Table of Contents

Overgrowth

By Anonymous | page 4

Greening the Sea: Growing Seaweed and Resilience in Coastal New England

By Emma Polhemus| page 7

Thoughts and Prayers

By

Loden Croll| page 10

Dare to Grow Your Roots

By

Deniz Dutton| page 11

Sheltering within Storytelling: A Home on the Hill of our Spines

By Kate Wojeck| page 14

The Delusion of Expectations: World of Forests and Fields

ByErin

Camire| page 17

Skimming the Surface: An Introduction to Eutrophication in Lake Champlain

By Jaylyn Davidson| page 19

Fire in the Pines: New England’s Forgotten Fire Story

By Valentin Kostelnik| page 21

Returning to the Land: Buffalo Conservation in Montana

By Meagan Beckage | page 24

Exploring My Place-Based Connections to Northeastern Italy

By

FoscaBechthold | page 27

Shattering: On Ocean Acidification

By Ella Weatherington | page 30

What Once Was

By

Jamie Cull-Host| page 33

Managing Editor

Deniz Dutton

Editors

Aiden Armstrong

Andie Vellenga

Anna Eldridge

Ben Mowery

Cole Barry

Fosca Bechthold

Kate Wojeck

Loden Croll

Megan Sutor

Sarah O’Leary

Masthead

Co-Editors-in-Chief

Jake Hogan

Teresa Helms

Creative Director

Ella Weatherington

Planning and Outreach

Adelyne Hayward

Social Media

Emma Polhemus

Jamie Cull-Host

Managing Designer

Maya Kagan

Artisits and Designers

Alex Zoner

Avery Redfern

Casey Benderoth

Deniz Dutton

Ellie Yatco

Emma Polhemus

Fosca Bechthold

Frances Leadman

Grace Weckesser

Joshua Delahunt

Mia Weyant

Sadie Holmes

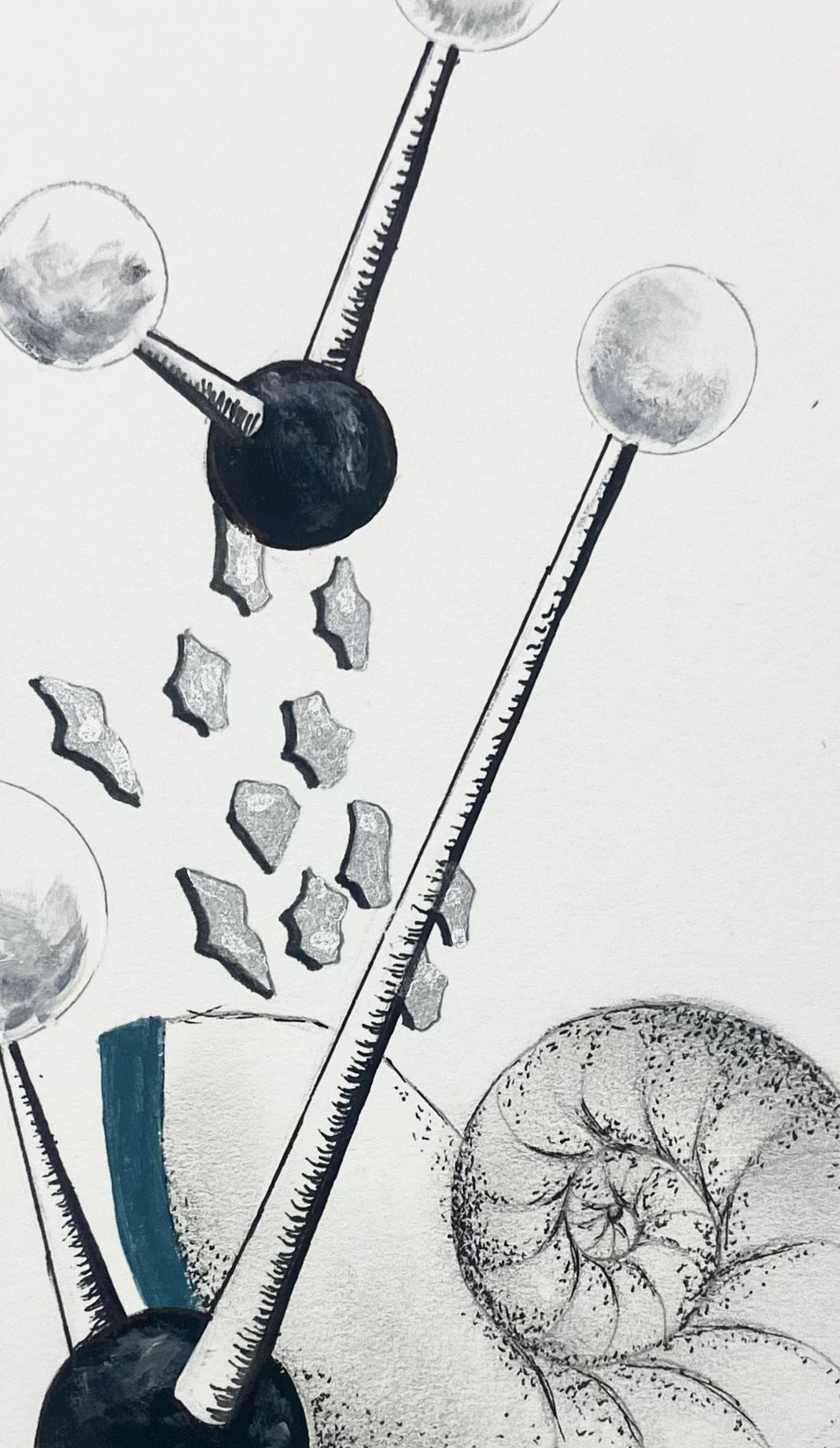

ArtbyMiaWeyant

AFoliageofPlantsThroughoutEvolutionaryTime (Cover)

Maya Kagan

Digital collage

This semester’s Headwaters cover incorporates herbarium specimens from the UVM Pringle Herbarium into a collage highlighting plant diversity over evolutionary time. The back cover includes some of the most ancient lineages of plants, such as Equisetum, Lycopodium, Selaginella, and Isoetes depicted at the bottom, and ferns from a diverse set of genera at the top. The front cover highlights plants from exclusively flowering plant families, which are the most recently evolved lineages of plants. The cover alludes to this semester’s theme of “past present future” by highlighting the diversity of plant life that has existed in the past and continues to flourish today.

Dear Reader,

Welcome to the 14th edition of Headwaters Magazine! As always, we must express our sincere gratitude for the Rubenstein School of Environment and Natural Resources, the Student Government Association, and our advisor, Josh Brown.

This Spring, we have the pleasure of publishing an exceptionally strong set of pieces, from insightful personal reflections, to informative explorations of landscapes, to prospective social critiques. Early in our editorial process, a theme emerged from the nascent ideas that would become the content of this issue: Past, Present, Future.

In the very first edition of Headwaters, Inaugural President Dan Kopin wrote that, “Headwaters are the small sources from which rivers originate. With hopes that our ideas may flow into greater bodies of knowledge, we have chosen to put our pens to paper.” Hundreds of pages later, and in a year that feels quite different from 2016, we are still printing this small source of knowledge for you to learn from and enjoy. It is an honor to continue providing a space where UVM’s environmentalists may contribute their talents—into the river and out to the sea.

May these articles inspire you to reflect on the past; the historic significance and plight of buffalo, the forgotten legacies of fire on the New England landscape, or the hindsight that can only come with time.

As you read stories that are deeply personal and yet relevant to us all, you will see our authors decipher what it means to find a sense of place, in Burlington and in northern Italy. They explore the nuances of identity and the nature of community, daring us to be present in our environment, and with each other. And, they point us toward the future. What might lie ahead? In twenty years, will we be lounging on pristine coastlines that have been restored in part by kelp, or are we each doomed for an ill-fated romance as nature takes its revenge on us?

We implore you to consider what legacies you may leave, and join us in looking to the future with open minds and bold ideas. As for the future of this publication, we are thrilled for new and continued opportunities to showcase student journalism and art, and we feel encouraged when we consider the talented editors and illustrators who will take on the torch of leadership in the coming years. From where we stand, the future of Headwaters looks bright.

Sincerely,

Jake Hogan University of ‘23 Co-Editor-in-Chief

Teresa Helms University of

Co-Editor-in-Chief

‘23 Co-Editor-in-Chief

Teresa Helms University of

Co-Editor-in-Chief

Headwaters Magazine is grateful to the Rubenstein School of Environment and Natural Resources for their financial support and dedication to lifting up student-led work. Their generous contribution has made it possible for us to continue providing a dedicated space where science, art, and environmentalism can intersect—in print.

How do you break up with your boyfriend during the end of the world? I would’ve Googled this if the internet was still up, but the last video I watched was a TikTok of my state senator getting strangled by a gigantic dandelion on his driveway. The federal government was unofficially dissolved two weeks after the giant plants started springing up in the US.

After the internet cut out, I heard Otto, my soon to be ex-boyfriend, humming a blues song on the fire escape as he lit a Marlboro. He’s the only guy I know under fifty that smokes Marlboros.

“If I am to die tonight,” he said, “I want it to be right here, watching my city get devoured.”

“Shut up, Lana del Rey!” I said, joining him and crouching a foot away. He reached out his arm and I ignored it. The street below us was every shade of green and no other color. There were the stems and stocks of unidentifiable plants wiggling and thrashing against what remained of the sidewalk; the trunk of a massive flowering pink tree lay on top of the remains of the brownstone across from us. A woman ran out of my favorite local bookstore down the street, tripped over a giant peony plant, and sank into the infinite green.

Before I could articulate my shock, Otto laughed. A maniacal, fake, dejected laugh, as if he had lived this all before.

Overgrowth

By Anonymous“It was always gonna happen,” he said. “It’s revenge.” ***

I was introduced to Otto through our mutual friend Victoria, arguably the worst way to meet a long term love interest. Our first date was a walk through the Common, where I blankly stared at the massive Christmas tree and he told me about how small-scale city parks like this set bad tones for conversations surrounding future urban planning. This set the tone for our relationship.

I learned he was a “sustainable entrepreneur,” and when I asked him to explain what that meant, he said something about how he sells plans to businesses that help them maintain their growth.

“So you’re a consultant?” I asked. “You can just say that.”

He quickly changed the topic to a meme he saw earlier about an overgrown papaya tree, which neither of us took seriously. I stayed silent for the rest of the night.

I have several theories about why I stayed with Otto beyond this point. The dominant one, posited by Victoria, was the Three Greens Theory: Otto had a lot of money, good weed, and the aura of a pseudo-environmentalist, which I found attractive because it was something I could not bring myself to embody. Nothing else about him was appealing. The sex was mediocre, the conversations consisted of his baseless interior monologuing. It was like dating a voice, an act. An act with a lot of money.

I was considering how to ethically ghost him when Tim and Carol, the straight couple I had been subletting from, announced that they were moving out. The rent was outrageous enough in the study I occupied; apartment hunting at that time was abysmal. The landlord said I could have first dibs on the apartment if I wanted it, but that I would have to act fast. I panicked. I asked Otto if he wanted to move in. He said yes, which was initially relieving, but made me cringe when I thought about it. We had only been seeing each other for two months.

Otto then invaded the apartment, putting up tacky posters with hand drawn herbs and brought in strange white minimalist furniture (“It wasn’t your living room to begin with!” he yelled at me when I questioned why he’d put up a life-size wire sculpture of a zebra in the corner without asking). He potted an aloe vera plant on the fire escape (“We have to start using natural remedies,” he said, even though it was the middle of February in Massachusetts).

It was at the same time that Otto moved in that we started hearing about the plants. At first the cov erage was min imal, confined to three minute bitesized chunks of the evening news. In a pan icked response to predictions from ecologists that the forest ecosystems of the Ameri cas would begin to die out without immediate action, the United Nations had deployed a state-of-the-art fertilizer onto various deforested parts of the Americas.

At first it was working: rubber trees thrived in parts of the Amazon where they were once thought to be per manently depleted. Live oaks in Texas began branching out wildly. My boss at the Beautification Bureau broke open the champagne when we found out the fertilizer had been approved to be used in areas in eastern Massa chusetts. By March, it had been utilized in all the conti nental US states. Otto bragged to me about the future of the earth as if he had some part of it.

I sent him videos of me watering his sad potted aloe vera plant when he was away on business, even though I knew it would not grow. He asked me to be his boyfriend like we were fifth graders. This was the healthiest our re lationship got.

But then things got out of hand. Vines from the Am azon, the first testing grounds for the fertilizer, began growing out of control. We watched farmers cut through the giant mass of green that entwined around each oth er like amorphous tree trunks. They got severed Indi ana Jones-style, but grew back like hydras with multiple heads. Rubber trees grew to the heights of redwoods.

“This is amazing,” said Otto. “It’s like, poetic justice.”

“Justice for who?” I asked.

Otto had the tendency to simply go silent and sulk on the fire escape when challenged. The aloe vera plant had risen only marginally since he first planted it, but neither of us acknowledged it.

By April, Rio de Janeiro went dark, and by May, my boss publicly resigned after using the fertilizer within city limits. Texans began evacuating to nearby states, some going south, seeking asylum in Mexico because the north was overrun with black cherry trees. Protestors filled the streets in some strange marriage of environmentalist rage and right-wing extremism. Fox News hosts worked overtime to link the

I reminded him it was going to strike us soon. I realize now that this was a hypocritical taunt. I still felt like I was going to get out by some miracle, that I would get up and leave and move to some desert compound and help stoke the flames of a new age civilization. That Otto would belong to the past.

But I didn’t leave. Instead, I stayed in Boston, micromanaged Otto’s increasingly toddler-like ramblings on the fate of our planet, and went to work on Zoom because the Beautification Bureau offices had their windows bashed in by protestors with gardening shovels.

Right after Florida, everywhere was affected. Eastern Redbuds rose an inch an hour; the Common began to look like a head of unkempt hair. Park rangers were called into the city to battle against the bushes. Then, for some reason, Otto went completely silent. No more proclamations of justice. He sat criss-cross on the fire escape looking down at the chaos on the street, cars honking on their ways to Western Mass. Everyone I knew had either evacuated or died absurdly. Victoria was killed after a nightshade berry the size of a boulder had dropped on top of her. There was no funeral.

I doom scrolled. I watched videos of convenience stores being turned into greenhouses, of a giant venus fly trap breaking a man’s arm. I was disgusted—it felt pornographic, but in an especially strange and shameful way. I filled the sinks at half full and began to ration out our food. We could last three weeks with what we had. I assumed something would happen between that time, that someone would come save us. ***

I had been trapped in the apartment with Otto for two weeks when he suggested we kill ourselves. It came after I suggested we try going to the other floors to see if anyone else had supplies. For the past two weeks he had been camping out on the fire escape, and I would leave him canned food on the windowsill like I was feeding a stray cat.

He immediately dismissed my suggestion and lamented that all of Boston was overrun, that we were the last ones left, that even if we did find supplies, it was only a matter of time be fore we were trapped, tripped, or otherwise comically murdered by a vengeful daffo dil. Then he pulled a steak knife out of his pocket.

“Hell no,” I said, backing away towards the window. We were chest to chest. My only chance was to drag him back inside.

I pleaded; I asked for a moment back

inside, for a chance to get out in the world and die trying to survive if we had to.

“No,” he said, “it’s more intimate this way.”

That’s what sent me over the edge. I knew that I was probably going to die at some point for some ridiculous reason, like getting squashed by a giant eggplant or suffocating in a rosebud the size of an SUV. But I still had hope I would be saved, that God, in the midst of this practical joke, would spare enough grace to let me live long enough to find the only other gay man left in the Boston area so that Otto wouldn’t be my last fling.

So I pushed him. He nicked my collarbone with the tip of the knife, leaving a scar. I watched him fall and get swallowed in the middle of the street by a yellow carnation, followed by a thump. There was no screaming. I did not cry. I reached over and picked up the matchbox, lit one and dropped it where he had fallen, like a parting gift. The carnation was consumed by the flames, and come nightfall, the whole street was burning and the apartment was slowly filling with smoke. I loaded a backpack with face cloths and a map of the Seaport. Before I left, I watered the aloe vera one last time, which drooped, flaccid and deteriorating. H

Greening the Sea: Growing Seaweed and Resilience in Coastal New England

By Emma PolhemusThinking back to Pemaquid Beach in the little midcoast Maine town I spent my summer in, I can smell the salty air and the low tide scent of the seaweed crunching under my feet, equal parts fishy and nostalgic. Lobster buoys bob along with the waves, and the occasional washed-up trap breaks the stretches of sandy shoreline. If you followed the river that feeds into the sea a few miles from here, you would find shellfish farms up and down the banks. In this town, like many coastal towns in the area, there are small reminders almost everywhere you look that these communities are built on harvesting from the sea. Fishing, lobstering, shellfishing—these are the economic and cultural backbone of this region, and have been for generations. Even before that, the Wabanaki people—the original inhabitants of this area—caught seals, flounder, and clams from the same waters, and continue to do so today. However, the fishing and aquaculture industries in the Northeast are being threatened by the far-reaching impacts of climate change. In response, the communities that depend on these resources are finding new ways to adapt to these changes without sacrificing their way of life. One of the most promising solutions might be found in the unassuming seaweed I’ve spent years stepping over without a second thought.

Atlantic Sea Farms is a seaweed aquaculture company based in Biddeford, Maine, leading the way amongst this shifting tide. The company was founded in 2009 as the first commercially viable seaweed farm in the United States, and over the past 14 years they’ve transitioned toward supporting the growth of the kelp aquaculture industry throughout the state of Maine. Working with a network of partner farmers, Atlantic Sea Farms grows and distributes kelp seedlings, assists new farmers with the complex permitting process, and processes and delivers the harvested product. In an interview with cultivation specialist Carlin Schildge, she shared with me that the organization’s mission is to address two central

challenges. The first is to increase the proportion of U.S. grown seaweed, since the majority of seaweed products are currently imported from other countries. The second is a little more complex.

Because the state’s culture and economy is closely tied to its fisheries, especially the lobstering industry, ocean warming presents a major threat. Atlantic Sea Farms hopes that by growing Maine’s kelp farming industry, they can help fisheries diversify their income and address the multifaceted challenges of developing climate change resilience in coastal communities.

“Here in Maine, we hear all the time that the Gulf of Maine is warming faster than almost anywhere else on the planet,” Schildge explained, sharing a study from the Gulf of Maine Research Institute (GMRI) showing that the Gulf is warming faster than 97% of the world’s oceans. “So we’re uniquely and intensely affected by climate change.”

A warming Gulf means changing geographical and seasonal patterns for many marine species. Lobster is particularly sensitive to temperature changes, and another GMRI study has found that populations along the southern New England coast have been shifting north for years, chasing cooler waters. As the Maine Department of Marine Resources reports, lobster accounts for more than 80% of the monetary value the state’s fishermen produce in a year, so population shifts and scarcity due to continued warming are a serious concern.

The related process of ocean acidification is adding more threats to shellfishing, another significant portion of Maine’s fisheries. As more carbon dioxide from the burning of fossil fuels is absorbed into the ocean, it undergoes a number of chemical reactions that makes the water more acidic and reduces the amount of available carbonate, a crucial resource for many marine organisms. Oysters, clams, and mussels use calcium carbonate to build their shells, and ocean acidification has been

shown to slow this shell growth and potentially even dissolve them faster than they can be built.

Despite adaptation advances in fishing and aquaculture methods, many fishermen and ocean farmers’ livelihoods are still under threat from these changes in the waters, pushing some to diversify into kelp. Diversification is the key in this—all of Atlantic Sea Farms’ partner farmers continue to engage in multiple types of fisheries, and Schildge was quick to point out that their goal is to integrate seaweed cultivation, not to replace other operations. For lobstermen, whose main harvest season is in the summer, the kelp planting and harvest seasons in late fall and spring are perfectly offset to provide additional work and income. Others who cultivate mussels or oysters are able to grow kelp directly alongside these products. Atlantic Sea Farms is part of a growing community of companies, researchers, and farmers who believe that applying the expertise of these fishermen and aquaculturists to seaweed cultivation could support the long-term survival of what Schildge calls “working waterfronts” in the face of complex climate challenges, and even improve coastal health in the process.

Jaclyn Robidoux of the Maine Sea Grant’s Extension Team shared a similar hope when we spoke about her work with the seaweed aquaculture industry. As part of the team, she acts as a link between researchers, farmers, and processors, so she’s familiar with all sides of the seaweed industry. From her perspective, seaweed farming is a promising industry due to its potential to address multiple challenges and stakeholder priorities all at once, including climate change, local food production, and supporting coastal workers.

“It’s such an exciting time to work in seaweed right now because it’s at the intersection of all these big things…so it’s linking all of these social, economic, and environmental things together and really emulating that triple bottom line sustainability,” she explained.

Seaweed farms in New England most often focus on popular edible varieties including sugar kelp, dulse, and nori. The sugar kelp grown at Atlantic Sea Farms begins life as tiny leaves called sporophytes, which cultivation

specialists grow along strands of twine in a carefully monitored nursery. In the fall, these strands of twine are ready to be planted in the ocean. Once they’re attached to sturdier lines, the seedlings require no additional inputs from the farmers, harvesting all of the energy and nutrients they need from the sun and sea around them. Since the kelp grows vertically through the water column, it’s also highly space efficient, and many seaweed farmers take advantage of co-cropping opportunities as well, growing shellfish alongside the strands of kelp. When harvest season arrives in the spring, what started out as tiny leaves on twine has become blades of kelp up to ten feet long, ready to be gathered and processed into nutrient dense food products.

As the kelp grows, absorbing more and more carbon to build its leafy blades, it changes the chemical balance of the water around it. While seaweeds aren’t actually weeds—or plants for that matter—they do perform photosynthesis as plants do, taking in sources of inorganic carbon and producing oxygen as a byproduct. In waters with increasing acidification, this removal of carbon shifts the equilibrium back toward non-acidic components, temporarily reversing the process of acidification in the surrounding ocean. This is a welcome change for many marine species, especially those with carbonate-based shells. As excess, acidification-contributing carbon dioxide is turned instead into leafing seaweed, nearby oysters and mussels can once again find the materials they need to grow. For aquaculturists struggling to maintain shellfish farms under acidifying conditions, growing kelp alongside the shellfish not only provides a supplementary income source, it also improves surrounding water quality and supports their shellfish harvest. Schildge told me this is known as the “halo effect,” since shellfish grown in the surrounding waters of kelp are larger, healthier, and even taste better.

But the environmental benefits don’t stop there. Organisms can’t survive on carbon alone; they need other essential nutrients including nitrogen and phosphorus, chemicals infamous in many coastal communities—even Burlington—for their ability to cause eutrophication and toxic algal blooms. Kelp in areas that get an influx of

these nutrients from agricultural runoff and other sources can take up this excess and use it for growth, making for cleaner, safer aquatic ecosystems.

At this point, kelp seems too good to be true. So, I asked if there has been any resistance to kelp farming from producers, given the long-standing traditions of these communities.

“Like with everything, change can be really hard sometimes…aquaculture can feel daunting just because maybe there isn’t the same existing infrastructure in place as there are for fisheries that have existed for centuries,” she replied. Despite these challenges, she told me that their partner farmers have been excited about the new opportunities of seaweed aquaculture, in part due to the support that Atlantic Sea Farms is able to offer throughout the process of starting a farm.

“By breaking down a lot of the barriers to entry of the world of aquaculture, I think it makes it much more appealing and accessible to communities in the Gulf of Maine…that’s kind of the key to diversifying the working waterfront here and ensuring long-term viability.”

Robidoux spoke of similar experi ences. The majority of poten tial producers she works with are excited to learn more about this opportunity to expand their income and harvest seasons. The bigger challenge, she added, has been marketing the seaweed to consumers post-pro duction.

“95% of the seaweed that we’re pro ducing in Maine goes into products that people eat. So, we’ve got to make sure that people want to eat it,” she explained. Convincing new customers to try seaweed can be challenging, though. “People could be a little resistant, you know, like, ‘Is it going to taste like low tide? Is it going to be slimy?’ and the answer is usually no…but it still takes a bit of work to get them there.”

Once you get over the initial hesitation, eating seaweed has many human health benefits. The high nutrient uptake that improves the water quality around seaweed also makes it a highly nutritious food. More than once while exploring the world of seaweed cuisine, I’ve seen kelp described as the new kale. And, packed with vitamin B, iodine, and calcium, it does live up to the superfood aspect of this label.

“I think this is where it helps to be humble with seaweed, too,” Robidoux added. “The rest of the world has been farming seaweed for thousands of years, and we consume seaweed or products of farmed seaweed every day and don’t know it.”

Eating kelp is not a new concept, and seaweeds are a central part of many traditional cuisines, especially those from East Asia and the Pacific Islands. In integrating kelp cultivation into the Northeast, Schildge considers it a perfect addition to current food trends. Whether that’s providing a boost of umami flavor to plant-based diets or a healthy addition to green smoothies, she assured me that kelp is much more versatile than it seems. Atlantic Sea Farms already processes and sells a variety of items made with their partner farmers’ harvest, ranging from fermented kimchi-style salads to ginger-sesame kelp veggie burgers. The majority of their product gets purchased by other companies, restaurants, and college dining halls to be used in a variety of meals or processed as a component in non-food items such as toothpaste, medications, and shampoo. Schildge hopes that with more people eating and using kelp, more fishermen and waterfront workers will be able to diversify their income to include seaweed farming.

As we wrapped up our conversation, Schildge reflected on the progress Atlantic Sea Farms has made in supporting local farmers’ ability to face climate change impacts.

“Even just doing one thing to build our resilience is a good thing. Every small step—or big step—moves us in the right direction.”

I think back to my walks along Pemaquid Beach, stepping over the clumps of seaweed. This time, I take the time to really look. That one there is sugar kelp, brown and ribbon-like. The reddish-purple flecks floating in the surf are dulse. And tangled in the bars of one of those old lobster traps are stringy tendrils of rockweed. To many others, these unassuming ocean weeds appear just as miscellaneous trash strewn over the beach. But as you shift your perspective to notice their ecosystem-regenerating, carbon-consuming potential, they become main characters in the evolving story of working waterfronts, knotted together on the sand—tradition and history combined with what very well is becoming the future. H

Thoughts and Prayers

By Loden CrollIfanythoughtwasaprayer

I would have taken the void— mock black, the deepest NASA red of “Unprecedented Times” corroding the poles —as an omen of waning luck, turning the nosebleed red into the gums of a giant with the posturing globe caught in its jaws, gnashed and jagged continents bobbing in seas of unswallowed pride beneath which living things and all their children’s dreams will eventually be sunk for whatever

Undiscovered, digested, ancient terror lives in the belly of a god.

I grieve for everything these days. The sun crushes a windowed skyscraper, gawking at its own destruction

While the rivers burn and the music stops playing All before 10 am on a Wednesday. There is an ancient me, the one that has outgrown my childhood fears, who knows if my miseries are justified—for they have witnessed the deaths of all my mothers— With their moon-old face recalcitrant before the jaws of the world, Mastodon molars seeking revenge for extinction Yawning to raze establishment and scatter my bones across the Wasted rot—at least there, it is quiet.

Like anyone too troubled to mutter their prayers, I let them collect dust in my notes. Moth-eaten years of blue-burning resentment stare down the end of all-knowing, into the Deeper dark blues of outer space’s maw, With grotesque creations that have yet to materialize, Perched, vigilant, On the rabid tongue of a monster with suns for eyes

still, my bedraggled conscious, my mortified person carries on this Mortal coil marching to the beat of the giant’s war drum pulse Praying to my voided future that this world will afford me some parcel of Peace—

Let the earth lie upon me softly And may grief be good to us all. H

Dare To Grow Your Roots

By Deniz Dutton

I never understood people who live in the same place their entire lives. I always assumed, on some level, that there is something wrong with them; that fear is what prevented them from seeing the world, and now they are just creatures of comfort and habit, happy with domesticity and monotony. There is a species of bird down in Costa Rica, where I spent a semester abroad—the blackcheeked ant tanager, which lives only on a peninsula that hardly makes a dent in the Pacific Ocean. Its entire existence is confined to two protected areas of lowland tropical forest. Peering at this bird through a high-mag monocular, I didn’t find its black and brown plumage very striking, but upon learning of its extreme endemism, the bird made an impression on me. What was it like to be confined to one place? To only be able to seek a mate within a radius of a dozen miles, the most far-flung destination being just across the gulf? They have wings, too, which added to my perplexion. Why not wing off to another forest fragment, hop around Central America, see the sights? You could always come back if you wanted to. Now people, like birds, have the ability to fly. In half a day you can be transported to the other side of the world. As airplane ticket fares have lowered, the ability to visit new parts of the world has expanded to a greater share of the human population. Some people, however, are like the black-cheeked ant tanager: disinterested in expanding their horizons, even when the sky is the limit. What is the allure of a place? Why does it have such a hold on us?

One of my favorite things about being in an airplane is looking down on the quilted surface of the earth, watching places pass by underneath. Mountain ranges will come and go; massive cargo ships will appear as

tiny comets on the surface of the wine-dark ocean, with tails of white foam; you will see an endless patchwork of autumnal-hued farmland contrast with the lapis lazuli swimming pools and networks of gray streets in the developed areas. This was my meditation during annual pilgrimages to see my extended family in Turkey. A child of two cultures, I grew up with a sense of place split right down the middle. Only on an airplane did I feel like I didn’t have to choose.

Step 1: Feel Connected

My grandfather has lived on the same patch of ground for decades. He has poured all of his energy into cultivating a farm on the most unlikely of lands—a rocky, eroding mountainside. Being a farmer is tough work, but my grandfather chose this. He could just live on his military pension, but the land calls him, and there he has found his purpose in life.

I understand him when I sit on the large boulder in the middle of his property and take in the panorama of green, blue and purple mountains cascading down to the Mediterranean Sea directly in front of me, just barely distinguishable against the equally brilliant blue sky. When the wind tickles my face, carrying the sweet scent of mulberries and peaches, it tells of paradise; in these moments I know why my grandfather spent the better part of his life building this house and painstakingly creating his own garden of eden. This place holds on to you.

In my grandfather’s garden, I feel connected to the earth that he cultivated, which he did for himself, but also for me and his other grandchildren, so that we may enjoy a rich heritage all our own.

If I can connect with the earth somewhere, I can feel like I belong to it. Walking through the Intervale—a strip of floodplain forest and community farms along the Winooski River—in mid-autumn, I stumble upon a treasure trove in an old, familiar field: misshapen beets left behind, and shaggy mane mushrooms. I gather some, but not all, of these goods and bring them to my car. Later that evening, I boil the beets and make a rich borscht with carrots, potatoes, and cashew cream. The mushrooms get cleaned and sauteed with a bit of butter—perfect. I have received the land’s gifts, land that I myself have tended to

with my own hands, planting rows and rows of lettuce in midsummer, creating irrigation channels; and now, the land has sustained me—as a home should.

Step 2: Be Vulnerable

Sitting at my dining room table at night—the fairy lights that frame the window washing the space in a warm yellow glow and glinting off of the glass jars containing delicate plant cuttings, the clock ticking softly and melodiously—I think this place feels perpetually like the night before Christmas. Sitting here, waiting for my water to boil, I feel just as at home as I felt in my childhood house, a house I can never go back to, now that my parents have left it. I had tentatively hoped that Burlington would be up to the challenge of adopting me this year, and to my surprise, it has.

When the water boils, I take it up to my roommate M’s room, where she keeps her favorite tea. I know she’s been crying and this is the best way I can think of to cheer her up. She told me once, when she was drunk, that she really appreciates my presence. Appreciatesmypresence. I didn’t tell her but this has given me so much joy because all my life I have so rarely been able to discern whether my presence mattered to others or not. With her, there is no doubt; I know she appreciates having someone around to speak Turkish with, someone who relates to her own background. The hot water is my way of saying I see you. Her expression tells me all I need to know when she opens the door; this is what she needed. I remember that need being unmet for me so many times, festering as resentment, building the emotional walls I have put up between myself and this town and this college experience. But I also know that if just one person sees you, the walls start to crack and let some light through, and when that person is consistently in your life, they crumble completely.

Step 3: Reminisce on the Past

After three and a half years living in Burlington, I know where to go for a good walk. As my friend Rachel and I stroll along the trails of Red Rocks Park, I admire the cathedral of oak and maple trees above me and the way the sunlight soaks through the red, orange, and yellow foliage and throws its pigment onto everything like stained glass. My breath catches in my throat at the beauty I am witnessing. The trees have been allowed to grow here for hundreds of years, and their mind-boggling girths and towering heights have the comforting effect of making me feel like I am among elders, playing as a child would

at their feet. Trees have always helped me feel more centered and rooted to a place; after all, if they can happily stay in one place for so long, maybe I can, too.

Rachel and I’s conversation takes a similarly meandering path as our feet, and we talk about people and events from the past, our history running as deep as our time in college. Despite the turbulence of the last three and a half years, some very important things have remained constant. She is my mirror, and I am hers; we clarify and distill the changes that have taken place, and confirm our existence to one another. We find joy in the passing of time.

The many rocks and boulders that are scattered along the sides of the path are testaments to time continuing uninterrupted here for a long while; while the growing things, the old trees and the perennial ferns, suggest many life cycles, many sagas, playing out on this steady stage. We take a break from walking and turn our attention to a large boulder, which I immediately attempt to climb. As my fingers scratch at the rock face, they catch on to tiny beds of moss clinging onto impressions in the rock. I feel a little guilty as some of the moss slides off and falls to its end on the forest floor, knowing that the fuzzy green film has taken decades to grow there. I have always admired mosses; they are fiercely loyal to their localities. They colonize what is known as the barrier layer of air that hugs all objects; there, the air is still, slightly warmer, more humid. The intimacy that moss has with its environment is almost unimaginable, but reminds me that this is one way to be. In fact, this is the most common way to be in nature. Aloofness and non-commitment have no place in these woods.

Step 4: Envision Futures

There are special places in the world for me whose significance was created in an instant of spontaneous connection, in a single night of spectacular memory, but

Burlington has been slow to arrive in my consciousness as a special place worthy of my nostalgia. I guess I have been busy weighing out the good and the bad, but recently the tide has changed to such an extent that gratitude is the overwhelming state I am in.

Things are different this last year in college. My roots have grown deeper. I am genuinely happy and optimistic about my future. In the long term, I don’t see Burlington being the setting of my future life, but for now, it is my home. It may be my home for a bit longer, too. As I contemplate whether pursuing another degree at the same place I did my undergrad is right for me, my sense of place in Burlington is being placed front and center. The time has come to test the strength of the bond I believe I have formed with this place. On the cusp of graduating, I already feel the familiar urge to flee. To run away and preempt the inevitable changes by creating my own. You can’t watch your friends move away from a place you’ve all occupied together for four years if you move away first. Forced by inevitable change to figure out what it is I value the most, I feel as though the time has come to define my early twenties; yet, all I really want to do is try out many lives while I still can, untethered by any real responsibility. It is a lot to come to terms with in a short time. But, the funny thing is, the only way to figure out whether staying in Burlington is right for me is to continue building deep connections to the people and the land.

To every first-year who has found themselves transplanted in Burlington: belonging here takes time. College is nothing like what the movies say it is and absolutely nobody has any idea what they’re doing, despite appearances. You will inevitably be disappointed by people. You will inevitably feel insecure and enter a period where you wonder whether you are making the right choices. If you’ve been hurt enough times, you may be tempted to detach yourself from your life in a place, especially if it has an end date, and just “ride it out.” But if you look around you, I mean really look, at what is growing and thriving here, you might find yourself inspired. It takes courage to call a place home; it gives that place the power to hurt you, to cast you out; it necessitates trust. But I ask you to dare to grow your roots.

Intimacy with place seems to be an ines-

capable part of life. Nothing in nature survives without it. Even migratory birds are sustained by places on their routes that offer safety and nourishment—refugia—that they know by heart. I imagine their delight to touch down in an old haunt, mingle with old friends and recount adventures from the road. Not all birds are anchored to a place forever, although I find that I can respect this lifestyle more now. Like the birds that choose to migrate, we must return to places where we have been happy, by design. No matter how far I fly, I won’t forget where I came from—where we came from. When I return, will you meet me there? H

We’re all dancing in a blood ballet. Broken stones and found bones. Gritted teeth, we keep on pushing.

Sleeping in on borrowed luck. How do we save something?

I’ve been hung up on Tales of Sweetgrass and Trees—a conversation between Robin Wall Kimmerer and Richard Powers, facilitated by Terry Tempest Williams and hosted by Harvard University’s The Environment Forum at the Mahindra Center—since the vibration of their voices hit my eardrums. Salivating as each thought exhales into air and fleeting syllables fall from their tongues. Again and again… and again. I keep listening. I cannot stop. Breathless. Spiraling. My ears are ringing.

A puddle of drool pools beneath my open mouth.

Howdowesavesomething?

Powers—environmentally minded author of twelve novels and recent success, The Overstory—sputters out, “We’re afraid of feeling. We’re afraid of being vulnerable in the face of something so magnificent.” Seated at my desk, a semblance of bones and flesh hanging on every word he exhales, pain and shame and paralysis sit heavy on my chest. Crushing my lungs. Choking my breath. Stiffening my neck. Taunting hesitance. I am afraid. My limbs pantomime and flail, aching to collapse and ooze in response to Powers’ vulnerability, yet withering dry the moment I ease my toe into those tender waters of seeing myself. Of accepting our condition. I shake. I cannot breathe. I get up. Body breaching chair. Too soft to

Sheltering Within Storytelling: A Home on the Hill of Our Spines

By Kate Wojeck

stay. Feeling too much and too little. I am not sure how to breathe against the sweltering of night. Well, I’m not sure how to breathe in the mornings, either. The truth is, I’ve always been breathless.

Dawn or dusk, breakfast, lunch, or dinner, 10 or 20 years lived: a puddle of drool seeps from my gaping jaw.

I try to wade. Bruised and blustering, reaching skyward, turning sunlight into flesh. Surviving. I am alive. Perhaps my mother cradled a needle and sewed me together at birth, knotting muscle and mycelium to veins. Either way, with toes in the dirt the trees sing “come dance.” I listen. I love dancing; a wind pulls at my shoulders, a timidness takes seat in my eyes, I bite my tongue. Hard. For I am afraid if I start dancing—thinking, imagining, advocating—it will turn violent. Stammering and slobbery. Spinning, spinning—spiralic. Sweat beating down my brow; hands grabbing at my neck. What if I dance myself to death?

Kick ing. Weep ing. Jerk ing my body. I am afraid of my own mind in motion.

When I think too much about it I cannot breathe. The pressure and the panic we push our bodies through clatters and bangs and pierces skin, collapsing.

Gingerly stumbling away from the open laptop, the same routine of cowering into my body unfolds. I leave the puddle on the desk. Curl up into a ball on the floor, longing to bury myself underground, a seed. Not a girl. I’d be more beautiful, I tell myself. But everytime my shaky breath catches on Power’s next word. The one he spits out from the lump in his own throat, only with the will of his added breath: “Nevertheless.” The lump in mine aches. “It all changes, it all dies,” he laments, but for a moment we

are here. Be still. Commit to “unsuicide,” he urges against despair. Picking the pieces of myself up from the ground, kissing my shoulders and dusting my body off, I sit back down at my desk. Pulling my ears to listen again.

I’m just in time to hear Kimmerer—mother, scientist, storyteller and enrolled member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation— assure me that being “...afraid comes from the same place that holds the joy. From the palace of humus…the earth.” “From me in the world of you I inhabit,” she orates. She extends a sturdy, yet still cracked, hand when she whispers next, “I hope I can take my anger and turn it into sacred rage. That’s why I write.” I gasp for breath. Somehow, she’s found it in herself to not be bitter. Immobilized. How? Everything spins. Plates of these thoughts fall off the shelf in my mind, tumbling into motion, circling within my skull. I let Kimmerer pull my breathless body towards her. Swaying—then still. A hug. And as their conversation unfolds—dipping and floating, mms and ahas tangled together—their dinner table of exchanged thoughts become inhabitants of my own being’s dinner table. In this musing, others have taken seats, stoking the fire, conversations carrying into night.

Erica Heilman—podcast host of RumbleStrip Vermont—pulls up a chair, warns that “if you don’t desperately need to, you don’t have to,” speaking to her creative process and work. She notes, about the act of interviewing, to “climb into them [the person with whom you are in dialogue].” Unfurl your closed fist, finger by each awkward finger, and “fall in love.” “Learn what [they] have that gets [them] through the day that [you] don’t have.” In her words, “they’ll know when you get there. Get up that hill until you see someone you want to know about.” Witness. With that, I knew I was desperate. Not for podcasting, but for the creative work I crawl into. Writing. It’s my own deeply selfish pursuit. But like Heilman, there’s an itch in my bones. Not everyone thinks in stories. Gathers moments as sensory threads. I do. “I’m neurotic, but I care,” Heilman admits. Me too.

But is it not this pool of desperation that holds what’s most true?

Desire, anger, fear, hunger, pain, joy, sadness, hope: are these not the sensations goosebumps are born from?

I delay finding out. Sometime ago, I shut my mouth. Left the door to my body ajar for strangers to stomp through and drag mud into my house, sewing the front door shut. I stood on the street in relief, thinking they were sewing my wounds for me. I was desperate to take myself out of the writing. The witnessing. Running from

the stagnant fervor of energy festering in my body. My fragile body which always feels like it breaks everything over and over again every time I sit down to write. But amidst the murky blood from wounds with needles stuck in them, there’s been a knot in the yarn of my curiosity wondering if maybe it was time to let the creature within me breathe and bellow and scream. Even if violent. Messy. I’m a fighter, have always been a fighter–might I trust, might I try. Might I let you see me care. My mind gets in the way of letting my lungs fill up with air, ribcage shutters pinned closed. I’ve never been sure how fear could move me like love does.

I let my saliva, instead of stories, pool beneath my mouth.

Suppose I bathe in my spit. Fling myself into the work so deeply that my porous pithy flesh becomes sewn to each syllable. Perhaps you must sit long enough to witness yourself and, even if you cannot find a thread worthy of saving, accept that you are wounded. Perhaps I must peel back my eyelids to see my body alive, slick with the sweat of my own mouth.

If I breathe into the work, might it too become alive?

For Kimmerer, this is true. Her words are living beings and she introduces me to them. In “The Council of Pecans,” she pulls her grandfather to his feet from his grave

ping the floor beside my squishy soil covered toes, and admits in her essay “We Must Risk New Shapes,” “Survival is never safe. It is always a breach. A break in the skin. I do not want to heal; I want to survive.” She asks us to honor our wounds. We could let them fester and rot, or we could accept them “as invitations to risky collaborations we might otherwise not attempt.” Strand takes the bait. Vows to let her joints “sublux, cracking open for fungal incursions.” Exposing herself to the wrong path. Hobbling into holiness. “[Stumbling her] way to the sacred.” Imperfectly empowered, she advocates, “I will honor my body as material refusal to participate in this ecocidal culture. I will let my mouth atrophy, as I photosynthesize with algal symbionts. I will fuse my roots to your roots.” Might we fuse our hands too? Steady, gasps mellowing. As terrifying as this is. As terrified as we are. Might we tremble, jaws gaping, together?

But where? Where can we be this afraid and not drown?

Knees in the dirt and nose brushing moss, I know I am honest somewhere. I want to find that place and live there. I take a breath. I notice, when writing, as body, bone, breath embraces thought, I let fall from my tongue and slip from my mind all the things I dared not to say, even to myself. I can hold them now. Maybe one day I might say them to your face. Today, I must write them first or they will be buried. I will pull away. The process

One which isn’t new construction, but has endured the oscillating storms of the planet, under the care of people, for generations. Underneath our tongues, caulked in the tiles of our teeth, tucked between the rungs of our backbones, many of us have forgotten to crane our necks to see.

In frustration or rage. Elatement or soul-crushing sorrow. There sits an invitation to show up to the dinner table as you are. Stripped of clothing and bearing nothing but the heart pounding out of your chest, you’re invited into a home to take shelter amidst the sweltering night of our collective terror. As one home collapses in the cycling of being rebuilt, storytelling is the kind neighbor whose door is always open. It only asks of us to listen. And care.

How do we save something? I’ve never been sure. And I cannot promise easy days. But, by a mad miracle we go intact among the common rot.

We’re dancing in this blood ballet.

We may be breathless. That’s fine. I collapse now

into the body of a girl who understands where her fight is. Who can hold it. I trust her. Might you peel back your eyelids to see yourself alive too?

Climb up the rungs of your spine?

My roots are fused to other roots. Your roots. Ours. This dinner table is growing–you’reinvited.

Maywesheltertogether,inthehomeofallourstories, askingoncemore,howwesavesomething? H

The Delusion of Expectations: World

of Forests and Fields

What is a Forester?

What do I picture when I think of one? In my mind, he’s tall, tough, and quiet. He graduated from Paul Smith’s lookin’ and smellin’ like a true woodsman. If you were to point out a tree to him, he’d walk over, with his shoulders set back and his thumbs resting in his belt loops. He’ll sniffle once he finally reaches you and a calloused hand will rub the front of his beard as he tips his head back to look at the tree’s crown. Everything he says is short and sweet, and if he’s older, it’s with a bit of wisdom-infused sass. At the end of the day, he’ll sweep the fresh dirt off the thighs of his Carhartt pants and drive his truck down to the local joint. He takes a seat at the bar and puts his mud-caked boots up on the metal rails like they were made for him, cause they were. He orders a beer, probably a Guinness, but as long as it’s a beer he’s not that picky, and when it’s placed in front of him he offers a quick “‘preciate it” with a small hand wave. It’s hard but honest work, and as long as he’s working, he doesn’t pay any mind to the bills.

This vision I have isn’t supposed to be representative of every forester. I know that to be true, and yet the man I’ve just described is the true forester. It doesn’t matter where he’s from, maybe he’s an old logger from Maine just trying to make ends meet. Or maybe he’s fresh off of thinning thousands of acres of Doug-fir in Oregon so that the timber world keeps going around. Perhaps he just put out the last longleaf pine fire he set earlier that day down in Florida. He’s not any individual guy, he’s the embodiment of what a forester is. He’s Paul Bunyan, who could down 100 redwoods in a matter of minutes. He’s Gifford Pinchot, who revolutionized American forestry in a time when this country needed it most. He’s Bill Leak, the modern father of Eastern silviculture. He is what it means to be a forester. The expectation of what society expects a forester to be. Which means that all I’m left to do is compare myself to him. I’m a forester, aren’t I? Because the man I just described is what’s expected of me, the next generation of foresters. All these people are passing the torch to me, and they’ve set the illusion of how I’m supposed to look and how I ought to act. That feels like a lot to ask of me, especially when I’m not really

like them. Sure, I’ve met foresters who aren’t like the man I’ve described. I’ve met plenty of them. But I still know the look on peoples’ faces when I say I’m a forester, and it’s a look of confusion. It’s never upfront, I can tell they aren’t just confused with me. I can tell that their struggle is with the term forester. Because the expectation of who I’m supposed to be isn’t lining up with who I am. I can’t seem to craft that illusion, and neither can the people I meet. So I’m left to wonder about the picture that will pop into people’s minds when they hear about the forest er, Erin Camire.

Alright, so maybe I’m more of a botanist. That’s where all my experience is anyhow. That’s where I got my love for plants. It all started in the meadows of the Hudson Valley, where a fellow botanist showed me just how much there was to see. From cardinal flowers to scarlet pimper nels, I loved every single one. And it wasn’t just the plants I fell in love with, it was the idea of being a botanist. So, what is a botanist? What do I remember the fondest when I look back at my experiences? I think it was barely cov ering half an acre of woodland in a day because there was so much to look at. It was enjoying fresh apples from the tree out back while flipping through wildflower books to determine a sedge species. It was skinny dipping in the stream after a hard day of pulling Japanese knotweed. It was freedom like I’ve never felt before. Laughing, singing, and dancing through fields of rye and buttercups. Spotting New Jersey tea or a rare orchid was always greeted with squeals of excitement and furious note-taking. But, when I really think about it, the thing I loved the most was talking. And my god, did we talk. All day long we talk ed and talked, and it never got old. Nev er did I realize how many word games I could play until I was stuck weeding hedgerows of black-eyed Susans for hours at a time. And never did I know just how much I’d be willing to share with friends sitting in the old farm house library, surrounded by botany books a half-century or more old.

Every botanist I’ve ever had the pleasure to talk to will chat me up

for hours, and I love every second. They contain knowledge and passion that feels infinite, probably because it is. And it all stems from such a rich and diverse history. There were those who risked their lives to collect specimens from all over the globe, wandering in areas they didn’t always have the right to be in, all in the name of discovery. There were those who pondered over colors and placements, and were somehow able to create art and music from the land. Every fruit or vegetable I’ve ever eaten has been touched by a botanist who couldn’t help playing Cupid. But what do I picture when I think of a true botanist? What sort of person am I left to compare myself to? I think I found the answer when I applied for a landscaping job this past summer. At the end of my interview, I was told, “I hope you don’t mind working with little old ladies.” At the time, I thought to myself that it ain’t botany unless I’m working with little old ladies, and honestly I wouldn’t have it any other way.

With hand lenses tied around their necks and a worn copy of Newcomb’s Wildflower Guide in hand, those “little old ladies” are some of the most powerful women I’ve ever met. And they’re all very good at making me look like the old one, whether it’s leaving me in the dust while surveying steep slopes or letting me know I should get a stronger eyeglass prescription when flipping through densely packed flora guides. I don’t doubt their skills and their strength for a second. So could I picture myself being like them? Being a botanist? Could I picture myself waking up at the crack of dawn, putting my gray hair up in a tight ponytail, and pulling greater celandine from the gardens on my hands and knees all day? My knees hurt just thinking about it. Their work is soul-crushing, back-breaking, and severely underappreciated. Yet, it hardly seems to phase them. They get up every single day and get to work without a single complaint, not necessarily because they’re hard workers (although that is abundantly true), but because they’re doing what they love. That’s a lot of passion, and a lot to live up to. Would I be happy as a botanist? Could I find the same joy they do each and every day? Do I have the knowledge and the spirit to carry on the legacy of the people who came before me? Will I be able to match this illusion when people hear my name, the botanist, Erin Camire?

They’re very separate worlds, botany and forestry. I see them so distinctly in my mind. The two different versions of what society expects me to be. Two very different paths I can

take in my career. It seems like the second I start to favor one path, I yearn to explore the other. Why must I squash Pennsylvania sedge under my boots as I cruise timber, and why must I disregard the vibrant maple regeneration under an old big-tooth aspen as I hunt for blue cohosh? How come I seem to be one of the only ones that wants to look up at the lush canopy above me and also down at the blanket of greenery beneath my feet? In that way, I guess I’m both a forester and a botanist, yet when I think about the way both professions are perceived, I guess I’m neither.

My passion doesn’t seem to have a place in the stark illusions that are placed before me. Society tells me I have to choose, am I a true woodsman, or am I a woman in her garden? Man or woman, which am I? I’ve been lucky in my life that no one has ever asked me, straight up, if I’m a man or a woman, cause I’m afraid they wouldn’t like my answer. Because at the end of the day, they’re asking me the wrong question. “Man” or “Woman,” these words hold no weight to me, and I don’t feel torn between them. I’m not just somewhere in the middle, I’m outside the binary altogether, and thus outside of the question. If you want a thoughtful answer, then you’ll need a more applicable question, one that truly defines how I interact with the world around me. Funny enough that question would be: are you a forester or a botanist? I’m both and I’m neither. I can’t check either box. I can’t get either shoe to fit. I can’t label who or what I am. In terms of how I’m going to be perceived, I seem to be off the spectrum altogether, and I think I have to take that in stride if I want to keep pushing forward. I will defy the expectations and standards that I’ve been given, and forge my own way, with botany in my heart and forestry on my sleeves. I need to push past the illusions that I have allowed to cloud my vision. I have to carry the knowledge of those who have forged the path thus far, and start carrying my own weight in this world. Not as a forester or a botanist. As me, Erin Camire. H

Skimming the Surface: An Introduction to Eutrophication in Lake Champlain

By Jaylyn Davidson

By Jaylyn Davidson

In late summer and early fall, the Vermont Department of Public Health warns against entering Lake Champlain’s waters due to dangerous blooms. Lake Champlain is particularly vulnerable to cyanobacteria and other harmful algal blooms, compromising the safety of the water and hindering the general public’s ability to enjoy the lake.

Cyanobacteria, colloquially referred to as blue-green algae, thrive in an abundance of nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorus. Although necessary for plant growth and development, excessive amounts of these nutrients from agricultural and stormwater runoff can induce eutrophication in freshwater habitats. Eutrophication occurs when excess cyanobacteria die due to depleted levels of nutrients and start a decomposition process, consuming all available dissolved oxygen. When dissolved oxygen is depleted, the water becomes anoxic, rendering it incapable of supporting aquatic life.

To gain further insight on eutrophication in Lake Champlain, I spoke to Dr. Ana Morales-Williams, a limnologist at the Rubenstein School who specializes in this topic. According to Dr. Morales-Williams, eutrophication impacts lakes in a variety of ways, including an increase in phytoplankton biomass, algal decomposition, and low oxygen levels in the water column, known as hypoxia. She referred to Missisquoi Bay and Saint Albans Bay, areas in the northeast arm of Lake Champlain, as being “very eutrophic systems

relative to the main lake, [as they] function more like mesotrophic or oligotrophic lakes.” Mesotrophic lakes are intermediate, with medium levels of nutrient abundance, whereas oligotrophic lakes are nutrient deficient and have low biological activity. In these re gions, “eutrophication has caused a large increase in blooms over the past several decades that are intensify ing due to a number of factors.”

Dr. Morales-Williams shared her view on how climate change in Vermont has impacted eutrophication in Lake Champlain. She referred to lakes as “canaries of the land scape” because of their capacity to respond to changes in the watershed and in climate at a faster rate than ter restrial ecosystems. Lake Champlain is currently facing two important issues catalyzed by a warming climate: reduced ice cover and season mixing. Each year, the period of ice cover is decreasing and there is a delay in when ice be gins and melts. She stat ed that, “Lake Champlain is a dimictic lake, which means that it mixes twice a year.” The first melt and spring mixing event are responsible for

the timing changes, or the events cease to occur, the ecosystem will suffer.

Climate change is increasing the presence of algal blooms in other ways as well. Dr. Morales-Williams stated that “changes in timing of snow melt, pulses of nutrients, or big storm events… have the effect of supporting high biomass and diversity of cyanobacteria” that allow them to persist longer than they would under more stable conditions. Consequently, cyanobacteria are becoming a greater issue as climate change causes more frequent ex-

When it comes to mitigation and prevention efforts, Dr. Morales-Williams argues that people must be responsible land stewards and utilize more sustainable land-use techniques. Due to the fact that “Lake Champlain has a very large watershed relative to its surface area—which is kind of unusual for a large lake—whatever we do with the watershed really matters a lot to what happens in the lake.” The Lake Champlain Watershed constitutes 8,000 square miles and includes mountains, woods, farmlands, and settlements that all flow into the 120-mile-long lake. This lends to a 19:1 land-to-lake ratio, significant when compared to other large lakes, such as Lake Superior, which has a ratio of 1.5:1. Since the watershed has a disproportionately large influence on the lake due to its size, we must be attentive to the types of activities that are conducted throughout the watershed in order to minimize the transport of pollutants and excess nutrients into the lake. Mitigation strategies and general education about eutrophication in Lake Champlain should be taught in all Vermont schools to give students a deeper understanding of the place in which they live. Shane Heath—a tenth and eleventh grade teacher at Essex High School—articulates how Lake Champlain is “a microcosm of what’s happening in parts of the ocean like [the] Chesapeake Bay,” making it a tangible local example with global implications. Eutrophication, he stated, is especially important in a small state like Vermont, which prides itself on being

Heath emphasizes eutrophication is a particular

topic that teachers must embrace in their curriculums. He adds, “it is certainly a missed opportunity if you’re teaching in Vermont and not talking about eutrophication, because it’s a way that we can see climate change effects, and also just human rela tionships to the land, first hand and how those have to change.” Exposing students to water-related issues, particular ly local topics, is vital because it demonstrates how our actions influ ence the environment. Heath feels that this could easily be implemented in many schools, explaining, “every school probably is in some sort of walking proximity to a stream or river where they can easily do some pretty meaningful science.” He cites benthic macroinvertebrate sampling as an example of hands-on, water-related science already integrated in many Vermont schools. The process of utilizing benthic macroinvertebrates to measure water quality starts by ruffling about rocks and catching them using a kick net. The number collected, as well as the degree of environmental stress, are then calculated and compared to a pollution tolerance index to estimate the quality of the water.

Outside macroinvertebrate sampling, interdisciplinary approaches to eutrophication through the humanities and sciences are needed to increase awareness in school curriculums of the threats posed by eutrophication. Heath notes, “I’d be surprised in elementary or middle schools, and even in all high school curriculums, if they’re really talking about agriculture, wastewater treatment, and suburban runoff as ‘causes and effect.’” He goes on to add, “it’s our responsibility [as science teachers] to talk about some of the biggest issues facing our planet and facing this generation.” In addition to improving eutrophication education on Lake Champlain, Heath believes that planting riparian buffers to help prevent point and nonpoint source pollution and assisting local farms with adopting more sustainable techniques for the lake and land will help mitigate eutrophication.

Eutrophication in freshwater ecosystems is a major issue in Lake Champlain, and scientists are still working to find ways to mitigate and prevent both the process and its harmful effects. As Dr. Morales-Williams and Heath both advocate, we can all contribute to reducing the impacts of eutrophication by being educated land stewards. H

Fire in the Pines

New England’s Forgotten Fire Story

By Valentin Kostelnik

By Valentin Kostelnik

Drifting on a warm breeze, a light blue butterfly flutters down to a similarly-colored flower in a grassy field in New York. The butterfly delicately lands on a lupine, extends its proboscis into the nectar, and takes a draught of much-needed sustenance. Around them is a wide grassland dotted with scrub oak and pitch pine woodlands, and parts of the open landscape are charred with ash from a recent fire.

In Northern California where I grew up, fire is the object of much fascination, anxiety, and conversation. The summer months now bring regular megafires that turn each day into one long, orange twilight. In the ever-shrinking intermissions between fire seasons, everyone eyes the rain forecast obsessively, wondering how bad the following year will be. Everyone in fire country has an opinion on prescribed burns too, a hopeful solution to our current crisis. As someone aiming for a career in fire, I sometimes wonder what I’m doing in New England, one of the only regions in the country that never burns. Being from California, I have been familiar only with cataclysmic megafires that should be feared, and prescribed burns that need to be expanded to a landscape scale. Both of these versions of fire exist only in the West and parts of the Southeast, and neither exist anymore in New England.

I staffed a student welcome day back in November with Cathy Shiga-Gattullo, who had a fire-scarred oak round on display to catch the eye of passing families. I asked her where the tree was from. “Colorado? California?”

“Poughkeepsie!”

Poughkeepsie? There are no fires in New York. What is a fire-adapted oak doing in Poughkeepsie? Cathy patiently explained that the round was from the Mohonk Preserve, where managers are trying to restore a fire regime to an oak woodland. She gave me the contact information of a few New York fire managers, and advised that I learn about the forgotten role of fire in New England’s ecology, both past and present.

Unlike Western states, New England would have few fires under natural conditions, if any. The region lacks a rhythmic wet-dry cycle, so the forest fuels never become combustible on a large scale, and lightning is always ac-

companied by rain, leaving no natural source of ignition. As Mark Twain famously observed, “If you don’t like the weather in New England, wait 15 minutes.” While out West, vegetation has months of hot, dry weather to become combustible, New England veg etation has a few weeks at most. You can imagine trying to light a fire in the damp litter layer under a northern hardwood forest; it won’t work.

In California things are less picky. In my home town, it stops raining around April, and we might not see a drop of rain until November. Entire forests are turned into tinderboxes on an annual basis, and a single lightning strike can burn hundreds of thousands of acres. Even without human interference, landscape-scale fires are frequent.

Compared to the West, wildfire in New England is in credibly rare under natural conditions. This is why most people today believe it to be nonexistent in the region, and why I was so surprised to learn that fire was once a common occurrence here when Native Americans managed the land. But because fire is so naturally rare, the role it plays in New England has always been closely controlled by humans and reflected their land-use values.

Bill Patterson, one of New England’s foremost fire scientists, told me, “I devoted my career to finding out a fraction of what the indigenous people in New England knew about fire.” Prescribed burning in New England is difficult and requires intimate knowledge of habitat structure, weather patterns, and many other factors, but can be an incredibly valuable ecological tool. Natives needed the land for hunting and for agriculture, both of which can be made more productive by fire.

Fire is enormously advantageous to a hunter. All dead material is burned, and any surviving grasses or shrubs immediately send out new growth, which attracts game from nearby unburned areas. Furthermore, in a cleared forest, a hunter can locate and kill game far easier than in an overgrown one.

In Southern New England and along the coast, native groups were more sedentary compared to northern tribes and practiced extensive agriculture. Fire was particularly

frequent around their settlements, where they used it as an agricultur al tool. They employed slash-andburn practices, in which large tracts of forest are cleared using fire before be ing cultivated. Early ac counts of colonists visiting New York and Pennsylvania describe “open plains twenty or thirty leagues in extent, entirely free from trees.”

Native Americans managed the land using fire for thousands of years, long enough for species like the Karner blue butterfly and landscapes like oak woodlands or pine barrens to become fire-adapted. Though fire may be absent now, it is partly responsible for the New England we know

When colonists arrived, large portions of Pennsylvania, western New York, and the coastal plains were likely under prescribed fire management. Contrary to some modern views, colonists initially embraced fire, and records show a 16th century wave of prescribed fire on an even greater scale than what the natives maintained. These early colonists, mostly farmers and hunters, used the land in similar ways as the natives, so fire stayed on the land. They put fire to use in “fire herding” to clear new land for agriculture, and to keep the forests clear. As the population of New England boomed in the 18th and 19th centuries, so did prescribed burns, and many contemporary observers wrote about widespread prescribed fires in New England even into the 19th century.

Then, as railroads and westward expansion depopulated much of the region, fire subsided. Forests regrew in its absence, and many of the old agricultural fields were replaced with hardwood “old-field” stands. Logging became a huge industry once these stands grew big enough to be harvested, and fire manifested very differently under logging than under agriculture and hunting. The slash left over after logging is superb fuel that dries out quickly, especially given there is no canopy to shade it. Wildfire gorged on the slash and New England was wracked by some of the largest fires in its history, such as the 1903 Adirondack fire that burned 600,000 acres. It’s this version of fire, not the version that existed under

natives and early colonists, that modern America first responded to. These fires, along with even larger fires in the West like the “Big Blowup” of 1910, prompted environmentalists like George Perkins Marsh and Gifford Pinchot to conclude that fire was inherently destructive, and forced the Forest Service to institute its infamous total suppression policy.

The Forest Service’s suppression policy is often blamed for a lot of our problems with fire today, and the people who crafted it are painted as ignorant and dismissive of indigenous practices. This is certainly true, but they were also responding to a form of fire that was very different from the benign burns that came earlier. After living through multiple megafires, I know it can be hard to view fire as anything but a thing to be feared. In the early 20th century, that is all it was. This kind of fire had no place in humans’ use of the land, and so it was eradicated.

For most of the 20th century, it was absent, and it wasn’t until the 1980s and 90s that researchers like Bill Patterson started to rediscover fire as an integral part of ecosystems.

These researchers, including Patterson, noticed that some species, like the Karner blue butterfly, rely on fire for survival and suffered precipitous declines in its absence. One of the first places in New England to reintroduce fire was created for the endangered Karner blue butterfly. It’s called the Albany Pine Bush Preserve, and it is one of the most successful of its kind. It lies surprisingly close to the New York capital, and conversations with burn boss Tyler Briggs gave me a clearer picture of modern prescribed fire practices here.

The Albany Pine Bush Preserve encompasses about three thousand acres of pine barrens, all maintained by fire. It is a mosaic of grasslands and pitch pine groves, with blue lupines dotting the grassy fields and little underbrush to obscure the pine groves. It was founded in 1988 to satisfy the Endangered Species Act, and today this rare ecosystem supports 20% of all endangered species in New York. Most pine barrens grow on deep deposits of rapidly draining sand, which can absorb huge amounts of rain but can’t hold onto it, meaning pine barren soil

can dry out just a few days after a rain. Species like pitch pine excel in these conditions and happen to drop a lot of needles, which is superb tinder. In addition, as Patterson describes, “A lot of the species that grow with [pitch pine], like huckleberry and blueberry, produce one-hour fuels.” One-hour fuels are any organic material that can dry out within one hour, compared with ten-hour or thousand-hour fuels. So even in New York’s humid climate, where multi-week droughts are rare, Albany Pine Bush reliably becomes combustible after just a few days of warm, dry weather.

The Pine Bush initiative began in 1981 when the federal government, in response to increasing demand from locals, bought the land to become habitat for the endangered Karner blue butterfly. The barrens in the late 70s were overgrown and shaded out, with little lupinus perennis and few Karner blue butterflies, and the state government was desperate to transform it into healthier habitat. The only way to do that was fire. So fire was reintroduced.

Since then, managers of the barrens have adopted an annual burn plan. Under this regime, every acre is burned once every 3-5 years, a schedule that creates a patchwork of habitats in various stages of succession. Tyler Briggs, who currently heads the program, said that they try to burn 10% of the preserve every year, approximately 300 acres. The best time to burn is in the spring dormant season, after snowmelt but before leaf out, “when sunlight penetrates through the canopy and dries out the organic matter that’s on the ground.” In Albany, snowmelt generally occurs in midMarch. Mr. Briggs says, “our prime time, when we get most of our burning done, is between St. Patrick’s Day and Memorial Day.” After April and May, they may get a few low-acreage burn days, but they don’t count on it.

New England doesn’t rely on the forest for food like the natives and early settlers. So why should we value fire? The answer is not yet clear, but so far fire has been a tool for ecology and preservation. Bill Patterson thinks, “the future is going to be related to the preservation of endangered species that can be shown to be dependent on fire.” This can be seen in the Albany Pine Bush, and when they’re prepping burn plans, the Karner blue butterfly is always the first concern. The butterfly needs lupinus perennis, which needs sunny fields, which are maintained by fire. The Endangered Species Act demanded the Albany Pine Bush create habitat for the butterfly, so fire was returned.