Imagining a More Resilient Future for a Coastal Region

Halfway between Houston and New Orleans lies Southwest Louisiana. To the outside world, it’s known as the liquified natural gas capital of the world, or not well known at all. To the people who live there, it’s beloved for its friendly neighbors, stunning natural waterways, and rich Louisiana culture, music, and cuisine.

In 2020 and 2021, Southwest Louisiana was devastated by four major disasters. Hurricane Laura, one of the strongest storms to make landfall in state history, wreaked havoc with its damaging winds. Then came Hurricane Delta, Winter Storm Uri, severe tornadoes, and extensive flooding. Lake Charles became known as “the country’s most weatherbattered city.”

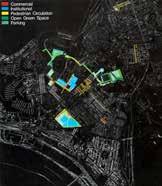

Funders and regional leaders knew something had to be done. The Community Foundation SWLA hired UDA to develop a 50-year Resilience Plan for two parishes, encompassing 3,030 square miles and 210,000 people. The invitation was to “Just Imagine” a brighter future. Throughout this process, the team listened to 7,300 ideas. Visions emerged for 11 catalytic projects that could be implemented over ten years — from a 23-mile bluegreen loop to revitalizing downtowns and enhancing coastal resilience.

Ready for change, project champions began implementing immediately. In the first year, there were groundbreakings and ribbon-cuttings. Partners secured a $40 million federal grant for mixed-income housing. A public bond passed with overwhelming support to fund eight catalytic projects. The region is collaborating with FEMA, the National Park Service, HUD, and the State of Louisiana to ensure it adapts and thrives, moving toward a more environmentally, socially, and economically resilient future.

Paradise, California

Rebuilding and Adapting a Town

The Town of Paradise was incorporated in 1979, evolving from nearly two centuries of informal development in the Sierra Nevada foothills. Its heritage is rooted in prospecting, logging, agriculture, and eventually the City of Chico’s rising cost of living. As orchards transformed into neighborhoods, the wildland-urban interface enveloped the town.

One resident said, “It was like camping every day.” And then one day the Camp Fire struck. Tragically, eighty-five residents lost their lives and virtually the entire town was burned to the ground, marking the worst wildfire in California history in terms of loss of life and property damage.

Mayor Jody Jones promised to rebuild, a commitment echoed by residents. This led to the pressing question, “How do we restore our town and make it more resistant to wildfires?” The answer lay in developing a tailored rebuilding strategy for Paradise. UDA was engaged by the Town Board to listen to residents, identify priorities, recommend ideas for hardening, and create the Long-Term Recovery Plan.

The plan provided the community with a blueprint for rebuilding. Today, Paradise is the fastest-growing community in California, boasting some of the country’s strictest building codes. Although the last chapter is yet to be written, both former and new residents are returning to “find the Town of Paradise to be all its name implies.”

Daybreak, Utah

Shaping

an Exemplary

New Community

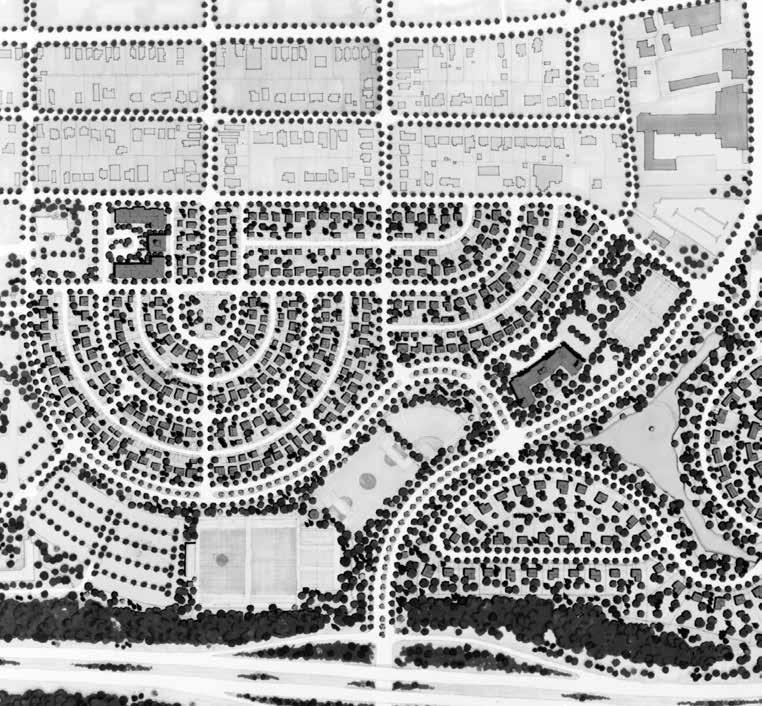

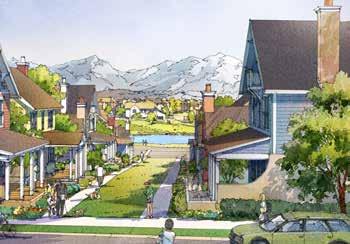

Envisioned as a new community of 60,000 people, Daybreak was conceived as a remarkable new city. Despite concern from production builders, the Daybreak leadership team aimed to capture the imagination of what a new community could be. The local builders were skeptical, saying: “This will never work.” Despite the best efforts of the development team, when the first homes came out of the ground, the development team realized they had a problem: The architecture was unremarkable.

Daybreak leadership called the UDA team for help in shaping more enchanting neighborhoods worthy of national recog-

nition. When UDA arrived, the local home builders were eager for guidance. The UDA team joined them in Salt Lake City, toured the historic districts, coordinated with builders, and assisted the development team in coalescing a vision for a new direction. UDA’s first Pattern Book gave the builders a clear vision and instructions on how to build great architecture, streets, and neighborhoods. After five Pattern Books, Daybreak has become a great city.

In the early 2020s, Daybreak was recognized as the nation’s fifth best-selling community, gaining national attention for design. Daybreak’s fifteen neighborhoods are visited by regional city councils, planning commissions, and national developers looking to learn how to build memorable cities on a broad scale. Daybreak has been recognized as one of the nation’s most innovative new communities.

Tampa, Florida

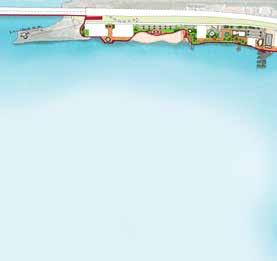

Putting the Waterfront on Water Street

Tampa is the 17th largest metro area in the U.S. The region’s heart is downtown Tampa, home to multiple world-class attractions such as the Florida Aquarium, Riverwalk, Glazer Children’s Museum, Straz Center Stage, Hixon Waterfront Park, and more. The largest venue is Amalie Arena, which has a seating capacity of over 20,000. Holding the city center back was the lack of vibrancy that comes from stitching these uses together.

Jeff Vinik, the owner of the Tampa Bay Lightning, envisioned a dynamic mixeduse district as a catalyst to energize downtown. His development company, Strategic Property Partners (SPP), acquired key sites surrounding the arena and charted a path forward.

SPP approached UDA to help design this urban entertainment district, create a memorable home for the Lightning, and make downtown Tampa a must-see destination. The UDA team positioned itself as the user — tracking the walk between the arena and cultural institutions, considering what one would see, hear, and experience along the way. Restaurants, cafes, parks, seating, and shade were choreographed. Parks and open space would frame future development blocks and support dense new development along Water Street.

Today, the Water Street Tampa development is fully underway. Sparkman Wharf was the first project of many out of the ground, with an integrated mix of office and spirited retail. Downtown is now known for its vibrant nightlife, family-friendly entertainment, beautiful waterfront, and parks — a world-class place on the Garrison Channel waterfront.

Daybreak, Utah

Planning a

New Downtown

Since the introduction of the Interstate Highway System, America has shifted its focus away from building urban downtowns. Instead, we have prioritized expanding our existing cities with automobile-oriented sprawl. While these areas are characterized by intense development, they often lack the remarkable experiences found in walkable downtowns.

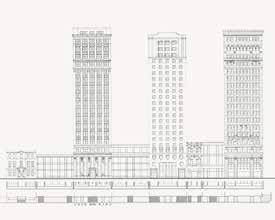

The Daybreak Development team envisioned a downtown area that would be equal in size to Salt Lake City’s center, directly connected by three transit stops. Echoing classic cities, residents would have the option to board a streetcar and

travel to another downtown area. Their goal was to create delightful opportunities that would inspire growth and investment, resulting in a beautiful place for future generations to enjoy.

UDA collaborated with the Larry H. Miller Company (LHM) and their consultants to design the urban experience. And like all cities, this was a team effort. UDA assisted in developing the shape of the urban environment, including office, residential, and retail districts, all connected by a strong pedestrian network. The centerpiece is a new minor league baseball stadium anchoring the green network of parks and trails. With over 5,000 homes, 450,000 square feet of retail, millions of square feet of office space, parks, and trails, Daybreak’s downtown will deliver urban life and demonstrate the value of downtowns in today’s development landscape.

Huntsville, Alabama

A new Urban Center for Huntsville

Huntsville has been a high-tech hub for aerospace, defense, and advanced manufacturing innovation since the 1950s. In recent decades, it has evolved into one of the fastest-growing domestic employment hubs for highly skilled workers. Most of these jobs are in suburban office parks that circle the city. Workers new to Huntsville have long wanted more excitement and a place to socialize — a vibrant urban life. Local leadership acknowledged that this missing element negatively impacted recruiting.

The City of Huntsville and RCP Companies (RCP) saw this weakness as an opportunity and formed a public-private partnership to create the destination

residents coveted. They identified a defunct shopping mall site as the preferred location, and RCP purchased the property. UDA was selected to reimagine the 68 acres as MidCity, a new mixed-use walkable urban center. UDA developed the master plan, designed concept architecture, and prioritized placemaking to ensure a timeless place. The resulting buildout reflects influences from the area’s early industrial and agricultural production economy.

As a corollary to the successful physical environment, RCP is integrating robust education/training facilities and programs centered on music production, music and film technology, culinary science, and hospitality.

Huntsville residents have responded to MidCity with enthusiasm. Construction continues to advance at a breathtaking pace. The current most popular attraction is the 8,000-capacity Orion Theater, which opened in 2022 with national fanfare as the top outdoor venue in the country.

Reimagining

Main Street

In 2019, a developer constructed the largest building on Main Street, sparking criticism among locals. The fallout triggered a series of events aimed at reimagining the central riverfront. The Town Board commissioned UDA to engage with residents and develop prescriptive design guidelines, which also included planning a connection between Main Riverhead, New York

Street and the Peconic River with a sea level rise mitigation strategy. The recommendations encouraged the town to acquire vacant buildings to create a central gathering space and public plaza.

Like many American towns, the Town of Riverhead had a much-loved historic Main Street that needed a refresh. Pockets of vacant buildings, aging streetscapes, and a disconnect with the adjacent waterfront stood out as weaknesses in a place with high potential. Residents longed for a vibrant connection between Main Street and the tidal Peconic River.

The next phase involved creating a Central Riverfront Activation Plan that solidified this vision. Since then, the town has secured over $35 million in State and Federal grants, along with private donations, to bring the vision to life. These funds are being used to construct a town square, civic plaza, adaptive playground, amphitheater, parking garage, and improved streetscapes. Additionally, private developers have proposed various mixed-use buildings, including a hotel, condominiums, and retail uses, all clustered around the square.

Today, the town is actively working to implement this vision while seeking additional grant funding for further amenities and enhanced sea level rise mitigation efforts.

Healing a City Neighborhood

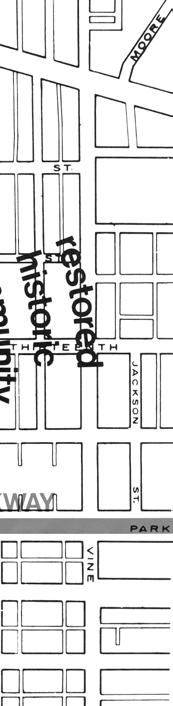

Every day, Rochester residents longed for the expressway to be demolished and downtown Rochester to be reconnected to adjacent historic neighborhoods. And then, one day, the city announced the Inner Loop East Transformation Project, reclaiming about six acres of land by replacing the expressway with an urban street. This initiative prompted the city to issue a Request for Proposals (RFP) for infill development proposals. Rochester, New York

Decades ago, a Kodak heiress generously donated her home and toy collection, which became the Strong Museum of Play (Strong). As the museum flourished, it outgrew its original location and was relocated to just inside the Rochester Inner Loop. The new site, however, was pinned against an elevated expressway.

In response, Strong assembled a team consisting of Konar Properties, Indus Hospitality, CJS Architects, and UDA as the master planning and design lead. The team’s plan called for transforming the isolated museum into the “Neighborhood of Play.” The vision utilized the reclaimed inner loop sites and surface parking lots for infill development that would stitch downtown and the Park Avenue neighborhood back together. Elements of the plan included a new hotel, a main street, a public plaza, apartments, restaurants, retail, a parking garage, and pedestrian and bike facilities, along with a major museum expansion featuring a new entry hall, restaurant, museum store, and the World Video Hall of Fame.

The development team won the RFP and Strong was subsequently awarded $20 million to support its expansion.

By 2023, the Neighborhood of Play was completed. It is now regarded as a model for cities that have been damaged by freeways.

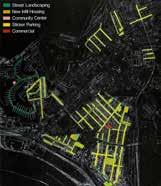

Transforming Neighborhoods from Disinvestment to Choice

In the 1930s, the U.S. government developed the first public housing. Segregated from the onset, public housing eventually had the devastating consequence of concentrating poverty and perpetuating disinvestment and racial segregation within neighborhoods.

HOPE VI represented the first evolution toward transforming public housing from projects back into neighborhoods and homes. While it succeeded in building more dignified housing, it fell short in addressing issues of neighborhood investment and supporting residents’ economic, health, and educational potential. In 2010, the Choice Neighborhoods Initiative (CNI)

launched, offering a more holistic framework for neighborhood transformation.

UDA’s process of Listening, Testing, and Deciding empowered residents trapped in downward economic spirals. UDA helped to bring cities, housing authorities, developers, non-profits, and residents together to develop shared visions. Soon after, funding to implement followed. New mixed-income homes came out of the ground and families started to succeed in ways they hadn’t experienced before.

UDA has helped 14 communities across the country win $30 to $50 million HUD

CNI Implementation Grants and five communities develop Transformation Plans through CNI Planning Grants.

UDA’s efforts have helped to deliver over $4 billion in investments for neighborhoods and families. Seeing this has confirmed what we know to be true — design is a powerful tool for transforming the built environment and altering the economic trajectories of neighborhoods and individuals.

© Craig Thompson

Daybreak, Utah

Transforming Homebuilders into Neighborhood-Builders

Over 1.5 million new homes are permitted each year. According to the National Association of Homebuilders, only 2% are designed by architects. Based on these statistics, few people benefit from life in a thoughtfully designed home and community. Through engaging homebuilders since the 1990s, UDA has been focused on addressing these issues and expanding access to high-quality design of new communities.

In Utah, “We have to take you back to the airport” was how Destination Homes responded to UDA’s promise to design high-density townhomes and apartments. Another local builder, Sego Homes, may have felt something similar

when UDA began working with their team. Even though a change of this magnitude substantially impacts nearly every aspect of their business, these builders were willing to try.

The first work emerged in the new community of Daybreak under the guidance of UDA’s Pattern Books. UDA’s designs instilled the timeless characteristics of quality neighborhood architecture: simple massing, improved proportions, and the addition of livable elements such as porches and terraces. As sales and popularity increased, the builders thirsted to offer more high-density types and create their own new urban communities, earning them local and national recognition.

Through planning and architecture with these two builders and others, UDA has designed over 4,800 homes for nearly 15,000 people in Utah alone, consistent with UDA’s mission to design high-quality urban environments.

2024–

Cities are continually evolving, and UDA is evolving with them. As we look ahead to the next decade, we will focus our efforts on building consensus and developing solutions to the most pressing challenges facing urban areas.

Each city, town, and village faces its own unique set of obstacles as they grow and change. As committed problem solvers dedicated to improving the human condition, we are here to help.

Our mission as urban designers is to honor the individuality and authenticity of place. We realize that every city and every neighborhood has its character and its sense of what it inherits. It also has a sense of how it wants its future to evolve.

David Lewis

Images read top left to bottom right

1964–1974

David Lewis, FAIA

Mack Community Center, Ann Arbor, MI

Democracy and Design in Action

Gananda, NY

Great High Schools, Pittsburgh, PA

Great High Schools, Pittsburgh, PA

Human Resources Center, Pontiac, MI

Mack Community Center, Ann Arbor, MI

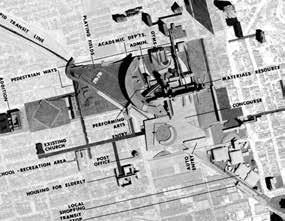

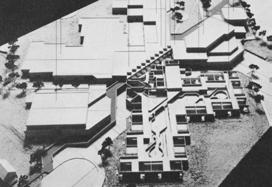

1974–1984

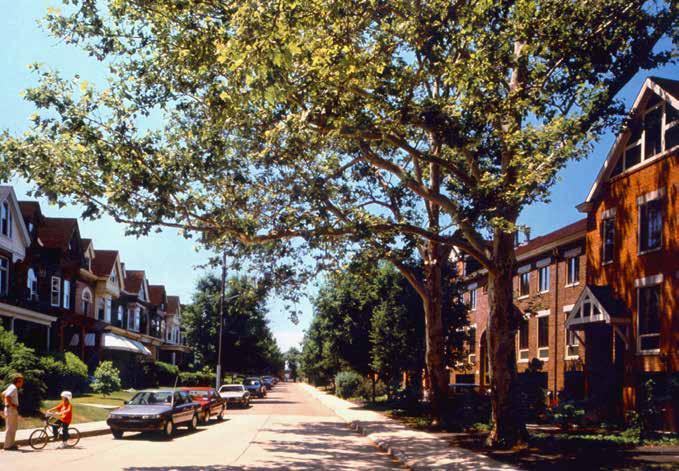

Queensgate II Town Center, Cincinnati, OH

Village of Shadyside, Pittsburgh, PA

“Wall Street District,” Pittsburgh, PA

“Wall Street District,” Pittsburgh, PA

The Oakland Plan, Pittsburgh, PA

The Oakland Plan, Pittsburgh, PA

Confluences, UDA Anniversary

York Design Guidelines, York, PA

1984–1994

Middle Towne Arch, Norfolk, VA

Celebration Pattern Book, Celebration, FL

Crawford Square, Pittsburgh, PA

Middle Towne Arch, Norfolk, VA

Diggs Town, Norfolk, VA

Jewish Community Center, Pittsburgh, PA

Cary Street, Richmond, VA

1994–2004

Ray Gindroz, FAIA

Broadway Overlook, Baltimore, MD

North Shore, Pittsburgh, PA

Baxter, Fort Mill, SC

University of California at Santa Barbara, Santa Barbara, CA

East Garrison, Monterey County, CA

Cincinnati Riverfront, Cincinnati, OH

2004–2014

Ellon, AB, Scotland

South of Broadway, Nashville, TN

New Moscow Federal District, Moscow, Russia

Ludhiana Township, Punjab, India

South Lake Union, Seattle, WA

West Don Lands, Toronto, Canada

Storrs Town Center, Storrs, CT

2014–2024

Pearson Ranch, Austin, TX

Cypress Village, Vancouver, Canada