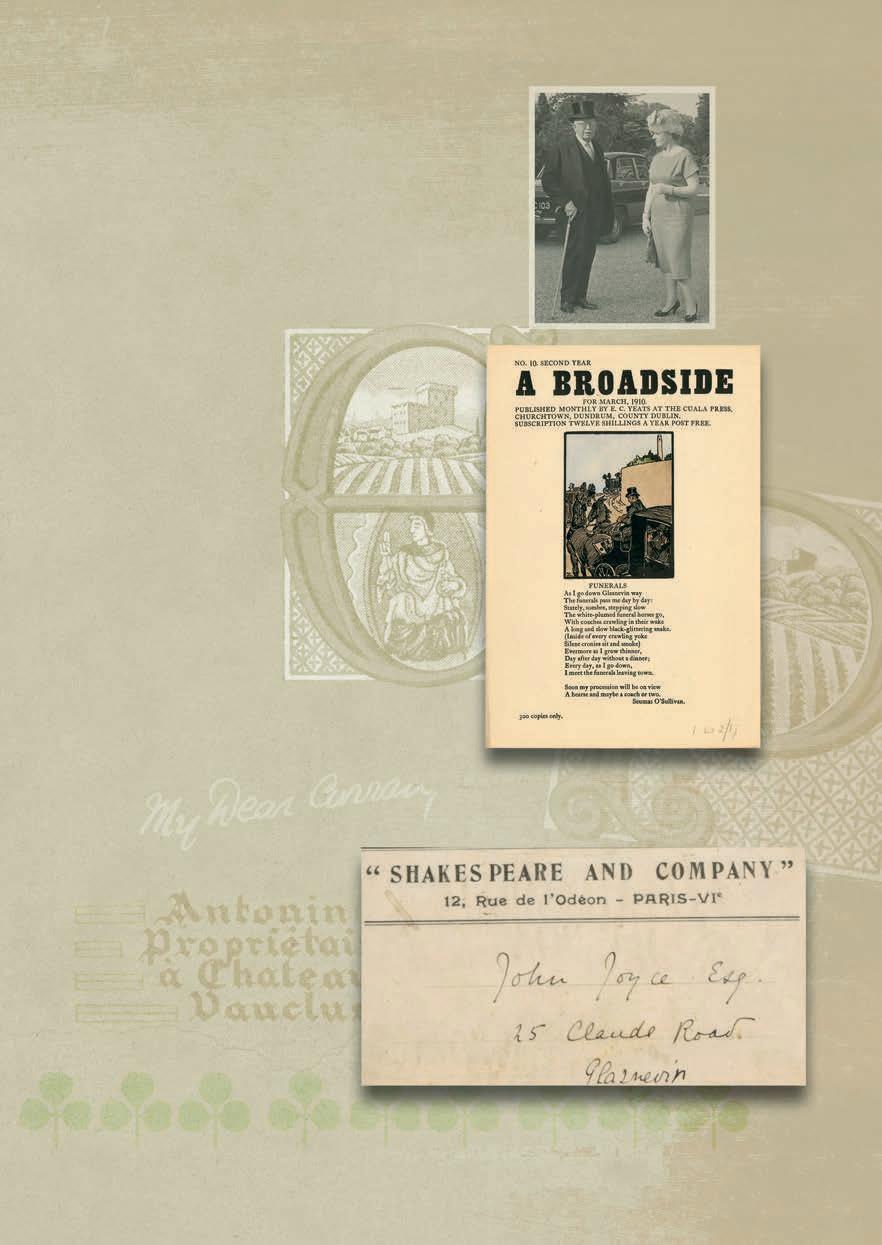

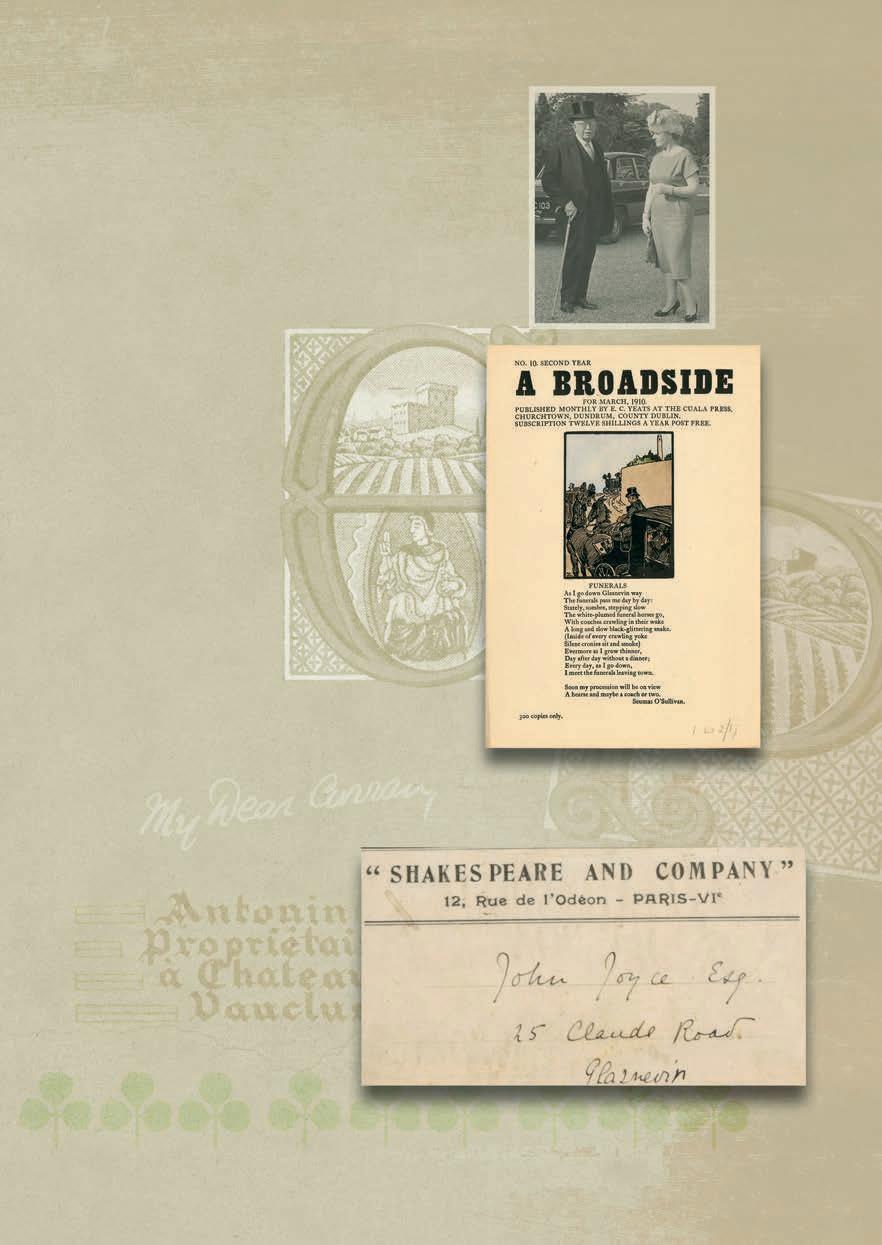

Seamus O’Sullivan’s “Funerals.”

Constantine Curran/Helen Laird Collection, UCD Special Collections (1.w.2/1j).

MacNeill taken in 1962. Tierney/MacNeill photographs, Papers of Michael Tierney (1894–1975) UCD Archives (IE UCDA LA30); A Broadside from March 1910

Collections , (39.K.12); photograph of Constantine Curran and Eiblín MacNeill Tierney, the wife of then president Michael Tierney and daughter of Eoin

376.).

Insets: Shakespeare and Company address label for John Stanislaus Joyce’s copy of Exiles . Constantine Curran/Helen Laird Collection, UCD Special

Main image: Saint Patrice wine label from a bottle gifted by Joyce to Curran. Constantine Curran/Helen Laird Collection, UCD Special Collections (CUR L

featuring

2

Revolutionary Dublin’s Literary Networks: C.P. Curran, Helen Laird, and James Joyce’s Ulysses

In James Joyce’s Ulysses, Richard Best quotes Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s description of William Shakespeare as “myriad-minded”; this phrase would also be apt for Constantine Curran and Helen Laird. Laird was an actor, suffragist, costumier, set designer, chemist, and science teacher. Curran was a lawyer, architectural historian, journalist, critic, book collector, and photographer. Through Laird’s involvement in political and theatrical movements, Curran’s interest in the visual arts, and his participation in literary and intellectual circles associated with University College, they amassed a large circle of friends including the Yeats family, George William “Æ” Russell, Padraic Colum, James Stephens, Sarah Purser, and most famously James Joyce. Curran’s friendship with Joyce spanned their adult lives. Joyce’s letters illustrate how, through Curran, he retained a link to his native city and Curran would later fulfil a similar role for Joyce’s international friends, supporters, academics, and biographers. As Joyce predeceased Curran, he was cast in the role of a custodian of Joyce’s legacy. The Curran/Laird collection illustrates how Curran was influential in the formation of the established image (figurative and literal) of the Irish Modernist icon. Curran and Laird married in December 1913 and from then on regularly hosted literary salons on Wednesday evenings in their home at 42 Garville Avenue, Rathgar. Much of the voluminous correspondence from Joyce and others bears this address.

UCD Special Collections acquired the Curran/Laird store of letters, papers, books, periodicals, photographs, literary and political ephemera in 1971, shortly before Curran’s death, adding to it in 2021. This rich cache of material reflects a vibrant literary and cultural scene in Dublin and showcases not only abiding friendships with important figures such as James Joyce and the Yeats family, but also artistic networks at the heart of the Irish Literary Revival. The collection demonstrates Curran’s links to each of Joyce’s four major works, in terms of their composition, publication, promotion, and reception.

On 1 January 1954 Stanislaus Joyce wrote to Curran: “While my brother was alive I sometimes heard of you. He often mentioned how useful you were to him, and I know he was grateful for your co-operation.”

3

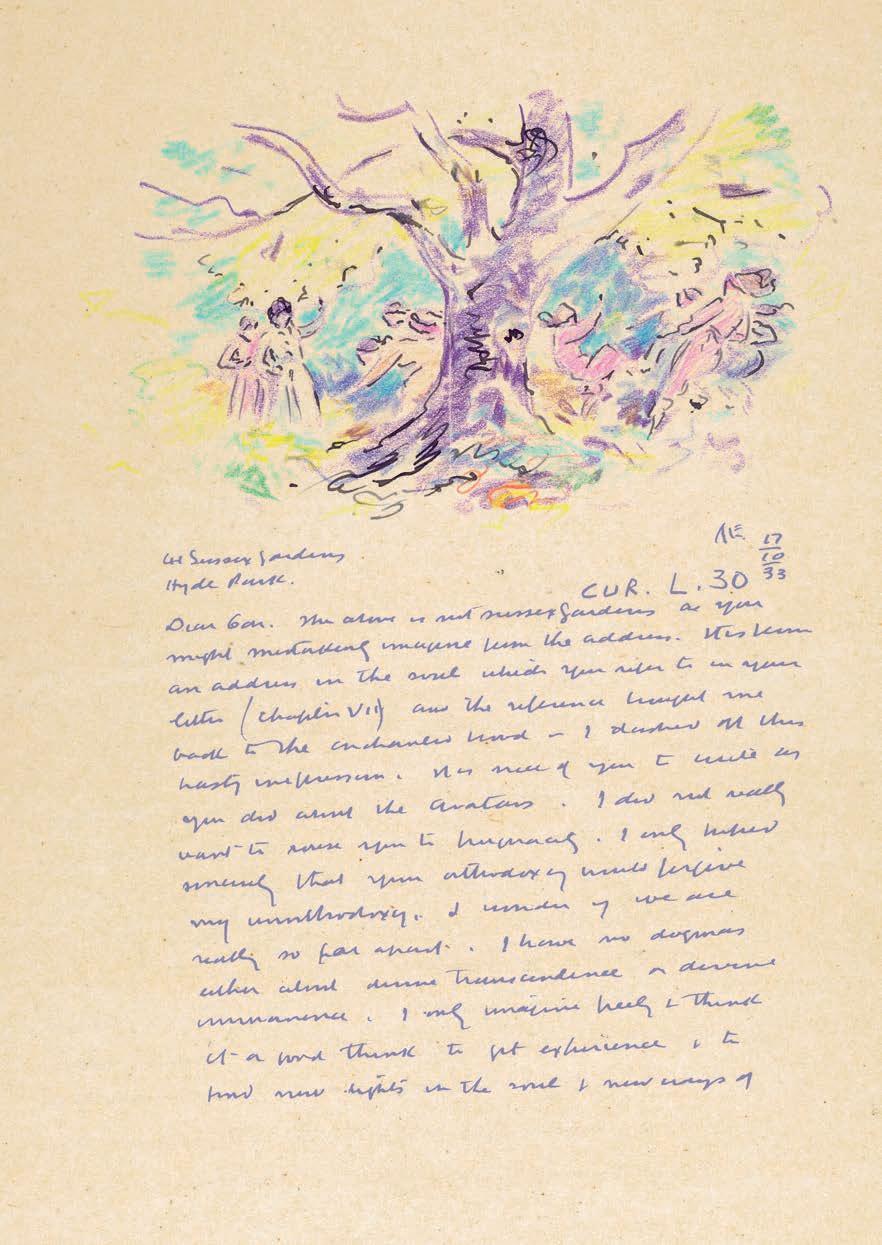

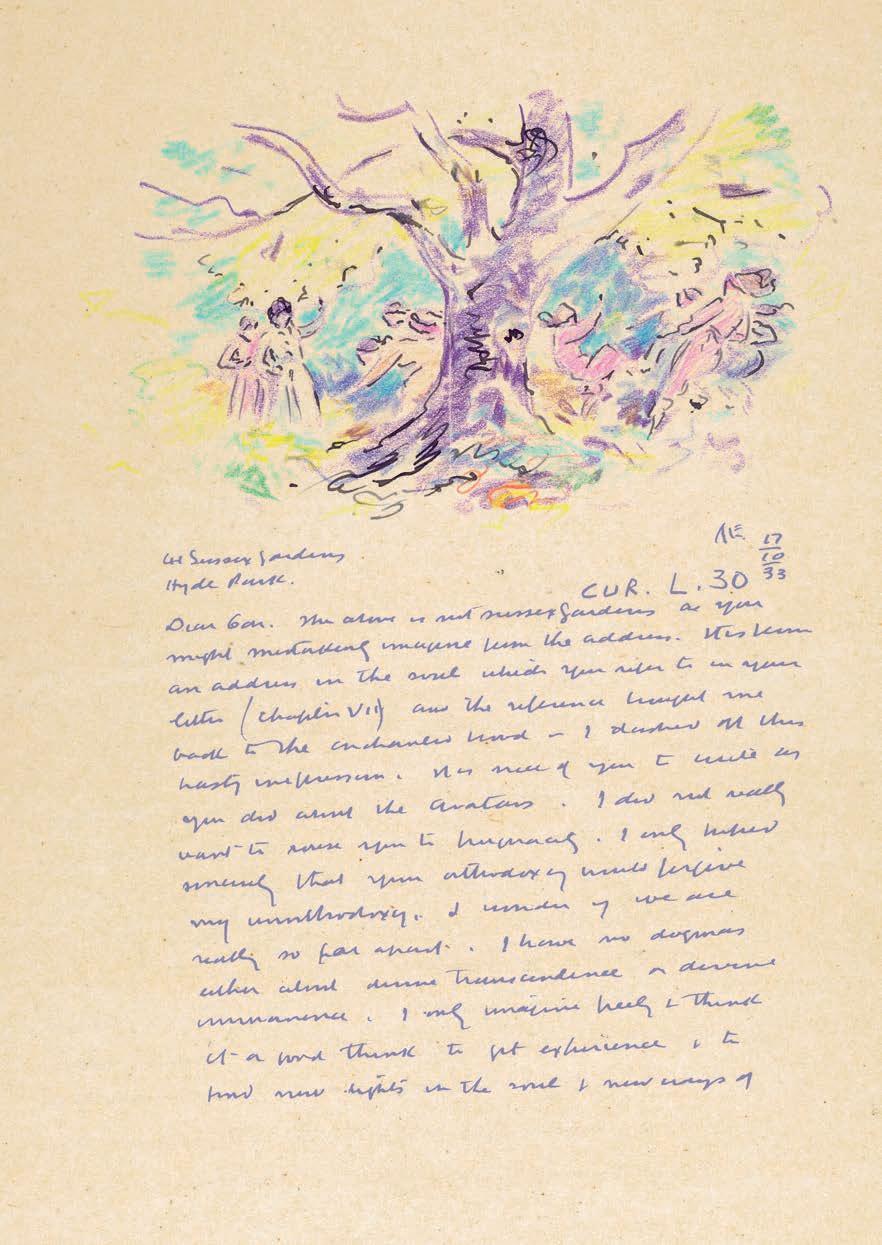

Main image: Letter from Æ to Conn Curran discussing his book The Avatars: a Futurist Fantasy . With an ink and crayon drawing at the head of the letter.

Constantine Curran/Helen Laird Collection, UCD Special Collection (CUR L 30).

Constantine Curran/Helen Laird Collection, UCD Special Collection (CUR L 30).

4

Their friendship was widely acknowledged and is reflected in Curran’s correspondence after Joyce’s death with the Joyce family and supporters like Sylvia Beach, Harriet Shaw Weaver, and Paul Léon. Curran and Laird were also politically engaged and the collection illustrates their intimacy with the revolutionary generation who overthrew British rule, established and ultimately ran the Irish Free State.

This exhibition allows people to fully appreciate the depth and range of the Curran-Joyce friendship. By showcasing Curran’s involvement in a vibrant literary scene in early 1900s Dublin, his influence on the writing of Irish literary history and status as an elucidating voice on the Revival and revolutionary period comes to the fore. As do Helen Laird’s contributions to Irish theatre and politics. Æ once referred to a literary movement as “five or six people who live in the same town and hate each other cordially.” The bitter divisions of the Civil War are well known, but the Curran-Laird collection showcases the “ingenuous insularity” and “hospitality” that Joyce identified as unique to the Hibernian metropolis.

This exhibition was curated by Dr Niels Caul.

5

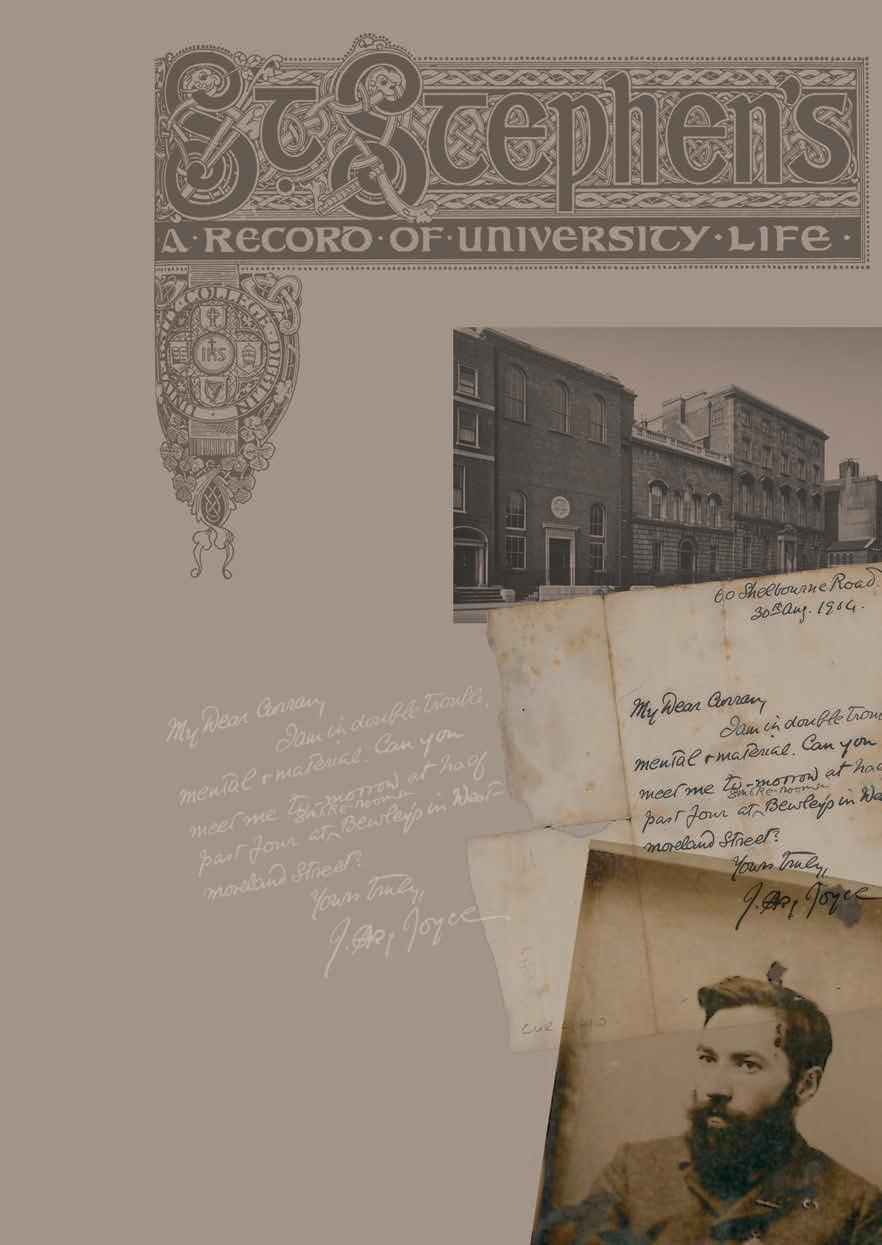

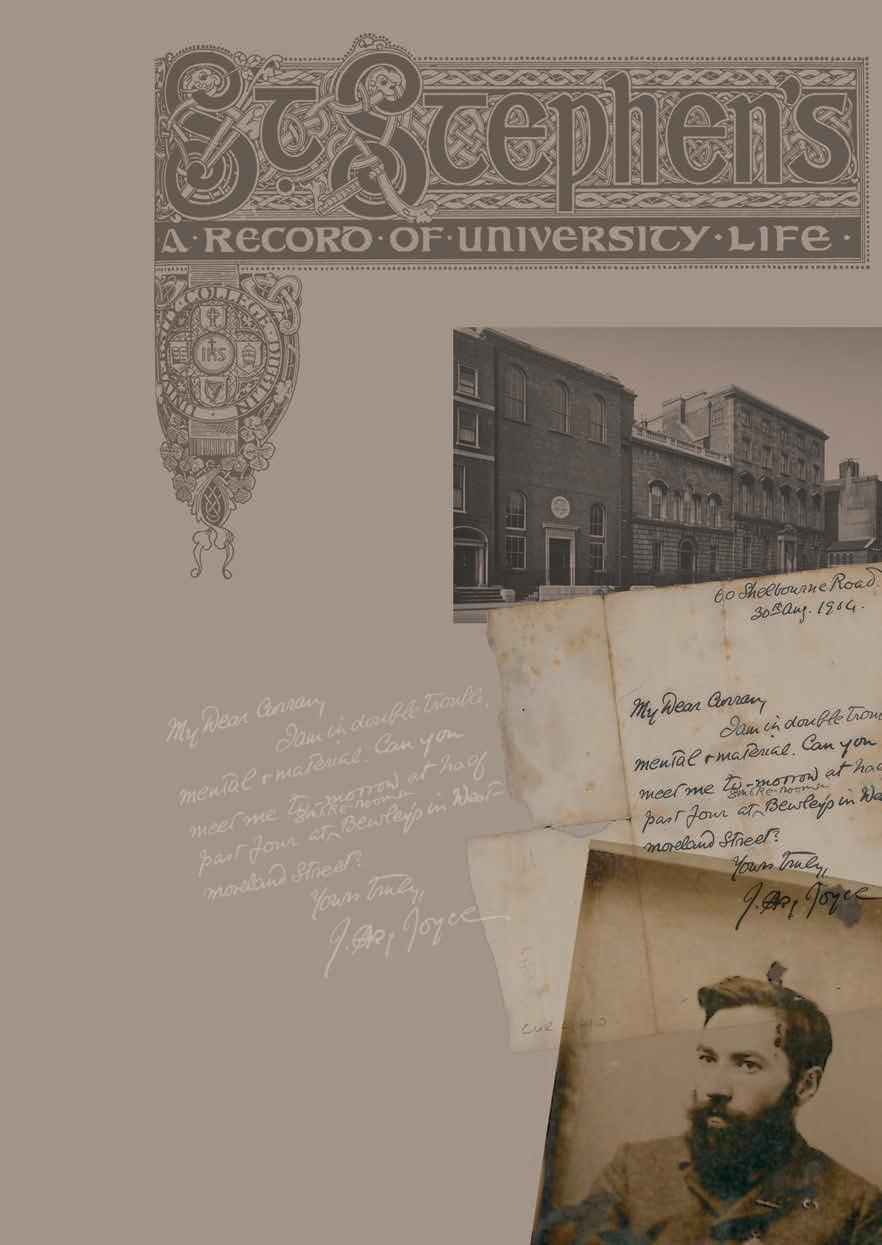

Curran dated 30 August 1904 (CUR L 410). Constantine Curran/Helen Laird Collection, UCD Special Collections .

UCD Special Collections (48.O.6); photograph of Francis Skeffington previously owned by Tom Kettle (1.I.1a-b); letter from James Joyce to Constantine

Church) taken from an untitled photograph album published in the memory of Rev. T. Corcoran S.J., the first professor of education at UCD (1909–42).

Main image: Header of University College’s literary magazine St. Stephen’s (33.O.3); Insets: Photograph of St. Stephen’s Green (nos. 84-86 and University

6

“An Intelligent Centre”: Curran, Joyce and their University College Years, 1899-1904

Constantine Curran first met James Joyce in 1899 during a first year English Literature lecture at 87 St. Stephen’s Green. Joyce’s semi-autobiographical avatar in fiction, Stephen Dedalus, would later claim the Green as his own, but as Curran noted, A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man was not an “authentic background of college life.” Joyce’s Dublin was the same place as the city of the Literary Revivalists and the political figures who sowed the seeds of a revolution. These groups could both lay claim to the multifaceted city with an intellectual, political, and creative vibrancy that had University College at its heart.

In November 1901, Joyce and his college contemporary, Francis Skeffington self-published their essays, “The Day of the Rabblement” and “A Forgotten Aspect of the University Question” after they were rejected by the university’s literary magazine St. Stephen’s. Joyce’s essay was refused because of its reference to Gabriele D’Annunzio’s Il Fuoco. The collection includes Joyce’s signed copies of D’Annunzio’s La Gloria and Sogno d’un Tramonto d’Autumno St. Stephen’s included Joyce’s next submission “James Clarence Mangan” and in 1927 Curran sent a copy to Sylvia Beach, who published Ulysses. Beach’s correspondence with Curran also includes a typescript of Joyce’s Molly Bloom inspired version of the popular Irish song “Molly Brannigan.” In 1904, as editor of St. Stephen’s, Curran would later reject Joyce’s broadside “The Holy Office.”

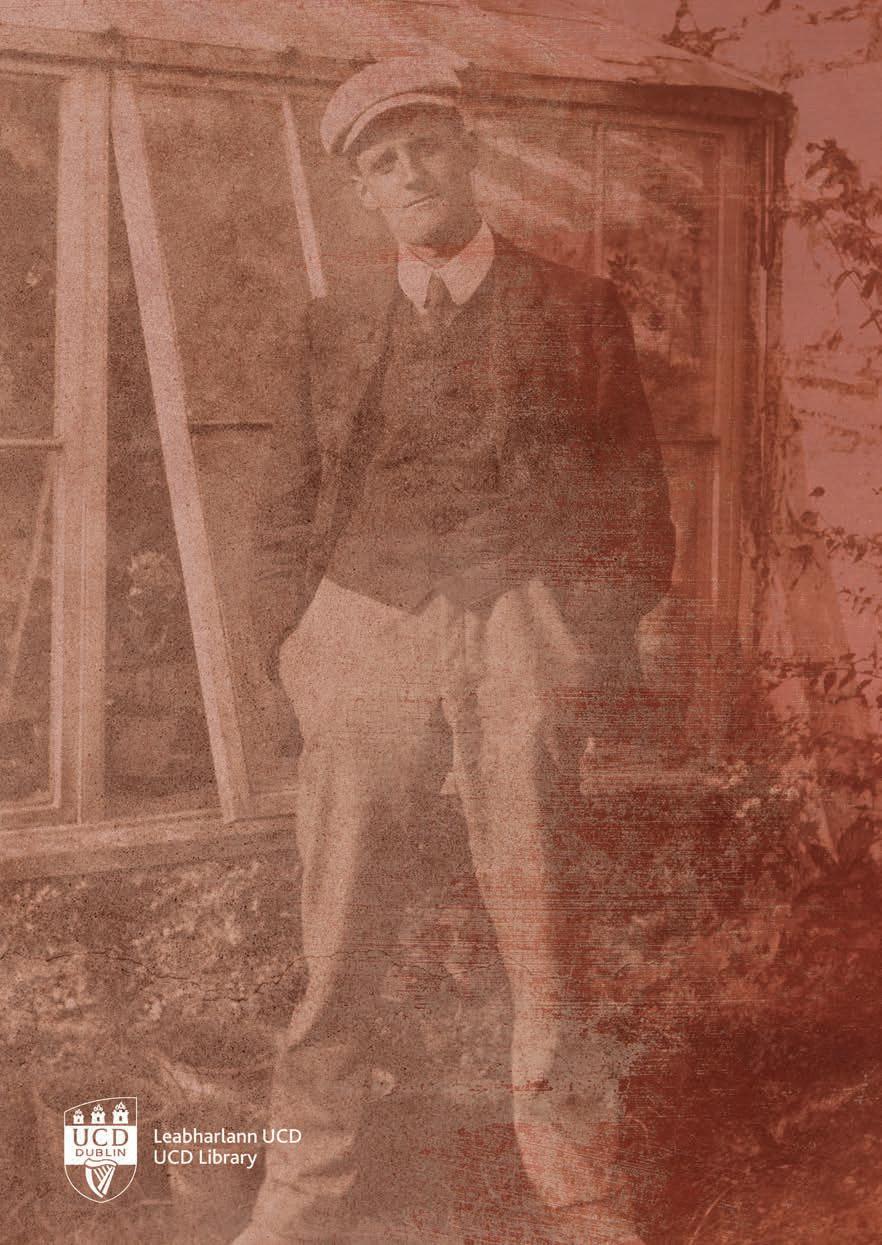

Curran is responsible for the two most famous images of Joyce from this period. He set up the graduation picture of the BA class of 1902 and photographed Joyce by the glasshouse in his back garden at 6 Cumberland Place on the North Circular Road. One of Joyce’s most often quoted and frequently discussed letters, that deems Dubliners a “series of epicleti” was sent to Curran. The Curran-Laird collection highlights Joyce and Curran’s connection to their alma mater and the global interest their contemporaries directed towards it.

7

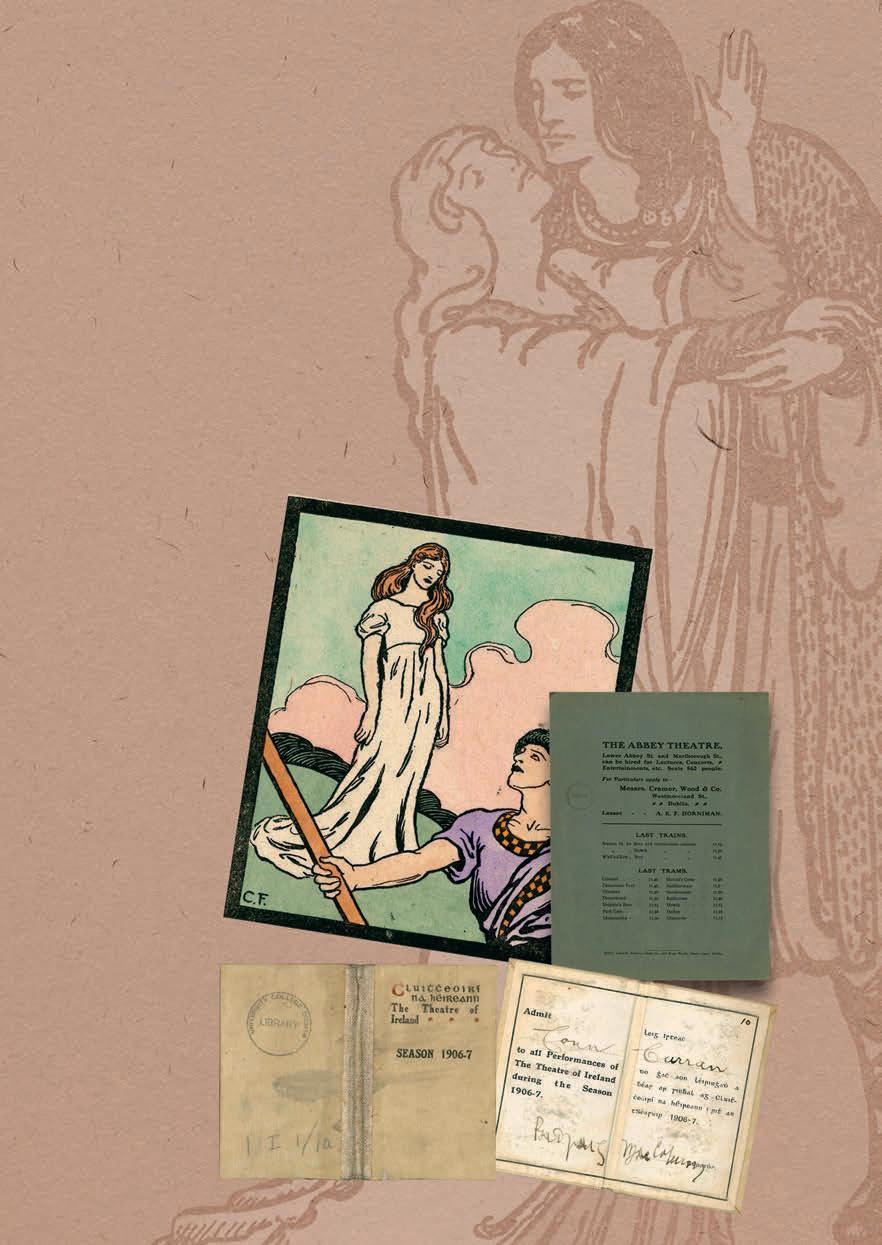

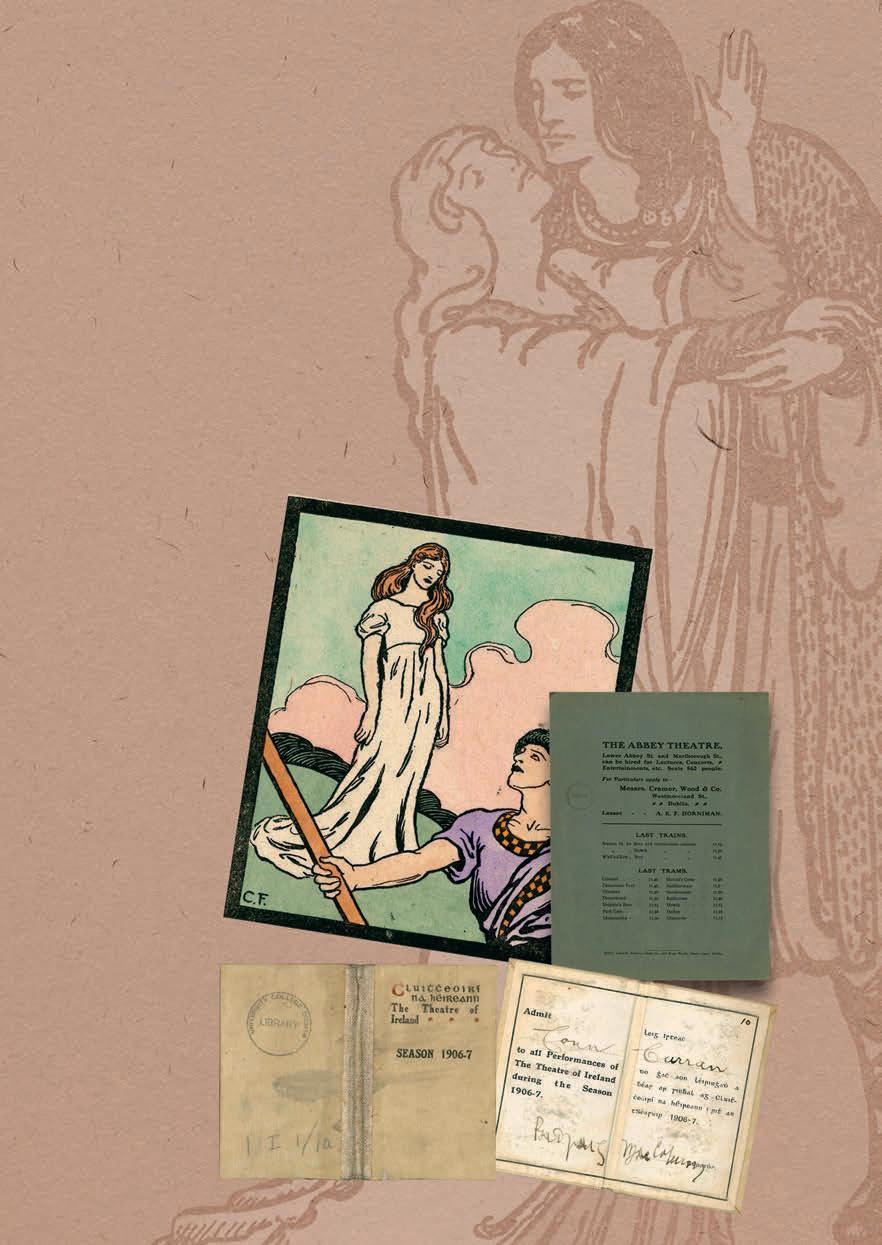

depicting a scene from Æ’s Deirdre from The Green Sheaf Supplement No. 7 (1903) (1.X.32).

Constantine Curran/Helen Laird Collection, UCD Special Collections.

cover of Abbey Theatre Programme for the opening night of J.M. Synge’s The Playboy of the Western World on 26 January 1907 (1.I.1/25). Cecil French illustration

Helen Laird Collection, UCD Special Collections . Insets: Constantine Curran’s 1906-1907 Theatre of Ireland Season Ticket signed by Padraic Colum (1.I.1/1a); back

Main image: Pamela Coleman-Smith illustration depicting a scene from Æ’s Deirdre from The Green Sheaf Supplement No. 7 (1903) (1.X.32)

Constantine Curran/

8

Helen Laird and the Irish Revival

Helen Laird was a founder member of W.G. Fay’s Irish National Dramatic Company. She made the sets and the costumes for the first performance of Æ’s Deirdre and W.B. Yeats’s Cathleen Ni Houlihan in St Teresa’s Hall, Clarendon Street on 2 April 1902. The company, including Yeats and Æ, wrote to her that “both plays went splendidly.” The Irish National Theatre Society and later the Abbey Theatre grew out of this venture. Under the stage name Honor Lavelle, Laird performed in some of the Revival’s most famous plays, including J.M. Synge’s Riders to the Sea

The playwright William Bernard Tarpey relayed a friend’s praise for her “quite flawless” performance as Maurya. Synge showed Joyce the play manuscript in Paris in 1903 and Nora Barnacle played Cathleen on 17 June 1918 with the English Players at the Pfauen Theater in Zurich.

Despite her early involvement in the Abbey, Laird with her friend Padraic Colum, Thomas MacDonagh, and others founded the breakaway Theatre of Ireland (1906–12). Joyce was also critical of the direction of the Abbey and prophesied he would “not see the curtain rise” on a reinvigorated theatre on account of having “already taken the last tram home.”

9

Collection, UCD Special Collections .

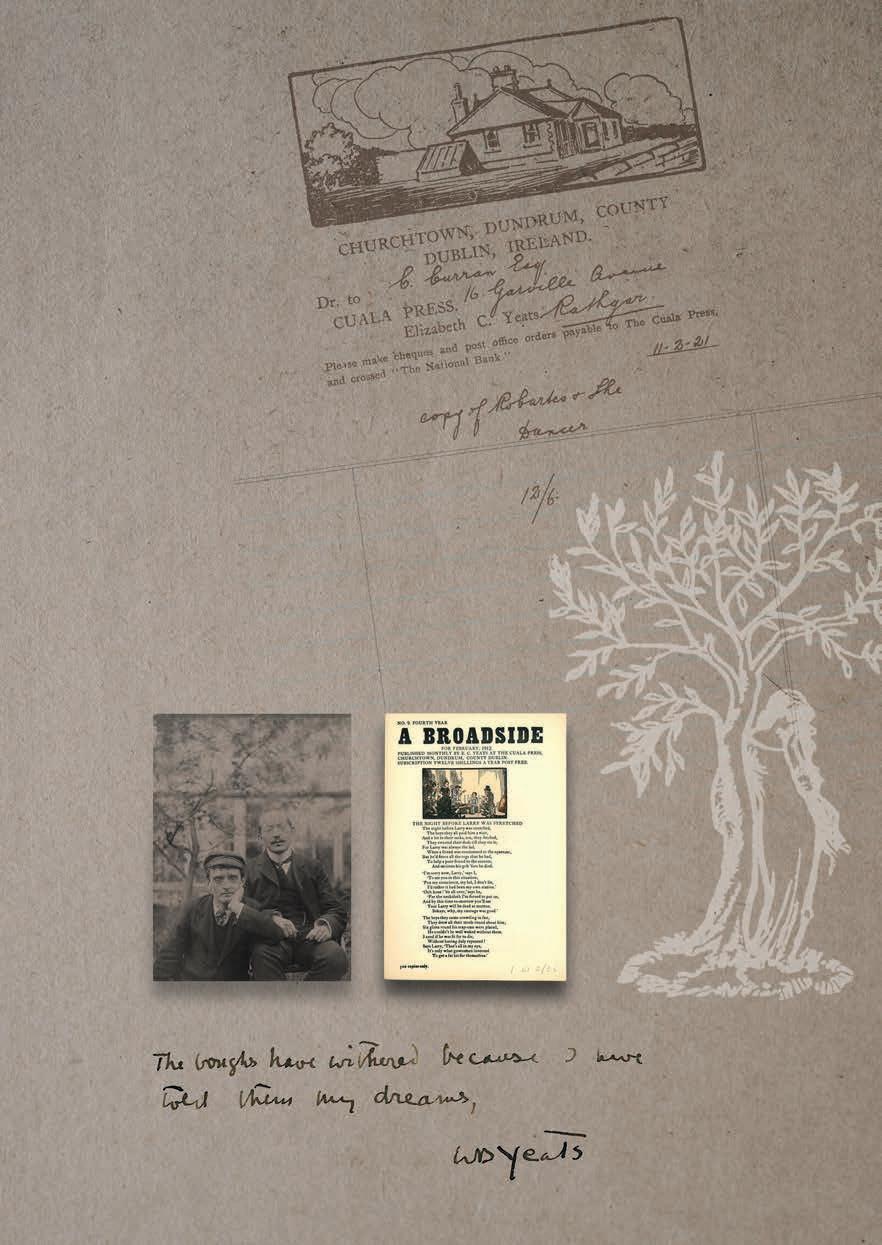

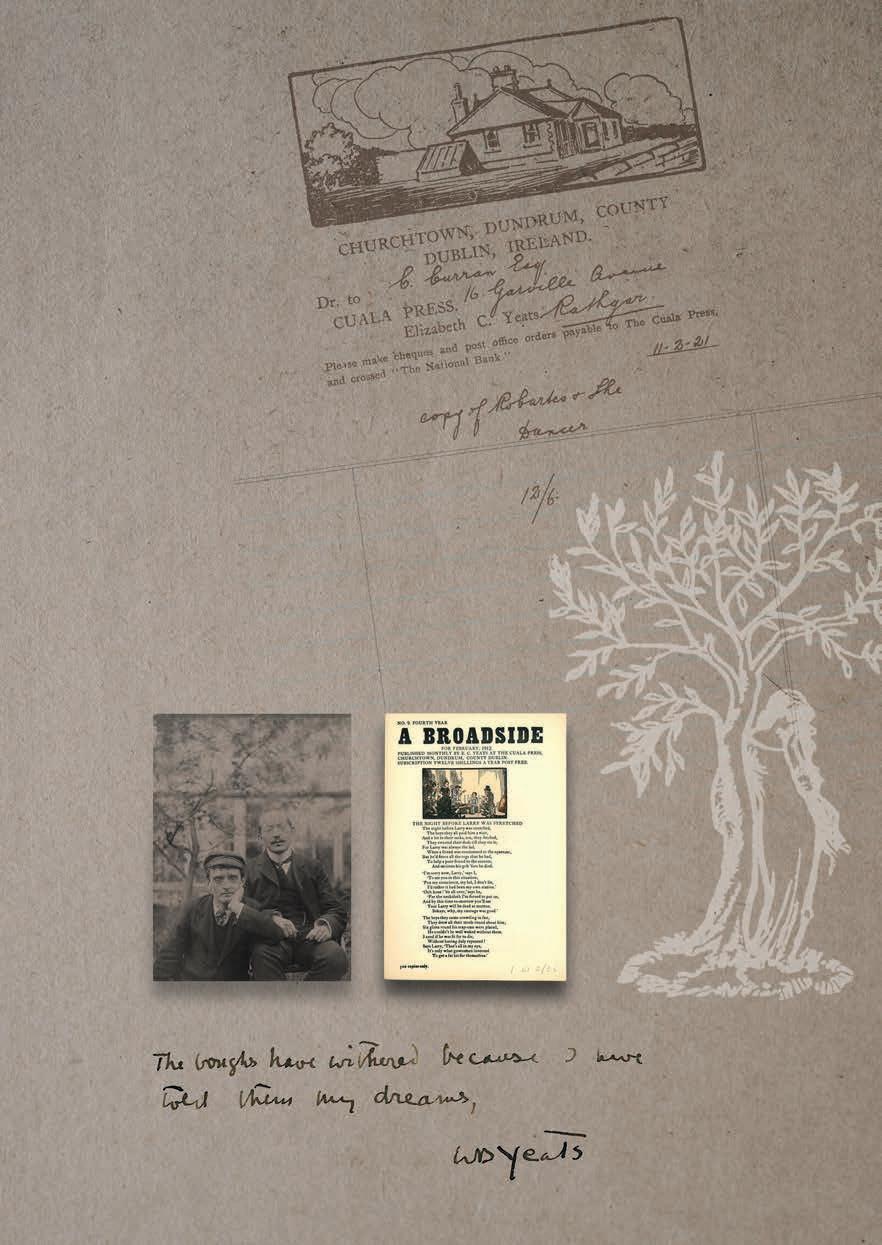

“The Night Before Larry was Stretched” (1.w.2/i); photograph of Constantine Curran and Padraic Colum (CUR P 34). Constantine Curran/Helen Laird

Tree” by Elinor Monsell used as a pressmark for the Dun Emer Press, 1907; Cuala Press A Broadside from February 1912, featuring the popular song

from W.B. Yeats on Dun Emer Press’s first publication In the Seven Woods: Being Poems Chiefly of the Irish Heroic Age (1.Y.24); “The Lady Emer Standing by a

Main image: Cuala Press receipt for Constantine Curran’s first edition of W.B. Yeats’s Michael Robartes and the Dancer (1.Y.23). Insets (clockwise): Inscription

10

Helen Laird, Constantine Curran and the Yeats Family

Constantine Curran and Helen Laird’s long friendship with the Yeats family was initiated through Helen and W.B. Yeats’s involvement in the Irish National Theatre Society. Although Maude Gonne was the first person to play Cathleen ni Houlihan, Maire T. Quinn assumed the role in the Irish National Theatre Society’s production in Queensgate Hall, South Kensington, 2 May 1903. Laird played Bridget and Yeats gifted her an inscribed first edition of the play.

The Currans’ connection to Elizabeth and Lily Yeats – who are derisively referred to as “the weird sisters” by Buck Mulligan in Ulysses – is illustrated by the Currans’ complete set of the Cuala Press Broadsides. The intimacy of their relationship with Jack B. Yeats and his wife Mary “Cottie” Cottenham Yeats, is demonstrated by Jack’s gift of Cottie’s sketchbook after her death in 1947. Curran wrote frequently on Jack B. Yeats in Studies and praised his work in the Irish Independent’s 1955 golden jubilee edition.

11

; papers of Hugh Kennedy (1879–1936), UCD Archives , IE UCDA P4/283 (3).

postcard of Arthur Griffith’s funeral on 16 August 1922 printed by Wisdom Hely’s (1.1.H.1/30). Constantine Curran/Helen Laird Collection, UCD Special

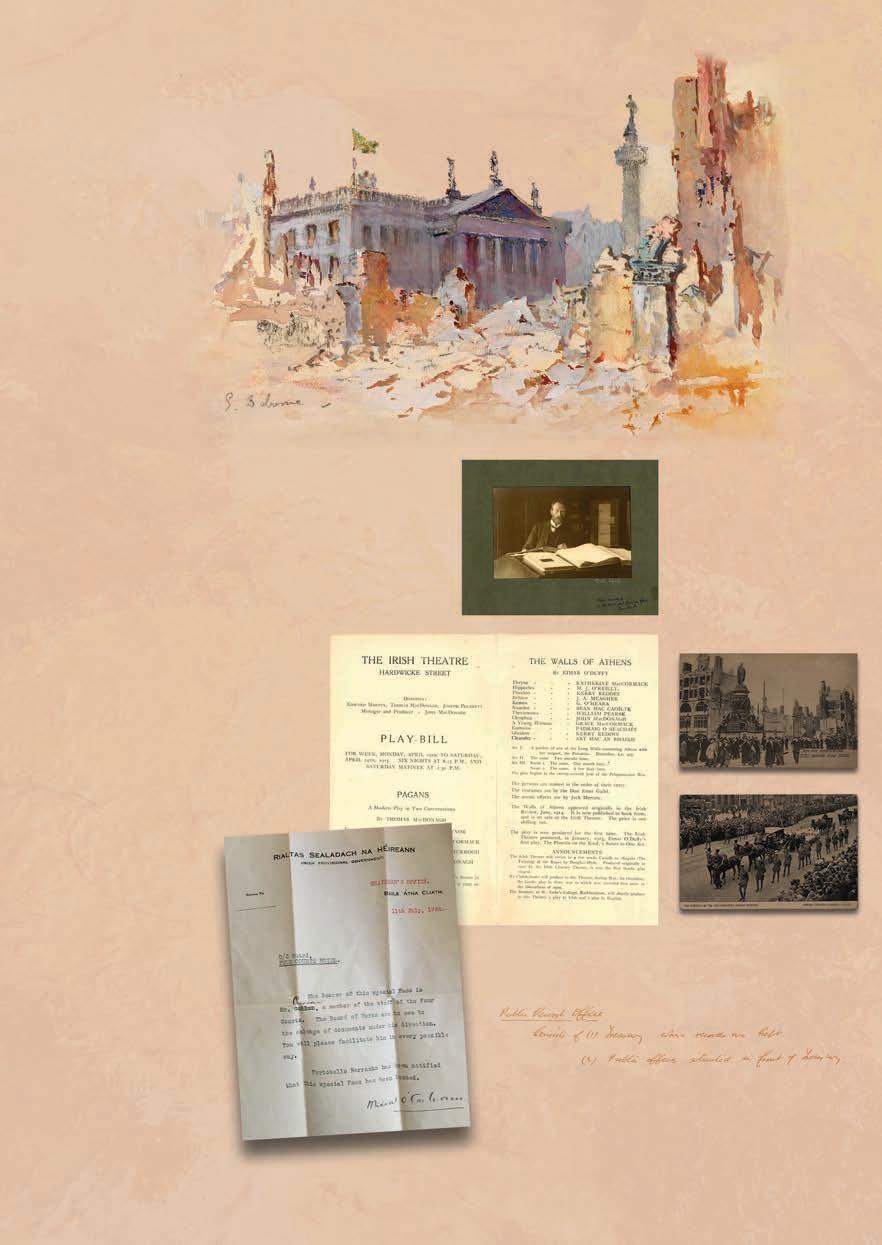

Easter Rising Commemorative Postcard depicting the damage done to Sackville (O’Connell) Street printed by Valentine, Dublin (1.H.1/13); Commemorative

Collections . CUR P 49; Michael Collins’ authorisation to salvage Public Record Office documents, Four Courts, letter, 11 July 1922. Curran-Laird Collection ; 1916

Special Collections . 1.I.1/11; photograph of Eoin MacNeill in the Four Courts taken by Curran in 1909. Constantine Curran/Helen Laird Collection, UCD Special

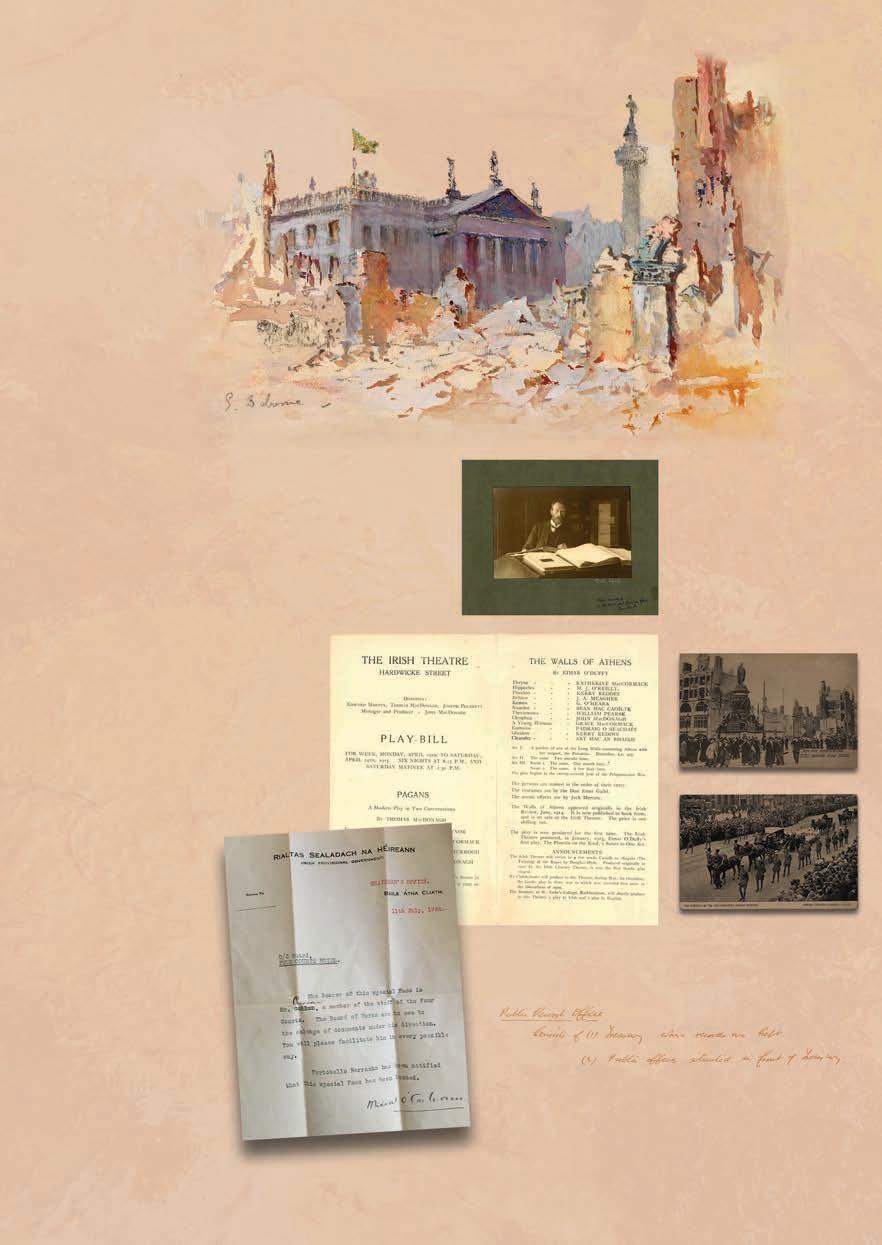

in Harwicke Street (April 1915) for Pagans by Thomas MacDonagh; The Walls of Athens by Eimar O’Duffy. Constantine Curran/Helen Laird Collection, UCD

Main image: Edmund Delrenne’s Sackville Street in Ruins (1916). National Gallery of Ireland’s Creative Commons Collection . Insets: Playbill of the Irish Theatre

Collections

12

The Currans and the Irish Revolution, 1916-1922

The Curran-Laird collection charts Ireland’s trajectory from political and cultural nationalism, to insurrection, civil war and the foundation of the state and reflects their personal acquaintance with the revolutionary generation. Laird’s membership of Inghinidhe na hÉireann accounts for the signed pamphlet of Constance Markievicz’s “Women, Ideals and the Nation.” Her involvement in political life is also reflected in her roles in the Ladies’ School Dinners Committee in 1911 and the Irish Women’s Franchise League.

The collection also includes a 1915 Hardwicke Street playbill featuring the names of prominent figures in both the Easter Rising and the establishment of the Irish Free State such as Thomas MacDonagh, Joseph Plunkett, Padraig Pearse and Eimar O’Duffy, many of whom were associated with The Irish Review (1911-1914). O’Duffy was one of the messengers who prompted Eoin MacNeill to cancel the Easter Rising. He would later write a positive review of Ulysses in a re-established Irish Review. Curran worked as a clerk in the courts from 1903 and was appointed High Court Registrar in 1921, where he worked alongside MacNeill.

From 1916 to 1922 Curran was the Irish Correspondent for the British Newspaper The Nation. In the aftermath of the Easter Rising Curran took the editor of The Nation H.W. Massingham around Dublin. Curran wrote for the paper under the pseudonym Michael Gahan – a nod to his mother’s maiden name McGahan – and was considered “a remarkable correspondent in Dublin” by Massingham’s biographer, Alfred Havighurst. Curran’s connection with The Nation meant it was one of the first publications to review A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (1916). After the anti-treaty explosion in the Public Records Office in July 1922, Michael Collins sent Curran to appraise the damage. By the end of August, Michael Collins and Curran’s close friend Arthur Griffith were dead.

13

Main image: St. George’s Church photographed from Eccles Street by Constantine Curran in the 1940s. CUR P15 Constantine Curran/Helen Laird Collection, UCD Special Collections Insets: Constantine Curran’s March 1918 The Little Review (1.T.17); envelope addressed to Mr and Mrs Curran by Joyce on 31 July 1935 (CUR L 187). Constantine Curran/Helen Laird Collection, UCD Special Collections

14

Curran and Joyce, the Later Years, 1917-1941

Joyce regularly sent Curran copies of The Little Review in which Ulysses was serialised. On 11 February 1922 Joyce inscribed no. 309 of the 1,000 copy first edition Shakespeare and Company Ulysses to Curran, which Sylvia Beach sent to Dublin for Joyce. Beach later sent first editions to Lennox Robinson (751) and W.B. Yeats (939); the former is part of the Curran/Laird collection. Curran was instrumental in Harriet Shaw Weaver’s decision to donate the manuscript of A Portrait to the National Library of Ireland. On St Patrick’s Day 1952, she donated copy number 1 of Ulysses to the National Library.

While in Paris, Joyce gifted Curran the October 1925 Le Navire d’Argent, which included the Anna Livia Plurabelle episode of Finnegans Wake. Curran followed Joyce’s instructions to declaim it “half aloud, without a break and rather rapidly” when reading it for Helen. As Joyce was working on the novel, he frequently asked Curran for Irish song books and Curran assisted him with his father’s will and Lucia Joyce’s health.

The personal and professional help Curran gave Joyce is in keeping with Stanislaus’s assessment that Curran was “one of the very few people [Joyce] could rely on in Dublin” and reflects their enduring friendship.

15

Main image: Constantine Curran’s bookplate designed by Jack B. Yeats in the early 1940s. Constantine Curran/Helen Laird Collection,

UCD Special Collections .

Main image: Constantine Curran’s bookplate designed by Jack B. Yeats in the early 1940s. Constantine Curran/Helen Laird Collection,

UCD Special Collections .

16

Curran’s Writing

Curran’s publishing career only took off after Joyce’s death and showcases his diverse range of interests. His first book, The Rotunda Hospital: Its Architects and Craftsmen was published in his native Dublin by The Three Candles Press in 1945. This was followed by Dublin Decorative Plasterwork of the 17th and 18th Centuries in 1967. Although Curran’s best-known work remains James Joyce Remembered, his final book Under the Receding Wave provides an equally fascinating and elucidating panorama of late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Dublin, particularly the multifarious facets of its cultural and political life. “Revolutionary Dublin’s Literary Networks: C.P. Curran, Helen Laird, and James Joyce’s Ulysses” publicly showcases a unique Joycean collection for the first time and comes a couple of months after the publication of the new issue of Curran’s memoir on Joyce by UCD Press. The publication of Ulysses and the establishment of the Irish Free State bookended 1922. Upon the centenary of these events, the idiosyncrasies of the Curran-Laird collection can provide us with insight into the intellectual milieus and networks of friendship which inflect both the novel and newly established State. Curran and Laird’s archive reflects their status as cultural custodians and political activists in and beyond the Revolutionary period. To borrow a phrase from Ulysses, the writing of both cultural and political history is a kind of “retrospective arrangement” and the Curran-Laird collection illuminates this process in a distinctly Dublin context.

Given the international interest in James Joyce, the Yeats family, the Irish theatre and the political upheaval of the early twentieth century, it is unsurprising that there is also a global dimension to the Curran-Laird collection and their influence on international efforts to write and understand Irish cultural and political history. Laird’s correspondence sheds light on the inner workings of the Irish National Theatre Society as it was in its infancy, as well as her interesting reflections on this period in later years. Curran’s correspondence with Joyce biographers and critics, such as Richard Ellmann, Stuart Gilbert, Herbert Gorman, Richard M. Kain, John J. Slocum, and William York Tindall reflects his influence on the construction of the orthodox and abiding critical and popular image of Joyce. He would retain contact with many in the Joyce circle, including T.S. Eliot. Notably, the collection includes a telegram from Eliot (on Faber and Faber headed paper), which recalls a walk in Glendalough with Curran and the family of future UCD president Jeremiah Hogan. This walk would inspire a line in “Little Gidding”, the fourth and final poem of T. S. Eliot’s Four Quartets. In his preface to James Joyce

Remembered, Curran is clear that he is writing in “vindication of my town and generation” and the breadth and depth of the Curran-Laird collection reveal the necessity of Curran’s enterprise.

17

Main image: University College, Dublin: main College buildings, Earlsfort Terrace.

Main image: University College, Dublin: main College buildings, Earlsfort Terrace.

18

Bibliography

Curran, Constantine. James Joyce Remembered: Edition 2022, edited by Helen Solterer with Alice Ryan, with essays by Hugh Campbell, Diarmaid Ferriter, Anne Fogarty, Margaret Kelleher, Helen Solterer, Evelyn Flanagan and Eugene Roche. UCD Press, Dublin, 2022.

Havighurst, Alfred. Radical Journalist: H. W. Massingham (1860–1924). Cambridge University Press, New York, 1974.

Joyce, James. Letters of James Joyce. Edited by Richard Ellmann, Vol. II, Viking, New York, 1966.

--- . Occasional, Critical and Political Writing, edited by Kevin Barry, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2000.

--- . Ulysses. Edited by Hans Walter Gabler, Bodley Head, London, 1984.

Joyce, Stanislaus. Letter to Constantine Curran. 1 January 1954. Constantine Curran/ Helen Laird Collection, UCD Special Collections. CUR L 172a.

--- . Letter to Constantine Curran. 6 April 1955. Constantine Curran/Helen Laird Collection, UCD Special Collections. CUR L 175.

Moore, George. Vale. Heinemann, London, 1914.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the staff in UCD Special Collections, Kathryn Milligan, Daniel Conneally, and particularly Evelyn Flanagan and Eugene Roche for all their support during this project. I must also express gratitude for Anne Fogarty’s advice, insight and support at both the formative and final stages of the process. I am also grateful to Catherine Bodey for her design work on the exhibition and this booklet.

19

SPECIAL COLLECTIONS READING ROOM James Joyce Library University College Dublin Belfield, Dublin 4 Phone: +353 (0)1 716 7583 Email: library@ucd.ie Published to accompany the exhibition of items from the Constantine Curran/ Helen Laird Collection as part of UCD’s Decade of Centenaries. ISBN: 978-1-910963-61-6 ©UCD 2022

Constantine Curran/Helen Laird Collection, UCD Special Collection (CUR L 30).

Constantine Curran/Helen Laird Collection, UCD Special Collection (CUR L 30).

Main image: Constantine Curran’s bookplate designed by Jack B. Yeats in the early 1940s. Constantine Curran/Helen Laird Collection,

UCD Special Collections .

Main image: Constantine Curran’s bookplate designed by Jack B. Yeats in the early 1940s. Constantine Curran/Helen Laird Collection,

UCD Special Collections .

Main image: University College, Dublin: main College buildings, Earlsfort Terrace.

Main image: University College, Dublin: main College buildings, Earlsfort Terrace.