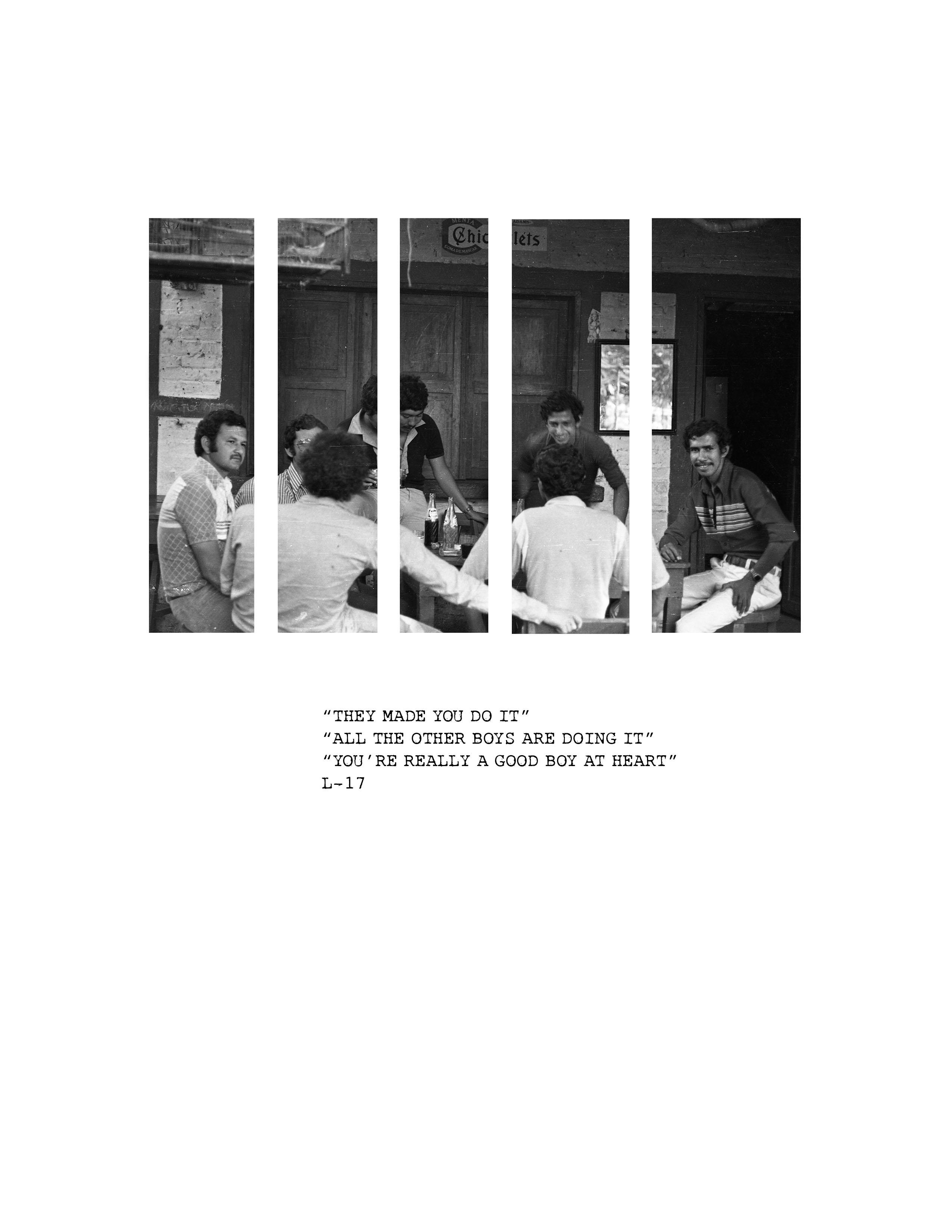

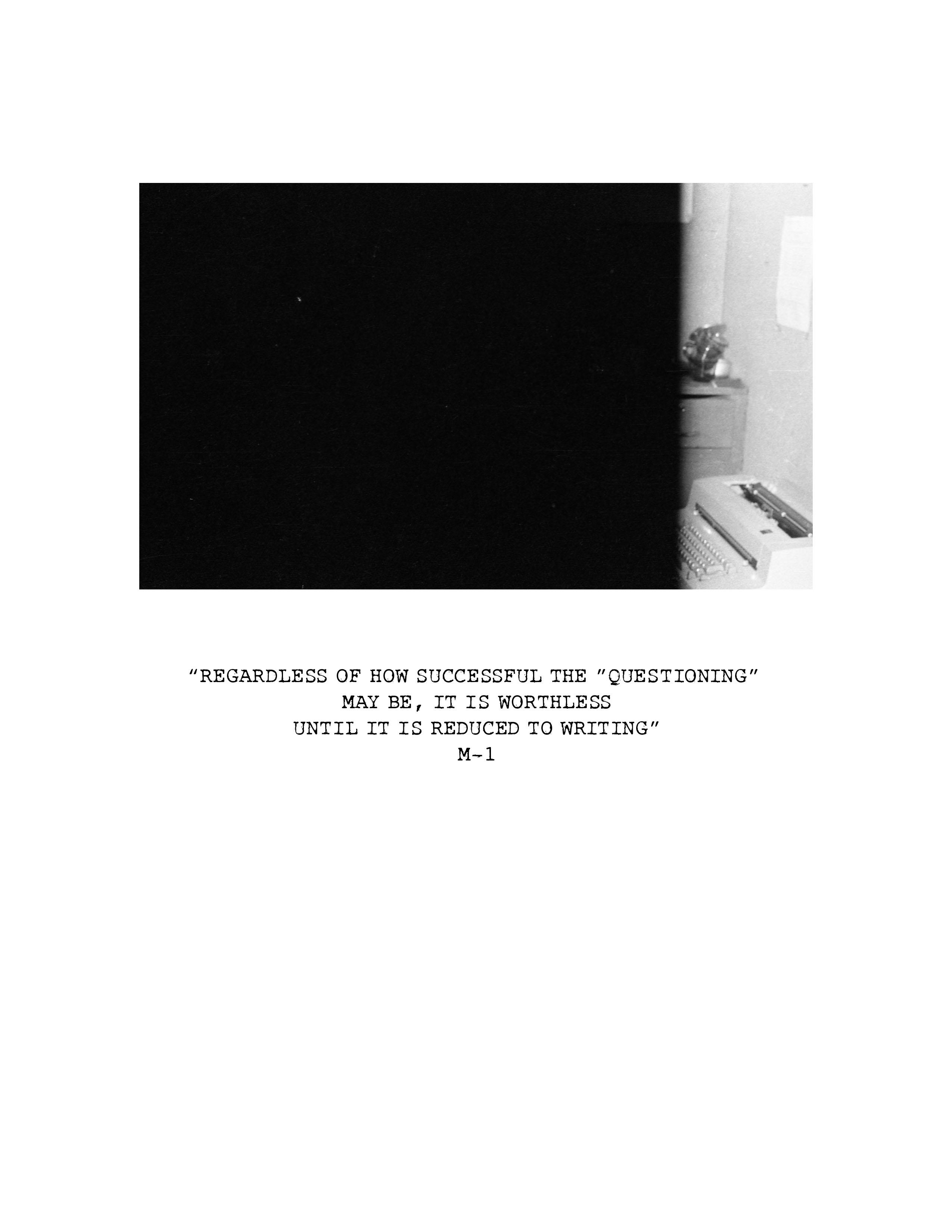

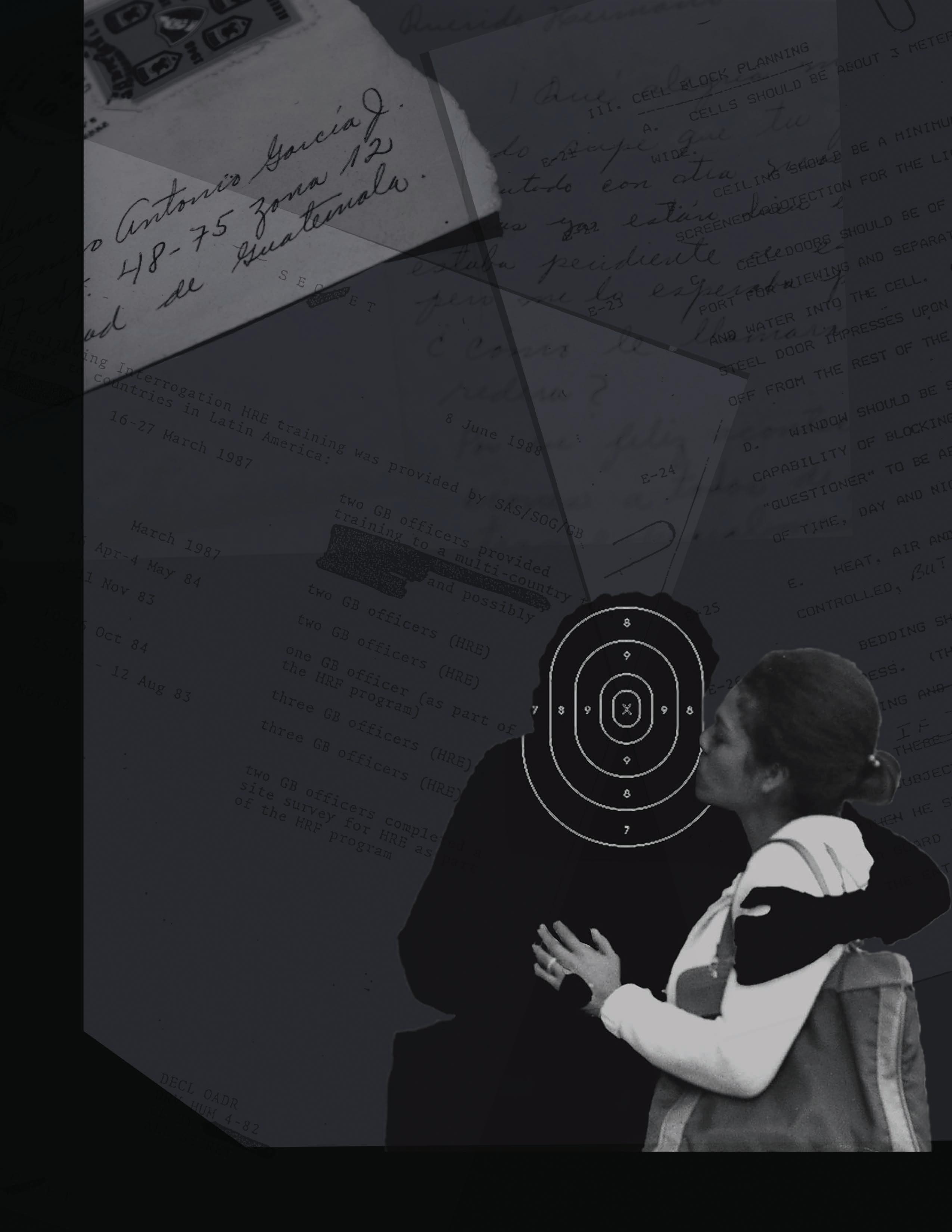

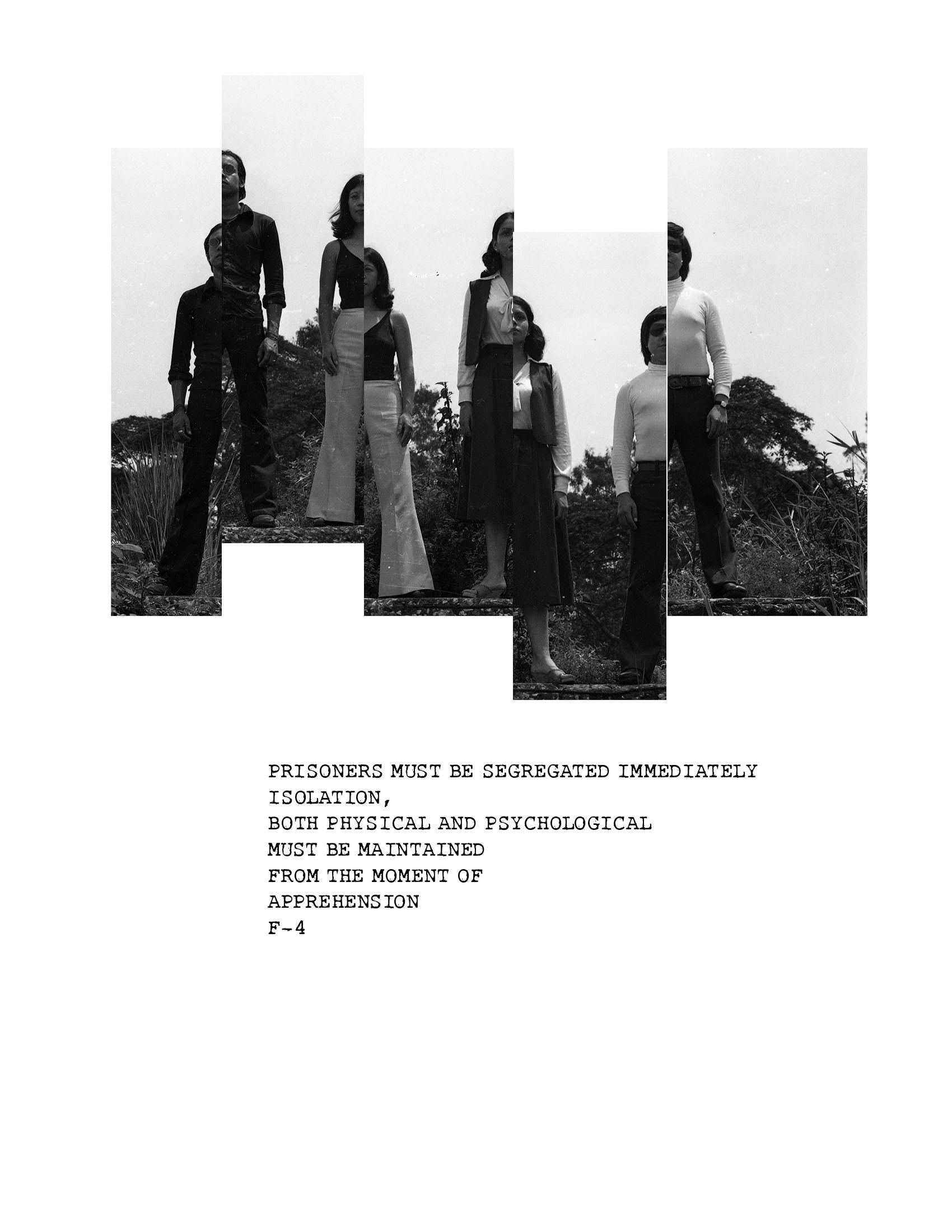

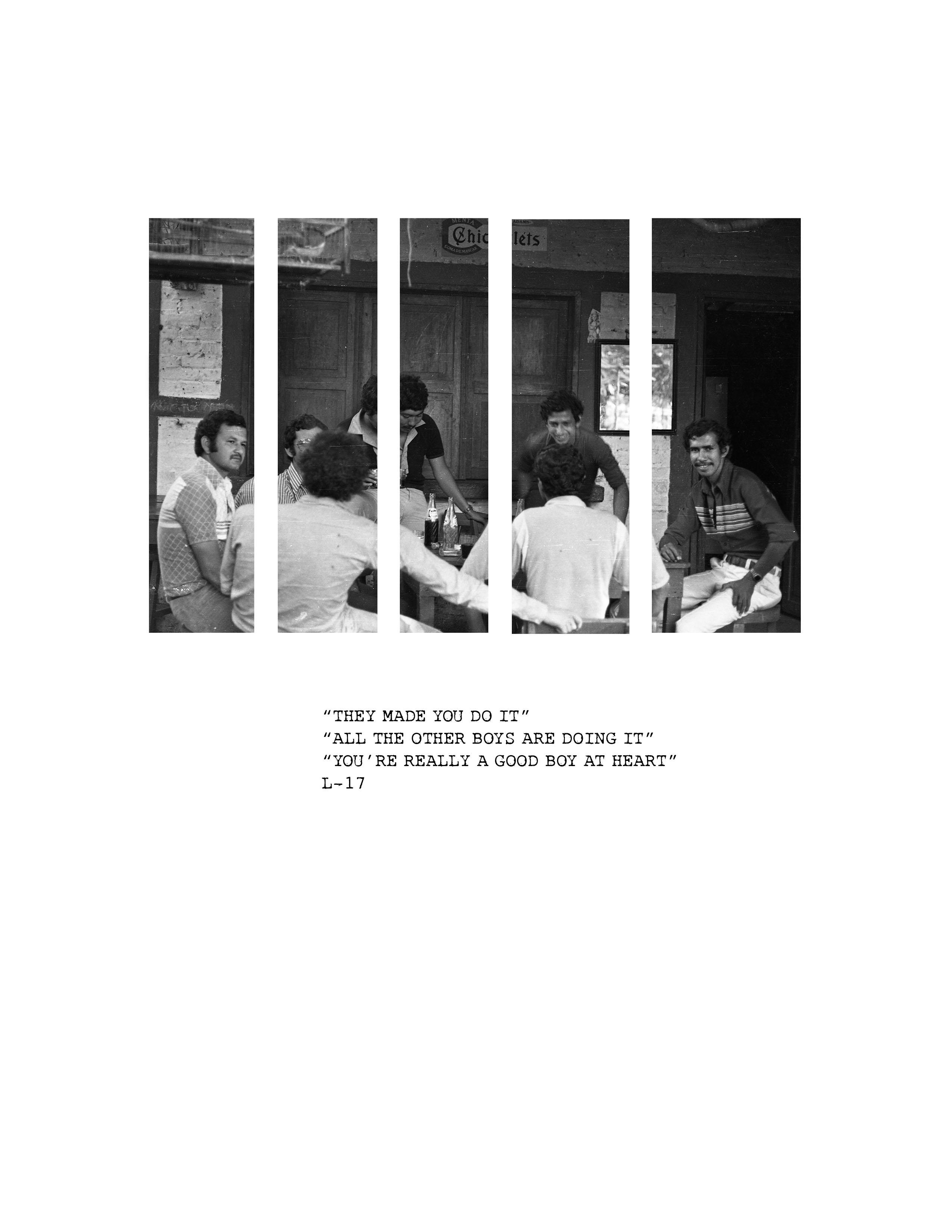

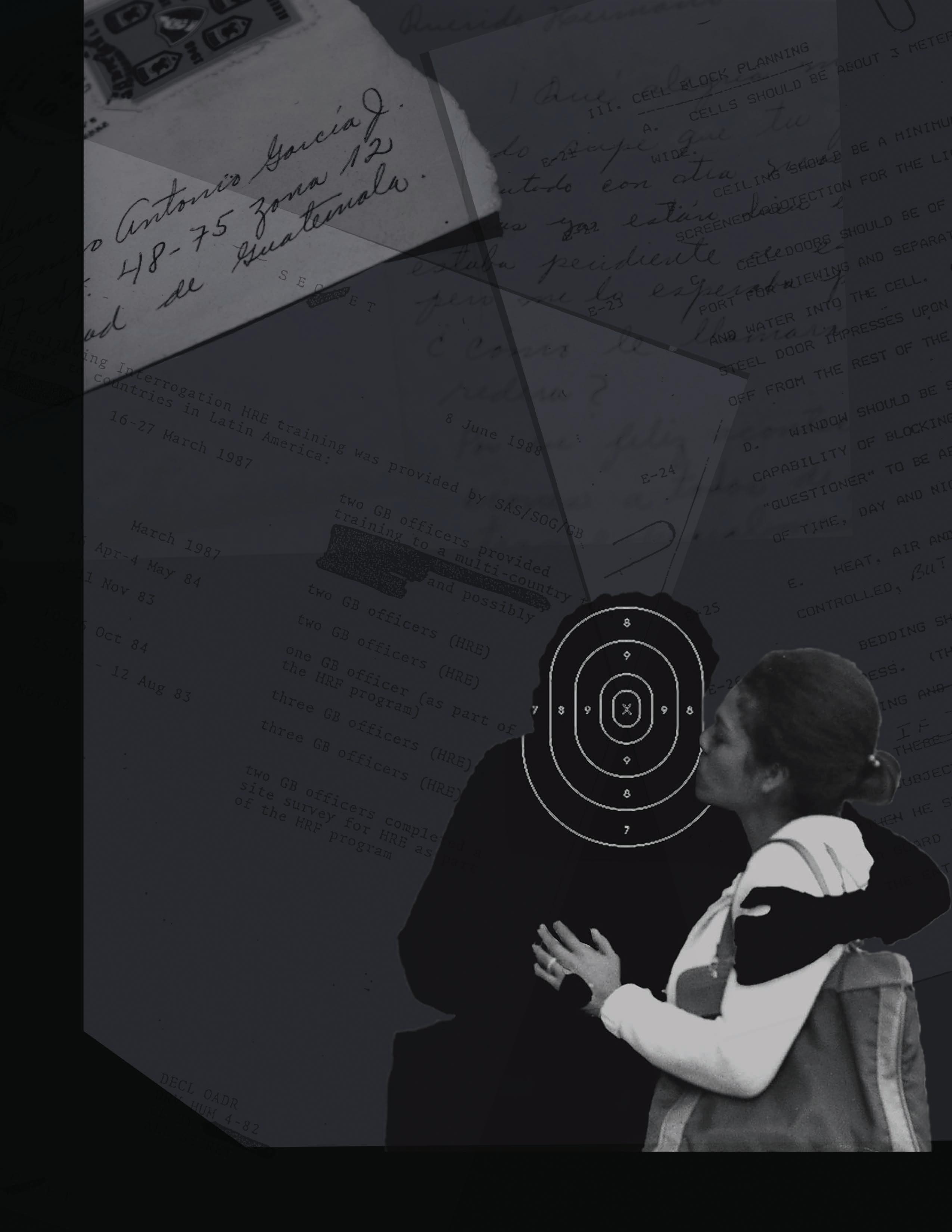

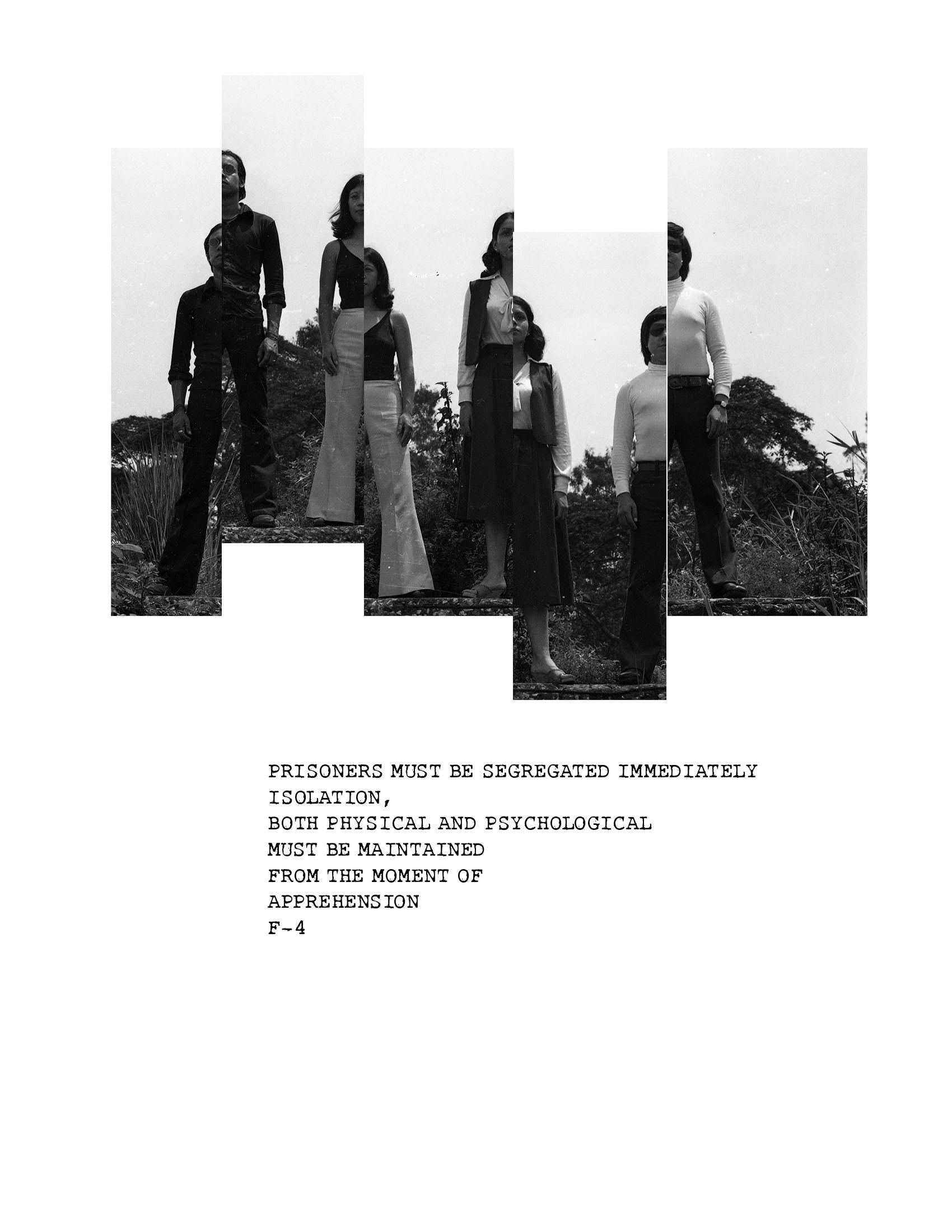

In 1980, when Elena Brokaw was four and a half months old, the Guatemalan government assassinated her father, the artist and activist Ramiro García. In Human Resource Exploitation: A Family Album, she uses the photographs and ephemera she inherited from him to illuminate the context of his death. Enlarged to a confronting scale, the photographs have been altered by Brokaw to include text from the Human Resource Exploitation Manual——a torture guide published by the CIA, the organization that trained the Guatemalan authorities who conducted the murder. By juxtaposing the evasive euphemisms of the book with the direct warmth of the photographs, she evokes the clash between violent historical events and the reality of everyday people whose lives are changed by forces beyond their control.

2

CONTENTS

5. Installation views

6. Introduction: transcript of audio reading by Elena Brokaw

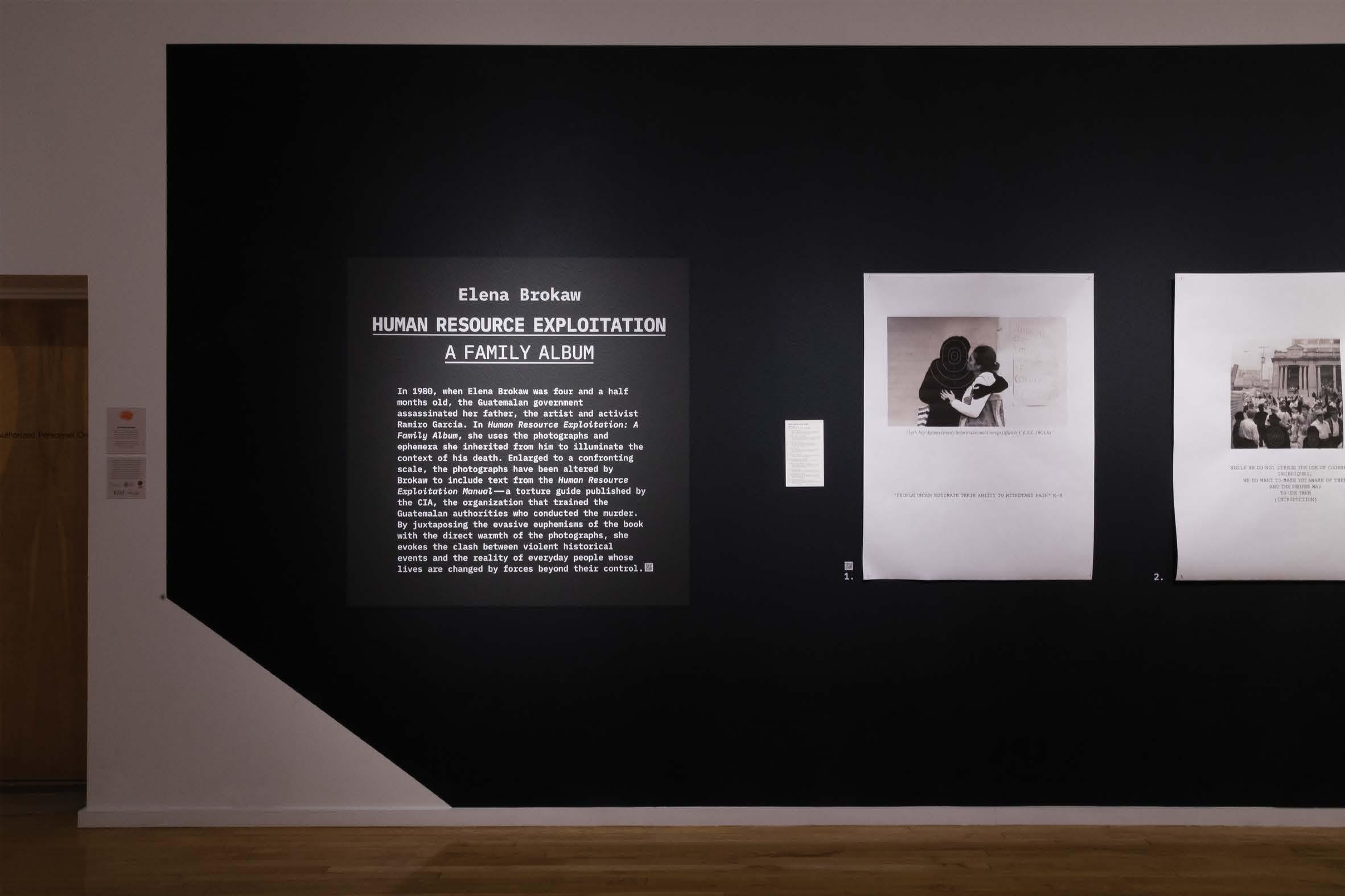

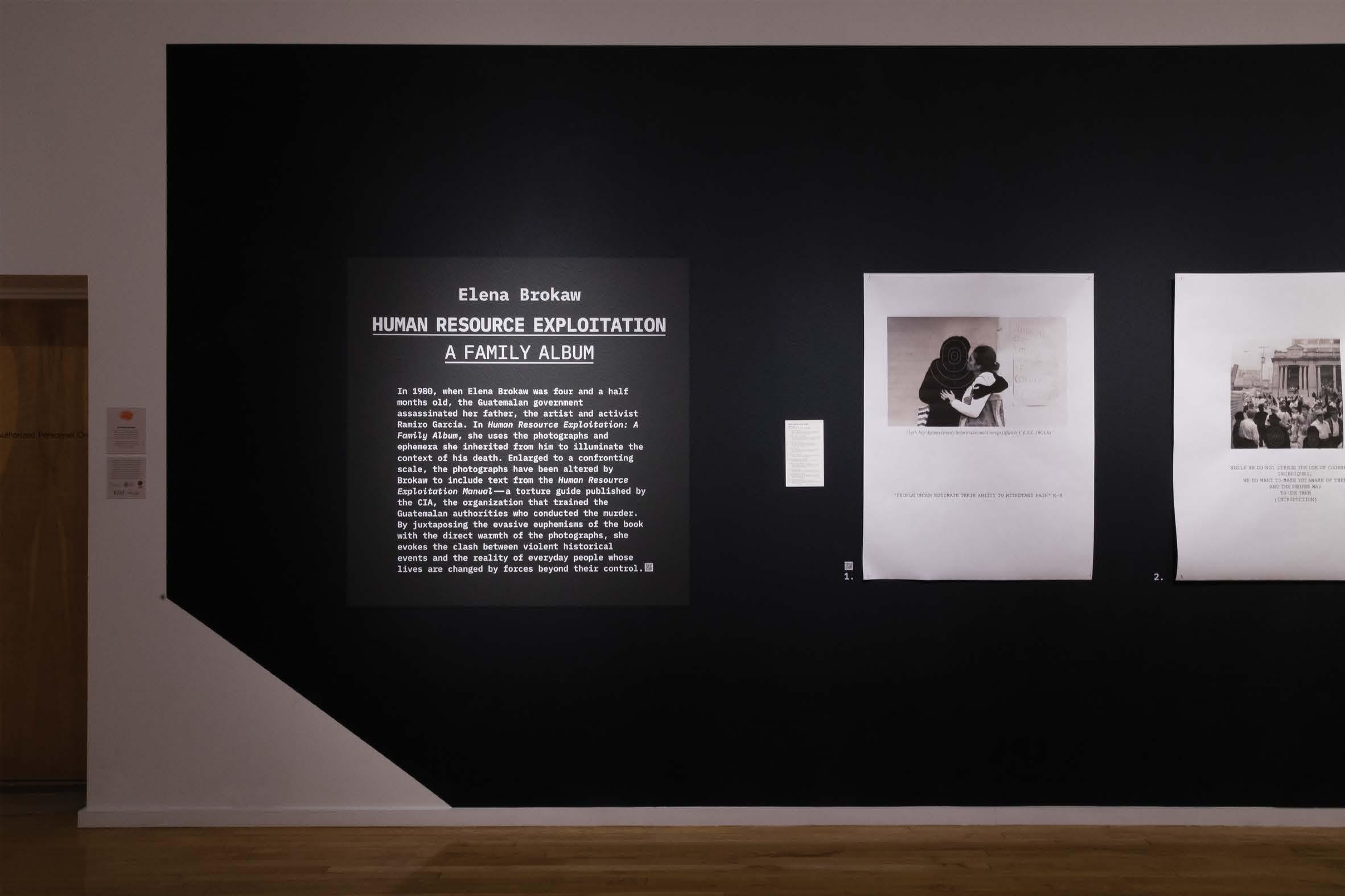

7. A Love Like Ours

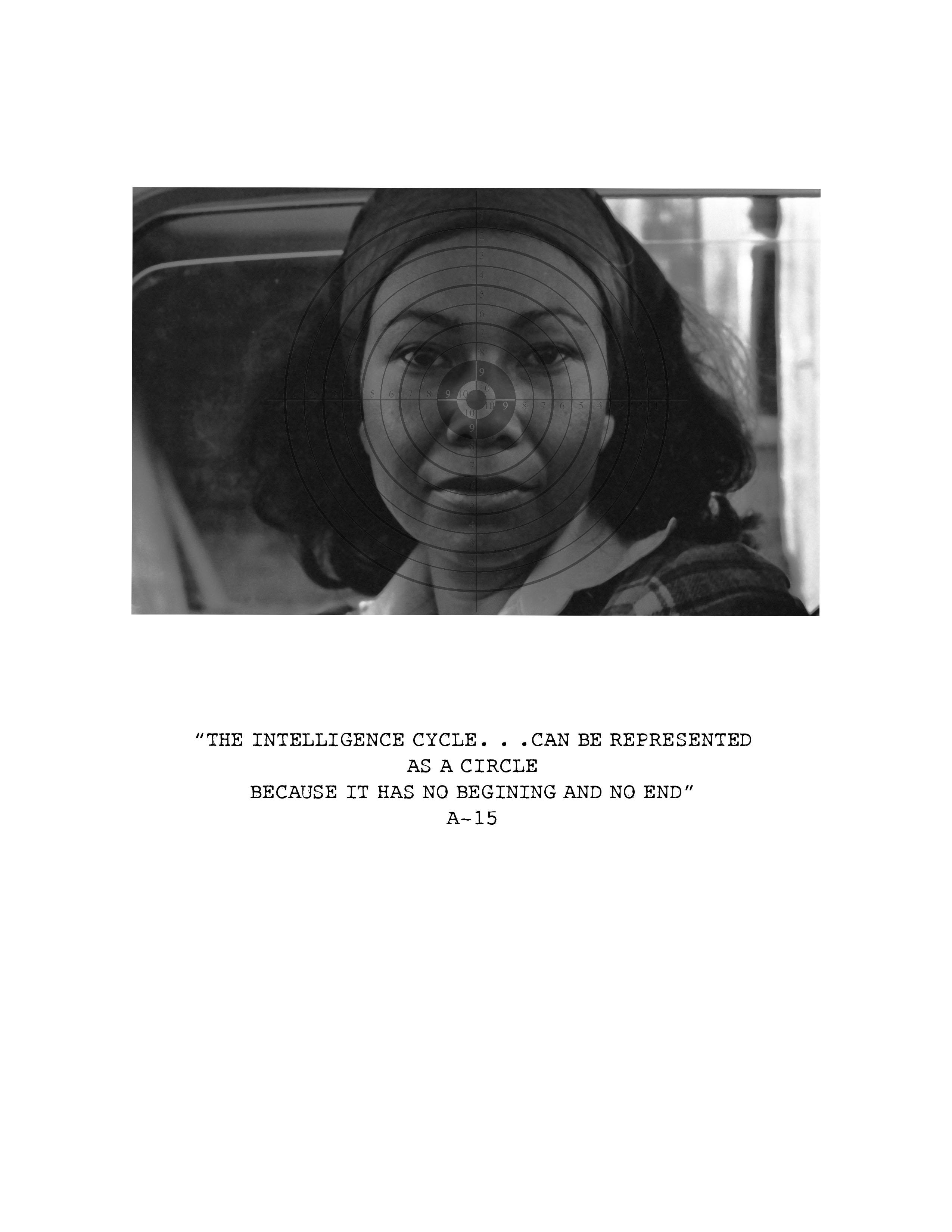

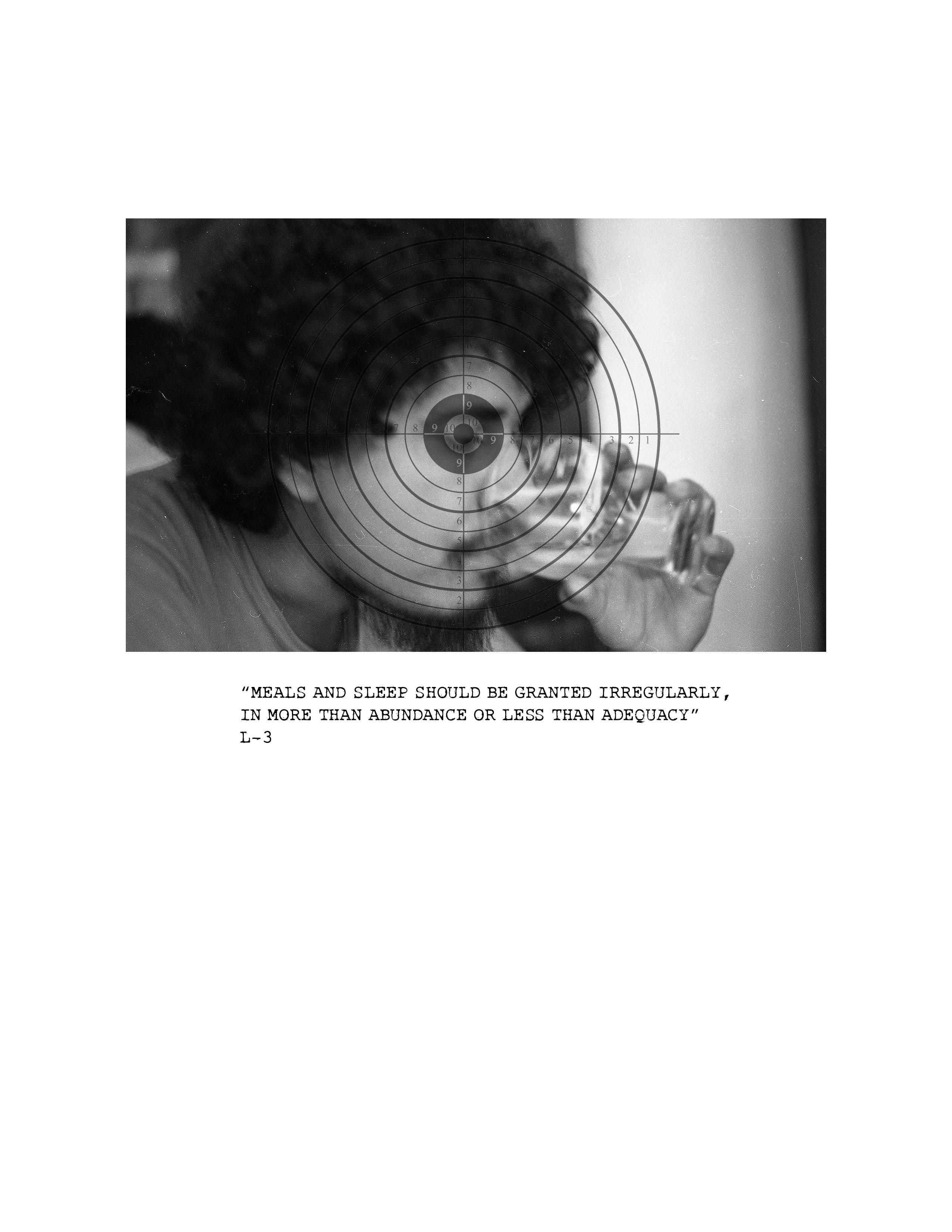

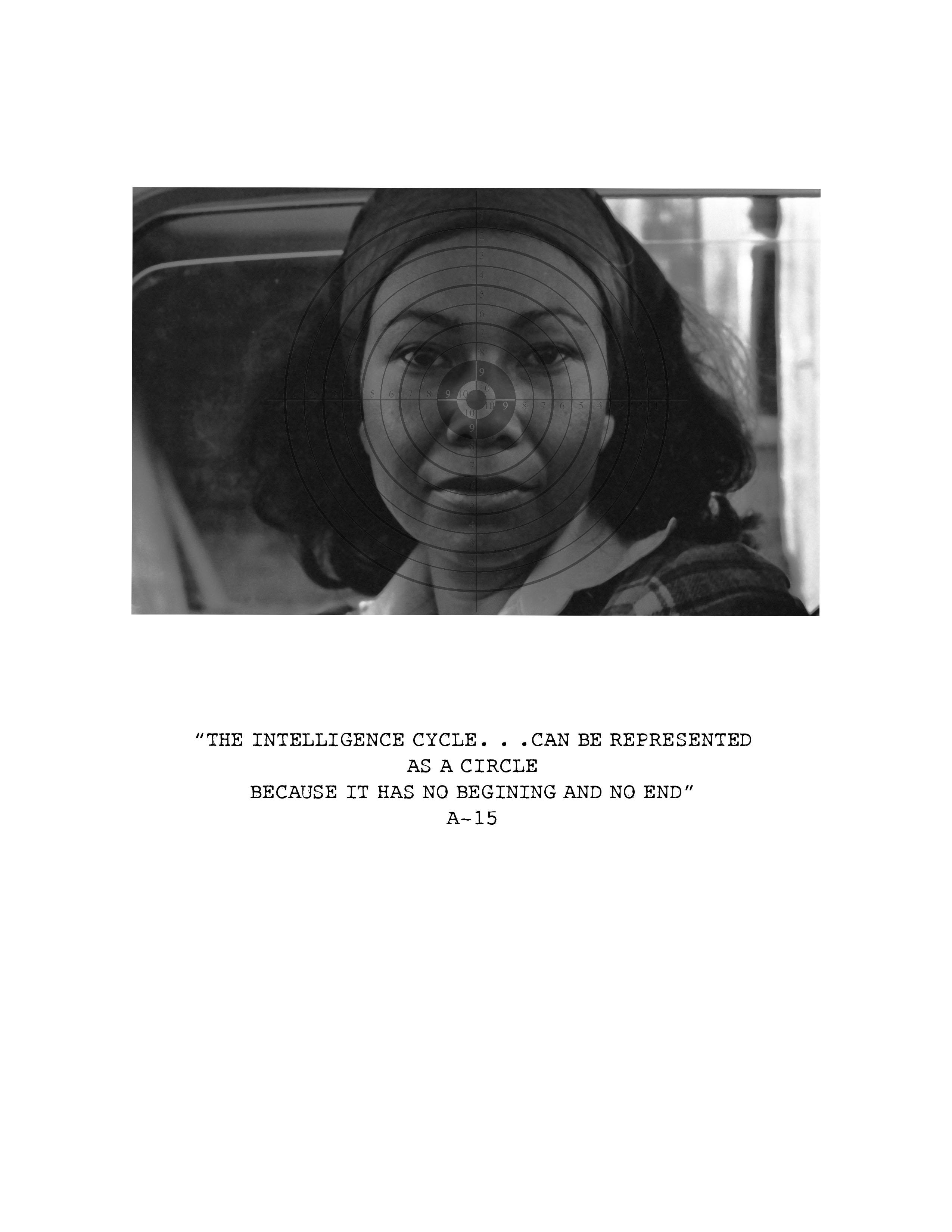

Taken at the University of San Carlos, Guatemala in 1978. The target is positioned where the fatal shot would eventually kill Ramiro García.

8. A Love Like Ours: transcript of audio reading by Elena Brokaw

9.

11. First Day of School

University of San Carlos classroom. Student activists had to constantly be on the lookout for “ears” recruited by the government to spy on their fellow classmates.

12. First Day of School: transcript of audio reading by Elena Brokaw

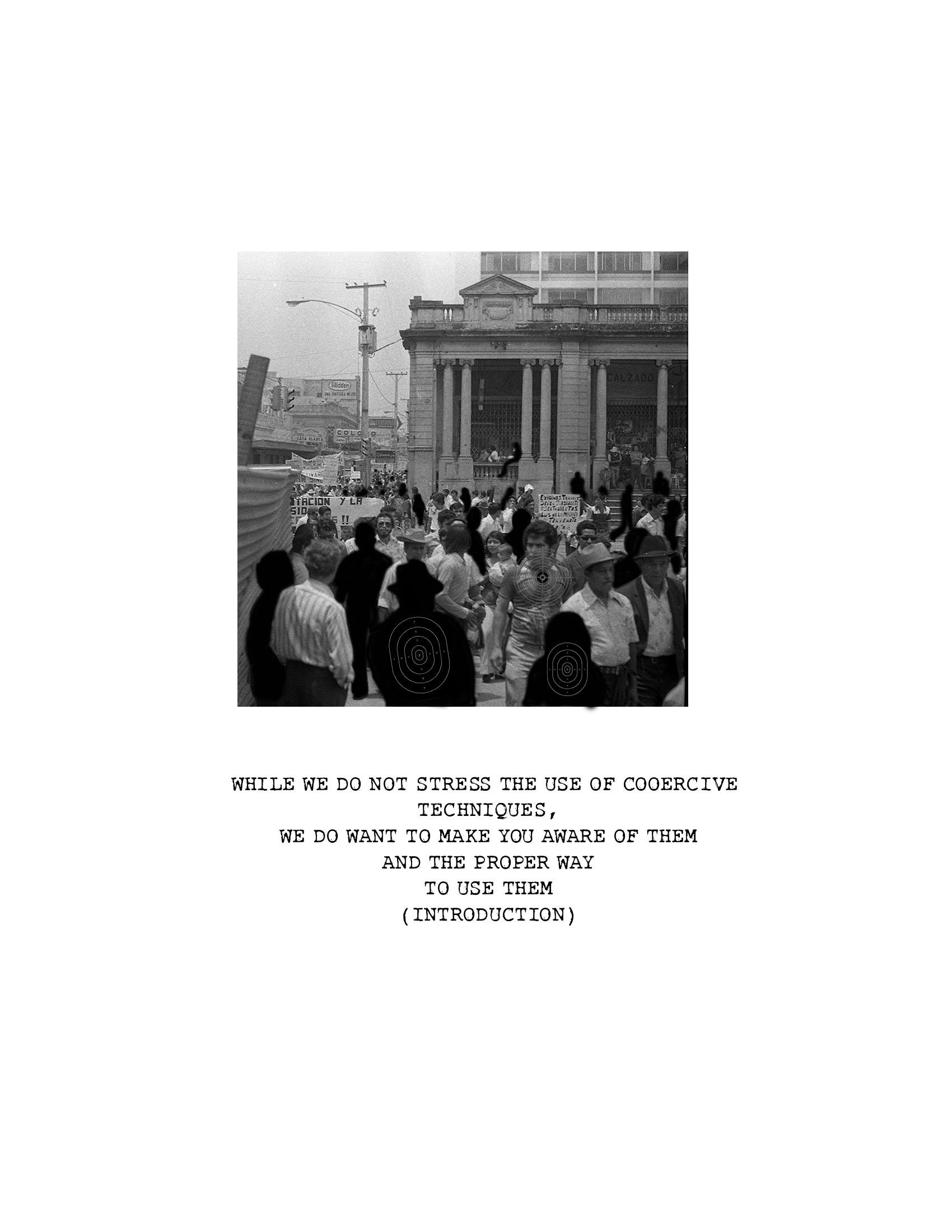

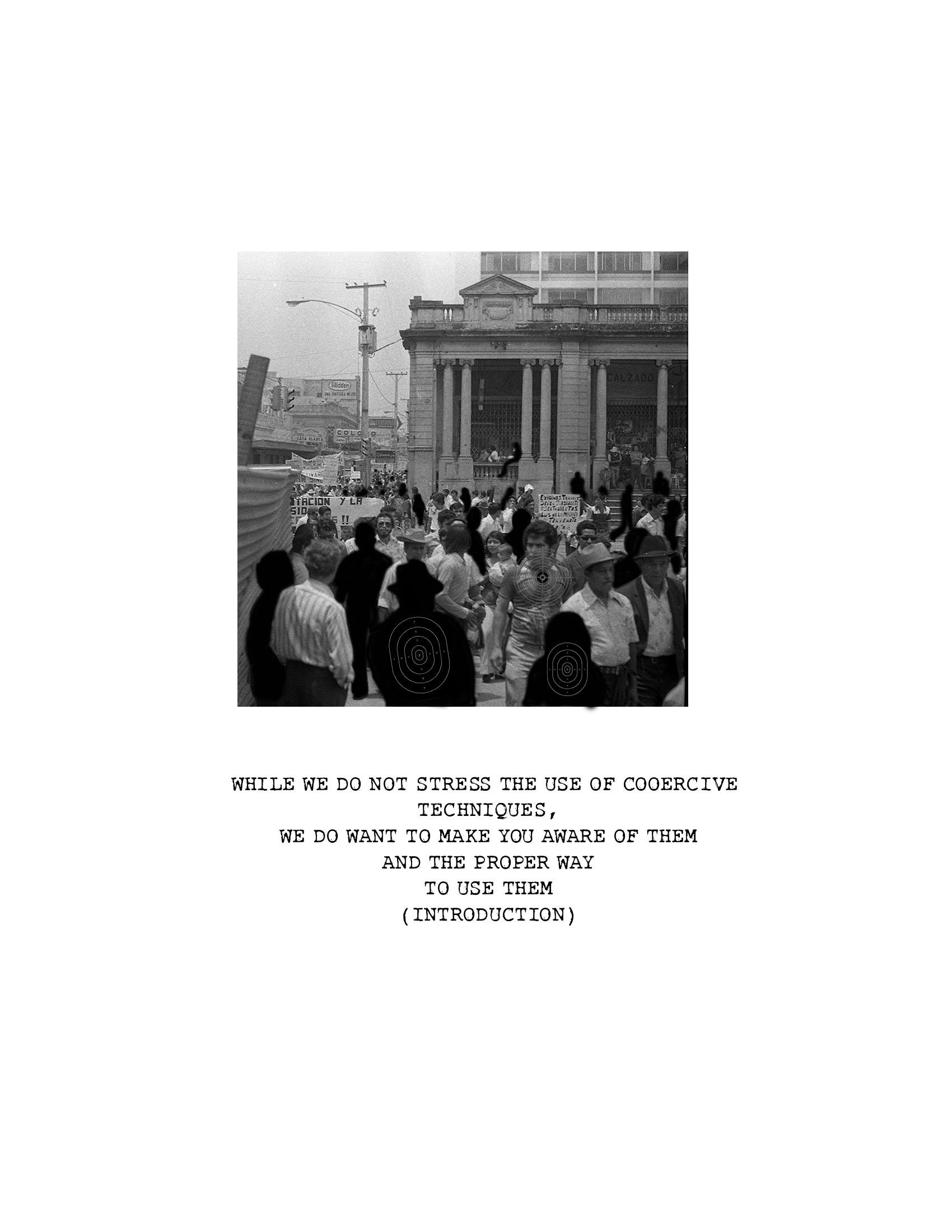

13. Class Picture

Gathering together outside of class was a dangerous activity——even if it was for coursework like these drama students.

14. Installation view (detail)

15. University newspaper which ran a commemoration to Ramiro when he was assassinated.

Photograph taken by Ramiro of a family celebration at San Rafael de las Flores, Guatemala. Souvenir wood-carved jaguar figurine, artist unknown.

"A Guatemalan Tragedy" by Thomas C. Wright, Distinguished Professor Emeritus, Department of History, UNLV

16. "A Guatemalan Tragedy"

17. Envelope from the School of Architecture at the Universidad de San Carlos sent to Ramiro containing invoices for work he did for the school.

"A Guatemalan Tragedy"

18. "A Guatemalan Tragedy"

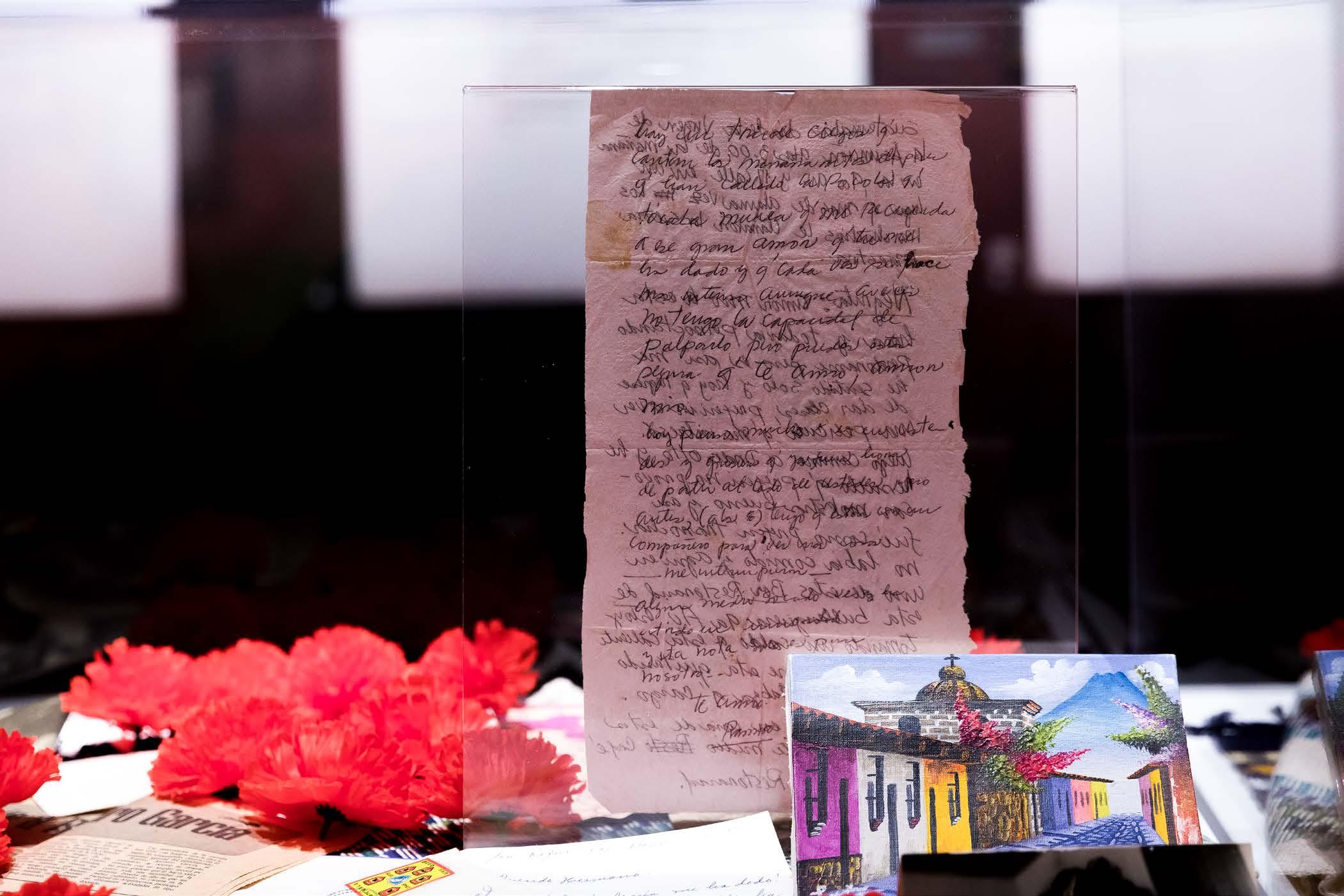

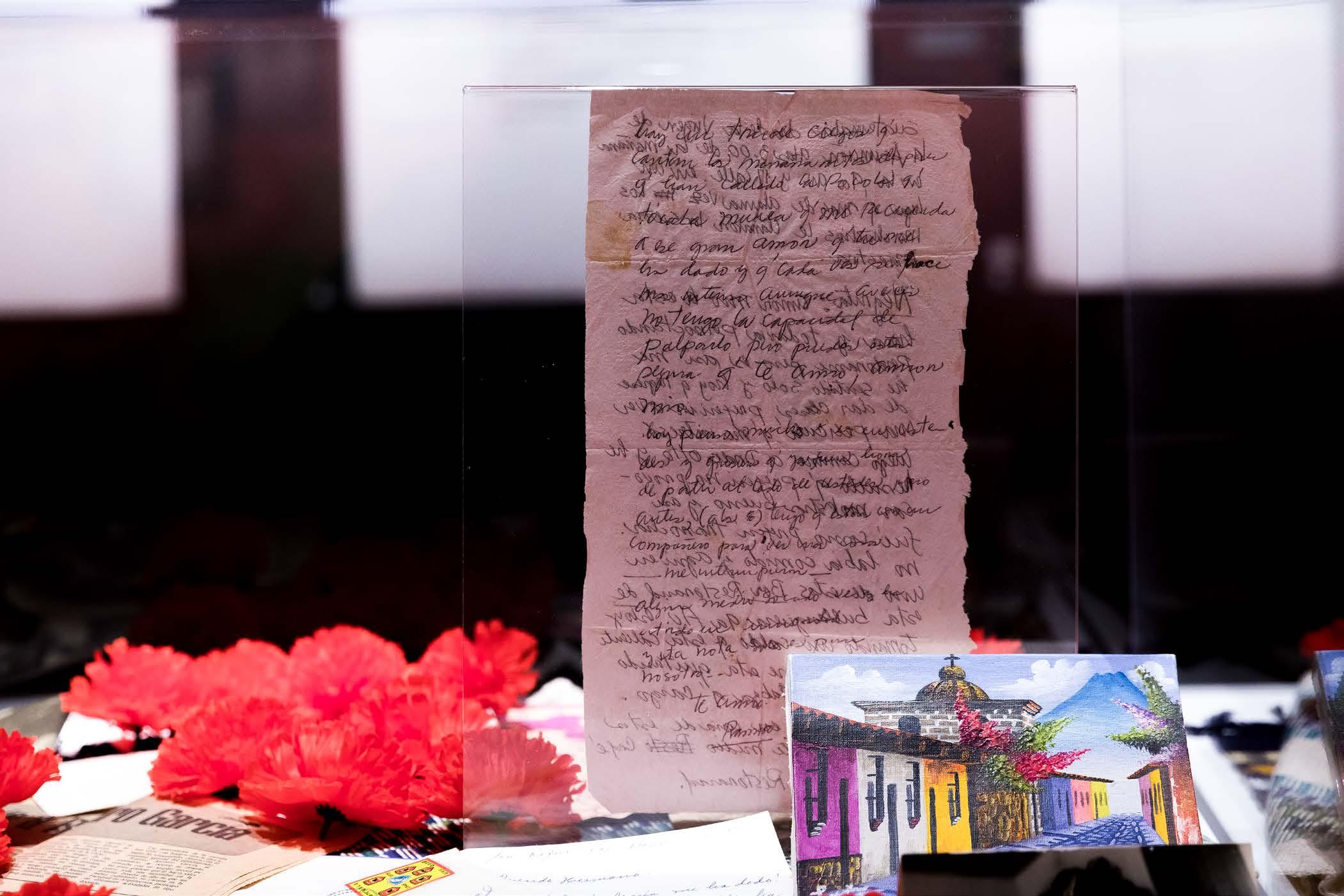

19. Letter written by Ramiro to the artist's mother

3

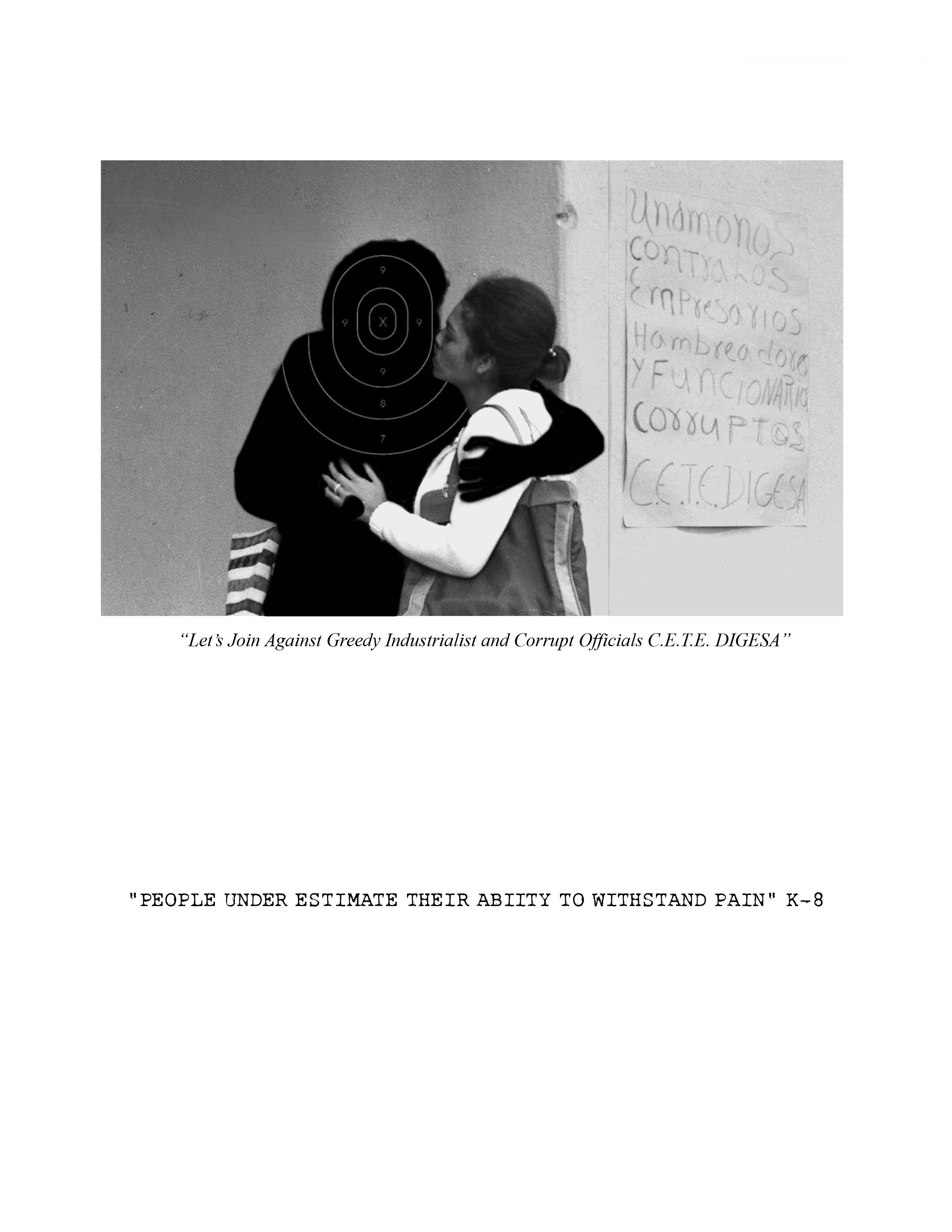

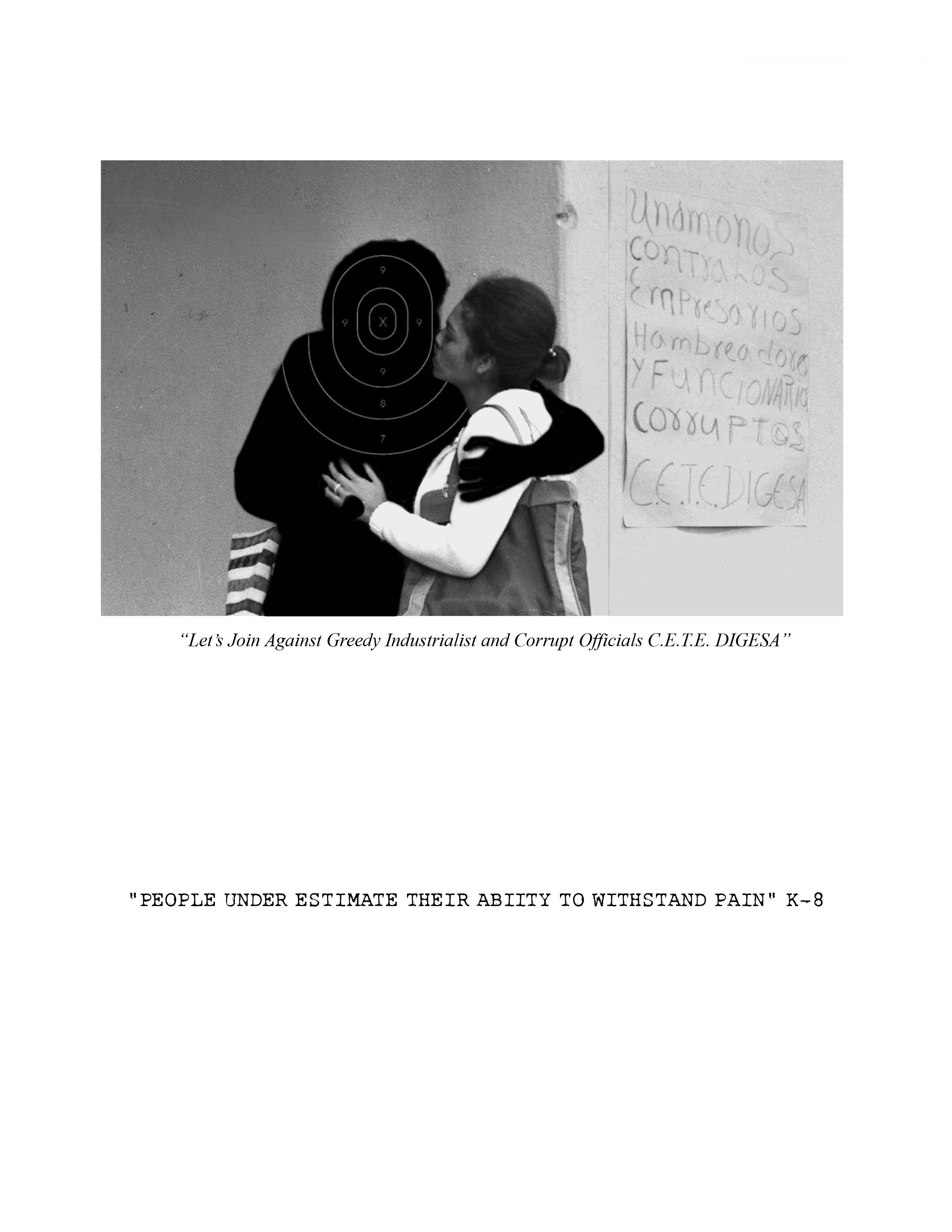

Field Trip to the Capital Taken at the Plaza de la Constitución May Day protest 1979. Thousands traveled from all over the country to protest the rights of laborers in Guatemala.

10. Photograph of Ramiro at his drafting desk taken around 1978.

Souvenir painting of a street in Antigua Guatemala, artist unknown. Antigua is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. It was the capital of Guatemala for more than 200 years until 1776 when an earthquake caused the administration to relocate to Guatemala City.

"A Guatemalan Tragedy"

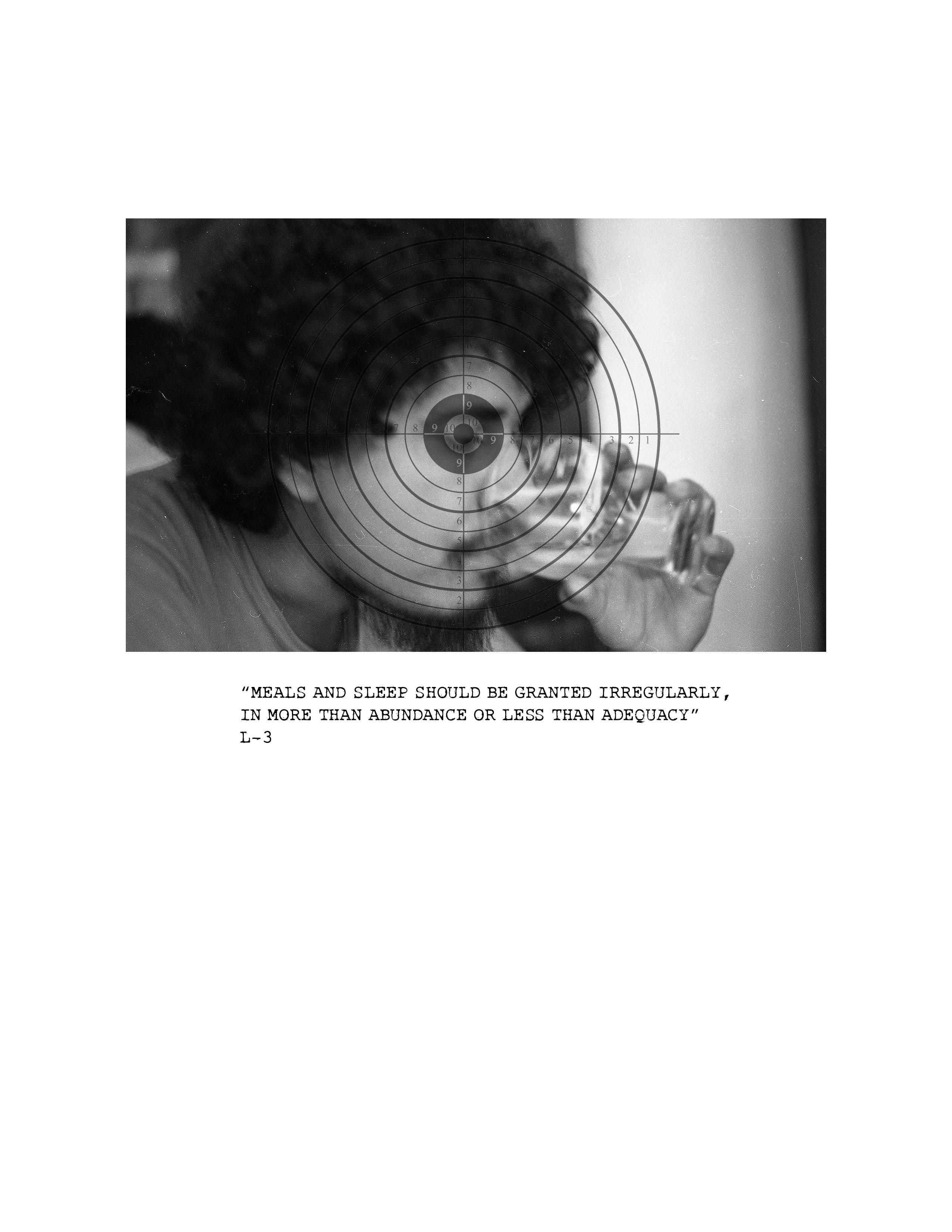

20. You Take the Cake

Access to food is an effective tool to control people, both in and out of interrogations.

21. You Take the Cake: transcript of audio reading by Elena Brokaw

22. Let’s Hear it for the Boys Childhood friends of Ramiro. One is suspected of playing a role in his betrayal.

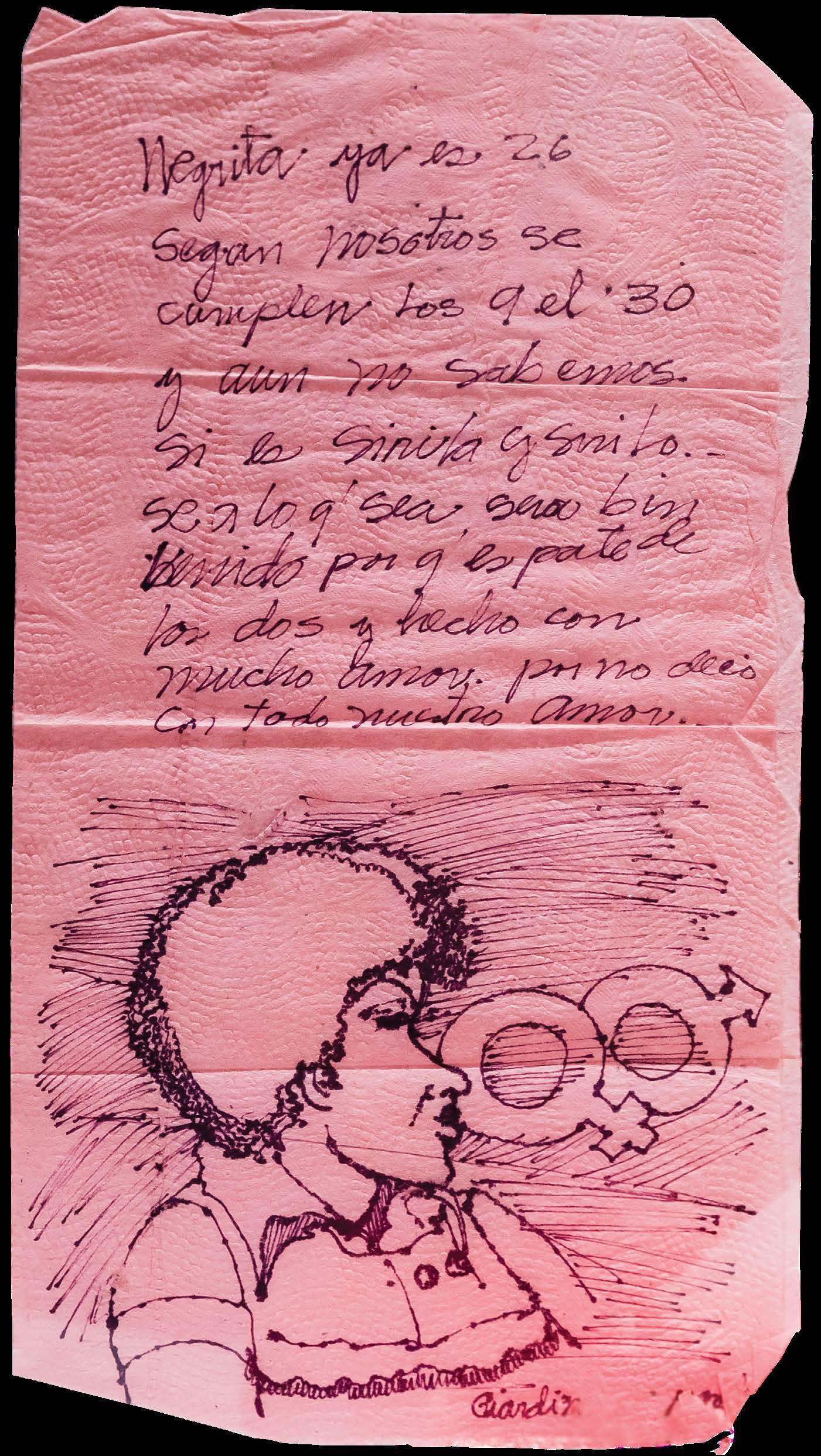

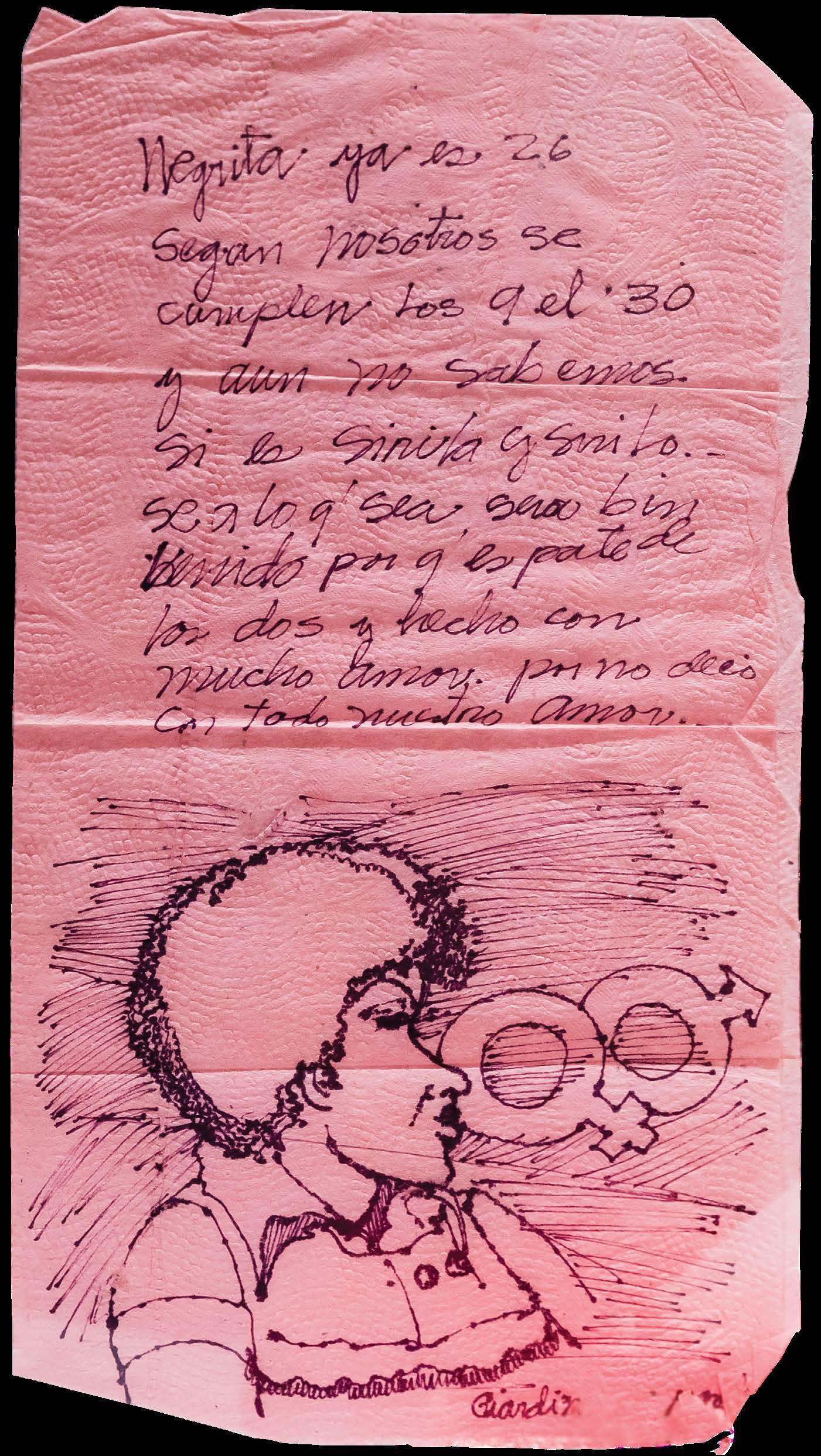

23. Letter and sketch from Ramiro to the artist’s mother.

24. These Are the Moments I Live For

The CIA handbook presents interrogation as an equal playing field. Clearly ignoring the fact that one person is being held captive.

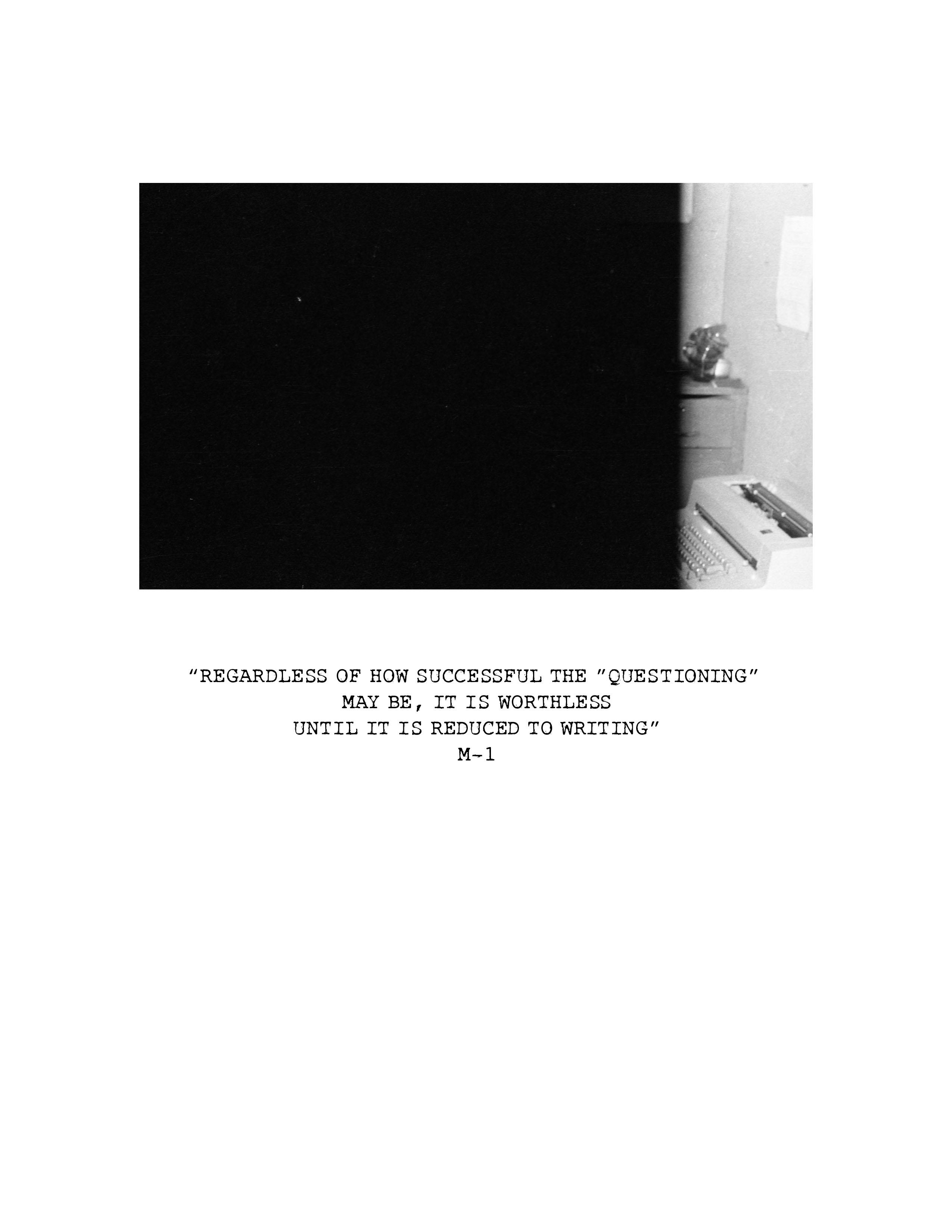

25. Life Unscripted

The armed conflict in Guatemala generated millions of documents that cataloged the suffering of thousands.

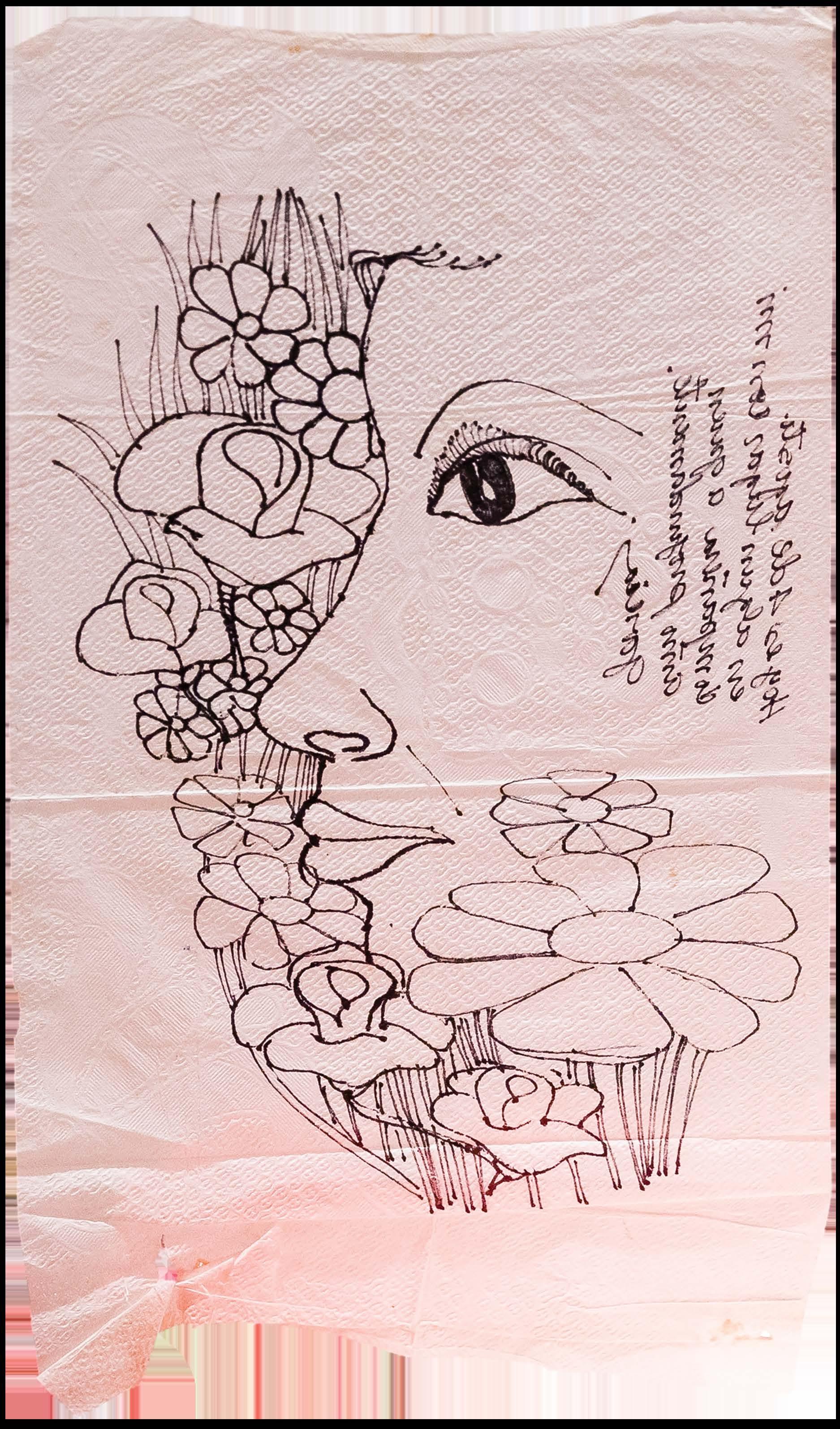

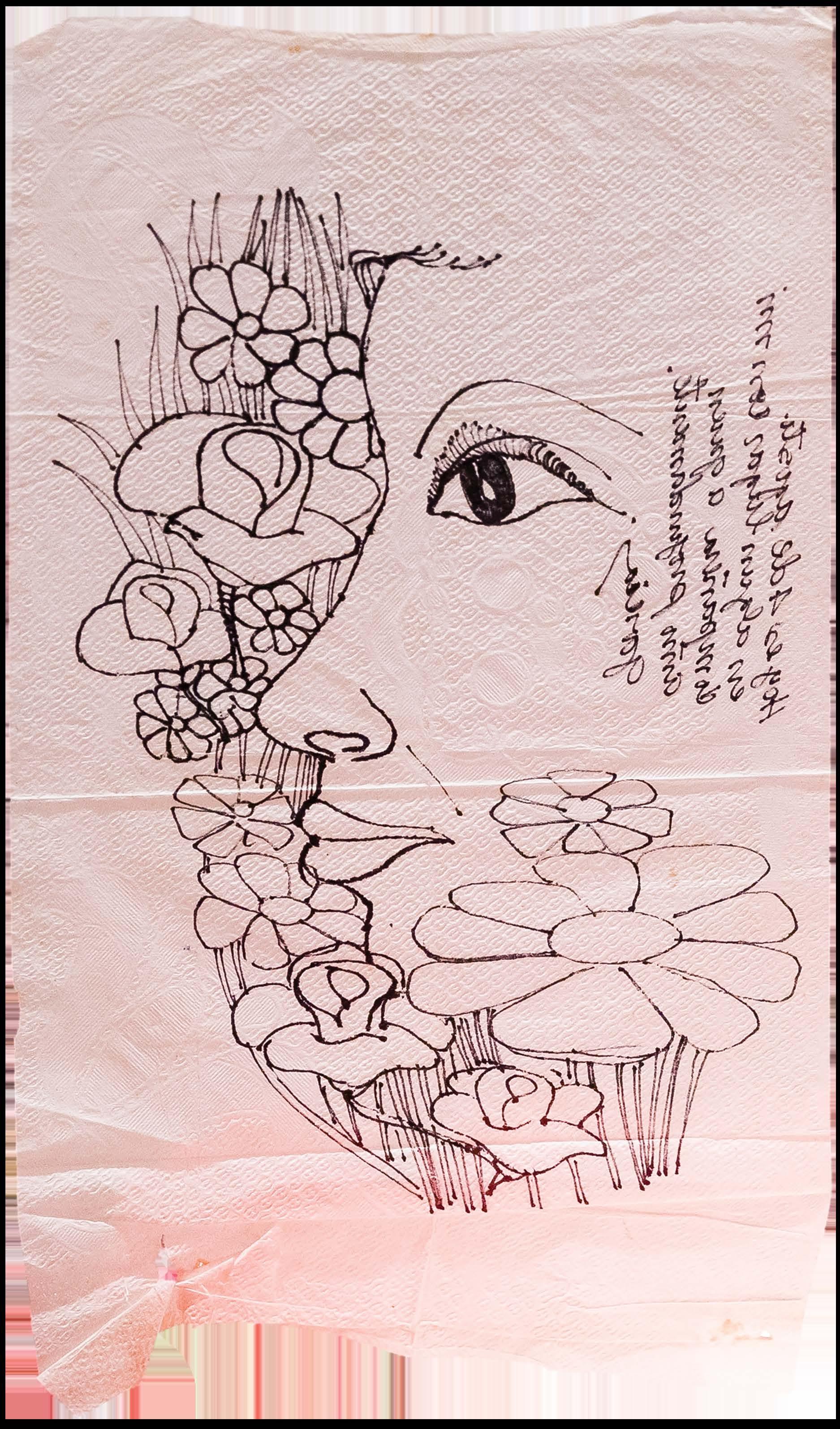

26. Sketch drawing of artist’s mother by Ramiro on a napkin.

27. Just Between You and Me

Torture victims were presented with a new reality where the only person they were told they could trust was their interrogator.

28–29. Just Between You and Me: transcript of audio reading by Elena Brokaw

30. Families are Forever

Every name given by torture victims generated another entry in the death squad entries——continuing the cycle of abuse.

31. Installation view (detail: Human Resource Exploitation Manual)

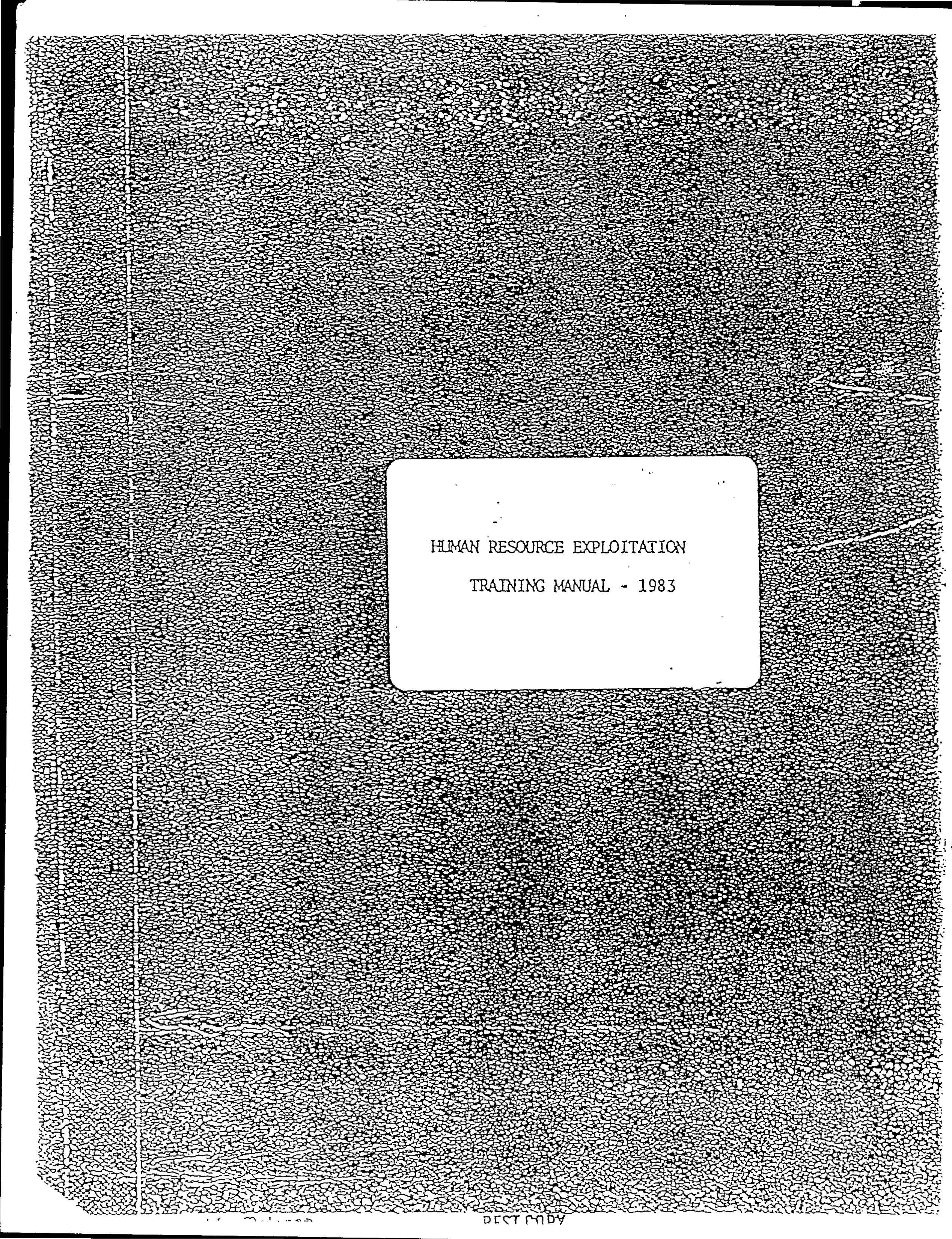

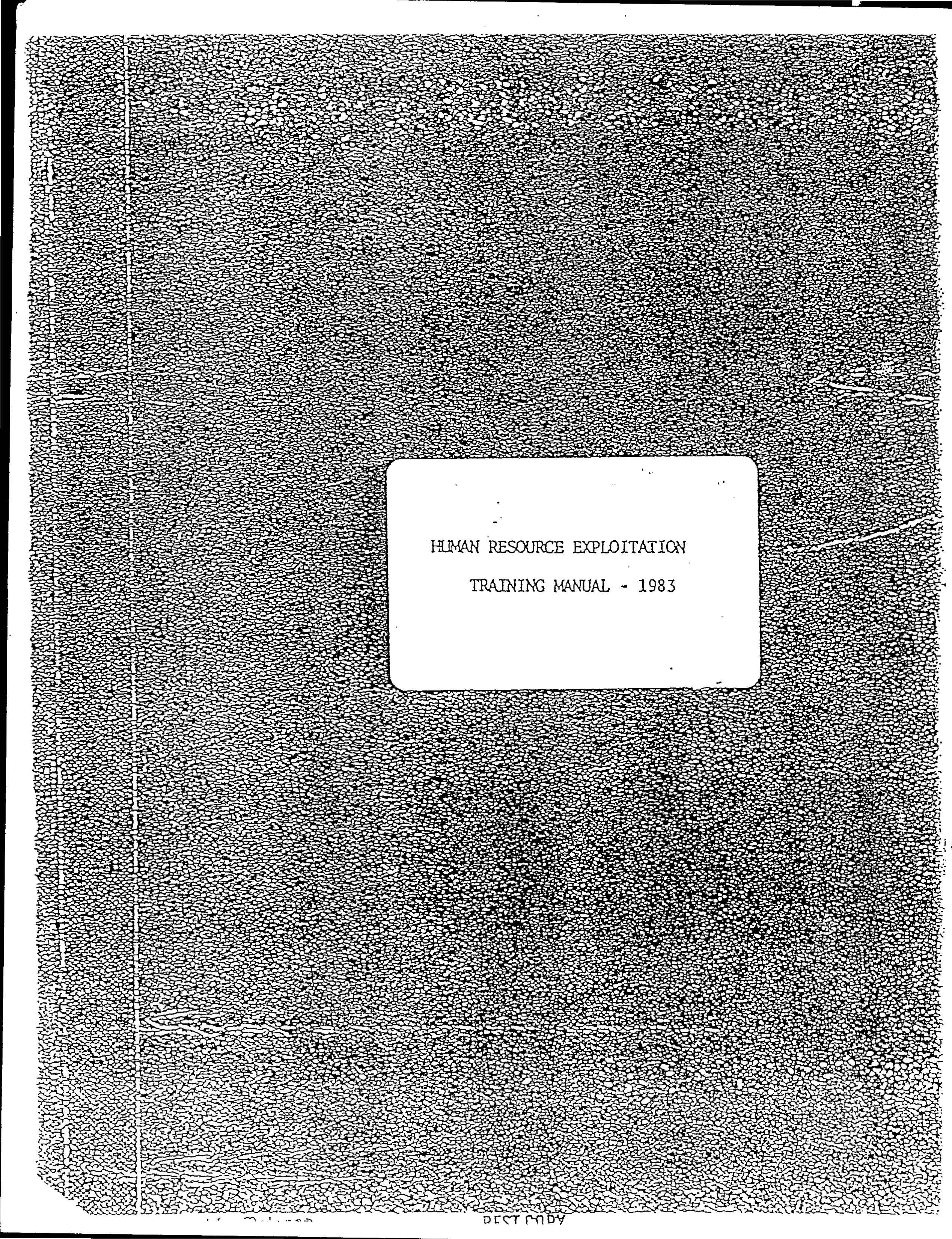

32. Cover of the Human Resource Exploitation Training Manual — 1983

33. Ramiro García's biography

34. Elena Brokaw's biography

35. Acknowledgments, notes, and photography credits

36. Audio files and additional reading

37. About Marjorie Barrick Museum of Art

4

5

AUDIO TRANSCRIPT: INTRODUCTION VOICE OF ELENA BROKAW

In the spring of 2020, while the world was just starting to realize the challenges of COVID-19 and was experiencing a reckoning of racial injustices, I spent every spare moment digitizing 1,079 negativos de mi papá, photography which he originally took in 1978-1980. The repetitive motions of putting on gloves, cleaning negatives, loading trays, listening to the hum, and adjusting files was a healing ritual that helped me stay centered amid all the anxious uncertainty of that spring.

Through the process I attempted to look at Guatemala through the eyes of my father. I was not surprised to find photos of desfiles, demonstrations, y juntas. I knew, after all, that he was assassinated because of his political beliefs and membership in organizations como el Ejército Guerrillero de los Pobres. What I was surprised by was the delicate details in the photos and the way that everyday life captivated him as much as la revolución. He focused on the beauty of the moment. Sometimes that beauty was in the stern look of mi abuelita, other times it was in the gathering of workers to protest the illegal activities of the rich in Guatemala, and most often it was in the scenes of everyday life he got the chance to enjoy with his friends and family. It was as if he was taking me on a tour four decades after the fact. Agarrando mi mano y enseñando todo que pudo. The quiet moments spent with him at my computer screen are times I will treasure because I finally started to feel that his shadow was taking form and becoming a figure I recognized.

Las fotografias themselves have become entry points to start conversations with familia desde mi papá. Who he was and what they remember about him. Looking at images of the past seems to be something primal in each of us. Dating all the way back to the first time

one of our ancestors decided to commemorate a buffalo hunt by replicating the event en la pared de una cueva. Images seem to provide safety for memories to become solid. They transform feelings into details and help bring las emociones de tiempos increíbles.

One such event happened when I showed mi mamá a few images from the day I was born. She of course began to tell me the story I had heard of my birth since I was a niña but this time she told historias nuevas. Like the months we had spent in hiding when I was a newborn.

I first came across the Human Resource Exploitation manual as a result of wanting to know more about el terror that I heard in her voice when she talked about the months in hiding. The manual was a teaching tool used in the School of the Americas—a United States Army Center—to teach Latin American military personnel how to deal with insurgents when they are detained. In other words, how to torture people. When I read the copies of this book, I was shocked at how institutional language was being used to mask torture. The subjects of the detainment weren’t referenced as humans. They were bodies meant to be broken into submission. A clear subtext of inhumanity emerged between the typeface and marginal notes. These were not people; they were bodies meant to be used and discarded.

While I read, I couldn’t help but think how many of los compañerxs de mi papá endured torture. If any of the people in my father’s pictures endured the procedures outlined in those pages. It seemed to me that las fotografias and the manual were having their own conversation that needed to be captured and experienced to understand es terror de ese tiempo. In the following images you will get to see that conversation and hopefully experience some of the abjection of placing loved ones within the context of terror.

6

7

AUDIO READING BY ELENA BROKAW

A Love Like Ours

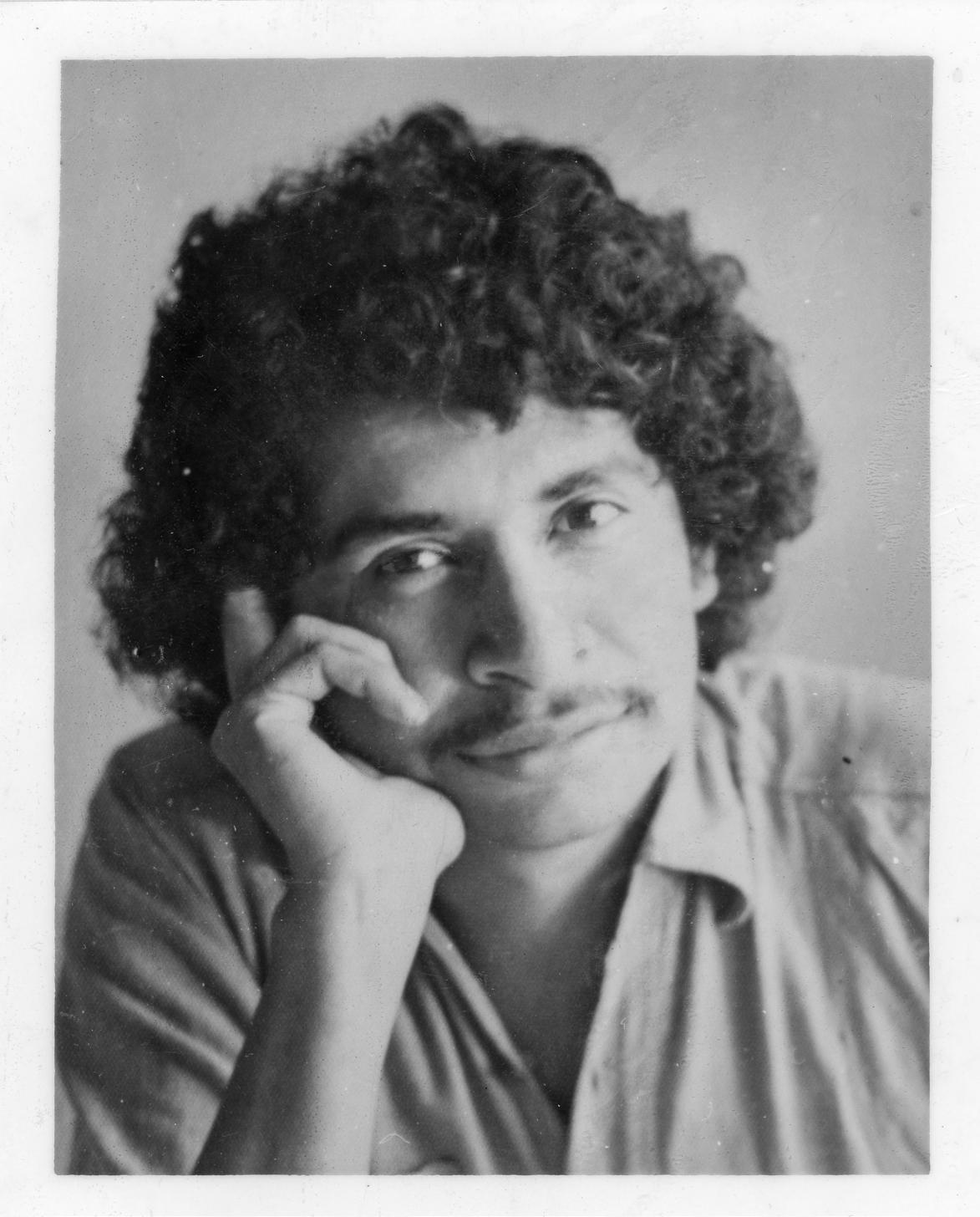

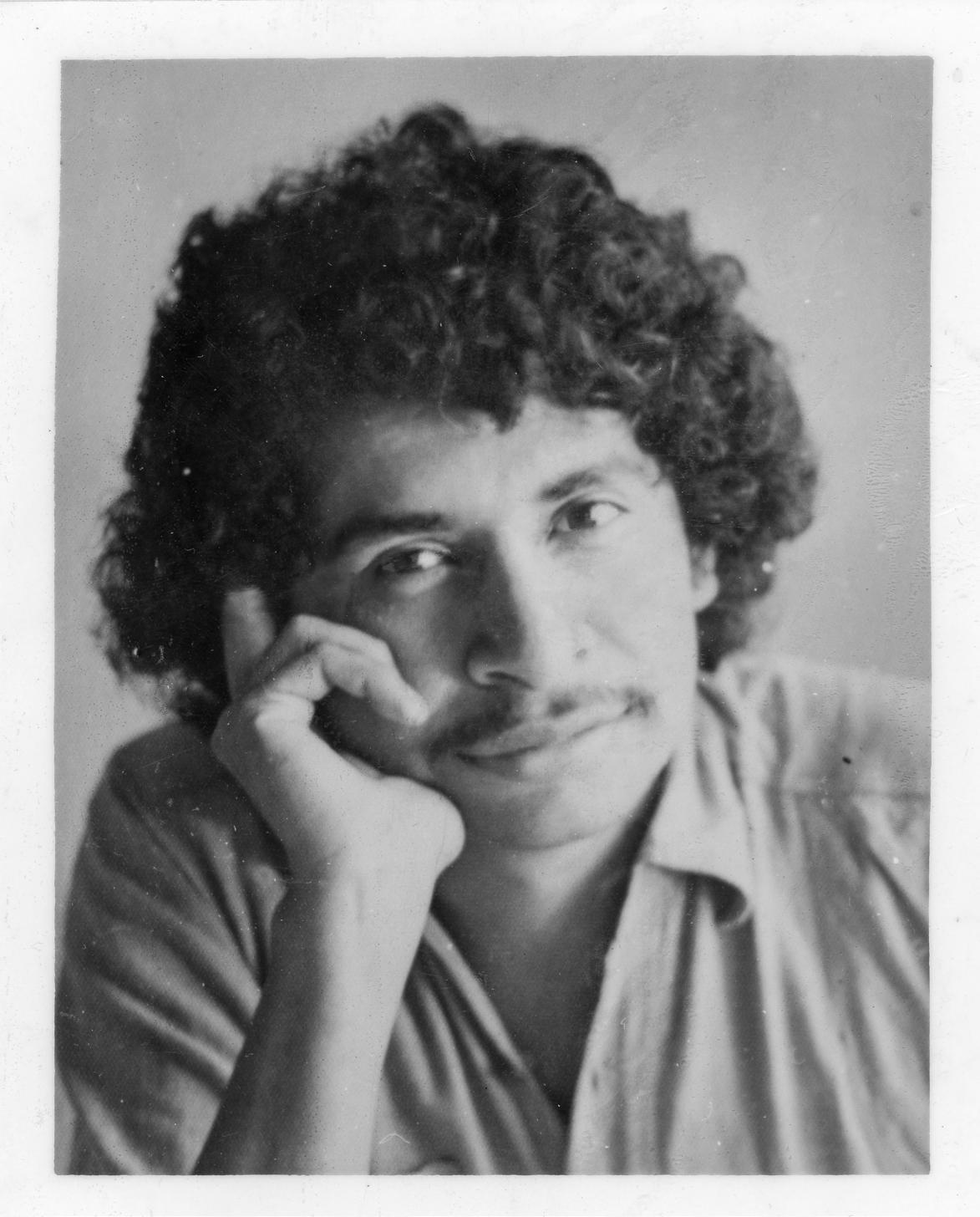

Taken at the University of San Carlos, Guatemala in 1978. The target is positioned where the fatal shot would eventually kill Ramiro García.

The blacked-out figure in this image es mi papá— Ramiro Antonio García Jiménez. He was shot in the head by military personnel in plain clothes around 7:00 pm on September 15, 1980 in the small pueblo of Asunción Mita—his home town. The assassins have never been brought to trial. Here he is kissing my mother who is pregnant with my older sister. Mi mamá is using her tote bag to hide her bump from the camera because it wasn’t common knowledge yet that they were expecting. They had already started to wear wedding rings as a show of commitment to one another even though my father wouldn’t live long enough to make their relationship official in the eyes of the law—of course you can only see hers because he has been taken away. This quiet moment happened en la Universidad de San Carlos next to a poster urging students to join in the fight against the corruption in Guatemala. The armed conflict didn’t end the amor o felicidad de ese tiempo; it just made it more complicated.

The manual begins with the advice to wouldbe interrogators that people will understate their ability to withstand pain. What it doesn’t tell you is that there is more than one way to feel and inflict pain. Some of the results of torture are visible while others are not.

8

9

11

AUDIO READING BY ELENA BROKAW

First Day of School

University of San Carlos classroom. Student activists had to constantly be on the lookout for “ears” recruited by the government to spy on their fellow classmates.

They were called “orejas” those that would listen in and report back to the police or military what they heard en la Universidad. La Universidad de San Carlos is the fourth oldest university in the Western Hemisphere and was a center of political activity during the armed conflict. Anyone associated with the university was automatically under suspicion of being an enemy of the state. The university was granted autonomy from the government in the 1944 Constitution which meant that theoretically the government couldn’t interfere with the daily operation of the school. This meant that groups of protest could meet on campus with relative security but autonomy only went so far, as students and faculty were often reminded by the assassinations that happened just outside the university’s borders and the tortured bodies that were left at the entrances.

12

13

A GUATEMALAN TRAGEDY by Thomas C. Wright Distinguished Professor Emeritus Department of History UNLV

A GUATEMALAN TRAGEDY by Thomas C. Wright Distinguished Professor Emeritus Department of History UNLV

The story of Ramiro García is framed by two transformative developments in Guatemala. The first was the arrival of banana cultivation and the creation of the United Fruit Company (UFCO), which established powerful U.S. influence over Guatemala. The second was the onset of the Cold War in Latin America, including Guatemala. This phenomenon led to further tightening of U.S. control and active support of reactionary dictatorships that employed state terrorism to retain their power.

Bananas were virtually unknown in the United States until they were exhibited at the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exposition, following which a growing demand for the fruit led U.S. entrepreneurs to establish large-scale banana plantations in the Caribbean lowlands of Central America, including in Guatemala. In 1899, a merger of banana and shipping companies formed the United Fruit Company (UFCO) which enjoyed the dominant position in Guatemalan banana production and exports. It became a vertically integrated organization, developing its own railroads and ports and an inventory of over one hundred ships, known as the Great White Fleet, to ship the fruit to the United States. To fill the ships for the return voyage and to economize on provisioning its workers, the company imported virtually all the food, clothing, and other goods consumed on its plantations via the fleet,

15

thereby injecting little capital into the Guatemalan economy and contributing little to Guatemala’s economic development.

UFCO not only dominated Guatemala: It was also the largest and most powerful entity in Central America. It was known as “the Octopus” for the extent and variety of its enterprises and its political power in the region. In addition to the Great White Fleet and the ports it built and owned, UFCO by 1912 owned Guatemala’s railroads through the International Railways of Central America, and soon extended its rails to El Salvador. In 1913, UFCO established the Tropical Radio and Telegraph Company that served much of Central America. The company thus achieved a near-monopoly of transportation and communication and charged exorbitant rates for its services. Having financial resources far greater than the Guatemalan government, UFCO shaped official policy so that it paid very little in property and export taxes and acquired huge tracts of land beyond the area used for banana cultivation. Owing to its economic and political power, UFCO became one of Latin America’s primary symbols of what many Latin Americans viewed as “Yankee imperialism.”

To protect growing U.S. investments in Central America and the Caribbean, the United States exercised what President Theodore Roosevelt called “Gunboat Diplomacy.” Between 1900 and 1933, the U.S. intervened militarily over forty times to assure that friendly governments were in power. In the case of Guatemala, U.S. interests were so well protected by pliant governments that no such invasion occurred, although during a regime change in 1920 the United States dispatched warships as a reminder for Guatemalans to continue the lopsided relationship.

The second essential context for the story of Ramiro García is the Cold War in Latin America. Between the end of World War II and the 1991 collapse of the Soviet Union, the United States and its allies confronted the Soviet Bloc in a tense international standoff, the Cold War. Although they had cooperated to defeat Nazi Germany, Italy, and Japan, the U.S.–USSR alliance ended as the Soviet Union imposed postwar dominance on Eastern Europe. As cooperation gave way to fierce competition between the former allies, the Soviet Union aggressively pushed to extend its influence to the developing world of Africa, Asia, and Latin America. The United States responded forcefully, and Latin America became a theater in the Cold War.

Guatemala became the first test case of U.S. resolve to keep Communist influence out of the Western Hemisphere. General Jorge Ubico, who seized power as the Great Depression destabilized the country in 1931 and ruled as a dictator, was driven from office in 1944. His successor was progressive Juan José Arévalo, who allied himself with moderate and leftist elements and enacted labor and

social reforms. Jacobo Árbenz, a leftist more committed than his predecessor to reform, was elected president in 1950. Whereas Arévalo’s reforms had focused on urban reform, Árbenz set his sights on economic and social change in backward and impoverished rural Guatemala.

Although not a Communist himself, Árbenz was on good terms with the growing Guatemalan Communist Party and appointed some of its members and allies to posts in his administration. Four Communists were also elected to the 58-seat national Congress. Although the Communists were a small minority in government and in the electorate, Washington became alarmed.

Árbenz enacted an agrarian reform law in 1952 that put him on a collision course with the Octopus. The agrarian reform law was moderate, calling only for expropriation of unused portions of large holdings. As UFCO kept a large part of the land it owned in reserve for future cultivation, it became a target of the

agrarian reform agency. The agrarian reform law authorized compensation in bonds for expropriated land based on its value as declared for tax purposes. As UFCO undervalued its lands to keep its taxes low, the government offered $628,000 in bonds while the company and the U.S. State Department demanded $15.9 million. It was no accident that Secretary of State John Foster Dulles and his brother, CIA director Allen Dulles, were closely associated with the law firm that represented the company.

In the United States, both government and private voices sounded the alarm: Guatemala was going Communist. Indeed, Árbenz had violated the two cardinal rules of behavior that the United States laid down for Latin American countries in the Cold War: He expropriated U.S.-owned property without prompt, adequate, and effective compensation, as determined by the United States; and he had shown himself to be, in

17

the lexicon of the time, “soft on communism.” Consequently, a drumbeat arose in the United States to eliminate Árbenz.

Faced with growing internal opposition and the threat of U.S. military action, and hobbled by a U.S. embargo of arms transfers to Guatemala, Árbenz ordered a shipment of arms from Communist Czechoslovakia, which arrived at Puerto Barrios in May 1954. To the U.S. government, this confirmed Árbenz’s Communist credentials and required his removal. Following an intense CIA-directed propaganda and psychological warfare campaign, a small CIA–trained and equipped invasion force assembled in neighboring Honduras. When the invaders crossed into Guatemala, the army refused to engage them and Árbenz resigned, blaming UFCO and the United States for his ouster. The leader of the invasion—Colonel Carlos Castillo Armas—took power, annulled the past ten years’ reforms, resumed the Guatemalan tradition of dictatorship, and plunged the country into a decades-long abyss of violence and repression.

Upon coming to power in Cuba in 1959, Fidel Castro called for revolution throughout Latin America. Ernesto (Che) Guevara published a book detailing the formula for replicating Castro’s successful guerrilla war. Having tasted reform under Arévalo and Árbenz, some Guatemalans were receptive to the message coming from Cuba. In 1962 a group led by former military officers formed a guerrilla movement, the Fuerzas Armadas Rebeldes (Rebel Armed Forces, FAR). This initial guerrilla group was eventually defeated, but others arose to take its place. Guerrilla activity varied in intensity over the years but the insurgents never gained the strength to threaten the overthrow of the Guatemalan government.

Rather than concede even limited reforms, from 1954 on the oligarchy–military alliance in Guatemala relied on state terrorism to preserve its monopoly of power and economic dominance. The U.S. government aided the parade of dictators by training and equipping counter-insurgency units within the Guatemalan army. U.S. Green Berets even reputedly engaged guerrillas in combat, while the CIA taught interrogation (torture) techniques. Thus equipped, the military regimes of the 1960s through the 1980s applied severe repression against all potential guerrilla sympathizers or collaborators, including peasants, left and moderate political parties, intellectuals, students, and union leaders. In addition to the army, the Guatemalan government used death squads, themselves comprised largely of army and police personnel. These repressive forces carried out assassinations and kidnappings in the urban areas and large-scale massacres of the predominantly Mayan peasantry in the countryside in the name of anti-Communism.

General Fernando Romeo Lucas García, dictator from 1978 to 1982, escalated the repression. Human rights groups reported over three

hundred massacres of Mayan peasants during Lucas García’s term. In 1980, twenty-seven leaders of the national labor confederation were kidnapped and never seen again. When villagers from one of the affected regions went to Guatemala City to protest, they were ignored until they occupied the Spanish embassy, aided by university students. Police then allegedly torched the building rather than heed the ambassador’s pleas for negotiations, killing all the protestors and several Spanish diplomats. Most research and writing on Guatemalan state terrorism has focused on the genocide of Mayan Indians, which escalated under Lucas García’s successor, General Efraín Ríos Montt.

By the end of Guatemala’s long nightmare in 1996, when peace accords were signed, some two hundred thousand persons had been killed by government forces, the vast majority of them peaceful Mayan peasants. Given that grim statistic, it is not surprising that far less attention has been paid to the urban struggle against dictatorship and repression. Coalitions of students, workers, progressive parties, union leaders, intellectuals, and other city dwellers had been pivotal political actors since at least 1944, when they were largely responsible for the overthrow of dictator Jorge Ubico.

Ramiro García sacrificed his life for freedom and justice as part of the urban struggle against state terrorism during the Lucas García dictatorship. The exhibition by his daughter, Elena Brokaw, tells the story not only of his martyrdom but of the terror faced by those who spoke out against the brutal Guatemalan dictatorships of the Cold War period.

19

20

AUDIO READING BY ELENA BROKAW

You Take the Cake

Access to food is an effective tool to control people, both in and out of interrogations.

Part of the struggle outlined in the torture manual is the need for control. From the moment victims were taken, their environment was manipulated by the torturers. This included the use of physical pain but also psychological too. Physical weakness is a coercive technique that can debilitate your ability to resist. The goal of the torturer is always to get more information. A corpse cannot provide information but a broken human will tell you everything you want to know. Manipulation is key to destroying the capacity to resist. The information is what matters; nothing else does. Make them dependent and they will rely on you for everything and give you anything you ask to make you happy.

21

22 22

23

24

25 25

26 26

27 27

AUDIO READING BY ELENA BROKAW

Just Between You and Me

Torture victims were presented with a new reality where the only person they were told they could trust was their interrogator.

WARNING

The following reading contains a description of torture including sexual assault experienced by Diana Ortiz, a victim of the state terrorism in Guatemala during the armed conflict. This content is disturbing, so I encourage everyone to prepare themselves emotionally before proceeding. If you believe that the reading will be traumatizing for you, then please forgo it.

While the manual may make it seem like the experience of torture is a contest between two equals, those that lived through it tell a different tale. Sister Dianna Ortiz, a Catholic nun, was kidnapped in November of 1989 the Inter-American Commission on Human right documents her experience as follows:

“According to Sister Ortiz’s statements, she was kidnapped from the gardens of the Posada de Belen on November 2, 1989. The two men forced Sister Ortiz to walk with them to the back of the gardens at the Posada de Belen where there was an opening in the wall surrounding the gardens. The two men and Sister Ortiz walked out of the gardens and along a dry riverbed until they came to the street leading out of Antigua. The two men then forced Sister Ortiz to climb aboard a public bus. The first man showed Sister Ortiz a grenade in the pocket of his jacket and warned that if she tried to escape, innocent people would die. Sister Ortiz and the two men exited the bus near a sign for Mixco, a town outside of Guatemala City.

According to Sister Ortiz’s statements, they walked down a dirt road until

they came to a white National Police patrol car. The first man went ahead and talked with the driver, a uniformed National Policeman. Sister Ortiz was then blindfolded and placed in the backseat of the patrol car. The two men also got into the car. The Policemen said to the men, “I see that your trip was successful.”

Sister Ortiz was driven in the police car and was then taken out of the car and moved into a warehouse-like building. Sister Ortiz could hear a woman’s screams and the moans of a man. Sister Ortiz was ushered into a room where she was seated on a chair. The policemen and the two men who had kidnapped her left the room. After hours had passed, the second man who had come to the gardens to kidnap her entered the room and blindfolded her again. Two more men entered the room, and Sister Ortiz recognized the voices as belonging to the policeman and the first man who had taken her from the gardens. According to Sister Ortiz’s statements, the men removed some of her clothes and started to touch her body. Then the man that had first accosted her in Guatemala said, “We will get

28

to that later, we have to take care of business first.” He said that they were going to play a game. If she gave an answer that they liked, he said that they would let her smoke; if they did not like the answer, they would burn her with a cigarette.

The men asked Sister Ortiz her name, where she lived, what work she was involved in, and if she knew any subversives. With every answer, regardless of what she said, they burned her with a cigarette. They asked the same questions again and again and burned her again and again.

At some point, they stopped the interrogation and removed Sister Ortiz’s blindfold. They showed her some pictures of herself taken in various parts of the country. The men also showed Sister Ortiz pictures of indigenous people. In one picture, a man was holding a gun and, in another one, a woman with long black hair had a gun. They insisted that Sister Ortiz was the indigenous woman in the picture and said that the indigenous people were subversives. One of the men then blindfolded Sister Ortiz again, and somebody hit her in the face so hard that she fell to the floor. Two of them pulled her up to a sitting position and took off the rest of her clothes. According to Sister Ortiz’s statements, the men began to abuse Sister Ortiz sexually and raped her repeatedly. Sister Ortiz was told that they would stop if she gave them the names of the people in the photographs and the names of her contacts. Sister Ortiz passed out. According to Sister Ortiz’s statements, at one point she regained consciousness and realized that her wrists had been tied to something overhead. She felt that she was in a courtyard of some type. The uniformed policeman asked again about the people in the photographs and raped her. Then Sister Ortiz heard people

moving a heavy block on the ground. She was lowered into a pit which was filled with bodies and rats. Sister Ortiz passed out again. She woke up on the ground, and the men were again abusing her sexually.

Later, Sister Ortiz was taken back into the room and questioned again. Her captors held her down on the ground and began to rape her again. Then somebody said, “Alejandro, come and have some fun.” A man who had just entered answered with an expletive in English. Then he switched to Spanish and told the men that Sister Ortiz was an American and that they should leave her alone. He announced that her story was already being covered in the news. He told the men to leave the room and helped Sister Ortiz to put on her clothes.

“Alejandro” took Sister Ortiz out of the building and drove her out of an attached garage. As they left, he repeatedly apologized and said that it had all been a mistake. He said that they had confused her with somebody else. Although “Alejandro” continued to speak in Spanish, he understood Sister Ortiz when she spoke in English, and he spoke Spanish with a Northamerican accent. In Sister Ortiz’s statements, she indicates that she believes that this man was from the United States.

When the car in which Sister Ortiz and “Alejandro” were driving stopped for traffic, Sister Ortiz saw signs indicating that she was in zone 5 of Guatemala City. She jumped out of the car and fled. She ran until a woman offered to take her into her home. She stayed there for several hours and then found her way to Hayter Travel Agency in Zone 1 of the city. She contacted members of her religious community who came to retrieve her. She left Guatemala for the United States within 48 hours of her escape.”

29

30 30

Ramiro Antonio García Jimenez (1952-1980) was an architect, graphic designer, draftsman, painter, and photographer. Born in Asunción Mita, Guatemala he studied and taught at the Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala in Guatemala City. As a founding member of the Frente Estudiantil Revolucionario

“Robin García” (Robin García Revolutionary Student Front (FERG)) and a member of the Ejército Guerrillero de los Pobres (Guerrilla Army of the Poor (EGP)), he stood against the repressive policies of the dictatorial Guatemalan government, using his skill as an illustrator to communicate messages of resistance through the cartoons he drew for the Nuevo Diario newspaper. In 1980 he was assassinated by the Guatemalan military while he was visiting family in Asunción Mita. His murder was documented as case #952 in Guatemala, memoria del silencio, an investigative report into the country’s era of armed conflict published by La Comisión para el Esclarecimiento Histórico (Commission for Historical Clarification) in 1999.

Elena Brokaw is a writer and curator. She received her Creative Writing Literary Nonfiction MFA from the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, in 2021, and she was an inaugural recipient of a Periplus Fellowship in the same year. Born in Guatemala City, Guatemala, she made her way to her current home in Las Vegas by way of New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Utah. Her desire to gain insight into the assassination of her father, Ramiro García, led to the creation of Human Resource Exploitation: A Family Album.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Human Resource Exploitation: A Family Album was produced with the assistance of the Marjorie Barrick Museum of Art staff: Alisha Kerlin, Chloe J. Bernardo, Paige Bockman, Dan Hernandez, LeiAnn Huddleston, Emmanuel Muñoz, and D.K. Sole. Further assistance was provided by the Museum’s volunteers and interns: Lauren Dominguez, Hannah Dondero, Tracy Fuentes, Sydney Galindo, Naes Pierott, Andrea Noonoo, and Nanako Wagley. The artist would like to thank the family, friends, and colleagues who have given unfailing support.

This exhibition was funded in part with support from Nevada Humanities and the National Endowment for the Humanities. Further assistance was provided by the UNLV Jean Nidetch Care Center, and the WESTAF Regional Arts Resilience Fund, a relief grant developed in partnership with The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation to support arts organizations in the 13-state western region during the COVID-19 pandemic.

PHOTOGRAPHY CREDITS NOTES

Chloe J. Bernardo

Josh Hawkins/UNLV Creative Services

Mikayla Whitmore

Images courtesy of the artists

Cover page, 10, 15, and 17

Page 34

Pages 5, 14, 19, 23, 26, and 31

Cover page, 7, 9, 11, 13, 20, 22, 24, 25, 27, 30, 32, and 33

35

A Guatemalan Tragedy is written by Thomas C. Wright, Distinguished Professor Emeritus, Department of History, UNLV

ADDITIONAL READING

Hyperallergic article on Elena Brokaw's Human Resource Exploitation: A Family Album https://hyperallergic. com/697643/human-resourceexploitation-a-family-albumelena-brokaw/

Interview by Nevada Public Radio with Elena Brokaw https://knpr.org/desertcompanion/2021-11/arttragedy

36

8. A Love Like Ours

AUDIO FILES

6. Introduction

12. First Day of School

28 – 29. Just Between You and Me

Celebrating Life

21. You Take the Cake

MARJORIE BARRICK MUSEUM OF ART

The Marjorie Barrick Museum of Art believes everyone deserves access to art that challenges our understanding of the present and inspires us to create a future that holds space for us all.

Located on the campus of one of the most racially diverse universities in the United States, we strive to create a nourishing environment for those who continue to be neglected by contemporary art museums, including BIPOC and LGBTQIA+ groups. As the only art museum in the city of Las Vegas, we commit ourselves to leveling barriers that limit access to the arts, especially for first-time visitors. To facilitate access for low-income guests we provide free entry to all our exhibitions, workshops, lectures, and community activities. Our collection of artworks offers an opportunity for researchers and scholars to develop a more extensive knowledge of contemporary art in Southern Nevada. The Barrick Museum is part of the College of Fine Arts at the University of Nevada Las Vegas (UNLV).

Alisha Kerlin

Chloe J. Bernardo

Paige Bockman

Dan Hernandez

LeiAnn Huddleston

Emmanuel Muñoz

D.K. Sole

COLLEGE OF FINE ARTS

Published by UNLV Integrated Graphics Services Integrated Graphics Services

University of Nevada, Las Vegas Box 1028

4505 S. Maryland Pkwy.

Las Vegas, NV 89154

Copyright © Marjorie Barrick Museum of Art

Marjorie Barrick Museum of Art

University of Nevada, Las Vegas

Box 4012

4505 S. Maryland Pkwy.

Las Vegas, NV 89154

702-895-3381

www.unlv.edu/barrickmuseum

Artworks by Ramiro García and Elena Brokaw © 2020 by Ramiro García and Elena Brokaw

Catalog designed by Chloe J. Bernardo

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or

of

37

any manner

the prior

used in

without

written permission

the copyright owner, except for the use of brief quotations in a book review.

A GUATEMALAN TRAGEDY by Thomas C. Wright Distinguished Professor Emeritus Department of History UNLV

A GUATEMALAN TRAGEDY by Thomas C. Wright Distinguished Professor Emeritus Department of History UNLV