,„^»'— in d Si i—i CO CO CO \ < 0 r d S w <r N d § w w ^

UTAH HISTORICAL QUARTERLY (ISSN 0042-143X)

EDITORIAL STAFF

MAX J. EVANS, Editor

STANFORD J LAYTON, Managing Editor

KRISTEN S. ROGERS, Associate Editor

ALLAN KENT POWELL, Book Review Editor

ADVISORY BOARD O F EDITORS

AUDREY M GODFREY, Logan, 2000

LEE ANN KREUTZER, Torrey, 2000

ROBERT S MCPHERSON, Blanding, 2001

MIRIAM B. MURPHY, Murray, 2000

ANTONETTE CHAMBERS NOBLE, Cora, WY, 1999

RICHARD C. ROBERTS, Ogden, 2001

JANET BURTON SEEGMILLER, Cedar City,1999

GARY TOPPING, Salt Lake City,1999

RICHARD S VAN WAGONER, Lehi, 2001

Utah Historical Quarterly was established in 1928to publish articles, documents, and reviews contributing to knowledge of Utah's history The Quarterly is published four times a year by the Utah State Historical Society, 300 Rio Grande, Salt Lake City, Utah 84101 Phone (801) 533-3500 for membership and publications information. Members of the Society receive the Quarterly, Beehive History, Utah Preservation, and thebimonthly Newsletterupon payment of the annual dues: individual, $20.00; institution, $20.00; student and senior citizen (age sixty-five or over), $15.00; contributing, $25.00; sustaining, $35.00; patron, $50.00; business, $100.00

Materials for publication should be submitted in duplicate, typed double-space, with footnotes at the end Authors are encouraged to submit material in a computer-readable form, on 3J4 inch MSDOS or PC-DOS diskettes, standard ASCII text file. For additional information on requirements contact the managing editor Articles and book reviews represent the views of the authors and are not necessarily those of the Utah State Historical Society.

Periodicals postage is paid at Salt Lake City, Utah

POSTMASTER: Send address change to Utah Historical Quarterly, 300 Rio Grande, Salt Lake City, Utah 84101

UTAH STATE HISTORICAL SOC I ETT I

HISTORICA

Contents SUMMER 1999 \ VOLUME 67 \ NUMBER 3 IN THIS ISSUE 195 OF PAPERS AND PERCEPTION: UTES AND NAVAJOS IN JOURNALISTIC MEDIA, 1900-1930 ROBERT S. MCPHERSON 196 "REDEEMING" THE INDIAN: THE ENSLAVEMENT OF INDIAN CHILDREN IN NEW MEXICO AND UTAH SONDRA JONES 220 THE ARROWHEAD TRAILS HIGHWAY: THE BEGINNINGS OF UTAH'S OTHER ROUTE TO THE PACIFIC COAST EDWARD LEO LYMAN 242 SAMUEL W TAYLOR: TALENTED NATIVE SON JEAN R. PAULSON 265 BOOKREVIEWS 285 BOOKNOTICES 294 THE COVER: Navajo Indian, USHS collections. © Copyright 1999 Utah State Historical Society

L QUARTERL Y

HAROLD SCHINDLER In Another Time: Sketches of Utah History First Published in the Salt Lake Tribune JEFFREY NICHOLS 285

DAN ERICKSON. "AS a Thief in the Night": The Mormon Questfor Millennial Deliverance . . .KENNETH W GODFREY 286

JEAN BICKMORE WHITE The Utah State Constitution: A Reference Guide .MICHAEL E CHRISTENSEN 288

PARKER M NIELSON The Dispossessed: Cultural Genocide of the MixedBlood Utes, an Advocate's Chronicle JOH N D BARTON 289

ROBERT H KELLER AND MICHAEL F TUREK American Indians and National Parks LEE ANN KREUTZER 290

JAMES P. RONDA, ed. Voyages ofDiscovery: Essays on the Lewis and Clark Expedition TODD I. BERENS 291

H.JACKSON CLARK Glass Plates and Wagon Ruts: Images of the Southwest by Lisle Updike and William

Pennington DREW ROSS 292

Books reviewed

In this issue

The erudite Henry Adams, writing in 1895 as a member of the first generation of professional historians in America, voiced concern over history's reputation as an objective discipline. Noting that every person carries a predilection for error in the observation of basic facts behind an event and that this tendency toward error is compounded by people who write about that event, Adams then pointed to the possibility of errors within the facts themselves (being correctly stated but still leading to wrong conclusions) and to the reader's personal errors "The sum of such inevitable errors must be considerable," he concluded pessimistically

The first two selections in this issue stand as excellent examples of historians meeting the challenges of these errors and biases head-on and proving, in the words ofJ H Hexter, that indeed "truth about history is not only attainable but is regularly attained." The first article sorts through the pitfalls of yellowjournalism in early nineteenth-century Utah to analyze differences in popular perceptions of the Utes and Navajos The second treats the emotionally charged question, complicated by many conflicting sources, of child enslavement within two very distinctive frontier cultures. Both articles succeed admirably in elucidating the historical record and in vindicating the craft of history.

The last two selections in this issue present similar challenges. Here the difficulty is not with unreliable or incomplete sources but rather with sifting through the many existing ones, assigning relative value to them, and making an accurate assessment. Deciding on a southern or a northern route for Utah's primary highway to California was not a simple matter of cost analysis, miles, and topography in the 1920s; regional boosterism, political muscle, and personalities all added to the mix and need to be explained by a historian. Similarly, describing the busy life of one of Utah's favorite literary sons and summing up his niche also requires patience and reasoned judgment in dealing with the mountain of facts, anecdotes, testimony, and creations left behind Again, in both cases, we see historians rising to the occasion in splendid fashion Henry Adams, who died a decade before Utah Historical Quarterly was founded, can rest in peace Historians have thrived on his challenge

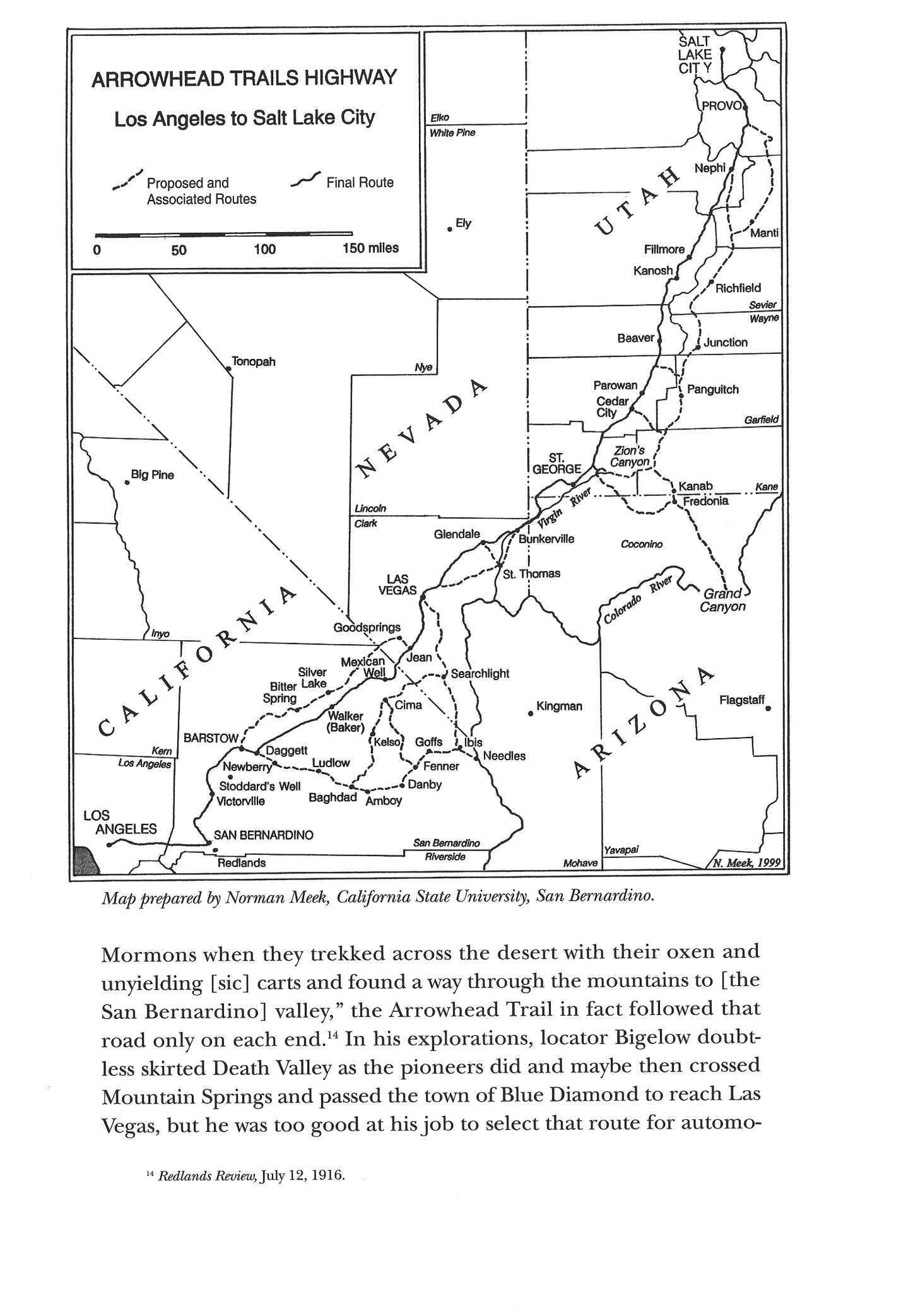

Automobile Club of Southern California sign-painting truck, probably in Utah (sign on hill advertises a business on Auto Row, Salt Lake City). Photo courtesy of auto club.

Automobile Club of Southern California sign-painting truck, probably in Utah (sign on hill advertises a business on Auto Row, Salt Lake City). Photo courtesy of auto club.

Of Papers and Perception: Utes and Navajos in Journalistic Media, 1900-1930

BY ROBERT s MCPHERSO N

BY ROBERT s MCPHERSO N

NEWSPAPERS TELL STORIES. In their most basic form, they speak of current events of public interest in a factual manner. Or so it seems. Yet just deciding what events should be put in the paper, what topics "sell,"

Photos: Ute prisoners and their captors at Thompson Springs on their way to Salt Lake City, 1915. Left to right: Indian agent Lorenzo Creel, A. B. Apperson (D&RG superintendent), General Hugh Scott, SheriffAquila Nebeker, Poke, Jess Posey, Posey, Tse-ne-gat, unknown; USHS collections. Newspaper headlines, 1915; courtesy of author.

.«4 r "* " ' ' - - -nu Pdt." whm'relmJ to •""" r\ \ « ' INDIANS SURRENDERS fc#^T0 ™ SC0TTm* iiv *V i > W M Reul arrived Tw'ULIi ASlfl B >ll * w \ GEN. SCOTT ON ¥ US A \ WAY TO BLUFF-

^.ec©it*-AV * ate \ooW Tiief of Staff of United States^Army iog Will Attemp t Peaceful Settlement UoVl C° t t Coeft»' doe Ae, Wit h Renegade JRitrtes bklia .W'-° " e0^ v '-,Vajhi ?g ton D C March ^.-Brigadier-G^ra!', ( - 1 ,„," S '°' 1 i' A »'• ..^plC'X chief of stuff of the LnilKi Staifti army left herv '''"'fly/,

Robert McPherson teaches history at the College of Eastern Utah-San Juan Campus and is on the editorial advisory board of Utah Historical Quarterly. He expresses thanks to the Utah Humanities Council for providing him with the Albert J Colton Fellowship, which made this research possible

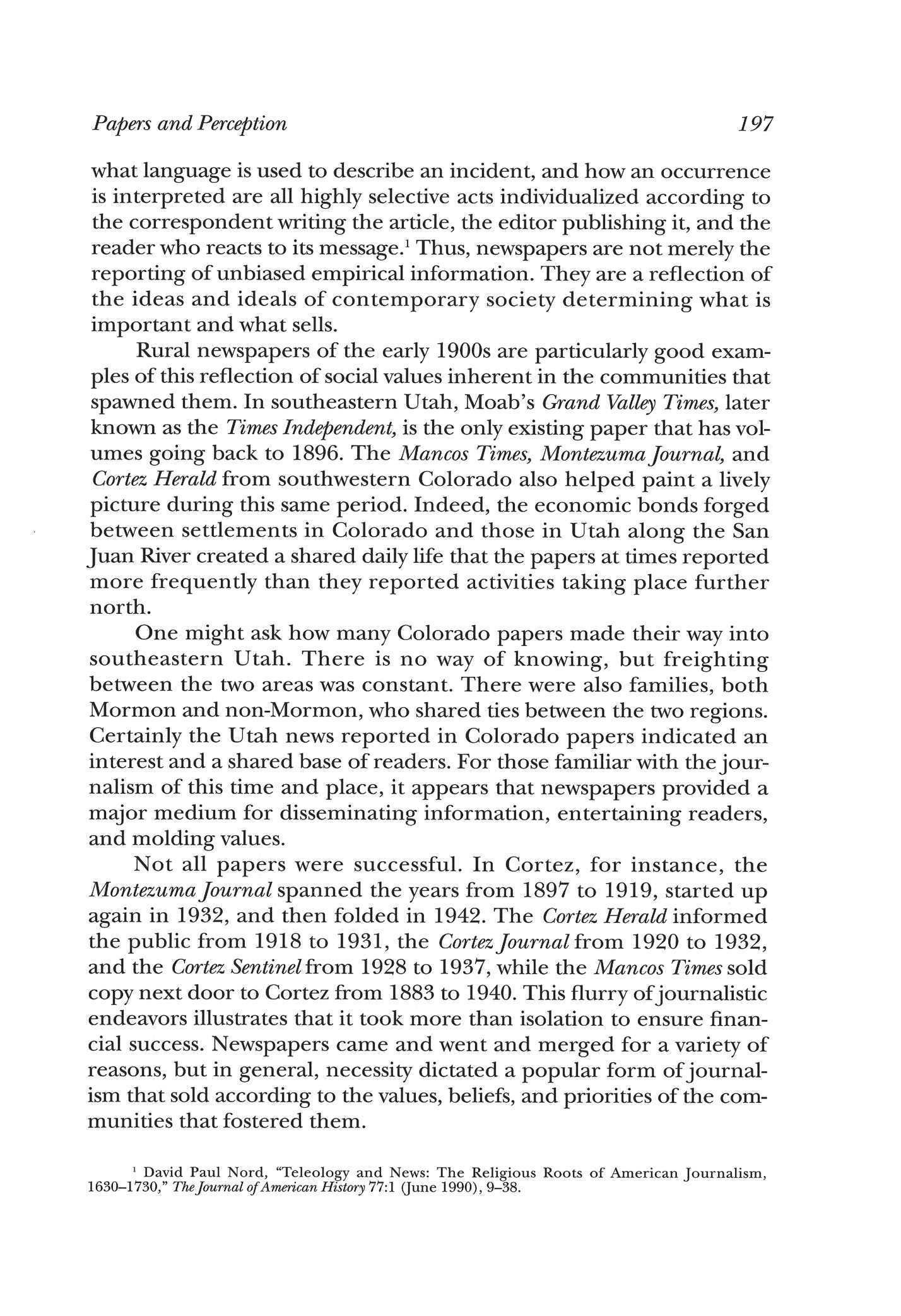

what language is used to describe an incident, and how an occurrence is interpreted are all highly selective acts individualized according to the correspondent writing the article, the editor publishing it, and the reader who reacts to its message. 1 Thus, newspapers are not merely the reporting of unbiased empirical information. They are a reflection of the ideas and ideals of contemporary society determining what is important and what sells.

Rural newspapers of the early 1900s are particularly good examples of this reflection of social values inherent in the communities that spawned them. In southeastern Utah, Moab's Grand Valley Times, later known as the Times Independent, is the only existing paper that has volumes going back to 1896. The Mancos Times, Montezuma Journal, and Cortez Herald from southwestern Colorado also helped paint a lively picture during this same period. Indeed, the economic bonds forged between settlements in Colorado and those in Utah along the San Juan River created a shared daily life that the papers at times reported more frequently than they reported activities taking place further north

One might ask how many Colorado papers made their way into southeastern Utah. There is no way of knowing, but freighting between the two areas was constant. There were also families, both Mormon and non-Mormon, who shared ties between the two regions. Certainly the Utah news reported in Colorado papers indicated an interest and a shared base of readers. For those familiar with the journalism of this time and place, it appears that newspapers provided a major medium for disseminating information, entertaining readers, and molding values.

Not all papers were successful. In Cortez, for instance, the Montezuma Journal spanned the years from 1897 to 1919, started up again in 1932, and then folded in 1942 The Cortez Herald informed the public from 1918 to 1931, the Cortez Journal from 1920 to 1932, and the Cortez Sentinel from 1928 to 1937, while the Mancos Times sold copy next door to Cortez from 1883 to 1940. This flurry of journalistic endeavors illustrates that it took more than isolation to ensure financial success. Newspapers came and went and merged for a variety of reasons, but in general, necessity dictated a popular form of journalism that sold according to the values, beliefs, and priorities of the communities that fostered them.

Papers and Perception 197

1 David Paul Nord, "Teleology and News: The Religious Roots of American Journalism, 1630-1730," TheJournal ofAmerican History 77:1 (June 1990), 9-38

The purpose of this article is to look at newspaper reporting in a very limited area, southeastern Utah, involving a clearly defined topic—the portrayal of Navajos and Utes between 1900 and 1930. This is not to suggest that a history of these people, or even an accurate evaluation of events, will emerge Rather, the questions to be answered are these: How were these two Native American groups viewed, and why were these perceptions so different? As a corollary to these concerns, what were the implied values of the reading audience?

This study is not, however, an attempt to bash newspapers of the past or to criticize the role of ruraljournalism. Nor does it attempt to look through twenty-first-century glasses to judge people of a different day by our current value systems, though some similarities do exist. This article also does not offer a full explanation of what actually happened, since the corrective results of further research in government correspondence, letters, journals, and diaries are not generally included. What it does attempt is a greater understanding of attitudes formed by the media and of the ways that reporters described events to their readers.

By 1900 the Navajos and Utes had gone through some of their greatest trials. Both had received reservation lands in 1868. The Navajos resided on a large territory that straddled the boundary between Arizona and New Mexico, with lands south of the San Juan River in Utah added in 1884. The Southern Utes, on the other hand, lived in southwestern Colorado on a land base that had continually shrunk since 1868 Efforts to expand their reservation in different directions, including land in San Juan County, Utah, met with fervent resistance.

At the turn of the century, these two tribes had generally settled into their present domains. The Utes had been forced to abandon

198

Utes in the La Sal Mountains, probably around the turn of the century; San Juan Historical Commission. Paiute Indians near Bluff, Utah; USHS collections.

their hunting and gathering lifestyle; the Navajos continued to have a pastoral and agricultural economy. On the borders of their reservations, however, both groups made use of the public domain, a practice that created serious questions about grazing, hunting, farming, and other land-use rights. The Navajos ventured across the San Juan River in search of grass and water while the Utes hunted in the Blue and La Sal mountains. There were even two composite bands, called Paiute as often as they were called Ute, that lived in Montezuma and Allen canyons, located roughly on either side of the Bluff/Blanding area.

A new century offered the possibility of a new outlook. Yet the seeds of discord and accord with the respective tribes were already sown. Instead of sympathetically understanding these cultures, their predominantly Mormon neighbors had already pigeonholed both groups. Religion, which played a central role in native and white cultures, helped determine the Mormon valuejudgments. For instance, the newspapers made only slight mention of Ute religious beliefs, perhaps because there was little pageantry involved in Ute religion. The only large Ute ceremonies were for the Sun Dance, which the government suppressed in the early twentieth century, and the Bear Dance held each spring. In the Bear Dance, men and women lined up facing each other and moved back and forth to the beat of drums and the rasp of corrugated sticks rubbed together. To most white spectators, these dances were a curiosity but offered little drama. Outsiders viewed the rest of Ute religious practices as a series of individualized rites that held no appeal, seemed simplistic in their approach, and did not correspond to their own Christian beliefs.

This was not so for the Navajo. Their complex ceremonies were graphic displays that fascinated white observers. Costumed dancers, sand paintings, intricate ritual performances, and herbal medicines caught the imagination of Anglo neighbors and fostered first a curiosity, then an empathy, and finally a tentative sense of compatibility with Mormon beliefs. The settlers sought an explanation for the perceived similarities between Navajo and Latter-day Saint tenets, and in doing so bridged hundreds of years of tribal history to "find" the Navajos' religious and historical roots in the Book of Mormon.

One of the most vigorous spokesmen for this view, Christian L. Christensen, had lived with the Navajos in northeastern Arizona and southeastern Utah for more than forty years; he later contributed a number of articles about Indians to local papers. His views repre-

Papers and Perception 199

sented those of other sympathetic settlers like KumenJones, Albert R. Lyman, and James S. Brown, all of whom tried to expose the roots of Mormonism in the highly complex and formalized beliefs of the Navajo. Christensen, sharing this obvious tendency in his articles, wrote that the Navajos were "looking for the twelve great men ... to return to them soon and restore to them all their former greatness and blessings as promised them by their forefathers. ... [though] the younger generation does not believe in the traditions of their forefathers [because] the government has interfered with their former practices. ... " The statement correlates Christensen's understanding of Navajo beliefs with the Mormon emphasis on the twelve apostles.2

In another article, Christensen described Navajo medicine men as being divided into three "quorums," each comprised of twelve men, which presided as custodians of language and customs, botanical knowledge, and astronomy. He told of some of the laws important to Navajo beliefs and even attributed to the tribe the Hebrew practice of establishing a "city of refuge" for aperson who either accidentally or intentionally killed a tribal member.3 While there are grounds for certain elements of this interpretation, it was heavily salted with Mormon and Old Testament values.

Navajo mythology, as described by Christensen, sounded very much like the Bible There were three great "personages" who created the world, placed First Man in a beautiful garden, and left First Woman with him to provide children. He fathered a "Great Son" who killed his brother and became the "father of lies, war, bloodshed and contention." First Man and First Woman discovered they were naked after being beguiled by a serpent, and that is why Indians wore breechcloths. Eventually, the forefathers of the Navajo came from "beyond the great waters in great vessels,"

and

2 Times Independent [hereafter cited as 77], May 6, 1920.

3 TI, April 29, 1920

4 TI, April 22, 1920

200 Utah Historical Quarterly

Portrait of Navajos, not dated; USHS collections.

g-rew wicked

were chastised through the visit of a supernatural being.4

The parallels between this and Mormon doctrine evident that little are so discussion is necessary.

Christensen even told of a white man, William Keams, who married two Navajo wives, lived writh the Navajos and Hopis for forty years, and knew their traditions so well that when he read the Book of Mormon "he knew the book was a true account of that people."5 With this type of press coverage, the bonds of sympathy extended more to the Navajos than to the Utes, who, as far as the settlers were concerned, had few analogous beliefs.

Perhaps a brief pause at this point is necessary to explain the interchangeable use of the terms Ute and Paiute in the newspapers and writings of this period Southeastern Utah was the home of the SanJuan Band Paiute and the Weeminuche Ute, who shared a similar language base. SanJuan County, Utah, was a point of fusion where the two groups intermingled on the periphery of the main Paiute groups to the west and the main Ute groups to the east. Local whites often called this mixed band of Ute language speakers "Piutes" and "renegades," although the culture of the Weeminuche Utes was just as prevalent.

The clearest link connecting these Utes and Paiutes to Mormonism is reflected in Albert R Lyman's article entitled "A Relic of Gadianton: Old Posey as I Knew Him," which appeared in 1923, the same year the "Ute problem" was settled In it, Lyman chose Posey, a Paiute who became a symbol of all of the pent-up frustration of these early years, and painted him in terms of events depicted in the Book of Mormon. Therein, the Gadianton Robbers, an outlaw band formed through secret oaths and bloody misdeeds, preyed upon the righteous and sometimes not-so-righteous peoples. According to Lyman, Posey and his following descended from this line of thieves and cutthroats. The settler wrote:

From the time that his fierce ancestors, of the Gadianton persuasion, swept their pale brethren from the two Americas, his people had known no law, but in idleness had contrived to live by plundering their neighbors. Posey inherited the instinct of this business from robbers of many generations.6

5 TI, May 6, 1920

6 Albert R Lyman, "A Relic of Gadianton: Old Posey as I Knew Him," Improvement Era 26 (July 1923), 791

Papers and Perception 201

Christian Lingo Christensen with oneof his converts, Senoneska, in 1894; San Juan County Historical Commission

Thus, many of the events that surrounded the Utes' struggle to maintain their lifestyle were cast by at least some whites in the light of a cosmic struggle of good over evil that had started centuries before These Utes and Paiutes were seen as spoiled children, and they obtained an image of depravity and of having an "unyielding hatred of law."7

Those Navajo and Ute tribal ceremonies open to white spectators received similarly disparate treatment. Compare, for instance, the vocabulary in two newspaper articles describing a Navajo Fire Dance (part of the Mountain Way ceremony) and Ye'ii'bicheii Dance and a Ute Sun Dance and friendship dance. The Fire Dance was billed as "big doings" with 5,000 Navajos attending the "sacred ceremonial," which "to the white man [was] a most spectacular occasion an opportunity of a lifetime. ... " The Ye'ii'bicheii Dance received similar respect. Although there was some belittling of the Navajos' "queer antics," the greed of the medicine men, and some of the men's undressed appearance, the correspondent lauded the great "power of faith and imagination in these children of nature." He concluded by remarking that although three hundred were in attendance, "a more orderly crowd of people never got together" than these "red children of the desert."8 Both articles stressed the harmony, sincerity, and friendliness of the Navajos, while the authors, somewhat patronizing at times, showed respect for the activities.

With the Utes, it was a different story. For instance, in 1911 the Southern Utes held a friendship dance with groups of Paiutes, Navajos, Apaches, and Pueblos. Announcing it in the headlines as a "Big War Dance," the author delighted in describing the sharing of food as a "big feed" of crackers piled on a piece of canvas, canned peaches served in a bucket so that people could reach in and take their share, and lemonade drunk from tin cans in which swished "such miscellaneous articles as sticks, sand, dirt, etc. , whic h onl y jjte children dancing theBear Dance on Uintah-Ouray Reservation, 1924; seemed to give an USHS collections. added relish."9

The article concerning the

7 Ibid

8 MancosTimes-Tribune

[hereafter cited as MTT], October 31, 1919; Montezuma Journal [hereafter cited as MJ], September 30, 1904

9 MJ June 15, 1911

202 Utah Historical Quarterly

Sun Dance did not portray the Utes in as negative a light; but with a front page headline announcing "Chiefs Ban Ute Sun Dance Because Whiskey Causes Trouble," the reader's mind was already focused on the stereotype of the drunken Indian.10 Rather than evoking images of order and friendliness, the Utes had their dance of friendship turned into a war dance, and their sun dance became one more opportunity to raise the specter of alcohol and the Indian

The issue of Native Americans and drinking had long been of high profile An article titled "More Drunken Utes" found its way from Vernal, Utah, into the Moab paper; it described how eight Utes had been "howling and fighting like a pack of coyotes," had broken into a home occupied by defenseless women and children, and were so drunk that some could not ride out of town.11 One needs to ask why this seemingly insignificant bit of news from another region made its way into a local paper. The answer appears to be that it appealed to the sensational stereotype already established

One of the most effective means of fostering change among Native Americans was education. By 1915 the Navajos had a boarding school at Shiprock, and the Utes had one under construction at Willow Springs. The papers described the Navajo institution in glowing terms. The Shiprock school boasted more than thirty brick buildings; barns filled with cattle, sheep, horses, and hogs under the care of older students; and machine shops, boiler rooms, laundries, sewing facilities, dairies, carpenter shops, and blacksmith shops where the young people learned trades. Greenhouses bulged with more than one thousand varieties of plants, while basketball and baseball teams competed successfully against others from surrounding towns.12

What did one read in 1915 about the Ute dormitory? Work was moving along nicely in spite of someone shooting at the superintendent on three different occasions. The note he found on his door saying "We want no school. Utes kill dead" reinforced his suspicion that perhaps the Indians were not as anxious to sit in a classroom as their neighbors were. The article's title, "Indians 'Heap Quiet' Now," suggested the Utes' reluctance to "leave the blanket."13

Even in issues concerning health, there were differences in reporting In the fall of 1918 and the winter of 1919, as the influenza

10 M/,June 28, 1934.

11 Grand Valley Times [hereafter cited as GVT], October 5, 1906

12 TI, February 16, 1922

18 Cortez Herald [hereafter cited as CH], June 17, 1915

Papers and Perception 203

epidemic raged throughout southeastern Utah, traders and travelers told sympathetically of the plight of the Navajo. The whites estimated that three thousand had already succumbed to the flu and stated that "unless the disease is checked soon, it is feared the Navajo tribe will be almost wiped out."14

The Utes, on the other hand, drew the unfavorable headline of "Superstitious Utes" in an article that told how they refused to walk to the agency for supplies, feared that the medicine used to combat the disease was coyote poison, and fled their camps at the approach of a white man because he might be a doctor. The article concluded by saying, "It seems to be a very distressing time for all the Indians, whose ignorance is reinforced by the darkest superstition."15 Navajo medical practices were no more or less "enlightened" (by Anglo standards) than those of the Utes, but this point was rarely if ever made Through this short survey of white attitudes toward the Navajo and Ute cultures, one finds supposedly dramatic differences between the two Indian groups highlighted in the papers Newspapers often took a sympathetic slant toward the Navajos because the correspondents found similarities—either imagined or real—between Anglo and Navajo culture. This group of Native Americans, though curious and exotic at times, was on the road to assimilation and was accepted because of the tribes' supposed roots in Book of Mormon history. The Utes were not as fortunate. Although they encountered some of the same circumstances as the Navajo, few whites searched for similarities, established bonds, or showed sympathy. For most Anglos, the Utes were a dark remnant from a darker past.

Cultural differences, at times, can be overlooked in favor of economic growth and development. If one group of people has something special to offer another group, bonds of cooperation can be forged in spite of disparities. Fortunately for the Navajo, this was the case. Between 1900 and 1930 the trading posts in the Four Corners region flourished through their golden years Often staffed by men and women who understood Navajo culture, these posts were located on the SanJuan River or at strategic points along road networks in the interior of the reservation From the posts came ten-foot-long sacks stuffed with wool heading for Kansas City or other points in the East to be woven into fabric. Local entrepreneurs quickly seized upon this

14 GVT, January 3, 1919; MTT, December 13, 1918

15 MTT, January 10, 1919.

204 Utah Historical Quarterly

important commodity and integrated Navajo wool into their own stock before shipping it out.

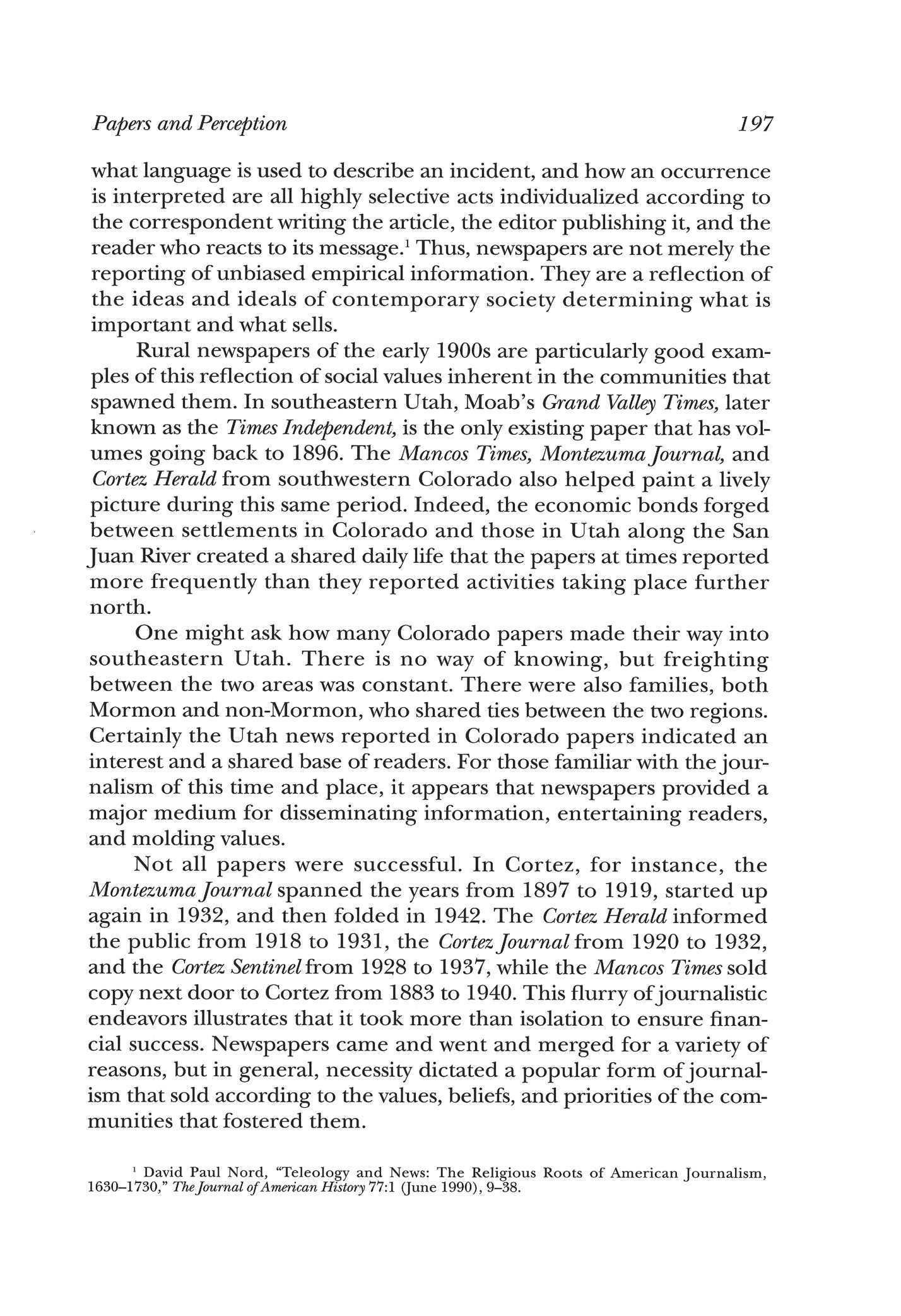

Navajos were "progressive" in their attempts to better their product. Agents introduced different types of sheep to improve the wool crop, and as one newspaper reported, these "stalwart nomads of the Painted Desert have gone far afield to improve the strain of sheep which provide wool for the famous Navajo blanket."16 Even the federal government had short clips in the paper announcing its desire "To Stimulate Trade in Navajo Blankets."17

The government also protected the blanket industry when, as early as 1914, people from southeastern Utah urged Senator George Sutherland to take action to protect the Navajos, who were being cheated out of thousands of dollars because of imitation rugs Under a new plan, both the traders who accepted a rug and the superintendent from the part of the reservation in which the rug was produced needed to verify its authenticity.18

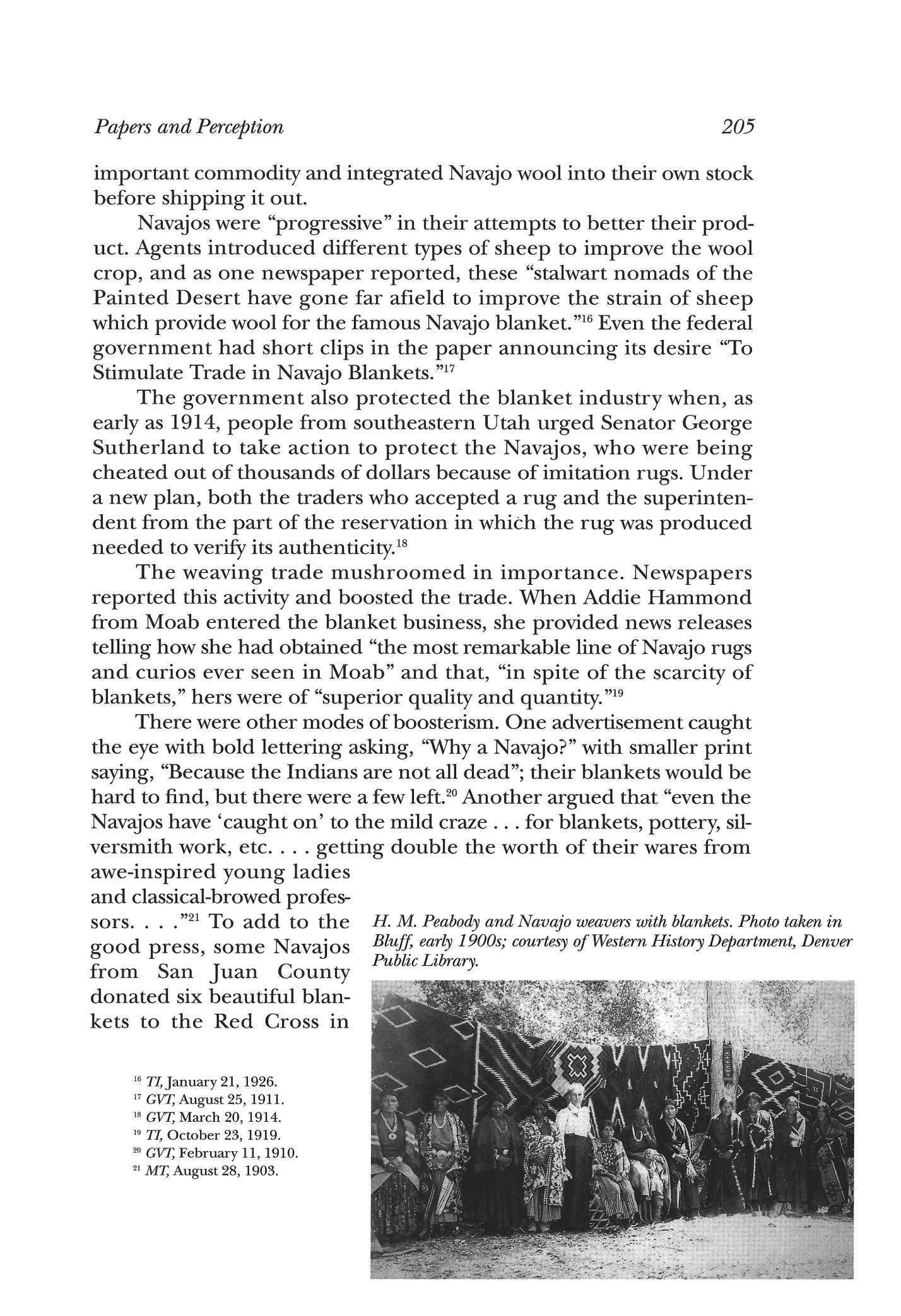

The weaving trade mushroomed in importance Newspapers reported this activity and boosted the trade When Addie Hammond from Moab entered the blanket business, she provided news releases telling how she had obtained "the most remarkable line of Navajo rugs and curios ever seen in Moab" and that, "in spite of the scarcity of blankets," hers were of "superior quality and quantity."19

There were other modes of boosterism One advertisement caught the eye with bold lettering asking, "Why a Navajo?" with smaller print saying, "Because the Indians are not all dead"; their blankets would be hard to find, but there were a few left.20 Another argued that "even the Navajos have 'caught on' to the mild craze . . .for blankets, pottery, silversmith work, etc. . . . getting double the worth of their wares from awe-inspired young ladies and classical-browed professors. "21 To add to the good press, some Navajos from San Juan County donated six beautiful blankets to the Red Cross in

16 77,January 21, 1926

17 GVT, August 25, 1911

18 GVT; March 20, 1914

19 77, October 23, 1919

20 GVT, February 11, 1910

21 MT, August 28, 1903

Papers and Perception 205

H. M. Peabody and Navajo weavers with blankets. Photo taken in Bluff, early1900s; courtesy of Western History Department, Denver Public Library.

1919 and had them presented in Monticello then in Salt Lake City. The Red Cross put the handicrafts up for bid and received fifty-three dollars for one that contained only six dollars of materials.22

The results of this burgeoning trade were salubrious As early as 1896, Colorado papers touted the effects of the SanJuan trading posts on the economy, claiming that freighting outfits "loaded out from Bauer Store [Mancos] often $1,000 worth of goods a day."23 By 1913 the Mancos Times-Tribune felt that trade "naturally gravitated to this area," with sometimes as many as six or seven heavily laden wagons groaning their way to the river This economic boon made Mancos the "recognized commercial and financial center" of Montezuma County. EvenJohn Wetherill, whose post was located in Kayenta, Arizona, preferred trading in Mancos to places in Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah. Reasonable prices, available stock, and rendered service were, according to the paper, his reasons for satisfaction, though he also probably enjoyed returning to his family's old homestead.24

The Utes had little to offer along these same lines. During the late 1800s they had been heavily involved in the hide trade, and even before 1900 newspapers reported any hunting trips off the reservation as "slaughter" and decimation of the already-diminishing deer herds.25 Hunting as a way of life was, by then, totally impractical. Beadwork, a famous craft of the Utes, was not as useful or as stylish in appearance as Navajo rugs, while Ute farming efforts were on a subsistence level and failed to compete in the twentieth-century market economy with Anglo farmers, who had better land, equipment, and techniques Utes apparently had little to offer the progressive American.

Some people may argue that at the time only a small intellectual minority would recognize the difference between a Navajo and a Ute and that economic interests were not great enough to truly differentiate between Navajos and Utes when it came to matters of life and death However, if the conflicts and the reporting of them that occurred between 1900 and 1930 are any indication, the white population played favorites and decided who would be cast in the roles of "good guys" and "bad guys."

This was an era of yellowjournalism, steeped in the tradition of

22 TI, September 25, 1919

23 Ira Freeman, A History of Montezuma County, Colorado (Boulder: Johnson Publishing Company, 1958), 209

24 MTT; April 25, 1913; July 9, 1915

25 GVT, September 7, 1906; see also Robert S McPherson, The Northern Navajo Frontier (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1988), 51-62

206 Utah Historical Quarterly

the Spanish-American War, the hysteria of World War I, the witch hunts of A. Mitchell Palmer, the prejudicial trial of Sacco and Vanzetti, the rise of the Ku Klux Klan, and the roar of the 1920s Though many of these national events were tangential at best to the Four Corners region, the reporting style that appealed to human curiosity for the dramatic and sensational found its way into newspapers and stirred the emotions of readers. There is no mistaking the attitudes of the writers, readers, and players in the events concerning Navajos and Utes as they unfolded in the newspapers.

In fairness to the white settlers of SanJuan County, they had suffered at the hands of the Utes more than they had from the Navajos because the Utes had a stronger claim to lands lost through white settlement. Consequently, similar incidents within the different tribes were reported and handled differently. If each incident had been viewed uncolored by the local feelings of frustration, the Navajos and Utes might have drawn equivalent comments. But itjust did not happen that way

Take, for instance, murder. On November 18, 1909, tragedy struck on the Navajo reservation. At ten o'clock in the morning, trader Charles Fritz opened the door of the Four Corners Trading Post to a husky Navajo man named Zhon-ne of the To dich'iinii (Bitter Water) clan Zhon-ne had been looking for horses and decided to stop by, get something to eat, and transact some business at the store. Fritz fed the Navajo, who helped carry some wood from the pile outside then warmed himself by the fire while the storekeeper sharpened his saw. At this point, Zhon-ne decided to rob the trader, so after riding up on the hills to the east to see if anyone was coming down the road, the Navajo returned, waited for Fritz to venture to the wood pile, then killed him as he re-entered the post The Indian fired three times with a .22 caliber rifle, hitting the victim at the base of the skull, behind the left ear, and in the ear to ensure he was dead. Zhon-ne then stepped over the corpse; vaulted the counter; emptied the cash drawer of its $26.35 in coin, $18.35 in silver buttons, and a silver bracelet valued at $12.00; took a trail across the San Juan River heading toward the Carrizo Mountains; and arrived at his home, ten miles west of Teec Nos Pos, Arizona, after dark.26

By ten o'clock that night, an Indian had found the corpse and

Papers and Perception 207

26 Detailed information concerning Zhon-ne's activities comes from an investigative report sent by Charles W Higham to Hon U.S District Attorney, Salt Lake City, December 9, 1909, J Lee Correll Collection, Navajo Library, Window Rock, Arizona

had ridden to Shiprock to alert William T. Shelton, who, with an interpreter and two Navajo police, arrived at the scene of the crime just after daylight. By eight o'clock on the nineteenth, Zhon-ne was sitting before Shelton at the post, admitting his guilt.27

The agent incarcerated Zhon-ne in the Shiprock jail, but he preferred that the trial be held in Salt Lake City. He was also anxious to get Zhon-ne out of Shiprock since the prisoner had obtained a sharpened spike, threatened a guard during an attempted escape, and now had to be permanently handcuffed and watched byjailers. The prisoner recognized the consequences of his deed and realized that, as the newspapers claimed, he would be "hanged by the neck until dead, dead, dead."28

More than a year dragged by Zhon-ne took up new residence in Salt Lake City, had a severe bout with tuberculosis, and eventually pled guilty to the reduced charge of manslaughter Shelton feared that a diminished sentence, coupled with the fact that a similar incident— the recent killing of Richard Wetherill in Chaco Canyon—would cause whites to become increasingly prejudiced against other Indians accused of crimes. The court eventually sentenced Zhon-ne to eight and one-half years at the federal penitentiary at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. The punishment lacked the severity that Shelton desired as a warning to future troublemakers, but it was handed down because the prisoner suffered from an incurable tubercular infection that physicians believed would kill him within two years. 29

Although Zhon-ne sat passively through the trial and took little interest in the proceedings, once he arrived at Leavenworth his attitude changed On the way to prison, Zhon-ne took out a feather and stroked it carefully. Marshal Lucian H. Smith, who was accompanying him, placed the feather in the Indian's hat, but when the prisoner arrived at the jail, one of the guards took it away. Zhon-ne "let out a yell that could be heard for a half a mile" and was not happy until Smith convinced the guard to return it.30 Surprisingly, Smith would continue to be a friend to Zhon-ne. The prisoner responded well to the medical treatment he received at

27 Harvey Oliver, interview by Robert S McPherson on May 7, 1991, in possession of author Charles W Higham to District Attorney (Monticello), December 9, 1909; Shelton to Hiram E Booth, January 17, 1910; Shelton to William Ray, May 14, 1910; Shelton to Ray, July 21, 1910, J Lee Correll Collection, Navajo Library, Window Rock, Arizona

28 GVT, February 25, 1910

29 Shelton to Hiram Booth, April 8, 1911,J Lee Correll Collection; GVT, April 21, 1911 For a different account of the legal proceedings, see Frank McNitt, The Indian Traders (Norman: University of Oklahoma, 1962), 324

30 GVT, May 5, 1911.

208 Utah Historical Quarterly

Leavenworth, completed three years of his sentence, then applied for parole. He asked Smith to speak on his behalf so that he could return to his aged parents on the reservation. No further information concerning Zhon-ne's release has been found, but his parole appears highly probable.31

Considering that awhite man had been killed, the reporting of this incident was handled in a mild manner. Headlines such as "Zhon-ne Not Terrified," "Navajo Given Light Sentence," "Feather Gladdens Heart of Dying Indian," and "Zhon-ne Asks Parole" tell the story as it was reported in the newspapers over a four-year period. Though the murder was actively condemned, reporters painted the criminal as an "ordinary looking Indian of twenty-five or thereabouts. . . . [who] was fat and sleek and looked contented."32 His ailments, attachment to the feather, request for parole, and dependence on Deputy Smith for release gave Zhon-ne a very human air, one that people could relate to.

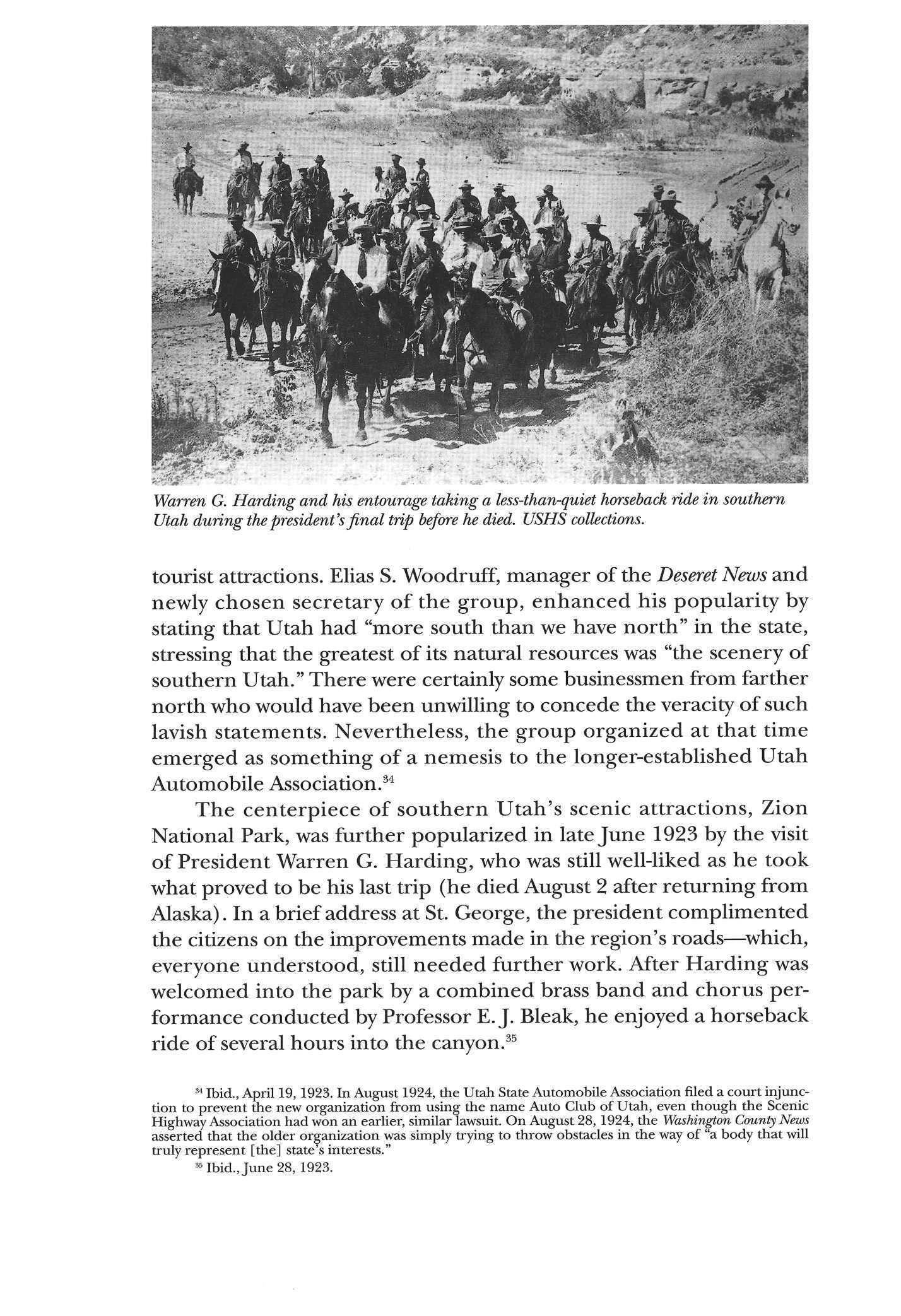

Around the same time that Zhon-ne sought parole, another incident occurred, this time involving Utes. Although there had been numerous small conflicts before, this particular event made front page news for over six months. The problem started in March 1914 when a Mexican sheepherder named Juan Chacon camped with some Utes and Paiutes from the Montezuma Canyon area. Among them was Tsene-gat, also known as Everett Hatch. Chacon spent the evening playing cards and visiting around the campfire. A few days later he was found dead, and witnesses claimed Tse-ne-gat had killed him.33 Ten months later Tse-ne-gat, fearing that his life was in danger, had still not surrendered, so U.S.Marshal Aquila Nebeker, along with local helpers from Cortez, Bluff, Blanding, and Monticello, decided to find and arrest him. The newspapers set the stage for the approaching drama by saying that "Hatch has a notorious reputation as a bad man," "had defied several attempts to bring him into custody," was "strongly entrenched with fifty braves who will stand by him to the last man," and with his group had been "terrorizing" the people of Bluff.34 The headlines a week later could almost be predicted. In Moab, the Grand Valley Times splashed across the page, "1White and 3 Piutes are Killed," with a subheading of "Indians defy U.S. Authority— Entrenched in Cliffs South of Bluff, Renegades under 'Old Poke' Say

31 GVT, February 13,1914

32 GVT, February 25, 1910

33 For a detailed explanation of this event and others surrounding it, see Forbes Parkhill, The Last of theIndian Wars (N.P.: Crowell-Collier Publishing Company, 1961)

34 GV7; February 19, 1915

Papers and Perception 209

They Will Never Give Up." The Mancos Times followed suit with "Indians Resist Arrest; Joe Aiken Killed." Both papers tried to paint the picture of treacherous Indians, heavily fortified, waiting in ambush for the whites to approach. The "uprising" occurred when the seventyfive-man posse approached the Ute camp in the light of dawn A startled early-riser gave "whoops of warning" to awaken the others then opened fire. Initial volleys killed two Indians and one white (the other "killed" Ute was only wounded) as the posse implemented "Indian strategy of the kind that one is accustomed to read in the histories of early life in the West."35 Another group of Indians, hearing the commotion, came up from the SanJuan River, approached the cordon from the rear, and started firing. The whites and Indians called a truce, the engagement ended, and the Utes fled for the wide open spaces.

Reporters continued to use the language of war In an article named "All Quiet at Bluff," phrases such as "watchful waiting," "additional guns and ammunition," "Navajo spies," "renegade Indian band," "retreated to a strong position in the hills," "Nebeker is still determined," and "no other intelligence" maintained the heat under the cauldron of contention.36

At the same time, "Brigadier General [Hugh] Scott, Chief of Staff of the United States Army," was on his way to "attempt a peaceful settlement with the recalcitrant Piute Indians." The decision to send Scott was made only "after conferences between officials of the war department, department ofjustice, and the interior department." 3 7 What greater military dignity could be bestowed upon this small fray than to have Washington leaders conferring over its outcome?

To contrast the opposing sides, the Grand Valley Times spoke of the "Blanding volunteers" and the "Monticello boys" "stringing" back to their respective communities, while another article told of how "Old Posey" killed his brother Scotty, who wished to end the conflict. Posey was "sullen and refused to bow to law," while Scotty was "pleasant . . . and among the last tojoin with the outlaws."38

When Scott arrived in Bluff, he made it clear that he would try to settle the issue peacefully. A week later, when no concrete results had yet been obtained, headlines told of the Indians turning down a "Pow-

35 GVT, February 26,1915

36 GVT, March 5, 1915

37 Ibid

38 Ibid.

210 Utah Historical Quarterly

wow with Scott" with a subheading that "Cavalry May be Called in."39 A week later, however, Scott had "captured renegade Indians" by meeting with them, promising all twenty-three of them protection, and honoring the request that the four captives—Poke, Posey, Tse-ne-gat, and Posey's Boy—be brought to Salt Lake City for questioning. As the papers put it, "the redskins . . . had come to smoke a pipe of peace . . . with a representative of the Great White Father," and "he had succeeded."40

ByApril officials in Salt Lake released all of the prisoners except Tse-ne-gat, who went to Denver to stand trial. Before the Ute ever entered the courtroom, the Mancos Times-Tribune announced that the charges against him could not be proven; but when he was acquitted, the ire of the settlers in the Four Corners area reached meteoric heights.

Yellowjournalism continued to testify against the Indians. Articles and clips informed the public of the activities of Tse-ne-gat, Poke, and Posey, reinforcing negative images. Brushfire conflicts in 1919, 1921, and 1923 became important news and fanned the coals of disagreement. Even in the "off" years, when nothing newsworthy occurred, papers reminded people of the aggravation felt between the two races. A quick perusal of information concerning Utes for the last four months of 1917 shows the intensity of feelings.

In August the San Juan Blade, a short-lived newspaper published in Blanding, reported that "Ute Threatens Man With Gun . . . When Told to Move on; Utes Becoming Ugly." A later article derided John Soldiercoat, who lost his "superstitious fear" of the "mysterious paper talk," and Posey, who talked on a phone for the first time with "guttural grunts, inarticulate groans, and 'toowitchchamooroouppi' . . . [so] that [the] line was put out of commission for three weeks." Other headlines insisted that the "Utes Growing Ugly . . . [when they] Helped themselves to Farmers Feed and Defied Interference by the Settlers"; that a "Noted Indian Prepares for War [as] Old Posey Stored up Guns and Ammunition ... to Oppose Uncle Sam"; that "Indians Again Growing Bold" when three Utes jumped on a lone woman's car four miles south of town and frightened her with their aggressive actions; that "Ute Indians Hold up Blanding Boy" and took his watch; that "Ute Trespassers Made to Pay" when confronted with charges for grazing their horses in a settler's field; and that "Old Posey

39 GVT; March 19, 1915

40 GVT, March 26, 1915

Papers and Perception 211

May Stir up Trouble" because he "had assumed a surly and threatening manner and appeared to be gathering about him a number of renegade redskins."41

There were other articles and clips, some more inflammatory than others. Even those few that attempted to be partly complimentary, such as one that told of Utes hired to clear sagebrush, used such language as "Noble Redman Works Best on Empty Stomach."42 This tendency became so pronounced that an unsigned note in the San Juan Blade published on November 30, 1917, criticized the paper for "openly convicting itself ofjealousy and ignorance . . . [and] that the people of San Juan wanted the news instead of knocks."43

Yet the really pro-Ute journalism came from outside of the region and was sponsored by the Indian Rights Association (IRA) headquartered in Philadelphia. In November 1915, shortly after the Tse-ne-gat incident, M K Sniffen, secretary of the IRA, wrote an article based on his visit with the Poke and Posey bands, and his evaluation of the fracas flew in the face of the local oral and newspaper accounts. He pointed out that two-thirds of the posse that attacked the peacefully camped Indians were comprised of '"roughnecks' and 'tinhorns' to whom shooting an Indian would be real sport!" The Utes, who were not living on the reservation because of its undesirable conditions, had only protected themselves and their families, he wrote. Cattlemen seized upon the fight as an opportunity to move the Indians off the range lands; this action expressly contradicted the government's desire to allot the Indians individual tracts of land from the public domain to start the "civilizing" process by discouraging the Indians from living as a tribe. Sniffen concluded his remarks by writing, "The progressive Utes are now patiently waiting to see if the United States Government intends to give them 'a white man's chance.' Surely they have proved their right to it."44

Local papers reacted immediately. Far from helping the Utes' situation, Sniffen unwittingly polarized even more whites against the Indians and their advocates. For about a month in the early days of 1916, front-line attacks marched across the pages of the Cortez Herald. No kick was too low for this "Indian lover," who was "probably being paid a big salary for traveling over the country to fix up fairy tales

41 San Juan Blade [hereafter cited as SJB], August 24, 1917; October 5, 1917; October 24, 1917; November 2, 1917; December 21, 1917

42 SJB, October 12, 1917

43 SJB, November 30, 1917

44 M K Sniffen, "The Meaning of the Ute War'" (Philadelphia: Indian Rights Association, November 15, 1915), 1-7, Special Collections, Marriott Library, University of Utah, Salt Lake City

212 Utah Historical Quarterly

about the persecuted red men."45 The papers argued that the members of the posse were really heroes who had risked their lives under "Uncle Sam's command." Writers insisted that if Sniffen wanted a crusade, he should investigate where the Utes got their high-powered rifles and ammunition, or who shot at the builders of the school on the reservation, or why the government had not yet built the promised irrigation ditches for the Indians.46

Antagonists accused Sniffen of shoddy investigative techniques, jumping to conclusions, and not understanding the real situation of the local people. But as they refuted all of his charges in one way or another, the papers laid bare many of the real problems facing the Utes and how few of these concerns had yet been addressed. By defending its frontal position, the white majority exposed its flanks to further charges

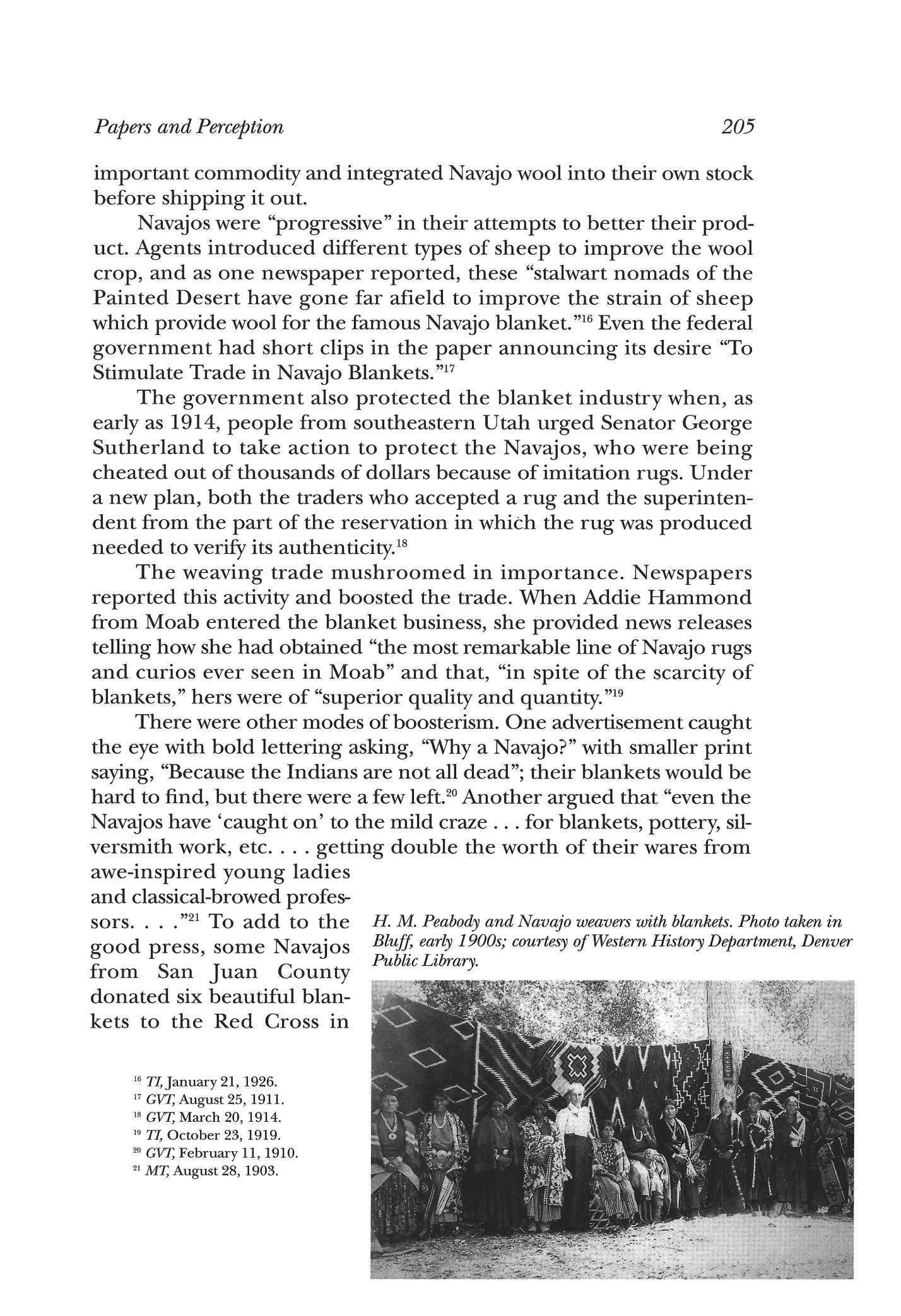

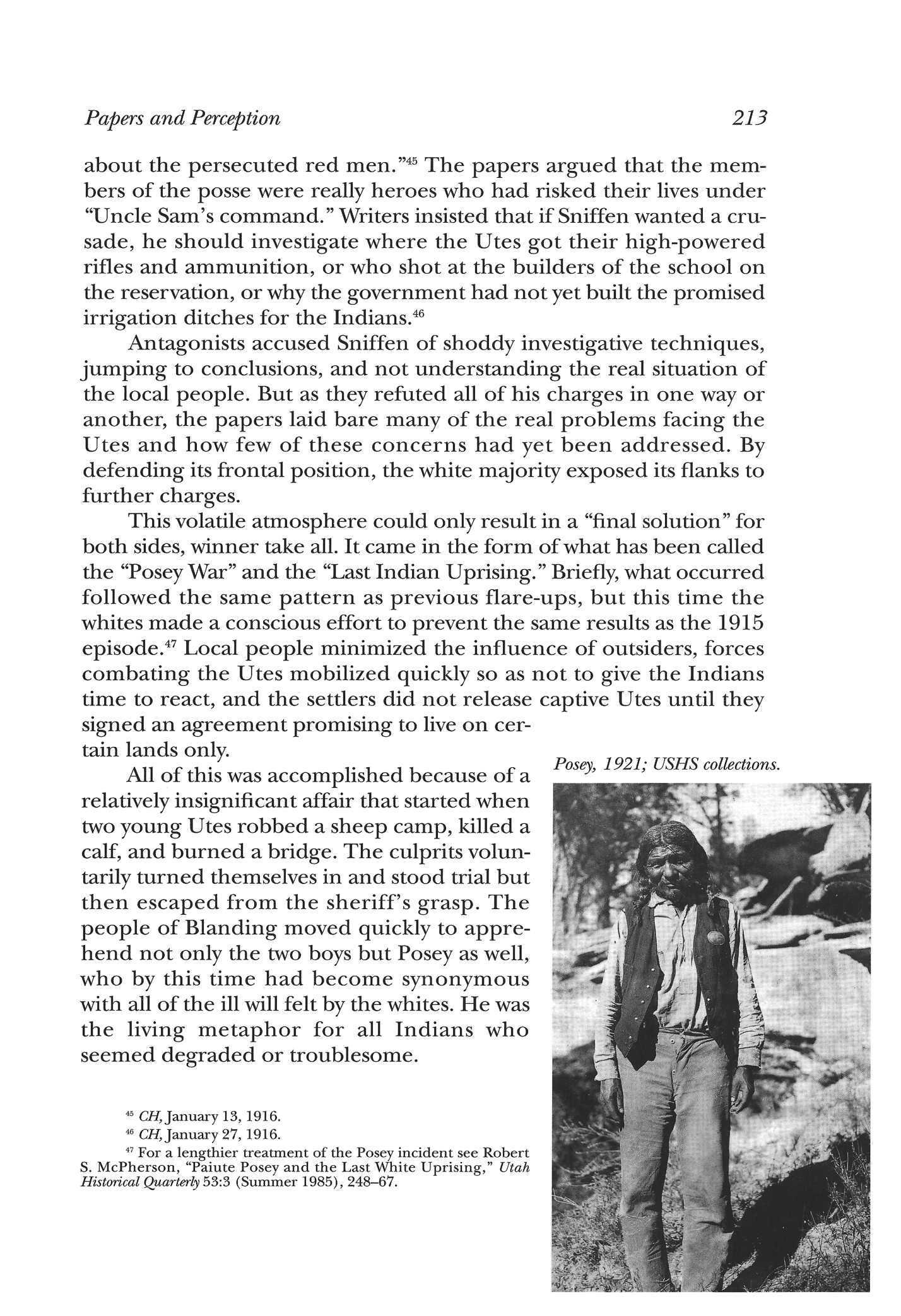

This volatile atmosphere could only result in a "final solution" for both sides, winner take all. It came in the form of what has been called the "Posey War" and the "Last Indian Uprising." Briefly, what occurred followed the same pattern as previous flare-ups, but this time the whites made a conscious effort to prevent the same results as the 1915 episode.47 Local people minimized the influence of outsiders, forces combating the Utes mobilized quickly so as not to give the Indians time to react, and the settlers did not release captive Utes until they signed an agreement promising to live on certain lands only.

All of this was accomplished because of a relatively insignificant affair that started when two young Utes robbed a sheep camp, killed a calf, and burned a bridge The culprits voluntarily turned themselves in and stood trial but then escaped from the sheriff's grasp. The people of Blanding moved quickly to apprehend not only the two boys but Posey as well, who by this time had become synonymous with all of the ill will felt by the whites He was the living metaphor for all Indians who seemed degraded or troublesome.

45 C77Januaryl3, 1916

46 C/7,January 27, 1916

47

Quarterly 53:3 (Summer 1985), 248-67

Papers and Perception 213

For a lengthier treatment of the Posey incident see Robert S McPherson, "Paiute Posey and the Last White Uprising," Utah Historical

Posey, 1921; USHS collections.

The newspapers had played a significant role in developing this attitude, making Posey the lightning rod waiting to be struck His name had appeared in either direct or indirect accusation with almost every negative incident that occurred in the past. People often cited his band of Utes as the culprits in a misdeed: Posey was said to have been the man who pulled the trigger on Joe Aiken, the white fatality in the 1915 fight; Posey reportedly killed his brother, Scotty, because the latter wanted a peaceful settlement of that conflict; and he killed his wife—by accident, he said, though many settlers refused to believe it was a mishap. While there were varying degrees of truth to many of these claims, tension over the years had increased. Posey also avoided living on the reservation and was such a colorful character that his threats, cajoling, and antics for food at a cabin door or out on the range often brought a strong negative reaction to what would normally have been forgiven.48 Thus, the 1923 "war" served as the catalyst by which evil could be exorcised.

The actual events of the war have been examined elsewhere, but the contemporary press described it in the finest tradition of hysterical World War I yellow journalism. The prose becomes too voluminous to recount in detail here, but glimpses of it show its general tenor On March 22 the Times-Independent noted that "Piute Band Declares War on Whites in Blanding" and that the county commissioners had sent a note to Governor Charles Mabey requesting a scout plane armed with machine guns and bombs. Supposedly, members of the posse had five horses shot out from beneath their riders (in reality, it was only one); the men feared that four of their number had been ambushed; and "the most disquieting feature is the fact that Old Posey, the most dangerous of all the Piutes, is in charge of the band."49

In reality, there was little going on in the "band" other than a massive exodus of Utes and Paiutes fleeing their homes to escape into the rough canyon country of Navajo Mountain; they understood all too well that their presence near white towns automatically involved them in the conflict, consequently making them a target. Posey fought a rear-guard action to prevent capture, was eventually wounded, and watched his people get carted off to a barbed wire compound set up in the middle of Blanding. A month later he died a morbid death from his gunshot wound.

214 Utah Historical Quarterly

48 GVT, March 5, 1915;June 4, 1915;June 11, 1915; see McPherson, The Northern Navajo Frontier. 49 77, March 22, 1923

During the "war" the newspapers reported that the state of Utah had put a $100 reward—dead or alive—on Posey, now charged with insurrection, a crime punishable by death. C. F. Sloane of the Salt Lake Tribune stayed in Blanding and fired off press releases with a thin veneer of truth covering a mass of outright lies. He had Blanding surrounded during "thirty-six hours of terrorism"; Indians in war paint riding the streets; Posey, "the red fox," forming a "mobile squadron"; a well-planned Paiute conspiracy that included a hold-up of the San Juan State Bank; and finally, "sixty men skilled in the art of mountain warfare awaiting the call to service."50

Reminiscent of the lively reporting of World War I, the accounts gave the town a military character: "Blanding since the outbreak has become more or less an armed camp. It wears the aspect of a military headquarters. The arrival and departure of couriers from the front is a matter of public interest."51

The citizens of Blanding were not fooled. Many of them kidded the reporters about their coverage of the incident, but this had little effect on what went out by telephonic relay. When one person asked a correspondent why he was not writing the truth, he gave a very simple answer: "We're not ready to go home yet, and if we don't keep something going, we'll be getting a telegram to come home." 5 2

Reporters made Posey's death just as dramatic as they made his life. One newsman said he had been killed in a cloudburst as the resulting flood swept him down a canyon. Another believed he had died of natural causes but said that, as far as the Utes were concerned, poisoned Mormon flour had done the job.53 The generally accepted explanation was that he had died from blood poisoning incurred by the gunshot wound. Regardless of the cause, the newsmen could report with finality that he had gone to the "happy hunting grounds"; they also mentioned that many of the Utes were content that Posey had "gone beyond," while the whites vied for the position of having the best stories to come out of the war.

When Posey's death was certain, some of the Utes took Marshal J. Ray Ward to where the body was located so that he could certify the death The law officer buried the corpse and disguised the grave—to

50 Salt Lake Tribune, March 21 to April 5, 1923

51 Ibid., March 24, 1923

63 TI, April 5, 26, 1923.

Papers and Perception 215

52 John D Rogers, "Piute Posey and the Last Indian Uprising," MS CRC-J6, April 29, 1972, Charles Redd Center for Western Studies, Harold B Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah, 22

no avail. It was exhumed at least twice by men who wanted to have their picture taken with the grisly trophy. A forest ranger, Marion Hunt, claimed in the newspaper that he had found the body during a routine range examination a few days before Marshal Ward ever appeared on the scene. 54 It seems that everyone wanted to claim some part in the destruction of evil incarnate

With all of this negative press for the Utes, one might assume that the Navajos were peacefully living the life of "model" Indians. The majority did live a quiet existence of farming and sheepherding, but as in any society there were those troublemakers who seemed to revel in stirring up conflict. One of the most notable was a Navajo leader named Ba'ililii, who opposed Agent William T. Shelton and his plans for improvements in the Aneth area. Ba'ililii is still a controversial character.55 Some Navajos viewed him as a hero who withstood the inroads of white civilization in the form of Shelton's government policy. Others felt that Ba'ililii used witchcraft, thinly veiled threats, and outright force to coax and coerce a faction of Navajos and discourage them from sending their children to school, from using the government sheep-dipping vats located at the mouths of Montezuma and McElmo creeks, and from following the orders of Navajo policemen

As a medicine man and a notable figure in the community, he used his persuasion and personal influence to do everything he could to frustrate the adoption of practices he felt were counter to traditional Navajo culture.

On October 27, 1907, Shelton and his Indian police led Captain H. O. Williard and two troops of the Fifth Cavalry on a surprise attack of the Navajos' camp The soldiers killed two Indians, wounded another, and captured Ba'ililii along with eight associates

54 T7, April 26, 1923; GVT, May 17, 1923

55 See J Lee Correll, Bai-alil-le: Medicine Man or Witch?

Navajo Historical Publications,

Biographical Series no 3 (Navajo Parks and Recreation: Navajo Tribe, 1970)

Right: Ba 'ililii. Below: Ba 'ililii with followers and their captors. Ba 'ililii is seated, thirdfrom right; Agent Shelton is standing, sixthfrom left. From Clyde Benally with Andrew O. Wiget, John R. Alley, and Garry Blake: Dineji Nakee' Naahane': A Utah Navajo History (Monticello: San Juan SchoolDistrict, 1982).

216 Utah Historical Quarterly

deemed equally troublesome. The soldiers marched the malcontents to Shiprock, Fort Wingate, then Fort Huachuca, where they spent two years at hard labor.56

During this incident, there was very little newspaper coverage, even though the fighting occurred only thirty miles from Bluff. Reporters calmly told the story about the "Indian Battle in Southern Utah" in which "three [actually, two] persons were killed." The cause, according to the papers, was the Navajos' "disinclination to observe regulations So offensive became their actions" that Superintendent Shelton had sent for soldiers to serve as a "quieting effect."57

There were, of course, some major differences between the Posey and Ba'ililii affairs. In the latter, the agent took a strong hand, used the professional military, contained the problem on reservation lands, and ended the incident quickly. With the Utes, who interacted directly with the settlers, the conflict had simmered for years, and the actual fracas dragged on for over a month Yet an objective examination shows that each of these conflicts involved the same number of Native Americans killed and the same number of active participants. Each centered around strong-willed leaders who did not want to submit to encroaching white authority, and neither pulled into the fray the larger body of tribal members. And, to use a euphemism from today's military, both conflicts involved pre-emptive, surgical strikes

A big difference, however, was the press coverage, whose vitriolic reporting of Ute activities reflected public sentiment and attitude

When looking at the Ute and Navajo agency records, one gets the impression that between 1900 and 1930 there wasjust as much murder and mayhem in one group as the other; but to read the newspapers one would think there was only one set of problems confined to a single group

Perhaps this skewed perception was due to changes that were taking place Between 1900 and the early 1930s, dramatic events swept through the Four Corners region. Events that ranged from gold rushes and oil booms to increased tourism made southeastern Utah blossom as few had expected. At the time, the Utes were using much of the land in the public domain upon which white men's eyes were focusing These lands had traditionally belonged to the Utes, and

56 "Testimony Regarding Trouble on Navajo Reservation," U S Senate Document 757, 60th Congress, Second Session, March 3, 1909, 53-54; Shelton to Commissioner of Indian Affairs, January 10, 1907, cited in David M Brugge, "Navajo Occupation and Use of Lands North of the San Juan River," unpublished manuscript in possession of author

57 GVT; November 8, 1907

Papers and Perception 217

when whites encroached on them the Utes naturally reacted; the persistent low-grade irritation between the two cultures easily flared into conflict. As early as 1921, two years before the Posey incident, the papers noted that almost 200 applicants who had filed oil claims on "Piute Reservation" lands in San Juan County were being rejected because of Indian ownership.58 Following Posey's death, the government took the opportunity to solve the Ute issue by allotting parcels of land in Allen and Montezuma canyons to individual tribal members, then throwing the rest open for livestock grazing, oil and mineral exploration, and homesteading. Although the situation was complex, the end result effectively removed the Utes' claim to mineral development, forced them to stop roving, and encouraged them to start walking the road toward acculturation.

The Navajos fell heir to a far different situation. In exactly the same area, they added two tracts of land to their reservation—one in 1905 and another in 1933. Ironically, the exchange in 1933, known as the Aneth Extension, encompassed the lower third of Montezuma Canyon, which had historically been Ute territory.59 The Navajos also received the right to lease their oil claims for mineral development in return for royalties. Eventually, oil companies ranged through the Aneth area and the lands south of the San Juan River known as the Paiute Strip and paid substantial sums of money to the tribe for this privilege. The Navajos ended up holding a bag of riches; the Utes ended up losing some of the land that now provided those riches. To lay all of these events at the feet of yellowjournalism is to grossly oversimplify a series of complex issues that beg for a multiplicity of answers. However, to underestimate the power of public opinion in its many forms—newspapers, letters, petitions, lobbying, voting, and armed force—misses the point that actions spring from thoughts and emotions.

By the mid-1930s, as reasons for confrontation subsided, attitudes shifted. On a national scale, it came in vogue to be an advocate rather than adversary of the Indian. Policy switched from agent control to self-determination during the John Collier administration of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, some anthropologists became apologists, and historians wrote revisionist tracts that attempted to explain events through Indian eyes.

58 GVT, November 10, 1921

59 For a more detailed examination of the control of this area of the reservation, see Robert S McPherson, "Canyons, Cows, and Conflict: A Native American History of Montezuma Canyon, 1874-1933," Utah Historical Quarterly 60:3 (Summer 1992), 238-58

218 Utah Historical Quarterly

Even the newspapers took up positive themes. For example, the Times Independent carried a weekly column about various Indian tribes throughout the United States. The lives of famous chiefs became popular, as did reports of the comings and goings of archaeologists and anthropologists when they visited the Four Corners region to study Anasazi remains or Navajo culture. One article, entitled "Indian Not Given His Deserved Due," told of Native American contributions to U.S. culture. Another, called "The Indians' Memorial Day," featured the Southern Utes, among other tribes, in explaining how Native Americans paid homage to their dead.60

As the era of yellowjournalism against Indians came to a close, friction took on a new form, this time against the Navajos and their livestock in the form of livestock reduction. The Navajos watched, bewildered at the destruction of their herds of sheep, goats, horses, and cattle in the name of soil conservation and environmental sanity. Livestock reduction moved the Navajos from relative economic independence to dependence, but the newspapers felt little need to report the trauma as they centered on the larger story of the Great Depression. Aside from articles recognizing the past, the Indian was presently forgotten.

The heat and excitement of the newspaper articles written between 1900 and 1930 has cooled, as have the issues they reported. The papers are now filed away on dusty shelves or recorded on plastic microfilm, left for students of history to ponder. But they also remain as a memorial to the passions that shaped an era of important decisions, when Indians met whites in yellow journalism.

60 MTT, November 18, 1932; TI, May 28, 1931.

Papers and Perception 219

"Redeeming" the Indian: The Enslavement of Indian Children in New Mexico and Utah

BYSONDRA JONES

"Naked Children Playing, "photo byJack Hitlers, used by permission of National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution.

Sondra Jones is an independent researcher living in Provo Her book on Indian slavery and Mexican traders will be published this year by University of Utah Press.

BYSONDRA JONES

"Naked Children Playing, "photo byJack Hitlers, used by permission of National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution.

Sondra Jones is an independent researcher living in Provo Her book on Indian slavery and Mexican traders will be published this year by University of Utah Press.

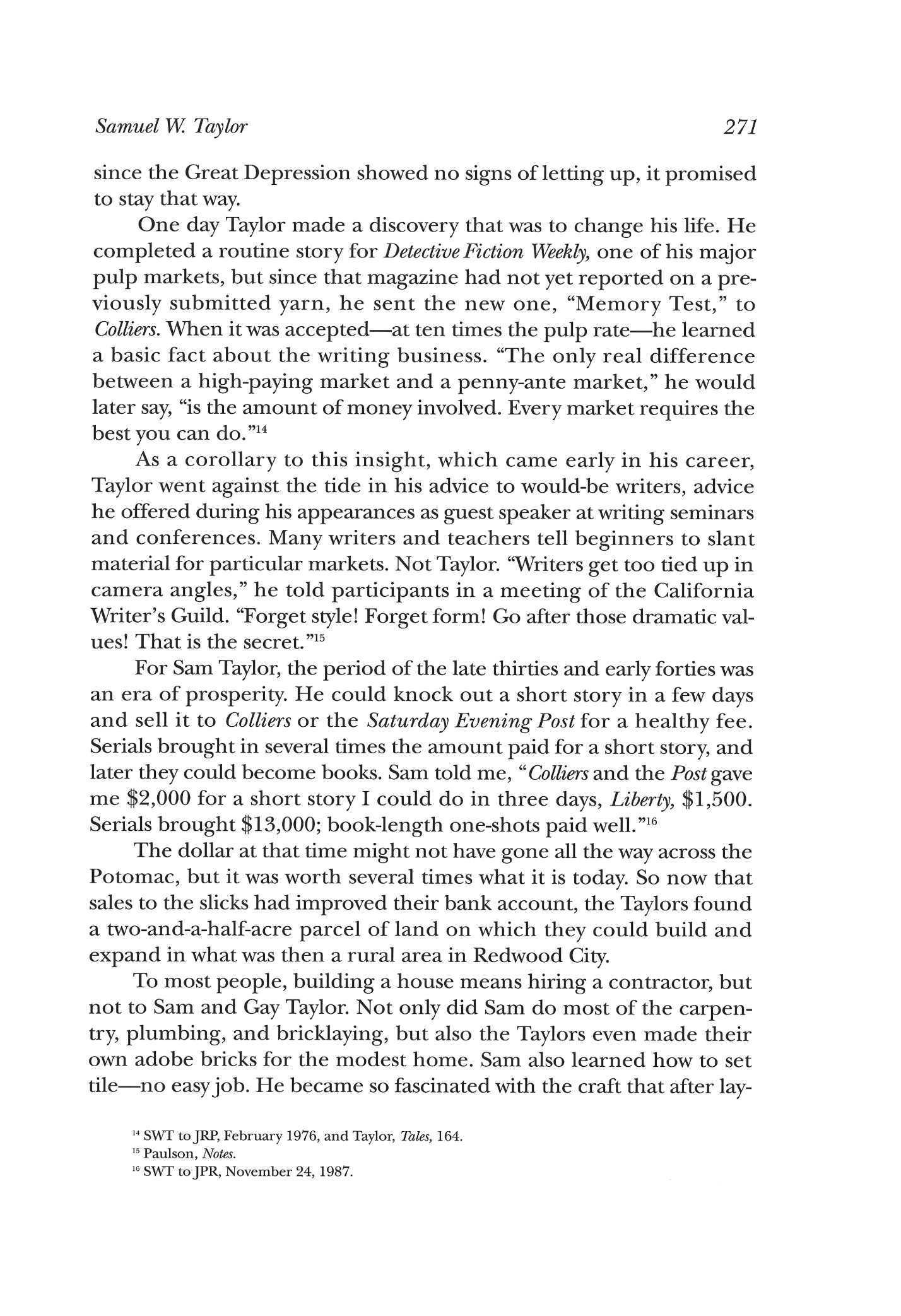

FRO M THE DAY CHRISTOPHER COLUMBUS carried Indian slaves back to Spain after his first voyage of discovery, Europeans saw the enslavement of American Indians both as a profitable enterprise and—for the Spanish, particularly—as a means of bringing vast numbers of souls to Christ In the New World itself, traffic in captives was already an ingrained tradition among the Indians; not only did the earliest Europeans witness the use and abuse of war captives by the various tribes, they also saw that systematic raiding and warfare were integral parts of the "harvesting" of such menials.1 Europeans were quick to follow suit After all, a similar tradition already existed in Europe, where both Christians and Muslims virtually enslaved prisoners of war during the Mediterranean wars. Aristotle himself had declared that "persons whose customs were barbarous were natural slaves."2 Slavery—considered a humanitarian alternative to the outright slaughter of a conquered people—was an enterprise that was both punitive and profitable It was also an excellent tool for converting the heathen—or so the Pope had decreed. As this doctrine was pragmatically extended to the New World by profit-seeking Spanish conquistadors, Spain eagerly embraced the enslavement and forcible conversion of Indians as integral to its conquest of the New World. Many in Spain considered it "providential" that the discovery of America provided a "fresh supply of infidels"just as the country was completing the conquest and expulsion of the Spanish Moors in 1492.3 Consequently, missionaries were, by royal edict, a requisite part of every conquistadorial enterprise, and an active attempt was made to convert, civilize, and incorporate Indian laborers into the fabric of New Spain's social and economic structure. The political descendants of the Spanish, the Mexicans, continued in this tradition, finding that they had grown accustomed to and dependent on Indian labor

Compulsory Indian labor became pervasive and institutionalized in New Spain. Indian conquests who had survived the decimation of disease were heavily exploited in a series of regulated and unregulated

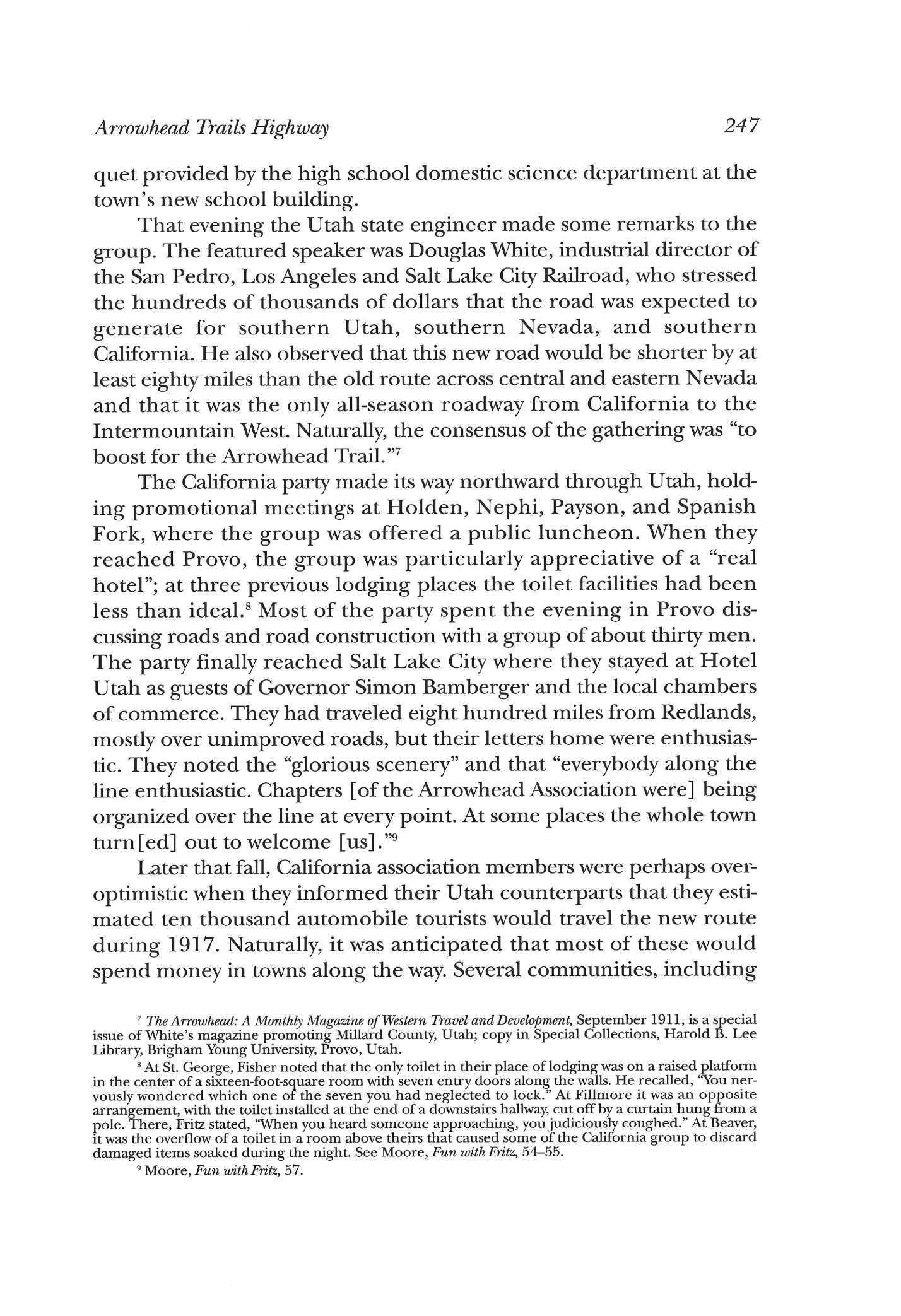

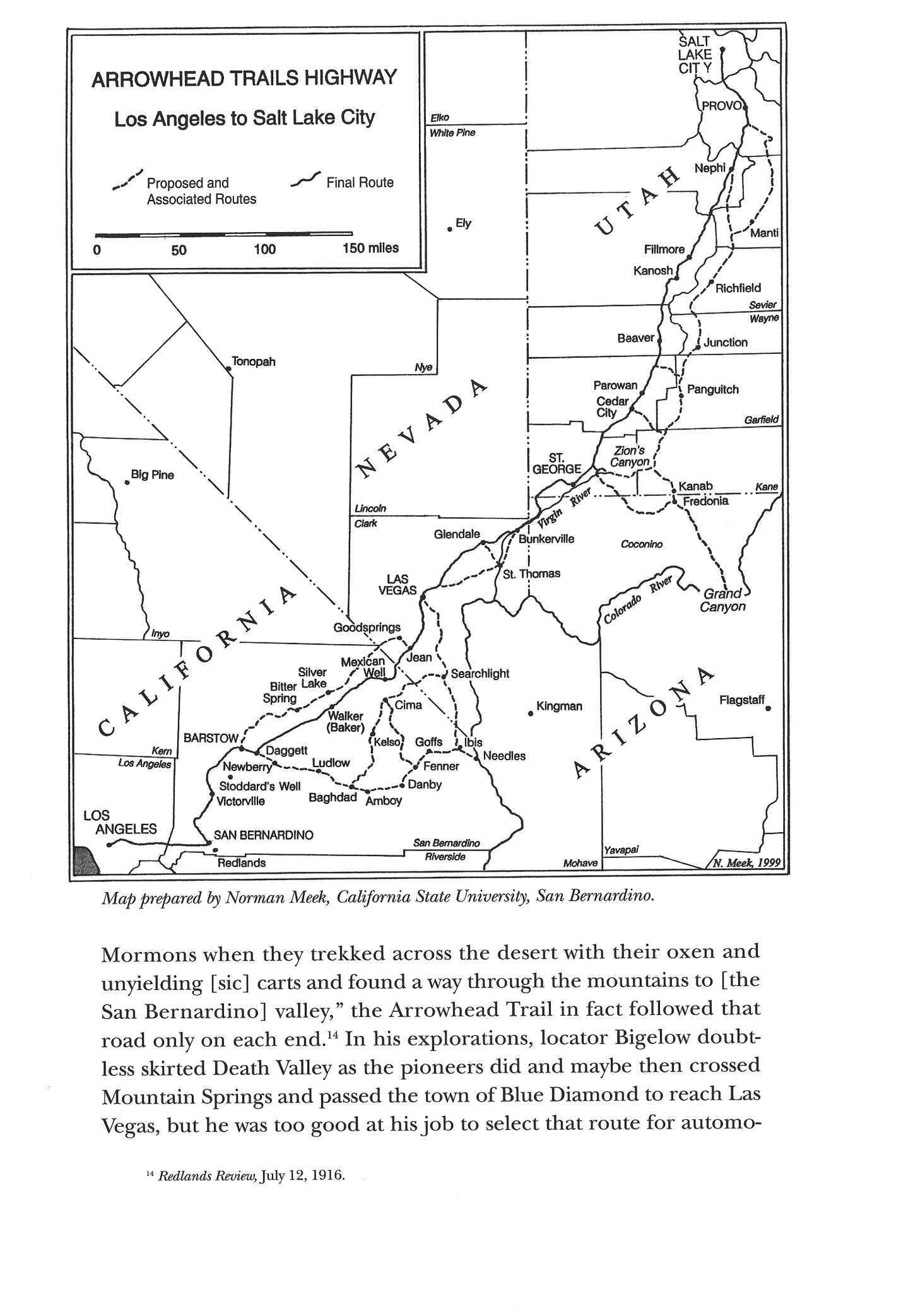

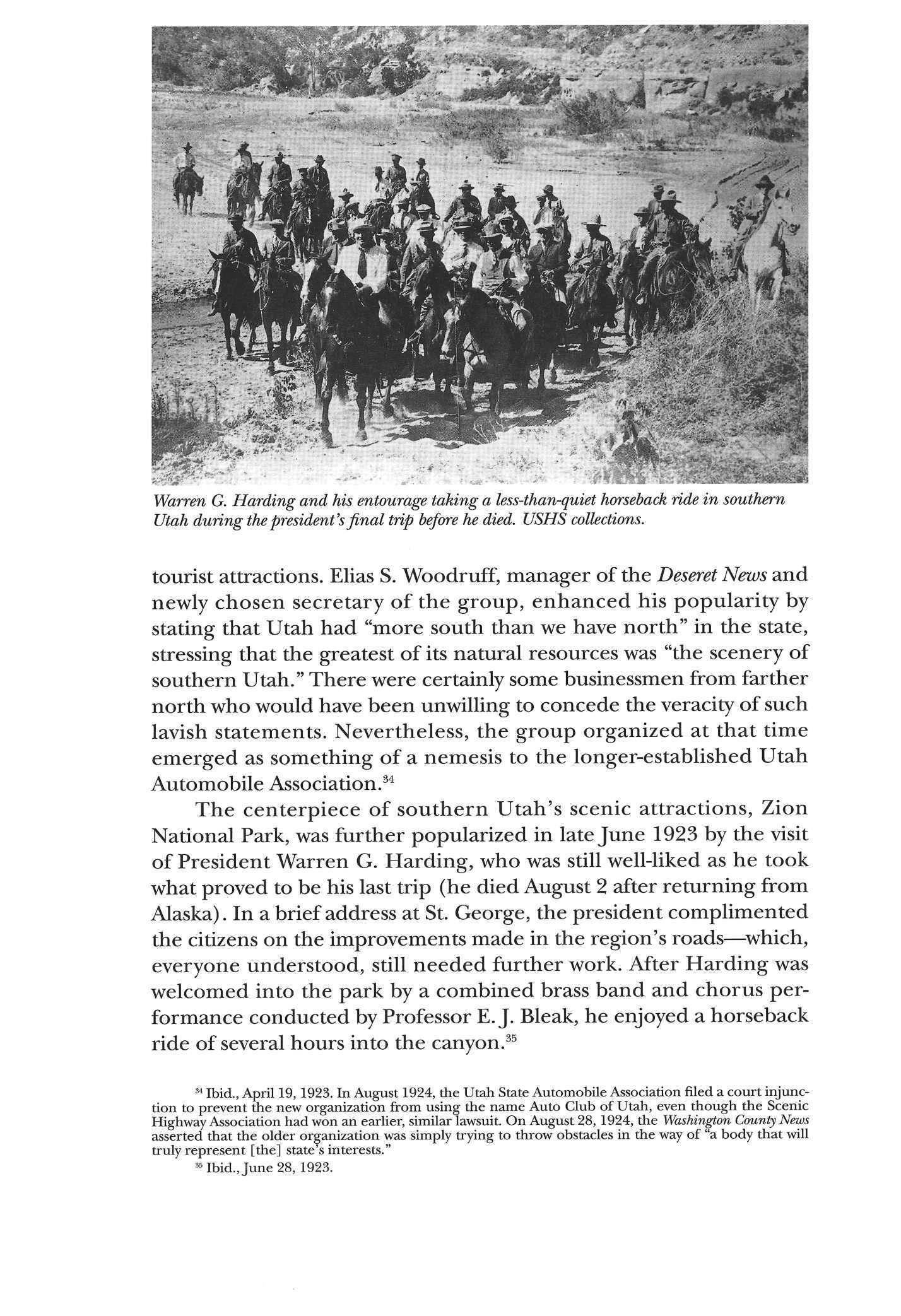

1 Descriptions of Indian slavery as practiced by all the colonial European powers can be found in Almon Wheeler Lauber, Indian Slavery in Colonial Times within the Present Limits of the United States (New York: Columbia University, 1913); Arrell Morgan Gibson, The American Indian (Lexington, Massachusetts: D C Heath and Company, 1980), 91-303; FrancisJennings, The Invasion ofAmerica: Indians, Colonialism, and the Cant of Conquest (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1975); Edmund S Morgan, American Slavery, American Freedom (New York: W W Norton & Company, 1975), Chapters 1-3; and L R Bailey, Indian Slave Trade in theSouthwest (Los Angeles: Westernlore Press, 1966).

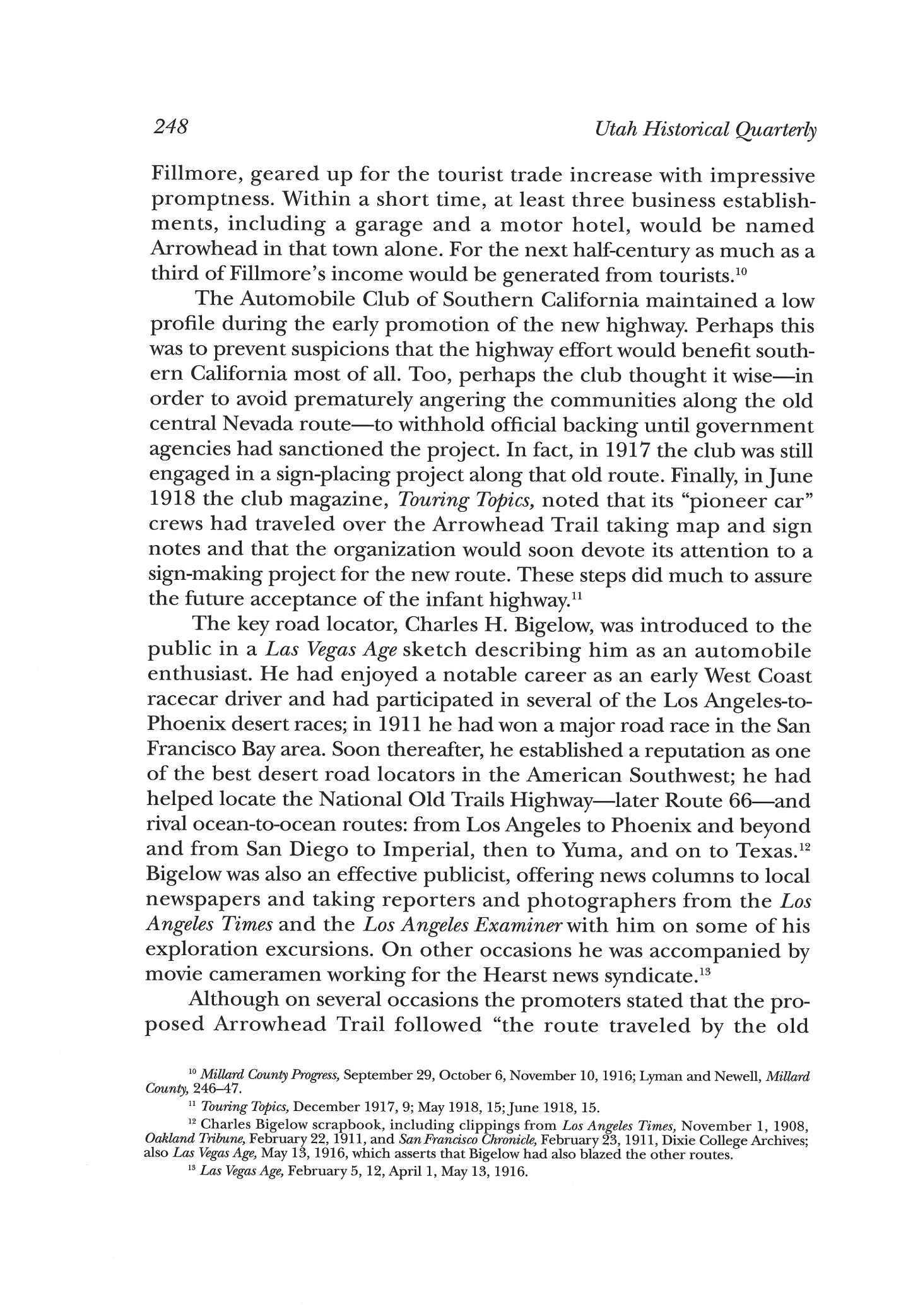

2 Cited in Gibson, TheAmerican Indian, 96

3 David J Weber, The Spanish Frontier in North America (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1992), 20-22

Indian Slavery 221

systems.4 Although explicit laws against Indian chattel slavery had been passed by 1589, the gathering of Indian slaves continued, and Indian labor systems were as often abused as were the Indian laborers themselves. It was difficult to regulate the practice of forced Indian servitude—especially far from the seat of government. Few local government officials cared about the laws or wanted to enforce them, since they themselves usually profited from the work of Indian captives.5 It was also difficult to control the practice where there was a great need for laborers, not only in mines but also in agriculture and domestic situations. Life was hard on the remote frontiers, and disease often claimed many of the family members who might otherwise have helped farm the land, herd the livestock, or work around the house. A shortage of labor, then, helped create a ready and ongoing black market for the Indian children who became a particular target of northern New Spain's slave traders.

Spaniards in the frontier settlements along the Rio Grande (today, New Mexico) acquired some of their captives through sanctioned and unsanctioned raiding expeditions against hostile tribes such as the Apache and Navajo. Other captives were purchased from Indian slavers such as the Utes and their cousin Comanches at annual trade fairs in Taos or Abiquiu or at established trade rendezvous. Captives obtained by the upper Rio Grande settlements met local labor needs and also supplied labor for the mines of northern Mexico.6

Most of the trade was reprehensible. Captives were usually taken violently in brutal raids in which their parents and relatives were killed Even "peaceful" trade was conducted under the threat of

4 The first of these systems was the direct enslavement of heathen conquests, allowed by papal decree for "enemies of Christ." Later, in the parceling of feudal labor estates known as encomiendas, a grantee was given rights to the labor of the serf-like Indians under his grant With the outlawing of encomiendas, the Spanish moved to the corvee labor of the repartimiento de indios, in which wage-earning Indian laborers were coercively apportioned to Spanish employers by government officials Though this system was also abandoned, the slave4ike, inheritable debt-labor of peonage and informal indentures still kept Indian workers tied to both vast hacienda estates and simple farms

By 1526 chattel slavery had been forbidden by Spanish law; by the mid 1500s compulsory Indian labor in mines had been abolished and the fief-like encomiendas forbidden; and by the late 1500s explicit Indian labor laws were being enacted Discussions and history of the institutional compulsory labor laws enforced in Spanish America can be found in Charles Gibson, The Spanish Tradition in America (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1968); Charles Gibson, Spain in America (New York: Harper and Row, 1966), 143—58; Weber, The Spanish Frontier, 123—29; Bailey, Indian Slave Trade, xi-xv; Ruth Barber, Indian Labor in the Spanish Colonies (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1932)

5 See, for example, Weber, The Spanish Frontier, 127-28

6 Weber, Spanish Frontier, 127-28. For a more extensive summary of slave acquistion, see Sondra Jones, "History of the Indian Slave Trade in New Mexico," in The Trial ofDon Pedro Leon Lujan: The Attack against Indian Slavery and Mexican Traders in Utah (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2000)

222 Utah Historical Quarterly

reprisals against those who refused to sell their children.7 Indian captors could be callous and cruel, and Mexican traders sometimes trailed children like animals for sale. Eyewitnesses in New Mexico reported seeing young girls raped on the public square by their Indian captors before they were sold at trade fairs.8 In Utah—long a rendezvous area for the Utes and their Mexican trading partners—observers gave abundant testimony concerning the poor treatment of captive children. These human wares were often abused, neglected, and starved by their Indian captors until they were "so emaciated they were not able to stand upon their feet"; according to observers, they were sometimes tied naked in the snow with bonds so tight their hands became swollen, tortured for revenge or amusement, or killed outright when they became a nuisance.9

However, once they were transported to New Mexico and purchased into Hispanic homes, the treatment of young captives was almost always good. While adult captives generally underwent a period of "domestication"—meaning corrective, disciplinary abuse—before they were considered good servants,10 most children, being tractable, were well-treated by their new owners. Indeed, most who purchased Indian children seemed to consider them to be foster children, and they were reared as such.11

Children were not always stolen; some were sold to non-Indians by their own parents or relatives, particularly on the frontier, where Indians

7 Agent Garland Hurt noted in 1860 that the Utes considered the "Pi-yeeds" (Paiutes) to be their slaves When possible, they purchased Paiute children, or they stole them by force when "disappointed" in their trade In 1854Jacob Hamblin talked to one Paiute chief who was forced to sell his only daughter to Utes who threatened to take their trade by force if he did not Hamblin also witnessed the bartering between the Ute chief Sanpitch and the Paiutes for children the Paiutes had previously stolen from a more distant tribe Garland Hurt, "Indians of Utah," Appendix O in J H Simpson, Report of Explorations across the Great Basin (Washington, D.C., 1876), 461; Jacob Hamblin, "Journals and Letters of Jacob Hamblin" (typescript MS at Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, original diaries located in LDS church historical archives), 28-29, 31,41

8 Serrano to Viceroy, 1761, in Charles W Hackett, trans, and ann., Historical Documents Relating to New Mexico, Nueva Vizcaya, and Approaches Thereto, to 1773, collected by A F A Bandelier and F R Bandelier (Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Institution of Washington, 1937), 487

9 Utah Territory, "A Preamble and an Act for the Relief of Indian Slaves and Prisoners," and "An Act for the Relief of Indian Slaves and Prisoners," in Acts, Resolutions, Chapter 24, passed January 31, 1852, approved March 7, 1852; Brigham Young, "Testimony," given in First District Judicial Court (of Utah), January 15, 1852, United States v Pedro Leon, et at, Doc #1533, 11-14, microfiche; and Minutes of the FirstJudicial Court, Salt Lake City, Utah, January 15, 1852, located in Utah State Archives; S N Carvalho, Incidents of Travel and Adventure in theFar West:With Col. Fremont's Last Expedition (New York, 1859), 193

10 See, for example, Serrano to Viceroy, 1761, in Hackett, Historical Documents, 487; Eleanor Adams and Fr Angelico Chavez, trans, and comp., The Missions ofNew Mexico, 1776: A Description by Fray Francisco Atanasio Dominguez with Other Contemporary Documents (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico, 1955), 252-53; Bailey, Indian Slave Trade, 128, and David M Brugge, "Navajos in the Catholic Church Records of New Mexico, 1694-1875," Research Report No 1, Navajo Tribe Parks and Recreation Department (Window Rock, Arizona, 1968), 129 Hispanic captives among the Navajo underwent a similar period of corrective abuse, after which their treatment became generally good For Navajo treatment of captives, see Brugge, Research Report 1, 117-34

11 Kirby Benedict, Chief Justice, New Mexico Supreme Court, in Congressional Joint Committee investigating the conditions of the Indian Tribes, May 2, 1865, as quoted in William J Snow, "Some Sources on Indian Slavery," Utah Historical Quarterly 2 (July 1929): 87-88

Indian Slavery 223

Utah Historical Quarterly

Paiute Indians sometimes lived at bare subsistence level, which at timesforced them to sell their children in order to survive. Lacking adequate arms and horses, Paiutes were often easy targetsfor Ute slave raids. Hitlers photo of Paiute wickiup, used by permission of NAA, Smithsonian Institution.

and settlers lived in close proximity

Some Indian parents bartered away their children because they saw better opportunities for them in the more prosperous non-Indian homes; such children might be sent off

with the admonition to learn much and return to their people later. Others were traded because they were simply a profitable and expendable commodity, because they were orphans and their relatives did not want to be bothered with them, or because their families suffered extreme poverty. This was sometimes the case with the Goshutes and the Paiutes, Shivwits, and Tonaquints of southwestern Utah and southern Nevada.12 One old Paiute in Utah noted that the tribe "could make more children but they had nothing else to trade for horses and guns."

13

12 For accounts of voluntary sales, see Juanita Brooks, "Indian Relations on the Mormon Frontier," Utah Historical Quarterly 12 (January-April 1944): 13-14; Jacob Hamblin, 'Journals and Letters of Jacob Hamblin," 27, 44;Jacob Hamblin, Jacob Hamblin: A Narrative of his Personal Experience (Salt Lake City: Deseret News, 1909), 32; letter from Jacob Hamblin printed in Deseret News Weekly, April 4, 1855; Juanita Brooks, ed., Journal of the Southern Indian Mission: Diary of Thomas D. Brown (Logan: Utah State University Press, 1972), 27, 60; Gwinn Harris Heap, Central Route to the Pacific (Reprint ed., Glendale, CA: Arthur H. Clark, 1957), 223-24; and Garland Hurt, "Indians of Utah," 461-62. Descriptions of the poverty of tribes such as the Paiutes, Goshutes, Shivwits, and Piede Utes are many in the literature of early western travelers.

13 William R Palmer, from oral interviews, MS in possession of W R Palmer estate, quoted in LeRoy R Hafen and Ann W Hafen, Old Spanish Trail: Santa Fe to Los Angeles (Glendale, CA: Arthur H Clark Co., 1954), 281-83

224

Indian Slavery 225

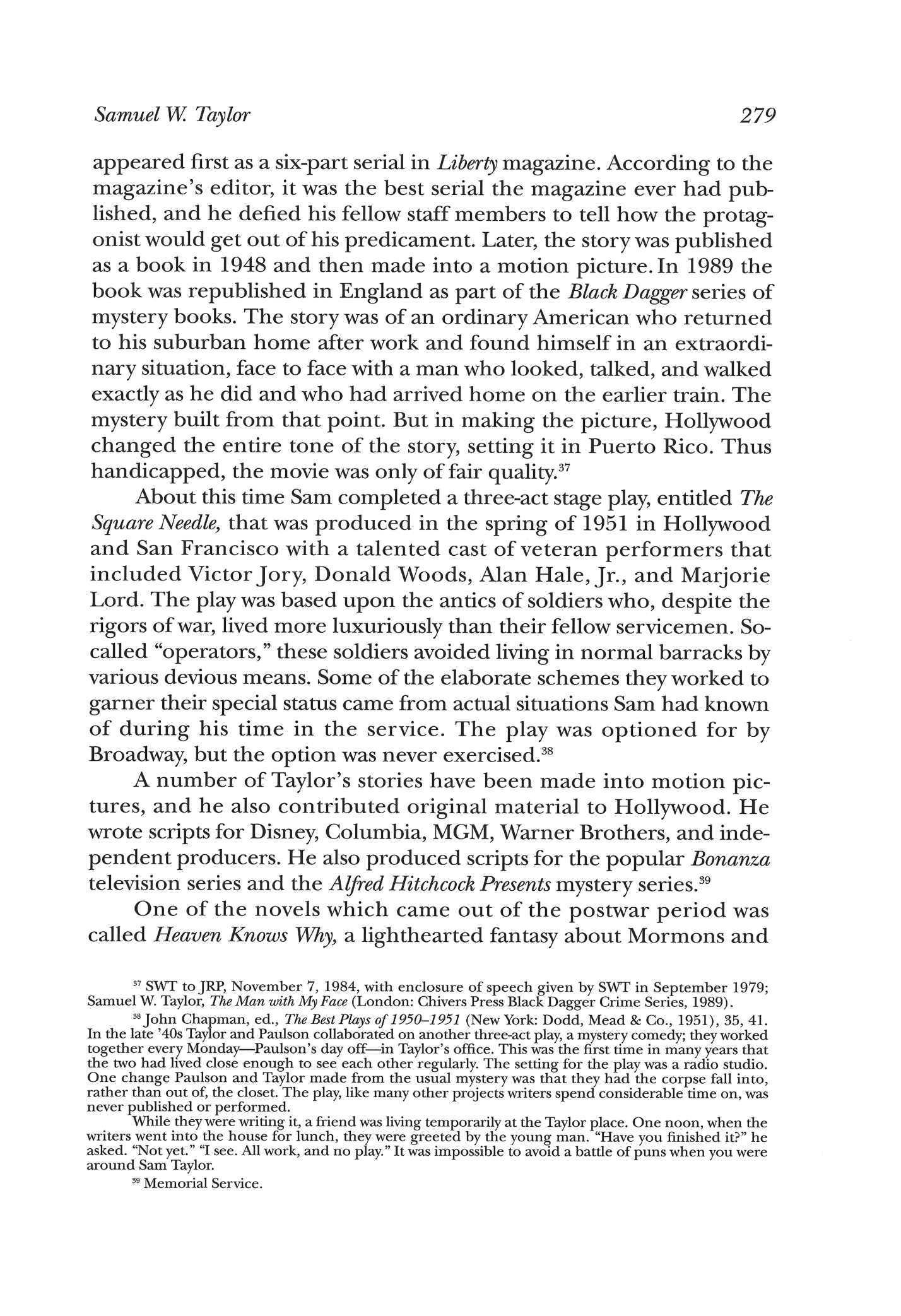

But even the wealthier Southern Utes of Colorado occasionally bartered their children to Spanish/Mexican settlers; Chief Ignacio was said to have traded a son for a horse, and the United States census and other investigatory reports of the 1860s show a number of Utes who had been acquired from other Utes being raised in southern Colorado's Mexican settlements.14