Medias Res Gallery platforms Farsi-speaking artists

Julian Forst Senior Staff Reporter

The Vancouver Iranian Visual Arts (VIVA) Alliance is set to open their new Medias Res Gallery curated by UBC alum Maryam Babaei on March 27. Their inaugural exhibition, Henna Night II / Shabe Kheena II, will feature a series of textile works by Afghan-Canadian artist Hangama Amiri.

VIVA Alliance is a non-profit organization founded in 2023 with a mandate to platform and support emerging Farsi-speaking artists in the local scene. Beginning with a pair of annual exhibitions at the Yaletown-Roundhouse Community Centre featuring local artists like Vahid Dastpak, Amir Aziz and Nakisa Dehpanah, the alliance has grown to the point of establishing its new headquarters in Railtown.

The opening of the Medias Res Gallery — named for the Latin phrase meaning “in the middle of things” — entails what Babaei calls a moment of “rapid growth” for the VIVA Alliance.

“It’s going to be, basically, the development of the same ideas that we’ve had. [We want] to consolidate the activities that we have been doing and to build on them,” said Babaei in an interview with The Ubyssey.

In spite of the collective’s roots in Vancouver’s Farsi-speaking diaspora, Babaei and VIVA Alliance as a whole are quick to highlight the inclusive nature of their mission.

“Our commitment is to creating an intercultural exchange,” said Babaei, “and interculturality is not possible if your approach is exclusive. We don’t plan on specializing in the works of one particular diaspora at all.”

The gallery will serve many of VIVA Alliance’s needs as a growing art organization, including office space and two resident studios, as well as a smaller capsule exhibition space in addition to the main gallery hall which is currently preparing to host Amiri’s exhibition.

According to Babaei, this smaller space will play host to regular workshops, lectures and activities aimed at promoting cultural dialogue and understanding, including weekly drawing sessions and artist talks associated with current exhibitions.

Amiri’s Henna Night II / Shabe Kheena II, which runs from March 27–May 2, focuses on a series of the artist’s textile works depicting traditional pre-marriage ceremonies, including one large scale piece crafted by Amiri specially for Medias Res’s inaugural exhibition.

“Amiri [is] such an accomplished artist who [has] such a distinctive

diasporic lens. That was fitting as a beginning and an inaugural exhibition for [Medias Res],” said Babaei.

“Even though she has a very culturally specific lens [and] autobiographical approach … she finds a way to highlight the universality of the nostalgia that she’s experiencing, the sense of loss that she’s experiencing, [to create] a coherent idea of home, a coherent idea of belonging.”

Babaei also stressed the enrich-

ing value that “exposing yourself to the artistic activity that is happening in your vicinity” can hold for students and their understanding of the world around them.

“We hope that UBC students, young people, will come and see this truly accomplished artist [and] hopefully leave intrigued and interested to learn more about the situation of women in Afghanistan and the great art that comes out of

that region.”

The Medias Res Gallery has several exhibits lined up for the rest of the year after Amiri’s exhibit closes in May. June 26 sees the opening of Re-encounter Mythical Entities curated by Wen Zhu, followed by a hallway exhibition in the gallery’s capsule space of the work of Anishinaabe/Ukrainian artist Speplól Tanya Zilinski entitled S’íwes te Tém:éxw / Teachings of the Earth U

SALLY, BE A LAMB, DARLIN’ // She’s a Lamb! details the unapologetic lengths one performer will go to claim the stage

Sophia Samilski Senior Staff Reporter

She’s a Lamb! by UBC alumna Meredith Hambrock explores the fine line between ambition and obsession. The novel follows Jessamyn St. Germain, a young aspiring actress with a passion for musical theatre who’s willing to sacrifice everything, including her health, dignity and sanity, for a standing ovation.

“I think you do have to be a little bit delusional to complete anything or to put yourself out there — you have to really not worry about the truth of what might happen,” said Hambrock in an interview with The Ubyssey

While auditioning for the lead role of Maria Von Trapp in a production of The Sound of Music, Jessamyn instead gets an offer to mind the child actors. Renée, her singing coach, subtly proposes that perhaps she’s meant to be nearby for a reason.

“Think about it. It really does mirror Maria’s journey, keeps you close to the children, has you at the show every night. It’s almost as if she’s casting you as the understudy without casting you, you know?” she tells Jessamyn.

Clouded by her vanity and knowing that the production company can’t afford an official understudy, she is easily convinced by Renée. Jessamyn believes it must be an unspoken agreement that she will step up if the actress casted as Maria does fail.

The start of the story reads almost as satire, following a snobbish actress as she’s forced to babysit

children on set while watching her rival play her dream role day after day. As the production unfolds, Hambrock reels you in as the plot gradually transforms into a psychological horror as Jessamyn’s desperation peaks, ultimately driving her mad. Hambrock builds tension, mirroring a theatrical performance.

I found it hard to put the book down once her ambition quickly mutated

into something more ruthless, and gruesome, as she descended deeper into her delusions of grandeur.

“This is almost like a horror story about not knowing … how scary it can be to put yourself out there and the level of almost balancing delusion and reality and how easy it is to get lost,” Hambrock said. “If you’re super realistic about yourself and your own talent as an artist, you

might never take risks.”

While Jessamyn has landed the odd commercial here and there, she believes her window of opportunity is closing. In her late 20s, she sees her age as a death sentence for an aspiring actress.

In these moments, I sympathized with Jessamyn. As women, I find we are our own worst critics.

“What sort of female performer builds a career in her late twenties? In her thirties? You know it’s not true. As much as we all want to pretend it isn’t, it is. I’m too old. And I’m not getting anywhere,” Jessamyn says to a cast member.

Beyond her struggles at work, Jessamyn is haunted by her own father’s disapproval, who looks down on her career choice, only exacerbating her lack of self-confidence. She sees playing Maria as her last chance to prove her worth. With this shame looming over her, she finds herself trading her selfworth in return for the inconsistent approval of men, letting their validation define her as an actress.

“She wanted to step forward as this ideal woman. She wanted to be desired by everybody. To do something creatively, and doing it for outside reasons, is maybe something that will drive you a little over the edge and make you behave [in] an unhinged way,” Hambrock said.

When I first met Jessamyn, I thought she was insufferable — head held high with a chilling detachment to others and the world around her. She seemed to care for no one but herself, obsessed only with her own desires to be Maria. I found myself rolling my eyes at her

snarky comments, dismissing her as selfish. But as showtime grew closer and closer, I began to pity her. Perhaps it was the way she twisted the truth into one that fit her narrative, or how I started to see her quiet desperation grow loud and impossible to ignore, underlining how fierce, yet equally fragile she was.

Hambrock recalls a story familiar to many, illustrating the vulnerabilities of young, aspiring actresses navigating an industry where many are left to be taken advantage of.

“I think it’s a not so subtle negotiation with patriarchy as well,” Hambrock said. “[It’s] exploring the relationship between what drives you to make stuff and to live as an artist.”

“I truly believe that there are a lot of stories like hers out there that we just haven’t heard.”

In the absence of meaningful female relationships, Jessamyn has a unique connection with Renée, and the two bond over their shared love for the arts. Jessamyn continuously rushes back to Renée’s house throughout the story, securing another singing lesson in exchange for a safe place to indulge in her passion, reminding herself each time that someday it will all be worth it.

Jessamyn’s story is a tragedy, not just because she loses everything, but because no one is there to save her as she unravels. She’s a Lamb! serves as a cautionary tale about the cost of giving up everything, including oneself simply to be seen, offering a poignant commentary on some of the realities of being a young female performer. U

This smaller space will play host to regular workshops, lectures and activities. COURTESY HANGAMA AMIRI AND COOPER COLE

She’s a Lamb! is set to release on April 8, 2025. COURTESY SIMON & SCHUSTER

Star players don’t win championships. Teams do.

Putting your body on the line for the person next to you, putting in the hard work even when you don’t want to, putting aside your pride for the sake of the group — these are the qualities of a winning team.

The journalist I admire the most once told me reporting works the same way; that the best journalism is done as a team — and he was right.

I was lucky enough to work in a team for this year’s sports supplement and coverage of the two Final 8 national basketball tournaments held at UBC. Although it was full of hard work, late nights, chaos and headaches, it was also full of camaraderie, laughter and memories I won’t forget.

Like championships, Double Dribble represents the best of the best. This supplement covers everything from analyzing the home-court advantage and game day superstitions to profiles of star coaches and players at UBC.

I hope reading this will inspire you to dream big, or at the very least, remind you no success happens in isolation.

— Lauren Kasowski Sports + Rec Editor

Abbie Lee

Annaliese Gumboc

Ayla Cilliers

Caleb Peterson

Colin Angell

Daniela Carbonell

Danielle Simon

Elena Massing

Emilīja V Harrison

Fred Knowles

Ian Cooper

Iman Janmohamed

Luiza Teixeira

Mahin E Alam

Maia Cesario

Navya Chadha

Rhea Krishna

Saumya Kamra

Sophia Samilski

Spencer Izen

When the T-Birds need the crowd’s support, Oskar Ho gets everyone to make

“That’s exactly my purpose as a hype man,” said Ho. “People who love the game,

shot on me,” Ho said. “The Canucks … I know do, what are you going to do about it?’ … has

words by Maia Cesario

photos by Navya Chadha illustrations by Ayla Cilliers

Women’s basketball in North America has seen a meteoric rise in popularity and media coverage in the past few years. Caitlin Clark captivated new audiences with a historic run at the University of Iowa, but the surge of women’s basketball did not begin with just her. While definitely the catalyst for this movement, beneath the headlines and record-breaking performances is a foundation built by relentless women who have fought to grow the sport.

This progress was reflected this year when UBC held both the men’s and women’s U Sports Final 8 national basketball tournaments, marking the first time one school hosted both competitions.

But as the women’s game continues to reach new heights, an important question remains: why is this happening now, and what remains to be done?

At the professional level, the movement toward gender equality in sports is a recent development. The Women’s National Basketball Association (WNBA) was founded in April 1996, less than 30 years ago, as the women’s counterpart to the NBA. Play officially began in June 1997 with eight teams, four of which still exist. The upcoming 2025 WNBA season will feature 13 teams, and beginning in 2026, the WNBA will have its first franchise in Canada, the Toronto Tempo.

Initially, the WNBA saw an immediate surge in popularity and attendance. The excitement of a new sports league and the emergence of former college stars like Lisa Leslie, Sheryl Swoopes and Cynthia Cooper built a solid foundation for the league. Viewership and attendance numbers eventually dropped but remained steady at around 1.5 million

people for the coming decades.

However, after the COVID-19 pandemic, the league struggled to regain its pre-pandemic viewership. An unexpected revival came in 2024 with the arrival of collegiate stars like Clark and Angel Reese, who substantially raised the league’s popularity and helped attract more casual viewers. Their popularity led to record-breaking figures in both attendance and viewership. In 2024, the WNBA set an all-time record of 54 million unique viewers during the regular season and an average of 1.19 million viewers per game — a 170 per cent increase from the previous season.

Natalie Abele, a UBC alumna and a sports management instructor at the University of Portland, believes this recent surge in popularity, with the WNBA in particular, has been “a bit of a long time coming.”

“The talent [has] been there for a long time. It’s just a case that now more people are able to see it and enjoy it,” she said.

Despite women’s basketball having found increased success in both the professional and American college markets, that success hasn’t been matched in Canada.

Both the men’s and women’s championship games are broadcasted by CBC, but the difference in attendance numbers remains stark. Last year, the men’s championship game saw a 93 per cent attendance rate, 33 per cent higher than the women’s, a phenomenon also seen during UBC’s regular season.

This season, the UBC men’s basketball team drew more than twice the attendance of the women’s team — 8,073 total people compared to 3,259 — despite the latter being one of the most dominant programs in

words by Ian Cooper photos by Saumya Kamra illustrations by Ayla Cilliers

the country and boasting exceptional talent such as Mona Berlitz and U Sports Rookie of the Year Keira Daly.

While there is no single path to addressing this disparity, U Sports and UBC’s decision to host the championships at the same venues aimed to give the women’s team a greater platform to showcase their abilities than previously available.

“We’re trying to do something different and really try to elevate sport in a different way by having men’s and women’s together for the first time,” said UBC Managing Director of Athletics and Recreation Kavie Toor, shortly after it was announced in 2023. “It’s pretty special.”

As it stands, women’s basketball is in a better place than ever. After decades of work toward equal respect and treatment, players are finally receiving appropriate benefits and compensation. While many of the actions that governing bodies have taken are minor — Abele mentioned the NCAA rebranding the women’s basketball tournament with the “March Madness” logo — progress is steadily being made.

Last year, the WNBA allocated $50 million to provide chartered flights for its players and signed a new $200 million a year media rights deal. The WNBA players’ union also opted out of the current collective bargaining agreement so that after the 2025 season, the union will be able to negotiate for apt compensation by the league.

But while strides have been made and popularity continues to surge, years of work remain before gender equality is achieved. Abele emphasized that for things to continue in the right direction, equal media coverage is critical.

“Exposure has been really key to driving more eyeballs on the sport,” she said. “That’s what is going to attract more lucrative contracts, like media rights contracts, but also more lucrative sponsorship deals and more investment on the owner ship side as well.” Universities are in a unique position to attract new audiences to sports, potentially transforming casual spectators into lifelong fans. Through influence and leveraging “school spirit,” universities can garner large crowds for almost any sport across genders. However, we still see a trend preference for men’s games over women’s — during UBC’s national quarterfinals on March 13, the men’s team garnered 25 per cent more viewership than the women’s. In the championship finals on March 16, the men’s game had 3,604 fans in attendance, com pared to the women’s 1,744. Gender equality in sports is about more than a fair whistle on the court — it represents larger societal values of opportunity, equity and inclusion. Although the work is hard, Abele highlighted the important role that improving gender equality in sports can play in society at large.

“I think greater equality on the professional level helps trickle down in a way, to kids and youth,” said Abele. “I think [sport] breeds respect for each other. It’s just as important for little boys to see women excelling in sports as it is for little girls to see it.”

Sidney Crosby is one of the greatest hockey players of all time — but he’s also worn the same jockstrap since high school.

Crosby’s convinced his non-negotiable pre-game rituals have played a role in his success, and many other athletes share a similar (albeit less extreme) belief in superstition.

These convictions may seem a bit absurd, but what if they actually work?

“There’s decades and decades of research showing that psychological influences have a certainly substantial weight in terms of maximizing performance,” said Dr. Desmond McEwan, an assistant professor of sport psychology in the UBC School of Kinesiology.

“It could be something around stress management [or] dealing with stressors that you’re facing as an athlete — if you feel like you’ve got the resources to deal with that, then you’re going to be more likely to be able to deal with the waves as they come.”

Delaney Woods is a fourth-year media studies and data science student who plays for UBC’s women’s rugby team. Rugby is more physically aggressive than other sports she’s played, so she needs to make sure she’s in the right mindset before a game.

“I need to dominate. I need to be physically aggressive. So I find, before a game, getting in the right headspace is critical for me to have a good game,” she said.

“If I don’t feel dialed or if I don’t feel like, ‘Okay, I can go out there and crush it today,’ it hugely impacts how I play.”

Woods follows a very specific routine to get in the zone.

Every morning before a game, she eats an everything bagel with cream cheese and jam, then heads to the field early to get herself set up. She pops in her earphones and puts on a specific playlist that differs drastically from her actual taste, with heavier artists like $uicideboy$ over her usual Hozier to “get angry.”

She braids her teammates’ hair, then does her own — always in the same style, because she had a good game the day she first tried it out and stuck with it ever since. She picks a set of spandex from her two that she wears “religiously.” Some of the people on her team wear their socks pulled up to a particular height or folded in a certain way.

When she gets on the field, she doesn’t step on any lines as she makes her way to the team cheer. During warm-up, she always works with the same partner — though she sees that not as a superstition, but as a way to control the level of intensity of contact drills.

Her former warm-up partner recently left the team, so Woods had to work with someone else.

“I switched partners. And then [in] the third game in the season, I hurt my knee … I’ve been out for six months now with a knee injury, and I’m like, ‘Maybe not having the same contact partner did that to me,’” she said.

“Moving forward, I would love to be less reliant on needing the same partner and needing the same structure, but I’ve definitely made peace with the easier ones, like what [I’m] going to eat for breakfast, what song

I’m going to listen to and how [I’m] going to wear my socks.”

Woods’s pre-game routine contains a mixture of superstitions and performance routines, which, for McEwan, “fall under the same umbrella of getting yourself in the right zone.”

“They’re largely around trying to manage stress, thoughts, emotions that we’re having, and trying to control the situation in some regard,” he said.

But although they are all actions that are routinely performed, McEwan differentiates performance routines from superstitions as those directly connected to improving skill execution.

Performance routines include strategies like visualization, specific warm-ups or positive self-talk. As McEwan puts it, these are ways to stay focused on yourself and “control the controllables,” instead of being anxious about external factors you can’t change or expect.

These routines focus on an athlete’s state of mind and body, and draw focus toward these things — superstitions, on the other hand, seem to turn to magical forces for luck.

“With superstitions, there’s still a general desire to get yourself in the zone, to manage stressors,” said McEwan.

“The key difference, though, is that it’s more of an irrational approach and more focused on [the] supernatural or the magic, basically the things that you can’t control .… It doesn’t necessarily help us with our skill execution directly.”

McEwan said that if superstitions appear to work, it’s probably a pla-

cebo effect, “but placebo effects are powerful, and they can be beneficial to people.”

But athletes shouldn’t rely entirely on superstition. The sense of security and stress management from a ritual may be helpful, but McEwan said these beliefs become harmful if athletes completely write off a game just because they can’t complete tasks that can’t be directly linked to their performance.

“That’s why we would probably emphasize and … steer athletes towards focusing more on performance routines rather than superstitions,” said McEwan.

Woods credits her head coach Dean Murten with playing a huge part in helping her team feel organized and link their game performance to skills rather than luck. He sends out the run sheet the night before, and sets up the field ahead of time for the things they’ll be working on.

“He’s very structured that way, and I think that lends aid to us feeling confident in our performance and what we’re able to do, because he’s huge on controlling the controllables and having that set routine,” she said. “Having someone who cares so much about structure also plays into maybe having less emphasis … on our superstitions.”

Superstitions don’t have to disappear overnight, but should be weaned into performance routines, according to McEwan.

“The good news is that there is evidence that we can change these [to] something that’s more adaptive and not going to then be harmful.” U

words by Elena Massing illustrations by Emilīja V Harrison

The women’s Final 8 national basketball tournament was held at UBC for the first time from March 13–16, bringing together the best teams in the country for a three-day championship where only the University of Saskatchewan Huskies would leave victorious.

Most people would be intimidated by such notable competition on their home turf, but not UBC guard Olivia Weekes.

“It adds to the pressure a bit, but I think pressure is a privilege,” she said. “It makes us want to work harder for our end goal, [which is] obviously to get a national championship this year.”

Born in Winnipeg, the fourth-year Arts student was five years old when she started playing basketball, influenced by her dad, who also played the sport in college.

During primary and secondary school, Weekes split her time between basketball, handball, club volleyball and track and field, but had to give some of them up when she got older and had less time to play competitively. Basketball was the obvious option when it came time for her to choose.

“[It] was my main focus,” she said.

Adapting from high school to university basketball was difficult for Weekes, especially after missing her entire senior session due to COVID-19.

“I was still pretty skinny throughout high school, and [I wasn’t] able to develop in my senior year,” said Weekes. “And then coming into university I hadn’t been playing basketball for a year and a half, so it was definitely a tough transition.”

Weekes eventually overcame her struggles to become one of the stars of

the UBC squad, averaging 24 minutes played and 11 points scored per game in her senior season. She also recently surpassed 1,000 points scored in her college career.

But Weekes isn’t too focused on statistics, having only learned about her feat many days after it happened.

“[I’m] really focused on the end goal and building something [to] look back on and feel accomplished as a team,” she said. “It’s about facilitating good opportunities on the floor for my team.”

During Weekes’s process of being recruited by UBC, what truly made a difference was seeing her teammates’ relationships with each other.

“Everything was done on Zoom, so I didn’t actually get to see the campus at all,” said Weekes. “But the main thing that stuck out to me were the teammates, and that made the decision pretty easy for me … seeing how close everybody was on the team and how much all the girls said they enjoyed [playing for UBC].”

Beyond her teammates, Weekes highlighted the community and support she found as a Thunderbird.

“I’ve built a lot of really good relationships and friendships through basketball and the UBC varsity community is super tight,” she said. “Building a lot of friendships through that definitely shaped me as a person for the better.”

As her university career nears its end, Weekes is considering her options for the future.

“I think that’d be an awesome experience, getting to go overseas and play somewhere,” she said. “I definitely could not see myself not playing basketball anymore.” U

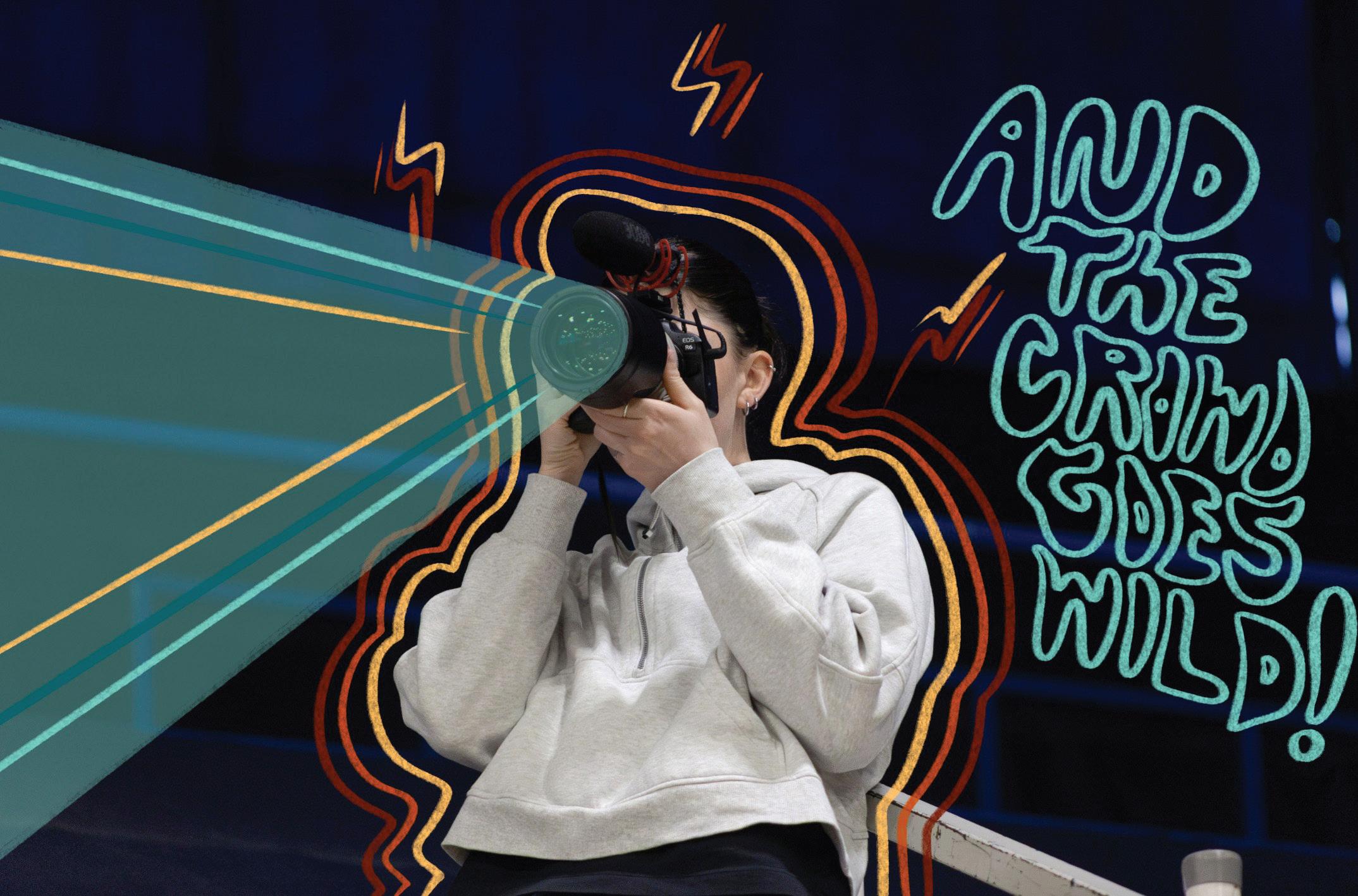

words by Luiza Teixeira photos by Saumya Kamra illustrations by Ayla Cilliers

Two years ago, Ryann Kristmanson was at a crossroads. After being on the UBC women’s basketball team for two years, she was abruptly forced to reconsider her future.

“I came [to UBC] for basketball. I was recruited here. But I had a career-ending injury,” she said.

In a moment, it seemed like she would have to leave everything she had known on campus behind. The injury would separate her from her teammates and coaches — her friends. But as she was pondering the future, a new roster spot opened on the team for her. Not as a player, but as the team’s social media coordinator.

“It kind of just fell in my lap to be honest,” she said. “The transition was weird because it was fast. I didn’t really get to say goodbye to my basketball career as I was starting this .... But I loved it enough that I wanted to keep pursuing it.”

For Kristmanson, basketball was so crucial that, despite not being able to play, she still wanted to be a part of it. She isn’t the only one.

Across campus, there are countless others in roles similar to Kristmanson. Whether they write articles, take photos, shoot videos or generally contribute to the public promotion of sport, they all fit under the umbrella of “sports media.”

With 26 varsity teams at UBC, countless hours go into showcasing the athleticism of the school’s hundreds of student-athletes, across a

wide variety of sports. Or, if you’re Jeff Sargeant — UBC Athletics’s communications and media relations coordinator — you might cover all sports.

Sargeant and his team are tasked with producing media for all UBC varsity programs — a balancing act that is no small feat.

“It’s a lot of student athletes and a lot of programs,” he said. “We want to give as much as we can, but we’re only human, we can only have so much time and so much budget .… A big part of our challenge is trying to get our athletes in as much focus as we can.”

Even those in media roles attached only to one team have plenty to juggle. Malika Agarwal, the media, communications and partnerships manager for UBC’s men’s and women’s swim teams, knows this well.

“The joke around deck is I do everything but swim,” she said.

For Agarwal, providing media support to the team can mean something different each day.

“I think it is an atypical job in that way,” she said. “Sometimes it’s running [and] grabbing a box from the Athletics department, or sometimes it will be sitting down and writing copy for an email [to] alumni supporters.”

On top of these responsibilities, many in-house media staff at UBC are also full-time students. While Agarwal recently graduated, Kristmanson must balance her role with classes.

“It’s definitely a full-time job,

words by Caleb Peterson photos by Saumya Kamra illustrations

especially being one person doing it,” Kristmanson said. “It’s such a great opportunity because I can try it all. I get to have full creative control. But at the same time … it’s a lot to balance with school as well.”

Multitasking across assignments and ideas is just one of the many elements of media that goes unseen by the public, Sargeant explained. While media is inherently a front-facing job, there’s plenty going on behind-thescenes to make the content possible.

“It’s a lot of long hours .... On a Friday, Saturday night, we’re here well past midnight, and then right back at it pretty early the next day,” he said. “A lot of people will see us and our support staff at games, at events, but that’s just a snapshot of all that we do.”

Attention to detail often goes unnoticed. The time spent with a critical eye, ensuring anything going out to the public looks smooth and polished, can’t always be seen in the final product, Agarwal said.

“Every aspect of it — all the aesthetic components to it, making sure that it represents your team and your athletes in an accurate light — I think is more difficult than people maybe give it credit for,” she said.

All this work begs the question — why go into sports media? For Sargeant, it’s simple.

“Do what you love,” he said. “I really enjoyed my time focusing on news as well, but I also had the opportunity … to do some hockey broadcasting

on the side .… It was essentially just following my passion.”

That sense of passion — viewing the tasks of sports media not as additional responsibilities, but as exciting opportunities — is key in the field. Because creating media, in any form, is a labour of love.

Perhaps the best example of this comes from UBC’s men’s volleyball team. This year, their media team took their game to another level, creating Taking Flight, a crisply-produced, in-depth YouTube documentary series following the team throughout their season.

It’s an exceptionally unique project, and it only exists because of the efforts of first-year student Cole Joliat.

While head coach Mike Hawkins had previously considered the idea of a documentary series, it was Joliat who pushed to make the project a reality. From before Hawkins even met Joliat, his passion for volleyball was clear, with Joliat reaching out to Hawkins before even arriving at UBC.

“He was persistent, but not in a nagging way. It was kind of like, ‘Hey, I’m probably not suited to be on the team, but I’m going to UBC anyway…. So I just want to help in any way possible,’” Hawkins said.

That persistence eventually led to an invite into a T-Birds practice, and after meeting with Hawkins, Joliat landed a role with the squad. Joliat pitched the docu-series about the team in that first meeting, and

upon hearing the idea, Hawkins was ecstatic.

“I remember looking at him being like, ‘Oh my God, let’s do it,’” said Hawkins. “[From then], he was there every single day .… he’s just one of those guys who ... is like an unsung hero to what we do.”

One reason why Hawkins is so enthusiastic about the documentary is because, while the project itself is immaterial, it still tangibly benefits the team. The media’s contributions may not be as immediately obvious as some of volleyball’s other staff, but their efforts to tell the story of the program still improves the team — particularly in recruiting.

“[When] people want to come to UBC, people want to know about the program,” Hawkins said. “I can’t tell you how many … parents [of recruits] are like, ‘Hey, we watched every episode of the doc. So when you reached out to our son, we feel like we already know the team.’”

Not only do the efforts of Joliat and the rest of the media team help bring in talent, but they can also help lift up the talent already in the building.

“I think it’s an incredible source of pride,” Hawkins said. “If it’s something like a doc, where you get to see yourself, or you get to talk about how you feel as a part of the program, that just really strengthens the bonds within our team.”

Taking Flight may be abstract in its

team deliverables, but its community building in and outside of the sports circle makes it more than just a video. Wins and losses are important, but they aren’t what makes sport special — the people and stories do. After all, those elements are what initially brought Kristmanson into the field.

“Honestly, in the end, it doesn’t really feel like work. I really enjoy it, and I get to spend time with these girls who I’ve known for so long and who are my closest friends,” she said.

The sentiment extends to someone in media relations, like Sargeant.

“We get to know our student athletes, we know our coaches that we work with very closely … we wanna see them succeed,” he said. “That’s what really drives us, is to put them in lights and get their accolades and get the attention that they rightly deserve.”

While sports media ranges from making Instagram posts to conducting post-game interviews and everything in between, it’s all in service of a greater goal: serving people and telling a story.

“I think sports media and storytelling surrounding sports is one of the most incredible ways that you can bring people joy and hope,” said Agarwal. “That storytelling aspect of it, it’s what pushes people to want to be better and do better. Any role model you have, you look up to them because of their stories and I think sport is no different.” U

illustrations by Abbie Lee & Emilīja V Harrison

Twenty-five years, six Canada West Coach of the Year awards, five Canada West championships, two U Sports Coach of the Year honours and coaching stints with Team Canada and professional players — the resume doesn’t seem to end for Thunderbirds men’s basketball head coach Kevin Hanson.

For one of the nation’s most venerated basketball coaches, the sport is just one piece in a lifelong story.

Born in Regina, Hanson’s first competitive games weren’t at centre court, but at centre ice.

“My body was probably more suited to hockey than it was for basketball,” Hanson said, laughing in an interview with The Ubyssey “That’s where I really learned to be as competitive as I am. Every day after school, every night after dinner, we would go and lace up in an old burning stove shack and get out there and just play.”

His family often moved around due to his father’s work, so Hanson continually found his home by participating in team sports.

“I think you just became a little bit more of a family and were accepted more once you were participating in sport,” Hanson said.

He first started playing basketball during grade two intramurals, encouraged by his parents and teachers to start playing. “I kind of fell in love,” he said.

Eventually ending up in Vancouver, the sport became an increasingly important part of his life; Hanson credits its fast-paced and social environment for his involvement.

“It took over me in grade 8,” he said. “There’s so many more attempted shots at the net, at the goal. I just found it a very … intrinsically fulfilling sport.”

With his high school’s varsity team, Hanson excelled and started to look at where the game could take him.

Playing a year at Langara College, Hanson transitioned from a power-forward to starting point-guard, eventually transferring to UBC in 1984. Named team captain, he highlighted his “claim to fame” as winning

the 1987 Canada West championship while spoiling UVic’s dreams of an unprecedented national eight-peat.

During his undergrad, he had a unique pre-game tradition.

“After shootaround, I would go down to the Commodore Billiards,” said Hanson. “There was a $5 special of a hot dog, a bag of chips and an hour of pool. So I would play — that’s what me and another buddy of mine would do.”

Following university, Hanson hopped between coaching jobs in the Lower Mainland for 13 years before landing the grail: UBC.

“When the opportunity at UBC arose, I thought, ‘Wow, what an amazing thing,’” he said. As of today, Hanson has 614 coaching wins as the head coach of his alma mater team.

“Any competitor will tell you that they love winning. I really love winning,” he said. “[But] all I want is that the players play [to] their max potential, and they become better people and better players because of it.”

Hanson consistently cited former UBC head coach Bruce Enns as hav-

ing had a distinct impact on how he approaches coaching.

“I remember going to practices … we would warm up and that would be the only time we would sweat,” he said. “Then it was more of a lecture.”

“He wanted us to be students of the game — to analyze,” Hanson said. “As an athlete, you’re going ‘Coach, I just want to run’ … he goes ‘Well, in order to play, you got to understand the game like there’s a difference … between being a basketball player and playing basketball.’”

The two still keep in touch, with Hanson saying Enns is still “watching all our games.”

“He’s still analyzing my team. I do cherish that relationship.”

Hanson led the Thunderbirds to the 2025 U Sports Final 8 — his ninth national appearance as head coach. UBC hosted both the men’s and women’s tournaments, from March 13–16, where the ‘Birds finished sixth.

“To be a successful coach, it’s absorbed into your body. It’s certainly not a job and it can’t just be a job,” he said. “It’s a lifestyle.” U

words by Colin Angell photos by Saumya Kamra illustrations by Ayla Cilliers

At every varsity game or school spirit event, he is always there. With his fuzzy wings, loveable bulky feet and customized jersey, Thunder the Thunderbird has represented UBC since 1934. But who’s the person behind the mask?

The Ubyssey had a chance to sit down with Thunder — whose identity has remained anonymous — to answer burning questions about the iconic role.

This transcript has been edited for length and clarity.

The Ubyssey: Are you a student, and if so, what is your year and major?

Thunder: I am in my third year studying engineering at the University of British Columbia, specifically biomedical engineering.

The Ubyssey: How did you find out about being Thunder? What was that like?

Thunder : Back in first year, I was looking for a job that was fun [and] exciting, trying to get myself involved in sports and a nice workout to integrate into my school-work balance. I was going through the [UBC] Athletics career page, and I came across this position that was open. I just applied, got my resume in and didn’t really think otherwise about it. But they reached out, and they were willing to interview me and so I underwent the hiring process. I ended up getting the job, and luckily, I ended up really enjoying this job, so I stuck with it throughout the years.

The Ubyssey: When you were applying for the job, did you need any prior qualifications?

Thunder: When I applied, they asked me if I had any previous background experience as a mascot. In high school, one of the teachers asked me if I wanted to be [our school’s] mascot, because at the time, my high school was a pretty small high school, and no one really wanted to be the mascot. So I volunteered, and one path led to another, and then that got me here.

The Ubyssey : What’s your favourite part about being a mascot?

Thunder: My favourite part about being a mascot is interacting with fans — giving them a high five, giving them hugs, seeing the smile on their faces. It’s really rewarding at all the games and at all the social events.

The Ubyssey : The Thunderbird has a long and storied history at UBC. How do you see your role in promoting athletics and recreation at the university?

Thunder: I definitely embody the community of athletics and all the athletes and all those values. I think it’s really important to have a connection between athletes and the crowd, and I think Thunder does a really good job at that. Sure, the game is going on, but having the fans interact with the embodiment of the university and hav[ing] the fans follow chants and drumming rhythms — all that is really very cool.

The Ubyssey: What is your mindset for getting to a game and being on a high energy level?

Thunder: It’s having a lot of confidence in yourself. I normally am a really shy person, but if you put on the costume, you become a whole new person. You don’t really act like how you would if you were yourself. The mask gives you a sort of anonymity where they’re not laughing at me as a person, but they’re laughing with Thunder and all the jokes that he makes [and] how he interacts.

The Ubyssey: What is the visibility like in the suit? How well can you see and move around while wearing it?

Thunder: Surprisingly, not as bad as people would think. I have no trouble getting around anywhere that I would probably want to. And as for visibility, it’s not the greatest ... but it’s no different than putting on a narrow set of sunglasses.

The Ubyssey: How often does the suit get washed and does it get really hot and sweaty in there?

Thunder: I get asked that question a lot. The suit gets washed between every single game. We have several suits and they get put out in rotation. As for how comfortable it is … it is not unbearable. It does get warm and this job isn’t for everybody, but it’s not as bad as people would normally think.

The Ubyssey: Mascots can be intimidating to some people, so I’m wondering, what percentage of people do you think are scared of Thunder?

Thunder: That’s a good one. If I were to maybe estimate a number, I think maybe around 20 per cent of kids get scared.

The Ubyssey: Can you rank your favourite games to go to?

Thunder: My favourite game to go to of all time is the Homecoming game. It is awesome. We get to march from the Nest all the way to the football stadium, and that trek is really fun. My next favourite game would be the Winter Classic. That’s another huge event. I love interacting with Birb, who always comes to the Winter Classic [and] a mascot race always happens at the Winter Classic. So that’s always a classic that I look forward to. Next favourite game of [the] regular games would be volleyball. It’s a great pace, you can get a nice rhythm going.

The Ubyssey: What is your most embarrassing Thunderbird moment?

Thunder: My most embarrassing Thunderbird moment has to be when I tripped on the stairs and the whole crowd [went] ‘oo’ and you can just feel it in your gut.

The Ubyssey: Do you think that you’re going to continue to be Thunder until you graduate? Do you think you’ll be a mascot after you graduate?

Thunder: We’ll see where the path takes me … I don’t think I would turn down any opportunities that came in my way, but I don’t think I would actively seek it out. U

words by Saumya Kamra & Lauren Kasowski illustrations by Abbie Lee

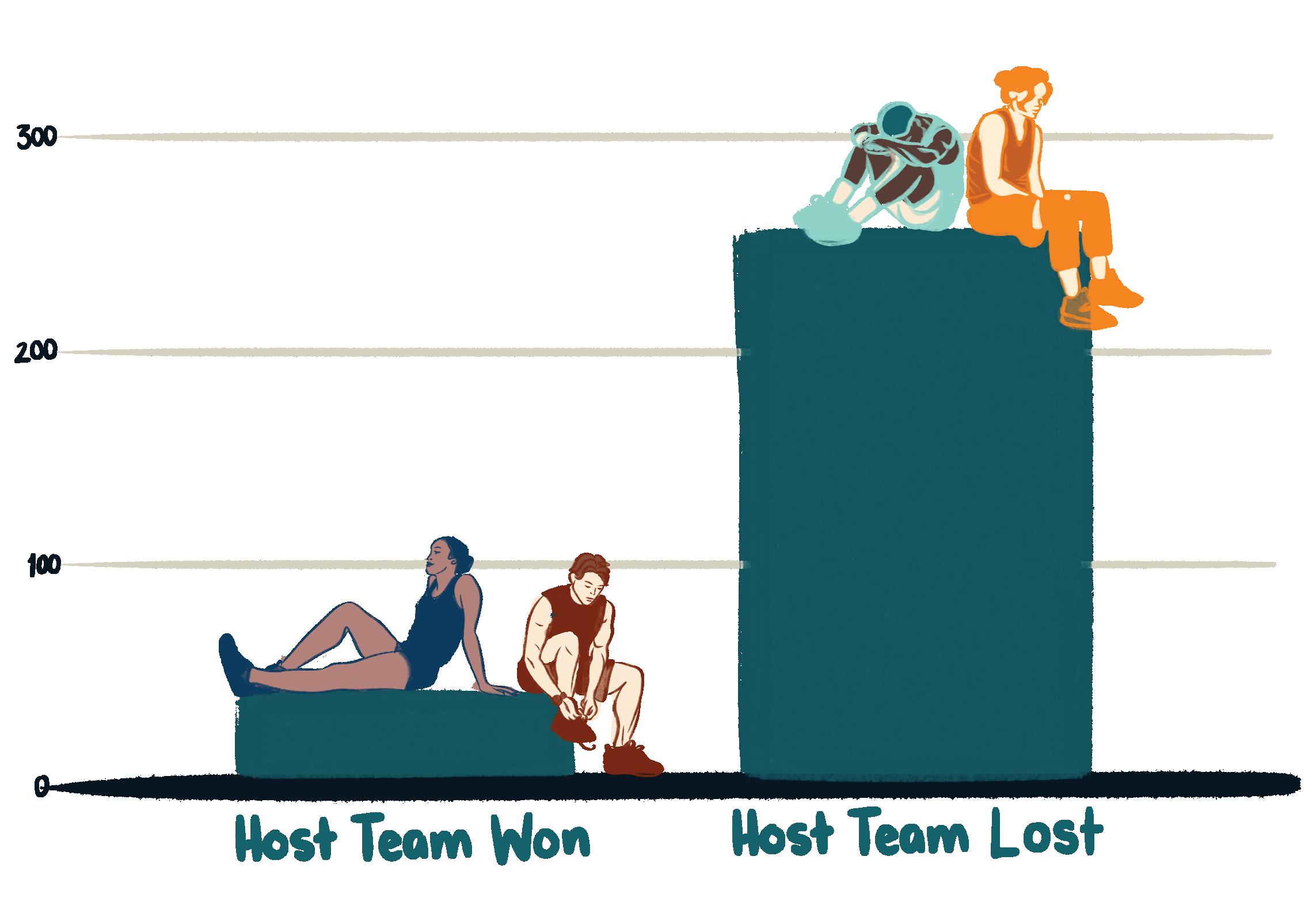

Whether you’re defending your house or entering enemy territory, athletes — and fans — are very protective of where they play. Because of this, many sports can have a home-court advantage — where a team does better in home games than away ones.

But what role does playing home or away actually have in winning games? And does it actually help when it matters the most?

For some sports in U Sports — like volleyball, basketball and soccer — the university hosting the national championship gets an automatic spot in the tournament. Even if they place last in conference play, they still get a shot at the national title.

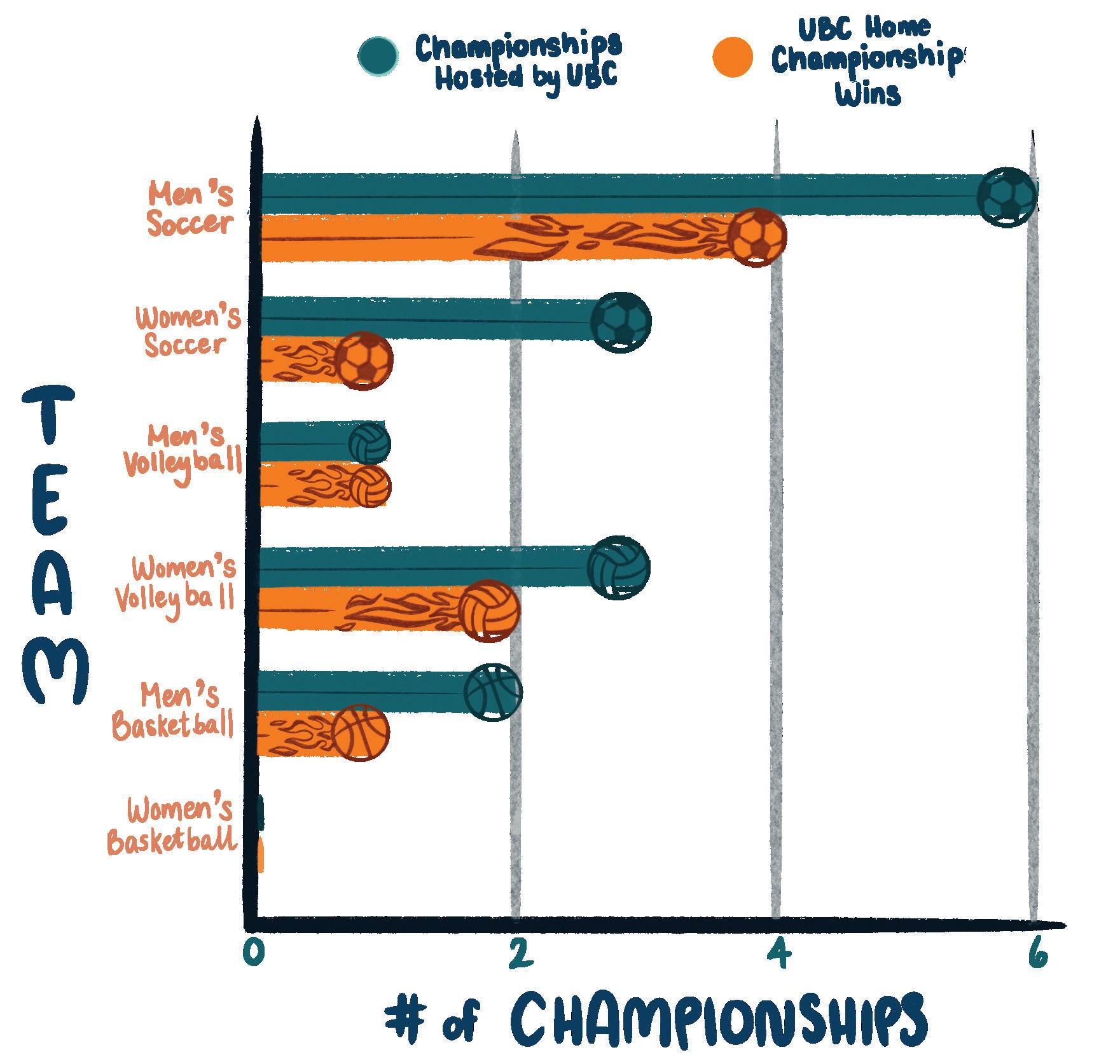

The Ubyssey broke down some of the data of every men’s and women’s basketball, volleyball and soccer championship until the 2023/24 season to see if the home-court advantage exists.

By and large, the data says it doesn’t.

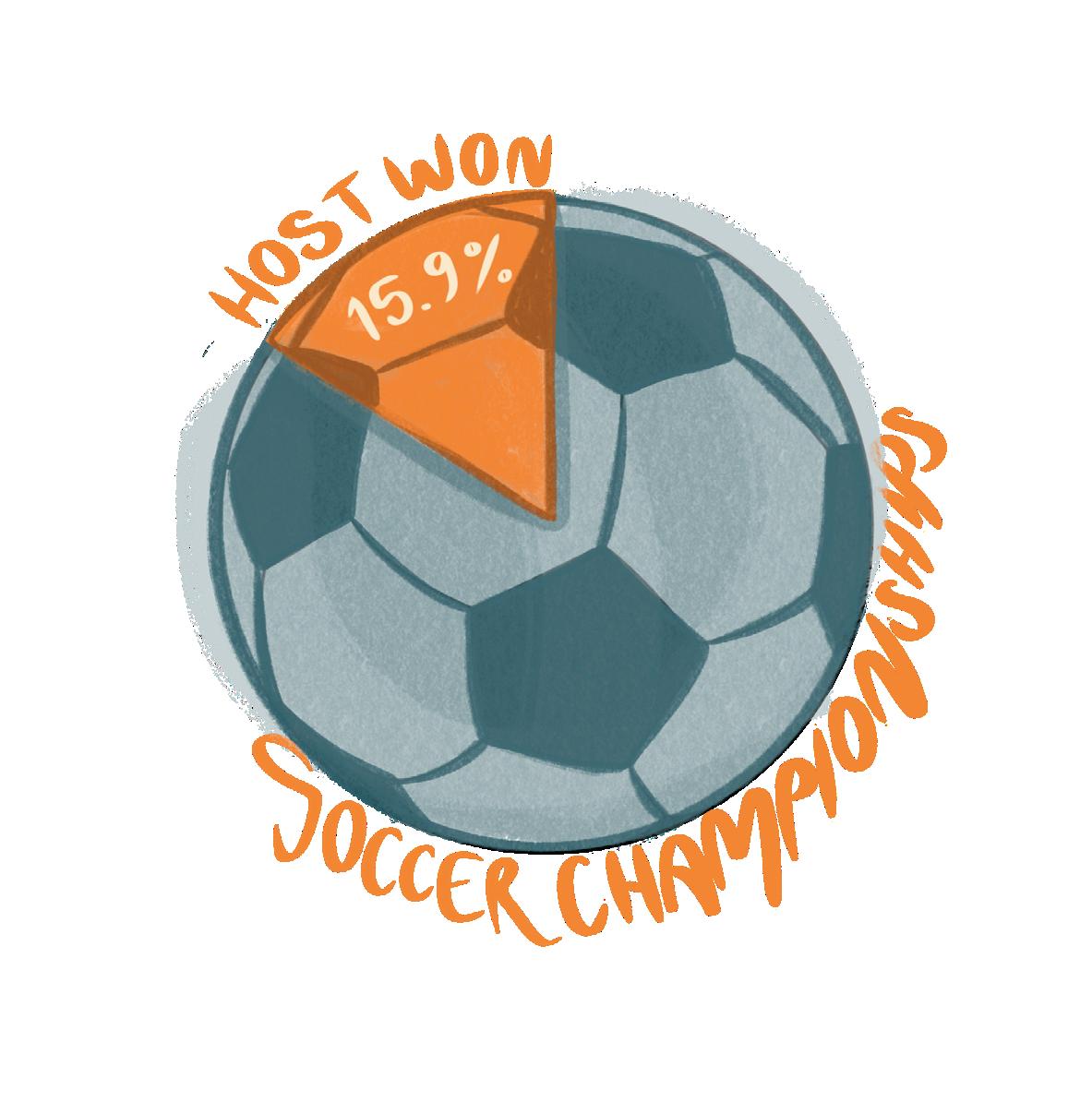

Across the 6 championship tournaments, only 40 out of 296 hosting teams have captured the gold medal — which works out to 13.5 per cent.

Nearly half of those have occurred in the past 20 years. Prior to 2005, host teams across the 3 sports won 11.83 per cent of the time. Post2005, that statistic is up to 16.36 per

words by Lauren Kasowski illustrations by Abbie Lee

cent. However, soccer strongly pulls this statistic, with over 25 per cent of championships being won by the hosts. Both the basketball and volleyball leagues have only had one host win in the past 10 years (Laval men’s basketball in 2024 and UBC women’s volleyball in 2023).

Soccer additionally has the highest proportion of host-won championships, at 15.9 per cent of hosts winning, then volleyball at 13.5 and lastly basketball at only 7.4.

However, soccer championships only started in 1985 and 1987 for men and women respectively, while basketball and volleyball have been occurring since the late ‘60s and early ‘70s. The over 15-year gap in data could explain why soccer seems to benefit from this home-court advantage.

There is a breakdown by gender as well. Men’s host teams have won 14.84 per cent of championships

while women’s host teams sit at 12.06 per cent.

When broken down by sport, male soccer and basketball teams have done better than their female counterparts by upwards of 10 per cent, but women’s volleyball have outcompeted the men by roughly 6 per cent.

The familiarity of a home court might not be the only thing going for a team either — their season performance also plays a role.

Host spots, or berths, are announced anywhere from two to four years in advance by U Sports. Rosters also turn over every year, never guaranteeing the team’s best year will be the year they have an automatic spot.

UBC particularly has had good luck when hosting — 60 per cent (9/15) of UBC-hosted championships have resulted in national banners. Further, in both sports where

UBC has the highest percentage of winning championships on home turf — men’s soccer and women’s volleyball — UBC also holds the highest number of total championships.

A 2024 study on the NBA found that more successful teams had a higher home win percentage over teams lower in the standings, citing psychological and logistical benefits to being on a familiar court.

Prior to the 1994 men’s soccer championships, UBC was already in a very good position to win. They had a 9–0–1 regular season record and won the conference with a 5–1 win over the University of Alberta. Two of the three top conference goal scorers were from UBC, and T-Bird goalie Pat Onstad had a stellar year with zero goals against. While they played on home turf, the result would have been in UBC’s favour anywhere else too.

However, that isn’t always the

case. In 2023, the UBC women’s volleyball team was knocked out in the opening Canada West playoff round, placing eighth-seed by their host berth alone. They were not favoured to win.

But they managed to sneak a win in the quarterfinals, then the semifinals and the final, for a national championship no one really saw coming. For some players, playing on home court really was the difference-maker.

“The crowd here was amazing,” said Brynn Pasin after the team’s quarterfinal upset. “Thankfully we’re on home turf — that helped so much.”

At the end of the day, home court is just one of many variables that go into how a team performs on a certain day —and if history is indication, it’s neither here nor there. U — With files from Tanay Mahendru

On Sunday afternoon at the Doug Mitchell Thunderbird Sports Centre, the University of Saskatchewan Huskies pulled off an 85–66 revenge win over Carleton University Ravens to win their first national title since 2020.

In a thrilling rematch of last year’s national championship, when Saskatchewan lost 70–67 to Carleton, the Huskies dominated defensively and created problems for the Ravens. Ultimately, Carleton couldn’t connect at the net while Saskatchewan was over 40 per cent from everywhere.

“Our team was looking forward to this game,” said Saskatchewan head coach Lisa Thomaidis. “They wanted to get back out and prove that you know last year was not our best effort.”

The Ravens started the first quarter, holding pressure to grab offensive boards leading to a Tatyanna Burke layup. Logan Reider made a big impact for the Huskies in the first quarter on both ends of the court. Kyana-Jade Poulin responded with a three-pointer but Carleton still trailed until Teresa Donato gave the Ravens their first lead, 12–11, with an explosive layup. The Huskies regained the lead with two three-point plays and sharp defence. To end the first quarter, Gage Grassick made two free throws, extending the Huskies’ lead to 24–16.

Saskatchewan kept their momentum in the second as Téa DeMong made a strong drive to the net. The Ravens, fighting the Huskies’ defensive pressure, made two strong offensive plays, closing the gap to 27–22. The Huskies immediately re gained control with two consec utive Grassick three-pointers. In the last minute, Grassick drove into the paint and made a quick

pass to Courtney Primeau under the net to score, putting the Huskies up 45–31 before halftime.

In the third quarter, the Huskies only improved as Grassick lit it up behind the arc, but Donato kept responding with her own three-pointers. Grassick was all over the court, making a steal before passing to DeMong, who flew down the court for the layup making the score 58–40. The Ravens capitalized off a Huskies’ offensive foul but Saskatchewan held onto their 15-point lead, ending the third, 63–48.

Donato made a big jumpshot to start the last quarter, the Ravens now trailing 63–50. Fighting the shot clock, Grassick banked a jumper in an offensive clinic. The Ravens fought to the end, but the Huskies wouldn’t budge as Grassick made another three-pointer, strengthening their lead to 76–62. In the last two minutes, Grassick headed to the line three times — earning six points — as the Saskatchewan fans in the stands chanted “MVP.”

The Huskies held the ball to end the game with a blowout 85–66 win, foiling Carleton’s chances to be three-peat national champions.

“They’re the team that lots of people hold themselves as a standard to,” said Grassick. “To come out to compete in the way we did, I’m just so unbelievably proud of my teammates.”

Donato led the Ravens’ offence with 24 points. Grassick, tournament MVP, earned that honour for the Huskies with a career-high 35 points, 7 rebounds and 7 assists.

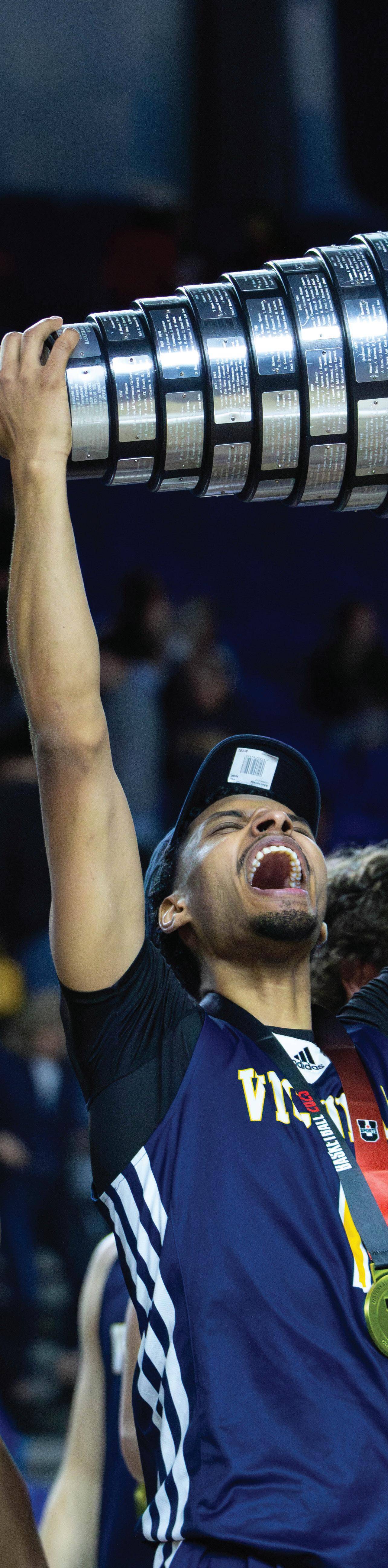

On Sunday afternoon at Doug Mitchell Thunderbird Sports Centre, the University of Calgary Dinos and University of Victoria Vikes battled for gold in the final match of the U Sports men’s basketball championship, with the Vikes securing a dominant 82–53 victory.

A high stakes game, both teams opened with high energy and intensity in their quest for the title. UVic was looking to take home its first championship since 1997, while all eyes were on the Dino’s U Sports Player of the Year Nate Petrone. Calgary opened with a striking play, driving straight to the ring. However, it was the Vikes who took control of the game with their unmatched offensive and defensive play, outscoring the Dinos every single quarter.

Shadynn Smid opened the scoring for the Vikes but all players showed initiative, taking on various offensive roles for an all-round effort. Renoldo Robinson facilitated the attack, Sam Maillet brought the physicality and Ethan Boag and Smid were clinical in the paint.

“We played together, we played for each other,” said Maillet after the game.

On the other hand, Calgary was a one-man show, relying on Petrone for points. But he was held back, being heavily marked and often double teamed in the first quarter. Blocked, the Dinos trailed 10–2 in the first five minutes. The Vikes controlled the game’s pace and had Calgary backpedalling defensively, especially during the transition. Beckett Johnson eventually

The second quarter was similar with the Vikes outplaying the Dinos. Robinson opened the scoring and combined with Boag to put up a collective 20 points in the first half. The Vikes increasingly made chances in tight spots, using great communication and physicality to score. The Dinos picked up the pace a little, getting points from Alan Spoonhunter and Martynas Sabaliauskas. However, they continued to slack on the offensive rebounds 11–2, leading to 14 UVic fastbreak points in the first half. At the half, the Vikes led 40–23.

The Dinos attempted to regain their composure in the third quarter with Petrone and Spoonhunter earning a few more points. Calgary showed a more well-rounded effort but Victoria kept the offensive pace, maintaining their lead and frazzling the Dinos, who shot only a 27.3 field goal percentage all game. The Dinos improved on offensive rebounds this quarter, scoring a few second chance points, but their same weaknesses persisted and they were down 65–42 after three.

Calgary had little hope for a comeback in the final quarter as the Vikes ran away with the game, dunking over their spaced-out, tired defence. The Dinos committed a few more turnovers, which the Vikes took advantage of. The game ended 82–53, and the Vikes clinched the gold medal, their ninth in program history.

“It’s pretty amazing, we’ve dreamt of this,” said Vikes head coach Murphy Burnatowski. “The group worked so hard all year and I’m just really, really proud of them.” U

words by Maia Cesario

words by Rhea Krishna

photos by Danielle Simon

photos by Danielle Simon

On Sunday, UBC’s women’s basketball team suffered a heartbreaking loss to the University of Ottawa Gee-Gees, falling 68–61 in an intense bronze medal match at War Memorial Gym.

Both teams entered the game wanting redemption after suffering blowout defeats — by over 20 points — in the semifinals.

Ottawa won the tip-off and started scoring quickly, with the Gee-Gees’ Alissa Provo scoring a nice three-pointer on their second possession. The GeeGees’ first three scores came from beyond the arc, making an impressive four of six triple attempts in the first quarter.

The Thunderbirds kept pace at first; Jessica Clarke hit two free throws and a layup, then Emily Martindale added another layup to tie the game at six. However, after some back-andforth, Ottawa gained momentum, going on an 18–2 run. The ‘Birds added three more points from free throws, narrowing the gap in the final minute, but they still went into the second with a 26–11 deficit.

After last night’s blowout loss, it seemed like history was repeating itself for UBC. But despite the intimidating deficit,

the ‘Birds kept pushing, not allowing Ottawa’s lead to grow beyond 16. Then, as the second period expired, Sara Toneguzzi scored the only successful ‘Birds three-pointer of the half, narrowing the gap to 40–29 and gaining much-needed traction.

Clarke quickly built off that momentum in the third quarter, making an and-one play. UBC’s

defence intensified, creating turnovers and limiting baskets for a chance to catch up. Steadily, the gap narrowed. Olivia Weekes tallied two free throws, Keira Daly scored a layup, then Clarke made a jump shot and layup to bring the score to 42–40. Now, the seemingly insurmountable deficit was only a shot away.

Ottawa grabbed 2 more points, but Daly responded with a triple to keep the score tight, 44–43. After some back-andforth, with seconds left in the third, Mona Berlitz lofted up a shot from beyond the top of the key. The crowd erupted in cheers as the scoreboard changed to 50–48, giving UBC its first lead of the game.

The UBC Thunderbirds men’s basketball team took on the Concordia University Stingers in a heated consolation final matchup on Saturday afternoon at War Memorial Gym, where the Stingers emerged victorious with an 87–80 win.

While there was no medal on the line, both the Thunderbirds and the Stingers showed a tremendous amount of grit and heart, battling not just for the win, but for pride.

The Stingers opened up the scoring in the first quarter after Jaheem Joseph cashed in a midrange jumper. UBC’s Brendan Sullivan answered with a contested high-glass layup, setting the tone for this back-and-forth matchup.

Concordia’s Alec Phaneuf got off to a hot start, building on the three-point shooting clinic he had put on all tournament. Phaneuf started the game shooting 5 for 5 from three, with 19 points in the first quarter alone.

UBC found success from beyond the arc as well, with 18 of their 23 first quarter points coming from three-pointers. Both teams were shooting above 50 per cent from the three as the quarter came to a

The final quarter was extremely physical as the two teams exchanged scores. Down 56–55 with only 3 minutes left, Daly nabbed the lead back with a stellar three-pointer. But it would be the last time UBC led as Ottawa responded with a 10-point scoring streak, widening the gap to 66–58 despite the T-Birds’ best efforts.

In the final minute, Daly scored a three and UBC created a turnover — but it wasn’t enough to overcome Ottawa’s final quarter push. The Thunderbirds finished fourth after the 68–61 loss, but UBC head coach Isabel Ormond was proud of her team’s performance.

“Nobody wants the outcome of this game, but all year and even for the last two seasons that I’ve been here, this team won’t quit,” she said. “They’re going to fight and push and bring energy, and you can’t help but just be absolutely so proud of that.”

This marks UBC’s best postseason finish since 2015’s third place.

“I’m not surprised we’re here,” said Ormond. “We earned it. We work on it every day in practice and, again, we’ll be back.” U

close, with Concordia leading 28–23.

The second quarter saw both teams continue to feed their sharpshooters, running fourout, one-in offensive schemes to generate open looks. Joseph started to find his rhythm from the three for Concordia, while T-Bird Gus Goerzen got hot as well, shooting three for three from beyond the arc in the second quarter. They both went into the half shooting above 40 per cent

from the field, with Concordia maintaining their slim lead, 46–44.

Victor Radocaj opened up the scoring for UBC after the half, with a reverse layup to tie the game. Both teams started to cool off from three, forcing them to rely on their slashing abilities. UBC tried to capitalize on this with their advantage in height and length, but Concordia held strong on defence, ending the third quarter up 60–59.

Both teams had everything

to play for in the fourth, with UBC looking to end the tournament in their hometown on a high note.

UBC fifth-year forward Fareed Shittu opened his final quarter in blue and gold with three back-to-back layups, giving UBC momentum. However, Concordia’s Owen Soontjens and Junior Mercy responded with three back-toback three-pointers, putting the Stingers back in the driver’s seat.

Phaneuf and Soontjens found their shot again near the end of the fourth, hitting two crucial three-pointers to put the game out of reach, securing the upset 87–80 win for the eighth-seeded Stingers. With showcases of heart and dedication throughout the tournament, Phaneuf thought they demonstrated why they belonged.

“I think we showed the ‘Q’ needs some respect,” he said. “We’re a good conference and we can truly play against these guys.”

Phaneuf ended with 31 points, making it the highest scoring performance of the tournament up to this point.

“It’s just energy and hard work. You saw at the end — our chemistry… the love we have in the team just fuels everything. The guys are truly happy when we make shots,” said Phaneuf. With the win, Concordia ends their tournament on a high note, securing fifth-place and taking down UBC on their home turf. After a disappointing tournament, winning only one game as the third seed, the T-Birds will have to re-group and turn their attention to next season. U

words by Annaliese Gumboc photos by Saumya Kamra

words by Fred Knowles

photos by Saumya Kamra

photos by Navya Chadha, Saumya Kamra & Danielle Simon