WELCOME TO THE NEW EDITION OF GOODWOOD MAGAZINE. ese are the busiest months of our year, when we welcome hundreds of thousands of guests to the Estate to enjoy the extraordinary thrill of live motorsport – not to mention the delights of the English summer.

Our cover image of a vintage toy robot provides a clue to much of what we take pleasure in at Goodwood: the inventiveness, style and design inspirations of the past, alongside the game-changing innovations that lie ahead. FOS Future Lab has become one of the most exciting elements of the Festival of Speed, showcasing remarkable future technologies and inventions. is year, we look at what robots are going to deliver for humankind, while also investigating the latest breakthroughs in jet propulsion and data visualisation, into which we take a deep dive on p74. In this issue we also report on the rise of driverless race cars (p26) and celebrate 100 years of the Bugatti Type 35 (p23).

New technologies can sometimes a ord us a fresh perspective on the past. On p44, Marek Kohn explains how lidar, a revolutionary type of laser imaging, does just that, revealing the mysteries of ancient landscapes such as the South Downs, the chalk hills we are so lucky to call home. Delving into our own past, Goodwood’s curator Clementine de la Poer Beresford remembers some of the impressive women connected to the Estate and the integral role they played in its story (p58).

Elsewhere in these pages we discover what 2019 Magnolia Cup winner Khadijah Mellah did next; Dr Chris van Tulleken, who spoke at our Health Summit last year, explains why we urgently need to rethink our relationship with ultra-processed foods; Hannah Betts writes in praise of sporty fashion for non-sporty people; and Simon Mills o ers men a 10-point plan for stylish summertime dressing. We also extol the virtues of hedgerows – something very dear to our hearts here at Goodwood. And lastly, we profile Sir Kenneth Grange, the legendary designer who has overseen the creation of so many modern classics, from the InterCity 125 to the Kodak Instamatic camera.

We look forward to seeing you at Goodwood soon.

Robin Maynard

A distinguished environmental campaigner and nature writer, Robin’s career has included stints at BBC Radio 4’s Farming Today and Friends of the Earth, championing sustainable food and farming. On page 96 he examines the history and fightback of that threatened countryside feature, the humble hedgerow.

Kim Parker

Kim is a London-based fashion and beauty journalist whose work has appeared in Harper’s Bazaar, Town & Country, e Times, e Telegraph and Vanity Fair. Having competed in the 2022 Markel Magnolia Cup, on page 66 she looks back at the history of racing silks, tracing the colourful origins of this classic sporting attire.

Amelia Troubridge

London-based photographer

Amelia’s work has appeared in prestigious publications on both sides of the Atlantic including e New York Times, Vanity Fair, Tatler, GQ, Esquire, TIME and Rolling Stone. For this issue, she shot new portraits of 2019 Markel Magnolia Cup-winning jockey Khadijah Mellah, who is interviewed on page 52.

Nate Ryan

Nate has written about motorsport for three decades, covering NASCAR, IndyCar, IMSA and Supercross for USA TODAY Sports and NBC Sports Digital. Ahead of Richard “ e King” Petty’s eagerly awaited visit to the 2024 Festival of Speed, Nate reflects on the NASCAR legend’s enduring popularity on page 33.

Editor Sophy Grimshaw

Art director Vanessa Arnaud

Editorial directors James Collard Gill Morgan

Creative director Sara Redhead

Designer Camila Rivero-Lake

Sub-editor Damon Syson

Picture editor

Charlotte Maguire

Project director Sarah Glyde

Paul urlby

Lucy Johnston

Goodwood creative director Will Kinsman will.kinsman@goodwood.com

Goodwood brand projects Jennie Gott jennie.gott@goodwood.com

Goodwood

junior picture editor Max Carter

An award-winning, Brightonbased illustrator, Paul has created artwork for titles such as e New Yorker,Vanity Fair and e Times, as well as for clients including Vespa, John Lewis, Fortnum & Mason and e Bank of England. On page 84, for our Dressing Up column, he presents his take on fashion’s sport-inspired look.

Lucy is an author and podcaster who curates the Future Lab technology exhibit at Goodwood Festival of Speed. Her latest book, Kenneth Grange: Designing the Modern World, is the definitive appraisal of the revered designer and his work. Lucy is in conversation with Sir Kenneth for e Goodwood Interview on page 36.

Goodwood Magazine is published on behalf of The Goodwood Estate Company Ltd, Chichester, West Sussex PO18 0PX, by Uncommonly Ltd, 30-32 Tabard Street, London, SE1 4JU. For enquiries regarding Uncommonly, contact Sarah Glyde: sarah@uncommonly.co.uk

© Copyright 2024 Uncommonly Ltd. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced without prior permission from the publisher. While every effort has been made to ensure the

of the

contained in this publication, the publisher cannot accept responsibility for any errors it may contain.

David

Can honey bees be saved?

Good day sunshine

Chanel Irvine’s English summer e winning type

Purple patch

Lavender

So power

Lucian Freud’s etchings

Calling

No matter how much the car changes, one thing stays the same: the feeling of Mercedes-Benz. DEFINING CLASS since 1886.

DEFINING CLASS since 1886.

IS THERE EVER ANYTHING SO COMPLETELY, often also so charmingly, dated as an old-fashioned vision of the future? Witness this Machine Robot, a battery-operated toy produced by the famous Japanese maker SH Horikawa in the 1960s. Although clearly made for children – it walks with a lovely swinging arm action, antennae moving and lights flashing – today it’s a collectible, and in some ways it feels current all over again. While the word robot – from the Czech robata, meaning forced labour – is about a century old, the ancients had similar notions, from legends of statues coming to life to the first automata developed in Ptolemaic Egypt, powered by hydraulics or steam. In the 20th century, electricity spurred the robot on – both as science-fiction-inspired toys like our cover star and as an industrial reality. Now robots are set to become daily presences in our lives, a hitherto fantastic notion explored at this year’s FOS Future Lab. Our favourite might just be the DAL-e – which uses autonomous driving and AI facial recognition to deliver a beverage (and other things besides) to your desk. Not so much a scary sci-fi thing of dread, then – think the T-1000 from Terminator II – as an automated “tea lady” for our times.

Pilot’s Watch Performance Chronograph Mercedes-AMG PETRONAS Formula OneTM Team

The new Pilot’s Watch Performance Chronograph 41 is the most performanceoriented IWC chronograph ever engineered. This version with a Ceratanium® case, an elaborate black lacquered dial, and appliqués filled with Super-LumiNova® is dedicated to our longstanding partner, the Mercedes-AMG PETRONAS Formula OneTM Team. IWC. ENGINEERING BEYOND TIME.

Noted: people, objects, news and ideas, from driverless race cars to the wonders of lavender and 100 years of the Bugatti Type 35

WORDS BY SOPHY GRIMSHAW

The Magnum co-founder’s work combined hard-hitting reportage with movie star portraits, like this

Sophia Loren, the still-living legend of the silver screen, says that she never actually spoke the words that LIFE magazine attributed to her in 1961: “Everything you see, I owe to spaghetti.” But at this point, perhaps that doesn’t matter. The phrase hung around for decades, seeming to chime with her persona of a liberated, curvaceous Italian enjoying the good life. One of Paramount Pictures’ leading lights of the 1960s, Loren won two Best Actress Oscars in that decade, and has a clutch of international awards to her name including five Golden Globes. Before all that, the young Sofia Costanza Brigida Villani Scicolone was living in a small apartment in Rome, the city where she had been raised in a decidedly modest home by an aspiring actress mother (she met her father only a handful of times).

“I photographed Sophia in 1955,” recalled Magnum photographer David Seymour of the shoot on the contact sheet pictured here. Loren would have been 20 or 21 in these images, and was still “a budding actress” rather than the full-blown movie star who would, in 1994, be awarded the 2,000th star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. “We talked over the phone and I explained what I wanted,” said Seymour of setting up the shoot. “She invited me over

for a Sunday morning early meeting [and] I found her in bed in a dark blue negligee, although she was talking on the phone. She got up and changed costume, we went to a covered balcony of her apartment and I had nothing else to do but record a stream of poses which somehow met my memory of wartime pin-ups.” He added, intriguingly, “All this was done with a touch of irony and maliciousness.”

A Pole whose parents were killed by the Nazis, Seymour became a news and war reporter during the 1930s and much of his career was dedicated to capturing images documenting the effects of war on Europe. He also co-founded and was president of Magnum Photos. But these images of Loren speak to an additional, significant strand of his work in which he captured images of Hollywood stars in Europe. The year after he took these photos, he would be killed by machine-gun fire near the Suez Canal while trying to photograph a prisoner exchange. His sunny Sunday morning on a balcony in Rome with Sophia Loren lives on here. These images feature in the book Magnum Contact Sheets, published by Thames & Hudson; thamesandhudson.com

Rolls-Royce Spectre WLTP: Power consumption: 2.6 – 2.8 mi/kWh / 23.6 – 22.2 kWh/100km. Electric range 311 - 329 mi /500 - 530 km. CO2 emissions 0 g/km.

Official data on power consumption and electric range is determined in accordance with the mandatory measurement procedure and is compliant with Regulation (EU) 715/2007 valid at the time of type approval. The figures shown consider optional equipment and the different size of wheels and tyres available on the selected model. Changes of the configuration can lead to changes of the values. For vehicles that have been type-tested after January 1st, 2021, the official information no longer exists according to the NEDC, but only according to the WLTP. Values are based on the new WLTP measurement procedure. Only compare power consumption and electric range figures with other cars tested to the same technical procedures. These figures may not reflect real life driving results, which will depend upon a number of factors including the starting charge of the battery, accessories fitted (post-registration), variations in weather, driving styles and vehicle load. Further information about the official fuel consumption and the specific CO2 emissions of new passenger cars can be taken out of the “Guide to Fuel Consumption, CO2 Emissions and Electricity Consumption of New Passenger Cars”, which is available at all selling points and at https://www.gov.uk/co2-andvehicle-tax-

WORDS BY CHRISTIAN SMITH

From habitat loss to pesticides, British bees face a barrage of existential threats. But can these vital pollinators be brought back from the brink?

Our increased awareness of the threats to their existence has made the image of a bee something of a visual shorthand for the looming environmental crisis. As a wildlife icon, what the bee lacks in scale and majesty – compared with, say, the blue whale or the tiger – it more than makes up for with utility.

Almost 90 per cent of wild plants and 75 per cent of leading global crops depend on animal pollination. From apples to almonds, there are countless examples of foods that we and other animals consume that require pollinators. In short, human beings can’t survive without bees, though you wouldn’t always guess that from our actions.

The UK is home to 270 species of bee. They rely on wildflower meadows for food and shelter, but since 1945 the country has lost 97 per cent of these areas, and the pockets of bee-friendly habitats that remain are not always close to each other. This fragmentation is problematic because a foraging bee can’t fly for longer than about 40 minutes before it needs to feed on nectar. Many UK councils, parks authorities and private landowners have introduced schemes that allow areas of fields or parkland, or even roadside verges, to be left to grow. One example is South Downs National Park’s Bee Lines, which aims to provide better connection between

wildflower meadows. But whether or not these efforts will be enough to turn the tide of bee survival remains to be seen.

When it comes to pesticides, the issue is not just that these chemicals can unintentionally kill bees; some herbicides interfere with bees’ navigational abilities and breeding instincts. On Goodwood Home Farm, organic farming methods mean an absence of these chemicals. Moreover, bees are not merely visitors attracted to the Estate by its flora, they are also cultivated by beekeeper Jo Ambrose, who maintains six beehives in the orchard.

“I find it very rewarding to start off with a small nucleus of bees and watch it slowly expand to a full-size colony of 60,000,” says Ambrose. “You need to concentrate on what you’re doing and there’s no room in your head for anything else, so for me beekeeping feels like a form of meditation.”

As a member of the British Beekeepers Association, Ambrose is an “on-call” contact if a swarm of bees ever needs re-homing. “The honey bee has really suffered because of pesticides, parasites, disease, climate change and habitat loss,” she says. “It’s a bonus to be able to take honey from the hives but I only ever take the excess. The bees need their own honey in order to thrive.”

Chanel Irvine’s atmospheric photographs are a love letter to the simple pleasures of the English summer

WORDS BY SOPHY GRIMSHAW

“I’m South African, but I grew up in Australia from the time I was six, and we were lucky enough to have a beach house on the Sunshine Coast,” says photographer Chanel Irvine. “So before I moved to Europe,” – Irvine studied photography in Paris prior to moving to England in 2017 – “I had always experienced a very consistent, kind of guaranteed, hot summer.” She’s speaking today from her home in a Kent village, where she is taking a break from choosing flowers for her summer 2024 wedding. “I like how precious the season is in England, and how excited we are about summer in this country. It brings a sense of solace every year,” says Irvine, whose background is in documentary photography. “Perhaps it’s treasured because of how fleeting it sometimes is. As an outsider, I feel summer is celebrated more in this country than elsewhere. I like all the rituals,” she adds, and she doesn’t necessarily mean just the folkloric kind –maypoles and the Green Man – though she’s interested in those, too. “Even the simple things like everyone rushing to the park the minute the temperature hits 15°C, suddenly transported to a beach in their minds.”

Irvine’s appreciation for Britain during the warmer months is expressed in her prolific ongoing photography project, “A Study of Summer”. In 2022, some of her images were collected together as a book, An English Summer, but she continues to add to the project. Her muted, calm photographs depict not just beach scenes but also rural views from cosy caravans, families with their feet and fishing nets plunged into deep green rivers, and stunning British coastal landscapes, from craggy headlands to tidal pools – often under unapologetically overcast skies. “These photos are meant to feel quiet. There’s a funfair here and there, but I typically show peaceful moments, where people really are just absorbed in their surroundings.” One of these images presents her friend, the writer Rosalind Jana, making the most of a warm day in Shropshire by taking a dip in the river. “It was one of her favourite swimming spots in childhood, so she took me there,” remembers Irvine, who was in the area on an unrelated photo assignment for a magazine. “I feel like everyone kind of agrees that there’s just something magical about summer here, isn’t there?” chanelirvine.com

Ask a petrolhead to name the most successful racing car of all time. Formula 1 fans might nominate a Red Bull, Mercedes, Ferrari, McLaren or Lotus; sports car enthusiasts might propose an Audi, Porsche or Ford. All reasonable suggestions. Yet in terms of race wins, one car is so far ahead that it has almost vanished over the horizon of popular memory.

Launched 100 years ago, the Bugatti Type 35 was not only beautiful to look at, it also set new standards for technical brilliance. Ettore Bugatti understood that light weight was the key to drivability, reliability and performance, and his factory at Molsheim, near Strasbourg, was renowned for exquisite engineering.

The T35 was conceived as a racer from the start. The marque’s trademark egg-shaped radiator was truncated at the base, sitting lower and closer to the front axle for better weight distribution and aerodynamics. That axle was now a forged tube, lighter and stronger than traditional solid designs, and the car rode on elegant alloy wheels with integral brake drums, further reducing the unsprung weight.

Beneath the slim alloy bodywork lay another masterpiece, a 2.0-litre, eight-cylinder engine whose crankshaft was supported by no fewer than

five bearings for durability and power. Revving to 6,000rpm and breathing through twin carburettors, its 95PS (94bhp) could propel the 750kg machine to 120mph. Subsequent developments included a supercharged 2.3-litre version that accelerated from 0-60mph in just six seconds, with a top speed of 130mph.

The T35’s debut at the 1924 French GP was spoiled by faulty tyres, but thereafter it proved almost unbeatable in the hands of top drivers such as Albert Divo, Tazio Nuvolari, Louis Chiron, William Grover-Williams, Hellé Nice and Eliška Junková. It won the AIACR World Manufacturers’ Championship in 1926, the first Monaco Grand Prix in 1929 and five Targa Florio road races in a row. A commercial success, it was popular with amateur drivers, too; about 350 were built from 1924 to 1930, including road-legal versions. Most impressively, the T35 scored more than 1,000 race wins and at least as many podium finishes in a decade. Bear that in mind next time you hear last season’s Red Bull RB19 lauded as history’s greatest F1 car because it won 21 grands prix. Some cars are the stuff of legend with tales of glory that live on for a hundred years – and counting.

The Bugatti T35 will be celebrated at the 2024 Goodwood Festival of Speed

WORDS BY GILL MORGAN

Treasured since ancient times for its medicinal qualities, lavender is now having a horticultural moment as climate change hits British gardens

“Like lavender, I bloom in the most unlikely places.” So wrote Atticus, the Roman poet. And it’s true that England’s often chilly and soggy climes seem an unlikely place for this muchloved plant to flourish. Yet it does, to the extent that avenues of lavender in full flowering summer pomp are an archetypal feature of the traditional English cottage garden.

The plant’s origins lie much further south, in the Mediterranean, Persia and other parts of the Middle East. Its emotional, spiritual and medicinal properties have been treasured from antiquity – and indeed it is the Romans who are believed to have first brought lavender to the British Isles. Cleopatra is said to have used lavender oil in her romantic armoury when seducing Julius Caesar and Mark Antony, while traces were found in Tutankhamun’s tomb, no doubt helping to protect the young king in the afterworld. But despite these associations with warmer climates, this perennial woody shrub thrives in well-drained, chalky soil (of the sort in plentiful supply in the South Downs), with plenty of sun. The traditional English nursery rhyme and folk song Lavender’s Blue, first recorded in the 17th century as Diddle Diddle, Or The Kind Country Lovers, celebrates its role in romance – a-courting ladies would tuck a lavender pouch into their cleavage for added allure. Used to perfume all manner of soaps and waters, the origin of its name comes from the Latin lavare, to wash.

Long thought to help ward off evil spirits, it’s likely that such associations were firmly rooted in lavender’s inherent anti-bacterial properties: it was viewed as a protector along the lines of our Covid-19 vaccine in times of mediaeval plague and outbreaks of cholera. Loved by queens – Elizabeth I is thought to have had a vase of it on her desk each day – and paupers alike, there seems no end to its powers: antiseptic cure for wounds, moth deterrent, anti-anxiety medicine, sleep aid, muscle relaxant, even antidepressant. Today, biomedical and neuroscience research is providing contemporary evidence supporting what people have known for centuries. And now, in this challenging time of climate change, lavender is coming into its own with renewed vigour, as a plant that can withstand the extreme summer temperatures of recent years. Mixed with rosemary, euphorbia and grasses, it appears in abundance in the most modish of gardens, one of nature’s heroes – and survivors.

WORDS BY BEN OLIVER

This year’s Festival of Speed presented by Mastercard will see two driverless race cars going head-to-head on the Hill. Is this the shape of things to come for motorsport?

Motorsport is changing fast, reflecting the environmental concerns and technological advances of the world around it. From 2026, Formula 1’s hybrid cars will run solely on sustainable fuel. Goodwood Revival will get there two years earlier, with all competitors in this year’s event using fuels that add no new carbon to the atmosphere. The Formula E and Extreme E race series get rid of combustion engines altogether, and prove that you don’t need petrol and pistons to produce thrilling racing.

Getting rid of racing drivers, too, and replacing them with AI, would probably be a step too far for even the most forward-thinking fan, yet two of the most keenly anticipated cars to sprint up the Hill at this year’s Festival of Speed will be doing so without human assistance. We’ve seen it before, of course: the Roborace series ran for two seasons, sending its wildlooking cars to FOS, and the new Abu Dhabi Autonomous Racing League, A2RL, has just got under way with a day of racing at the Yas Marina Circuit.

But the Indy Autonomous Challenge is the only current race series for self-driving cars. Nine teams drawn from some of the world’s leading universities compete in almost identical machines supplied by legendary Italian race-car maker Dallara and powered by a pleasingly old-school turbocharged petrol engine. A profusion of cameras and sensors sprout from where the driver would usually peer out. The only difference between the cars is the software driving them, which each team must develop itself. The series has already raced at the hallowed Indianapolis and Monza circuits, among others, and one of its cars set a new autonomous land speed record at 192.2mph at the Kennedy Space Centre in 2022.

After making a static appearance at the Future Lab pavilion during last year’s Festival of Speed, two IAC teams will go head-to-head on Goodwood Hill this year after carefully mapping its infamous off-camber corners and forbidding flint wall. It will be the first time they’ve raced in the UK, and,

given the rate at which autonomous driving tech is advancing, they should decimate the times set by the Roborace cars.

Goodwood’s knowledgeable crowd will understand their mission. The aim isn’t to make racing drivers redundant, but rather to do what motorsport has always done: to test new tech in the toughest possible environment and, once proven, pass it down to cars we can all drive. The dream of completely autonomous cars that will convey us to any destination while we snooze is still some years off, but the same tech can already chauffeur us unaided in certain circumstances, and help human drivers to be safer all the time. The PhD students coding the cars you’ll see at Goodwood might one day go on to crack full self-driving. Until then, we can enjoy the spectacle of race cars that can not only power their way to the top of the Hill, but think their way up it, too.

Goodwood Festival of Speed runs from 11–14 July 2024

WORDS BY JAMES COLLARD

A dog in repose, shown just as it is about to receive a gentle pat, Pluto Aged Twelve seems an aesthetic world away from the work that made Lucian Freud so famous. But it’s one of the highlights of A Creative Collaboration, an exhibition of Freud’s etchings at London’s V&A, which explores the artist’s long collaboration with the late Marc Balakjian, a celebrated master printer.

Freud is renowned for his paintings – nudes, landscapes, portraits, including double portraits of people and dogs (with the dogs portrayed just as vividly as the people). But he was also an avid creator of prints, both at the start of his career in the 1940s and then again from 1982 onwards. In 1985, he began working with Balakjian – who, with his wife Dorothea, produced superb prints for artists including Freud, Leon Kossoff and Frank Auerbach from their print studio in a former Sainsbury’s in Kentish Town.

“They definitely seem more tender”, says Gill Saunders, the V&A show’s curator, of his etchings. “Perhaps because they tend to be close-up.” Freud often worked on vast plates, which, unusually, he balanced upright on an

easel, rather than working on the more typical draughtsman’s desk. On these, he created landscapes (After Constable’s Elm), portraits (of performer Leigh Bowery, and of Freud’s daughter in Bella in Her Pluto T-Shirt, which gives a cameo role to Pluto) and self-portraits. In the V&A show we see plates, but also cancelled works – scored and crossed out by the artist, yet still rather beautiful – and sets of proofs that show how artist and printmaker collaborated until they reached results both were happy with.

A treasure trove of trial proofs of etchings was acquired in lieu of taxes from Balakjian’s estate following his death in 2017. He was renowned for his rare ability to “get into the mind of an artist – a remarkable kind of intuition”, Saunders explains, while Freud found working in this art form both “satisfying and interesting. He was using a different graphic language.” The results of their collaboration endure.

Lucian Freud’s Etchings: A Creative Collaboration is at V&A South Kensington until 25 August 2024; vam.ac.uk

WORDS BY EMMA BALLARD

The first recorded female golfer is Mary, Queen of Scots, who was seen playing the sport in 1567 and is believed to have ordered the construction of the famous St Andrews Links during her reign. But more than 450 years later, she remains an outlier in what is still a male-dominated sport. In recent times, however – and especially over the past two decades –golf’s governing bodies and related industries have sought new ways to encourage more women to play, with varying degrees of success.

In the UK, female participation is around 25 per cent and women make up, on average, 13 per cent of a golf club’s membership, indicating that there is still plenty of work to do. One reason for a small increase in female players might actually have been the knock-on effect of golf having been the first sport that was opened up during the Covid-19 pandemic, with a small but noticeable 1.5 per cent increase in female membership at England Golf-a liated clubs in 2020.

Initiatives from England Golf such as Girls Golf Rocks (for girls aged 5-18) and its adult equivalent, Get into Golf –

which has a women-only option – have had a positive impact in breaking down traditional barriers and demystifying the sport. Part of the overarching strategy is to remove the need for a social circle to introduce you to the rules and norms of golf, and to build confidence, regarding both technique and etiquette, in newcomers to this centuries-old pursuit.

Golf at Goodwood offers a relaxed introduction to the sport, and the option of playing in a ladies-only group, with its four-week Get into Golf sessions. There are three categories – beginner, improver and “get out onto the course” – all of which are run by qualified PGA Professionals. “We also offer a Get into Golf membership that gives you the opportunity to have one-to-one golf lessons with a PGA Professional, as well as getting out onto the course during quieter times,” says Goodwood’s Sophie Ham. “And we run etiquette and rule sessions to help our golfers learn everything they need to know.” In this way, new female golfers are given the confidence and skills they need to get started. Mary, Queen of Scots would surely have approved.

Ex-Rolf Meyer Collection 1924 MERCEDES 10/40/65 SPORT

High quality edition produced by John Bentley 1886 BENZ PATENT MOTORWAGEN THREE WHEELER REPLICA

of Benz, Mercedes, and Mercedes-Benz Motor Cars

Original Rudge wheel example 1955 MERCEDES-BENZ 300 SL GULLWING

Late series, disc brake example 1962 MERCEDES-BENZ 300 SL ROADSTER

Ex-Robert Arbuthnot, Edward Mayer, CWP Hampton 1928 MERCEDES-BENZ 26/120/180 S-TYPE SPORTS TOURER

Ex-Warner Brothers President John Calley 1955 MERCEDES-BENZ 300 SC CABRIOLET

Channel Islands since new and just 13,215 miles recorded 1968 MERCEDES-BENZ 280 SL ROADSTER WITH HARD TOP

Rare right-hand drive example 1971 MERCEDES-BENZ 280 SE 3.5 CABRIOLET

1937 MORGAN 4/4 ROADSTER

Chichester, Sussex | 12 July 2024 | Entries Invited

Bonhams|Cars are delighted to announce this magnificent collection originally assembled by the late Tom Scott Senior to headline this year’s Goodwood Festival of Speed sale.

ENQUIRIES

+44 (0) 20 7468 5801 ukcars@bonhamscars.com bonhamscars.com/fos

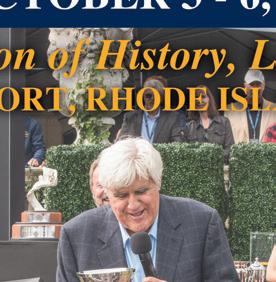

WORDS BY NATE RYAN

After more than 60 years in motorsport, American driver

Richard “The King” Petty – who will be honoured at this year’s Festival of Speed – still delights in meeting his fans

Richard Petty’s success as a NASCAR driver is the stuff of motorsport legend. His 200 Cup Series victories and seven Daytona 500 wins are alltime records that look unlikely to be broken, while his seven Cup Series championships put him level at the top with Dale Earnhardt and Jimmie Johnson. It’s easy to see how he earned his nickname: “The King”.

Hailing from the tiny tobacco-farming community of Level Cross, North Carolina, Petty, who turns 87 this July, dominated NASCAR for much of a career that formally ended in 1992. He has remained a track fixture since, both as a team owner and a corporate spokesman for myriad sponsors, serving as an uno cial ambassador for the sport over eight decades.

As a second-generation racing superstar – his father, Lee, won the first Daytona 500 in 1959 and was also a three-time NASCAR champion – Petty is famed for always making time for his fans. Since his 1958 debut, he estimates he has signed more than two million autographs, commenting: “Very few people have signed more than I have. Some days you don’t sign any, and some days you do 3,000.” American motorsport icon Roger Penske remembers Petty sitting on the hood of his blue No 43 Plymouth Superbird for hours after races, meeting fans. These days, it’s often a selfie

that racegoers request – with his ever-present sunglasses, Stetson and ready smile, Petty is a highly recognisable figure – ideally one with his son Kyle, a stock car racer turned commentator.

Petty will no doubt have his pen at the ready during the 2024 Festival of Speed. He will be returning, accompanied by Kyle, for his first Goodwood appearance since 2019, as the Petty family celebrates its 75th year in racing (Petty Enterprises was founded by Richard’s late father, Lee). The current father-son duo will be showcasing the iconic No 43, and “The King” is set to be saluted on the balcony at Goodwood House.

“It’s such a prestigious event,” Petty says of his return to Festival of Speed, “and bringing the Superbird will make it even more special. Kyle will be driving, which adds another layer of significance.”

As always, much of the NASCAR star’s focus will be on meeting fans and interacting with the crowds. As he once said, “Those are the people who put me in business and they’re the reason I’m here. If it wasn’t for the fans, you probably would have to work for a living.”

Richard Petty and his son Kyle will be attending all four days of Goodwood Festival of Speed, from 11–14 July 2024

Tales worth telling, from the fascinating revelations of lidar imaging to the historic women of Goodwood.

Plus: e Goodwood Interview with Sir Kenneth Grange

Kenneth Grange

by Lucy Johnston

“The richness of the experience furnished me with a training which could not have been gained in any other way”

Known as Britain’s “moderniser in chief”, prolific multidisciplinary designer

Sir Kenneth Grange’s extraordinary career has seen him create an array of iconic products, from Kodak cameras and Anglepoise lamps to postboxes and parking meters. Now in his nineties, he sits down with his biographer, Lucy Johnston, curator of FOS Future Lab, for The Goodwood Interview

Sitting in his courtyard garden, basking in the welcome rays of May sunshine, and with his 95th birthday on the horizon, Sir Kenneth Grange cuts a dashing figure.

Sporting a jaunty Panama hat, long legs clad in tartan loungewear finished with a pair of Scandinavian felt clogs and big cra sman’s hands playing with the curved arm of his garden chair, he moves slowly these days – but the wit and the sharpness of thought are still very much present. He and his wife Apryl balance their time between this cottage in Hampstead – a cosy oasis of white walls and parquet floors, purchased in the 1970s – and a barn conversion in deepest Devon that embodies Grange’s collected influences from eight decades of work across international industry.

I have known Grange for most of my life through my grandfather, Dan Johnston, who in the early 1960s was Head of Industrial Design at the Council of Industrial Design (CoID), a then-flourishing postwar government body established to promote the value of good design in industry (later renamed the Design Council). Its Design Selection Service was set up by the CoID to match industry clients with a shortlist of highly rated design talent. An unknown but promising young designer called Kenneth Grange was placed on that list in 1956 and to this

day he credits it with bringing him his most important early breaks in design; notably the Venner parking meter and the Kenwood Chef food mixer.

It was a time of vision, determination and dynamism that began with the Festival of Britain, where a 21-yearold Grange cut his teeth; a golden era when design and manufacturing worked side by side to build a vibrant, world-leading modern industry across the UK. “It’s impossible to describe what it was like,” he says of those influential months of the Festival of Britain, “or for someone now to imagine themselves in the shoes of someone back then, who was witnessing that level of colour and vibrancy and innovation for the first time.”

Grange’s career is a journey that has run in parallel with the evolution of the wider design and manufacturing landscape in Britain and beyond. And, thanks to his habit of never throwing anything away, he has accumulated an exceptional archive – recently acquired by the V&A –including models, sketchbooks, technical drawings and thousands of photographs of his working processes.

Grange was born in Whitechapel, East London, in 1929 to Harry, a police constable, and Hilda, who worked long past retirement as a machine operator in a spring factory. His mother’s love of “gra ing to do good work” was a strong influence on Grange, as were his father’s skills as

HST diesel electric power car

The technical drawing on the left below depicts the final proposed profile for the cab of the High Speed Train (HST) diesel electric power car (later the InterCity 125). Having been commissioned to design the livery for a previous prototype, Grange took it upon himself to redesign the nose of the power car itself – below displaying the original launch livery he also specified. The first HST went into service in 1975 and the trains can still be seen today on some lines around the UK.

Kodak Instamatic 33 series

The sketch above, reproduced from Grange’s notebooks, records his early thoughts on the redesign of the structure and materials for the Instamatic camera, a US invention which he was commissioned to refine for a European sensibility. His eventual design for the 33 series (pictured left), which launched in 1968, became an overnight sensation across Europe, sold millions of units, and rocketed Grange to new levels of design industry fame.

Wilkinson Sword razor These concepts for a disposable razor (pictured below left) were made from painted wood and plastic in Grange’s Pentagram workshop in 1981. They show the proposed colour variations for the Wilkinson Sword Retractor – the first razor to feature a retractable blade, thus reducing manufacturing costs as no separate protective cap was required. The large volume of sales of this now ubiquitous model reinforced Grange’s standing as consultant design director for the business.

a practical cra sman. As a young teen during the World War II years, Grange spent long blackout evenings at the dining table, studying shrapnel his father had brought home from the Bomb Disposal Division, or working out the structural design of Spitfires from posters in order to build his own models in balsa wood. He was also fond of taking apart and reworking his beloved bicycle. All of this fuelled his endless fascination with how things are made.

In 1943, Grange surprised himself by putting up his hand in assembly when the headmaster asked if anyone would be interested in a bursary to attend art school. Four years studying commercial art at Willesden College of Technology followed. “Design wasn’t even a word that was in use back then,” he explains. “Certainly the practice of industrial design came out of the architecture studios in the years a er the war, and when I first started out, there were really very few of us in the profession.”

On leaving college, Grange found work experience at Arcon in Piccadilly, the star architecture o ce of the day, where he honed his skills in model-making. e o ce, which he has described as “a natural gatherer of the talent of the age”, was where he first experienced how the modern world could look, with white walls and sleek furniture and lighting. A er completing two years of National Service, working as an architectural draughtsman, Grange took up a role as a design assistant in the o ces of his mentor,

Royal Mail post box

Grange’s design for a new rural post box, created during his final year at Pentagram and launched soon after his retirement in 1998, took into account new trends: the wider slot allowed for the growing popularity of larger, hardbacked envelopes. The post box was nicknamed the Bantam by Royal Mail workers, because of its resemblance to the fuel tank of the classic red GPO Bantam motorcycle of the 1950s–70s.

Jack Howe. A key figure in mid-century design, Howe had previously been a partner at Arcon.

Learning much about both the practice and the business of design from Howe, Grange was encouraged to take on his own freelance design commissions. ese jobs were mainly exhibition stand designs – a vital part of industry in those postwar years. ey gradually grew in scale until, with Howe’s full support, Grange le to set up on his own. So it was that in 1956, marking the “single biggest turning point in his life”, the fledgling Kenneth Grange Design o ce was founded in the spare room of his flat in North London. From this moment on, his trajectory would be a constantly rising forward motion.

A er the early success of his distinctive Venner parking meter design, Grange’s “luckiest break” came while he was working on an exhibition design for the Kodak pavilion at the 1958 Brussels World’s Fair. A chance encounter led to a commission to redesign one of the US-made Kodak camera models for a more European sensibility. is would develop into a client relationship that lasted two decades and saw millions of Grange’s cameras sold – and the cultural icon status bestowed on the Instamatic would do much to establish his name as a dynamic figurehead for modern British design. Meanwhile, as he was cementing his early relationship with Kodak, another new client came calling: a gentleman

Kenwood Chef

In 1959, Ken Wood of the Kenwood Manufacturing Company commissioned Grange to give his original Americana-inspired Kenwood Chef “a new suit of clothes” to revive customer demand in Europe. On its launch in 1960 the new machine (pictured below) immediately became hugely popular, selling millions of units over the following decades, changing kitchens forever and proving Grange’s belief that over-engineered products stand the test of time.

Anglepoise Type 75 lamp

This sketch (right) explores the articulation of Grange’s first product design for Anglepoise, which refined the structural form of the original classic three-spring lamp conceived by George Carwardine in 1932 – described by Grange as “a minor miracle of balance”. His Type 75, launched in 2004, transformed the Anglepoise business, placing the timeless desk lamp back at the centre of a new consumer era attuned to the values of impeccable, functional, ageless design.

by the name of Ken Wood was in need of a revised design to improve the look of his food preparation machine, the Chef. Grange’s tenure as external design director for Kenwood would outdo even his era with Kodak, and saw him design over 120 kitchen appliances for the company, including four iterations of the enduring Chef itself.

“I was really thrown in at the deep end,” he recalls. “By the end of the 1950s I was employed by three very di erent types of company in Venner, Kodak and Kenwood. e richness of the experience furnished me with a training that could not have been gained in any other way”.

In all three of these early cases Grange was presented with a prototype or previous model of a product, with the brief to redesign and refine it for more modern tastes. e first thing he always did was take the object apart. “You learn by disassembly,” he says of this approach. “ at’s one of my great enthusiasms. You learn more by taking something apart than by trying to invent it from scratch.”

By now, design commissions were steadily rolling in and Kenneth Grange Design had become too big to run from his flat. So in 1961 Grange relocated to his first studio, at 7a Hampstead High Street, a much-loved address that o ered space not just for the team but also to install a proper workshop for making development models of his designs, the all-important trademark that remained at the heart of Grange’s working practice throughout his career. “It was the only medium in which I had confidence to sell my ideas,” he says of his models. e following decade also saw Grange indulge his love of cars. Never one to flash his growing wealth, his choices were “really always for fun, whether it was a Citroën Dyane or a Ferrari Dino”. In the early 1960s he bought one of the first Jaguar E-Types: “I caught a glimpse of it in an advert in the newspaper and it was the most extraordinary vision of the future I had ever seen. I simply had to have one.” By the end of that decade, Grange once again needed a larger studio. He joined forces with the celebrated architecture and graphic design o ce of eo Crosby, Alan Fletcher, Colin Forbes and Mervyn Kurlansky, with whom he had collaborated on designs for the UK’s first self-service petrol station forecourts for BP. e Pentagram design partnership was founded in June 1972, and rapidly became world-renowned. “At that point there were no other large, multidisciplinary design o ces in the UK”, recalls Grange, “and we really felt like we were stepping into a brave new world.”

e Pentagram years were wide-ranging in their scope and achievements, taking Grange all over the world and delivering titles, awards and recognition. Although his name is still not widely known outside the design industry, the mid-1970s would see one particular project bring him a global fanbase: the High Speed Train (HST), later renamed the InterCity 125. “ rough a brief to do the paintwork came the biggest job of my life,” says Grange. He took the initiative and spent the three weeks of his allotted time for designing a livery for the prototype power car working instead on redesigning its nose. Nights spent refining his design with models in the wind tunnel at Imperial College paid o when, although surprised by his uninvited design pitch, the British Rail design panel enthusiastically welcomed his input. ey proceeded to employ Grange to develop the final distinctive profile of the production power car, which would go on to set a diesel rail world speed record of 148.5mph that is still held today. e very first production power car – number 43002 – manufactured in 1975 and retired in 2019, now sits

in the centre of the National Railway Museum, restored to its original livery and renamed the Sir Kenneth Grange. Even today, a number of the power cars remain on rails around the globe, for commercial and pleasure use. Of his world-recognised design, Grange says, “When the HST first launched, it was the only modern thing in sight across the British landscape. ere was nothing else that approached it as evidence of the future and as a symbol of progress.” And of its longevity, he says, “My view has always been: ‘Make it as well as you can.’ Many of my products have been over-engineered; not just the train but also, for example, the Kenwood Chef. But that works to the good in my view, because once you embrace this ethos, inevitably the product is going to last much, much longer.”

He still speaks with great respect about the team of engineers who made the train possible, and of the thrill of visiting the Derby Works during those developmental years. roughout his career he has insisted on visiting the factories of his clients, to ensure that he fully understands their manufacturing processes and technical requirements. His favourite example of this approach is the range of speakers he designed for Bowers & Wilkins. First introduced to its founder, John Bowers, in 1973, Grange would work as the West Sussex firm’s external design director for four decades, devising such celebrated models as the 801, which set the bar for every loudspeaker that followed and became the reference monitor of choice for EMI at Abbey Road Studios. Grange was always mindful to collaborate closely with the company’s exceptional audio engineers so that he really understood how his three-dimensional forms could support them in delivering the “ultimate listening experience”. Looking back, he says, “It is fastidious attention to detail that marks out the superlative from the good. is requires e ort, which takes time.”

Retirement from Pentagram in 1998 did not bring retirement from the industry. Instead he returned to practising as an independent designer, keeping on a few favourite old clients, such as B&W, and taking on just a few new ones. e most notable of these has been Anglepoise, which quickly became very dear to Grange thanks to the company’s belief in making enduring products that can be handed down through the generations in lasting style. “ e demands of modern commerce have so dramatically changed our trade, and the system is now completely out of whack,” he stresses. “ ere must be a better way, where we focus on considering the materials and making, and appreciate the pure pleasure of good, simple design and long-lasting quality.” Appointed consultant design director for Anglepoise in 2003, he was instrumental in reviving the brand for the modern era, and continues to work closely on the next generation of designs.

Few individuals have contributed so directly to the evolution of British design and manufacture since those heady days of the Festival of Britain, yet Grange is characteristically humble about his achievements. “In Jack Howe’s and then my own generation,” he says, “it was far more possible for a designer to move between industry sectors, from architecture to trains. If a client trusted in their ability, that was what mattered.” And despite his modest habit of frequently mentioning “luck” as part of his story, it is Grange’s almost unrivalled ability as a designer that still shines through.

Kenneth Grange: Designing the Modern World by Lucy Johnston ( ames & Hudson) is out now

Modus March Lite chair

The stackable March chair was first developed by Grange for premium British furniture brand Modus in 2015 – in collaboration with Jack Smith of SmithMatthias, whom he had previously mentored at the Royal College of Art. Though well received, the first iteration was costly to produce in any volume, so Grange refined the design by “shaving it down”. The March Lite (right) was launched with great success in 2020.

Venner parking meter

The distinctive upside-down teardrop form of Grange’s design for the Venner parking meter (below) was first installed in Grosvenor Square, Westminster, in 1958. It became an iconic and ubiquitous feature of city streets in the UK for more than three decades, before being gradually replaced during the 1980s by electronic card-reading meters.

and Britain’s leading luxury motor group

By

revealing

previously

invisible details of landscapes around us, the innovative technology of lidar scanning has proven to be a revelation for archaeologists, offering a fascinating glimpse of the past. Marek Kohn discovers its secrets

One day in March, 10 years ago, an aeroplane flew back and forth across a tract of Sussex land that includes the Goodwood Estate, scanning it with laser pulses. e data it gathered became the basis of a project that created a new map of the area’s past, and a new community devoted to seeing the landscape’s past in a fresh light. Titled “Secrets of the High Woods”, the collaboration between English Heritage and the National Trust was a model example of a new kind of archaeological investigation, in which volunteers and experts use the results of airborne laser scanning to reveal hitherto unknown marks le on the land by people hundreds or thousands of years ago. e technology is known as lidar, which stands for “light detection and ranging”, and indicates its kinship with radar, which is an acronym for “radio detection and ranging”. Over the South Downs, its story marks an upswing in a bittersweet historical arc. A hundred years ago, people began to take photographs from aircra , and aerial surveys in the middle decades of the 20th century revealed ancient traces that could not be seen at ground level. Lines in fields of crops, where the plants grew more or less strongly than their neighbours, betrayed the presence of underground structures such as walls or ditches. But even as the new evidence was being detected, it was being destroyed. Open downland went under the plough during World War II, providing crops to feed the nation, and the ploughing continued a er the war as more of the land was converted to arable fields. Heavy tractors and deep ploughing erased traces of human activity that had survived centuries or millennia of intensive but less invasive land use. While open landscapes dominate the eastern Downs, however, the west is more wooded. is pattern of land use dates back to the 12th century, when Norman lords began to create deer parks on their estates in the area. e woods remained standing, preserving the traces of the past within them. But those traces were not just undisturbed, they were largely invisible – until the advent of lidar, the technology that is said to “see through trees”. By revealing them, along with features in open land that had hitherto gone unnoticed because of their faintness, lidar is helping to turn sketches of past landscapes into richer pictures, adding subtle details that help to make sense of the whole scene. “Lidar o ers the

chance, both in the hidden landscapes of the woods and the obliterated landscapes of the east, to find ghosts of field systems and barrow groups and other structures,” says Matthew Pope, an archaeologist from Brighton who teaches at University College London, “and work towards a unified picture of prehistoric downland landscape use.”

Aerial lidar doesn’t really see through trees, but it does see through woods to the land beneath. It works by sending laser pulses downwards and recording them as they are reflected back from surfaces they meet. Some hit surfaces above ground level, such as leaves, while others pass through gaps in the vegetation and reach the ground. e data can be processed to create images that show either the land together with objects such as trees and buildings on it, or just the terrain with the objects removed.

ese images can then be manipulated to highlight anything that stands even a few centimetres above its surroundings – which may be all that’s le of an ancient feature. “When you’re walking through it, you don’t necessarily realise that there’s a ditch or a bank until you trip over it,” remarks Simon Crutchley, remote sensing development manager for Historic England. Time and ploughing, for example, may have spread the remains of a Roman road out to a width of up to 30 metres, with the centre le as little as 30 centimetres high. “You stand on it, and very o en you can’t see the damn thing,” says Mike Haken, who chairs the Roman Roads Research Association. “Lidar enables us to do that.”

Simon Crutchley regards the impact of lidar on archaeology as “transformational”, and Mike Haken’s group, which boasts more than 500 members, is a striking example of that impact. e RRRA was born in 2015, out of frustration with what Mike Haken and his collaborators saw as the inadequate state of Roman road mapping in England. “ e impetus for [forming the association] was the realisation that there was a group of individuals across the country who were starting to work with lidar,” Haken says. “If we want to understand the Roman period, we have to understand the whole network and infrastructure first. It’s been very much ignored until recently.” Lidar, it seemed, o ered the key.

e group’s mission is to build on the work of Ivan Margary, whose landmark book, Roman Roads in Britain, was first published in 1955. Margary systematised existing knowledge about Roman roads, numbering them

1. Trackways on the north face of the down between Westmeston Bostall and Plumpton Bostall

2. An overview of the South Downs mapping area reveals marks left on the land by people hundreds or thousands of years ago

according to a system like the one used for modern roads. His network included conjectures made on the basis of his reasoning about which places the Romans would have built roads to connect, and what routes those roads would follow. Number 153, he confidently asserted, ran eastward from Chichester to Brighton. Sixty years later, the High Woods lidar survey provided a faint but impressively straight line across the map that supported Margary’s claims about where the eastern end of the road had run.

Lidar-based work has added much more to the Roman road map than details like this, though. Studies led by a team from the University of Exeter have identified a whole network of Roman roads in Devon and Cornwall, a part of the country where evidence for such roads had previously been scarce. Even a er lidar scanning, evidence in much of the region was notable by its absence, so computer so ware did the kind of work Margary had carried out through poring over maps, analysing terrain to identi likely routes across the countryside.

By the time the findings were published last year, the whole of England had been surveyed by the Environment Agency’s National Lidar Programme. e freely available data is now the basis both for academic research, like the University of Exeter team’s work, and voluntary activities, like those of the Roman Roads Research Association. Full national coverage, Mike Haken says, is “what’s really changed the game. It’s completely redrawing the map. Across the country, I would estimate that we’ve increased the number of known Roman roads by about 50 per cent.”

Although lidar has transformed the study of past landscapes, it hasn’t replaced other techniques. Matthew Oakey, Historic England’s aerial survey principal, observes that a single project might draw on lidar data from a year before as well as photos taken from the air 100 years ago. Nor does lidar remove the need to check features detected in images by going out and looking for them on the ground, a procedure known as “ground-truthing”. e High Woods project was “exemplary”, Matthew Pope believes, in the way it combined its research techniques and its participants. Lidar generated the data; experts and members of the public used the images to identi features and then ground-truth them among the Sussex trees.

Truthing on the ground isn’t always possible, though, and lidar can enable people to do a lot of archaeological work that wouldn’t otherwise be feasible. It’s an inclusive application of technology, allowing people who can’t get into the field for a range of reasons – fitness, health, distance, the cost of archaeological digs, or just shortage of time – to survey landscapes from home. “It’s very democratising,” observes Matthew Oakey. “You don’t have to have privileged access to very specialist datasets and specialist so ware.” He notes that a number of projects recruiting “citizen” archaeologists arose during the Covid-19 lockdown, when ground-truthing was not an option. Having been forced to rethink its “Understanding Landscapes” community archaeology undertaking, the University of Exeter team came up with a lidar project they named “Unlocking Landscapes”. e free availability of lidar data may not be entirely a good thing. Pope cautions that putting out information about possible sites is like “putting out targets” for collectors and metal-detectorists pursuing their own interests, rather than those of the community as a whole. But lidar images can also enrich individuals’ relationships with their landscapes in ways that weave personal experience and community knowledge together. Archaeologists have been surveying and digging Britain for a very long time, so the chances of any spectacular new finds are limited – unlike in regions such as Amazonian Ecuador, where lidar has helped detect the remains of a dense network of towns more than 2,000 years old under the forest canopy. Instead, British lidar archaeology typically identifies features that are small enough for people to engage with on a level that feels more personal and relatable.

“ ese are landscapes that people will know intimately,” says Oakey. “ ey might have been going there for 40 years, walking their dog every day.” Lidar images show them the “big picture”. ey learn that the reason they go up and down a dip every time they walk into a familiar field is “because you’ve just walked across a 4,000-year-old field boundary. All of a sudden, that gives you a completely di erent connection to that landscape.”

Lidar o ers us a glimpse of the depths hidden below a few unassuming centimetres of earth, and our intimate bond with them.

Khadijah Mellah made headlines and history at Goodwood by winning the 2019 Magnolia Cup. Alex Moore meets her a er a morning on the gallops and discovers a jockey still breaking down barriers – and hears of her emerging passion for motorsport

Photography by Amelia Troubridge

Over Epsom Downs the sky is as blue as Godolphin silks and clear enough to see the arch of Wembley Stadium nearly 20 miles away. It’s been that way since 6am, at which point Khadijah Mellah would have been halfway round the gallops on Military Medal, the first of four racehorses she was exercising that morning. When we meet just a er noon, her working day is complete. Still dressed in jodhpurs, riding boots and a precautionary raincoat, she’s sore and exhausted but, by her own account, living the dream.

“When the sun’s rising and it’s nice weather, I feel like I should be paying for this experience,” says Mellah of her new position at Epsom’s legendary Loretta Lodge racing yard. We’re on the edge of Langley Vale, a mile from the yard, at a point where Mellah reckons certain horses have a habit of acting up. Sometimes they bolt when they realise they’re on the way home, she tells me. No such problems today though. ere’s a crack of thunder and suddenly it’s hailing. “On the other hand,” she jokes, pulling up her collar, “when the weather’s not so good, I feel I’m not getting paid nearly enough.”

It’s almost five years since Mellah won the Markel Magnolia Cup at the 2019 Qatar Goodwood Festival. e story of Britain’s first hijab-wearing jockey made headlines around the world, catapulting the 18-year-old A-level student from Peckham into the spotlight. Great British Racing logged over 1,400 TV and online pieces about her landmark victory, and it wasn’t long before leading talent agency Curtis Brown had signed her up. Such was the magnitude of the win and the circus that followed, even now she finds it overwhelming to look through her scrapbook of newspaper clippings.

“A er the Magnolia Cup, there was all this hype, all this energy, all this publicity,” says Mellah. “I was being invited to the same events as AP McCoy, a giant of the sport, and I’m just a pea. I was invited to ride at lots of di erent yards, but you have to remember, I hadn’t even been riding [racehorses] for three months. And I felt like people expected me to be much better than I was, so I had this huge imposter syndrome, and very little confidence in my ability.” She was invited into the Royal Box at Ascot with Queen Elizabeth II, but says her biggest “pinch me” moment was attending the same awards ceremony as two of her childhood heroes, English heptathlete Katarina Johnson- ompson and 400m sprinter Christine Ohuruogu: “Just to be in the same room as them was insane.”

Some timely words of encouragement from Hayley Turner, the first female jockey to ride 1,000 winners, eventually convinced Mellah she could belong at the sport’s top level, if she wanted to pursue it. “When it comes to interacting with people of colour, I think it’s easy to have subconscious bias, especially in the racing world, but Hayley never had any reservations about getting to know me, which was really refreshing,” recalls Mellah. “She’s been an incredible mentor in many ways, and I’ll always remember a piece of advice she gave me. She said, ‘Don’t compare yourself to other people, don’t worry about how everyone else is doing or what anyone else looks like; just do you.’”

With that in mind, Mellah decided to take a step back from racing and revert to her original plan of completing a degree in mechanical engineering at Brighton University. “Before I got involved in racing, I’d spent years working towards a very di erent goal,” she says prudently. “My dad has always fixed up cars and I really love motorbikes. And while I could see some sort of future in horseracing, I needed to get that [degree] behind me in case I got injured. Something to fall back on.”

During her studies, much of which she completed during lockdown, Mellah kept her toe in the racing world, helping champion jockey turned trainer Gary Moore exercise the horses at Cisswood Racing Stables near Horsham, West Sussex. Alongside ITV Racing’s Oli Bell, she also helped to found the Riding A Dream Academy, a charity that helps young people from diverse communities and disadvantaged backgrounds get into horse-riding. Inspired by Ebony Horse Club, the urban equestrian centre in Brixton where Mellah first learned to ride, the academy o ers taster days, residential weeks and the year-long Khadijah Mellah Scholarship. Already, she says, they’ve exceeded every expectation. “We’ve got loads of young people coming through the ranks who are almost riding at the same standard as I am,” she adds proudly. “So far, eight of our graduates have gone on to work in the racing industry. Every year we’re growing, and we’ve currently got students from Leicester, Solihull, Gloucestershire and London. We’ve got vulnerable kids from the foster system, some with

“We’ve got loads of young people coming through the ranks.

Last summer we ran a residential racing programme and 80 per cent of the students were Muslim”

“I fell in love with motorsport while I was at university. I’ve really got into Formula One”

learning di culties and others with disabilities. Last summer we ran a residential programme and 80 per cent of the students were Muslim.”

Indeed, Mellah has become something of a poster girl within the Muslim community. e academy works closely with the Muslim Sports Association (MSA) and she had a starring role in Nike’s tech pack commercial, sporting a Nike-branded hijab. “A lot of people in my community tend to stay away from the arts and sports and focus on academia because it’s the less risky path to success,” says Mellah, whose mother and father are first-generation immigrants from Kenya and Algeria, respectively. “Riding horses is actually encouraged within our religion; we just don’t typically have the access.”

Having finished her degree, Mellah decided to get back into racing fulltime. She wrote to a number of the country’s top trainers including Jim Boyle and Pat Phelan, both of whom o ered her work, but decided instead to join Adam West in Epsom – partly because of the proximity to London, partly because she knew West wouldn’t give her an easy ride.

“I didn’t want to just be this one-hit wonder,” says Mellah. “I don’t want to be celebrated to the extent I was celebrated last time – I just don’t like not being good at something. Yes, I won that race but I’m still nowhere near being a decent jockey. If I’m representing my community and my people, I want to be as good as I can be. I want to be taken seriously.”

Mellah is currently working towards her amateur racing licence in the hope of getting a few more races under her belt, not least Epsom’s Amateurs’ Derby in August. It’s been another steep learning curve. On her first day working under West, a dog ran onto the track, spooking the horse she was riding, Roly Poly. “He bucked me nice and hard,” she says from behind a trademark smile. “I think I had mild concussion. I’ve fallen o

horses, they’ve chucked me into bushes, thrown me into fences and I’ve even had a horse fall on me. It’s all part of the job.”

ese sporting mishaps are overshadowed, however, by the motorcycle accident she had in 2023 in which she broke her knee, ankle and toes. “Nothing comes close to that,” she says, clutching her knees, which are still swollen and ache badly a er riding. “But that time o only made me realise how fortunate I am to be in this position. It reinforced my love of racing.”

Could Mellah still see herself becoming a professional jockey? “I’m just not sure about the lifestyle,” she says, screwing up her face. “I’d have to be dieting, in the gym or in the bath sweating the whole time. And what with my other commitments, I don’t think I’d do the job justice.”

ere’s another reason, too. “I fell in love with motorsport while I was at university,” she says, sheepishly. “I’ve really got into Formula One. I’d love to do a crossover with [motorsport sensation] Jamie Chadwick – I’ve heard she also rides.” She pauses, clearly excited about the direction our conversation has taken. “Did you know Aintree used to host the British Grand Prix?”

e sun’s come out again and as we hobble towards the grandstand, the young jockey has an admission to make. “I went to Goodwood Revival last year and I can really see myself working in that [motorsport] industry in some capacity. I studied hydrogen combustion engines, so perhaps a job in the E Series, maybe in the media or presenting. As much as I love horseracing and always will, my big plan is to go into motorsport.” You certainly wouldn’t bet against her. And with that, she jumps on her moped and rides o into the Surrey sunset. She’s got a boxing class in an hour. is year’s Qatar Goodwood Festival runs from 30 July–3 August 2024. e Markel Magnolia Cup takes place on 1 August 2024

Goodwood House’s 2024 exhibition tells the stories of women connected with the Estate. Clementine de la Poer Beresford, the Collection’s curator, reveals the passions, power and pioneering spirit of these extraordinary individuals through the artefacts they le behind

For more than 300 years, women have been central to Goodwood’s history. Without the powerful and influential Louise de Keroualle in the 17th century, Goodwood as we know it, and the Dukes of Richmond, would never have existed. Without the determined spirit of Hilda, Duchess of Richmond in the 20th century, the Estate would likely have been sold o to pay crippling death duties. If women have been integral to Goodwood’s existence and continuity, they have also made its past infinitely richer. eir stories, which tell of passion, patronage, charitable work, family and, of course, sporting interests, have the power to interest, enthral and delight. We have much to thank them for. Goodwood’s history is o en told through the Dukes of Richmond, for they largely built Goodwood House and formed the art collection. Some women did contribute to the architectural and interior schemes, but their voices are quieter in the sources. Many more le less visible traces; they may not have le a legacy in brick and flint, paint or porcelain, but they are part of Goodwood’s history, and their stories deserve to be told. HerStory: Women of Goodwood is a celebration of the women associated with the Estate and the Gordon Lennox family, and it brings together portraits, dresses, accessories, letters and photographs to give us a window into their lives. Here, we delve into some of their stories through the objects that enable us to connect with them.

Louise de Keroualle, Duchess of Portsmouth

Louise de Keroualle, mistress of King Charles II and mother of the 1st Duke of Richmond, invites the viewer in this portrait to muse on her status, power and wealth. Her low-cut gown, almost exposing her breasts, the sensuous folds of material and the string of pearls disappearing underneath her bodice help signal to the viewer that she is the King’s mistress. Holding a shell, pearls and coral, Louise is Venus, the Roman goddess of love and desire, who was born of the ocean – a fitting depiction, as Louise was the King’s most loved mistress from 1671 until his death in 1685, and arrived at the Carolean court from her native France via the English Channel. In 1672 Louise bore the King a son and, with her position in his heart secure, she gained enormous power and influence, including titles for herself and her son. Wealth followed in the form of an annual income of over £1,000,000 in today’s money, allowing her to indulge her taste for expensive jewels – note the cluster of black table-cut diamonds that draw her dress together. In the 40 opulent rooms of her apartments at Whitehall Palace, she entertained the King and his ministers, and advanced French interests – the Francophobe English raged that she was “the spy in the bedchamber”. As a woman who wielded power in an age when women were typically barred from positions of influence, Louise was remarkable. She knew it, and proudly proclaimed it in this image.

Lady Emily Lennox

Growing up at Goodwood, Lady Emily Lennox, daughter of the 2nd Duke of Richmond, was high-spirited and an enthusiastic participant in amateur theatricals. Here, she wears a charming white and blue silk costume, donning a white hat with blue ribbon. Emily’s creative streak extended to fashioning the beautiful Shell House at Goodwood with her mother and sister, while her love of the outdoors and nature led to a particular fondness for the canaries and peacocks in her father’s menagerie. Marriage to the dashing Earl of Kildare and future Duke of Leinster meant a new life in Ireland, but she took elements of Goodwood with her, creating a shell house at her new home, Carton, and she wrote to her father to check on the wellbeing of her much-missed birds. Kildare adored his wife, and Emily was fond of him; the couple had 19 children, of whom 10 survived to maturity. Later in the marriage, though, Emily strayed, falling in love with her children’s tutor, and a er her husband’s death, she married him. One of the four famous Lennox sisters – all daughters of the 2nd Duke – Emily was not alone in attracting notoriety; her eldest sister, Caroline, eloped with a politician, and her youngest, Sarah, flirted with the future George III before marrying Charles Bunbury, eloping with William Gordon, and finally settling down with George Napier. It was only Louisa Lennox who led a scandal-free life, dedicating herself to charitable work and finishing her house in Ireland, Castletown.

Mary, Duchess of Richmond was a confident, free spirit, who passed through life “more happily than most”. She attracted criticism for flirting with men other than her husband, the 3rd Duke of Richmond, her lack of tact, her at times unusual choice of attire, and her ability never to tire of social occasions; but none of this seemed to faze her. To her sisters-in-law, the Lennox Sisters, she was distinctly odd and “not the kind of woman” they thought their brother would have chosen. She did not do things in the “Lennox way”. Jealousy and snobbery may have been at the heart of the criticism. Mary’s confidence shines through in this portrait. Wearing Turkish attire, she shows her awareness of the latest fashions – Turkish clothing was all the rage in England in the late 18th century. If her clothes were designed to shout that Mary was fashion-conscious, they also were chosen to reflect her “free” nature, as one contemporary put it. For western women in this period, Turkish costume came to symbolise the relative freedoms Turkish women, with their access to the all-female space of the harem, and their loose, uncorseted garments, were perceived to have. Mary’s creativity is also alluded to, as she holds and points to a decorative scrolling pattern, which we recently discovered relates to the decorative scheme in the Large Library of Goodwood House. While the 3rd Duke has o en been credited with designing the room, we can now write Mary back into the story.

Jane, Duchess of Gordon was renowned for her intelligence, humour and her role as a leading Tory hostess, but she was equally famous for her matchmaking. Ambitious for her poorly dowered daughters, she secured for them three dukes and a marquis, including Charles Lennox, future 4th Duke of Richmond, for her eldest, Charlotte. A er unsuccessfully pursuing Napoleon’s stepson for her youngest, Georgiana, her next target was the Duke of Bedford. When he unexpectedly died, she turned her attentions to his younger brother, and the couple were married within the year. For her matrimonial e orts, Jane was lampooned in popular satires. Here, stout and florid, she is shown running, pursuing the Bedfordshire bull, which gallops away, out of reach. She holds out a blue ribbon, tied together by a bow inscribed with the word “Matrimony”, to noose the bull. e satire makes it clear that the Duke of Bedford has little say in the matter of his forthcoming marriage. Jane’s matchmaking was to have a profound impact on Goodwood’s history. It was through the marriage of her eldest daughter, Charlotte, to Charles Lennox, future 4th Duke of Richmond, that the Estate would be saved financially in the 19th century.

Charlotte, Duchess of Richmond

Charlotte, Duchess of Richmond took delight in holding glittering soirées. When she and her husband, the 4th Duke of Richmond, moved to Brussels to avoid their creditors, she hosted the most famous dance in history, the Waterloo Ball. Charlotte used a hand-painted silk fan on the night, to cool herself, but also to gesture and communicate – as fans had their own language. She perhaps used it to thank her close friend the Duke of Wellington for allowing the function to go ahead – despite the news that Napoleon was advancing. When a messenger arrived mid-way through the evening to announce that Napoleon was much closer than anticipated, Charlotte perhaps employed her fan to exclaim dismay. O cers were ordered to depart and rejoin their regiments, and the bloody battles of Quatre Bras and Waterloo followed, with many fighting and dying in the uniforms they had worn at the ball. Wellington was forever grateful to Charlotte for keeping up morale in Brussels during the days before Waterloo, a erwards presenting her with Napoleon’s campaign chair (which remains at Goodwood). If the fan gives us a glimpse into Charlotte’s role as hostess at this most famous of gatherings, it also reveals her love of the exquisite and the expensive; she le behind a vast array of receipts relating to purchases for gowns of muslin and silk, shoes with silver trim, and enormous plumes of vulture feathers.

Amy, Countess of March’s life was tragically cut short at the age of just 31. But for a life so short-lived, she le behind a remarkable number of possessions that o er us a snapshot of her daily existence. As this illustrated image shows, she enjoyed making photograph albums and decorating them in the style of mediaeval illuminated manuscripts. is was a popular activity among Victorian women, as it improved their drawing and painting skills within the domestic sphere. Amy had a particular flair for it, and whiled away hours creating intricate patterns and collages. Amy’s interest in art extended to compiling catalogues for the pictures at Goodwood and Gordon Castle. ese were labours of love, which she dedicated to her “dear husband”, Charles, Earl of March (the future 7th Duke of Richmond). Amy organised the artworks in chronological order, beginning with the Stuarts and ending with the latest family members. Her detailed descriptions reveal a deep interest in the history of the sitters, as well as the aesthetic quality of the pictures. More than 100 years a er Amy put pen to paper, her grandson, the 9th Duke of Richmond, wrote, “ e family will forever be in debt to Amy for her wonderful achievement.” Today the picture catalogue at Goodwood is still arranged as Amy organised it.