OF FATEMA

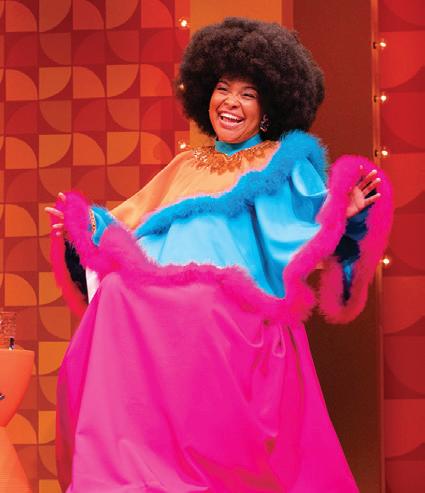

STAGING A REVOLUTION

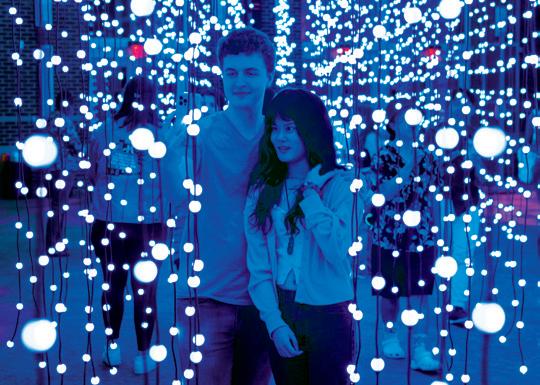

Whether reimagining a theater as an indoor skate park, getting into character as a fictional Hollywood groundbreaker or pouring molten metal into sculpture molds, Terps have endless opportunities to explore and innovate in the arts. The NextNOW Fest each fall is just one of the chances students have to create and take in dance, music and immersive visual art experiences. And the new Arts for All initiative brings together the arts, technology and social justice to spark innovation and new ways of thinking.

PHOTOS BY DAVID ANDREWS, JOHN T. CONSOLI, LISA HELFERT, DYLAN SINGLETON AND MADISON WELLS-JAMES ’23

PHOTOS BY DAVID ANDREWS, JOHN T. CONSOLI, LISA HELFERT, DYLAN SINGLETON AND MADISON WELLS-JAMES ’23

FEATURES ONLINE

22 The Dreams of Fatema

Driven from Afghanistan by extremism, a journalism student lands at UMD and prepares to reclaim her lost homeland.

BY CHRIS CARROLL

BY CHRIS CARROLL

30 Structural Damage

Maryland’s vanishing tobacco barns represent the vestiges of slavery and a legacy of disease. UMD historic preservationists are racing to document them anyway.

BY SALA LEVIN ’10

BY SALA LEVIN ’10

36 Truth in Exile

Decades after more than 100,000 Japanese Americans were forced into camps during World War II, a UMD archival expert is making sure the dark history of their management is finally coming to light.

BY LIAM FARRELLA New Look for a Maryland Icon

The bronze Frederick Douglass Statue on Hornbake Plaza undergoes a high-tech conservation process. —

M-aryland Mania

Can you ID the many Ms on campus? Take our quiz! —

The “Amazing” Year

An alum wins $1 million after sprinting across eight countries in “The Amazing Race”—his third reality competition show in 18 months.

Get the latest on the UMD community by visiting TODAY.UMD.EDU.

FROM THE EDITOR

sometimes i’ll be standing in a swarm of people, like in line at the Stamp Food Court, and wonder about all the stories they could tell. What terrible obstacles have they hurdled, or what unique joys did they experience in the hours, days or years before grabbing their slice of veggie pizza and plopping down in a seat?

Few Terps, I imagine, have overcome as much as Fatema Hosseini.

Whether gliding across campus on her bike or peering at her computer screen in Knight Hall’s News Bubble, the graduate student in the Philip Merrill College of Journalism blends in anonymously, deliberately. But that is extraordinary, following a life shaped by ethnic and religious persecution, casually cruel misogyny and, most recently, a harrowing escape from her native Afghanistan during the chaos of Kabul’s fall to the Taliban.

Every day, Hosseini carries an ache for her family, who fled as refugees to Canada, and anguish for her friends and former colleagues at home whose lives remain at risk. And every day, she quietly attends classes and meetings at UMD as she adjusts to American life, whether learning to drive a car or discovering that she no longer has to fear being arrested, or worse, for doing her job.

Senior writer Chris Carroll drew on his experience as a journalist covering the war in Afghanistan to share Hosseini’s journey of grit and grief for this issue’s cover story.

You’ll find a very different perspective about belonging in this country in Liam Farrell’s feature about World War II internment camps. In it, he chronicles the efforts of a College of Information Studies researcher to digitize long-archived records detailing how people of Japanese descent detained in them were mistreated, including the moving experience of helping a camp survivor’s son understand his late father’s ordeal.

Flip through the magazine to enjoy other stories that recognize and celebrate diversity on campus and beyond, like one about a podcast from the new dean of the College of Arts and Humanities that compares covers of pop songs by artists of color, or another announcing a huge new initiative to expand access to a UMD education: a $20 million annual investment to cover tuition and fees for low-income students from Maryland. Imagine the doors that will open for so many would-be Terps.

Wishing a few fabulous doors open for you in 2023.

Publisher

BRIAN ULLMANN ’92 Vice President, Marketing and Communications Adviser

MARGARET HALL

Executive Director, Creative Strategies

Magazine Staff

LAUREN BROWN University Editor

JOHN T. CONSOLI ’86 Creative Director

VALERIE MORGAN Art Director

CHRIS CARROLL LIAM FARRELL ANNIE KRAKOWER SALA LEVIN ’10 KAREN SHIH ’09 Writers

KOLIN BEHRENS

LAUREN BIAGINI CHARLENE PROSSER CASTILLO Designers

STEPHANIE S. CORDLE Photographer

GAIL RUPERT M.L.S. ’10 Photography Archivist

HONG H. HUYNH Photography Assistant

JAGU CORNISH Production Manager

DYLAN MANFRE M.JOUR. ’23 Graduate Assistant EMAIL terpfeedback@umd.edu ONLINE terp.umd.edu NEWS umdrightnow.umd.edu FACEBOOK.COM / UnivofMaryland TWITTER.COM /UofMaryland INSTAGRAM.COM / univofmaryland YOUTUBE.COM /UMD2101

The University of Maryland, College Park is an equal opportunity institution with respect to both education and employment. University policies, programs and activities are in conformance with pertinent federal and state laws and regulations on non-discrimination regarding race, color, religion, age, national origin, political affiliation, gender, sexual orientation or disability.

Photo by John T. Consoli

A Bucketload of Terp Traditions

Your article about the M Book brought back many memories. I donated my personal copy, received in 1965, to the Archives some years ago, but I remember quite vividly the page that included the important songs that dedicated students typically committed to memory: the Alma Mater, the Victory Song, the Fight Song and the Drinking Song.

My personal mission to bring back the Drinking Song has encountered strong opposition from respected members of the university community on the grounds that it would encourage student drinking. I disagree. Rather than encourage drinking, it simply provides a wholesome activity in which the students can engage WHILE they are drinking—singing.

—ALAN KAZDOY ’69, DALLAS

—ALAN KAZDOY ’69, DALLAS

The Modern Battle for Maryland’s Oysters

I grew up on the Potomac River in Colonial Beach, Va. During the winter months in the ’60s, the town’s docks were filled with oyster boats from Tangier. The men would work

the river and sleep on the boats or at Curley’s Oyster House, which had some living quarters, and then go home on weekends. Never thought about it, but I suppose they were working the Potomac because it still had an abundance of oysters.

My family was friends with Berkley Muse, the last man killed on a boat during the oyster wars, shot by the patrols mentioned in this article. And our friends, the Curleys, had a boat built with an aircraft engine for propulsion to outrun the fuzz. Another family friend currently plants on oyster grounds his family has held leases on since the 1930s. Those were heady times.

—DOUG COOPER ’79, FREDERICKSBURG, VA.Coal Veins

Liam Farrell’s story about his family’s roots in the coal mining industry, what has transpired since and Professor Paul Shackel’s work was just wonderful. What a remarkable confluence of personal and the big picture. Thank you.

—ELLEN TERNES ’68,FAYETTEVILLE, PA.

Memories in the Pages

I had to respond to the latest issue of Terp So many articles brought back wonderful memories.

“Home on the Range” reminded me of the time a group of fraternity guys put a cow on the elevator in one of the dorms and sent her to the top floor, where she emerged and wandered through the hallways.

The new dining hall (“A New Recipe for Success”) sounds amazing, but I spent four years eating at the dining halls, and the only thing I had trouble with was the “mystery meat.”

I saw my first lacrosse game (“Talk About an Impressive Season”) at UMD, participated in the card section at football games and was privileged to be in the student section at every basketball game during Lefty’s first year. We even beat his alma mater, Duke, and he celebrated by lying on his back in the middle of the basketball court at Cole Field House and throwing what looked like a temper tantrum. We loved it.

The article about Ukraine (“Big Data ‘Early Alarm’ for Ukraine Abuses”) brought back memories of the Vietnam War, the protests and the National Guard stationed all over campus.

Enough nostalgia for the time. Looking forward to the next Terp

—BERTHA JEAN BROWN PARKER ’70, SPRINGDALE, ARK.

“A Hub for Discussion, Innovation and Discovery”

Ceremonial Groundbreaking Held for Zupnik Hall

THE TERP ENGINEERING students who will design the roads we travel, the buildings where we work and live and the technology we rely on will find inspiration and state-of-the-art tools in a new building planned on campus.

Stanley R. Zupnik Hall will feature places for students, faculty and institutional partners to

collaborate, with specialized labs for autonomous vehicles and intelligent infrastructure, as well as labs for research and instruction, and seminar and meeting spaces.

The building’s name honors the 1959 UMD alum and Majestic Builders president and CEO, who recently made a $25 million commitment to the A. James Clark School of Engineering. Major funding for Stanley R. Zupnik Hall also comes from the state of Maryland and the A. James & Alice B. Clark Foundation’s Building Together: An Investment for Maryland

“It is my hope that this new space will make it easier to exchange ideas, conduct interdisciplinary research and collaboration, and be a hub for discussion, for integration of ideas, for innovation and for discovery,” Zupnik said at a ceremonial groundbreaking in November.

Stanley R. Zupnik Hall will house elements of the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering and Department of Mechanical Engineering, the Quantum Technology Center and identity-based engineering student organizations.

“Engineering brings together great minds—people with different backgrounds and perspectives, looking at the same challenge in different ways—to collaborate on solutions that serve humanity. We are excited about the game-changing collaborations that will occur in Stanley R. Zupnik Hall,” said Clark School Dean Samuel Graham, Jr. “Mr. Zupnik’s gift will help grow our engineering ecosystem and offer our students, faculty, staff and external partners access to unique facilities that will enable their innovations and impact on society.”

UMD Makes $20M Investment in Need-Based Financial Aid

STARTING THIS SEMESTER , the university is setting aside an additional $20 million annually for scholarships for low-income students from Maryland in an ambitious effort to increase affordability and access.

The new Terrapin Commitment reduces the gap between a student’s total financial aid package and the cost of an education. The program ensures that tuition and fees are fully covered for Pell Grant-eligible, in-state students who are enrolled fulltime and have unmet financial need.

“Our investments in need-based financial aid better position us to serve the people of our state—opening the door for more Marylanders to attend a world-class flagship institution,” says Senior Vice President and Provost Jennifer King Rice.

All students who submit the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) and meet the eligibility requirements are automatically considered for the Terrapin Commitment. If their funding sources—including scholarships, grants and the expected family contribution—fall below UMD tuition and fees, the Terrapin Commitment pays the difference.

“The Terrapin Commitment will help us continue to recruit and provide new pathways for the best and brightest students in the state, improve graduation rates and reduce student debt,” says Associate Vice President of Enrollment Management Barbara Gill.

A Flying Start for Greater College Park

Aviation Landing to Rise Across From Metro Station

PLANS TO REVIVE the area around the historic College Park Airport are about to take off.

The Terrapin Development Company (TDC), the university’s economic development arm, has partnered with the city, Prince George’s County and private companies with plans for Aviation Landing, envisioned as a 1.3 million-square-foot complex of retail, research and office spaces and 900-plus units of housing.

Located across from the College Park Metro Station and the coming light-rail Purple Line, the neighborhood will emphasize walkability, accessibility to recreational sites, and physical and research connections to the world’s oldest continuously operating airport.

Its storied past including as former base of the Wright brothers has intrigued UMD President Darryll J. Pines, an aerospace engineer, since his recruitment visit 30 years ago.

“I have often wanted this area to fully reflect the potential that brought me to College Park, and Aviation Landing helps fulfill that original vision,” he said at a November announcement event.

The project will mark another step in strengthening the university’s Discovery District, part of its $2 billion Greater College Park revitalization initiative. The county and another partner, 4 Castles, which owns two fire safety companies in the area, will donate land for Aviation Landing, while a third Mosaic Development Partners—is already working with TDC on redeveloping UMD’s nearby Old Leonardtown community.

When completed, the county expects Aviation Landing to create 2,700 full-time, permanent jobs and generate $370 million in annual economic output. Groundbreaking is expected by 2025.—LF

UMD Esports Comes Online

RecWell Program Puts Teams Into Elite Competition

THEY DON’T NEED HELMETS or shoulder pads, but the competition has been just as fierce this year for the newest teams wearing Terp colors.

An official esports program has booted up at UMD, with five teams competing in the National Association of Collegiate Esports League under the auspices of University Recreation and Wellness.

UMD already had a robust and successful esports scene through the 1,800 members of the student-born and student-run Gaming Club, but RecWell is now providing official gear, coaching, facilities and even travel funds for the 30 players facing off against other schools for pride and prizes in conference and tournament play. The teams are competing in Fortnite, League of Legends, Rocket League, Valorant and Overwatch, five wildly popular games played by millions worldwide and whose events regularly fill stadiums.

Sergio Brack, the first director of esports at UMD, was named one of EdTech’s 30 Higher Education IT Influencers in 2022. He previously held similar roles at the University of Mississippi and Ottawa University in Kansas. Although esports scholarships are still a work in progress, the program has secured practice space in Ritchie Coliseum and a competition area in Knight Hall where students can spar on the livestreaming service Twitch until an area is refurbished in the former Diner.

Brack says he wants to continue fomenting a sense of community, but it’s also no secret what the teams need to accomplish: “Your esports program is only as good as how much you’ve won.”

Freshman Joshua Klubes, on the Fortnite team, says esports played a role in his college decision process; he was impressed by how Terp teams had performed in past tournaments.

“It’s like having a friend group you can play with all the time, who are at your skill level and can make you better,” he says of esports. “There’s like an adrenaline rush. It’s very similar to hitting a three in basketball.”—LF

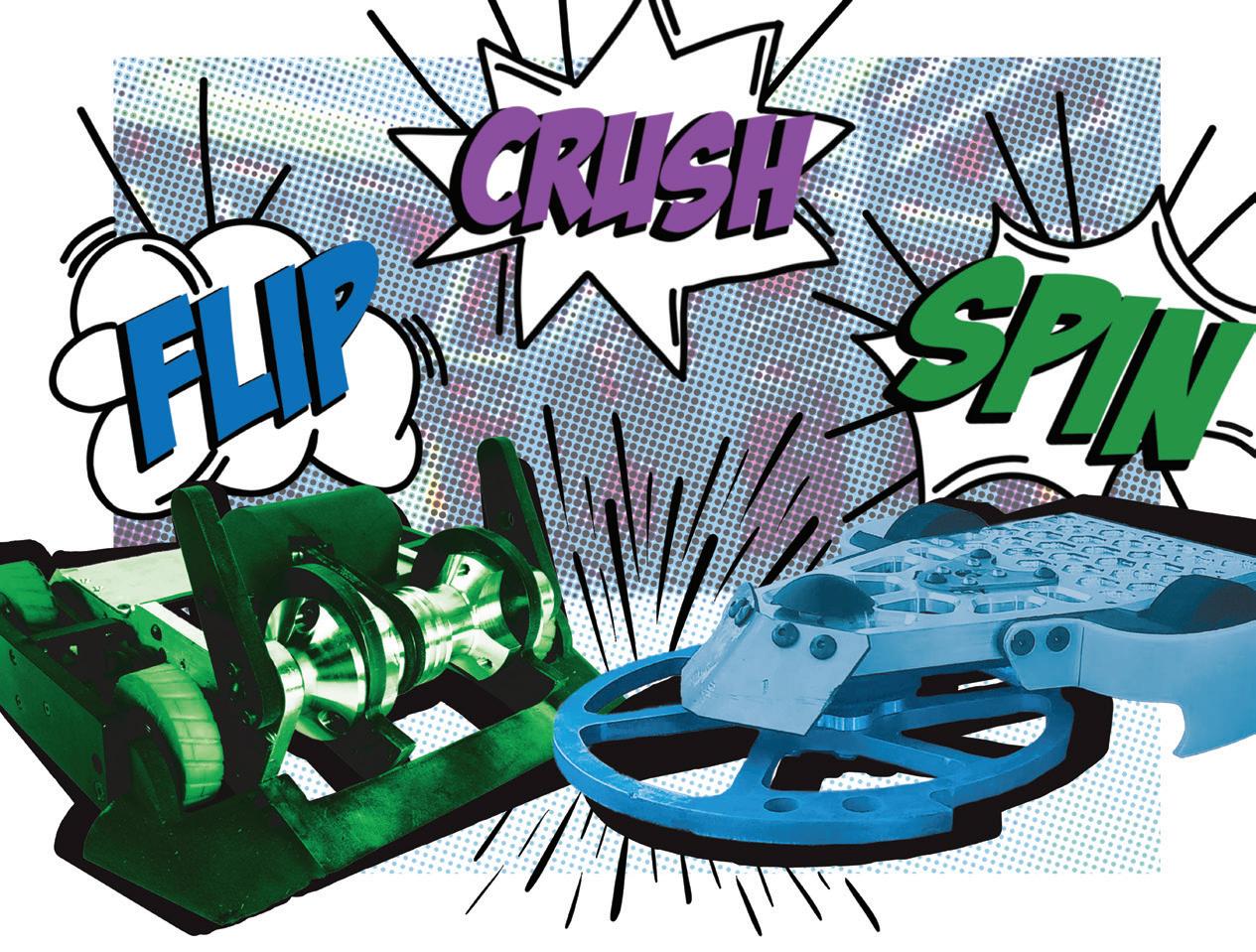

Gearing Up for Battle

Sparks—and Creativity—Fly When Combat Robotics Club Enters Arena

In this corner, making its return to the ring, 30 pounds of speedy, spinning steel and wheels known as Warlock. And in the other, the rookie, a silver, boxy, whirling disk of doom: Jade.

The match begins, and the competitors frantically dodge and circle each other, looking for an opening to deal a body blow. The tension is short-lived, but ends satisfyingly: Just 12 seconds in, Warlock powers into Jade, blasting the metallic menace into the air with a burst of sparks.

For more on how the esports community took off at UMD, revisit the Fall 2021 Terp feature “Pressing Play” at terp.umd.edu/ pressing-play

This intercollegiate conflict shown on YouTube doesn’t quite have the Vegas-y lighting and music (or ratings) of the Discovery TV show “BattleBots,” but it’s still packed with drama and robot wrecks as victory goes to the University of Maryland. Members of the Leatherbacks, the Terps’ student combat robotics club, design, build and control the mini mechanical warriors, with Warlock’s epic takedown of its Northwestern University foe in a Connecticut tournament last spring just one example of the raucous fun.

“It was a really spectacular hit,” says

Leatherbacks President Eashan Siddalingaiah ’25, savoring the shocking end to the match. He, like other members, participated on a high school’s robotics competition team, but those bots had much more placid objectives, like maneuvering around obstacles. “I always thought that the fighting would be a very interesting next step.”

Founded in 2018, the club meets twice a week to discuss design concepts and build its 1-, 3-, 12- and 30-pound competitors. Students need to tap into mechanical and electrical engineering principles to adhere to those weight limits, says Johan Larsson, associate professor of mechanical engineering and the Leatherbacks’ faculty adviser. Through a

collaboration with Terrapin Works, a campus hub of manufacturing resources, the 40 members can beef up their battling bots using 3D printers, water jet cutters and computer numerical control (CNC) mills and lathes.

While the robots end up looking more like intimidating Roombas than the laser-eyed androids you might be imagining, they can do some serious damage. They overpower opponents through either tap-outs, when enough destruction is done that a team cries uncle, or knockouts, when all the smashing and crashing render a bot motionless for 10 seconds.

The 1-pound creations fight in a campus showcase each semester, including

a Maryland Day double-elimination tournament. Terps take their bigger bots on the road every few months to compete in Connecticut’s Norwalk Havoc Robot League, with events featuring over 100 robots from other colleges and even builders from the real “BattleBots” show.

“It’s a great way to learn for us as new builders, but also to really test our skills against the experienced veterans,” says Alex Wang ’25, the club’s chief engineer.

The Leatherbacks hope Warlock and its titanium teammates can build on past success as they continue growing the club, developing more students’ engineering skills—and wreaking havoc in the ring.—ak

ON THE MALL

The Secrets to Social Success

Students Learn to Game Algorithms and Grow Audiences in Popular Class

If You had to tally 10,000 “likes” on a social media post, what would you do? Catch your cat in a compromising position for TikTok? Take your 5-year-old’s latest tall tale to Twitter? Share your swoon-worthy sunset on Instagram?

As clever as your content might be, just throwing up a post isn’t going to get the internet buzzing, says information studies Professor Jen Golbeck, an expert on social networks and internet privacy and security. That’s one of the first lessons in her

cheekily titled class, “Becoming a Social Media Influencer,” where she assigns the 10K challenge.

“The name is a bit of a joke—it’s really social media management. It’s a job there’s high demand and minimal training for,” she says. “Students have grown up using these apps and they’re savvy, but I’m teaching them how to be professional.”

Some Terps hope to be influencers in fields as varied as stocks or style; others seek to promote their businesses or professional expertise; and still others hope to grow an audience for their creative endeavors, from painting to filmmaking.

Her students don’t have to look far for an example of a thriving influencer. Golbeck’s @TheGoldenRatio4 accounts, chronicling the antics of her six (!) rescue golden retrievers, have more than 100,000 followers on Instagram and Twitter and 400,000-plus on Snapchat; 209,000 people follow her professional TikTok account, where she dispenses quick-hit social media and internet privacy tips and analysis.

She shows students how it’s easiest to trend on TikTok, where they—or political organizations, companies or

mommy bloggers—can easily manipulate algorithms. “Use trending music, caption, tag, post in the right place” at least three times a day for the first few weeks, she says. For a visuals-first platform like Instagram, don’t just snap a selfie on the beach; wear branded products and tag the companies, shamelessly include a cute dog, add popular hashtags and learn about photo composition and editing to capture engaging angles and eye-catching colors.

Few students rise to Golbeck’s challenge. But two-thirds rack up more than 1,000 “likes”—impressive, considering most students create accounts for the class. Ones that manage to go viral range from an awkward middle school photo on Reddit to spooky facts and corny jokes about cemeteries on TikTok. (The @GhostlyArchive account by Rosie Grant MLIS ’22, shown at right, has earned so much traction that she gets paid for posts, as well as freebies like Airbnb stays and alcohol.)

“You think that cute girl is just posting pictures and making a million dollars a year,” Golbeck says. “She makes it look effortless, but she’s doing a ton of work—and she’s not making a million dollars.”—ks

“A Mission of Welcome”

Nun Nutritionist Has Served UMD Students for 30 Years

FOR NEW TERPS dealing with allergies, health issues or religious requirements, trading the family kitchen for dining halls that serve thousands can be scary. So it’s no surprise that students and parents sometimes wind up taking out their frustration on UMD Dining Services’ quality coordinator and nutritionist.

But that’s only until she introduces herself. “I say, ‘Hi, I’m Sister Maureen Schrimpe.’ And then their tone changes!” she says with a laugh.

Schrimpe’s order is the Immaculate Heart of Mary, and many of its sisters practice their vocation in education—she started out as a physical education teacher. After transitioning to nutrition and working at a small religious college, she sought to make a bigger impact and came to UMD. Her role has evolved over the last three decades, and these days, her main job is ensuring that the growing number of residents with food allergies—more than 600 notified her in Fall 2022—can eat safely on campus. She also oversees student workers who create comprehensive ingredient and allergen lists, posted alongside nutrition information, on the Dining Services website.

Schrimpe takes students through dining halls to teach them about labels on each dish that identify common allergens, as well as whether the dish is vegetarian, vegan and/or halal, and suggests ingredient substitutions. For students with a complex combination of allergies, she works with Dining Services chefs to create tailored meals.

“We have a mission of welcome here, and we want to make sure we can take care of everyone,” she says.

Schrimpe’s identity can cause some confusion. Some people don’t know what to call her; just “Sister” is fine, she says, because she’s the only nun on campus. Other students have asked her if she’ll take their confession

(absolutely not—she’s not a priest) and staff members ask her and her sisters to pray for no rain on Maryland Day (she’ll do it, but no guarantees).

Though she’s taken a vow of poverty and has never seen her own paychecks, which go straight to her convent, Schrimpe does enjoy some job perks: attending basketball games, thanks to the free tickets her department receives, and trying companies’ new products when she

leads National Nutrition Month events on campus. She’s also created custom sandwiches for two of UMD’s Nobel Prize winners.

“I love my job,” says Schrimpe, who received a 2022 University System of Maryland Board of Regents Staff Award for outstanding service. “We have the best people and such a strong team. I’m so fortunate to be here.”—KS

“Food” for Thought

Performance Piece Asks Tough Questions Via Unexpected Messenger: Puppets

In 2011, nehPrii aMenii was working toward a graduate degree in theater production at Sarah Lawrence College and resolutely avoiding the distressing news of the pending execution of Troy Davis, a Black man convicted of murder in Georgia who’d garnered the support of Amnesty International, the NAACP, Pope Benedict XVI and former President Jimmy Carter.

But one afternoon, running to catch the subway in the heart of Harlem, she happened upon a protest on Davis’ behalf. “I had to go through the process of making myself un-ignorant to what was really going on” in Georgia, she says.

That process led to “Food for the Gods,” a 2012 multimedia performance piece that incorporates puppetry and sends the audience on a journey from a funeral reception to an ethereal bamboo forest to a dinner party in the afterlife attended by Emmett Till, Amadou Diallo and others. “Food for the Gods” will be presented at The Clarice Smith Performing Arts Center next winter as part of its expanded Artists in Residence program; Amenii has already begun working with UMD faculty and staff to bring the project to life.

“Unfortunately, the subject matter is relevant all the time,” says Jane Hirshberg, artistic planning program director at The Clarice. The ambitious, sculptural set design and imaginative characters like Madam Coal Belly—crafted from an antique stove and kitchen utensils—made the piece a natural fit for the program, which now offers artists two-year terms to research and produce their work.

At the beginning of “Food for the Gods,” each audience member receives a program in the form of a funeral notice, listing each real-life

Black man who will appear as a silent puppet at the dinner party. Other characters include a maternal figure, whose rage is one of the central themes of the show, and a girl meant to be a stand-in for the playwright herself and her initial instinct toward indifference as a means of self-preservation.

But it’s another character who’s central to Amenii: the real audience. The hope is for viewers to “stay actively engaged, rather than to passively disengage,” she says. “People do not care as much about issues as they do about people once (they) become real and relatable. I do believe that this is where the power of art and storytelling can play a key role in human connectivity.”—sL

Showing Support on the Court

Men’s Basketball Player From Ukraine Grapples

With War From Afar

Before he turned 16, Pavlo Dziuba was already representing his native Ukraine on the basketball court, driving to the hoop, nailing threes and laying down dunks. Last February, he saw photos and news coverage of the court in Kyiv, where he learned the game he loves, burning to the ground.

Then a new transfer, Dziuba absorbed the horror of Russia’s invasion last year from UMD’s campus, and he continues to grapple with anxious and uncertain feelings as the war rages on. As he balances school and basketball with that added stress, he’s raised awareness and showed support for Ukraine during games, even from halfway across the globe.

“The first day, I was crying—I didn’t know what to do,” he recalls. “Sometimes rockets were coming half a mile away from my mother and father.”

The 6-foot-8 junior lived in Kyiv until he was 14,

then briefly moved to Spain to play for FC Barcelona’s under-18 team. He also impressed as a center on the under-16 Ukrainian national team, averaging 13.8 points and 9.3 rebounds in the 2019 FIBA Division B European Championship. That attracted the attention of universities in the U.S., with Dziuba deemed a four-star recruit.

Though he barely spoke English (watching Netflix with subtitles and lots of practice helped him learn quickly), he moved to America to play at Arizona State. After that 2020-21 season, he entered the transfer portal, persuaded in part by a fellow Ukrainian and former UMD basketball star, Alex Len of the Sacramento Kings, to become a Terp.

“I like the way we practice and the way we compete,” Dziuba says. “It’s different, the Pac-12 and Big Ten.”

Midway through his sophomore season, he began hearing rumblings about Russia invading his home country. When it happened on Feb. 24, he frantically tried to reach loved ones, asking friends about footage he’d seen of tanks emerging and rockets blasting, and urging his family to leave Kyiv.

Mere hours later, Maryland had a game against Indiana. Before taking the court, Dziuba wrote two messages in marker along the outer soles of his bright red sneakers: “PRAY FOR UKRAINE” on one, and “NO WAR, PEACE” on the other. He continued to display them in subsequent games, and in UMD’s next home contest against Ohio State, he entered the Xfinity Center with a Ukrainian flag draped around his shoulders, to cheers from the crowd.

“I just wanted to let people know that it’s really important,” he says. “We need support. Ukraine needs support.”

Dziuba competed for his home country during last summer’s FIBA U20 European Championship in Montenegro, where he was able to reunite—for just one emotional day—with his mother. She’s since returned to Ukraine with his father, who stayed to help the cause. His brother is safe elsewhere in Europe.

Back on campus, Dziuba tries to talk with them on the phone every day. Even amid all that, he’s “locked in” for this season, he says.

“Pavlo has done as best as anyone could with the situation back in his home country. Every day since last February, he’s had to deal with something that most of us—especially college-aged students—could never fathom,” says head coach Kevin Willard. “You can tell it takes a toll on him from time to time, and as coaches and teammates, we do our best to support him however we can.” ak

Stadium Renamed in Partnership With SECU

MARYLAND FOOTBALL’S rousing victory over Michigan State wasn’t the only news on the playing field—or above or around it—on Oct. 1.

The SECU Stadium name debuted during the Terps’ Big Ten home opener, highlighting a multimillion-dollar 10-year partnership with the Linthicum, Md.-based credit union.

As part of the deal—which includes a gift to support programs and facilities—SECU becomes the official banking partner of the Terps. It will co-present financial wellness workshops for faculty and staff and support the creation of a financial literacy course for students. Maryland Athletics is also amplifying SECU’s Kindness Campaign, designed to inspire acts of service.

“From the very beginning, we aligned with SECU on goals and objectives, and more importantly, our values,” says Damon Evans, Barry P. Gossett Director of Athletics. “It is our intent to use this partnership to do good for our student-athletes, our university and our communities.”—AK

Cover Stories

ARHU Dean’s Podcast Debates Musical Remakes

Which Version Was better: the original “Nothing Compares 2 U” by Prince, or the cover by Sinéad O’Connor, who turned his funky number into a haunting breakup lament? How about “I Will Always Love You”? Was it more successful as Dolly Parton’s plaintive tune or as Whitney Houston’s power ballad?

For pop music diehards, bickering over the merits of cover songs and their original versions is as much fun as debating whether the art on the “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band” album is meant to tell listeners that Paul is dead. Stephanie Shonekan, an ethnomusicologist and new dean of the College of Arts and Humanities, has turned these amiable arguments into fodder for her podcast, “Cover Story.”

Shonekan’s podcasting career began in 2015, when she was chair of Black studies at the University of Missouri-Columbia. It was a tense time on campus, as students protested racism at the university, ultimately leading to the resignations of the chancellor and the system president. She decided to launch a show called “#Black,” where members of the campus community could come together weekly to talk about the struggles Black people faced at the university and around the country.

In 2020, Shonekan returned to Mizzou after a few years at the University of Massachusetts. KBIA, the local NPR affiliate that had produced “#Black,” asked her to

come back. “I definitely wanted to continue podcasting, but I wanted something a little more joyful, a little bit more uplifting, a little bit more reflective of all the ways Black people live, not just at the brunt of white supremacy,” she says.

So she turned to her work in ethnomusicology. The daughter of a Trinidadian mother and a Nigerian father, Shonekan had grown up with the sounds of calypso music and West African highlife, full of jazzy horns and guitar plucking. She learned that she could tell “who people are by the music that they create, the music that they disseminate, the

music that they consume, the stories that are told in that music,” she says.

In each episode, Shonekan and a guest—music fans from different walks of life—discuss two versions of a song, analyzing their differences and merits. In all cases, either the song’s initial artist or the cover artist (or both) are people of color.

In the show’s first season, which debuted last spring, Shonekan and her guests mulled over “Yesterday,” “Piece of My Heart” and “Before I Let Go.” They take up songs like “Respect” and “Ghost of Tom Joad” in the second season that began in October.

Some “Cover Story” episodes delve into the personal memories associated with specific songs. In season two, Shonekan invited her husband as a guest to talk about “their” song, “I Believe in You and Me,” originally recorded by the Four Tops and covered by Whitney Houston. “It was great to have a conversation around love and life and how it started and how it’s going, and how that song remains true to our relationship.”

But some marital disputes can’t be fixed with a song. Shonekan insists that the Houston version is better, but her husband remains solidly Team Four Tops.—sL

Planetary Protectors

Terps Helped Propel NASA Mission to Redirect an Asteroid

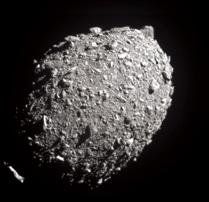

AT FIRST GLANCE, a mission to slow down a tiny moon millions of miles away seems an odd strategy to defend our planet. But developing our ability to knock around large space rocks could one day prove invaluable if we ever discover one is bound for a collision with Earth.

In September, NASA’s DART (Double Asteroid Redirection Test) mission successfully launched the equivalent of a 1,300-pound bullet at 14,000 mph straight into the asteroid moon, Dimorphos, raising a dust cloud visible from Earth.

The test’s objective was to add at least 10 minutes to the moon’s 11-hour 55-minutes orbit around a larger asteroid, Didymos. Measurements a few weeks later showed it had increased a whopping 32 minutes.

“We smacked Dimorphos really good,” says Derek Richardson, an expert in the composition of “rubble pile” asteroids like the target, and dynamics lead for the NASA mission. “I think DART has unequivocally demonstrated we could” deflect a dangerous asteroid hurtling toward Earth.

The University of Maryland was at the center of the mission, with numerous other astronomy and aerospace engineering researchers playing important roles as well. DART also solidifies the Department of Astronomy’s reputation for leadership in studying asteroids and comets. One DART team member, Professor Jessica Sunshine, directs UMD’s Small Bodies Group, formerly headed by the late Michael A’Hearn, who led the revolutionary Deep Impact mission that smashed a spacecraft into a comet to examine what was inside.

Says Richardson, “We’re happy to be carrying on the tradition now.”—CC

DART zeroes in on Dimorphos, seen 2.5 minutes before impact (from top) beyond the larger Didymos, then 11 seconds and finally with two seconds to go.

Backyard Climate Guard

Extension Experts: Climate-Resilient Gardening’s Just a Few Steps Away

YOU CAN’T ESCAPE news reports of 1,000-year floods and raging wildfires, but you don’t have to turn on your TV to see evidence of climate change. It’s growing right outside our doors, from spring plants blooming ever earlier to the warm weather-loving invasive stink bugs staking ever-larger territory.

You can take small steps to mitigate and adapt to these changes, says Christa Carignan, coordinator of digital horticulture education at the University of Maryland Extension’s Home and Garden Information Center. Its new climate-resilient gardening resource, now online, includes these tips for your own backyard.—KS

2 LOSE YOUR GRASSY LAWN (OR AT LEAST SOME OF IT) By replacing a portion of your yard with a native plant garden, you can mow less; support bees, butterflies and birds; and cut carbon emissions by laying off gas-guzzling lawn equipment and nitrogen fertilizer.

1 PLANT A SHADE TREE Cool down your home—and lower your energy bills—by adding a tree to the west side, blocking the hottest afternoon summer sun. Trees also serve as carbon sinks, absorb air pollutants and reduce stormwater runoff. The Marylanders Plant Trees site offers a $25 state rebate if you plant a native tree; cities and counties may have additional incentives.

3 GROW YOUR OWN FOOD Eating locally can reduce your carbon footprint—and nothing’s more local than your backyard. Start with just a tomato or herbs in a pot and expand as you learn. Or plant a blueberry or raspberry bush or a fig tree. Eating a more plant-based diet is also kind to the environment.

For more tips, resources and testimonials, visit go.umd.edu/climateresilientgardening.

4 CHOOSE TO COMPOST While organic matter dumped in a landfill releases greenhouse gases, composting allows oxygen to break down veggie and fruit scraps, coffee grounds and tea bags, as well as leaves and grass clippings. Extension Master Gardeners offer trainings on how to set up home compost systems, and some counties even offer food scrap pickup.

Roots of Injustice Research Finds More Vulnerable Tree Canopy in Redlined Baltimore

MORE THAN EIGHT decades after U.S. government maps formalized discriminatory real estate practices, new University of Maryland research is showing how one legacy of redlined neighborhoods is still blooming in contemporary Baltimore’s environment.

The study, led by entomology Assistant Professor Karin Burghardt and published in Ecology, analyzed streetside trees in 36 Baltimore neighborhoods and compared their quality to how those areas were once rated by the Home Owners’ Loan Corp. (HOLC). That New Deal-era program, which labeled areas as green, blue, yellow or red (for “hazardous”), was designed to boost the real estate industry by identifying prime spots for investment. But it also cemented

urban decay and racial wealth disparities by denying many minority residents the financing needed to buy their own homes.

And more than 50 years after the 1968 Fair Housing Act banned redlining, Baltimore neighborhoods once rated green by HOLC are still nine times more likely to have larger and older trees than redlined places, meaning they are better able to provide shade to counter heat waves, absorb stormwater and offer havens for species like birds that mitigate pests, Burghardt says.

“It is reflective of how society viewed these neighborhoods and how they invested in them,” she says.

In addition, the trees in redlined areas were not only younger, but were more likely to be from a single species, red maple. That lack of diversity could one day make those neighborhoods’ greenery vulnerable to environmental problems like plant disease or invasive insects.

“When we are doing these plantings, we need to be aware of the potential ecological legacies we are creating,” Burghardt says. “If you are really overinvested in one species, then these areas that we reforested all at once are going to be hit worse.”—LF

Electromagnetic Control Could Pull Surgery Into the Future

THE RISE OF minimally invasive robotic surgery means smaller scars and fewer chances of infection for patients, and greater dexterity and precision for doctors, but one problem sticks out.

Or rather, it sticks in: that big robot arm, with joints and links that don’t fit neatly inside the body, particularly for small or delicate surgeries like eye operations or pediatric hernia repair.

A UMD mechanical engineering researcher is “disarming” surgery robots in pioneering work to move tools inside the body with only an electromagnetic field. Assistant Professor Yancy Mercado-Diaz and collaborators have used magnetism to steer a tiny needle to penetrate and suture in various test materials, including animal tissue—a complex problem of robotic control and vision he likens to “finding a needle in a bloody haystack.”

Such tech niques might not even require surgeons to cut into a patient at all; the tools are injectable. “It’s truly ultra-minimally invasive, with less trauma and faster recovery,” he says.

The next steps include refining innovative means to push small, light implements through tissue with more force— one invention works like a tiny hammer—and exploiting variations in magnetic field shapes generated by their equipment to simultaneously control multiple, independent surgical tools.—CC

Moving Beyond “Getting Tough”

Amid Spiraling Violence, Criminologist Studies New Approaches to Gun Crime

WHILE STUDYING street gangs as part of his Ph.D. in Chicago in the late ’90s, an interview with a non-gang teen helped change Rod Brunson’s thinking about what his research could accomplish.

“She’d figured out how to navigate going to school or the corner store without being victimized,” says Brunson, a professor of criminology and criminal justice. “But then this young person said very somberly, ‘Can you do something about the police?’”

Brunson today focuses on answering questions—like how to improve policing—that interest not just criminologists, but people in the often-underserved communities he studies. His latest research tackles the rising toll of gun violence, which UMD is broadly addressing through the 120 Initiative, named for the approximate number of people killed each day in the U.S. by firearms. He spoke to Terp about the impact of abundant guns, the dangerous ways some people learn to use them and a public health-based approach to stopping an ongoing national tragedy.—CC

What’s the common thread between mass shootings we see on the news and the daily killings we usually don’t?

They’re different issues in many ways, but tied together by the attraction guns have for young males. We have many more guns per citizen than any country you’d normally compare us to.

Will simply reducing the number of guns help solve the violence problems?

Discussions of laws keeping guns out of the hands of people who should not have them are well-intended, but the sheer number of guns means people are going to obtain guns for the foreseeable future. And just telling people who are high-risk or prohibited from carrying guns to stop doing so is ineffective.

In areas plagued by violence, what prevents people from just walking away from guns? Not all, but many people feel, whether it’s reasonable or exaggerated, everyone around them is carrying—including people out to do them harm. When my collaborator, (UMD Assistant Professor) Brooklynn Hitchens, and I analyzed data from people in New York, where there are high penalties for illegally carrying a gun, we were struck by the quip, “I’d rather be judged by 12 than carried by six.”

So we’re awash in guns, and laws are hard to pass or maybe won’t work. Do we throw up our hands?

No, we need to hold people accountable, but

maybe we also should pivot and learn from the failures of the past. I think one thing most people can agree on is that ‘get tough on (insert whatever issue here)’ has not worked out well, whether it’s drugs or other criminal activity. It doesn’t solve problems, but it does have unintended consequences like mass incarceration or further disenfranchisement. Instead of coming at it simply from the standpoint of law enforcement, we examined a public health approach in this new study and found it could help.

What would that entail?

A surprisingly high number of people we surveyed in at-risk neighborhoods got instruction in handling guns from movies or video games. Many people do not store guns safely—unlocked under the bed where children can find it, for instance, or outdoors.

What we’re suggesting is that grounding people in gun safety could solve some of these issues. It is a little bit similar to immunization: Immunize everyone you know with safety practices, so it will hopefully protect those people who are most in need, or at highest risk.

reach. People invest their money on this technology hoping for a quick profit. Self-driving cars, however, are very far into the future, because although they have good enough perception, they lack common-sense reasoning. We don’t know yet how to give machines common sense.

PROFESSOR AND CHAIR IN THE

its aftermath, which threatens our democracy in fundamental ways.

CARO “SPIKE” WILLIAMS-PIERCE ASSISTANT PROFESSOR OF INFORMATION STUDIES, COLLEGE OF INFORMATION

CARO “SPIKE” WILLIAMS-PIERCE ASSISTANT PROFESSOR OF INFORMATION STUDIES, COLLEGE OF INFORMATION

STUDIES

That so-called “soft” degrees (like the humanities, psychology, etc.) aren’t useful. Any student who thinks deeply about people and society could have told Apple that its AirTag design was ripe for horrific misuse, and suggested design alternatives before release. These degrees are very useful—it’s just that big companies haven’t been leveraging them properly.

of the ‘white man’s burdens,’ and it is by no means the least of those burdens.”

This was the opening statement of Dr. L.C. Allen’s general sessions address at the 1914 American Public Health Association meeting. His rhetoric perpetuated a fallacious dogma of anti-Black racism, white supremacy and medical racism that some still believe today.

guarding against making things worse by

threat to the United States. Despite appearances, deadly terrorist attacks in most parts of the world and for most time periods are extremely rare. The trick is to devise policies that protect from the deadliest possibilities while overreacting.

Share your answer and see more faculty responses at

.

What’s been the most significant lie or untruth told to the public?

Fatema Hosseini is shown in front of a projected image of Afghans lining up to board a military jet to evacuate the capital, Kabul, as the country fell to the Taliban in August 2021. Hosseini escaped in similar fashion from the same airport.

THE DREAMS OF FATEMA

DRIVEN FROM AFGHANISTAN BY EXTREMISM, A JOURNALISM STUDENT LANDS AT UMD AND PREPARES TO RECLAIM HER LOST HOMELAND.

BY CHRIS CARROLL PORTRAIT BY JOHN T. CONSOLI

BY CHRIS CARROLL PORTRAIT BY JOHN T. CONSOLI

atema hosseini made her way to work in Kabul on Aug. 15, 2021, an unremarkable figure at first, but transformed hour by hour into a spectacle, and finally, a target.

Afghanistan’s president had fled the country and the U.S. Embassy was being evacuated, according to breaking news reports, and in a city where a full hijab was suddenly advisable, the then-27-year-old journalist’s loose headscarf now looked too perfunctory, her fashionable skirt ending well above the knee now shameful, despite the jeans worn underneath.

It was widely assumed that the tottering central government would collapse after U.S. forces’ withdrawal, scheduled for completion 20 years to the day after the terrorist attacks that had brought them here. The abruptness of it, while troops were still filtering out, had been a frightening jolt for everyone, even at Kabul Now, the investigative Englishlanguage news agency where Hosseini covered corruption, women’s rights and other controversial topics. Outside, Taliban fighters roamed the capital’s streets, unopposed, for the first time since 2001.

Her anxiety mixed with defiance. Wasn’t now the time for journalists to do their jobs? Worried for her safety, her mostly male colleagues urged her to get home and lie low. While none of them was safe, her in-yourface social media approach—typified by her use of Twitter tags like #TalibanGotoHell— made the diminutive, unmarried Hosseini a tempting object for retaliation. It could come via a bullet or, what scared her more, forced marriage to some Islamist insurgent turned de facto government soldier.

With a male colleague and his wife, she fled through streets that had assumed a zombie apocalypse vibe—cars colliding, pedestrians running in terror. A tan pickup, one of thousands abandoned in the U.S.

retreat, rolled past them, loaded with Kalashnikov-wielding guerilla fighters.

The only woman outside in her neighborhood, she ignored the urge to run and instead strolled calmly home—a strange vision to men embracing the new reality. “Look at that bitch,” spat a shopkeeper who’d never before bothered her. “You’ll find out things have changed.”

At her flat, where her parents, teenage brother and adopted baby sister—recent evacuees from the Taliban’s takeover of the western Afghan city of Herat—were sheltering, her calm evaporated and she fell into her mother’s arms.

The next morning her mother forbade her to go to work. With a crushing headache, Hosseini lay for hours on the floor of the

apartment thinking of her bleak future in Afghanistan, knowing she and her family had to escape—but how?

Hosseini recounts the start of that life-threatening journey from Kabul to Ukraine to the United States in a series of interviews in Knight Hall. Now a graduate student in the Philip Merrill College of Journalism, she isn’t just willingly relating the traumatic events of her final days in Afghanistan, but reliving them through frequent nightmares. Many nights, the world is again collapsing, and she is being chased, grabbed, beaten by pitiless men who despise every facet of her identity. “Getting out of Afghanistan, part of me died there,” she says. What survived is a drive for autonomy and freedom that has shaped her life.

BORN A REFUGEE

Her story can start as far back as you please: the Sunni-Shia split in Islam 1,400 years ago; medieval migrations and clashes of cultures that created the patchwork of modern Afghanistan; two centuries of warfare and geopolitical wrangling by Britain, Russia and the United States; the rising threats of terrorism and religious fundamentalism.

Hosseini’s parents, Sayed and Masuma, had at least two political strikes against them. His father had served in Afghanistan’s Soviet-backed national army battling the Taliban’s predecessors, the U.S.-sponsored mujahideen. Secondly, they were members of the oft-persecuted Hazara minority, which makes up about 20% of the population and whose partially East Asian genetic background and adherence to the Shia branch of Islam differentiate them from most Afghans.

For safety, the family had fled to neighboring Iran with their older daughter, Marzia, during the Taliban’s first rise to power in the 1990s, culminating in an earlier sack of Kabul and the group’s embrace of Osama bin Laden and al-Qaida.

Fatema was born in 1994 in eastern Iran; across the border in Afghanistan, Taliban attacks on Hazara communities increasingly looked like genocide. Thousands were slaughtered in a single episode in Mazar-i-Sharif in 1998, along with countless smaller atrocities elsewhere. In 2001, United Nations observers uncovered Hazara mass graves in Bamiyan, the province the Hosseinis had fled. (The attacks continue, as seen in a suicide bombing at a Kabul school in October that killed 53 people, mostly Hazara girls and young women.)

Iran’s introduction of a

measure that drove the cost of education out of reach for many refugees pushed the family back to Afghanistan in 2004. Thanks to the U.S.-led overthrow of the Taliban government and new international funding for girls’ education, 13-year-old Marzia and 10-year-old Fatema were free to learn in their homeland.

Masuma, who’d entered an arranged marriage with Sayed at 13 and had Marzia at 18, was determined that her own daughters would finish high school at least. When she approved a marriage proposal over her older daughter’s objections, the groom’s family (Masuma’s relatives—a common arrangement in Afghanistan) agreed to her request that the union would wait until the bride turned 18. Marzia’s real passion was English, and she soon opened a language school at home, earning a bit of money by passing along what she had learned to local children whose schools did not teach English.

Fatema, meanwhile, lived to shoot marbles with neighborhood boys. She was a talented student whose love of math and science competed with her fondness for goofing off in class, Marzia recalls.

Unfortunately for annoyed teachers who hoped to send her home for the day for coming unprepared, Fatema had likely already read the entire textbook and could answer every question with a smile, to classmates’ great amusement. “She’s always been bold and outspoken and so smart,” Marzia says.

GENDER WALLS AND DOORS

A few years after returning from Iran, Marzia Hosseini took an office job at the provincial governor’s office in Herat, supplementing her father’s income as a recently enlisted Afghan soldier. It allowed Fatema to enroll in a prestigious private high school in the city, but

meant grueling commutes from an outlying suburb, a schedule that became still harder when she began daily, two-hour classes to prepare for college entrance exams.

One morning, she was robotically trudging to the bus after only a few hours of sleep when a man rushed at her on a dark, deserted street. He seized and groped her, pulling at her clothes. Exploding with screams and flying elbows, Hosseini broke free and sprinted for a main road. Her mother heard the commotion and came running to grab the man, who claimed before fleeing that a vicious dog had chased the girl.

Shaken and in tears, Fatema declared she was done leaving the house before dawn to make the two-hour journey to school. Masuma comforted her daughter, but told her if she quit, it would simply confirm to doubters among their neighbors and extended family that girls and education don’t mix.

She endured, suffering the psychological aftermath: “You want to peel your skin off so you can wash it.” She was ready for the next attack, too. When a man roughly fondled her through the thin fabric of the seat bottom on a bus bound for school, she spun and smacked him across the face. What would be a gutsy move on the D.C. Metro could have gone very badly in provincial Afghanistan. She avoided a potentially violent response when the other passengers instead forced her off the bus, shouting, “Whore!”

Fatema was partway through high school and Marzia was just starting at the American University of Afghanistan in Kabul when the family of the would-be husband appeared in order to plan the marriage their mother had approved years earlier. Marzia again refused, sparking a tense family showdown.

It was ended by Sayed Hosseini, a low-key man of little education who had lost the family’s savings in a real estate scam upon their

“Getting out of Afghanistan, part of me died there.”

—FATEMA HOSSEINI

return from Iran, plunging the Hosseinis into near-poverty. He’d since habitually deferred to his dynamic wife as the family’s tactician, but now he spoke up, citing his mother’s unhappy arranged marriage. If Marzia wanted to opt out of the tradition, he declared, no one would force it upon her. The same, he added, held for Fatema, whose marriage to a cousin had been pending.

“I thought, ‘Oh my God, I’m free’—the door was open for the future,” says Marzia, who today works with refugees in Vancouver, British Columbia, for the Salvation Army and is engaged to be married on her own terms. “It set an example for Fatema, too. She knew she had choices, and she could say no and be taken seriously.”

Nearly 10 years after arriving in Afghanistan from Iran, Hosseini left for Chittagong, Bangladesh, where she’d received a scholarship to study computer science at Asian Women’s University. She’d withdrawn from the prestigious Kabul University, which she’d quickly soured on after being herded into an economics major, partly for gender reasons, and sharing cramped quarters with a roommate who insulted Hazara people and bullied her.

Compared to tense Kabul, where Taliban terror attacks were intensifying, Bangladesh was a warm hug. “I was there five years and never once called out” for gender, race or religion, she says.

She graduated in 2018 and started a fellowship at a climate-focused nonprofit in the capital, Dhaka, developing friends and feeling secure for the first time working in the presence of unrelated men. Then her life in Bangladesh ended.

Her mother, caring for Fatema’s ailing grandfather while pursuing her own deferred university studies in Herat, collapsed with a

leaking blood vessel in her skull. Marzia had won a college scholarship in the United States, and Fatema told her not to surrender it.

So she returned home, and after her mother’s condition stabilized, needed a job. Intrigued by the thought of exploring the confusing currents in Afghan society that had buffeted her and her family, Hosseini accepted an entrylevel position at Kabul Now in January 2019.

She interviewed people from across political and ethnic spectrums for her stories, and began working as a freelancer for USA Today, which needed local reporters to augment its coverage of the coming end of the U.S.-led Global War on Terror. Her journalism career was gaining traction as her country sank beneath the relentless Taliban advance.

FUEL FOR NIGHTMARES

Two nights after the government’s collapse, a friend called to warn Hosseini that Taliban fighters were beginning house-to-house searches for enemies. The Hosseini family made a pile of its most dangerous possessions—English proficiency certificates, military training documents, school-related papers, Fatema’s carefree photos of herself and a mixed-gender group of friends in Western-style clothes. Some they tried to obliterate by burning in their bathroom (which smelled suspicious, they realized), and Masuma Hosseini spent hours cutting the rest into tiny pieces.

One document they did save was crucial for the future. Hosseini’s diploma from Asian Women’s University was tied securely to her back beneath her clothes and a traditional long cloak as she stared at the fortified perimeter of Kabul International Airport on Aug. 19 amid a raucous crowd of people wanting out as much as she did.

Over the previous days, a group had formed to help her, starting with colleagues

“You could literally see in his eyes he was crazy, lashing people for no reason, shooting his gun in the air.”

—FATEMA HOSSEINI

Desperate would-be evacuees wait outside Kabul International Airport as the United States and allies complete their military pullout from the country. Before her escape, Hosseini endured sexual and other physical violence while trapped in a crowd outside the airport.

at USA Today. The paper’s editor-in-chief, Nicole Carroll, says U.S.-based publications had become acutely aware of the risks their local staffs and freelancers faced, and wanted to create lifelines similar to those offered to Afghan nationals who worked for the American government.

“She’s a woman, a journalist, and she’d just published a story in the U.S. media critical of the Taliban,” Carroll says.

Kim Hjelmgaard, a London-based USA Today correspondent with whom Hosseini had worked on several stories, reached out to every contact he could think of, until a U.S. Navy reserve public affairs officer said he knew a Ukrainian army psychologist who was arranging air evacuations for Ukrainians and Ukrainian Afghans. There was a seat for Hosseini on the plane—if she could make it past multiple Taliban checkpoints at the airport.

At the first one, she’d already been separated from her younger brother, Abdulfazl, who was to help her through the tumult, when a young Taliban fighter slammed the butt of his rifle into her chest and threatened to kill her. She fell, and the youth came screaming toward her—“You could literally see in his eyes he was crazy, lashing people for no reason, shooting his gun in the air,” she says—before his older partner blocked him.

At the next, a Taliban soldier answered her confusion at following orders in the Pashto language by cracking his whip at her. It inadvertently struck the woman behind her and opened her shoulder bloodily. Again,

Hosseini somehow slipped through.

She was nearly fainting under her layers in the 90-degree heat when she received a text from a Ukrainian special forces soldier who was waiting for her at a different gate. He wrote: “Sorry Fatema.” Certain the plane would leave in half an hour, she begged people to point her to the airport’s north gate, to no avail.

Fleeing back the way she came, she caught a taxi. As she approached the correct gate, she saw a vast crowd of men and women sitting together—“very religiously wrong,” she says, and a clear indicator of chaos. Taliban members fired Kalashnikovs while NATO forces shot containers of tear gas, one of which landed near her as she entered the crowd. Rapidly texting all of her contacts that she couldn’t catch her breath, she got a boost from Navy public affairs officer Alex Cornell du Houx. “Just let go of your tears, it’s OK. Just breathe,” he texted her.

Trapped in the reeling crowd, she sank down in the middle of a Pashtun family, and in front of his wife and daughter, a man inexplicably grabbed Hosseini forcefully and painfully between her legs. “His wife was watching that. He had a daughter who was watching that,” she says. “No one said anything.”

She struggled to her feet and screamed for help, even as a Taliban fighter threatened to shoot anyone who didn’t sit. Then he was next to her firing, shells falling inches from her ear.

“I don’t know if the woman by me died or not—I couldn’t look,” she says, struggling to relate the blur of horror. “Then he threw me like you throw a piece of trash, and I fainted.”

She awoke to an offer of much-needed water from a young man who called her “sister” and alerted her to her ringing mobile phone. With her brother approaching the gate, she decided to go home with him; her escape had failed. But then another message, this time from an Afghan working with Ukrainian forces, directing Hosseini to pass

through one more gate. Blocked again by a black-clad fighter, she asked in desperation: “Why do you do this? We’re both Afghans. Why do you use this much violence?”

Without a word, the Taliban guard stepped aside, and moments later, as she yelled across a razor-wire fence that she had arrived, a Ukrainian soldier stepped through the perimeter, picked her up and carried her into the airport, where the plane still waited on the tarmac.

TEMPORARY REFUGE

She fled hatred and intolerance as her parents had done before her birth. Now she vowed to bring them and her siblings out as well.

Hosseini arrived in Kyiv, where now-retired Lt. Col. Iryna Andrukh, the Army psychologist who’d arranged for her seat on the plane, took Hosseini home with her.

“When I started texting with her, she seemed so sensitive and scared—just a tiny little girl who needed help,” Andrukh says. “I’m older than her, so I started feeling like her mom, and I took her to my parents’ apartment. Every day she was crying for her family, so I had to get them too.”

Andrukh, who had gained renown as a fearless hostage negotiator in Ukraine’s conflict with Russia, soon secured a Ukrainian plane and ferried hundreds more people out of Afghanistan—including Hosseini’s family.

They all reunited nearly two weeks later in Kyiv, and then, with help from Carroll and USA Today, she flew to Washington, where she planned to continue her education, arriving on Sept. 11. Her parents and siblings, meanwhile, waited for their Canadian refugee certification to join Marzia, who had moved to Vancouver after graduating from Montclair State University in New Jersey. (Their flight was not over, however. Still living in Kyiv when Russia launched an all-out invasion in February, they fled first to Poland before finally meeting Marzia in Canada.)

Carroll opened her home in Northern

Virginia to Fatema, and helped her make connections around the Washington area, including with faculty at Merrill College, where Hosseini enrolled in January 2022.

Journalism Dean Lucy Dalglish says she’s grown used to walking past Knight Hall’s glass-walled classrooms and seeing Hosseini laser-focused on instruction, trying to absorb every bit of learning available, while she herself helps broaden the perspective of the college overall.

Hosseini’s future looks nearly limitless, Dalglish says.

“She can go back to her country and be a changemaker,” she says. “She could have a brilliant journalism career working for almost anybody. I think she has the potential to develop into a great leader.”

Hosseini relishes being just another student in the college, biking from an

off-campus apartment, pursuing a piece for the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism or racing to finish a paper in the “News Bubble” lab. She is willing to talk about her struggles to honor the sacrifices of parents who helped keep her on a path to graduate studies, as well as the chain of people stretching from Kabul to College Park who helped her at great effort, simply because they were able.

Mostly, she wants the world to keep talking not only about Afghan refugees— including families welcomed in early 2022 to campus housing at UMD—but the plight of the vulnerable, particularly women and ethnic minorities, still suffocating under extremism and intolerance.

Safe for the moment, Hosseini is determined she’ll use the skills she’s now developing to tell the truth about her ongoing homeland and the slaughter of the Hazara people. “At first I was so angry, I wanted to join the army and fight,” she says. “I don’t think that anymore, but I am not done with the Taliban.”

Thoughts of return mix with her

“At first I was so angry, I wanted to join the army and fight. I don’t think that anymore, but I am not done with the Taliban.”

—FATEMA HOSSEINI

Fatema Hosseini snaps a selfie (facing page, at left) with her mother, Masuma, now a refugee in Canada.

Nicole Carroll (left) leads Hosseini out of Dulles International Airport, where she arrived on Sept. 11, 2021.

The USA Today editor-inchief hosted Hosseini in her home and helped her connect with UMD’s Philip Merrill College of Journalism.

disturbing dreams of escape. Hosseini remembers when her dreams seemed clear, even meaningful. In the final months of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan, scattered groups of young people around Kabul talked of taking up arms to defend the city and whatever flowering of freedom they had experienced—wearing dresses, skateboarding, going to hip-hop shows—against the onrushing Taliban wave.

Hosseini was fascinated by the concept, both as a journalist and as a young Hazara woman, and she found herself one night in a dream walking into a large open space filled with ranks of muscular warrior women training, their long hair tied in loops and hung with assault rifles like deadly jewelry. She tried blending into a line of fighters, self-conscious of her lack of ability.

What should she do, she asked one of the warriors? How could she contribute?

“She looked at me, and she was, like, ‘You have a long way to go. You have to get prepared,’” Hosseini says. “Then I woke up in a sweat.”

TERP

STRUCTURAL DAMAGE

Maryland’s vanishing tobacco barns represent the vestiges of slavery and a legacy of disease. UMD historic preservationists are racing to document them anyway.

BY

BY

Winding along the wooded or wideopen roads of Southern Maryland, you might one day find a ghost. It takes some searching, but after parking on a rutted, muddy path or a patch of thin gravel, then high-stepping over knee-length grasses to some secluded spot, you may come across a dilapidated wood barn.

With its characteristic heavy timber frame and internal horizontal poles for hanging the tobacco leaves to cure, the barn recalls the Southern Maryland of centuries ago: thick forests, ships coming and going on the region’s many rivers and tributaries, and fields erupting in the wide leaves of the tobacco plant.

Tobacco barns were once ubiquitous, visible signs of the crop’s grip on the economy and day-to-day life of St. Mary’s, Charles, Calvert, Anne Arundel and Prince George’s counties, where enslaved people did the exhausting work of harvesting and drying.

But since the deadly effects of tobacco became widely known, the barns have fallen into disuse and disrepair, their unique structure rendering them good for no other money-making pursuits. The 2000 launch of the state’s Tobacco Crop Conversion Program, commonly known as the tobacco buyout, signaled Maryland’s official stance on tobacco farming: No more. Four years later, the National Trust for Historic Preservation ranked Southern Maryland’s tobacco barns among the most endangered historic places in the U.S.

According to the Maryland Inventory of Historic Properties, about 150 pre-Civil War tobacco barns remain in the state. Dennis Pogue, associate research professor of historic preservation in the School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation, estimates it’s closer to 75; buildings like these are notoriously hard to keep track of, given their tendency to collapse or their owners’ eagerness to tear them down.

Funded by a two-year grant from the Maryland Historical Trust, and with help from the five counties’ planning offices, Pogue and

former students Chris Bryan MHP ’21 and Sara Baum MHP ’20 are hoping to document every remaining pre-Civil War tobacco barn in Southern Maryland.

“It’s a huge cultural thing, and was socially, economically and culturally what really defined Southern Maryland for more than 300 years,” he says. “I don’t lament the demise of tobacco, but that doesn’t mean that these buildings aren’t still culturally important.”

Allison Luthern, the nonprofit’s architectural survey administrator, calls the barns “highly endangered resources.” “If you want to capture information about these buildings before they’re gone, survey is the way you do that.”

Pogue drives through the state, knocking on homeowners’ doors to ask if he can check out their decrepit barn out back. He asks if they know of any other tobacco barns. Usually, they don’t.

Once he’s granted access, Pogue starts taking notes and sketching. He inspects the barn’s wood poles and joints, determining from the

surface of the wood whether they were cut with a circular saw or a pit saw and whether the nails used are made by hand or machine. He measures the poles spanning the width and length of the barn, and their distance from one another. He finds the vents needed to allow the tobacco to air dry over the fall and winter.

What Pogue’s drawings can only hint at is the human history. The state’s native people grew tobacco, and taught the English colonists how to plant and harvest the crop when they arrived in the 1630s. It was a natural fit for the region’s humid climate and largely flat landscape.

By the early 18th century, tobacco was big money in the state, and after the Revolutionary War, Virginia and Maryland accounted for 80% of all tobacco exported from America.

Slavery was essential to the industry as practiced here. By 1850, nearly two-thirds of the population of Charles, Anne Arundel and Prince George’s counties were enslaved people. They did most of the labor-intensive work of planting, harvesting and drying tobacco.

The Sims-Bond tobacco barn (left and above) was built between 1835 and 1845 by John F. Sims. Located in what’s now Greenwell State Park in St. Mary’s County, the barn is the state’s only remaining one constructed from hand-hewn logs and pegs (above right). At right, a door opens to the Chelsea barn in Watkins Regional Park.

“It is true, that from the period when the tobacco plants are set in the field, there is no resting time until it is housed,” wrote Charles Ball, who’d been born on a tobacco planation in Calvert County, in his 1859 first-person account, “Fifty Years in Chains, Or The Life of an American Slave.” “After it is hung and dried, the labor of stripping and preparing it … is comparatively a work of leisure and ease.”

After the Civil War, the tobacco market crumbled, but rebounded in the early 20th century and remained strong until roughly the 1980s. The public grew to know more about the dangers of tobacco, and eventually, then-Maryland Gov. Parris Glendening launched the tobacco buyout, offering growers a dollar per pound for 10 years, provided they agreed to permanently end producing tobacco. Ultimately, 94% of the state’s tobacco growers took the deal.

For Pogue, the nitty-gritty details of how people of all social strata lived in the past are essential to understanding the full historical picture.

Another project of his focuses on preserving Virginian slave

quarters, an endeavor he first became interested in during his time working at Mount Vernon.

The students who work on tobacco barns with Pogue share his sense of urgency. “You can learn about how they utilized these barns in their daily tasks,” says Bryan. “Folks who had them, and those barns as a resource for doing that, are disappearing, so getting a good record of them leaves that (information) behind for people 20 years from now, when there aren’t more than a couple barns left.”

Pogue and Bryan have encountered their share of disappointments. Recently, the owners of a Calvert County barn razed it without notifying the county beforehand.

“If we had known, we would have gone and recorded the barn in advance,” Pogue says. “No matter what would’ve happened, at least we would have (a record), and that’s sort of the attitude we have toward this—at least we have evidence for these buildings, even if they have to go.”terp

Truth in Exile

Decades after more than 100,000 Japanese Americans were forced into camps during World War II, a UMD archival expert is making sure the dark history of their management nally comes to light.

By Liam Farrell

TOP PHOTO: UC BERKELEY, BANCROFT LIBRARY; RIGHT PHOTO COURTESY OF HARUO KAWATE

By Liam Farrell

TOP PHOTO: UC BERKELEY, BANCROFT LIBRARY; RIGHT PHOTO COURTESY OF HARUO KAWATE

AFEW YEARS after Masao Kawate died in 1997, his son Haruo was sifting through his papers and diaries in Tokyo when a curious letter caught his attention.

Kawate, a high school teacher, had known that his father, a second-generation Japanese American born to immigrants in California, had lived in the United States before being imprisoned along with more than 100,000 other Japanese immigrants and Americans in camps during World War II. But the 1958 note addressed to a San Francisco attorney raised new questions about what that experience—and his father’s life—had actually entailed.

“I am now seriously thinking of going back to the United States if possible. But being a renounced I have to get my citizenship reinstated to do it,” he wrote. “In the past I have never lled out the a davit to apply for reistating (sic) my citizenship because I thought my case was quite di cult. But having heard that many persons who were in the similar situation were successful in getting the citizenship reinstated through you, I have decided to write you.”

Kawate was ba ed: Why did his father renounce his U.S. citizenship in the rst place?

“Not even my mother knew this,” he told a documentary crew from NHK, Japan’s public media organization.

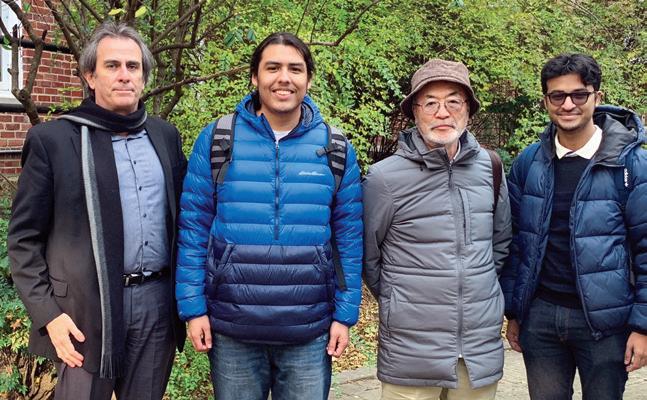

Kawate’s long search for answers eventually led him to the University of Maryland and Richard Marciano, a professor at the College of Information Studies.

It has been nearly a decade since Marciano rst found largely unknown government les on internments. Working with his Advanced Information Collaboratory

group, Marciano is building a new evidentiary infrastructure that will allow researchers, as well as survivors and descendants like Kawate, to access the hard documentation that remains—papers the government is allowing to be shared only now, more than 75 years after they were produced.

“These are really important records of daily struggles and what happened inside the camps,” Marciano says. “What’s hidden in the archives, what’s represented, the histories that are there are living histories and continue to be contested histories.”

FOR THE JAPANESE people rst herded into racetracks and livestock pavilions in early 1942, and later camps scattered across California and Idaho and as far away as Colorado and even Arkansas, the o cial story that the government was trying to protect them from potential violence by their white neighbors evaporated quickly.

If that was the case, as historian Richard Reeves noted in his 2015 book “Infamy,” why were the machine guns on the towers pointed in toward them—and not facing out?

The road to those camps was built in earnest after Japan attacked Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, but the racial animosity that laid the foundation started much earlier. Laws dating to the 18th and 19th centuries barred Japanese immigrants from becoming U.S. citizens, and new Asian arrivals were banned entirely in 1924. In 1940, all resident aliens, including nearly 92,000 Japanese, had to begin registering annually at post o ces and notify the government of changes in address.