THE DAIRY: STILL COOL AFTER 100 YEARS 6

SUPER POWER, SAFETY FOR EV BATTERIES 24

THE WILD PAIR BEHIND THE CARD GAME FLUXX 30

THE DAIRY: STILL COOL AFTER 100 YEARS 6

SUPER POWER, SAFETY FOR EV BATTERIES 24

THE WILD PAIR BEHIND THE CARD GAME FLUXX 30

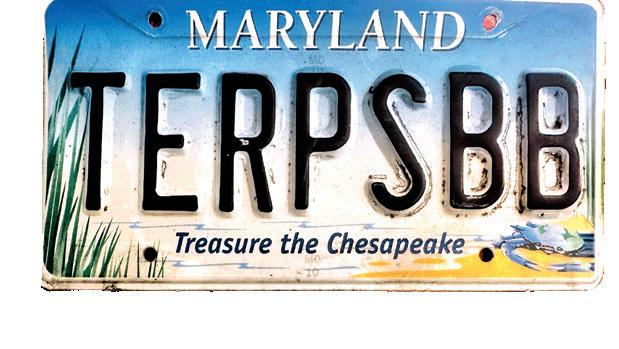

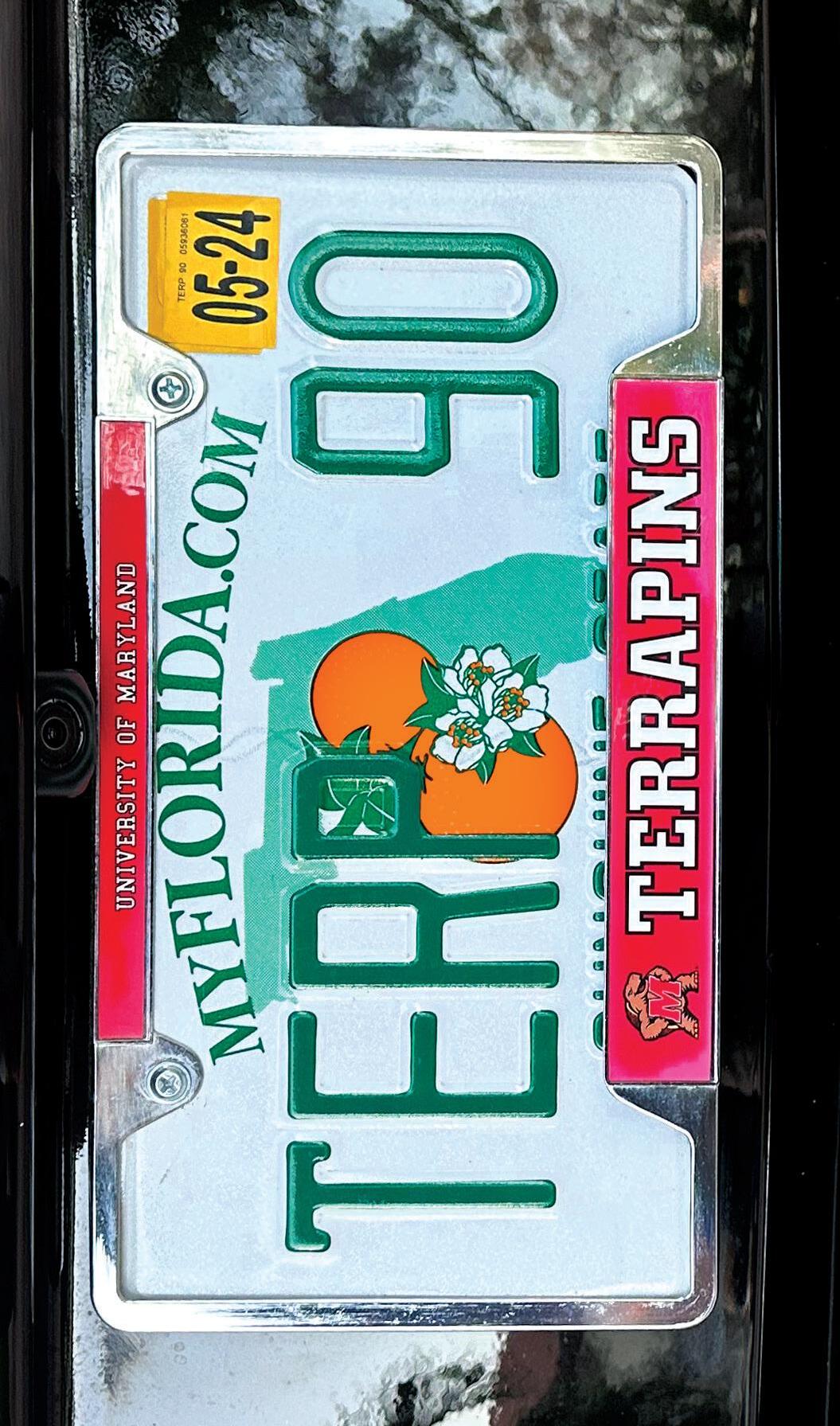

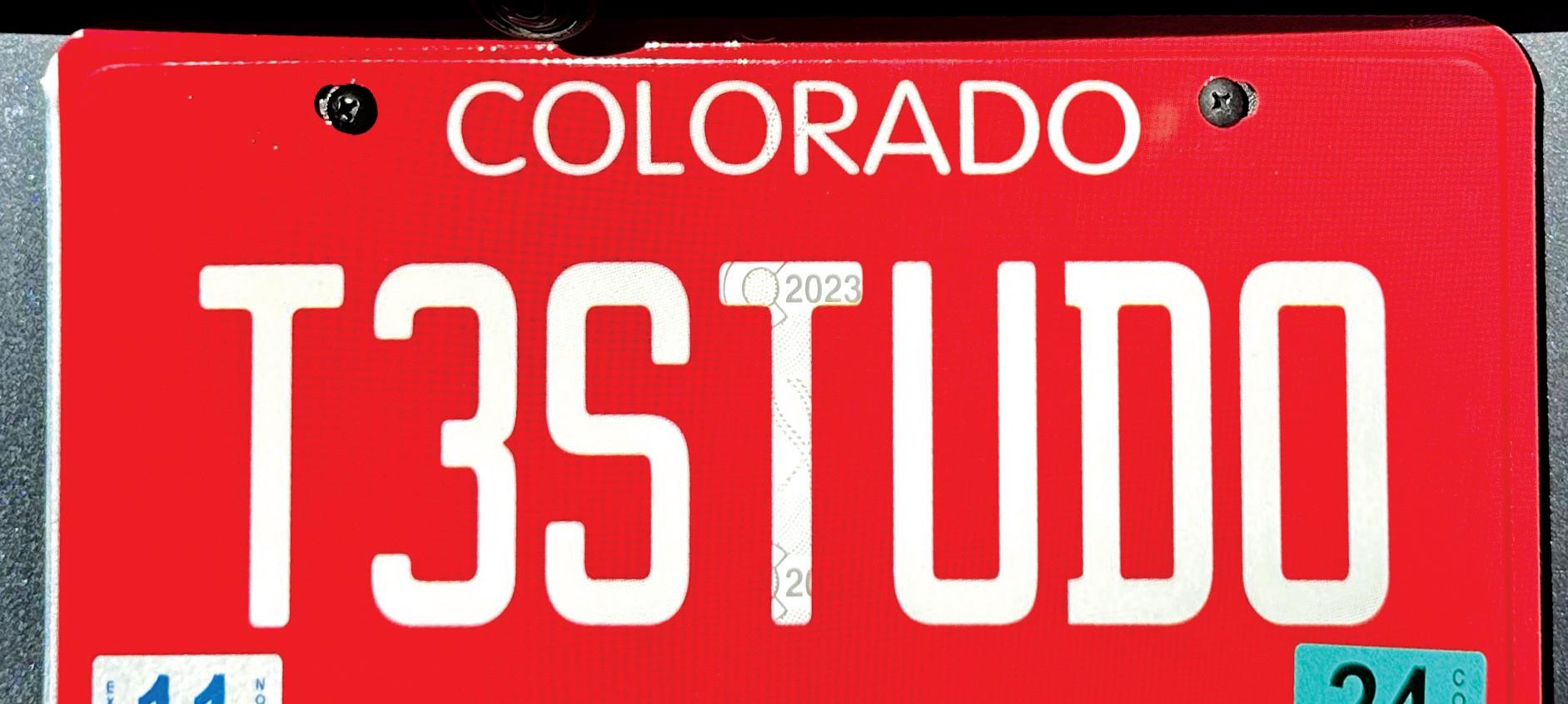

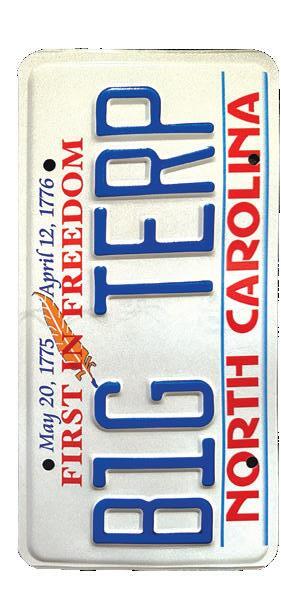

UMD-THEMED VANITY PLATES ARE THE HIGHWAY FOUR-LEAF CLOVERS WE LOVE TO SPOT. WE SHARE SOME OF THE BEST—AND THE TALES BEHIND THE TAGS. PG. 18

18 Driving Home Pride

UMD-themed vanity plates are the highway four-leaf clovers we love to spot. We share some of the best—and the tales behind the tags.

BY MAGGIE HASLAM24 Charging Up That Hill

Ninety-second battery fill-ups.

All-day range. Unparalleled safety. UMD researchers are powering up EVs to save the planet.

BY CHRIS CARROLL30 Wild Cards

The alum couple behind the bestseller Fluxx and other card and board games makes clever plays on a long, unconventional and winning journey.

BY SALA LEVIN ’10

Crescent Moons, Pink Hijabs and ‘Super Yous’ Alumna writes the books celebrating Muslim culture that she wishes she’d had growing up. —

It’s a Bird! It’s a Plane! It’s—the End of Humanity?

Students learn science and skills with “deep impact” in an asteroid collision course.

A VetMed researcher investigating a new canine respiratory disease calls for awareness and quick

spring sunshine warming your skin, a pillow of lush green grass and a lull in the afternoon—close your eyes to remember that scene and feel your blood pressure sink.

The afternoon I’m thinking of looked a little like that but zoomed out to include thousands of other Terps.

On April 8, we gathered en masse on the Glenn L. Martin Hall lawn, the engineering fields and McKeldin Mall, held those funny eclipse sunglasses against our faces, and looked skyward to watch the sun almost vanish behind the moon. At its apex, when the air had cooled and the light had dimmed, the crowd broke into cheers and applause.

It was a charming, singular moment on campus.

As I returned to the office, stepping between the students gobbling free cups of Dairy ice cream or tossing Frisbees and past two faculty members folding up their lawn chairs, I thought about how this wasn’t so different from what you’d find at a home football or basketball game or on Maryland Day: a communion of Terps.

This issue’s cover story celebrates another common experience. The variety of UMD-themed vanity plates out there amused writer Maggie Haslam so much that she spent one Sunday afternoon in the Terrapin Trail garage during a sold-out men’s basketball game to leave notes on 15 vehicles declaring Terp pride. She even followed the driver of a car sporting 1 TERPS on the Beltway in a failed effort to get his attention. (If you’re reading this, she says it’s not too late to contact her!) Maggie talked with more than 40 alums across the country about their custom plates and shares their best stories on page 18.

I hope you’ll also get a kick (or a bounce) reading our other stories, including one about the student vying to represent the U.S. in trampoline gymnastics in the Summer Olympics and another on the quirky alums behind Fluxx, a series of card games that has sold more than 4 million copies.

We do a U-turn back to cars to examine the efforts of Maryland’s engineers to develop longer-lasting, safer and cheaper batteries for electric vehicles. And we report on UMD’s all-in efforts to pursue AI that’s trustworthy and ethical.

Turn these pages, or turn and look around: Whether they’re trying to save the world or just make you smile, Terps are doing work that matters.

Lauren Brown University EditorPublisher

BRIAN ULLMANN ’92

Vice President, Marketing and Communications

Adviser

MARGARET HALL

Executive Director, Creative Strategies

Magazine Staff

LAUREN BROWN University Editor

JOHN T. CONSOLI ’86 Creative Director

VALERIE MORGAN Art Director

CHRIS CARROLL

MAGGIE HASLAM

ANNIE KRAKOWER

SALA LEVIN ’10

KAREN SHIH ’09

Writers

LUCY HUBBARD ’24

Editorial Intern

KOLIN BEHRENS

LAUREN BIAGINI

CHARLENE PROSSER

CASTILLO

Designers

STEPHANIE S. CORDLE

Photographer

DYLAN SINGLETON ’13

Photography Assistant

RILEY N. SIMS PH.D. ’23

Photography Intern

JAGU CORNISH

Production Manager

EMAIL terpfeedback@umd.edu ONLINE terp.umd.edu NEWS today.umd.edu FACEBOOK.COM / UnivofMaryland X twitter.com/UofMaryland INSTAGRAM.COM / univofmaryland

YOUTUBE.COM /UMD2101 LINKEDIN.COM /school/ university-of-maryland

The University of Maryland, College Park is an equal opportunity institution with respect to both education and employment. University policies, programs and activities are in conformance with pertinent federal and state laws and regulations on nondiscrimination regarding race, color, religion, age, national origin, political affiliation, gender, sexual orientation or disability.

COVER Photo by Anna Driscoll. Photo illustration by John T. Consoli. This plate takes creative “license,” as the Maryland Motor Vehicle Administration doesn’t—yet—offer symbols on vehicle plates.

When I was president of the Student Alumni Board (today’s Student Alumni Leadership Council), I donned the mascot costume once to cover for a friend who wasn’t feeling well and needed a quick break. Man, that costume was hot and heavy. I wasn’t nearly in shape to be Testudo for long, but in my 15 minutes of fame, I greeted then-Chancellor Robert Gluckstern by running up behind him and tapping him on the shoulder. He almost jumped out of his skin before smiling and giving me a high five.

—ROCKY LOPES ‘80, SILVER SPRING, MD.

Reading “Standing the Testudo of Time,” I was reminded of a recent family camping trip to the Delaware Seashore State Park, where diamondback terrapins digging their nests in the warm sand lay their eggs.

Signs posted along the roadside warn drivers to “Look out for turtles.” Occasionally, a driver stops and gets out of their car to assist a diamondback in avoiding traffic.

Conclusion: This experience

WRITE TO US

We love to hear from readers. Send your feedback, insights, compliments—and, yes, complaints— to terpfeedback@umd.edu or to:

Terp magazine Office of Marketing and Communications

7736 Baltimore Ave. College Park, MD 20742

proved what Terp magazine promotes: Terrapins are fearless, persistent and tough, and occasionally can use some help from a friend.

—JOHN L. JACOBUS ’63, SILVER SPRING, MD.Yet another “blast from the past” that I thoroughly enjoyed reading in Terp! The images and articles reminded me of the years I worked as a student for the Department of Agricultural Engineering in a building everyone walked by but virtually no one knew existed: the Shriver Laboratory. (It was built in 1938 and razed to make way for the Edward St. John Learning and Teaching Center.)

a calculator and a couple of pencils and chewing on a piece of rye. That terrapin could also be found eating a piece of watermelon and sipping a beer (yes, up to 1982, 18-year-olds could still drink beer in Maryland!) for the annual crab feast.

—ROBERT BAER ’82, COLLEGE PARK, MD.

I was its draftsman, and as a side task, they had me develop a series of new logos for the “Aggies.” They may not be remembered unless you happened to buy one of the AgEngineering T-shirts for a whopping $4.50 or were in the student chapter of the American Society of Agricultural Engineers.

For some reason, the department never used the dapper terrapin in the boater hat sipping a martini or the overalls-wearing farmer terrapin

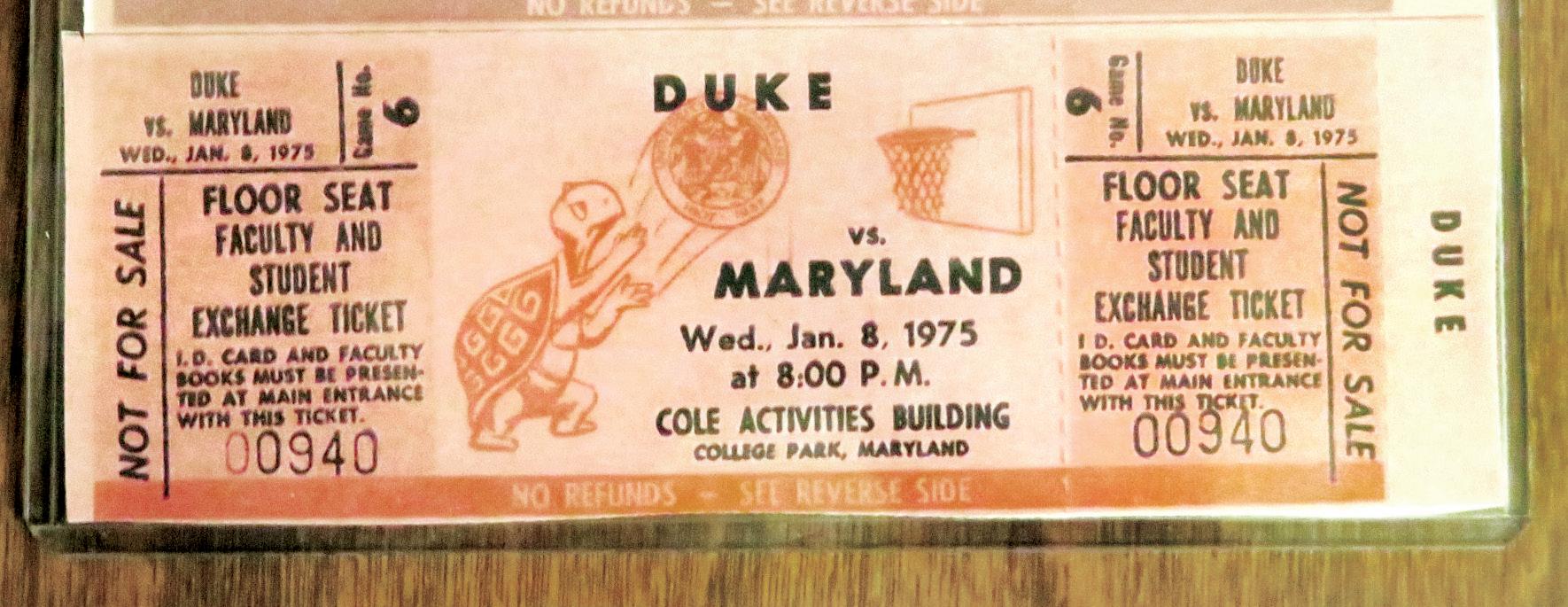

I’d like to share some more material about Testudo with you. First is a circa 1930 milk cap that I bought that was from the University of Maryland Dairy, as I am a collector of the forgotten glass milk bottles. It is a heavy paper like thin cardboard, printed and waxed. I also saved my tickets to basketball games. Notice Testudo throwing the university seal to a basketball hoop. Sometimes he is smiling, and sometimes he has an angry look.

—MIKE MARMER ’78, GERMANTOWN, MD.

DOZENS OF LABORATORIES and two shared research spaces packed with cutting-edge instruments are among the features of UMD’s new Chemistry Building, which will catalyze the work of scientists pushing the boundaries of their fields.

“It is designed purposefully to enable faculty members and students to share ideas, solve problems and ask new questions about our natural world,” Janice Reutt-Robey, professor and chair of the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, said at April’s dedication ceremony.

“The environmental features of the new building—strict temperature and humidity control, optimal thermal management and regulated airflow—will allow us to push our research to new heights.”

The facility, funded by the state and university, is expected to house research on some of the biggest problems society faces, from infectious diseases and pandemics to climate change.

Research to Focus on Responsible

he university of maryland this spring launched a major hub dedicated to developing the next generation of artificial intelligence education, technology and leaders.

Its new AI Interdisciplinary Institute at Maryland (AIM) will support faculty research, offer hands-on learning experiences, and focus on responsible, ethical development and use of a technology expected to be revolutionary—all to advance the public good.

“Artificial intelligence continues to grow exponentially, creating opportunities to solve the grand challenges of our time. With this institute, our experts will work together to globally lead responsible AI development that spurs economic growth and promotes human well-being,” says UMD President Darryll J. Pines.

AIM builds on the university’s existing AI expertise and centers, including the Center for Machine Learning, the National Science Foundation-funded Institute for Trustworthy AI in Law & Society (TRAILS), the ValueCentered AI Initiative and the Social Data Science Center.

“We’re fortunate to have AI experts in fields ranging from computer science and engineering to journalism, education, social sciences, business and the arts—a unique breadth of expertise,” says Senior Vice President and Provost Jennifer King Rice. “By uniting our efforts under one institute, we will not only become a magnet for AI development and research but a global leader in preparing students and the

workforce for an AI-infused world.”

The institute will help students of all majors learn how to apply the principles of AI to their fields; it will also coordinate the development of new AI degrees and expanded courses, a professional certificate and other workforce development programs.

“Artificial intelligence continues to grow exponentially, creating opportunities to solve the grand challenges of our time.”

—DARRYLL J. PINES, UMD PRESIDENT

AI-infused systems have the potential to enhance human capacity and creativity, mitigate complex society challenges, and foster innovation, says AIM Director Hal Daumé III, a Volpi-Cupal Family Endowed Professor in the Department of Computer Science.

“Achieving this requires a joint effort between those pushing the boundaries of new AI technologies, those who innovate AI applications, and those who study human values and how people and society interact with AI,” he says.

LONGTIME BENEFACTORS of the University of Maryland have made a new $27.2 million gift to the Department of Mathematics to endow the Brin Mathematics Research Center, establish a new endowed chair and pilot a camp for talented high school students in the state.

The gift from UMD mathematics Professor Emeritus Michael Brin and his wife, Eugenia, a retired NASA scientist, is the fourth-largest outright gift to the university from an individual and the largest ever to the department. The couple gave $4.75 million to establish the center in 2021.

“We are always happy to help support the Department of Mathematics at the University of Maryland,” says Michael Brin.

The Brin Mathematics Research Center, which will receive $25 million of the new gift, is a platform for UMD to expand and spotlight its mathematics and statistics research excellence nationally and internationally. The center brings hundreds of mathematicians to the university every year for workshops, summer schools and distinguished lectures. Since its launch, the University of Maryland rose to become the No. 20 graduate-level math program, and No. 6 among public institutions, according to U.S. News & World Report

“This generous gift from the Brins ensures that the research and scholarship taking place in the Brin Mathematics Research Center will continue for generations to come,” said Amitabh Varshney, dean of the College of Computer, Mathematical, and Natural Sciences. “The additional support for an endowed chair is critical for recruiting and retaining the best faculty members in mathematics, and we’re excited that the summer camp will bring young scholars to College Park to explore our programs and campus.”

Michael and Eugenia Brin, parents to Google co-founder Sergey Brin ’93 and Samuel Brin ’09, have made other significant gifts to support UMD’s computer science and math departments, Russian program; and School of Theatre, Dance, and Performance Studies.

MOST POPULAR FLAVORS

1 Cookies and cream

2 Sapienza (named for the former executive assistant to three presidents, Sapienza Barone ’77)

3 (Tie) Cookie dough and mint chip

NATIONAL HISTORY DAY COMPETITION (June): Between World War I and Olympic trivia, nearly 3,000 middle schoolers and families from all 50 states and around the world fuel up on frozen delights. “The line is there all day, every day that week!” says Robertson. MARYLAND DAY (April): The team creates a unique flavor each year for UMD’s open house.

EARLY FALL

SEMESTER : A bevy of welcome events, new Terps’ discovery of Dairy ice cream and everyone else’s renewed access to it require Russo’s crew to make fresh batches five days a week.

Look Back on the Maryland Dairy’s Funky Flavors and Coach-Inspired Creations

24 FLAVORS EVERYTHING FROM SCRATCH

“Nothing comes out of a can,” says Russo. “If I’m doing caramelized pecans, I roast them, I sugar them, I salt them. Brownie chunks?

Those don’t come out of a box.” Three to four staff members surround the ice cream machine to add nuts and candy at just the right times to keep them from getting pulverized.

14% BUTTERFAT (higher than the 10% standard)

irst, let’s mooove beyond the misconception that the University of Maryland’s Dairy ice cream is made from the milk of campus cows. (Only two remain on the farm, anyway.) That was true a century ago, when cattle grazed in the fields and barns along Baltimore Avenue, just steps from where their milk was churned into frozen delights. And it remained so until the 1960s, when the expensive and labor-intensive process was bid out and the university switched to a commercial mix.

But Dairy ice cream is still the fodder for many Terps’ fondest memories, whether they polished off a 10-cent scoop while sitting on the

Starting with former football coach Ralph Friedgen in the early 2000s, the Dairy has created specialty flavors for some of the Terps’ winningest leaders (including university presidents). Men’s basketball coach Kevin Willard’s is based on his fandom for peanut butter and jelly, while women’s lacrosse coach Cathy Reese appropriately added Reese’s Cups and Pieces. Nibbling the first iteration of her flavor, she quickly caught on: “So if I keep changing something, I’ll get another tasting every week?” gallons created each year

Terps don’t have to head to the Stamp to get their favorite variety. On campus, units can order mobile ice cream carts to get hand-dipped cups or pre-scooped options (popularized during the pandemic). Nostalgic alums can order half-gallons to be shipped anywhere in the United States by emailing marylanddairy@umd.edu.

10 , 000 +

The Dairy team regularly makes custom ice cream for UMD units and clubs—Campus Squirrel Crunch, anyone?—as well as special celebrations:

• CHESAPEAKE WILD BERRY RIPPLE (for Maryland’s 350th anniversary in 1984): featuring three kinds of berries available when the first Europeans arrived. “It was kind of a pain to produce, but we kept it up for a year, and legislators kept asking us to bring it back,” says LaPanne.

• STAR-SPANGLED EXPLOSION (for the 200th anniversary of the War of 1812): strawberry ice cream spiked with sherry and swirled with red, white and blue sprinkles and milk chocolate malted (cannon) balls.

brick wall outside Turner Hall or still proudly display the Adele’s sundae bowl—“the Trough”—from treating their parents with extra Dining Points.

Established as an agricultural college, the university initially focused on crops and planting methods, rather than livestock. The dairy program began in the late 1890s, and in 1924, the Dairy building along Baltimore Avenue opened to serve as a lab and salesroom for butter, cheese and, of course, ice cream.

Flavors remained pretty vanilla until College of Agriculture Professor Wendell S. Arbuckle, known as “Mr. Ice Cream” for his extensive research on the subject, took the reins in 1949. “That man believed you could make an ice cream out of any flavor,” says Gary LaPanne, who led Dairy operations in the 1980s and 1990s. “We’re talking vegetables— asparagus and green beans—and even grass.”

Arbuckle consulted internationally, and for decades, AGNR faculty taught an annual two-week course on how to make ice cream. (It drew not only professionals but also “a lot of lawyers who were tired of their jobs and wanted to open their own ice cream shops,” LaPanne says.) Grocery chains jumping on the low-fat craze in the 1990s turned to UMD ’s facility to create small test batches. In 2004, Dining Services took over production, and in 2014, the Maryland Dairy moved to the Stamp Student Union, where increased foot traffic quadrupled ice cream sales. To celebrate its 100th anniversary, the Dairy team recreated fan favorites for each month of the school year.

Top: Students order Dairy favorites like sundaes, milkshakes and ice cream at Turner Hall (then known as Shriver Laboratory) in 1964.

Bottom: Professor Wendell Arbuckle, known as “Mr. Ice Cream,” measures ingredients for ice cream in an undated photo.

Dining Services Executive Pastry Chef Jeff Russo and Stamp retail operations Assistant Director Dan Robertson dish out a few secrets about UMD ’s favorite dessert, what it takes to develop specialty flavors and how to get Dairy ice cream when you’re not in College Park. —ks

Anna tovchigrechko ’26 became accustomed to the eight-hour car ride to a Walmart in rural upstate New York, near Niagara Falls. Each time, the middleschooler and her dad ticked off the essentials on their shopping list: clothes (but nothing orange, blue or gray), shampoo (but no brands that had alcohol as one of the first few ingredients), snacks.

Then they’d take their haul a few miles away, to the prison where Tovchigrechko’s mom, a former attorney, was serving a

five-year sentence. The visits always seemed too short.

“When it would be time to go, I just remember looking out the window and being really sad that we had such a good time, but now I was leaving and she was still in prison,” she says.

Back home in her comfortable Montgomery County, Md., neighborhood, she didn’t know anyone else with an incarcerated parent. And she thought she couldn’t tell anyone, especially after an uncomfortable conversation with a school counselor.

“I remember her being very shocked, in a way that you wouldn’t want an adult to be surprised like that.”

The isolation Tovchigrechko (left) felt is one of the factors that motivated her to start the UnLocked Project, a new University of Maryland group that provides a community for students who have or have had parents in prison to talk about their experiences with others who have shared them.

Nationally, some 5 million American children—most under age 10—have had an incarcerated parent at some point. That can translate into a significant loss of income to the family, and court-related fees and fines, as well as the cost of visiting an incarcerated parent, may exacerbate financial woes. Parental incarceration is a blow to mental health, too—researchers have found that having a parent go to prison can be a traumatic experience for children on the same level as abuse, domestic violence or divorce.

The UnLocked Project’s meetings have been “a breath of fresh air,” says Da’Juana Savage ’25, whose dad has been in and out of prison, starting when Savage was 3 years old. “I was able to have an open discussion about my story and have a space where I felt like I could breathe and not feel like anybody was judging me.”

For Savage, having an incarcerated parent wasn’t the unique experience that it was for Tovchigrechko. “Growing up in Baltimore, it’s really common. A lot of people don’t have their fathers or mothers in their lives,” she says. “Is it talked about? No.”

Tovchigrechko hopes that the UnLocked Project can be a unifier. “Even in this small community of people, people’s needs are different, but at the same time, we’re all kind of the same, because we left that discussion very much relieved and feeling like we’ve found a community of people who are willing to talk about it,” she says.—sl

COULD A GIANT Testudo shell packed with games entice students to pause and learn about voting? What about a mysterious-looking stack of black boxes? Or a multistory projection onto a building?

Those are among the many ideas from a new class this spring, “Design and Democracy,” that brought together architecture, public

policy, government and politics, and art majors to develop pop-up proposals to encourage college students to register and cast ballots this presidential election year.

Hannah Smotrich, an associate professor of design at the University of Michigan who is the Arts for All designer-in-residence at UMD, and UMD architecture Professor Ronit Eisenbach co-taught the course, bringing in election experts to talk to students about the importance and challenge of increasing civic engagement. Americans aged 18-24 turned out to vote at the lowest rate of any age group in the 2020 election, according to the U.S. census.

“How do we get students to not only see that voting is

important, but figure out how to actually vote?” Eisenbach says.

Since STEM majors are less likely to cast a ballot, students focused on engaging engineering majors by rendering installation ideas, designing pamphlets and posters on the registration process, and developing survey questions on voting (or non-voting) behaviors. Then, they formed multidisciplinary teams to scale up their ideas, culminating in an exhibit at the end of the semester.

“Maryland is lucky that there’s an amazing group of people interested in this work of expanding civic participation,” Smotrich says. “If these creative projects can bring more people into the conversation, that’s a win.”—KS

IT’S MCKELDIN MALL —just blockier.

With painstaking detail, Giuseppe LoPiccolo ’25 is recreating the UMD central quad’s stately red-brick buildings, sparkling ODK Fountain and zigzagging pathways in the bestselling video game Minecraft.

“You want to make it look realistic, but it’s hard to find the right materials and scale the features,” says the government and politics major. “There’s a ton of hurdles.”

To overcome them, he’s carefully studied publicly available blueprints, used his skills as The Diamondback’s photo editor to take pictures and videos from every angle, and even relied on his girlfriend’s expertise as a plant science and landscape architecture major to help him figure out terrain.

A Minecraft aficionado since he was 9, LoPiccolo frequently streams his sessions on Twitch to followers from as far as Greenland and the United Kingdom. Once he finishes, he plans to distribute his build so others, like Maryland Images tour guides and prospective students, can explore what he’s created.—KS

See more screenshots at today.umd.edu/ um-ade-in-minecraft

essica stevens ’24 starts with one bounce. Two. Three. Then suddenly, she rockets into a triple flip, two stories in the air, and springs back up into a dizzying series of tucks and twists, forward and backward, like Tigger unleashed—but with perfectly pointed toes. This isn’t playtime on a backyard trampoline. The UMD senior is one of the world’s top athletes in trampoline gymnastics. She won a bronze medal at the world championships in November— the first American in half a century to earn a podium spot—and qualified the United States for a berth at the 2024 Olympic Games in Paris.

J“I still can’t believe it,” she says. “I go back and watch my videos, and I’m like, ‘Wait a second—that was me!’”

Trampoline gymnastics, an Olympic event since 2000, is a separate discipline from better-known, Simone Biles-dominated artistic gymnastics. Trampoline athletes are judged on how well they can execute 10 skills during a roughly one-minute routine as they reach heights of 20 feet or more, flipping and twisting while trying to stay centered.

“I love the feeling of flying,” says Stevens. “It’s so peaceful up in the air.”

She started in gymnastics as just a toddler, and jumping on the trampoline quickly became her favorite part. By the time she was 13, she’d qualified for the national team, and at 17, she competed at the world championships in Bulgaria for the first time.

Stevens’ schedule is relentless. The U.S. competition circuit runs from February through June, and international competitions dot the year, so she rarely has downtime. She starts her day at 7:30 a.m., juggling in-person and online classes (going part-time this spring to focus on the Olympics) with two training sessions at the Fairland Sports and Aquatics Complex in Laurel, Md. Yet she decided not to delay higher education in order to set herself up for a career in the legal field; she knows her body can bear the rigors of the sport for only so long.

After earning an associate’s degree, she enrolled at UMD in Fall 2022 as a criminology and criminal justice major and Russian studies minor. Her professors have been a “godsend” in understanding her complicated schedule, she says.

Her beginner Russian skills are giving her a leg up in her training. Her coach, Konstantin Gulisashvili ’19, M.Arch. ’23, is from the Republic of Georgia, a former member of the Soviet Union, so when she visited his homeland for a training bloc last year, she was finally able to communicate with other experienced coaches and trainers who spoke no English.

“I started out not even being able to say hello to them, and now they can tell me to jump higher, work on certain things— even offer me tea,” she says.

Gulisashvili says her work ethic, both in class and at the gym, sets her apart. And as the youngest finalist at worlds, she has a “very bright future” in the sport, he says. “I don’t think she’s at her peak.”

This spring, Stevens competed at two Olympic trials and has one more in June, where she’ll find out if she’s been selected to represent the U.S. in July. She’s grateful for the support of the U.S. Olympic Committee, which flew her out to the Colorado Springs Olympic and Paralympic Training Center and has given her access to top sports medicine doctors who can treat aches and injuries that stump regular physicians.

“I’m really proud of where I am right now,” Stevens says. “I really want to get to the Olympics, but you also have to enjoy the journey.”—ks

THE UNITED STATES WOMEN’S field hockey team again won a role on the Olympic stage, and several Terps provided an assist.

Sisters Emma ’23 and Brooke DeBerdine ’21 and Kelee Lepage ’20 lined up with Team USA as it came from behind to defeat Japan, 2-1, in January’s FIH Women’s Hockey Olympic Qualifiers in Ranchi, India. The victory punched the team’s ticket to Paris after it missed the cut for the Tokyo Games in 2021.

Three other Terps—Linnea Gonzales ’19, Josie Hollamon ’27 and Hope Rose ’24—were also on Team USA’s roster leading up to the 2024 Games. The squad, hoping to return to the Olympic podium for the first time since earning bronze in 1984, will announce a final 16-player roster with up to three alternates this summer.—AK

FORMER UMD TRACK and field star

Thea LaFond ’15 leapt to a global victory in March, taking gold in the triple jump at the World Athletics Indoor Championships in Glasgow, Scotland.

Representing her home country of Dominica, she jumped to a personal-best 15.01 meters. The win made LaFond, an All-American and top-five all-time finisher in multiple field events at Maryland, her nation’s first global champion in any athletic discipline.

“We’re just a little island with a population of 70,000 people, so this one is for my people,” she said. “I am hoping that this inspires the next generation of young Dominica athletes to just go for it.”

TWO GROUNDBREAKING ceremonies this spring signaled the first steps toward new training facilities for UMD’s baseball and softball programs.

The Stanley Bobb Baseball Player Development Center and the Softball Player Development Center will both feature climate-controlled spaces for pitchers and hitters to train year-round and new technology to aid with analytics. The projects are part of Maryland Athletics’ Building Champions initiative to enhance facilities across UMD sports.

“(Terps) will have the opportunity to continue their pursuit of athletic excellence within a space that’s going to expand our training abilities,” softball head coach Lauren Karn said at her team’s ceremony. “All of that aside, they’re going to be creating great memories through all the hard work that’s going to be done in here.”

nearsighted writer isn’t the logical choice to take the wheel of a half-milliondollar lunar rover prototype funded by the agency that gave us “one giant leap for mankind.”

ABut on a gravel track at nearby NASA Goddard Space Flight Center one spring afternoon, four UMD engineering students and one veteran faculty member wrestled me into a 75-pound space suit and gave me a (hopefully non-) crash course on driving the one-seat all-terrain vehicle they had dedicated three years to building—not to drive publicity, but to steer closer to perfection.

Developed under NASA’s Innovative Advanced Concepts program, the prototype could help inspire the finished product: a vehicle for astronauts to one day navigate the pockmarked surface of the moon as they build a base to slingshot human explorers to Mars.

The UMD rover is capable of climbing 30-degree slopes—a feat the team tested on a hill outside one of the university’s engineering buildings—rotate 360 degrees, and travel on extended journeys, thanks to a battery located under Baja 500-worthy 30-inch suspension coils.

But what’s unique about this set of wheels is how it lightens astronauts’ load—which, trust me, is heavy—by replacing the support systems traditionally lugged in a backpack with an umbilical life-support arm. Hooked directly into the suit, it offers longer stretches of exploration, ample freedom of movement and less fatigue.

“It’s been amazing to see what they’ve done here,” says Brent Barbee, a NASA flight dynamics engineer and lecturer at UMD. “I find it really innovative.”

Hoisting myself into the driver’s seat, operating the controls, even fastening the seatbelt are all drastically different experiences in a bulky spacesuit, which was sort of the point of the test drive. A quick flip of a finger swiveled the vehicle’s enormous mag wheels (ordered

from a tractor supply company) left and right, quickly veering me toward a drainage ditch; but within minutes I was effortlessly cruising at a casual 10 mph along the edge of Goddard’s property in Greenbelt, much to the astonishment of a groundskeeper at a neighboring apartment building.

The team, overseen by aerospace engineering Professor David Akin, will take lessons learned from the test run back to the lab for tweaks before it demos the rover to more NASA representatives later this spring, with someone else at the controls.

“We are constantly working, constantly trying to improve it,” says doctoral candidate Charlie Hanner, one of the project leads. “Hopefully we can contribute something that’s never been done before.”—mh

ASK THE EXPERT ADVICE FOR

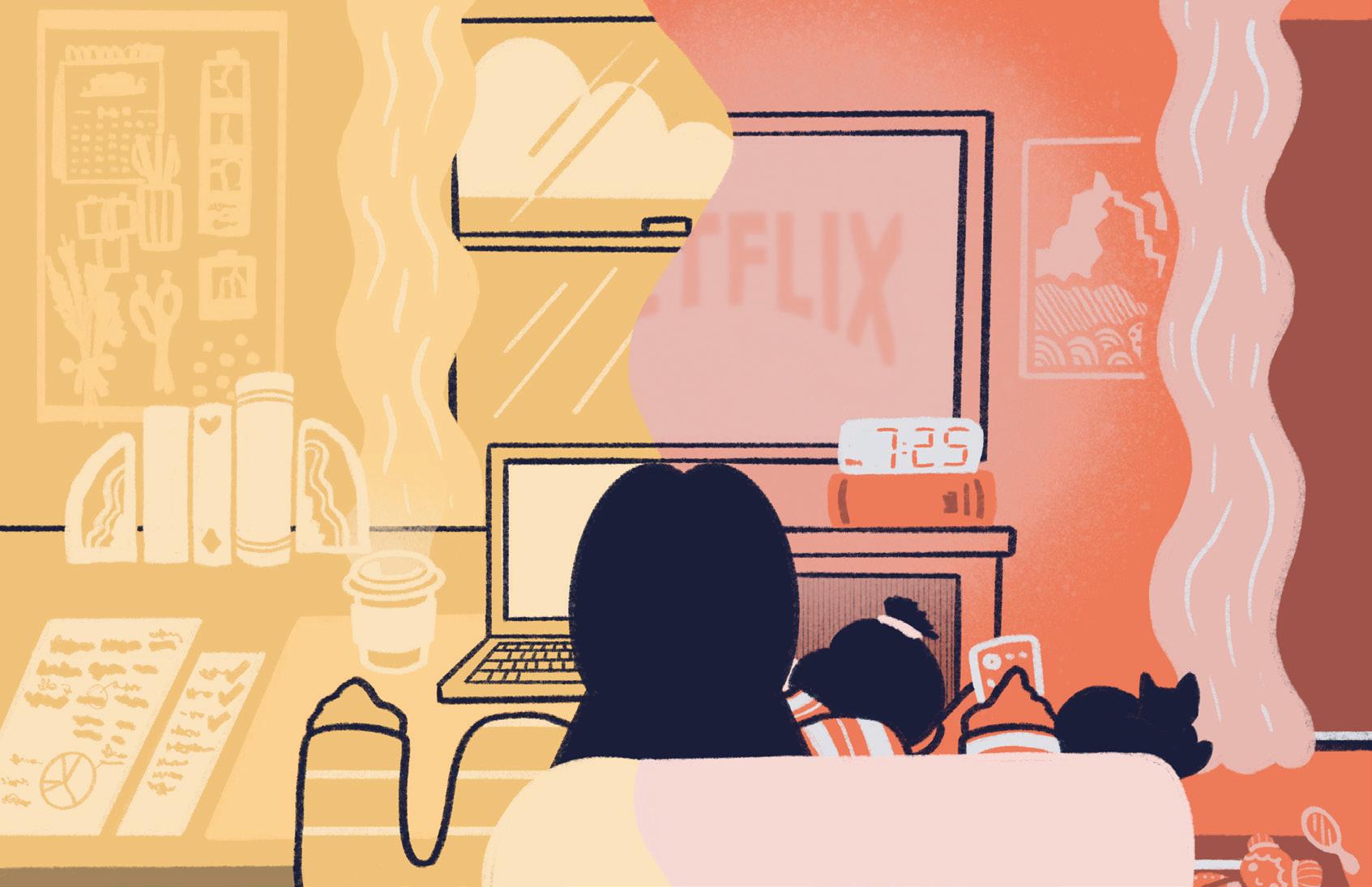

BOUNDARIES? WHAT BOUNDARIES? Since the pandemic, the membrane between jobs and home life has thinned. Hybrid and remote options offer more flexibility, but also more late-night catch-up sessions and opportunities for burnout.

Management and organization Clinical Professor Nicole Coomber studies work-life balance and says the two areas can “complement each other, rather than being in conflict.” The mom of four draws from personal and professional experience to offer four tips:

BREAK UP THE DAY “Studies show the highest-level performers in anything, from sports to artistic endeavors, are only good for about 90 minutes maximum,” says Coomber. She recommends taking breaks and tackling other tasks to stay productive and creative.

RETHINK ASKING PERMISSION If you struggle with kid pickup at 3 p.m., consider making it a late lunch break. “People have blocks on their calendars for all sorts of reasons,” she says. “Know your responsibilities, your organization’s policies and ask yourself if you need to reveal more than is necessary, as long as you’re getting things done.”

FOLLOW THE RULE OF THREES “What are the three things I have to get done each day, each week, each month?” she says. That can help you prioritize as you decide whether to work on a Sunday so you can coach Little League later, or if you’re thrust into caregiving for an elderly parent and need to call in from a hospice center.

KNOW YOUR BODY With email notifications ever-present, it can be hard to disengage after hours. Be aware of when you work best. “My husband likes the quiet time after the kids are in bed to read and think for 45 minutes without distractions,” says Coomber. “But I know my brain is mush after 9 p.m.”—KS

WHAT DOES YOUR favorite poultry dish recipe have in common with … Department of Defense classification procedures?

While one results in a scrumptious dinner and the other in secure data, both require a complex step-by-step process. Now, with a mandate to digitize all federal records taking effect in June, experts at the University of Maryland’s Applied Research Laboratory for Intelligence and Security (ARLIS) are eating up that analogy, testing an artificial intelligence tool on 2 million recipes to see it if offers clues for simplifying classification guidelines.

As part of the Pentagon-funded project, the research team used its machine learning tool to scan recipes.com listings for commonalities, like using flour, eggs and seasoning for chicken parmesan, chicken katsu and schnitzel.

“If someone’s building the ultimate breaded chicken recipe, they can see what is inherently the same across all of those and spit that out,” says project lead Michael Brundage, an associate research engineer at ARLIS. “Then, experts can come in and debate whether that step needs to be included or not.”

As the researchers fine-tune the technology, the idea is to similarly use it to efficiently analyze the more than 1,000 classification and declassification guides across the DOD, pick out the common rules and cook up a streamlined security protocol.—AK

RESEARCHERS AT UMD and the National Institutes of Health have identified the enzyme responsible for making urine yellow, and it’s more than a matter of idle curiosity or grade-school giggles.

The discovery of bilirubin reductase, introduced in a study published in the journal Nature Microbiology, paves the way for further research into the gut microbiome’s role in ailments like jaundice and inflammatory bowel disease. It also brings scientists closer to a holistic understanding of how the gut’s resident microorganisms contribute to overall health.

Red blood cells release a bright orange pigment, bilirubin, as they grow old and degrade. The newly described enzyme, produced by gut microbes, initiates bilirubin’s two-step breakdown into the chemical that gives urine its characteristic hue.

“It’s remarkable that an everyday biological phenomenon went unexplained for so long,” says lead author Brantley Hall, an assistant professor in the university’s Department of Cell Biology and Molecular Genetics.—EMILY C. NUNEZ

A NEW UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND center highlighting how the social sciences and arts can create social change gets its inspiration from one of the great Marylanders.

The Frederick Douglass Center for Leadership Through Humanities, housed in the College of Arts and Humanities, officially launched in April with an event featuring renowned poet Nikki Giovanni. Already, the center has hosted a workshop on book-banning legislation, a conversation with veterans of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and a summer institute for local teachers on a variety of education issues.

“Our motto is ‘Learn, lead, liberate,’ so everything we do is really trying to think about how we can encourage access to education, encourage people to be leaders, and think about the notion of equity in every component of society on and off campus,” says Director and English Professor GerShun Avilez.—SL

ASK SHELBI NAHWILET MEISSNER what her doctoral dissertation was about, and the assistant professor in the Harriet Tubman Department of Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies might just roll up her sleeves and show you.

The daughter of a citizen of the La Jolla band of the Luiseño Indians, Meissner has tattoos on her forearms depicting her thesis of the traditional craft of basket weaving as a metaphor for how to conduct research—along with foods, animals and symbols important to her tribe.

Here, Terp takes a guided tour of Meissner’s ink to learn the stories behind them.—SL

OAK LEAVES AND ACORNS

Turned into pudding and flour, black oak acorns are a staple food of the Luiseño. “It takes 1,000 pounds of acorn to feed one person for a year, and we harvest enough for entire villages to be able to sustain themselves for multiple years,” she says.

QUAILS

In one Luiseño story, a blind man lost in the mountains is guided home by the quail’s call. The story is a reminder that “if you can sit and center yourself and listen to teachings or your ancestral knowledge systems, those will guide you,” says Meissner. Her three quails represent herself, her mom and her sister, who share the same tattoo.

SKIN STITCH TATTOO

The tiny artwork on her wrist is an example of a method being revitalized by Coast Salish artist Dion Kaszas, in which a thread is dipped into ink, then sewn into the person being tattooed. Meissner got hers as one of 30 people tattooed during a ceremony. “He had all of us in a circle getting these tattoos that connected us.”

In Luiseño teaching, Spiderwoman doesn’t speak a human language, but is still able to transmit her knowledge of basket weaving.

“I have Spiderwoman to remind me that even in moments where it seems like our communities might not be able to communicate (because we don’t speak the same language), that doesn’t mean we don’t still have a connection.”

The four baskets on Meissner’s arm, depicted from a bird’s-eye view, represent the chapters of her dissertation:

SNAKE: Symbolizes how an Indigenous researcher can move “strategically and carefully” through academia.

CANOE: Represents Indigenous people as expert guides, leading researchers through the difficulties of translating Native languages.

STARS: Symbolize the Seven Sisters, a constellation that, in Luiseño teaching, is seven women sharing one husband; in Meissner’s view, it’s a feminist story about using different types of knowledge to work together.

COMPASS: References a Luiseño comingof-age ritual, and reminds Meissner to be guided by the teachings of her elders.

YOUR EARLY-MORNING TIME on the treadmill is doing more than getting you in shape for your beach vacation. According to kinesiology Professor J. Carson Smith, it’s also ensuring you’ll remember it.

Smith, who watched his own grandmother succumb to Alzheimer’s disease, has explored the link between exercise and brain health for over 20 years. His team at UMD’s Exercise for Brain Lab is now mining high-quality MRI data from hundreds of subjects to help further understand the brain’s response to exercise—and to offer diagnostic proof that movement is medicine for memory.

Below, Smith offers a peek inside the aging brain and explains why we should all be lacing up our sneakers.—MH

What’s happening in the brain as we age?

Inflammation intensifies and challenges the neural systems and how they operate. Our metabolic health plays a role too: If the brain isn’t getting enough energy, cells begin to die off in areas like the hippocampus. Not only will you have problems recalling short-term memories, you can’t transform them into long-term memory.

How does exercise affect that process?

What we’re finding is that exercise can strengthen, even regenerate the connections between brain networks responsible for a person’s ability to think clearly and recall memories. After just one session of exercise, subjects are able to learn better, but we see improvements in many different functions. People are faster and more accurate on testing, their executive functioning is improved, and they have better memory recall.

Could your findings translate to other issues, like mental health?

Oh, of course. We find that exercise impacts areas of the brain that regulate your mood; it’s protective against depression. A study by a former doctoral student on mood after exercise found that exercise quieted a brain network that is overactivated with depression and anxiety. So

that’s an area we’re also studying. It has a lot of appeal because many people struggle with mental health.

Can exercise be protective?

I think we’re a far cry from saying it’s a cure for anything, but for Alzheimer’s, it certainly can be useful as an adjunct to other treatments, and it might protect people from getting it for a certain amount of time.

Who should care about this?

We all should. After the age of 35, cognitive abilities start to decline. Exercise is a lifestyle behavior that works across age, sex and genetics. Yet it’s inaccurately prescribed; it’s not paid for by health plans or insurers as a treatment. But you can give a dose of exercise, and it has a real effect on these brain networks that could, over time as those doses are repeated, generate changes in the brain that would be good for you.

RUMORMONGERS, blabbermouths, busybodies—no matter what you call them, gossipers get a bad rap. But a study by University of Maryland and Stanford University researchers argues that those who exchange personal information about absent third parties aren’t all bad.

Gossipers can boost levels of cooperation within social circles, according to research published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences that used computer simulations to show gossip is a source of valuable intel.

“When people are interested in knowing if someone is a good person to interact with, if they can get information from gossiping— assuming the information is honest—that can be a very useful thing to have,” says co-author Dana

Nau, a retired professor in UMD’s Department of Computer Science and Institute for Systems Research.

Nau worked with first author Xinyue Pan M.S. ’21, Ph.D. ’23 and co-authors Vincent Hsiao ’18, Ph.D. ’24 and Michele Gelfand of

Stanford Business School; he says the simulation isn’t entirely true to life, but provides valuable behavioral insights—and cover for the next time someone tells you to mind your own beeswax.

—EMILY C. NUNEZFROM THE RAPID global spread of COVID-19 to the damage wrought by snarled supply lines, the pandemic provided lesson after lesson in how we’re all connected. Now UMD researchers are investigating another link to the virus, one that might extend even further.

Assistant Professor Travis Gallo and Associate Professor Jennifer Mullinax of the Department of Environmental Science and Technology are tracking deer to find out if they’re spreading COVID and other respiratory illnesses like influenza, or even serving as disease reservoirs that keep such viruses circulating.

Their study is supported by a $3.6 million cooperative agreement with the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service; it’s part of a larger agency effort to create an early warning system of disease spillover from

animals to humans.

The researchers will place GPS tracking collars on at least 45 white-tailed deer—a species that earlier UMD research showed frequently beds down in neighborhoods—and take nasal swabs and blood samples for lab testing. The collars will transmit information about deer movements over two years, and combined with human movement data from cell research participants’ phones, will pinpoint locations and times of human-deer encounters.

With a model of how people and deer neighbors move around the landscape, “we can use a predictive model to ask questions about potential interventions like controlling the deer population in certain areas, educating people about interacting with deer or even giving deer vaccines, to predict if we can reduce the risk and rates of disease transmission,” Gallo says.—KIMBRA CUTLIP

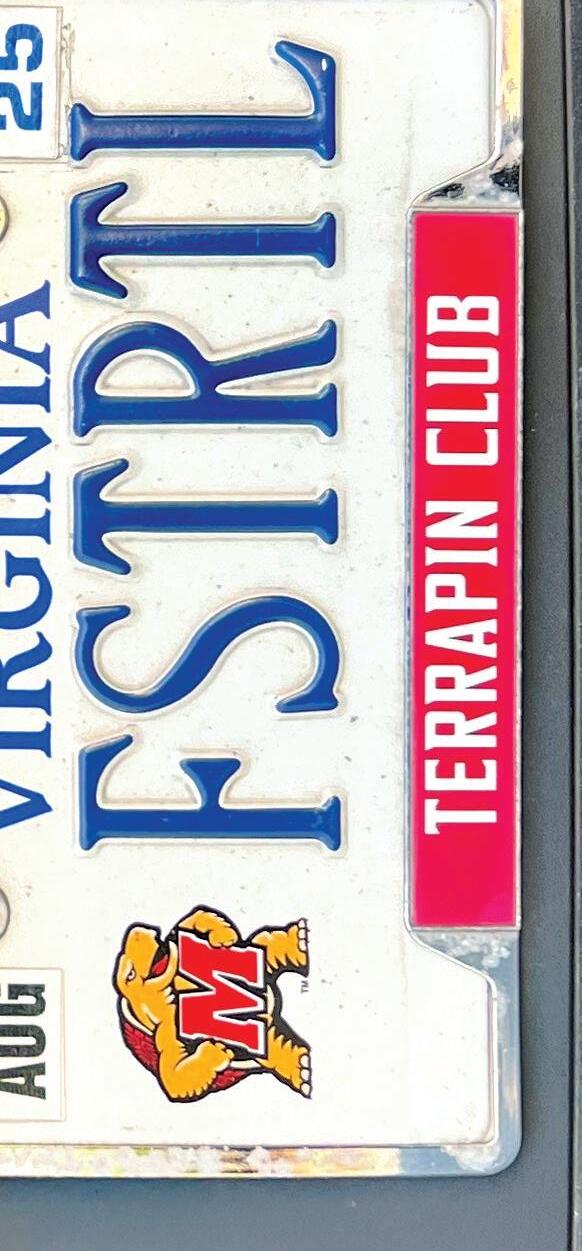

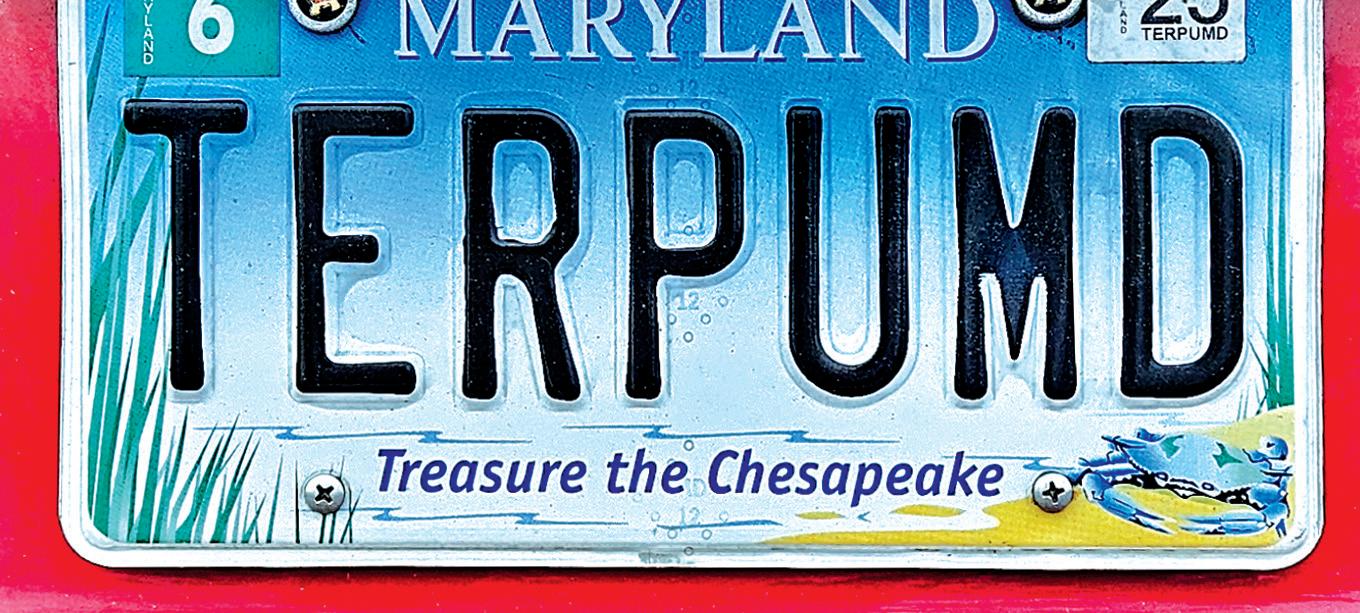

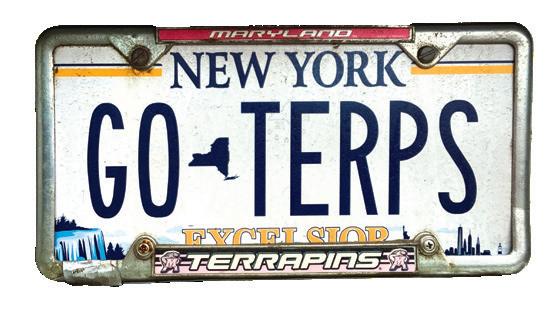

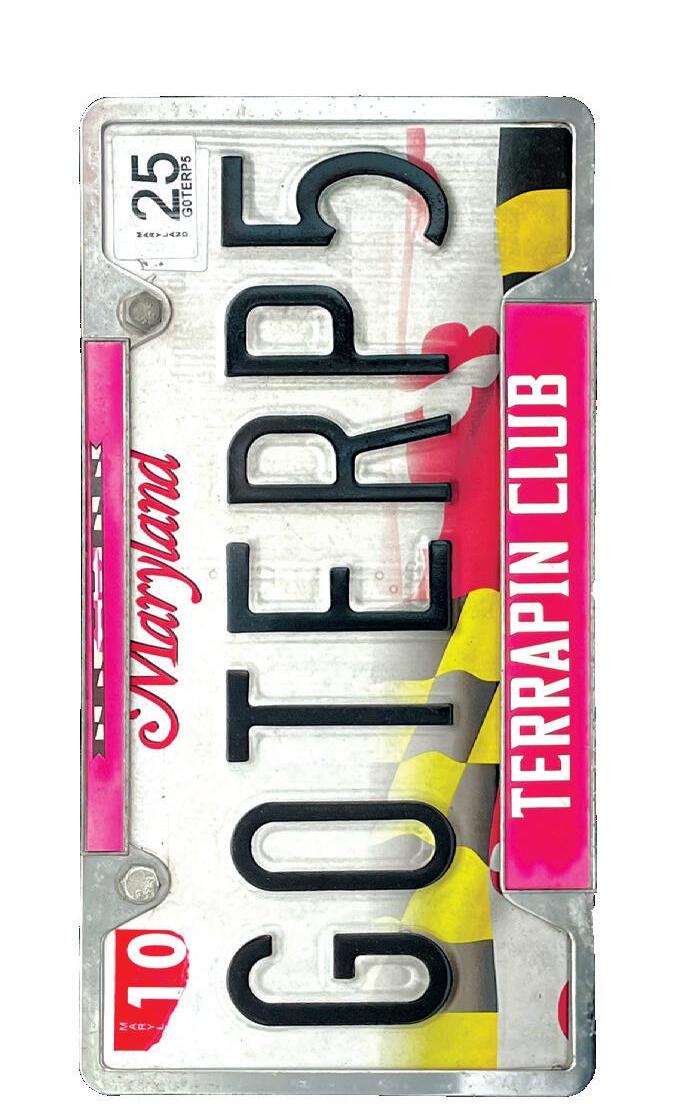

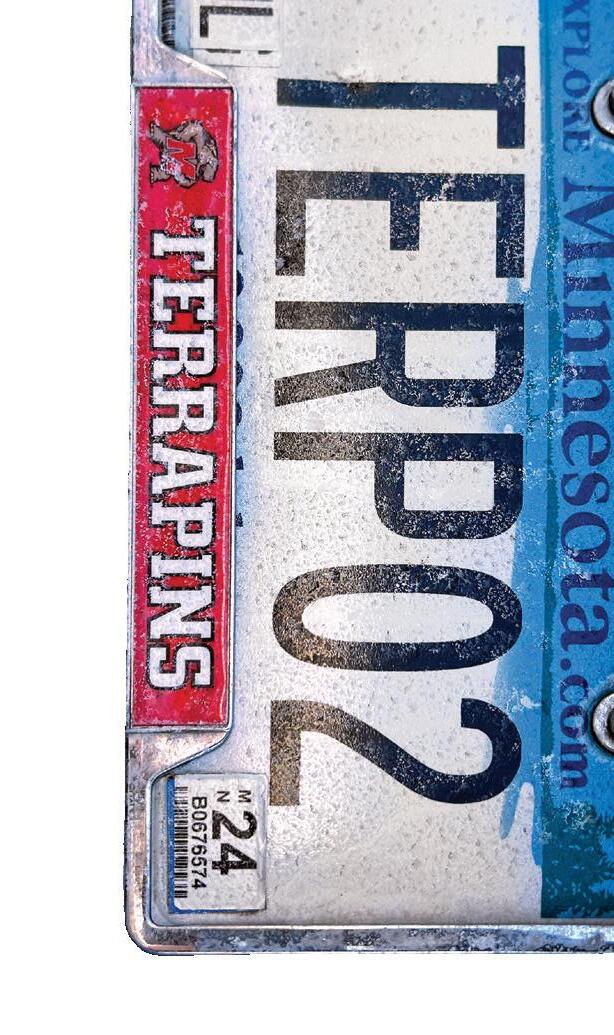

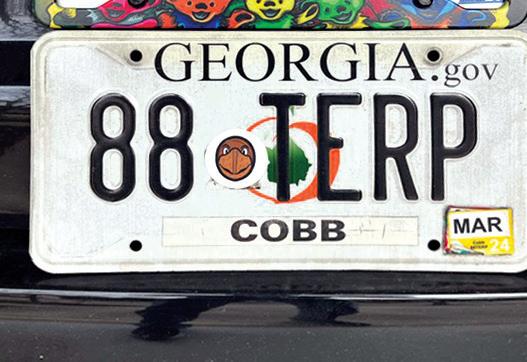

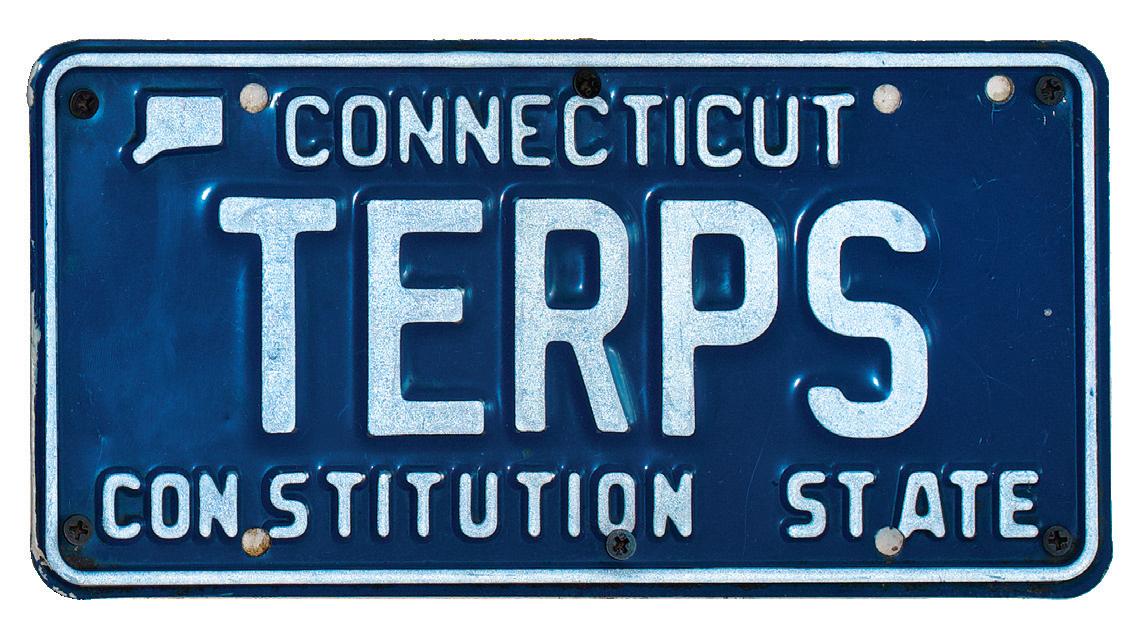

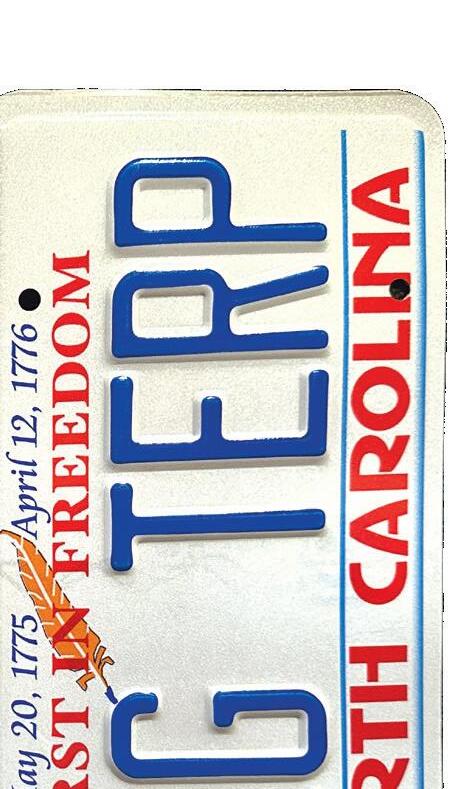

UMD-themed vanity plates are the highway fourleaf clovers we love to spot. We share some of the best—and the tales behind the tags.

BY MAGGIE HASLAMCONSIDER THE THRILLING roadway rush of spying a UMD-themed license plate amid the slog of a hellish Beltway commute or bumperto-bumper beach traffic.

Now, imagine the feeling of finding one 2,700 miles from College Park that’s exactly like yours.

Lee Givens Jr. MBA ’05 was crossing the I-90 bridge in Seattle for a Mariners game in 2019 when he closed in on an SUV with Oregon plates that read “TERPS”—the same plates he had on his Washington State-registered Tesla Model Y.

“I quickly took a picture from my dash and then passed the driver and pulled in front of him,” recalls Givens. “His kid was in the passenger seat and started going crazy

when he saw my plates. I mean, what are the chances? It was just awesome.”

Givens is one of hundreds of alums who have emblazoned their Maryland pride on their ride, paying their home state from $20 to $80 annually to own University of Marylandthemed vanity plates: We found “B1G TERP” in North Carolina, “TERP 02” in Minnesota, “TERPFAN” in Pennsylvania and “TERP 72” in Arizona. Some alums go the extra step of ordering UMD-branded plates or frames or sport Maryland-red paint jobs.

In Givens’ case, he tried roughly 40 letter/ number combinations while living in Maryland to no avail, finally nabbing the prized “TERPS” after taking a job in Seattle in 2011. He practically sprinted to the Department

of Motor Vehicles to fill out an application as soon as he arrived in town. “I think I did it before I bought my first groceries.”

While UMD-themed plates are prolific in the DMV, as miles from College Park accumulate, so does the confusion. “What the hell is a Terp?” has been uttered by rangers in Yosemite and confused with a love of cannabis on the West Coast. But UMD-themed plates have also elicited honks, fist pumps and an occasional friendly tackle in the grocery store parking lot. (These usually involve sports fans.)

Terp magazine scoured the country’s highways, driveways and parking bays for UMD-themed vanity tags and the proud alums behind them. Buckle up for their origin stories, roadside run-ins and looks that stop traffic.

The next time you’re walking into the Xfinity Center for a Maryland basketball game, there’s a good chance you’ll see Diane and John Alahouzos’ GOTERPS plates right out front. A former Terrapin Club president and member of University of Maryland College Park Foundation board of trustees, Alahouzos ’71 helped designate the coveted parking spaces steps from Xfinity’s main entrance for UMD’s most ardent backers. He remembers driving through Duke University’s campus with the plates in 2004 after UMD won the ACC tournament. “It was a half-hour detour, but it was worth it,” he says.

While Fabian ’89 and Eleanor Jimenez celebrate their all-Terp family (including kids Andrew ’15 and Chris ’23) with ALLTERP on one car, they also snagged the OG OC TERP. They’re not the only Ocean City Terps: Joe ’82 and Mary Wiedorfer M.S. ’95 registered for OCTRP2 and OCTERP3 when they moved three years ago from Washington, D.C. (Joe owned the coveted DC TERP there.) “We really wanted OC TERP,” says Wiedorfer, “but it was taken.” Joe, meet Fabian!

“I moved (to North Carolina) in 1989 and had to wait years for someone to give up TERPS. I checked each year, and then sometime in the ’90s it was available. I always say someone had to die before I could get that.

When bioengineering major Scott Regan ’26 was selected to join the Mighty Sound of Maryland, his parents surprised the tuba and sousaphone player with personalized license plates: TERP2BA. “Most of the band parents and students get it,” says his mother, Tiffany. “But a lot of other people have asked if someone got two (bachelor’s) degrees.”

Despite the distance from College Park to the Phoenix suburbs, strangers stop Rodney Adelman ’72 in parking lots and wave to him on the road when they spot TERP 72. When a mechanic recently asked him what the plates mean, he responded,

“Are

you a college sports fan? Well, let me tell you about

Diehard Terps basketball fan Amelia Todaro ’08 bought a bright red car and has owned TERPUMD for about five years.

“I was so excited ‘TERPUMD’ was actually available.

One of my biggest pet peeves are plates that are so obscure no one else understands them!”

Most letter-number combinations that include UMD or TERP have been exhausted in Maryland, with alums swap “S” with “5” or “E” for “3” to score their coveted configuration. If you’re yearning to add a little brag to your bumper, the following tags are still available through the Maryland Motor Vehicle Administration:

UMD4ME

UMD4EVA

TEST2DO

UMDGRAD

UMDFAM

N01TERP

TERPDAD

UMD CP ILVUMD HONK4UM

TERPN01

GOUMDGO

UMDALUM

Maryland residents can also show their Terp pride with a UMD-branded license plate, available through the Alumni Association for a $15 donation. Visit go.umd.edu/mdlicense.

If Sanjay Tolani ’94, MBA ’01 ever chose a life of crime, he’d never be allowed to drive the getaway car. Tolani is known to friends, family—even strangers on the street—as TERP MAN, the yin to his wife Anita’s yang. (A Berkeley grad, she’s CAL GAL.) “People will say, Hey! I saw you at the airport!

‘Hey! I saw you at the airport!’

I’ve had them for so long, everyone knows it’s me,” he laughs. He once found a note left on his windshield about the 1953 football championship and frequently gets honks on the road. “Sometimes if I’m driving my wife’s car, I’ll get a honk; and then they pull up next to me and start laughing when they see a man behind the wheel.”

When Mike Wall ’82 and wife Louise ’79 got their first car together, they celebrated their love—and UMD—with custom plates. “You had to submit by mail back then,” says Wall. “I remember I put 2TERPS as my first choice and PROTERPS for my second, because I was going for ‘pair of Terps.’ And that’s the one that was accepted. But a lot of people just think it’s ‘Pro Terps.’” Wall’s more recent plates for his truck, which say FRDTRTL, conjure just as much confusion. “If I see people behind me in traffic pointing and trying to figure it out, I’ll point to the big Maryland decal on my back window. Some people think it stands for ‘Ford,’ but I’m driving a Toyota; that makes no sense.”

Virginia began offering the University of Maryland-branded license plate during Stephanie Casway’s senior year at Maryland. She sat at her computer until midnight the night they were available to snag TERP07. (Her husband, Jason Harris ’05, now has TRPCPA.) After her first child was born in 2016, she went to a new moms’ group at a Northern Virginia church and realized she’d parked next to a car with the plates TERP06. It turned out to belong to one of Casway’s sorority sisters, Sandi Horton ’06, who she hadn’t seen in a decade, and later connected with on Facebook.

David Rothbard’s car already had the UMD-branded Virginia plate and Alumni Association lifetime member frame when the 1993 grad splurged on a vanity plate. He couldn’t fit TESTUDO because of the turtle-branded plate—and “TERP” in all forms was taken. A former journalism major and avid Diamondback reader, he settled on DBACK1. Rothbard often gets the question “What’s a DBACK?” and is sometimes confused with an Arizona Diamondbacks fan. It took a visit to the University of Virginia for someone to recognize it—sort of. “This guy rolls up in a car completely decked out in UVA stuff, and he rolls down his window and says,

‘Hey! Maryland Diamondbacks!’”

Amy ’96 and Scott Beatty ’95 never had vanity plates while in Maryland, but after they moved to Memphis, Tenn., realized they might have better luck. Amy got the coveted TERP while her husband got TERP4LIF. Each time the state updated its plate design, the couple kept the old ones, even repurposing a few into birdhouses (above). “Not many people down here know what a Terp is, and I frequently get questions like, ‘Why does your license plate say Twerp?’”

When TERP is taken, sometimes you have to get creative—and do a lot of explaining:

Tom ’90, M.A. ’96 and Kathy Gray have been representing UMD with MD TERP vanity plates for 15 years, first in Des Moines, Iowa, and now in Charlotte, N.C. In addition to honks and waves from other alums, Gray says the most common reaction is,

“What’s a Doctor Terp?”

“It’s fun to get a honk now and then when someone sees my plate and knows what it means,” she says. “I even had one woman get out of her car in the CVS pharmacy drive-thru, knock on my window and tell me how much she loved my plate because she and her husband were both Maryland grads. It made my day!”

Noreen Welch ’90 was sitting in bumper-to-bumper traffic on University Boulevard en route to a Maryland basketball game with friends Sander Zaben ’85 and Jay Sivulich ’85 when they spotted the Maryland license plate WILLWIN. The insider reference to the final line of the “Maryland Victory Song” was brilliant, they agreed. She and Sivulich went home that night and immediately registered for W1LLWIN and WILLW1N, respectively.

WESTWARD-BOUND PIONEERS of an earlier era packed their wagons, hitched up the oxen and set out. Before his own trailblazing crosscountry journey, Mark Eakin first tested his wheels at a D.C.-area drag strip.

There, his Ford F-150 Lightning—a battery-powered version of America’s most popular vehicle—posted acceleration times that would rival a Ferrari’s, while emitting no greenhouse gases. The “frunk,” however, is Conestoga-esque in the storage gained from ditching the traditional internal combustion engine.

His new truck seemed the perfect vehicle to help Eakin, a retired coral reef scientist for the federal government and occasional University of Maryland research collaborator, forge a new Oregon Trail of climate-friendly travel. In early 2023, he and his wife, June, became the first people—as far as anyone in the electric vehicle enthusiast community can tell, anyway—to pull a travel trailer coast to coast and back with an EV

fast-charging stations about every 110 miles. Those breaks became all-day affairs in remote areas like rural Idaho and the Texas plains with scarce charging infrastructure, where the truck had to sip electrons from regular outlets.

None of this surprised the couple, who planned on short hops between friends, family and sightseeing. “It was a bit of an experiment,” Eakin says. “The idea wasn’t to get anywhere as fast as possible.”

Beyond committed environmentalists and hardy early adopters, the rest of the nation may be less tolerant of battery-related EV inconveniences. At least that’s the fear of government agencies and nonprofits behind a sweeping plan to “decarbonize” the U.S. economy to save the planet from global warming—and it’s why UMD researchers are at the forefront of developing EVs that can charge faster than you can fill a gas tank, have the range to cruise to the horizon and beyond without a stop, and boast unprecedented safety and performance in even the most extreme conditions.

NINETY-SECOND BATTERY FILL-UPS. ALL-DAY RANGE. UNPARALLELED SAFETY. UMD RESEARCHERS ARE POWERING UP EVS TO SAVE THE PLANET. An estimated EVs will be on the roads

Make that the almost-perfect vehicle. The trailer’s weight and wind drag shrank the truck’s range, requiring half-hour stops at

The clock is ticking. Limiting U.S. greenhouse gas emissions

200M 200M

to head off the worst effects of climate change means getting as many butts in electric vehicle seats as possible and moving to a power grid based on renewable energy sources, including wind, solar and hydrogen fuel.

“We have to accelerate the societal shift to electric vehicles,” says Distinguished

University Professor Eric Wachsman, a globally recognized expert in next-gen battery technologies and director of the Maryland Energy Innovation Institute.

“And that means you have to overcome the resistance some people have to these kinds of vehicles.”

EVs in 2023 accounted for 7.6% of the U.S. new vehicle market, up from 5.9% in 2022, but beyond the coasts and big cities, the lure of swoopy Teslas, burly Rivian trucks and an increasing selection of cars from traditional manufacturers is in question.

more 17% more

early 2024, new EVs cost than the average car.

For instance, a January 2024 Deloitte survey of 27,000 global consumers showed concerns about charging speeds and vehicle range were causing people to avoid EV purchases. At almost the same time, Ford slashed F-150 Lightning production by two-thirds, citing weak demand, while other manufacturers also retrenched with plans to sell fewer EVs and more traditional vehicles.

What’s needed, say UMD researchers, is a self-perpetuating virtuous circle where every advance expands the user base, leading to greater support and infrastructure, and making EVs appealing to ever-broader swaths of society. That will include marginalized and low-income groups who bear much of the brunt of pollutants from conventional vehicles, and who are most vulnerable to climate-related harm as fossil fuel use continues to heat up the earth.

Beyond the upper-income groups that make up most of the EV market today, switching to an EV in 2024 is a tall, if not impossible, order, contributing to growing tech disparities and hampering society’s ability to head off environmental catastrophe.

“We shouldn’t be naïve about how hard it is for people from disadvantaged groups to enter these kinds of markets,” says Deb Niemeier, Clark Distinguished Chair in the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering (who is not part of the A. James Clark School of Engineering’s battery design efforts). “First and foremost, you have to have affordability and there has to be a viable used car market, and public charging must be available in places where it barely exists now.”

To address such challenges, UMD battery researchers are among the most active in the nation working to meet the performance requirements of the EVs4ALL program overseen by the Advanced Research Projects Agency-Energy

(ARPA-E), a federal agency that deals in cutting-edge energy projects. To those ends, Wachsman and others plan to bring batteries to market in coming years that last through many thousands of charge cycles, enabling used car markets; batteries that use cheaper, more readily available components than traditional ones like lithium; batteries that charge up in minutes rather than hours, even in low temperatures that stymie current technology.

“At UMD we have a large number of faculty and students on these projects compared with other academic institutions,” says Paul Albertus, an assistant professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering who in his previous job was the program manager for over $60 million of mostly battery projects for ARPA-E. “What really sets us apart is that we have research groups working on so many of these different aspects—solid electrolytes, liquid electrolytes, people doing basic science and people doing technological innovation—and that portfolio of work is complementary.”

Current lithium rechargeables have fueled technological leaps in mobile computing, medical devices and e-bikes and -scooters; they’re tucked into an ever-increasing number of our cars and light trucks—from an International Energy Agency figure of around 26 million EVs globally in 2022 to recent Bloomberg forecasts of 77 million next year. More than 200 million electric vehicles are expected to be on the road worldwide by the end of the decade—but powered by what?

As anyone knows who’s seen surveillance videos of exploding scooters and terrorized vape

We have to accelerate the societal shift to electric vehicles.”

—ERIC

WACHSMAN DIRECTOR, MARYLAND ENERGY INNOVATION INSTITUTE; DISTINGUISHED UNIVERSITY PROFESSOR, DEPARTMENTS OF CHEMICAL AND BIOMOLECULAR ENGINEERING AND MATERIALS SCIENCE AND ENGINEERING

pen users dropping and fleeing their devices, or discovered their phone bulging and nonfunctional with a swollen battery, lithium-ion cells have a dark side that stems from their chemistry. They use a flammable liquid electrolyte, the part of the battery that carries electric current between the positively and negatively charged internal components of cells, made of lithium salts dissolved in an organic solvent.

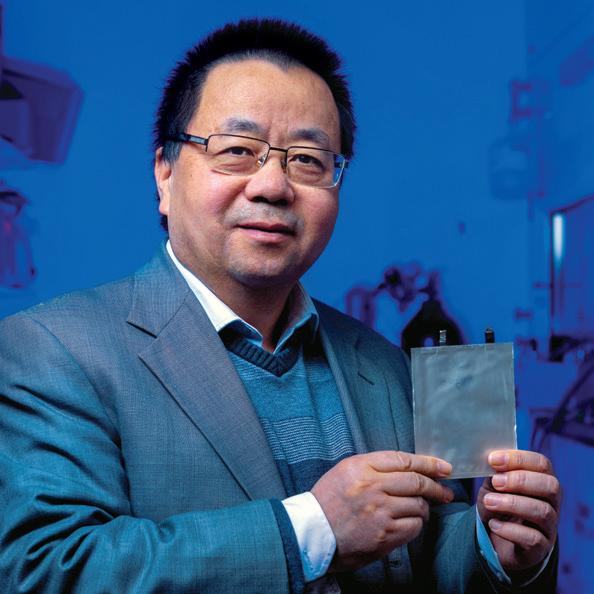

“Liquid lithium electrolytes are very volatile. If you have a short or damage to the battery, you can have what’s called a thermal runaway reaction where the battery’s energy heats up the battery uncontrollably and can start a fire,” says Professor Chunsheng Wang, director of UMD’s Center for Research in Extreme Batteries—a collaboration with the U.S. Army Research Lab—and like Wachsman (left), a faculty member in chemical and biomolecular engineering as well as in materials science and engineering.

(For perspective, EVs don’t burn often, although they get a lot of press when they do. “They’re very safe, safer than a typical car, in fact,” says Ron Kaltenbaugh, president of the Electric Vehicle Association of Greater Washington. His claim echoes recent data from both Tesla and an Australian government study showing that EV batteries, frequently bundles of hundreds of smaller battery cells, are an order of magnitude less likely to ignite than petroleum-powered engines.

“But they can be pretty hard to put out” once fully engulfed, Kaltenbaugh says.)

Managing conventional lithium-ion batteries’ safety issues comes at a heavy cost—literally. Their various added layers and separators, along with extra circuitry and other protection measures on the outside, make current EV battery systems far bulkier and less “energy-dense” than they would be with inherently safer chemistry.

“Every layer of material you add to the battery is that much less energy the battery can hold,” Wachsman says.

According to ARPA-E, the current generation of lithium-ion batteries suffers from “performance limitations that incremental progress cannot address,” hampering a full transition away from the 1.7 billion conventional light vehicles on the road globally, along with a similar number of heavy trucks, buses and the like.

A new path lies in solid-state battery technology. It replaces lithium-ion batteries’ problematic liquid electrolytes with safer, nonflammable alternatives. This is at the heart of research in the Maryland Energy Innovation Institute, which in recent years has helped launch dozens of companies, filed for well over 100 patents and secured around $150 million in funding for the startups, several of which focus on technology directly applicable to vehicles.

Wachsman’s solid-state design replaces the liquid electrolyte with a rigid ceramic known as garnet that conducts ions about as well as a conventional lithium-ion electrolyte, while being nonflammable and tough enough to endure thousands of charges. The technology is being developed by Wachsman’s spinoff company, Ion Storage Systems, with the help of recent $40 million investment rounds.

As the Eakins wended their way across the country, the frequent stops for fast charging along major interstates weren’t what bothered them. “People talk about the 400-mile battery—who’s got a 400mile bladder?” Mark Eakin says.

The lack of charging spots in the nation’s interior was what made it impractical to visit the house in the Texas Panhandle where Mark’s grandparents had lived; the Eakins also had to carefully manage their approach to Big Bend National Park in the western end of the state to avail themselves of the few available charging opportunities and driving slower than normal to extend their range along certain stretches of interstate.

Issues of vehicle range, charging rates and infrastructure are interrelated; one way to incentivize building more charging infrastructure is to make more people want—and buy—electric cars by addressing the issues in a holistic manner rather than individually. UMD’s battery experts plan to do that in part by rendering obsolete one of the loudest complaints against EVs: They take too long to charge.

While “slow” is relative, so-called Level 1 charging with regular outlets is painfully poky, adding less than five miles of driving range for every hour plugged in. Level 2, available at around 54,000 public charging stations in the U.S. and at many EV drivers’ homes, uses 240-volt power to add 20 or more miles of range an hour. Level 3, known as DC fast charging, or “Supercharging” in the Tesla universe, can boost a car’s battery to 80% in 20 minutes to an hour. The catch? Only about 9,400 such charging stations exist in the United States, according to research by UMD’s Center for Global Sustainability (CGS), and per mile they rival gasoline in cost, negating one of the draws of EVs.

That scarcity leaves vast swaths of the population without a practical way to drive an EV, contributing to sluggish sales even as average prices have been plummeting. CGS’s work found that access to charging is far from equal in U.S. society, with members of racial and ethnic minority groups and low-income people on average traveling farther to find an EV charger, says Jiehong Lou, a CGS assistant research professor who studies equitable access to EV technology. Likewise, African Americans have less potential to reap the cost savings of home charging because of significantly lower

homeownership rates than white people, she says.

To be broadly popular, EVs can’t require a hobbyist level of commitment and a spacious suburban home, Wachsman says.

“Someone like me can drive home at night, close the garage door when it’s cold outside (because EVs don’t charge well in the cold), plug into a Level 2 charger, and you’re ready to drive the next day,” says Wachsman, who’s driven a Tesla since 2013. “But there are a lot of people who live in apartments, live in a city environment, who just don’t have home charging. Then it gets a lot harder to drive an EV.”

Today’s half-hour fast charging sessions offer drivers a chance to play a few rounds of Candy Crush and read emails, welcome or not. In the future, they’ll race to squeegee their windshield before the charge is finished.

In recent work, Wachsman showed that by modifying the composition of his patented ceramic architecture, he could charge or discharge lithium metal batteries at rates up to 100 milliamperes per cubic centimeter, enabling EV battery charging in about 90 seconds and exceeding the U.S. Department of Energy’s fast-charging goal for EVs by a factor of 10. The new approach would also result in batteries with a lifespan far longer than typical cars need.

Meanwhile, Wang and colleagues showed a way to stop “dendrites,” tiny branch-like structures that grow in the microscopic confines of an advanced

It’s a matter of whether the priceto-performance ratio works for you. If it does, you get an EV.”

—RON

solid-state cell during fast charging and other intense usage, causing short circuits. A new interlayer in the battery can stop lithium dendrites that develop in the battery’s negative electrode, piercing the solid electrolyte and destroying the battery.

Wang (right) also presented battery technology recently that overcomes another major hurdle for lithium-ion batteries: rapidly declining efficiency and chargeability as the temperature gets closer to the freezing point. In 2023, he demonstrated a battery that operates down to minus 60 degrees Celsius. He’s commercializing the technology through his battery spinoff company, Wh-Power.

In research not directly related to EVs, Wang has produced batteries that use saltwater as an electrolyte and with previously unheard-of voltage levels; he’s working to boost the energy a bit higher to create batteries that are intrinsically safe and cheap—“just go get some water from the ocean,” he jokes—that can be used to store excess wind or solar energy generated on a renewable power grid. Such batteries could provide carbon-free vehicle charging in the most remote locations.

UMD engineers and chemists are working on a wide range of other battery technology as well that could one day power electric vehicles and other technology of the future. Some focus on finding “earth-abundant” replacements for lithium, which is toxic, relatively rare and vulnerable to supply line delays caused by geopolitical disruptions. Another line of research, led by Distinguished University Professor Gary Rubloff in materials science and engineering, uses nanotechnology to precisely design microbatteries with huge power output for their size; they could be constructed much like microprocessors on outdated assembly lines for silicon chips.

“The more of these problems we solve, the more electric vehicles people will be driving, and the better for the environment,” Wang says.

On a back road near Frederick, Md., Kaltenbaugh, head of the D.C. EV owners’ network, presses the accelerator on his Tesla Model 3; the dual motors kick in almost silently, squishing a passenger back into his seat as barns and a farm animal or two fly by.

“We’re still in ‘Chill’ mode,” he points out, indicating the possibility of several higher levels of squish. Although Kaltenbaugh says he rarely tests the car’s performance potential, the acceleration has at least once helped him avoid a potential collision with an erratic driver while he was merging onto a highway.

A massive dashboard screen displays miles remaining on his battery—about 170—and when Kaltenbaugh pulls over, he activates a map showing every available charger in the region. It looks like a cornucopia, but the density of options thins toward the edges.

“Electric vehicle technology is never going to ‘get there’ if that means a stage where it’s fully developed,” says Kaltenbaugh, whose family has transitioned entirely to battery-powered cars. An avid skier, he’s seen the impact of climate change in mountain environments around the country, where subtle temperature changes can have outsize impacts on snowpacks.

“It’s going to keep developing. It’s a matter of whether the price-to-performance ratio works for you. If it does, you get an EV.”

For those who can afford a new car now and have a place to charge it, EVs’ efficiency and performance advantages combined with lower regular maintenance requirements already make them a logical choice over fossil fuel-powered vehicles, says Wachsman. With their revolutionary battery advances, Maryland researchers plan to soon push it over the hump for everyone else.—terp

The more of these problems we solve, the more electric vehicles people will be driving, and the better for the environment.”

—CHUNSHENG WANG

DIRECTOR, CENTER FOR RESEARCH IN EXTREME BATTERIES; PROFESSOR, DEPARTMENTS OF CHEMICAL AND BIOMOLECULAR ENGINEERING AND MATERIALS SCIENCE AND ENGINEERING

sometimes wonders what his life would look like if he’d been born with a different last name. Would he have devoted his personal and professional ambitions to the wide world of whimsy as a Jones or a Smith? Which came first—the name, or the yearning for an off-kilter existence?

Either way, Looney’s fate was sealed during the summer of 1986 when he met a “hippie chick who doesn’t wear shoes” named Kristin Wunderlich ’88 working at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center. Her path was preordained as well: In German, “Wunderlich” means eccentric, odd, quirky.

Together, Looney and Wunderlich—long since married and jointly the Looneys—have lived up to the promise of their names.

They are the chief creative officer and CEO, respectively, of Looney Labs, the game company behind the card game Fluxx, which has sold more than 4 million copies since its 1997 introduction and spawned spinoffs like Around the World Fluxx, Monster Fluxx and Nature Fluxx.

The game is simple, in theory: Each player starts with three cards and on each turn, draws one and plays one. The game is formless until some cards are played, setting objectives and rules. Each card played reshapes the game. Some introduce a new rule, like “play three” or “draw two.” Others set a new goal that changes the object of the game.

“What got me was the twist, which is there are no rules until you play (a card

with) rules, and there’s no way to win until you play a way to win,” says Mike Webb, vice president of sales and e-commerce at game publisher Paizo, who first met the Looneys in the late 1990s while at a different company that distributed Fluxx. “That was just utter genius, and it’s something that made the game have instant appeal to folks.”

Fluxx, Looney Labs’ biggest hit, isn’t Risk, or Magic: The Gathering or Dungeons & Dragons. It doesn’t require players to dedicate hours, or learn an intricate set of rules, or create a backstory for their characters. The game can take as little as 10 minutes, and its strategies are limited.

“One of the most basic breakdowns I like to use (to describe the spectrum of games) is what I call zany or brainy,” says Andy. “Fluxx is very chaotic. So that represents the zany side of gaming.”

Draw some cards, and hop on the Looneys’ zany ride.

Knock on the door of the lilac-colored house off Rhode Island Avenue in College Park, and Andy Looney might answer the door barefoot,

wearing a purple robe, gray hair tied in a long ponytail: one part Gandalf, one part The Dude from “The Big Lebowski,” and one part cleaned-up Jerry Garcia.

Nicknamed Wunderland as a play on Kristin’s maiden name, the house is the de facto headquarters of Looney Labs. (The Looneys rent office space nearby, but since the pandemic rarely use it for more than storage.) To an outsider, the home might look like the warren of a Settlers of Catanloving packrat—seemingly every inch of it not crucial to functions like walking or cooking is crammed with board games, books, arcade games, collectible figurines. “He does know where everything is,” says Kristin.

Kristin has her own signature look: a tiedyed bandanna covering her hairline, wavy brown hair tumbling down her back, a tiedyed shirt doubling down on the vibe.

She’s the warm, focused extrovert to Andy’s sharp, roving-brained introvert. When he thinks of a book that they studied in their early days of game creation (“Gameplan: The Game Inventor’s Handbook”), he wanders off to find the paperback on the packed shelves. Kristin continues the story they’d been telling, happily pausing when Andy comes back to show the exact chapter he was referring to.

“Andy is a person who has wild ideas, and Kristin is a person who can figure out how to make them real,” says Keith Baker, a friend who first met Andy at science fiction

conventions in the 1980s. “She’s very whimsical and funny, but she balances that with an amazing sense of how to solve problems and get things done.”

Andy was studying computer science at UMD when he accepted a summer job at Goddard, in Greenbelt. The facility was familiar to him; his father was one of the original 157 scientists who transferred from the Naval Research Laboratory to open it in 1959. The family lived off Adelphi Road, near the campus, and games like Sorry! were a central part of life for Andy and his four siblings. “My mom loved

getting the kids to play games because they were entertained and she could play with minimal attention,” says Andy.

Kristin had grown up in DeKalb, Ill., 60 miles northwest of Chicago, where she’d been “obsessed” with the game Cosmic Wimpout. (The cloth on which the dice game is played hangs in the dining room of Wunderland.)

Kristin loved the game so much that she joined the mailing list of the “tiny little company” that made it, she says—and found out, years later, that Andy had done the same.

After Kristin’s parents got jobs at the National Security Agency, the family moved to Maryland, and Kristin transferred to UMD after two years of studying computer science at the University of Illinois.

Andy was interviewing for a full-time job at Goddard when his future boss talked up a summer employee who was an expert at the Rubik’s Cube—Kristin. Andy realized that he’d seen her on television five years earlier,

on an episode of “That’s Incredible!,” an early ’80s reality show that highlighted people’s unusual talents. At the time, she was the fifthranked Rubik’s Cubist in the nation, and Andy remembered “the cute blonde girl among the other eight guys” on the show.

Kristin and Andy became friends, and three years later, a couple. In September, they’ll mark their 34th wedding anniversary.

“The moment you meet them, you know there’s something special,” says Webb. “They’re so full of joy, it can’t help but be contagious.”