Cars

Fashion Farming Design

Dogs

Horses

Vintage Tech

Food & Living the life

Autumn 2023

The waist is back

Cars

Fashion Farming Design

Dogs

Horses

Vintage Tech

Food & Living the life

Autumn 2023

The waist is back

Welcome to the Autumn/Winter issue of Goodwood Magazine, the final edition for this year.

The past can often feel vividly present, so resonant are the reminders it has left behind, and at Goodwood House the restoration of historic artefacts is something that every so often reveals something new and unexpected about The Collection. A recent restoration of the Godfrey Kneller painting of my ancestor, Louise de Kérouaille, uncovered some surprises lurking beneath the surface of this most familiar of family portraits (p50). Meanwhile, the Motor Circuit, which celebrates its 75th anniversary this year, still echoes with the sounds of racing glories – soon to be relived at Revival (p99). On that front, we also recall two car marques that have enjoyed starring roles at Goodwood: Bristol Cars (p23) and Lotus, that most quixotic and brilliant of British brands, which also celebrates its 75th anniversary this year (p56).

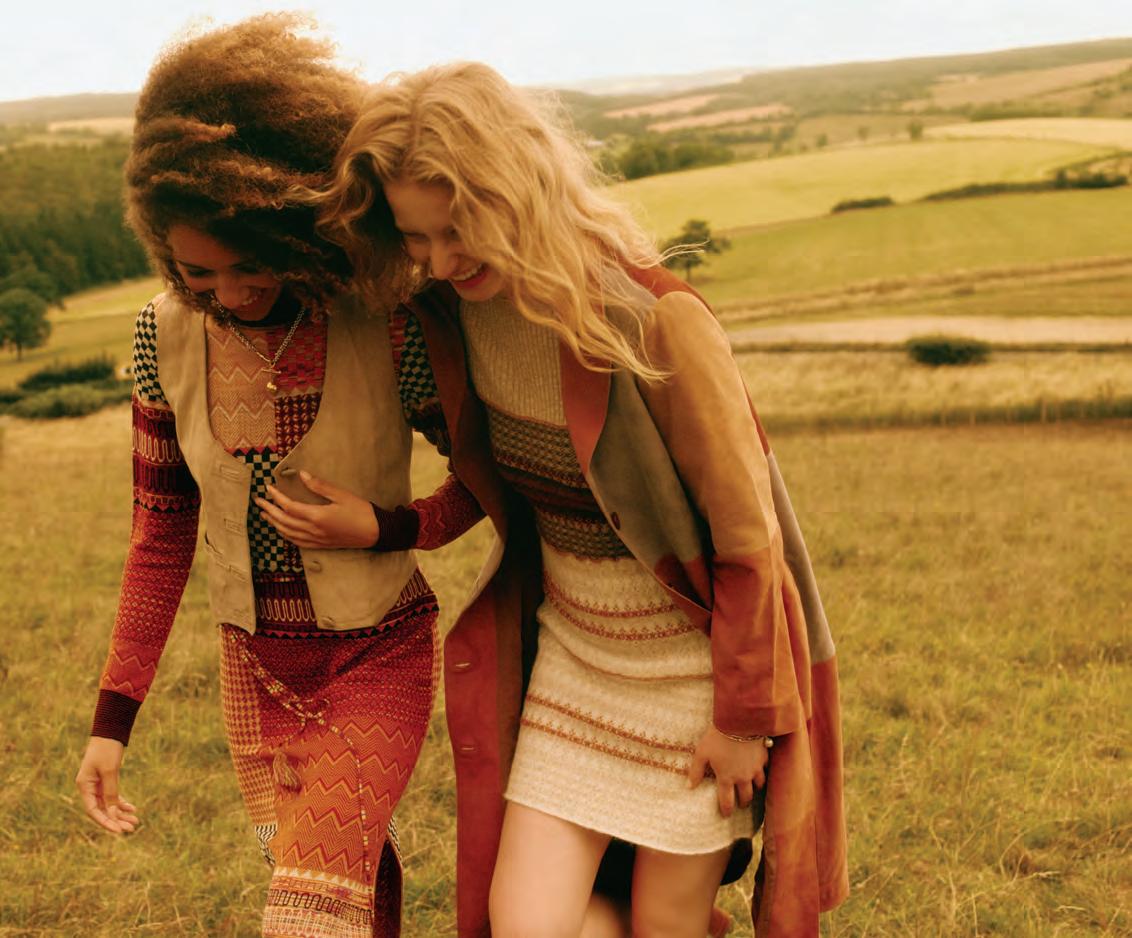

Many come to Revival to celebrate that period of time from 1948-1966 when Goodwood was the spiritual home of motorsport, and to experience a rapturous embrace of vintage clothing, which, as well as being unreservedly glamorous, is a highly sustainable approach to what we wear. Where else would you find what appear to be wartime GIs or fighter pilots dancing the Jitterbug with latter-day Rosie the Riveters? Or rubbing shoulders with hipsters who might have arrived straight from Swinging London? Meanwhile, our fashion story draws upon 1970s rock chick style (p62), a reminder that each generation mines the archives but seeks to produce something new and fresh from them. We also hear from four tastemakers who describe the key vintage pieces that have inspired them in their work (p42). We look forward to the health summit taking place here in the autumn (p34) and cast a hungry eye over the delicious “farm tapas” soon to be served at Farmer, Butcher, Chef – all made with our finest organic and local ingredients (p90).

I very much look forward to welcoming you to Goodwood soon.

The

Kathrin Makowski

Based between Munich and Paris, photographer Kathrin shoots extraordinary fashion and beauty images for Vogue Italia, GQ and L’Officiel. For this issue, her destination was the Goodwood Estate, for an atmospheric fashion shoot with a distinctly retro feel – just in time for Revival.

Tom Morton

Tom writes on contemporary art for magazines such as Frieze and ArtReview and has curated exhibitions for the ICA and the Hayward Gallery. For us, he recalls an unlikely collaboration between major 20th-century artists and the military, which created camouflage as we know it today.

Simon de Burton

Simon is a motoring and lifestyle journalist who writes for The Telegraph, How To Spend It, GQ and Vanity Fair

As Revival prepares for its classic motorbike parade, he investigates the growing appeal of vintage motorcycles to high-end collectors.

Max Décharné

Max is an author, journalist and musician whose writing has appeared in MOJO, The Spectator and The Guardian. His latest book is an expanded edition of his 2005 history of the King’s Road. For us, he looks back at the role of the street in the influential fashions of “Swinging London”.

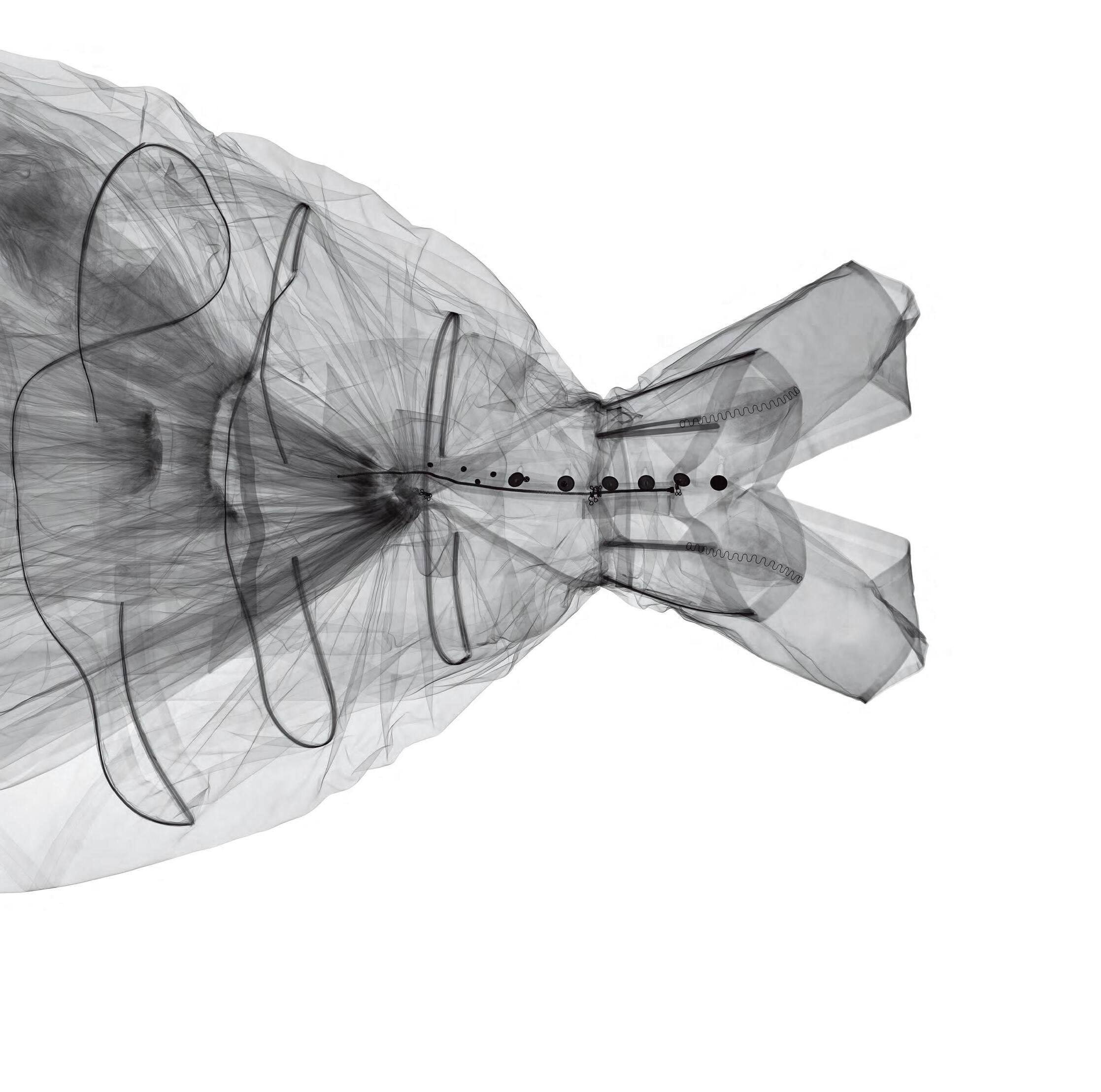

Nick Veasey

Artist Nick Veasey specialises in creating X-ray images of scenes and subject matter that would never normally be X-rayed. His work is held in many museum collections, including the V&A’s, and we’re pleased to say you can also see it on the cover of this issue.

Anna Maxted

The author of seven novels, Anna also writes for The Telegraph and other newspapers. For this issue, ahead of the exciting new health and wellness summit coming to Goodwood, she speaks to one of its key participants: French biochemist, author and glucose expert Jessie Inchauspé.

Editors Gill Morgan

James Collard

Deputy editor

Sophy Grimshaw

Art director

Sara Redhead

Design

Luke Gould

Jess Lee

Head of Editorial for Goodwood Catherine Peel

catherine.peel@goodwood.com

Junior picture editor Max Carter

Sub-editor Damon Syson

Picture editor Joe Hunt

Project director Sarah Glyde

Goodwood Magazine is published on behalf of The Goodwood Estate Company Ltd, Chichester, West Sussex PO18 0PX, by Uncommonly Ltd, 30-32 Tabard Street, London, SE1 4JU. For enquiries regarding Uncommonly, contact Sarah Glyde: sarah@uncommonly.co.uk

© Copyright 2023 Uncommonly Ltd. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced without prior permission from the publisher. While every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of the information contained in this publication, the publisher cannot accept responsibility for any errors it may contain.

Inspired by one man’s dream to create the ultimate sportscar. Together we will colour the next 75 years.

variations in weather,

may

reflect

Porsche 911 Turbo S official WLTP combined fuel consumption 23.0-23.5 mpg, WLTP CO₂ combined emissions 278-271 g/km. Figures shown are for comparability purposes only and not real life driving conditions, which will depend upon a number of factors including any accessories fitted, topography and road conditions, driving styles, vehicle load and condition.12 Contacts

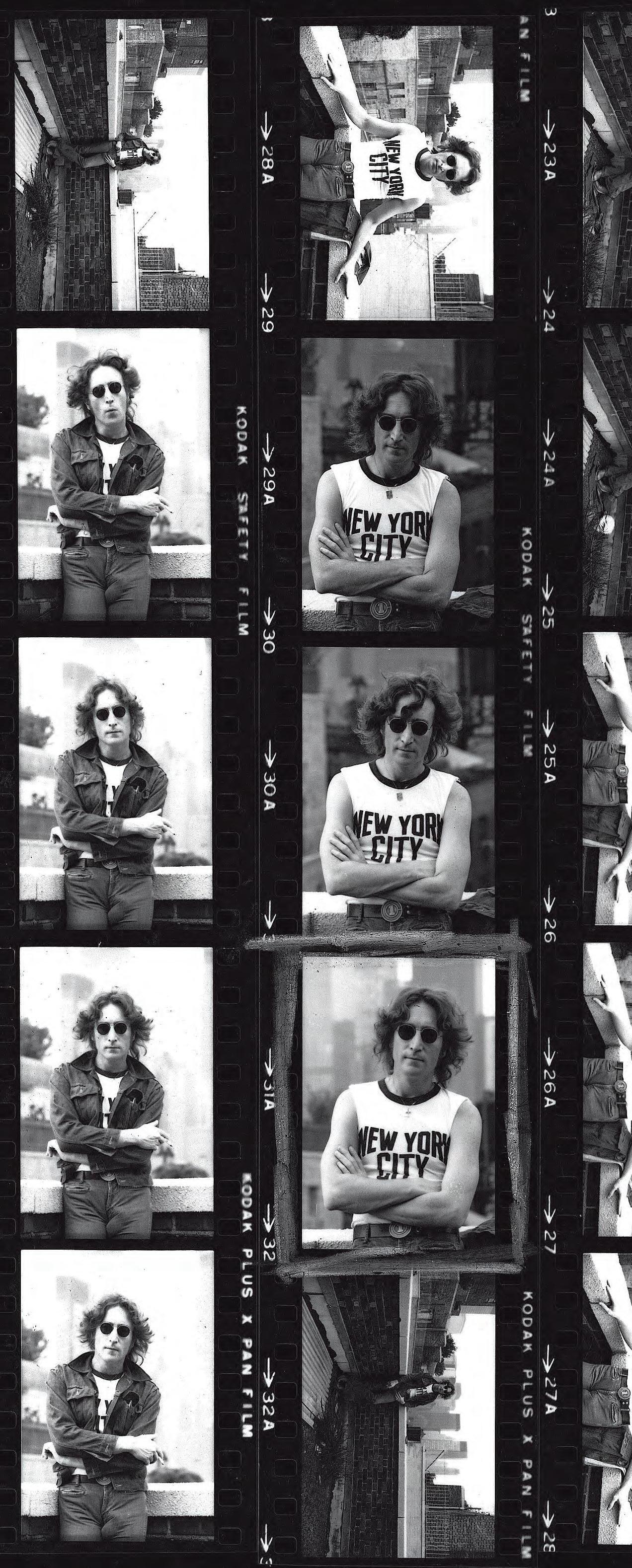

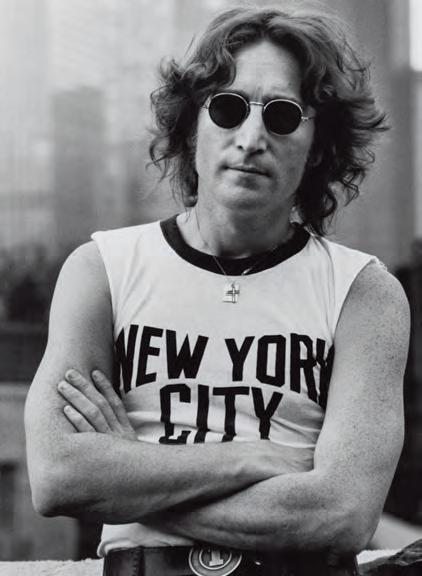

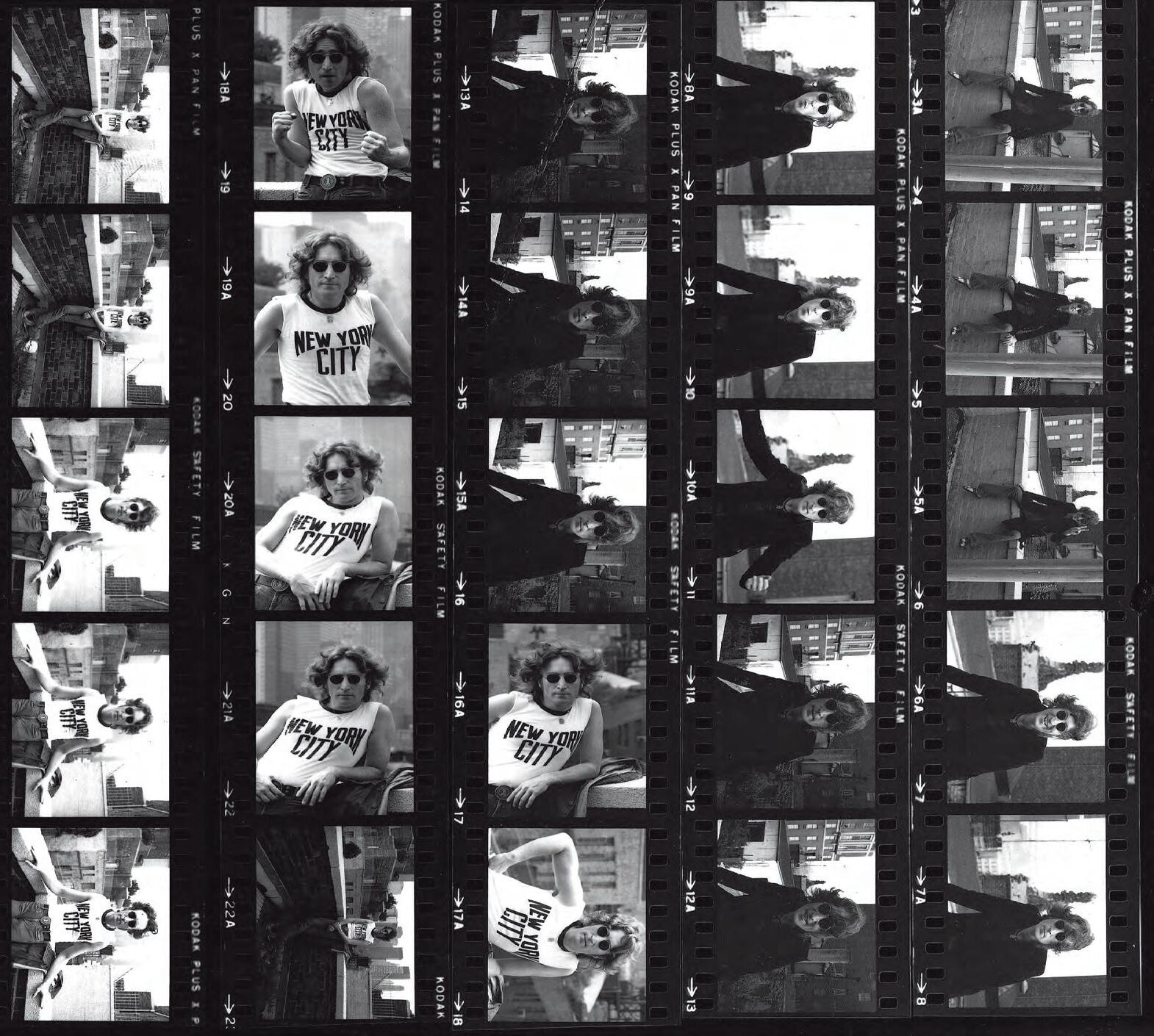

Bob Gruen’s iconic rooftop shoot in New York featuring John Lennon, 1974

14 Horse sense

Recent research suggests that the bond with our equine companions goes back a lot further than we thought

16 Lofty ideals

With sustainability an evergrowing priority, industrial chic is back in demand

18 We could be heroes

Meet photographer Russell Cobb, famed for his distinctive portraits of Revival revellers

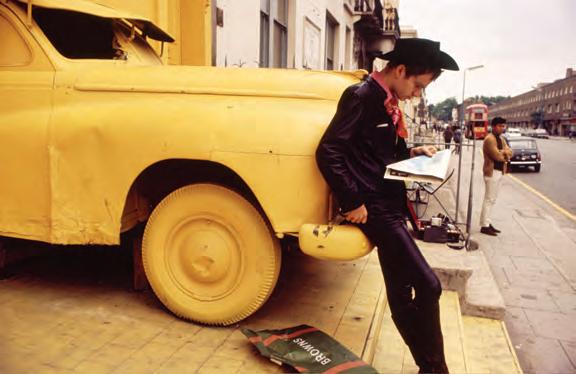

20 Long live the King’s Road

At the height of the 1960s this hallowed Chelsea thoroughfare was the centre of all things groovy, as a new book confirms

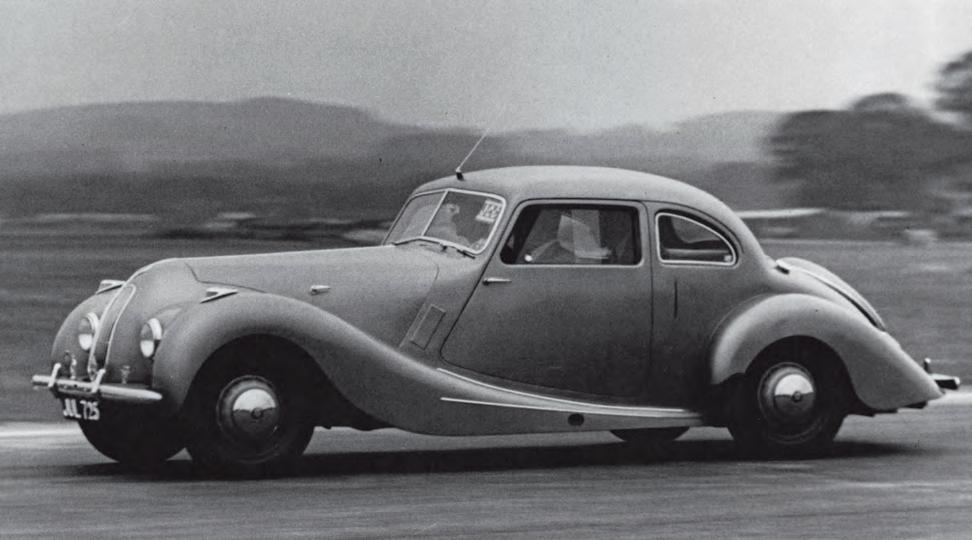

23 English eccentrics

They don’t make ’em like that any more – a phrase that applies to Bristol Cars and its former owner, Tony Crook

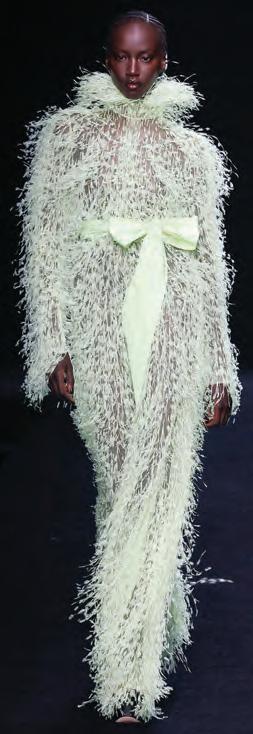

24 Bow belles

That fashion stalwart, the bow, is back on the catwalks, but be warned: this time around it’s bigger and sassier than ever before

26 Life at full throttle

A celebration of racing driver and automotive constructor Carroll Shelby, who was born 100 years ago

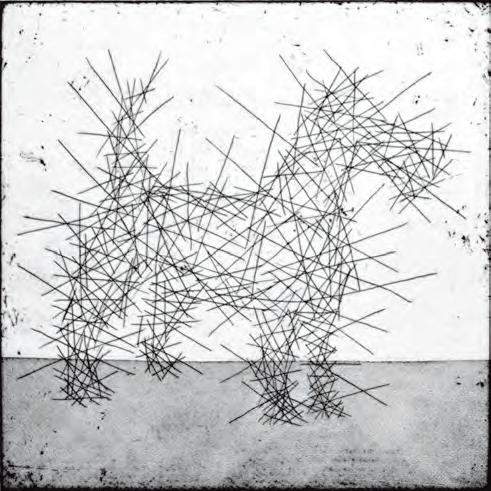

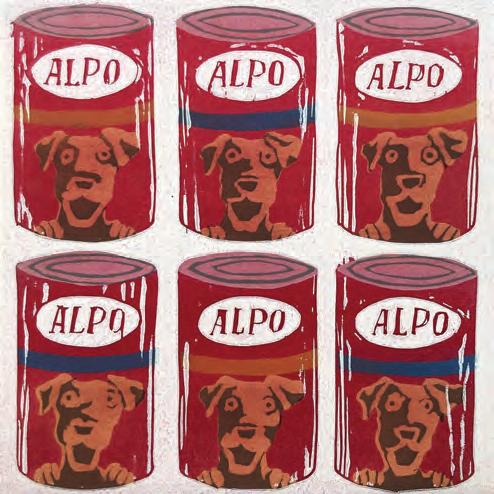

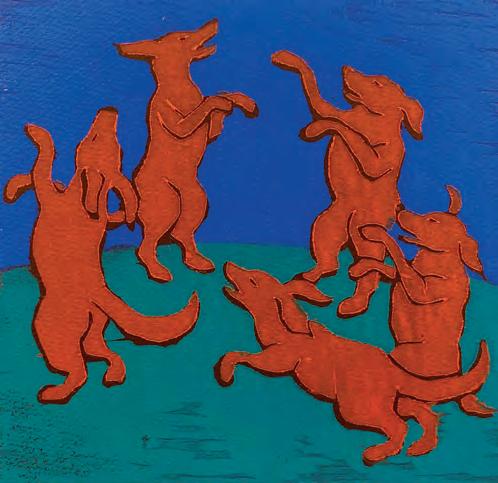

28 Spot paintings

Mychael Barratt has spent years imagining the dogs of the world’s greatest artists, from Warhol to Van Gogh

30 Creature comforts

Tableware designers are once again looking to the natural world for inspiration

32 Riding high

As Taschen releases a new tome on vintage motorcycles, these classic machines have never been more desirable

34

Food for thought

Discover what’s in store at the upcoming Goodwood Wellness Summit, and meet speaker Jessie Inchauspé, aka the Glucose Goddess

42 Back to the future

Contemporary creators recall the vintage pieces that have inspired them – from Rapha founder Simon Mottram’s 1960s cycling jersey to jeweller Glenn Spiro’s Cartier Model A Ford replica

50 Layers of intrigue

Art restorer Ying Sheng Yang describes how the process of bringing a portrait at Goodwood House back to its former glory revealed hidden clues about its past

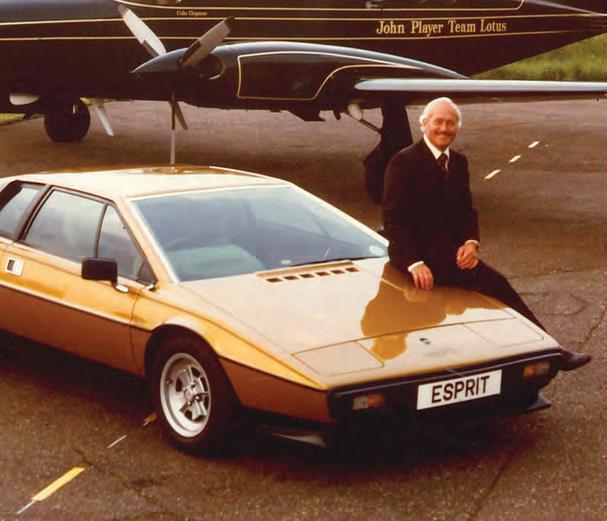

56 Lotus blooms again

As Goodwood Revival prepares to celebrate the marque’s 75th birthday, Ben Oliver recalls its chequered past. But are the good times about to roll again for Lotus?

62 On the road again

Dust off your cowboy boots: Seventies rock chick style is back. For Laurel Canyon inspiration and a cool soft-top Mercedes, check out our sun-kissed fashion shoot

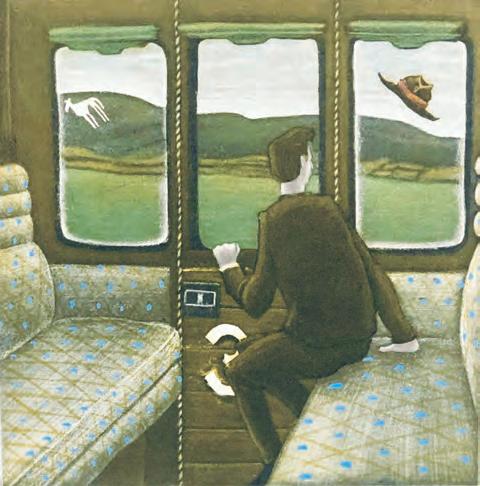

76 Lost and found Our intrepid reporter sets out in search of the thousands of miles of footpaths that Don’t Lose Your Way campaigners claim have vanished from our countryside

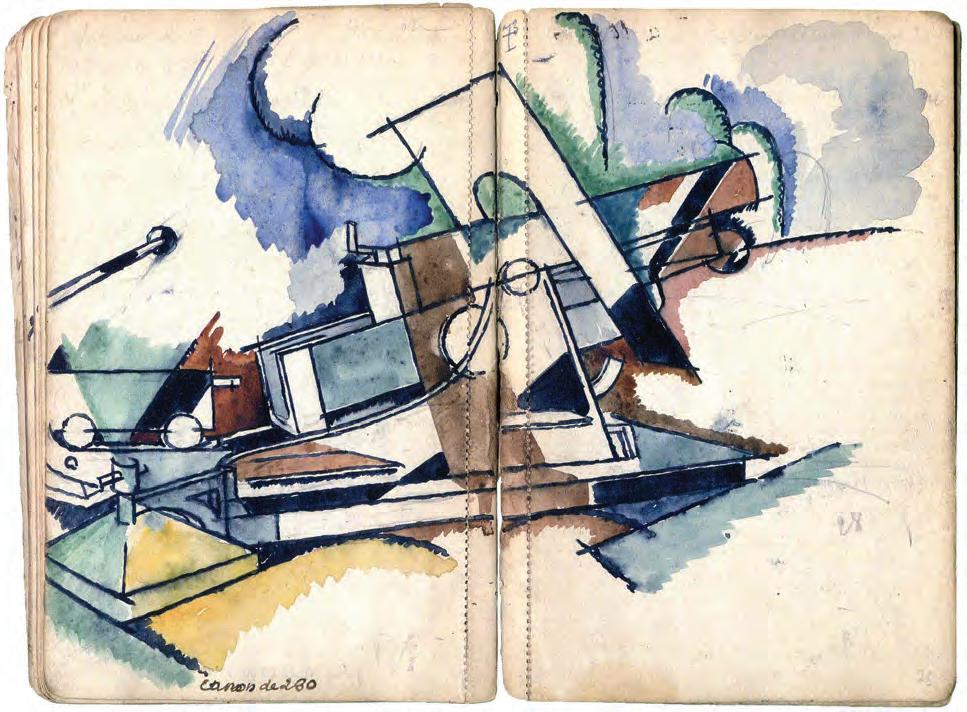

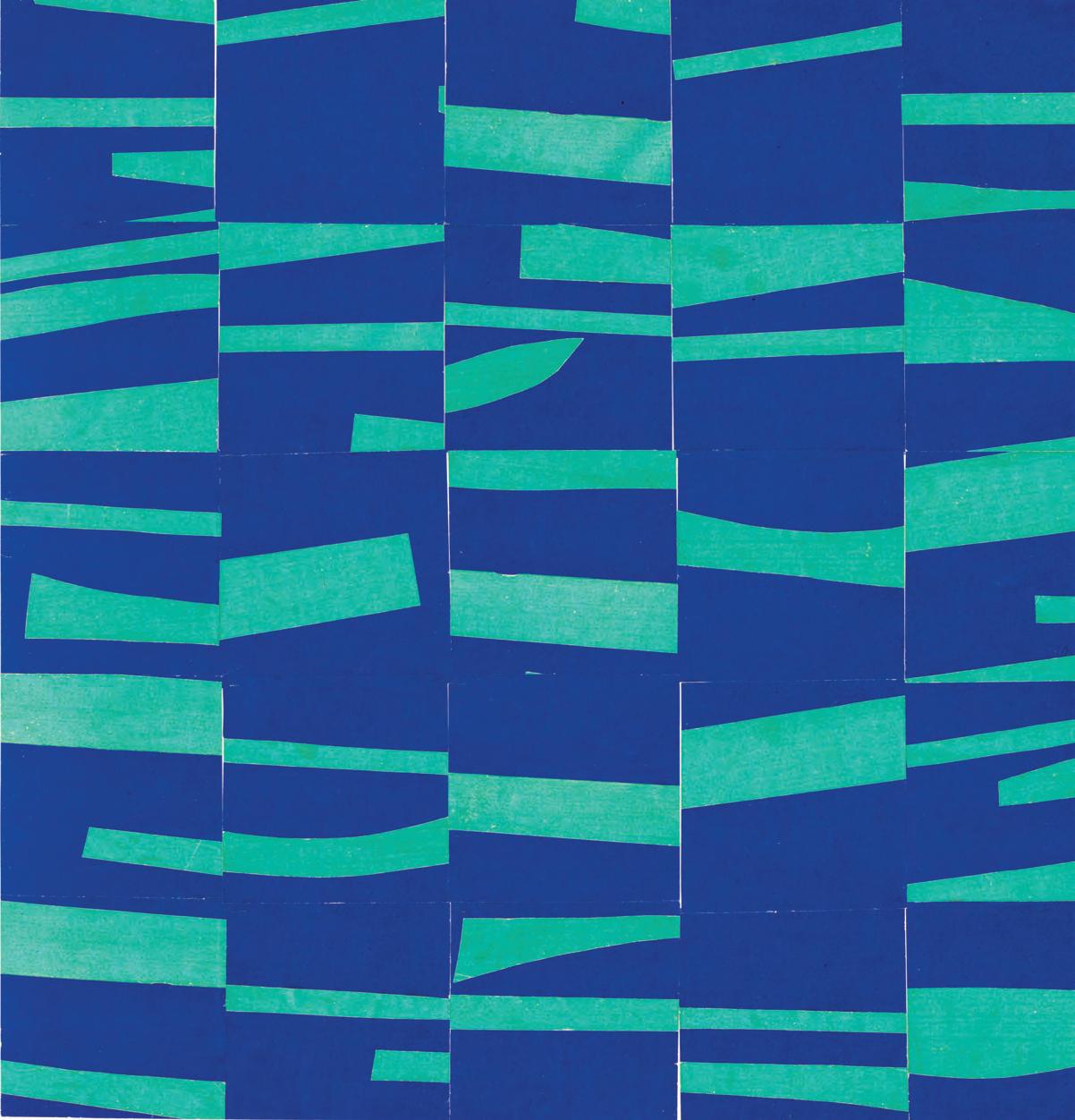

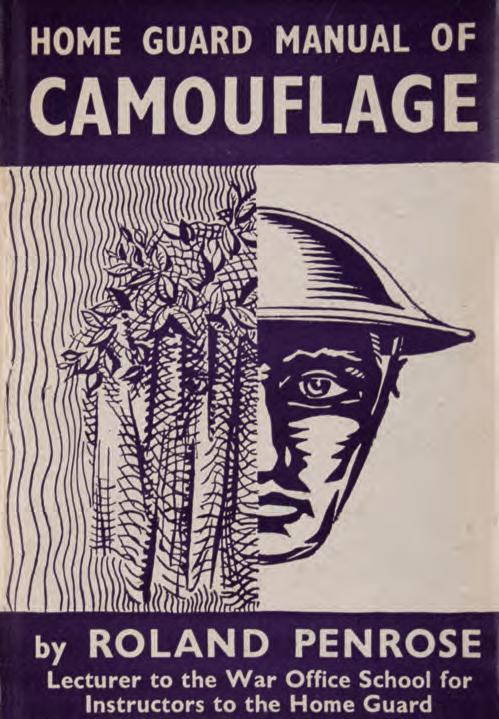

82 The art of war

The original camouflage patterns, and their “dazzle” equivalent for ships, were brought into being through an unlikely partnership between celebrated avant-garde artists and the military

90 Flavour explosion

Goodwood executive chef Mike Watts describes how the new “farm tapas” at Farmer, Butcher, Chef restaurant came into being – and shares some tasty recipes to try at home

97 Calendar

The unmissable events at Goodwood this autumn, including Goodwood Revival and Greenkeepers Revenge

104 Lap of honour

The Repair Shop’s Dominic Chinea on the creativity of Goodwood Revival, restoring his dream car, and why the workshop is his happy place

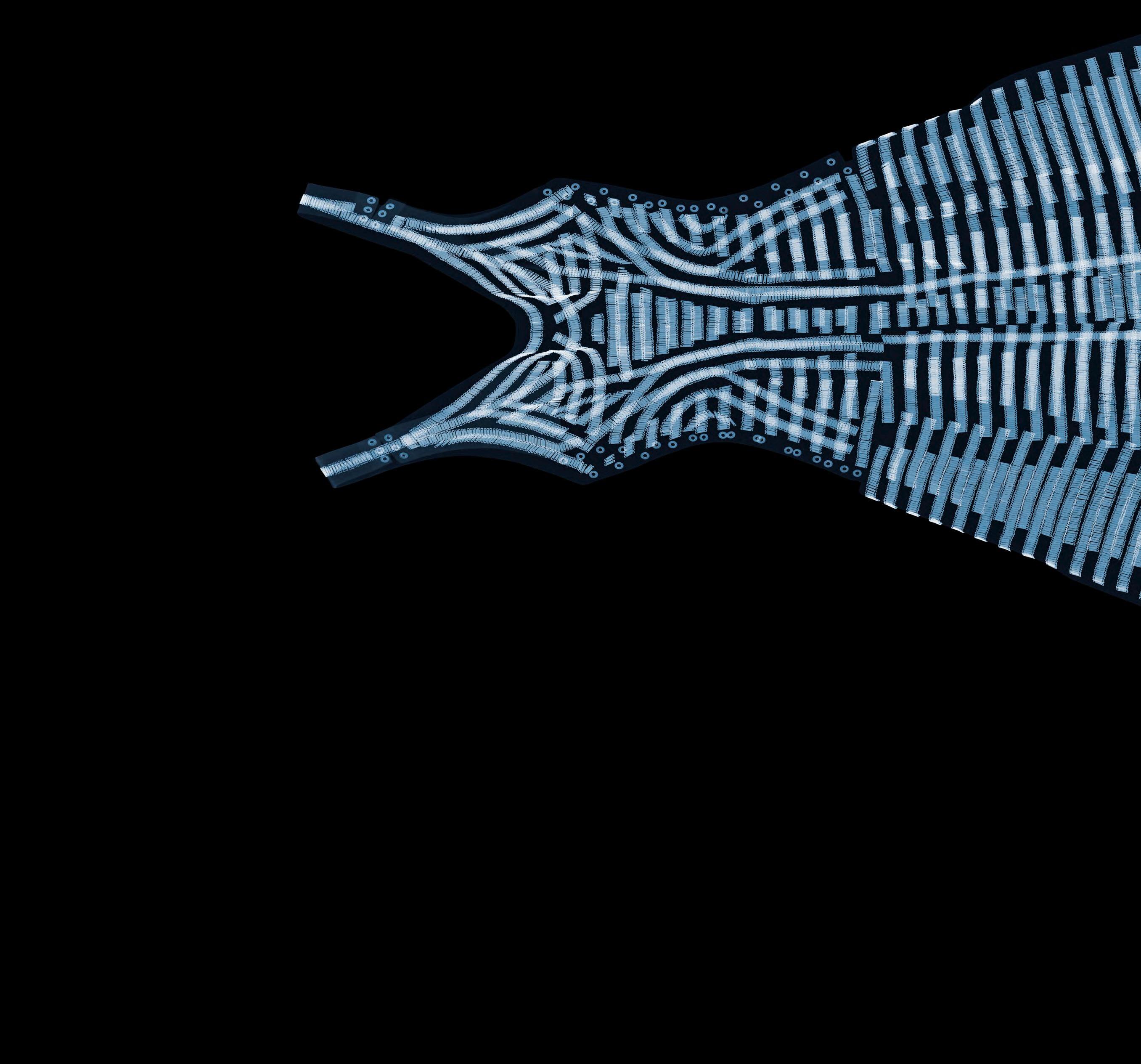

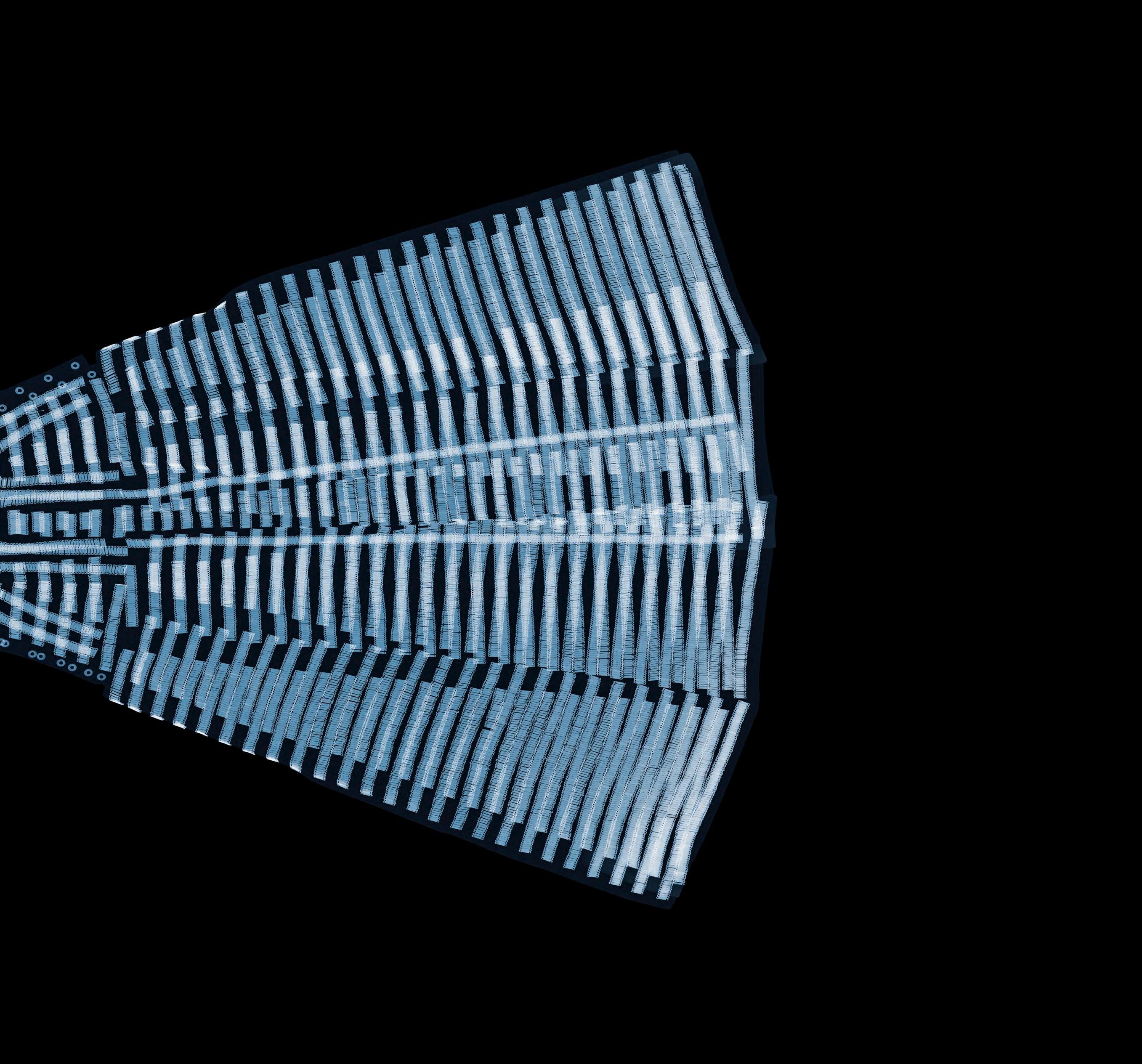

“Is the waist making a comeback?” Vogue asked lately, reporting on collections “awash with swishing, waist-whittling silhouettes” – which seemed to hark back to Christian Dior’s New Look and his “Bar” suit, the curvy lines of which grace our cover. The waist never really went away, clearly, but designers strive to transform how we perceive that form. Dior’s bold debut collection in 1947, in his own words, “accentuated the waist, the volume of the hips… emphasised the bust”. The X-ray photography of Nick Veasey reveals some of the architecture underneath Dior’s silhouette, which involved corsetry, padding to exaggerate the hips, petticoats and, controversially in a time of clothes rationing, full skirts made with metres of expensive fabric. Dior’s New Look marked a clear shift from the 1930s and 40s styles which preceded it – think Dietrich in trousers, or Coco Chanel’s LBD, or the millions of women who’d donned wartime uniforms – but just how new was it? For it turns out Dior had learned the old-fashioned techniques of corsetry and petticoats while designing the costumes for a 1942 movie set in France’s Second Empire, a strand of overtly feminine glamour exemplified in the 1955 ballgown designed by Dior’s arch rival, Cristóbal Balenciaga, shown here in X-ray form. Dior had set the fashionable shape for a decade.

Rock and roll photographer Bob Gruen shares – for the first time – the contact sheet from his famous rooftop shoot featuring John Lennon in a New York City T-shirt

Words by Sophy Grimshaw

Words by Sophy Grimshaw

“One of the reasons I like this picture so much is that I felt John wasn’t posing as a New Yorker – he was a New Yorker,” says the celebrated music photographer Bob Gruen of his rooftop portrait of his friend John Lennon. The former Beatle had called the city home since 1971, finding – despite the Beatles’ immense popularity in the States – some respite from the intensity of his fame in the UK.

On 29 August 1974, Gruen, then 29, and Lennon, 33, went up to the roof of Lennon’s penthouse on East 52nd Street – initially to take some close-ups of Lennon’s face for the cover of his forthcoming album, Walls and Bridges. “Then he suggested that we take more pictures, so we would have the publicity kit ready when the album was released,” remembers Gruen, whose vast archive includes well-known images of David Bowie and The Rolling Stones. Gruen was also a key documentor of the 1970s New Wave scene, from which bands such as Blondie emerged. “We were on the roof, John in his black jacket with the entire Manhattan skyline visible behind him. I had an idea to play on the New York City theme, and suggested he put on the New York City T-shirt that I’d given him about a year before. I used to buy them from the guys who sold them on the street in Times Square and cut the sleeves off with my Buck Knife.”

One image from that day, of Lennon facing the camera, arms folded, would ultimately become one of Gruen’s best-known photographs, later described as “iconic” by New York Magazine. “The crossed arms and cut-off shirt say New York City attitude,” says Gruen. “New York City is represented as a strong, independent idea, and John is as well. We had a good time that day.”

To purchase photographs from Bob Gruen’s archive, visit bobgruen.com

The latest discoveries about horses – and our interactions with them – suggest that we humans still have a lot to learn about our equine companions

Words by Alex Moore

“From horses, we may learn not only about the horse itself but also about animals in general, indeed about ourselves,” said the evolutionist George Gaylord Simpson, “and about life as a whole.” The late paleontologist’s research into horses looked back 60 million years (whereas the earliest dog fossils are only around 33,000 years old). And yet, in some respects it feels like we’re still getting to know what horses are actually capable of –and indeed how long we’ve enjoyed their company.

In spring 2023, archaeologists from the University of Helsinki found new evidence to suggest that humans may have ridden horses since 3,000 BCE – some 1,000 years before the earliest known artistic representation of a human astride a horse. Yamnaya skeletons discovered in eastern Europe displayed marks associated with “horseman syndrome” – the result of the thigh bones, pelvis and lower spine adapting to the biomechanical stress caused by the specific repetition of horseback riding.

Elsewhere, new research published in 2023 by scientists at France’s University of Tours has proved that horses are able to cross-modally recognise women and men. That means they can associate women’s faces with women’s voices and men’s faces with men’s voices, which may suggest that horses generalise their experiences with one person to other people in the same category (ie, women or men).

“We’ve been studying horses for centuries, but it’s only in the past 10-15 years, since the sequencing of the human genome, that we’ve really been able to understand them,” says Professor Emmeline Hill, an Irish equine geneticist credited with discovering a gene for speed in horses. “With these new technologies it’s like opening the bonnet of a car and inspecting the engine, as opposed to evaluating it merely based on what it looks like from the outside.”

Hill’s discovery of the “speed gene” – and the advent of Equinome, her subsequent commercial venture – revolutionised the bloodstock market, allowing horse-owners to determine the optimum racing distance for their Thoroughbreds. But it also paved the way for further genetic research into animal health and welfare. Hill and her team at University College Dublin have since discovered what they describe as the “motivation gene”, and more recently, a gene associated with stress or temperament.

Very often there are many genes that contribute to an individual trait, and in those cases “we develop prediction models known in medical parlance as polygenic risk scores”, explains Hill. “We are particularly interested in health and disease traits and how inbreeding impacts the viability of horses actually racing. It’s sad to say that around 30 per cent of Thoroughbreds never make the start line, and reducing inbreeding can certainly mitigate against that. At a time when horseracing is under the spotlight in terms of welfare, I think that it is incumbent on the industry to use whatever tools are available to protect its assets.”

Thousands of years into humans’ relationship with horses, it’s clear that we’re still only just discovering the skills and traits of our equine companions.

Industrial chic has been around for decades, but with sustainability an ever-growing priority, the demand for artfully upcycled pieces and salvaged furnishings is hitting new heights

Words by Emma O’Kelly“For me, it’s Brutalism every time,” says Anna Zaoui, the co-founder of luxury interiors platform Invisible Collection. “I could easily live with exposed steel beams in my house.” Indeed, it was the light industrial style of a Marylebone mews building that first seduced Zaoui when she was searching around for a suitable showroom for Invisible Collection. “It has echoes of the Maison de Verre,” she proclaims, pointing to steel beams, a floating mezzanine and simple unadorned windows.

When it was built in Paris in 1932, the Maison de Verre was a shockingly avant-garde mix of “industrial” materials – glass, steel, concrete – and traditional home décor. Today it looks as modern as it ever did, and it has acquired cult-like status among design lovers. Furniture by its creator, French architect Pierre Chareau, forms a solid canon of collectible design from this period. Price tags are staggering: midcentury aluminium doors, sideboards and chairs from the late French metalworker Jean Prouvé, for example, fetch upwards of $100,000 at auction houses and galleries.

But there are many pieces beyond those by highly prized midcentury masters, and the desire for industrial chic is not going away. As the need to upcycle, re-use and reclaim increases due to the climate crisis, so too do the pressures to salvage utilitarian workbenches, steel worktops, old school desks and factory fixtures and fittings. “The raw and unfinished look of industrial design creates an environment that is not only aesthetically pleasing but also practical and kind to the environment,” says London-based interior architect Shalini Misra. “For residential projects, especially in lofts or buildings with an industrial history, bare bulbs with metal fittings and railway sleepers upcycled into flooring or furniture work well. In one space, we used mirrors with frames made from old metal cogs.”

Artist couple Draga Obradovic and Aurel Basedow scour thrift shops and markets for midcentury finds which they rework in contemporary finishes in their Lake Como studio. Their Heritage collection of sideboards, chests of drawers and consoles come with screen-printed facades, brass detailing and finishes in shellac and epoxy resin.

Industrial pieces also have the added advantage of being hard-wearing and adaptable. For more than 30 years, Adam Hills and Maria Speake of salvage maestros Retrouvius have conjured kitchen floors from reclaimed school desks, splashbacks in slices of old stone, living room walls from terrazzo columns transplanted from department stores. Their latest idea? Using old cheeseboards as cladding on walls, drawer fronts and shelving to bring a rustic cabin-like warmth to a home.

With the demand to reuse, repurpose and recycle definitely not going away any time soon, the industrial chic look might be here for the long haul.

Boldly reflect your character. Transform the purity of Ghost into your personal masterpiece. Contact us to discover more about commissioning yours.

Fuel economy and CO₂ results for Rolls-Royce Ghost: NEDC combined: CO₂ emissions: 343 g/km; Fuel consumption: 18.8 mpg / 15.0 l/100km. WLTP combined: CO₂ emissions: 359-347 g/km; Fuel consumption: 17.9-18.6 mpg / 15.8-15.2 l/100km. Figures are for comparison purposes and may not reflect real-life driving results, which depend on a number of factors including the accessories fitted (post-registration), variations in weather, driving styles and vehicle load. All figures were determined according to a new test (WLTP). The CO2 figures were translated back to the outgoing test (NEDC) and will be used to calculate vehicle tax on first registration. Only compare fuel consumption and CO2 figures with other cars tested to the same technical procedure.

© Copyright Rolls-Royce Motor Cars Limited 2023. The Rolls-Royce name and logo are registered trademarks.

Russell Cobb’s distinctive photographs of the most meticulously dressed revellers at Goodwood Revival have become part of the event’s appeal

Words by Sophy Grimshaw“It’s a form of mutual time-travel,” says Russell Cobb, a photographer who has become well-known for his evocative images of re-enactors in vintage clothing at Goodwood Revival. Moving through the crowds (“The Duke gave me a kind of licence to roam,” as he puts it), together with lighting director Paul Williams, Cobb works quickly but takes images that have a filmic quality more usually associated with a lengthy studio set-up. “I go for a cinematic, storytelling feel,” says Cobb, who also notes that most people’s sense of a 1940s aesthetic, for example, is largely based on movies set during that era.

The re-enactors in this photo, Freddie and Eve, are among a great many splendidly attired Goodwood regulars that Cobb has got to know over the years (to get the helter-skelter in shot, he took the photo almost lying down). He even has some Revival-goers who discreetly collaborate with him as scouts, combing the crowd for the best-dressed attendees. “One guy, Dickie, is a film costumier and really knows his stuff. We are looking for something much more than just fancy dress. Re-enactors are such an important and distinctly British subculture – one that is still quite overlooked.”

Cobb enjoys dressing the part himself, and has previously worn some detailed military uniforms and costumes as he worked, keen not to dilute the visuals of the event for others by showing up in modern dress. For the last couple of years, he has attended Goodwood wearing a distinctive 1950s cardigan covered in badges (look out for it if you’re hoping for a chance to be photographed by him). Cobb admires his subjects but found that some of the more full-on vintage looks got in the way of his work. “One year at Revival I worked wearing a vintage leather jacket and a rollneck,” he remembers, “which by midday, when the sun was blazing, I realised wasn’t such a good idea…”

To see more of Russell Cobb’s Goodwood Revival images visit cobbphoto.com

For lovers of vintage fashion, there’s nowhere quite like this hallowed stretch of tarmac, says the street’s unofficial “biographer”

Words by Max DécharnéIf there is one year in which the idea of Swinging London burned itself into the popular imagination, 1966 has a better claim than most; with the King’s Road, Chelsea, as its epicentre. On 15 April, the new edition of TIME magazine landed on doorsteps across America, with a cover story titled “London: The Swinging City”. And as fashion trailblazer Mary Quant, who had opened her boutique on the street, would claim in her autobiography, “Chelsea suddenly became Britain’s San Francisco, Greenwich Village and the Left Bank. The press publicised its cellars, its beat joints, its girls and its clothes. Chelsea ceased to be a small part of London; it became international. Its name interpreted a way of living and a way of dressing far more than a geographical area.”

The district had been home at one time or another to everyone from Henry VIII to Oscar Wilde, Mozart to Judy Garland. But anyone in the 1950s venturing the opinion that Chelsea would soon be attracting worldwide attention in the fields of avant-garde fashion, cinema, rock music and theatre might well have been laughed at. Yet now, TIME ’s article breathlessly claimed that “in a once-sedate world of faded splendour, everything new, uninhibited and kinky is blooming at the top of London life”. As Mary Quant told me, at the height of the hysteria, “American news magazines and TV were often filming both sides of the King’s Road at the same time.”

What made this street so different from the average shopping experience was the likelihood of spotting one of the many pop celebrities who patronised the area, and the sense that the fashions were more extreme, the skirt-lengths shorter, and the boutiques themselves unlike anything elsewhere. They were, somehow, simultaneously intimidating yet inviting. The now-legendary Granny Takes a Trip used its shop window as a kind of gallery space rather than as a functional way to display goods – a pioneering idea at that time. The entire window was at one point painted as a picture of Mae West’s face, opaque except for the lips – later to be replaced by the front half of a 1947 Dodge motor car, sticking out into the street.

I asked one of the shop’s founders, John Pearce, about its clientele. The Small Faces often bought clothes there, he said. “And The Beatles, and the other lot [The Rolling Stones], Brigitte Bardot, Warhol… everybody.” Director Michelangelo Antonioni also visited Granny’s in the spring of 1966, looking for a suitable dress for a key scene in his new film. As Pearce recalls: “There’s a poster for Blow-Up, with [the model] Veruschka on the floor in a beaded dress. He came into the shop for that.”

Designs from King’s Road boutiques often showed up in the flurry of mid-1960s films and TV dramas that sought to capture the spirit of the times. They were also seen in glossy magazines and on music shows like Top of the Pops, worn by musicians and audiences alike. This was a club you could join, if you knew where to shop – and were confident enough to step inside.

The idea of Swinging London was derided by many locals as overstated. One letter in response to the TIME story read, “For the year’s most ridiculous generalisations, you deserve to swing indeed.” Nonetheless, the lasting impact of Chelsea in those days is undeniable – in much the same way that the fashions emerging a decade later from Vivienne Westwood and Malcolm McLaren’s King’s Road shop, which clothed the Sex Pistols and other punk pioneers, would spread a different revolution around the world. Long after the original 1960s boutiques closed, their styles – and the myth – would endure. The newly expanded edition of Max Décharné’s book “King’s Road – The Rise and Fall of the Hippest Street in the World” is out now (£25, Omnibus)

Building luxury grand tourers by hand, Bristol Cars was a classic British marque with a cult following – and a charismatic owner who divided opinion. Can it now be reinvented for a new era?

Words by Alex MooreThe founding of Bristol Cars happened almost by accident. The Bristol Aeroplane Company (BAC) started making automobiles shortly after the end of World War II to keep its 70,000 employees busy once the demand for aircraft and aircraft engines diminished. But in 1945 BAC absorbed Frazer Nash, the UK’s pre-war BMW distributor, and set about building its first car, the delightfully curvaceous 400 coupé, launched at the Geneva Motor Show in February 1947. It may have borrowed its engine from the BMW 328, its body from the 327, and its chassis from the 326, but the 400 left all three in the dust.

Freddie Gordon Lennox, the 9th Duke of Richmond and Gordon, owned a 400 and famously used it to open the Goodwood Motor Circuit for the UK’s very first post-war public motor racing track meeting on 18 September 1948. Exactly 50 years later, the then Lord March (now the 11th Duke of Richmond) drove that same Bristol at the inaugural Goodwood Revival.

However, while the marque’s early years may have produced some of its finest cars, this period was perhaps not its most memorable. That honour lies with Tony Crook, Bristol Cars’ proprietor for nearly 50 years. Crook became far more than just the face of the brand – indeed, his quirky, often cantankerous personality and unconventional business acumen would sometimes outshine the remarkable cars he sold.

Crook claimed he knew from the age of six that he wanted to be a racing driver. And after a stint as a fighter pilot in the RAF during WWII, he followed his dream, becoming, as described by his friend Stirling Moss, “brave and fearless in action, but ultimately held back, both on the track and when participating in the glamorous lifestyle surrounding the racing world”. Coincidentally, it was a crash involving both men –seven hours into the Nine Hours race at Goodwood in 1955 – that abruptly ended Crook’s racing career.

It was at this point that he turned his attention to selling cars. He and George White (son of Sir Stanley White, founder of BAC) bought Bristol Cars in 1960, before Crook became sole distributor in 1966. In his book, Mr Bristol – The Remarkable Life of TAD Crook, Michael J Barton compares their partnership to another famous duo: “Royce the engineer, made the best car that he could, regardless of cost; Rolls the racing driver, pioneer aviator and socialite, excelled at selling them. Similarly, White made the best car, and Crook, the racing driver and English gentleman with impeccable manners, found the customer.”

Quite how impeccable those manners were depends on who you speak to. If Crook didn’t like the cut of your jib, you wouldn’t be welcome in the showroom, let alone permitted to buy a car. “Tony was incredibly difficult to deal with,” recalls Simon Draper, co-founder of Virgin Records, who owns six Bristols. “But they are such rare and well-constructed cars, you’d just have to put up with him.”

‘‘His bantering concealed some beautifully detailed planning and meticulous execution, just as in his racing,’’ wrote motoring journalist LJK Setright in his 1998 book A Private Car: An Account Of The Bristol, which was published by Draper’s Palawan Press. Yet for all his charms, Crook couldn’t stop his beloved project going the same way as countless English marques before it. He was partially bought out and subsequently forced out in 2007, and after that Bristol Cars slowly fizzled into liquidation.

Epilogue: Essex-based investor Jason Wharton has acquired the intellectual property rights to Bristol Cars and plans to transform it into a ‘‘leading British electric vehicle company’’ by 2026, just in time for its 80th anniversary. Would Crook approve? Hard to say. Maybe not. But he did like to surprise people.

From the girlish to the gargantuan, bows are back. But be warned: this season’s variations are more punk than princess

Words by Alice Newbold

Words by Alice Newbold

Few fashion trimmings set romantics’ hearts aflutter quite like the bow, a functional yet frivolous embellishment steeped in history, but which looks newly fresh for autumn/winter 2023. Despite stealth luxury (thank you, Succession) dominating headlines and straighttalking style topping the trend leaderboard, there will always be bows: sweet, twirling gossamer lengths, bold cartoonish delights and Audrey Hepburn-esque ribbons that, despite the industry’s overarching mood, feel right for now.

This season, bows are less pretty, more punchy thanks to the likes of Valentino, where creative director Pierpaolo Piccioli sent a particularly memorable lattice-work dress crafted entirely from cherry-red bow ties down the runway. Worn over a sky-blue shirt and classic black tie, the directional take on eveningwear made a statement about the bow’s new direction: punk over princess – a sentiment echoed at the Vivienne Westwood show, where the legendary designer’s successor, Andreas Kronthaler, kept her nonconformist spirit alive via vibrant, out-sized pussy-bow blouses trailing down gender-fluid deadstock tailoring.

Rambunctious satin bows added off-kilter fabulousness to Jeremy Scott’s final surrealist Moschino collection inspired by Salvador Dalí’s warped depictions of everyday items. “What if we talked about the classics melting?” Scott asked Vogue post-show, while touching on the

cyclical nature of fashion and the need for a sense of humour against the backdrop of a bleak news cycle. The bow – a millinery essential that evolved from mending tool to symbol of wealth thanks to the likes of Rococo style icon Marie Antoinette – transformed into an Eighties delight when pinned on Scott’s rebellious prom dresses.

Balmain played the ladylike card, with a collection that was an ode to the codes (think capes, corsets and crisp suiting) established by house founder Pierre Balmain in 1945, but which remain timeless today. Riffing off its Jolie Madame silhouette from 1953, Balmain’s modernday woman looked cinched and sassy, armed with voluminous pussybow blouses rendered in denim and loud bow-bedecked mini-dresses paired with pumps made pretty with yet more flouncy adornments.

Nostalgia was also at play at Nina Ricci, where young Londonbased upstart Harris Reed is now at the helm. His debut autumn/winter 2023 collection was a jolly romp through house tropes, including polka dots, feathers and big, glorious bows. Not for the shy and retiring are Reed’s new-look Nina Ricci ribbons exploding from platform heels and bandeau tops. With Harry Styles and Adele early fans of the brand’s joyous, inclusive makeover, expect a whole camp of fashion fans to dance through the season in exuberant, rather than pared-back, pieces. Who said the classics have to be predictable?

The Hennessey Venom F5 Roadster is a bespoke mid-engine carbon-fiber hypercar engineered to exceed 300 mph. Handcrafted in Texas, the two-seater boasts a custom 6.6-liter, twin-turbocharged ‘Fury’ V8 producing a phenomenal 1,817 horsepower and 1,192 lb-ft of torque — it is the most powerful Roadster in the world, delivering an unrivaled open-air driving experience. Exclusiveness is assured by production limited to just 30 personalized examples. ©

A curious fact that commonly crops up in stories about Carroll Shelby is that he once farmed chickens. Indeed, he later confessed that had he been more successful with poultry he might never have found fame as a legendary sports car driver and constructor.

Yet more surprising is that he lived to the grand old age of 89, given that he survived wartime service as a flight instructor and test pilot; a couple of serious racing accidents; 40 heart attacks and two major organ transplants. And his seven marriages are a whole other story.

Carroll Hall Shelby – whose life and work will be celebrated at this year’s Goodwood Revival – was born in January 1923, the son of a postmaster in the small rural community of Leesburg, Texas. Diagnosed with a “leaky” heart valve at the age of seven, when the family moved to Dallas, Shelby nevertheless shared his father’s automotive enthusiasm, riding his bicycle to local dirt-track races before learning to drive at 14. In 1941 he joined the US Army Air Corps, flying everything from a Beechcraft AT-11 Kansan to a Boeing B-29 Superfortress.

After the war, Shelby tried his hand at a variety of jobs, starting a trucking business and working on an oil rig before turning to chickens, but all the birds fell sick with avian botulism, and he was left bankrupt. At 29, Shelby was forced to resort to his “plan B”, indulging his love of cars.

After successfully racing a friend’s MG TC and a formidable Cadillac Allard J2X in a series of Sports Car Club of America races in 1953, Shelby caught the interest of Aston Martin team boss John Wyer. That opened up opportunities in Europe, including in Formula One. Shelby’s straight-talking approach sometimes ruffled feathers, as when telling Aston Martin Chairman David Brown that one of his cars handled like “ten pounds of shit in a five-pound bag”. Despite two serious accidents and months of surgery, Shelby raced on, twice being named Sports Illustrated magazine’s Driver of the Year. By 1959 that comment must have been forgiven as he drove Aston Martin’s DBR1 to victory in the Le Mans 24 Hours, all while suffering from dysentery and carrying a nitroglycerin pill under his tongue to stave off heart failure (something he neglected to mention to the team). The following year, after finding that he needed six pills to finish a race, he decided to retire.

So ended the first chapter of the Shelby legend, but there was more to come. James Mangold’s 2019 movie Le Mans ’66 only begins with that 1959 Le Mans victory, before telling the epic tale of Shelby’s development of the all-conquering Ford GT40 alongside his friend and collaborator Ken Miles. Drawing on his European experience, Shelby had already secured his reputation as a sports car builder with the Cobra, an unholy marriage of the British AC Ace roadster and an American Ford V8 engine, which first rumbled out of his newly established Los Angeles workshop in 1962. The more aerodynamic Daytona Coupe followed in 1964, winning at Sebring, Le Mans and Goodwood and subsequently beating Ferrari to the 1965 International GT Championship. Other cars given the Shelby treatment included the Sunbeam Tiger, the Ford Mustang, the Dodge Viper and the Oldsmobile-engined Shelby Series 1.

Shelby was modest about his own skills, attributing his success to an ability to pick a good team and an attentionspan deficit that made him constantly pursue new ideas, among them founding a children’s heart charity and even creating a best-selling chilli recipe. His was a life lived at full throttle, and with success at pursuing his passions that seemed to be won against all odds. As Shelby himself once put it, “I never made a damn dime until I started doing what I wanted.”

This year marks 100 years since the birth of racing driver and constructor Carroll Shelby, whose legend lives on in classic cars like the Shelby Cobra and Ford GT40

Words by Peter Hall

A long-running series of playful prints by Mychael Barratt imagines the canine companions of the world’s greatest artists

Words by James Collard

Words by James Collard

It all began with a visit to a Marc Chagall exhibition – after which the artist, printmaker and cartographer Mychael Barratt found himself daydreaming about what kind of pet dog Chagall might have owned. He then painted his playful but beautifully Chagall-like work, Chagall’s Dog in Love, set appropriately in some wild-looking Russian night under a yellow crescent moon. And so began a project – almost by accident – that has lasted more than two decades and produced 50-plus works, from Rothko’s Dog (suitably block-like) to Hockney’s Dog (diving into a Californian pool) and Damien Hirst’s Dog (spotty, of course).

“I was walking to the Tube from my studio,” Barratt recalls of that fateful moment in 2002, “and I just started thinking randomly about what kind of dog Chagall would have had, if he’d had a dog. And that kind of spawned the first one of these. I literally just did the one. And people, although they liked it, were a little slow to get it. And so I thought, ‘Well, maybe I should do another one, just to give it context.’ So I did a second one.” (Van Gogh’s Dog.) And then another, and so on. But while the series was a theme Barratt has always returned to, there has always been other work going on in parallel: as an artist in residence at the Globe Theatre throughout Mark Rylance’s tenure there, for example, as well as creating maps that have gone into the British Library’s permanent collection and the private collection of Elizabeth II.

Barratt is, in short, a serious, working artist, who attended art school in his native Canada before moving to London and studying printmaking at Central Saint Martins. And his artists’ dogs series combines whimsy and wit with serious printmaking skills – including techniques that Barratt mastered the better to channel a particular artist’s oeuvre – silk screening for Bridget Riley, for example, and woodblock printing for Matisse. But has anyone suggested, I wonder, that he’s not serious about his work – or that he’s taking the mickey out of these great artists?

“You run that risk,” he answers, “any time you allow humour to creep into your work. But you know, I take the work seriously.” He has only featured artists whose work he respects, and insists, “I’ve certainly not had any bad responses from people who have been the subject of them.” Barratt loves art and he loves dogs, so what’s not to love about his artists’ dog series? His own dog (“she’s a very good model”) is a miniature longhaired dachshund who appears in Leonardo da Vinci’s Dog Barratt’s next project isn’t about dogs at all, but about his adopted city, where he divides his time between his home in Highgate and his studio in Bermondsey. “It’s a little love song to London, really. There’s going to be a Tube map in it and lots of idiosyncratic ways of paying homage to London…” And along with these, some works, for sure, which “are kind of dog and London”.

Prints by Mychael Barratt will be on sale at the Affordable Art Fair, Battersea from 19-22 October 2023, affordableartfair.com. His exhibition of new work, Once Upon a Time in London, will run from 12 October-19 November 2023 at Eames Fine Art Gallery, eamesfineart.com

Drawing on a rich tradition of fine porcelain adorned with flora and fauna, tableware designers are once again taking a walk on the wild side

Words by Dominic LutyensOn one plate, a fox’s face craftily eyes the person eating from it. “Don’t let this sly fox steal your food!” quips Donna Wilson, creator of the simple vulpine sketch. Drawn with equal economy are the avocet and swallow motifs dreamt up by Catriona Hall for Dog & Dome’s plates.

As modern as they seem, such designs belong to a longestablished tradition of natural-history motifs on ceramic tableware. In the 17th and 18th centuries, porcelain plates in China and Japan often bore images of birds. Chinoiserie – a Western emulation of Chinese art and design that originated in the 17th century – spawned an abundance of tableware with bird motifs. In 1765, for example, the 3rd Duke of Richmond ordered a dinner service from the French royal factory of Sèvres adorned with vibrantly plumed birds copied from prints found in Goodwood’s library – specifically, a book that had belonged to the 2nd Duke. This was the first time Sèvres, which was founded in 1756, had ever been commissioned to depict a creature on its porcelain.

In times past, animal motifs on porcelain formed part of elaborate landscapes but today they are frequently the main or sole motif. Exceptions include Fromental’s Paradis tableware, co-created with Limoges porcelain brand Raynaud, which depicts birds and butterflies flitting against a white or sugared-almond blue background.

“Treated in a fresh, unstuffy way, Chinoiserie appeals to a

From top: Nathalie Lete Titania plate for Anthropologie; Sèvres wine cooler from the Goodwood dinner service (1765)

younger audience,” says Lizzie Deshayes, who co-designed the collection. “Paradis calls for an escape into an exotic vision of nature.” Designer Klaus Haapaniemi, a pioneer of the contemporary animal motif trend, also offers enticing glimpses of nature via his Taika tableware for Iittala, which features stylised images of Finland’s forest creatures. Midcentury design, which favoured stylised natural forms, is a major influence on the trend. Wilson says her pareddown animal motifs fit with her “Scandi aesthetic” and her admiration for Swedish designer Stig Lindberg’s natureinspired ceramics. Catriona Hall, meanwhile, says of her work: “I was drawn to the avocet because it is so stylised and inordinately elegant with its over-long legs and beak.”

Another possible impetus for this phenomenon is the isolation of pandemic lockdowns, which resulted in a desire to reconnect with nature, according to London-based Cally Lathey, who designed the Flora and Fauna tableware collection for her brand House of Cally. “It’s inspired by the pelicans of St James’s Park and the peacocks of Holland Park,” she says. “Exotic animal motifs create a sense of curiosity and yearning for adventure.”

Bertrando Di Renzo of Les-Ottomans has created La Ménagerie Ottomane – tableware emblazoned with giraffes, cheetahs and monkeys. “It satisfies a demand for maximalist tableware,” he reasons. He adds that fashion labels such as Gucci and Hermès are also fuelling the trend.

More profoundly, perhaps, the trend reflects our escalating concerns about biodiversity and the environment.

“Its popularity with younger consumers,” says Hall, “is possibly down to the urgent appeal for conservation of creatures being lost due to climate change.” If she’s right, animal-motif ceramics will continue to proliferate –assuming, of course, that they are sustainably produced.

As a lavish new tome from luxury art book publisher Taschen confirms, vintage motorcycles have never been more desirable – and they’re attracting record-breaking prices at auction

Words by Simon de Burton

Words by Simon de Burton

Old motorcycles were once regarded as poor relations to collector cars. But in recent years the wonder of two wheels has come to be discovered by people with serious money to spend, transporting the status of classic bikes from the tradesman’s entrance right around to the front door. Earlier in 2023, a 1908 Harley-Davidson “Strap Tank” came close to breaching the seven-figure mark when it fetched a record-breaking $935,000, making it the most expensive motorcycle ever sold at auction. And British pensioner Derek Prior was left open-mouthed in April when the Brough Superior he bought for £150 in 1973 sold at auction in Staffordshire for more than £280,000. Another buyer, meanwhile, was told they had acquired “the classic bike bargain of the century” when they snapped up a 1974 Ducati 750 Super Sport “green frame” in the US for $201,600; the last comparable example on the market fetched half a million.

There are many reasons why bikes have finally been “discovered” by serious collectors, not least the fact that, compared with an $18m Ferrari, a $200,000 Ducati seems inexpensive. Then there is the ease of storage and display (one car takes the space of five bikes) and the fact that they are usually a whole lot less troublesome and expensive than four-wheelers to keep in good working order.

But, apart from being fun to ride, polish, maintain and look at, what collectors and enthusiasts really appreciate about classic bikes is their aesthetic qualities. From the raw beauty of a Vincent v-twin engine to the sculpted fuel tank of an MV Agusta, and from the three stacked exhaust pipes of a Triumph Hurricane to the stretched-out profile of a Moto Guzzi Le Mans, old motorcycles can truly be viewed as rolling works of art.

It’s for that reason that one of the latest titles from specialist book publisher Taschen is called Ultimate Collector Motorcycles Comprising two hefty volumes in a stout slipcase, the books trace the history of motorcycle evolution from the late 19th century to the 2020s in a series of lavishly illustrated descriptions of more than 100 machines. Starting with ancient “pioneer” bikes such as the Hildebrand & Wolfmüller of 1894 (considered the first “true” motorcycle), the book ends, more than 900 large-format pages later, with the Aston Martin AMB 001, the revered carmaker’s first – and pretty impressive – attempt at a two-wheeler.

Offering an eclectic mix of road and race machines, the books call on luminaries from the motorcycle world to explain their significance in a series of in-depth interviews. One such person is Ben Walker, the international director of motorcycles for auction house Bonhams, who sums up what makes owning and riding motorcycles so powerfully addictive. “Once you’ve ridden one,” he says, “you won’t want to travel by any other means. It’s instant freedom.” And that’s all you need to know.

Ultimate Collector Motorcycles is out now, published by Taschen. Goodwood Revival 2023 will open with a parade of 200 vintage motorbikes, 8-10 September 2023.

Led by the Duchess of Richmond, Goodwood is hosting its first-ever Health Summit, bringing together leading thinkers, policymakers and retailers to discuss how our diet impacts our health. Here, the Duchess tells Catherine Peel why she is so passionate about changing the nation’s eating habits

Health and wellbeing have long been key tenets of life at Goodwood. The Estate’s farm was the first in the country to become organic and remains the largest low-lying organic farm in all of Europe. The late Susan, Duchess of Richmond (the current Duke’s mother) was an early member of the Soil Association and shared with her daughter-in-law Janet, Duchess of Richmond, a belief in the importance of soil health. “I was thrilled when I arrived at Goodwood to discover I had an ally in pushing the organic farming agenda,” the Duchess recalls. “It is very much at the heart of our holistic philosophy, providing organic produce for all our restaurants, with a focus on healthy eating as an option on all our menus.”

The Duchess’s passion for food and health began at an early age: “My father’s mother, Nancy Astor, who died when I was only three, was a Christian Science convert in the 1920s and it transformed her health. When I was growing up there were all sorts of books about health on the shelves and I was fascinated by them all. Gayelord Hauser [an American naturopath] wrote a book called Look Younger, Live Longer and it was ground-breaking at the time. During the 1930s, which was just when antibiotics were starting to be used, people were thinking about how they could stop themselves becoming ill – at a time when illness was potentially much more life-threatening than it is now.”

The Duchess grew up in the 1970s, when the hugely popular sitcom The Good Life popularised the idea of selfsufficiency and there was a resurgence of interest in “growing

your own”. It was also when interest in organic agriculture took off, in contrast to the harsh nature of post-war intensive farming. The Duchess’s mother had her own organic kitchen garden and her uncle, David Astor, founded the Organic Research Centre in 1974. “This was the world I inhabited,” she says, “and the start of my interest in the whole thing.

“As I grew older, I became much more interested in the mind-body connection. Research carried out over the past few years has proved that gut health does actually affect how we feel. The gut is known as the second brain, and it’s a conversation – so almost any ache or pain, while it may be a genuine illness, is also telling us something about who we are, what we believe, what our emotional burdens are.”

The Duchess concurs that current thinking has moved on from the focus being simply on organic farming to a more fundamental belief in the importance of “soil health” and regenerative farming – using agricultural practices that constantly replenish the soil. “You can grow something organically but if the soil isn’t good quality or it hasn’t been well husbanded, the vegetables will still be less nutritious,” she explains. “By the 1990s, many vegetables had a decline in mineral levels of between 30 and 50 per cent. So although organic farming is important, ultimately it is shorthand for taking care of the soil, taking care of the animals, and not using chemicals everywhere. The idea is to give both the soil and the animals the best possible health, and this in turn serves human health.”

Ferrari Approved: certification to keep your passion unchanged through the years. The Ferrari Approved pre-owned certification programme guarantees the utmost confidence for those who buy a Ferrari first registered no more than 14 years ago.

It includes no less than 201 checks and warranty up to 24 months from the Maranellobased company itself.

Exeter

Carrs Ferrari

Tel. 01392 822 080

exeter.ferraridealers.com

Solihull

Graypaul Birmingham

Tel. 0121 701 2458

birmingham.ferraridealers.com

Nottingham

Graypaul Nottingham

Tel. 0115 837 7508

nottingham.ferraridealers.com

Leeds

JCT600 Leeds

Tel. 0113 824 3200

leeds.ferraridealers.com

Lyndhurst

Meridien Modena

Tel. 02380 283 404

lyndhurst.ferraridealers.com

Belfast

Charles Hurst

Tel. 0844 558 6663 belfast.ferraridealers.com

Edinburgh

Graypaul Edinburgh

Tel. 0131 629 9146

edinburgh.ferraridealers.com

Hatfield

H.R. Owen

Tel. 01707 524 093 london-hrowen.ferraridealers.com

Colchester

Jardine Colchester

Tel. 01206 848 558 colchester.ferraridealers.com

Manchester Stratstone Manchester

Tel. 01625 445 544 manchester.ferraridealers.com

Swindon

Dick Lovett Swindon

Tel. 01793 615 000

swindon.ferraridealers.com

Glasgow

Graypaul Glasgow

Tel. 0141 886 8860

glasgow.ferraridealers.com

London

H.R. Owen

Tel. 0207 341 6300

london-hrowen.ferraridealers.com

Egham

Maranello Sales

Tel. 01784 558 423

london-maranello.ferraridealers.com

The Gut Health Programme first opened at Goodwood in May 2021. During the pandemic, Grayshott Spa in Surrey was sadly forced to close, and Stephanie Moore and Elaine Williams, who had been operating there, moved to Goodwood with some of their gut health team. Janet, Duchess of Richmond had experienced the programme on many occasions and was thrilled to be able to bring it to Goodwood, having been convinced first-hand of its benefits.

She says: “In five days, you get so much information that it can provide you with the basis for a healthy life for a very long time. Obviously, most of us don’t take in everything we’re told and so coming back for a reboot, maybe once a year, is what a lot of people tend to do, myself included. We have also launched an Executive Programme, which is for people who might be going through a career change and want to reboot their health and their life direction, and this has been incredibly successful.”

As the Duchess emphasises, mental fitness is key, and part of the Executive Programme involves two 90-minute, one-onone sessions with Julie Stokes (an esteemed executive coach), two sessions with Kate Fismer, a resilience coach, as well as group health talks. “We’ve also launched a three-day menopause retreat and a two-day Wim Hof programme. Next February, we plan to trial a new programme, MYHY –Maximising Your Healthy Years. The talks will be focused on how we can work towards increasing our health span.”

The Duchess believes the steady flow of recent studies about the microbiome means we can no longer ignore the importance of the gut and therefore of the food we eat: “It’s high time this became really mainstream as opposed to a minority interest. The idea for the Health Summit is a natural evolution from our gut-health programme – and Goodwood, having long been a convenor for great minds and influencers, will provide a platform. All the speakers will have the latest research at their fingertips and in the room will be influential policymakers and decision-makers from the food world.” Goodwood is delighted that the event will be sponsored by Randox, the highly regarded global healthcare and diagnostics company.

The summit itself will broadly involve two “conversations” compered by the BBC Today programme presenter Justin Webb. The first will be led by Professor Ed Bullmore, focusing on gut health and mental health. The second conversation will be led by Jessie Inchauspé (aka the Glucose Goddess, interviewed on p39) and Dr Chris Van Tulleken, discussing the impact of glucose spikes on the body and how gut health affects our overall physical health. Stephanie Moore, Goodwood’s own nutritionist, will also join the panel for the afternoon session.

The Duchess hopes that the summit will not simply be a talking shop but will result in real-world action. “So, for example, we want to formulate a list of relatively easy wins – 10

things we can do to create change – and that’s why it’s important that representatives from supermarkets and food production are there, as well as health care and education, so that there can be discussion on how to effect change on a large scale. On the back of new evidence, policymakers can work towards better guidelines that reflect the latest science.”

This is of course an ambitious aim, but she passionately believes that we have to start somewhere. “With health, the ball is usually thrown back to the consumer, telling people that they have to make healthier choices. But it’s approximately 50 per cent more expensive to eat a really gut-friendly diet – and that’s a major problem, particularly at the moment, with the cost of living so high, when people can’t necessarily afford to eat even averagely well. So we need to think about what is available in their locality, the quality of food they have access to. The government has to make it more attractive for food producers and markets to sell healthier food, and we can do that by penalising the purveyors of unhealthy food, and by supporting local initiatives. This may sound a little bit ‘nanny state’, but the government was happy to lay down the law during the Covid pandemic, and given that we know one of the biggest problems with Covid was that we weren’t very healthy to start with, this should be a natural follow-on. You need a healthy microbiome in order to deal with Covid! And any other health challenges that might come our way, of course.”

The Duchess is adamant that now is the time to act. With so much new research available about gut health and the microbiome, and about the impact of unstable glucose control and inflammation in the body, we are at a tipping point in our knowledge, which gives us the tools to act: “We mustn’t give up hope – there’s still time. I would love this summit to happen every year; it’s certainly not designed to be a one-off and it should have its own energy and aims to be accountable for. There will be 100 significant influencers in the room and we’ll live-stream up to 5,000 tickets. I hope that through this debate we can support change for better health across the nation.”

Tickets for the Goodwood Health Summit this September are available from goodwood.com. Overleaf: Meet one of the panellists, Glucose Goddess Jessie Inchauspé

“All the speakers will have the latest research at their fingertips and in the room will be policymakers, as well as decision-makers from the food world”

STEPHEN HAYWARD

Biochemist-turned-bestselling-author Jessie Inchauspé has used her struggles with anxiety and depression as the catalyst to investigate how our diet affects our mental and physical health. Her discoveries, which she discusses here with Anna Maxted, are changing lives – and now she is coming to the Goodwood Health Summit to spread the word

Many of us experience glucose spikes and dips: after we’ve eaten carbs or sweet snacks, our blood sugar shoots up and then plummets. Telltale signs that we’re stuck on a glucose rollercoaster include cravings, chronic fatigue, poor sleep, inflammation, low mood and brain fog. French-born Jessie Inchauspé was no exception. Following an accident a decade ago, she struggled with anxiety and depression, and decided to study biochemistry at King’s College London, partly driven by a desire to understand her own body’s responses. After graduating, she went to work for a biotech company and was asked to take part in a trial that required her to wear a continuous blood-sugar monitor. This was Inchauspé’s Eureka moment, as she began to tune in to the link between her blood-sugar spikes and her poor mental state.

It led Inchauspé, 30, to transform her eating habits and health. She started to post on social media about what she was discovering and gradually built a fanbase. Last year, her first book, Glucose Revolution: The life-changing power of balancing your blood sugar, was a Number One international bestseller. Now she has simplified her approach in The Glucose Goddess Method after a number of her 2.5 million Instagram fans sweetly asked her to move in to teach them first-hand her sugar spike-squashing strategies. “I thought, ‘What’s the most comprehensive, easy, encouraging plan I could create?’ And that’s how the four-week Method was invented,” she explains.

It is indeed a beautifully straightforward and user-friendly guide to adopting “the most important hacks to keep your glucose levels steady and feel amazing”, she says. “Every week for four weeks, we add a new one of these scientifically backed principles into our lives.”

So, week one, you eat a savoury breakfast (built around protein, containing fat, fibre when possible, and nothing sweet except a little fresh fruit if desired, and minimal starch, if required for taste, eg, one slice of bread.) This steadies blood sugar, reduces cravings, and should keep you full for four hours. Week two, you also drink one tablespoon of vinegar daily – ideally, 10 minutes before eating something sweet or starchy. The acetic acid therein can reduce the subsequent glucose spike by up to 30 per cent, and the insulin spike by up to 20 per cent. (Inchauspé’s suggestions include adding it to soda water, ginger, and lime.) Week three, you consume a

vegetable starter before lunch or dinner (comprising 30 per cent of the meal). Its fibre lines the gut, slowing glucose absorption, decreasing the spike by as much as 75 per cent. In week four, you move after eating, for 10 minutes. Even if you just tidy up, using your muscles flattens the glucose curve.

It’s all eminently doable, and quietly transformative. Which is a relief, because we’re struggling. “The over-reliance on processed foods has hurt our health immensely,” she says. “We’re eating a lot of sugar, a lot of processed starch, a lot of industrial oils; we’re eating very little fibre, unhealthy sources of fat, and not much good quality protein. Generally, our bodies are responding with all these diseases.”

Three out of five people will die of an inflammation-based disease. “It’s truly an epidemic. The more glucose spikes, the more inflammation increases in the body. This can show as acne, eczema, psoriasis, but our organs also become more inflamed. Type 2 diabetes, heart disease, cancer, are all inflammatory-based diseases.” Steadying our glucose levels reduces inflammation.

Conversely, “High glucose levels, even in midlife, are a very important predictor of whether you’re going to get Alzheimer’s in the future.” So much so that “some scientists are calling Alzheimer’s Type 3 diabetes”.

As Inchauspé herself found, diet is a key ingredient in mental health, too. It’s notable that anxiety and depression are rife, especially among young people. Studies show they can be exacerbated the more glucose spikes you have, she says. “Glucose spikes can also increase brain fog, lack of concentration; they can make you have cravings, poor sleep. The brain, food and glucose are very closely connected.”

As the popularity of the Goodwood Gut Health Programme reflects, we’re increasingly aware that nurturing our gut microbiome is imperative. Alas, says Inchauspé, when we eat in a way that creates lots of glucose spikes, we feed the bad bacteria, and reduce the good. Happily, “By switching to a diet that promotes more vegetables, healthier sources of proteins and fats, and less sugar, like the Method helps you to do, the good bugs in your gut proliferate and are happy – and this has a very important effect not only on your metabolism but also on your mental health and mood,” she says.

Inchauspé believes “Big Food” can be part of the solution, but as “supermarkets and manufacturers are profit-driven”, she suspects they will only respond to a groundswell of pressure from consumers demanding healthier produce. It is exactly this kind of thinking that lies behind the Duchess of Richmond’s Goodwood Health Summit initiative: to bring experts such as Inchauspé and her fellow panellists (see right) into the same room as policymakers and supermarket bosses with the goal of effecting fundamental change.

Meet three of the expert guests who will be shaping the panel conversations at the inaugural Goodwood Wellness Summit

Goodwood’s clinical nutritionist, Moore questions many of our accepted “rules” about how to be healthy. She says her success as a natural health therapist “lies in the fact that I address each of the emotional, psychological, physical and nutritional aspects of my clients’ lives.”

A doctor who specialises in infectious diseases, Van Tulleken is also one of the BBC’s leading science and wellness communicators for both adults and children, often collaborating with his twin brother Xand, a fellow doctor. His newest book, Ultra-Processed People, considers issues such as how “food is engineered to drive excess consumption”.

A leading British neuropsychiatrist and neuroscientist, Bullmore is head of the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Cambridge. He believes that “we live in a falsely divided world, which draws too hard a line – or makes a false distinction – between physical and mental health”.

Meanwhile, Inchauspé is delighted (but not surprised) at the book’s runaway success. Most of us know we should eat better, but are confused about how to do it. “I think people are responding to the clear, easy, actionable, non-restrictive hacks in this method.”

It’s just the beginning. She hopes that every reader “will share the science with their friends and family”. And Inchauspé will keep posting free educational content on Instagram. Her aim? “To get this to a point where I become useless and irrelevant because the hacks are so well-known and integrated into culture.” That’s her ultimate objective, she smiles: “To become totally redundant!”

“The over-reliance on processed foods has hurt our health immensely… our bodies are responding with all these diseases”

The Ultimate Electrified M Power

SIMON MOTTRAM co-founder, Rapha cyclewear VINTAGE INSPIRATION: 1950s to 1960s cycling jerseys

British cycling brand Rapha was born out of a dissatisfaction with the apparel on offer around the turn of the century. “There was actually very little, and what there was, was pretty horrible,” remembers the brand’s co-founder and former CEO, Simon Mottram. “When I’m out on my bike, I don’t want to look like Chris Froome in a skin suit – that just isn’t aspirational to me.”

Around that time, Mottram was given a book, An Intimate Portrait of the Tour de France: Masters and Slaves of the Road, for his birthday. Published by the French cycling journalist Philippe Brunel, it provided the Londoner with a timely window into the glory years of road racing – the 1950s and ’60s into the ’70s – when cycling was arguably the most popular sport in Europe.

“The book is full of amazing full-plate, black-and-white photographs of people like Raymond Poulidor, Jacques Anquetil, Eddy Merckx and Charly Gaul – these sort of mythical cycling heroes,” says Mottram. “And they just looked incredible. They’ve got great sunglasses, they’re wearing caps not helmets – and they were hardly ever on their bikes. They’d be reading the paper, smoking cigarettes or eating dinner, and that was such an inspiration: these guys who suffer like crazy but look like film stars. That was the aesthetic I was going for.”

The book – which Rapha has since republished in English under the title Kings of Pain – also provided inspiration for the brand’s name. “For a long time, I was playing around with two names,” Mottram recalls. “One was Motta, after Gianni Motta, who won the Giro d’Italia in ’66 and always looks super-cool.” The other name in the frame was Rapha, after the star-studded Saint-Raphaël team, which actually abbreviated its name to Rapha for a few seasons.

“For me, the jerseys worn by the Saint-Raphaël/Rapha team – Roger Rivière, Tom Simpson and Britain’s first Tour de France stage winner, Brian Robinson – were just brilliant,” says Mottram. “Simple graphics, wonderful colours and, more importantly, they weren’t skintight. This one [pictured] is a beautiful, if slightly moth-eaten example from 1963. It’s significant because at the time, non-cycling brands were banned from sponsoring racing teams, so they [Saint-Raphaël, a liquor brand] made out like Rapha was short for Raphaël Géminiani, the team’s founder, an incredible cyclist in his own right. They never sold these jerseys so it definitely belonged to one of the team, if not Géminiani himself – so I’d imagine it could be worth anything between £7,000 and £10,000.”

Ultimately Mottram preferred how the word Rapha sounded, compared to Motta: “It’s kind of European, easy to pronounce, pretty cool. It sounds like a no-brainer now, but at the time it was a pretty close race.”

Shop for Rapha designs at rapha.cc

From a 1960s cycling jersey to a Chanel little black dress, contemporary creators share the vintage pieces that first inspired them to make new workWORDS: ALEX MOORE. PHOTO: JONATHAN JAMES WILSON

JUSTINE PICARDIE writer and editor

JUSTINE PICARDIE writer and editor

Justine Picardie can trace her love of Chanel to childhood, an interest that ultimately led her to write an acclaimed biography of the woman many still regard as the most iconic fashion designer the world has seen. “My mother got married in a Chanel little black dress,” Picardie explains. “It was 1960, London, so it wasn’t a couture Chanel dress, but it was cut line for line from a Chanel pattern. As a child I loved that dress, although I didn’t know anything about Gabrielle [who became widely known by the nickname Coco] Chanel, the woman. My mother was very rebellious, so for her to get married, in a registry office in Hampstead, in a little black dress rather than a white wedding dress – having only known my father for a few weeks – was an expression of her unconventional approach. As a teenager I would wear the dress to punk concerts, so I think it embodied a sense of radicalism for me. There’s a famous Chanel saying: ‘Elegance is refusal.’ My mother refused to get married in white.” (Sadly the dress was lost, although when Picardie published My Mother’s Wedding Dress in 2008, a collection of essays about our relationship with clothes, The Times Magazine recreated it for her using an old photograph as reference, shown right.)

Picardie became a journalist, initially as an investigative reporter for The Sunday Times, later as editor-in chief of Harper’s Bazaar. “Back then, if you were going to be taken seriously you were expected to write about ‘serious’ things: politics, crime. But I began to realise that what we wear can be a fascinating prism through which to look at the world. That interest definitely goes back to my mother, the power of clothes, their stories, their histories.” In the late 1990s, she went to interview Karl Lagerfeld for The Telegraph Magazine. “He spoke to me very openly. As part of the research for the piece I was allowed to go to Gabrielle Chanel’s private apartment in Rue Cambon. It was one of the most atmospheric places I’ve ever visited. Nothing had been moved or changed since her death in 1971, so it was still relatively recent history. All her precious objects were there – her tarot cards; quartz fortune-telling orbs; gold boxes given to her by her lover, the Duke of Westminster; books given to her by her first lover, [the polo player] Boy Capel – all these very talismanic things.”

It was at this point that the idea of writing the first English language biography of Chanel began to percolate: “The apartment was, for me, the starting point – feeling the sense that she might just have left the room, that if you looked in the mirror you might just have missed seeing her reflection.” So

“My mother was very rebellious, so for her to get married in a little black dress rather than a white wedding dress – having only known my father for a few weeks – was an expression of her unconventional approach”WORDS: GILL MORGAN. PHOTO, RIGHT: COLIN BELL/CORBIS VIA GETTY IMAGES

began Picardie’s deep dive into the Chanel archives and into the many layers of her subject’s life and world.

She knew she needed to unearth a lot of new information: “I got to know Chanel’s nephew’s daughter Gabrielle, who was then in her eighties. She may actually have been her granddaughter, as her nephew may have been her son, we will never know. I stayed with her, and she showed me Chanel’s own clothes in a wardrobe and invited me to try on a jacket and a coat. She said you won’t really understand her until you try on these pieces. It was one of the most powerful experiences I’ve ever had as a writer. To put on not only Chanel original couture pieces but clothes that had been designed and made by her seamstresses for her, it was the most extraordinary feeling,” recalls Picardie. She slipped on a jacket in cream tweed, lined with black grosgrain ribbon. “I put my hands in the pocket, and there were gloves and a handkerchief, and you could still smell the scent of Chanel perfume. Never have I seen such exquisite clothes.”

For Picardie, Gabrielle Chanel is much more than “just” a fashion designer. “She was a genius; her importance goes way beyond fashion. Her work was a sartorial expression of modernism. There’s a reason she was friends with Stravinsky, Cocteau, Picasso. So many things she designed have become iconic, part of our style lexicon – the clothes of course, but also the perfume, the red lipstick.” But her life story is also compellingly modern: “She was born in the 19th century, impoverished, illegitimate. Her mother died when she was 11, her father abandoned her and her two sisters, and they went into an orphanage. Yet she created herself as an independent woman who became synonymous with female empowerment in the aftermath of the First World War. She gave women, for the first time, sartorial dignity, which had been the preserve of men, by adapting men’s tailoring, taking away corsets, introducing trousers, stripy Breton tops, and including elements of a gentleman’s sporting wardrobe, such as tweeds and jerseys that a cricketer or polo player might have worn. They are chic but also comfortable. These are clothes that women can go to work in, drive a car in, ride a bicycle in. That sense of sartorial ease and liberation is so powerful.”

Picardie has just completed a revised edition of her Chanel biography, to coincide with a major V&A exhibition on the designer’s life and work. The book contains new research and imagery, some of it relating to Chanel’s controversial decisions during World War II. “Having written a book on Catherine Dior, who was a member of the French Resistance, I now know a lot more about the history of that period in wartime France. The accusations of collaboration are powerful and need to be examined, but the truth is more complex than is often reported, as is so often the case when one investigates the occupation. Ultimately, she was a genius, but a flawed genius.”

Chanel clothes continue to have a place in Picardie’s wardrobe today. “I have a little black dress that I wear. And when I married my husband Philip, I wore a Chanel wedding dress [pictured, far left] that was based on an early-1930s ivory silk wedding dress, and I’ll treasure it forever.” But perhaps it is in day-to-day life that her icon’s sartorial spirit is most present: “It’s not as if I’m always wearing head-to-toe Chanel,” jokes Picardie. “My stripy top might be from Uniqlo and my jeans Levi’s, but I’ll mix them with a Chanel jacket. It’s always been part of how I’ve dressed – I just feel very at ease like that.”

Justine Picardie will give a talk on Chanel at Goodwood Revival. Tickets are available at goodwood.com. The new edition of Coco Chanel: The Legend and The Life is published by Harper Collins.

Glenn Spiro’s connection with Cartier began at an early age. The acclaimed British jeweller became an apprentice aged just 15 at English Artworks, a maker that supplied pieces to the luxury jewellery house founded in 1847 by Louis-François Cartier. Leaving after eight years, during which he became a master jeweller, London-born Spiro would go on to undertake commissions to create high-jewellery pieces for Cartier. After a stint at Christie’s, he founded his own jewellery house in 2014. Today he makes exceptional, one-off pieces – showcased in his elegant Art Deco atelier on Bruton Street alongside cherished pieces from his collection of vintage Cartier.

“Mainly objets d’art,” is how Spiro describes his collection, of which there are “perhaps 40 or 50, maybe more, I’ve never counted.” These range from the gouaches that are part of the traditional design process for high jewellery, which grace the walls of the atelier, to this particular favourite (pictured, left): a replica in silver and silver gilt of the Model A Ford, precursor to the Model T, made for a member of the Ford family.

“I collect special things,” he explains. “I’d just bought a wonderful stone from the [Ford] family – and when I visited them I saw this piece and they told me its story [it was created by Cartier in 1983 to commemorate the Model T’s 75th anniversary] and I said that if it was ever available to buy, I’d be interested. A year or so later, they got in touch.”

For Spiro, it represents a craftsmanship that he fears “is dying, because the demand for it is dying”, though a glimpse of the Butterfly ring Spiro created for Beyoncé, now in the permanent collection of the V&A, suggests that he is doing his best to keep it alive. For Spiro, what Cartier represents is a kind of fearlessness “to explore and create in all areas of craftsmanship… they set the standard of excellence”. Discover Glenn Spiro jewellery at glennspiro.com

“I said if it was ever available to buy, I’d be interested. A year or so later, they got in touch”WORDS: JAMES COLLARD. PHOTO, LEFT: GABBY LAURENT

Fuel consumption and emission values of Urus Performante: Fuel consumption combined 14,1 l/100km (WLTP); CO2-emissions combined 320 g/km (WLTP).

Lamborghini Birmingham

2 Wingfoot Way, Fort Dunlop, Birmingham, B24 9HF

Phone +44 (0) 121 306 4007

Lamborghini Bristol The Laurels, Cribb’s Causeway Centre, Bristol BS10 7TT

Phone +44 (0) 117 203 3960

Lamborghini Chelmsford Eastern Approach, Chelmsford, Essex CM2 6PN

Phone: +44 (0) 124 584 7700

Lamborghini Edinburgh Kinnaird Park, Edinburgh, EH15 3HR

Phone +44 (0) 131 475 2100

Lamborghini Hatfield Hatfield Business Park, Mosquito Way, Hatfield AL10 9WN

Phone +44 (0) 170 7524 105

Lamborghini Leeds 2 Aire Valley Drive, Temple Green, Leeds LS9 0AA

Phone +44 (0) 113 487 3040

Lamborghini Leicester Watermead Business Park, Syston, Leicester, LE7 1PF

Phone +44 (0) 116 490 6626

Lamborghini London 27 Old Brompton Road, London SW7 3TD

Phone +44 207 589 1472

Lamborghini Manchester St Mary’s Way, Stockport, Manchester, SK1 4AQ

Phone +44 (0) 161 474 6730

Lamborghini Pangbourne Station Road, Pangbourne, RG8 7AN

Phone +44 (0) 118 402 8060

Lamborghini Tunbridge Wells Dowding Way, Royal Tunbridge Wells, Kent, TN2 3DS

Phone +44 (0) 189 225 0605

VINTAGE INSPIRATION: 1930s to 1950s dresses

“In the 1930s and ’40s, many women used to make their own dresses, and the result was that they were tailored to fit a woman’s body in a flattering way,” says Pearl Lowe (pictured, left). Since 2006, she has created an eponymous vintageinspired clothing line, as well as collecting and selling original vintage pieces, with a similar business model for homeware.

Depending on your age and tastes, you may also know Lowe as the former frontwoman of a 1990s indie band, Powder, or as the mother of supermodel Daisy Lowe (in her 2008 memoir, All That Glitters, Lowe detailed candidly the highs and lows of her former life as part of the so-called “Primrose Hill set”).