202

INTHISISSUE 204

A Young Man Goes West:The 1879 Letters of Leonard Herbert Swett

By

Dove

Menkes

220 “Places That Can Be Easily Defended”:A Case Study in the Economics of Abandonment During Utah’s Black Hawk War

By W.Paul Reeve

238

In the Footsteps of Timothy O’Sullivan: Rephotographing the 1869 King Survey in the Headwaters of the Bear River,Uinta Mountains

By Jeffrey S.Munroe

258 “In Deed and in Word”:The Anti-Apartheid Movement at the University of Utah,1978-1987

By Benjamin Harris 277 BOOK REVIEWS

Richard W.Etulain. Beyond the Missouri:The Story of the American West

Reviewed by Brian Q. Cannon

Sherman L.Fleek. History May Be Searched in Vain:A Military History of the Mormon Battalion Reviewed by M. GuyBishop Richard T.Stillson. Spreading the Word:A History of Information in the California Gold Rush

Reviewed by John Barton

Sandra Ailey Petree,ed. Recollections of Past Days,The Autobiography of Patience Loader Rozsa Archer

Reviewed by Audrey Godfrey

David P.Billington and Donald C.Jackson. Big Dams of the New Deal Era:A Confluence of Engineering and Politics

Reviewed by Jared Farmer

William A.Wilson. The Marrow of Human Experience:Essays on Folklore

Reviewed by Polly Stewart

UTAHHISTORICALQUARTERLY SUMMER2007 • VOLUME75 • NUMBER3

© COPYRIGHT 2007 UTAH STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY

286 BOOKNOTICES 292 LETTERS

Our perspectives are influenced by many factors—age,education, upbringing,experiences,to name just a few.As we seek to learn more about Utah’s past,fresh perspectives are always welcome.The first article for our summer issue offers just such a perspective.The twenty-one-year-old Leonard Swett made his first trip West in 1879 as a member of a United States Geological Survey expedition conducting scientific studies of the remote Colorado Plateau of southern Utah and northern Arizona.In a series of letters written to his parents in Chicago,Swett provides interesting insights about nineteenth-century Utah and Utahns as he describes his stays in Salt Lake City,Nephi,Cove Fort,Beaver,and Kanab.

The events of Utah’s Black Hawk War that began in 1865 have been carefully documented.Our second article goes beyond an account of the causes,the raids,the pursuits,and the deaths to examine the economic impact of the war on the southwestern Utah settlements of Clover Valley, Shoal Creek,and Hebron when Brigham Young ordered the abandonment of outlying communities on the Mormon frontier.The policy created immediate economic and social hardships,especially for small and isolated settlements.However,abandonment and relocation also offered potential advantages that emerged in the aftermath of the Black Hawk War.

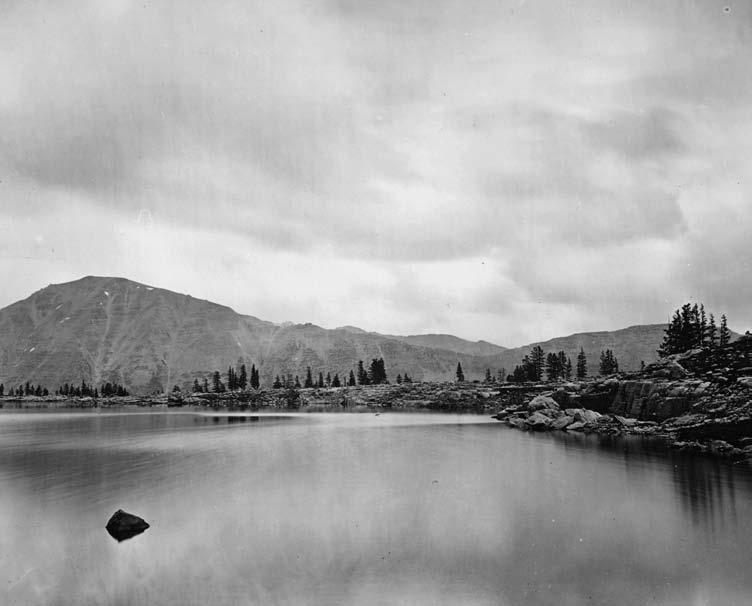

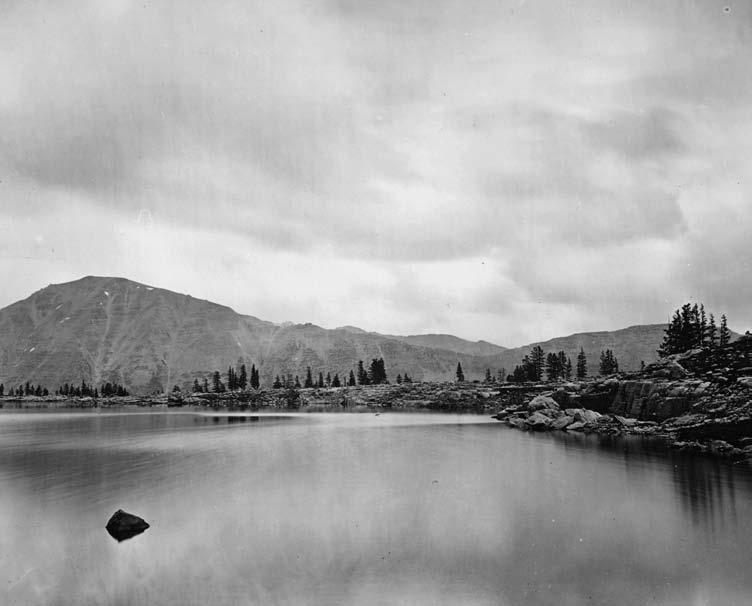

At about the same time Mormon settlements south of Utah Valley were being abandoned and consolidated under the threat of attack by the Ute leader Black Hawk,Clarence King conducted a reconnaissance survey of the north slope of the Uinta Mountains in northeastern Utah along the UtahWyoming border as part of the United States Geological Exploration of the 40th Parallel.Timothy O’Sullivan,photographer for the survey,captured the

202 INTHISISSUE

SHIPLERCOLLECTION, UTAHSTATEHISTORICALSOCIETY

majesty of the pristine wilderness in photographs he took in August 1869. Beginning in 2001,photographer and author Jeffrey S.Munroe,returned to the Uinta Mountains to relocate and rephotograph the scenes first recorded by O’Sullivan.We invite you to make an arm-chair summer trip to the Uinta Mountains to study the one-hundred-thirty-eight-year-old O’Sullivan images and compare them with the recent photographs to see what has remained the same and what has changed during the intervening years. When agents of the Dutch East India Company first landed on the southern tip of the African continent in 1652,their interaction with native Africans began a three-hundred year process that culminated in an official policy of apartheid by the South African government in 1948.In the aftermath of the horrendous legacy of the recent Holocaust in Europe and with the seeds of a civil rights movement beginning to germinate in the United States,the discrimination and racial separation that characterized apartheid in South Africa seemed to go against the forces carrying the nations of the world toward a more humane and enlightened treatment of all citizens.The struggle over apartheid was intense,bitter,and,at times,deadly. As our final article in this issue illustrates,the anti-apartheid campaign reached all the way from South Africa to the campus of the University of Utah as protesters challenged the propriety of the school owning stock in companies that supported apartheid in the troubled African nation.After a series of petitions,demonstrations,protests,lawsuits,and arrests,the University of Utah Institutional Council voted in 1987 to divest the university’s stock in companies that supported apartheid in South Africa.Seven years later,the official policy of apartheid ended with the 1994 election of Nelson Mandela as president of South Africa .

LEFT: Visitors to Canyon Crest (Bountiful Peak) in Davis County May 14,1906.

ABOVE: A forest ranger on the Mt.Timpanogos trail in 1930.

ONTHECOVER: This scene in City Creek Canyon was photographed on July 12,1916.

PHOTOCREDIT:SHIPLER COLLECTION, UTAH STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY

203

UTAHSTATEHISTORICALSOCIETY

A Young Man Goes West:The 1879

Letters of Leonard Herbert Swett

BYDOVEMENKES

In 1879,twenty-one year old Leonard Herbert Swett left his upperclass Chicago home for Utah where he became a member of a United States Geological Survey expedition sent to continue the study of the Colorado Plateau.The scientific study of the Colorado Plateau began a decade earlier when John Wesley Powell and his men undertook their heroic journey down the Green and Colorado Rivers and through the Grand Canyon in 1869.Powell made a second expedition of the Green and Colorado Rivers in 1871-1872,when he established the survey base in Kanab from which later systematic topographic and geological surveys of the Colorado Plateau were conducted.1

Powell was besieged by requests from individuals for positions with his survey.Some requests were from people with relevant training or experience.Others were motivated by the possibilityof travel and

C.D.Walcott,geologist with the 1879 USGSexpedition.

Dove Menkes is a retired aerospace manager who has researched the history of the Colorado Plateau for more than thirty years.He is a coauthor of Quest for the Pillar of Gold:The Mines & Miners of the Grand Canyon published in 1997 by the Grand Canyon Association.The author thanks the staffs of the Huntington Library, the Fullerton Public Library,and the Utah State Historical Society Library for their help.

1 John Wesley Powell continued his investigations as The Geographical and Geological Survey of the Rocky Mountain Region.In March 1879 his survey and those of others including Clarence King, were organized as the United States Geological Survey.Clarence King was named the first director of the survey,while John Wesley Powell became the first director of the Bureau of American Ethnology, which was established at the same time.In March 1882,King resigned and Powell was appointed director of the United States Geological Survey.For diaries,documents,and biographical sketches relating to John Wesley Powell and his exploration of the Colorado Plateau see “The Exploration of the Colorado River in 1869,” Utah Historical Quarterly 15 (1947);“The Exploration of the Colorado River and the High Plateaus of Utah in 1871-72,” Utah Historical Quarterly 16-17 (1948-1949);and “John Wesley Powell and the Colorado River Centennial Edition,” Utah Historical Quarterly 37 (Spring 1969).Three excellent accounts of John Wesley Powell’s work include:William Culp Darrah, Powell of the Colorado (Princeton,NJ:Princeton University Press,1950);Wallace E.Stegner, Beyond the Hundredth Meridian: John Wesley Powell and the Second Opening of the West (Boston:Houghton Mifflin,1954);and Donald Wooster, A River Running West:The Life of John Wesley Powell (Oxford:Oxford University Press,2001). For a comprehensive bibliography of works about John Wesley Powell see,“A Bibliography of the Grand Canyon and Lower Colorado River,”http://www.g randcanyonbiblio.org

204

SMITHSONIANINSTITUTIONARCHIVES

adventure.Still other requests came from politicians such as Illinois Senator David Davis,on behalf of their constituents and supporters.In his letter of January 29,1879,Davis wrote to Powell:“A young friend of mine in Chicago,is very anxious to go with Some Government Surveying party going upon the plains in the Spring.His Father writes me ‘he is a good mathematician and understands geometry,trigonometry and surveying very well for one of his age,(about 20,) his habits are good and he is an agreeable companion.’”The senator then came to his request.“I would like to assist him if I could in his desire.Do you know of any surveying party going out this Spring and what are the prospects? Any suggestions you can give me in this direction,will be thankfully received.”2

Leonard Herbert Swett was born to Leonard Swett and Laura Quigg Swett in Bloomington,Illinois,on November 11,1859.He was an only child of a warm and loving family.He attended Phillips Exeter Academy in 1875-1876.His father was a prominent attorney in Bloomington from 1848 to 1865,and then practiced law in Chicago from 1865 to 1889.He was a friend and confidant of Abraham Lincoln.Young Swett was from a family of privilege,with high connections.3

Powell responded to Senator Davis that a position was available for Swett, who in turn informed young Swett in person of his good fortune in early July 1879.Swett wrote Powell on July 9 indicating that “I have been informed by Judge David Davis—who has recently been here—and by Mr. Wickizer that I am to go with you upon your expedition to the West.” Swett continued the letter with three questions:“…when you will start…what outfit I will require,and where you will go.”4

Leonard Swett left Chicago by train for Salt Lake City on July 22,1879, with four other individuals:Sumner H.Bodfish of Washington D.C.,a topographer in charge of the survey,Charles D.Walcott,a geologist from New York,Richard Urquhart Goode,the son of Congressman John Goode of Norfolk,Virginia,and Philo B.Wright,who also joined the group at Chicago.5

2 Letter,David Davis to John Wesley Powell,January 29,1879,in Letters Received by John Wesley Powell,Director of the Geographical and Geological Survey of the Rocky Mountain Region, microfilm series,MC 156/9 , National Archives,Washington,D.C.Senator Davis had been a lawyer from Bloomington,a circuit judge in Illinois,a colleague of Leonard Swett,and a supporter of Abraham Lincoln. In 1862 Lincoln appointed him to the United States Supreme Court where he served as a Supreme Court Justice until 1877 when he left the court to become a United States Senator from Illinois.

3 For information on the Swett family,see Leonard Herbert Swett,“A memorial of Leonard Swett,a lawyer and Advocate of Illinois,”in Transactions of the McLean County Historical Society of Bloomington Illinois 2 (1900):332-65,Huntington Library,San Marino,California;and Samuel Paul Wheeler,“New England’s Son:Leonard Swett and the American Struggle,1825-1850”(Master’s Thesis,University of Illinois, Springfield,2002).

4 Letter,Leonard Swett to John Wesley Powell,July 9,1879,Records of the Bureau of Ethnology, Correspondence,“Letters Received 1879-1888,”National Anthropological Archives,The Smithsonian Institution,Washington,D.C.

5 Charles Doolittle Walcott,(1850-1927) was hired in 1879 as an assistant geologist,and later became Director of the USGS,then Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution.Sumner Homer Bodfish (1844-1894) was born in Massachusetts.He joined the Union Army in 1863 and served in the infantry and artillery.He

205 LEONARDHERBERTSWETT

Swett wrote nine letters to his mother between July 23 and August 18, 1879.Proud of his son and his writing skills,the elder Swett provided copies of some of these letters to the Chicago Times newspaper that published excerpts of them in a lengthy article on September 3,1879.In a letter to his son dated September 6,Swett wrote:“We have sent your printed letter every where you had friends so far as we could think.For instance Grandmother…Maj.Powell,Wickizer….All your friends complement me upon the neatness & style of it & like it.”6

A month later,Swett’s father wrote: We have received a bushel of literature from you lately and all of us are very greatly obliged for it.I have no more right to flatter you than if you were not my son and do not intend to do so;it is however but justice to say that your books containing the diary of events from Salt Lake to Kanab and also from Kanab to the present time are as interesting and well prepared as any diary I have ever read.The beauty about them is that all the little threads of each day have been honestly gathered up and the story is told simply and without any effort to exaggerate,and consequently it is very natural and interesting. I am inclined to believe,if you persevere,you can make a book upon your return which will bear publication and pay you something.7

Leonard Swett’s description of his travel,his impressions of Salt Lake City, Nephi,Cove Fort,Beaver,Fort Cameron,and Kanab,along with his personal experiences with a variety of Utah residents offer an interesting and revealing glimpse into life and people in late nineteenth century Utah. Written with the innocence and enthusiasm of an adolescent,Swett’s letters convey the workings of a government scientific survey team in the aftermath of the initial work done by John Wesley Powell and his men a decade earlier.

Swett’s excerpted letters from Utah published in the Chicago Times is headlined “Among the Mountains,”followed by a series of attention getting subheadings:“A Young Chicagoan’s Account of the Trip of the U.S.G.Survey to Southern Utah”;“Some of the Beauties of Utah Scenery as Seen on the Trip from Salt Lake to Kanab”;“A Model Frontier Hotel with its Appointments and Adornments”;“The Way the Women Run Things on Election Day in Beaver”;“The Glories of a Summer Sunset Among the Pink Cliffs;”and “The Frontier Dandy and the Pleasant People He Has Met.” “Among the Mountains”is introduced with the following short paragraph.

A Young Chicagoan’s Account of the Trip of the U.S.G.Survey to Southern Utah Some of the Beauties of Utah Scenery as Seen on the Trip from Salt Lake to Kanab....The follow-

received an appointment to West Point from President Lincoln and graduated in the class of 1868.From 1871 to 1878 he worked as a civilian engineer when he joined the Powell Survey as a topographer.Later he worked for the Irrigation Survey and in private engineering practice.Richard Urquhart Goode (18581903) was the son of Virginia Congressman John Goode.He attended the University of Virginia,and in 1877 and 1878 worked in the Army Engineer Corps.He joined the USGS in the Division of the Colorado under Bodfish in 1879.Philo B.Wright was a topographer.

6 Leonard Swett’s September 6,1879,letter to his son is in the Swett Family Correspondence HM 50227-50449,Huntington Library,San Marino,California.For all items quoted,I have made only minor changes in format and punctuation for clarity.Words that could not be deciphered are indicated by [ ].

7 Swett Family Correspondence,Huntington Library.

UTAHHISTORICALQUARTERLY 206

ing letters were written by Leonard H.Swett who is a member of the United States geographical and geological survey, now in northern Arizona and along the banks of the Colorado river.The party to which he belongs design to finish up the work commenced by Maj.Powell in his explorations of the Colorado several years ago.Mr. Swett is the son of Leonard Swett,and the letters from which extracts have been made were written to his mother.The party left Chicago on July 22.8

ON THE ROAD

Glenwood,Iowa,July 23, 1879 – DEAR MOTHER: Yesterday was simply an ordinary ride in a railroad car,but was pleasant,and devoted to forming acquaintances among our party,who were generally strangers to each other.Col.Bodfish,of Washington,who is in charge and takes general supervision of everything;Mr.Wolcott,of New York,the geologist;Mr.Goode,son of Congressman Goode of Norfolk,Va.;Mr. Wright,who joined us at Chicago,and myself,at present constitute the party.

1873.JohnWesley Powell is second from the left. Photo by J.Hillers.

I know nothing yet of our destination,except that we are going to northern Arizona and the Colorado river,and nothing of the objects of the expedition except that it is to be devoted to geological and geographical surveys.Mr.Wolcott was out last year with Clarence King;Mr.Wright is about twenty-four years old,and was with Col.Bodfish last year;Mr.Goode was upon the surveys last year in North Carolina,but has never been to the mountains,and I,as I need not tell you,am a green hand from top to bottom.We shall go to Salt Lake and thence by rail as far as we can and then to Arizona,but how,I do not know.

SALT LAKE

SALT LAKE CITY,July 25.At last after a long but pleasant ride,we are at Salt Lake City.We arrived last night about 8:20.I was very tired and am

207 LEONARDHERBERTSWETT

8 Microfilm copy of the Chicago Times available at the Chicago History Museum,Chicago,Illinois..

Members of the Powell Party in the Kaibab Forest of Northern Arizona in

GRANDCANYONMUSEUM

yet,but am well otherwise.We shall leave here Sunday or Monday and travel one hundred and twenty-five miles south by the Utah Southern railway, thence by stage about one hundred and fifty miles to the place where we shall “outfit,”as they call it,and then set out for somewhere upon mule-back.At Colorado Junction we met another member of the expedition,Mr.Phillips of Kansas.9 He is about twenty years of age,and his appearance is prepossessing.Our party has this morning been to the United States signal office at work with the barometers,and I have been purchasing a few things for camp life.The baggage will be limited to one valise each besides blankets.Everybody brought trunks,but we leave them here,and in a few minutes I expect Col.Bodfish will come up to my room and tell me, out of a trunk full,what few things I may take.

Col.Bodfish keeps his plans to himself,but I think another person is to join our party,and when we “outfit”that Mr.Wolcott,the geologist with one cook,will go alone and the rest will be divided into two parties,one under Col.Bodfish and the other commanded by a Mr.Renshaw,who was with Maj.Powell in his earlier expeditions.10 This evening we shall go over to Salt Lake and have a swim.The bathing place is about eight miles away, but we go by cars at 5 o’clock and return at 9.Salt Lake valley is about forty miles wide,and the mountains rise grandly on either side.The weather is hot and it is very dusty,as this season there is little or no rain.I had no idea that fifteen hundred miles was so long a ride.It is,I believe,the longest consecutive ride by rail that I have ever taken.

AT NEPHI

Nephi,Utah Territory,July 29.– We are off at last,and Salt Lake City is a thing of the past.My visit was as pleasant as I could have desired had I been allowed to plan it beforehand.I bathed in the waters of the Great Salt lake, rode over the city and out to Camp Douglas with the most delightful of companions,a young lady whose acquaintance I made since leaving home.I attended the Mormon church,theatre,base ball,and “did”the city generally. As I arrived Friday and left Monday,you will see I have been busy and have had a season of pleasure.

When we left Salt Lake we intended to go directly to Chicken Creek,the southern terminus of the Utah railroad,and there take the stage for Beaver, where we “outfit,”but upon the train we learned that we could not all get seats in today’s stage,so Mr.Wright,Mr.Goode,Mr.Phillips and myself got off the train fifteen miles from the stage station,and will wait until tomorrow.We stay here because it is a better place to spend the night than Chicken Creek.11 I am glad to have one uninterrupted night’s rest after my

9 Colorado Junction is six miles west of Cheyenne,Wyoming,where the Union Pacific Railroad meets with the Colorado Central Railroad.James S.Phillips shows up only once in USGS records for 1879.

10 John Henry Renshawe (1851-1934),was born in Illinois.After teaching school,he was with John Wesley Powell and the USGS from 1872.He retired from the USGS in 1925.

208

UTAHHISTORICALQUARTERLY

round of visitation at Salt Lake,and as the stage ride is to be one hundred and twentyfive miles,and to occupy thirty-six hours,I want to get well rested for it.

Nephi is a very small village about 100 miles south of Salt Lake.It is at the foot of Mount Nebo,one of the most prominent peaks of the Wasatch range,and twelve thousand feet high.

I have rolled up my overcoat,one pair of pants and a rubber blanket in my bed blankets,and these,with a valise full,are all the clothing I am to have.

The road from Salt Lake to Nephi is pleasant and the Salt Lake valley,with the great Wasatch mountains resing on either side,constitutes an ideal picture of pastoral beauty.The valley is very fertile and generally covered with wheat.Green pastures with great herds grazing upon them intervene, and the landscape of the ripe and the green is set by the mountains as the frame is set in the picture.Part of the way the road runs in sight of Utah lake,a body of fresh water twenty-five miles long by twelve wide,and the scene of fields,meadows and mountains,as the train like a weaver’s shuttle passed them,was soothing and restful.

Mr.Bodfish has just telegraphed for our party to come on without fail to-morrow.All I know of the expedition more than I have stated,is that the barometer has been assigned to me,and I understand my work generally will be to read it and make proper records and reports.We know that one of our party is to be left with one cook in a canon of the Colorado river,5000 feet deep,to read and report the barometer once in two hours,every day for three months.Naturally we are all interested to know who is to be detailed to this solitude.The others will be divided into two parties,and we are wondering and guessing who will go with Mr.Renshaw and who with Col.Bodfish.I am in fine health and greatly pleased with the party.

STILLATNEPHI

NEPHI,Utah Territory,July 30.We do not leave here until noon so I have time to write you again.Our hotel is just the smallest little place I ever got into,but the people are all cordial and talkative,so I am having a pleasant time.

As one enters the house he comes directly into the sitting-room,which is

11 Chicken Creek was established in 1860 and was the location for John C.Widbeck’s Overland Stage Station.When the Utah Southern Railroad reached Chicken Creek in 1876 the settlement was renamed Juab.As the railroad extended further south,Juab became less important and was finally abandoned.See John W.VanCott, Utah Place Names (Salt Lake City:The University of Utah Press,1990),208.

209 LEONARDHERBERTSWETT

Sumner Homer Bodfish. USARMYMILLITARYHISTORYINSTITUTE

covered with a rag carpet and furnished with an old fashioned wide sofa covered with a bright quilt and pillow to match.There is also a wooden table with leaves,a few wooden chairs,a stove and a high mantel shelf.It is neatly papered and the walls covered with prints.“A Storm at Sea,”Scott’s “Lady of the Lake”with her red dress,black waist and Scotch cap and the verses of “The Silver Strand”and the hunter leaving “his stand,”underneath. Froiseth’s large map of Utah and a general map of the west,prepared by a manufacturing company at Racine.These,with the illustrated advertisements of a mowing-machine complete the furniture of the room.The stairs lead up to the second story from this room without any hall.Upstairs the ceiling is so low that I can touch it in the highest place.Here there are three beds and windows not four feet square.Of course the people here do not know how to cook well,but that is nothing as I am so well I can eat almost anything.

The words “U.S.G.survey”are in this country equivalent to the “open sesame”of the Arabian Nights.Last night at the post office I engaged in conversation with the assistant postmaster.When I told him I was going to Arizona he asked me if I was an emigrant,but when I said “U.S.G.survey” that altered everything.He invited me into the back part of the post-office and introduced me to the postmaster,who was very civil and treated me to some lemonade and all the luxuries of his back-room.

We start soon,and I will write you again from Beaver and tell you how I stand the thirty-six hours’stage ride.

A STAGE RIDE TO BEAVER

Beaver.Utah territory.July 31,two hundred and fifty miles south of Salt lake.– We left Nephi yesterday at 11:50 A.M.,and after fifteen miles’ride by rail,took a dinner at Chicken Creek and at 1:15 P.M.left by stage for this place.The ride was not as long as I supposed,being only twenty-six and one-half hours and the distance one hundred and twenty-five miles.We stopped twice to change horses and half an hour for supper at 8 o’clock and then rode until 1 at night when we stopped six hours,leaving at 7 in the morning and dining at 12 o’clock at a Mormon fort which was built in 1867 to protect the neighboring farmers from the Indians.12 From there we came directly through,arriving at 3:30 P.M.I was tired when the journey ended but not as much so I expected to be and this evening I am feeling quite well.

Our stage was a small one of Abbot,Downing & Co.’s make,of Concord, N.H.,and our party of four were the only passengers.The ride was very dusty for the first fifteen miles but then it rained just enough to lay the dust. You may judge how dusty it was when I tell you this was the first rain that had fallen for four months.

12 “Mormon fort.”Located twenty-five miles north of Beaver at the present junction of Interstate 15 and Interstate 70 it is better known today as Cove Fort.

210

UTAHHISTORICALQUARTERLY

At one o’clock at night we stopped six hours until 7 in the morning.Our party and a strange man all occupied one room.The stranger slept on the floor while the four occupied two beds. When I awoke in the morning at a quarter past 6, the stranger had gone and the floor having been left open,there was a little fawn snuffing about the room.

The Mormon fort was built of stone and square, the walls being about five feet thick and twenty feet high.Inside this wall and perhaps fifteen feet away from it there is an interior wall about the same height which goes around the entire square formed by the outer wall except at the gates.These two walls are joined by a roof and formed a house where the people who farmed the surrounding country might gather at a moment of danger.The intention in constructing the fort was to have the space between the outer and inner walls to be occupied by men fighting Indians,who might surround the fort,while their families would be inside the interior wall and thus protected.So far as we know there are no hostile Indians in the country now,but a few years ago there were. 13 The scenery coming from Nephi is not fine.The Rocky Mountains are approached by high table-lands,so that the mountains whose summits are eight or nine thousand feet above the sea do not seem to be mountains at all,or,at least are very tame.The ground is covered with sage-bushes of a drab-green color and about a foot high,and the sides of the mountains are mostly bare.The soil is white and very poor because it is so dry;but wherever water can be procured from the mountains for the purposes of irrigation,everything can be raised in abundance.The surface of the country,as one looks out upon it,is that of a desert,except where green fields produced by irrigation intervene.The air is so dry that when an animal dies it dries up,and there is scarcely any odor.I saw the remains of three or four horses that had died,and their bodies were slowly drying up,

13 For an account of the most serious encounter between Indians and Mormon settlers see John Alton Peterson, Utah’s Black Hawk War (Salt Lake City:The University of Utah Press,1998).

211 LEONARDHERBERTSWETT

NATIONALANTHROPOLOGICAL

John H.Renshawe

ARCHIVES

leaving only the bones.I had to use some vaseline I happened to have with me almost constantly for two days to keep my nose and lips from cracking.

ARMY LIFE AT FORT CAMERON

KANAB,Kane County,Utah Territory,Aug.12 –

The last part of my stay at Beaver was very pleasant,for I formed several new acquaintances there.

Sunday evening,Aug 3,I was going to the Mormon church with “Mormon Joe,”one of the packers,we stopped to talk with a group of soldiers from Fort Cameron,and among them I found Mr.Edwards from Bloomington,who knew father and had heard him speak.On Monday,at his invitation,I visited him at the fort,and found him at work in his shop for he is shoemaker for company “C.”I spent the afternoon with him and stayed to supper,where I ate with about forty soldiers at a long table.We had stewed apples,hard-boiled eggs,bread and butter,and a bowl of coffee for each.During my stay at the fort,I met Lieut.Goodwin,also from Bloomington.He proved to be the Percy Goodwin for whom father,about 1861,procured a position as page in congress,and who took care of me when I was sick in Washington.He is 30 years old and has a wife and a beautiful little daughter.I promised to dine with him the next day,and then walked back to town with Edwards.That evening I went to a ball and stayed until 12 o’clock.Having a note-book with me I assumed the role of a reporter,and thus got a place upon the platform with the musicians and a chance to ask questions.The last hour I spent talking to a Mormon who was explaining to me the attractive features of the Mormon religion.He has been county clerk of Beaver county for fifteen years,and is reputed to be a good man.14

I forgot to say that election took place while I was there,and an eventful day it was for Beaver.I knew one of the judges of the election and the postmaster,and through them was invited into the room where the ballot-box was kept,and talked politics for an hour or more as well as I could.Out here the women vote,and I saw whole families come to the polls together.One woman was so enthusiastic that she brought her wagon three times full of women.15

The next day Lieut.Goodwin came for me with a post-ambulance and I went to dine with him at the fort.There I met Mr.Harry Douglas,son of

14 William Fotheringham served as Beaver County Clerk from 1866 to 1884.He was born in Clackmannan,Scotland,on April 5,1826,and joined the Mormon church in 1848.He was one of the first settlers of Lehi in 1850.From 1861 to 1864 he presided over the LDS mission in South Africa.Andrew Jenson, Latter-day Saint Biographical Encyclopedia 4 vols.(Salt Lake City:Andrew Jenson History Company, 1914),2:190-192;and G.Merkley,ed, Monuments to Courage:A History of Beaver County (Beaver:Daughters of Utah Pioneers,1948),176.

15 The Utah Territorial Legislature granted women the right to vote in 1870.For accounts of early women suffrage in Utah see,Carol Cornwall Madsen,ed. Battle for the Ballot:Essays on Woman Suffrage in Utah,1870-1896 (Logan:Utah State University Press,1997).

212

UTAHHISTORICALQUARTERLY

the commandant,who is about to enter West Point and had just returned from the east.

After dinner we sat on the veranda until “retreat,”when the sunset-gun was fired and the officer of the day received the reports from the different companies,and the bugle-calls were sounded.We then walked to what is called the “park.”Just south of the fort is a willow grove with a beautiful mountain stream full of trout running through it.It has been improved and has several cascades,a lake,rustic seats,etc.After our return the little Goodwin girls and their mother sang for us,accompanied by a parlor organ. Soon after we were joined by Col.and Mrs.Douglas and Capts.Crouse and Burke.16

Fort Cameron was built by Col.Sheridan in 1872,and is one of the prettiest forts in the west.All the officers’houses are constructed of volcanic stone,which is a mottled gray,and each has its yard and flower-beds,so that the view is very picturesque.The fort is in the form of a hollow square,with a large parade-ground in the centre sown with grass;and,directly in the rear,tall mountains add much to the beauty of the view.

I shall not in a long time forget Fort Cameron,with its pleasant people, and hope to revisit it if we should return by way of Beaver.

When I left,my new acquaintances gave me little mementos.Edwards gave me a badge of the 14th infantry,and the little Goodwin girls a bouquet.The druggist wanted to treat me to champagne,and,as I declined, he insisted I should bear away some substantial gift,and so presented me a large box of diarrhea pills.In this country,considering its bad water,such a token of friendship is not to be laughed at,but is the evidence of real and sincere fondness.

The influential manager of the “mint saloon,”and the postmaster,also, wished me “luck”as we departed,and thus cheered and sustained by these

16 Lt.Col.Henry Douglas was commander of Ft.Cameron.

213

Fort Cameron Officers’Barracks.

UTAHSTATEHISTORICALSOCIETY

new and sincere friendships,we marched slowly over the unknown desert that spread out its hills and valleys before us and Beaver faded from my view.

FAR UP IN THE MOUNTAINS

KANAB,Utah Territory.Aug 13.There were twelve in our party from Beaver,and we made quite a procession as we started into the desert.There were eight upon mules and four in a wagon drawn by two mules and two horses.The first night we stopped at Fremont pass.The wagon was loaded heavily so that we had to walk the horses,and our places of encampment were regulated by the springs and their distances apart.Wednesday we went twenty-five miles and camped on the Sevier river.Thursday we went twenty-five miles and passed through Panguitch,a small town where John D.Lee of the Mountain Meadow massacre fame,was captured.Friday night we camped on a hill near the Sevier river and a mountain spring.The view at sunset was most beautiful,as we were in sight of the Pink cliffs,which are of pale-red sand-stone,and at sunrise and sunset they contrast finely with the tall blue mountains which form the backbone in the distance.We next crossed the divide between the basin of the Colorado and the Salt Lake valley,and that night camped at Upper Kanab,a town of a few houses.17 Sunday we had a hard day’s march,passing over sandy roads and going twenty-three miles without water.Before attempting this distance we filled a ten-gallon keg and all our canteens and got along without suffering.As a

17 Upper Kanab,located along Kanab Creek near present-day Alton in the northwest part of Kane County,was first settled by Lorenzo Wesley and Susanna Wallace Roundy in 1865.Roundy was a member of the original 1847 Mormon pioneer group.See Martha Sonntag Bradley, A History of Kane County (Salt Lake City:Utah State Historical Society and Kane County Commission,1999),65.

214

UTAHHISTORICALQUARTERLY

Officers at Fort Cameron.

UTAHSTATEHISTORICALSOCIETY

way of relieving the travel through the sand,a line was stretched from the foremost mule to the one in the rear and fastened to the horn of each saddle.It is thought this is an easier way to get the mules through the sand as they help each other in bad places.We arrive at water at 7 o’clock,having made thirty-three miles that day.Kanab is to be our headquarters and here we commence reading the barometer.We shall stay here until our wagon goes back to Beaver and returns with additional supplies.

PREPARING TO MOVE

KANAB,Kane County,Aug.16.Every body is very busy just now shoeing mules,jerking beef,overhauling tents,saddles,blankets,etc.A good many of our things were used last year by Col.Bodfish and hence need repairs and looking over.I take care of the barometers.There are three of us who are detailed for this work.Each is on duty for six hours a day.We received instructions in this duty at Beaver.The work is to read and record the tenths,hundredths,and thousandths by means of an upper and lower Vernier scale.We also read the thermometer and have charge of an instrument for noting the force and direction of the winds.We also observe and record the percentage of clouds in the sky and their species.This work I did for six hours a day before yesterday,twelve hours yesterday and will have six to-day.18

A FRONTIER DANDY

KANAB,Aug.18.If you were to rub your ring and command your general to describe Kanab and that member of the United States geological survey in whom you are interested,they would say:Kanab is the most southern town in Utah,situated about two and a half miles from the line of northern Arizona,and near the Colorado river.It has about two hundred inhabitants and is at the foot of high rocky,sandstone cliffs which seem to throw their great arms around it on the east,north and west,as if to protect it from the hot dry winds which sweep over the surrounding desert.Toward the north there is a break in the cliffs through which flows a small mountain stream supplying the town with water.This water is not so good as that from the wells and contains impurities from the soft sandstone.To the south,and blue from their distance,rise the lofty mountains of northern Arizona,with Mount Trumbull lying cloudlike and indistinct on the far horizon.The days are very warm at this season,the thermometer rising to 95 degrees in the shade by noon,but this is what brings the perfection of pink to the peach, the green to the melon,the purple to the plum and the grape,and that deliciousness of taste which accompanies all fruit when in the perfection of ripeness.This is indeed a great fruit country,and there is a delicacy and rich-

18 The cloud cover would not have been of interest to the USGS.No doubt they took data for the Signal Corps weather service.

215 LEONARDHERBERTSWETT

ness in the taste which I have never found anywhere else.

The twilight and early evening is the pleasantest time of the day,and,as that member of the survey in whom you are interested sits with an old Mormon,the owner of a grist mill,at the door of his home,talking over early times in Utah,over a bunch of the juiciest grapes,watching Venus sinking into the west,and,later,Jupiter rising over the cliffs to the eastward, and listening now and then,I am afraid to the music of a little Venus inside of the name of Harriet,I think I hear the old man exclaim,and I indorse the sentiment,“This is the loveliest climate in the world.”Then after a little pause the boy says good-night and wanders off into the starlight toward our camp.

I fear you would not know that boy,so rapidly he is changing to a frontier dandy.He has a nose pealed with the heat,lips cracked,hands brown,and lumps of hair standing at irregular intervals all over his face.He wears high boots with high Mexican spurs,pants with a buckskin seat, buckskin trimming at the bottoms,over the knee and around the pockets, with a stray star of buckskin here and there for ornament;a blue shirt,gray duck jacket with plaits in front and trimmed with black braid;and to complete the suit a broad brimmed,white felt hat with buckskin strings to tie under the chin or behind,when the wind blows.This is at present his photograph,and as he is tired now he refuses to be interviewed any further, and vanishes into the air,leaving you to call up his figure thus described, from the mystic forms of the desert.

As I pass to my home I go near an Indian camp where they have a sick old man,and they fire guns all night and make strange wild noises to frighten the devil off.

LEONARD H.SWETT

216 UTAHHISTORICALQUARTERLY

Main Street in Beaver.

UTAHSTATEHISTORICALSOCIETY

With this description of Swett’s appearance and clothing and the nearby Indian camp,the Chicago Times account ends.Leonard Swett’s father circulated the Chicago Times article widely and proudly.However one reader, Clarence King,Director of the United States Geological Survey under whose administration the work in southern Utah and northern Arizona was being carried out,was not pleased and in a direct and sarcastic letter to Sumner Bodfish dated September 10,1879,ordered that such publications cease.

My Dear Mr.Bodfish:-

Certain letters addressed to his fond mother by Mr.Leonard Swett of your party are finding their way,in good [purview?],in the Chicago newspapers,to the eyes of the world.

I will trouble you to say to all members of your party that they are directed to abstain from such publications of whatever kind relating to the Survey, its operations,and the country which it covers.

Should any member of your party have his life or health endangered by overflowings of literary matter,he should relieve himself by venting his lucubrations on me in future [purview?] Our collections of kindling wood in the central office will be enriched.

I hope that you are having a good time and that the Grand Canyon will not swallow you.Trusting that you are having a good time and that I shall hear from you in December.

I am

Very truly and unofficially yours, Clarence King Director 19

Swett’s parents were also asked not to publish any more of their sons letters.The senior Swett reported to his son in a letter dated October 4,1879, “I received a dispatch dated the 26th of September asking we not to publish anymore of your letters,and I telegraphed in reply that I would not.We are curious to know what this means.Time of course will reveal.As I have previously stated,if you have been censured for this publication,it is fair that you lay the blame on me.”20

Just why Clarence King objected to such published reports of the work being done under his direction is not known.Perhaps King perceived potential political problems from such reports.It may be that he wanted to maintain control of publicity regarding the agency’s work,or perhaps he feared that the publication of individual reports might foster discontentment and contention within the surveys.It is also possible that King wanted to avoid a flood of applicants who might be seeking work with the Survey to

19 Clarence King Papers.C1,Letter Press Book,USGS,1879-1882,James Duncan Hague Collection, Huntington Library.The cover of the book is marked “Private USGS.”The contents did not become part of official records that were microfilmed.

20 Swett Family Correspondence,Huntington Library.

217 LEONARDHERBERTSWETT

further their literary careers and ambitions. The exact source of friction between Swett and Bodfish is not entirely clear.However, King’s admonition did not help.It is likely that Swett,a privileged young man who hobnobbed with Bodfish’s superiors,might have created an awkward situation for the former colonel who was used to discipline and subordinates who followed the chain of command.Whatever the reason or reasons,the hard line taken by Clarence King and the pain of reprimand that both Bodfish and the younger Swett felt were the likely cause of a rift between the two men that led to Swett seriously considering leaving the survey and returning home.21 In three letters written to his son on October 4,6,and 10,1879,the elder Swett offered the following advice and support.

The letter which you sent personally to me has been received and all your instructions will be carefully followed.I will write you personally upon this question…

Enclosed in this letter please find the five one dollar bills which you wrote for.I assume that you will not need the twenty dollar draft immediately but I will send it in a little while.If you need anything you had better send in a message as you did before,always remembering with your requests to state how your health is.

I think you have done splendidly in sticking to this wild life.Although you may have annoyances,it is exactly the thing you need and will do you good all the balance of your life.This with the trip to Europe which I am still determined you shall take,will round your education and experience and qualify you well to put on with earnestness and success as I believe,the harness of life.If you once get your health and have a strong physique,there is no profession which you need fear and none in which you cannot compass full measure of success.

Your letters and your course of conduct on this trip have commended themselves to me and I really think more of you than I ever did before.

This morning we received a letter at the house embarrassing one to Mother and one to me & as I came to the office,I found yours of the 24th asking permission to leave the party and come home.

In reply to this I would state

I remit this question to you,leaving you to decide it as you think proper. If you decide to come home & come that will end the matter.And although

21 Bodfish,however,was

(152/2).

UTAHHISTORICALQUARTERLY 218

UTAHSTATEHISTORICALSOCIETY

Clarence King.

praised by Dutton and Powell—by Dutton in the First Report of the United States Geological Survey,and by Powell,who highly recommended him to the Secretary of the Navy.

I should regret the necessity from which the action rises I shall acquiesce & not complain.Decide the whole question as your judgment dictates for your own good is the question involved.

In my judgment the following are the considerations which ought to control.If your health is in danger you ought to come,but if this is a question of [feeling ?],Mr.Bodfish,as you say making it disagreeable to you,that will not hurt you and if I was in your place I should stay.I would say also stay as long as you can.Even if you do not stay through.By the time this will reach you,you will be nearly through.Tough it out if you can & if you cant come.

2.As I understand your Col Bodfish if you should come home,would pay you 83 # and you have $100 at Salt Lake & you will need no more.This is what I understand from your letter & if I am wrong you must advise me.

If you come home I should if I [ ] come to Kanab & then telegraph me. If you need more money I can send it to you there.It will only take about a week.From there you can come to Salt Lake & if necessary I could telegraph you money there.

I enclose herewith a letter to Col.Bodfish in reference to the publication and one in reference to leaving the party.You can present them or not just as you think best.Your other requests for letters of introductions and cards will be attended to but not today,as I wish to get this off without delay.

I enclose in this letter five one dollar bills I also sent five dollars to you Saturday.I believe.I send these small sums because I am not sure the letter will reach you.I shall probably send other small sums in future letters. Remember my friendship & [ ] does not depend upon staying or coming.I shall try to be with you in love and sympathy always.Do whatever you think best & you will find me always sustaining you.

Yours Truly Leonard Swett22

Leonard Swett did stay with the survey until the fall of 1879.The following year he returned with the United States Geological Survey to Kanab where he resumed his work under the supervision of Sumner Bodfish.23

22 Swett family correspondence,Huntington Library.In Swett’s letter to his son on October 10,1879,he admonished him “…not to desert the party.If you leave at all it should be by amicable arrangement.You must see some safe way in which you can get to Kanab.The desert you know is implacable and starves & kills [off?] all who venture rashly upon it…..No one knows of your letter asking to come home Except Mother,Col.Quigg and Mr.Haskell.WE all think the question should be one of necessity.If your health breaks down or is impared that is a good reason,but feeling don’t account for much and as that will pass away with the cause I think you should know that for a month rather than leave.Mr.Haskell will right you today.All the party will get homesick.All will soon begin to count the days,and if you can bear it you will all be glad.”

23 The 1880 letters will be published in the Fall 2007 issue of the Utah Historical Quarterly

219

LEONARDHERBERTSWETT

“Places that Can Be Easily Defended”: A Case Study in the Economics of Abandonment During Utah’s Black Hawk War

ByW.PAUL REEVE

It was December 1862,when Mormon colonizer James Jepson arrived at Virgin City,Utah,a small agricultural community crouched at the bottom of a shallow pocket along the banks of the Virgin River. Jepson had received his call to the Cotton Mission just three months earlier;he shortly sold his home at Salt Lake City and began the tedious journey south.1 For Jepson,this was only the latest in a string of dislocations he and his family had endured since converting to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints or Mormonism decades earlier.In 1842,he and his wife left their native England to join the main body of saints at Nauvoo,Illinois,and then relocated three more times before settling for seven years at Mill Creek in Salt Lake County.It was the longest Jepson had stayed in one place since becoming a Latter-day Saint and in the words of his son,“the future looked bright with promise”—that is until the call came from Mormon leader Brigham Young to move south.

For Jepson’s family the first winter in Utah’s Dixie proved challenging as they began the rigorous task of building a new life in the harsh desert environment of southwestern Utah.Initially they lived in a tent and wagon, but,come spring,Jepson commenced work on a new,more permanent dwelling.He hauled logs from Kolob Mountain,had them “sawed on shares,”and then fastened them to smoothed cedar poles with wooden pegs which his family whittled “at odd times.”Jepson topped the new abode with a lumber roof,which his son,James Jr.,remembered let the rain “sift through the knot holes and cracks during storms.”2 Nevertheless,it was home and served the Jepson family well.

A few years later,in 1866,word arrived at Virgin City from Brigham Young that would yet again disrupt Jepson’s life.Young’s instructions stipu-

of Utah.

1 Brigham Young formed the Cotton Mission in 1861 as part of his overall effort to achieve economic self-sufficiency.That year he sent more than three hundred families beyond the southern rim of the Great Basin to settle what became known as Utah’s Dixie,and charged them with growing cotton and other warm climate crops.St.George became the capital of the mission from which local Mormon leaders directed the founding of additional towns throughout the region.See Andrew Karl Larson, “I Was Called to Dixie”;The Virgin River Basin:Unique Experiences in Mormon Pioneering (Salt Lake City:Deseret News Press, 1961) and Douglas D.Alder and Karl F.Brooks, A History of Washington County:From Isolation to Destination (Salt Lake City:Utah State Historical Society and Washington County Commission,1996) for broader studies of the region.

2 Etta Holdaway Spendlove,“Memories and Experiences of James Jepson,Jr.,”12,typescript,Utah State Historical Society Library,Salt Lake City.

220

W.Paul Reeve is an assistant professor of history at the University

lated that due to “Indian trouble small settlements should be abandoned, and the people who have formed them should,without loss of time,repair to places that can be easily defended.”3 According to James Jepson Jr.,Virgin residents “were ordered to move into forts at Rockville and Toquerville.”In response the elder Jepson disassembled his lumber home and hauled the entire structure about ten miles upriver to Rockville.This time Jepson was able to secure nails,saving his family the task of whittling new wooden pegs.However,the day Jepson finished rebuilding the house two riders charged into Rockville at full speed,spreading the news that there would be a fort erected at Virgin City after all.As a result,James Jr.recalled,“father and I tore the house down again and hauled it back to Virgin,where we rebuilt it and lived in it for two years.”4

Clearly for Jepson this “Indian trouble”interrupted an already difficult community building effort.Similar dislocation stories repeated themselves throughout central and southern Utah among Mormons and Native Americans alike.The Black Hawk War (1865-1872),as the “Indian trouble” came to be called,proved the worst Indian uprising in Utah history. According to John Alton Peterson,the war’s foremost historian,at least

3 Brigham Young,Salt Lake City,to Erastus Snow and the bishops and saints of Washington and Kane counties,May 2,1866,in James G.Bleak,“Annals of the Southern Utah Mission,”vols.A and B,A:226-29, typescript,accn.#194,special collections,manuscripts division,University of Utah Marriot Library,Salt Lake City.

4 Spendlove,“Memories and Experiences of James Jepson,Jr.,”10-11.

5 John Alton Peterson, Utah’s Black Hawk War (Salt Lake City:University of Utah Press,1998),2,32935.The Black Hawk War officially began on April 9,1865,at the central Utah town of Manti where a confrontation between Mormons and Utes produced a spark that ignited complex and long standing tensions.See Peterson chapters one,two,and three for a thorough analysis of the forces that led to the outbreak of war in 1865.

6 Peterson, Utah’s Black Hawk War, 329-35.

221

seventy whites were killed and perhaps twice as many Native Americans. Young’s abandonment policy led to the closure of dozens of major settlements and hundreds of ranches,as Mormons built forts and banded together for safety.5

For the Mormons,dislocations prompted by the Black Hawk War were only the last in a string of ousters which Peterson contends took their place in the Latter-day Saint psyche next to the saints’earlier banishments from Ohio,Missouri,and Illinois.There was an ironic difference in the Black Hawk War relocations however.Desperate,dispossessed,and starving Native Americans,by raiding and plundering Mormon communities,set Mormons in southern and central Utah in motion,but it was the two decades of dislocations suffered at the hands of ever-encroaching Mormon settlers that fueled the Native American hostilities in the first place.6

Even though Young’s abandonment policy no doubt saved lives,Peterson contends that at times it conversely produced “serious frictions”among members of disparate communities forced to merge under already tense circumstances.At some places town consolidations quickly created overcrowding as refugees occupied any available cover,including dugouts, chicken coops,and sheds.Elsewhere residents expressed resentment over their town being selected for abandonment and suggested priesthood favoritism in the process.Others bemoaned the economic impact that leaving their homes and land created:Robert W.Glenn,for example,upon being ordered to leave Glenwood in 1866 lamented losses of about $1,700. Farther south,Levi Savage especially resented his lost rights to grazing lands near Kanab,because,he contended,“local churchmen”took advantage of abandonment and jumped his claims.7

Young’s mandated frontier population shifts no doubt burdened already struggling Mormon towns,the economic impact of which begs further study.Clover Valley and Shoal Creek,two Cotton Mission settlements forced to merge as a result of the Black Hawk War,offer a notable opportunity to do just that.Under orders from Mormon apostle and Cotton Mission president,Erastus Snow,Clover Valley saints abandoned their community in 1866 and moved more than thirty miles east to combine with a small kinship group already occupying Shoal Creek Fort,an outpost resting on the southern end of the Escalante Desert in Washington County. By 1868 Snow deemed it safe to abandon the fort.Most residents responded by founding Hebron,a new town just outside the walls of the former fort. Some settlers,however,rejected Snow’s admonition and quickly returned to reoccupy land at Clover Valley.

It is evident that the forced mixing of Clover Valley and Shoal Creek caused social tension and power conflicts that persisted long after the Black Hawk War,but what of the economic impact on residents of both towns?8

7 Ibid.

8 Many of the assumptions concerning social strife made in this paper are based upon W.Paul Reeve’s,

222

UTAHHISTORICALQUARTERLY

Clover Valley denizens abandoned their crops and homes,placing themselves at the mercy of Shoal Creek residents.But,those at Shoal Creek also sacrificed as they voluntarily redistributed land to make room for the Clover Valley refugees.Were the social tensions manifest at the fort merely surface manifestations of underlying economic anxieties as these two communities struggled to unite? Were Clover Valley movers relegated to the monetary margins while Shoal Creek residents maintained advantages critical to determining their positions of wealth?

Tax assessment records for the ten years surrounding life at the fort (1865-1875) highlight the economic impact this coming together had upon total wealth,land,livestock ownership,and social stratification. Young’s abandonment policy also raises intriguing questions concerning key economic principles.For example,economists J.R.Kearl,Clayne L. Pope,and Larry T.Wimmer,contend,after studying household wealth in Utah from 1850 to1870,that “time of entry into the economy was critical in the determination of a typical household’s wealth position.”This is true they argue,for two reasons.First,land of the highest quality is brought into production first,leaving only marginal land available to alleviate pressure from population growth and capital accumulation.Second,those who participate in an economy for a longer period of time generally amass “a larger stock of useful and valuable economic information”about prices and skills relating to a particular region.They conclude for nineteenth-century Utah, “time of entry or duration in an economy to be a significant determinant of wealth”and that “the distribution of wealth becomes increasingly unequal through time.”9 These findings,when applied at a community level suggest that settlers uprooted by relocation would be at a decided disadvantage due to their late entry into an established economy.

In southwestern Utah,hostility between Mormon settlers,silver miners, and Southern Paiutes predated the Black Hawk War.However,it was the heightened nature of that conflict that eventually led Young to order the abandonment of outlying communities on the Cotton Mission frontier.10 Those orders came in May 1866,when Young instructed Erastus Snow that in order “to save the lives and property of people in your counties ...there must be thorough and energetic measures of protection taken immediately”;he then ordered the abandonment of all “small settlements”deemed “too weak to successfully resist attack.”Young left the selection of towns for relocation in the hands of Snow,but did stipulate that gathering sites

“Cattle,Cotton,and Conflict:The Possession and Dispossession of Hebron,Utah,” Utah Historical Quarterly 67 (Spring 1999):148-75.

9 J.R.Kearl,Clayne L.Pope,and Larry T.Wimmer,“Household Wealth in a Settlement Economy: Utah,1850-1870,” Journal of Economic History 40 (September 1980):447-96.Kearl’s,Pope’s,and Wimmer’s explanations are centered upon key Ricardian economic principles named for British economist David Ricardo (1772-1823).

10 For a more complete discussion of these competing forces and of the Southern Paiutes’role in the Black Hawk War see W.Paul Reeve, Making Space on the Western Frontier:Mormons,Miners,and Southern Paiutes (Urbana and Chicago:University of Illinois Press,2006),69-72.

223

ECONOMICSOFABANDONMENT

should be chosen “that can be easily defended,and that possesses [sic] the necessary advantages to sustain a heavy population.”Young further added that “there should be from 150 to 500 good and efficient men in every settlement;but not less than 150 well armed men....Where there are several settlements which do not have this number of men,there should be places selected at which the requisite number can concentrate.”11

In implementing this advice Snow apparently modified it to suit local circumstances as well as to fit his own vision of colonization in southern Utah.Snow had presided over southern Utah from the Cotton Mission’s beginning in 1861 and would continue to be an influence there until his death in 1888.As Mormon apostle and colonizer he was responsible for the spiritual,economic,and social well being of southwestern Utah Mormons. He involved himself in a variety of economic pursuits,including cattle ranching,the Washington Cotton Factory,and the Southern Utah Cooperative Mercantile Association.In these various capacities he developed an overarching vision for southern Utah,which no doubt,came into play as he began to implement Young’s directive.12

Snow traveled to Shoal Creek in July 1866,and complimented its residents on the “good place”they had selected to build a fort and predicted that in the near future “there will be a flourishing settlement here.”He then significantly reduced Young’s suggested numbers and advised Shoal Creek denizens:“I feel that you need a good Ft.& 40 good men filled with the power of god and well armed ”and proceeded to announce that he would instruct Clover Valley settlers to vacate their homes and settle at Shoal Creek.13

Clover Valley had more residents than Shoal Creek and had a longer established fort,but Snow still selected the latter as a gathering spot.A closer examination of the two communities prior to their merger helps explain Snow’s rationale as well as set the stage for exploring the economic effect the forced blending of towns produced.

John,Charles,and William Pulsipher,along with David Chidester,first settled the Shoal Creek region of Washington County in 1862.Snow sent them off from St.George the year before to find good herd ground to graze the ever-increasing number of livestock being brought to the Cotton Mission.They selected a site more than forty-five miles northwest of St. George along Shoal Creek and soon spread out to tend the large herds under their charge.Before long Chidester abandoned the small ranching

11 Young to Snow and the bishops and saints of Washington and Kane counties,May 2,1866,in Bleak, “Annals of the Southern Utah Mission,”A:226-29.

12 See Andrew Karl Larson, Erastus Snow:The Life of a Missionary and Pioneer for the Early Mormon Church (Salt Lake City:University of Utah Press,1971),especially chapters 22 and 30 and pages 519-21 for evidence of his leadership and economic activities in southern Utah.

13 Hebron Ward General Minutes,1862-1897,3 vols.,1:78-82,emphasis in original,microfilm,Church History Library,Family and Church History Department,The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City (hereafter cited as Hebron Ward General Minutes).

224 UTAHHISTORICALQUARTERLY

outpost,but the Pulsipher brothers,joined by their father Zera and brother-in-law Thomas S.Terry,persisted in what quickly became a family business.14 Occasionally others came to Shoal Creek looking to take advantage of the good herd grounds the Pulsiphers had found and settled at different spots along the creek.In response,the Pulsiphers expanded their ranching operations and moved to occupy more land.By 1865,one report described the settlers’strewn condition,noting that they had built “two or three houses in a place and the locations from 2 to 7 miles apart.”15

Apparently friendly relations with Native Americans allowed such a dispersal.John Pulsipher,for example,recalled first exploring the area and visiting a band of Southern Paiutes living there.He remembered that “they expresst themselv[e]s well Pleased with our coming to live with them”and later commented that “we were blessed wonderful[l]y & we had no trouble with th[e] natives altho we were few,but always ready.”In 1864,Pulsipher did note that the scattered families at Shoal Creek coalesced for a time “for mutual Defense,”against the Indians,but this temporary gathering only lasted for about a month before the ranchers returned to their homes.16

At Clover Valley,in contrast,increasingly hostile relations with Native Americans directly affected the settlers,making fort life the most logical choice.In early 1864 a group of Mormons under the direction of Edward Bunker founded Clover Valley,approximately thirty miles southwest of Shoal Creek in present-day Nevada.According to Orson Welcome Huntsman,who arrived at Clover Valley in 1865,the “valley was only about one mile wide and three or four miles long,running east and west,carpeted with green meadows,watered by nice springs ...and surrounded by low rolling hills,which were covered with wild sage brush and cedar trees and a very good stock range.”17 By 1865,the county surveyor had laid out a “little village”at Clover into twenty-five lots,eight rods by sixteen,and the townspeople had built a “well finished school and meeting house ...of squared logs.”18 Rather than spreading out with their herds like the Shoal Creek group,those at Clover Valley “were mostly all living in a little fort.” Huntsman recalled that the people “had built their log houses close together,forming a hollow square,in order to protect themselves from the indians [sic] as they had been hostile.”19

14 There were consistently four members of the Pulsipher group listed as taxpayers throughout the ten years under study,although not always the same four.Charles Pulsipher spent considerable time away from Shoal Creek on church business,but he returned as a taxpayer in 1873,likely taking over for his father Zera who disappears from the tax rolls that same year.The other three members of the group,John and William Pulsipher and Thomas S.Terry remain constant throughout the time period.See Washington County tax assessment rolls,1865 - 1875,microfilm,Utah State Archives,Salt Lake City (hereafter cited as tax rolls).

15 Bleak,“Annals of the Southern Utah Mission,”A:195.

16 Hebron Ward General Minutes,1:6-7,8,29.

17 Orson Welcome Huntsman,Diary of Orson W.Huntsman,typescript,vol.1:12,L.Tom Perry Special Collections Library,Harold B.Lee Library,Brigham Young University,Provo,Utah.

18 Bleak,“Annals of the Southern Utah Mission,”A:195.

19 Diary of Orson W.Huntsman,1:12-13.

225

ECONOMICSOFABANDONMENT

In early 1864,even before the Black Hawk War began,Mormons at Clover,as well as neighboring Eagle and Meadow valleys (all in present-day southeastern Nevada),fought with their Southern Paiute neighbors.In August 1864,according to Mormon reports,a “large number of Thieving Indians”raided these tiny outposts perched on the Cotton Mission’s western frontier and drove off “considerable stock & tried to kill several of the men.”In the process the Mormons took three Paiute prisoners. Apparently,the prisoners dared an escape attempt,but the Mormon guards killed them in the ensuing confusion.Needless to say,this “greatly enraged” other local Indians and set the frontier settlers on edge.Upon learning of these difficulties Erastus Snow recommended to Edward Bunker,the ecclesiastical head over the frontier settlements,“the policy of taking no prisoners,but of killing thieves when taken in the act.”Snow did “hope,” however,“that God will over rule it for the best.”Beyond that,he admonished the settlers at Panaca and Eagle Valley to “either concentrate and adopt the measure of defense recommended,or abandon the place with your families and stock.”He then added,with uncanny foresight,“what is said of Panaca,will apply with still greater force to Clover Valley.”20

It seems,then,that relations with Native Americans proved a determining factor in the type of spatial arrangements chosen at the two hamlets as well as the primary consideration behind Snow selecting Shoal Creek as the gathering spot.Clover Valley had a longer established fort,three times as many families,and a “well finished”meetinghouse;nevertheless,Snow advised its residents to relocate to “Shoal Creek & other Places where u will be more safe.”21 Snow’s implication is clear:Clover Valley would likely continue to suffer from hostile relations with Native Americans,while Shoal Creek might be spared.

Besides its more favorable Indian relations,Snow seems to have envisioned Shoal Creek as a “flourishing settlement”and perhaps saw more economic potential there.The tax assessor in 1865 collected taxes from seven property owners at Shoal Creek:Hyrum Burgess,Zera,William,and John Pulsipher,E.R.Westover,Moses N.Emmett,and Thomas S.Terry. This group controlled a total of $5,245 in wealth,producing a median of $650.The two largest property owners,William and John Pulsipher,commanded 47 percent of the Shoal Creek total and,when combined with the next two largest holders,Zera Pulsipher and Thomas Terry,this kinship group’s portion rose to 76 percent.22 Clearly the Pulsipher clan dominated

20 Hebron Ward General Minutes,1:29-30;Erastus Snow to John D.L.Pearce,Meltiar Hatch and Samuel F.Lee,in Journal History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (chronology of typed entries and newspaper clippings,1830 to the present),August 27,1864,1-3,Church History Library, Bleak,A:170-71;see also Reeve, Making Space on the Western Frontier, 49-58,69-72 for additional context on Mormon relations with Southern Paiutes before and during the Black Hawk War.

21 Hebron Ward General Minutes,1:82.

22 Tax rolls,1865.

23 Hebron Ward General Minutes,1:61.

226

UTAHHISTORICALQUARTERLY

1.1885 Shoal Creek Total Wealth

the area economically,a factor that carried over into persistence at Shoal Creek.John Pulsipher,for example,lamented in September 1865,the rapid turnover of settlers,writing that “of all that have lived here there has been but few that we could depend upon regular to keep up the settlement.”23

Economic considerations likely played a role in the fluid nature of the settlement at Shoal Creek and illustrate a key economic principle.As Shoal Creek founders,the Pulsipher clan enjoyed an advantage over later arrivals. They claimed the best land early and gained a working knowledge of the region so that when newcomers attempted to encroach upon their herd grounds they simply spread out to occupy additional lands.24 Of the seven taxpayers listed in 1865,only four,the Pulsipher group,remained by 1868 to move into the fort,the rest sought refuge elsewhere.

The least wealthy,Hyrum Burgess,for example,reported owning no land or improvements,two cows,three horses,one vehicle,and $25 worth of additional property for an impoverished total of $265.Burgess it seems, possessed somewhat of a wandering spirit,a character trait that may help to account for his lack of wealth.He was a grandson of Zera Pulsipher and a nephew of John Pulsipher.He came to Utah in 1850 at the age of thirteen. Four years later he was in southern Utah as part of the Southern Indian Mission.By 1861 he was married and had a son who was born in Summit County,Utah.Three years later he was back in southern Utah living at Shoal Creek where he stayed for one year.In 1865,he moved to Nevada because,as John Pulsipher put it,“he thinks there is more money somewhere else—(at the mines West).”25

The vast majority of the 1865 holdings at Shoal Creek,76 percent, existed in the form of livestock,including cattle,horses,sheep and goats (see Figure 1).Interestingly,land and improvements only comprised 8 percent of the total wealth;however,within a decade,this category’s importance rose as population pressure escalated and available lands grew increasingly marginal,a factor that would once again give the Pulsipher bunch an important edge.In short,Shoal Creek denizens controlled very little wealth,and most of that which they did have was portable.

As for Clover Valley,the 1865 assessor levied taxes on sixteen men,who shared a total wealth of only $5,968,just $700 more than the much smaller group at Shoal Creek.Clearly those at Clover Valley were poor,with a

24 For a detailed description of the Pulsipher clan’s response to newcomers see Reeve,“Cattle Cotton, and Conflict,”156-58.

25 Hebron Ward General Minutes,1:22,25,62,emphasis in original;Tax rolls,1865.

227

ECONOMICSOFABANDONMENT

Figure

Source:Washington County Tax Rules, 1865.

median wealth of $255, almost a third of the Shoal Creek median.Dudley Leavitt topped the Clover Valley list,reporting a total wealth of $1,260,most of which ($955) existed in the form of 52 head of cattle.Jonathan Hunt,the poorest at Clover Valley,reported owning two cows,one horse,and six sheep or goats,worth only $83.There was no kinship domination of wealth at Clover Valley;the top third of the property owners controlled 62 percent of the wealth,the middle third 23 percent, and the bottom third,15 percent.Only one person at Clover Valley,Samuel Knights,claimed any land or improvements,the rest apparently did not view their cabins at the fort as personal property.Like Shoal Creek,Clover Valley was clearly a pastoral community with cattle,horses,sheep and goats representing 82 percent of the townspeople’s total wealth (see Figure 2).26

By the end of 1866,ten families from Clover Valley—Amos,James,and Jonathan Hunt;James,Joseph and Hyrum Huntsman;Dudley and Jeremiah Leavitt;Zadock Parker,and Benjamin Brown Crow—moved to combine with the Shoal Creek group while the remaining Clover families relocated to Panaca and “other places,”leaving Clover Valley entirely abandoned at least temporarily.27 Even under the best of circumstances,a merger of towns would be trying for people of both groups.Clover Valley settlers essentially became refugees,dependent upon the mercies of those at Shoal Creek.Shoal Creek inhabitants,too,faced challenges as they attempted to fit these new families into previously established geographic,social,and economic orders.

Clover Valley settlers were accustomed to life in a fort and likely had little difficulty adjusting to physical conditions at Shoal Creek.Orson Huntsman remembered the new accommodations this way:“we all built in a fort with houses joined together with most of the doors and windows facing the inside of the square or fort,some houses built of logs,some of rock and some of adobie [sic],and all of the houses were covered with dirt.”He also described the locale as “a very dry desolate looking place” and complained that “when it rained ...our houses would leak mud for a day or two after the rain was all over.”28

Issues of land ownership quickly surfaced at the fort,especially for Clover refugees.According to Huntsman,at the time of the merger there were only “two or three acres of land farmed on the creek all told and a very small piece of land that hay was harvested off of.”He also despaired that for more than the five families already located at Shoal Creek “it was a

26 Tax rolls,1865.

27 Diary of Orson W.Huntsman,1:14-15;Hebron Ward General Minutes,1:88.

28 Diary of Orson W.Huntsman,1:15-16.

228 UTAHHISTORICALQUARTERLY

Figure 2.1865 Clover Valley Total Wealth

Source:Washington County Tax Rolls, 1865.

very discouraging outlook.”In Huntsman’s eyes “there was nothing for them [the Clover Valley brethren] to subsist on,only in raising stock,this was a good place for that but there was no market for stock,butter or cheese.” 29 Understandably,then,the dismal economic outlook for the Clover Valley group became a point of concern.

Not long after moving together,the “Shoal Creek brethren”and the “Clover brethren,”as they called themselves,met to address the issue of land distribution.Zera Pulsipher chaired the meeting while the Clover brethren selected father James Huntsman as their spokesman.Huntsman began by expressing “some fear that there was not land enough”for everyone,especially because the Shoal Creek brethren “claimed the best.” Without hesitating,the Shoal Creek settlers responded with ingrained egalitarian principles:they “offered,not only their claims,but their enclosed & cultivated lands—all to be used for the public good.”Those gathered then selected father Huntsman,Thomas S.Terry,and John Pulsipher as a committee to divide the land and before adjourning also decided to drop the “Clover brethren”and “Shoal Creek brethren”labels.As John Pulsipher put it,“we are all citizens of this place.So let us be united.”30

By May 1867,the committee had laid out one public field for gardens, one as a pasture or hay field,and a third for unspecified use.Of the garden spot,each family received about half an acre,the hay field,one acre and the last field,two or three acres depending upon the size of the family.As was customary among Mormons,the settlers drew for land by ballot and “the people were very well satisfied.”31

And well they should have been,especially former Clover Valley denizens,as it seems that their move to the fort proved economically advantageous.In 1868,median wealth at the fort equaled $427,a vast improvement for former Clover residents,but a loss for Shoal Creek persisters.In fact,the nine traceable Clover Valley taxpayers living at Shoal Creek Fort in 1868 enjoyed a combined 28 percent increase in total wealth over their 1865 total.32 A significant portion of that increase came in the form of land and improvements,no doubt due to the Shoal Creek residents’willingness to redistribute land.Interestingly,in doing so the Shoal Creek settlers parceled themselves into minority holders. The Clover Valley movers collectively reported $675 worth of land and improvements,or 55 percent of the total land value at Shoal Creek Fort.Even Jonathan Hunt,the poorest of the Clover Valley movers, managed to improve his standing,doubling the number of his cattle to

29 Ibid.

30

Hebron Ward General Minutes,1:95-96,emphasis in original.

31

Hebron Ward General Minutes,1:110-11.See also,Reeve,“Cattle,Cotton,and Conflict,”161-65.

32 James William Huntsman was part of this traceable group,but did not arrive at Clover Valley until October 1865,after the tax assessor made his stop there.Consequently,for the purposes of the collective comparison of total wealth for those who moved to Shoal Creek,I have used Huntsman’s 1866 Clover Valley assessment with the eight other 1865 assessments.See Tax rolls,1865,1866.

229

ECONOMICSOFABANDONMENT

four,picking up $50 worth of land and nearly tripling his total wealth to $242.33