5 minute read

NOBLE PRIZE WINNERS BRING LIGHT TO HEPATITIS C

LET THE SILENT EPIDEMIC BE HEARD

NOBEL PRIZE WINNERS BRING LIGHT TO HEPATITIS C

Advertisement

By Ashley Chen Maha Khan

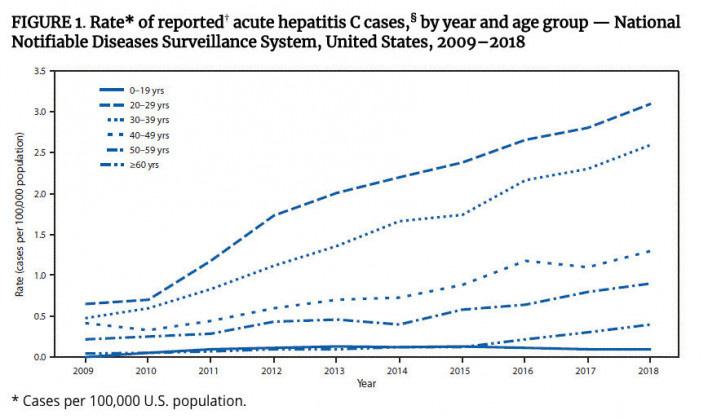

A silent epidemic is sweeping the nation. Discovered in 1989, hepatitis C struggles to gain the recognition it needs. For victims like Rick Starr, contraction of the disease occurred well before its discovery. Starr is one of the 75% of individuals infected who developed chronic hepatitis C because his body could not clear the virus on its own. It was only through a mandatory blood test for his job that he was diagnosed with hepatitis C. Due to social stigma surrounding the disease, he waited 7 years before seeking treatment. During those years, he experienced no obvious side effects: clinical diagnosis of hepatitis C is frequently missed because it is often asymptomatic. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that 3.5 million people are living with hepatitis C, and at least 50% of people living with hepatitis C do not know they are infected. This lack of awareness presents a serious issue as the rate of new hepatitis C cases is 4 times as high as they were 10 years ago among people ages 30-39 (Figure 1). By awarding the 2020 Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine to virologists Harvey J. Alter, Michael Houghton, and Charles M. Rice for their discovery of hepatitis C, there is hope for a revival of research in and greater understanding of the virus.

Hepatitis is an inflammation of the liver. It is usually spread through contaminated blood. The virus can cause abdominal pain, fatigue, jaundice, liver failure, and in some cases death.

In 1967, the hepatitis B virus (HBV) was identified by Baruch Blumberg. At this time, Alter was working at a blood bank at the United States National Institutes of Health. Blood could be screened to ensure that people would not get HBV from a transfusion; however, patients were still developing hepatitis. The blood-borne agent causing the disease was not being screened out by the tests developed for hepatitis A and B. This prompted Alter to study the transmission of hepatitis caused by blood transfusions in the 1970s. Alter and his colleagues showed that a third, bloodborne viral pathogen could transmit the disease to chimpanzees.

As Alter found evidence for non-A, non-B hepatitis, Houghton was working at Chiron Corporation with his colleagues to identify the virus based on genetic material from infected chimpanzees. Spending the late 1980s isolating the genetic sequence of the virus, they collected DNA fragments from an infected chimpanzee and matched fragments of the unknown virus with those from patients with hepatitis until they were able to find a match. They discovered that it was a new kind of RNA virus of the Flaviviridae family, which includes viruses that cause dengue, Zika, West Nile, and yellow fever, and named it the hepatitis C virus (HCV) in a 1989 paper. Building on Alter and Houghton’s work, Rice led a team based at Washington University to study the hepatitis C genome and show that this new virus could, in fact, cause hepatitis. His team used genetic-engineering techniques to characterize a portion of the genome responsible for viral replication and showed that when the new RNA variant of HCV reached the liver unimpeded, it would cause hepatitis. Work by Alter, Houghton, and Rice fit together to make great strides in explaining most blood-borne hepatitis cases, which was not feasible with the prior identification of hepatitis A and B viruses. Alter’s speculation of a new hepatitis virus led to Houghton’s discovery of the virus and Rice’s confirmation of its role in causing liver disease.

The WHO estimates that 71 million people worldwide are chronically infected with HCV with approximately 400,000 annual deaths, mostly from cirrhosis and liver cancer. More individuals die from hepatitis C than all of the 60 reported infectious diseases combined. Treatment is critical as nearly 320,000 deaths can be prevented by testing and referring infected persons to care and treatment.

The standard therapy of pegylated interferon-alpha and ribavirin has its limitations. Thus, creating an HCV vaccine is ideal. Efforts to develop a vaccine began more than 30 years ago. Since then, researchers have studied over 20 potential vaccines in animals. However, there are limited animal models of hepatitis C infection as well as ethical and cost concerns. Hepatitis A and B currently have vaccines, but HCV presents a challenge as it is highly variable among strains. HCV occurs in at least six genetically distinct forms. Different HCV genotypes are distributed unevenly in different parts of the world (Figure 2). A global vaccine would have to protect against all of these variants of the virus.

Because of the virologists’ discovery of hepatitis C, the disease can now be cured for the first time, raising hopes of eradicating it. Nonetheless, further research is needed to tackle this prevalent disease and improve global health. A vaccine is needed to control the virus. One of the Nobel Prize laureates, Houghton, is now working on a vaccine against HCV. Unfortunately, research initiatives in the virus have slowed due to decreased funding and willingness to commit to such a long-term project. In the face of COVID-19, however, virology and viruses are finding a place in the public eye. The prize will hopefully contribute to the attention and spur investment in a possible vaccine. By reviving enthusiasm in treatment and shedding light on the silent epidemic, a better understanding of viruses can be uncovered, saving millions of lives.

"A Hepatitis C Success Story". 2020. Gastrointestinal Society. https://badgut.org/ information-centre/a-z-digestive-topics/a-hepatitis-c-success-story/. Caffrey, Mary. 2020. "Discovery Of Hepatitis C Virus Brings Nobel Prize".

AJMC. https://www.ajmc.com/view/discovery-of-hepatitis-c-virus-bringsnobel-prize. Callaway, Ewen, and Heidi Ledford. 2020. "Virologists Who Discovered

Hepatitis C Win Medicine Nobel". Nature. https://www.nature. com/articles/d41586-020-02763-x#:~:text=Blood%2Dborne%20 pathogen&text=Houghton%2C%20then%20working%20at%20

Chiron,named%20it%20hepatitis%20C%20virus. Chambers, Thomas J., Chang S. Hahn, Ricardo Galler, and Charles M. Rice. 1990. "Flavivirus Genome Organization, Expression, And Replication".

Annual Review Of Microbiology 44 (1): 649-688. doi:10.1146/annurev. mi.44.100190.003245. Guidelines For The Care And Treatment Of Persons Diagnosed With Chronic

Hepatitis C Virus Infection. 2018. Geneva: World Health Organization. "Hepatitis". 2016. Medlineplus. https://medlineplus.gov/hepatitis.html. Hepatitis C, A Silent Epidemic. 2020. Ebook. Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/newsroom/docs/factsheets/

Hepatitis-C-A-Silent-Epidemic-Infographic.pdf. Highleyman, Liz. 2020. "New Hepatitis C Cases Tripled Over The Past Decade".

Hep. https://www.hepmag.com/article/new-hepatitis-c-cases-tripled-pastdecade. Manns, M P, H Wedemeyer, and M Cornberg. 2006. "Treating Viral Hepatitis

C: Efficacy, Side Effects, And Complications". Gut 55 (9): 1350-1359. doi:10.1136/gut.2005.076646. Rizza, Stacey. 2020. "Why Isn't There A Hepatitis C Vaccine?". Mayo Clinic. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/hepatitis-c/expertanswers/hepatitis-c-vaccine/faq-20110002.