UBC community members began an encampment on April 29 on MacInnes Field in solidarity with Palestine.

Signs which read “Long Live Palestine,” and “Turtle Island to Palestine: Occupation is a Crime” were attached to lined fences put up around the field, which was filled with tents and students in keffiyehs.

In an Instagram post, organizers People’s University UBC listed their demands for UBC. These include divesting from companies complicit in Palestinian human rights abuses, boycotting Israeli universities and institutions and publicly condemning what organizers and human rights experts call a genocide in Gaza.

According to a report issued by a United Nations-appointed independent expert, there are “reasonable grounds” to believe Israel is committing genocide in Gaza.

At the time, Capuchin, a community member involved in the encampment, said the encampment’s focus is to “recentre attention toward the Palestinian cause and toward the genocide in Gaza.”

Matthew Ramsey, acting senior director of UBC Media Relations, wrote in a statement to The Ubyssey that UBC understands “some in our community want to protest the violence and war they see unfolding.”

Ramsey also wrote any actions that create “a health and safety risk,

“Community

sity to recognise and address the ongoing and intensifying genocide of the Palestinian people,” wrote People’s University UBC in a state -

impede the university community … from learning, research, work and other activities on campus or damage university property” will be investigated. UBC did not take any action to remove the encampment.

In 2022, UBC rejected calls from student groups such as the AMS, Students for Palestinian Human Rights and the UBC Social Justice Centre to divest from companies complicit in Palestinian human rights violations and endorse the boycott, divest, sanction (BDS) movement. In December 2023, UBC President Benoit-Antoine Bacon reaffirmed UBC does not support BDS.

Capuchin said “We’re staying here until UBC recognizes our demands.”

Bacon wrote in a UBC Broadcast message that UBC’s focus is on ensuring the community’s safety amid the ongoing encampment, and that UBC’s endowment fund “does not directly own any stocks in the companies identified by the movement.” Instead, “capital is held in pooled funds and managed by external investment managers.”

The “identified companies,” according to Bacon, account

for about 0.28 per cent of the endowment fund. That is around $7.8 million of UBC’s $2.8 billion endowment.

Bacon also said UBC is a signatory of the Principles for Responsible Investment, a United Nations-supported framework of principles that set a responsible investing standard, and that the university’s investment managers adjust their investment strategies based on environ -

mental, social and governance principles.

“We reject the administration’s attempts to deny their complicity in the ongoing genocide of Palestinians by the terror state of Israel,” wrote Zainab, an encampment spokesperson, in a statement to The Ubyssey.

Zainab wrote that the encampment’s organizers are not interested in negotiating with UBC — “Our demands are clear.”

ment to TheUbyssey.

Ramsey wrote “During this period, there has been theft, abuse of university property, erection of barricades, installation of cooking and toilet facilities on UBC property and the removal and possible theft of a Canadian flag from a UBC flag pole.”

In an Instagram post, People’s University UBC said it did not install cooking facilities or engage in the possible theft of a Canadian flag.

“Protesters have clearly indicated they intend to continue escalating with such disruptive actions,” wrote Ramsey.

People’s University UBC also said the protest was peaceful.

After several hours, protesters left the Bookstore upon receiving instruction to vacate by RCMP and Campus Security.

On May 13 at about 3:30 p.m., around 20 protestors held a silent

vigil in the Robert H. Lee Alumni Centre to commemorate Rashid Abu Arreh, a 16-year-old killed by the Israeli army in 2021.

Taped to the windows was a statement from the organizers which said the sit-in was to “honour the mothers of Gaza whose children have been murdered by Israel in its genocide.”

The group sat in a circle inside the Alumni Centre’s foyer with pictures of people killed by the Israeli army taped to the ground, a projector displaying names on a screen and signs taped to the windows reading “Honour All Palestinian Mothers” and “Stop Genocide.”

Other protestors who couldn’t enter the building sat outside.

Campus Security and University RCMP were present and stationed at some exits. Doors to the Alumni Centre were locked from the outside.

Both Campus Security and RCMP denied TheUbyssey’s repeated requests to enter the building and did not explain the restriction on journalists’ ability to report on the situation.

In a statement to TheUbyssey about the vigil, Ramsey wrote “RCMP were called to disperse the group, which left the building only after being informed of the potential for arrest.”

“People held a silent vigil with images of martyrs but were promptly kicked out and met with excessive police presence,” wrote People’s University UBC in a press release.

The vigil lasted around an hour with protestors leaving at 4:40 p.m., after a second warning from RCMP that those who refused to leave would be charged with mischief under section 430 of the Criminal Code, according to video obtained by TheUbyssey.

Also on May 15, protestors held a vigil and read statements at the Senate meeting calling on UBC to cut ties with Israeli universities.

The meeting, which was originally planned to be held in the Life Sciences Building, was moved online and pushed back 30 minutes to 6:30 p.m. without any public announcement.

At the start of the meeting, which was live-streamed over Facebook, President Bacon said there was a “safety plan” for the meeting, but because “safety” was called to Koerner Library, the Senate was “no longer confident” the meeting could proceed in-person.

Outside the entrance to the Life Sciences Building, protestors set up a vigil with photos of people killed by the Israeli army and Palestinian flags placed into the ground. The group was protesting UBC’s partnerships with Israeli universities such as Hebrew University, Tel Aviv University and Technion-Israel Institute of

Technology.

The Senate is the governing body which decides and approves all academic matters including academic university partnerships at UBC.

Student Senate Caucus CoChair Jasper Lorien said that they, along with Co-Chair Kareem Hassib and 16 other senators, have submitted a letter to call a special Senate meeting to discuss “the ongoing violence in Israel and Palestine and discuss a motion regarding suspending academic ties with Israeli government entities, including public universities.”

Clerk of Senate Chris Eaton said they would be reviewing the letter “to ensure that it meets the requirements.” If it does, Eaton said they’d “organize a special meeting to discuss the proposed resolution.” Whether a special meeting is happening has yet to be announced.

At the end of the meeting, two protestors read statements to the

Bacon released a statement responding to each of the Palestinian solidarity encampment’s demands on May 16.

In the statement, Bacon reiterated his May 7 statement on divestment, which is that UBC’s endowment fund “does not directly own any stocks in the companies identified by the

Around 50 protestors affiliated with the Palestinian solidarity encampment occupied the seventh floor of Koerner Library, calling on UBC to release a statement within 24 hours responding to the encampment’s demands.

Around 4 p.m., protesters lined up along the stairwell and gathered outside the UBC President’s Office with Palestinian flags, banners, a speaker and a microphone.

TheUbyssey had one reporter inside the library. Campus Security did not allow additional presspass-bearing Ubyssey reporters to enter.

At 5:30 p.m., a group of RCMP officers and two Metro Vancouver Transit Police officers spoke to protest organizers inside and said people who did not leave the building would be arrested. Some protesters vacated the space and began demonstrating outside Koerner Library — 17 community members stayed inside.

Outside, protestors chanted, drew on the building and sidewalk with chalk and waved Palestinian

flags from the building’s roof.

Protestors were asked to leave by RCMP officers who said library management had closed Koerner Library and protestors who stayed would be charged under section 430 of the Criminal Code for mischief.

Around 6:40 p.m., protesters spoke to Campus Security Director Sam Stephens about their demands. Stephens said he was not authorized to deliver a public address on the UBC President’s behalf but could deliver the protestors’ request directly to the president. Protesters said that once Bacon provided a public response that directly addressed all of their demands, they would leave the library.

At 7:07 p.m., Stephens returned with a letter confirming he would take the protestors’ list of demands and request for a response to Bacon. He also requested protestors leave the library.

“This is your final warning. Library management has closed the library, you’ve been asked to leave

Senate.

The first speaker said UBC regrets complicity in the genocide of Indigenous peoples, but has not said the same for the genocide in Palestine.

“There is no Truth and Reconciliation day with no Nakba day … shame on you all,” said the first speaker.

The second speaker spoke about their family’s history of displacement.

“Remember this in 400 years, when settlers in an unrecognizable Palestine pat themselves on the back for performing land acknowledgments and vigils commemorating our missing and murdered men, women and children,” said the second speaker.

Bacon thanked both speakers. He said “the violence in Palestine is awful and has been hard to watch for everyone” and “the history is also extremely complex and evokes complex and difficult emotions.”

movement.”

Bacon also wrote that UBC has a responsibility to ensure everyone is safe on campus which, at times, has required the support of law enforcement.

“On the issue of campus safety and the role of police in protests, compared to what has been seen elsewhere, UBC has been

measured and restrained in our response to the protests, and our aim is to continue to be,” wrote Bacon.

Protestors at other universities like the University of Alberta and University of Calgary have faced arrests and police confrontation. As of May 21, no arrests regarding the UBC encampment have occurred.

On boycotting Israeli universities, Bacon wrote that the UBC Vancouver and Okanagan Senate “make final decisions pertaining to academic matters.”

On condemning the genocide in Gaza, Bacon wrote “universities have been increasingly asked by communities to take positions on events through institutional

under section 430 of the Criminal Code of Canada,” said an officer.

Around 7:33 p.m., UBC VP Students Ainsley Carry spoke with protestors. Protesters asked Carry if he was getting UBC to implement their demands. He said he was committed to starting a discussion. Carry also expressed his “preference” that demonstrators vacate the building.

“We are now 222 days into a genocide. I don’t know how much more discussing anybody of us has in us. I don’t know how to discuss and convince the university to see Palestinians as human,” a protester said.

Around 8 p.m., protesters escorted by Campus Security left Koerner Library chanting “Disclose. Divest. We will not stop. We will not rest.”

As protestors dispersed from Koerner Library, an organizer spoke into the protest’s microphone.

“From the bottom of my heart, fuck this university and fuck every last administrator.”

statements.”

“However, these world crises are complex and by definition evoke different emotions and can be interpreted in very different ways by different members of the community.” Bacon also wrote that the university “cannot presume to speak for everyone in matters external to its own operations” and students and professors will hold a “broad array of views.”

“University neutrality is not synonymous with moral relativism,” wrote Bacon. “All universities, by their very nature, stand strong against all forms of violence, exploitation, intimidation, discrimination, harassment or any other form of harm directed at individuals

or groups on the basis of race, gender, religion, sexual orientation or any other characteristic or label.”

Bacon also said UBC wants “to engage in discussions on these issues with UBC student representatives of the protest encampment, ” with Carry serving as the lead liaison for these discussions.

Carry attended the encampment’s rally on April 29, the Emily Carr University graduation protest on May 8 and spoke to students at the May 15 President’s Office sit-in.

“As such, like the rest of the world, we hope for a ceasefire and a lasting peaceful resolution in the Middle East,” wrote Bacon. U

Dr. Jennifer Gagnon was terrified the first time they brought their service dog to work.

“I was actually really anxious … I wanted him to do well, but I also needed to do my job well,” said Gagnon.

“There was that tension of how can I support the training needs of my dog in a classroom setting and also maintain my own identity as an instructor and support all of my students.”

As a lecturer in the School of Journalism, Writing, and Media, Gagnon continues to work on finding the perfect balance between training their service dog Ziggy and teaching writing skills to undergraduate students.

“One of those other challenges is communicating effectively with my students to be able to say, ‘I have a service animal, I don’t want it to surprise you, here’s what you can expect.’”

But outside their classroom, UBC’s policies on accessibility, inclusivity and service animals remain a significant barrier to Gagnon and other disabled students, faculty and staff.

When Gagnon first started at UBC as a sessional lecturer in 2013, their contract structure did not provide any extended medical benefits or regular coverage over the summer months.

The UBC Faculty Association Agreement for 2022–25 indicates that sessional lecturers who are teaching less than a 50 per cent course load must apply for extended medical benefits and dental coverage.

On top of that, many sessional lecturers often take on additional jobs to access needed benefits and subsidize their teaching salary.

“The rank where you’re most likely to see disabled faculty is among contract faculty — those are sessional adjuncts and lecturers,” said Gagnon.

“Making it so that your most vulnerable faculty members are on precarious contracts [and] are also the ones most likely to lose access to extended medical benefits creates additional burdens for disabled people to be included at the university as professors.”

Gagnon also noted the lack of disability representation within UBC management and human resources. In UBC’s 2023 Employment Equity Interim Report, data showed that 7 per cent of middle management and managers identified as disabled at UBC Vancouver and 14 per cent at UBC Okanagan.

“Accommodations are often decided by people in positions of power … Disabled people, who are not only the experts in their own condition [and] their own bodies, are not seen as experts in … [what] best supports their access needs,” said Gagnon.

When there is a lack of representation in management, accommodation policies also falter. For Gagnon, one of the biggest barriers is the accommodation and remote work policy for faculty.

“There is still no formal accommodations policy for employees at UBC. That’s unacceptable,” said Gagnon.

For example, remote work can be requested and accessed by UBC staff without medical or disability documentation, but faculty are excluded.

“When I was trying, as an individual, to navigate [the] accommodations process, I was often made to feel that I was the problem — that the needs of my body were a problem to be managed by the university.”

For disabled students, inability to access service dog certifications and accommodations is a growing issue. Gagnon said UBC Housing does not recognize or allow students in residence to train their service dogs, as it only permits

certified service dog teams, service dogs trained by an accredited school and certified by the Guide Dog and Service Act of British Columbia.

“There is a huge shortage of service dogs in BC, and accredited schools like PADS can’t meet the volume of need. For example, I decided to do owner training because waitlists for a service dog from accredited schools in BC were full, or over 5 years for a wait, or couldn’t provide me with a dog to suit both mobility and PTSD/mental health access needs,” Gagnon wrote in a follow-up statement to The Ubyssey

“It’s a policy I hope UBC changes to recognize that in-training dogs and owner trained service dogs are legitimate and do have a right of access just like dogs trained by an accredited service dog school in BC,” they wrote.

Although these policies remain tough barriers for those with disabilities at UBC, there are ways to support and advocate for the community.

At Campus Canines, a UBC club in collaboration with PADS Dogs, student service dog trainers, raisers, sitters and general members are provided an opportunity to learn about service animals and disability justice.

To become a raiser, a member must complete regular onboarding processes and online training modules. Afterwards, raisers become responsible for all training and daily activities of their dog, including attending weekly puppy classes and bringing their dogs to lectures or on grocery runs. For 1.5–2 years, raisers and their dogs are attached at the hip 24/7.

“We bring our puppies everywhere with us,” said Adele Lo, a third-year dietetics student and director of membership at Campus Canines. “They live with us … We can take them on buses, to grocery stores — anywhere we go because they have full legal public access as service dogs in training.”

If a raiser can’t take their dog somewhere, they rely on the help of sitters, who are short-term handlers. When the dog is ready for advanced training, they begin the specialization process.

“There [are] four jobs that they can do, which are mobility dogs, PTSD dogs, hearing dogs and facility dogs. So whichever they’re most suited to, the trainers will put them in that stream and start teaching them their tasks for when they work,” said Sophie Pantel, a third-year neuroscience student and raiser.

Apart from raising future service dogs, Campus Canines also works on disability awareness and advocacy for PADS within the UBC community. They’ve hosted

engagement events with different clubs and student organizations, including collaborations with undergraduate societies and UBC sports teams.

Gagnon is also involved in disability justice and advocacy, having founded the Disability Affinity Group (DAG) to “create [a] community of care.”

The DAG includes faculty, staff and students working to advocate for the disabled community. Currently, one of their biggest goals is to establish a disability task force.

“Disability is the only historically persistently and systemically marginalized group at UBC that has not had a task force or been meaningfully included in things like the strategic plan and the new strategic equity and anti-racism framework,” said Gagnon.

Looking forward, Gagnon hopes to see UBC begin prioritizing inclusive and accessible design for both physical environment and policies and practices.

“When we accommodate, it means we’re trying to do a retrofit, we’re trying to build in access when it’s already inaccessible,” said Gagnon. “When we make [a space] inclusive and accessible from the start, it not only benefits disabled folks, it benefits everybody in the room.”

Gagnon’s service dog is “essential to [their] movement in the world,” and they hope for increased “recognition that service dogs support a lot of people with invisible disabilities.”

They receive comments about how their service dog “[doesn’t] get to be just a dog.” But Gagnon and Ziggy want everyone to know that “no dog parties harder than a service dog off-duty.”

“Yes, they’re still dogs,” Gagnon said. “They’re not perfect robots. And they like to have fun, too.” U

When STEM tutorial YouTube channels were “popping off” in the early 2010s, Uytae Lee wondered how he could address the lack of comprehensive videos dedicated to teaching people about their cities.

“If people can make physics so compelling and interesting, surely we can make transit policy interesting,” said Lee, now a UBC adjunct journalism professor.

Between undergraduate urban studies lectures at Dalhousie University, then-student Lee watched important city planning decisions unfold at various community engagement events. Through these gatherings, Lee noticed the need for representation of marginalized voices that would be most vulnerable to these proposals’ drawbacks.

“I, along with a group of friends of mine, really felt that there should be more accessible content out there around urban planning,” Lee said. “With the belief that getting more diverse people involved in these conversations would make the planning of our cities better.”

If you’re a connoisseur of all things local policy — finding the solution to gentrification, bringing back front yard businesses, considering a non-capitalist approach to housing shortages — you may well have already run into Lee’s work before. He’s the mind behind the YouTube channel About Here. In his corner of the internet, Lee taps into virtually any issue that public buzz is attending to at a given moment.

“People are having interesting lively discussions around cities now, way more than they were before,” Lee said about About Here.

Lee finds inspiration focusing on Vancouver, so you’ll often catch him covering issues surrounding the city’s housing crisis.

In November 2023, a Vancouver survey for Habitat for Humanity found that 53 per cent of renters or homeowners spend more than half of their household income on housing costs. Additionally, 48 per cent of the sample size worried about missing mortgage or rent payments within the next year.

Eighty-four per cent said owning a home in their community is almost impossible.

Videos tackling something as pervasive and complex as housing can be intimidating for creators and consumers alike.

“My approach to not having a complete mental breakdown while doing a story on housing is to really try to find one sliver — one specific question within this housing crisis we have that I think we can answer within one story,” Lee reflected candidly.

Lee suggests these extensive topics are like a sweater — pulling one thread out risks the whole investigation coming undone.

When asked about whether he would be interested in committing to a longer documentary, Lee said such a project would provide a lot of personal satisfaction.

“It’s [about] whether I have the appetite and the mental fortitude to venture down such a path,” Lee

said. “But I think it’d be fun to do. I think given the right amount of resources and time, it’d be very worthwhile doing.”

“If you know anyone that’s willing to fund a trip for me to go to Hong Kong,” Lee hinted, side-eyeing jokingly. “You let me know and we’ll make it happen.”

When the time comes, Lee has a vision to cover Hong Kong’s profitable public transit model.

In About Here’s latest video, Lee weighed in on the limitations of Canada’s regulation of point access block apartments. Within a 12-minute clip, he unpacked something as seemingly trivial as staircases to show that they are a huge barrier to constructing smaller multi-story complexes and maximizing urban sprawl, but with the caveat that they are still controlled for in building codes in the interest of fire safety.

Whether it’s his catchy hooks, the bubbly jazz or lo-fi that underlines his narrations, his dynamic cinematography, stellar delivery of stats and facts or the bite-sized nature of his takes, Lee’s work is uniquely his.

His grounded approach to documentary filmmaking eventually landed him a position with CBC Gem. As a UBC professor, Lee has been co-teaching graduate-level visual journalism alongside Dr. Alfred Hermida, someone he values for embodying “the heart and soul of what journalism is really supposed to be about.”

Nobody has ever interviewed Lee about his role as a professor at UBC. When asked about it, he

laughed and said he needed a moment to collect his thoughts. He ended up answering right away.

“Being able to teach has been such a privilege,” he said. “A lot of the skills I have, the things I do, they’re incredibly self-taught. At this point, it feels intuitive … teaching really forces you to very explicitly and clearly explain how your mind works.”

Through discussion, guiding his students to develop their own taste and vocabulary for what does and does not work in investigative videography is a cornerstone of Lee’s teaching philosophy. His only disclaimer to students every year is that they’re all learning together.

“I feel a lot of impostor syndrome,” Lee chuckled. “I didn’t get into this through either journalism school or videography school. I completely stumbled into this career … and organically developed these skills.”

At UBC, the only way students can get a formal journalism education is through the School of Journalism, Writing, and Media’s master’s of journalism program or the journalism and social change undergraduate minor.

Post-secondary journalism programs across the country are seeing a decline in enrolment and some have fully shut down as the field shifts toward digital media. The journalism industry took a further hit last year with the approval of the Online News Act, intended to be a framework for news outlets to gain fair compen-

sation when their content is made available by dominant social media platforms. This means that small newspapers — like student publications — are now limited in the ways they can convey their work.

With the online accessibility of journalism hanging in the air, and Canada facing a nationwide decrease in full-time journalists, community members are concerned about the future of the Canadian industry.

But Lee isn’t. If anything, he believes the profession is fragmenting. In a rapidly changing global landscape, it seems that there is a hunger more than ever for information, but the easy accessibility of social platforms comes at the cost of being more routinely exposed to misinformation.

“The traditional model of journalism looks very much like the writing’s on the wall,” Lee said. “Advertising dollars to fund journalism … that model seems to be just breaking down more and more, year by year. I do think there are, in the absence of that, other models popping up and what I know for sure is that there is a real appetite more than ever for good stories.”

Lee hypothesizes that news outlets will begin to build their business models around specific types of journalism.

“Once you really understand the type of stories you want to get into, you can work backwards and start to understand why and how you might be able to fund those stories.” U

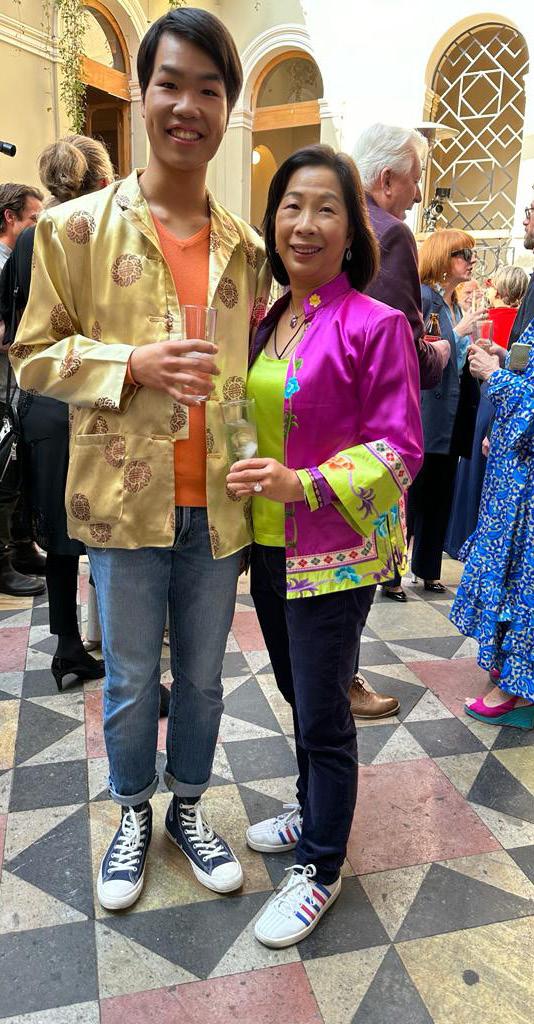

Happy Asian Heritage Month!

This year’s national Asian Heritage Month theme is “Preserving the Past, Embracing the Future: Amplifying Asian Canadian Legacy.” As the month comes to an end, we’ve reflected on how people celebrate and connect to their backgrounds.

Being Asian, especially when growing up or living in the diaspora, can sometimes lead to feeling lost, disconnected from your heritage and the country around you.

What does it mean to be connected to your roots? Does food play a role in connecting you to your culture? Is religion part of it? Do you know your mother tongue, or wish you did?

Whether it’s through music, writing, film or other forms of media, people turn to art to decode these tricky questions.

In this supplement, articles explore how and what the UBC community has created to find their roots. From what we pack when we travel, the food we consume, the music we listen to or the films we make — anything to bring a sense of closeness to a community that can seem so far.

But creating art isn’t just a way to find answers — it connects us to our pasts and allows us to look toward the future. Art recognizes where we began and builds off those cultures to create new ways of experiencing our heritage.

While searching for home — whatever that means to you — we build new communities. And we’re happy you’re part of ours. a

— Elena Massing, Iman Janmohamed & Aisha ChaudhryMy mom is packing a suitcase before her 23-hour flight to Vietnam.

The smooth rolling of its wheels intertwining with the staccato rhythm of duct tape echo through the quiet house.

Her veinous hands organize the items like an engineer assembling the ins and outs of a teleporting machine carrying capsules from this portal: five packs of musky-scented Eagle oil (for senior relatives constantly battling with arthritis) two bulky boxes of chocolate (for the innumerable nieces, nephews, grandnieces, grandnephews and beyond) and plastic-wrapped bottles of lotion and shampoos (for their mothers, sisters and aunties).

The destination label lying neatly on the sleek surface

The stretches of words, diphthongs and diacritics — enigmatic codes carrying the traveller to a bustling street in Saigon, with motorcycles trickling down the narrow lanes alongside which warps the smoky grilled meat from vendors, all within the humid city, pulsating day and night.

I could only look at the machine, now wrapped tight with tape, longing to hop in to reach the other end of the portal. a

UBC alum Daniel Chen’s documentary Remembering Chinese Bachelors attempts to uncover years of complex histories — with the added challenge of minimal surviving documents or sources to contact — in a runtime of just under 15 minutes.

It’s set to run at this year’s Vancouver Short Film Festival, where it’s nominated for Best Student Film and Best Documentary.

During his time at UBC, Chen was an Asian studies and ACAM student. He said this academic experience was how he first got involved in the Remembering Chinese Bachelors project. He was always interested in stories relating to migration and heritage and continues to do similar work at his current position with the City of Burnaby.

The film showcases stories of people referred to as “bachelors” who used to live in Chinatown.

“WE

very laborious jobs earning fairly low income,” said Chen.

Since all of these men had passed away by the time of the film’s creation, Chen and his team based it around conversations with people who had known these men and had memories they were willing to share. It wasn’t easy to make this happen — these memories were often hazy ones from childhood that were quickly disappearing.

“We wanted to document these memories before they’ve all faded away, because these are stories that haven’t been documented in writing as much,” Chen said.

“A way to document these stories [is] to paint the image of what people’s lives [were] like back then — these early Chinese immigrants who built the foundation of the more multicultural society that we have today.”

The film was originally developed for the Chinese

repealed until 1947.

“During that time, practically no Chinese people were able to enter the country. People weren’t able to reunify with their families, which [was] another big reason for these bachelor men to live how they [were], because they couldn’t have their wives [or] their children sent over even if they had the financial means to,”

Chen said.

The exhibit is built around Chinese Immigration (CI) certificates, which were documents used to track Chinese Canadians during this time — a legal pathway for the government to place racially biased restrictions.

“It consists of many oral history stories, where the research team tracked down as many original scans of these CI certificates as they could [then] try to reach out to families to document stories of early Chinese Canadians.”

There are two films be -

words by Elena Massingstories and to really give a voice to the people who have these memories,” said Chen.

Finding these voices was the biggest obstacle of the project. Chen recalled having to fly to Toronto to film interviews — not to mention the time needed to build trust with sources who were more hesitant to resurface traumatic memories.

Chen and his team put extensive thought into editing footage, ensuring they were handling each person’s story with care.

“Chinese people have come into Canada and have contributed to Canadian society at very different stages of the country. I think it’s important to educate, whether it’s newer immigrants [or] people who have lived in Canada their whole lives, about what life was like back then,” Chen said.

-

Through his work, Chen wants to empower people to share their own stories. He noted how the exhibit’s visitor comment box — and his inbox — have seen viewers opening up about their personal connections to the film.

—

The meaning of the word “bachelor” is not what we might usually interpret it as being — it is used as a term to describe working class Chinese men who left their families to move to Canada with hopes of earning a living and building a better future for themselves and for their loved ones back home.

“They wound up in situations where they’re all alone and living in a society where they’re excluded and discriminated against, often working

AWAY.”DANIEL CHEN, REMEMBERING CHINESE BACHELORS DIRECTOR

Canadian Museum’s exhibit

The Paper Trail to the 1923 Chinese Exclusion Act, which opened at the beginning of July 2023 — the 100th anniversary of the passing of Canada’s Chinese Exclusion Act

After the head tax on Chinese immigrants continued to rise to $500, the federal government wanted to find a way to permanently ban Chinese people from entering the country, which was the purpose behind the 1923 Exclusion Act. This act wasn’t

ing screened at the exhibit, including Remembering Chinese Bachelors. The other focuses on life after the Act was repealed, and the discrimination that racialized people continued to face even though they were no longer prevented from coming into Canada by law.

“We figured that film was a great way to add diversity to the medium of content displayed at the museum in the exhibit, and it was also a compelling way to tell their

“A lot of times, people don’t realize that these are very valuable stories. If they don’t tell someone, they would permanently vanish.”

“It doesn’t hurt anyone to learn about these perspectives that have often been overlooked in the history books … It paints a fuller picture of what society was like back then, and I think it allows us to be more appreciative of the equal rights [and] multiculturalism that we cherish and we often take pride in today.”

Remembering Chinese Bachelors is running at the Vancouver Short Film Festival from May 31 – June 2 at the VIFF Centre and until June 9 online. a a

Jazz was never meant to be monothematic — the nature of the genre is experimental and giving. In their freshman album, Raagaverse is taking advantage of this malleability by infusing classical Hindustani vocality with the improv and complexity of jazz to pave their own silky and microtonal rhythm.

Raagaverse is comprised of vocalist Shruti Ramani, bassist Jodi Proznick, keyboardist Noah Franche-Nolan and percussionist Nicholas Bracewell. The Indo-jazz fusion group released their first album Jaya, a tribute to Ramani’s mother, and celebrated it with family, friends and music-goers at the Fox Cabaret on May 9.

“It’s a full circle, this journey that we’ve been on,” Ramani said to the audience at a packed venue. “We’ve created something we’re really proud of that is precious to us.”

It only seemed natural for the Fox to be the chosen venue for the band to, as Ramani said, “cut the ribbon” on their LP. On the very same stage two years ago, the quartet performed for the first time together before the idea of Raagaverse was even conceived.

Raagaverse’s album release show only featured the quartet. But listeners of Jaya can expect a healthy sprinkling of string soundscapes. When Ramani first heard the string quartet they partnered with perform in the studio, she was moved to tears.

“I heard Ella Fitzgerald singing a ballad … There was a whole string section behind her and I got goosebumps. I had tears in my eyes.”

Indian classical music centres melody and rhythm, with most pieces being a solo instrument or voice and some form of percussion. Jazz’s harmony and chords created a textural quality that instantly intrigued Ramani. She quit the classical music program she was in at the time and moved to Canada to study jazz at Capilano University.

Since then, her goal as a composer has been to marry the intricate melodies of Hindustani music with the improvisational nature and dense harmonies of jazz. For Ramani, the two balance each other out, resulting in the sound that is Raagaverse.

“When you look at jazz music, it’s really not complete without improvisation,” Ramani explained. “[In Indian classical music], we improvise within the same scale for hours on end. But

nick, Franche-Nolan and Bracewell. The group’s personalities blend into a unique dynamic — a perfect balance, just like their music.

“We’ve never played the same tune in the same way,” Ramani said glowingly. “That in itself is magical, because we can rewrite the same story to sound different and feel different each time.”

Ramani and Proznick are frequent collaborators outside of Raagaverse — they recently toured together with the Ostara Project, a femme jazz supergroup composed of powerhouses like vocalist Laila Biali and saxophonist Allison Au, who Ramani named as two of her main musical inspirations at the moment.

“I love playing with women or femmes in general. There’s a sense of safety musically and also on a human level. Playing with Jodi, I felt that warmth that I had been missing.”

Ramani also recognized Franche-Nolan as being one of the best keyboardists and composers she’s worked with, the two having a “chemistry, musically, that is unmatched,” that they plan to explore this summer.

“WHEN YOU LOOK AT JAZZ MUSIC, IT’S REALLY NOT COMPLETE WITHOUT IMPROVISATION … THERE’S THE FREEDOM IN JAZZ.”

“I got goosebumps,” Ramani said. “I never thought I would ever have this opportunity to do something like this and have the money to do it and pay everyone well.”

Jaya’s curation was supported by a grant from the Canada Council for the Arts.

Back in October, Ramani performed with UBC Bands for their opening season show Tarot. Although she didn’t necessarily see herself returning to academia after completing her undergrad, she’ll be attending UBC this fall to begin graduate studies in ethnomusicology.

Growing up, Ramani trained in a style of Hindustani music developed thousands of years ago in the city of Agra. She also experimented a bit with contemporary Indian music in languages like Hindi and Tamil.

English is Ramani’s fifth language, and she didn’t get into Western pop, classic rock or other English music until her teenage years — but she recalled how hearing jazz for the first time was a “profound, life-changing experience.”

— SHRUTI RAMANI, RAAGAVERSE VOCALIST

in jazz, you have so many different scales you can borrow from … there’s the freedom in jazz.”

Hindustani music shares that same improvisational pull, but the rules of the scale that constitute the genre reel in the polyphonic and unexplored nature of jazz in a way that methodizes the soundscape into something “ethereal,” what Ramani described as taking “the best of both worlds.”

Ramani has worked with her mentor for over 15 years and is still learning. It was crucial to her to find fellow musicians that could approach this project with a sense of care and an open mind.

“Some of this music that Raagaverse plays is, again, thousands of years old, and from a tradition that is very protected and cherished and celebrated, and also, in some ways, worshipped. It’s not just given out to everyone — the knowledge is only shared with people that show their dedication towards music, so it’s quite protected.”

She found this support in Proz-

The duo will be teaming up to record a jazz album this August. Until then, you can see them live, or buy Jaya now on Bandcamp — as Ramani put it jokingly at the show, this is how “you can support musicians the real way, which is to pay for their music.”

There was something special in the air that Thursday at the Fox. To our left, two friends donning black clothes sipped Heinekens and swayed to the low murmur of the ambient sound as vibrant saris of purple and pink swayed between the high top tables. To our right, the sound of a drink spilling on the ground as someone clumsily greeted friends, laughing and scrambling to mop up the mess with a bartender trailing behind with a dish towel.

You could feel the room exhale. People had let their guard down as soon as they walked in the door.

“It means a lot to us that you are here, you’re celebrating what this band is trying to do, what we’re trying to do together,” Ramani said while looking out to the crowd before the group’s last song of the night.

“[And celebrating] the kind of musical diversity in the landscape that is much needed that makes this whole Vancouver scene much more beautiful, and much more worth being around.” a

words byFiona Sjaus

Ambiguity, silence and the unsaid — for poet-translator and UBC creative writing MFA graduate Yilin Wang, these are themes that can tug at a writer’s inspiration to delve into their craft.

In Wang’s freshly released anthology of contemporary Chinese poetry The Lantern and the Night Moths, it is in famed Chinese poet Fei Ming’s poem “Lantern,” translated by Wang in her series of ars poeticas, where these themes emerge and inform the overarching reflection of Wang’s artistry.

The title of her anthology is a marriage of two poems included in the work: Ming’s “Lantern” and Dai Wangshu’s “Night Moths.”

“I chose this phrase to encapsulate and invite reflection on some of these themes in the book,” said Wang.

The symbolism behind a moth to a flame is a “complex, nuanced relationship” — the death of a moth represents the metamorphosis of its new life. In Chinese culture, they embody the spirits of ancestors.

20th-century China. She carefully chose prose about topics that resonate with contemporary readers.

Despite some of the writers drawing influence from different contexts, due to what Wang described as a “transitional period where people were really experimenting with what poetry could look like,” sinophone readers and bookworms from other diasporas alike will likely still be able to relate to writers’ discussions of the relationship with ancestors, gentrification and urban issues.

As Wang explained her process, she said that the initial research requires careful analysis of the text.

At this stage, she learns about the poet and the times in which the poet lived. This helps contextualize the motivations behind chosen references and allusions — rhetorics that define classical Chinese literature.

“There’s really a lot of attention paid to alluding to other literature and other references,” Wang said.

“THE FISH IS ACTUALLY THE WATER IN FULL BLOOM. / THE LANTERN LIGHT SEEMS TO HAVE WRITTEN A POEM; THEY FEEL LONESOME SINCE I WON’T READ THEM.”

— FEI MING’S “LANTERN”

footnotes and thoughtful personal essays to explain the untranslatable, practical elements that are generously sprinkled into her anthology to mend this gap and contribute to one of her ultimate goals behind The Lantern and the Night Moths — to make contemporary Chinese literature accessible and engaging regardless of readers’ “different levels of knowledge and pre-existing contact with Chinese literature or poetry.”

Some of the book’s commentaries also hint at the systemic underrepresentation and exploitation of many translators in

issue it as a part of the settlement and that they have never had a process for getting permission clearance for translations. And they promised to make one,” Wang laughed.

TheUbyssey could not find any British Museum documents outlining this process since the August 2023 settlement.

In light of the case, the International Federation of Translators (FIT) Standing Committee for Translating for Publishing Houses and Copyright took it upon itself to form and distribute new translation guidelines for museums in an effort to, as one post by FIT

“... A POET–TRANSLATOR OF THE DIASPORA IS ALSO A SURVIVOR; THEY HAVE PERSISTED AGAINST AND EVEN DEFIED A PUBLISHING ECOSYSTEM WITH STRUCTURAL BIASES, RULES, AND HIERARCHIES.”

— YILIN WANG’S LANTERN AND THE NIGHT MOTHS

the field, particularly those from marginalized groups and those specializing in minority languages.

Wang is no stranger to this system. She has witnessed her translations edited and changed without her input and her work published without her permission. Art media talked about the bombshell case she was involved in against the British Museum, which used her translations of feminist writer Qiu Jin’s poetry in an exhibition on the Qing dynasty that Jin lived through and mirrored in her texts.

stated, “help cultural institutions make more informed and ethically sound decisions on how to proceed when they wish to use translated material in their exhibitions and other public-facing activities.”

It was in the same post that FIT explained that translators are the rightful copyright holders of their translations of intellectual property, not the original author.

But for Wang, the moth’s vexed love of light also mirrors the relationship a translator finds themselves intertwined in with the different elements that constitute their intricate process.

“It is a dialogue between, say, the translator and readers or between the language that the text has been translated from what we call the source language, and the target language, the language the work has been translated into,” Wang explained.

Wang’s chosen poems are echoes from different points in

Literary translation sits on a fine line between reinventing and recreating.

“There are a lot of phrases or words that are idiomatic or culturally specific imagery with connotations and associations that don’t translate literally.”

When language-dependent concepts threaten to become lost in translation, Wang remedies this with a hefty thesaurus that allows her to play around with diction.

And when the pieces can’t possibly fit into the work itself, she finds solace in user-oriented

Halfway across the world, and by complete happenstance, Wang found a photo of her translation of one of Jin’s poems included in the exhibit — incorrect line breaks and all. Wang was not named as the owner of the contribution. Her translations were used without her permission, and she was shocked.

After a series of half-baked apologies, Wang’s work was removed from the exhibition. It took a fundraiser to help her take legal action against the British Museum and Wang’s intent to sue for the institution to settle the case with an apology for including her work without credit, consultation or compensation.

Eventually, Wang’s translation was restored to the exhibition with full credit and modest pay.

“The British Museum admitted in the statement that they had to

“I think it’s very important for translators to be aware of their rights,” Wang said. “And it’s also really important, I think, for us to form a community to support each other, to make the work less invisible and to work towards addressing some of the inequities and biases within publishing and museum spaces.”

At the forefront of translation is the creativity that honours the original work while showcasing thoughtful consideration of the target language’s conventions. It’s this dance of diction that reignites the flame of the original prose with new light — and the lantern, poetic curiosity, draws the moth in once more.

Wang framed it best during an interview on CBC’s The Early Edition.

“I believe that poetry, despite it being difficult to translate, can always be translatable. I try to capture the spirit of the poetry, and the emotional experience of reading it rather than the literal words themselves.” a

I am what our generation calls a proud bed rotter. When I am not attending summer classes, cooking or trying to find jobs that will not outright mistreat me, I can most likely be found lounging on my bed.

My bed lounges are often accompanied by music, but sometimes I allow my thoughts to have free reign. My favourite thing to think about is food and what new dish I can cook up.

My ancestry and community predispose me to a (healthy) obsession with food. I am Bengali — a group of people well known for their love of food. I also had the privilege of growing up in Kolkata, the city with arguably the best food scene in India. If you ever visit Kolkata, you will understand how spoiled for choices I was growing up.

This deep love for food, my studies in anthropology and lounging all come together to make me wonder about the history surrounding Bengali food and how this element of the culture became so rich.

The obvious sources to learn about Bengali food were the internet and my grandmother. When I ask my grandmother about it, she always tells me we never ate roti (wholewheat flatbread) before 1943. A search on the internet tells me that food in the historical regions of Bengal — Bangladesh, the Indian states of West Bengal and parts of Tripura and Assam — was affected by its proximity to major maritime trading routes as a port of the Silk Road under Muslim rule.

Besides these global and large-scale influences, local customs also revealed a dark history of eating habits in Bengal — a history of hunger and denial.

Women in Bengal, particularly widows, have historically and disproportionately experienced this denial. Social rules barred Hindu widows from consuming all non-vegetarian foods, onion, garlic and even red lentils (mushurir dal). In addition, these women often had access to very little money and were socially isolated. This meant the food they cooked and consumed had to be very economical and generate as little waste as possible.

A highly economical dish is phena (also known as fain and phen) — the excess

starch water that is discarded after cooking rice. In 1943, during the Bengal Famine, this discarded food became highly prized.

Although Bengal has extremely fertile soil and is a centre for agriculture, famines have often occurred in this region. Bengal has experienced several major famines during the colonial era from 1757–1947, but one that continues to live on in collective memory is the Bengal Famine of 1943.

Between 1943 and 1944, well over three million people died from starvation. The causes of the famine are widely debated, but man-made causes, particularly Winston Churchill’s policies, are often alluded to in academic work (Amartya Sen’s work on the entitlement theory is illuminating and recommended for perusal).

My grandmother tells me they had people beg at their door for a little bit of phena, for some sustenance to have a chance at survival. Sometimes her mother would eat the phena, and give the rice to my grandmother and her siblings. Although they had to ration food, my grandmother was privileged enough that she and her family did not starve. It was during these times when Bengalis also started eating roti, my grandmother reminds me, because wheat is much cheaper than rice.

A history of deprivation and lack of access to food resulted in Bengalis innovating, making the most of their ingredients and producing dishes that would normally be considered waste. Growing up, some of my favourite dishes were made of vegetable peels. The tough outer layers of plantains and ridge gourd mashed into a paste and eaten with rice is a dish I remember fondly.

Several traditional methods of Bengali food preparation fit into what influencers now call “scrappy cooking.” Bengali meals prepared and served at home will often include a vegetable dish and another preparation made of the peel or “scraps” of the same vegetable; it most commonly comes prepared as a bhaja or bata.

Khosha refers to peels of vegetables, widely considered to be waste products of cooking in most cultures. Bhaja means

fried, and bata refers to making a paste out of something. Popular peels to fry include peels of bottle gourd (lau), pointed gourd (potol) and potato (aloo). Bata is often made from ridge gourd (jhinge), the thick skin of plantain or green bananas (kanch kola), lau and aloo. In addition to vegetarian dishes, trimmings of goat meat and fish innards are all eaten. Scholars attribute using cheap spices and forgoing onions or garlic in these dishes to the Bengali widow.

The emphasis of Bengali food is on reducing waste and innovating food to create dishes which are greater than the sum of their parts. I am privileged enough to enjoy the food that was an attempt at survival by poor, ostracized widows and people who were faced with imminent death. I eat dishes that were born out of desperation, creativity and resilience. Although my grandmother does not divulge many details of her personal experience during the famine, her repeated reminders of Bengalis eating roti is an unspoken admission of the suffering she saw and experienced.

My grandmother’s heritage is part of mine — all the widows who lived before me assert their presence in the fare that I consume, and the victims of famines remind me to be resourceful, economic and grateful for all that I enjoy.

The greeting I hear on the phone, “Bhaat kheyechish” (have you eaten rice), has become even more endearing to me. It reminds me I am privileged to lounge on my bed and dream of food, because only two generations ago, being able to eat even the water discarded from cooking rice was precious. a

what I mean,” he said.

ken Punjabi my entire life, albeit not well, and I thought I had a good grasp on the language I considered my first. When I looked around, I saw people who could understand it and people who didn’t care to. I didn’t fit either of those, nor did I fit a lot of the ideas that constitute being Punjabi. I was sent to the Sikh-equivalent of Sunday school for two years as a kid, and all I gained was a loose baseline of ideas of our culture and religion. I can’t recite the prayers and hymns that represent the teachings of Sikhism, and when I try, it sounds like I’m speaking Punjabi for the first time — my Punjabi doesn’t hold up

I didn’t feel Punjabi or Sikh enough.

But it’s not like I’m considered Canadian either. A passport with the embroidery of Canada isn’t enough to change my position as a settler in an extremely colonial landscape, especially while being part of an ethnic group that also has a brutal history with British colonists. But I can’t be fully associated with that history — I’m not Punjabi

Forbes found that between 2013 and 2023, Indian immigration to Canada increased by 326 per cent. Asian immigrants make up almost 19 per cent of Canada’s population. The second generation of Asian Canadians that come out of that find themselves in a position similar to mine — stuck in between cultures and belonging

But it’s not like going back is an option either. On every trip to India, I found myself differentiated instantly from the eyes of my relatives who see me for where I come from rather than who I am. Digs at the way I speak, interact and view the world are always on the table to constantly highlight the difference between us. They got to exist with their heritage, and I could never compete with that.

So what am I? I can’t be completely Punjabi based solely on the colour of my skin, nor can I be considered Canadian based on the documents that constitute my legal identity. Is the identity of “Asian Canadian” meant to be a purgatory? Am I forever lost, belonging nowhere?

I pondered these questions as my brother led us through the Vaisakhi crowd. In the weeks following, I couldn’t shake the idea that second generation Asian Canadians and beyond were born to not belong anywhere. It felt cruel to thrust a gradually forming identity crisis into our destinies before we have even learned our first words. It made me angry.

“The sound is so sweet, isn’t it?”

My dad interrupted my thoughts as we sat in his car on a morning drive weeks after the festival. Gurbani was playing from a Punjabi radio station, mimicking the effect of what would play on loudspeakers in India, pene trating homes miles away. I nodded slowly, focusing on the sound of their unintelligible words.

“Did you notice your head was swaying?” He pointed at me as I shook my head.

“It’s because Gurbani reaches our soul. That’s why anyone listening to Gurbani will shake their heads instead of tapping their feet. Pay more attention next time, you’ll see

“What if people can’t understand it? Do they still shake their heads?”

He took a minute to think as he stopped in front of a red light.

“Whether you understand it or not, the sound and melody reaches our soul. It allows us to connect to each other through our hearts because we feel the same thing when we hear it.”

We were silent for the rest of the car ride as my dad’s words tumbled around in my head. It didn’t matter if I understood Gurbani, because I appreciated our culture and I shared that with others who felt the same. The point was never to fit yourself into pre-existing categories — it was to realize there were no categories in the first place. Being Asian Canadian isn’t a limbo state in between both identities. It’s a bridge to meld them together into a co-existing identity. If anything, the identity of being Asian Canadian links us to more communities than I thought. I’m connected to a Canadian, Asian and immigrant identity that connects me to communities that aren’t Punjabi.

I may not have been born in India or experience Sikhism like others do, but that doesn’t mean I appreciate it any less. I learned Punjabi, what it means to be Sikh and have a family who continues to teach me about it as passionately as I am listening.

There is no checklist of things that makes a person ‘worthy’ of their identity.

You’ve picked up this newspaper — now become a part of the team that created it! No experience required.

1. Come to our office. We work in room 2208 of the AMS Student Nest. Stop by to talk to an editor, use our microwave or just hang out!

2. Sign up for our pitch lists. Editors send out frequent emails through our pitch lists, which contain story ideas that any student can write or illustration or photo assignments. To pick up one, all you need to do is reply to the email!

3. Join our Discord server. Join our Discord server. It’s a place to find information about sections, to pick up pitches or to find out when we’re hosting events. Scan the QR code below to join.

4. Contact an editor. Interested in taking photos? Want to break the hottest UBC news? Interested in shooting or editing videos for The Ubyssey? Our editors can help with all of that! Scan the QR code below for all of our contact information. We check our emails frequently, and we don’t bite — we promise!

5. Be curious. We take pitches from students all the time. If you have an idea for a story, we want to hear it! The Ubyssey strives to cover a wide range of news, events and opinions, and we love hearing from new people. Stop by our office or contact an editor to pitch a piece.

Contributing isn’t your thing? Find new articles, videos and more daily at ubyssey.ca.

Not every piece of good literature is worth returning to. But in the case of Alice Munro’s short stories, there is always something that goes unnoticed, something the reader feels was missed the last time around that sheds further light on her characters.

On people.

Munro died on May 13 at 92 after a decade-long battle with dementia. She is survived by her three daughters.

Born in 1931 outside Wingham, Ontario, Munro was the oldest child of fox farmer Robert Eric Laidlaw and teacher Anne Clarke Chamney Laidlaw. Munro studied English and journalism at Western University for two years. When she married her first husband James Munro in 1951, the couple moved to Vancouver to start a family.

Munro began to write in the pockets of silence she found in her days as a stay-at-home mom while her children were asleep. Encour-

aged by her husband, Munro’s work was soon published in the Tamarack Review, The Montrealer and The Canadian Forum By 1968, she had written enough to publish her first collection of short stories, Dance of the Happy Shades. Munro received her first Governor General’s Award for it. She’d receive two more during the span of her career.

The recognition she received for her first anthology sparked a decade of change for Munro. In 1973, she divorced her husband and returned to Wingham, remarrying in 1976. By 1977, her first story published in The New Yorker, “Royal Beatings,” which was something of a fictional anecdote based on her father’s punishments, would spark a long and tenacious partnership with the publication.

Munro also achieved international acclaim. She was published in The Paris Review and The Atlantic Monthly

Throughout her career, Munro never strayed far from themes of womanhood, such as in her collections Lives of Girls and Women and The Love of a Good Woman

In the short story “Voices,” included in Munro’s Nobel Prize-winning collection Dear Life, a young girl at a community dance is fascinated by the comfort an older girl, Peggy, receives from some visiting air force soldiers.

“For a long time I remembered the voices. I pondered over the voices. Not Peggy’s. The men’s,” Munro’s narrator reflects. “So it wasn’t Peggy I was interested in, not her tears, her crumpled looks. She reminded me too much of myself. It was her comforters I marvelled at. How they seemed to bow down and declare themselves in front of her.”

When retired UBC English professor Dr. William H. New talked about Munro in an interview with The Ubyssey, he spoke of her as an

old friend. He calls her Alice with warmth and care.

“She was lively. She had a lovely laugh,” New said. “She had a wonderful sense of humour.”

New and Munro were friends and colleagues. They, along with Saskatchewan writer Guy Vanderhaeghe, were the co-editors of the revitalized New Canadian Library in the 1980s. Munro had an acute eye for detail, according to New. He said Munro had a knack for remembering traits of the people she met and would then integrate them into her own characters. But she also noticed the small gestures that make us human that are often overshadowed by the more obvious.

This talent is what gave readers the sense that Munro was writing autobiographically. In writing adjacent to her own life, Munro transformed the mundane into the magical just by tugging at the right words to say it.

Munro’s Nobel Prize for Litera-

ture win in 2013 made her the first Canadian to receive the honour.

“It’s rare for someone to have achieved that kind of international fame,” New said.

New said Munro enjoyed the “absurdities of life because they told her about the lives that people were actually living.”

“She was always aware that people are living a public life but then behind that public life are all the fascinations, all the delights, all the loves, all the sadnesses … that are in everybody’s life,” said New.

New said it was Munro’s talent to be able to tell the story of a person who was experiencing life’s woes in a way that we understood the complexities that were shaping the story.

“That sense of always wanting to find another way to say even better than you did last time, what you understand about the people in the world in which [you] live,” New said. “That’s a gift.” U

Heidi Collie is a London-based freelance journalist with a focus on culture and climate. Collie graduated from UBC anthropology in May 2023.

Hey Siri, play “Naive” by The Kooks.

To anyone with siblings overseas, this one’s for you.

I’ve always felt that the international student-parent dynamic gets a lot of airtime in university discourse, with reluctant updates on grades, finances, housing and relationships. But today I want to focus on everyone’s favourite middleman: the sibling you left behind.

After almost two decades of hand-me-downs, comparisons and fights over the front seat of the car, the idea of putting thousands of miles between you and your sibling might have felt like a breath of fresh air. But at some point amid the anarchy of adolescence, your relationship transitioned from “I’ll look after them” to “I’ll look out for them,” and dare say they became someone hard to live without.

Between short holidays, expensive flights and a global pandemic, I barely saw my siblings throughout my degree. Then, following my UBC graduation in May 2023, I found myself in a rocky transition back to life in my home country and these were the three people who helped me without question — with a bed, with a friendship group, with a LinkedIn connection.

I began navigating the chasm between the girls who had waved me goodbye and the women who now embraced me and realized how much time had actually passed. They aren’t 20, 22 and 24 anymore — they’re 25, 27 and 29 with husbands, houses and kids.

I had a hunch it would be tough, but I wish someone had warned me just how tough it was going to be. I wish I knew that I would miss every family event, every Christmas, birthday, funeral, engagement, bachelorette party and the first six

months of my nephew’s life. To those of you going through it: I’m sorry to say that it doesn’t get easier, you just stop getting invited. The hard truth is, 4,000 miles away, I watched the three of them do their 20s without me.

After six months of playing catch up on the lives of my built-in best friends, I have some humble advice for international students at UBC.

Initially, all four of us started with handwritten letters. I wouldn’t recommend it. Canada Post is neither cheap nor reliable and there is also no feeling like the betrayal of Google Maps accidentally sending you to Metrotown to mail a letter.

It took time, but I eventually figured out that each of my sisters appreciated a different form of communication. For one, it was long FaceTime calls. This was challenging with the time difference, but I got into the routine of calling her whenever I was up at night (in an Uber, stumbling back from The Pit or getting ready for my barista opening shift). Similarly, when she was awake all night in labour, she called me. For another sister, it was voice notes — the random tangents, intrusive thoughts and boy, did she get the business end of those finals season rants. For the third sister, it was information. I gradually learned that she felt closest to me when she knew what was going on in my life: who’s in it, my updates, my plans.

As well as finding what works for them, be clear about what works for you. After a drunken cry over the phone to my late-nightFaceTime sister, I was suddenly receiving quarterly care packages full of Terry’s Chocolate Oranges. An absolute win.

INCORPORATE THIS INTO YOUR ROUTINE

I know, student schedules are hectic, but hear me out. If you can’t manage a recurring video call, I

suggest some good old-fashioned habit-stacking.

Try ‘I’ll send you a voice note every time I walk to Sociology,’ ‘I’ll WhatsApp you my weekly updates when I’m on the 99’ or ‘I’ll FaceTime you each time I take an Uber after dark.’

You’d be surprised what a difference this makes.

STOP FOCUSING ON THE IN-PERSON ASPECT

Every time one of my sisters planned a trip to visit me and it got cancelled, it broke my heart. Fantastic if you can manage it, but you’re probably both students or in entry-level jobs, so you most likely don’t have two weeks or $1,200 to spare.

You’re desperate to show them your new life abroad, but it is so important that you learn to cultivate your relationship virtually, and maybe just be happy with this for now.

This one, with a massive dose of emotional maturity. You’re the one making the huge life adjustment I know, but understand that this is going to be complicated for your sibling too. They can love you, be proud of you, be angry at you and be jealous of you all at the same time. The way they feel might not be as straightforward as you think. Stay calm when they get it wrong, forget to FaceTime, confuse the time difference or send your gift to the wrong address. Focus on how you can be there without actually being there, keep up to date on their news and remember to ask them about it.

Truthfully, back home they’re feeling your absence more than you’re feeling theirs.

OWN IT

Finally, the most fundamental: own your decision to leave.

In practice, this means that it is your responsibility to be proactive,

Iman Janmohamed

Coordinating Editor

Hi Iman,

Many of my friends are graduating this spring but I still have another year.

figure out the communication style and fit it into both of your routines — even if your sibling is older, richer, wiser, less busy, etc. At the end of the day, you left them.

Not only are they probably being asked about you by random neighbours and distant relatives, but when family issues arise — and they do — you’re the one away hiking, cycling, skiing, travelling and learning from world-class professors. Your siblings may be picking up the pieces in ways you haven’t seen.

For me, this is reminiscent of Jo March in Little Women (2019) speaking of her youngest sister abroad, “Amy has always had a talent for getting out of the hard parts of life.”

Your sibling is missing you, but without reaping the rewards of a new life overseas.

Growing up, these were the relationships which required no maintenance. Siblings were always just there — behind you in the car, across from you at the table, in the next bed (or next to you in your bed if you had a sister as annoying as I was). Unfortunately, with a few thousand miles and the chaos of your early twenties, it doesn’t stay that simple.

These are the relationships you’ll have for the rest of your life and it’s important to nurture the connection you spent 18 years building.

However, coming from someone who accidentally neglected the importance of this, trust me that nothing is irreparable.

It took time to equate the women I see with the girls I knew, but now when they visit me in London, it’s like I never left.

My biggest lesson learned, and the one I give to you today, is that sibling relationships do take work, but that this work will be unconditionally, earth-shatteringly worth it. U

Want to join the discussion? Email opinion@ubyssey.ca.

I’m afraid we’re going to drift apart as they start their adult lives while I’m still fighting for my life on WorkDay Student.

How do I cope with my friends leaving UBC?

— Sad Super Senior

I know exactly how you feel, Sad Super Senior. Graduation season is weird, especially as you see some of your peers graduate and move away. Friends and opps alike cross the stage, and it has got me thinking: Damn, I’m going to miss these people.

A bunch of my friends I started my degree with are graduating this year, and as much as I’m upset I won’t get another on-campus happy hour, another coffee walk (or milk walk) between classes or another Marine Drive movie night, I’m so happy to have even been able to experience those moments with them in the first place.

People grow up. People move. People grow closer, and people grow apart. That’s life, and it sucks! But it doesn’t have to.

Odds are, your friends are just as afraid of drifting away as you are, so spend extra time with your friends before they move, celebrate their graduation with them, set up a standing time for a weekly FaceTime call — make an active effort to include them in your life though you might be apart.

University is a time of rapid change and self-exploration. You and your friends found each other in the chaos of exams, breakups, papers, makeups, a global pandemic and everything in between.

That’s beautiful.

Eventually, you’ll cross the stage, parchment in hand and you’ll join your friends on the other side of convocation. But until then, keep trucking along.

You’re doing great. Keep it up! U

Got some burning questions? Want advice from an English major? Send questions to advice@ubyssey.ca, or submit anonymously at ubyssey.ca/ pages/advice

UBC professor Dr. Jerry Ko-Beach discovered professors have lives and go to the beach in his 2024 study titled “Professors in the present pre-postmodern age.”

Ko-Beach surveyed professors across the Lower Mainland to learn more about their “lives.”

Ninety-eight per cent of surveyed professors said they “do things outside of academia.”

“There are misconceptions created by urban legends, students and suburban legends that professors — or educators, more broadly — only do nerd shit,” said Ko-Beach in an interview with The Ubyssey. “We also do cool shit, like go to the beach.”

Ko-Beach said 89 per cent of respondents enjoy going to the beach, and 99 per cent would go “if they want to, or if their friend was hosting a picnic or maybe for a first date or something.”

No respondents mentioned building a sandcastle, which is pretty fucked up because I like sandcastles.

Ko-Beach said the general public may be confused by these findings despite them being “not surprising at all.” I disagree — it’s

A MATRIMONIAL SLAY //

a universally known fact that teachers live at school. Since the establishment of professors, there have been no recorded sightings of professors in non-academic environments because that’s the way things are, according to science.

When asked if professors live at the university, Ko-Beach had something to say.

“No.”

This fascinating revelation has shocked UBC students across the Vancouver campus. Students have drawn attention to Ko-Beach’s study, with some calling it revolutionary.

“Yeah,” said Dore Kuh, firstyear mixology and broistry student. “I’ve always thought of professors as nerds, but they are so much more than that. They also go to the beach, and I think that’s beautiful.”

Community members — students and academics alike — spoke in support of the study, commending its use of the words “study,” “research,” “epistemology” and “beach.”

However, Trai Hardê, a thirdyear rizzology student, doesn’t believe that Ko-Beach’s research is squeaky clean.

“Dude, Jerry Ko-Beach is a

prof, of course he’s going to make it seem like he’s cool and has a life,” said Hardê.

Ko-Beach was appalled by this comment.

“What? That is … preposterous! That is so untrue. I- I can’t believe someone would say that,”

said Ko-Beach in between sobs.

“Life is defined as the condition that distinguishes animals and plants from inorganic matter. Do I look inorganic to you? I am so organic! I’m a vegan. Besides, Descartes once said…”

In an attempt to get to the bot-

tom of this (journalism moment), I asked Ko-Beach what his plans were for tonight. He screamed into a fuzzy blue throw pillow for 36 seconds, did a double dab (you don’t even wanna know) and then said he would get back to me. He didn’t. U

Aisha

So, you fell in love at UBC. All that stress bonding over finals led to an attachment that you will keep sealed in your heart forever, like that mysterious mouldy container under your bed that you’re too scared to open.

After a sleep-deprived proposal in IKB and 1.5 torturous months of waiting, it’s finally time for your big day. And where else would you rather get married than the very campus at which you fell head over heels in love?

Getting married in the Nest or the Rose Garden is tried and true — aka boring and unoriginal. So, to make sure your special day is truly special, I’ve painstakingly composed this list of better places to get married on campus.

THE SPOT AT BUCHANAN… YA KNOW THE POND THING IN THE COURTYARD

What finer place to be married than in the courtyard of the building that is often considered one of the ugliest on campus? Can

someone say “better-looking by comparison?”

Gazing at the prison-like view of Buchanan Tower will suddenly make your student budget wedding decor feel luxurious.

This spot would also be so special since it’s probably where you proposed. I have seen so many proposals at this location it is not even funny.

Students milling around as you say your vows, the drab almostwhite-now-turned-gray-due-todirt colour of the building — it’s truly the scenic peak of romance.

Everyone wants their big day to be special, unique and different from everyone else. The ideal place for this would be the infamous tunnels under UBC.

It’ll be the most elusive and private spot on campus. Finding it is a fun little challenge for the guests — like an escape room but in reverse. And bonus: you’ll find out who your true friends are since half of the guests will definitely get lost in the tunnels and never make it to your location, and half won’t even try because they’re too scared to potentially get arrested (lame).

The white wedding dress will definitely pop in the pitch black of the tunnels and you’ll have a small army of mice, spiders and centipedes in attendance at the ceremony. Cute!

SOMEWHERE OFF CAMPUS…

You... you should just do this one. …Kidding! I would estimate that 99 per cent of weddings don’t happen at UBC. So, would you rather have a really nice wedding somewhere else, or a really different wedding here? The answer is pretty clear.

WRECK BEACH