18 minute read

AN INTRODUCTION TO UDA

This book presents a summary of the work of Urban Design Associates (UDA), founded in 1964 in Pittsburgh.

While most of the architecture profession designs buildings, the architects at UDA have always considered more than one scale, including the scale of the block, the neighborhood, the town, and the city. This book presents designs for urban neighborhoods, new towns and cities, legacy places, downtowns, and settlements seeking greater resiliency. These projects represent the ambitions of visionary developers, municipal planners, elected officials, institutions, and foundations. The work manifests itself in different forms depending on the project and approach to implementation. Some are vision plans for cities seeking to define public policy while others are master plans for private developers. Some projects feature building designs for new neighborhoods based on local architectural patterns and traditions. Others are pattern books, highly visual design guidelines for architects, builders, and homeowners building in sensitive places. Taken as a whole, this book demonstrates a tremendous range of issues and a variety of solutions addressed in the practice of urban design at UDA.

Advertisement

FOUNDING OF URBAN DESIGN ASSOCIATES

David Lewis, FAIA

Our towns and cities are the physical languages of who we are. They tell us about our history and our values.

When we travel to a town in a foreign county for the first time, we might sit in a café on a public square and quietly watch the scene in front of us while sipping a cup of coffee or a glass of white wine. Our eyes will explore the quality and scale of the buildings around us that are unfamiliar and intriguing, and we might ruminate about the layering of past cultures that survive the town’s arcades and doorways and its balconies and towers.

We will watch how people interact with each other in the noisy complexity of the city they take for granted. Our ears will explore the cadences of voices, and the city will come alive for us through the rhythms of its life.

We might indeed ruminate about how our cities also gained their form over time, and how rapidly they have changed during our lifetime, and how we might explain these changes to foreign visitors.

Perhaps we would begin by recounting how, before the automobile, urban neighborhoods in our larger cities were essentially small towns within the city. Their antecedents were European towns and villages. Their dimensions were designed for pedestrians. Within a circumference of 10-15 minutes of walking time, each urban neighborhood had a shopping street, a park, a library, schools, and places of worship.

But the dominant uniformity of these urban grids is decidedly American. We might speak about the experience of flying over the expanse of our country and seeing our rural areas laid out in all directions as a rectilinear grid and how our towns can be seen as urban grids within the agricultural grid.

And within the towns, residential streets were laid out as rectangular blocks, with sidewalks and shade trees and standard lots for sequences of “pattern book” houses, each with a front porch and a back yard. Neighbors knew each other and their children, and public transit connected neighborhoods to the city center and workplaces.

Each neighborhood had its own ethnic character, influenced by the cultures that immigrants brought with them — churches, synagogues, shops, restaurants and markets, and even their own languages, festivals, and schools — characteristics that are still powerful to this day.

But we might then recount to our visitor how in the 1950s and 60s radial highways were built from the centers of our cities into the surrounding farmlands, and how these highways generated residential suburbs, shopping malls, and office parks. We might also explain how, in our city center, tall office towers were

built of steel, aluminum, and glass — centers that in some cities are still referred to as “island of excellence” — resulting in those radial highways being clogged morning and evening by suburban commuters in automobiles at rush hours.

And we would also recount how some of our larger inner-city neighborhoods, drained by outward suburban migration, became low-income segregated communities with deteriorating residential streets and shops. We might also explain that the civil rights movement is continuing to evolve these inner-city neighborhoods from the fierce confrontations of the ‘60s and ‘70s into urban integration.

But we could also speculate that from the generation to generation our cities resemble tides that flow out and then flow in again. A new generation is beginning to discover the virtues of these older neighborhoods in our towns and cities and the evolving neighborhoods in traditions with the inputs and insight of new cultural initiatives.

Every neighborhood has its own character. As urban designers, it is our task to enfranchise old and new voices together and to infuse our urban heritage and traditions with the inputs and insight of new cultural energies.

We learned our techniques during the civil rights struggle of the ‘50s and ‘60s. Our approach at that time was simple and direct, and we have not changed. We need to look at every urban situation with the fresh eyes of innocence. We need to hear and see what heritage is trying to tell us and to understand at first hand the voices and ambitions of the unheard.

As urban designers, we need to bear in mind that while history deals with past tradition, it is the bridge to the future. Every city and every neighbor has its character and its sense of what it inherits. It also has a sense of how it wants its future to evolve.

Our mission as urban designers is to develop public and private sector recommendations based on the people themselves, their sense of living heritage, and their goals for the generation to come.

URBANISM AND THE PRACTICE OF URBAN DESIGN

Raymond Gindroz, FAIA

When we started our practice in 1964, very few people knew what urban design was. Some described it as “a bridge between planning and architecture”, others thought it was simply architecture on a very large scale. Academic articles trying to define it appeared in journals. There was even a contest to find the best definition.

So, it was not easy starting a practice that provided a service that was virtually unknown. People usually don’t want to pay for a service they didn’t know existed and therefore didn’t know they needed.

Over time, we learned that urban design is the only discipline that brings together all the aspects of city design to create whole places. To do so, we are facilitators and bridge builders who bring people together around a shared vision. This understanding began for us with David Lewis’ Master’s degree program at Carnegie Institute of Technology (now Carnegie Mellon University).

When David came to Pittsburgh to chair the urban design program, he created a new approach to teaching which he later called the Urban Lab. Students went out into the neighborhoods and business areas of Pittsburgh to meet with residents to learn what aspects of their community were working for them and what were not. To help students understand the technical aspects of city design, David assembled an interdisciplinary faculty, including an economist, a developer, a social worker and sociologist, a traffic planner and a city planner.

From the beginning it was clear that urban design could provide the design framework for all of these specialists to work together. Working with interdisciplinary teams and involving residents continue to be the working methods of the firm.

Our first commission further helped us to understand the role of urban designers. It came about when the Superintendent of Pittsburgh Public Schools asked David to help in conforming to the Supreme Court ruling that called for integrating all public schools. Our task was to find ways of locating and designing schools as a means of achieving racially integrated schools. Pittsburgh is a city of steep hills and valleys that separate neighborhoods from each other. Most of these were either all white or all black. By analyzing the physical and social structure of the city, we hoped to find locations that were on common ground between neighborhoods.

And so, we began Urban Design Associates with an urban design project, funded by the Ford Foundation, that dealt with the major social crisis of the time. Finding the relationship between social issues and the physical form of cities became the central mission of our newborn practice.

The best way to define urban design is to describe the key services that an urban design practice can provide:

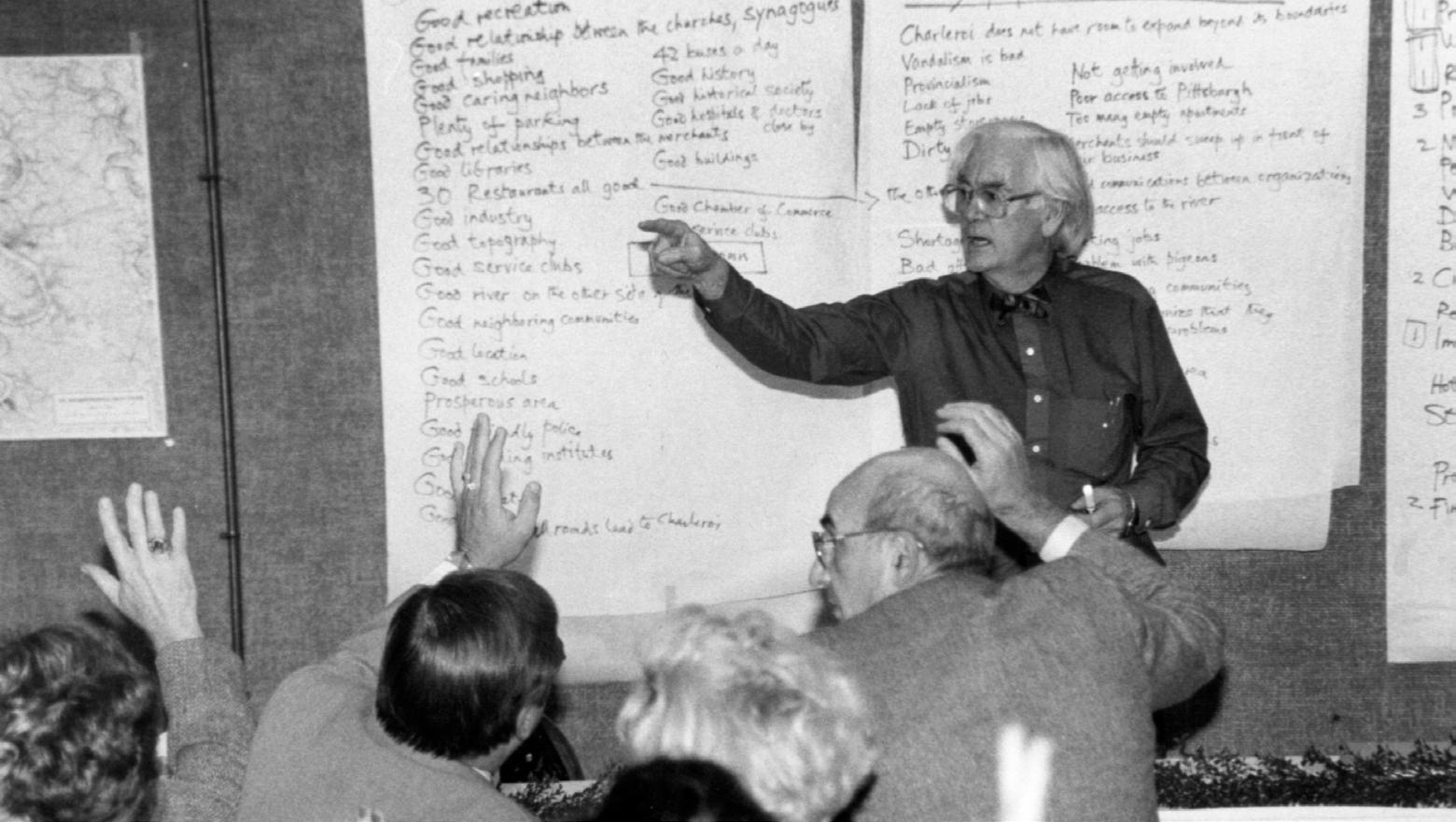

Conducting Public Engagement Processes: In the early years, we quickly learned that we could not find solutions to difficult problems during the design process without genuine, personal engagement with people in the com- munity. We learned what people treasured about their neighborhoods, what they disliked and feared about them and what dreams and aspirations they had for the future. Designs were developed in direct response to their answers. The most important design chal- lenge was the design of the process itself. We developed a process with three steps: (1) Figuring out what is going on, (2) Trying out some ideas, and (3) Deciding what to do. We have found that when followed rigorously, the process never fails. Our motto is to always “trust the process.”

Leading Charrettes: In order to cope with the large number of issues and broad range of people involved in the design process, we organize the process around one or more public working sessions with opportunities for all participants to work with us. It is the most efficient way to deal with complex issues and reach consensus. Participants know that deci- sions need to be made and consensus reached in a short time period. If the process drags on, consensus is lost and projects fail.

Urban Design Analyses: The urban designer distills what the people have said and analyzes the city to identify the aspects of its physical form that create the problems identified by the people. To help understand the complex physical form of cities, we created a method of analysis which we call UDA X-Rays®. Each element of the community is drawn separately. For example, the pattern of streets or the pat- tern of residential development or the physical barriers between parts of the community are “diagnosed” to identify problems. The results are combined in a diagram of good things and bad things. These diagrams then become a means of communicating the issues with the general public, with political leaders and with the various stakeholders involved, such as developers, traffic engineers, business leaders, and city officials.

Visualization: In order to reach consensus among a broad group of people, it is critical that all participants have a clear understanding of the proposed design. Three dimensional drawings that accurately describe the spaces created in the design are essential. Preparing these in the charrettes provides an opportunity for participants to make suggestions and influence the image’s final form.

Visions: Urban designers’ main responsibility is to create a vision for the future based on all that is learned in the process. The vision needs to be meaningful to all the participants and to those who will implement it. For example, the vision of a master plan for the University of California at Santa Barbara was a series of grand promenades with vistas to both the ocean and the mountains. This simple but large scale vision established the footprint for future buildings and the form of public open space. In the 13 years since the plan was approved, the University has made sure that even small scale projects follow this plan and that no construction blocks the grand vistas.

Architectural Design: In the early years of our practice when urban design projects were few and far between, 60% of our work was architecture. Although we ultimately stopped doing full-service architecture, we found that a deep understanding of the way buildings are built and function is essential to good urban design. In later years, the firm provides architectural design services, often on key buildings to set standards for others to follow. The character and quality of the buildings that create the spaces of a city are critical to its success.

Design Guidelines and Pattern Books: The majority of buildings in the U.S. are built by production builders with little time spent on the design. The building booms of 19th-century Britain and America used Pattern Books to ensure consistently high-quality design that supports the overall vision of the plan. We found that a modern version of the Pattern Book helped developers and cities achieve a higher quality of design.

Massing and Facade Composition

Manor House Apartments

The M anor House Apartment building is an elegant residence at the edge of town with units that enjoy views of the surrounding wooded preserve. The four and a half story building features an entrance court and units and picturesque massing with an animated roofscape, dormers, towers and chimneys. Paired with the Stables, the ensemble resembles a converted estate. The Stables

The Stables is an assembly of rowhouse units organized around an interior courtyard. Living spaces for each unit are oriented to the surrounding forest. The central court, once for horses, is now a motor court with garages behind stable doors wrapping around the courtyard. The units vary in height from one-and-a-half- to two-and-a-half-story units. The units are unique because they are designed as converted stable lofts. The Park Tower

The tall apartment building is designed in the great tradition of elegant ‘park address’ apartment houses, similar to precedents found along Chicago’s North Shore, New York’s Central Park, and Boston’s Charles River. The building is oriented to maximize views and features exclusive penthouse units. The apartments feature large balconies and terraces that overlook the woodlands.

© 2007 u r ba n d esi gn asso c i at es

The Rise Architecture

addr esses

b

18

A recent experience illustrated the essential ingredients of an urban design practice. A city had been trying for years to redevelop a 200- acre area adjacent to downtown that currently has nearly 2,000 units of public housing and is subject to flooding. A vision was developed with the community two years ago and a successful application for Federal funding was submitted early this year. In order to secure additional funding, the detailed design of one aspect, the streets, began before all other aspects were started. This led to conflicts among the various disciplines and stakeholders. We held a technical charrette in which the leader of each discipline stated 5-8 key goals. They all listened to each other. Then four teams, one for each discipline, began work in the same

work area. Periodic reviews provided a forum for debate and resolution of conflicts. The designs for key areas were illustrated in three dimensional images. By the end of three days, a clear direction was agreed to by all parties and the vision became clear. Urban designers led and coordinated the process. This is the essence of urban design in practice.

DRAWING PLACES

Paul Ostergaard, FAIA, AoU

Drawing is the language of architects and urban designers, distinguishing these professions from all others. Understood by the viewer regardless of who they are and what language they speak, drawings can explain complex physical environments more easily than words. Perhaps most importantly, drawings have the power to inspire action because they place a picture in the minds of those who want change, who want to improve their environment. Those pictures linger in the mind longer than numbers, sentences, and paragraphs.

UDA places a high value on drawing as both a design and a communication skill. Because of this, our staff of architects has remarkable drawing skills that enable them to think, design, and communicate effectively. We are taught to translate the path our eyes take across an object through our mind and into our hand by moving a pencil across a piece of paper. With continual practice, we develop muscle memory of drawing buildings and spaces we admire, and later in practice, we use this muscle memory to draw new places. An example of this is the lifelong research of Ray Gindroz, as seen with his line drawings of urban spaces in Italy, France, and other places he has visited. His lines create a depiction of urban space by emphasizing those features that most interest him and offer a lesson for others. He has applied these lessons to his urban design projects. Perspectives are the most legible drawings to the layman because they immediately convey the character of a proposal and are less abstract than orthogonal projections such as plans and elevations. Perspectives constructed properly allow the viewer to occupy the place as if it was real. Many perspectives are taken at eye level to give the viewer a sense of being inside an urban space. These views are often intended to convey the room-like nature of city places and capture key vistas that make them memorable. They convey the importance of buildings and landscapes as components of those places, providing guidance for their design later on.

Perspectives are not just a presentation tool — the staff at UDA designs in perspective, adjusting buildings and landscape to maximum benefit. Computer modeling has greatly improved our ability to manipulate urban space. Before the personal computer, we would manually construct one and two-point perspectives, a laborious process essentially unchanged since the 15th century. We now use 3D modeling as an underlay to construct hand drawings on trace. The drawings are then elaborated by the designers, informing changes to the computer model. This is an iterative process of design combining an ancient art form with modern technology. Hand drawings are scanned and rendered with color to create vivid depictions of a future place. They are used in presentations to communicate the

Ray Gindroz

Bill Durkee Paul Ostergaard

essential qualities of the proposed physical environment and used as early marketing imagery. We typically eschew computer-gen- erated imagery early in the design process be- cause we wish to emphasize certain planning principles and concepts, most easily conveyed by hand drawing.

Aerial views are effective at explaining the proposed urban form of a city. Views from the air not only show the organization of urban space, as in a plan of the city, but convey the character and scale given to those spaces by the buildings that create them. By empha- sizing particular design features, the aerial perspective can be an extremely effective tool for describing urban planning issues that are broad in scope and impossible to see from the ground. The advantage of hand drawing over computer-generated photorealism is the ability to emphasize aspects of the urban form with line and color that are most important to the project. Aerial photos and photorealism show everything. Hand drawings have the immense power of focusing the message as a diagram, often of great beauty.

The planning charrette is live theater. We rely on our previous experience with charrettes to proceed with a degree of comfort. How- ever, we go into every charrette with some uncertainty. We try to imagine a solution before drawing, but no progress can be made until we begin to draw. Once we are ready, we follow the path our drawings take us on. We think using drawing as our language allows our client to see ideas unfold before them that were never contemplated. Citizens who join us in charrette love to sit beside our designers and illustrator and watch, sometimes offering their ideas. They see their ideas drawn on paper, and later if they have merit, their ideas embedded in drawings are presented to the community.

Drawing at UDA has evolved over the years. The ink line has always been our preferred media, but the use of line drawings has changed. Early on Bill Durkee and Paul Ostergaard drew pen and ink perspectives drawings that stood on their own without color rendering. To provide tonal value, these drawings were hatched in the manner of an etcher or engraver. They were inspired by the line drawings of Bertram Goodhue and the etchings of Giorgio Morandi. Early attempts to provide color with marker were mostly fail- ures. Pencil was a more subtle material for col- or but would not reproduce well. David Csont, a trained illustrator, combined line drawing with watercolor and most recently digital coloring that dramatically advanced the art of drawing in our firm and in the profession. These new techniques are also used by the staff to render plans, elevations, and sections. Currently, we are exploring the combination of hand drawing and 3D modeling in the pro- cess of urban design. Early perspective draw- ings illustrate an urban place as in a movie set design storyboard. Then computer-generated modeling enables us to create film segments that move us through a place, thereby illus- trating how the parts and pieces of urbanism are combined to create places. Fully rendered hand drawings capture moments in the jour- ney as an image that can be used in print and digital media.

David Csont