Badge of honour

Welcome to the summer edition of Goodwood Magazine, which looks forward to some of the upcoming highlights of the season and looks back on some of the historical moments that are part of Goodwood’s story –because 2023 is a year of several important anniversaries. Festival of Speed turns 30 and Revival is 25 years old, but most importantly, it is 75 years since my grandfather, Frederick Gordon Lennox, the 9th Duke, brought motor racing to Goodwood one memorable day in 1948 (p38).

As Freddie March, he was originally a mechanic and racing driver before becoming an engineer, both aeronautical and automotive – and ultimately, an impresario of motorsport. His love of cars and bikes led him to transform the perimeter road around RAF Westhampnett (a famous Battle of Britain airfield) into the Motor Circuit that we know today. Freddie succeeded in making Goodwood home to British motorsport during the sport’s most exciting and glamorous era. Ten years earlier he had reluctantly been forced to part with his Scottish inheritance, Gordon Castle, the heyday of which is captured by the wonderful old photographs in the family albums at Goodwood (p64). But despite the hardship of the post-war world, on that jubilant day in 1948 the crowds came, the engines roared, and Goodwood, long famous for equestrian excellence, became synonymous with a different kind of horsepower.

Elsewhere, on the subject of horses, we look at a study by Stubbs (p92), which has returned to Goodwood after more than two centuries away, and we salute some gloriously fashion-forward creations by designer Miss Sohee, set to debut at the Qatar Goodwood Festival (p72). Contemplating the future is as important as honouring the past – and my grandfather would doubtless have been fascinated by the conversations that take place at Nucleus, the invitation-only gathering that happens just ahead of the Festival of Speed. Great pioneers, thought leaders and CEOs from the worlds of tech, space and motorsport come together to freely discuss and debate the future of our world. Times change, and like Freddie, we aim to keep changing with them.

We look forward to welcoming you to Goodwood soon.

The front cover shows a selection of Goodwood motorsport badges from 1948-2023, photographed by Sam Armstrong

Tamsin Blanchard

Tamsin has been fashion editor of The Independent, style editor of The Observer and fashion features director of Telegraph Magazine, as well as contributing to Harper’s Bazaar USA and Tank. For us, she reflects on the changing shapes – but enduring appeal – of a straw hat in summer.

Peter Hall

Peter is one of the UK’s leading motoring journalists. As the legendary 24 Hours of Le Mans reaches its centenary, he looks back at the distinctive posters that have become such a well-loved –and highly collectible – aspect of the event, and the fascinating story they tell across the years.

Skye Sherwin

Skye writes about art for newspapers such as The Guardian and magazines ranging from Frieze and Art Review to Vanity Fair and W. For us, she spoke to the curators of a new exhibition of Andy Warhol’s lost (and now found) early textile designs.

Oliver Franklin-Wallis

Oliver is the features editor of British GQ and contributes to The New York Times, The Sunday Times and Wired. For Goodwood, his miniature schnauzer Boudica joined him in reporting on the new thinking about how we understand the psychology of dogs when we train them.

Johanna Derry Hall

Johanna’s writing on all things food-related has appeared in titles such as The Financial Times, The Telegraph, Foodism and The Evening Standard. For this issue, she spoke to apple aficionados about the future of England’s endangered heritage apples.

Sam Armstrong

Sam’s impactful photography has appeared in Esquire, Vanity Fair , as well as in campaigns for brands such as Sony and Cos. For our cover image, he photographed a selection of Goodwood badges, chosen from a collection that spans 75 years of motorsport on the Estate.

Editors

Gill Morgan

James Collard

Deputy editor

Sophy Grimshaw

catherine.peel@goodwood.com

Art director

Vanessa Arnaud

Sub-editor Damon Syson

Images curator Jonathan Wilson

Images archivist Max Carter

Project director

Sarah Glyde

Goodwood Magazine is published on behalf of The Goodwood Estate Company Ltd, Chichester, West Sussex PO18 0PX, by Uncommonly Ltd, 30-32 Tabard Street, London, SE1 4JU. For enquiries regarding Uncommonly, contact Sarah Glyde: sarah@uncommonly.co.uk

© Copyright 2023 Uncommonly Ltd. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced without prior permission from the publisher. While every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of the information contained in this publication, the publisher cannot accept responsibility for any errors it may contain.

Inspired by one man’s dream to create the ultimate sportscar. Together we will colour the next 75 years.

variations in weather,

may

reflect

Porsche 911 Turbo S official WLTP combined fuel consumption 23.0-23.5 mpg, WLTP CO₂ combined emissions 278-271 g/km. Figures shown are for comparability purposes only and not real life driving conditions, which will depend upon a number of factors including any accessories fitted, topography and road conditions, driving styles, vehicle load and condition.23 Time for a change

Drumroll… it’s Rolex’s brandnew Cosmograph Daytona

12 Contacts

Frank Herrmann’s photos from the set of The Saint, 1962

14 Life in the fast lane

Remembering pioneering motorist and aviator Dorothy Levitt, whose life story is as tragic as it is extraordinary

16 Carré on

Keep it classic with the new silk riding scarf from Hermès

18 Crunch time

British apples are under threat from rising temperatures and non-native varieties

20 Source material

Tracing Pop Art’s roots in a new exhibition of Andy Warhol’s early textile designs

24 Not your common or garden shed

The legendary Tyrrell workshop has a new home

26 Get shorty

How to wear a shorts suit and not look like a schoolboy

28 Hounds of love

Introducing a charming new book of rescue dog portraits

30 Brimming with style

How the Panama hat became the ultimate sartorial go-to for stylish summer heads

32 Long way round

The marvellous King Charles III England Coast Path is approaching completion

34 Star vehicle

And the next lot is… Peter Sellers’ beloved Aston Martin DB4GT, as seen on screen

37 Goodwood 75

As the Goodwood Motor Circuit prepares to celebrate its 75th birthday, we present a special section on its unique place in automotive history

38 Golden years

A look back at the surprisingly low-key inaugural race meeting at Goodwood, which heralded the beginning of a glorious era in British motorsport

44 Personal bests

The Duke of Richmond recalls some of the most memorable and thrilling moments in the history of the Goodwood Motor Circuit

46 The road ahead

A glimpse into the future courtesy of Festival of Speed’s Nucleus summit, dubbed “the automotive Davos”

72 Miss Sohee in the house

Meet Sohee Park, the Koreanborn, London-based designer who is fashion’s rising star

78 The new space age

Why the current crop of rocket launches could offer myriad benefits for the human race

84 Racing colours

A look back at some of the unforgettable promotional posters for Le Mans – now coveted collector’s items

92 This sporting life

How an oil study by Stubbs has returned to Goodwood after an absence of 260 years

52 Gently does it

Badly behaved pooch? Why not try the new empathetic approach to training your dog

56 Made in the shade

From race days to garden parties, your summer wardrobe isn’t complete without a chic Panama or floppy-brimmed sunhat

64 Gordon Castle revisited

We flick through the Gordon Lennox family albums to reveal the fascinating history of the Scottish connection

97 Calendar

The unmissable events at Goodwood this summer, including the Qatar Goodwood Festival

104 Lap of honour

Alice Temperley, designer of the silks for this year’s Markel Magnolia Cup, on practical style and impractical cars

Long after the crowds depart, some objects hold a kind of magic –like these goggles, which were worn by Frederick Gordon Lennox in the years from 1929 onwards when, as Freddie March, he raced cars around Brooklands and the like. In September 1948, as the 9th Duke of Richmond, it was Freddie who brought motorsport to his ancestral estate, an anniversary we celebrate this year in “Goodwood 75”. That first meeting would inaugurate many years of legendary motor racing at Goodwood. And in turn the memories of these years would inspire Freddie’s grandson, Charles, the current Duke of Richmond, to bring this motorsport legacy to life again – first with Festival of Speed in 1993, and then five years later, exactly 50 years to the day after that first race, with the addition of Revival. So the Goodwood badges gracing the cover of this issue represent all of this automotive heritage. Think of them as a parade of champions, if you like, or souvenirs of many thrilling and happy days at Goodwood – with the promise of more to come.

In our series unearthing the contact sheets of historic photographs, we revisit the Elstree Studios set of TV series The Saint, which starred a pre-007 Roger Moore

Words by Gill Morgan

The launch of newspaper colour magazines in the 1960s heralded a golden age of photojournalism. This was the era when Don McCullin’s images of war and famine from across the world would influence political debate and when David Bailey’s portraits brought into stylish focus the rapidly changing celebrity and social zeitgeist. The Sunday Times Magazine boasted its own illustrious team of staff photographers, including the much-admired Frank Herrmann, whose assignments ranged from chronicling epoch-defining events such as the Paris ’68 riots and the Yom Kippur War to capturing the most iconic pop-cultural moments of the day. Granted extraordinarily intimate access, Herrmann would be dispatched at short notice to shoot everything from the Beatles recording Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band at Abbey Road Studios to the making of the first-ever episode of The Saint, the subject of this contact sheet.

Filming at Elstree Studios in Hertfordshire, The Saint was to become one of the most popular TV programmes of the decade, running on ITV from 1962 to 1969. The show consolidated the star power not just of its leading man, Roger Moore – playing the urbane adventurer Simon Templar – but also of his (almost) equally famous white Volvo P1800 coupé. The photographs show Moore on set, in his dressing room and opposite co-star Shirley Eaton (later to find fame as the woman who is painted gold in 1964 James Bond movie Goldfinger).

Herrmann, who came to London from Berlin with his family in 1937 and whose portrait subjects included Orson Welles, Winston Churchill and Duke Ellington, is now in his nineties and his work is held in the National Portrait Gallery collection. But beyond its interest to fans of The Saint, this contact sheet is an encapsulation in miniature of a lost era of photography, from the stamp bearing the name of the long-closed camera equipment shop on Baker Street, Pelling & Cross, to the un-PR-controlled nature of the images themselves. As Herrmann once said of another of his projects, “It was to be a fly-on-the-wall occasion, which was my favourite way of working, being able to observe people discreetly.” A limited-edition copy of this contact sheet is available to buy, priced £450-£750, from Pap Art, pap-art.co.uk

Pioneering motorist Dorothy Levitt set the female land speed record twice and was the first English woman to fly a plane – but her later years and untimely death remain shrouded in mystery

Words by Damon Syson

In October 1906, at the Blackpool Speed Trials, a 24-yearold secretary named Dorothy Levitt drove a 90hp sixcylinder Napier motor car to 90.99mph. In doing so, she broke the women’s land speed record that she herself had set the previous year, earning herself the soubriquet “the fastest girl on earth”. Things might have ended very differently that day, however. As she later recalled, matter-of-factly, “The front part of the bonnet became loose, which could have blown back and beheaded me.”

A daredevil driver who rose from humble origins to become an It Girl of Edwardian society, Levitt is one of motoring’s most enigmatic heroines. Last year, to mark the centenary of her death, motor enthusiast and writer Michael W Barton published a biography entitled Fast Lady. In the course of his research, it soon became clear that much of what is known about Levitt is patently untrue, in particular the suggestion that she came from aristocratic stock.

In reality, she was born Elizabeth Levi, in 1882 in Hackney, the daughter of a jeweller turned tea trader. “She was born into a lower-middle-class Jewish family in the East End of London,” says Barton. “At that time, she would have been expected to marry a boy from her community, produce children and support her husband in his work. But Dorothy did none of this. Instead, she went out and got a job.”

Records show that in 1900 the 18-year-old Levitt was hired as a typist by automotive entrepreneur Selwyn Edge, who, it is believed, also became her lover. Edge held the exclusive British licence to sell De Dion-Bouton, Gladiator, Clément-Panhard and Napier cars, and was looking to expand his market. In Europe he had seen aristocratic women like Camille du Gast excel in the nascent sport of motor racing, and he realised that in his pretty and self-confident new secretary he had someone who could be moulded into a British version of du Gast – thus demonstrating to potential women drivers that there was nothing to be afraid of.

Already an intrepid cyclist, Levitt turned out to be a natural behind the wheel, and Edge was surprised to discover that she also understood how automobiles worked. “She couldn’t just drive cars, she could fix them, too,” says Barton.

An early virtuoso in the art of publicity and selfpromotion, Edge set about reinventing Levitt as a wellheeled country girl who had swapped the adrenaline rush of riding to hounds for the high-octane thrills of motoring. At the time, women drivers were invariably the wives and daughters of wealthy men. These elite pioneers formed an organisation called the Ladies Automobile Club. Levitt –regrettably non-U – was never accepted as a member.

Undaunted, she found other ways to make her mark. Being attractive, stylish, fearless and fun meant that she was soon hitting the headlines not just for her driving exploits but also for her chic outfits and eccentric tales. Her Pomeranian dog, Dodo, accompanied her everywhere – even riding shotgun while she was racing. Dodo had been presented to her as a gift during a sojourn in Paris. In order to smuggle him back to England, she admitted she had drugged the dog and hidden him in a toolbox.

Not content with making a splash in the automotive world, in 1903 Levitt also made a name for herself in motor yachting, winning trophies in County Cork, Normandy and the Isle of Wight, where, during Cowes Regatta Week, she caught the eye of King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra, to whom she was presented.

The subsequent years were a flurry of headlinegenerating activity. In March 1905, she drove an 8hp De Dion-Bouton from London to Liverpool and back – 410 miles – setting the record for “the longest drive achieved by a lady driver”. In July of the same year, she set the first women’s land speed record at the inaugural Brighton Speed Trials, taking an 80hp Napier to 79.75 mph. She would of course break this record the following year in Blackpool.

Levitt’s gifts were not solely automotive. She was an accomplished writer who produced a regular motoring column in The Graphic newspaper. She wrote a book, The Woman and the Car, dispensing advice on everything from changing spark plugs to practical driving attire. And she also effectively invented the rear-view mirror by advising female drivers to carry a small compact with which to check the road behind. Less sage, perhaps, was her insistence that women travelling alone should stow a gun in the glove compartment. A Colt Automatic, she wrote, was ideal for ladies because of its minimal recoil.

The fun couldn’t last for ever. Eventually the male racing establishment froze Levitt out before she’d even had the opportunity to test her mettle on a motor circuit. In 1907, she was entered for the very first race at the newly opened Brooklands track, but at the eleventh hour the rules were changed, making her no longer eligible. And by the close of 1908 Selwyn Edge’s interest had waned in motor racing and also, it seems, in Levitt. With no funding and no car, her career was effectively snuffed out.

Instead, Levitt poured her energies into aviation. She travelled to France to train as a pilot and in 1910 became the first recorded English woman to fly a plane. In the same year, she received an inheritance from her uncle, which she immediately put down as a deposit on a Farman biplane. “It was a step too far,” says Barton. “Aviation was just too dangerous and too expensive. She couldn’t afford the remaining payments on the plane, she no longer had a job, and she had burned her bridges with her parents.”

Little is known about the last 12 years of Levitt’s life. According to official records, her death in 1922, at the age of 40, was the result of an overdose of morphine while she was suffering from measles and heart disease. Barton believes her final decade involved a tragic fall from grace, which culminated in her arrest, in 1920, in one of the many illegal gambling dens, known as “spielers”, that had sprung up in the capital. The purpose of women in these shady establishments was twofold: to keep the punters gambling and to sell them cocaine, the use of which was rife in London’s demi-monde at the time.

“There’s no doubt Dorothy had descended into a certain lifestyle,” says Barton. “The characters arrested with her in the spieler were associates of notorious ‘night club queen’ Kate Meyrick – the inspiration for Ma Mayfield in Brideshead Revisited. Two years later she died, penniless, in a grotty flat in Upper Baker Street.”

Levitt had always wanted to be buried overlooking the sea, and her sister, with whom she’d stayed in touch, fulfilled her wish. Her grave lies in the Meadow View cemetery in Brighton. Fittingly, perhaps, the gravestone records her age as 39, when she was in fact 40. An enigma to the end.

“Fast Lady: The Extraordinary Adventures of Miss Dorothy Levitt” is available from butterfieldpress.co.uk at £40 including UK postage and packing.

The latest silk riding scarf by Hermès reminds us that however you choose to wear it, the carré is always a shortcut to chic

Words by Kim ParkerEffortlessly glamorous and timelessly elegant, the silk scarf has been a quintessential wardrobe staple for almost a century. And one house has elevated these luxurious accessories to almost legendary status: Hermès. Ever since Robert Dumas, a member of the Hermès clan, introduced the maison’s first silk scarf in 1937 – it was printed with horse-drawn omnibuses and christened the carré because of its square shape – they have adorned the heads and necks of fashion plates and First Ladies alike. Jackie Kennedy Onassis and Brigitte Bardot liked to protect their coiffures with their carrés, while the late Queen rarely went riding without one (her favourite, featuring a design dedicated to Buckingham Palace’s stables, was laid across the saddle of her beloved pony, Emma, during Her Majesty’s funeral procession last autumn). Grace Kelly once fashioned her carré into an impromptu sling after injuring her arm in 1959. Meanwhile, Audrey Hepburn wore hers knotted in a variety of different ways, famously declaring: “When I wear a silk scarf, I never feel so definitely like a woman, a beautiful woman.” Perhaps owing to its blank canvas-like quality, the carré has also been used to showcase Hermès’ collaborations with artists such as Alice Shirley, Ugo Gattoni and Virginie Jamin. For spring/summer 2023, the house has recruited the Greek artist Elias Kafouros, whose puzzle-like work draws on inspirations as diverse as pop culture, Renaissance paintings and Buddhist meditation mandalas. Available in seven different colourways, Kafouros’ whimsical new “Chevaloscope” carré (pictured above) features 16 illustrated horse heads presented on “paper” squares, as if torn from his sketchbook (priced at £415, it’s available from hermes.com). Each horse’s profile is constructed from an array of leisure activities, including musical instruments, sewing tools, and even a hot air balloon. As for the best way to wear it, take a leaf from this season’s catwalks and twist it into a skinny neck scarf, channelling the rock-and-roll insouciance of Kate Moss or Mick Jagger. It looks as chic with a race-day dress as it does with a T-shirt and jeans.

Our masterpiece has evolved. From its spellbinding new Starlight Headlights to the visually striking Dynamic Wheels, Phantom Series II is uncompromising and non-conformist in its pursuit of excellence. Nuances of perfection. Discover Phantom Series II. © Copyright Rolls-Royce Motor Cars Limited 2023. The Rolls-Royce name and logo are registered trademarks.

Faced with rising temperatures and competition from non-native varieties, the British heritage apples we once took for granted are now under threat

Words by Johanna Derry HallThe tight round form of a Cox’s Orange Pippin, the pleasing brown skin of an Egremont Russet, the heft of a Bramley – most of us will have encountered these British heritage apples, if not in a supermarket, then perhaps at a farm shop or local greengrocer. Around a third of the world’s 7,500 apple varieties originated in Britain. “We have, or rather we had, the perfect climate for growing apples,” says Caroline Ball, author of Heritage Apples (Bodleian Library).

For centuries, farmers, gardeners and hobbyists grafted and grew varieties perfectly suited to their local weather and soil, giving them names to chew on: Acklam Russet, Devonshire Quarrenden, Laxton’s Superb. Some were found to be perfect for a particular dish: the Blenheim Orange, for example, cooks to a stiff puree ideal for making apple charlotte. Today, the UK’s National Fruit Collection at Brogdale Farm in Kent hosts 2,131 varieties, but many of these are now under threat. “Apples need cold as well as sunshine and heat,” says Ball. “Around 1,000 hours of not necessarily freezing but below fridge temperature weather. If they don’t get this, they don’t fruit well.”

This is one of the reasons why the biggest-selling apples today –Braeburn, Pink Lady, Gala and Jazz – were cultivated in either Australia or New Zealand. They need fewer chill hours, making them more suitable for a climate with rising temperatures.

It’s not the first time heritage apples have been threatened. This year marks the 140th anniversary of the National Apple Congress when, concerned by the influx of imported American apples, the Royal Horticultural Society asked British growers to send in an example of their own varieties. “They were overwhelmed with responses,” says Ball. “They tested them and drew up a list of the top 60 eating apples and the top 60 cooking varieties. Sadly, those that didn’t make the lists lost ground, as people stopped growing them.”

So what makes a “good” apple? Worldwide Fruit represents the UK’s largest apple-growing co-operative. As its technical and procurement director Tony Harding explains, growers now look for consistency from one year to the next. Crispness is paramount, as “soft apples are a real turn-off”. They should have a flavour “that’s not too tart and not too sweet” and a light texture: “They need to be easy to chew.” Lastly, they have to look good: “Modern apples tend to be red.”

Ball points out that apples are a particularly evocative fruit when it comes to the English language: “Someone could be described as being ‘rotten to the core’. You might talk about ‘an apple that didn’t fall far from the tree’, or ‘the apple of one’s eye’.” This ancient fruit also marks our seasons and festivities like no other, from bobbing apples at Halloween to regional variations of the apple wassail, which in Somerset sees the last of the mulled cider ceremonially offered to the Apple Tree Man, a spirit said to inhabit the oldest tree in an orchard.

For now, we still hold on to the legacy of breeding programmes that produced, for example, the Golden Pippin at Parham House (just down the road from Goodwood in West Sussex), and dates such as Apple Day in October, which celebrate our native fruit varieties – and the wildlife and biodiversity of orchards. “Visit any farm shop and you’ll find an abundance of local apples,” says Ball. “Once you try them, it’s quite a revelation. But if we don’t buy them, they will disappear.”

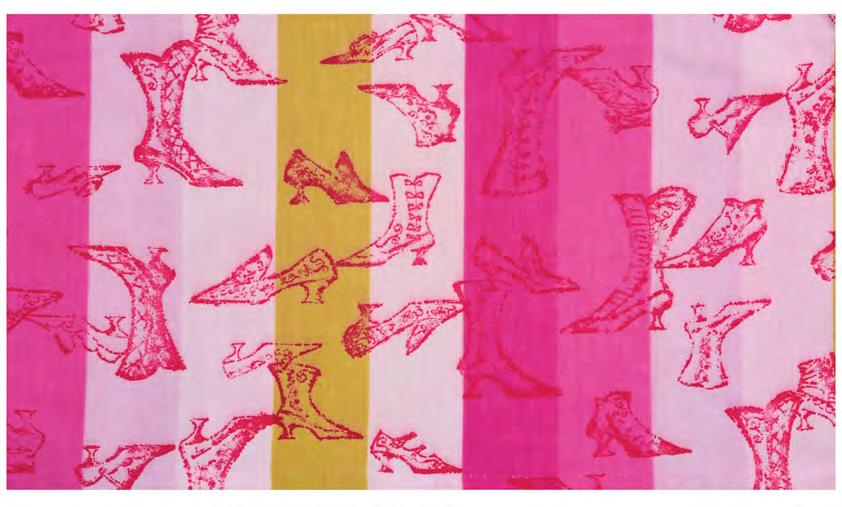

The textiles Andy Warhol created in the 1950s, when he was an up-and-coming commercial illustrator in New York, bear many hallmarks of the Pop vision that would make him the most influential artist in the world. Repeating lines of toffee apples come in clashing sugar-rush pink and scarlet, while ice cream is chocolate brown, blood orange and teal, and stacked in phallic scoops. Buttons pop in primary hues. Even luggage tags can become fodder for an eye-catching pattern. In these “novelty fabrics”, as they were then called, everyday consumer totems are transformed in colours that practically glow.

Perhaps the most surprising thing about the selection unearthed by curators Geoff Rayner and Richard Chamberlain for the exhibition Andy Warhol: The Textiles at London’s Fashion and Textile Museum, is that these early works are so little known. After all, the textile industry’s endlessly reproducible, repetitiously patterned prints would seem to offer an ideal medium for the Pop Art maverick’s iconic screen prints of movie stars and soup cans, and clothing was a cultural form he was particularly drawn to. “Fashion is more art than art is,” was one of Warhol’s declarations.

“Many but not all of his textile designs were sold anonymously,” explains co-curator Geoff Rayner. “Until recently, much of what he created has been left somewhat lost and untraced. So it has been really rewarding to slowly piece together this whole part of his oeuvre that has been eclipsed.”

In the 1950s, Warhol made a name for himself as a hardworking and adaptable commercial fashion illustrator, selling his uncredited designs for the clothing industry through agents and other contacts. Those included in this exhibition often demonstrate links with his wider work. His best-known illustrations from that decade, for instance, were part of an award-winning campaign that set out to revive the flagging I Miller shoe manufacturer and, in the process, sparked Warhol’s lifelong footwear fetish. As a fine artist, meanwhile, he began channelling the personalities of people he admired – from Diana Vreeland to Mae West – into whimsical drawings of fantastical gold shoes. Here, his love of footwear can be seen in the vibrant blouse material he created for Jayson Classics depicting elegant pink boots and shoes.

The fabric designs are highly distinctive in other ways, too. “Warhol used a blotted black ink or broken outline throughout his commercial art period, up to around 1962 or 1963,” says co-curator Richard Chamberlain. “He applied Dr Ph Martin’s aniline dyes to colour his designs, which gave them an incredibly bright, almost illuminated quality. Over and above everything, his droll sense of humour and his idiosyncratic take on subjects make them stand out from the mass of other fabrics from the period.”

In one complex, rhythmic design in lime green, pink and yellow, harlequins ride horses and perform somersaults. It speaks to a world of childlike wonder that feels quite different from Warhol’s well-known later consumer motifs like Coke bottles and Brillo pad boxes. Whether it is a dress with a print of brilliantly coloured flags or the desserts the famously sweettoothed artist coveted, these textiles promise plenty of insights into both his personality and the formation of his ideas. As the curators say, “They’re an essential ingredient in the whole Warhol picture.”

Andy Warhol: The Textiles is at the Fashion and Textile Museum, London until 10 September, fashiontextilemuseum.org

The latest evolution of Rolex’s iconic Daytona may not look radically different, but it hides some major enhancements and – in the case of the platinum version – one truly revolutionary feature

Words by Timothy BarberIt can be hard to separate the mystique that surrounds the Rolex Cosmograph Daytona, which turns 60 this year, from the watch itself. Probably the most celebrated and sought-after wristwatch of any kind, new or vintage, it is a sort of “chosen one” among sports watches. Anointed by the movie star Paul Newman, venerated by auction houses and produced in a plethora of styles down the years, it remains the archetypal example of the automotive chronograph, and – not unimportantly – the enduring symbol of Rolex’s nine-decade association with motorsport. The glamour, history and drama of the racetrack seem bound up in its robust but ageless style, even though in what you’d consider its heyday it was a notably slow seller. Nowadays, that only adds to its stratospheric allure.

As the Daytona enters its seventh decade, Rolex has performed a rare overhaul of its icon – not that you’d necessarily notice at first glance. The lugs are slightly more slender and graceful, the dial graphics have been minutely tweaked. But as any dedicated watch expert will point out, as with a car, looks only get you so far in watches. It’s the engineering of the movement – in essence, what’s under the bonnet – that separates excellence from mere competence, and the stuff under the bonnet of the Daytona is now significantly upgraded.

The watch’s new movement, Calibre 4131, takes advantage of Rolex’s many recent innovations. These include the Chronergy escapement, the regulating mechanism designed for high energy efficiency, ensuring an elongated power reserve of 72 hours; and the use of high-tech materials optimised for magnetic resistance and shock-proofing. What’s more, on the platinum version, known for its ice-blue dial and brown ceramic bezel, the bonnet has been left open. Displaying watch movements has been a trend forcefully resisted by Rolex, but with the most prestigious model in its flagship line, the Crown clearly felt it was worth breaking its own rule with its first-ever exhibition case back. Collectors and auctioneers will most certainly agree. To enquire about the Oyster Perpetual Cosmograph Daytona, please contact Wakefields, Horsham.

You can be absolutely sure that no one will ever repeat what Ken Tyrrell achieved in motorsport. Never again will a timber merchant succeed in building a better car than McLaren or Ferrari. Few can compete in Formula One, let alone on a shoestring, and to do so from a rickety old shed in a lumberyard near Ockham, Surrey, is arguably one of the most remarkable feats in the history of professional sports.

Chopper, as Tyrrell was affectionately known, built the first iteration of the now legendary Tyrrell shed in 1959, the year he stopped driving. He and a small team of likeminded enthusiasts began using the shed as a workshop in which to tinker with various Formula Three cars. Having found success in this division, they moved up to Formula Two, signed John Surtees and Jacky Ickx, and made the shed a little bigger. Then, in 1963, Tyrrell convinced a young Scottish racer by the name of Jackie Stewart to join the fold.

“The first time I visited the shed, I just remember there being woodworking tools and machinery everywhere,” says Stewart. “Other teams spent fortunes on very elaborate units, but Ken didn’t see any logic in that. We might have had a wooden hut but we certainly didn’t have wooden people. Ours were incredible engineers who were more than happy to be working in that shed.”

As the team progressed and the results improved, so did the shed. “By the time we made it to Formula One, the shed was part of the family,” Stewart laughs. “It continued to get gradually bigger, and our equipment became more and more state of the art, but it was always just a wooden shed.”

What did the competition make of Tyrrell’s eccentric HQ?

“They just thought we were being British,” grins Stewart. “He’d say, ‘I don’t need a fancy building, I have everything I need in there to build a Formula One car, and not only that, a winning Formula One car.’”

And of course, he did. Jackie Stewart won the Drivers’ Championship in 1969, 1971 and 1973, first in Tyrrell’s Matra MS80, then in the team’s own car, the Tyrrell 003. With the latter, the team also took the Constructors’ Championship in 1971, winning it again in 1973 with the Tyrrell 006.

Stewart retired from racing that same year, but despite persevering until 1997, the Tyrrell team would never repeat their success. Over time, the paint began peeling from the shed’s iconic blue doors, moss grew on the roof and the windows were boarded up. For years there was talk of dismantling the shed and reassembling it at the Brooklands Museum, and it might even have ended up in Detroit’s Henry Ford Museum. But happily, it’s coming to Goodwood.

“That shed is a unique piece of motorsport history,” says Stewart. “I thought it was a scandal that it wasn’t being preserved as an artefact. So I’m delighted that The Duke of Richmond is helping to give it a new home. Goodwood, with its own place in motorsport history, is the best place for it.” The Tyrrell shed will be rebuilt this summer on the Hurricane Lawn at the Goodwood Motor Circuit.

While other Formula One teams worked from state-of-the-art facilities, Ken Tyrrell’s HQ was a humble outbuilding. Now the legendary Tyrrell shed has found a new home at Goodwood

Words by Alex Moore

Shorts needn’t be casual, when teamed with blazers – or even as part of a shorts suit. But to avoid resembling an overgrown schoolboy, it’s important to know how to style this look

Words by Josh Sims

Words by Josh Sims

When the invitation comes to wear formal attire to a high summer event, one’s heart can sink a little. Sweatiness and discomfort will, it seems, be the price paid for fulfilling an otherwise arbitrary rule of dress. Unless, that is, your tailored look involves shorts. Think of it as sartorial smarts on top, poolside cool down below.

Admittedly, like the platform sneaker or the sleeveless hoodie, at first this look somehow seems to lack internal logic: how can your head need covering but, simultaneously, it be desirable to expose your arms? And as any physicist will tell you, two objects with mass cannot occupy the same space at the same time. So, it might seem that smart tailoring and bared calves are mutually exclusive.

But with the notion of the suit in flux anyway – thanks to a breakdown in office dress-codes, remote working, the trend for wearing “separates”, and so on – designers, from Thom Browne to Han Kjøbenhavn, Zegna to Fendi, are again exploring the potential of what is sometimes referred to as a “half suit”. Gucci even has a three-piece version.

“This is a playful, fun look that’s more about dressing up shorts than it is about dressing down tailoring,” argues menswear consultant Chris Modoo, who styled the look for British brand Alan Paine. “The opportunities to wear it are slim, but it works for very specific, high summer, outdoor events. You might think nobody over 25 should wear this look, but I actually think the older you are the easier it is to pull off –because you’re less likely to be mistaken for a schoolboy.”

And therein lies the need for caution. This look works if you’re, say, rapper, singer and fashion designer Pharrell Williams, for whom a tuxedo version has become a red-carpet statement. But for many a grown man there’s a strong risk of looking like Angus Young, AC/DC’s guitarist, who took to wearing his signature shorts and blazer combo on stage: a heavy metal, man-sized Just William. “The crowd’s first reaction was… all mouths open,” Young once recalled.

And yet it’s hard to deny that the shorts plus blazer look is a solution to a problem, in keeping with the idea that functionality in menswear need not just mean tough fabrics and plenty of pockets. Indeed, this isn’t the first time the style has crept into fashionability: the likes of Junya Watanabe, Raf Simons and Richard James all dabbled with it a decade ago. Might it stick this time, driving men to embrace that leg press machine at the gym at last?

The secret is to dial down anything that suggests formality. Wear a casual shirt or T-shirt. Keep the footwear casual: simple plimsolls, boat shoes or driving shoes. Make sure the shorts are crisp but more loose than fitted, and that they end just a few inches above the knee. The jacket, advises Modoo, is best in cotton or linen, shorter in length and with a soft, unstructured shoulder. Consider taking the separates route and wearing a jacket and shorts in complementary but different shades.

“You can wear shorts in a more formal way and look great – just look at the Bermudans,” says designer Oliver Spencer, who has matching shirt and shorts designs in his latest collection, though he draws the line there. “You can take it mega-preppy, or maybe a bit safari suit. But wearing shorts with a tailored jacket? I think you have to be a bit brave for that.”

As for the colour, we would advise summertime pastels rather than chalk stripes. After all, nobody wants to see their bank manager in shorts.

Sally Muir’s portraits of dogs, including her new book of paintings depicting rescued canines, subtly capture her subjects’ character and charisma

Words by Sophy Grimshaw“Dogs are not an appendage to us – you’ve got to respect them as their own creature, and that’s how I try and paint them,” says the artist Sally Muir, whose quietly dignified portraits of dogs are collected in her books, including her newest, Rescue Dogs, and before that, Old Dogs. “I take them seriously as a subject. I’m always having to say to people: ‘I paint dogs, but not in the way you’re thinking!’” she laughs. “‘Dog art’ has a bad name somehow.”

The portraits in Rescue Dogs were painted over the course of two years. “I asked on social media for people to send me photos of their rescue dogs, and they always came with a tale. A lot of the dogs came into people’s lives at times when they were needed, whatever it is that dogs bring. It was touching.” This is the only one of Muir’s books to have annotating text, “because rescue dogs always come with a story”.

The nature of dog portraiture is that it’s often not practical, nor kind, to make your subject sit for you at length. Muir, who lives and works in Bath, does sometimes draw from life, with her whippet, Peggy, among her preferred models: “She sleeps all day long, so she’s perfect.” But her usual method is to paint from photographs. “It’s not so much about the quality of the photograph, but I do need to have a lot of angles.” This way of working added a logistical challenge to Rescue Dogs, as Muir had to keep track of hundreds of photos with names and contact details, to know which were of the same dog.

There was also a visual balance to strike, “of not having dogs that looked too similar”. Some breeds are rehomed in greater numbers than others, such as retired greyhounds, and Muir has a longstanding interest in Spanish galgo dogs, which are greyhound-like. “They are abandoned in huge quantities at the end of the hunting season, so you see them all over Spain.” She collaborates with a charity in Murcia, Galgos Del Sol, and her striking group portraits are drawn from life on a farm where rescued galgo hounds are cared for.

Muir began her creative career not as a painter, but as knitwear designer, founding the label Warm & Wonderful with partner Joanna Osborne in Covent Garden in 1979. Their “black sheep” jumper – a lone black sheep among white, on a jolly red background – was famously worn by Princess Diana.

“The first we knew was when we saw it on the front of a newspaper, which was so exciting,” remembers Muir. “I think in retrospect people read too much into it. She obviously thought it was a bit of a laugh. I don’t think she was sending a ‘get me out of here’ message.” The jumper, which David Bowie also purchased, was worn by Emma Corrin in The Crown and has now been reissued. “It’s amazing how it’s had this second life.”

She adds, “To be a knitwear designer, and to paint dogs, both things are slightly low in status, I suppose. Some people are horrified when you say you paint dogs. Which is good, actually, because it has given me the freedom to do whatever I want.”

The Panama hat is one of menswear’s hardy perennials – a classic go-to that adds a touch of panache to your look and is perfect for social occasions throughout the warmer months, from glamorous garden parties to the Qatar Goodwood Festival

WordsFor something that can look so quintessentially English, the Panama hat has exotic roots, emerging in central America in the 16th century – though in Ecuador rather than Panama. Here it was discovered that the local paja toquilla plant was the perfect raw material for light but sturdy headgear that offered protection from the searing heat. In fact for much of the 19th century the hat was known internationally as a toquilla – the namechange is generally attributed to the fact that US president Theodore Roosevelt was photographed wearing one during a visit to Panama.

In Europe, it was crowned heads that helped make the hat fashionable. During the 1850s, a Frenchman returning from Ecuador presented one to Napoleon III, while in England the Panama was popularised by King Edward VII, who wanted to find something a little more comfortable than a morning suit and top hat for the races at Goodwood.

Today, the hallmark of a truly great Panama hat remains its ability to travel well – and the best way to ensure that happens is by investing in a top-notch hand-made model. Goodwood’s Panamas are made by the venerable London hatmakers Christys’, who shape and block them in the UK, working from cones weaved in the traditional manner in Ecuador. They’re made to last, which means your Panama won’t just protect you from the summer sun this season – it’ll be around to do the same 20 years from now. So if you want to get ahead, get a hat.

The Goodwood Panama hat is available from shop.goodwood.com/ collections/panama-hats. For more summer hat inspiration, turn to page 56.

The Hennessey Venom F5 Roadster is a bespoke mid-engine carbon-fiber hypercar engineered to exceed 300 mph. Handcrafted in Texas, the two-seater boasts a custom 6.6-liter, twin-turbocharged ‘Fury’ V8 producing a phenomenal 1,817 horsepower and 1,192 lb-ft of torque — it is the most powerful Roadster in the world, delivering an unrivaled open-air driving experience. Exclusiveness is assured by production limited to just 30 personalized examples. ©

Decades in the making, the England Coast Path – now renamed the “King Charles III England Coast Path” – will soon become the longest coastal walking route in the world

Words by Gill Morgan

Words by Gill Morgan

When the England Coast Path is officially completed next year, it will be a walking route fit for a king. Just days before the Coronation in May, the long-held dream to create a continuous walkable footpath around the English coast inched a little closer and was officially renamed the King Charles III England Coast Path in recognition of the new King’s love of the natural world and of walking in particular.

The project has been decades in the making, driven by the Ramblers Association (known simply as the Ramblers) and delivered by Natural England. When the final sections are opened at the end of 2024, the path will stretch for 2,700 miles, making it the longest coastal walking route in the world. From the vast sandy beaches and castles of Northumberland to the shingle moonscape of Dungeness, from the rugged beauty of Devon and Cornwall to the magnificent chalk cliffs of Kent and Sussex, the English coastline is one of the most varied and beautiful in the world – and now we will all be able to enjoy it even more.

“It captures the imagination,” says Kate Condo of the Ramblers, which has campaigned for the coastal path for many years. “Coastal walking has always been popular, and obviously there are some very well-established trails like the South West Coast Path. But this will help to open up lots of other stretches of our coast.”

The mission to create a continuous coastal route began more than two decades ago when the Countryside and Rights of Way Act 2000 was passed. It granted public access to land mapped as “open country”, defined as “mountain, moor, heath and down, or registered common land”. But, as Condo relates, the Essex branch of the Ramblers thought it left a gaping hole in our countryside access because, “there aren’t many mountains and moors in Essex”. They did, however, have lots of coast.

And so began many years of campaigning, culminating in the Marine and Coastal Access Act 2009, the first step towards the eventual path. Natural England was entrusted with making the path a reality, work that involves detailed planning, consultation and negotiation with local councils, landowners, nature conservation groups and businesses, to find creative solutions to tricky stretches of coastline where no clear access is in place. The goal is always to arrive at a route that stays as close as possible to the coastline, only veering inland when absolutely necessary.

The first stretch of the path was opened between Weymouth Bay and Portland Harbour in time for the sailing events of the 2012 Olympics. Over the past decade more sections have been added, including parts of the Hampshire, Sussex and Kent coasts, as well as trails in Northumberland, Cumbria, Essex and North Norfolk. The rest is on course to complete next year. The path will join the Wales Coast Path, which already covers the entire length of the Welsh coastline.

A coastal walk is a very particular pleasure: the energising salty air and everchanging skies; the roller-coaster ride of cliff path plunging down to beach and cove, then zigzagging back up again; and always the view out to sea, hinting at life beyond these shores. To walk a nation’s coast is to trace, step by step, that country’s history, topology, flora and fauna, and unique social character. Perhaps more than any other trail, a coastal route provides a new perspective and breathing space, so vital to our wellbeing. There is also surely something that appeals to the collector in us, to set out to walk all of England’s coast, even if in small chunks, over many years.

And as the Ramblers’ Kate Condo confirms, there has been a marked increase in how many of us are regularly walking for pleasure. Sport England reports that although numbers have dropped since the pandemic – when a daily walk was an essential part of life – for many the habit has stuck. And it isn’t just our own health that benefits, but struggling local communities. “The England Coast Path will open up new areas beyond the ‘honey spots’ to visitors and bring money into those local economies,” says Condo. “The path isn’t just a marketing tool, it really allows people to enjoy stretches of the coast they haven’t been able to enjoy before.”

The actor Peter Sellers once played a cheeky 1960s London gangster – and loved his Aston Martin getaway car so much, he bought it. Now, this superb DB4GT is going under the hammer at Goodwood

Words by Sophy Grimshaw“I do not sell women’s frocks in the West End, I sell ‘gowns’, mate. I’m legitimate now!” So protests Peter Sellers’ character, the gang leader Pearly Gates, to police officer ‘Nosey’ Parker in the delightfully silly 1963 comedy The Wrong Arm of the Law. The plot of the film (which also features John Le Mesurier and an uncredited cameo from a young Michael Caine) centres on an unlikely alliance of London police and thieves, teaming up against a gang of Australian criminals that has been outsmarting them all.

One of the things Sellers must have most enjoyed about making the movie was driving a 1961 Aston Martin DB4GT coupé in character as the often-fleeing Gates. When filming wrapped, the actor purchased the car from the production. The DB4GT seen in the film and subsequently owned by Sellers is now for sale once again, as a star lot in the 2023 Goodwood Festival of Speed sale (fans of the film might like to know that another DB4GT stood in for many of the high-speed scenes, while a third “stunt” DB4 performed the film’s famous flying jump over a bridge).

Sellers’ car may not have performed any acrobatics, but it did sustain one major injury during the course of the shoot, when its original 3.7-litre engine blew up. This was replaced at Aston Martin’s Newport Pagnell factory, and the substitute was a larger, 4.0-litre Lagonda Rapide, fitted in early 1963, making it the only factory-fitted 4.0-litre DB4GT engine to date. It’s a detail that would not have been lost on the actor, described by the auction house Bonhams as “a noted car collector and aficionado of luxury marques”. It is Bonhams who will be offering Sellers’ DB4GT at auction this summer at Goodwood, with an estimate of between £2,200,000 and £2,600,000.

Sellers liked to swap his luxury cars with great frequency, and he is believed to have held onto his Wrong Arm of the Law getaway car for less than a year. According to Bonhams, it was then owned by several Aston Martin enthusiasts before being totally rebuilt and repainted Goodwood Green in 2002.

“The DB4GT is arguably Aston Martin’s finest road car,” says Bonhams’ James Knight. “It’s right up there as the ultimate 1960s GT.” And what about this particular vehicle? “It’s in great condition, has a wonderful provenance, and is offered for sale from a committed Aston Martin enthusiast. It really has all the credentials to be one of the most coveted examples.” Pearly Gates would have been thrilled.

The Aston Martin DB4GT coupé owned by Peter Sellers will be on view from Thursday 13 July during the Festival of Speed sale preview, going under the hammer on 14 July.

Enjoy an adrenaline-fueled day out at Silverstone Circuit as Ferrari Racing Days returns for a scintillating weekend of Ferrari race action, track parades and displays, including F1 cars from Ferrari’s illustrious racing heritage being put through their paces on track by the F1 Clienti.

For information on the Ferrari model range please contact your nearest Official Ferrari dealer, or scan the QR for more about Ferrari Racing Days.

Exeter

Carrs Ferrari

Tel. 01392 822 080 exeter.ferraridealers.com

Solihull

Graypaul Birmingham

Tel. 0121 701 2458

birmingham.ferraridealers.com

Nottingham

Graypaul Nottingham

Tel. 0115 837 7508

nottingham.ferraridealers.com

Leeds JCT600 Leeds

Tel. 0113 824 3200 leeds.ferraridealers.com

Lyndhurst

Meridien Modena

Tel. 02380 283 404 lyndhurst.ferraridealers.com

Ferrari.com

Belfast

Charles Hurst

Tel. 0844 558 6663 belfast.ferraridealers.com

Edinburgh

Graypaul Edinburgh

Tel. 0131 629 9146 edinburgh.ferraridealers.com

Hatfield

H.R. Owen

Tel. 01707 524 093

london-hrowen.ferraridealers.com

Colchester

Jardine Colchester

Tel. 01206 848 558 colchester.ferraridealers.com

Manchester

Stratstone Manchester Tel. 01625 445 544 manchester.ferraridealers.com

Swindon

Dick Lovett Swindon

Tel. 01793 615 000 swindon.ferraridealers.com

Glasgow

Graypaul Glasgow

Tel. 0141 886 8860

glasgow.ferraridealers.com

London

H.R. Owen

Tel. 0207 341 6300

london-hrowen.ferraridealers.com

Egham

Maranello Sales

Tel. 01784 558 423

london-maranello.ferraridealers.com

September 2023 marks 75 years of Goodwood motorsport. Here, The Duke of Richmond looks back on unforgettable moments, while Ben Oliver charts the story of how it all started – and how Goodwood is contributing to the future of automotive innovation

Deep in the Sussex Downs in 1948, something was stirring. Ben Oliver looks back at Goodwood’s inaugural race meeting, which heralded the start of a glorious era in British motorsport

Look at the black-and-white photographs of the first race meeting to be held at the Goodwood Motor Circuit or watch the footage shot by the BBC and you might struggle to recognise the location. In fact, it barely looks like a motor race at all. Goodwood’s hallmark white pit building hadn’t been built, nor had the famous chicane been installed. The “paddock” found behind the pits really was just a grassy paddock in 1948: the racing cars parked on the turf before taking their turn on the track. There weren’t acres of car parks around the circuit – because the crowd of 25,000 came mainly by bus and train. The men smoked pipes and wore suits and ties, caps or trilbies, and overcoats against a September chill. The women mustered as much style as the clothing ration allowed, and families came with wicker picnic baskets. Crowd control was relaxed: there were no grandstands yet, so for a better view some spectators inched up and over the hemispherical roofs of the blister hangars, which until recently had sheltered Spitfires and Hurricanes. The others watched obediently from behind simple, cheap, post-and-wire fencing, which would not have prevented a racing car getting among the crowd should it slide off the narrow, dusty track to which the fencing was set perilously close.

It was clearly a very different time, but the start of a new era. It seems almost too obvious to state but in September 1948 the cataclysm of World War II still distorted almost every aspect of British life. Post-war austerity was at its bleakest. Rationing was becoming tighter rather than relenting. Crop failures had seen bread and potatoes added to the ration list after the war. Less than a year before the Goodwood circuit opened, Hugh Gaitskell, then the Minister for Fuel and Power, cut the personal petrol ration completely, restricting it to official or essential use only, in an attempt to kill off the black market and avoid having to spend the country’s limited foreign currency reserves on oil imports.

“After November, all private motoring in this odd, sad little country is apparently to come to an end,” Motor Sport magazine lamented, before hinting that motorists would “find various means, according to their natures, of sustaining their motoring enthusiasm” – a clear hint that they would still resort to the black market. By June 1948, Gaitskell had relented and allowed drivers around 90 miles worth of petrol each month, a third of the previous ration. “Those who have been obliged to lay up their cars or motorcycles may bring them out again without excessive cost for a modest mileage,” he told the Commons. In response, Churchill bemoaned the “immense disturbance and heavy internal loss to this country” of Labour’s temporary ban.

But at Goodwood they got ready to go racing. The war at least provided the real estate for Britain’s new post-war circuits. RAF Westhampnett had been a Battle of Britain fighter base, later used by the USAF, built on land on the Goodwood Estate provided by Freddie, the 9th Duke of Richmond. When it was returned to him after the war it had a 2.4-mile perimeter road that his friend, Squadron Leader Tony Gaze, suggested might be repurposed as a racetrack. The Duke – a talented engineer, racer and aviator – didn’t need much persuasion.

Motorsport was beginning to reawaken from its wartime hiatus: there had been some hillclimbs and sprints, and some racing at an impromptu airfield circuit in Cambridgeshire. But of the pre-war circuits, Brooklands was still being used for aircraft production and Donington for the storage of military vehicles, so the first race meeting held at the Duke’s new Goodwood circuit on September 18 was also the first at any permanent motorsport venue after the war.

The earliest incarnation of what would become one of the world’s great circuits was a bootstrapped affair. The road surface was repaired and that rather flimsy fence erected; there was a PA system but no leaderboard; medical provision consisted of an old Austin Six ambulance. There were trophies and £500 in prize money provided by the Daily Graphic, whose return on investment was a banner strung on wires over the start-finish line. There were eight races, all held over just three laps, with the exception of the last one, the flagship Goodwood Trophy, which was held over five.

But brief races and basic facilities didn’t deter spectators desperate for a return to racing – or any kind of entertainment – after six years of war and three of austerity. You look at the faces in the crowd and wonder what those who served had seen and what those who remained at home had endured. The sight and sound of the Maseratis, Alfas and Bugattis at Goodwood that day – “a brave splash of colour on the grey road”, as Motor Sport put it – must have seemed impossibly exciting and exotic, and a foretaste of better times to come. Nor did the tight petrol ration and races lasting less than 10 minutes deter entrants. There were over 100, including three women, in an odd variety of pre-war racing cars. And not everyone was being ground down by austerity. Prince Bira of Siam, a talented racing driver, flew into Goodwood in his private twin-engined Gemini plane with his terrier, just to spectate when his Maserati couldn’t be readied in time for the meeting.

The very first race at Goodwood – for closed, non-supercharged sports cars of up to three litres – was won by the magnificently monikered Paul de Ferranti C Pycroft in his Pycroft-Jaguar special: a pre-war Jaguar SS100 with aerodynamic bodywork of his own design. And in a race meeting packed with firsts, one of the most significant might have been hard to spot at the time. Race 5, for cars with engines under 500cc, was won in a Cooper by Stirling Craufurd Moss, who had turned 19 the day before. It was his first major victory on a circuit, beginning a close relationship with Goodwood that would last until his recent passing aged 90. The style and ease of his victory should have been a clue. Nobody could challenge him, so his father indicated from the side of the track that he should slow and preserve the car. He still won by 25 seconds.

But on that day the five-lap Goodwood Trophy drew all the attention. It predominantly featured Grand Prix cars from just before the war, when racing car design froze. So they were still the fastest and most exciting cars you could watch. Thankfully, the race lived up to expectations. Of the nine drivers, three would go on

The sight and sound of the Maseratis, Alfas and Bugattis must have seemed impossibly exciting and exotic

to win Le Mans. The tussle between them that day was short but, according to Motor Sport, “an immensely exciting race”. Reg Parnell would win: the first in a series of victories that would earn him the nickname “Emperor of Goodwood”.

Goodwood’s monopoly on British circuit racing didn’t last long. Just two weeks later the first race was held on another hastily converted wartime airfield perimeter track near the Northamptonshire village of Silverstone. Together, the new circuits were central to the revival in British motorsport after the war, which resulted in British teams dominating Formula 1 and endurance racing – and bequeathed us a motorsport industry now worth £9 billion each year. Goodwood would go on to host some of the most dramatic and glamorous racing that Britain ever saw, before beginning another life in 1993 with Festival of Speed and then in 1998 – 50 years to the day after hosting its first meeting – as the home of the Goodwood Revival.

The broader British car industry had a similar watershed just a month after racing began at Goodwood. The first post-war British Motor Show opened at Earls Court in late October and saw the debuts of some of the first modern British models not based on pre-war designs: cars as varied as the glamorous, exuberant Jaguar XK120, the humble Morris Minor and the utilitarian Land Rover, which had actually made its very first appearance at the Amsterdam show earlier in the year, so eager was Rover to get it on sale. Together, this crop of brilliant new British designs would earn muchneeded foreign currency with their export sales and establish the overseas markets that would make the UK the world’s biggest car exporter by the 1950s.

For both British motorsport and British motoring in general, 1948 was a turning point, but it wasn’t obvious at the time. The crowds left on the evening of September 18 just grateful for “the return of the real thing” as one writer described it. “The advent of the Goodwood track opens up a new era in British motor racing,” Motor Sport wrote. “Many happy meetings should be possible at this very pleasant place.”

This Portugieser Chronograph builds on the legacy of IWC’s marine deck observation watches. It is powered by the IWC-manufactured 69355 calibre, engineered for performance, robustness, and durability. The vertical arrangement of the subdials enhances readability. Because at IWC, function always comes first.

As we celebrate the 75th anniversary of motorsport at Goodwood, The Duke of Richmond shares his personal reflections on some of the most memorable, and thrilling, moments in its motor circuit history

1958

HEROES WELCOME

“I remember meeting all the great drivers of that era”

HEROES’ RETURN

“Many of those who came had raced at the circuit”

1993

THE AMERICANS ARE COMING

“‘We drive ’em like we stole ’em,’ they said”

2006

One of my very early memories is of watching the racing at the circuit with my grandfather, Freddie March, who had his little caravan at the chicane, where there was always lots of action. I remember Jean Behra crashing there – the chicane was brickwork back then, and his car ended up U-shaped.

There was always a party at the House on the Saturday evening of the Easter Weekend. I remember meeting all the great drivers of that era – Jackie Stewart, Jim Clark, Graham Hill, Roy Salvadori, Carroll Shelby – and sitting on the sofa in the library with Jo Bonnier. In 1965, in the last ever Formula One race at Goodwood, Jim and Jackie both broke the lap record, which they share to this day. My grandfather told me one day Jackie would be world champion.

In 1993, when we started Festival of Speed, I realised that lots of people still felt a deep connection with Goodwood from its earlier motorsport years. Many of those who came that year had raced at the circuit. Looking back over the past 30 years, I think of great drivers like Dan Gurney, who drove his Eagle-Weslake in 1997, Dan himself working on the engine in the paddock to cure a misfire.

A huge moment for all of us was when I finally persuaded Mercedes-Benz to bring their sensational Silver Arrows Grand Prix cars to Goodwood in 2019. A real coup was getting the Mercedes W165, which hadn’t turned a wheel since winning its only race, the Tripoli Grand Prix, in 1939.

As the Festival gained in stature we started to get great cars and drivers from America, where word of what we were doing at Goodwood was spreading fast. The NASCAR boys, led by the legendary “King” Richard Petty, who first came in 2006, really understood how to put on a show. “We drive ’em like we stole ’em,” the veteran drivers said, referring to the bootlegging days in America.

Motorcycles and bikers have always been a part of Goodwood’s racing history and in particular Valentino Rossi, who came in 2015 and was the ultimate showman. “The Doctor” rode his bike into the front hall of the House before greeting his fans from the balcony. Last year Wayne Rainey was back aboard his Grand Prix bike for the first time since the crash in 1993 that left him paralysed and ended his career, riding the Hill flanked by friends and rivals Kenny Roberts, Kevin Schwantz and Mick Doohan.

“The start of the first Revival was simply electrifying”

It has been a privilege to drive some of the sport’s greatest cars. I have driven the Festival Hill in Jacky Ickx’s Le Mans-winning Porsche Spyder 936/77, the Lotus 56 gas turbine car, Jim Hall’s incredible Chaparral 2F and the fabulous-looking Porsche 908/3. I was also trusted with the world’s most expensive car, the Uhlenhaut Mercedes-Benz 300 SLR, which sold at auction for… 135 million euros!

The first few minutes of the first Revival in 1998 were simply electrifying. As I drove my grandfather’s Bristol round the track to open the event, I saw a Spitfire heading straight at me as I approached the chicane. Flying just a few feet above the ground, Ray Hanna streaked past the pits and climbed steeply into the early morning sunshine.

A perennial hero of those early Revivals was John Surtees, champion on two wheels and four. He gave us a maestro’s masterclass in how to race a Ferrari 275 LM in the RAC TT Celebration in 2000. Starting from pole, “Big John” just drove into the distance, building a huge lead before handing over to owner David Piper. Watching him drift through St Mary’s corner, inchperfect every lap, was every enthusiast’s dream.

I treasure, too, the memory of Kenny Brack winning the Whitsun Trophy in pouring rain in Adrian Newey’s Ford GT40 in 2013, Kenny having also won the RAC TT Celebration race two years earlier.

The motorcycle racers have written their own chapters in our history, notably the great Barry Sheene, who rode his last-ever race at the Revival in 2002. We remember him every year with the Barry Sheene Memorial Trophy bike race.

Then, of course, there is Mister Goodwood himself, Sir Stirling Moss, who gave so much to both the Revival and the Festival. To see Stirling in 1994, back racing at Goodwood, where he won his first-ever race in 1948, was a truly magical moment. “Stirl” was in top form, as Le Mans winner and former F1 driver Martin Brundle observed at close quarters. “Out of Lavant corner he just drove round the outside of me,” he told us. “I thought, ‘That’s Stirling Moss.’”

The Duke of Richmond was interviewed by Rob Widdows.

Nucleus – Festival of Speed’s annual semi-secret summit – brings together leading players from the car and tech industries to discuss the future of mobility.

Ben Oliver hails the creativity and candour of the “automotive Davos”

The Goodwood Festival of Speed is now as much about the future of mobility as it is about the history of the car. The House and the Hill still reverberate to the sound of engines from the Edwardian era onwards, but the course record is now held by an electric car, and the Future Lab pavilion, where guests can mingle with humanoid robots or have their movements mimicked by artificial intelligence, is one of the Festival’s biggest draws.

Since 2015, another Goodwood event has been contributing to that future by bringing people rather than cars and tech together: the people who are remaking not only mobility, but the modern world. It isn’t publicised and is seldom discussed openly. One early delegate described it as “a one-day automotive Davos”, and it is the hottest and most exclusive ticket at the Festival of Speed.

Nucleus was the Duke of Richmond’s idea, and guests attend at his personal invitation. Each year, on the Friday of the Festival of Speed, around 30 delegates meet in the seclusion of Goodwood’s Sculpture Park to discuss the future of the car and its changing role in the new mobility. The leaders of the biggest car and technology companies attend, alongside the founders of disruptive new-mobility start-ups. Nucleus hears from those who create the technology and predict its impact; far-sighted legislators who seek to encourage as well as regulate; the financiers who fund the ideas; and an endlessly changing, surprising, diverse collection of technologists, thinkers and theorists, often from outside the world of mobility if their perspective might prove instructive.

The reinvention of mobility touches so many aspects of state and society – from the economy and technology to urban planning, ethics and the environment – that those who have the greatest influence on its future might never meet. Nucleus attempts to fix that, although many delegates say they’re lured as much by the Festival of Speed, whose old-school engines you can hear from the venue, as they are by the chance to meet their peers.

The conversation between them is creative and sometimes combative. Nucleus is held under the Chatham House Rule, by which the substance of the conversation may be reported or acted upon, but the identity of the speakers never divulged. As a result, delegates talk with often searing honesty, and express views that they might not venture in public.

The discussion is hosted and moderated by well-known broadcasters such as Krishnan Guru-Murthy and Sarah Montague, and split into three main sessions, each anchored around an interview or panel discussion followed by an open debate. Every year, the Duke of Richmond suggests a broad theme for Nucleus as well as specific topics for the debates. In previous years the event has examined the nature of disruption, the role of the state in transformative change, the uncertain progress of AI, and rising phenomena such as the metaverse and cryptocurrencies, which don’t perhaps affect mobility yet, but which might one day affect us all.

Nucleus has now been established long enough to have seen our notions of the future – automotive and otherwise – change radically. At the outset, many still thought that fully autonomous driving would arrive quickly and become widespread. The very biggest car and technology companies were actively involved in it. Their leaders came to Nucleus and admitted that making a self-driving car

1

“Dead men walking.” The young leader of a tech company didn’t pull his punches when asked to describe what he thought of the car industry CEOs attending the first Nucleus. Another delegate said that half of the established carmakers represented at the event would be out of business in five years. And yet the same carmakers will be present at Nucleus again this year, still making profits and with wholly electrified product portfolios imminent. But nobody attending, whether disruptor or established player, has ever disputed that the global car industry is undergoing the biggest change in its 130-year history.

was the hardest thing they were engaged in. Those admissions were prescient and should have been heeded, because for many it turned out to be too hard. Ford, Volkswagen and Uber, among others, have cut their self-driving projects. Those that remain, such as Alphabet’s Waymo, are making slower progress than they predicted in Nucleus’s earlier years.

Delegates are also now dealing with a world radically altered since Nucleus began; not only by technological advances but by trade wars and real ones, Covid-19, geopolitical shifts, the rewiring of globalisation, reshoring and a new focus on economic security. One very senior economist and former central banker who attended Nucleus last year described it as “economic regime change”. Speaking with, at times, troubling frankness, he described how the fundamental assumptions of the past 30 years – his entire career – have begun to crumble since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, with the long trend towards convergence and integration that began with the fall of the Berlin Wall now starting to unwind.

Since its inception, Nucleus has heard from and been excited by the enthusiasm of entrepreneurs who innovate unconstrained by precedent. But it has also revealed themes like those above: that technology sometimes fails to deliver or to find a use, and that tech doesn’t operate in a vacuum but is bound into the social and economic realities of the times. For every twentysomething wunderkind who attends there’s a CEO sitting alongside whose century-old global business has a turnover to match the GDP of major nations, and which has been through wars and energy crises and every other kind of disruption – and survived. The interplay between them is always fascinating. Somewhere between the two extremes, a more balanced view of the future of how we get around is to be found. And that view has never been more important than now, when the future seems more unpredictable than ever.

2 3 4 5

The race to create the technologies that will dominate the new mobility is rigged. Tech pioneers concentrate on creating value and building a community before they start thinking about how to monetise it, and they and their backers are prepared to fail. By contrast, the CEO of a major carmaker admitted his primary focus was “to keep the cash registers ringing”. Carmakers focus on making a return on their capital investments and they have to justify their actions to shareholders, supervisory boards and employees. Transformative change is unlikely to come from employees when their reward is just a pay rise and a promotion.

The one aspect of mobility that new entrants seem least interested in is car-making itself. It is difficult and prohibitively capital-intensive, and there are easier profits to be made in the systems and services that will enable the new mobility. But manufacturing can still be progressive and profitable, and those high barriers to entry will continue to protect the existing carmakers. Tesla’s travails in ramping up production prove how difficult mass manufacturing is. “What you guys do is really hard,” the leader of one tech giant told his car industry counterparts at Nucleus. “These are not dumb machines,” one leading tech investor agreed. “Silicon Valley always underestimates this.”

State actors have a huge role to play in the coming shift in mobility, providing the physical spaces and regulations within which autonomy and other advances can be tested. Nucleus has been addressed by everyone from elected mayors who are encouraging autonomous-driving trials in their cities to representatives of the command economies, which can overcome the regulatory hurdles to autonomy with the stroke of a pen. The outcome of this change affects far more than the enterprises pioneering or resisting it. Any major shift in mobility will have a seismic impact on how and where we all live.

Nucleus gathers the people who are defining the future of mobility, so you might expect greater clarity on what that future looks like. You’ll find little among the delegates. In fact, the only certainty is uncertainty. The early assumptions that fully autonomous driving would happen in time, or that disruptive new mobility services will continue to dominate, are constantly challenged at Nucleus, often by those who lead these enterprises. A leader of one such business told Nucleus that he thought constantly about how his business might in turn be disrupted, and how easily Google might dominate his market if it chose to.

Delegates talk with often searing honesty, and express views that they might not venture in public

Fuel consumption and emission values of Urus Performante: Fuel consumption combined 14,1 l/100km (WLTP); CO2-emissions combined 320 g/km (WLTP).

Lamborghini Birmingham

2 Wingfoot Way, Fort Dunlop, Birmingham, B24 9HF

Phone +44 (0) 121 306 4007

Lamborghini Bristol The Laurels, Cribb’s Causeway Centre, Bristol BS10 7TT

Phone +44 (0) 117 203 3960

Lamborghini Chelmsford Eastern Approach, Chelmsford, Essex CM2 6PN

Phone: +44 (0) 124 584 7700

Lamborghini Edinburgh Kinnaird Park, Edinburgh, EH15 3HR

Phone +44 (0) 131 475 2100

Lamborghini Hatfield Hatfield Business Park, Mosquito Way, Hatfield AL10 9WN

Phone +44 (0) 170 7524 105

Lamborghini Leeds 2 Aire Valley Drive, Temple Green, Leeds LS9 0AA

Phone +44 (0) 113 487 3040

Lamborghini Leicester Watermead Business Park, Syston, Leicester, LE7 1PF

Phone +44 (0) 116 490 6626

Lamborghini London 27 Old Brompton Road, London SW7 3TD

Phone +44 207 589 1472

Lamborghini Manchester St Mary’s Way, Stockport, Manchester, SK1 4AQ

Phone +44 (0) 161 474 6730

Lamborghini Pangbourne Station Road, Pangbourne, RG8 7AN

Phone +44 (0) 118 402 8060

Lamborghini Tunbridge Wells Dowding Way, Royal Tunbridge Wells, Kent, TN2 3DS

Phone +44 (0) 189 225 0605

The recent boom in dog ownership means there have never been more people out there trying to train their dogs – just as everything we thought we knew about canine psychology is coming into question. Oliver Franklin-Wallis reports on the new empathetic approach

Photographs by Tim Flach

Photographs by Tim Flach

When we got a puppy, I thought we’d thought of everything. My wife and I crossed things off our mental checklist, one by one. Breeder or rescue? (Breeder.) What breed? (Miniature Schnauzer.) Name? (Boudica.) The list went on: what to feed her, where she’d sleep, which brand of compostable dog-poo bags to buy. We read puppy books, consulted YouTube, knew our sit from our stay. But as is often the case, there was one thing we hadn’t taken into consideration: delivery drivers.

Delivery drivers are the scourge of modern canine life. It’s as if the postman – that age-old foe! – has suddenly multiplied exponentially. And while Boudica is, on the whole, a very good dog, growing up in the pandemic years meant she rarely had visitors, which led to her becoming a little territorial. So while she’s a delight with children and other dogs, at home that means persistent barking: at delivery drivers, the milkman, window cleaners, pretty much anyone passing by. For a while, we wrote it off as forgivable. Dogs will be dogs, after all. But recently it has ruined enough Zoom meetings for me to finally decide that something needs to be done. The question is: what?