Her job is a calling

page 4

for anyone touched by cancer

Saving lives with surgery

Eliminate the cancer, preserve the bladder

How biomarkers may help you

What’s a platelet?

Her job is a calling

page 4

for anyone touched by cancer

Saving lives with surgery

Eliminate the cancer, preserve the bladder

How biomarkers may help you

What’s a platelet?

BY JIM HOWE

My name is Tom, and I’m a chaplain here at the cancer center. It’s nice to meet you,” Tom Anderson tells people at the facility several days a week.

“Sometimes people are wondering what that means,” he says, “and I’ll just say, ‘It’s nice to have someone to speak to, to have a couple of good ears to listen—and I’ve got a couple of good ears.’ And they’ll perk right up at that and be so happy you stopped by.

“I’ll ask permission to check back with them on another visit. I’ll say it doesn’t have to be about faith. Sometimes it’s just nice to have someone to talk to.”

Anderson, the first chaplain to be embedded at the cancer center, might meet patients as they are being infused with chemotherapy drugs, as they sit in waiting areas or wherever they may be, sometimes by referral, sometimes randomly.

He recalls a woman in the palliative care service whose son died unexpectedly and was unable to have a conversation during Anderson’s first three visits. “But I just said, ‘I’m here; if you’d like to talk, that’s fine, and if you’re not able to, that’s fine, too.’“ On his fourth visit, she opened up about what was on her mind.

Anderson is a lay chaplain. Raised as a Catholic, he was active in his church in Skaneateles, and about a dozen years ago began volunteering for prayer visits to patients at St. Joseph’s Hospital Health Center.

“What I came to understand very early on was people wanted and needed more than someone just to come into the room to receive

Communion or to have a prayer said on their behalf. People needed to share a story about what they were experiencing and what they were feeling,” he says.

Anderson began taking classes through Upstate in clinical pastoral education, or CPE—hospital chaplain training—and became a staff chaplain at Crouse Hospital before working as a chaplain at Upstate.

Like all of Upstate’s chaplains, Anderson serves people of any faith, or no faith.

His position at the cancer center acknowledges “the unique issues that people face undergoing cancer treatment that require in-person relationships to fully address, and to go where that person is—in infusion or radiation or in the waiting room—and it acknowledges that holistic care must include the spiritual to fully address the treatment care plan that we desire to give patients and their families,” says the Rev. Terry Culbertson, who oversees the department of spiritual care at Upstate Medical University.

She says seeing that Tom is embedded at the center and available for consultation and conversation also helps support the medical staff.

“Everyone has something that is spiritual that brings meaning into their life,” Anderson says, “and it is important to journey with people and hopefully help them tap into those things that are helpful to them.

“I’d like to think that my ministry is a blessing to others, but I know that it’s a very rich blessing to me. Sometimes I think I get more out of those encounters and relationships with people than they do.” u

Ryan Tyler of Liverpool is free of headaches and able to ride his bike again after undergoing laser ablation. See story, page 6. Photo by Susan Kahn.

The Upstate Cancer Center is part of Upstate Medical University in Syracuse, New York, one of 64 institutions that make up the State University of New York, the largest comprehensive university system in the United States.

Upstate Medical University is an academic medical center with four colleges, a robust biomedical

research enterprise and an extensive clinical health care system that includes Upstate University Hospital, Upstate Community Hospital, the Upstate Golisano Children’s Hospital and many outpatient facilities throughout Central New York — in addition to the Upstate Cancer Center. It is located at 750 E. Adams St., Syracuse, NY 13210.

BY AMBER SMITH

Her big brother looked at Mandye Blair after learning he had weeks to live. Lung cancer had spread to his liver, brain and pancreas. “If you were just told you were about to die,” he asked her, “would you be happy with your life?”

Michael Blair passed away a few weeks later, in March 2019, at age 36. Mixed with her grief, Blair kept coming back to his question.

She was working long hours running an Italian restaurant with her husband and raising their young son. She was busy and did not mind the work, but she did not feel fulfilled.

“I decided to make a huge life transition and come to the Upstate Cancer Center,” she said.

“After he passed away, I knew that I was meant to be here. There was something about being here that I needed for my own healing process.”

Blair has worked at the cancer center for three years now, handling referrals for patients who will be new to Upstate. She helps gather all their medical records in advance, so their first visit is productive. She can relate to their nervousness about needing cancer care, and she builds relationships.

“I never thought I would leave our restaurant. My son has grown up in those walls,” she said, explaining that she still helps out with payroll and other things as needed. “But this is a totally different type of fulfillment. I really, truly love my

job.” She thinks of her brother when she enters the cancer center—and when she sees a tiger.

Before he died, she asked Michael for a special sign that would tell her he was still with her. Some people choose cardinals. Michael chose a tiger.

“Michael, tigers don’t just walk down the street. When am I going to see a tiger?” she protested. But he stuck with tiger.

Recently her son, now a teen, was admitted to the hospital for some testing. Together they decided to pass the time with Wordle, a word-guessing game. Blair said she knew her brother was with her when the first answer was T-I-G-E-R. u

BY AMBER SMITH

Working together, Upstate surgeons saved a father and his adult son from two different types of cancer, about a year apart.

“It was very much a team effort,” surgeon Kristin Kelly, MD, said of the two operations, which were among the most complex for herself, Mashaal Dhir, MD, and Thomas VanderMeer, MD. She said it is unusual for two family members to need care for two different and aggressive cancers that are not genetically related.

The surgeons worked together on both cases because in big operations, “there is a lot of thinking on our feet,” Kelly said. “Sometimes it helps to have multiple brains thinking about approaches.”

Brian MacDavitt, 75, worked for 35 years at the Auburn Correctional Facility. He’s been retired for 20 years.

He went to a routine doctor’s appointment in the fall of 2021, and because his skin and eyes were yellowed, he was directed to the emergency department at Upstate. Jaundice can be a sign of an urgent liver or bile duct problem.

“I was feeling great,” MacDavitt recalled. Then medical images and tests revealed pancreatic cancer. He would need a complicated surgical procedure. (Learn more about the so-called “Whipple” procedure on page 9.) His operation, led by Dhir, lasted about 14 hours.

MacDavitt wasn’t sure he would survive. In addition to the cancer, he has diabetes and heart disease. “But they caught it early,” he said of the pancreatic cancer, and the surgery was a success. Surgeons removed part of his pancreas, intestines and bile duct.

After he recovered, he took chemotherapy for six months under the direction of oncologist Bernard Poiesz, MD.

MacDavitt’s son, Christopher, 43, helped care for him at the family home in Auburn.

One morning in the fall of 2022, soon after the elder MacDavitt completed chemotherapy, his son awoke in a panic. He’d gone to bed feeling somewhat ill. Now his chest was tight, he was gasping to breathe, and his belly was distended.

“It looked like I was pregnant,” Christopher MacDavitt remembered. “I had a tumor that ruptured overnight, and it ended up freakishly growing.”

His father drove him to the emergency department in Auburn. From there he was airlifted to Upstate. With a large mass in his stomach, doctors placed MacDavitt in a medically induced coma in the intensive care unit. His kidneys were failing, and he was bleeding internally.

“We had to do what we could to get the bleeding to stop,” VanderMeer said, explaining that trauma surgeons opened MacDavitt’s abdomen to relieve the pressure. VanderMeer and Kelly devised a surgical plan.

“Despite the circumstances and the fact it was far from ideal, we felt we needed to remove the tumor,” he said. “It was quite an extensive operation” involving the pancreas, spleen, part of the stomach and colon. The tumor weighed about 17 pounds.

MacDavitt says it was adrenal cortical carcinoma, a rare and aggressive cancer that starts in the adrenal glands, which sit atop the kidneys. “I’m lucky even to be alive,” he says.

Before he was discharged, more cancer was found in his lungs. So MacDavitt had four six-day courses of chemotherapy under the care of medical oncologist Rahul Seth, DO. He also began having medical scans every three months.

In March 2024, cancer came back, this time in his liver. “The same people who saved my life before saved it again,” he said of Kelly and VanderMeer. “They had to remove 20% or 25% of my liver with the tumors.” He also credits nurses on multiple floors of the hospital with helping restore his health.

MacDavitt is now back to work, at FedEx. He takes oral chemotherapy, and he continues with the regular medical scans. “I’m doing good now,” he said. His oncologist agrees. “The prognosis is good,” Seth said. “He seems to be tolerating it well.” u

Brian MacDavitt and his son, Christopher MacDavitt, both seated, credit Upstate surgeons with saving their lives, including, left to right, Kristin Kelly, MD, Thomas VanderMeer, MD, and Mashaal Dhir, MD. Photo by Susan Kahn.

BY AMBER SMITH

Aminimally invasive surgical technique for treating epilepsy that uses a laser to ablate brain tissue can also help people with brain tumors.

The technique—magnetic resonanceguided laser interstitial thermal therapy—was the neurosurgical approach for two boys, both patients at the Upstate Golisano Children’s Hospital, who were willing to talk publicly about their experiences. One was treated for epilepsy. The other had an aggressive cancer.

At Oswego High School in October 2023, Tucker Fenske collapsed.

His parents, Melissa and Stuart Fenske, rushed to meet the ambulance carrying him to the emergency department of Upstate University Hospital in Syracuse. There they learned their son’s periodic headaches likely had been signaling the seizure that caused him to collapse. He remained in the Upstate Golisano Children’s Hospital for three days.

Doctors discovered a brain tumor in his front left lobe, which controls speech and language.

Tucker’s mother, Melissa Fenske, became especially concerned. She had been 5 years old when her 9-year-old brother died from a brain tumor. She remembered how sick he was his whole life.

Tucker had a brain biopsy on Halloween 2023. The tumor was benign, but it was causing seizures. He had another seizure, which his mother witnessed, that December. Five days before Christmas 2023, he underwent laser ablation.

The procedure occurs with the patient under general anesthesia, wearing a special frame attached to his scalp to hold his head still. Through a small hole, the surgeon directs a needle-like, fiber-optic laser probe to the lesion in the brain using stereotactic navigation; once medical images confirm the probe’s location, the tip heats up to do the ablation, which

damages the surrounding abnormal tissue, killing cells and helping to shrink a brain tumor or change its texture, so it’s easier to remove.

Some of the advantages of this therapy: it allows better access to deep brain lesions, surgical complication rates are reduced, and patients have shorter hospital stays and quicker recoveries. Laser ablation leaves patients with more pleasant aesthetic results, and it’s a procedure that can be repeated if necessary.

Tucker, who turned 15 in May 2024, was able to return to school after winter break. He has repeated magnetic resonance imaging scans (MRIs). His doctor told him the expectation is that the tumor will continue shrinking and eventually disappear within a year.

Ryan Tyler of Liverpool was 8 when he started having headaches in August 2019. His pediatrician directed his parents, Traci and Mike Tyler, to bring him to the hospital.

Compared with traditional open brain surgery, laser ablation:

• is minimally invasive, so patients recover more quickly, with fewer complications and smaller scars.

• can access tumors or areas of damaged tissue, called lesions, that are deep in the brain without cutting through healthy tissue.

• allows the neurosurgeon to treat more than one lesion in the same operation and reduces the need for follow-up radiation therapy in cases of cancer.

Wondering what’s new in lung cancer surgery? What is bispecific antibody therapy, anyway? Which complementary therapies work alongside standard cancer treatments?

“Within probably 12 hours, he had his first surgery,” Traci Tyler recalls.

Ryan had a medulloblastoma, an aggressive cancerous tumor about 2 inches long and more than an inch wide, from the back of his head.

Predictably, after the surgery Ryan could not walk, talk or eat for about three months. He underwent 36 rounds of radiation therapy to his brain and spine. After that, six months of chemotherapy lasted until May 2020, in the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. He regained the ability to speak and eat, and physical therapy helped him walk again.

Eighteen months later, Ryan relapsed. His neurosurgeon recommended the laser ablation procedure.

“It seemed like the best approach for us after what he went through with the initial surgery,” Traci Tyler says. Her son came home from the hospital the next day.

After a year of chemotherapy, a lesion was discovered in a different area of the brain, and another emerged near the initial tumor. Ryan had volunteered for a study of an immunotherapy drug called SurVaxM, and his parents think it helped. With the second laser ablation in February 2024, the spot near the initial tumor was almost gone, and the newer lesion was broken up considerably.

Now he is on chemotherapy again. “The treatment plan that he’s on now, he’ll be on for two years,” his mother explains. “The plan is just to keep the cancer cells out of his body. Hopefully, no surprises pop back up again.”

Traci Tyler says he was able to return to school, and although Ryan does not have much energy, he likes riding his bike and playing games with friends. He’s 13 now and free of headaches. “Ryan is a pretty amazing kid. He takes everything in stride. He does what he has to do. He never complains,” she says. u

Conversations about these topics, and many more, are available in the easily searchable database of “The Informed Patient” podcast at upstate.edu/informed. Most of the podcasts feature health care providers and researchers from Upstate Medical University sharing their expertise. They answer questions curious patients would have and explain complicated subjects in terms that are easy to understand. And they are accompanied by transcripts.

“The Informed Patient” is a Q&A podcast focused on health, science and medicine, available on YouTube, Spotify and other podcast platforms. It began as a radio talk show in 2006. Many of today’s podcasts continue to appear on the radio program, “HealthLink on Air,” at 6 a.m. Sundays on WRVO Public Media. u

About half the people with colorectal cancer may see the cancer spread to their liver.

In the past, that usually meant surgery and chemotherapy, or maybe some form of radiation therapy.

Now hepatic artery infusion therapy can improve survival and life expectancy for some patients whose colorectal cancer has spread to the liver, or who have bile duct cancer arising in the liver.

These cancers “derive their blood supply from the hepatic artery, which is the liver artery,” explains Mashaal Dhir, MD, chief of hepatobiliary and pancreatic surgery at Upstate. “And the liver has two blood supplies, the artery and the vein. So the principle of this therapy is to deliver the high dose of chemotherapy directly into the artery, which supplies these tumors and in a way could be 400 times more effective than infusing the same chemotherapy in the IV form,” which would spread throughout the whole body.

Dhir says patients experience few side effects from the chemotherapy, since this method allows the liver to be targeted. Patients first must have a pump implanted beneath their skin. It connects to a catheter (thin tube) that is inserted into the liver artery. The size of the tumor or tumors is monitored via imaging scans.

Several studies compare traditional chemotherapy with hepatic artery infusion therapy. Dhir says for patients whose tumors cannot be removed surgically, “if we add this therapy to their chemotherapy regimen, it can significantly prolong their survival.” He adds that many of those patients may see their tumors shrink so that they can be removed surgically.

“So the data is very, very encouraging, especially when we combine this with modern chemotherapy regimens.” u

Infusing high doses of chemotherapy through the hepatic artery can be more effective than intravenous chemotherapy for certain tumors in the liver. The pump and catheter device is highlighted and magnified to the left of the illustration.

The Whipple” is a surgical procedure that removes the head of the pancreas, the first part of the intestine, called the duodenum, and the bile duct. It’s used to treat cancers that arise in those areas and is named after the surgeon Allen Oldfather Whipple.

Surgeons may also have to work on nearby blood vessels or the gallbladder, explains Mashaal Dhir, MD, chief of hepatobiliary and pancreatic surgery at Upstate.

“It is one of the most challenging procedures that we do because the pancreas is in general wrapped around two major blood vessels, SMA (superior mesenteric artery) and SMV, (superior mesenteric vein,)” he explains.

“That’s why we encourage patients to have surgery in high-volume centers, and Upstate is one of the high-volume centers. That means we do this a lot. We do it well. And we monitor our outcomes.”

When pancreatic cancers are detected early, this procedure is potentially curative. Patients may spend a week in the hospital, and full recovery may take six to eight weeks, sometimes up to 12 weeks. They undergo repeated imaging scans every three months for the first three years after surgery, and then every six months from years three to five.

The surgery can be done as an open procedure through a large midline incision and generally takes about six to eight hours.

It can also be done robotically, through multiple small (quarter-sized) incisions on the belly. When a robot is used, the operation may take eight to 12 hours “because we have to work under magnification,” he says. “It’s more methodical, in a way, that we have to make finer movements because we are in a limited space. We have to blow up the belly with the gas, create the space and work around the blood vessels.”

Most patients prefer the robotic procedure because recovery is generally quicker and involves less pain. But not all patients have a choice. To qualify for robotic, the tumor must be smaller and located away from the blood vessels. u

BY AMBER SMITH

Mammograms screen for breast cancer. Colonoscopies screen for colon cancers. Did you know lung cancer screening exists, to find early lung cancers?

“Getting the word out has been the biggest hurdle that we’ve had, just making sure that people know that lung cancer screening exists,” says Michael Archer, DO, medical director for the lung cancer screening program at Upstate.

“There is good research to show that when folks are screened for lung cancer, we identify tumors earlier, and we are able to get patients treated to cure more frequently,” Archer says.

Early diagnosis is key, for a cancer that accounts for about one in five cancer deaths.

Once diagnosed, the next step is learning the stage of a cancer, or how advanced it is, says Jason Wallen, MD, medical director of the lung cancer and thoracic oncology program at the Upstate Cancer Center. That helps determine which treatments are options.

Surgery is often an option for early-stage and even Stage 2 or 3 lung cancers.

At Upstate, all of the lung cancer surgeries are minimally invasive and done with robotic assistance, Wallen says, adding that most cancer centers across the country are adopting minimally invasive surgery.

“It’s better for patients because the incisions are smaller, which generally means that they hurt less. There’s less damage to bones, so less cracking or cutting of bone involved. In fact, in most minimally invasive surgeries, there’s none of that.

“And so you see faster recoveries, less use of narcotics, which many people are concerned about these days. You see shorter hospital stays and, even more importantly, fewer complications. So we definitely want to be doing as much minimally invasive surgery as possible,” he says.

The Society of Thoracic Surgeons collects data from Upstate for its national database of all the major thoracic surgical centers in the United States. Wallen says, “We are below average for our complication rates. We are amongst the top for our rates of minimally invasive surgery, and we have one of the lowest mortality rates in the country.” u

Who is eligible for lung cancer screening?

• Smokers or former smokers from 50 to 80 years old.

• Smokers with 20-pack years or greater smoking history (that would mean having smoked a pack a day for 20 years, two packs a day for 10 years, or another variation).

• Former smokers who quit within the previous 15 years.

A computerized tomography scan of the lung takes 20 seconds and can detect tiny spots—known as nodules—years before they would be seen on a regular chest X-ray. These nodules may be signs of early lung cancer.

To reach the lung cancer screening program, call 315-464-7460. Medicare and many private health insurers cover screening.

Ronaldo Ortiz-Pacheco, MD, tells patients to think of the lungs as a tree.

The main windpipe, or trachea, is the trunk of the tree, and it’s hollow on the inside. It divides into two big bronchial branches, and “then they start dividing into basically little microscopic berries, if you will.” Cancers can arise in any portion of the tracheal-bronchial tree, or in the parenchyma, or meat of the lung.

Biopsies, to obtain a sample of cells or tissue, are done to get a diagnosis. The way they’re done depends on the size and location of the nodule, or area of concern.

An interventional radiologist may insert a needle through the skin, into the lung and into the nodule. Or a surgeon or pulmonologist could do a bronchoscopy, in which the nodule is accessed through the windpipe.

At Upstate, doctors have the option of using an endoluminal system that is basically a robotic bronchoscopy. Ortiz-Pacheco says it’s like having your esophagus checked in an endoscopy

procedure or your colon checked in a colonoscopy. Doctors use a control panel to navigate the robot in the airways.

“We make a virtual map of the lungs using a preexisting CT (computerized tomography) scan. We make a virtual image of the nodule. And the bronchoscope kind of makes a path which we follow, based on the imaging that we have,” he explains.

“It’s a 3D image, superimposed onto a live view, and we can drive up to the area in question and then biopsy the nodule with needles, forceps, cytology brushing (to collect sample cells), just to maximize the amount of cells that we can get to identify what exactly is going on with that nodule.”

Ortiz-Pacheco says the robotic bronchoscopy also allows lymph nodes in the chest to be examined at the same time.

Results typically are available within three to five days. And remember, not all nodules are cancer.

BY AMBER SMITH

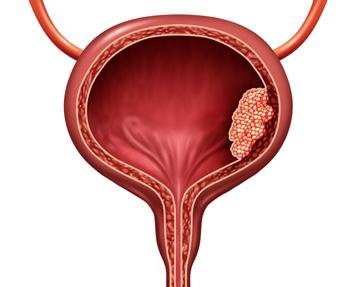

Anew, targeted therapy called TAR-200 might be an option for some patients with high-risk bladder cancers who would rather not have their bladders removed.

This treatment is meant for patients with Stage 1, or superficial, bladder cancer, meaning the cancer has not invaded the muscle of the bladder, said urologist Joseph Jacob, MD, who specializes in urologic cancers. Usually, these patients are first treated with multiple “intravesical” treatments placed within the bladder. One of the most common of these treatments is BCG, Bacillus Calmette-Guerin. That doesn’t always work.

“That’s one of the reasons why this therapy is filling such a high need,” explained Jacob. “After BCG, there’s not a lot of options besides removing the bladder.”

TAR-200 is a targeted release system meant to eliminate cancer cells and preserve the bladder at the same time.

“We’ve never really treated bladder cancer like this before,” Jacob said, describing a silicone drug delivery device that looks like a pretzel you can straighten out (see image below). It is deployed into the bladder through a hollow tube, or catheter. Then it delivers sustained-release gemcitabine, a chemotherapy used to treat bladder cancer.

“The cool thing about it is that, for example, when we give BCG in the bladder, patients hold it an hour, two hours at the max. Some patients can only do 30 minutes. The whole idea behind this TAR-200 device is, it floats in your bladder, and it gives a steady dose of chemotherapy inside your bladder for about seven days or more,” he said.

“You can see the huge difference between the amount of time the bladder cancer is exposed to the drug,” Jacob continued. “We think that’s one of the reasons why this is performing so well so far in the clinical trials.”

Several patients from Upstate are participating in clinical trials for TAR-200, after not seeing success with BCG, and Jacob says the results are promising. Most drugs have a complete response rate—meaning no cancer after six months—of 15% to 25%. The TAR-200 therapy has shown an 83% response rate, he told attendees at the American Urological Association annual meeting in 2024.

Similar to other treatments placed in the bladder, patients on TAR-200 reported side effects of needing to urinate frequently and/or urgently, and some pain on urination. Some reported a sensation of a foreign object in their bladder, while others felt nothing.

Jacob expects Food and Drug Administration approval soon. He’s not certain if patients will receive TAR-200 only after trying BCG. Another trial compares the effectiveness of TAR-200, alone, with that of BCG. u

The bladder is a multilayered muscle that squeezes.

The brain, through the spinal cord and nerves that attach to the bladder, basically tells your bladder to squeeze or not to squeeze.

The deepest layer is the muscle. Then there’s connective tissue. And then there’s another layer that’s called the mucosa. It’s the smooth, shiny layer, like the inside of your mouth.

This is how bladder cancer is staged. Mucosa is the first layer. That would be Stage Ta, early, or superficial.

Once it gets into the connective tissue—doctors call it the lamina propria—that would be Stage T1.

And then the next layer would be the muscle, or the detrusor muscle. You may hear that that’s the bladder muscle, and that would be Stage T2. Seventy percent of bladder cancers are non-muscle invasive; but untreated, some bladder tumors will invade the muscle.

Staging in bladder cancer really, really matters because it can change the treatment drastically.

At Stage T2, or muscle-invasive bladder cancer, the type of treatments that we put inside the bladder, like the intravesical therapies, don’t work. Once you have muscleinvasive bladder cancer, this is a disease that can spread, or we call it “metastasize,” into the bloodstream. At that point it becomes a life-threatening disease. We usually do things like chemotherapy or removing the bladder or irradiating the bladder. So it’s a very different approach.

When you have patients who have non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer, basically the goal is to save the bladder, to prevent the superficial cancers from progressing or becoming more aggressive and becoming muscleinvasive bladder cancer.

There’s also grade. So there’s stage, and there’s grade. Grade is basically: How ugly does the tumor look?

If it’s high grade, that means it’s aggressive and ugly looking. If it’s low grade, it’s non-aggressive and doesn’t look as ugly. So usually in patients with high grade, those cancers can have more of a chance of becoming more aggressive and more of a chance of becoming invasive.

BY AMBER SMITH

Imagine a diagnosis of pancreatic cancer.

Biomarker testing identifies a targeted medication therapy. Soon after, there’s no more cancer. Thomas VanderMeer, MD, has seen this happen. “We’ve had patients who had the cancer completely eradicated,” he says.

VanderMeer is a pancreatic surgeon and the interim director for the Upstate Cancer Center. He’s grateful Gov. Kathy Hochul signed a law requiring health insurers in New York to pay for life-saving cancer biomarker testing, which makes targeted therapy possible. It took effect Jan. 1, 2025.

Biomarkers became a tool for cancer care providers starting in 2001, when the Food and Drug Administration approved the drug Gleevec to target a specific protein on a cancer cell. VanderMeer says the drug was incredibly effective against a couple of rare cancers.

“Since then, molecular targets and their biomarkers have been identified in many different cancers with numerous new drugs created to interfere with cancer cell growth,” he says. “And now there are so many potential molecular targets for treatment that testing

is done on a panel of over 300 molecular alterations.”

Today the cancers with molecular targets for treatment are most commonly seen in nonsmall cell lung cancer, melanoma and breast and colorectal cancers. “Increasingly, we are finding that these new drugs work against more and more types of cancer,” VanderMeer says.

Targeted therapy is preferred because it’s less toxic than traditional chemotherapy, whose agents interfere with the growth of cancer cells as well as other cells throughout the body.

The targeted therapies modify specific molecular processes that are unique to cancer cells and interfere with cellular signals that cause cancer cells to grow or to limit our own body’s immune response to fight the cancer.

“As a result, there’s much less collateral damage to normal cells because the activity of these drugs is so much more specific and limited,” explains VanderMeer. He says newer treatments are designed to reprogram a patient’s own immune cells to kill their cancer.

Before the new law, a third of health insurers would not pay for biomarker testing,

A biomarker is a sign that something is happening in our bodies. In the case of cancer, biomarkers are molecules that indicate if cancer is present, what abnormality is causing the cancer to grow, how active it is and how it will respond to different types of treatment. Some biomarker testing is done with blood tests, and some requires tissue from a biopsy.

according to Michael Davoli, the American Cancer Society’s senior government relations director for New York. He says New York was the 13th state to enact comprehensive biomarker testing, and efforts are underway in all remaining states to enact similar laws.

One of the exciting things about the New York law is that it’s not a cancer bill, per se. “It’s actually disease agnostic,” Davoli explains.

“So, while biomarker testing is primarily being used in the treatment of cancer currently, there’s research being done in a whole host of different medical conditions—everything from mental health issues to heart disease, a lot of different neurological conditions, even Parkinson’s and ALS (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis), there’s research being done on biomarker testing and how it can be used for the treatment of those diseases.

“What this bill explicitly says is, if the science shows that biomarker testing can be used to treat that disease, then it should be covered by the law, and the testing should be covered by your insurance. u

MaryAnn Zuccaro loved music. She lost her battle with cancer when she was 61.

Her son, Ron Zuccaro, became a volunteer at the Upstate Cancer Center. Playing the baby grand piano in the atrium, he said, “gives me the opportunity to share the gift of music with cancer patients, their families and staff, and pays tribute to my parents for the values they taught me.”

He describes his time volunteering as rewarding, as people stop to thank him and to say hello.

His mother is the one who inspired him to play a musical instrument. On the 30th anniversary of her passing, he held a livestream performance on the cancer center’s Facebook page that raised $11,000 for the Upstate Foundation’s sixth annual Call In for Cancer. The event raises money to help the cancer center’s patients.

Anyone who is interested in fundraising for the cancer center may contact the Upstate Foundation at 315-464-4416.

BY JEANNE ALBANESE

Upstate Medical University earned the CEO Cancer Gold Standard reaccreditation for maintaining a strong commitment to the health of its employees and satisfying the comprehensive requirements of the Gold Standard, marking 10 years it has held the recognition.

The CEO Roundtable on Cancer, a nonprofit organization of health-minded CEOs, developed and administers the Gold Standard, an employee wellness framework based on taking concrete actions in five key areas to address cancer in the workplace.

To earn Gold Standard accreditation, a company must establish programs to reduce cancer risk by discouraging tobacco use and encouraging physical activity, healthy diet and nutrition; detect cancer at its earliest stages; and provide access to quality care, including the availability of clinical trials.

Jeanmarie Glasser and Jarrod Bagatell, MD, medical director of employee/student health, spearheaded the Cancer Gold Standard effort. Bagatell said Upstate has a long history of working toward a healthy campus, notably becoming the first smoke-free SUNY campus in 2005.

Through Upstate Well, Upstate offers programs and education that address physical, mental and spiritual health for students, staff and their families. These include weekly opportunities to participate in yoga, meditation, healthy eating and smoking cessation programs. Programs like Pet a Pooch deal with stress relief, while Monday Mile and Walk with A Doc encourage physical activity.

Upstate also offers many programs that last no more than 15 minutes, such as Tranquility Tuesdays, a short session of meditation and breathing that can be done in person or online, and Wellness Speaks: 10@10, a monthly series of 10-minute health, wellness and personal resiliency educational webinars. These short sessions make it easier to fit into busy schedules.

Mental health counseling, a 24/7 triage nurse-resourced hotline for any wellness or health issue, and paid time off for cancer screenings are also among the Upstate offerings.

“Our ideal is to provide excellent resources and make them accessible to everyone associated with Upstate,” Bagatell said. “We are providing opportunities for people to optimize their health and wellness while at work and beyond that. We support people to make Upstate a place you want to work, a place you want to be. I am incredibly proud of the efforts many people have made toward realizing this recognition.”

More than 200 private, nonprofit and government organizations have earned Gold Standard accreditation.

To learn about careers at Upstate, visit https://careers.upstate.edu. u

Platelets (also called thrombocytes) are cell fragments in the blood that are responsible for clotting.

“We’re finding more and more other things that platelets do, but the most important thing that we focus on is platelets can bind together with coagulation factors to make clots, so you can plug holes to stop bleeding,” explains Matthew Elkins, MD, PhD, director of hemapheresis and transfusion medicine at Upstate.

Hemapheresis is a procedure that separates and collects specific components of blood.

Platelets have a relatively short lifespan, a matter of a few weeks. Most of them don’t die of old age. We use about 7,000 to 10,000 platelets a day for random little breaks, for example, in our intestinal tract or when we brush our teeth and get a little bleeding in our gums.

What’s a healthy platelet count? The number of platelets circulating in our blood ranges from 150,000 to 300,000. When we’re injured, or anytime we have inflammation from infection, our body produces more platelets. So that set point changes, depending on what’s going on.

Our spleen and our bone marrow and lymph nodes sequester extra platelets. They’re like military reserves that can be called up immediately if needed, before we start training new soldiers.

Cancer and its treatments can impact platelet production.

Over their lifespan, platelets develop into structures that are sticky and can grasp one another to coagulate and stop bleeding. Photo credit: John W. Weisel, Rustem I. Litvinov and Chandrasekaran Nagaswami, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine.

“A lot of the treatments to try to attack cancer also hit other rapidly dividing cells, including bone marrow,” said Elkins. That’s where platelets are made.

This can cause bone marrow suppression, in which the bone marrow doesn’t make as many red blood cells, white blood cells and platelets.

“When platelets get really low, there is a risk that if you do have a break in one of your blood vessels and you start bleeding, you may not have enough to actually form a clot and stop bleeding,” Elkins said.

Also, when cancer spreads to the bone, it takes up space where the marrow would be, halting platelet production. And in blood cancers, bone marrow stem cells can become

affected by the cancer and either not produce any platelets or produce platelets that don’t work.

Chemotherapy that is toxic to the cells that line blood vessels may create breaks in the vessels that platelets need to plug, “so the number of platelets you use every day might actually go up, while your ability to make more platelets has gone down,” Elkins explained.

“If you can’t keep up with the need, you’re going to bleed. That’s where we have to come in and give platelet transfusions to help supplement.” In addition, medications are available to push the bone marrow to produce more platelets, but that takes place over days or weeks. u