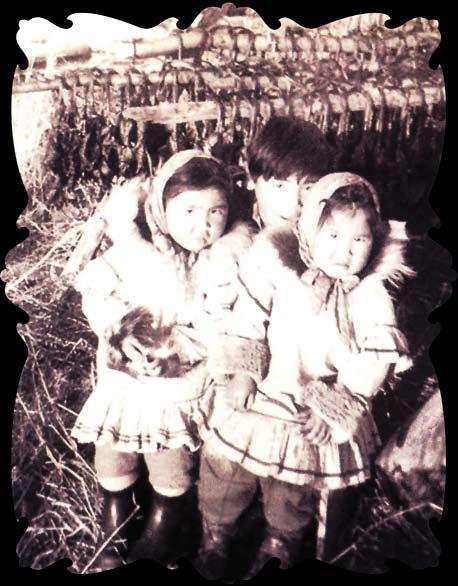

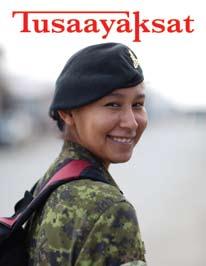

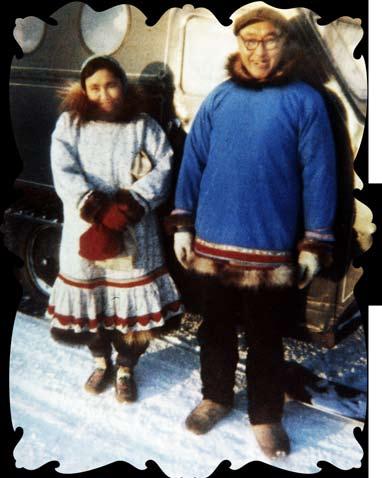

Kyle Kuptana is definitely going to remember this year’s Aboriginal Day. His day began in Ottawa, where the Governor General of Canada, in partnership with the National Aboriginal Health Organization, presented him with a National Aboriginal Role Model award. Kyle is one of twelve recipients chosen from among Inuit, First Nation and Metis youth all over Canada to receive this award.

James Makokis, spokesperson for the Aboriginal Role Model Program, and National Aboriginal Achievement Award winner said, “First Nations, Inuit, and Métis youth are choosing to lead healthy, active lives and succeeding in all areas, including the arts, humanities, commerce, politics, sports, science, and technology. Role models are authentic individuals who are true to their identities. They give others the courage to push beyond their own potential, opening the door to new possibilities.”

Kyle was nominated by his peers, as were the rest of the award winners. “I’d like to thank the person who nominated me,” he said. “I never thought I’d be chosen. I've always thought of myself as just another person to pass on the wisdom. Now that I’ve won, I won’t change anything; I will continue to do what I do.”

TUSAAYAKSAT SUMMER 2008 4

As a strong athlete who has won numerous awards in sports such as arctic games, soccer, baseball, and hockey, including national awards. Kyle is generous with his time when it comes to helping other young people get active. His generous spirit means that young people learn to play like him, for the love of the game, and not only for the sake of winning. Last year, Kyle coached a team of about twenty youth from Tuktoyaktuk, Aklavik, and Fort McPherson in minor baseball. He found the youth responded better to his guidance, as he knows them and is close to their communities.

“They usually respect and listen to me,” he said of the youth he coaches, “They know that if I was not there, there is nobody else to coach them in baseball. Also, many of them are my brother’s friends, they come over to my house all the time.”

This summer, you will continue to see him coaching young people in baseball and soccer on the small community field in Inuvik. He will also be assistant coach for Team NWT at the North American Indigenous Games held this August in Cowichan, British Columbia. The head coach is his father, Donald Kuptana. It was Donald who had encouraged Kyle to start coaching.

After his graduation from Samuel Hearne Secondary School, Kyle is now pursuing a Natural Resources Technician Program at Aurora College in his hometown.

“It’s a fun course. We learn about botany, combining traditional and scientific knowledge,” he said. “I hope to work for ENR (Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources).” He is interested in this career path as he loves the outdoors. Born and raised in Inuvik, Kyle is not thinking about leaving.

“I want to stay here and contribute to the community. I like it in a small town, there’s no panic to get anywhere, you know everyone and I feel safe here,” he said. “I hang out with a lot of people who don’t like staying in town, but I don’t see what the problem is. We have more freedom here than people living in cities, we can go out to nature, which is calm and soothing, such as fishing in Husky Lakes.”

It is especially Kyle’s ability to stay strong in the face of peer pressure that makes him vital as a role model. When asked what he thinks about drugs and alcohol, the substances that young people often abuse due to peer pressure, he said, “I’ve no use for it. I’ve never tried.”

The life of a young aboriginal person is not an easy ride, especially in a small town. There are tragedies and circumstances outside of their control that cause some to turn to substance abuse. Kyle too has to deal with loss, but he said, “Many people drink or do drugs to deal, but we [he and his girlfriend] keep busy. I like playing baseball better than having a beer any day.”

Words and photography by Zoe Ho

“ Youth Speak Up Nutaqat Uqaqtut

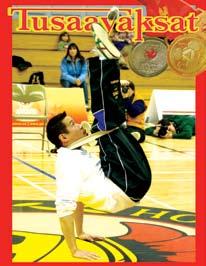

Kyle practicing at Inuvik’s Ruyant Ball Field.

The 21st of June is the day of the summer solstice. It was a perfect day to celebrate under the midnight sun.

TUSAAYAKSAT SUMMER 2008 6

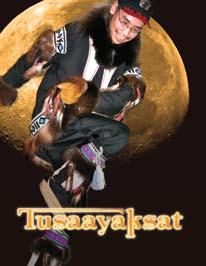

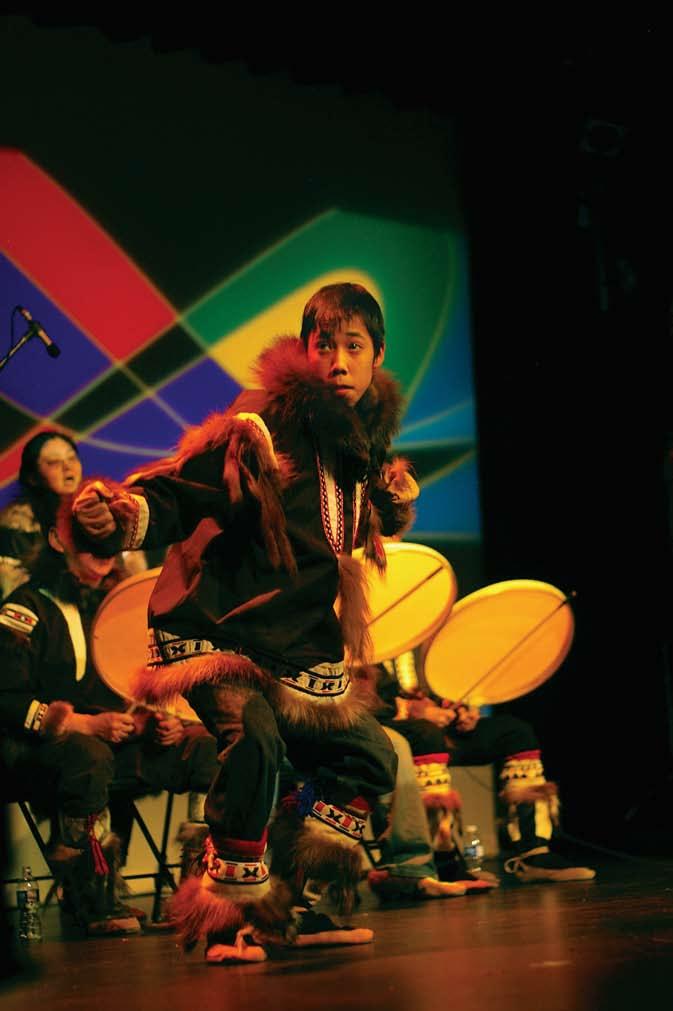

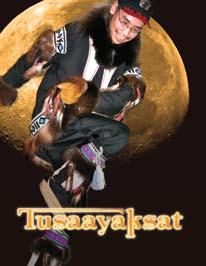

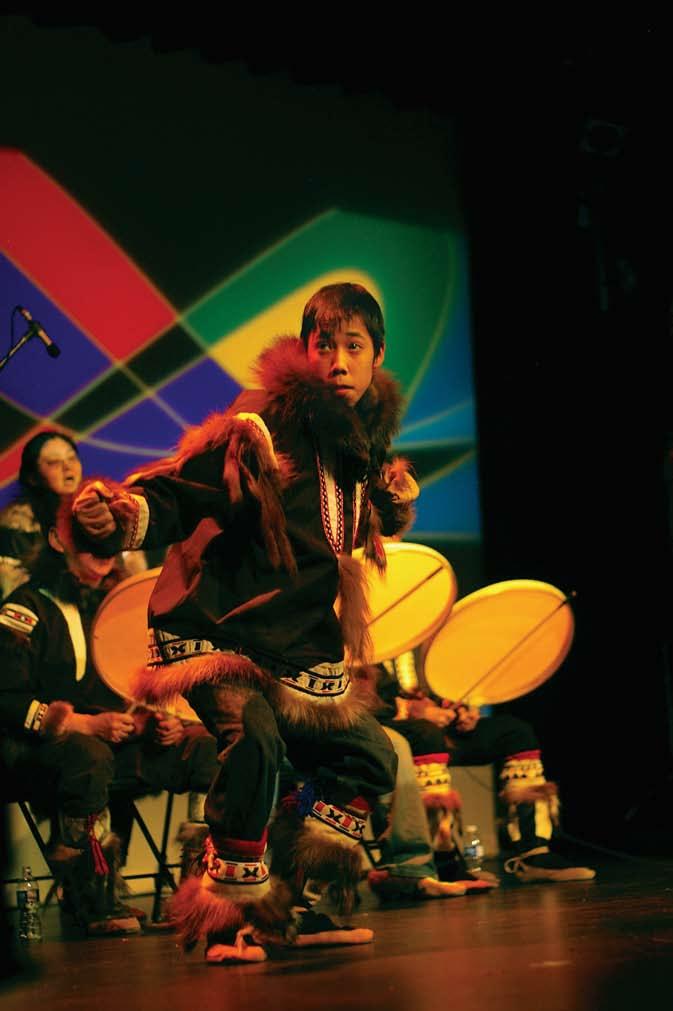

The Inuvik Drummers and Dancers took advantage of the large stage at Jim Koe Park to give an outstanding performance to a full audience.

Special Feature Nuitaniqsaq Quliaq

Aboriginal Day 2008

Photography by David Stewart

Itwas a time to celebrate culture by dancing and making music. Youth, children, and adults all joined in. Elders square danced, played guitar, and sang their hearts out. There was also a feast, with country food such as roasted fish and muskrats.

TUSAAYAKSAT SUMMER 2008 8 Special Feature Nuitaniqsaq Quliaq

Children lined up for fire engine rides around town.

9

Graduation, Here we come!

Jumping for joy: Cole Elias, Lane Voudrach, Isabelle Hendrick, and Skyla Kagyut are part of the kindergarten graduates who sang a song about how fun it was to be going from kindergarten to grade one.

Words by Lindsay Trevelyan

Photo by Zoe Ho

Jumping for joy: Cole Elias, Lane Voudrach, Isabelle Hendrick, and Skyla Kagyut are part of the kindergarten graduates who sang a song about how fun it was to be going from kindergarten to grade one.

Words by Lindsay Trevelyan

Photo by Zoe Ho

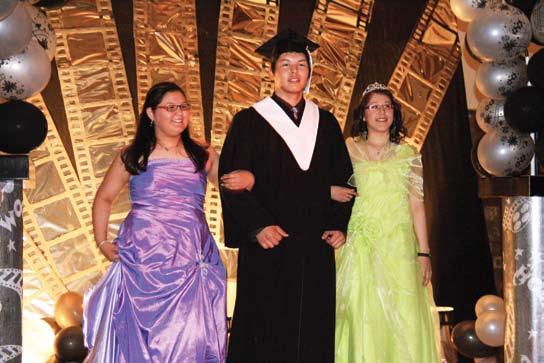

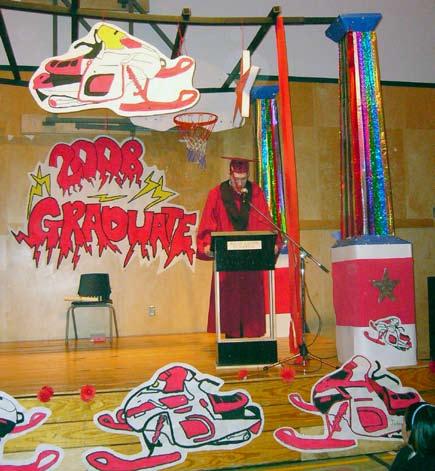

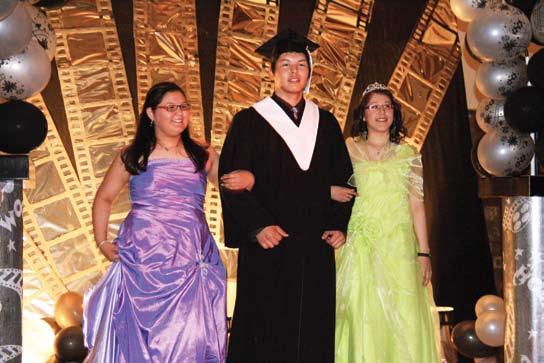

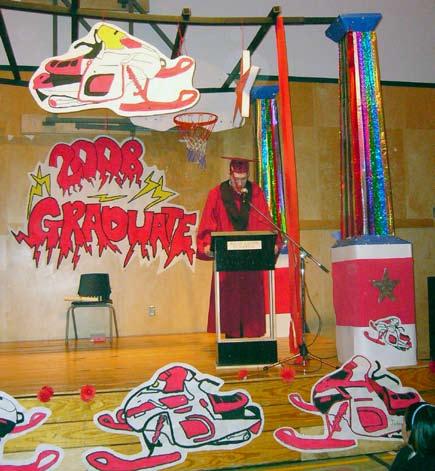

Grad glamour: Aklavik graduates chose a Hollywood theme that is echoed in many of the graduation celebrations around the Inuvialuit Settlement Region.

ats amuel h earne s econdary s chool

in Inuvik the graduates were eagerly hanging stars from the ceiling, and creating star-budded decorative trees awash in sparkles and balloons –the air was thick with anticipation. Every detail would be tended to, cared for, and made perfect. In Ulukhaktok, floors were waxed, speeches written, and food prepared. In p aulatuk, the gym was meticulously beautified to toast the achievement of their two graduates with a visit from n ellie Cournoyea, Chair of the I rC. a savoury ham, turkey and roast dinner topped it all off. In s achs h arbour at Inualthuyak s chool k indergarten Graduation and awards Ceremony, a blue and purple cap and gown was worn by each little graduate with pride. s imilarly, s ir a lexander Mackenzie s chool graduates in Inuvik wore gold caps and tassels, a detail made possible by the dedicated fundraising of the recycling club. In a klavik at Moose kerr s chool, graduation every inch was old h ollywood; arches of black and silver balloons, miniature film cameras, stars and pillars lining the graduate's official red carpet, all accented with a disco ball to set the sparkling tone.

Watching and learning: Pre-school children are entralled by the photo slideshow of SAM School graduates.

Throughout the Inuvialuit s ettlement region (I sr), June and July is the time for graduation ceremonies, each rewarding the diligence and dedication of the graduates. n one was sweeter than the graduation of Jonathan kudlak, u lukhatok’s sole graduate. h is advice to his peers and his twelve-yearold sister aiming for similar accomplishments: “keep getting up in the morning, go to school everyday, and work hard.” Each graduate interviewed gave very similar advice and there is no question that it has paid off. When asked about his upcoming graduation, Jonathan said he was speechless – but he was far from speechless come graduation day, where he delivered an address to the proud audience, among them his elders, his teachers, mother, father, grandmother, and his kindergarden teacher, all of whom played a key role in his success.

11

This is the face of graduation in the North: excitement, happiness and the culmination of hard work, and deserved celebration. Ranging in size from a single graduate to 40 accomplished students, each of these graduations mark a very special day.

Special Feature Nuitaniqsaq Quliaq TUSAAYAKSAT SUMMER 2008

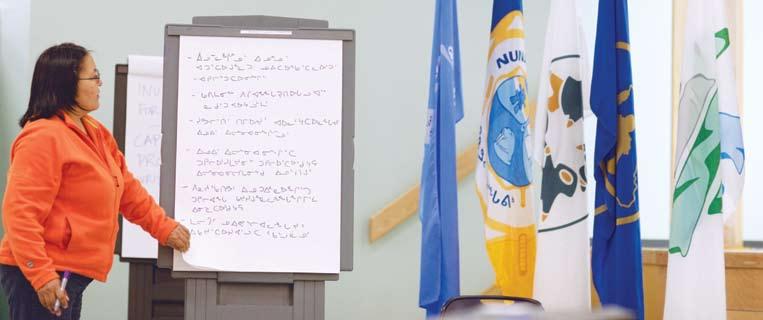

Photo by Chris Yapp

Photo by Zoe Ho

Photo by Chris Yapp

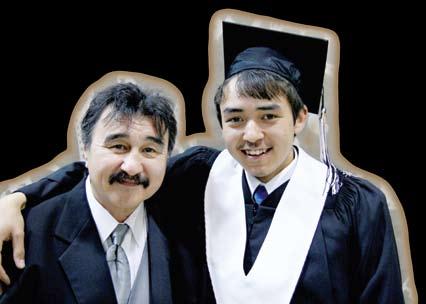

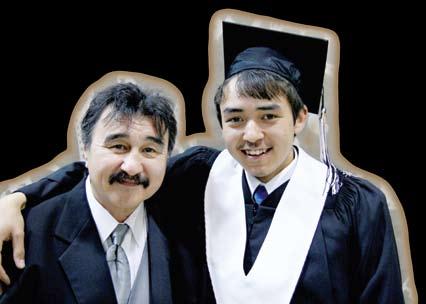

Below: Richard Tardiff Sr. and his son, Richard Tardiff Jr.

Celebrating with family: Kristin Elias, Cindy Stewart, Chelsea Elias (SAMS grad), and Lillian Elias.

The level of formal education and highschool graduates has been steadily increasing across the n orthwest Territories. In 2005, the graduation rate exceeded 50% for the first time ever, and the strongest growth in graduation rates in the last twenty years have happened in the n orthwest Territories.

u nderstanding upgrading and higher education as crucial for shaping their futures, and the future of the n WT, many of the graduates of 2008 intend to keep learning, applying to schools and colleges across the country or closer to home.

In

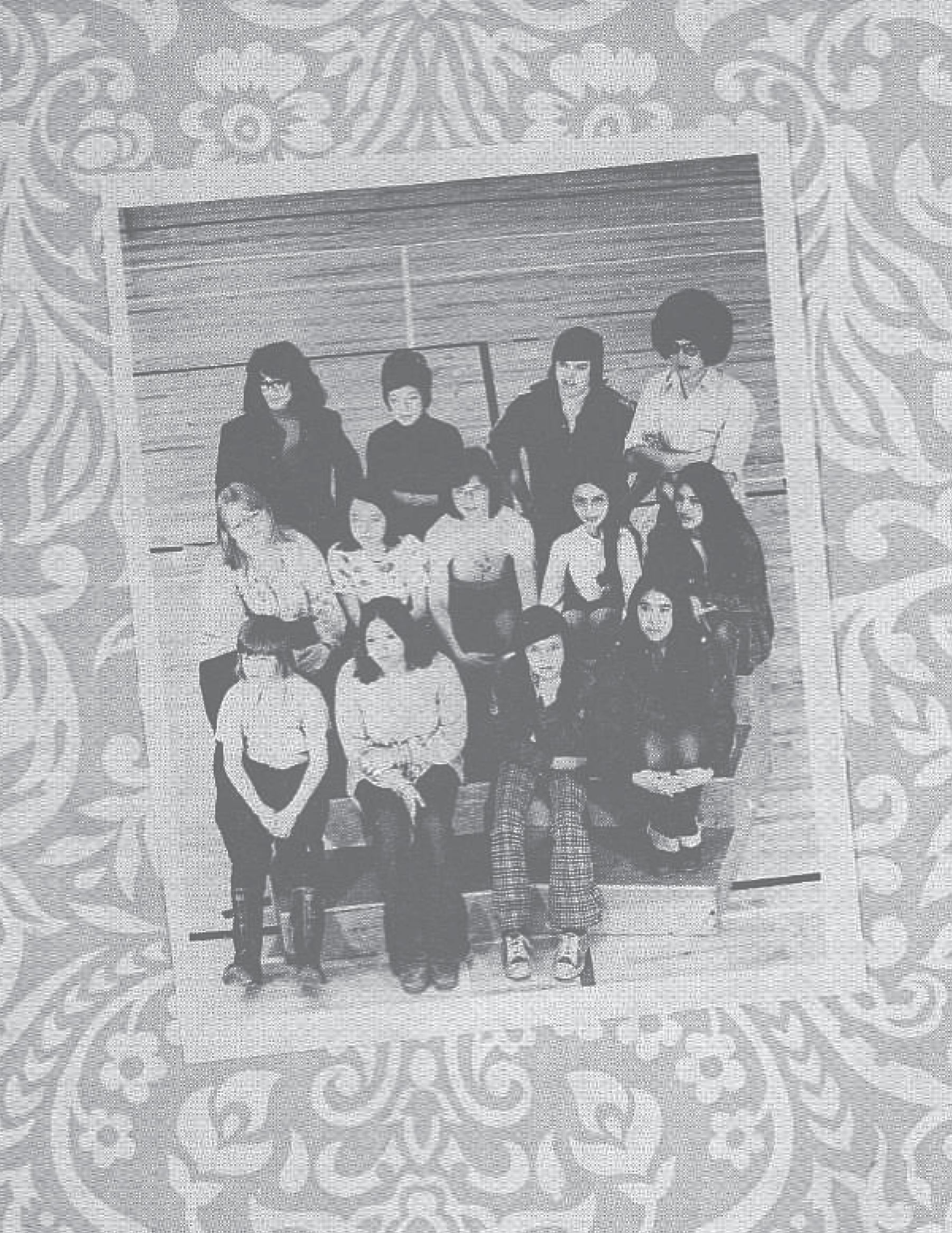

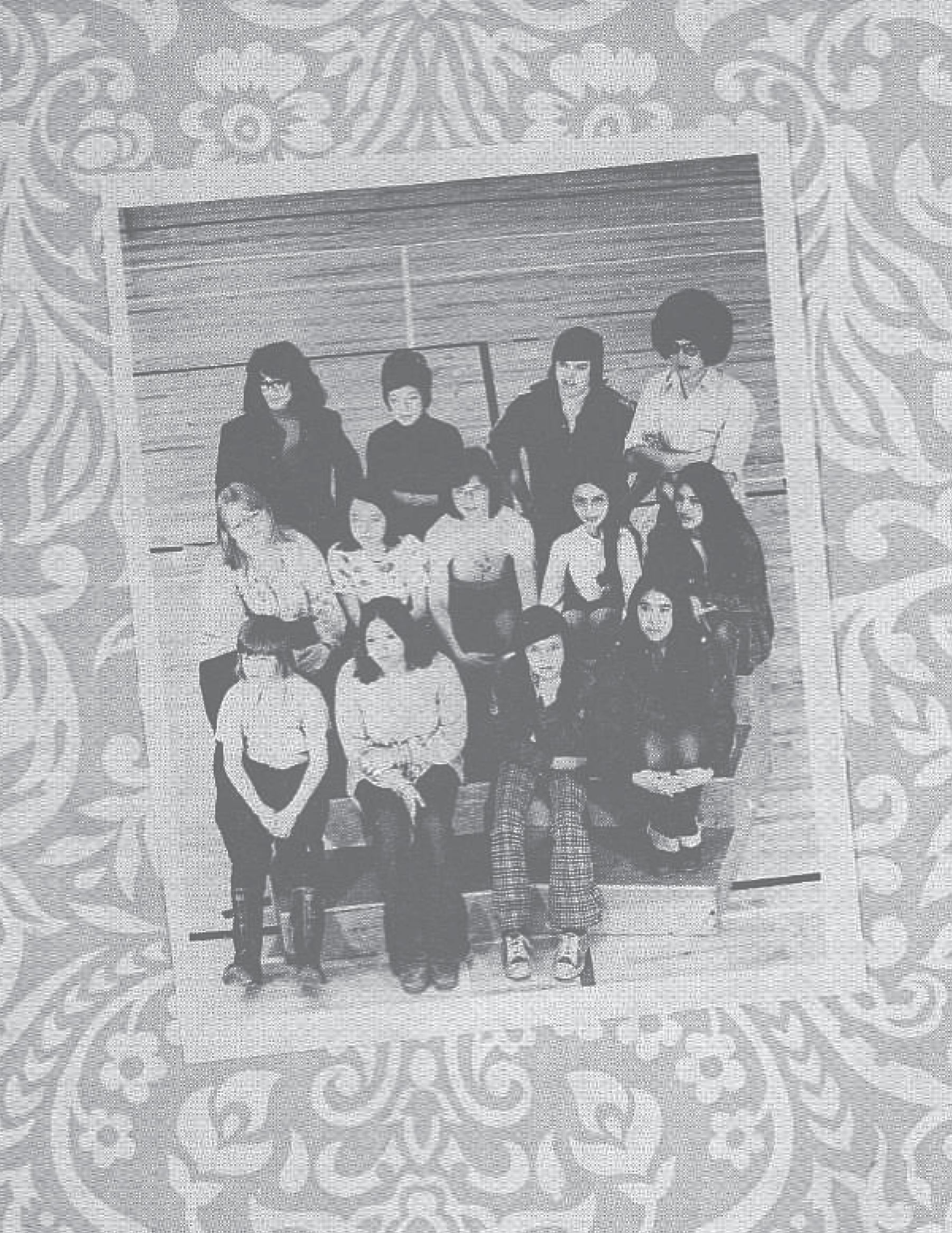

The graduates from aurora College exemplify this, celebrating the completion of programs ranging from Management studies and Certificates in Traditional Arts to Office Administration Management and Early Childhood Development. The Campus in Inuvik had 18 female graduates in 2008, marking an incredible example of the strength of women graduates and the importance of higher learning.

s ince 1996 the rate of female graduation has surpassed that of the male population. s heree McLeod, a graduate at s amuel h earne

s econdary s chool (shss) in Inuvik, is certainly part of that trend. awarded h ighest academic female and The Cliff k ing award, given to the graduate who made the most effort towards the graduation, s heree has a lot to be proud of. When asked whether or not she understood herself as the future of the n WT, she responded that though she is going south for schooling she will return to Inuvik in the future and hopes that more people will learn the languages and traditions of the n orth. “I don’t want anybody to forget our culture,” she says. a nd though she has no plans to be in politics, she will promote this through her work in art and technology.

s amuel h earne graduate Lawrence s ittichinli says school is a learning process. h e wasn’t always a good student but with guidance and determination he changed his ways. h e could not be happier.

a nother shss graduate, C.J. h aogak whom s achs h arbour principle Linda h all champions as a role model for all his peers, agrees that school requires diligence, with exams being the hardest part. he said he will not miss high school, but is looking forward to future learning in Edmonton.

a s s heree points out, the challenges of school are not limited to hard work and exams; bullying and the common pressures of adolescence are ever present. s heree credited much of her success to the support of her family and her older sister.

Next Page: Some of the graduates from Sir Alexander Mackenzie School.

1.Matthew Skinner, Mrs Stringer

2.Brandi Larocque, Mr. Deering

3.Jozef Semmler, Mr. Deering

4.John Gruben, Mr. Murphy

5.Keaton Cockney, Mrs. Stringer

6. Trevor Thrasher, Mr. Murphy

7. Trent Gordon, Mr. Murphy

8. Robyn Rinas, Mrs. Stringer

TUSAAYAKSAT SUMMER 2008 12

the wake of the formal Canadian apology to aboriginals for a history of residential schooling, many speakers, graduates, and attendees alike see a mission of education as central to the healing owed to the future generation. Graduates were encouraged to stay focused on objectives and goals and understand that learning is for life.

Photo by Zoe Ho

Special Feature Nuitaniqsaq Quliaq

Photos by Zoe Ho

What’s next for our grads?

Whatever he does, r ichard Tardiff Jr., a Moose kerr graduate, emphasized the importance of land preservation: “I want to do something for the land to save it. We have a rich culture here from hunting caribou to trapping and life on the land.”

a lso from Moose kerr, s heera a rey will work for a year and go to school in Edmonton for Business Management. s am McLeod will study to become a mechanic.

After a summer of fishing and potential work at the Hamlet, Jonathan kudlak of u lukhaktok plans to go to college, with the hopes of working in the mines or on an oil rig.

Photos by Chris Yapp

from shss , s heree McLeod and C.J. h aogak plan to continue their studies, and Lawrence s ittichinli, though currently working for h orizon n orth, has big plans to travel the world, starting with a ntarctica, (going to somewhere cold for a change!), Mexico and beyond! h e also intends to upgrade and continue his education at aurora College.

Whatever they do, we wish all our graduates congratulations and the best of luck in their bright futures!

TUSAAYAKSAT SUMMER 2008 14

Nuitaniqsaq Quliaq Special Feature

Hats off to the grads: Samuel Hearne School graduates tossed their hats high into the air.

15

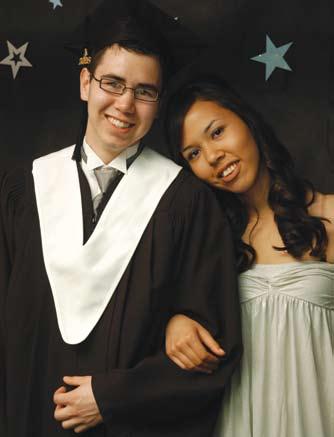

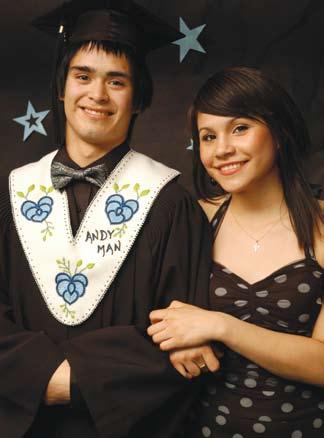

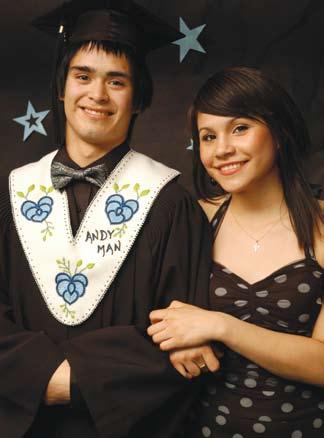

Andy Robertson and Shayna Allen

Doug Price and Haleigh Pielak

C.J. Haogak

Allan Roberts and Peter Lennie

Esther McLeodand her granddaughter, Sheree.

Photos by Maia Lepage

Our Time at SAMS

Elementary School Memories from Graduates

neta a llen and a ngel k alinek are both excited. n eta is searching for the perfect pair of shoes (flats, because she is twelve and does not care about heels) to go with her sky blue dress, and a ngel is looking forward to wearing her beaded slippers. Tuesday June 24th is their graduation day from elementary school in Inuvik.

n eta, who was so advanced in her kindergarten class that she was the only child to read chapter books, said there were times when getting through elementary school was hard.

“ s cience class is hard,” she said, but she managed to pass all her grades. In fact, she scored the third highest mark in her class this year. “I love Maths. It’s my favourite subject,” said n eta. a ngel agrees that it is the best subject.

“I was at s ir a lexander Mackenzie s chool (sa M s) for 7 years. My favourite class in art. The most fun thing I did was to join the Delta Demons wrestling club.”

a ngel likes being part of k arry’s club. “We go to preschool to help the kids there with reading, and we go swimming, play at the park together, and go sledding in the winter.”

Both girls said they enjoyed school, especially all the traveling and cultural activities.

They went with the school to r achel reindeer Camp, to see the pingos in Tuktoyaktuk, to sa M s n unami Camp, and n eta even went as far as yellowknife and Calgary with the Delta Demons.

The girls are thankful for the help they had with their final exams. “o n my aaTs (a lberta achievement Test), my mum and my teacher Mrs. stringer helped me,” said neta.

"I’m very excited about high school,” said n eta, “because you can experience harder things.” a ngel is looking forward to woodshop in high school. s he likes making art, because she gets to work with her hands.

n eta is looking as far ahead as university. “I want to go to the u niversity of Calgary,” she said. s he had a tour of the university when she went there for a Wrestling tournament. “They have all kinds of things there – wrestling, dancing, nannies (students babysitting for pocket money), and gymnastics!”

In the meantime, the a boriginal Day weekend is all about anticipating their graduation. “It’s going to be a beautiful moment, graduation,” said neta. “There’s a song called Friends Forever that we get to sing when we graduate.”

“Rachel Reindeer camp was so much fun. We got to go sledding and don’t forget, the fishing!” said Angel. “And I got my first fish ever,” added Neta.

Angel Kalinek and her grandmother Renie on graduation day.

Neta Allen just graduated from elementary school, but is already thinking ahead to university.

Helen Kalvak SchoolUlukhaktok

The one who inspires: Jonathan Kudlak, Ulukhatok’s sole graduate, advises his peers and his twelve-year-old sister to “keep getting up in the morning, go to school everyday, and work hard.”

Special Feature Nuitaniqsaq Quliaq

Photos on this page by Chelsea Olifie (She also took the hockey photos of the McPherson Team and the Tuktoyaktuk team in the last issue!)

Photo courtesy of Emily Kudlak

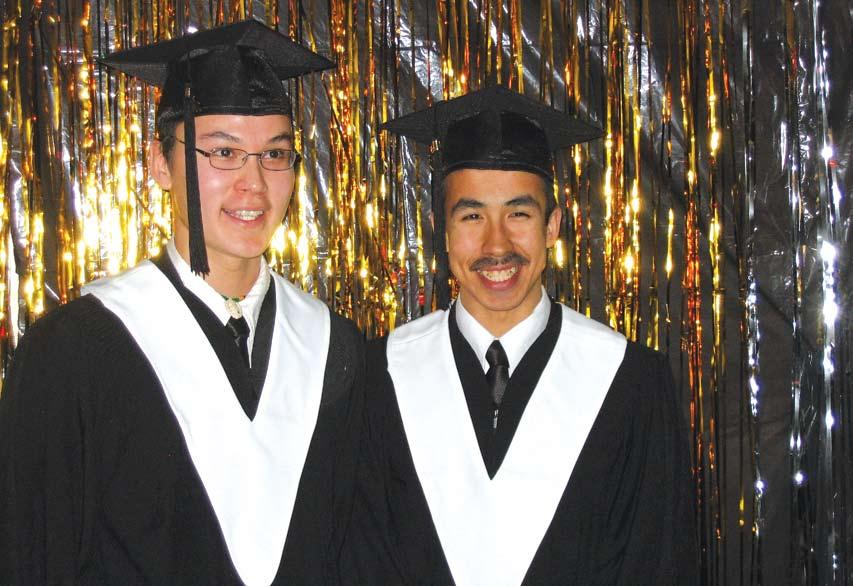

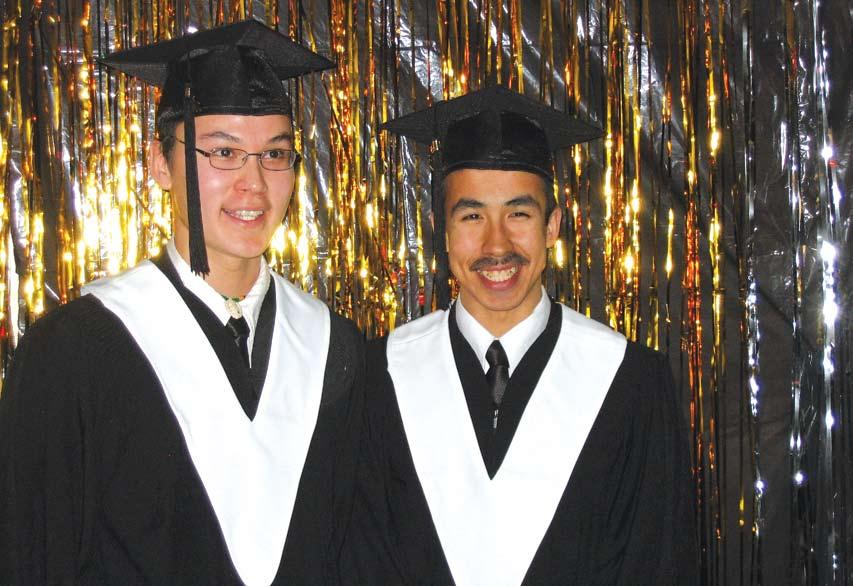

Aurora College - Inuvik Campus

Aurora College Learning Center

TUSAAYAKSAT SUMMER 2008 18

Graduation Season 2008

Special Feature Nuitaniqsaq Quliaq

Top (L-R): Mary Ohkeena, Vera Ovayak, Lorianna Elanik, Sandra Gordon, Marjorie Baetz, Amanda Lennie, Esther Ipana, Sara Gardlund, Katherine Lennie, Russell Andre. Bottom (L-R): Devin Brodhagen, Jennifer Thrasher, Janice Elaink, Patrick Joe, Georgina Ohokak, Jodi Snowshoe.

On their way to good things: graduates from Aurora College.

Learning Center Graduates throw a retro party

Photos by Chris Yapp

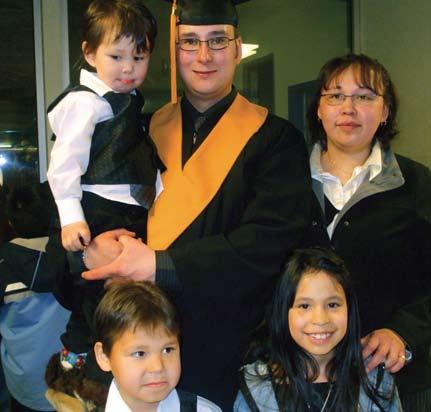

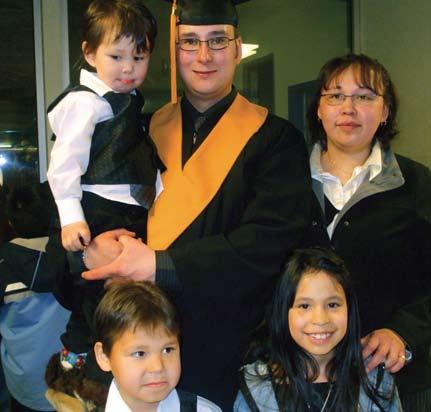

An Inuvialuit Leader in the Making: Richard Payne

Richard Payne got to know the whole town of Fort Smith by the time he completed his Management Studies Diploma at the Aurora College Thebacha Campus. “I drove a cab all over town after school during the second year of my studies. It was better than struggling financially from week to week,” he said.

During his teenage years, Richard had gone to a private boarding school in Yellowknife. In Grade 8, he had the chance to visit Tuktoyaktuk and decided he wanted to “run away to Tuk.” Attempts by his father to get him back to the all-boys private school were rejected by Richard. It was eight years after Richard had left his high school studies before he decided it was worthwhile to give school another try. The deciding factor was family.

Richard had begun a lovely family with his wife Roseanne and their three children, Delanie Bucket, Cole James, and Ashton Jett. He wanted to give his children a better life. He was then living and working seasonally for EGT Transport and NTCL in Tuktoyaktuk.

“I decided to go back to school after my son Ashton was born,” he said, “so that I could eventually find a full-time job that pays me enough to support my family.”

“At first I wasn’t sure if I would be able to get back into the whole school routine again, but I am really glad and proud that I did and graduated.” Even though it was challenging to balance getting his diploma and driving a cab part-time, Richard was determined to stay on track. He cites the support of his family as crucial to his success. Right after graduating, he accepted an office manager position with NTCL in Inuvik. He is now practicing his newly learned accounting and management skills.

“I chose Management Studies because I can see myself in a leadership role in the future; hopefully with an Inuvialuit company or with the Inuvialuit Regional Corporation,” he added.

“I have been traveling all over but have always returned home to Tuktoyaktuk. I am proud to be Inuvialuit and glad to be part of such a successful and organized group of people. I feel that the people of IRC and IDC and all the other parts that represent the Inuvialuit people have done great, and hope to one day join them in leading the Inuvialuit people.

Graduation Season 2008

Richard Payne and his family.

Verna Arey and Annie Buckle are happy adult learners!

Trades Access Program graduates.

Patrick Joe making a graduation speech.

Photo courtesy of R. Payne

Angik School - Paulatuk Angik School - Paulatuk

Kindergarten Graduates

Cheyenne Haogak

Meagan Kolola

Rosanne Lennie

Caleb (Ry Ry) Lucas

Grade 9 Leaving

Tyson Esau-Raddi

Steven Lucas

Selene (Tessa) Lucas

Inualthuyak School- Sachs Harbour

Proud smiles: Angik School graduates Aaron and Stacy beam for the camera.

Photo courtesy of Jessica Schmidt

Photos courtesy of Linda Hall

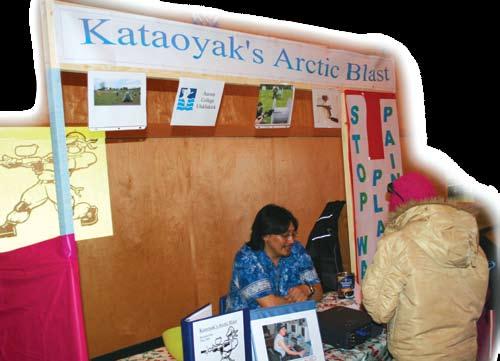

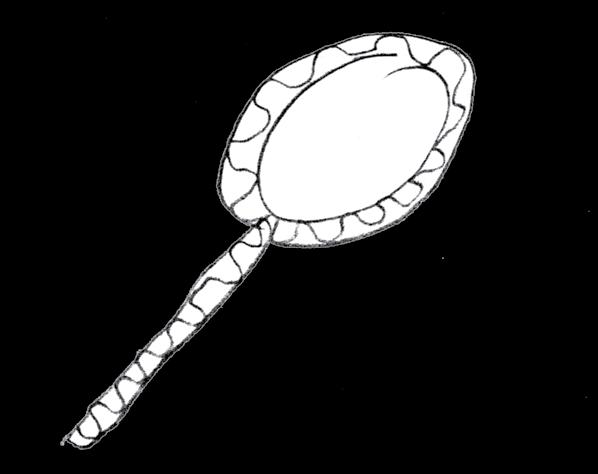

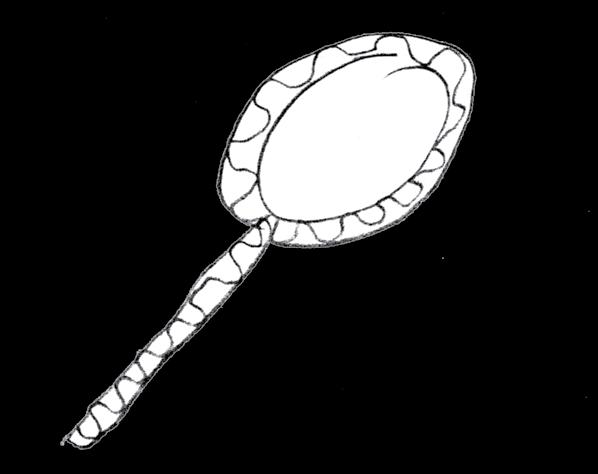

BIZ WHIZZES from Ulukhaktok

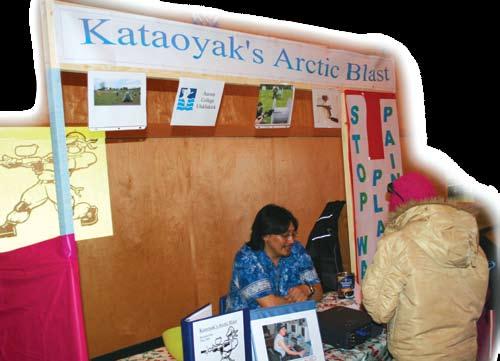

fred k ataoyak had so much fun playing paintball, a game where people wield guns loaded with balls of paint instead of bullets, that he was inspired to start his own paintball facility in Ulukhaktok. “I played for the first time when I was in Edmonton. I didn’t want to stop but it was too expensive to play any longer,” he said. To make his dream come true, fred enrolled and has just graduated from the aurora College s mall Business Development program at the u lukhaktok Learning Center. There he met other like-minded local entrepreneurs who had passions they wanted to turn into businesses.

Lori o vilok wanted to start a business with her painting skills, roberta Memogana had a rctic crafts to market, a nita wanted to show tourists how beautiful the north was, and Gillbert Olifie wanted to showcase her a rctic arts. o n May 13th, they all graduated from the small business development program, launching their businesses with trade booths at the h elen k alvak s chool gym. Visitors who came were treated to multimedia displays and celebratory drum dancing.

When asked which of his classmates’ idea he was most impressed with, fred said, “I think everybody’s ideas are good, all it takes now is for us to take the steps to register the businesses and to start running them. Before I started this course I didn’t know much about accounting and business laws. I have that knowledge now. I am happy I finally got to learn how to start up my own business.”

fred named his business ‘a rctic Blast.’ h e has some strategies for making it take off with a blast. “I am going to make getting into the game a bit cheaper, and if people want to play more, they’ll have to pay for the paintballs,” he said. “And it’s definitely a summer thing. If you played in the winter, the paintballs will be frozen, you will get pretty bruised,” he laughs. Good luck to all five new entrepreneurs from Ulukhaktok!

21

Graduates from the Aurora College Small Business Development Program at the Ulukhaktok Learning Center:

Roberta Memogana , Gillbert Olifie, Lori Ovilok, Anita Oliktoak, Diane Williams (instructor), back row Mel Pretty (instructor) and Fred Kataoyak.

Fred and his ‘Arctic Blast’ trade booth.

TUSAAYAKSAT SUMMER 2008 Special Feature Nuitaniqsaq Quliaq

Lori Ovilok and her Ovilok’s Painting Contracts display.

Photos courtesy of Diane Williams

Workplace Readiness Graduates

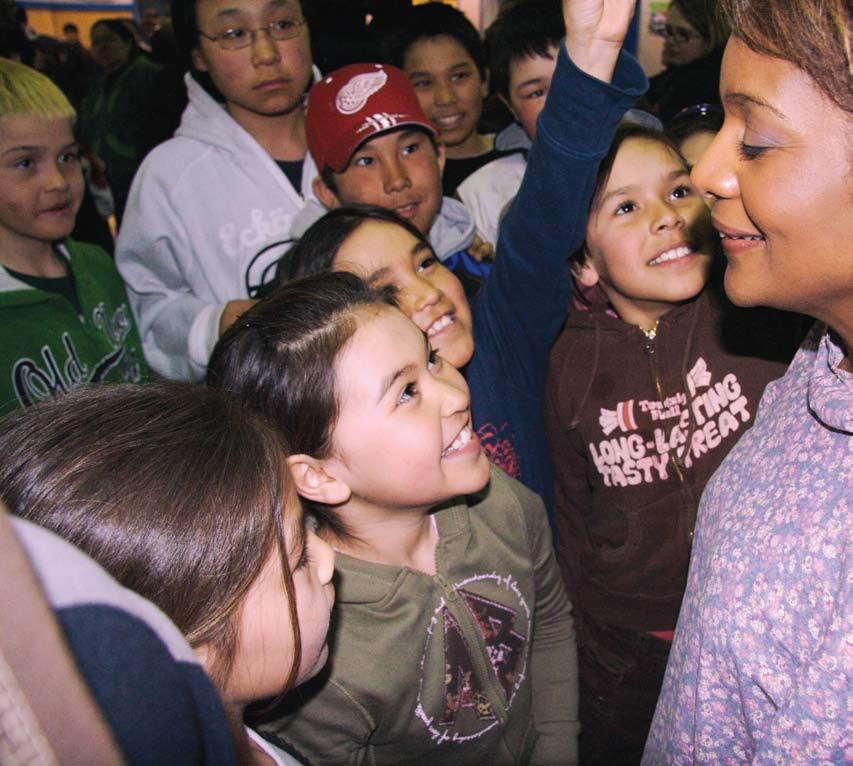

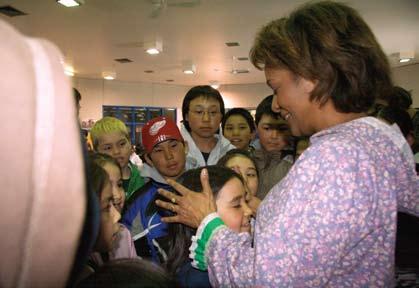

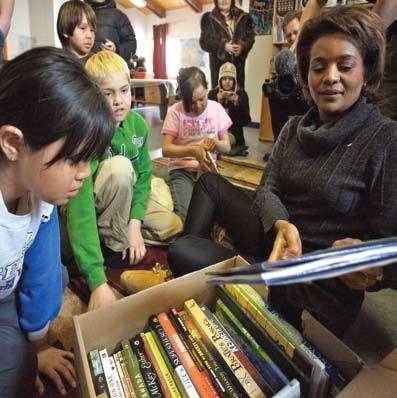

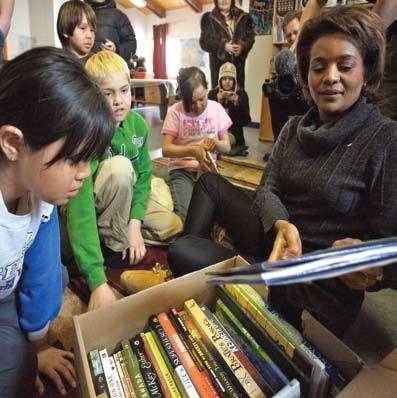

TheI rC Workplace readiness program celebrated its first six graduates this Spring, with a rousing ceremony at the Ingamo h all friendship Center. n ellie Cournoyea, Chair of the Inuvialuit regional Corporation expressed her pride in the graduates and her support for their program, which is designed to help unemployed young adults bridge their way into the work world. “Each and every one of you are very important to me and I am proud of you for overcoming difficulties and challenges to be here today. s ome people might say that this program only has a half success rate of graduates, but I will say that every one of you count and every graduate is a success.” a ll the graduates had excelled at their work placements and some have had their contracts extended beyond their practicum.

“I feel more confident after this program,” said Rena Gordon, a young mother who at first found it hard to juggle her training and family duties. She admitted the thought of quitting passed her mind, but the program became more interesting as it progressed.

“I’ve learnt a lot and my job at Aurora College is my first job. I guess I am ready for the work field now. I would like to thank everyone at the college for their warm welcome to me when I arrived, and for their patience.” rena hopes to work towards starting her own business one day.

22

TUSAAYAKSAT SUMMER 2008 Special Feature Nuitaniqsaq Quliaq

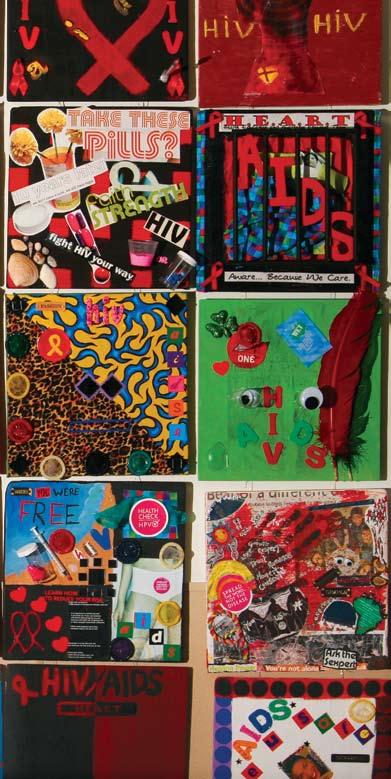

The graduates completed their work placements mainly with companies in Inuvik. s arah k aglik worked at n orthwind Industries, Debbie a ngasuk at Inuvik Gas/ Matco, a manda Wolki at the Joint s ecretariat, russell s mith at n ew n orth n etworks, rena Gordon at aurora College and priscilla Taylor at Canadian n orth in yellowknife. Gloria o mingmak was able to begin working in her home community, u lukhaktok, after participating in this program. The participants’ familes, children and friends applauded their success and hard work as each received their joint-certificate from the Inuvialuit Regional Corporation and Bow Valley College.

russel s mith said, “This course has taught me how to focus better.” h is interest in photography has been nurtured in this program, and working at n ew n orth n etworks had allowed him to learn more about technology. russel is always fascinated by aircrafts and had made one of his program assignments into an opportunity to take photos of pilots.

s arah k aglik had prepared a valedictorian speech but unfortunately had to miss the graduation when her child was sick. We include here an extract of what she wanted to say:

I now have a job that you - such very kind people - helped me to achieve. I thank each and every one of you for joining us tonight, and especially for your help in finding such great, kind instructors and coordinators who love to help others. I’d like to mention some memorable moments that we all have shared together but throughout the program there has been many... Did anyone bring their digital story?

n obody? Well, that was a memorable month, the month when we learnt to use computers, sound and visuals to tell stories. We also learnt many other skills, preparing mentally and ability wise for work in the real world. I had some pretty hard times attending this program, due to me being a single working mom, but with the help of family and the instructors here, I managed to keep going strong, and I was determined to find what I was looking for in life: A full time job, and the many friends that I’ve made and will make.

IRC Provides Largest Distribution Payments To Date

The lobby of the Inuvialuit Corporate Centre was bustling as of 8:30am on May 7th, 2008. The Inuvik Community Corporation (ICC) was distributing beneficiary cheques for beneficiaries aged eighteen and over, and many had come by to pick up their cheques before going to work. The Inuvialuit Corporate Group reported a net income of $35.2 million in 2007 and shared its success with beneficiaries with distribution payments of $1,001.09 each. A total of 3,812 beneficiaries received payments.

“It’s going well,” said Gayle Gruben, office manager of the Inuvialuit Regional Corporation (IRC) as she checked off the name of a beneficiary. k atherine Lennie, who is a student at aurora College, welcomed the extra income. “My cheque and my boyfriend’s cheque are going right on the Visa. We are also going to Calgary this friday,” she said. “It helps us out.”

Elder Edward Roland believes the payments will serve practical purposes, “This will help a lot of people who are going out on the land. It will provide food to young kids, it makes everybody happy because some people don’t work and live on social assistance. This payment will come in handy somewhere down the line as long as it’s spent wisely.”

I rC subsidiaries – Inuvialuit Development Corporation, Inuvialuit Investment Corporation, Inuvialuit Land Corporation and Inuvialuit petroleum Corporation –contribute to the distribution. The I rC Distribution Policy is based on a formula that ensures sufficient reinvestment of profits to guarantee the preservation and growth of the landclaim capital for future generations of Inuvialuit. These reinvestments fund programs aimed at enhancing education, as well as the social and cultural development of the Inuvialuit.

n ellie J. Cournoyea, Chair and CEo of I rC said, “The distribution to our Inuvialuit beneficiaries is the largest to date. We are pleased to share our financial success with the beneficiaries, and look forward to its continuation in the years ahead.”

Beneficiary Dez Loreen reflected, “We are well represented by our corporation. It helps us be better off than most aboriginal groups.”

Photos page left: (L-R) Sarah Kaglik worked at Northwind Industries, Debbie Angasuk at Inuvik Gas/ Matco, Amanda Wolki at the Joint Secretariat, Russell Smith at New North Networks, Rena Gordon at Aurora College and Priscilla Taylor at Canadian North in Yellowknife.

In The News Tusaayaksani

This page: Inuvialuit leader Nellie Cournoyea and Russell Smith show us Russell's hard-earned certificate.

Logan Bullock signs in with Mary Inuktalik of ICC to get his cheque.

CIRCUMPolAR INUIT

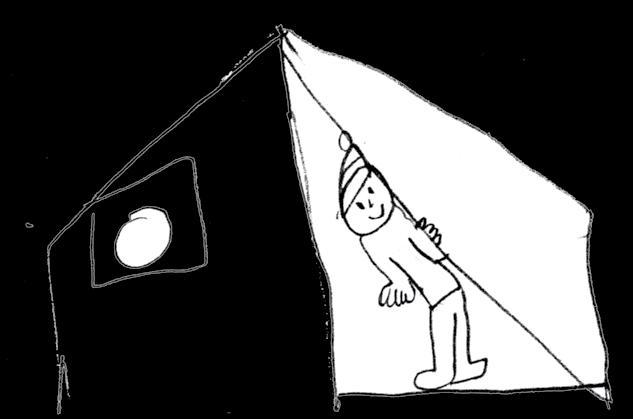

Climate Change Policy Workshop abroad the Amundsen

Theicebreaker Amundsen is currently sitting in a flaw lead in the a rctic ocean,near the Inuvialuit communities of s achs h arbour and p aulatuk. The scientists conducting oceanographic studies on the research vessel are convinced of the urgency to mitigate the effects of climate change, and are making full use of their time on this International polar year research initiative.

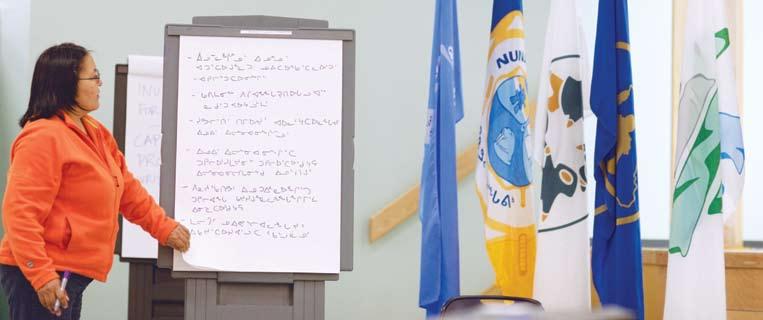

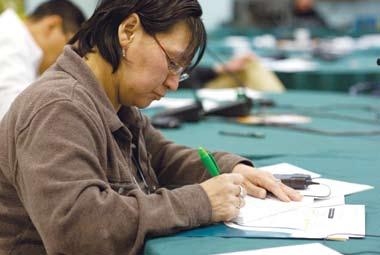

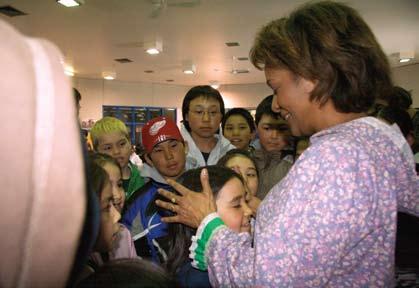

This a pril, the Inuit Circumpolar Conference (ICC) held a Circumpolar Inuit Climate Change policy Workshop aboard the a mundsen. a rctic leaders from the circumpolar region had the chance to meet the scientists and to observe and ask questions about how the research applies to the needs of their people. The leaders came away impressed by the scope of the research, but national Inuit leader Mary s imon did note that it was hard to see immediately the relevance of scientific research to traditional Inuit knowledge and needs.

The delegates from each ICC region reported on the effects of climate change in their area, as well as on the adaptation of their people. a lthough their stories are told in different languages, the thread of commonality amongst the climate change symptoms observed from a laska, Chutkotka, Canada and Greenland was astonishing. We could see the connection between the suffering reindeer herders of Chutkotka, and the ones in the Inuvialuit s ettlement region. n ew species of insects are being observed, and shorelines are eroding at accelerating rates. Inuit are the people on earth most affected by climate change, experiencing a myriad of symptoms brought on by global warming that is affecting adversely the animals they harvest and the land and sea ice they rely on.

TUSAAYAKSAT SUMMER 2008 24

The leaders concluded that it is imperative to continue their cooperation and to escalate their efforts, to make sure the indigenous perspective is placed on the table at global decision–making levels. At the political level, the leaders also said it was important to take climate change into account when making infrastructure and socioeconomic decisions.

Joey Carpenter, Margaret Kanayok, and Ruben Ruben are on the Inuit Navigating A Changing Climate in Canada Panel.

ICC President Duane Smith stressed the urgency of mitigating climate change impacts.

Stephanie Meakin (ICC support staff) and NWT premier Floyd Roland learn from a scientist about living organisms on the bed of the

The problem of climate change is thus not isolated, and the pressure for change to improve the situation for these Inuit who are connected becomes exceedingly obvious given the evidence they have observed. o ne of the components of the Circumpolar flaw Lead system study (C f L) will focus on “Two ways of knowing.” Led by Team 10 of the C f L study, and a Traditional k nowledge steering committee made up of Inuit community members, this component hopes to integrate Inuit traditional knowledge with the findings by the other teams, with the vision of achieving research objectives that respond to community needs.

In The News Tusaayaksani

Amundsen, the ice-breaker research vessel.

Tatayna Achirgina (left), ICC member from Chutkotka, reports on impacts to reindeer herders and shorelines.

arctic ocean.

Ice cores are taken from the sea ice, shaved into millimeter-thin slices and analyzed. >>

EN v IR o NMENTA l IST

This summer, James Kuptana will be coming to your communities to conduct research for Team 10 of the Circumpolar Flaw Lead System Study. The Trent University student brought a youth perspective on climate change to the Circumpolar Inuit Climate Change Policy Workshop, and chats with us about his role in the project.

yo UTH

James on the deck of the Amundsen.

Tell us about your chosen field.

James: I am currently in the field of Indigenous Environmental Studies; it is an arts degree, which focuses on human ecology but there is also a science component to the program.

What is your role on this trip?

James: I will be meeting with other key stakeholders involved in the Circumpolar Flaw Lead System Study. My obligation, to my understanding, is to bring a youth perspective to Team 10 and also to gather traditional Inuvialuit Knowledge about the flaw lead.

What was it like to communicate with elders on Team 10?

James: It was just like talking with any other person. They understand my message and where I am coming from. Elders have so much knowledge all you have to do is be around and active in your life to learn from them. You learn by watching and doing.

What did you hope to achieve with your presentation at the Climate Change Policy Workshop?

James: I just wanted to bring a young person’s perspective to the table. My main point was regarding education; uneducated, unaware people need to know what is happening and how the world is changing. I used the past winter as an example; much of Canada received record snowfalls and many naive people said: so much for climate change...Climate change is much more than just global warming; it can result in changing precipitation patterns, altering sea levels, re-directing animal migrations, and much more.

Did being on the Amundsen add to, or change your perception of climate change in the north?

James: Being on the ship was an eye–opener, to see what scientists are doing to understand the science behind climate change. The research being conducted on the Amundsen has the potential to change our understanding of how the Earth's systems work and how they are changing. I think this trip to the Amundsen and Inuvik was beneficial because it gave me the chance to see what Inuit are doing about climate change and also what scientists are doing.

How do you feel about the North?

James: I LOVE THE NORTH. It is my second home, most of my extended family is in the North. I am by no means a ‘northerner’ as I have been born and raised in Ottawa but the time I have spent on Banks Island has

always reminded me of where I come from and helps to create where I am going. Being out on the land is very uplifting, physically, mentally, and spiritually; you get to be with family. I think that is really important, especially right now with all the changes taking place in the North. You need to know how to survive on the land and it is your family who can teach you these skills. Being Inuvialuk means I have the blood memory; I just need to find the ways and people to help me release it.

How often have you visited Sachs Harbour? What is your impression?

James: I have gone to Ikahuk nearly every summer since I was 2 years old, just a baby. My mom tells me I caught my first fish through the ice at 2 years old at Capron Lake during a snowstorm. My impression of Ikahuk is one of inspiration; I am inspired by the people and the things they do whenever I travel there. The stories I have been told and the knowledge I have gained in Ikahuk is indescribable.

In your opinion, how can youth in the North strive for opportunity or change?

James: For change to happen you must allocate as much broad–based support from as many parties as possible. This means being active in community-regional, and national–level politics and negotiation; Inuit have always been active in this area of politics and will have to continue to be if we want to strive for opportunity for our people.

Can you tell us about your future involvement with this IPY project?

James: Certainly, I have recently been selected to partake in the Students on Board program this summer. I will be collecting traditional Inuvialuit knowledge about the flaw lead and will join Inuit and researchers from other circumpolar regions and the international community. We will come together on the ship in earlymid July to discuss what we have learned so far and share our knowledge bases with one another.

Next fall there will be an opportunity to do some detailed mapping regarding traditional knowledge of the flaw lead and also an opportunity to lead some semidirected interviews with elders.

My main goal is to help to create this “Third Way of Knowing” to reach out and educate those who are still unaware of climate change and the implications it has for humans as a species. This project I feel is aimed at gathering broad–based support from the international community, many other circumpolar regions are participating in this project and it is a sign that the world is starting to come to terms with what is really happening to our environment. It is good to see a commitment between Canada and other nations to gather a comprehensive scientific and Inuk–science base which can be combined to instill change in policy and law regarding climate change on an international level.

TUSAAYAKSAT SUMMER 2008 27

Youth Speak Up Nutaqat Uqaqtut

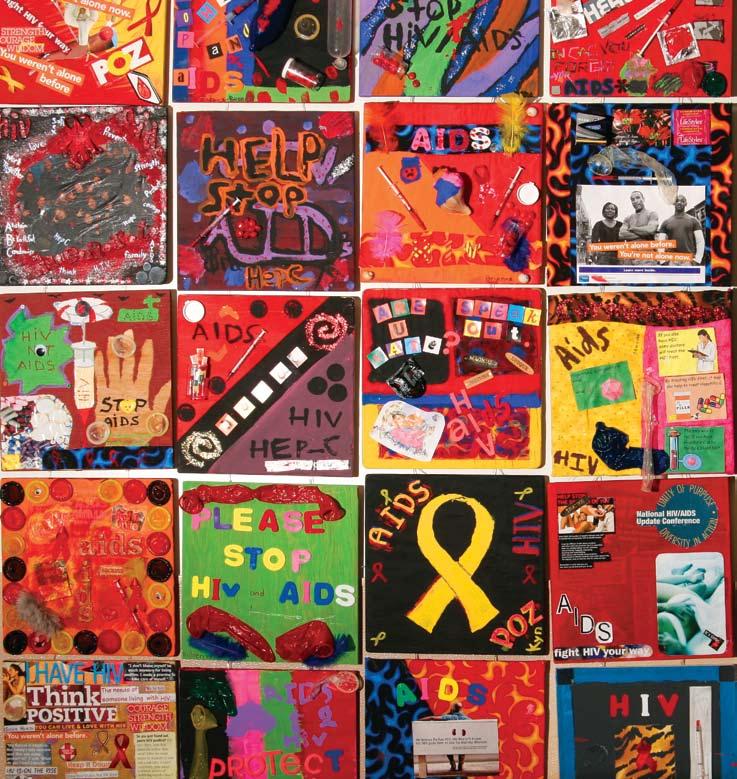

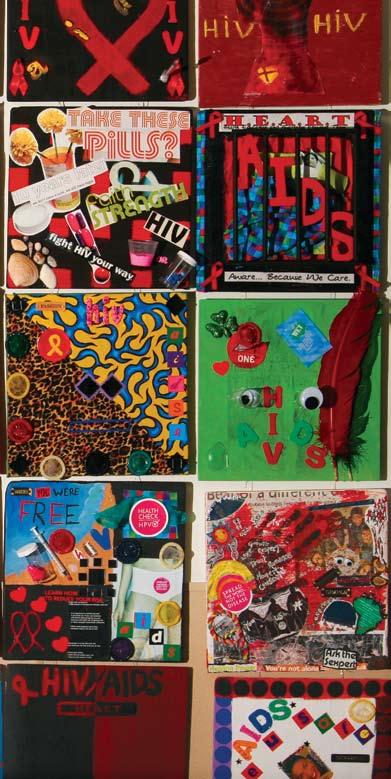

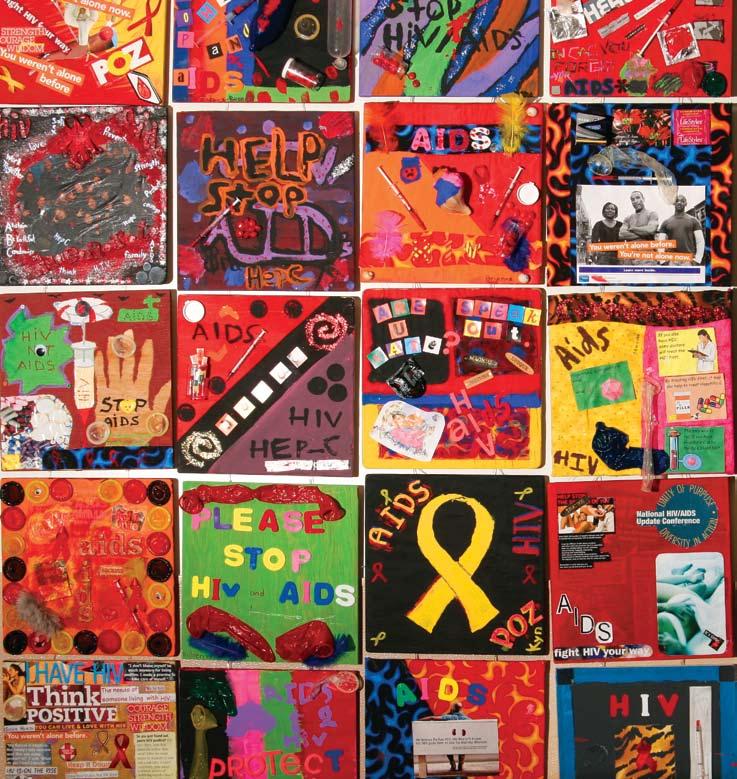

ware because we care

The h IV/a IDs awareness program delivered in p aulatuk was the first of its kind in the North. The idea was sparked by Sam kerr, a nurse, as well as Jessica s chmidt and stephanie k inney, teachers at a ngik s chool in p aulatuk. The trio arranged funding and invited Lance hogue, a long-time h IV/a IDs specialist, to carry out a a two-phase health education program at the a ngik s chool.

so warns a rap song created by Lance hogue, s am kerr, and the students of a ngik s chool during an h IV/a IDs awareness program in March. The words convey the wisdom of being prepared for Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), a disease that kills more than two million people annually.

It is a worthwhile cause, and the timing could not be better. Despite global advances in health care, evidence has suggested that the disease shows no sign of slowing down among the aboriginal people of Canada. In the n orthwest Territories there are around 20 known cases of h IV, intravenous drug use (injecting with needles) the most common form of

TUSAAYAKSAT SUMMER 2008 28

a“Listen up people –It ain’t if, it’s when, What will you do then?”

virus transmission. Due to diminished media attention and improvements in medication, many assume that h IV is no longer a serious threat. This is a false assumption. h IV is still a virus without a cure.

Modern treatment can save your life if started early. h IV attacks the human immune system, gradually stripping the body of its ability to defend itself. o nce the immune system has undergone serious degradation, HIV can reach its final stage, Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS). From there on, cancers and infections may quickly populate the body, and render it defenceless. n ot everybody who has h IV will have a IDs . With the help of treatment, many people can continue having normal lives. It is important to get tested so medication can be administered as soon as possible.

for Lance hogue, a medical consultant living in Maryland usa , the program in Paulatuk was a challenge. It was his first time this far in the north, and there were a lot of unknown factors that cropped up. The program was being tried in a totally new environment. In phase one, the basics of h IV/a IDs and hepatitis C were taught to everybody in the school by the teachers. In phase two, Lance took over.

The bulk of the program was delivered through a student group called the health Education awareness response Team, h E arT, made up pf mostly older students at a ngik s chool. The h E arT team and Lance produced a colorful mural following the Global Peace Tiles initiative. They also filmed and edited an h IV awareness documentary. The documentary, featuring students as actors, was later shown to the community.

Lance Hogue’s first and foremost message to the students was the a BC rule: a bstinence, Be f aithful or Condomize. h IV is a sexually transmitted disease, and the surest way to get it is to practice sex without using a condom and with a partner whose health is unknown. a nother sure way to get it is through a used drug needle. There are several myths and false beliefs about h IV and how it spreads, which were unveiled during the program. you can’t get it from a toilet seat. you can’t get it from breathing or caughing.

Edward ruben, an elder in p aulatuk, responded after watching the youths’ video on h IV, saying that a IDs is a challenge to tackle as a people, just like his ancestors did with any other adversity. he said, “ young people need to be working as a team, like it used to be. We had to face our fears, big animals. This is another one of those things.”

29

It is not easy to discuss the use of condoms in a community like Paulatuk. There are a lot of taboos around sex. But the video, as well as the peace tiles mural, shows that the kids were actually mature, and ready to step outside of their comfort zone in order save their lives – and the lives of the people they love.

PHOTO: The HEART team and Lance put together this mural to express how they felt about the impact of AIDS.

In The News Tusaayaksani

Photo and words by Markus Siivola

From Bushcamp to Corporations: Aborginal Empowerment in Inuvik over 50 years

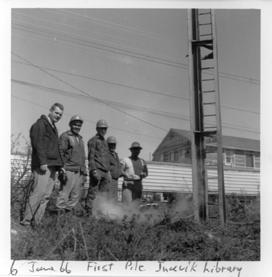

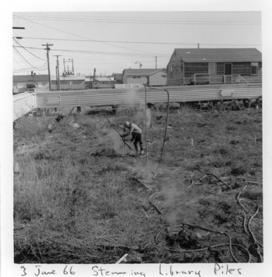

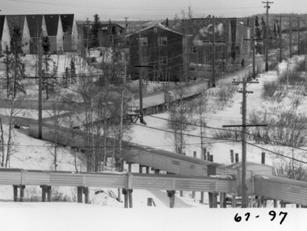

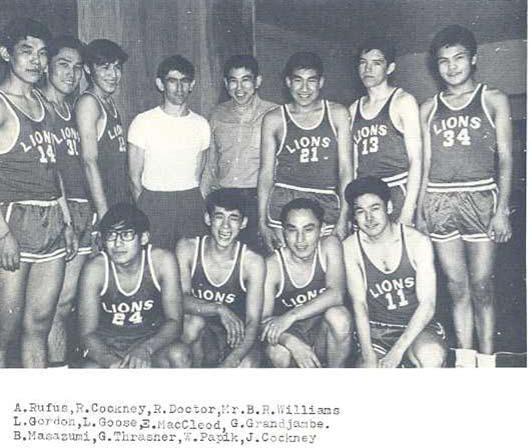

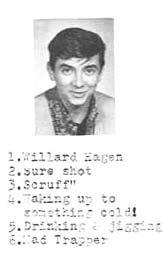

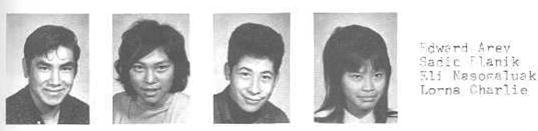

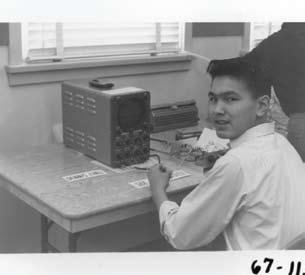

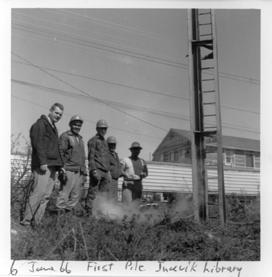

Inuvik’s 50th Homecoming Anniversary Special Feature A flavour of the day can be felt through this composite of yearbook pages from Inuvik’s schools in the sixties. Yearbook images courtesy of SAMS & SHSS

Building

Tommy Thrasher, Inuvialuit elder, took me on a winter’s foot tour around Inuvik. h is breath turned white as he pointed out some of the buildings he helped put up in this one-traffic-light town. “That’s the a nglican Church, I put up the steeple,” he said, “here’s sa M s chool, I helped build that too, and the Igloo Church, and look, there’s the post office. The third year I was here, this town was only as big as the post office,” he laughed.

The aboriginal construction workers would also set up tents along the river; as their population grew, the area became known as ‘ h appy Valley’ or ‘Tent Town.’

“We had to cut the bush to create trails, from Twin Lakes to the hospital,” said Colin. The area was overgrown with wild willow. “We made trails sixty feet wide, we cut it all the way to the airport. We didn’t have any powered chainsaws. n othing. We just used axes. I sharpened my axes all the time,” he laughed.

“Back then they thought pilings would last forever, but now with global warming…oh well, some of the buildings are gone now, I worked on these buildings and I’m still here.” Tommy has a mischievous smile, and I could see the pride that he felt to have been part of the construction of this town. “Back then it was called East Three, because it was at the third arm that branched off the Mackenzie r iver. I had just gotten married, we lived in a bush camp about 30 miles from Inuvik. I heard they were building a new town, and they were looking for construction trainees…”

That was 1954. Like many other aboriginal people who had moved to Inuvik for their first wage-earning jobs in the Mackenzie Delta, Tommy Thrasher’s life was forever changed. Before the new town was started, most a boriginal people still lived off the land and lived a nomadic but self-sufficient life. East Three was a “no man’s land.”

Colin too answered the same call to train as a carpenter. “When I was young, I trapped for my grandfather,” he said. “ h e raised me. I left home when I was eighteen, I never went back.” h is grandfather had always kept the money from selling the furs that Colin trapped, and Colin felt his first taste of independence by moving to East Three.

The first task at hand was to clear land to build on. There was nothing man-made in East Three, except for a few tents set up by the first construction team, made up of a small number of government officials and workers from the south.

When asked whether the building of Inuvik brought hope to the local people, Nellie Cournoyea said, “I don’t know if you would use the word 'hope'. It might have been the next big thing that was happening. It was the government’s proposition to move the town of Aklavik to another location because Aklavik was supposedly sinking. Well, we knew that a lot of people would never leave Aklavik and that it wasn’t necessarily sinking that badly.”

“Inuvik was planned within the Cold War era. The government was really looking for a place where they could build a very large airstrip. They were looking at different sites to find a place where they could find the gravel resources or foundation to put the airport.”

Employment became more important to aboriginal people as fur prices dropped. Colin a llen remembers continuing to return to the land with his family for all his holidays from work except one. h owever, while Colin made a good living as a carpenter in the beginning, he was told in 1972 that he needed certification as a journeyman to continue his work.

31

TUSAAYAKSAT SUMMER 2008

Colin Allen

Bertha Allen

ICRC Photo

Tommy Thrasher

“I had seven children and my wife,” he said, “I told them I am not going to Edmonton to take that journeymen training.” h e took up the job of janitor at the school then. This was a common experience for other aboriginal workers, who lost their jobs to qualified Southerners over time. n evertheless, Colin and Tommy are both nostalgic about the days of building Inuvik. “We built it, we were East Three,” said Tommy.

Settling

“ s ome of us came with our camping gear from muskrat camp,” said Bertha a llen, a Gwich’in elder who moved with her family to Inuvik around the same time as Colin. “ u sually we head over to a klavik, where there was a trading post, but this time, we moved all our gear to Inuvik. Employment went on after summer, then fall, and a lot of us never left.”

Bertha said the living conditions in the ‘tent town’ was challenging. About fifty families had put up tents, some as close as a foot apart. “We stayed in a small tent frame, about 10 by 12 feet for a couple of years, and then someone built a house and left their long tent frame. To me, that was like a real mansion, moving from a small tent to a longer tent frame!”

In fact, even as the town began to take shape over the first decade, with houses erected on both sides of the main Mackenzie Road, and the first school, hospital, office buildings and staff housing for government personnel were being built, living conditions for aboriginal people was not quite on par with that of southerners (personnel brought in to staff the rCM p, C p C, n C p C, Transport, n ational Defense, n ational h ealth and Welfare, Citizenship and Immigration departments.) a boriginal people eventually moved into 5-12s, the 512 square foot cabins that government employees long had access to, but still had to wait another few years before the utilidor would reach their homes.

The utilidor was a unique two-way system meant to pipe sewage, fresh water and heating to homes in Inuvik. The pipes are housed in metal containers raised above ground so as to prevent melting the permafrost underground.

Bertha a llen had been one of the founding voices behind the first housing co-op in Inuvik. It was made up of both aboriginal people and people of other backgrounds. They ordered building materials from Edmonton to build their own housing. “We all helped assemble each other’s houses,” she said, “the men said, Bertha’s going to have the first choice of the house and lot that she wants, because she made the loudest noise.” Bertha would also become a champion of aboriginal rights, and native women’s rights, heading such as the n ative Women’s a ssociation, and other organizations that empower a boriginal n ortherners.

n ellie Cournoyea, Chair and CEo of the Inuvialuit regional Corporation said, “ you had the Canadian forces as well as government, and mainly Indian affairs thinking, so most of the housing was built for the government people who came into town and lived on the bases, they would have to be looked after the way they were in southern Canada.”

“a nd a boriginal people weren’t treated the same because it was presumed that it was their home and somehow they were going to make it by.”

of the many problems that this creates is the majority of the people coming in were Caucasian, and they appeared to be treated a lot better and with more respect than anyone else, and so you create a kind of

Resilience

In fact, the split became known as the ‘west side’ and the ‘east side’. “We were using chemical toilets,” Bertha a llen said. “The other part of town, the side with the hospital was lucky, they had flush toilets.”

“Even though we formed a co-op for housing, we didn’t have any utilidor on this side yet. Maybe 5, 10 years later, we finally had utilidor service, and one of the priests said to the little kids, come look here, look at what is going to happen to your poop! He flushed the new toilet, and it was so strange for the little kids to know that they don’t have to see their poop in the pot all the time,” she laughed.

h umour was a way to deal with adversity. a boriginal people in Inuvik began to agitate for their rights. The Indian Brotherhood was set up, and later, Inuvialuit and Gwich’in both pursued and won land claims. They also fought to preserve their culture and to build infrastructure for themselves.

TUSAAYAKSAT SUMMER 2008 32

“One

racism. And people expressed what came out as dissatisfaction and anger. The only thing that was possible to do then was to find a mechanism to support the aboriginal people, as a society, because they weren’t part of that other society.”

Special Feature Nuitaniqsaq Quliaq

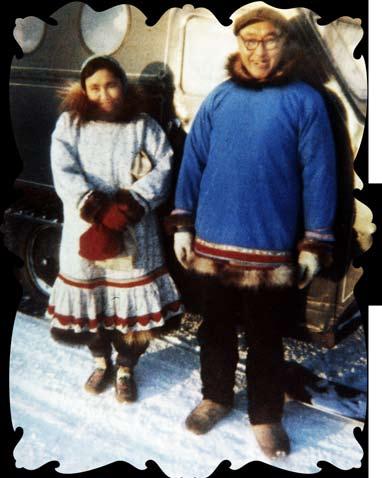

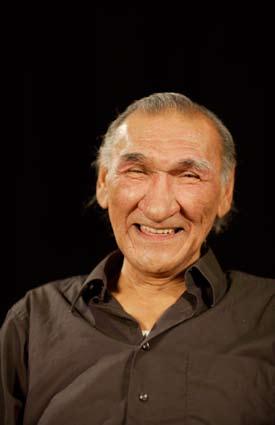

Historical photos left: Nellie Cournoyea (first female and first Aboriginal premier) and Noah Carpenter (first certified Inuvialuit doctor) are good examples of aboriginal empowerment.

HAPPY 50th Anniversary!

Colin Allen as a young construction worker, standing on Mackenzie Road in the early days.

A lady working with bear skulls.

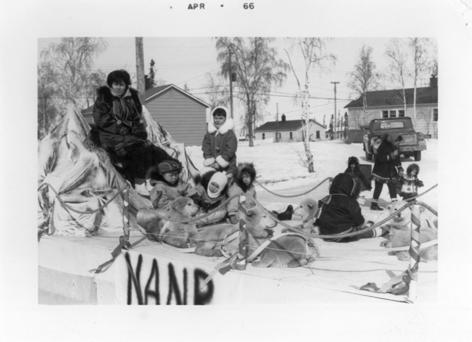

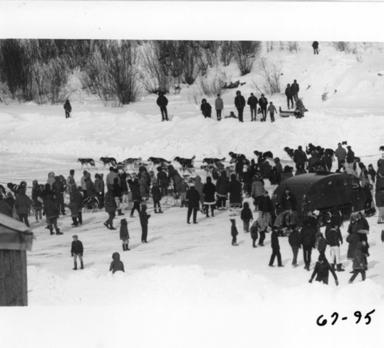

The first spring carnivals, now called jamborees.

Jamboree queen!

Parade time in the early 60s... All historical photos courtesy of ICRC

The research center.

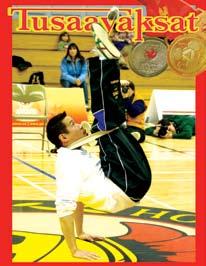

Edward Lennie, a pioneer of bringing back a rctic s ports still remembers what it was like to hold practices in Ingamo h all. h e is proud of the n orthern Games Boys that he nurtured, who are in turn training the next cohort of athletes.

a boriginal people in Inuvik wanted to celebrate their gatherings in a sound structure that belonged to them, instead of an old hudson’s Bay building that was condemned. The ‘Ingamo’ in Ingamo h all friendship Center is a combination of the words ‘Indian’ and ‘Eskimo.’

Celebration

“We all live in harmony,” said Bertha. “We all belong to respective groups, but we’ve learned to live in harmony in small communities. Everybody works together. If there is going to be a big traditional dance, that’s just not for Inuvialuit or just for the Gwich’in, it’s for everybody. Everybody put their resources together, to put on a big celebration.”

n ellie is proud of the people like Edward Lennie, who brought back a rctic s ports by volunteering and teaching youth what he could about the traditions. “ n ow we’ve got major drum dance groups, and certainly arctic sports, which really began here, and are promoted all over the Arctic now. It takes people who are determined, who find a way to get it done,” she said.

s he looks back at the recent Inuvialuit history in the region. “They’ve evolved since the early whaling days in the 1900s, there has been a lot of changes in a short period of time. The religious factors, the DEW Line situation, the building of the town of Inuvik. Every ten years there was something for people to adjust to, to try to get the most out of the new opportunities.”

Inuvik also went through two oil and gas boom-and-busts in the seventies and eighties, and suffered economically when the Canadian forces base in Inuvik was closed down in 1985. More recently, there is anticipation that a boom will come in the form of the pipeline that might be built in the Mackenzie Valley. “Inuvik has never been able to define what kind of community it is, because we are always

anticipating some kind of economic base that we can rely on, over the long term,” she said. “Inuvik, as far as I can see, is thriving, wants to thrive, wants to be important and wants to take its place in society. There are a lot of people putting effort into it,” she said.

n ow celebrating its fiftieth anniversary, the town of Inuvik boasts a diverse and harmonious population of about 3,500 people, and continues to be the regional government and transportation hub of the Western a rctic. The Dempster h ighway (built in 1979), as well as n orthern-run air services, has brought tourists from all over the world to explore the unique culture and stunning nature in Inuvik and the surrounding area. The town is also host to some of the largest industry, arts, and entertainment events in the n orth. a boriginal people such as the Inuvialuit and Gwich’in have greater control over their assets and voices with the establishment and successes of their respective land claims corporations. s outherners who want to do business in the area now have to first consult its native owners. a rctic sovereignty also means that Inuvik is now strategically poised to be important once more.

“When Inuvik was first built, we would never see an aboriginal person who drove around in a truck, maybe a big gravel truck to build up the airport…and many years went by before you saw aboriginal people actually owning their own vehicles, and their own infrastructure. s o that’s good, the challenges, I think, have made a lot of people move forward,” smiled n ellie.

TUSAAYAKSAT SUMMER 2008 34

Special Feature Nuitaniqsaq Quliaq Inuvik in construction.

The infamous utilidor.

Nurses giving children medication.

Paraders on a kayak pass by Slim Semmler’s store.

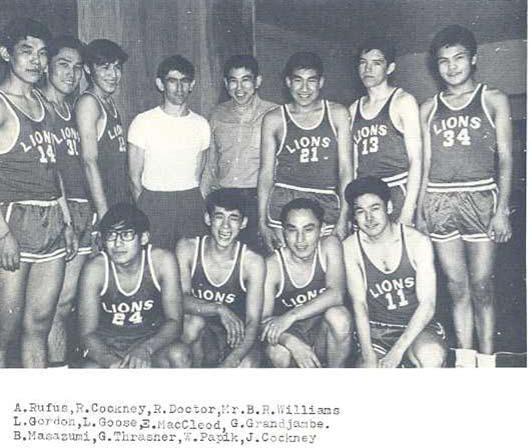

The LIONS basketball team

Trucks were decorated back then too!

The old Mackenzie Hotel.

Paraders on a kayak pass by Slim Semmler’s store.

The LIONS basketball team

Trucks were decorated back then too!

The old Mackenzie Hotel.

Grade Six students at Sir Alexander Mackenzie School sent us some very creative and awesome entries! We had a hard time choosing amongst all these great stories about your time out on the land. Here are the winners!

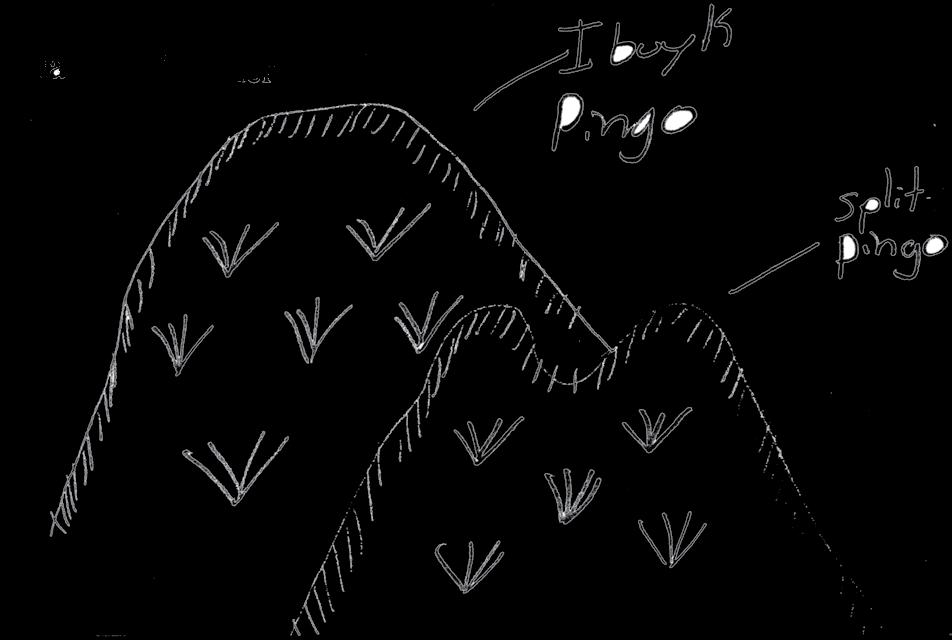

PINGOS

1st Mikaela Cockney-MacNeil

2nd Robyn Rinas

3rd Hailey Verbonac

4th Carina Saturino

TRAPPING

1st Robyn Rinas & Nicole Ellsworth

2nd Alison McDonald

3rd Hilary Charlie

We also used illustrations by Alison Burns

John Gruben

Darci Frost

Jozef Semmler

Matthew Skinner

Elena Joe

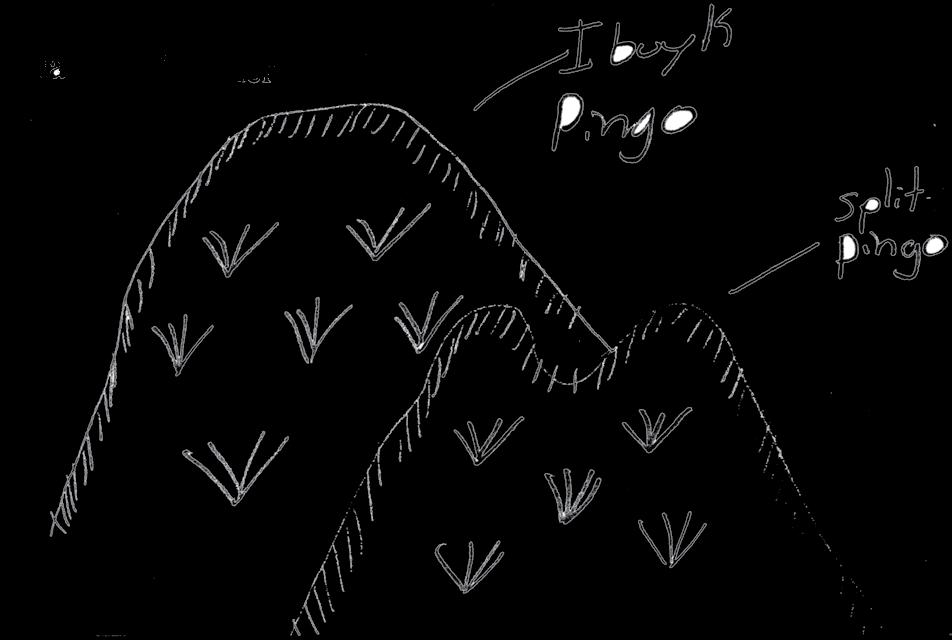

1st Pingos

By Mikaela Cockney-MacNeil

When you think ‘pingo’ and you don’t know what they are, you might think it’s a type of penguin. But really, it’s like a hill. The difference is, when a lake dries up or joins a river to go to the ocean, the moist ground left behind by the lake loses its moisture underground into the permafrost. There, it freezes and becomes an ‘ice core.’ After a few years a pingo will start to grow. As the ice core grows the pingo grows.

Pingos are like people. They have a lifespan. They start out very small and grow every year. But when they’re done growing, the ice core melts and shrinks.

It is important not to drive skidoos, four wheelers, or anything like that because it takes pingos tens to hundreds of years to grow. They can only be found where there is permafrost. They can be found in Tuktoyaktuk, Alaska, Greenland and the Norweigen island of Spitsbergen, the Nertherlands, as well, near Zwaagwesteinde in the province of Fiesland, and also in the provinces of Drenthe and Groningen. The second largest pingo is in Tuktoyaktuk.

36

Grade Sixers from Sir Alexander Mackenzie School go with Parks Canada to learn about the Pingos!

2nd Pingo Pride

By Robyn Rinas

On April 9 th and 10 th, Mrs. Stringer’s and Mr. Murphy’s Grade Sixes went to Tuk to see the pingos.

The pingo process is, first the lake gets drained (naturally), and then the moist soil freezes. After that the permafrost pushes it together to form a big ball of ice. Last but not least the snow melts down and freezes with the ice underneath. So, the pingo grows larger.

In the summer, the snow on and around the pingo melts, and seeps through the pingo before freezing and turning into ice. This causes the pingo to grow.

We should protect the pingos because they are not growing anymore. It’s not good when they are littered on or driven on. A way to protect our pingos is to not drive on them. Sleds, toboggans, and crazy carpets are ok. ATVs, skidoos, cars, trucks, dirt bikes, and things like that are damaging our pingos. Littering on the special unique hills that we call pingos is as bad as littering on the floor in your house.

The most dangerous way of killing our pingos is fires! Last summer, half of a pingo, almost the whole pingo, got burnt. People went to the pingo, built a fire, and when they were getting ready to leave, they thought the fire was out. But it wasn’t. The smoldering from under the fire didn’t get burnt out, and soon enough, when the wind came, it blew the fire right onto the pingo. Now that pingo can’t grow anymore, because of the fire.

Pingos also die when permafrost becomes exposed and it slowly starts to melt. It stops from growing then.

3rd Pingos

By Hailey Verbonac

By Hailey Verbonac

Pingos are made when a lake dries up and the moisture freezes and turns into ice. After a few years the ice builds up and turns into a small ice mound. The pingo gets bigger every year. The lifespan of a pingo is about 1,000 years, but that’s just a guess. No one is 100% sure. Pingos can be found in Tuktoyaktuk, Alaska, Spitsbergen, Holland, Zwaagwesteinde, Drenthe, and Siberia. Small pingos have rounded tops and bigger pingos have a cone-shaped top. Pingos are generally classified as hydrostatic (closed system) or hydraulic (open system.) The biggest pingo in the world is in Siberia and the second biggest is in Tuktoyaktuk. It’s really important to protect the pingos because they are vital to the environment, they might die if you skidoo or bike on them, but you’re welcome to walk on them.

Youth Speak Up Nutaqat Uqaqtut

Photos courtesy of Melinda Gillis

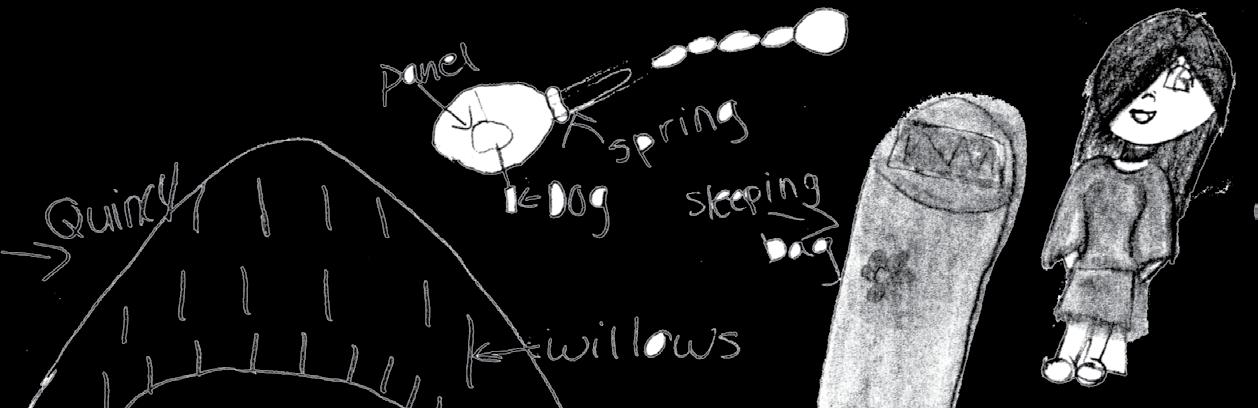

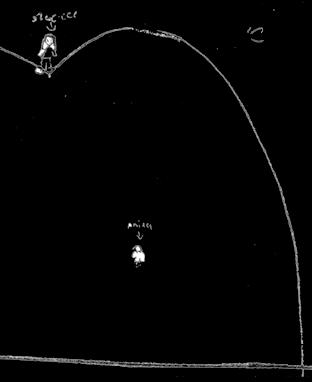

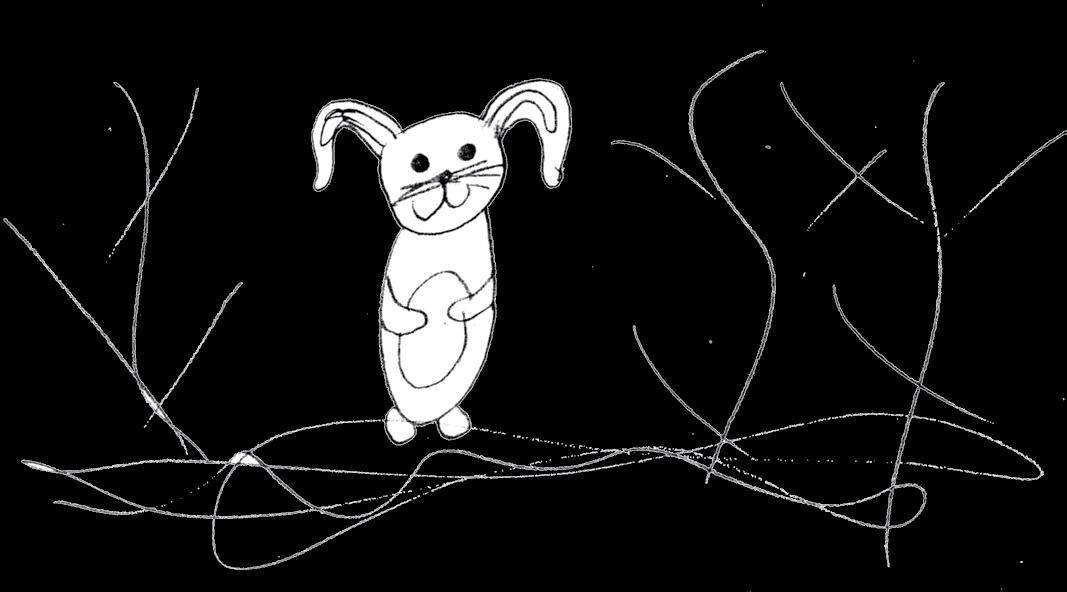

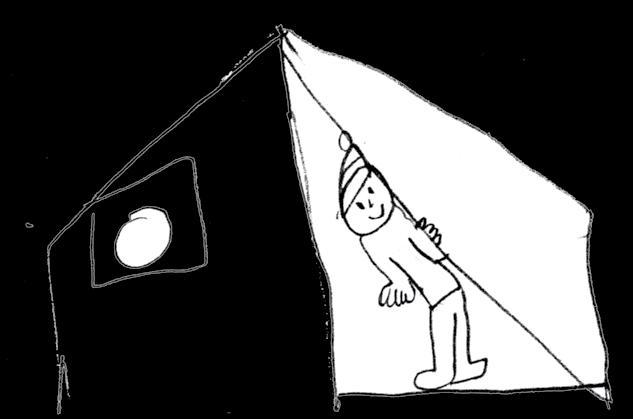

1st The SAMS Nunami Camp

by Robyn Rinas & Nicole Ellsworth

On April 17th and 18th, Mrs. Stringer’s Grade Sixes, along with Mr. Murphy’s Grade Sixes got the opportunity to go out to SAMS Nunami Camp, for two days and one night. We learned how to trap rabbits with snares, and we also learned how to trap muskrats. Here’s how to set a trap; 1st you get your trap. 2nd open the dog, which will be found on the right hand side. 3rd pull down on the spring, which is located at the back, this will separate the jaws. 4th you put your trap where your hoping to catch something. 5th go back to check your trap in about a day or two, you may have been lucky and caught something.

We also learned how to make a fire . Here’s how; 1st get shelter so the wind doesn’t blow out your fire. 2nd get dry sticks, or bark off a tree. 3rd you’ll need some matches. 4th pile up your sticks, and your bark if you got any. 5th to start your fire, get one match, light it, and then place it in between the sticks. If the match burns out, use another match.

We even learned how to make a Quincy. 1st you pile up the biggest pile of snow that you can. 2nd let the snow harden for about an hour or two. 3rd then go and get some willows about 20 cm long, 4th stick the willows on top of the Quincy. 5th dig the snow out to just the tip of the willows, if you go any further up, the Quincy will collapse. There you go your very own Quincy! That is what we did on the land!

2nd Trapping in the North

by Alison McDonald

Trapping was a very big tradition in the North and other parts of the world. It’s very important to have programs to teach other about trapping, survival skills and how to respect the land by only taking what we need. We learned how to catch food with traps and how to build a fire when out on the land. We saw how to set a 1 1/2 spring, 3 spring and watched how strong a conibear trap can really be when set. To build a rabbit snare, we took a piece of wire and wrapped it around our head twice. We twisted the end and put the other end of the wire in a loop to make a snare. We set in between tree branches so the rabbit could not go around the branches.

To build a fire we dug out a place in the snow to start the fire, we gathered dried twigs from a pine tree with green and black stuff on it that looked like moss on the dried twigs. We found a thick stick that could stand up to put over the fire to boil water. We filled an old coffee can with snow and put it above the fire with a stick. We lighted the fire but it didn’t start as quick as we wanted it to but it soon started. I thought it was great to learn about trapping on the land.

TUSAAYAKSAT 38

3rd The SAMS Nunami

Camp

by Hilary Charlie

by Hilary Charlie

On April the 14th our class and Mr. Latour’s class had the opportunity to go to the SAMS NUNAMI CAMP. When we got there we met a man named Archie. While we were there we went to the Mackenzie River Main channel. Then Archie showed us how to set the 1, 1 1/2, 2, 3 spring traps, some of us had the chance to set some spring traps and then he talked about the conibear trap. Then he talked about how the conibear trap is a quick kill trap and and when the animal is trapped in the spring traps it sometimes chews off its own paw or leg. But Environment Natural Resources wants more people to use the conibear trap because it’s a quick kill trap and the animals don’t suffer. A really fun part of the camping trip was when we went out looking for muskrat push ups, also we got to make our own snares and set them. Then we got to boil water on our own. While I was on this trip they told us that we always have to respect the environment. I learned many new things on this trip and ways to set different traps. I am glad I had the chance to go on this trip to the SAMS NUNAMI CAMP it was so much fun.

39

Youth Speak Up Nutaqat Uqaqtut

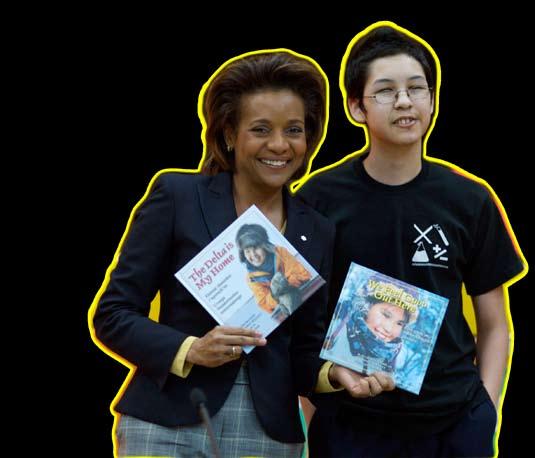

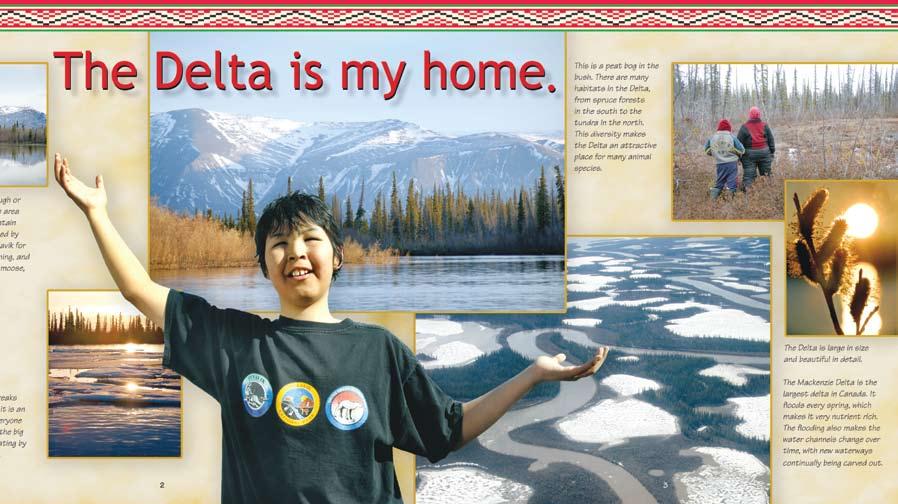

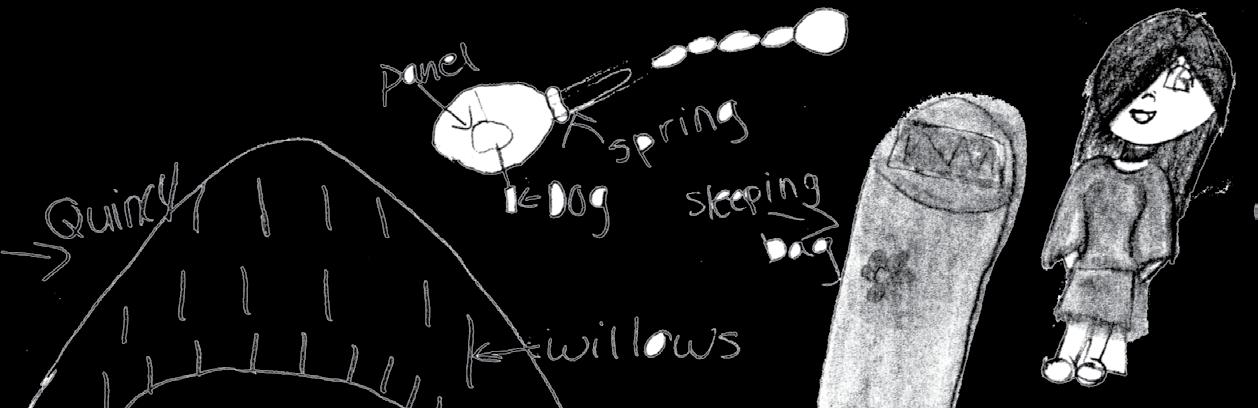

Tom Mcleod’s First Book

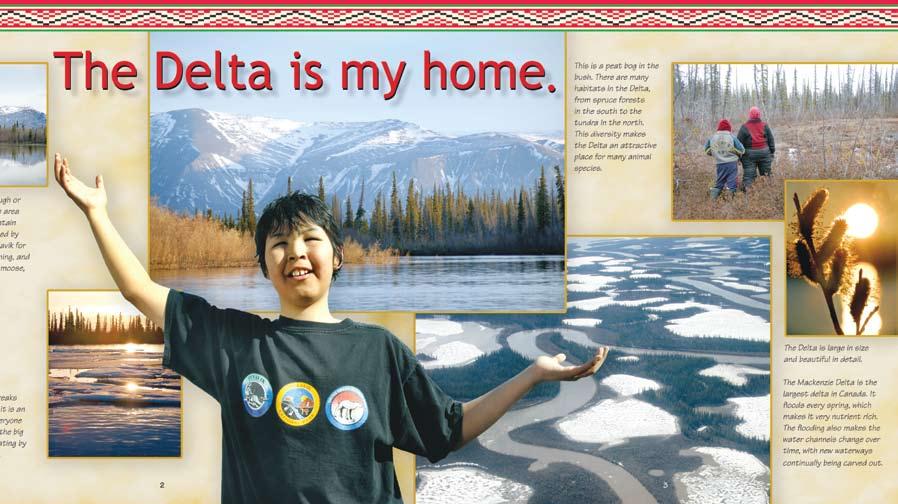

Tom McLeod of a klavik had what he calls a “once in a lifetime” experience. h e was in Calgary and yellowknife this May for his first book launch. “It’s cool to have a book made about our travels” he said, “a nd I am thirteen.” Tom, who was known even as a very young boy to tell stories on CBC radio, is the author of The Delta is My Home. In his book, Tom takes us right to his home, showing us through photographs and anecdotes the life that a young boy leads in the Mackenzie delta.

“I used to be a high school teacher,” said Mindy, “and kids would ask me why are there no good books about us? I wanted to help people tell their stories, and for it to look stunning.” o ver four years, Mindy sourced out sponsors from local Indian bands, Inuit organizations and government. “It’s a huge partnership between organizations,” she said. The logistics of traveling all over the n orth to work with the storytellers is often complicated.

Mindy and Tessa Machintosh (photographer) had intended to go to Aklavik in order to work with Ian McLeod, Tom’s father, but the flood that happened in a klavik then meant that Ian was too busy helping people in town to work on writing. “That’s when we discovered that Tom was the storyteller of the family,” said Mindy.

Tom and his sister ocean took Mindy and Tessa all over a klavik. They would hunt muskrats from midnight till six in the morning (that is when the muskrats are most active) and then work in the day on putting words to paper. “Tom wrote his book right there on the floor, his voice carries through the entire story,” said Mindy.

Tom said he might write another book someday. “I’ve so much resource material to draw from,” he said. “I still tell stories on radio once in a while.” The grade 8 student had advanced onto doing grade 9 English in school.

In the book, Tom and his family go on hunting trips and celebrate Tom’s unique background of being both Inuvialuit and Gwich’in. s idebars provide information about the history of a klavik, and the animals that are important to its people. Tom’s book is the first in a series of ten books, where Mindy Willett, editor and coordinator collaborates with aboriginal storytellers from across n WT. The other book that has been published so far is about the Gwich’in culture, Julie- a nn a ndre’s We Feel Good Out Here

o ther books in the series include a book on beluga whaling in Tuktoyaktuk, and another from u lukhaktok. Tom’s book can be found at book stores in Inuvik, as well as at the local and school library. Tom will also be hosting a creative workshop with youth at the Great n orthern a rts festival in Inuvik on the 13th of July.

TUSAAYAKSAT SUMMER 2008 40

The book begins with a flood in Aklavik, where local people demonstrate the town’s motto of “Never Say Die,” entertaining visitors with doughnuts and trips on the land. Tom’s father Ian is a renewable resource officer, and it is clear that he has taught Tom to respect the land.

Youth Speak Up Nutaqat Uqaqtut

Tom presented the Governor General with his newly published book at the Youth Town Hall in Inuvik. Behind them is a spread from his book.

Arctic Rocker DEBUTS ALBUM

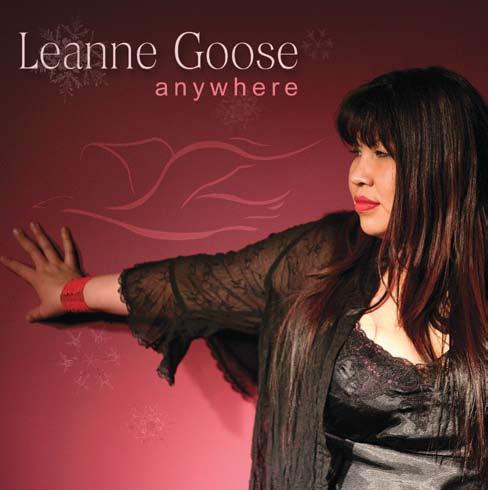

Leanne Goose, born in Inuvik, raised in a klavik and the s ahtu, has worked hard to establish herself as a renowned “a rctic rocker.” h er music, a blend of rock, country, and blues, is ever changing and evolving, but continues to reflect a life lived in the n orth. h er newly released album, “a nywhere” was created in the n orthwest Territories, and recorded in a small cabin in the woods of Whitehorse. “The music has to reflect the winter weather, the vast extremes, at one moment soft and sunny, and the next cold and hard and a pain in the ass when you step out the door.” h er new album, Leanne says, is exactly that - an effort to capture a rctic rock.

With a grant from the Canadian Council of the a rts, Leanne has designed a personal program to allow her to train with other experienced musicians, simultaneously studying classical music theory, piano, and the guitar in an environment of mentorship and collaboration. “ k nowledge of a livelihood built on the music industry can not be learned in a book. I want longevity in my career.” This longevity, Leanne says, will come from developing her stage presence, fostering her creative spirit, and never ceasing to develop as an artist. Learning to read and write music has helped her focus her song writing, and facilitate an assessment of her needs as a musician. “Most important,” Leanne says, “is to pay attention to your body and who you are as a creative person. s o many artists don’t do this.” Leanne says that being a mother is primary. With two sons of her own, Leanne’s motivation is not only for herself. “I want my children to see that it is possible to take life’s passion and make it whatever you want to make it.”

In fact, teaching seems to be Leanne’s latest passion. “Children who play music have better grades, and more confidence. I feel strongly about the teaching element, to foster music and build the creative spirit. We have tons of talent in this community, some just need a little push, others some hints and some can do it all on their own, but I want to be part of guiding and shaping that process.” Leanne’s music has encouraged her to learn to let go of issues with self-confidence, and given her a voice.

Words by Lindsay Trevelyan

‘Inuvialuit,’ ‘Mackenzie Delta,’ ‘Mad Trapper,’ people stop what they are doing, and they look, and listen.” This is the power of music, and something Leanne says is important to offer back to her home.

for now Leanne is going to keep learning and studying with her mentorship program. s he encourages her audience to keep an eye on the website www.leannegoose.com, as there will be new music soon. s he and song-writer and guitarist Laurie Mac n abb are gearing up for a new album. “I am excited, this is going to be quite a ride.”

41

“ Once I tell my audience where I am from instantly the ice is cut and people are locked in, as soon as you say ‘Arctic,’ ‘Inuvik,’

In The News Tusaayaksani

Leanne’s debut album Anywhere has received much acclaim since its release this spring.

Photos courtesy of Leanne Goose

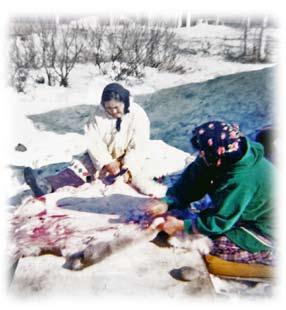

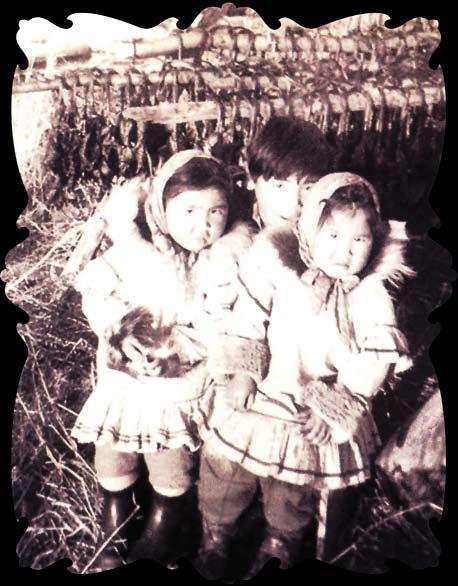

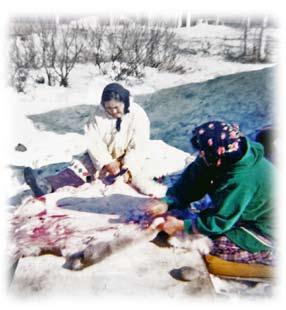

Motherhood as an Inuk (in

Tusaayaksat asks Emma Dick and Sarah Tingmiak to share what it was like to be a mother in the Mackenzie Delta in the 1950s. Emma and Sarah both had 12 children each, while Sarah also adopted a child. Below is an edited transcript of our conversation.

How old were you when you got married?

Sarah: I was 18.

Emma: I got married in ‘42.

What was it like to be a young women then?

Emma: Our grandmothers used to be really strict. You can’t go around with anybody until you get married. Our people were already religious before we were even born. We all got baptized in Aklavik and confirmed in schools and all that. I was seventeen years old and married when I had my first baby.

d id you get to choose whom you married?

Emma: I chose myself.

Sarah: My dad told me: you are going to get married. I didn’t like it.

Emma: Tell her about your first boyfriend.

Sarah: Yeah, my mom didn’t want him, he couldn’t trap.

d id you fall in love with your husband later?

Sarah: Yes, he’s a good guy. A month after I got married, I had a baby. Really fast. I had 12 kids, 11 with my husband (laughs). I was eighteen.

d id your husband like the first kid?

Sarah: He liked him better than all his kids. He’s good that way. My mum and dad took my first kid when she was about six.

Emma: There was not much shacking up in the olden days.

What was the average age then, when girls were getting pregnant?

Emma: 15, 16 years old…well, some of them were young, but it wasn’t all the same.

How did you know when you were pregnant back then? d id you ever use birth control?

Emma: We didn’t know about things like that. We didn’t even have doctors until the 60s, 70s. Today people can have only

TUSAAYAKSAT SUMMER 2008 42

the 1950s)

Sarah Tingmiak with her child Esther Joe.

Photo courtesy of Esther Joe.

one child, and then tie up their wombs. I knew one girl, in the early 60s, who took birth control pills. But I didn’t believe in it then. I had a baby every two years. And then when we got older it just stopped.

How did it feel each time you were pregnant again?

Emma: Good. You didn’t feel that you were losing your freedom?

Emma: (laughs) We need lots of people in this world. When Inuvialuit have babies, the elders used to be so happy for you.

What was giving birth like back then?

Emma: We had midwives all over. Some of these ladies are very good. They go anywhere, to bush camps, whaling camps, summer camps. The first baby was really hard. I was in labor for two days I think. The midwife told me, the first one is very hard. But the second one is going to be better, less hard than the first, and the tenth baby will be just like nothing.

I delivered one baby in my life: Esther Joe, Effie Roger’s daughter. I was so scared. We delivered her at Hershel Island.

November 21, 1963, I think. Sadie Simon was the baby sitter, she took all the kids. When a woman’s having her pain, they don’t let the kids be around the house.

My goodness sake! A baby. We didn’t know she was pregnant. We didn’t know what to do. She said the water had already come last night. No water, gee, what are we gonna do.

Fix her up. We better ask the Lord to help us deliver that baby. We don’t want the baby to die. We said a prayer. We were young, too. I was around 39 or 40, still young. We had a good prayer. We asked the lord to protect us and help us to deliver that baby. So the mother wouldn’t die. We were so scared she might die.

She was in labour and finally the baby came. It was just like a mottled baby. Like the color grey. And I told Effie, I cut, I took the cord, tied it, and took the scissors and cut it.

I told Effie to grab a diaper, she was so scared. The afterbirth is gonna come, I told her, you take this, I’ll take the baby. As soon as the after birth comes, the mother is ok. I took the hot baby blanket we had on the stove and wrapped up the shivering baby. We put it in a box beside a furnace stove, where the warmth is. She’s alive today, and she is married! She always thanks me for delivering her.

Sarah: Me too, we delivered a baby in Sachs Harbor. I was scared, too.

Are there any rituals or medicine that people did back then?

Sarah: We didn’t have anything.

Emma: Only scissors, and you need thread, to tie it up. And you clean the baby’s nostrils and mouth out with a ptarmigan feather, to make sure there’s nothing like throw up in there, that it’s clean.

Emma: There are lots of doctors now, but when we went to the hospital then, we just had check ups once in a while when we are pregnant. We spent time in Aklavik, to wait for our babies to be born.

Sarah: When we had babies in the hospital then, they kept us for ten days. Now they leave the hospital in just a few days.

What happens after giving birth?

Emma: We didn’t have maternity leave (laughs.)

So life goes back to normal?