LIVE LONG.® Ultrarunning Legends // Run Commute Gear // Lake Sonoma NOVEMBER 2021 $8 U.S./$10 CAN

DRYMAXSPORTS.COM

Athlete: Patrick Reagan

Photo: Luis Escobar

Features

24 RUN COMMUTE GEAR REVIEW

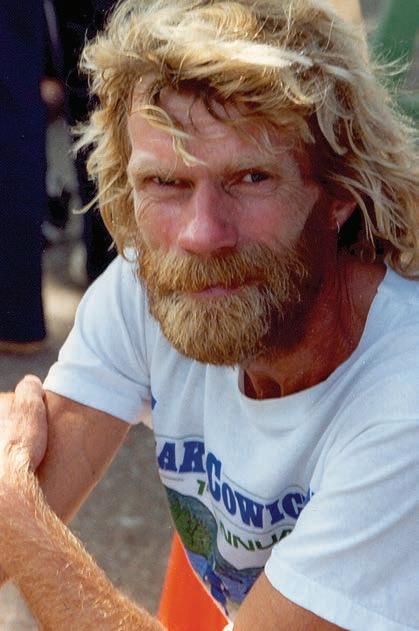

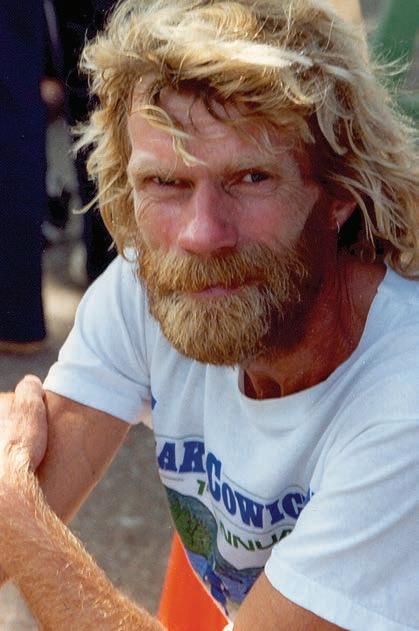

30 AL HOWIE: THE MAN WHO COULD RUN FOREVER

While most of us dream of running 100 or 200 miles, Al Howie dreamed much bigger. And then he went out and ran. Author Jared Beasley writes about his life on the run and more.

36 Voice of the Sport GRAND SLAM OF A YEAR

Ultraraces

42 LAKE SONOMA // CALIFORNIA

50 BARKLEY FALL CLASSIC

60 LEAKY HOURGLASS ULTRA // MISSOURI

Ultralife

64 Faces of Ultrarunning PUT YOUR MONEY WHERE YOUR MOUTH IS

66 One Step Beyond THE ORIGINAL ULTRAMARATHONER

67 Reese’s Pieces WHEN YOU CAN’T OUTRUN DEPRESSION

68 Destination Unknown TIME PASSAGES

69 Sarah’s Stories ANNA FROST: FROM PODIUMS TO PARENTING

70 Running Down Under WHAT MAKES A LEGEND?

71 I Am an Ultrarunner JAKOB HERMANN

UltraRunning (ISSN 0744-3609), Volume 41, Issue 5. ©2021 by UltraRunning, all rights reserved. UltraRunning is a trademark of UltraRunning Media Group, LLC. ©2020 UltraRunning Media Group, LLC. UltraRunning is published 9 times a year by UltraRunning, P.O. Box 6509, Bend, OR 97708. Periodicals postage paid at Portland, OR, and additional mailing offices. SUBSCRIPTION Rates for one year (9 issues): US $3999 per year automatic renewal/$4999 manual renewal; CAN/Mexico $7499/$8499 per year (US funds); outside North America $8999/$9999 (US funds). POSTMASTER Send address changes to UltraRunning, P.O. Box 6509, Bend, OR 97708. Disclaimer: Although ultrarunning is a wonderful activity that we fully encourage as part of a vigorous and healthy lifestyle, the activities described in UltraRunning magazine can entail significant health risks, including significant injury or death. Do not engage in ultrarunning unless you are knowledgeable about all the risks and assume full responsibility for them. Use of and reliance upon the information contained in this magazine and on its website and other digital platforms, is at your own risk. The information, recommendations and opinions of our writers and advertisers reflects their views, and is not necessarily the opinion or view of the magazine or its ownership. UltraRunning Media Group makes no warranties, express or implied, as to the accuracy or completeness of the information contained herein or in its other media, and further disclaims any responsibility for injuries or death incurred by any person engaging in ultrarunning or relying upon content contained herein. CONTENTS NOVEMBER 2021 Lake Sonoma runners fall in line on the trail above the lake. This year’s race was postponed in April and took place over Labor Day weekend. LUIS ESCOBAR 4 Moving Forward I LOVE YOU, MAN 6 News & Notes New 24-Hour Record, Weather Prompts Rescue, UTMB Champs, Case Wins Tor Des Glaciers, TDS Accident, Marathon Des Sables Death, New ITRA President, Letters to the Editor Ultracoach 9 From the Coach IMPROVE YOUR NEXT PERFORMANCE 10 Ultra Life Balance AN INTERVIEW WITH BRUCE FORDYCE 12 Koop’s Corner KARL MELTZER’S TRAINING 14 Movin’ On Up BECOMING LEGENDARY 15 Tricks of the Trade MONTRAIL: THE ORIGINAL TRAIL BRAND & TEAM Sean Meissner takes readers back to the start of the first ever ultrarunning team, and how it all began. Ultrageek 16 Ultrarunning Science GUIDELINES FOR READING & INTERPRETING

Wise THE

20 Ultra

THE

UNHEALTHY AIR

CLOSING

RACE

SPORTS SCIENCE RESEARCH 18 Pete’s Perspective WHERE IS YOUR MIND? 19 Running

NUMBER 100

Doc

SILENT PANDEMIC OF

23 View From the Open Road

A

//

// TENNESSEE 56 GEORGIA JEWEL

GEORGIA

ON THE COVER: Dena Carr makes her second ascent up Rat Jaw, a 0.9-mile climb with roughly 2,000 feet of gain, at the Barkley Fall Classic 50K. JENNY THORSEN

ILove you, Man

Relationships need to be nurtured. That’s never been more apparent. After being separated from so many over the past year, I decided to pack a lot of running into the fall months, and the one thing I’ve come to realize is how much I’ve missed spending time with my ultrarunning family.

In August, my sporadic summer training finally came to a close and race weekend approached like a secret handshake – I had it memorized but wasn’t sure if I’d practiced enough. And then, one day before the race, nerves kicked me in the gut, which can happen when you haven’t raced in over a year. My appetite had been sequestered to the acid gods and I was left with a guessing game. Maybe I should eat? I think I’m full? It was hard to tell.

I bid my family adieu and made the hour-long drive southwest of Bend, Oregon, to Willamette Pass Ski Area and let me tell you what, standing at the base of a ski hill can really mess with your head when you’re planning to run 62 miles in just a few short hours. My nerves were officially shot.

Prior to the 3 a.m. “early” start, I ran into some familiar faces who gave me words of encouragement prior to my 100k journey –it was all I needed to resolve the lingering doubt in my mind. We started off as a pack in the middle of the night, slowly making our way up and around the bare slopes. Once we reached the backside, I fell into a good pace and was making sure the runners behind me were able to get by when needed. In the dark, it can be tricky to pass on the trail and one runner pulled off to the side just as I did.

“Is your name Michael?” I asked.

“Yes,” he replied.

“I don’t know if you remember me, but I ran with you at McDonald Forest back in

2014,” I said. Michael happened to be one of the people I met at my very first ultra. I knew he’d be running the race, but I didn’t expect to literally bump into him.

We caught up on life while running with just a couple headlamps to help lead the way. Our first significant climb was supposed to be rewarded with views of Waldo Lake, but the peak was shrouded in clouds. On the way down, around mile 16, I mentioned my stomach wasn’t feeling great and that I was thinking of dropping. He said he wasn’t sure this was a great day for him to be running 100k, and we continued on with a silent understanding. Unfortunately, I didn’t feel any better and at mile 20, I called it a day. We said goodbye and I thought he was off, until he walked back and asked if I needed a ride back to the start. He had ended his race, too.

While it wasn’t the day I was hoping for, I felt so grateful I got to share some miles with Michael some seven years after we first met. I didn’t know how the day would go, but getting to run with someone I rarely see meant a lot and I wouldn’t have had it any other way. Ultrarunners are like long lost family when we see each other, whether it’s at a race, on a training run or just over good food and drinks.

There are so many ways to nurture your running relationships, but letting those who are important to you know how much they mean is a start. We’ve all been away from one another and it’s time to catch up from where we left off.

PO Box 6509 Bend, OR 97708 ultrarunning.com

SUBSCRIPTIONS

Laura Kantor help@ultrarunning.com

ADVERTISING SALES

Heather Pola heatherp@ultrarunning.com

PUBLISHER

Karl Hoagland karlh@ultrarunning.com

EDITOR

Amy Clark amyc@ultrarunning.com

CONTRIBUTING EDITOR

Donald Buraglio

DIRECTOR OF DIGITAL CONTENT AND OPERATIONS MANAGER

Cory Smith

ART DIRECTOR

Carly Koerner

COPY EDITOR

Hayley Pollack

SOCIAL MEDIA

Courtney Drewsen

EDITORS EMERITUS

Peter Gagarin, Fred Pilon, Stan Wagon, Don Allison, Tia Bodington, Karl Hoagland

COLUMNISTS

Lucy Bartholomew, Donald Buraglio, Meghan Canfield, Gary Cantrell, Gary Dudney, Clare Gallagher, Ellie Greenwood, Erika Hoagland, Dr. Tracy Høeg, Dean Karnazes, Jason Koop, Pete Kostelnick, Jeff Kozak, Matt Laye, Travis Macy, John Medinger, Sean Meissner, Cory Reese, Amy Rusiecki, Ian Sharman, Sarah Lavender Smith, Meredith Terranova, John Trent, Tim Tollefson, Coree Woltering

CONTRIBUTORS

Jenny Baker, Jared Beasley, Laura Presley, Gary Shaw

CONTRIBUTING PHOTOGRAPHERS

Paul Nelson, Gary Wang, Let’s Wander Photography, Joe McCladdie, Luis Escobar, Paul Encarcion, Geoff Baker Photography, Keith Facchino, Mile 90 Photography, Glenn Tachiyama, Matt Trappe, Scott Rokis, Howie Stern

PHOTOGRAPHERS

David Miller, Andrew Pielage, Jenny Thorsen, Jobie Williams

PRINTING AND CIRCULATION

Publication Printers, Denver, CO

SUBMISSIONS Articles, race reports and results, humor and photos should be submitted via email to amyc@ultrarunning.com. Unsolicited material is welcome, and will be used as space permits. Photo submissions are very welcome. Photographs should be available in high-resolution files (at least 1Mb, over 3Mb is better). Please label each photograph with: name of race/runners’ names/photographer’s name. Photos that depict effort, emotion, particularly unusual or difficult terrain or scenic courses, are especially welcome. Of course, the runners are the most important feature of an ultra, so remember to include them in scenic pictures, too! See ultrarunning.com for more examples of race reports.

MOVING FORWARD

JOE MCCLADDIE

Keep Moving,

I didn’t know how the day would go, but getting to run with someone I rarely see meant a lot and I wouldn’t have had it any other way.

IKO CORE

Featuring a patented AIRFIT headband that requires very little compression of the head, an ultra-thin lamp body, and a hybrid battery pack that is located in the back, The IKO CORE is practically imperceptible. www.Petzl.com/Running

or CORE

Rechargeable battery

1 = 900

AAA batteries CORE

Rechargeable battery

3 AAA / LR03 batteries

*The CORE battery is rated for three hundred discharge cycles under normal use, and each discharge cycle roughly represents the power capacity of three AAA batteries.

LESS WASTE, LOWER WEIGHT, AND MORE OPTIONS

HYBRID CONCEPT allows Petzl headlamps to run on either the CORE rechargeable battery or three AAA batteries without an need of an adapter.

• CORE rechargeable battery is an economical solution for frequent and/or intensive use

• AAA batteries are best for occasional use and offers a slightly longer burn time

Learn more at Petzl.com/Running

New 24-Hour Record

Lithuanian Aleksandr Sorokin ran 192 miles at Poland’s UltraPark Weekend

24 Hour race on August 28-29. Sorokin beat Yiannis Kouros’s long-standing 24-hour record of 188 miles set in 1997.

Weather Prompts Rescue at 50K

In its first ever event, the DC Peaks 50 in Utah had to rescue almost all 89 runners while they were out on the 50-mile, point-to-point course in the Wasatch Mountains due to high winds and 12-18 inches of snow. Runners were rescued by the Davis County Sheriff’s Office, over 100 race volunteers, local first responders and search and rescue volunteers. The race includes over 12,000 feet of elevation gain, climbing peaks that overlook Salt Lake City.

Dauwalter and D’Haene Prevail at UTMB

Courtney Dauwalter saw her second win at UTMB, nabbing a course record in 22:30:54, which was previously 22:37:26, set by Rory Bosio in 2013.

Camille Bruyas was second in 24:09:42, and Mimmi Kotka finished in 25:08:29 for third.

François D’Haene captured his fourth win in a time of 20:45:59, coming off his victory at Hardrock just a month prior.

Aurélien Dunand-Pallaz was just 13 minutes behind and came in second in 20:58:31.

Mathieu Blanchard came in third in 21:12:43.

Case Wins Tor Des Glaciers

Stephanie Case finished the 450k (283 miles) Tor des Glaciers in Courmayeur, Italy, finishing first female and third overall in 6 days, 11 hours and 6 minutes (155:06:55).

First place was tied with Jules-Henri Gabioud and Luca Papi both finishing in 5 days, 18 hours (138:18). The course traverses ridges across ancient glaciers in northwest Italy between France and Switzerland.

Accident at UTMB TDS

A runner from the Czech Republic was involved in a serious fall at 62k on the 145k UTMB TDS course on August 25, and passed away due to his injuries. Because of the accident, approximately 1,200 runners were instructed to

NEWS & NOTES

6 UltraRunning.com

turn around and return to the nearest aid station while 293 runners were able to continue to the finish. The race begins in Courmayeur, Italy, includes 29,885 feet of elevation gain on narrow, rocky terrain, and finishes in Chamonix, France.

Marathon Des Sables Death

A runner collapsed on October 4 during Stage 2 of the Marathon des Sables, a stage race that traverses the desert in Morocco. Runners carry supplies on their back for the 6-stage, week-long race. While the French runner was surrounded by other participants who were also doctors, along with a medical team who arrived within minutes of the medical alert, the male runner could not be revived. This is the third death in the race’s 35-year history.

New ITRA President

Janet Ng, co-director of the Vibram Hong Kong 100, has been elected to serve as the new International Trail Running Association (ITRA) president. Former president Bob Crowley resigned from the position after just over a year. He stated, “I have strived to guide ITRA to a better place than when I assumed the office. I believe together, we have achieved this goal. We have accomplished independence and steadied the organization through the disruptive times of the pandemic.”

Letters to the Editor

Dear UltraRunning Magazine,

As a transgender person and runner, I am writing to voice my concern for the article published in your latest issue titled "Transgender Athletes and Competition" by Tracey Beth Høeg MD, PhD.

This article intentionally or unintentionally reads as an argument against allowing transgender people to participate in running events and competitions. More importantly, though, the author's language and framing about gender and trans experiences is reductive and is damaging to trans people’s ability to safely and fully participate in running events.

While I understand that the author may not have intended to have this piece read asexclusionary, we cannot ignore the hurt and transphobia this article perpetuates.

Below I list the issues at hand with this article:

• Consistent use of biological essentialism throughout the article (whatever rules apply for biological women should apply for transgender women). This sort of essentialism reduces trans people to their bodies and hormone levels when we know trans experiences are so much more vast and layered.

• Language and wording perpetuates a harmful and false narrative that trans women are not women i.e. transgender women (born male).

• There reads to be an attitude that positions cisgender women as superior or more normal than transgender women (i.e. at what point are trans women biologically equal to (cis) women). Furthermore, by omitting the use of the word "cisgender" to preface "women" throughout the article, the author intentionally or unintentionally continues to perpetuate the idea that cisgender women are "the norm." Only pointing to the difference of trans women underlines and further ostracizes trans women/people as being "other."

• There is a confusing and vague portion of this article that is about "rare genetic disorders where women who appear female have testosterone levels considered normal for men" I believe the author (can't be sure since the author is unclear about

this) is talking about intersex people. Variations of sex characteristics are not rare – intersex variation occurs in an estimated 17 in every 1,000 live births (or 1.7%) – this is as common as babies born with red hair. Additionally, by calling intersex variations "rare," the author continues to render intersex people invisible which is dangerous since countless intersex people are already subject to dehumanizing and non-consensual genital surgeries to ensure their genitals "look correct" to gender assigned at birth.

I can understand that the author is making a case for "fairness for all." However, I ask, whose fairness is the author privileging or protecting? From how this article frames transgender athletes’ participation, I don’t believe the author wants fairness for transgender runners. She wants fairness for cisgender runners. “Fairness for all" has and will continue to privilege bodies and identities that control sport, social systems, politics and education in society. Marginalized people will continue to be marginalized until people in power relinquish their power and privilege to even the playing field. Until then, "fairness" will continue to work in favor of the privileged in running (i.e. cisgender, able bodied, middle to upper class, white athletes).

Transgender people have experienced incredible amounts of heartache, hurt and exhaustion from the countless attacks on our identity in the athletic world throughout history but especially the last two years. With over 50 anti-trans sports bills having circulated in the US and countless articles citing unfounded research on the “advantages” of transgender women in sport to ban trans women from competing, this is the time when running publications (if they truly believe in inclusion) need to take action against transgender discrimination and hate. I hope that UltraRunning Magazine can reflect on this piece a bit further, acknowledge the hurt this may have caused some readers, learn more about gender and the experiences of transgender people, and look to do better in the future.

Regards,

Lee Grabarek (they/he)

November 2021 7

Winner and course record holder, Courtney Dauwalter, reacts after her win at the 2021 UTMB. DAVID MILLER

WESTER N STATES 100-MILE ENDURANC E RUN ®

49TH ANNUAL RUN: JUNE 25 - 26, 2022 • PRESENTED BY:

NEVER

SOMETHING SO SIMPLE

COMPLICATED

Back in March, when Western States announced a change to its lottery system, we expected everyone to get it.

Well, everyone did get it. But, true to the granular lens runners use to look at our lottery, there were still lots of questions.

Per our new criteria: “Runners will no longer need to have consecutive qualifiers to keep their ticket count in the lottery. Each runner will keep his/her ticket count active after failing to get drawn in the annual lottery. The next time he/she qualifies and applies, regardless of when

that is, their ticket count will double per the WSER 2^(n-1) formula.”

Say your name is Jim and you live in Flagstaff. You previously qualified four consecutive years and did not get drawn in the most recent lottery. You had eight tickets in that lottery. The next time you qualify and apply to the WS lottery – regardless of whether that is the next year, 2025, or 2032 – your ticket count will be 16. See all the changes, including pregnancy deferrals, at: wser.org/lottery-changes

www.WSER.org

Race Director: Craig Thornley, RD@WSER.org

Joe McCladdie

...COULD BE SO

WE

THOUGHT

Improve Your Next Performance

BY IAN SHARMAN

One of the most enjoyable aspects in any pursuit is the satisfaction from learning and improving. This is a core part of ultrarunning, but it’s not easy – just think of friends who’ve had a repetitive issue ruin race after race. Helping runners with these problems is also a large part of my job as a coach, and I constantly think about this for my own running as well. Therefore, here’s a case study of the process I went through for my sixth Leadville Trail 100 this past summer.

The first step includes working out strengths and weaknesses from recent races. In my case, I’ve generally never had problems with the first two-thirds of an ultra, and my past few 100-milers have been paced well with a good level of fitness. For hot races, heat training was effective, and for events at high elevation, my altitude adaptation was nearly ideal. The main area that held me back was having issues with my stomach and not being able to consume calories. Part of that was a silly mistake in the 2019 Western States 100, using expired food that had been discontinued (should have been obvious in hindsight, but it was only a few months past the expiration date). Part of it was due to relying too much on sugary food because I had’t had significant stomach problems before, and I was taking it for granted that all would be fine no matter what I did.

Deciding on the right focus for training is the next step, by planning out the months pre-race to get the most bang for my buck. Given most things had gone well, there was no need to adjust much. Leadville has a combination of hiking at altitude and a lot of flat running, so I focused on getting into Oregon’s Cascade mountains a few times each week, including some marathon-style training,

and planning to have at least two weeks at high altitude before my race. I didn’t increase mileage compared to previous years, but aimed to feel good enough to do hard sessions well.

in splits was mainly in the last 25 miles. So, the aim on race day was to concentrate on a good process until then and not worry about the splits at all, then switch to using the poten-

I then looked at race-specific nuances from one year to the next, especially course changes. For the 2021 Leadville, pacers were allowed at mile 62 instead of being allowed over the big climb from mile 50 as in previous years. That meant planning for having the right food at the 50-mile aid station and enough calories to do a long gap between aid stations.

Closing out the race is the final key element to examine. In my previous races, this mainly came down to staying motivated and keeping everything on track to still be able to move well and not fade. Partly, that’s down to pacing and not panicking early on, and partly to having really good reasons why I’d care enough to push hard.

Overall, the race went relatively well (first masters and only 10 minutes slower than last time), but a couple of minor issues cost me almost an hour. Now it’s time to look at what needs to be improved. Nutrition was still a problem but this time I had the right mix of foods, however, I just didn’t have enough access to one type of fuel that kept going down well. Should be an easy fix for the next race, but it was still a costly mistake.

I also tried out different food options, including different gel brands, baby food packets and stroopwafels, which all went down well.

Looking at previous race splits, I saw that these were almost identical through the first 50 miles in all five of my prior Leadville runs, so I knew that the main target would be to get past the half-way point without having to push hard in order to have a sustainable race. Gaining a few minutes wouldn’t be worth it if it pushed the effort up even a little too high, and the variation

tial outcome (time and place) as a motivator only near the end. The next area to scrutinize is where time was lost or previously wasted. Aid station visits were fast with no more than about two minutes spent at each. I wanted to replicate that and discussed it with my crew and pacers. Time was lost in the previous Leadville race at mile 80 when I vomited, so that meant making sure I’d be especially dialed in for the quantity and variation of food from mile 50-80 to keep things sustainable. Luckily, there wasn’t much else to alter.

Hopefully you can get more out of your next event by using the steps above to analyze where you can improve. Plus, it should also reduce the length and amount of suffering –unless you like that kind of thing.

IAN SHARMAN is the head coach at Sharman Ultra and a podcast host. He has over 50 wins from 200 marathons and ultras, including four Leadville Trail 100 wins and nine consecutive top 10s at Western States 100.

November 2021 9 ULTRACOACH FROM THE COACH

ANDREW PIELAGE T

An Interview with Bruce Fordyce

BY ELLIE GREENWOOD

The word “legend” is often overused, but in the world of ultra-distance running, the 65-year-old South African Bruce Fordyce is truly a legend. He is the nine-time winner of the 89k Comrades Marathon, three-time winner of the London to Brighton road race, former 50-mile world record

your training evolve to help secure your first win?

In my earliest Comrades years (1977-78), the race was fairly low on the list of my priorities, holding less importance than partying at university, studying and pursuing some roles in student politics. In 1979, I decided to see what would happen at Comrades if I tried a bit harder. I started running twice a day and included some quality sessions. The results were beyond my wildest dreams. On an incredible day, I finished third and was only five minutes behind the winner, Piet Vorster. In 1980, I repeated the training program I’d used in 1979, but I also repeated the very cautious racing tactics. The problem is that in order to win, you have to be a bit bolder. I finished second to Alan Robb and learned a valuable lesson. In 1981, I increased my training a little, worked on my speed a bit more (lowering my 10k to sub-30 minutes and my marathon to 2:18) and also got used to leading small races which helped me understand the pressures of leading. An example of my training leading up to my first win in 1981:

Monday: morning 10k, afternoon 15k

holder (4:50:51 in 1983, held for 36 years until Jim Walmsley broke it by 43 seconds in 2019). But as Bruce’s website (brucefordyce.com) states, he speaks almost as well as he runs, so it was a pleasure to ask him some questions about his running career.

You first won Comrades on your fifth attempt, having worked your way up to third and second-place finishes in the years prior. How did

Tuesday: morning 10k, afternoon 400m hill repeats

Wednesday: afternoon 20-30k

Thursday: morning 10k, afternoon track session (1k repeats)

Friday: morning 10k, afternoon 15k

Saturday: cross-country club 12k race

Sunday: morning 30-60k

During your first win you wore a black armband to protest apartheid. I read this as being, “One of the proudest moments of your life.”

Yes – it is. Regrettably, in 1981, the Comrades Marathon was incorporated into the government’s celebration of 20 years of apartheid rule. There were tank parades, airplane flybys and speeches from politicians. Given that Nelson Mandela and hundreds of other activists were imprisoned, and in some cases tortured, and that millions of South Africans lived as second-class citizens, it seemed iniquitous that our race should become part of these very inappropriate celebrations. Many runners considered withdrawing from the race but some, like myself, wanted to run, so we decided to demonstrate our displeasure by wearing black armbands. We weren’t popular. I had tomatoes and eggs thrown at me while I was running, I was booed at by sections of the crowd and my small student flat was trashed. For at least a year afterwards, some runners would mock me and shout, “Where is your armband today?” I always responded to those jeers by pointing at my heart and replying, “It’s right here, in my heart.” But I won that day and took nearly eight minutes off the course record.

Did you have any favorite competitors at Comrades?

Alan Robb was a massive hero of mine when I started running. He was the reigning champion, the first runner to break 5:30, went on to win four times and run the race 43 times. In 1980 and 1982, we had two brutal races against each other where there was no quarter asked and none given. He and I are now good friends but we are polar

opposites: I am an extrovert and Alan an introvert. Alan will never mention that he’s a Comrades champion. While he was not a literal competitor, Wally Hayward is also a hero of mine. He won five Comrades Marathons in the 1930s and 1950s, and ran Comrades in 1988 in a time of 9:45, three weeks shy of his 80th birthday. You’ve run Comrades 30 times. Do you have a favorite non-winning memory?

During my 30th run, I caught Zola Budd and the two of us ran to the finish together. It was her first run. We were given a tumultuous welcome at the finish.

Are there any particular factors that you attribute to your longevity?

I raced ultras sparingly and cautiously – perhaps only one

10 UltraRunning.com

Fordyce crosses the finish at the 1986 Comrades Marathon, winning in 5:24:07.

ULTRA LIFE BALANCE ULTRACOACH

COURTESY BRUCE FORDYCE

The decorated Fordyce won the Comrades Marathon nine times. COURTESY BRUCE FORDYCE

or two 50-mile to 100k races per year.

You’ve had injury issues for a few years now. Are you still running, and do you still have racing ambitions?

Yes, I’ve lost all the cartilage in my right knee. I’m not in pain however, and I hobble quite quickly. I don’t plan to run another Comrades but it will be the 100th running of the Comrades in five years time, so you never know. I was a pacer for a mate at the 1985 Western States – it was such a special experience. I would love to visit the race again just

as a spectator, pacer or a guest speaker (hint, hint).

Running technology and training knowledge has changed a lot since your winning years. Do you think this has made running easier?

The current runners are not really running much faster than we were, but there are just more runners running well. Except for Gerda Steyn – her 5:58 up-run record (2019) is just mindboggling. In 1978, Alan Robb became the first sub-5:30 Comrades runner – he ran on Coke and water and wore very thin Tiger Boston shoes. That time would still win the Comrades in a slow year.

You’re the CEO of parkrun South Africa (parkrun.co.za). For someone who’s famous for running 18 times the

distance of parkrun, why are you so passionate about these 5k events?

Parkrun is a global phenomenon and I get so excited about seeing people running free 5k events every Saturday morning. It’s great to see people exercising and volunteering but more importantly, seeing communities getting together. In South Africa, we’ve grown from one parkrun to 225 parkruns with 1.2 million registered members.

ELLIE GREENWOOD is an online coach at sharmanultra.com. She is the current Western States course record holder, two-time IAU World 100k champ and has also won the Comrades Marathon in South Africa. A Scot turned Canadian, Ellie lives and trains on the trails and tarmac of North Vancouver, BC.

Fordyce set the world’s second-fastest time of 4:50:51 at the 1984 AMJA U.S. 50-mile championships in Chicago on an out-and-back course.

COURTESY BRUCE FORDYCE

Karl Meltzer’s Training

BY JASON KOOP

One of the inherent problems of being a coach to both normal and elite athletes is that the former group always wants to copy the latter. Particularly in today’s world of Strava and publicly available training information, it’s relatively easy for an athlete to look at almost any elite athlete’s training program and want to copy and paste it into their own training. So, with a mountain of hesitancy, I took this month’s theme of “Legends of Ultrarunning” and pondered chronicling the training of a legendary athlete. But it just didn’t seem relatable for this readership. Plus, the last thing I would want to happen is someone blindly copying the style and strategy of some elite athlete based on the words that follow.

Enter Karl Meltzer, who unequivocally is the everyman’s elite athlete and someone who has found a training style that is relatable and applicable to all. Fancy and flashy he is not. I guarantee that you will not find a Whoop strap, compression boots, massage gun or any clothing item with colors other than earth tones in his humble home near Alta, Utah. I will bet my entire 401k that he’s never set foot in a cryogenic chamber, had routine bloodwork done or even entertained the idea of such advanced interventions. If you do have the opportunity to sit down and talk running with “the winningest 100-mile runner on earth,” what you will find is someone who is humble, brutally honest and found a training formula that worked for him. That combination, in conjunction with Meltzer’s longevity which encapsulates over three decades of competitive running from his 20s to 50s, equates to a lesson for everyone in this

readership young, old, experienced and new, alike.

20s

& 30s: A LITTLE RUNNING, MOST OF IT HARD

Early in Meltzer’s career, running shorter, harder

who predominately utilize an 80/20 structure where 80% of their miles are easy and 20% are hard, not the other way around. As for the structure of that intensity, it was dictated by the terrain, not the stopwatch or a heart rate monitor. “Every

athletes. “And, I could continue to progress in my 20s and 30s by simply increasing my volume by about 10 percent per year,” which puts him at a maximum of about 65 miles per week and 15,000 feet of vertical for a standard week of

workouts and races were a staple. “I did these not so much because I wanted to, but because I could, because I could recover,” he told me emphatically. “Eighty percent of my volume was pretty hard.” By all accounts, this is the polar opposite of what nearly all elite endurance athletes do today,

uphill was hard. So hard I couldn’t hold a conversation.”

To continue the contrarian thread, the volume that Meltzer was speaking of in his 20s and 30s was a meager (by today’s standards) 35-50 miles per week, which is easily half or even a third of the weekly volume seen in today’s elite

training. “That did the trick until I was about 45.”

So, this is what I take away from my conversation with Karl Meltzer that everyone can learn from. You can start simply. You don’t need copious mileage or overstructured intensity in order to see results. A simple plan, where the intensity

12 UltraRunning.com ULTRACOACH KOOP’S CORNER

PAUL NELSON

comes from the terrain and the volume increases come at a rate of 10% per year can yield improvements for over a decade.

MID-40s: A CHANGE IN STRATEGY

“Until I was 45, mileage did the trick. Past that, I had to make some changes.” During Meltzer’s mid-40s and beyond, his mileage and intensity dropped, with more of a decrease in the latter. Fueled by a combination of age, physiology and a reduction in competitive pressure, Meltzer’s strategy shifted to one of opportunistic training. “Everyone has about 50,000 miles on their legs. I tried to make the most of mine.” Efficient training that is hyper-specific is the best way to describe Karl’s training during these years. “I always trained for the mountains, never on flats. Some of my training now is getting out and hiking, see how I feel, then I might run after that or just turn around and run back down.” Because he had trained so hard for so long, he could get away with less. “I knew how to race and that the race never starts until mile 70. So, I never had to be that fast. I just had to slow down the least.” On top of this was an acute realization that, although he could still be competitive, his best years were behind him. “I can’t top what I did in the past. I realized that and it helped with letting go of some of the training.”

The lesson here for the seasoned veterans reading this is that all of your training matters. It’s not just the last three months or six months, or even the last year of training that will determine how well you run ultramarathons. Provided that your training is reasonable in the short timeframe leading up to an event, you can lean on a lifetime of experience and training and be successful. You don’t have to be fast (particularly at the longer

distances), you just have to slow down the least.

“REST IS IMPORTANT.”

I know what you are thinking: everybody says this. But few people embrace this aspect of running like Meltzer has done over the course of his career. His old friend and

training program where they can improve. When I asked Meltzer what he would have done differently, even after several years of reflection, ever the contrarian, he answered simply, “I don’t know if I would have done anything differently. Sure, I made some mistakes and I learned the hard way from them. I accomplished a lot, and it’s hard to look back and say that I would have done better if I would have done more of this or less of that. I was very successful, and it’s hard to criticize that.” And I think he’s right. Above all else, Meltzer found a winning formula. One that consisted of low volume, high specificity and intuitively adapting to his needs over the years. He’s won a 100-mile race for 19 years in a row (and counting), a record that I firmly believe will never be broken. So, say what you

original training partner, Jim Hopkins, gave him these three important words in his 20s and they have stuck with him ever since. In fact, after interviewing Meltzer both on my podcast and for this article, it is clear to me that this advice permeates the entirety of his training from his overall mileage, to how he treats inju ries and even how to handle multiple 100-milers in a season (he won six 100-milers in 2006). “I get injured too, and as I’ve gotten older it’s harder to stay healthy and get over any injuries that I do get. So, I try to avoid them altogether with rest.” If you want to know if he does any preventive mainte nance, prehab or anything of the like, the answer is, “Nope, besides maybe drinking a beer.”

WHAT WOULD YOU DO DIFFERENTLY?

Elite athletes are always the reflective type. They are always looking for an edge to gain percentage here, add some mileage there and shave off a few grams from their pack for good measure. And even when they are successful, they can always find a hole in their

will about mega mileage and abundant vertical. Meltzer needed none of it. “Maybe a few less beers, that might have helped,” he jokingly concluded, proving that we all have our vices.

JASON KOOP is the head ultrarunning coach for CTS and author of Training Essentials for Ultrarunning. He coaches ultrarunners of all abilities and is the coach for many of today’s top ultramarathon athletes. He can be reached at jasonkoop@trainright. com and @jasonkoop (Twitter and Instagram).

JASON KOOP is the head ultrarunning coach for CTS and author of Training Essentials for Ultrarunning. He coaches ultrarunners of all abilities and is the coach for many of today’s top ultramarathon athletes. He can be reached at jasonkoop@trainright. com and @jasonkoop (Twitter and Instagram).

Epsomit.com All the benefits of an Epsom salt bath without the tub Use: ULTRA15 to save 15% The more fluid you become, the more alive you are.

November 2021 13

“I knew how to race and that the race never starts until mile 70. So, I never had to be that fast. I just had to slow down the least.”

Jesse

VelasquezNASM Personal Trainer

Becoming Legendary

BY MEGHAN CANFIELD

Legends exist in pretty much every facet of life, and the sport of ultrarunning is no exception. To help separate the latest and greatest visitor to the scene from the lasting heroes of our sport, here is a short list of the names that are those of legendary status. Full disclosure, this is my personal definition of a legend: an ultrarunner who, over the years, has completed, podiumed or won many races, shown good character/sportsmanship, contributed to the sport in numerous ways such as race directing, volunteering at races, coaching, mentoring, participating in panel discussions and continued to engage in the ultrarunning community well past their fastest years. Bear in mind that this is my personal list, it is nowhere near complete and it is definitely Western States biased.

GORDY AINSLEIGH

Ainsleigh was the first person to finish the Western States Trail Ride 100 on foot in 1974, thus giving birth to the Western States Endurance Run. Gordy has remained involved with the race ever since, and can often be seen giving free chiropractic adjustments to runners at local races.

and volunteers at races, and can announce finishers from the booth at Western States without a microphone.

SCOTT JUREK

Jurek had seven consecutive wins at Western States, as well as wins at Hardrock 100, Spartathlon, Badwater and many more. He has authored two books related to running and continues to be involved in the sport.

MAGDA LEWY-BOULET

Lewy-Boulet was an Olympian in the marathon and has won Western States. She has won a number of ultras, is a coach, works for GU Energy, volunteers at races and serves on the board of directors for Western States.

SCOTTY MILLS

and generous human. She has won Western States once and UTMB twice, where she now holds the course record. She has won Tahoe 200, and also has competed for Team USA at the 24-hour World Championships. I have witnessed her generosity and humility time and time again. She is a superstar, approachable and exudes positivity while racing. Fans young and old ask for selfies and her autograph, and she not only obliges, but asks each of them their names, showing a real interest in each of them. In my opinion, this woman is incredibly good for our sport and I envision her remaining involved with ultrarunning for decades.

TIM TWIETMEYER

Twietmeyer is a five-time winner of Western States and has 25 sub-24-hour finishes. He has contributed hours on the trail, volunteered at aid stations, has crewed and paced runners and serves on the Western States board of directors.

ANN TRASON

Trason was undefeated in her 14 finishes at Western States. She ran for many years, becoming a race director and a coach. She took up walking ultra-long distances late in her career.

ELLIE GREENWOOD

Greenwood has two wins at Western States and holds the course record for women. She’s been the World Champion at the road 100k, won the Comrades Marathon and holds several course records. She stays very active in the sport with coaching, writing, volunteering and mentoring.

ANDY JONES-WILKINS

AJW has 10 Western States finishes all under 20 hours, and came in second place in 2005. His passion for running ultras oozes from his pores. He coaches, mentors

Mills has 20 Western States finishes and 10 Hardrock finishes. Some of those were completed when Scotty was in his 60s. He was the race director for the San Diego 100 and has volunteered hundreds of hours for the sport.

CRAIG THORNLEY

Thornley is a race director and nine-time finisher of Western States. He has many other ultra finishes, and the amount of time and energy he puts into his race directing is likely unsurpassed. His mission in doing so is to create the best possible experience for every runner.

My top pick for an up-andcoming legend is Courtney Dauwalter. She crept into the ultrarunning scene a few years ago. No fanfare, just a lanky gal in long shorts, a baggy top and an amazing smile. And it turns out she is very fast. As Courtney’s race resume grew so did her reputation as a downto-earth, grounded, humble

Finally, there is the local legend. You all have one or more where you live, and for your new ultrarunning career, these are the folks you want to seek out for advice on where to run, where to find a coach, what the local races are and how to find the group runs. One of Auburn’s local legends is Martin Sengo. He can often be found at our local running store when he joins or leads group runs, mentors new runners, volunteers at races when he isn’t running in them, supports and encourages everyone and has become a race director himself. He is a mid-pack runner and possibly has more followers on Strava than anyone in town. Everyone knows Martin.

My ask is that on your journey into ultrarunning, stay long and become legendary. Dig in, volunteer, start a group run, invite, include and help grow our sport with kindness and generosity.

“AJW”

MOVIN’ ON UP 14 UltraRunning.com ULTRACOACH

MEGHAN “THE QUEEN” CANFIELD and her farm animals live in Corvallis, OR, where she works as a virtual coach at coachmeghan.com. She’s a four-time Olympic Marathon Trials qualifier and has 10 top-10 finishes at Western States 100.

Montrail: The Original Trail Brand & Team

BY SEAN MEISSNER

This year celebrates the 25th anniversary of the first ultrarunning team in the US (and probably the world). One Sport’s origins go back to the early 80s in Europe as an off-shoot brand that specialized in boots, including mountaineering and hiking boots and shoes. In the mid-90s, they created one of the world’s first trail running specific shoes, the beloved Vitesse.

One Sport US was based in Seattle, and their original trail running team was created in 1996 and managed by their Northwest sales rep, Scott McCoubrey. The team included legends such as Dave Terry, Rob Lang, Sally Marcellus, Jim Kerby, Brandon Sybrowsky, Adam Chase, Dave Mackey and Ben Hian. Their shoe of choice: the Vitesse.

In 1997, One Sport became Montrail and really wanted to grow beyond its Northwest roots to a national level. They did this by creating a community through sponsoring races, giving away shoes as prizes and selecting athlete ambassadors.

McCoubrey packed up some Montrails and headed south to California to help with the Way Too Cool 50K and American River 50. While there, he created the Nor Cal Montrail Team, including Tim Twietmeyer, Rick Simonsen, Suzie Lister, Mo Bartley, Luanne Park and Kevin Sawchuck.

He then headed to the Vermont 100-mile where he found Ian Torrence sleeping in his car. McCoubrey offered Ian a bed, some shoes and a spot on the team. As McCoubrey traveled back and forth across the country to help at races and give away shoes, Team Montrail kept growing with the then-current “Who’s Who” of

ultrarunning: Scott Jurek, Kirk Apt, Stephanie Ehret, David Horton, Courtney Campbell, Sue Johnston, Eric Clifton, Karl Meltzer, Dusty Olson and Dink Taylor, among others.

Team Montrail athletes all became very close friends during this time of growth, and that really helped to develop a culture within the sport. It also set a precedence for other brands as they began marketing. Everyone had to have a team of runners.

It was about this time in 1998 that Patagonia launched their Endurance Line. After seeing the success that Montrail was having within the trail running world, Patagonia’s Jeannie Wall approached McCoubrey to partner with Montrail to support athletes and events. This gave both companies more to offer to their team and event marketing, and thus, Team Montrail became “Team Montrail Patagonia.”

In 1999, McCoubrey left his job at Montrail and opened Seattle Running Company. As Montrail was a Seattlebased company, and with McCoubrey’s history with Montrail, SRC quickly became the running store for all things ultra and Seattle was the ultrarunning capitol of the US. The staff included Jurek, Krissy Moehl and Hal Koerner. Ian took over McCoubrey’s job at Montrail to manage the team and marketing efforts for a couple years, and when he left, Krissy was hired to manage the team. It was under her direction that Team Montrail Patagonia really grew in size and reputation.

Columbia Sportswear purchased Montrail in 2006, and everything was moved to Columbia’s headquarters in

Beaverton, OR. This drastically changed the team and brand, as the team size was slashed from well over 100 runners to about 20. Of course, there was also an immediate conflict of interest in having Patagonia as the clothing sponsor for the team, so that partnership went away.

In 2008, Columbia (wisely) decided to put Montrail under Mountain Hardwear’s management in Richmond, CA (Mountain Hardwear is also a Columbia-owned company). This turned out to be an excellent move, as Mountain Hardwear “got it” when it came to endurance sports, much more so than Columbia. Topher Gaylord was hired as president of Mountain Hardwear / Montrail, and under his leadership, the brand once again was on the upswing.

Several different people managed Team Montrail / Mountain Hardwear over the next decade, and the team stabilized at around 20 athletes including Ellie Greenwood, Geoff Roes, Annette Bednosky, Dakota Jones, Amy Sproston, Gary Robbins, Max King and Matt Hart. It was a solid, fun team and they were winning big events, including running women’s and men’s course records at Western States, and women’s and men’s victories at the World Championship 100K. New, lightweight shoes were created in the Rogue Racer and Rogue Fly, as well as more traditional shoes such as the Bajada, Rockridge and Fairhaven, plus Montrail’s super popular Molokai and Molokini flip-flops.

After a seven-year run of being managed by Mountain Hardwear, Columbia decided to bring Montrail back to Portland to be managed and operated, rebranding their

trail running line as Columbia Montrail. In order to bring more attention to the new name, Columbia Montrail started investing in UTMB, becoming the title sponsor for the largest trail ultramarathon festival of events in the world.

After a couple of years, more big changes came for Team Montrail, namely, the size was again slashed, this time to about a half dozen athletes, and the team manager position was quite fluid for a few years.

Looking at Columbia’s website of their current Montrail line isn’t super promising for the Montrail name, as there are only two Montrailspecific trail shoes. Columbia Montrail athlete Yassine Diboun told me earlier this year that there are some new shoes coming, so I’ve been anxiously awaiting to see what’s in store.

In 2003, Krissy selected me to become a member of Team Montrail Patagonia. I was fortunate to be able to call myself a Montrailian for 16 years, riding many of the highs and lows of the company, brand and team, along the way. Being on the team changed the trajectory of my life, both professionally and personally, and the friendships I made because of that change are some of the best of my life, for which I am grateful.

Long live Montrail.

SEAN MEISSNER has been coaching runners of all ages and abilities, and distances and terrain since 2002. He is the founded of the Peterson Ridge Rumble and has over 250 ultra and marathon finishes. Sean coaches through Sharman Ultra, and works and plays, mostly with his dogs, in the mountains surrounding Fruita, CO.

November 2021 15 ULTRACOACH TRICKS OF THE TRADE

Guidelines for Reading & Interpreting Sports Science Research

BY MATT LAYE

The goal of this column when I started five years ago was to take existing research in the world of ultrarunning and endurance sports and make it translatable. It’s a lot of fun and I always learn something new. However, it’s often limited to one topic per issue and perhaps sometimes, it’s not a topic that you’re interested in. This month I want to provide you, the educated reader, some tips on how to be better consumers of scientific articles and therefore, feel more comfortable seeking out the information you are most interested in. Specifically, I’ll describe different types of studies and

some things to be aware of when reading each of them.

First, where to find these articles. The gold standard is pubmed.com which compiles articles from biomedical journals, and has some nice filter options as well. So, once you are on the site and enter your favorite ultrarunning topic, how do you know what articles to read first and which have the highest level of evidence?

The best place to start in a topic is with review articles. Review articles are typically written in the most colloquial language with the least dense statistics and methods to dig through, and they themselves aren’t doing any additional

studies, but collating the existing research on a topic. Broadly, review articles come by three different names: narrative reviews, systematic reviews and meta-analysis, all of which you can filter. A narrative review is like a story told by the existing scientific literature that might wander a little and might even have an explicit point of view or hypothesis it’s seeking to explore and discuss. An example is an article on whether success in ultras is more nurture or nature (4). A systematic review (8) has strict guidelines of what articles and topics are being reviewed (no cherry-picking allowed) and often tries to synthesize it into a table or few takeaways in a consistent and yes, systematic, way which makes it less subjective, higher evidence, than a narrative review. A meta-review (7) is similar to a systematic review, but on a topic that has a sufficient number of papers on the topic that additional statistical conclusions can be made. The meta-review is probably the hardest of this group to read, but also has the highest level of evidence and provides the most certainty of any of the review approaches. Reviews are also a great place to find links or references for the articles in which the primary science was done.

Randomized control trials (RCT) are considered the gold standard of intervention research. The RTC approach to research consists of a homogenous group of people randomized to receive either a intervention/pill/supplement/ etc versus a placebo (example (3)). RCT ensure that we can attribute any of the changes in the outcomes of interest (like VO2max, race performance, body composition, injury rates, etc) to the intervention (training, supplement, prehab

work, diet, etc). However, not all randomized control trials are of high quality. Some RCT red flags are when the intervention itself is of questionable quality. For instance, using a less than effective dose of supplement that is insufficient to cause physiological changes, using a training protocol that doesn’t result in well-known training adaptations or even an intervention with low adherence such as a super strict diet or rigorous training protocol. All of these can temper our interpretations of RCTs. Moreover, sample sizes are often small in exercise trials and therefore, any results both negative and positive should be considered skeptically and always benefit from replication from another research group. Lastly, make sure that the outcome of the study is meaningful – both in what they measured and the degree to which it changed. For instance, measuring a 3k time

Randomized control trials (RCT) are considered the gold standard of intervention research. The RTC approach to research consists of a homogenous group of people randomized to receive either a intervention/pill/ supplement/etc versus a placebo.

ULTRARUNNING SCIENCE 16 UltraRunning.com ULTRAGEEK

HIERARCHY OF RESEARCH DESIGNS & LEVELS OF SCIENTIFIC EVIDENCE

Clinical Practice Guidelines

Meta-Analysis

Systematic Reviews

Randomized Controlled Trial

Prospective, tests treatment

Cohort Studies Prospective: cohort has been exposed to a risk, Observe for outcome of interest

Case Control Studies Retrospective: subjects have the outcome of interest; looking for risk factor

Case Report or Case Series

Narrative Reviews, Expert Opinions, Editorials

Animal and Laboratory Studies

SECONDARY, PREAPPRAISED, OR FILTERED STUDIES

References

OBSERVATIONAL STUDIES

PRIMARY STUDIES

NO DESIGN NOT INVOLVED W/ HUMANS

Based on ability to control for bias and to demonstrate cause and effect in humans

trial performance might not be important for ultrarunners, just like seeing a 30-second improvement in a 100-mile race is probably not that meaningful.

Learn to differentiate the types of non-randomized controlled trials. Longitudinal studies are not RCT, but describing people in detail and then following them for a long period of time does provide valuable insights. Longitudinal studies can group people based on different diets, training approaches, ages, fitness levels or anything and follow to see what happens over a period of time, whether that be years or simply the time it takes to run a race (6). Retrospective studies are where researchers look backward and try to see what might explain a current observation (being on the podium versus back-of-the-pack), and cross-sectional studies look for differences that might explain a certain trait at a single time point, such as seeing whether current strength is related to the likelihood of being injured or whether current diet is associated with a specific

body composition. Both retrospective and cross-sectional approaches are more prone to bias and spurious correlation, but provide important research insights and serve to support existing RCTs as a foundation to base further research. As a connoisseur of research with some work, you’ll be able to differentiate longitudinal, retrospective and crosssectional studies and recognize the strengths and limitations of each.

Other studies are interesting but are less generalizable to you, me or really, anyone else. For instance, animal studies include the collection of tissue and measurements that allow researchers to causally identify molecular or physiological mechanisms. But making a mouse faster or stronger seldom translates to human physiology. Similarly, a case study about one individual can be very insightful (1), but additional testing in more people is necessary given the large individual variability for most physiological traits and responses.

With that, I hope you feel empowered to explore the scientific literature on your own. As with anything, the more time you spend at it the better you will become at sleuthing out and differentiating good from poor studies. Next month, I hope to discuss how to identify misleading statistics and why significant might not mean what you think it does.

MATTHEW LAYE is an Assistant Professor in Health and Human Performance at The College of Idaho. When he is not teaching he is coaching athletes for Sharman Ultra, plotting the next experiment or running. You can follow him on Twitter @mjlaye.

1. Grosicki GJ, Durk RP, Bagley JR . Rapid gut microbiome changes in a worldclass ultramarathon runner. Physiol Rep 7: e14313, 2019.

2. Johnson SL , Stone WJ, Bunn JA , Lyons TS, Navalta JW. New Author Guidelines in Statistical Reporting: Embracing an Era Beyond p < .05. [Online]. Int J Exerc Sci 13: 1–5, 2020. /pmc/articles/ PMC7523905/ [1 Sep. 2021].

3. Kasprowicz K , Ratkowski W, Wołyniec W, Kaczmarczyk M, Witek K , Żmijewski P, Renke M, Jastrzębski Z , Rosemann T, Nikolaidis PT, Knechtle B. The Effect of Vitamin D3 Supplementation on Hepcidin, Iron, and IL-6 Responses after a 100 km Ultra-Marathon. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17, 2020.

4. Knechtle B. Ultramarathon runners: nature or nurture? Int J Sports Physiol Perform 7: 310–2, 2012.

5. Monaghan TF, Rahman SN, Agudelo CW, Wein AJ, Lazar JM, Everaert K , Dmochowski RR . Foundational Statistical Principles in Medical Research: A Tutorial on Odds Ratios, Relative Risk, Absolute Risk, and Number Needed to Treat. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18, 2021.

6. Nguyen H-T, Grenier T, Leporq B, Le Goff C , Gilles B, Grange S, Grange R , Millet GP, Beuf O, Croisille P, Viallon M. Quantitative Magnetic Resonance Imaging Assessment of the Quadriceps Changes during an Extreme Mountain Ultramarathon. Med Sci Sports Exerc 53: 869–881, 2021.

7. Rubio-Arias JÁ , Andreu L , MartínezAranda LM, Martínez-Rodríguez A , Manonelles P, Ramos-Campo DJ. Effects of medium- and long-distance running on cardiac damage markers in amateur runners: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and metaregression. J Sport Heal Sci 10: 192–200, 2021.

8. de Waal SJ, Gomez-Ezeiza J, Venter RE , Lamberts RP. Physiological Indicators of Trail Running Performance: A Systematic Review. Int J Sports Physiol Perform 16: 325–332, 2021.

November 2021 17

Where is Your Mind?

BY PETE KOSTELNICK

Both of the times I ran across the US, I got asked a lot of the typical questions. “How much do you eat?” and “How many pairs of shoes have you gone through?” These are questions you might expect. These are all straightforward questions that get answered with very measurable and honest answers. However, I’ve found in my own investigation that the most fascinating and perhaps personal question you can ask an ultrarunner is, “So, what do you think about during all those hours of running?” This question is difficult to answer in under 30 seconds, because I honestly think of everything to a degree. What fascinates me about this question is not so much the what, but the how. How do you think while running?

The way I like to rationalize it, taking part in an endurance sport provides you the ability to truly run free with your thoughts. We might stop for a few minutes here or there during the day as we look away from a computer, TV, phone or the person we’re talking with to let our mind wander. But it’s usually not for very long. I’m mostly serious when I say half of the reason I run ultramarathons is to get away from my phone. I’ve noticed while I’m out running that my state of mind falls across three different spectrums: positive vs. negative, present vs. elsewhere and logical vs. emotional. Just like training my heart in different zones, I’ve found it useful to train my mind across these dimensions.

Hopefully most of our runs are in a positive state of mind. However, it’s inevitable that thoughts can shift to negative, whether it’s something you’re dealing with in the “real world” or struggling to get from point A to point B in an expected time. Certainly, during a race

your mind will trend negative if you’re asking your body to deliver as much as it can, so it makes sense to participate in a little negativity in training as well. I usually don’t have a problem finding training runs that go sour and turn negative, but a very positive friend of mine likes to put a rock in his shoe to enhance the negative feelings while training. I think there is some merit in purposely forcing yourself past the edge of your comfort zone in some way without necessarily going physically overboard. There are often things that happen on race day outside of our control that can be spun negatively, so being prepared to run on negative can be a positive.

When it comes to being present vs. elsewhere during a run, I’m usually elsewhere. I’ve been blamed for not saying hi to friends and not being aware of my surroundings while running on many occasions. It’s not on purpose, it just means my mind has completely

wandered off. I’ve noticed that “being elsewhere” during a run can be productive on multiple levels, and I find that during a race I can deal with fatigue better when I’m not thinking about each step hitting the ground. I also rarely dread knocking out long, boring runs when the track or treadmill come calling, because I know I can mentally leave these venues behind.

Humans are emotional creatures and unfortunately, emotions use up essential energy and cause us to make bad decisions (i.e., run too fast) in ultrarunning. On the other hand, almost any reason to run a marathon leans toward emotion over logic, creating a catch 22. I’ve found one thing in common in most great ultrarunners, and that’s their ability to remain logical while running, regardless of the situation. Whether they haven’t slept in over a day or just threw up what they ate, they save all their emotional ammo for when they really need it—the home stretch or when they need to convince themselves that their race isn’t over just yet.

If you’ve struggled like me to pinpoint why a certain run or race went better or worse than expected, the missing piece may very well be what your mental state was, what kind of thoughts were running through your head and how you arrived at those mental destinations. For example, I’ve always struggled with what my high school tennis coach called tanking, so I try to always be aware of my tendency to exaggerate negative states of mind when things aren’t going well to salvage a race from disaster. I can be disappointed at the end result, but I try to save negative thoughts for post-race and remain focused on the “mission.” I also notice that since I started wearing a

GPS watch five years ago, I can gravitate toward becoming too present in my surroundings simply by looking at my watch too often. Therefore, one thing I’ve worked on is using my watch as occasional confirmation instead of allowing it to become the metronome. I’ve found better outcomes when letting my mind go with my instincts dictating the pace.

Music plays a big part in almost everything I do. Even if it’s a terrible song stuck in my head, which it almost always is, having a natural rhythm running through my mind that is in sync with the effort level which feels right is the best way I’ve found to dial in a sustainable mental calm during races. When it comes to actually listening to music, I usually find myself spending too much emotional energy for it to become sustainable for more than a few songs in both training and racing. On the other hand, listening to comedy podcasts while training keeps things unemotional and positive.

There are a lot of tricks to training your mind and in our world today, it’s never been more important to use them to your advantage. With negative and emotional distractions everywhere, it’s easy to let your mental game become shattered and fragmented by outside forces. Recognizing which mental states you run best in and how to navigate those can be a game changing superpower.

PETE KOSTELNICK is a numbers guy from northeast Ohio who finds balance as a HOKA ONE ONE and Squirrel’s Nut Butter athlete, specializing in races of over 100 miles and occasionally finding time to cross continents on foot. He is also a coach with the Chaski Endurance Collective.

18 UltraRunning.com ULTRAGEEK PETE’S PERSPECTIVE

I’ve noticed while I’m out running that my state of mind falls across three different spectrums: positive versus negative, present versus elsewhere, and logical versus emotional. Just like training my heart in different zones, I’ve found it useful to train my mind across these dimensions.

The Number 100

BY GARY DUDNEY

I love the idea of doing a 100-mile race on the anniversary of 9/11. It will give me a chance to do something special and positive on that day, and it will also give me a wonderful backdrop for reflecting on these last 20 years of my life, which I consider, in my case, something of a special gift. In the fall of 2001, I was accompanying my son to his first year of college on the East Coast and the initial plan was for me to drop him off and then fly home on United flight 93 from Newark, New Jersey, to San Francisco, California. The date of that flight was to be Tuesday, 9/11/01.

The plan changed, however, when my son was offered a chance to come out a week early, meet a group of new classmates and do some outdoor activities with them. Consequently, we traveled a week earlier, and I returned home without incident on Flight 93 on Tuesday, 9/4/01. Exactly one week later I stood in front of a television and learned that Flight 93 had crashed in Somerset County, Pennsylvania, after the passengers on board had tried to overcome the four hijackers who had taken control of the plane. Thus was born my conviction that these last 20 years have been a gift.

Part of what I did with that gift was to run a lot of 100-mile races. The Virgil Crest 100 will be the 86th time I’ve started a 100-mile race. If I stay on schedule, my 100th start will fall about mid-year in 2023. It will be a big deal for me facing up to that challenge yet again for the 100th time knowing full well what hell often ensues. I didn’t set out to run a hundred 100s. It just happened in the course of finding so much joy and satisfaction in running that distance over and over again. I’ve compounded the joy and

adventure by also setting out to run a 100-mile race in every state. Thus, I’ve traveled widely and sampled a

known, but exceptionally well-managed and enjoyable races. Of the 85 I’ve done, I’ve run 65 different races. Not intentionally having the goal of running one hundred 100s is a common theme among the 19 runners who have officially finished a hundred 100-mile races. (Davy Crockett has documented the phenomena of running a hundred 100s in an article and podcast that can be found on his website ultrarunninghistory.com.) Many of these runners described just piling up 100-mile finishes until one day, realizing they were close, they decided to make 100 finishes a goal. That’s my story as well, but I should note that I’m well shy of joining this elite group. I’ll hit 100 starts in 2023 but only official finishes count under Crockett’s criteria. DNFs don’t count, self-supported non-organized runs don’t count, completing the 100 miles and even being awarded a belt buckle doesn’t count if you didn’t make the final time cutoff, and of course

incomplete races caused by cancellations or some other circumstances beyond your control don’t count. I was once pulled from a race for missing a cutoff only later to find out that a mistake had been made and I’d reached that aid station under what should have been the cutoff.

My enthusiasm for this quest hasn’t waned one bit as time passes. I’d happily chase after 100 finishes even if I were only halfway there, but the fact is, I’m no longer a spring chicken. I’ll turn 69 soon. How long will it be before running 100 miles is beyond me? It is hard to say. But even this race between advancing age and knocking down those last 100-mile finishes is intriguing. If the outcome were certain, the struggle to get there would not be nearly as interesting. Like with so many things, it is the possibility of failure that imbues this goal with so much excitement and will give it so much meaning if I were to win through against the odds and achieve it.

Something else that I’ve done since ducking that bullet on 9/11 was to get serious about writing. I’d dabbled at

writing all my life but I made a conscious effort to use my 20-year gift to really get focused and write more about running. Two books resulted, The Tao of Running and The Mindful Runner, as well as a very long stint writing as a columnist for UltraRunning Magazine. In fact, wouldn’t you know it, the column you’re reading right now is rather auspicious; it’s column number 100.

GARY DUDNEY has been writing about ultrarunning for nearly 30 years. He’s finished close to 200 ultras, including over sixty 100-milers, but still finds every race a fresh and thrilling experience. He has written two books, The Tao of Running and The Mindful Runner.

November 2021 19 ULTRAGEEK RUNNING WISE

The Silent Pandemic of Unhealthy Air

BY TRACY BETH HOEG MD, PHD

The West Coast saw another bad fire season in 2021, and we can only expect this to increase in the future. Summer wildfire frequency in the United States has escalated 18-fold between 1972 and 2018, with a five-fold annual increase in area burned (Chen, 2021). We know that poor air quality has negative health impacts, but we also know that lack of exercise is detrimental for our bodies. What many athletes are not discussing is this: at what point does lack of exercise become worse than exercising in bad air? Not getting out to exercise one day is no big deal, but what about a majority of the summer? Practicing medicine in Northern California, I have seen one patient after another who has explained that they stopped getting in their hikes/ run/rides because of so many days with poor air quality, and then just never started again. For these patients, I wonder, “Would it not have been better for them to actually just get out on some of the questionable air quality days rather than finding themselves in a place where they have gained weight/become depressed and are entirely out of the habit of getting exercise?” This issue has also grown even more in magnitude during the last two years with many fitness centers either being closed or people avoiding them due to concerns about COVID-19.

A recent study (Guo, 2020) provided some insight. In Taiwan, both high levels of particulate matter exposure and no physical activity were associated with decreased lung function. However, those who exercised the most saw the smallest decrease in lung function among all of those exposed daily to high levels of air pollutant. It’s important to note

FIGURE 1.

that this was mostly outdoor exercise as <10% of Taiwanese report exercising indoors (DOPEME, 2017). But still, the combination of good air and high/vigorous exercise was the best at least in terms of FVC (forced vital capacity) or the amount of air a person can exhale.

The moral of the story is exercise and good air is the best, but in settings of continuous bad air, the people who got out and exercised saw the lowest decreases in lung function.

While the study above addressed lungs, another research group in Taiwan found that regular physical exercise also attenuated inflammatory markers independent of levels of air pollution (Zhang, 2018). These studies together still don’t give an overall picture of health benefits vs. risks of bad air and lack of exercise, but give one reason to pause about imposing too long of a stretch of being sedentary due to bad air.

Another epidemiological analysis from Holland (Hartog, 2010) found that the benefits of regular cycling outdoors greatly outweighed the risks of increased exposure to air pollutants. A Danish study found that the associated beneficial effects of exercise were not attenuated by high levels of exposure to N02 (Andersen, 2015). What we don’t have is study of regular exercise indoors vs. outdoors in settings of high levels of air pollutants, though there is little doubt that cleaner air is better.

Increased risks of heart attack or arrythmia while running or exercising has been a theorized concern, but no studies have definitively demonstrated this (Giorgini, 2016). However, one study

showed that some people with heart disease developed EKG changes while exercising in poor air. Furthermore, the risk these so-called “ST- segment changes” on an EKG decreased if the subject was wearing a mask exercising in the bad air (Giorgini, 2016). One review article in Nature recommends surgical masks over cloth masks in smoky or polluted conditions given cloth masks may actually concentrate particulate matter and increase exposure (Holm, 2021).

There is some consensus (Reynolds, 2020) that exercise in the Orange (or an AQI of <150 ) is acceptable enough for the benefits of outdoor exercise to outweigh the harms. In terms of collegiate sports, the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA, 2021) recommends shortening outdoor exercise duration when the AQI is >150. It is not until an AQI of >300 that they recommend either moving the event indoors or canceling if that is not possible.

Some runners reading this may know they are in a sensitive group and, having spent many a day exercising in bad air around Tahoe this summer, I know first-hand that performance is impacted. I don’t think any runners doubt this. But this is also borne out in the research – that athletic performance is consistently impaired in bad air quality. (Giorgini, 2016).

Increased levels of PM 10 (inhalable particles, with diameters 10 micrometers or smaller) are correlated with slower marathon finishing times, significantly so in women, and one can see the same trend in men (though it was not found to be significant in this study) (Marr, 2010).

% DIFFERENCE IN FVC 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 Inactive Low Moderate High-Vigorous PHYSICAL ACTIVITY 1st 3rd 2nd 4th PM 2.5

20 UltraRunning.com ULTRAGEEK ULTRA DOC

Figure 1. Lung function as a product of amount of exercise and amount of particulate matter in the air (4th PM 2.5 being the highest)

FIGURE 3. L

The above study did not subdivide PM 10 into even finer particles of PM2.5 and UFPs (ultra-fine particles), which are less than 2.5 and 0.1 microns, respectively. The ultra-fine particles are of greatest concern as they are so small they can be directly absorbed into organs and have been associated with increased heart disease, stroke and premature death

(Schraufnagel, 2020; IQ Air, 2021). These are unfortunately found in wildfire smoke. It would stand to reason that the more frequently one breathes, the more particles are absorbed, but this is still not known for certain. In terms of exposure to light, medium and dense amounts of smoke, exercising or not, there is a clear dose response relationship: the more

FIGURE 3. R

exposure, the more heart and lung problems one develops. This is seen most clearly in adults over age 65.

A recent review of multiple studies (Heo, 2021) described very concerning associations between suicide and PM 2.5 , PM10, NO2 , and NO2 , with weak evidence for O 3 , SO2 , and CO. Whether this is a direct effect of pollutant exposure or

AIR QUALITY INDEX

the indirect effect of less time outside/exercising/in the sun is not certain. However, this is simply one more troubling aspect of the “silent pandemic” of increasingly smoky and polluted air.

It is, however, clear (so to speak) that on days with high air quality index, certainly over 300, that it is best to cancel events and move things

Air quality is satisfactory and air pollution poses little or no risk

Air quality is acceptable. However, there may be a risk for some people, particularly those who are unusually sensitive to air pollution

Member of sensitive groups may experience health effects

The general public is less likely to be affected

Some members of the general public may experience health effects; members of sensitive groups may experience more serious health effects

Health alert: The risk of health effects is increased for everyone

Health warning of emergency condition; everyone is more likely to be affected

AQI Category and Color Good Green Moderate Yellow Unhealthy for Sensitive Groups Orange Unhealthy Red Very Unhealthy Purple Hazardous Maroon Index Value 0-50 51-100 101-150 151-200 201-300 301+ Description of Air Quality

% OFF COURSE RECORD -5% 5% 10% -10% 0 10 20 30 40 150 PM ¹ 0 (ug/m ³ ) 0% // // R ² = 0.33 p < 0.05

% OFF COURSE RECORD -4% -2% 2% 4% 6% -6% 0 10 20 30 40 150 PM ¹ 0 (ug/m ³ ) 0% // //

November 2021 21

Figure 3. Levels of particulate matter (PM)10 and percentage off of marathon course records for women (left, significant correlation) and men (right, insignificant correlation)

ALL-CAUSED CARDIOVASCULAR

ALL-CAUSED RESPIRATORY

April 2016 - Volume 36 - Issue 2 - p 84-95 doi: 10.1097/HCR.0000000000000139