1.

2.

Business

Account

Web

Abbie

3.

1.

2.

Business

Account

Web

Abbie

3.

I’ve always struggled with being feminine.

I’m conscious of the way I speak — my voice sits a bit low, my jokes don’t land and I’ve never quite been able to emulate the warmth and joy I’ve noticed other girls convey effortlessly when they talk.

My nails are never painted, and when they are, there’s always polish spilling over onto my cuticles. I skipped out on a 1D phase and couldn’t see the appeal of reality TV. I didn’t like talking about boys. I’m not poised or graceful, and my high school dance teacher will attest to that.

I didn’t do or feel these things because I wanted to be different. In fact, I wished so hard to be able to become my idea of what a girl should be.

That never happened, of course, but as I’ve lived through new experiences and met different people, I’ve realized that femininity is more than any of these things.

I’ll let you read on and learn more in hopes you decide what femininity means for you. Through both self-reflection and analysis of phenomena larger than ourselves, this issue approaches femininity from different angles to try and capture just how broad it is.

femme isn’t just for women — because femininity is in everything and everyone. I hope these pieces encourage you to look for it and embrace it. U

was nine when the world started to appear a lot blurrier than usual. I couldn’t see the whiteboard from the back of the class or properly focus on the faces of my friends as they spoke in front of me. Life often looked like how the sun is perceived: a blurry image that seems defined and visible from where we are, while actually being far from what it actually

I hadn’t noticed. The gradual decline of my eyesight passed me by as I went about my days, talking to my friends and going to school with blurry vision thinking nothing was amiss. It was at an optometrist check-up when I first considered the possibility of

With enthusiasm, the optometrist told me my first pair of glasses would make all the blurry edges straight and defined. But what excited me most about them was that I could pick any type of glasses in any colour, and I chose pink. Externally, I picked these glasses with a show of disgust. Pink was for girls, and I didn’t want to tarnish the tomboy reputation I held at Internally, however, I chose pink to prove to myself that I deserved to be

I was born a girl but grew up around boys. My female cousins were too old — and too cool — for me. I was awkward and made stupid references about Power Rangers and played video games — traits I picked up from the male cousins who were my age and whom I spent most of my childhood with. I had plenty of female friends who all seemed similar to me, making stupid jokes and playing the occasional game, except for the fact that they seemed more girly than I did. They didn’t wear hoodies all the time, have a masculine gait when they walked or make obscure references to shows aimed at boys. It bothered me that I felt so different, motivating me to show everyone and myself that I wasn’t different by inten-

From a young age, femininity was a highly structured exploration of self. As we grew up, the category became defined based on what constituted being girly: letting your hair down, wearing makeup, being more aware of how you presented yourself in the clothes you wore. Most of that was uncomfortable and sometimes unachievable for me. But the pressures I felt from home — the ones that expected me to adhere to the female cultural norms defining

It wasn’t that I felt more masculine than I did

feminine. It was that I was both, simultaneously, and I didn’t know how to walk that line. I was so comfortable with my masculinity, yet still pushed it away from me. For seven years after I chose my pink glasses, I still actively repressed my femininity.

It was an act of rebellion; a show that I wouldn’t conform, and a cry for help to be given the space I needed to properly explore who I was. I didn’t want to wear makeup or dresses, but that also meant I couldn’t embrace the parts of femininity that I liked, like wearing skirts and styling my hair. I began restricting and resenting those expressions of myself.

Sometimes, I wanted to be able to go to parties wearing jeans and a flannel like my male cousins instead of wearing Indian suits with uncomfortable dress shoes like I was expected to. But that didn’t mean that other times I didn’t enjoy wearing suits and uncomfy shoes. Sometimes I wanted to feel pretty, other times I wanted to feel handsome; I was betraying both sides by not picking one.

Over the years, I went through a couple pairs of glasses as my eyesight worsened. The pink glasses were my only pair in a fun colour, and the rest of them were black. It felt more neutral and prolonged the inevitable choice I would have to make.

Eventually I’d get contact lenses. The process of putting them in for the first time took forever. For 15 minutes, I stood in front of my bathroom mirror, blurry-eyed and struggling. It was when I took a break from failing that I looked around.

For the first time since I had gotten my glasses, I took a proper look at the world the way I was biologically structured to see it. Sure, the glasses made things clearer and it was the way I was supposed to see the world: clear, defined and straight. But my body rejected the clear, defined and straight for the blurry. I couldn’t see edges of walls or features on people’s faces as they melded with its surroundings — but that didn’t mean they didn’t exist.

Gender expression isn’t something to be categorized or defined. It’s fluid and malleable. If I simultaneously felt feminine and masculine, then I could be that. There was no need for me to choose because both would exist within me regardless.

As I got more comfortable putting contacts in, I also began to embrace skirts and styling my hair as much as I would wear hoodies and flannel jackets. I found a compromise to wear a female version of male Indian attire at parties so I could feel both pretty and handsome. I could exist by accepting their coexistence, residing at their intersection.

Accepting my femininity came after the pressures of conformity, choice and not letting myself break defined categories that never really existed in the first place. Placing myself on a spectrum instead of inside a box allowed me to embody everything I felt was right to me, whether it be lip gloss instead of a full face of makeup, or skirts and not dresses.

Gender expression doesn’t define me because I define it, and I choose to make it blurry. U

Whenyou’re a woman, you can’t really separate yourself from your body.

Hide your tampon up your sleeve. Show enough skin, but don’t show off. The government might even make decisions about your body for you. Girls as young as 13 are using filters or altering their photos to appear skinnier, whiter, with smoother skin — all to be conventionally “prettier.”

When you’re in a woman’s body, society will never let you forget it. The intersection of femininity and bodies percolates into media, fashion, sports, mental health, politics and everything in between.

At UBC, students not only grapple with these pressures, but are curious about them too.

Dr. Kim Snowden, a professor and undergraduate chair of UBC’s gender, race, sexuality and social justice (GRSJ) program, teaches GRSJ 401: Gender, Body & Society, which addresses many of these ideas.

In an interview with The Ubyssey, she said the course draws a variety of students, and although it is not purposely focused on women, it often draws a lot of attention to femininity.

“There’s a lot of interest in thinking about the policing of certain bodies … or who is more prone to forms of discrimination that focus on the body,” said Snowden. “It does seem that at the centre of that is gender, and particularly women’s bodies, or those who identify as women [are] dealing with this more.”

Second-year media studies student Kaylee Ainsworth said societal expectations sometimes make it difficult to be content with femininity.

“It’s hard to feel satisfied all the time because there’s so much pressure to look, and even act a certain way, as a woman,” said Ainsworth.

These pressures manifest into what’s called the feminine ideal.

According to Snowden, the societal feminine ideal is thin and clean-shaven, with symmetrical features and nice hair. She also said Western conceptions of femininity, including a focus on white, cisgender and able-bodied people, have become the “universal ideal” because of media’s transnational nature.

“I think that particularly in media and culture, there tends to be a reproduction of a certain kind of body ideal,” she said. “Even in advertising that is pretending that it is for all bodies or all people … [they] very much fit an ideal of what a feminine beauty looks like.”

For example, in January, American Eagle’s sister brand, Aerie — which is known for its body positivity — posted about its seemingly inclusive swimwear lineup, but quickly garnered backlash for its lack of size, colour and ability diversity.

Influencers, such as @samyra on TikTok, find marketing for plus sizes to be reinforcing certain standards and ideals. As a plus-sized woman, Samyra has a series highlighting the struggle to find plus sizes (such as 1X, 2X or 3X) instead of just larger straight sizes (such as XL or XXL), especially in stores, not just online.

In one video, she went to Kohl’s — which does carry plus sizes on the rack — but noticed most of the options have phrases such as “slimming panel” or “puts the flat in flattering” on the tags.

“You tell us through the language of your other clothing offerings that we shouldn’t wear the bodycon dress, the crop top, the mini skirt, etc,” she wrote in the caption. “You teach us to be ashamed of our bodies.”

Snowden also pointed to an example of how the media seems to comment on women’s appearances — who they’re wearing, how long it took to get ready, why their body looks how it does — even if the interview or article

“what we’re seeing online and social media, I feel has created such an unrealistic expectation for what women should look like, especially with [the] culture of influencers.”

— Kaylee Ainsworth, second-year media studies student

isn’t about their bodies or fashion.

“Even those subtle engagements tell us something about what we should be looking at in that person, as opposed to what they’re saying, so that the appearance becomes standard,” she said.

The rising prevalence of social media has only increased those subtle engagements.

“Social media is such a big influence, and it’s so pervasive. It’s something we spend so much time on, and … our feeds are curated in [ways] that are showing the ideals of other people’s lives,” said Ainsworth.

A 2022 study found that images of other women on social media influence the expectations young girls have for how they should look. It further found that although adolescents might know photos are edited, it doesn’t stop them from making negative comparisons and striving to look like an “ideal.”

“We still buy into those things, right? And it’s hard not to, because we’re inundated with it,” said Snowden. “It’s just become normal in what we see.”

As influencers’ popularity rises, so do new body ideals and expectations. The “slim-thick” hourglass ideal, characterized by a slim waist and large breasts and butt, blew up thanks to celebrities like Kim Kardashian and Jennifer Lopez. When Kylie Jenner revealed she had lip fillers in 2015, worldwide searches for lip fillers went up 3,233 per cent, according to allure

However, as trends change, wealthy celebrities have the ability to reverse procedures to fit the new ideal, while the average individual does not — creating unachievable norms.

“What we’re seeing online and social media, I feel has created such an unrealistic expectation for what women should look like, especially with [the] culture of influencers,” Ainsworth said.

But there is an opposite side to every coin — there has also been a recent rise in "body positivity" on social media. Influencers like Spencer Barbosa and Megan Jayne Crabbe are actively showing how bodies can be manipulated by light, clothing placement or posing, and are reinforcing what a “normal” body looks like. According to a 2021 study, these types of messages can increase body satisfaction in women.

Ainsworth shared how seeing media praising love handles is a positive experience, especially since the hourglass figure is placed on a pedestal.

“As someone who has very wavy hips, that’s pretty affirming to see,” they said.

Further unconscious messages like heteronormativity — the assumption that being straight is the default — also shape expectations and experiences of "ideal" femininity.

“The idea that ideal femininity is attached to a certain body type, which is attached to a certain kind of relationship, and this is reproduced consistently, even though we have divergence from that … that ideal is still there,” Snowden said.

Ainsworth agreed and said her feelings and presentations of femininity are influenced by romantic relationships.

“I feel like the pressure to outwardly express myself as feminine and as what I deem a woman to be a lot stronger when I’m in a heterosexual relationship,” they said. “But if it were up to me and I just dressed and presented myself the way that internally I feel like I would want to, I would definitely be dressing a lot more androgynously.”

Ainsworth said her presentation of feminine — baggier clothes and backwards hats — doesn’t have to do with low self-esteem.

“I don’t think my desire to cover up my body comes from a lack of feeling comfortable in it,” they said. “I think that’s what’s more comfortable, both in terms of how I want to present myself, but also in terms of physical comfort and clothing.”

Part of Ainsworth’s relationship with femininity also includes acknowledging how certain aspects of their body — such as her chest — tend to be seen first in the eyes of society and shifts that away from the core of their being.

“When I’m at a club and I’m wearing a revealing top, why is [my chest] the first thing that a man looks at?”

“Why do [my breasts] need to be central to my identity?”

Femininity ideals are closely connected to parts of women’s bodies linked to reproduction, such as breasts or uteruses. Snowden mentioned the expectation for pregnant people to lose their baby weight — that women must have children, but their body shouldn’t look like they did.

“So there’s this sense that it’s pitted, for me, against the idea that if you’re not like this, somehow you’re failing at how your body should look,” said Snowden. “You’re failing at being women, or you’re failing at being feminine, right?”

“Because I think a lot of ideal femininity narratives

“there’s this sense that it’s pitted, for me, against the idea that if you’re not like this, somehow you’re failing at how your body should look.”

— Dr. Kim Snowden, professor and chair of UBC’s GRSJ program

are tied up in things like motherhood, or they’re tied up in things that are perceived to be natural for women, which excludes so many people, and just isn’t realistic for how most people live.”

The concept of biological sex or hormones as a basis of femininity is often used by right-wing advocates to alienate individuals who don’t fit into the ideal. During the Paris 2024 Olympics, boxer Imane Khelif was scrutinized, being accused of “gender chicanery” because of how she dominated her quarter-final match. Also, Trans women face criticism for not being ‘real women’ because they don’t have the same experiences as women assigned female at birth.

For Ainsworth, all of these underlying messages reinforce that expressing femininity will always be tied to our physical bodies and society’s black-and-white perceptions of what a feminine body is and how it should be labelled.

“I also feel that no matter what I do or how I present or how I dress, people are always going to think of me as a woman, even if that’s not what I want them to perceive me as,” they said.

Despite these instances, there has been a shift in the definitions of what does or doesn’t constitute a woman or feminine body as the understandings of gender have expanded.

“I think … because we have a different understanding now of gender and sexuality, there is a pushback to what that idea of femininity looks like,” said Snowden.

For example, Billy Porter graced the 2019 Oscars red carpet in a tuxedo dress, changing the fashion game and opening up opportunities for other men to play with clothing without expectations of a coming out. Just a year later, Harry Styles was on the cover of Vogue in a dress.

“What I’m seeing [in class] is less of an inclination to assume that femininity means one thing and one thing only. We understand it in multiple different ways,” said Snowden.

Snowden said a lot of this understanding and defiance of typical femininity comes from more people having gender literacy — something that depends on who’s in power.

For example, Florida’s “Don’t Say Gay” law prevents gender identity education under grade 8 and restricts reproductive health education until grade 12. In last month’s provincial election, the BC Conservative Party campaigned to end SOGI 123, the province’s sexual orientation and gender identity education program — which researchers have found keeps all kids safe.

Even though there has been a shift, Snowden said it’s not necessarily a shift in the overall ideal.

“I think what’s changed is how we push back against it, and what’s changed is the awareness of how things are manipulated to make us think that we should look a certain way,” she said.

Recent research studies have negatively linked social media usage and the need to conform to body ideals — we’re now more aware of how they make us feel. People are deconstructing the idea that Renée Zellweger was overweight in Bridget Jones’s Diary (because she wasn’t).

Outside of the media, people are pushing back against the idea that in order to be “feminine” they must conform to the ideal. More women are working in the trades and lifting weights. More women are choosing not to shave body hair. Gender neutral and gender fluid fashion is on the rise.

Femininity can’t be pinned down by pink bows or a snatched waist or whatever other gender norms there are because femininity is all of that and more. It’s a personalized understanding — and nobody can take that away.

“We have to hope that young people push past those things … so that we can continue to grow as a culture and push back from what is considered the norm,” said Snowden. U

At my summer student trades jobsite, everyone wore the same thing: an orange long-sleeve shirt and navy blue fire-retardant pants, both with reflective safety striping. Everyone looked the same. Well, mostly everyone.

My pants had ripped hems so I wouldn’t trip over them, my orange shirts looked large even in the smallest size. I stood a minimum of six inches shorter than everyone else, taking three steps to keep up with their two.

As a woman, I already had so many reminders that I was different from the rest of the crew. I didn’t want my femininity to be another one, so I hid it as best I could. I kept my hair in a low ponytail or bun, my pre-shift outfits were plain and boy-ish. And it worked; I felt like ‘one of the guys.’

Sure, it sucked to feel like I couldn’t have little bursts of joy, talk about pop music or complain about my period, but I figured that was the job. And since I liked the job, I had to like giving up being a girl.

I was in the trades for nine months before I realized that wasn’t true.

At my first official boat training that two other (all-male) crews had travelled up for, I stood alone as the only female in our department. One other woman was there, and although a solace, it was a stark reminder that we were outnumbered. Like any young woman would be, I was nervous. I knew some of what we were doing, sure, but everyone else had taken this training at least three times before. I didn’t speak up a lot because I was scared to be seen as just a girl who was in over her head.

But before we went out on the water, the other woman took me aside and gave me a pep talk that changed my perspective entirely.

“You’re among some of the hardest men and you’re thriving,” she told me. “They accept you. Give yourself more credit.”

It suddenly struck me that as much as I had been self-conscious about being a woman, everyone else was conscious about it, too. My femininity

was never invisible like I tried to make it, but they didn’t care. As long as I did the work, it didn’t matter to them if I was a girl.

So I started to show some femininity. It was subtle — braiding my hair, playing Taylor Swift on the stereo, wearing dresses before shift — but it was enough to make me feel like more of myself again. To my surprise, my crew treated me the same. If anything, they seemed happy that I was happier.

If I end up working in the trades again, I’ll still struggle with being the only woman on the crew.

My crew is “the nicest in this field,” but even then, it took eight months to gain everyone’s acceptance. I know, at least to some extent, I will be underestimated, glossed over and will have to work twice as hard for respect.

But I hope the pink nail polish under my gloves will be a reminder that I don’t have to hide my femininity to be accepted or respected — at least not all of it. U

words by Olivia Vos

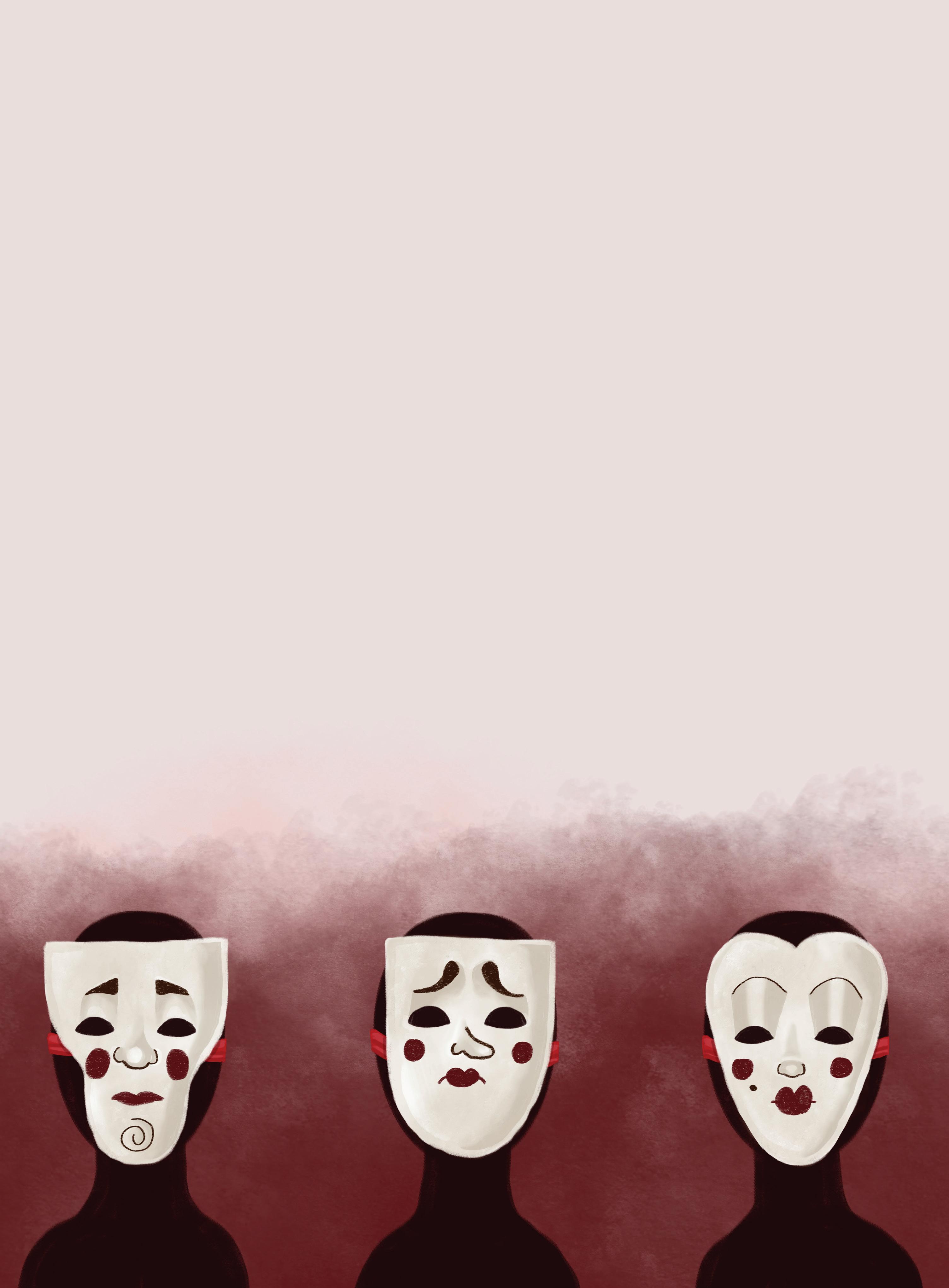

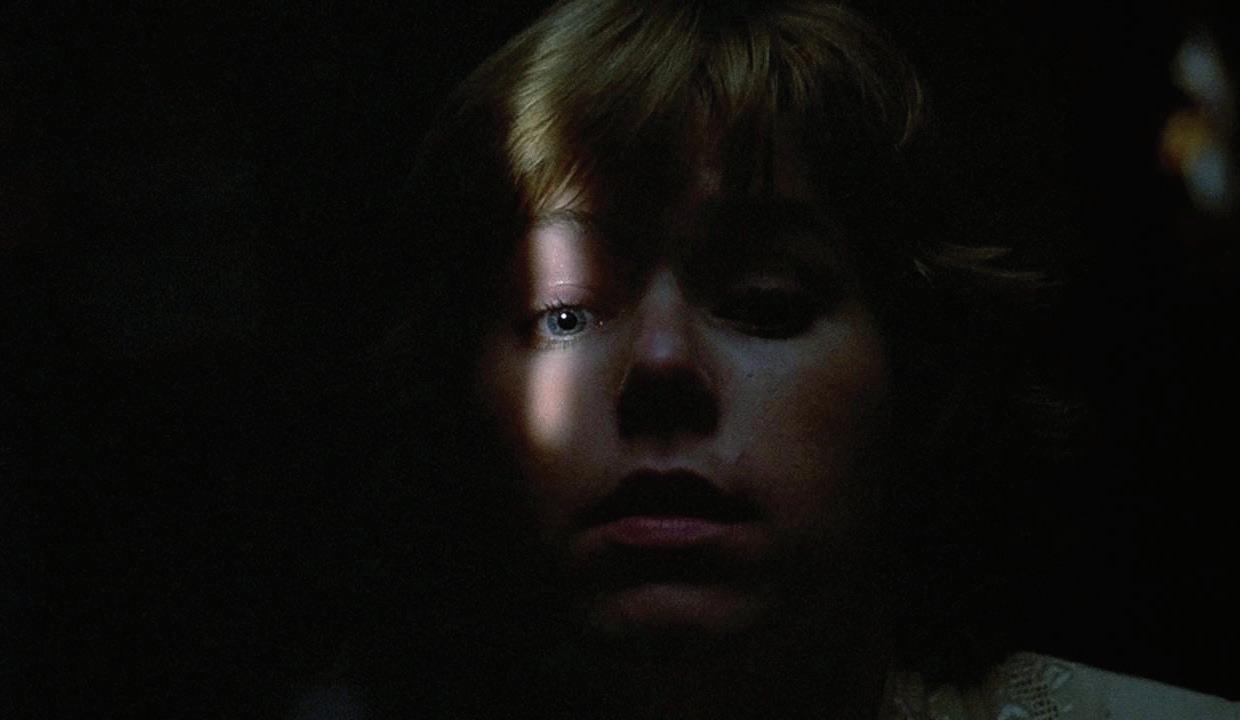

photos courtesy film-grab.com

t’s a chilly October night. You’re in a dorm room somewhere on campus. Wind howls outside as rain patters against the window relentlessly, filling the sidewalk below with a slew of runoff and leaves. A scented candle burns on a side table as the sound of popcorn crunching and wine sipping mingles with the tense atmosphere in the room. Everyone is silent.

The protagonist, illuminated on your friend’s laptop screen, stares right past the camera. Her eyes are wide and the button-up shirt she’s wearing is torn, blood seeping through the fabric. Dirt is smeared all over her face, disrupted only by streaks of tears formed from the long journey she faced that night.

Suddenly, a masked face appears behind her, machete raised inches from her head. Everyone screams at the screen hoping the protagonist will hear them. Popcorn flies across your friend’s bed as the killer steps closer, honing in on his target.

Then the girl turns around. She knows the killer’s dirty tricks after having fought him for the past 30 minutes. She pulls out a piece of scrap metal she’s been hiding up her sleeve and drives it into the killer’s heart. As she stares down at her foe in victory, everyone in the room lets out a sigh of relief.

You may walk away from this movie excited the male director let a woman be the hero. It’s from the ‘90s, so you’d expect a guy to be the one to take down the villain and save the day. But as you watch one slasher film, and then another, you begin to pick up on a pattern. Is the horror genre truly smashing the patriarchy, or is it all a facade?

The trope of the final girl was first presented in 1987 by Carol J. Clover in her book Men, Women, and Chainsaws. As gender analysis within the slasher genre grew more popular in the ‘80s, it became apparent that a pattern of women being the sole survivor of a horrific murder spree was a recurring theme throughout the latter half of the 20th century.

The three final girls that typically come to mind first are Nancy Thompson from A Nightmare on Elm Street, Sidney Prescott from Scream and Alice Hardy from Friday the 13th

All of these characters come from cult classics in the slasher genre (making them highly recognizable) and follow a specific set of “rules” that qualify them as final girls.

The first is an aversion to nudity and sexuality, which play a large role in deciding which characters are murdered in a slasher film. In Friday the 13th, Jack and Marcie are killed almost immediately after having sex in one of the cabins. In contrast, the final girl Alice is seen being hit on by the owner of the camp Steve Christy, but she turns down his advances — she’s an attractive girl, but it’s made clear to the audience that she wants no part in sexual promiscuity. Because of this, she’s “rewarded” at the end of the film by being the sole survivor of the Camp Crystal Lake massacre.

In addition to sexual innocence, all of the girls face long, grueling fights with the antagonists in their movies. They typically use intelligence to fight the killers — they only turn to extreme violence when absolutely necessary and it is sometimes

never seen at all. Elm Street ’s Nancy sets traps and effectively tricks the child murderer Freddy Kruger into his own demise, ending with a scene where she stops giving him power by not being afraid of him anymore. This ending seems unconventional: why isn’t there a satisfying vanquishing of the villain after Nancy’s grueling battle?

This question is answered when we ask why final girls are used so frequently in the slasher genre. And to reach this conclusion, it’s important to note that these films were made by men, for men. While it seems unconventional to put a woman in the position of a hero in this context, there are actually several reasons why it makes sense that the final girl was created for men.

As mentioned before, she is sexually innocent, a victim, a damsel in distress. She isn’t a force to be reckoned with — just a girl who got lucky enough to escape and eventually craft a plan to take down evil. She is controllable; her curiosity can only know set boundaries before she is punished.

She’s also used for shock factor. The fact that she has survived being chased by the boogie man, stabbed at by a crazed old woman and has watched all of her friends die is shocking. She shouldn’t be alive, but there she is, finally wielding a reasonably-sized weapon (a chainsaw would be too violent, obviously) and ready to win this battle (until the sequel, of course).

So why do men want to see this on screen? I believe final girls weren’t created with a specific answer in mind, so here are a few potential reasons why men would want to see a woman in this position.

Movies are created to transport us to a new reality, and in the ones depicted in slasher films, the position of the ‘strong male hero’ hasn’t been filled. Everyone is dead, a murderer or a practically defenseless woman, leaving space for a good male protagonist. This allows a man to envision himself in this setting as a knight in shining armour for our innocent victim. He can watch an attractive woman be tortured and attacked, but if he was there, the killer would have been dealt with already. He is stronger than the men who have been killed and stronger than the crazed lunatic who wants to slit everyone’s throats. The final girl just barely survives on her own, but she would be safe if he was there to protect her.

On the surface, it is refreshing to see any female protagonist on screen. In a world of men as the typical hero type, watching Sidney kill Billy Loomis with a bullet to the head after she learns he murdered her mother is objectively satisfying.

But watching for deceptive feminist tropes is important. Women deserve to see themselves on screen — not an innocent, submissive, toned-down version of who they truly are. They deserve to see protagonists who are allowed to be strong, crass, violent, loud, disruptive, angry, sexual and masculine — even innocent, if they want — because those are all things that women can be simultaneously.

The final girl script needs to be left in the ‘90s to make way for true representation: a final girl who not only survives the night, but is allowed to be tough while she does it. U

Ialways wanted an older sister growing up. I so badly wanted someone who had already experienced everything I was going through — someone of a similar age to talk to, to look up to and to have my back.

But for better or for worse, I am the eldest of three kids, which has come with its own challenges. I often wish I wasn’t, because sometimes the responsibility makes me want to lash out.

Being the eldest, especially as a decade older than my youngest brother, means my siblings have gotten away with being naive longer than I ever did.

Of course they can get away with being babied for longer, because I’ve already learned everything. I drive my brother to soccer practices, help read over my sister’s essays, aid my grandmother in the kitchen — when I'm at home, I’m interrupted every 10–15 minutes because someone needs something from me.

For the most part, I don’t mind it. I don’t mean to sound spoiled, because I love my family, and this is the least I can do.

But not only do I have to guide everyone else through their lives, I also have to live my own with other people’s interests in mind — it's up to me to accomplish things for them to see. If my grandparents want to see one of their grandchildren get married or have a kid, then I have to do that. Do I want to do those things? I don’t know, but I also don’t know if my grandparents will be around when my siblings are old enough and ready to get married.

When trying to balance work, school, friends, relationships and family, I’m being yanked in every direction other than the one I want to be in.

I think the worst part is that my siblings don’t

consider the time I spend helping them as time spent with me. When I’m coming home from 12-hour days at school, the only thing I manage to do is lay in my bed and try not to think of all the work I still need to do. My brother doesn’t think the hours I spend taking him to soccer or swimming or taekwondo or school performances or sports days or making sure he’s fed and showered really count — he just wants to play games with me. I know it’s not the same to him, but I’m so exhausted sometimes I can barely get up in the morning.

When I see my friends living their lives completely by their own schedule, I feel a horrific sense of envy — I also don’t want to be called a billion times when I’m out past 9 p.m. or have to check my entire family ’s calendar before making plans.

Every day it feels like I’m failing everyone a bit more. Every day it feels like there’s more I can’t tackle. And every day I get a little closer to giving up.

I’m watching everyone battling things I can’t fix for them. They’re getting older and falling ill and there’s absolutely nothing I can do to stop it.

I just don't understand. If I was raised to hold everything together, then why is it crumbling in my hands?

But it’s not all bad. I get to be the one to show my sister all the music she should be listening to, and I taught my brother my hot chocolate recipe. I was the only person my grandfather taught how to ride a bike and my grandmother only ever trusts my opinion in the kitchen.

I have been given so much special treatment for being the first, so how could I ever truly be mad? I just hope I can be the eldest sister I always wanted. U

It’s been just over one year since UBC Drag announced it was going on an indefinite hiatus.

The collective of drag performers, founded by Liam Hart, used to host biweekly events at Koerner’s Pub. It was a safe space for UBC’s Queer community to let loose and have fun, and for countless up-and-coming performers to find their footing in the Vancouver drag scene.

Now, the group may be gone, but its legacy lives on through the performers who emerged from it and the current students who take inspiration from the project to keep drag alive at UBC.

Acacia, an international relations graduate, worked as the UBC Photo Society’s studio manager and ended up spending a year taking photos for UBC Drag.

“I remember the best part about it was that I got to meet so many different performers from around the city,” they said. “Everybody’s nice to the photographer, so it was really easy getting to know people.”

They did a photoshoot with Mx. Bukuru — the driving force behind the Haus of Bukuru, a drag house for Vancouver-based Black and Trans/ non-binary performers — who asked if Acacia had ever considered doing drag.

Acacia joined Haus of Bukuru, and now hosts and performs in drag shows all over the Lower Mainland.

Drag houses are a chosen family, often led by a more seasoned performer who can guide their “children” through finding their place in the scene. But houses aren’t just mentorship — they’re a means to find solidarity with others who practice an art form that’s far too often the target of transphobic scrutiny.

Similar to Haus of Bukuru, many houses consist of performers who share intersecting marginalized identities.

House of Rice is an all-Asian, Canadian drag family that, according to drag performer and human geography student Carrie Oki Doki, was first introduced to her through an essay she was writing for an Asian Canadian and Asian Migration course.

Around a month after working on her piece, she booked her first show with one of House of Rice’s members, Maiden China — which she described as an ‘I made it’ moment.

Although Carrie Oki Doki is now a skilled performer and makes most of her outfits by hand, it took her some time to get to this point. She first got her start in drag through cosplay, and recalled how the first few times she went to anime conventions in makeup, everything was a bit rough around the edges.

“At first I thought, all I need is no lashes, a whisper of blush and a little tiny baby wing, and I went out looking terrible,” she said.

But Gaia, a performer and current commerce student, takes the cake for the most unconventional drag debut — at a Sauder orientation event.

She had wanted to try drag for a while, and when a friend asked if they could do a performance together, she seized the opportunity. It was difficult to guess how people would receive it, but other students ended up approaching Gaia afterward with a sense of admiration.

“I feel like in the Queer community, there’s different levels of comfort in terms of expressing yourself and [being] extremely out in public,” she

said. “I saw the power of drag in other people, but also how much power it has in me, in terms of expressing who I am and living my truth through music.”

As an international student, Gaia came from an environment that she felt was a bit closed-off in terms of information — she moved to Vancouver to find a more accepting environment, but was surprised to learn how people perceived drag.

“I didn’t know how much people appreciated drag, but at the same time, I didn’t know how much some people feel strongly hostile against it,” she said.

All three of the performers expressed how it can be difficult to confront the judgment that can come with being involved in drag — almost always from people who don’t fully understand what it is and why artists do it.

“Some of the common misconceptions [are] children shouldn’t be at drag shows, for instance, or children can’t enjoy drag,” said Acacia. “If you are a person that goes to drag shows, you know that that’s not always the case.”

There’s a common headline of drag performers being invited to host story time events at local libraries and being met with protests insisting drag performers are inappropriate for children to see.

“[There’s an] increasing rise of transphobia and the current use of drag performers as a proxy for predators to basically be used as a political scapegoat, to just throw under the bus,” said Carrie Oki Doki.

In reality, drag performances come in many different forms and styles, and a lot of them are child-friendly — and some aren’t even related to gender or sexuality at all.

For these three performers, however, it is tied to experimenting with gender expression. Because they’re playing characters, taking on a drag persona allows them to lean into femininity in ways that they wouldn’t usually do in daily life.

“It reveals a version of me that I know is always there, but … especially now that I perform in drag, I don’t always feel the pressure to tap into that hyper-femininity all the time,” said Acacia. “When I’m out of drag, I feel comfortable also being in the sort of in between.”

And being a queen isn’t the only type of drag — hyper-masculine performers are out there, too.

“There are performers that are hyper-feminine, hyper-masculine, hyper-monster-y,” said Gaia. “Drag is free gender expression, which means not everyone does drag to be hyper-feminine queens. Some of them are cunty, amazing, shocking drag kings, who can do so many good things.”

And Carrie Oki Doki emphasized that doing drag really is for everyone, regardless of gender — even people who are completely okay with their cis identity and presentation.

“It’s like a tool … you’re using [it] for fun and performance, but that doesn’t necessarily mean that the tool then informs how you go out in your day to day,” she said.

Really, anyone can help uplift and expand the drag scene at UBC. All you need is a bit of confidence, a lot of patience and a creative vision.

“It’s a very long route and I’m not quite there yet, but I’m on my way,” said Gaia.

“Whoever’s [reading] this, I’m happy you’re on your way too.” U

words by Fiona Sjaus illustrations by Ayla Cilliers

In my life, there were always bags.

It’s 2012, and Mom is pushing a cart in between the racks of colour-coded purses at the Winners down the street from the Superstore we frequent. I’m looking up, marvelling at the glitziness of the plastic and zippers, cross-eyed from the dizzying fluorescent lights.

Like Mary Poppins, Mom is searching for something to hold the world over her shoulder. And I’m disoriented, but all my thoughts are flickering to focus in on a floral purse — I want it over my own shoulder. In there, I want a wallet stacked with strange papers, coupons and cash of continental currencies. I like its side pocket, shaped into the perfect compartment for my lip gloss and my hair clips and my Barbie doll that I take on long trips but that no one’s allowed to know about.

When I got my first big-girl job, Mom gave me a handbag that had been collecting dust in the depths of her side of the closet. It had the perfect compartment for my lip gloss and my hair clips… and my tampons and deodorant and pepper hair spray. Now my Barbie sits in the splits under the stairs, laced with cobwebs, and I spent all my Swiss francs in Zurich two Julys ago.

Sometimes I feel strongest when I’m walking in strides larger than me back from the Superstore I fre quent with 12 kilograms worth of groceries catapulted over my shoulders, soup cans and creamer knocking against each other in assorted totes tearing at the bottom.

But I don’t tell Mom my back is rounding, because she’ll warn me about menopausal headaches to antici pate from holding tension at my neck. And I won’t tell Baka because she’ll throw me into yoga and a child’s pose as soon as I reach her for the summer, inhaling and exhaling into the floor of a mirrorless studio until blood rushes to my head.

In my suitcase, I’ll be carrying gifts that convince Baka it’s worth it to be apart. On the plane ride back, my side pockets will be stuffed with blouses and skirts that make me feel like a lady, and my tongue will untie itself from massacring this language that is pushing me toward generations of moms.

To be of these women is to always greet them with bags full of stuff. Because I’m never visiting for the day, no, I’m always staying a while — or at least until I can start to feel the tension I’ve put into me finally unravel itself down my spine. The change from knowing myself that happened away from this love, away from this hier archy of funny deviations from maternal tradition, melts into, “I can stay one more night” and “I’ve saved room for another serving of goulash.”

Last week, I tried on Mom’s and Baka’s clothes that found themselves in a pile slung onto my bed, breathing weakly so I could run my hand over ribs and drink in the emptiness. I felt pretty. The women in my family are quite small.

Then it was 1 a.m. and I slept for four hours, waking up the next day to get on with it — bags under my eyes, bags over my shoulders, feeling shitty for feeling com plete though I haven’t called home since September.

Can I show you I care so much? I’m sorry I don’t feel the urge to tell you I’ve been living just for me — it’s

because I know you can’t do the same. You’re in a proxy network of selfless action, I’m a satellite runaway.

In my bag, I’ve got everything I need to clean up after myself, and in your bag you have extra tissues because you know I didn’t bring enough. In those Superstore tote bags, you come home with a week’s worth of meals for four, not one.

Now I’m retreating and coming back — once, twice a week — sweeping out the door in rushed hushes because I’m full and fed (up).

I’m a nomad and nobody to anybody. I’m everything if everything goes back to a maternal hunger all knitted into dirty laundry and hesitant “I miss you”s and legs crossed over one another on the couch in an attempt to feel found again. Where I’m superimposed on women devoid of purpose unless I’m home for dinner.

words by Ava McAdam-Beder

illustrations by Abbie Lee

I wore my hair in a slicked-back bun today, a style my mirror hadn’t seen on me in years. A part of the process will always be muscle memory — a counter-clockwise twist and four pins marking the shape of an X, one of the many traditions instilled in me through years of competitive dance.

Suddenly, I was 14 again, watching myself through the studio mirror.

Growing up as a dancer complicates the already complicated process of growing up as a girl. You learn to base your ideas of success on century-old expectations, encouraged by seemingly century-old teachers. You spend most evenings between four studio walls, your reflection following you with every turn. You are never just a dancer — you assume the role of the ruthless spectator, evaluating and measuring each ‘imperfection.’ You no longer view your body as simply your body; it is a machine, a medium and a commodity.

Your fears, doubts, hungers and pains are concealed behind the wings of the theatre’s stage. There, on that sacred sprung floor, you must demonstrate the real art you have practiced your whole life — making everything look easy, effortless, graceful, comfortable.

Under the blistering spotlight, your pain is turned into another's pleasure. Your leg floats upward for an eternity, you catapult yourself into the air and land without a sound and you complete

a triple pirouette perfectly — all while lifting your chin and projecting a grin to the eager audience.

And when you do achieve perfection, the crowd’s explosion of ‘ooh’s and ‘ahh’s make every second of struggle worth it. That invigorating power can make you forget about the shin splints, bunions, headaches and sprains.

In that moment, you are nothing but beautiful.

Esteemed competitions have now been replaced with daily performances. I chassé through the city with an upright posture accredited to years of ballet class. I walk with grace, taste and lingering knee pain. I mask my dissatisfactions with a smile, as I’ve been conditioned to perpetually please. An invisible audience looms over me with their piercing gaze, perceiving my every move and carefully calculating my worth.

The challenge now is to navigate my own path, without clinging to the title of a ‘dancer.’ Who am I without the headline that I once understood as the pillar of my identity? I have grown out of my shoes, my tights, that phase of my life.

But the remnants of my old self are still alive inside of me — in my competitive nature, my fear of criticism, my shoulders. In my warped perception of self that has become intertwined with the pursuit of excellence and in the invisible audience that sits at the back of my brain. In my perfectly slicked ballet bun. U

Ihavealways been attracted to — and easily distracted by — pretty people.

This is precisely why I will always be a staunch defender and lover of the pop girlies, like Selena Gomez and Sabrina Carpenter.

Female pop icons have some of the most power in popular culture — they boost local economies on world tours, influence fashion and write the soundtrack to people’s coming of age.

Many of these women also become a highly revered image of the ideal woman, which complicates things for the once-little girls like me who didn’t feel as “tanned, toned, fit and ready’’ as Katy Perry in her Daisy Dukes.

What initially drew me to the fantastical world of pop stardom was Disney Channel’s all-time classic Hannah Montana

Hannah Montana’s closet is to Gen Z what Cher from Clueless ’ closet was to millennials: the dream. The show made Miley Cyrus into a brand for little girls — our parents happily bought Halloween costumes, PJ sets, jewellery and singing dolls. However, when she began to break out of the child star mould with her iconic 2013 VMAs performance, the media turned on her, and so did our parents.

I was 10 years old when Miley entered her Bangerz era. Hannah Montana had been off the air for two years, and I remember feeling the same kind of surprise and shock that the rest of the world felt when they realized who she had become.

She was done with the PG outfits I had become accustomed to seeing her in. Besides the revealing clothing and the twerking, I remember my mind being blown by the imagery in the music video for “We Can't Stop” — there was fake blood that looked like Pepto Bismol, dancing stuffed animals, montages laced with sexual undertones and lyrics I could not for the life of me understand at that age, like “Everyone in line in the bathroom, tryna get a line in the bathroom.” I now understand that the second line was not referring to waiting to use the soap dispenser.

Despite it all, I didn’t necessarily think anything Miley was singing, wearing or dancing was bad or shameful until other people told me it was.

Now, looking back at videos of Miley during this time, I view these things as her asserting her agency. Her entire career up until that point had been made to cater to little girls, but now her contract was up, and she could start to make music that reflected the stage of life she was experiencing. Miley, like all 20-somethings, was asserting her sexuality and womanhood. This change was normal, but not palatable to everyone who expected her to stay the same forever.

Around the same time, Katy Perry was taking the pop music world by storm.

Like Miley, Katy had to perform femininity — she made girls worship her purple hair and sparkly eyeshadow. She always showed just the right amount of midriff, and carefully calculated the cleavage showing in her candy bra.

Because Katy was more accommodating to the ‘male gaze,’ her sexuality wasn’t policed in the same ways artists like Miley or Lady Gaga were. She continued to be marketed to children, while Gaga and Miley were seen as an abomination to precious young minds.

Katy made many songs with subtle sexual references, and songs like “I Kissed a Girl” were hits back then. Now, more and more people seem to be realizing how it sheds a strange light on Queer women by sexualizing their relationships and treating sexual activities with other women like a game, of sorts. It’s especially uncomfortable coming from someone like Katy, who often seems to skirt around questions about her sexuality.

This was confusing for little girls like me who were figuring out their gender expression and sexuality under the influence of female celebrities. In reality, things like Lady Gaga’s neutral answers to speculations regarding her genitalia and gender were in service to her younger listeners.

None of these artists are obligated to come out to anyone, but it does leave a weird taste in your mouth when you think about how reluctant people like Katy were to identify with the communities off of which she was profiting.

Let’s fast forward to today.

At 21, I’m still keeping up with all the classic pop girlies, but am embracing a new generation of performers like Raveena Aurora and Chappell Roan. Chappell is breaking boundaries, and among other mainstream pop girls, I think she is an awesome anomaly. In terms of expressing femininity, sexuality and agency, she is doing it with pride — and while she has more than a few haters, she is succeeding. I’d like to think the younger me would love Chappell’s outfits. Her artistic choices are dynamic — she opts to perform in more revealing, drag-inspired one-piece bodysuits, and even tried out a suit of armour (inspired by either Julie D’Aubigny or Joan of Arc — the debate is ongoing). They’re sometimes sexual, sure, but they’re always in service of her music and her message; they uplift marginalized communities, especially the Queer community, by paying homage to important cultural and historical references, and she always gives credit to her inspirations where it’s due.

In lieu of coy references to experimenting with women, Chappell’s songs include nuanced depictions of the lust, heartbreak, love, resentment and regret that representations of Queer relationships deserve. While art about discovering who you are by experimenting may also be important, it shouldn’t discredit the experiences of marginalized communities in the process. And Chappell isn’t afraid to talk about her sexuality — by describing herself in these ways, she’s decreasing the stigma around words like “Queer” or “lesbian,” and showing young girls who are figuring it out that it’s okay to identify in these ways.

And now Chappell is being played on the radio and all over TikTok. The representation that was once impossible to find is now inescapable.

If the fate of many child stars, like Miley, is proof of anything, it is that pop stars should not be used to shape children’s minds. They should not be propped on a pedestal and used to project an image of the ideal, tame, young woman.

However, they do impact the culture. So the best thing they can do is be themselves. The culture will have no other option than to adapt and evolve.

There are so many kids, especially young girls, trying to figure out how to be, so seeing these powerful people wearing what they want, and saying what they want, will make all the difference. U

On a small island inside the internet — governed by @ joan.of.arca , Binchtopia and Ottessa Moshfegh — lives a world of literate young women. They exchange Sylvia Plath novels for coffee and diet Pepsi, berate the islands around them and build homes of books and Jeff Buckley look-alikes. Nightly, they sit around fires of torn Ayn Rand novels, burning them for warmth.

The roots of the “thought daughter” phenomenon are actually quite pure. Though often misconstrued into discussions of aestheticism, a thought daughter is really nothing more than an online depiction of the thoughts and feelings of a complex “real girl.”

The term morphed out of a joke within a joke of the tired TikTok trend, “Would you rather have a thot daughter or gay son?” — a question most internet users have heard in those uncomfortable streeter interviews.

I beg you, do not go down the Reddit rabbit hole for this question. The current status of the thought daughter has become quite separate from its originator, now used to reflect on the thoughts and inner workings of women and femmes.

The “thought daughter” characterization was no more than a public call into the void for other young women with deep attachments to specific literature and media who are known for “feeling deeply.”

Most likely this is my interpretation, so you’ll have to forgive me. But in my eyes, I see it as a common understanding of post-teen melancholia — we are no longer “woe is me” 13-year-olds who have just read

Twilight or watched Lost in Translation, but we still hold many of the same attachments to those characters. When we engage in the belief that “nobody thinks how I think,” “nobody understands how I feel,” we choose to establish ourselves as outsiders. It’s much like how a socially awkward boy who prefers Star Wars to social engagement will in some ways see himself through that lens forever.

Humans are not so complicated after all, and if you (or I) at 14 believed ourselves as reincarnations of Joan Didion — the silent viewer, the holier than thou, the mighty vessel into the world — we might always see ourselves that way. My apologies to the thought daughters in the Instagram reels, but men also get emotional looking out of train car windows.

It’s often depicted that a woman or femme in this archetype is highly introverted and has developed an ability to repress their feelings. And it is within the community of old female writers, archive interviews and conversations with other young women like them that they feel represented.

Let’s zoom out a bit though — aside from general personality differences, why do some women brand themselves as intelligent, complex thinkers and others do not? Why is nobody calling a male introverted philosophy major who reads Bukowski a “thought son”? What makes this branding only applicable to not only women, but one version of a woman?

What happens if we take the thought daughter away from its associated authors, musicians and movie char-

acters — is anything left aside from general feeling?

In essence, the thought daughter holds one mental framework: deep reflection. And don’t we all do that?

From one thought daughter to (possibly) another, I think we need to give everyone more credit. We can all manage complex emotions, be introverted at times and — listen hard for this one — think deeply. If we don’t want to end up in another iteration of the “not like other girls” mentality, we need to notice the complexities in each person’s individual experience.

This is not to say you can no longer read Patti Smith or Eileen Myles, and yes, they can still be aspects of your identity. You are still allowed to see yourself in Clementine from Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind — too much damage has been done from her to reverse that, anyway. Yes, you can still watch Lady Bird (and can still prefer Greta Gerwig’s earlier work). Identifying ourselves through interests is not the debate in question, rather that we should acknowledge how these feelings are not independent of this brand of young girls turning into young women.

While we can write and read moody books on deep reflection, we do not own this emotion. That is the beauty and truth of complexity. This brand of female characters may never go away, and we may continue throwing pages into the fire to warm our island. But we must admit that someone does not have to look like us or read like us to think like us.

I’ll hold your hand when I say this — you and I are not so unique after all. U

Despite the media-imposed stereotype that ‘girl’ friendships are characterized by petty fights and falsity, close personal relationships are a staple of girlhood. From BFFs and playdates to a support system to get you through high school drama, everyone needs a community they can trust and find comfort in.

So when it feels like everyone you know is telling you to join clubs in university, maybe they’re on to something. Clubs can distract you from the lonely essay writing you’ve been doing in your dorm room lately, but they can also be a way to connect to your femininity in ways you haven’t before.

The tie between clubs like UBC Knit and Sew and Her Fitness is not solely a focus on ‘feminine’ interests or targeting a specifically female audience, but also their emphasis on community and supporting one another.

When UBC Knit and Sew President and fifth-year speech sciences student Mia Cervas advertises the club, she makes sure to highlight the community you will form — along with the promise of accessible yarn, of course.

“My selling point is you can learn a new project and you get to know people in the community.”

Even if knitting and sewing isn’t for you, the club emphasizes the sense of community people find in their knitting circles — you can stop by for a chat, and maybe even pick up a few practical skills along the way. Whether you’re working on a project or not, it’s a place where members find people with similar interests.

Vice-President Lyn Scatchard, a third-year sociology major, thinks Knit and Sew is a social club.

“It’s a lot of fun to just have a reason to sit down, hang out with your friends, get away from midterms and exams and all that.”

Knitting, sewing and crocheting have traditionally been feminine chores, hobbies or even occupations. But according to Scatchard, this gendered perception not only should be disappearing — it is.

“Things like knowing how to repair a hole in your

clothing, or how much effort goes into making the clothes that you wear — those are good skills for anyone to have,” they said. “We do have a lot of … women as members, but there’s also a good [number] of Queer people … or even just men who want to explore [what] they’ve never been introduced to.”

Though many boys were not taught these skills when they were younger, that doesn’t stop interest from forming as they grow older. For men, knitting and sewing typically aren’t presented as activities they can pursue, Scatchard said, “so when they get to university, they’re experiencing all these new things in life, and they’re like, ‘Maybe I’ll pick up knitting. Maybe I’ll learn to crochet.’”

Cervas and Scatchard see people of all gender identities exploring their femininity through the club, noting how some members take up crochet to create cool outfits for their DJing gigs.

“That’s a way that they are engaging with a feminine type of craft, but also … it’s just another aspect of something that they do,” Cervas said.

While UBC Knit and Sew is crossing boundaries in defining who can engage with historically feminine practices, Her Fitness is striving to celebrate femininity in a different way — by creating space specifically for women in the gym, which is typically a male-dominated industry. Members work with execs to develop a personalized fitness routine and learn how to navigate the gym in a low-stress, beginner-friendly environment.

The idea for the club grew out of feelings of frustration shared by friends Hamrah Riyaz and Amreen Aulakh, who had both experienced obstacles in their fitness journeys — obstacles Riyaz knew were “not the same at all for men.”

“Fitness should be accessible to anyone, and especially in today’s society … there are a lot [more] fitness concepts marketed more towards women,” Riyaz said. Despite positive changes in the fitness community, it’s still difficult for women to break into something

they’ve historically felt excluded from.

“Prior to going, I was on YouTube all the time, perfecting my form and watching so many videos of every machine in the gym just so I would feel confident enough to step in,” Riyaz said.

“I really had to come out of my shell and just force myself to be so uncomfortable being there and being scared about not knowing what to do, or if people are judging me. You just feel very vulnerable.”

From this feeling of vulnerability came a desire to make this experience easier for other women by building up their confidence and eliminating variables that make an already intimidating thing even harder.

“We really wanted to break down those barriers,” Riyaz said, describing how making events financially feasible to attend was a priority. “We don’t want cost to be a reason why women aren’t able to access these resources.”

Going into this academic year, Riyaz and Aulakh hope to focus even more on nutrition and building healthy routines — and maybe even a foray into teaching weightlifting and powerlifting, by way of collaborating with other clubs — while maintaining the incredible support and community they developed last year.

“If we were able to pull this off… it would be such a rewarding experience. I think it’s just so important because I don’t think there’s another club that does the same thing we do.”

At the foundation of Her Fitness is girls encouraging other girls — to start something they will enjoy, to find the confidence to do something new, to make friends and take on leadership positions.

And at the base of femininity is a girl being there for another girl, or a willingness to engage with practices that are tied to experiences of womanhood.

So join a girls’ club. Because a girls’ club is a club that supports, nurtures and loves. A girls’ club is not a club full of girls (though it can be) but any club that makes you feel less alone. U

words by Erin Greenwood photos by Guntas Kaur

Iwas10 years old when I got called “teacher’s pet” for the first time. Perplexed, I pushed my big square glasses up my small nose and asked, “What does that mean?”

“It means you’re a goody-two-shoes, and you can’t play with us.”

That afternoon, once recess was over, I realized that other kids looked at me differently. From a young age, I knew I loved to learn, and I knew I was good at it. My mother taught me to read when I was three years old. Every night we would curl up in my trundle bed and read Peter and Jane until I could recite my vowels and configure my consonants. When I started at elementary school, every day was an opportunity to fill my eager brain with as much knowledge as possible, excited to go home and tell my family everything I’d learned.

It had never occurred to me that other kids watched me raise my hand during lessons and thought, “Erin is such a know-it-all.”

Women and girls are the smartest people I have met in my life. Both academically and interpersonally, their empathy and willingness to learn is what makes them extremely well-rounded and attractive people. While feminine intelligence is romanticized and admired among women, it is often picked at and demeaned by the rest of society. Women can only be smart if they’re quiet about it.

Why are women expected to contain their intelligence? How many girls conceal their cleverness because they’re ashamed to show it off? How many young women face challenges in proving themselves to the academic world?

I was 14 when I decided to be quiet. My contributions in class declined and I concealed my excitement — my intelligence became my biggest secret. Kids at school thought my eagerness was obnoxious and over-

bearing. They thought I should learn a thing or two about humility, so I swore myself to silence.

I was desperate to escape the names that had followed me since I was 10. I didn’t want to be a “teacher’s pet” anymore — I wanted to be cool. Being smart was only cool if you pretended you weren’t, as if intelligence was meant to be a hidden talent. So, I pretended. I stayed quiet.

It was my first year of high school and I was standing in the smoke pit, a math textbook under my arm, when someone said, “Woah, you’re taking pre-calc?”

“Yes.” I stood like a deer in headlights.

Cigarette hanging from the corner of his lips, he snorted. “What are you, a know-it-all?”

Women are subjected to the restraints of societal expectations. Existing in a world dominated by the patriarchy makes it feel impossible to express femininity — things as simple as wearing a skirt, stating an opinion or choosing to carry your pre-calculus textbook results in being sexualized, interrupted and demeaned.

How many times do girls adjust their skirts throughout the day? Why don’t people listen to what a woman has to say? Am I really flaunting my good grades by carrying around a textbook?

I was 17 and quiet as a mouse. There were only 6 girls in the classroom, outnumbered by the 24 boys who were more interested in playing ball than paying attention. After I finished an exam first, I overheard someone call me an “English nerd.” Even though I’d heard the term a million times in my life, I couldn’t believe the hypocrisy of the boy who said it. He was top of our class! He had spunk, wit and was admirably smart. Everybody thought he was dedicated because he spent his afternoons polishing up papers. Nobody dared call him an “English nerd” or a “know-it-all” or a “teacher’s pet.”

Finally, I understood that being smart is cool — but only if you’re a guy. Often, boys are praised for their cleverness while girls are picked on for it. Boys can shout their intelligence from the rooftops while girls can only whisper.

As a teenager, I shied away from being too eager because I didn’t want to be overbearing. Cool girls are quiet girls. So many years of my academic life were wasted on abiding by society’s misogynistic double standard. Looking back now, I wish I could grab 13-year-old Erin by the shoulders and tell her that it is a privilege to be smart! Fuck being quiet!

Most of our patriarchal society cannot handle an educated woman. While male intelligence is inspiring, female intelligence is intimidating. A lot of people literally hate to see a girlboss winning!

Trying to keep my intelligence a secret for so long ended up pointless anyway, since my peers still called me names. At the end of the day, this teacher’s pet was the one who moved to the city to pursue an academic career.

I am now 18, and one of the incredibly intuitive, creative and extremely well-spoken women who attend UBC. It is so refreshing to attend a class with more than six girls in the room.

Embracing feminine intelligence creates a welcoming and inclusive environment — one that I am proud to be a part of. Romanticizing education is beautiful. Buying a pumpkin spice latte, touching up lip gloss and studying at the library until it’s dark outside are all fantastic parts of being a smart, productive and capable woman. Changing the societal narrative to empower eager young girls would help us feel more confident, ensuring a future of educated women.

To all the know-it-alls and nerds I walk past every day: embrace it. Shout it from the rooftops! Be proud to be intelligent and be even prouder to be a woman. U

words by Roz Golshani

i am a fruit tree

but a delicate rose is all you should see — all i want you to, at least. it would be nice to be seen as sweet with something to give, perhaps a peach. more than just sweet with enough to keep going, a whisper from me and your words would start flowing.

i am a fruit tree, but i’d rather a rose. seen as, at least. and i wouldn’t read prose i’d sit pretty and quiet and you’d only see me if your eyes would comprise it. a look around, and if i’m right, just intricate, just light maybe you’d pick me. just quiet, just there a rose doesn’t rustle or tustle your hair isn’t fragile, doesn’t squish and when it pops, it doesn’t stick a rose knows to not, or you’d think, without thought. but i’d like if i could be a fruit tree with something to give, without having to be bitter or having to be sweet. i wish it was right to simply be. U

words by Roz Golshani

she is of passing notes twisted games of telephone misheard & missaid result of dropped clay “oops” & men in disarray take solace “pretty” nice on the out clean of the skin so seek to taint — wait, win. she is misshapen shattered and glued give her a year kintsugi anew she is the heard told words to break through and return unkiln unmelt. U

evewords

by

Abbie Lee

good lord, what have i done to be so far from you?

to be independent, assertive, strong, my own leader, a model. without a doubt, i did everything right i am the judge, i am the law but above all, i am a piece of him from flesh and earth, i’ve done everything in my power to be him because it was Her in the garden

to be this

when i could’ve been sweet like a peach, bruised like the skin of a supple babe, i could’ve been gentle like a storm, or emotional like a streetlamp in the dead of night humble for you, tender for you, devoted for you when they told me He was supposed to be love but he wasn’t

what if i was fruit to a spirit that lied to all my brothers, ripped apart my sisters, and liberated my mother?

when She comes back and tells me how to be, in Her image i wonder — will it be enough? U

illustrations by Abbie Lee

Breaking into the Vancouver music scene was when I really began to grasp the gravity of another woman’s word.

I’ve spent hours in bars playing shows, usually waiting for the perfect moment to sneak away to the bathroom for a few moments of silence. As I sit there, I take the time to look over the notes scrawled in Sharpie all over the plastic toilet paper dispensers and stall doors, most of them consisting of names and warnings to avoid those individuals at all costs.

My bandmate sends a screenshot to our group chat. It’s an Instagram story with a photo of a guy who had worked at one of our shows, and paragraphs upon paragraphs of text detailing his various alleged crimes against women in the music community. We choose to believe this stranger and vow to ourselves to never work with the man again, knowing what we do now.

We need to have this trust, even though the stories may never actually be proven. Because when you’re a woman, it’s almost always a man’s word over yours — and believing in gossip is often the only way to protect yourself.

Dr. Alexis McGee is an assistant professor of research in the School of Journalism, Writing and Media and the author of From Blues to Beyoncé: A Century of Black Women’s Generational Sonic Rhetorics, which explores how women — specifically Black women — have mobilized voice.

“Through songs, through writing a voice in newspapers or pamphlets or public speaking, autobiographies — the ways in which a voice permeates the world around us and helps us facilitate and communicate knowledge … sometimes get overlooked … especially in a patriarchal, heteronormative, white, European framework of society and culture,” McGee said in an interview with The Ubyssey

Another example is gossip, which, according to her, was first introduced as a feminist practice around the 14th century, when “salon networks [were] used to mobilize information, to go against, resist [or] share information about society and the constructions that are placed upon women’s bodies,” McGee said.

Some conversations — whether positive or negative — revolving around another person without their knowledge fall into the category of gossip.

But for most women throughout history, it has primarily served as a form of resistance since it’s a covert way of organizing movements and planning strategies to stand up to injustice without alerting the oppressor.

“We often see gossip being mobilized to sort of make inroads or push against those boundaries that have meant to exclude women from everyday society,” she said. “As a practice, we see [it] during that time as a really effective way to get information, to get us into different social standings, to get us out of particular positions.”

“as a practice, we see [it] during that time as a really effective way to get information, to get us into different social standings, to get us out of particular positions.”

— Dr. Alexis McGee, School of Journalism, Writing and Media assistant professor

When fifth-year cognitive systems student Georgia Lamb was a teenager, she loved the movie Mean Girls and magazines like Tiger Beat, with splashes of pink, cutouts of celebrities and personality quizzes.

She noticed how media geared toward younger women usually talked about navigating friendship issues and bullying — a guide, of sorts, to the psychological battleground that is being a girl. And gossip was the constant: an ever-present phenomenon that drove stories forward, and usually in a negative way.

“There are all these different types of shows that mobilize gossip and to some extent, for better or for worse, normalize the gendered idea of what gossip is. It's always women trading in secrets behind the scenes to make sure something gets done or [not],” McGee said.

“It shows the power differentials in those ways, but it often doesn't examine why that's happening, or the implications of what it means in the social [and] cultural [or] historical context for women to be able to do that sort of work, and what does that mean for larger feminist populations.”

The ways gossip was presented were often oversimplified, Lamb said, since it almost always seemed to be used “for the sense of ridicule.”

While the media she consumed wasn’t quite able to capture the nuances of gossip — how it can help a situation, not just hinder it — when Lamb got older and entered university, talking about people with other girls became a common way to encourage safety and solidarity.

“I've seen more of the utility of trying to protect other people ... trying to look out for each other — that is where it gets a little bit more difficult to discuss, a little bit more difficult to navigate.”

“You'll have the usual gossip like, ‘Stay away from this person because this, this and this,’” Lamb said. “There's both a lot of potential for good and a lot of potential for harm, because that is what tends to spread a little bit more easily and cause some sort of impact, whether for better or for worse. From what I've seen, it’s mostly been for better.”

An unspoken rule of girlhood is keeping other women safe, regardless of whether you know them or not. There’s an expectation that women warn each other of potential danger — but we rarely see positive impacts from publicly speaking out, since our stories are shut down or denied by a patriarchal society.

By writing a note on a bathroom door or spinning the incident into a bite-sized piece of gossip — there are ways to get the message across to the people who need to hear it.

“One thing that I noticed I used it for was when discussing matters that were more personal or harmful to me with people who I wasn't super comfortable sharing an entire story or an entire difficult instance [with],” Lamb said. “Something that I found to be quite powerful was to state opinions about a person in that kind of gossipy tone.”

There’s power in subtle or secret communication, which is exactly why women are discouraged from doing it, particularly by those who feel most threatened by it.

“I think that's why I think people might want to categorize [gossip] as dangerous or negative or bad. But we often focus on that, and not the life-giving trends or tools or capabilities that [are] built within those systems,” said McGee.

“It's a method to help us move out of really oppressive or violent terrains.”

But how do you decide whether or not the things you hear are true? According to Lamb, she usually does believe people, but is more likely to trust someone she’s already close to, which can pose some problems.

“There's definitely a psychological explanation, like you are more likely to trust those within the circle, and that is another element of harm,” Lamb said.

“Whether or not that spreads, whether or

“gossip has been the effective outlet to say that we are capable in these ways, and here’s how we’ve got to impact change.”

— Dr. Alexis McGee, School of Journalism, Writing and Media assistant professor

not you are believed, can depend a lot on where you kind of stand in that social sphere … It [is] separate from a larger hierarchy or a larger social structure, [but] it can also be an entirely new social structure.”

The intricacies of gossip among women become even more complex when looking at how they’re influenced by the intersections of identity, like race, sexuality and class. According to McGee, racialized women are believed even less, causing them to face more barriers than white women.

“The use of gossip is intensified because of the intersectional ways in which Black women's bodies have been precluded from conversations, and we're not offered the same level of negotiation of power than other more heteronormative bodies are,” said McGee.

“We have to be more strategic in the ways that we gossip, or the ways that we apply gossip, to our need to survive. It's not just about being able to get into the room. Often, it's about being able to make sure we change the policy so everybody can get into the room.”

Lamb is aware that as someone who does not identify as a person of colour, she needs to be mindful of how her positionality influences which ideas she believes — and for her, this involves keeping an open mind and taking the time to hear people out.

“[You need] a strong inclination and a strong willingness to believe and listen, because of [the] understanding that the structures in power will try and speak louder than whatever this other person is saying,” Lamb said. “I need to adjust that bias accordingly, because I know that it's very easy to prioritize that existing structure.”

Within this intersection, negative connotations around gossiping can become even harsher due to the way marginalized communities are seen. For example, Black women are pushed to the side of social justice movements, despite the unique ideas and experiences they bring to the table, because of their race.

“It's going to be hard to disconnect the negative connotation of gossip,” McGee said. “Because it has so much power to change or sway wherever the decision making is happening or to discredit somebody.”

But even through the criticism around it, gossip remains vital in many social circles, especially marginalized groups, as a network of knowledge. There’s a reason it’s lasted since long before our time — no matter how hard people try to prevent it, it’s simply human nature to share stories with each other.

“I think because of the way that society — historically, socially and culturally — has conscripted the female body or conscripted feminist practices and rhetorics, to something that's not deemed ‘important’ or ‘worthy of’ or ‘capable of,’” said McGee.

“Gossip has been the effective outlet to say that we are capable in these ways, and here’s how we’ve got to impact change.”

U

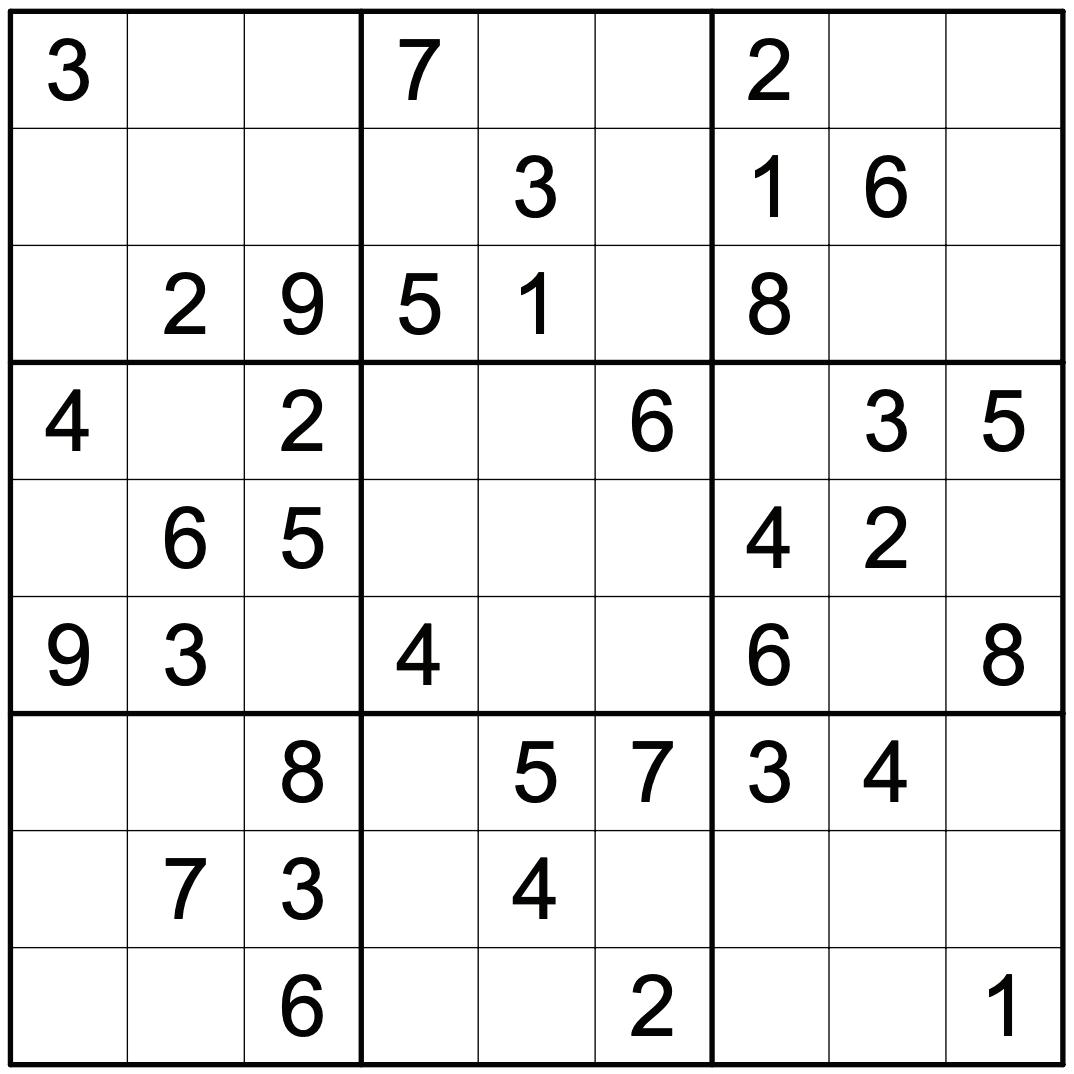

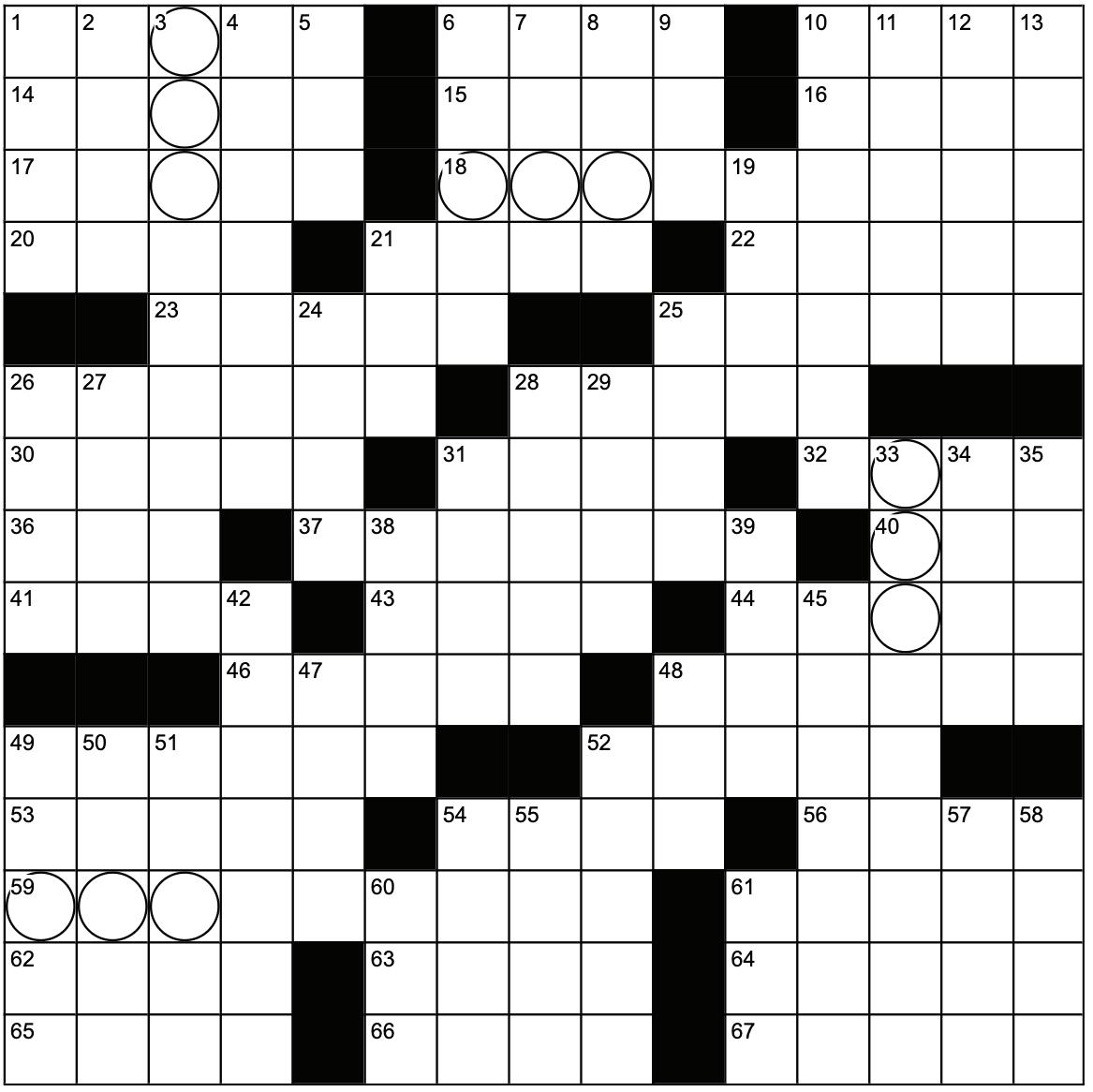

1. TikTok sound, “4_____.” 6. Clean up 10. Lion’s share 14. Hersey’s “A Bell for ___” 15. “Tosca” tune 16. Director Preminger 17. Geeky 18. Like kimchi or sauerkraut 20. Lady’s title 21. ___-majesté 22. Lieu 23. Street Fighter character mispelling 25. Rudely sarcastic 26. “Vincent” repeted