Photos by Melissa Hernandez De La Cruz

Gators for Change Stor y by A lex is Vega

The University of Florida is home to over 57,000 students as of fall 2020, according to the Gainesville Sun. That’s 57,000 people with their own unique thoughts and beliefs about the events happening around them. On occasion, these beliefs are expressed through protest. But students using their voices to champion change is not a new occurrence in line with the times. UF has a long history of students acting upon their First Amendment right to protest.

The Vietnam War According to an online selection from the Smathers Library Exhibit Gallery, on Oct. 15, 1969, the University of Florida Student Mobilization Committee (SMC) organized a nonviolent protest against the Vietnam War called “Gentle Wednesday.” There were around 1,800 students and faculty in attendance, assembled at the Plaza of the Americas while the SMC distributed armbands. The number ‘644,000’ was written on them as a tribute to the number of American casualties in the war. By 1972, the rage over The Vietnam War had bubbled over and students felt compelled to make their stance heard. On May 2, 1972, Gainesville residents organized its largest anti-war rally yet, according to the Gainesville Sun. It was nowhere near peaceful. About 2,000 protesters fought against Gainesville police and other law enforcement officers on West University Avenue. The brawl escalated when law enforcement used weapons such as tear gas and water cannons against protesters.

Kent State After the tragic 1970 mass shooting that resulted in the death of four Kent State University students during an oncampus, anti-war protest, the University of Florida held its own rally in response. The protesters demanded that classes be suspended, but UF President Stephen O’Connell did not oblige. Instead, he proclaimed a day of mourning for May 6, 1970. About 3,000 students rebelled against this decision and, as a result, campus was closed from May 6 to May 8. So how does UF’s legacy of combating injustices uphold today?

Controversial Guest Speakers The University of Florida has hosted several guest speakers; however, as a public institution, it cannot choose which speakers are allowed to visit. This would be an infringement on the First Amendment. Needless to say, there have been instances in which a guest speaker has evoked strong feelings of anger and fear in the university’s student body due to said speaker’s platform. The president of the National Policy Institute, Richard Spencer, requested to make an appearance at the university on Sept. 12, 2017. A prominent white nationalist, Spencer’s rhetoric was bound to incite violence on campus, especially in the wake of Charlottesville fights between white nationalists and counterprotesters, according to an announcement from UF News. This risk of physical violence is what allowed UF President Kent Fuchs to decline Spencer’s request. However, after the threat of a lawsuit from a local First Amendment lawyer, Gary Edinger, the university acquiesced to Spencer’s demands, according to The New York Times. It decided on a later date to have time to plan for the event’s security. 74 The Origins Is sue

“When the university creates an auditorium … which is really designed for speech-based events… one of the First Amendment rules is that the government, in this case, the University of Florida, cannot discriminate against potential speakers in that venue based upon their viewpoint,” said Clay Calvert, a law professor, the Brechner Eminent Scholar in Mass Communication and Director of the Marion B. Brechner First Amendment Project at UF. “So, a major First Amendment principle is what we call ‘viewpoint neutrality,’ that the government cannot discriminate against people based upon the offensive nature of their viewpoint.” When Richard Spencer finally spoke at the university on Oct. 19, 2017, he was greeted by 2,500 impassioned hecklers, whom he called “shrieking and grunting morons,” according to The Washington Post. About $600,000 had been spent by UF for the event’s security. “In the ‘marketplace of ideas’ in the United States, we tolerate a lot of hateful speech, and the remedy to it is counterspeech, which by that I mean that people who oppose the viewpoints that they find offensive or hateful should engage in their own expression against it and have a counterprotest,” said Calvert. “And that’s what we saw with Richard Spencer coming to campus, so that’s a great example of counterspeech.” Considering the level of law enforcement personnel, the protest was nonviolent. Demonstrators shouted out different chants to drown out Spencer’s speech. Some shouted, “Black Lives Matter!” Others opted for, “Not my town, not my state, we don’t want your Nazi hate!” The message was clear: Intolerance is not tolerated at UF.

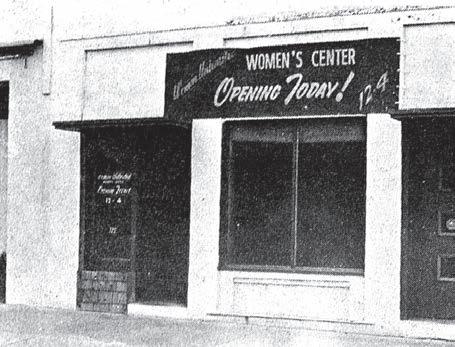

Campus Safety Even something as seemingly mundane as campus safety has led to fervent calls by the student body for better treatment. On Sept. 17, 2019, students organized a protest to advocate for the installment of “blue lights” on Fraternity Row. “Blue lights” are the blue emergency poles scattered across campus that give students access to police when they are in danger or need assistance. Notably, out of the 357 that existed at the time, none were installed on Fraternity Drive, according to The Independent Alligator. The fact that the blue lights were intended to be visible from each other further magnified the issue of their absence on Fraternity Row. “In spring [2019], the SG Senate failed to pass a resolution that would expand blue light coverage on fraternity row. A primary reason it didn’t pass was the failure to contact the Interfraternity Council presidents,” said the article. As a result, students took the matter into their own hands. About 200 students, along with the Gainesville chapter of National Women’s Liberation, marched down Fraternity Row holding signs and chanting in unison for the installment of blue lights. By Sept. 27, 10 days later, the university announced that it would be installing four new blue light emergency posts to the Fraternity Row area, according to UF News. Florida Gators have continually proven not to shy away from conflict when it comes to standing up to intolerance. The rich history of students finding their voices and using them to enact change for the greater good has brought about many questions as to how they can continue to uphold this legacy. Though there has been conflict with law enforcement, institution presidents and even the First Amendment itself, UF’s students have been shown not to give up so easily on what is worth fighting for. The Origins Is sue 75