SARAH YANG

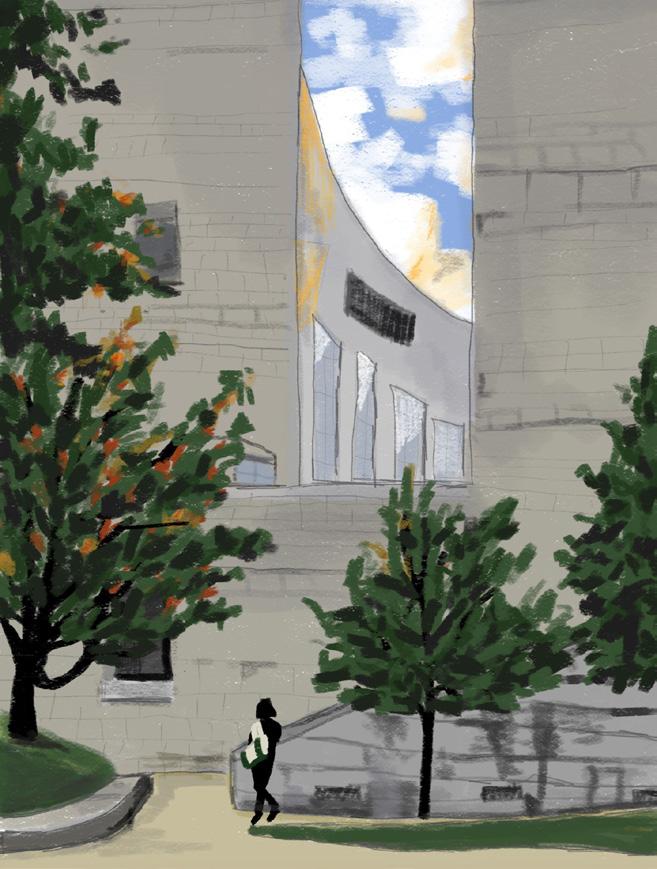

Class of 2026, She/Her September at the Larner College of Medicine

so much depends upon a red wheel barrow glazed with rain water beside the white chickens

“THE

William Carlos Williams, M.D.

Published in Spring and All (1923)

The Red Wheelbarrow is the student-run magazine for the literary and visual arts at The Robert Larner, M.D. College of Medicine at the University of Vermont. Named after physician-writer William Carlos Williams’ poem, “The Red Wheelbarrow,” our publication aims to capture, cultivate, and explore the creative endeavors of the medical and scientific communities— past and present—here at UVM and its clinical education partners.

The Red Wheelbarrow encourages submissions related to the medical humanities—an interdisciplinary field that strives to contextualize and interpret topics including, but not limited to, the medical profession and education, and human health and disease; however, our publication remains inclusive of all ideas and artistic pursuits outside the scope of the medical humanities.

The Red Wheelbarrow is published annually, and welcomes submissions from all members of the Larner College of Medicine, UVM graduate health sciences and biomedical programs, and our clinical affiliates.

EDITORS

Isabel Thomas, Class of 2027, She/Her

Jonathan Chen, Class of 2027, He/Him

Ryan Marawala, Class of 2027, He/Him

Sarah Yang, Class of 2026, She/Her

FACULTY ADVISOR

Sakshi Jasra, M.D., She/Her

Professionalism, Communication, and Reflection (PCR) Course Director

Assistant Professor of Medicine, UVM Larner College of Medicine

PRODUCTION

Office of Medical Communications, UVM Larner College of Medicine

CONTACT redwheelbarrowuvm@gmail.com

There is a common saying that medicine is as much an art as it is a science. It is no wonder that medicine, characterized by improvisation, creativity, and innovation, attracts people who also find deep fulfillment in the arts and humanities.

Engaging in creative pursuits can provide an escape from the stressors of daily life. One can express lifelong dreams, share imaginative stories, and process emotions that are difficult to convey through everyday conversation. Likewise, in observing the art of others we can find comfort, inspiration, and a new or even forgotten perspective. While medicine is important for our health, art is crucial for our spirit.

The Red Wheelbarrow is the Larner College of Medicine’s student-run art and literary magazine. It was founded three decades ago by LCOM medical students so that the creative endeavors of our medical and scientific communities can be celebrated.

This year, as we transitioned into our roles as coeditors of The Red Wheelbarrow, we wanted to make this edition as inclusive of creative thought as possible. We are excited to feature writing and artworks from students and alumni who seek to understand the experience of the human condition. These pieces are reflections on lived experiences and knowledge gained, ultimately displaying the multidimensionality of being a healer, student, and patient.

As you read through these pages, we hope that you will feel inspired to share your creative works with us next year.

Please enjoy the 2024 edition of The Red Wheelbarrow.

Isabel Thomas ’27, Jonathan Chen ’27, Ryan Marawala ’27, Sarah Yang ’26 Co-Editors, The Red Wheelbarrow

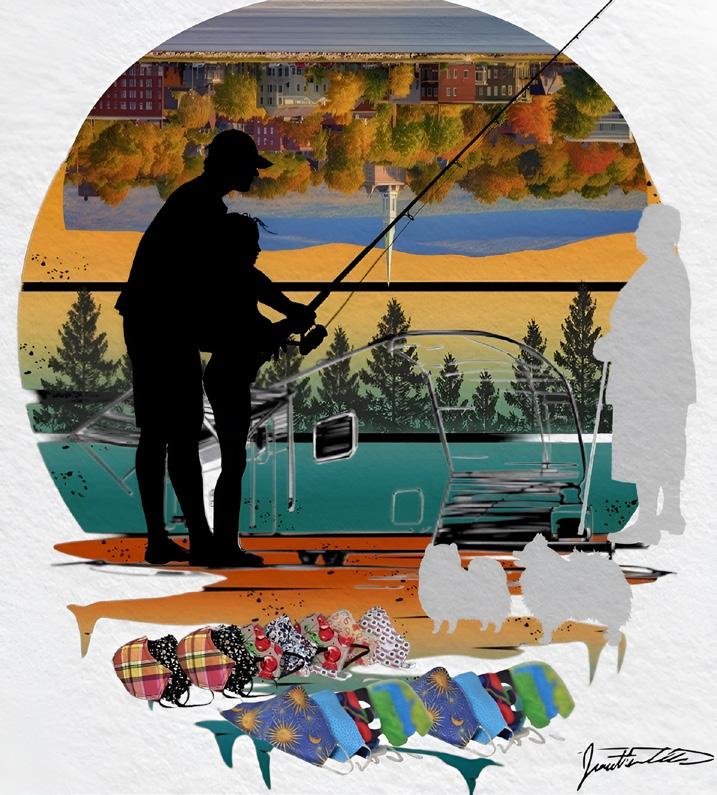

SARAH CHIAVACCI

Class of 2027, She/Her

Swimming in a fountain of youth, his life so bright,

A tale yet to unfold, promises of love’s true delight.

At the mere age of 20, he was not yet man, but far from a boy,

He managed to find love at a bar, injecting his life with unexpected joy.

Before long marriage bells quickly chime,

Hand in hand, they are excited but own barely a dime,

As you likely guessed, soon a baby arrives,

He teaches his son fishing and hunting, a father’s pride.

But not all love stories have a happy ending,

Sadly it is now time for this tale to adopt a more depressing rendering.

In his 40s, midlife crisis inspires a cursed shift, Alcohol’s allure shapeshifts into an unwanted gift.

His lover’s whisper soon turns to a deafening scream, He is not alone in paying full price for a misguided dream.

Soundtracks of silent car rides to hospital visits become their new routine,

A life undone, as he now lives behind his phone screen.

In his 60s, his impression is etched into a sterile hospital bed, He lays here alone on Halloween, fearing his liver is finally dead.

Today marks the birth of his love, his family left behind,

Nothing but a fading memory to a disenchanted mind.

To save him, surgeons dance with scalpels of hope,

Sutures symbolizing a healing rope.

Scared but hopeful, he clings to life, Amidst the darkness is the chance to make everything right.

He dreams of days before the pain,

Wanting nothing more than a second chance to live again.

Hopeful echoes entangled in sterile air, Doctors promise healing, but tears fall when prognosis of his desired future proves rare.

MARTIN R. BRICHE

Class of 2027, He/Him

I met Joe during his dinner. He sat barefoot on his bed, his tray facing the window in the hospital room. The lowceilinged room was darkened by the sunset and Joe had drawn the curtain entirely for privacy, making it difficult to see the other patient in the room. As I sat on his left side, Joe told me he was a slow eater because a few missing teeth made chewing laborious. I sat patiently looking away, glancing alternately at the sunset, which gave a warm orangey color to the student dormitory next door to the hospital, and at the television blaring out a decadesold syndicated cop show.

When Joe gave up on the pork cutlet on his plate and moved on to the custard, I asked him a few questions about himself, which he answered frankly but mirthlessly. He was in his seventies. Originally from Vermont, he had moved to Montreal and played the saxophone in a band for a living in the eighties. “Poverty,” a word he used, had brought him back to Vermont, where he had been homeless for an unspecified period. When I asked him what had brought him to the hospital, he told me he had fallen a few weeks ago without giving me any further

details. He looked forward to returning to Grand Isle, where he lived in a studio by himself.

In the middle of my questioning, he looked down at my feet and told me how nice my shoes looked. To him, they looked like shoes that could withstand heavy use in all weather. I thanked him and told him that he was right and that I had worn these shoes for about five years. I resumed our conversation. A few minutes later, the topic of my boots came up again, prompting me to ask about his shoes. Without answering my question, he rummaged under his bed. He put on a pair of comfortable-looking brand-new sneakers, and we discussed the respective merits of our shoes for a while. Later, I wondered if the change in our conversation told me more about who he was than the broad outline of his life I was trying to get at with my questioning.

When I asked him about the nurses taking care of him, he told me that they were all fine people and that he liked having male nurses around. He was more equivocal when I asked about his doctors. He compared hospitals

to a church where doctors are the priests because “they don’t do any of the dirty work.” I was intrigued on many levels by this image. From my own time in Quebec, I knew people there were not warm to the Catholic Church, and I wondered if his years as a musician in Montreal had something to do with this analogy. Because our meeting was close to its end, I didn’t get a chance to discuss what he meant. A few days later, thinking back about our encounter, I concluded I could only pinpoint what he precisely meant by making assumptions based on my own experience. Better to leave it a mystery.

As I said goodbye to Joe, his stare turned inward for a few seconds, and he thanked me for taking the time to talk to him. His tone was slightly more animated than earlier. I realized he didn’t often get to have candid conversations with others.

I enjoyed meeting Joe and getting a glimpse of who he is. It was a bit like reading the first pages of a book and being intrigued enough to buy it. In other circumstances, I may not have been curious enough to wonder about and

converse with him. The cover of his book is different from what feels familiar to me. I’m being reminded here that the stories that don’t immediately speak to me are the ones worth pursuing. They are the ones that will challenge my perspective and make me grow as a human being and a future doctor.

JONATHAN CHEN

Class of 2027, He/Him

Journey of Resilience: A Stage 4

Glioblastoma Patient’s Story of Nature, Community, and Positivity

ZAIN CHAUDRY

Class of 2024, He/Him

In the theater of healing, where life’s scripts unfold, I witnessed a drama, a story untold.

A massive transfusion, a protocol embraced, In the OR’s hushed chambers, a life to be traced.

The atmosphere shifted, urgency took hold, As tension wrapped ‘round each tale to be told. Scarlet rivers flowed, a battle ensued, Life’s essence measured, in units imbued.

A ballet of hands, in a dance against time, Transfusing hope in rhythm and rhyme.

Yet amidst the chaos, a sudden descent, Cardiac arrest, a moment misspent.

CPR’s cadence, a symphony grim, A novice’s hands on mortality’s rim.

Panic’s shiver, uncertainty’s gaze, In the labyrinth of shock, a first-time daze.

Blood infused, a lifeline in vain, A desperate chorus, a ceaseless refrain.

Code blue echoes, a call to the soul, In the theater of life, an unfamiliar role.

Emotions a tempest, too swift to grasp, Reality’s weight, a chilling clasp.

The patient’s pulse, a fragile thread, A code’s first steps, where angels may tread.

Bleeding persisted, an unyielding tide, A medical waltz, where fate did abide. In the silence that followed, a hallowed lament, Mortality’s whisper, a life’s final descent.

The haze of grief, a veil to wear, The first patient lost, a burden to bear.

A solemn reminder, life’s fleeting song, In the medical tapestry, where souls belong.

In the aftermath’s quiet, reflection unfurls, A journey begun, in the world of life’s swirls. For in the dance of medicine, joy and sorrow entwine, A poignant reminder of life’s fragile design.

Class of 2025, She/Her

January 12th, 2024.

7:00 am sign-out. I arrive sweaty from the walk up the hill, contemplating whether to shed my coat here in the fishbowl just to pick it up again when we mobilize up to the Cardiology floor or bear the next 15 minutes of overheating.

I got an MRI as a child once and thought this place seemed like an airport. Maybe, I understood both an airport and a hospital to be a transitive space. Likely, I was more struck by the high ceilings—buildings weren’t usually this big in Vermont.

Transitive: “of, relating to, or characterized by transition”.

8:21 am. I stop by his room to check in. Pre-rounding. I had one of those resident teams who insisted on prerounding with you if they were going to sign your note. A bit infantilizing really. I would ask my routine questions: “How did you sleep? Are you in pain?” Yesterday, he had responded by turning to the resident, “Doctor, when will my breakfast come?” I stood to the side. Let the resident take it from there.

But today is different. Today, he sits, his back to the door. The blue-black of the bruises on his arms stark against the blue-white of his gown. Eyes on the window. Today, he admits that he didn’t sleep. Today, he asks whether the resident will be in the surgery. “Doctor, will you be here when I come out?” he asks. Eyes still on the window.

Today, I forgive him for ignoring me. Maybe, I’m even grateful.

The gist: Had an NSTEMI at an outside hospital—on the cards floor for heart failure treatment—scheduled for a MitralClip procedure to treat his severe functional mitral regurg.

Fishbowl. Pre-round. MitralClip.

Yesterday we debated the utility of the procedure. (I say as though I participated as something more than observer.)

It was risky but it could buy time. We’ll continue to hold his anticoagulation due to bleeding. Hence the bruises. Ecchymoses. Echos of his past hospitalization. Evidence of past survival.

There was also the question of his medical literacy: it was his wife who was advocating for the procedure, not him. But he had agreed.

10:53 am. Update: Cardiothoracic surgery has overruled medicine. Heparin drip was restarted last night because of his history of Afib. Bleed out vs. stroke out: a balancing act. The anticoagulation will be just temporary, to get him through the surgery. A placeholder until a real plan could be made. Transitive.

My mom is British and my dad was in the military so I knew the airport to be a place of great excitement and great sadness. A transitive place of happy hellos and gloomy goodbyes.

13:06 pm. Teaching session begins. Topic: Acute Respiratory Distress.

It is Friday. Our attending buys us PokeWorks. I slide rice and edamame around my plastic, disposable bowl as we schematize hypoxemia versus ventilation perfusion mismatch. Multitasking. Intermittently texting a group chat of flight group friends sitting across the room about our Friday night plans.

13:49 pm. Epic chat alert populates my phone. “Unfortunately, he died during surgery,” the fellow writes to me and my resident. “Unfortunately.”

I take the resident’s lead. For some reason, I don’t want to be the first one to respond. I need to mimic his message, to parrot the right level of sadness.

It feels comical that I am sitting here being lectured on Winter’s equation. It feels frivolous. I feel distant. I text that friends group chat. “My patient just died :(” Frivolous. Distant.

“Oh, no”

“I’m sorry Liv” “What happened” They respond.

The session ends and we return to the hospital. In transit, I receive another Epic chat.

“Oh, that is heartbreaking, he was so nervous this morning,” the resident writes.

Why does it make it sadder to know he was nervous?

It is my turn to acknowledge that I have seen the message. “This is so sad.” is what I settle on.

In the workroom, it’s as if nothing has happened. “Are you ready to present the admin from this morning?” the

Continued on page 18

resident asks. “Sure,” I say. I don’t remember much about the admit from this morning. I remember him. I remember that his wife was optimistic for a few more “good years.” I remember that he’d slept poorly last night. That he’d been annoyed that he couldn’t eat this morning.

Disorganized presentation to follow. EP fellow pimping me on the side effects of certain antiarrhythmics. The right answer far beyond me.

That over, resident asks, “You can write the discharge summary, right?” as if I could say “no”.

Flight group. Epic chat. Discharge summary.

I haven’t even started the discharge summary. I thought I could start it tomorrow.

Discharge: a transitive verb. “to release from confinement, custody, or care.”

12:30 pm. MitraClip procedure started.

13:10 pm. Surgical ICU consult note started. Never needed, never deleted.

These are the things I learn as I frantically chart review.

“I remember when my first patient died as a medical student,” the intern suddenly remarks. He is balancing on

one of those balance boards for kids or yogis or surfers maybe. Frivolous. Distant.

Grieve versus play: a balancing act.

He isn’t talking to me, mind you, but to the chief resident. The two of them started recounting their own medical school traumas, patient deaths, idiosyncrasies of past attendings.

They have not asked me, the medical student, if this is the first patient I have had die. But what would I have said if they had? “Oh, I’m fine,” probably.

And to be fair, I can’t decide whether to be upset or relieved by their nonchalance. In fact, I’m kind of endeared. Reassured. Why else would they be taking this trip down memory lane if not to connect?

13:33 pm. After 12 minutes of CPR, he was declared dead.

13:57 pm. Procedure note signed. “Patient unable to recover” the surgeon wrote.

No, I am not upset at these residents, but I am a bit frazzled.

“What are you up to this weekend?” the intern asks the chief. They are having fun now. Frivolous? Distant? Reassuring?

I’m awed that they can seem so unfazed. Somebody has just died.

But I’m also aware that this discharge summary is the only thing that stands between me and my weekend. I’m aware of my resentment that I have to stay late.

I’m aware of how much easier it would be if the chief resident, who surely knows what he is doing much better than me, just wrote the summary.

I’m aware that I feel guilty for resenting this inconvenience. Somebody has just died.

But I don’t have time to make meaning of all of this because, mostly, I’m aware that I don’t know what to write. I am aware of the thud of that damn balance board crashing into the ground each time the intern falls. I am aware that I have never discharged somebody to death before.

Discharge: “to relieve of a charge, load, or burden.” Transitive verb.

“Unfortunately, the patient became severely hypotensive due to iliac vein perforation,” is what I settle on.

April 12th, 2024.

I’m studying in a Med Ed room overlooking the hospital. There’s an orchestrated commotion outside. They are washing the windows for spring.

I watch as a wet squeegee is hoisted to the furthest window of the sixth floor. Faltering as if on stilts. All I’m doing is multiple choice question blocks and yet it feels Frivolous. Distant.

I wonder what patients think of it as they lay in their hospital beds looking out the window. I wonder what he saw. Eyes on the window that day.

Still, I’m mesmerized. Maybe frivolous and distant but also kind of reassuring. Like things go on. Winter turns to spring. Transitive.

I know the hospital to be a place of great excitement and great sadness. A transitive place of happy hellos and gloomy goodbyes.

15:36 pm. The chief resident signs the summary. The intern says “get out of here—good work—enjoy your weekend. See you next week.”

Discharge instructions.

“Unfortunately.”

DALTON DOWD

Class of 2027, He/Him

A little boy is sharing a room with his five older brothers. He wakes up first but stays quiet for a few minutes enjoying the peace and quiet of an early-morning house. He rolls over and realizes that his oldest two brothers are already gone.

The little boy thinks to himself, “Fishing with Dad, I guess.”

As he lies there, he can hear the breathing of his remaining brothers, slow and even. He stares up at the ceiling and wonders if Dad will be angry when he comes home today.

It doesn’t take long for the smell of frying oil to lazily swirl its way through the cracks in the door. The aromatic wisps spin and twirl in the light coming from the space under the door. He hears a sizzling and smells the distinct scent of doughnuts; he isn’t the only one as he can hear his brothers’ breathing change. They inhale deeply and pop out of bed to get their first dibs. The little boy lets them go. As the youngest, he is in no rush to still get last pick. He can hear his siblings chatter in the kitchen as his sisters also start to wake up.

This is a typical Sunday morning at home. The little boy gets up and joins the rest of his family.

…

It’s 50 years later. The not-so-little boy is still the little brother as far as the family is concerned. It’s been a long time since the little boy has seen his siblings. The lot of them, scattered across the country, are like leaves in a fall breeze. He sits in a hospital room on Sunday morning watching reruns of some show he’s never seen. He isn’t really paying attention. He wishes he had a doughnut to go with his drink. He sips his coffee and looks out the window at the rain. He thinks back to a little boy sitting in a boat.

… It is finally the little boy’s turn to try to fish with his dad. He made sure that he woke up early to already be awake when his dad came for him. If he wasn’t, at best he’d be left behind, at worst he’d see the belt. Sitting in the boat quietly listening to the frog’s croak, and rain droplets plop softly into the lake, the little boy thinks to himself, “Is this always what my brothers did?”

He feels a nudge at the end of his line, he makes a quick switch, but the hook comes up empty. No worm, no fish, no luck. What he does get is an admonishment from his dad.

“Waste of bait, boy. Try again.”

The little boy silently wraps another worm around the hook and casts again. As he sits there, hair dripping and his dad grunting angrily behind him, he thinks, “I miss mom.”

…

The not-so-little boy flinches as the phone begins angrily ringing. Silently, he walks over and picks it up. It’s his sister in California. The conversation is short, and it boils down to one less sibling to not hear from.

He places down the phone and wonders when his turn will come, or even worse, when there are no more siblings to not hear from.

…

The little boy is old enough now to get his own job. His dad says that he can stop being a freeloader and get to work. His dad, already off fishing, is still speaking angrily inside the little boy’s head. Out loud however, his mom tells him to have a good day and smiles as she kisses him on the cheek and tucks a doughnut hole into the little brown paper bag clutched in his hands.

…

The not-so-little boy, now with his own not-so-little boy, wonders if his son will come to visit him in the hospital. He hasn’t seen him since the last time they argued, and he told him to “grow the fuck up”.

…

“Grow the fuck up,” the little boy hears from his dad. The little boy yells something back, not even sure what he’s saying exactly. He slams the door and leaves for work. He thinks to himself, “Cruel bastard”.

…

The not-so-little boy and the little boy are now one and the same. He sits next to his mom as the funeral service quietly continues. There are few people at the funeral, and even fewer tears shed.

…

The not-so-little boy and the little boy now sit with some of his siblings at a much larger funeral service. This time around, his mother has a special place in the room. There are many more people, and many more tears present.

…

The not-so-little boy and the little boy sit in the hospital room with his coffee, raindrops running their race down the window. Sitting in the peace and quiet, he frowns and thinks to himself, “How many tears will there be at my funeral?”

He thinks about those hectic Sunday mornings, fighting with his siblings over the last doughnut. He smiles and closes his eyes. He’s almost able to smell the dough and hear that sizzle. The not-so-little boy is little once again.

Class of 2025, She/Her

The Petals of My Kidney (opposite) If Only Thyroid Nodules Were Hydrangeas

Class of 2026, She/Her (left to right) Triptych of M2: Anki Remote, Stethoscope, First Aid

Class of 2027, She/Her

A Sway

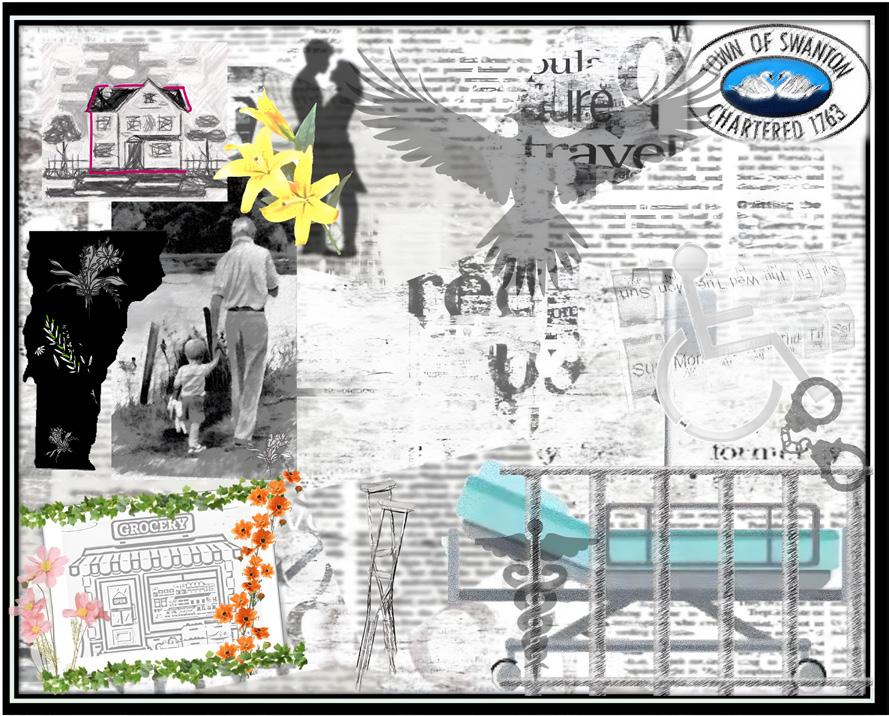

Class of 2027, She/Her

Born, Raised, and Sick in Vermont

Hematology & Oncology Administration, She/Her Equinox Preservation Trust, Early Spring

OLIVIA VELASQUEZ Class of 2028, She/Her

Who are you what do you do?

Is it OK if we talk to you?

Ask you for answers you don’t have, knowing there’s nothing we can do to give you the time back?

I used to sell cars, but now we buy time going back and forth.

My wife says I could sleep all day, dreaming up explanations for why it happened.

In the beginning, it could have come from anything: a stray cherry tomato I don’t remember eating, a cat that doesn’t exist. In the end, it was multiple things, a diagnosis with a missed cause, “toxoplasmosis,”

I think it’s called, to multiple rounds of chemo. But I missed the call with my grandson the most.

He lets his wife say the words. I wonder if it’s because he can’t say how he really feels that he doesn’t say much. But they’re both kind, the kind you’re not surprised to hear she usually makes the Halloween costumes for the grandkids in their lives who are out trick-or-treating while they wait here in this room.

When the scan results come back, we’ll know if the cancer did, too.

Hopefully, we’ll take our grandkids trick-or treating next year. Either way, we’ll take each day as it comes.

MEGALA LOGANATHAN, M.D.

Class of 2024, She/Her

“Paittyakari!”, a colloquial term in Tamil, the language spoken where I grew up in Chennai in Southern India, translates to ‘crazy woman.’ As I looked over at the cowering woman I was speaking with through the gates of my house, I noticed a rolled-up newspaper at her feet that was aggressively hurled at her by a passerby. She gave me a searching look, as if expecting fear, and I nodded reassuringly. I had come to acquaint myself with her over years of exchanging smiles and petting goats, as she passed by my house every weekend with the local goatherd, presumably her son. She spoke quickly and continuously, often into the sky, her facial expressions shifting from tearful one moment to joyful the next. Although I did not know what to make of this at the time, I sensed how people treated her and the heaviness and the negativity of the word Paittyakari weighed on me.

A trans-continental move to the U.S. when I was 18 and the subsequent cultural acclimation process challenged me to reconcile multiple identities, shedding parts of myself that did not conform to my perceived schema of what a medical student should be. This internal journey made it all the more surprising to find myself emotional in a dimly

lit hospital room while evaluating a patient alongside a colleague for a possible Transient Ischemic Attack.

After a thorough neurological evaluation, I carefully put her socks back on. I heard sniffles and looked up to see my patient with tears streaming down her face. “It’s been so long since someone even touched me with any kindness,” she confided. Pausing, I took a seat and asked, “What are you feeling right now?” My colleague quickly glanced at his watch as she responded, “You stand out here. Like me. Maybe you will listen,” With unrestrained emotion, she opened up about her struggles moving to the US from China, describing the daily challenges of navigating an unfamiliar world and the cultural constraints preventing her from sharing her difficulties with her husband.

Over 8,000 miles away from where I grew up, this patient was grappling with the same invisibility about mental health that I was so familiar with. It dawned on me that the stigma surrounding mental illness transcends cultural boundaries while being deeply ingrained within them. The resistance my tongue meets when forming English

words that sometimes betrays the fact that this was once not their home, now served as a reminder of my unique journey to this space. I realized the very parts of me I used to diminish myself became anchors for how I related to people. Our narratives connected us and revealed our commonality.

I handed her a tissue and nodded silently as I allowed myself to be engulfed in her feelings. I blinked quickly to resorb some of the tears that were threatening to spill over as my patient’s expression mirrored my own. In this silent exchange we affirmed each other in our own unique ways that our feelings were warranted and welcome.

“I give myself an A+” she concluded laughingly.

“I give you an A+ too” I responded, promising to return with resources in her preferred language that might be helpful.

Leaving the room to present to our attending, my colleague and I were approached by another student. “How was that?” he asked.

As I attempted to gather my thoughts and push through the lump in my throat, my colleague answered, “Crazy woman.”

RUJA KAMBLI

Class of 2026, She/Her

The Bakery

CHRISTOPHER PHAM

Class of 2026, He/Him

I don’t know his name

I cannot look him in the eyes

This veteran, he knew battle. Not the kind soldiers train for

The experiences he has had are sewn into every fiber of his being

I am about to be taught a lesson

My teacher beckons I join him, I wonder if I have done wrong.

Ashamed, I cannot meet my teacher’s eyes

For these eyes have seen much

Perhaps God himself

Yet despite their fullness, these eyes have now fallen flat

The humor and the humor that once filled them gone

Did he have humor?

I don’t know his name

I don’t know him

His values, his beliefs

Why he is talking to me

And now I know him more closely than I have ever known another human

Without saying a word, he has told me more than anyone has ever before

The lesson is over

I don’t know his name

And he has poured himself out for me

I am astonished

Why anyone would give so freely to someone so unskilled, so undeserving

Is it disrespectful?

To take so much

Without even giving in return the simple decency of knowing his name

I cannot know his name

But I can honor it

His eyes closed

I have burned his form into my memory

And his lessons onto my heart

This reflection with gratitude to the unnamed man who was my anatomical cadaver donor

MOHAMAD K. HAMZE

Class of 2024, He/Him

The hospital lights seem brighter today as I stride in

The AC a bit cooler than usual always running no matter the weather.

Every anesthetized patient drifts off to sleep a little more easily

Every surgery complicated but without complications.

Room 14’s call bell is louder than before “more water, please”

Room 23 is much more antsy than yesterday but at least today he’s going home.

Over my morning coffee I open a live stream with a single tap volume off

Over 6000 miles away a cancer center, or was it a children’s hospital?

now just rubble and ash.

It’s loud in this hospital, but I’m struck by the silence the distinct lack of explosions outside

It’s hectic, but I’m struck by the calm the relative absence of sniper fire.

Here, there are no patients without a bed no babies without a parent

Here, the electricity is always enough to keep the surgery theater’s lights on.

To die here is a spectacle, a play bathed in spotlight and our time to mourn is a luxury

To die there is to die unseen, in the shadow of a thousand fires neither in mystery or in certainty.

A screenshot replaces the live stream in my feed brightness all the way down

A screenshot of a WhatsApp message from a resident physician meant for a friend but sent to the world:

“We’re alive but we’re not okay.”

RUJA KAMBLI

Class of 2026, She/Her

The Physician’s Hand

ARYA KALE

Class of 2027, They/Them

My life exists between bites of ripe mango. Sinking my teeth into its golden flesh, slurping its sweet nectar, and treasuring its deep flavor deserve my full attention. When eating mango, it reminds me to focus on the present.

My perpetually expanding flashcard deck, my sweatdrenched clothes sticking to my body, my shame when the attending physician called on me today to describe the red flags of Dengue Fever, and I had to say that I had not reviewed Dengue because it isn’t common in Vermont, and the other students laughed – none of it matters. There is only mango.

I can divide this first week in Santo Domingo by mangos.

The First Mango is a Dasheri mango, carefully selected from a Costco 14-pack and cut into cubes. Along with fresh raspberries and blueberries, it tops my pancakes for my penultimate meal on U.S. soil (second to my first Shake Shack burger).

First Mango marked the start of my journey, a time filled with apprehension and excitement. I wondered if my Spanish skills would be enough to get me through a full shift at the hospital. The Dominican dialect is notoriously difficult to understand, even among native Spanish

speakers, as D.R. residents speak rapidly and truncate many words. After an uneventful flight, an easy ride to the Ogandos’ home that tracked along the coast, and a delicious double serving of Los Tres Golpes for dinner, however, I felt more at ease. I found I could hold a Spanish conversation in all these settings, so long as I stayed focused and didn’t lose track of the main topic. This feeling continued into the next day, where, along with my classmate Stefa, I toured la Universidad Iberoamericana, branded as UNIBE, where we were technically registered as exchange students. We explored UNIBE’s main campus, trying out the cafeteria, library, and gym.

Thank goodness for Stefa. She is a native Spanish speaker, and during the first three days I could turn to her whenever I didn’t understand a question. The early Uber rides and lunch lines were much less awkward with her at the conversational helm while I scrambled to straighten my language bearings.

The Second Mango was a surprise treat after the first full day of clinical rotations and navigating the local supermarket. I had never shopped in Spanish before. The store layout felt weirdly familiar, but everything else required more mental gymnastics than I anticipated –pesos to dollars, kg to lbs, remembering how much food typically costs in the States, and using all the data to determine what was worth buying – not to mention every item was listed in Spanish. Thank goodness for Stefa.

We arrived home in the late afternoon, staggering from the heat and humidity. I still didn’t understand how people deal with this level of heat every day without air conditioning or even a fan – I most definitely take these tools for granted. After a day full of intimidating attendings, translating medical terminology, and lugging four bags of groceries and books up four flights of stairs, all I wanted to do was take a 12-hour nap to fast forward to the next day.

And in walks Señora Marisa Ogando, grinning ear to ear as always, followed by Señor Jesús Ogando with a massive tub of small mangos. I cut into one no bigger than the size of my palm with a single tear of leaky syrup encrusted on its marigold peel. The Second Mango isn’t remarkably juicy or sweet, yet its flavor leaves my tastebuds starstruck. I don’t know how else to describe it.

I haven’t tasted a mango with such developed flavor since I last visited my grandparents in India over a decade ago.

That night I sleep so, so well.

By the time of the Third Mango, I had learned translations for “un chin,” “bajo a boca,” “tranqui,” “tigueraje,” and other Dominicanismos; had seen clinical presentations for HTLV-1, malaria, and other infections that I hadn’t seen before; and had been called “doctor” for the first time. I tried to explain that even though I wore scrubs and a white coat I was just a student, and fortunately all the other person needed to know was where the closest bathroom was. Still, I didn’t feel comfortable with the title.

My biggest takeaway from this first week, which I shared with the Ogandos while preparing the Third Mango, was how relaxed nearly every physician seemed. The hospital faculty shared great community where everyone greeted each other upon entering and leaving a room, people traded stories, and no one was ever in a rush. Emergency work still received the urgency and efficiency it warranted, but not at the expense of stress-free living. All healthcare providers walked at their own pace discussing theoretical cases or developing a plan together. Every patient, student, co-worker, visitor, and front door supervisor gave and received a hello, how are you. There was more physical contact than I was used to, too – grabbing an arm in affirmation or to get someone’s attention, resting hands on a shoulder while examining the same computer screen, and lots of hugs (although this seems to be only amongst physicians). These behaviors and this pace of life are considered unprofessional in the U.S., but in the D.R. they didn’t interfere with work at all. I didn’t know how, but I wanted to learn how to bring back part of this culture with me. It was a comforting atmosphere, even in the stressful hospital environment. I wondered if this energy is the same across all UNIBE hospital departments, or if it is specific to Infectious Diseases.

The Third Mango, an Ataúlfo mango, is by far the best. The pulp is a potent yellow orange, about halfway between amber and pumpkin color. It boasts a juicy and sweet bite that packs the same strength of flavor as Second Mango. A satisfying end to a stressful week of new information, unending heat, and constant adaptation.

GOERNER, M.S.

Cellular, Molecular and Biomedical Sciences, She/Her Crocheted Microbes: Brucella, COVID-19, (opposite page) Salmonella, Toxoplasma Gondii

JASMINE BAZINET-PHILLIPS

Class of 2025, She/Her

The premise of surgery is a balancing act: anticipation of relief weighted by the terror of a performance yet unknown. The operating theater functions like an inviteonly, highly controlled ballroom.

Prior to the surgery, the patient and the surgeon are greeted by an organized frenzy of dancers preparing for the waltz. In the theater, a nurse meticulously organizes the surgeon’s instruments and ceremonial garb, while the anesthetist prepares a promising elixir.

The operating room is a ballroom of grandeur, full of expectant participants all awaiting first the introductory entrance of the patient, expectant of the grand entrance of the surgeon. Upon entrance to the operating room, if etiquette is not forgotten, the surgeon will bow to the patient situated on the table and reassure the patient. If time does not allow for niceties, the surgeon will enter the room briskly, as if their steps demand the commencement of the long-awaited waltz.

Regardless of the surgeon’s chosen entrance, the anesthetist, the ballroom’s grandmaster, lulls the patient with twirls and swirls of the mind, guiding the patient to weightlessness in the waters of Lethe.

The accompanying backstage hands, as if somehow jolted by the surgeon’s resoluteness, begin to apply a tonic solution to the now unclothed patient in the center of the room. Once properly sterilized, the crew applies ceremonious drapes to the body, which contains a mind subconsciously floating in the ether. The drapes are all-encompassing of the person’s figure, only leaving the portion of the body relevant for the impending incision. The drapes somehow simultaneously remove the person and the body from the room.

The surgeon is now dressed in ceremonial garb, her arms centered in the middle of her chest to preserve the sterility of her being. At her behest, the spotlights in the room highlight the area of the first cut. The first cut is precise, meticulous, and methodical, and it is joined by an audience now all peering over the surgeon and the body.

The rhythmical strokes of the scalpel and the contortion of the flesh and bones, to ensure the right positioning for the completion of the performance, simultaneously entertain and perplex the onlookers. Despite the hesitation of naïve observers, the surgeon is persistent, and her triumph ends with a sutured bow.

Without any further ado, the anesthetist finds the mind wading in the gentle waters and guides awareness back to the center of the room. The patient once again joins the surgeon and acknowledges the spectators, fleetingly reminding her body of consciousness and the meaning of being. The surgeon, relieved by the return of the patient to the operating theater, gracefully thanks the patient and the accompanying backstage hands and exits stage right to repeat the waltz.

MICHAEL GREENBERG

Class of 2027, He/Him

The great illusion of winter is that time slows

Walking outside at midnight after a storm

You may be convinced of this

The snow silently absorbing ambience

So cunning is the illusion that the season plucks the vapor out of the air

And lays it on the earth in display

Do not let this fool you

Put your ear down and listen!

Gently crack the ice on the brook and see!

The water flows, babbling away as it does

Observe the great pines that stand bolted to the forest floor

They can shoulder the weight of this illusion on their strong limbs

Closer to you however

The young bounds bend and strain and stretch

Disturb the weight that they carry and watch their sign of relief

As winter comes tumbling down

He/Him

Isolation

THE 2024 LITERARY AND ARTS MAGAZINE OF THE UVM LARNER COLLEGE OF MEDICINE