The University Times Magazine

Siothrún Sardina takes us through an afternoon in the botanical gardens as seen by a colourblind person 6

Siothrún Sardina explores how learning foreign langauges changes your perspective on the world

Eleanor Moseley reviews The Banshees of Inish erin and its depiction of male friendships and small Irish towns

The University Times Magazine Contents

4 Of Orange Leaves and Green Sunsets

Ai a Edhellen, i Lam Nín

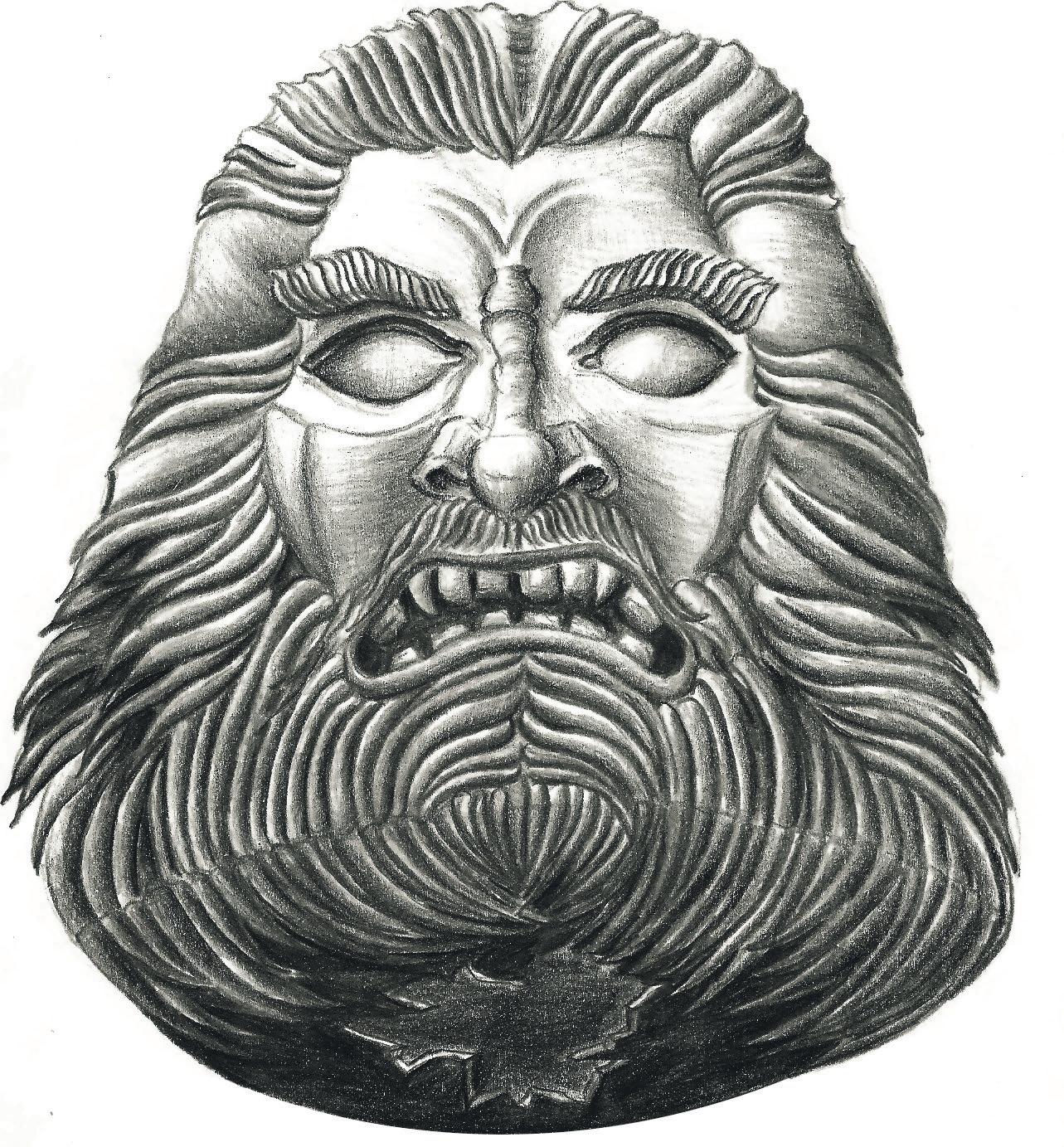

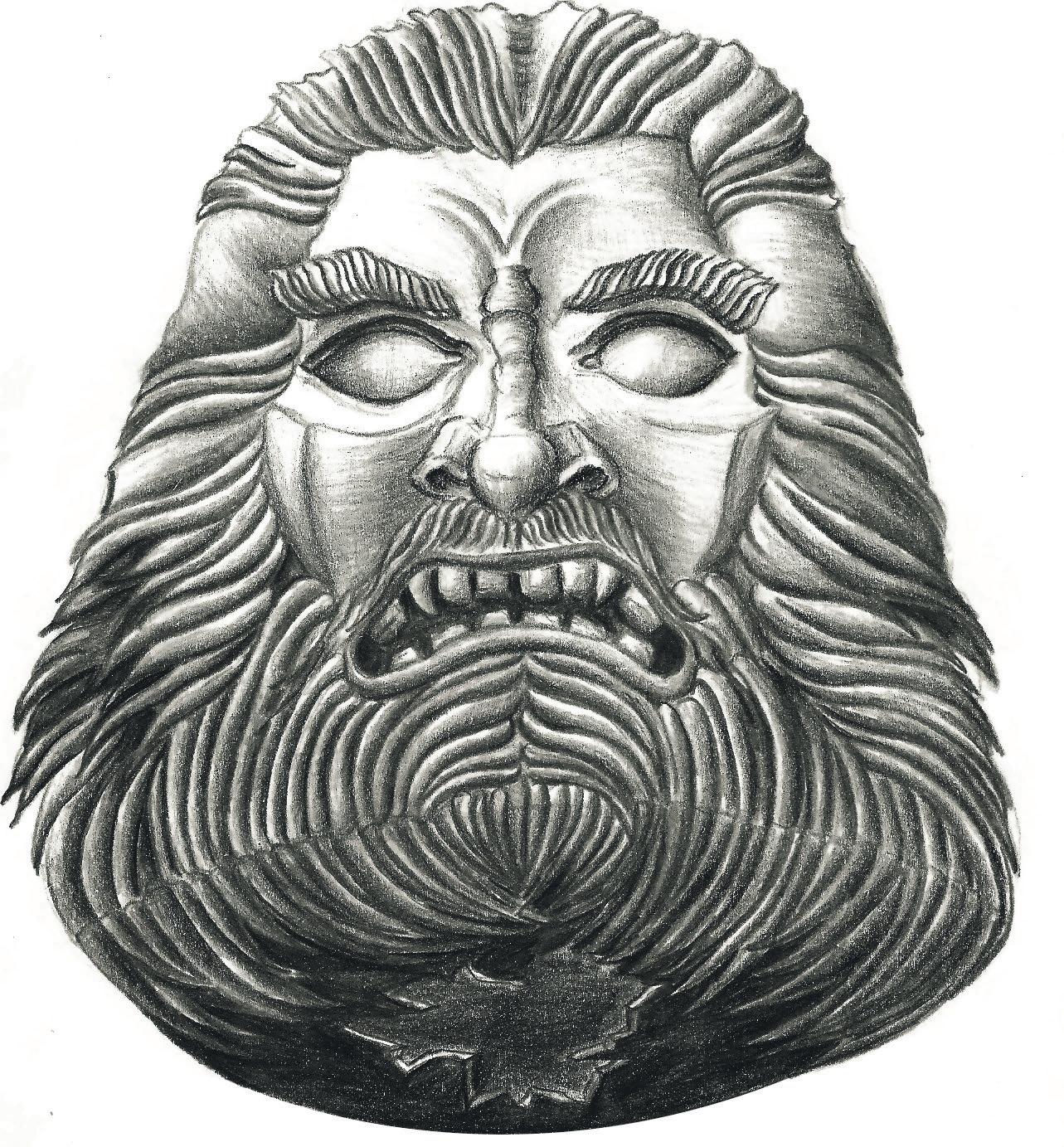

Above:

Back:

Front: Ailbhe Noonan

Siothrún Sardina

Siothrún Sardina 8 Banshees and Barren Lands

10 Notes from the Pop-Up Gaylteacht 9 Cannibalism in

and All

Bones

2 | Magazine

Eleanor Moseley reviews Bones and All and its depictions of addiction and desperation

Welcome to a very unique edition of The University Times Magazine and to Radius! With everything that has happened, it is only natural that the Magazine and Radius, our two supplements, would look dif ferent this time around, so I made the decision to combine them into one publication covering both introspective examinations of the world and a look at what’s happen ing in Dublin’s ever-vibrant cultur al scene right now.

We have some incredible content in both publications on the theme of unique visions and different perceptions of the world, ranging from an examination of language to an exploration of what it’s like to be colourblind to reviews of two movies that capture a sense of iso lation and desperation in their cast and locations.

In the Magazine, Siothrún Sar dina takes us on two different but connected journeys looking at how he sees the world as a colour blind person and how he learned to use language to fill in the gaps left by a very narrow colour wheel.

Set on a single afternoon in Dub lin’s Botanical Gardens, he takes us through an afternoon trip with a close friend and how differently the two of them saw the vibrant flora and fauna. As an excellent follow-up to this, he reveals how learning Classical Sindarin (yes, Tolkien’s Elvish), ASL, Irish and Spanish have taught him to see the world in vibrant colour even with out the colour wheel.

In Radius, Eleanor Moseley, our Film and TV Editor, reviews The Banshees of Inisherin while look ing at the themes of male friendship and claustrophobia in a small town set against the beautiful back drop of Inis Mór and Achill Island. She also reviews Bones and All, an adaptation of a novel of the same name, exploring its haunting de piction of the American landscape and its themes of desperation. We also bring you updates from the Abbey Theatre about their newest programme and Siothrún discuss es what An Cumann Gaelach’s PopUp Gaylteacht means to him as a bi person.

So, dear reader, while this publication may not take its usual form, I hope that you appreciate the articles contained within. They bring a unique perspective on the world that I have greatly enjoyed exploring and they showcase the talent and dedication that persists within the paper. If you would like to get involved with our magazine, drop us a line at edi tor@universitytimes.ie – I cannot wait to read your work and grow new ideas to gether.

Ailbhe Noonan

“One death is a death too many, plain and simple. I think every year the health and safety standards on the sites are improving, at least on the World Cup sites, the ones that we’re responsible for”

Hassan Al-Thawadi speak ing on the alleged deaths of migrant workers at the Qatar World Cup

Like babe, these are ancient figures thosands of years old with thosands of stories, what’s so wrong with sug gesting Fionn Mac Cumhaill would drive Toyota Yaris”

The University Times Magazine Introduction

“I love it when people com plain that modern interpreta tions of ancient myths aren’t accurate enough

2 | Magazine QUOTE

@Roisin_McNally

The Mariupol Theatre in Ukraine following a bombing conducted in early March

TWITTER

Of Orange Leaves and Green Sunsets: A Day in the life of a Colourblind Person

Siothrún Sardina Senior Editor

Iremember well the day: the early-Summer sun marking early af ternoon, a mid-day blue sky not yet descend ing into purple. Green blades of grass about us reaching ever-skywards, full of colour: not quite vi brant enough to be called red, and yet not so dull as to fade into pink. The gravel path on which we walked long having for gotten the fallen leaves turning green in the Au tumn.Small stones about us marked with subtle greens and blues as they crunched under our feet.

We turned down a single path, choosing without particular cause the first trail to explore in the gar dens.

She would have seen white flowers springing up towards the warm sun, rows of green leaves streaking against the sky as towering trunks and branches held them aloft. One in particular must have caught her attention: a tree covered in reddish flowers, jutting out against the green background like the sun shining through the sparse white clouds

above.

Each tree painted in light and colour with thousands of brushes, the sturdy brown bark of each branch giving even more vibrance to the glowing reds and greens of leaves and flow ers, the blue sky in the background giving a cool cast to the scene.

In my world the paint er had but one brush. The browns of bark and branch flowed seamlessly into green leaves. Layers of green upon green slowly faded into a more vibrant, deeper red in the centre of the path before us where

the red-flowered tree so subtly distinguished itself from the greens about it. Above its proud branches, the sky stood in stark con trast to all below: its blue colour so alien to red and green and brown alike that the small forest had all the allure of a full moon casting rays into the night sky.

Further on we tread along thin dirt paths in a sea of flowers, the occasion al boulder giving a brief break from the backdrop of trees further outwards from the trail.

In her sight, yellow and orange and white flow

ers reigned over the rocky ground, their vibrance bursting forth against the less-assuming backdrop. Further along, thousands of shades of green on the trees would seem a more distant reflection of the lighter-green shrubs and vines before us. No two shades of green ever re peated, each new flowering shrub and winding tendril possessed of its own inter pretation of the colour.

My eyes saw pink rocks scattered as a backdrop to each flower, their pink at times seeming to blend with the faint reds of

4 | Magazine

shrubbery leaves. Other shrubs bore leaves with all the vivacity of an orange flame, their leaves akin to the central stand of yellow flowers, though those glowed with a much greater vibrance. The trees far away stood out against these visions, their darker greens much in opposition to fiery leaves on the small er flora surrounding us.

It was as this that we walked – past stream and pond, over wooden bridge and stone steps, under tree or sky, paths lined with pebble or dirt. And if I saw reds in the wood, pinks in

the stones, and noted a near-perfect reflection of the sky in purple flowers, who is to say the world is otherwise?

If she saw brown wood en planks and grey stones who each in turn made all the other colours stand out the more, if she saw in purple flowers a distant cousin of the sky rather than its twin, who am I to contest the allure of her view?

Two worlds we walked in, not one, though each step was taken side-by-side. I should be a fool to call one the more vibrant or the more beautiful – similarly,

nor can I claim so deep an understanding of her vi sions as I had of my own. To her, I know, was a beauty entirely different, though no less stunning.

With many words we would exchange our sights – the two worlds merging as one, two perspectives giving another lens into the entrancing colours painting elegant scenes about us. I learned to see the world in a second light, and I should like to think that she was blessed with knowledge quite similar to mine.

To each the world of their

Each tree painted in light and colour with thousands of brushes

own perceptions, their own enchanting world of colour – and to each and the alluring beauty of sharing them.

No two pairs of eyes have ever seen exactly the same. And indeed I have nev er seen the iridescence of the sunset that my friend would remember from that night after we parted. But as I watched the deep purple sky shift into flamelike layers of green and or ange about the horizon, as I gazed upon the waters glow so vibrantly that the violet sky seemed blue in their mirror, I doubted that any other world was ever so lovely.

Images taken by Siothrún Sardina for The University Times

5 | Magazine

Ai a Edhellen, i Lam Nín: Learning to see a Monochrome World in Colour

Siothrún Sardina Senior Editor

Ihave never seen the world the way most people do. Being co lourblind, my world is full of green wood and purple skies. To me the colour wheel is symmetric, and both of the colours that remain are rarely worth distinguish ing. Many times I have wondered how another might react to my perception of the world, or how I might react to theirs. Then I started learning Elvish.

Yes, Elvish. Classical Sindarin to be exact, with a little dialectical flavouring of the wood-elves sprinkled here and there, much like the gems of Donegal and Connema ra strewn through my otherwise vague ly Dublin Irish. Add some Spanish and some ASL (American Sign Language) to the mix, maybe a little Italian or Welsh on a good day, and all of the sudden I find my self in the most pecu

liar situation of being able to distinguish more languages than colours.

So I did what any co lourblind linguist would, and I became a painter. Of course, when I dipped my brush I accidentally picked up Sindarin in stead of blue, and all of the sudden was left with a beautiful monochrome sky: “Ai a Edhellen! Gin melin, i lam nín!”

Remembering the sec ond colour I quickly hastened for red – that would make some won derful leaves. But alas I failed once more, and found the words “Ceard sa diabhal atá dhá dhéana’ a’d, a amadáin!” scrawled all over the canvas like leaves blowing in the autumn wind. It seemed

that I had dipped into Irish rather than red.

Now certainly anyone look ing at this painting would have taken me for an amateur struggling in vain to copy Jack the Dripper. For by the end I had a bright Welsh sun over vibrant ASL roses intermingling with glowing Spanish sunflowers and bright Italian lilies.

It was about time I realised I was not a painter.

But what if I saw the world not in colour, but in language? After all, what is colour but a different perspective on the same thing? A rose is a rose, be it red or blue or yellow. But can I not say, a rose is a rose, be it meril or rós or rosa?

I then asked myself not what it means to see the world in “full colour”, but what it means to see it in only one lan

guage, or in many. What does it change when a whole rainbow of languages gives you your choice of words, when a thing may be known not by one name but by seven, each with its own shade and hue? What does it mean to see in thought and poetry, to feel in every word the myriad of per spectives and interpretations that constitute its being?

So I closed my eyes to both colours I could see, and I watched and listened to the languages of the world.

Two of the first words I learned in Sindarin were “es tel” and “amdir”. Both might mean “hope”, though those three words have remarkably distinct meanings. The En glish “hope” is broad: it speaks of a desire that unknown events be favourable, or that good prevail over rising tides

6 | Magazine

of adversarial circumstanc es. Its primary use is an ac tion: I hope. It is something that is done, a choice that is made and a dedication in the mind.

But to step back, for a moment, to the two kinds of hope Sindarin expresses: estel and amdir. Estel is the sort of hope that does not despair or abandon the one who has it. It is a hope that keeps hoping even in the darkest of times, because it is steadfast and believes in hope for its own sake. It is a hope that gives comfort.

Amdir is different: it is the sort of hope that is based off of reason, that seeks a way for light to come out of the dark not by chance or desire, but because the one who hopes sees a way that the hope can become a reality. Amdir is a hope that invites action and change.

And then to ask the same of Irish? “Dóchas” is “hope” in broad terms, but it is a hope that cannot be sepa rated from trust. It can be put into something or tak en out of it, and it speaks not only of a desire for something, but an expectation or trust in it occuring. Yet it is not commonly used

in action: “súil”, literally meaning “eye” is the word used to convey the idea of “I hope”. To hope in Irish is to “have an eye” for it – in other words, to see the end you hope for and watch it approach.

Many times and many days I have felt hope in all of those senses. They at times overlap – hope that does not fail, for example, can also be based off of reason. Yet in each I find another way of perceiving the world, another lens through which to under stand the reality in which I live.

As I walk the world, I see everything in the lenses of the languages I have learned and through the perspectives of the cultures they come from. If I look up at night I see the moon, i ruan and an gealach all at once. To the Sindar I Raun is The Wanderer, one that traverses the sky and whose wanderings define the months. To the Irish an gealach is known for its brightness that shines through the dark of night.

I look up and I see it all at once.

And perhaps this is the view others would be more accustomed to seeing when looking upon a rain bow, flowers, or even a city under a moonlit sky – different hues and shades in termingling, overlapping, fading into eachother even as they stand apart. What colour does for most, lan guage does for me.

They say you cannot create a new colour. That no matter how hard you try,

you can never conjure to mind an image of a colour other than the ones you have seen before. I never could, at least, and not for lack of trying. If any others have – well, colours were never exactly my strongsuit, as I am sure you can imagine, and theirs would be a feat that lies on a dif ferent path than that one I currently walk.

After all, this question of a “new colour” has con cerned me less than that of a new perspective. I ask instead if you can create a new language, and what it would mean to paint the world in its view.

That’s part of why I start ed learning Elvish. Sindarin Elvish is, after all, a construction of Tolkein’s. It reflects a world and a culture so fundamentally different from those of our world that it can speak of lore and beauty in entirely new terms. Yet unlike co lours, these new things are something you can actu ally comprehend, actually see in your mind’s eye.

I can see “i vanadh” – that which is either final doom or final victory. One word that means both, one word that binds them. And such a concept should be of no surprise: to the Sindar who speak to estel and know of hope that would never fail as manadh approaches, it is easy to see how to the end they can see a ray of light and hope that doom will become victory, and finali ty will once again stand on the side of righteousness no no matter how eminent a dark end seems: because

that hope never left, be cause doom and joyous vic tory can interchange in the blink of an eye.

So I became a painter of words. I strive not to create new scenes or interpret the world in colour and vision – though such an art is by no means lesser. But I find my amdir and know that my hope for understanding the world comes from the place I know best: language.

I learn, I see, and I even create languages for their own sake. Each one is a new impression of the world, a new way of placing myself and my experiences in it. A new way of expressing myself, and a new shade of meaning I add to every part of the world about me.

I have never seen the world the way most people do. To me the trees of lan guages grow intertwined, yet each one’s leaves speak of a different beauty. Many times I have wondered how another might react to my perception of the world, or how I might react to theirs. But now I know: and it’s about time I learned to see the world in another lan guage’s colour.

Image taken by Siothrún Sar dina for The University Times.

7 | Magazine

To me

the colour wheel is symmetric, and both of the colours that remain are rarely worth distinguishing

It was about time I realised I was not a painter

The Banshees of Inisherin: Male Friendships and Hopelessness in a Bleak Land

Eleanor Moseley Film and TV Editor

The fracturing of friendship can be a heart-breaking thing, as The Banshees of Inisherin reminds us. Should we sacrifice being liked by our friends in order to be remem bered by history? Martin Mc Donagh’s black comedy dra ma, which premiered at the Venice Film Festival earlier this year, is a compelling and moving exploration of male friendship, the claustropho bia of small communities, and the extent of desperation in the face of an unanswer able question.

Pádraic Suilleabhain (Col in Farrell) and Colm Doherty (Brendan Gleeson), life-long friends on the fictional Irish isle of Inisherin, have shared pints at the local everyday for as long as anyone can remem ber. The film opens as Pádraic takes the well-trodden path down to Colm’s house on the way to the pub, when he is in explicably rebuffed with the statement “I just don’t like ya no more”. And so it begins. As the film unfolds, Pádraic, pitiful and nonplussed, seeks to discern why Colm broke off their friendship, and to heal it once more. Other characters weave in and out of this pur suit including Dominic Kear ney (Barry Keoghan), a trag ic village fool in the endless quest for female company, and Siobhán (Kerry Condon), Pádraic’s sister who tends to their house and silently wish es of a life free from the con fines of Inisherin.

The film is set against the backdrop of the Irish Civ il War, as grenades and the crack of gunfire can be heard from the mainland. Mc Donagh, however, blurs the divides between sides and emphasises the confusion of conflict. “The Free State are

executing a couple of the IRA lads … or is it the oth er way around?” ruminates Peadar Kearney (Gary Ly don), the village police man.

This muddying of the complexities of strife is echoed within the ebb and flow of Pádraic and Colm’s friendship – as they teeter on the edge of potential reconciliation, they crash down into an even more in surmountable chasm than before. This micro/macro cosmic parallel, however, doesn’t quite match and is a touch convoluted as the end of the friendship is based on individual griev ances, while the Civil War broke out from fundamen tal political differences.

This thematic lapse is one of, if not the only glitch within the film. The plot remains tight as both Pádraic and Colm spiral in their respective ways. Banshees takes the darker, more sinister turn exactly when needed, precisely as

Pádraic’s questioning of Colm becomes more wild, more desperate, and more incessant. And when the film takes its dark turn, it is chilling. Pádraic and Siobhán stand, shocked into silence, as blood drips down their front door.

The Banshees of Inisher in’s true talent, however, lies in the seamless and constant oscillation be tween humour and heart break. McDonagh’s script is brilliant, eliciting rau cous laughter from Pádra ic’s befuddlement one minute, and silencing au diences with heartrending moments of desperation and sadness the next.

Its treatment of lone liness is just as stirring, with the singularity of the isolated characters high lighted against the vast, ancient beauty of the Irish landscape. The cinematog raphy is therefore equally notable, as cinematogra pher Ben Davis’ sweeping wide shots encompass the

breadth and magnificence of the Irish land and ocean, as well as a few extraordi narily well-chosen close ups, that excellently serve to elucidate the respective characters profound sad ness.

The leading actors of the film are a united tour-deforce and the performanc es of this ensemble cast are a brilliant and deserved spotlight on the Irish film and theatre scene. Colin Farrell has been tipped for an Oscar for his portray al of hapless and pitiful Pádraic, while Brendan Gleeson is magnificent as he slowly divulges Colm’s existential despair.

There are two supporting actors, however, who de serve a special commenda tion above the rest. Barry Keoghan is scene-stealing as Dominic Kearney. He is young, foolish, and not the sharpest, yet is a victim to abusive circumstances that give him an aura of pro found tragedy and wistful

ness. In addition, in Kerry Condon’s performance as Siobhán, she perfectly captures her inner desire to set herself free of the claustrophobic village as well as the conflict that her hopes have with the need to keep her brother com pany in the safe familiarity of Inisherin.

The Banshees of Inish erin follows Martin Mc Donagh’s thematic thread within his filmography of dark comedy and a slow devolution into violence. It is a must-see for fans of his work, and a vital view ing for Irish audiences in particular, who are sure to resonate with the familiar ity of the film’s community and true Irish humour. It is a powerful film, steeped in grievance and desperation. A film, as Siobhán writes in a letter to Padráic, about “bleakness, loneliness, grudges, and despair”.

8 | Magazine

Photo by Jonathan Hession

Cannibalism, Desperation, and a Cross-Country Trip in Luca Guadagnino’s Bones and All

Eleanor Moseley Film and TV Editor

Bloodlust and the hunger for human flesh amid the plains of the 80s Midwest is not the typical setting for an achingly poi gnant coming of age love story, but Luca Guadagni no pulls it off spectacularly in Bones and All.

Maren Yearly (played by Taylor Russel), alone after being abandoned by her father and plagued with cannibalistic cravings since childhood, is travel ling across America to seek out her mother. Vulnera ble and lonely, she stum bles across Lee (played by Timothée Chalamet), a fellow outcast and “Eater”. The couple embark on a journey across the coun try in a bid to embrace their identity, their past and their love for one an other, all the while being haunted by the trappings of their bloody affliction.

An epic odyssey of ad diction, abandonment and hunger, Bones and All deftly combines the gore of the horror genre with the tenderness of a com ing-of-age story, a tale that balances on a knife edge, teetering between mo ments of bloody violence and the most profound intimacy. In this combina tion of genres, the film is expert at maintaining the undercurrent of darkness and pain beneath the ve neer of blossoming love. Both Maren and Lee bat

tle with their identity as cannibals, and Bones and All certainly does not shy away from the brutal bloodshed that ensues as a result.

Bones and All is strik ingly original in its al lure. Inspired by pho tographer William Eggleston’s haunting portraits of rural Amer ica, Guadagnino effort lessly paints the land scape of the film with a beautiful yet mel ancholic haze, evok ing the desolation and loneliness of Maren and Lee’s journey. Even the simplest of diners and abandoned houses are photographed with a breathtaking beauty,

not to mention the sun sets and vast landscape of the plains they camp on.

The camera work is just as original, with gentle zooms, fluid movement and a spontaneity that captures the youthful ness and intimacy be tween Maren and Lee as they drift between the margins of society. A special commenda tion should be made for costume designer Guilia Piersanti, reunit ed with Guadagnino after working togeth er on Call Me By Your Name (2017). Maren and Lee’s costumes perfectly crystallise their tousled and rough beauty and

effortlessly capture the desolation and neglect from living as outcasts. While the central thread of the narrative becomes slightly convo luted and tangled midway through, the film is buoyed up by the ac tors’ intensely profound performances. Taylor Russell stars as Mar en, and she effortlessly captures her character’s loneliness and fragility anchored with a deep strength and courage. Timothée Chalamet, too, is outstanding as Lee, possessing the hard edge of a drifter on the fringes of society and yet is gentle and pained deep down, an essence

that arises in scenes of intense vulnerability and intimacy that leap right out of screen into your heart. Mark Ry lance is just as unforget table as Sully, a seasoned ‘Eater’ that possesses a deeply unnerving creep iness.

Bones and All is a qui et triumph, and whilst it hasn’t made waves in the box office, it is Gua dagnino at his most ac complished and virtuo sic. A portrait of carnal need, of blood and and love, of fractured indi viduals and lost identity, Bones and All is an ach ing, subtle tour de force.

9 | Magazine

Photo by Yannis Drakoulidis

Pop Up Gaylteacht: Aer-áthas na hOíche

Siothrún Sardina Senior Editor

Siothrún Sardina Senior Editor

Chomh luath is a ch uala mé trácht “Ga ylteacht” is cinnte a bhí mé go mbeinnse ann. Más ann do dhá rud nach féidir iad a chur in amú, sin iad an Ghaeilge agus an Ghaylge (má cheadaítear a leithéid sin de neamhchaighdeánacht, ar aon nós).

Pop Up Gaeltacht aerach a bhí ann, ach mura rai bh sé sin léir ón ainm níl a fhios agam céard is léire ann. Ócáid mó de chuid an Chumainn Gaelaigh agus QSoc a bhí i gceist, rud úrnua agus rud a raibh a lán daoine sa dá sochaí ag súil leis le píosa. Curtha ar siúl i Seomra na Gaeilge a bhí sé. Thosaigh sé le “Gaylí” (an céilí aerach) agus ina dhi aidh sin le deochanna agus comhrá sa teach tábhairne aerach Street 66.

Ba mhór an trua é gur déanach a chuaigh mé ann, gan a bheith in ann freastal ar an nGaylí in aon chor. Is ag Street 66 a chas mé le lucht an Phop Up – áit nach raibh mé ann riamh. Agus is ait an rud é sin – sé chomh gar sin do m’árasánsa, agus mar dhuine <em>bi</em> cheapfá go mbeinn tar éis bheith uair nó dhó. Ach ní raibh, muise, go dtí teacht na Gaylteachta.

Ach pé scéal é is níos mó ná Pop Up aerach a bhí ann

domsa. Ba sheans é a bheith níos oscailte fúm féin agus faoi m’fhéiniúlacht féin, rud nach mbíonn chomh léir sin go coitianta.

Is mar sin a shiúl mé isteach agus mé gléasta go spleodrach – lán dathanna agus faoi chlúdach éadaí drithleacha. Rud nua dom sa a bhí ann, bheith amach chomh oscailte sin agus (den chuid is mó) bhí mé in ann gan mórán stró ag an nGaylteacht. Don chéad uair agus mé ag siúl amach, mhothaigh mé iomlán com pordach le mise féin a chur in iúl sa chaoi mar atá.

Bhí an oíche ní ba réchúisí ná mar a bhí mé ag súil leis – cuid de sin, mar a dúirt mé, toisc gur déanach a bhí mé. Ach is sábháilteacht agus

cinnteacht a fuair mé ann – an fáilte ciúin sin nach raibh aon dabht faoi. Agus ó labhairt le sean-chairde nó cairde nua a aithint, is spás oscailte slán a bhí ann.

An rud is mó a bhí ann ná na rudaí nach raibh ann – ceisteanna, dabht, agus stró. Gan amhras ar bith beidh mé ag baint sár-thaitneamh as Pop Up Gaeltacht ar bith, ach rud eile a bhí sa gceann sin. Bhí sé mar spás dom sa rud nua a thriail, spás le bheith oscailte agus suaimhneach, agus spás a casadh le cairde agus dao ine nua a aithin.

Ag breathnú siar air, ní raibh sé in aon chor mar a bhí mé ag súil leis. Nílim lán-chinnte céard a bhí mé ag súil leis, ach bhí mé an-sásta go deo lena raibh ann.

Agus ar deireadh thall is oíche breá Gaylach a bhí ann, agus nach deas an rud é sin!

10 | Magazine

Image via street66.bar

Siothrún Sardina Senior Editor

Siothrún Sardina Senior Editor