* Image on cover from David Garcia-Galiano (Elias lab) related to the study published in Journal of Neuroscience, 2020 (PMID: 33158965). It shows colocalization of Kiss1 (yellow), Ghrh (green) and Esr1 (red) genes in the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus. Blue = DAPI counterstaining.

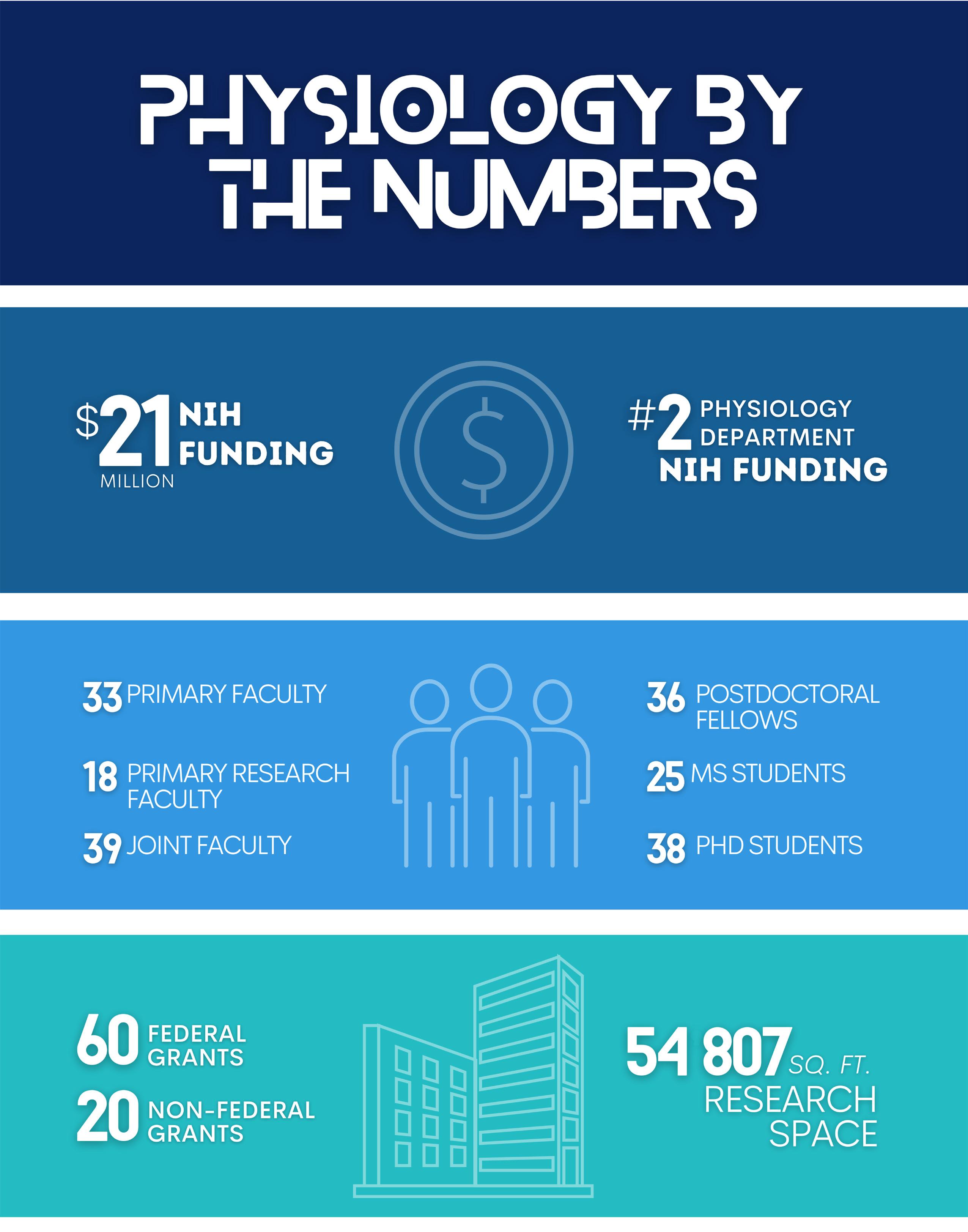

Romance in Science 06 CONTENTS Community Collaborations 10 Alumni Q & A 12 Mechanical Engineer Turned Physiologist 14 Elizabeth Weiser Caswell Diabetes Institute 16 Perspectives on the Graduate School Journey 20 PhD Graduates 23 Mentoring Undergraduates to Success & Beyond 24 The Extraordinary Achievements of John Faulkner 26 Embracing the Journey, Not Just the Destination 18 From The Chair 04 Physiology By The Numbers 05 Life After Football: MS in Physiology 08 Building Diversity & Inclusion in Physiology 22

Partners in Life, Partners in Science 07 2 Physiology Matters

Meet The Editors

Becky Schill is a 4th year post-doctoral fellow in the laboratory of Dr. Ormond MacDougald. Becky’s research is focused on the disease Familial Partial Lipodystrophy Type 2 (FPLD2), which is caused by mutations in the gene LMNA. Using a combination of mouse models and human patient samples, Becky is working to better understand how mutations in LMNA alter the adipose tissue transcriptome with the goal of determining the cause of adipocyte loss in FPLD2. Outside the lab, Becky enjoys baking, gardening and spending time with her 2-year-old son, Jake.

Hannah Thompson is a 1st year graduate student in Molecular and Integrative Physiology that is currently rotating. Her research interests include metabolism, mitochondrial biology and electrophysiology. Hannah received her degree in Chemistry and Human Physiology from the University of Minnesota Twin Cities in 2020. Outside of her academic interests, she enjoys teaching and outreach, painting and enjoying game nights with her friends.

Jess Maung is a second year PhD candidate in the lab of Dr. Ormond MacDougald. She is currently studying the rare disease lipodystrophy in which patients lose their adipose tissue (AKA fat). She aims to understand the mechanism of why and how this adipose tissue loss happens. Outside of the lab, she enjoys playing tennis, baking bread, trying new restaurants, and camping.

Edith Jones Kiyabu is a PhD candidate in the laboratory of Dr. Daniel Beard and Dr. Brian Carlson, she studies matters of the heart: cardiovascular metabolism and hemodynamics, using biochemical and computational modeling approaches. Outside of the lab, she enjoys baking with her husband and friends, watching period dramas and dreams of mini farming (if she ever owns a single chicken, she will think herself a very accomplished farmer!).

Irina Zhang is a second-year postdoc fellow in the laboratory of Dr. Leslie Satin. Her research interest is investigating the role of ER stress in pancreatic beta cells. Outside the lab, She enjoys baking, running and reading.

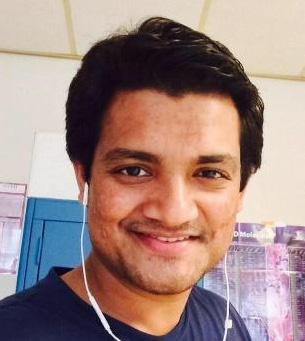

Sumeet Solanki is a postdoctoral research fellow in Dr. Yatrik Shah’s lab. He is working on nutrient sensing mechanisms in colon cancer, with the aim of using dietary interventions as adjuvant therapy in colon cancer. He like to play guitar and watch space documentaries in his spare time.

Sarah Lawson has been working in the department of Molecular & Integrative Physiology for 17 years, in an Administrative Assistant position. In her time outside of work, Sarah enjoys volunteering within her community, spending time with family and running to and from various activities with her daughters, Olivia and Emily.

3 Physiology Matters

From The Chair

Colleagues, Alumni and Friends,

Sometimes plans change.

After stepping down as MIP graduate program director at the end of 2020, I was looking forward to spending some time focusing on my research laboratory, my ongoing educational and research work in the Frankel Cardiovascular Center, and maybe a little more time to spend with family and on the soccer field. As most of you know, in August of 2021 our recently appointed chair, Dr. Santiago Schnell was recruited to become the Dean of the College of Science at the University of Notre Dame. Someone must have put my name forward, and within a few short weeks on September 1st, I became the department’s interim chair.

As a new chair, I feel very fortunate to work with dedicated staff, ambitious (and forgiving) colleagues, and wonderful postdocs and students that continue to make the department an awesome place to do science, a supportive place to learn and launch a career, and overall, a warm and friendly community that makes MIP a rewarding place to work. Fortunately, Santiago led the department through a very challenging time during the pandemic and left the department in great shape for the next interim chair. As we begin to emerge from the pandemic, our research is ramping up, our science is making an impact, and it has been wonderful to begin to meet back in person to share our discoveries, participate in classroom discussions, and see each other’s faces without masks.

In this year’s Physiology Matters, our editorial team of students and postdoctoral fellows have crafted some wonderful stories highlighting the people, research, events, and activities within our department over the last year. We hope these stories will help remind you of your experiences in MIP and how our scientific and educational efforts in the department often intersect with our lives and community beyond the walls of our research buildings. Our research is impacting health and disease, our students and postdocs are acquiring training to go out and become the next generation of leaders, and our service to the community continues to foster the next generation of scientists to be more diverse and inclusive than ever. One of the most exciting roles as a chair is to help lead the recruitment of new individuals to the department and welcome new members to our MIP community. Recruiting through our undergraduate programs, our student and postdoc programs and now recruiting faculty members brings me great joy to be able to open our doors to all MIP has to offer.

Having seen in more detail the generous contributions of time and resources that so many of you have given to help build the departments research and programs into what they are now, I really need to say on behalf of all the past and present MIP family, thank you! If you are looking for an opportunity to contribute to the ongoing research and programs in our department, please see the last page for a list of some of our philanthropic funds that our supporting programs in MIP. I particularly want to highlight and seek your consideration of a gift to our MS program fund. The MS program is an important steppingstone for many students to launch a career in medicine or research, and we are working very hard to try to make the program more accessible to students with financial need.

Sometimes plans do change. Sometimes unexpected changes end up being more delightful than what you were expecting. I am delighted to have the opportunity serve as interim chair and look forward to what the next years will bring for MIP.

Daniel Michele

4 Physiology Matters

5 Physiology Matters

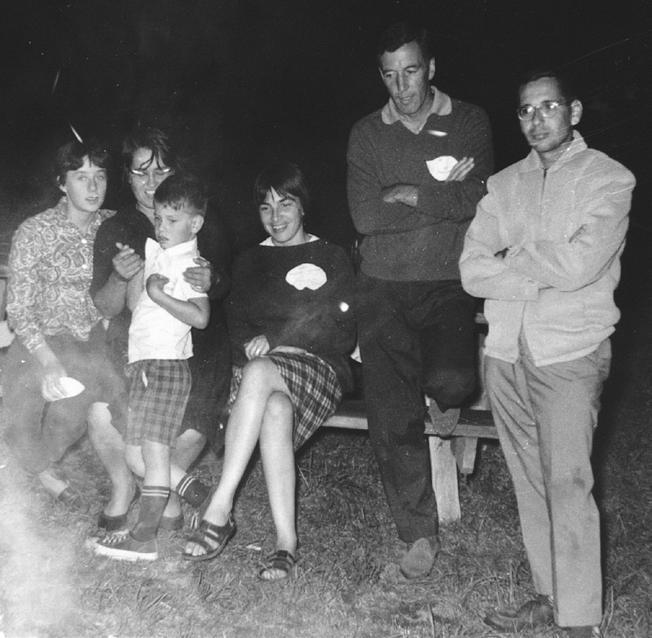

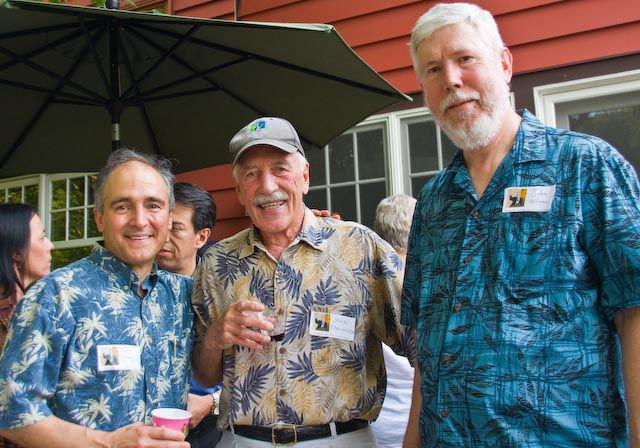

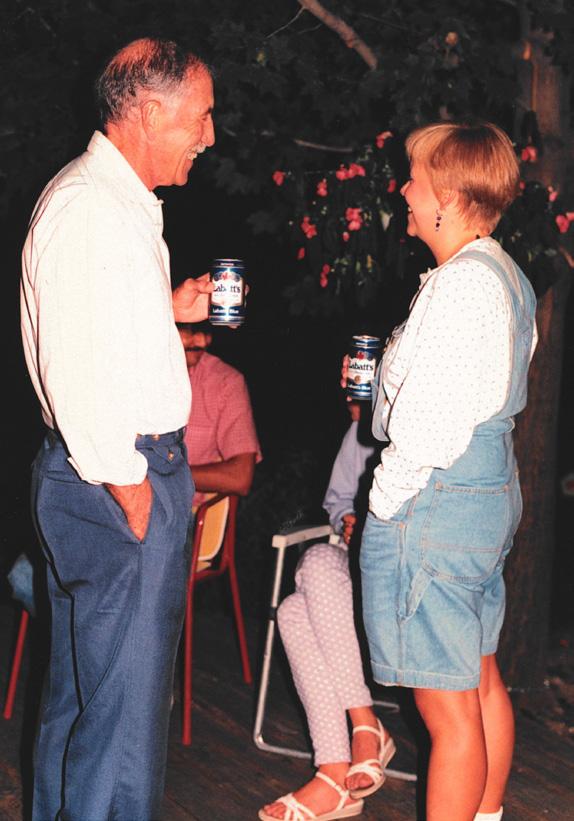

Speaking of science and scientific careers, one often neglected aspect could be addressed by this question—is there romance in science? The short answer is Absolutely Yes. I have always been inspired by the love stories of couples like Drs. Pierre and Marie Curie (the 1903 Nobel Prize winners for Physics), Drs. Irene Joliot-Curie and Frederic Joliot-Curie (the 1935 Nobel Prize winners for chemistry) and Drs. May-Britt and Edvard Moser (the 2014 Nobel Prize winners in Physiology). Then one question started to emerge in my mind: could marriage in science potentially be an unconventional secret to success? In our department, we also have married couples who greatly endeavor to influence physiology and medicine.

Dr. Mauricio Torres and Dr. Neha Shrestha are research investigators in the Ling Qi Lab at the University of Michigan, Molecular & Integrative Physiology. Dr. Torres obtained his Ph.D. in Biomedical Science from the University of Chile (Universidad de Chile) in 2011. Dr. Shrestha was originally from Nepal. She received her Ph.D. in Biochemistry from the National University of Singapore in 2015. Two biochemists, from the opposite side of the world, after decades of education, destiny finally made them join the Qi Lab at the same time, in September 2016.

After moving to Michigan, many challenges appeared, as they do for every other international scholar: complex paperwork, inconvenient grocery shopping, being far from one’s support network and familiar environment, coping with culture shock and homesickness. They quickly became friends and supported each other while overcoming these difficulties. They started to spend time during lunch breaks sharing their thoughts and feelings. That was the initial move towards their later romance.

Dr. Torres aims to uncover the role of endoplasmic

reticulum associated protein degradation (ERAD) in mechanisms associated with neurodegeneration and the pathogenesis as well as the progression of neurodegenerative diseases, such as Parkinson’s disease, Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) and Alzheimer’s disease. Dr. Shrestha is interested in investigating the role of endoplasmic reticulum protein quality control in pancreatic beta cells. Although their research interests do not seamlessly overlap, they help each other on various occasions, such as interpreting results from complex experiments, sharpening public speaking skills, mapping out future directions, and recovering from failures in experiments and unscored grant applications. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the challenge of making progress in their projects and the constant concern of catching the virus has put on additional stress, but they remain optimistic that the love for each other will take them through any harsh moments in life. At all times, they feel supported, encouraged and empowered in the personal relationship and at the workplace. They are each other’s safety nets, rain or shine.

Is there romance in science? “We think there is definitely romance in science. Sometimes it is difficult to find the time to surprise your partner when you are working in the same place or after a very busy day, but it is more about the small details to express our love for each other on a day-to-day basis that makes the difference. It’s only a fellow research partner who understands the frustrations and the passion for continuing research. Throughout the research career, both of us had our highs and lows, and we rode along these waves together lifting each other when needed. Only another scientist understands you have to go to the lab during the weekend and spend any spare time reading new research articles.“ said Drs. Torres and Shrestha. They clearly described Romance from a different perspective. They share the same goals and engage each other to accomplish everything they can in their professional life. Similarly, their relationship builds on careers; they enjoy the love and company of a person who truly understands the other personally and professionally. Such a tight connection makes their relationship get stronger and stronger every day.

As young scientists, they have made significant progress in their career paths, publishing scientific findings in highimpact journals like Science, The Journal of Clinical Investigation and Nature Communications. I envision them continuing to stand behind each other in times of need and making greater success in science and a more significant impact on society in the future. When that day comes, we hope they will again share with us the secret to success and the driving force behind endeavors.

Mauricio Torres, PhD Research Investigator, Molecular & Integrative Physiology

6 Physiology Matters

Neha Shrestha, PhD Research Investigator, Molecular & Integrative Physiology

Every day, Dr. Megan Killian and Dr. Adam Abraham have lunch together: it’s their moment of solace during action-packed days of running their own labs, which are collaborative and complementary. Outside of this hour of connection during the workday, you would otherwise never know that Drs. Killian and Abraham are married – their impressive professionalism helps their well-oiled academic machines run seamlessly.

Partners in Life, Partners in

Dr. Killian and Dr. Abraham started their journey through science together at Michigan Technological University: Dr. Killian was in the middle of her PhD program and Dr. Abraham was completing his master’s. Their first date was a 24-mile run: fitting for a couple who were in it for the long haul, ready to start the marathon of their careers together. Eventually, they ended up in the same PhD lab and overlapped for one year before they were physically separated by post-doctoral fellowships and lab relocations. Drs. Killian and Abraham were reunited two years later, only to find themselves a few hours away from each other for the next chapter: Dr. Abraham started a postdoctoral fellowship at Columbia University in New York City and Dr. Killian founded her independent lab in a tenure-track position at University of Delaware. A few more years of long distance later, the couple got an offer they couldn’t refuse from the University of Michigan. The move to Michigan came with lots of benefits: being closer to family, conquering the “two-body problem,” and supportive departments and faculty welcoming them warmly. Strong advocates and opportunity for growth at the University of Michigan within both the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery and Molecular & Integrative Physiology helped recruit and retain these strong scientists.

Dr. Killian is an Assistant Professor of Orthopaedic Surgery and Molecular & Integrative Physiology, and Dr. Abraham is a Research Investigator in the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery. They both head independent research programs but work in the same topic matter, investigating soft tissue orthopedics and tendons. Dr. Killian’s specialty is in tendon growth and development; Dr. Abraham’s in aging and inflammation in tendon biology. They have established their own unique scientific niches but contribute to each other’s successes, working as a co-led lab. This provides a rich training environment, a great exchange of ideas during group meetings, and efficiency when sharing equipment and resources. Clearly defined roles and a high degree of organization keeps all lab members on the same page when working in this collaborative environment, a direct consequence of the open communication between Drs. Killian and Abraham.

Working with one’s significant other is not always easy. Naturally, conflicts and questions arise, as with any partnership. Dr. Killian and Dr. Abraham make a conscious effort to work through any problems, being aware of potential overlap in their research fields, especially when trying to secure research funding. By being proactive, they lift each other up so they can both succeed individually and together. They practice patience and transparency in the workplace, which even translates to their home life. Even when cooking dinner together after work, Drs. Killian and Abraham continue their collaborative nature as they divide roles and conquer mealtime.

Science is often a rollercoaster: there are exciting highs, like being awarded a grant, and there are also low lows, like when experiments go wrong. Pre-pandemic, Drs. Killian and Abraham celebrated each other’s successes by trying new restaurants and cuisines; these days, they stay in and cook together. They pick each other up by doing something physically active like working out or running, or by staying in and watching the Great British Bake Off. Outside of the lab, Dr. Killian and Dr. Abraham love to run and train together, weight lift, and road bike. They love to go on backpacking and camping trips, connecting with nature and their home state of Michigan. Apart from each other, Dr. Killian loves to connect with friends all over the country on Zoom and Dr. Abraham connects with his community via video games.

As Dr. Killian and Dr. Abraham continue their independent academic and professional success, they know they always have each other to lean on. They get to be that person for each other: that person they get to share those late night wild scientific ideas with, that person who has an unspoken understanding of how the other is feeling, that person who just gets what a day in science is like.

7 Physiology Matters

Megan Killian, PhD Assistant Professor, Molecular & Integrative Physiology Adam Abraham, PhD Research Investigator, Orthopaedic Surgery

Life After Football: M.S. in Physiology

Andrew Vastardis, MS Graduate, Molecular & Integrative Physiology

8 Physiology Matters

Football has opened many doors in my life. It has given me the opportunity to pursue the finest education in the world, learn valuable life skills, and meet people who have helped me to positively impact the community around me.

After completing my senior season of football and upon entering the final semester of my undergraduate studies at Michigan, I was at a crossroads. Should I pursue the foreseen “life after football” many former players had told stories about or continue to chase the dream to leave my own mark and legacy at Michigan?. I chose the latter, which allowed me to better position myself for life after football, by pursuing a master’s degree.

When I started looking into graduate programs, the first one on my list was the M.S. in Physiology Program. I first became interested in physiology during my undergraduate Movement Science studies. Several of my core classes contained physiology components, but the required exercise physiology class really sparked my interest. I was just drawn to the overwhelming connection between physiology, exercise science, and playing football. When I reviewed the curriculum, it became clear the coursework would be very beneficial, as I set my sights on pursuing a career in medicine.

My parents and I reflected on the uncertainty I felt in the days after the University of Michigan sent students home, at the beginning of the pandemic. As an undergraduate senior, I had no idea how I was going to get through the next several months, let alone if I would be able to complete my application for graduate school. We remembered how my desire to understand COVID-19’s effect within the body further fueled my motivation to pursue a master’s degree in the Department of Molecular & Integrative Physiology.

I remember calling my parents when I was accepted to the M.S. in Physiology Program. I was filled with excitement and gratitude to be joining the 2020-2021 cohort, and my parents shared in my joy. To simply say that what I learned and experienced during my graduate studies was valuable and will help me in the future, would not be giving my time in the program enough praise. For me, it goes beyond the engaging curriculum, group projects, and capstone presentation. While what I learned has provided me with a strong foundation for a future in medicine, to me there was much more. Improving how I approached my learning, was equally, if not more, important to me. Early in the program, I felt like a fish out of water when it came to thinking critically whileen reading scientific literature, forming my own unique opinions, and effectively articulating my thoughts or impressions with confidence. This is when my University of Michigan football experiences really helped. As a walkon player whose career began as a blocking dummy for some of the best defensive lineman in America, I developed both a strong ability to persevere and an intrinsic desire for continuous improvement. I also utilized other skills that I acquired through football, which included managing time efficiently, organizing priorities effectively, and approach-

ing studies systematically. These skills greatly contributed to the successful completion of my Physiology coursework and building my confidence as an independent thinker and public speaker.

The new tangible skills I acquired during my graduate studies carried over to my football experiences, which similarly impacted my success in both Schembechler Hall and The Big House. Becoming more aware of bodily processes improved my football conditioning and recovery regimen, which led to my overwhelmingly healthy season. My passion to be a man made for others grew through classmate interactions during group projects. My ability to plan and deliver well-constructed presentations improved, and, with this, I became more confident in public speaking. I truly believe this all played a role in my becoming a better leader both on and off the field and, ultimately, being chosen as a Captain during the past two seasons, one of the greatest honors of my life.

Although the 2020 football season was filled with turbulence, difficulty, and disappointment, I was able to finish the academic school year on a high note. Completing the program-culminating capstone allowed me to showcase the knowledge and skills I had acquired, while pouring myself into a topic that has personally affected my family. Initially this assignment seemed to be a very daunting task. However, after receiving constant support from the faculty and making many revisions, the time arrived to present with confidence, and my goal was accomplished! Around this time, I was offered the opportunity to play a rare sixth year of college football. Ironically, this task mirrored how I had initially felt about the capstone assignment. Following a 2-win and 4-loss campaign in 2020, the season ahead seemed daunting…to say the least. However, my teammates and I put our heads down, did the necessary work needed – together, and became confident in ourselves and each other. We built on our successes, learned from our failures, and, when it came time to accomplish our goals, we moved forward with confidence. In the end, we achieved many of the goals we had set for ourselves, ending winless droughts, and accomplishing many firsts.

The last 18 months have been filled with countless challenges, many more important than football. Despite all the obstacles, Michigan’s Molecular and Integrative Physiology Department’s faculty found a way to deliver an exceptional program of studies. I am proud to say that the team I played for and the community I am a part of are strong, resilient, unified, and always working to improve ourselves and those around us.

9 Physiology Matters

Community

COLLABORATIONS

Standing in an open clearing, we watched as Bob Douglas, a retired Science teacher turned llama farmer, introduced us to our animal collaborator. “This is him. This is Moment,” Bob said as Moment of Victory stood grazing on the grass. We stood admiring the elegant sevenfoot-tall animal with a large neck and bulging eyes enjoy his surprise mid-day snack. The llama had a similar build to a miniature, furry giraffe. They are much larger in person than one may think.

Why were we, a UM assistant professor (Dr. Matthias Truttmann) and his graduate student (Nicholas Urban), standing in the middle of a llama farm on a hot summer day in Dexter, Michigan? We were leading an interdisciplinary and interdepartmental team to develop novel tools to help study a variety of important scientific questions. We were in the pursuit of developing nanobodies to help us study in unprecedented detail proteins involved in these diseases. But why did we need llamas?

Matthias Truttmann, PhD Assistant Professor, Molecular & Integrative Physiology and Nicholas Urban, PhD Candidate, Molecular & Integrative Physiology

10 Physiology Matters

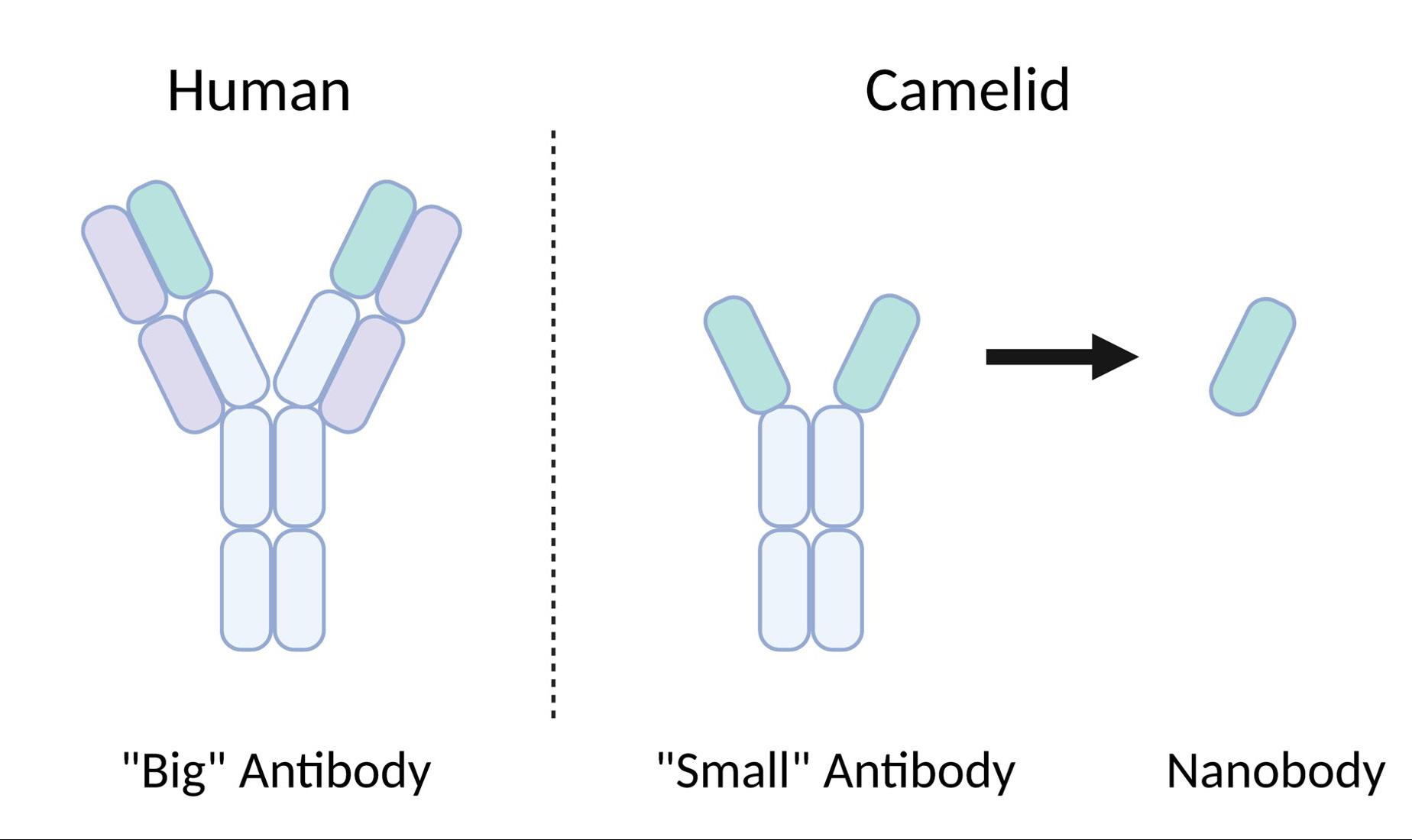

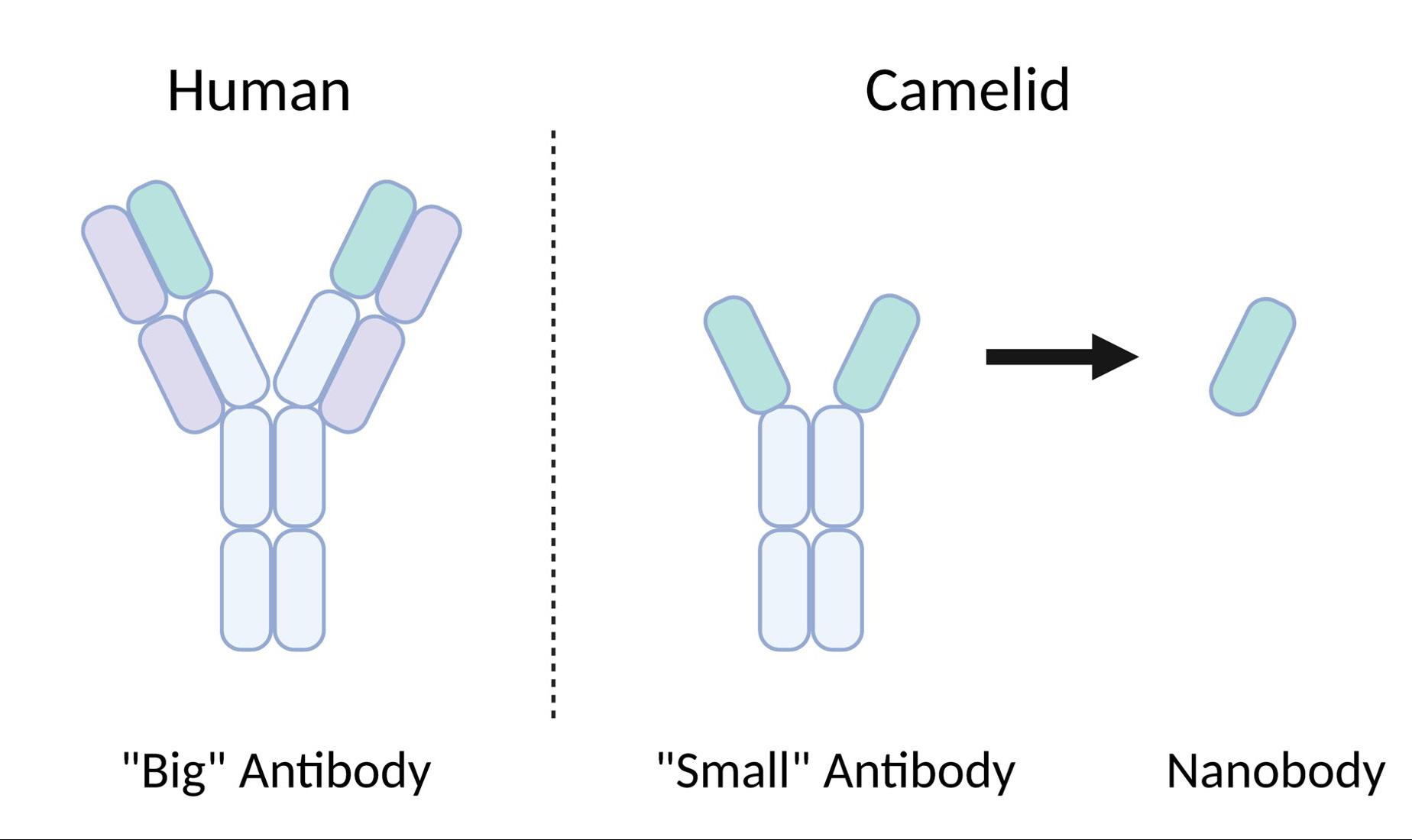

In addition to their uniquely sassy attitudes, llamas have a special immune system. In mammals, the immune system protects us from infections of bacteria, viruses, and fungi. Important components of the immune system are “antibodies”, which bind specifically to these microscopic invaders to help kill and remove them to keep us healthy. In biomedical research, these antibodies can be generated against specific targets, allowing us to visualize and study these proteins in a variety of laboratory applications. Llamas, alpacas, and other camelids are unique as they have an immune system that produces a special type of antibody (a “Small” antibody), which is not found in humans. Through manipulation in the laboratory, we are able to collect and harness only the genes of the protein-binding regions of these small antibodies. We call these fragments nanobodies (Figure 1).

Nanobodies offer many unique benefits for use in research. They are 1) much smaller in size compared to traditional antibodies, and thus can bind to more difficult to reach proteins, 2) stable and easy to store, 3) significantly cheaper to produce compared to regular antibodies, and 4) versatile and can be used in various biomedical research and treatment applications. For example, nanobodies are used to make SARS-CoV2 virus particles visible on human cells or to follow by positron emission tomography (PET) scanning how immune cells infiltrate metastatic tumors in a living animals, a technique about to be adapted for clinical use in human cancer diagnostics.

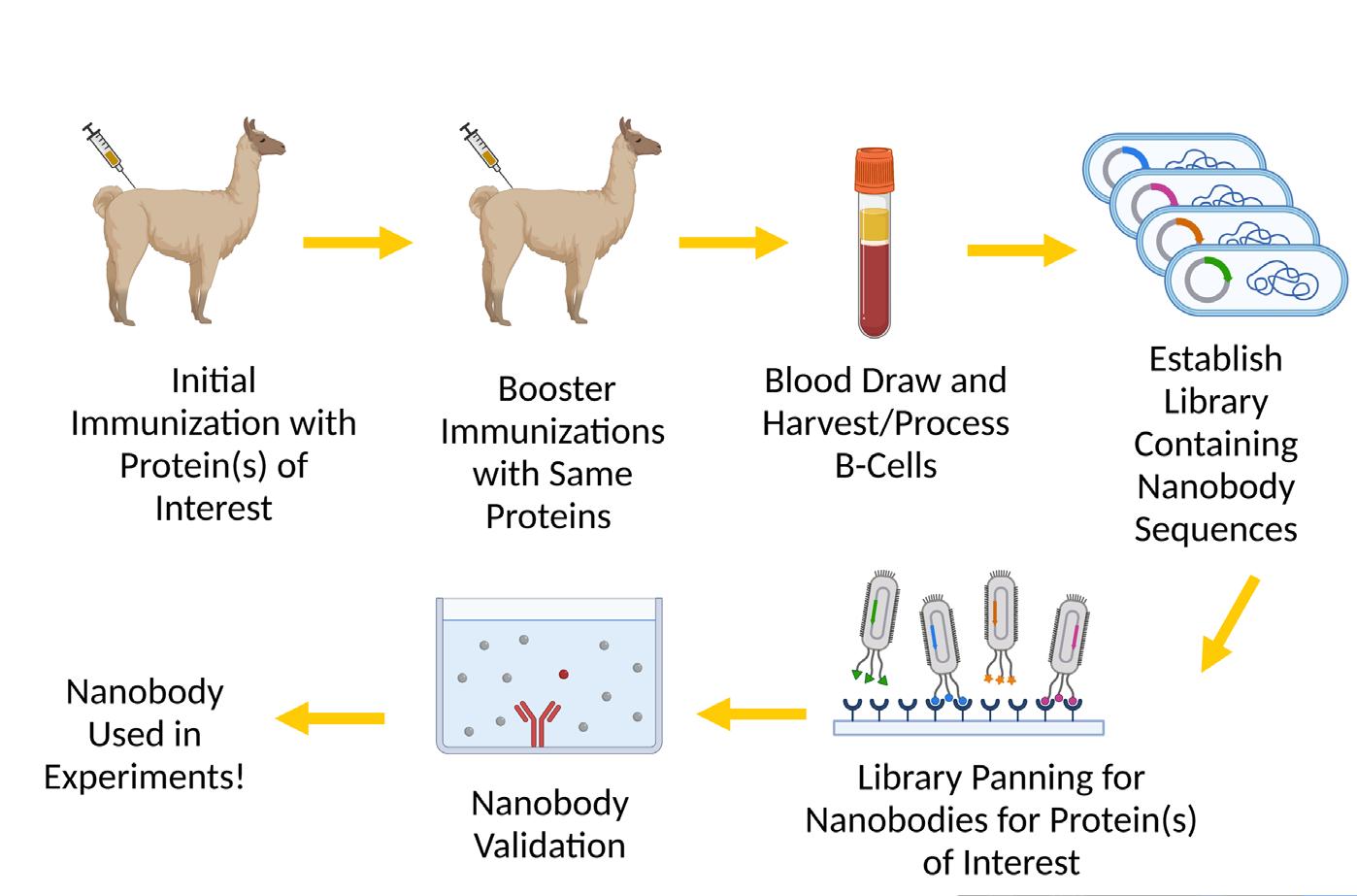

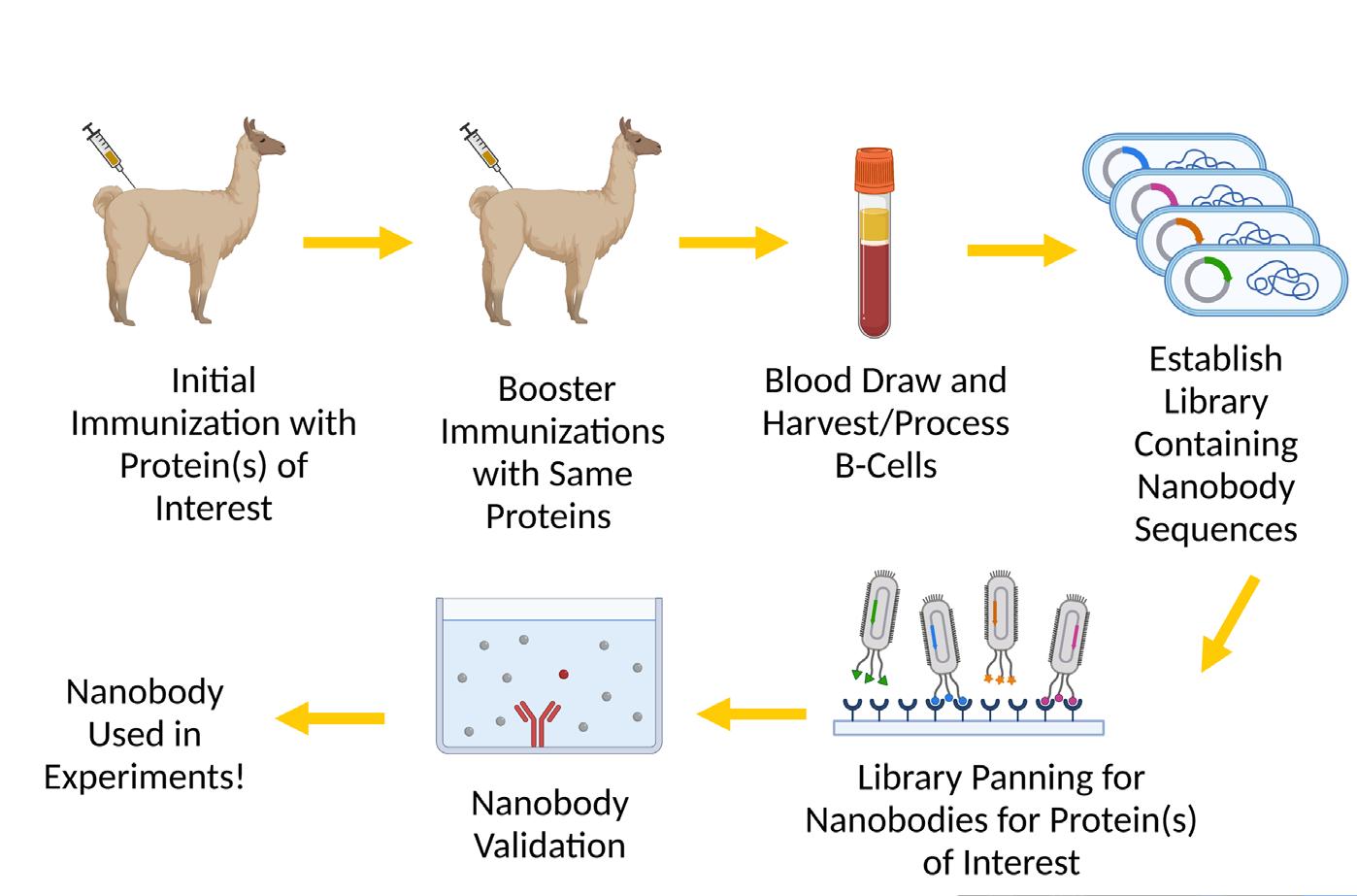

To generate such nanobodies, our collaborator, Dr. Brooke Pallas, Assistant Professor of the Unit for Laboratory Medicine (ULAM), immunized the llama, Moment of Victory, with a cocktail of proteins that we sought to create nanobodies against. Similar to standard vaccination schemes, we followed the initial immunization with several booster shots to maximize nanobody production and selection in the llama. At the end of the immunization campaign, we collected a small amount of blood from Moment of Victory, from which we then isolated nanobody-

encoding genes out of nanobody-producing cells (Figure 2). Importantly, the entire process was pain-free and without complications for Moment of Victory, who remained with his herd throughout the immunization process. In Dr. Truttmann’s lab, we generated a nanobody library, which we then screened for nanobodies that only bound our proteins of interest.

In addition to generating innovative tools for our own research, this project also highlights the excellent collaborative community of the University of Michigan: Dr. Brooke Pallas (ULAM) performed the immunizations and collection of llama blood samples; the protein cocktail used for immunizations contained proteins of interest to several UM research groups, including the Shah, Tessier, Wang, Lieberman, Osawa, and Truttmann labs. Thus, nanobodies from this single llama immunization campaign will support ongoing cancer and neurodegeneration research in our department and elsewhere at UM; and finally, the role of our community collaborator and owner of Moment of Victory, Bob Douglas, cannot be overstated. Without his commitment, generosity, and curiosity to support our research, this project would not have been possible. We all enjoyed learning more about llama biology during our numerous visits to Bob’s farm last summer, one of the rare highlights in an otherwise challenging year. Altogether, this project could not have been completed without the efforts of these numerous individuals and groups.

The labs involved in this project would like to thank Bob Douglas and Moment of Victory for their contributions to UM science and research! If you would like to learn more about our nanobody-based research and/or support it, please visit: https://truttmann. lab.medicine.umich.edu/.

11 Physiology Matters

ALUMNI

What is your current position?

Christina Bennett, PhD - 2005 MIP Alumnus - Ormond MacDougald Laboratory

- Current position: Publisher at American Chemical Society

I work as a publisher at the American Chemical Society (ACS), and I guide the strategy and business needs of about 30 out of the 70+ scientific journals published by ACS. I oversee the team of managing editors for those 30 journals in my portfolio and work with the larger team of publishers to help ensure that our staff and editors have what they need to keep their journals successful. For example, our team makes sure that the journals are reaching the right audience and publishing the right content, the editors and editorial boards are diverse and balanced in expertise, and the journals are represented at conferences, webinars and other events. I am involved with some ethics cases at ACS but focus more on the final review of these matters rather than the entire inquiry process. This is in contrast to my previous role, where I worked as the Publications Ethics Manager at the American Physiological Society.

Nicole Lockhart, PhD - 2005 MIP Alumnus - Susan Brooks Laboratory

- Current position: Program Director, Division of Genomics and Society, National Humone Genome Research Institute

I am the program officer for grants relating to ethical, legal and social implications of genetics research at the National Human Genome Research Institute. I help grantees who may have research ideas in this field by discussing their specific aims and the grant process. Grantees come from a variety of backgrounds, including philosophers, lawyers, and clinicians. I am intentional in making sure a diversity of research communities are represented in my portfolio. Furthermore, I provide support to other NIH research programs that may have ethical and social implications. In this role, I provide advice on informed consent, recruitment, and data sharing in a consultative role.

Min-Hyun Kim, PhD - 2022 MIP Alumnus - Liangyou Rui Laboratory

- Current position: Assistant Professor, Nutrition - Arizona State University

After completion of my postdoctoral training with Dr. Liangyou Rui in MIP, I joined Arizona State University as an Assistant Professor of Nutrition in January 2022. My laboratory, in beautiful downtown Phoenix, investigates the molecular mechanisms of obesity and type 2 diabetes, with a focus on metabolic hormones such as leptin and insulin. Research is the most important part of my job and I spend most of my time doing research-related activities such as conducting experiments, writing grants, and reading literature . I also teach undergraduate and graduate courses, which require time to prepare course materials and grade assignments/exams.

Steven Romanelli, PhD - 2020 MIP Alumnus - Ormond MacDougald Laboratory

- Current position: Senior Consultant at TRINITY

I work for TRINITY, a global strategic advisor to the life sciences industry. As a senior consultant my roles involve leading and managing primary market research across projects, overseeing development of research materials and analyses, and communicating relevant findings to clients. Since starting in August 2021, I have worked on projects that involved launching a drug in the neurology space, building sales forecasts in the pain management field and understanding the impact of new therapies on prescribing habits in the oncology sector. I have had the opportunity to work with large pharmaceutical companies to mid-sized biotechnology companies and have been able to see first-hand how science and business intersect in the real world.

• How did MIP and the University of Michigan help you get to your current position?

Christina: I credit the University of Michigan and MIP for instilling many core truths, including the feeling that no project is too big: everything is possible. My time in MIP gave me the confidence and resilience to take on new projects and experiences. I also learned to be inquisitive and to ask questions, knowing that one cannot be an expert in everything. I still remember the infectious energy of the department and how many of the graduate students and faculty were my biggest cheerleaders. MIP’s collaborative, positive, and encouraging environment were crucial in shaping my time during my PhD. I am still in regular contact with multiple Michigan faculty members and graduate school peers. Finally, MIP’s close relationship with the APS was highly beneficial for my own career; former department chair Dr. John Williams was APS president while I was in the department and he encouraged us to become members of APS and get involved in the society. This membership helped plant the seed for my career within professional societies.

•

12 Physiology Matters

Nicole: I am grateful for my time in the Department of Molecular & Integrative Physiology, where I learned key lessons for my journey through science and my career. During my PhD at the University of Michigan, I learned to be open to interdisciplinary science, the importance of collaboration, and how to foster collegiality and maintain meaningful interpersonal relationships. More broadly, Michigan excels in so many different disciplines, which helped open me up to other fields of study; I was able to learn the value of having a diverse intellectual foundation. I took graduate-level classes in law and public policy, lecturing for one of the policy classes I greatly enjoyed. Due to my wide range of experiences at the University of Michigan, I was awarded two science policy fellowships after graduation: the Christine Mirzayan Science and Technology Policy Graduate Fellowship Program, and the AAAS Science and Technology Policy Fellowship.

Min-Hyun: As my background is in nutrition, my research techniques were limited to basic biochemistry and dietary interventions in animals. However, my postdoctoral training in the department of MIP provided me with a broad experience in molecular biology, physiology and neuroendocrinology utilizing transgenic mouse models, virus-mediated gene delivery and stereotaxic microinjection. I believe these skills served as a basis in building a strong nutritional science research laboratory and allowed me to expand my research to broader biomedical topics. In addition, the NRSA F32 postdoctoral fellowship greatly helped me obtain a faculty position. The fellowship not only financially supported my research, but it also became a good example while preparing job applications to demonstrate the competitiveness of my research.

Scientific communication is a key part of any research, and I am grateful that MIP offered ample opportunities to present one’s work by way of seminars, research clubs, symposium etc. I actively participated in ‘Cellular Aspects of Diabetes, Obesity, and Metabolism Research Club’ and ‘Neuroendocrine Control of Metabolism Research Club’. Not only was I able to present my research and get healthy feedback from field experts, but it was also a great opportunity to meet renowned scientists and expand my scientific knowledge. In addition to research, teaching is an important part of the academic research setting. I participated as an instructor in teaching Physiology 415 course (Laboratory Techniques in Biomedical Research) offered by MIP. which really helped my teaching methodologies and offered insight into developing the course curriculum. This experience is coming to fruition as I am teaching an undergraduate course at Arizona State University. I believe the PHY415 is one of the most valuable opportunities for MIP scholars.

Steven: Communication and presentation skills are essential to being a consultant. On a typical day, you are expected to synthesize a lot of information and distill key findings into a slide deck; you then need to communicate that information to your team and/or client. I’ll forever be grateful to Ormond and the “MacLab” for all the lab meetings, practice talks, and presentations that allowed me to develop these skills. Additionally, the Physiology Department provided several opportunities to present and receive feedback, which was a great chance to practice speaking in front of a large audience and field questions on the fly.

At the end of my first year, I was accepted into the Cellular Biotechnology Training Program (CBTP) through the College of Engineering which allowed me to do an internship at AstraZeneca in Cambridge, UK. I was able to further my thesis work and contribute to two publications with industry scientists, as well as gain industry experience.

I was also an active member of miLEAD Consulting Group, a graduate student and postdoc-run consulting firm, where I served as president from 2018-2019. This gave me my first experience in consulting and is ultimately what pushed me to pursue consulting full-time. I would recommend any student who is interested in consulting or industry to get involved; it is a phenomenal activity to have on your resume and will make you stand out while helping you build a community of people with similar interests at the University of Michigan.

• What advice do you have for incoming trainees?

Christina: Enjoy the process of graduate school. Every step provides new skills and experiences that can go into your toolbox for success in future positions. Additionally, select a thesis topic that will really interest you for the next few years knowing that it does not have to be the topic you study for the rest of your career. Finally, join a lab group that provides the type of energy you need to thrive. Quiet or social, competitive or collaborative. Whatever it is, you want a place where you feel comfortable to develop and grow into an amazing research scientist.

Nicole: Take advantage of all MIP and the University of Michigan have to offer. This could range from spending time in a lab down the hall to learn a new technique to taking a class in a different school or department. Don’t forget to learn from those around you. You are in a rich environment with researchers of all different backgrounds and levels. Take the time to learn from them scientifically, professionally and personally. Consider what makes someone a compelling presenter or different approaches to balancing professional and personal responsibilities.

Min-Hyun: While I received a postdoctoral fellowship, I did not ambitiously apply for other research grants or fellowship opportunities. Throughout my academic career, I learned that the doors of opportunity only open to those who continually knock. If I were to begin my graduate school or postdoctoral training again, I would put much more effort into writing grant proposals. MIP maintains an exhaustive list of funding opportunities which is available. Moreover, there are emails routinely sent out for applying to internal and external fellowships and I would highly advise students/postdocs to actively apply for these fellowships. During my job interview, I was often asked to share my personal experience about my contribution to society as a PhD. I wish I would have actively participated in community engagement and outreach programs provided by the department, like SEEK (Science Engagement and Education for Kids), and would encourage students/postdocs to participate. Lastly, don’t hesitate to ask for help. We face so many failures and stresses from our research and school life. Ask your advisor, colleagues, and other labs. Use all the resources available to you. MIP has so many amazing resources!

Steven: One area I would have liked to gain more experience in is data science. Analyzing large data sets is a daily job function, and while I have been able to get training at work, it would have been much better to enter with those skills in my toolbelt. I’d encourage anyone interested in consulting to get experience with the coding software R to gain familiarity with using Excel to run analyses (even though that is frowned upon in academia!). Also, be “selfish;” graduate school is the best time to find whatever it is you like and get completely immersed in it, whether that’s in the lab or outside of it. Don’t be afraid to pave your own path and take risks. Make sure you are always looking for opportunities to gain handson, real-world experience.

13 Physiology Matters

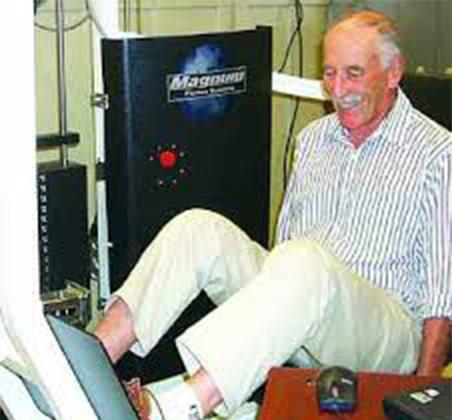

When Brian Carlson graduated from the University of California (UC) Berkeley with a bachelor’s degree in mechanical engineering, pursuing a PhD was far from his mind. After graduation, Brian worked as an engineer designing machinery used to coat silicon wafers with a thin film of conductive metal (which is part of the chip manufacturing process). Brian worked alongside several engineers, one of which had his master’s degree and made it known that his advanced degree elevated him above the other engineers. That’s the moment when Brian realized that in industry, educational status matters: “knowledge is power…I’m getting a PhD”. Among other factors that encouraged Brian to think outside of industry was that the company was bought out and downsized, which gave him the opportunity of going back to school. While applying to graduate school he worked as a sales representative for a group of East Coast manufacturing companies that needed representation in northern California. Even when he was accepted to the mechanical engineering PhD program at UC Berkeley, he decided to delay starting graduate school for a year because he liked his job so much: he got to learn about all the ins and outs of the equipment and products he was selling, enjoyed the travel and solving problems that came up between customer and manufacturer.

Although a mechanical engineer by training, Brian was drawn to biomedical research for a very personal reason: his grandma was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. Sadly, 30 years ago, this was a diagnosis with treatments limited to palliative care. “I felt helpless,” said Brian. He explained this fueled a desire to use his skills in science and medicine to help others. At the time, there were few people in the Berkely mechanical engineering department that were doing biomedical engineering research (about 2 or 3 professors max). They were mostly studying fluid flow, heat transfer and how to apply these concepts to biological systems. One of the professors was Stanley Berger, a fluid flow spe-

cialist with a PhD in mathematics from Brown University. He had a bit of funding, and accepted Brian into his lab. This lab studied the dynamics of sickle cell blood flow and how these cells moved through the capillaries when deoxygenated. They used a closed loop mathematical solution for a complex set of partial differential equations governing their motion. With this analysis they could calculate the stiffness of the red blood cells (RBCs) and oxygen concentration in the RBCs at any point in the capillary in addition to the resistance to flow in the capillary. The question they wanted to answer was what did this all mean in the context of a capillary network: what percentage of the capillary bed would shut down when oxygen concentrations dropped in the sickle RBC? This was essentially a fluid flow problem, applied to a disease and its ramifications in the vasculature.

In the early 2000’s there was only a small community working on this. Brian asked his advisor for input on who to contact for next steps and sent many emails to contacts in the field including a young research assistant professor at the University of Washington Dan Beard. Although enthusiastic about Brian’s work, Dan at the time was sharing an office, had no funding and couldn’t offer Brian a position. Eventually Brian received two offers and accepted a position with Timothy Secomb at the University of Arizona. There were many families that were part of the Secomb lab. They even shared the same childcare provider: a small, Austrian family-run day care that often spoke in German to the kids! “It was a fun environment to be in,” recalls Brian. The time in the Secomb lab opened Brian’s eyes a lot; Tim taught him the rigor needed to responsibly apply mathematics to problems in physiology and a methodical approach to addressing and challenging hypotheses. The results may not be too flashy, but you could build upon them in future work. With mathematics many things can be discovered, but many things can also be ‘hidden’ to outsiders if the methodology is not transparent. Tim taught him mathematical methods should be used to test and exhaust all possibilities. Brian’s next postdoctoral position was with James Bassingthwaighte at the University of Washington (who happened to be Dan Beard’s PhD advisor). Jim’s style of research complemented what Brian learned from his previous mentors, he liked making bold statements without compromising scientific rigor. It was a very dynamic lab with lots of different projects, ideas, and collaborations. Many of Jim’s friends visited the lab to exchange ideas. This

14 Physiology Matters

Brian Carlson, PhD Research Associate Professor, Molecular & Integrative Physiology

helped broaden Brian’s scientific scope to areas like wholebody hemodynamics, cellular electrophysiology and exchange between blood and tissue in the microvasculature.

During the 2007 World Congress for Microcirculation hosted by the Medical College of Wisconsin, Brian got to reconnect with Dan Beard, who by this time had funding and was a faculty member there. Eventually Dan’s and Brian’s paths converged: Brian joined the Beard Lab in Wisconsin to Sophie’s (Brian’s 4-year-old daughter at the time) dismay , as one day she recalled: “Dad, why did you move us to the coldest place in the world?”. Despite the cold, working with Dan and his lab was great. They were able to write joint grants together, and Brian began to put pieces of his experiences together: adding electrophysiology components on fluid models of the cardiovascular system and being able to test which mechanisms were important in regulating blood flow. At the Medical College of Wisconsin, they had a hard time recruiting graduate students to join their lab. About six students a year enrolled in the department’s PhD program, and many wanted to do wet-lab science only: math was intimidating.

Brian’s journey brought him to Michigan when Bishr Omary began recruiting Dan to the Molecular & Integrative Physiology (MIP) department just as Brian began house hunting in Wisconsin. “I wouldn’t look for houses here right now” was all Dan hinted. The lab moved to the University of Michigan (U-M) and Brian recalls that his experiences have been amazing. There is a lot of support and structure in the medical school, especially within the department. This has been a very significant part of his experience at U-M. He loves now being able to interact with undergrads and grad students. There is an incredible bridge to access clinicians and clinical record databases, as well as a lot of computational and technical support. The internal opportunities for grants were outstanding at U-M as well as extramural grant writing support. Now they were not the weirdos in the Physiology department! Santiago Schnell was here doing math too.

As part of MIP Brian really enjoys his role as an associate research professor because he can do research but still gets to teach! He helps teach the PHYS 520: Computational Systems Biology in Physiology class as well as some biomedical engineering courses. “I like teaching. Sometimes it’s hard to make a lecture, just like it’s hard to write a paper, but you get the same kind of high. It’s the best feeling when you get to see a student struggling with something and after explaining the concept, ‘it clicks’ It doesn’t happen all the time,but when it does it’s a great feeling.” Brian commented.

“It’s also great to see trainees learn how to teach. This summer, in conjunction with Ben Randall (postdoctoral fellow) and Edith Jones Kiyabu (MIP grad student) in the Beard lab, I got to mentor Kiley Hassevoort (an undergraduate summer research student) as a team. It feels as if the spirit of what I learned from Stan, Tim and Jim have been passed on to Ben and Edith through me. There is a commitment to the

legacy in growing the concept of responsibility in mathematical modeling in the fields of physiology and the biosciences” shared Brian.

After Physiology

Jessica Schwartz, PhD Professor Emerita, Molecular & Integrative Physiology

A year before Jessica Schwartz retired in 2014, she became Director of the newly created Office of Training Grant Support at the Medical School. This drew on her prior experience as long-term Director of the University-wide Graduate Program in Cellular and Molecular Biology (CMB), which was supported in part by an NIH T32 Training Grant, and her service on an NIGMS study section which reviewed T32s. This administrative position has continued as she gradually completed studies on mechanisms of gene transcription by Growth Hormone that she carried on in her lab throughout her career. She continues studies on human growth regulation through collaborative work on the short-stature Mountain Ok population that she has studied over the years in Papua New Guinea.

The Office of Training Grant (TG) Support has meanwhile expanded from its inception when Jessica alone advised PIs on Research Training Plans for T32 applications. As NIH TG applications became increasingly digital and required extensive supporting data, the Office of TG Support added experienced administrative technical consultants. In addition, under the auspices of the Office of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies, they have worked with HITS to develop an online database, M-FACTIR (Michigan Faculty and Trainee Information Resource), specifically for TG preparation. The TG Support team provides individualized consultations with TG PIs and Administrators as they prepare applications, and also reviews draft TG text and data tables before submission. They run Workshops that provide updates on the frequently-revised NIH requirements for TG, as well as guidance on the complex NIH TG data tables. Additional information can be found in their newsletter, The Training Grant Advisor (https://mailchi.mp/med.umich.edu/training-grant-advisor1?e=acc354c4c0) and on the TG Support webpage (https://ogps.med.umich.edu/resources/tg/). The pioneering Office of TG Support that Jessica continues to direct has been at the forefront of a trend among peer institutions and participates in a recently established national organization for Offices of TG Support.

15 Physiology Matters

Elizabeth Weiser Caswell Diabetes Institute: Advancing Excellence in Research and Clinical Care

Martin Myers,

MD, PhD,

Marilyn H. Vincent Professor of Diabetes Research and Professor, Molecular & Integrative Physiology

According to the latest research, “more than 100,000 Americans died from diabetes in 2021, marking the second consecutive year for that grim milestone.” In fact, recent reports have indicated that more than 10 percent, or greater than 34 million, people in the United States have diabetes and 88 million adults have prediabetes. The increasing prevalence of diabetes, obesity and associated metabolic conditions in the United States raises concerns over the serious complications that can result such as heart disease, vision loss, and kidney disease.

A long-time leader in research and innovation, the talent, collaboration, and generous resources available at the University of Michigan has enabled substantial contributions to the field of diabetes, leading in the field for decades. To help continue to expand and coordinate these efforts, the Caswell Diabetes Institute was established in 2021.

With the incredibly generous $30 million gift from Ron Weiser and his wife, Eileen, in honor of his daughter, Elizabeth Weiser Caswell, the Caswell Diabetes Institute (CDI) will harness the strengths of Michigan Medicine and the University of Michigan, by accelerating dynamic research, robust training programs, and advancing excellence in clinical care to patients with diabetes, obesity, and other metabolic disease conditions.

Michigan Medicine has been recognized as a top ten hospital for Diabetes and Endocrinology care, and the University of Michigan campus is home to more than 250 world-renowned researchers in diabetes, diabetic complications, obesity, and metabolic disorders. The creation of the CDI allows us to truly support the scholarship and mentoring necessary to build the talent and pipeline of experts.

Additionally, the CDI provides the infrastructure to stimu-

late progress in research and clinical care as we collectively seek better treatments, and ultimately cure and prevent diabetes, obesity and other metabolic conditions. The CDI can support established scholarship, research and services, while also providing the mechanism for innovation through pilot programs and patient and family centered quality improvement initiatives.

The CDI is led by Martin Myers, MD, PhD, Marilyn H. Vincent Professor of Diabetes Research, whose research focuses on the process that enables the body to respond normally to insulin and “glycemic control centers” and the actions of the key metabolic hormone, leptin. Dr. Myers also serves as Director of the Michigan Diabetes Research Center – and his inclusive approach to leadership has brought forth the expertise of a dynamic team of researchers and clinicians that are dedicated to ensuring that the CDI is supporting and advancing the most important diabetes related research that not only break important new ground, but also can lead to advancements in clinical care and beyond. This includes ensuring integration and coordination among the affiliated diabetes centers.

The CDI coordinates and offers comprehensive support and guidance, integrating mentoring and fellowship in addition to an array of core services and resources. For example, the CDI leads the competitive Clinical-Translational Research Scholars Program (CTRSP), led by Dr. Rodica Pop-Busui, to support early-stage clinical faculty, and funds protected time from clinical care duties to help establish robust research programs. Thus far, the CDI has supported 4 CTRSP scholars, including Lindsay Ellsworth, MD, Yu Kuei Lin, MD, Brian Schmidt, DPM, and Kara Mizokami-Stout, MD.

Serving as the umbrella organization, the CDI works with the P30 Centers to lead and coordinate enrichment programs across the campus. This effort is led by Dr. Brigid Gregg, Assistant Professor of Pediatrics, Medical School, and Assistant Professor of Nutritional Sciences, School of Public Health, and helps ensure broad engagement and collaboration across schools and departments.

Other big initiatives in this first year have included the advancement of the integration of clinical research technology through an Electronic Health Record (EHR) Program. Led by Dr. Joyce Lee, this program works with Precision Health

16 Physiology Matters

to improve access to a repository of longitudinal EHR data for patients with diabetes, obesity, and metabolic disorders – including treatments, outcomes, and personal device data. This program also offers a robust consultative service, leveraging IT tools to support integration of research into the “real world” healthcare delivery setting.

Because the care of current patients and families remains paramount to the goals of the CDI, efforts are in place to move toward the integration of clinical research and care through the support and development of innovative hybrid clinical research programs. Highlights include the Genetics of Diabetes and Obesity Program, run by Dr. Elif Oral that seeks to provide molecular diagnosis and appropriate care for those with genetic causes of metabolic disease, as well as the Weight Navigation Program, led by Drs. Kraftson and Griauzde, which offers personalized, effective obesity treatment in primary care settings through the integration of physicians certified in obesity medicine into primary care teams, to ultimately help individuals find a path toward effective, personalized weight control, leveraging evidence-based science. The goal of these programs is to provide new research-focused resources that will lead to new discoveries, while simultaneously improving the care of those with diabetes, obesity and related conditions.

By serving as a central hub for diabetes care and research and supporting rigorous science and its integration with patient-centered clinical care, the CDI plans to lead the way in preventing, treating, and ultimately curing diabetes, its complications, and other related metabolic diseases…not just here in Michigan, but for the world.

Rachel Reinert, MD, PhD: One key aspect of the CDI is the commitment to increase the number of investigators performing cutting edge research through both recruitment and retention of faculty. An enormous achievement in this effort includes the addition of Rachel Reinert, MD, PhD, who became tenure-track Assistant Professor at Internal Medicine, University of Michigan Medical School this past year. Dr. Reinert’s interest in medicine originated in childhood summers spent with her grandmother, whose diabetes was one of the defining struggles of her life. While working as a laboratory technician in college, she became fascinated with research exploring dietary and pharmacologic mechanisms that regulate amino acid metabolism. As a first-generation college graduate, she found guidance through a trusted mentor and entered a combined medical and research training, where her passion for science met her aim to contribute to significant clinical impacts. In 2014, she joined the Physician Scientist Training Program at U-M to pursue clinical and research training in endocrinology. Here, she became fascinated with the concept of protein misfolding as a primary contributor to diverse endocrinologic diseases, including diabetes and obesity. She joined the laboratory of Dr. Ling Qi and was introduced to endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-associated

degradation (ERAD) as a critical machinery that protects against endocrine cell dysfunction. In 2021, she received an NIDDK K08 Career Development Award to further her work on protein quality control in glucagon-producing pancreatic islet alpha cells, aiming to better understand their contribution to glucose homeostasis. Her overarching goal is to unravel the mechanisms underlying intracellular and intercellular communication within pancreatic islets to identify novel targets for diabetes therapeutics. As a member of CDI, Dr. Reinert hopes to not only continue her own pursuit of research discovery in practice, but aims to inspire others to do so – serving as Medical School faculty in addition to her roles as a physician in the Metabolism, Endocrinology & Diabetes (MEND) Clinic, as well as an independent research scientist.

Dr. Alison Affinati, MD, PhD: Dr. Affinati is an internal medicine provider with medical specialization in endocrinology, diabetes & metabolism. She is currently a post-doctoral fellow in the laboratory of Dr. Martin Myers, which focuses on the biology of leptin, a hormone that regulates physiological processes relevant to diabetes and the metabolic syndrome. Circulating leptin enters the central nervous system to inform the brain about nutritional and metabolic status by activating the leptin receptor (LRb) on specific neurons. These neurons regulate metabolism (including glycemic control) and endocrine function. Dr. Affinati’s work focuses on ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus (VMH) controls with diverse behaviors and physiologic functions, as well as the involvement of the brain in the regulation of both immediate fuel availability (for example, circulating glucose) and long-term energy stores. In addition to her research in the laboratory, Dr. Affinati is a member of the Physician Scientist Training Program, where she balances the time between her patients, where she can provide focused, personalized care, to time in the lab, where she can continue to pursue discoveries that will have real world application. Growing up, she always knew that she wanted to be a physician – and seeing her uncle manage type 1 diabetes left an early impression about the unfairness of a diagnosis that often has a childhood onset, that requires such significant lifestyle challenges, with long term implications. Now, as a physician at the Metabolism, Endocrinology & Diabetes (MEND) Clinic, Dr. Affinati can continue to learn from her patients, as managing care can change with age and variable environmental factors – and is glad to stay connected to the impact that this disease has on people’s lives. One recent highlight includes Dr. Affinati and colleagues work to explore the connection between severe hyperglycemia and insulin resistance in patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection, which may represent unique clinical features to further explore.

*For more information on diabetes visit https://www.cdc. gov/diabetes/basics/diabetes.html

*For more information on the CDI, visit https://medicine. umich.edu/dept/diabetes-institute

17 Physiology Matters

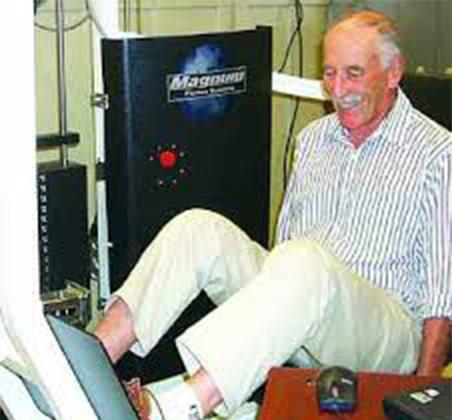

Embracing the Journey, Not Just the Destination

Steven Whitesall’s career trajectory has been anything but ordinary. “Trajectory doesn’t always go the way you wanted…but keep trying,” shared Steven. Steven originally planned to attend vet school after graduation so he decided to pursue zoology as a major at Michigan State University (MSU). When asked why he studied zoology, Steven replied soundly: “To study a crazy animal like Louis G. D'Alecy!”. But in earnest, Steven really liked all aspects of zoology so much he would spend all Saturday working in the lab to study developmental differences among mammals, instead of attending Michigan State football games! Thankfully the lab had a window that when opened allowed Steven to hear what was going on in the field.

Steven lives in Chelsea, Michigan and babysat for James Alford who was the associate director of ULAM from 1978-90 and who was very instrumental in building the Life Sciences Institute (LSI). When Steven failed organic chemistry 3-4 times, James assured Steven that he still trusted him with his kids and encouraged him to keep working hard and go back to school. After Steven completed his degree at MSU, James told Steven’s mom there might be something for Steven working with Louis D'Alecy in the Department of Physiology. According to Steven, his experience in babysitting prepared him well for lab management. “Taking care of

kids is like taking care of a lab in a way: there’s mice, undergrads that drop samples, lots to take care of.” Steven met Dr. D'Alecy and joined the laboratory in 1992. It was to be a trial of a month or so to see how they worked together…30 years later, they are still working together.

Steven is now the Physiology Phenotyping Core Manager and many of his experiences prepared him to rise to this challenge. Steven spent over 20 years in the D’Alecy laboratory, much of which was studying large animal models of ischemia caused by stroke or other diseases. Working side by side with Dr. Alecy, postdocs and lab assistants, Steven would help with animal surgeries, placement of catheters and electrodes and collecting samples. Several undergrads would come to the lab to help measure and study blood gas exchange and other such parameters. They had great times. They would order food from Angelo’s and eat lunch in the office next to the lab, talk about science and go back to the bench. Dr. D’Alecy didn’t care much about bureaucracy. He cared about the students, teaching science, and learning together. This proved to be the perfect environment for Steven to flourish. Dr. D’Alecy eventually gave Steven more and more experiments and responsibility in the lab.

During his time in the lab, Steven also helped Dr. D’Alecy

18 Physiology Matters

Steven Whitesall, Research Lab Specialist, Molecular & Integrative Physiology and Edith Jones Kiyabu, Graduate Student, Molecular & Integrative Physiology

set up and develop high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), for measuring metabolites released by ischemic tissues. Steven and Dr. Alecy struggled because they really weren’t experienced at such a complicated assay and it took a lot of time and energy out of an already busy lab, but they kept at it and the new assay created a lot of support for other labs. “Science is hard work, long hours, but it’s good to work with a lot of people with a lot of academic/ professional training. Lou, and now Dan Michele, have been instrumental in training me.” Shared Steven.

The start of the phenotyping core was very collaborative and a great team effort. The Physiology Phenotyping Core (PPC) was officially founded in 2011, merging two existing cores that were focused on cardiovascular disease and in the 2000s Professors John Williams and Joe Metzger led the faculty in creating the Center for Integrative Genomics. This core had animal treadmills, running wheels, ultrasound imaging and non-invasive blood pressure measurement. With support of a program project grant, Dr. D’Alecy and Steven established a mouse telemetry facility for measuring blood pressure and electrocardiogram (ECG) in awake rodents. The merger of the two cores and new leadership from Dan Michele brought a significant investment from the Frankel Cardiovascular Center (FCVC) to help grow the core’s support of surgical models and establish two facilities. One facility remained in the Physiology department, near the D’Alecy lab, and the other was established at the North Campus Research Complex. The core needed an expert surgeon and Steven took on the challenge to become the PPC lab manager and lead surgeon.

Currently within the PPC, Steven manages regulatory compliance, handling of the animals, performs microsurgeries and manages the telemetry service. Thanks to everything Louis had taught him and put him in charge of, Steven has been able to rise to the challenge. Dan Michele has been great too and has been extremely patient. “Dan is also very patient and thorough when it comes to designing animal models. Dan is wearing 3 or 4 hats: lab PI, department interim chair, director of the core, yet he is never upset. He comes back with great ideas and motivation; he is really smart. Dan always has great scientific answers, and works as a team.” remarked Steven.

With the collective support of the department and the FCVC to help administer the core, it has established many regular customers, including investigators within the department and across the medical school. Although some of the work is more routine now, it stays exciting when new customers want to try something different. To develop these new approaches and measurements we are grateful to continue to have the support of Dr. D’Alecy as an advisor, as well as other investigators who lend their expertise and advice.

One of Steven’s favorite images, that represents his time in the physiology depart-

ment, is a photo of a coffee stain on a lab notebook that was chosen as the cover art for an article the department published. To Steven, this showed the grass roots of where science comes from, “keeping it real: All your senses need to be opened to answer what is not always obvious”.

Steven really enjoyed collaborations and the dynamic energy in Dr. D’Alecy’s lab, eating lunches together, reading manuscripts, and writing. Steven was so busy with new surgical techniques in animal models for the first few years in the core, that he couldn’t help out much in experiment design. As for now, Steven is really enjoying a collaboration project with members of the Beard Lab: Dan, Fran and Feng, designing experiments and measurements to study baroreceptor function. “Designing the experimental plan, seeing the outcome, and refining the plans to make it better is the best part of the project, it keeps you excited and interested”, shared Steven enthusiastically.

Kimber Converso-Baran has also been instrumental for the core in bringing ultrasound imaging expertise from the Mott’s children hospital to animals! Her expertise in small vessel imaging in humans allowed her to readily adapt to imaging animals as small as mouse embryos. Working together in the core, Steven performs surgeries and Kimber often images the animals before and after surgery. They keep a positive environment in the lab through laughter, which helps them diffuse the situation when a problem arises or when something doesn’t work. “Incredibly talented” remarked Steven. “I wouldn’t know what the core would do without her expertise”.

In his free time, Steven enjoys playing vintage base ball (two words in the old days), with the rules as it was played in 1865: no baseball gloves! Steven also likes hunting and fishing, loves his family and really enjoys spending time with them. His wife Amy has been extremely supportive of Steven, while she also pursued a career in journalism. Steven and Amy are very proud of their two sons: Ben just became an officer in the Marines Combat and Engineering Division. His younger son Nicholas just finished his fouryear appointment in the Marines and is looking forward to life together with his fiancé, Chandler.

19 Physiology Matters

Since 1882, the Department of Molecular & Integrative Physiology (MIP) has successfully trained over 250 students. These students have gone on into a diverse range of positions such as academia, industry, communication and more. As the #2 NIH funded program in Physiology, students are afforded an abundance of resources and training facilities. Furthermore, graduate students are trained and mentored by distinguished alumni such as Drs. Dan Michele, Sue Moenter and Elizabeth Rust who were classmates themselves, and alum Sue Brooks. Each graduate student undergoes a unique journey that includes lab rotations, passing the preliminary exam and ending with a dissertation defense. Here are some snapshots of students in each stage of their journey!

New Beginnings in Ann Arbor:

Hannah Thompson, 1st Year

It’s hard to believe that it has been almost a year since I arrived in Ann Arbor! While this year has been filled with its fair amount of struggles and successes, I am so incredibly grateful to have started this journey in the department of Molecular & Integrative Physiology. Having worked as a full-time research assistant in Minneapolis before pursuing graduate school in Ann Arbor, I was unsure how well I’d fare in a graduate school setting where I’d have to balance rigorous coursework on top of lab work. However, I was also excited by the massive amount of research opportunities and labs available to rotate in (eight week experiences in a lab before selecting a thesis lab) in. I remember

how energized I felt after my first day of classes and lab, though these feelings would often come and go as I got deeper into the fall semester. There were days where it felt like leaving the program all together was the best option, however, with the support of loved ones and the program, I decided to stay and I am so grateful I made that decision! The support of Molecular & Integrative Physiology and all of its students are incredible and I think of the department as my second “home”. I have been fortunate to start my graduate career with a brilliant cohort that has pushed and challenged me to grow everyday and upperclassmen who are always willing to extend a helping hand. As I attend student seminars and attend classes, I am absolutely humbled that I get to start my training in the presence of scientists who I truly believe will change the world.

The opportunities that the University of Michigan and Molecular & Integrative Physiology have been indelible. In the short time here I have grown beyond my expectations as a scientist and I look forward to choosing a thesis lab, becoming a doctoral candidate, working towards my professional dreams and making our department proud. Go Blue!

Becoming a Candidate: Jess Maung, 2nd Year

The process of choosing a lab and settling into my research was super exciting for me – after a year of rotations, I finally found my home for the rest of my time at the University of Michigan. However, I had one more hurdle to overcome before diving headfirst into my thesis project and into my second

20 Physiology Matters

Hannah Thompson First Year Graduate Student, Molecular & Integrative Physiology; Jess Maung Second Year Graduate Student, Molecular & Integrative Physiology; Edith Jones Kiyabu Sixth Year Graduate Student, Molecular & Integrative Physiology

year of graduate school: the preliminary exam. Passing the preliminary exam, or “prelims,” is required to advance to candidacy within the Molecular & Integrative Physiology graduate program. Prelims consists of two parts: the first, writing a proposal about a research project, often one’s thesis work, and the second, presenting and defending your project while demonstrating your fundamental knowledge of physiology and techniques. It is the ultimate test of real-time problem solving, putting one’s critical thinking skills to the test as you navigate a committee of faculty members that ask detailed and thought-provoking questions. Among graduate students, the preliminary exam, also known as “prelims,” is feared and anxiety-provoking. Technically, one’s continuation in the graduate program is contingent on passing prelims. However, professionally and personally, passing prelims is a huge accomplishment for oneself; it also gives helpful guidance and input for your future project going forward. Other MIP graduate students gave me great insight into what the prelim process is like and encouraged me to persevere through the process, reassuring me that it wouldn’t be as daunting as I had made it out to be. I am grateful for the support from the department and from my fellow cohort members for helping me prepare.

The day I passed my (virtual) preliminary exam was fantastic: my lab surprised me with a bottle of champagne and I took a long afternoon nap. Overcoming this huge academic hurdle helped me feel more confident and prepared to tackle the next chapter of graduate school. The second year of my PhD has been full of ups and downs, including being the first to discover something exciting while I’m on the microscope, juxtaposed with not receiving grants and awards I’ve spent countless hours applying for. I look forward to the next few years of my PhD as I tackle novel scientific questions, connect with the warm community around me, enjoy pub nights with MIP graduate students, and make memories in Ann Arbor.

Preparing to Defend & Graduate:

Edith Jones Kiyabu, 6th Year Time has flown by so fast since I first started in MIP, I can hardly believe I’m close to finishing this chapter! My grad school journey took some unexpected turns, providing multiple experiences and opportunities for both personal and professional growth. In grad school missing my family in Texas was one of my biggest challenges and without their prayers, unconditional love and support I could not have made it this far, MIP has likewise been extremely supportive through this journey, and I have enjoyed the department’s collaborative environment. The Beard lab has provided the infrastructure and direction required to pursue my thesis work combining both classical biochemistry techniques with computational modeling to understand the metabolic and mechanical aspects of heart failure with the support from the Systems & Integrative Biology and F31 NIH heart and lung institute grants. Besides

pursuing my graduate work I got to participate in several diverse experiences such as the Summer School in Computational Cardiac Physiology hosted by the Simula Research Institute in Oslo, Norway in collaboration with the University of California, San Diego, fostered my interests in innovation and entrepreneurship including participating in the Sanger Leadership Center Graduate Leadership Crisis Challenge, the Research Innovation Scholarship Education (RISE) Advisory Council at Michigan Medicine and in the Fast Forward Medical Innovation (FFMI) fastPACE. As a native Spanish speaker, I volunteered with Filter of Hope and University of Michigan-Gradcru aiding in installing purification water filters in communities without clean water access and as a Spanish-English translator during Spring Break of 2019 in Havana, Cuba as well as serve as a medical translator for a COVID-19 clinical trial at UM.

On a more personal note, life took quite an unexpected turn in the summer of 2019 when I found myself homeless and destitute. That’s right, I was in between leases and needed a place to live for a month. After not being able to find any leads a family from church graciously offered to host me but they lived in Saline, Michigan about 30 minutes away from NCRC where the Beard Lab is. Not a bad commute but… I didn’t have a car! When I found out there was a mechanical engineering grad student in my Bible study group that lived in Saline and commuted everyday to North Campus, the little gray cells began thinking: He can be my ride to the lab! Little did I know I’d be marrying this man in the summer of 2021! Moral of the story: beware of being homeless and destitute and taking rides with eligible young bachelors. As newlyweds we are trying to wrap up grad school and figure out next steps. I suppose we have a ‘two-body’ problem, a ‘good’ type of problem that in all honesty I never sought or thought I would have at the end of grad school. We are still discerning next steps, but we are leaning into pursuing academic postdocs. This decision-making process is new to us and can sometimes feel like a daunting process as we are learning how to approach it as a couple and early career scientists, but we both want the best for the other and are excited to start the next chapter whatever it looks like with our best friend by our side.

In Conclusion…

Graduate school can be a difficult but rewarding journey. From choosing a lab, to applying for grants, to navigating thesis committee meetings, to defending your dissertation, Molecular & Integrative Physiology has a supportive environment that will be there with you every step of the way. To graduate with a PhD from MIP is a badge of honor. Mirroring our previous alumni such as Drs. Michele, Moenter , Brooks and Rust, we look forward to successful careers where we can represent the excellence of MIP and wear our badges proudly.

21 Physiology Matters

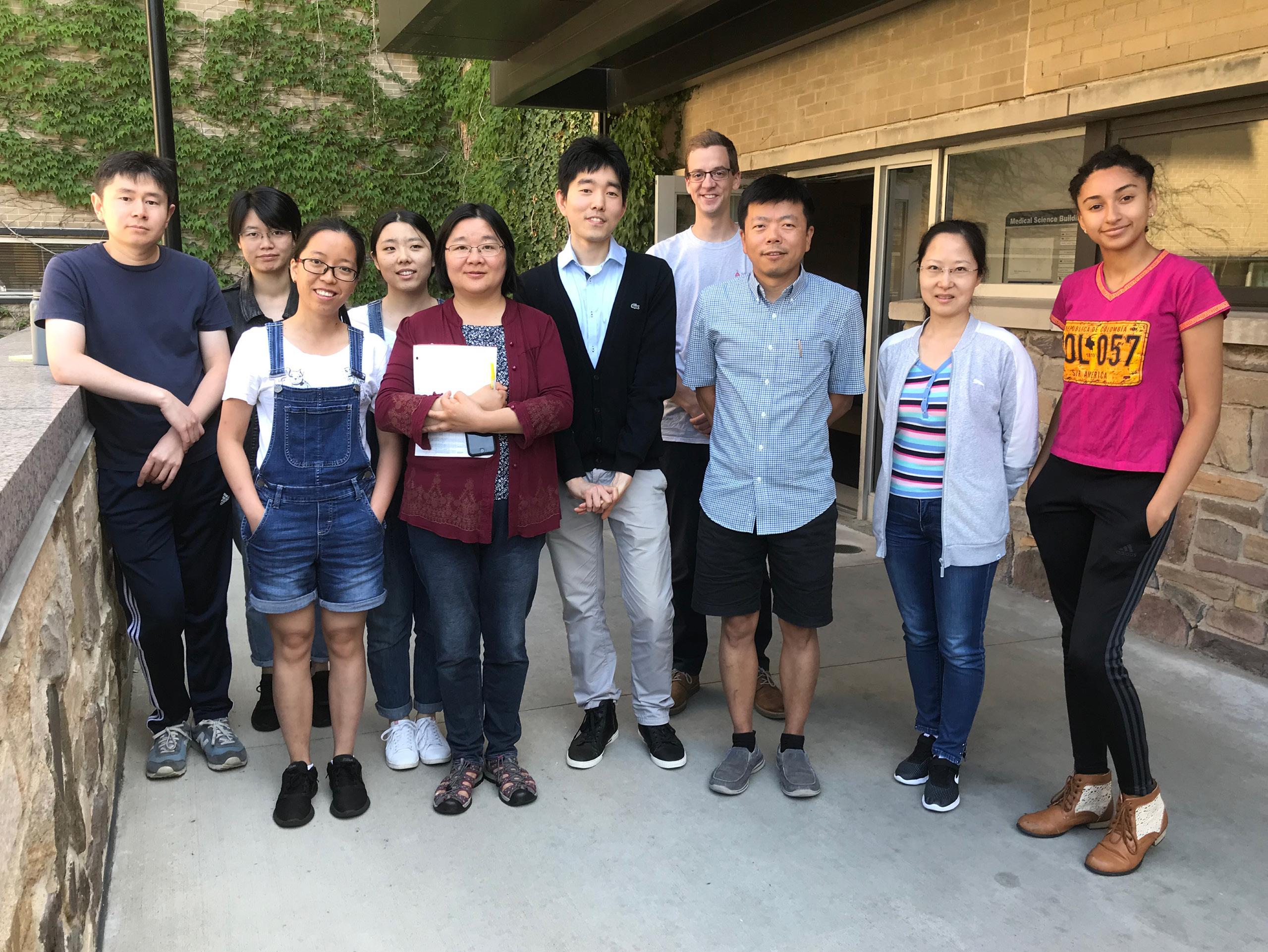

One of the beautiful things about academia is the transient nature of our research and educational community. Learners and young researchers come to our department from all over the country and the world for a short time to pursue a degree or receive training; trainees typically then move on to new positions and careers in science-related fields. This creates a wonderful opportunity for cultural exchange and new relationships with individuals from diverse backgrounds and experiences, which enriches our research efforts and our department community. Activities focused on attracting scholars from all walks of life are labeled as Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion efforts, but are based on the fundamental idea of providing a welcoming and supportive community for all individuals who want to pursue education and research training that we aspire to in Molecular & Integrative Physiology.